Abstract

Understanding the regulatory network of cell fate acquisition remains a major challenge. Using the induction of surface epithelium (SE) from human embryonic stem cells as a paradigm, we show that the dynamic changes in morphology-related genes (MRGs) closely correspond to SE fate transitions. The marked remodeling of cytoskeleton indicates the initiation of SE differentiation. By integrating promoter interactions, epigenomic features, and transcriptome, we delineate an SE-specific cis-regulatory network and identify grainyhead-like 3 (GRHL3) as an initiation factor sufficient to drive SE commitment. Mechanically, GRHL3 primes the SE chromatin accessibility landscape and activates SE-initiating gene expression. In addition, the evaluation of GRHL3-mediated promoter interactions unveils a positive feedback loop of GRHL3 and bone morphogenetic protein 4 on SE fate decisions. Our work proposes a concept that MRGs could be used to identify cell fate transitions and provides insights into regulatory principles of SE lineage development and stem cell–based regenerative medicine.

Multiomics analysis at key stage of fate decision identifies a master regulator, GRHL3, driving surface epithelium commitment.

INTRODUCTION

Proper development of surface epithelium (SE) is essential for normal epidermis development and function. Although recent efforts have begun to investigate the stage-specific individual transcription factor and interconnecting transcription factor networks during epidermal commitment through in vivo and in vitro differentiation models (1, 2), it remains largely unknown about SE-specific regulatory networks and core transcription factors involved in SE commitment.

Lineage commitment during embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation requires chromatin reorganization and lineage-specific gene activation that is orchestrated by cis-regulatory networks (3–7). Large-scale epigenomic studies have shown that long-range cis-regulatory elements coordinate lineage-specific transcriptional programs by looping to their target promoters (5, 8–10). Thus, a comprehensive dissection of the interplay between these cis-regulatory elements and core transcription factors during the initiation of lineage commitment is required to fully understand the developmental transcriptional decisions.

Cell fate transitions are typically accompanied by morphology remodeling with diverse types of cells exhibiting distinct morphologies (11–14). Morphogenesis is driven by cell mechanics via cytoskeletal elements, as well as cellular adhesion, and matrix molecules and is highly correlated with cellular properties and functions (15–17). Specifically, microtubule-associated protein 2 is predominantly expressed in neurons and is crucial for neurogenesis (18). During the differentiation of ESC into epidermal cells, the intermediate filament keratin 8 (KRT8) and KRT18 are signature markers of the SE (19), and this keratin pair is replaced by KRT5 and KRT14 when SE further differentiate into basal keratinocytes (20, 21). Given that these cell morphology-related genes (MRGs) could be used to distinguish cell identities, it will be of interest to define cell fate transitions by changes in MRG pattern during lineage commitment.

Here, we determined the critical point for the fate transition from human ESC (hESC) to SE cells based on dynamic changes of MRGs and delineated cell-specific cis-regulatory element-promoter interactions in the initiation stage of SE differentiation. Among the cis-regulatory element-targeting transcription factors, grainyhead-like 3 (GRHL3) acted as an initiation factor for SE commitment by altering the global chromatin status, activating SE identity genes, and forming a positive feedback loop with bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4). Our work offers original evidence that links MRG features to cell fate transitions and provides a comprehensive resource for studying SE-specific regulatory elements that enable the investigation of regulatory principles during lineage commitment and the contributions to the advancement of regenerative therapy.

