Abstract

Infections with coronaviruses remain a burden that is negatively affecting human life. The use of metal oxides to prevent and control the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been widely studied. However, the use of metal oxides in masks to enhance the performances of barrier face coverings in trapping and neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 remained unexplored. In the present study, we explore the possibility of developing surface functional PVA/ZnO electrospun nanowebs to be used as a component of multilayer barrier face coverings. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and zinc acetate (ZnA) nanowebs were electrospun as precursor samples. After calcination at 400 degrees centigrade under a controlled atmosphere of nitrogen gas, product nanowebs containing ZnO (PVA/ZnO) were obtained. The presence of ZnO was determined using an attenuated total reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer. This study inspired the possibility of developing surface-functional materials to produce enhanced performance masks against the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: Electrospinning, Functional nanoweb, Zinc oxide, Polyvinyl alcohol

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus that is reported to be more contagious than SARS-CoV (El-Megharbel et al., 2021). For this reason, the virus rapidly spread across the globe in a relatively shorter period (Mallakpour et al., 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 2 July 2022, the global confirmed number of COVID-19 cases was 545,226,550 including almost 6.4 million deaths (WHO, 2022). Reducing the spread and impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak is of great importance. The spread, diagnosis, prevention, control, and treatment of COVID-19 have been studied extensively (e.g., Manigandan et al., 2020; Ayodeji et al., 2022; Shahid et al., 2021). The use of barrier face coverings is one of the prevalent global mitigating measures against the COVID-19 pandemic because of their ability to block SARS-CoV-2 laden respiratory droplets (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020; WHO, 2020). The use of barrier face coverings was recommended by the World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) because of the capabilities of the face coverings to prevent infection by blocking droplets and aerosols carrying infectious virus (CDC, 2020; WHO, 2020; Ayodeji et al., 2022).

The use of metal oxides to prevent and control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 have been widely studied (Abo-zeid et al., 2020; Donnadio et al., 2021; El-Megharbel et al., 2021; Mallakpour et al., 2021). A molecular docking model study by Abo-zeid et al. (2020) to understand the interactions of metal oxides with the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 revealed that metal oxides interacted efficiently with SARS-CoV-2 resulting in conformational changes to the structural proteins of the virus that subsequently inactivated the viruses. Coating surfaces with metal oxides such as iron III oxide (Fe2O3), titanium dioxide (TiO2), and zinc oxide (ZnO) that exhibit antiviral properties could play an important role in the fight against the spread of COVID-19 (Delumeau et al., 2021; Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2021). Presently, surface decontamination is done by cleaning with traditional disinfectants with only temporary disinfection action (Hosseini et al., 2021; Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2021). Zinc oxide nanoparticle has been used as a Nano-spray to disinfect surfaces against SARS-CoV-2. El-Megharbel et al. (2021) reported high antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 at a low inhibition concentration (IC50) of 526 ng/mL.

Zinc is one of the most abundant trace metals found in human bone, muscle, and other organs (Tsuneo, 2019). ZnO has received high attention as a metal oxide with antiviral properties because of its advantage of being biocompatible, relatively affordable, less toxic, and considered safe by USFDA (Anjum et al., 2021; El-Megharbel et al., 2021). ZnO is directly effective against many viruses including SARS-CoV-2 (El-Megharbel et al., 2021). It can prevent viral entry, replication, and spread (Tsuneo, 2019). An electrostatic, physical, and hydrophobic interference of zinc with HSV-1 was reported by Farouk and Shebl (2018). Surfaces modified with ZnO nanoparticles could interfere with the virus through complete neutralization. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 coatings developed from ZnO particles were documented to reduce the infection potential of SARS-CoV-2 by more than 99.9% in 1 hour (Hosseini et al., 2021). Infections with coronaviruses remain a burden negatively affecting human life. The 2 major routes of transmission are airborne and direct contact (Ayodeji and Ramkumar, 2021) but the dominant route is airborne (Zhang et al., 2020). While the effectiveness of ZnO coatings on surfaces to prevent fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has been reported, the use of ZnO in barrier face coverings to control the airborne spread of the virus has not been fully explored. Few studies that investigated the inactivation of RNA viruses by metals embedded in fabrics were limited by confounding factors including fabric density, absorbance and the complexity of fabric design that could not be accounted for (Gopal et al., 2021). The development of personal protective equipment that can trap and neutralize respiratory virus may help to address the spread of the current SARS-CoV-2 and future strains of respiratory viruses (Gopal et al., 2021).

The fabrication of electrospun PVA/ZnO nanowebs from precursor PVA/ZnAc nanowebs have been studied for different purposes such as biomedical (Jamnongkan et al., 2018), high-tech (Wu et al., 2006) applications, and drug delivery (Anero et al., 2021). The applications of functional electrospun PVA in transdermal drug delivery (Parin et al., 2021a), as bioactive fibers (Parin et al., 2021b), and in electronic skin textile (Wang et al., 2021) have also been documented. Previous studies that explored the production of PVA/ZnO from precursor PVA/zinc acetate reported varying parameters specific for purpose. For instance, Wu et al. (2006) calcinated the precursor nanofibers at 500°C resulting in about 75% loss of sample mass. In their experiment, the retention of sample mass was not a major consideration because the purpose was for the development of high-technology nanostructures.

On the other hand, sample structure retention was a key parameter in the experiment performed by Chen et al. (2021) and for that reason, calcination process was terminated at 140°C when fiber degradation began to occur. Jamnongkan et al. (2018) highlighted the importance of experimental parameters on intended use of electrospun samples. In the current study, we determined optimum calcination temperature of PVA/zinc acetate nanowebs and highlighted the possibility of functional PVA/ZnO electrospun nanowebs as a component of multilayer barrier face coverings to enhance blocking performance against SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and methods

Chemical compounds

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) used in the present study was previously purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The molecular weight of the powdered PVA ranged from 89,000 – 98,000 g/mol with 99% purity. Zinc acetate (ZnAc) was purchased from Fisher Scientific, 99% pure. The PVA and ZnAc were used without further purification. Deionized water was used as the solvent to dissolve the powdery compounds.

Preparation of PVA solutions and electrospinning

Methods described by Turaga et al. (2016) and Lou et al. (2020) were used in the present study with slight modifications. Briefly, multiple 10% PVA solutions (w/v) were prepared by dissolving 5 g of PVA in 45 mL deionized water at 80°C for 3 h with intermittent stirring. PVA/ZnAc precursor solutions with 5%, 10%, and 15% ZnAc concentrations were prepared by dissolving 0.25 g, 0.50 g, and 0.75 g of ZnAc (w/w) in the prepared PVA solutions. The resulting mixtures were magnetically stirred at 60°C for 6 h to obtain a transparent homogenous solution. Each solution was electrospun and the resulting nanowebs were collected on grounded aluminum foil. The aluminum foil collector was placed at 14 cm from the syringe tip and other electrospinning conditions used to produce the PVA (control) and PVA/ZnAc (treatments) nanowebs were optimized as follows: solution flow rate of 0.015 mL/min, voltage supply of 18 kV, and 23-gauge needle mounted on 5 mL plastic syringe. Nanowebs were obtained when voltage supplied to the tip of the needle formed a jet of fibers collected on the grounded aluminum collector. At the end of the experiment, the electrospun nanowebs were removed from the collector, dried in an oven at 110°C for 1 h, and stored in a desiccator under vacuum until further analysis within 3 days.

Viscosity of solutions

The viscosities of the polymers solutions were measured at shear rates range of 10−1 and 103 s−1. Viscosity was measured using an Anton Paar MCR 92 Rotary Viscometer with spindle diameter 25 mm, spindle length 100 mm, and plate distance of 0.05 mm, at 22 °C. Obtained data were exported to Microsoft Excel for further statistical analysis. Plots of shear rate (y - axis, 1/s) and shear stress (x - axis, Pa) were constructed for each of the polymer solutions and the coefficient of determination (R2) recorded. The slope of the graph represented the viscosity (Pa.s) of the solutions.

Thermogravimetric analysis, calcination, and morphology of samples

Thermal stability of the control and treatment nanowebs were determined by performing Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with a Linseis Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA PT 1600). Samples were weighted, placed in a platinum plate, and heated under nitrogen at 10°C/min from 25°C to 600°C and a dwell time of 30 mins before cooling. Based on the results of the thermal behavior, nanoweb samples were calcinated at 400°C under nitrogen atmosphere for 6 hrs. The morphologies of the samples (control and treatments) were studied using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The samples were placed onto sample mounts by double-sided carbon tape and then coated with a thin layer of iridium to provide electrical conductivity. Images were collected by a Zeiss crossbeam 540 with secondary electron detector at 3 kV. The average diameter (nm ± standard deviation) of nanofibers in the samples were calculated by measuring the diameters of fibers (n = 5) at different random locations in the webs.