RESULTS

Identifying the phases of SE commitment

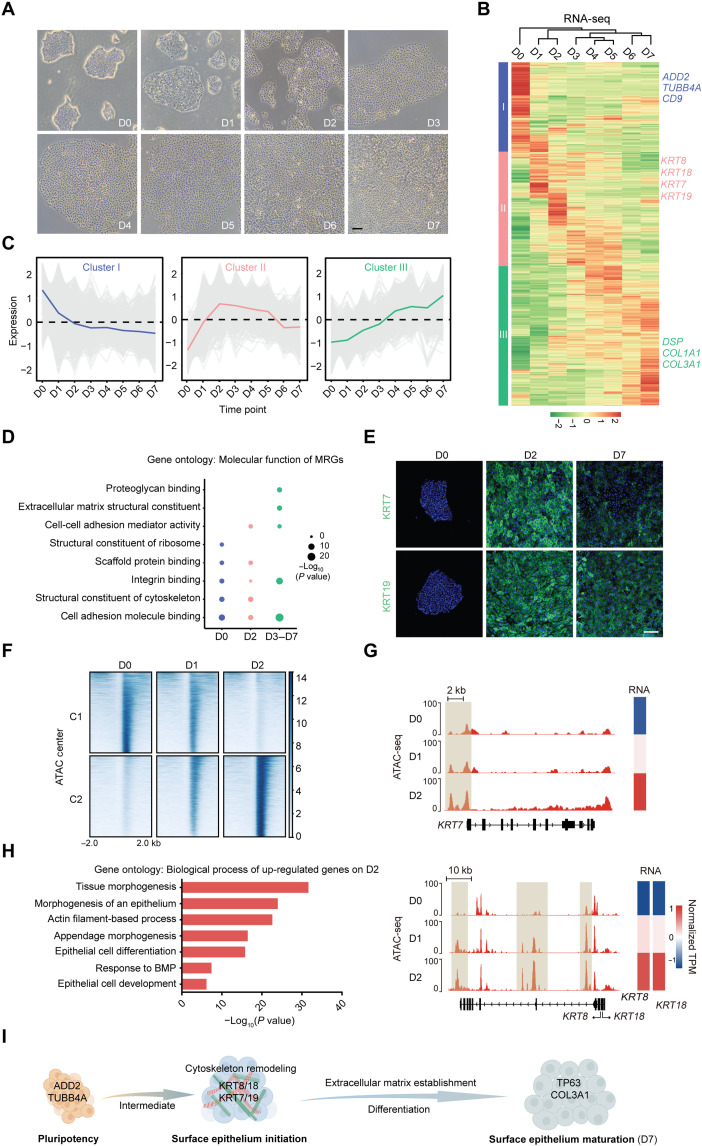

Cell fate transitions involve dynamic remodeling of the cell morphology. To explore the morphological changes that occur during lineage commitment, we used a modified model of directed differentiation of hESCs into SE cells. A nearly homogeneous population of SE cells was obtained and characterized on the basis of positive KRT8, KRT18, and tumor protein p63 (TP63) staining with undetectable expression of the ESC marker nanog homeobox (NANOG) on day 7 (D7; fig. S1, A and B). As differentiation proceeded, the cell morphology and the colony compactness underwent dynamic changes (Fig. 1A). MRGs associated with gene ontology categories related to the cytoskeleton, cell junction, cell adhesion, and cell matrix were packed to elucidate the correlation between cell morphology and lineage commitment. These MRGs were clustered into three groups based on the main temporal gene expression patterns observed during SE differentiation (Fig. 1, B and C, and table S2). Specifically, a cell membrane skeletal protein adducin 2 (ADD2) and a microtubule component tubulin beta class IVa (TUBB4A) in cluster I were only detected in hESCs (fig. S1, C and D). MRGs in cluster III, typified by desmoplakin (DSP) (an intermediate filament anchor) and collagen type III alpha 1 (COL3A1) (an extracellular matrix protein), were gradually up-regulated (fig. S1, C and D). These data confirmed that the process of SE commitment was accompanied by dynamic changes in MRG expression.

Fig. 1. Dynamic features of MRG identify cell fate transitions during SE lineage commitment.