Infrared spectra study

Infrared (IR) spectra of the samples (before and after calcination) were studied using a Bruker Optics Vertex 70 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (x scans, resolution of y cm−1). The FTIR spectrometer was equipped with a Bruker Optics Platinum attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory (diamond ATR crystal), mid-infrared source, KBr beam splitter, and room temperature deuterated lanthanum α alanine doped triGlycine sulphate (DLaTGS) detector. Samples were ground and placed on the diamond holder of the FTIR setup accessory. IR spectra were recorded in the range of 4,000 – 400 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 sample scan count. Transmittance spectra images were processed with OPUS (v.7.0) spectroscopy software.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) evaluation and data processing

X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were acquired using a Rigaku SmartLab 3kW XE diffractometer with CuK α radiation. The intensity of the XRD data were collected over a 2θ range of 10 – 70O. Crystallite sizes were estimated from the XRD data using the SmartLab Studio II Powder XRD Plugin Halder-Wagner method (Halder and Wagner, 1966). Calculations were performed using width correction from the National Institute of Standards and Technology standard reference materials SRM 660a (lanthanum hexaboride powder, LaB6) that were applied as external standards. Data processing were performed using Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO, Version 2204 and OriginPro, Version 2021b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

Results and discussion

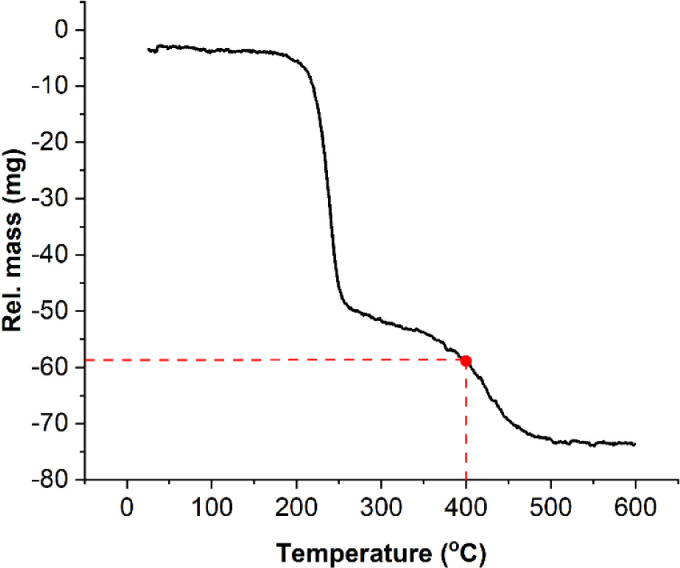

The thermal decomposition of PVA/ZnAc nanowebs is given in Fig. 1 . Endothermic heat reactions significantly peaked after 200 °C up 270 °C in the TGA curve. This portion of the curve is probably due to the evaporation of water contents (Atalla and Isogai, 2010). What followed was possible decomposition of organic contents (PVA and ZnAc) from 270 °C to 450 °C (Chand and Fahim, 2008) after which no notable sample weight loss was observed. The crystallization of ZnO was reported to begin around 250 °C (Majumder et al., 2003). In the present study, the curve becomes steeper after 270 °C and increases with increasing crystallization of ZnO. Before 270 °C, only about 40% of the initial nanoweb samples were lost but after 450 °C, about 70% of the precursor samples were lost, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Thermogravimetric analysis for thermal behavior of PVA/ZnAc nanoweb samples. Samples were calcinated at 400 °C resulting in about 58% loss of original weight.

The results revealed that most of the organic contents had decomposed at 450 °C as indicated by the linearity of the curve around 460 °C. Because of the need to retain as much of the nanoweb samples as possible and the need for sufficient ZnO crystallization, 400 °C was selected for the calcination of the samples in the present study with about 58% loss of original mass.