(A) Phase contrast images of the differentiating hESCs during 7 days of culture. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Heatmap of MRG expression changes during SE differentiation. Hierarchical clustering yields three clusters of genes and four major groups of samples. The color bar shows the relative expression value [z score of TPM (transcripts per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads)] from the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). (C) The trend of expression changes of the three clusters identified from RNA-seq. (D) Gene ontology (molecular function) analysis of MRGs at each time point. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of KRT7 and KRT19 in the differentiated cells on D0, D2, and D7. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) K-means clustering analysis of differential open chromatin regions during the first 2 days of SE differentiation. The color bar shows the relative assay for transposase accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing(ATAC-seq) signal (z score of normalized read counts) as indicated. (G) Snapshots of genome browser showing chromatin accessibility at KRT7, KRT8, and KRT18 loci. Gene expression is also displayed in heatmaps (log2 TPM). The genome browser view scales were adjusted on the basis of the global data range. (H) Representative gene ontology terms (biological process) identified from the differentially expressed genes in D2 differentiated cells. (I) Schematic diagram of SE differentiation.

We further analyzed the characteristics of the MRG expression patterns using molecular function enrichment analysis. Cluster I MRGs were highly up-regulated in hESCs with a unique enrichment in the structural constituent of ribosome and were sharply down-regulated as differentiation progressed (Fig. 1, C and D). The cluster III MRGs were progressively up-regulated with enhanced molecular function in terms of integrin binding, cell adhesion molecule binding, and extracellular matrix structural constituent (Fig. 1, C and D). Specifically, the cluster II MRG expression levels peaked on D2 and declined gradually thereafter (Fig. 1C). Note that, although MRGs in both clusters I and II were enriched for structural constituent of the cytoskeleton and scaffold protein binding, the related genes differed in each cluster. That is, hESCs and D2 differentiated cells had distinct cytoskeletal components, indicating that marked cytoskeleton remodeling occurred during the early stage of SE differentiation. Among these cytoskeletal proteins, the established SE markers type I keratin KRT18 and type II keratin KRT8 and other members of the keratin family (type I keratin KRT19 and type II keratin KRT7, also known as simple epithelia markers) matched the pattern of cluster II (Fig. 1E and fig. S1, A, E, and F), demonstrating that the second day of differentiation was a critical transition phase of SE initiation.

Consistently, during the first 2 days of SE differentiation, the dynamic epigenetic landscape was characterized into two regulatory element clusters specific to hESCs (C1) and D2 differentiated cells (C2) (Fig. 1F), and the expression levels of genes located near these two clusters in D1 differentiated cells were moderate (fig. S1G). Specifically, pluripotency-related genes [NANOG and octamer-binding protein 4 (OCT4)] showed a marked decrease in chromatin accessibility and expression (fig. S1H), whereas SE markers (KRT7, KRT8, and KRT18) exhibited ascending trends (Fig. 1G). Moreover, the up-regulated genes in D2 differentiated cells (compared with hESCs) were significantly associated with epithelium morphogenesis and epithelial cell development (Fig. 1H). In comparison with differentiated cells on D2, the enriched genes in D7 SE cells were preferentially linked to extracellular matrix organization, cell junction and adhesion, and skin development (fig. S1I). The transcriptome of D7 SE cells in our system was similar to mouse epidermal progenitors at embryonic day 9 with SE lineage genes, such as KRT8, KRT18, KRT7, KRT19, TP63, etc. (fig. S1J). Together, these findings suggest that the dynamic features of MRG can be used to identify the SE fate transitions and that the process of SE differentiation could be divided into three stages (D0, pluripotency stage; D2, SE initiation stage; D3 to D7, SE differentiation-maturation stage) (Fig. 1I).

Cis-regulatory networks essential for SE initiation

Cell fate decisions are generally associated with profound changes in cis-regulatory elements, such as enhancers that coordinate cell-specific transcriptional programs via enhancer-promoter looping (3–5, 22). Thus, we integrated an analysis of multiomics data containing the three-dimensional genome, epigenome, and transcriptome of SE-initiating cells to comprehensively characterize the regulatory network of SE initiation (Fig. 2A).