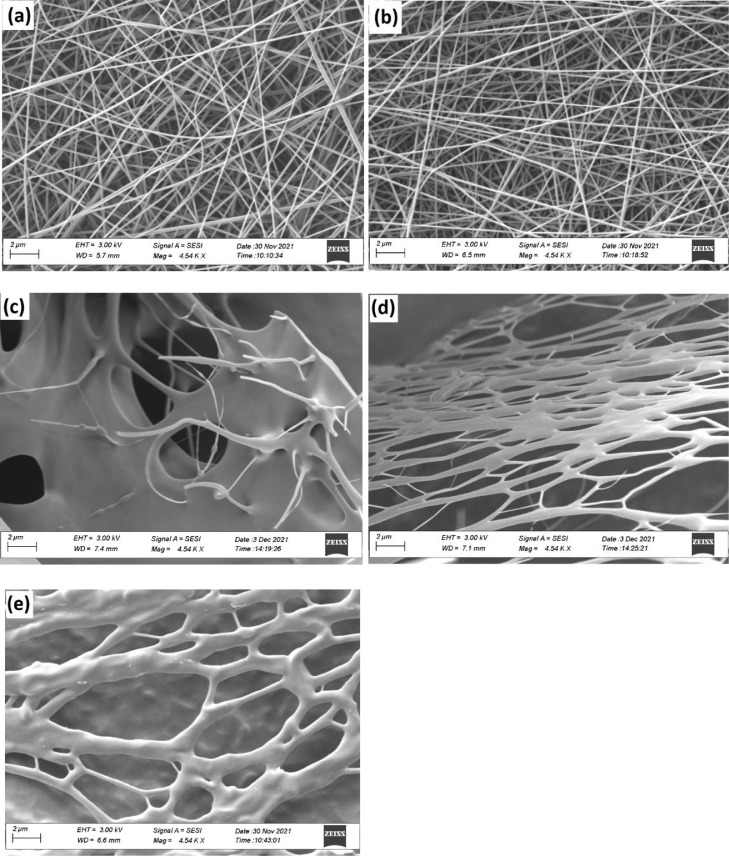

The morphologies of the electrospun PVA (control) and PVA/ZnAc nanofibers (before and after annealing) were examined using SEM, as presented in Fig. 2 . The images indicated random orientation of the nanofibers. As shown in Fig. 2 b, the surface of the PVA/ZnAc samples without heat treatment is comparatively smooth as the control samples in Fig. 2 a. The precursor nanofibers are homogeneous with uniformly distributed ZnAc compounds inside the fibers. This shows even dispersal of ZnAc in the electrospun nanowebs. The average diameters of nanofibers before calcination were 138.46 nm (±16.77) for the control, and 124.64 nm (±11.19) for the 10% ZnAc/PVA. After calcination, the diameters were 272.14 nm (± 45.17), 347.18 nm (±78.42), and 576.3 nm (±114.25) for the 5%, 10%, and 15% ZnAc/PVA calcinated samples, respectively. Zinc acetate and heat treatments seemed to affect the morphologies of the nanoweb samples.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of nanoweb samples, (a) control (without ZnAc), (b) 10% ZnAc before heat treatments, (c) 5% ZnAc after calcination, (d) 10% ZnAc after calcination, and (e) 15% ZnAc after calcination.

The concentration-viscosity relationship of polymer solutions has been studied (e.g., Gupta et al., 2005; Tiwari and Venkatraman, 2012) and established to be direct (Tiwari and Venkatraman, 2012), that is, viscosity increases with increasing concentration. However, the concentration of the PVA polymer remained constant in the present study. The viscosity of the 0, 5, 10, and 15% ZnAc-treated polymer solutions were 28.01 (R2 = 0.9924), 18.19 (R2 =0.9845), 44.43 (R2 = 0.7143), and 30.95 Pa.s (R2 = 0.9867), respectively. No specific increment or decrease in viscosity was observed as a result of ZnAc inclusion. The observed increase in the average diameter between treatments may have resulted from the amount of crystallites in the product nanoweb samples. The significant thermal degradation of samples resulted in notable distortion of nanowebs. The smooth uniform morphology of the fibers changed to a linked crystallite tubular form as indicated in Figures 2 c – e. The increase in average diameters and standard deviation that varied widely after calcination resulted from thermal amalgamation of adjacent nanofibers, as revealed by the images.