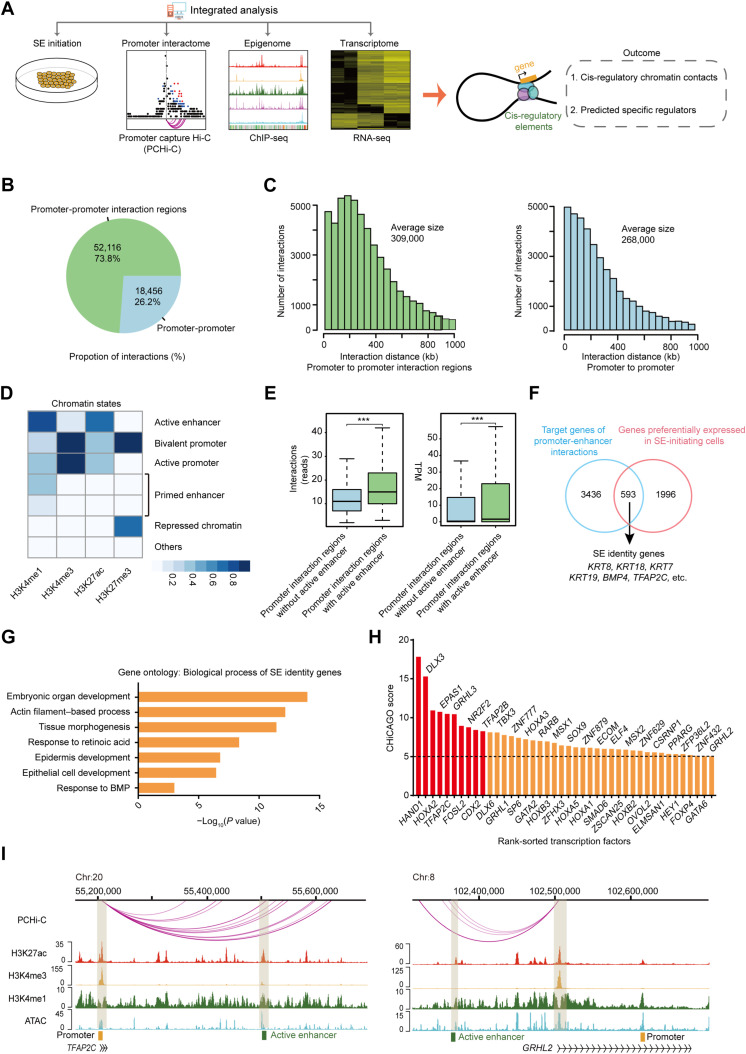

Fig. 2. Multiomics analysis delineates the cis-regulatory network of SE initiation.

(A) Scheme of the research route and method in this study. (B) Pie chart of the number and percentage of promoter-promoter interactions and promoter-promoter interaction regions interactions of SE-initiating cells. (C) Histograms of the distribution of the distance between promoter and promoter interaction regions and between promoter and promoter of SE-initiating cells. (D) Heatmap of different ChromHMM state enrichment of SE-initiating cells. The blue shading depicts the average intensity of a particular epigenetic mark across each chromatin state. The color scale shows the relative enrichment. (E) Left: Box plot of the number of interactions in promoter interaction regions with or without active enhancer. Right: Box plot of the target gene expression level of promoter interaction regions with or without active enhancer ***P < 0.001 from two-way ANOVA. (F) Venn diagram showing overlap between SE identity genes and genes highly expressed in SE-initiating cells. (G) Representative gene ontology terms (biological process) identified from SE identity genes. (H) Histogram of CHiCAGO scores of the candidate transcription factors. (I) Genome browser view of H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, ATAC-seq signals, and promoter-enhancer interactions at TFAP2C and GRHL2 loci in SE-initiating cells. Chromatin states are indicated (active enhancer, green; active promoter, yellow).