The thermal decomposition trend observed in the present study is similar to the one reported by Wu et al. (2006). As revealed by the TGA analyses, increasing calcination temperature continually increase the degree of sample thermal decomposition. Despite the thermal degradation (about 58% loss of initial weight) of the nanofibers at 400 °C after 4 hrs., SEM images revealed that the samples still possessed initial fiber formation sufficient for further analysis. However, the ZnAc treatment and electrospinning parameters need optimization. Optimizing calcination conditions are particularly important because these are directly connected to final fiber morphology and porosity.

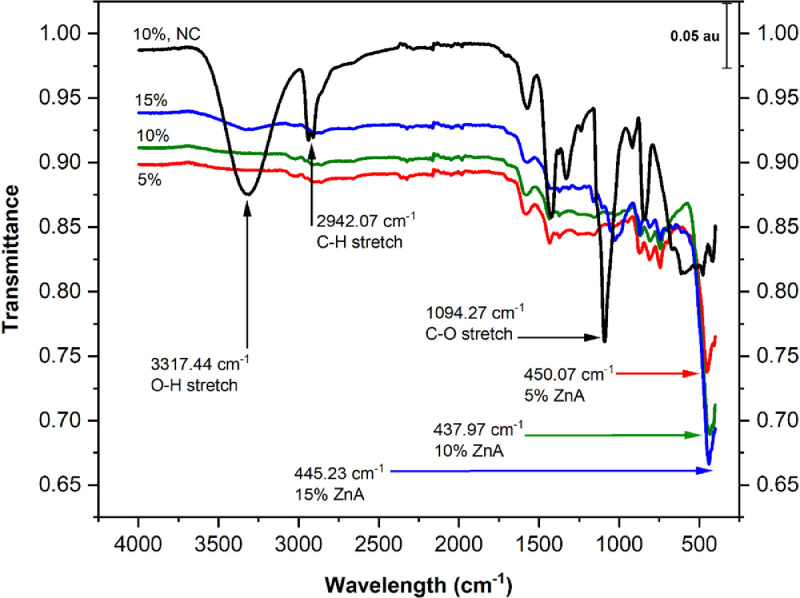

The infrared (IR) spectra of the precursor and final calcinated samples of PVA/ZnAc are presented in Fig. 3 where the characteristic transmittance bands were displayed at 4,000 to 400 cm−1. The spectra of the precursor samples shows distinctive peaks including peaks at 3,317 cm−1, 2,942 cm−1, and 1,094 cm−1. These peaks are characteristic of the vibration resulting from the absorption of the O-H, C-H, and C-O bonds (Segneanu et al., 2012; LibreTexts, 2021), respectively. The 3,317 cm−1 peak, associated with O-H stretching, may have resulted from the absorption of water from the unheated precursor samples while other bonds are associated with other organic (C-H, C-O, C-C) bonds. The final calcinated samples show a well-defined peak at 450 cm−1, 438 cm−1, and 445 cm−1 for samples containing 5%, 10%, and 15% ZnAc, respectively, confirming the presence of ZnO. The previously documented range of IR spectra of Zn-O stretch was 430 – 449 cm−1 (El-Megharbel et al., 2021; Hamdi et al., 2021).

Fig. 3.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra of ZnAc-containing nanoweb samples before and after calcination. The black curves represent the precursor samples (without heat treatments but containing 10% ZnAc), while other colors represent calcinated precursor PVA/ZnAc nanoweb samples. Blue, green, and red curves represent samples with 15%, 10%, and 5% ZnAc, respectively. Key: NC = not calcinated.

The precursor PVA/ZnAc sample was not heat-treated and did not display the distinctive peak around 450 cm−1. This indicates the importance of heat for the crystallization of ZnO obtained in the final samples. The IR spectra of treated and calcinated nanoweb samples lacked the distinctive peaks associated with O-H, C-H, C-C, and C-O stretches. This also showed the heat removal of other organic bonds. Continuous calcination above 450 °C will result in complete removal of organic components as depicted in Fig. 1. However, sample calcination at 400 °C (under a nitrogen atmosphere) achieved sufficient crystallization of ZnO as detected by the attenuated total reflectance FT-IR spectrometer and significant removal of ZnAc.

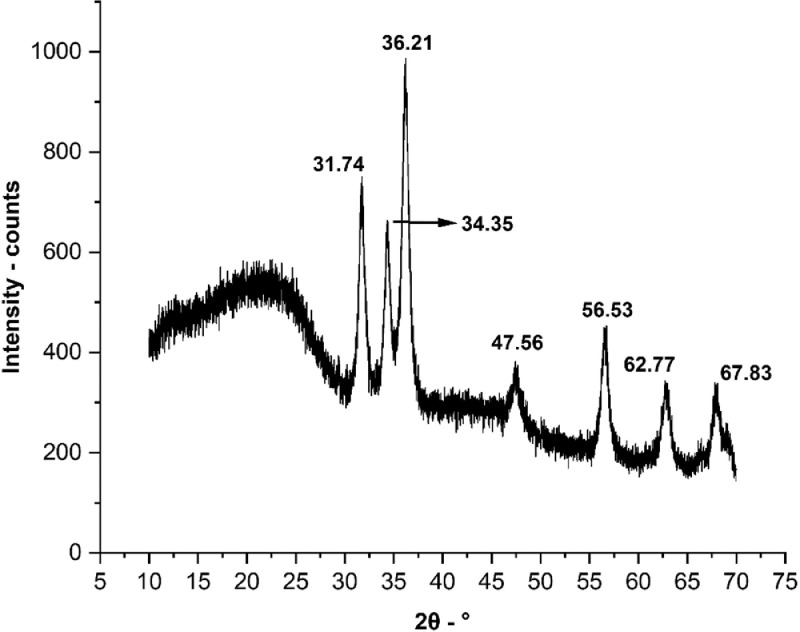

The detailed information about the XRD and various reflections are given in the Table 1 . In the present study, the diffraction peaks were observed at angles (2θO) of 31.74°, 34.35°, 36.21°, 47.56°, 56.53°, 62.77° and 67.83° for calcinated samples. All the diffraction peaks observed in the current aligned with the peaks documented by the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS, Card No. 36-1451) for ZnO structure (Wang et al., 2008). No evidence of any other crystalline structures was observed (Fig. 4 ). Given the purity of the chemical compounds and reagents used in the present study, the XRD analysis also demonstrated the presence of ZnO in the product sample.

Table 1.

XRD peak list and crystallite details

| 2θO | Height (counts) | FWHM (o) | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31.738 | 250 | 0.738 | 11.7 |

| 34.354 | 200 | 0.698 | 12.4 |

| 35.400 | 44 | 0.700 | 12.4 |

| 36.212 | 414 | 0.773 | 11.3 |

| 47.560 | 70 | 0.980 | 9.3 |

| 56.530 | 166 | 0.840 | 11.3 |

| 62.770 | 102 | 0.990 | 9.8 |

| 67.830 | 82 | 1.510 | 6.6 |

Keys: FWHM = full width at half the maximum intensity (FWHM) in degrees; D = crystallite size

Fig. 4.

XRD pattern of PVA/ZnAc samples annealed at 400°C under N2 atmosphere for 6 hrs. Comprehensive analysis report indicated a hidden peak between 35.35 and 36.21.

Conclusions

COVID-19 remains the biggest health issue with worldwide impacts. The mechanism through which SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that caused COVID-19) spreads is not fully understood. The use of face coverings is still recommended as a mitigating measure against the transmission of the respiratory virus. This is because face coverings offer series of filtration mechanisms. Metal ions such as ZnO are known to inactivate respiratory viruses and if embedded in personal protective equipment (PPE) may improve performance. However, confounding virus-filtration qualities of PPE materials make evaluation difficult. The utilization of surface functionalized electrospun nanofibers may offer a more suitable material for assessment. Additionally, surface functional nanowebs can be used for advanced face masks.

Zhang et al. (2020) had previously recommended the use of electrospun fibers for advanced masks during the COVID-19 pandemic because nanometer-sized fibers offer higher filtration efficiency and with adjustable composition and structures, they can be functionalized to fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The present study examined the possibilities of developing surface functionalized electrospun nanofibers with antiviral properties that could be embedded in face mask layers. The results of the current study indicated feasible inspiration for the development of antiviral electrospun ultrafine fibrous face masks. Future studies should characterize the product PVA/ZnO nanofiber and examine the efficacy of the product PVA/ZnO on target microorganisms.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Carol Korzeniewski, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Texas Tech University, and Jiahe Xu for their assistance with thermal treatments. The authors would also like to thank Maasoomeh Jafari for her assistance with the thermogravimetric analysis. The SEM work was performed at the College of Arts and Sciences Microscopy, Texas Tech University. The author would like to thank Dr. Bo Zhao for her assistance on the SEM work. Thanks to Dr George Zhuo Tan, Department of Industrial, Manufacturing, & System Engineering, Texas Tech University, and Imtiaz Qavi for their assistance and access to the viscometer.