Promoter capture Hi-C was performed to obtain a high-resolution view of promoter-anchored chromatin interactions in SE-initiating cells. We identified 70,572 significant chromatin interactions, including numerous promoter chromatin loops at the loci of the SE markers KRT8, KRT18, and KRT19 (Fig. 2B and fig. S2A). Notably, most of these interactions occurred between the promoters and promoter interaction regions (Fig. 2, B and C). To identify the active enhancer, we inferred chromatin states in SE-initiating cells using ChromHMM (Fig. 2D and fig. S2B). Compared to the promoter interaction regions without enhancer, promoter-enhancer interactions exhibited higher levels in the number of interactions and the expression of their target genes (Fig. 2E and fig. S2, C and D), highlighting a positive regulatory role of cis-regulatory networks of enhancer-promoter contacts. We next focused on the contribution of the cis-regulatory networks in cell-type specificity. By overlapping target genes of the cis-regulatory network and highly expressed genes at the SE initiation stage, we identified 593 common genes and defined them as SE identity genes (Fig. 2F and table S3). As characterized by gene ontology analysis, SE identity genes displayed significant association with epithelium development, actin filament–based process, and tissue morphogenesis (Fig. 2G), revealing a potential role of SE identity genes in SE fate determination.

To identify the master transcription factors that drive SE initiation, we screened 42 candidate transcription factors from SE identity genes and ranked them by CHiCAGO score (Fig. 2H). Notably, several transcription factors have already been identified as master regulators of epithelial development, including transcription factor AP-2 gamma (TFAP2C) and GRHL2 (Fig. 2I), which are known for their critical role in SE development (1, 23); SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), which functions as a pioneer factors in the skin epithelial cell lineage (24); and CDX2, which is required for intestinal epithelial cell development (25). Among the top 10 transcription factors, the expression patterns of heart and neural crest derivatives expressed 1 (HAND1), GRHL3, and caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) were all similar to that of TFAP2C, which increased sharply in the SE initiation stage and decreased rapidly in the SE maturation stage (fig. S2E).

GRHL3 opens chromatin and mediates SE identity gene expression

GRHL3 was chosen to investigate its role in determining the fate of SE. We first generated GRHL3-knockout hESCs using CRISPR-Cas9 (fig. S3A). Notably, GRHL3-knockout differentiated cells lost epithelial-like morphology with undetectable KRT18 (Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, these cells also showed a significant reduction in the expression of SE genes including KRT7, KRT8, KRT18, KRT19, TFAP2C, and GRHL2 and up-regulation of several neural genes (PAX6, CDH2, and EPHA7) (Fig. 3B and fig. S3B) (26–28), supporting an essential role for GRHL3 in SE initiation. This was also validated by the assay for transposase accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) and gene set enrichment analysis, which showed substantially decreased of chromatin accessibility around SE identity gene loci, and an extensive down-regulation of SE identity genes in GRHL3-knockout differentiated cells (Fig. 3, C to E, and fig. S3C).