References

- Abo-zeid Y., Ismail N.S.M., McLean G.R., Hamdy N.M. A molecular docking study repurposes FDA approved iron oxide nanoparticles to treat and control COVID-19 infection. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anero M.L.A., Montallana A.D.S., Vasquez M.R., Jr. Fabrication of electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers loaded with zinc oxide particles. Results in Phys. 2021;25 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum S., Hashim M., Malik S.A., Khan M., Lorenzo J.M., Abbasi B.H., Hano C. Recent advances in zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for cancer diagnosis, target drug delivery, and treatment. Cancers. 2021;13:4570. doi: 10.3390/cancers13184570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atalla R.H., Isogai A. (2010). Celluloses. Elsevier. 2010:493–539. doi: 10.1016/B978-008045382-8.00691-2. Editor(s): Hung-Wen (Ben) Liu, Lew Mander, Comprehensive Natural Products II. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayodeji O.J., Ramkumar S. Effectiveness of face coverings in mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:3666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayodeji O.J., Hilliard T.A., Ramkumar S. Particle-size-dependent filtration efficiency, breathability, and flow resistance of face coverings and common household fabrics used for face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022;16(11) doi: 10.1007/s41742-021-00390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - After You Travel Internationally (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/after-travel-precautions.html. Accessed 9 December 2020.

- Chand N., Fahim M. Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering, Tribology of Natural Fiber Polymer Composites. Woodhead Publishing; 2008. Natural fibers and their composites, Editor(s): Navin Chand, Mohammed Fahim; pp. 1–58. 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Liu P., He J.H., Wang H.L., Zhang H., Wang X., Chen R. Nanofiber template-induced preparation of ZnO nanocrystal and its application in photocatalysis. Scientific Rep. 2021;11:21196. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00303-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau L., Asgarimoghaddam H., Alkie T., Jones A.J.B., Lum S., Mistry K., Aucoin M.G., DeWitte-Orr S., Musselman K.P. Effectiveness of antiviral metal and metal oxide thin-film coatings against human coronavirus 229E. APL Mater. 2021;9 doi: 10.1063/5.0056138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnadio A., Roscini L., Di Michele A., Corazzini V., Cardinali G., Ambrogi V. PVC grafted zinc oxide nanoparticles as an inhospitable surface to microbes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2021;128 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Megharbel S.M., Alsawat M., Al-Salmi F.A., Hamza R.Z. Utilizing of (zinc oxide nano-spray) for disinfection against “SARS-CoV-2” and testing its biological effectiveness on some biochemical parameters during (COVID-19 Pandemic)—” ZnO nanoparticles have antiviral activity against (SARS-CoV-2) Coatings. 2021;11:388. doi: 10.3390/coatings11040388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farouk F., Shebl R.I. Comparing surface chemical modifications of zinc oxide nanoparticles for modulating their antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type-1. Int. J. Nanopart. Nanotechnol. 2018;4:021. doi: 10.35840/2631-5084/5521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal V., Nilsson-Payant B.E., French H., Siegers J.Y., Yung W., Hardwick M., Velthuis A.J.W. Zinc-embedded polyamide fabrics inactivate SARS-CoV‑2 and influenza a virus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:30317–30325. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c04412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P., Elkins C., Long T.E., Wilkes G.L. Electrospinning of linear homopolymers of poly(methyl methacrylate): exploring relationships between fiber formation, viscosity, molecular weight and concentration in a good solvent. Polymer. 2005;46:4799–4810. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halder N.C., Wagner C.N.J. Separation of particle size and lattice strain in integral breadth measurements. Acta Crystallogr. 1966;20:312–313. doi: 10.1107/s0365110X66000628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi M., Abdel-Bar H.M., Elmowafy E., El-khouly A., Mansour M., Awad G.A.S. Investigating the internalization and COVID-19 antiviral computational analysis of optimized nanoscale zinc oxide. ACS Omega. 2021;6:6848–6860. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c06046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini M., Behzadinasab S., Chin A.W.H., Poon L.L.M., Ducker W.A. Reduction of Infectivity of SARS-CoV‑2 by Zinc Oxide Coatings. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021;7:5022–5027. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamnongkan T., Kaewpirom S., Wattanakornsiri A., Mongkholrattanasit R. Effect of ZnO Concentration on the Diameter of Electrospun Fibers from Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Composited with ZnO Nanoparticles. Key Eng. Mater. 2018;759:81–85. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.759.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LibreTexts. Infrared Spectra of Some Common Functional Groups (2021). https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/31529. Accessed 3 January 2022