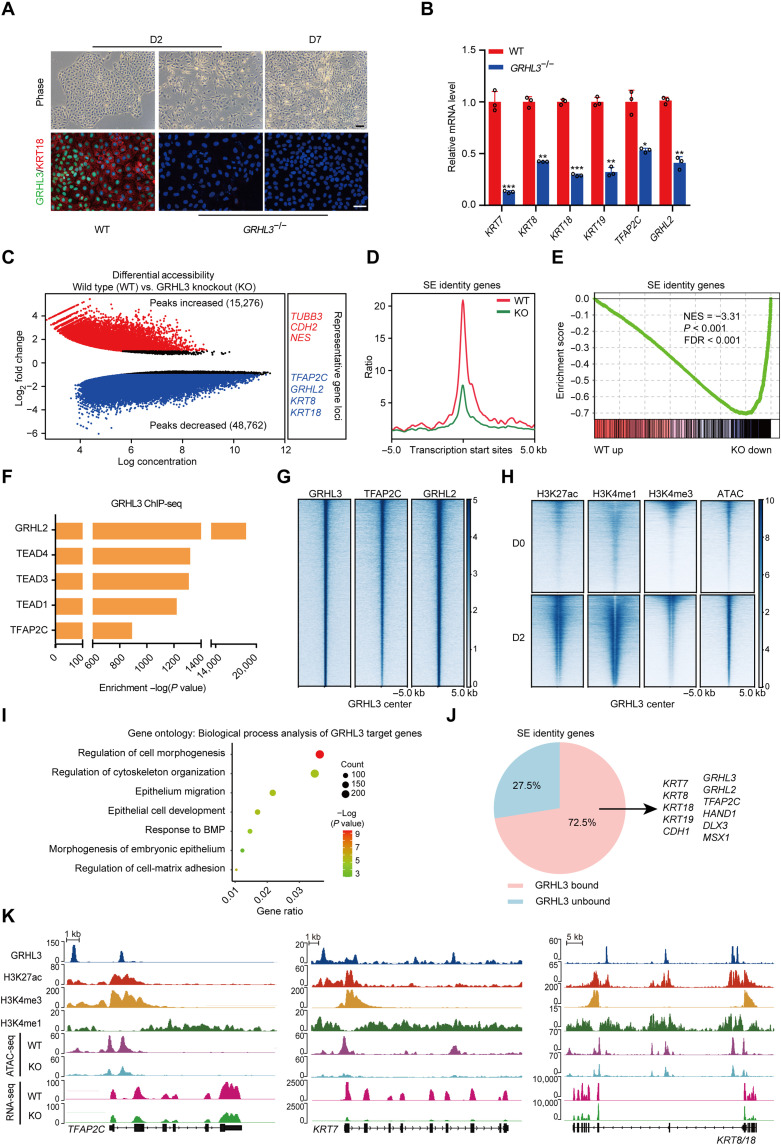

Fig. 3. GRHL3 is required to activate SE identity genes through opening their chromatin accessibilities.

(A) Wild-type (WT) and GRHL3-knockout hESCs during SE differentiation. Top: Phase contrast images. Bottom: Immunofluorescence staining of GRHL3 (green) and KRT18 (red). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of representative genes in wild-type and GRHL3-knockout hESCs after 2 days of differentiation. qRT-PCR values were normalized to the values in wild-type group. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; t test). (C) Scatterplot of differential accessibility in wild-type versus GRHL3-knockout (KO) hESCs after 2 days of differentiation. Sites identified as significantly differentially bound [log2 fold change > 1 or < −1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05] are shown in color (red, peaks increased; blue, peaks decreased). (D) Metaplots of average ATAC-seq density around the SE identity genes in wild-type and GRHL3-knockout hESCs after 2 days of differentiation. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis of the SE identity gene set in the gene expression matrix of wild-type and GRHL3-knockout hESCs after 2 days of differentiation. NES, normalized enrichment score. (F) Enrichment of transcription factor motifs identified by HOMER at GRHL3 peaks. (G) Heatmaps of the binding signals of TFAP2C and GRHL2 at the center of GRHL3 peaks. (H) Heatmaps of H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and ATAC-seq signals at GRHL3 peaks in hESCs and SE-initiating cells. (I) Gene ontology (biological process) analysis for the GRHL3 putative target genes. The GRHL3 peaks were annotated as follows: The intergenic peaks were assigned to the closest genes, and the intragenic peaks were assigned to those genes. (J) Pie chart of the percentages of SE identity genes with or without GRHL3 binding in SE-initiating cells. (K) Genome browser view of H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, GRHL3, ATAC-seq, and RNA-seq signal at TFAP2C, KRT7, and KRT8/18 loci.

To further dissect the contribution of GRHL3 in SE commitment, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq). The distribution analysis demonstrated that GRHL3 binding sites were predominantly located in intergenic and intronic regions, away from the transcription start sites of the target genes (fig. S3, D and E). A signature motif for GRHL3 was identified, and a high degree of conservation was observed between the sequence of this motif and that of GRHL2 (fig. S3F). The motifs for SE regulators, such as TFAP2C and GRHL2, were coenriched at GRHL3 binding sites (Fig. 3F). These two transcription factors were also apparently bound to GRHL3 binding sites, suggesting that GRHL3 may cooperate with these factors to mediate SE initiation (Fig. 3G).