- Lou L., Yu W., Kendall R.J., Smith E., Ramkumar S.S. Tensile testing and fracture mechanism analysis of polyvinyl alcohol nanofibrous webs. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020;2020:e49213. doi: 10.1002/app.49213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S.B., Jain M., Dobal P.S., Katiyar R.S. Investigations on solution derived aluminium doped zinc oxide thin films. Mater. Sci. Eng.: B. 2003;103:16–25. doi: 10.1016/S0921-5107(03)00128-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallakpour S., Azadi E., Hussain C.M. The latest strategies in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2021;45:6167. [Google Scholar]

- Manigandan S., Wu M., Ponnusamy V.K., Raghavendra V.B., Pugazhendhi A., Brindhadevi K. A systematic review on recent trends in transmission, diagnosis, prevention and imaging features of COVID-19. Process Biochem. 2020;98:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine . National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2020. Rapid Expert Consultations on the COVID-19 Pandemic.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556967 Apr 30. Rapid Expert Consultation on the Possibility of Bioaerosol Spread of SARS-CoV-2 for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 1, 2020) /Accessed 4 June 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parın F.N., Aydemir Ç.İ., Taner G., Yildirim K. Co-electrospun-electrosprayed PVA/folic acid nanofibers for transdermal drug delivery: Preparation, characterization, and in vitro cytocompatibility. J. Ind. Text. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1528083721997185. 152808372199718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parin F.N., Ullah S., Yildirim K., Hashmi M., Kim I.-S. Fabrication and characterization of electrospun folic acid/hybrid fibers: in vitro controlled release study and cytocompatibility assays. Polymers. 2021;13:3594. doi: 10.3390/polym13203594. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segneanu A.E., Gozescu I., Dabici A., Sfirloaga P., Szabadai Z. InTech; 2012. Organic Compounds FT-IR Spectroscopy, Macro To Nano Spectroscopy.https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/37659/InTech-Organic_compounds_ft_ir_spectroscopy.pdf Dr. Jamal Uddin (Ed.), Available at. Accessed on 3 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid O., Nasajpour M., Pouriyeh S., Parizi R.M., Han M., Valero M., Li F., Aledhari M., Sheng Q.Z. Machine learning research towards combating COVID-19: Virus detection, spread prevention, and medical assistance. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021;117 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirvanimoghaddam K., Akbari M.K., Yadav R., Al-Tamimi A.K., Naebe M. Fight against COVID-19: The case of antiviral surfaces. APL Mater. 2021;9 doi: 10.1063/5.0043009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S.K., Venkatraman S.S. Importance of viscosity parameters in electrospinning: Of monolithic and core–shell fibers. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 2012;32:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuneo I. Anti-viral vaccine activity of Zinc (II) for viral prevention, entry, replication, and spreading during pathogenesis process. Current Trends in Biomed. Eng. Biosci. 2019;19:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Turaga U., Singh V., Gibson A., Maharubin S., Korzeniewski C., Presley S., Smith E., Kendall R.J., Ramkumar S.S. Preparation and characterization of bioactive and breathable polyvinyl aclohol nanowebs using a combinational approach. Tappi J. 2016;15:655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zheng R., Liu Z., Ho H., Xu J., Ringer S.P. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO nanorods with hidden secondary phases. Nanotechnology. 2008;19 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/45/455702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhu M., Wei X., Yu J., Li Z., Ding B. A dual-mode electronic skin textile for pressure and temperature sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;425 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.130599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions (2020). https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions. Accessed 6 March 2021

- World Health Organization . 2022. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/ Accessed 2 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Pan W. Preparation of zinc oxide nanofibers by electrospinning. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006;89:699–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2005.00735.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Li Y., Zhang A.L., Wang Y., Molina M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020. 2020;117:14857–14863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009637117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]