Furthermore, epigenetic modifications in the GRHL3 binding sites were determined and shown to have a higher enrichment of active histone marks in SE-initiating cells, such as H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 (Fig. 3H), implying that the binding sites of GRHL3 had a higher potential for transcription and played pivotal roles in SE initiation. As expected, we observed that the target genes of GRHL3 significantly up-regulated in SE-initiating cells and linked to pan-epithelial development biological processes, such as morphogenesis, cytoskeleton organization, cell matrix adhesion, and migration (Fig. 3I, fig. S3G, and table S4). Notably, the vast majority of SE identity genes (72.5%) showed the binding of GRHL3, indicating that GRHL3 activates SE identity genes mainly through direct binding (Fig. 3J). Specifically, GRHL3 bound to loci near TFAP2C, KRT7, and KRT8/18, enhancing their chromatin accessibilities and gene expression, whereas in the absence of GRHL3, their chromatin accessibilities and gene expression were notably interfered (Fig. 3K). These data highlight the importance of GRHL3 in opening SE identity gene chromatin and activating their expression.

GRHL3 drives SE commitment

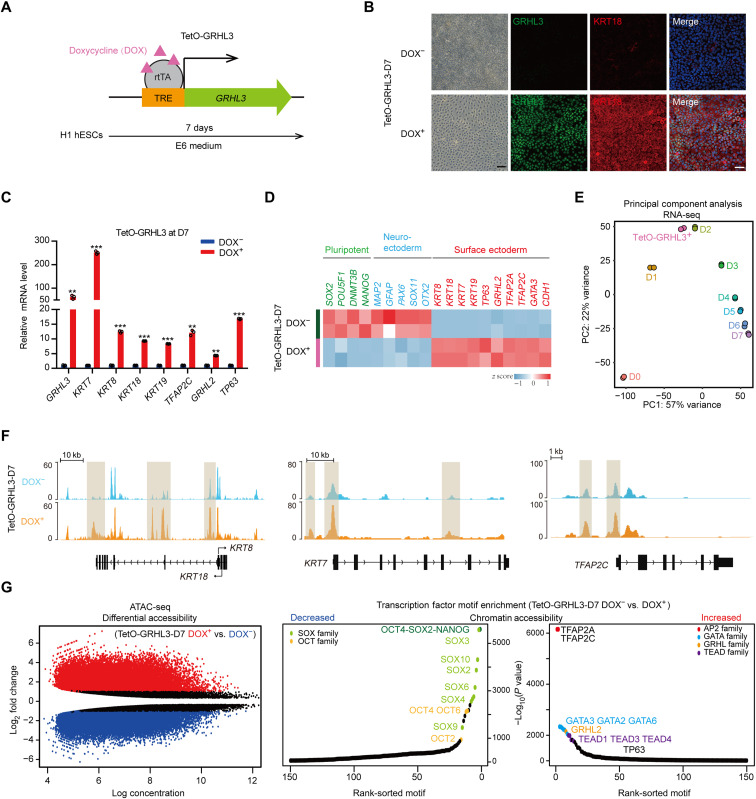

Given the vital role of GRHL3 in SE initiation, we investigate whether GRHL3 could drive SE differentiation. To this end, a doxycycline-inducible system was used to overexpress GRHL3 without addition of retinoic acid (RA)/BMP4 (Fig. 4A). After 7 days of doxycycline induction, the GRHL3-expressed cells (hereafter “TetO-GRHL3+”) showed a homogeneous KRT18+ epithelial-like morphology accompanied by significantly higher expression of SE marker genes (Fig. 4, B to D). In contrast, both the pluripotency- and neuroectoderm-related genes were significantly attenuated in these cells (Fig. 4D). Gene ontology analysis showed that genes that were preferentially expressed in TetO-GRHL3+ cells were associated with epithelium development biological processes, such as extracellular matrix organization, and epithelium morphogenesis (fig. S4A and table S5). Notably, principal components analysis (PCA) revealed that the transcriptome landscape of TetO-GRHL3+ cells was highly similar to that of SE-initiating cells (Fig. 4E). In particular, both cell types also had similar MRG expression patterns (fig. S4B). Furthermore, changes in chromatin accessibility following GRHL3 induction revealed substantial increase ATAC-seq signals at the KRT7, KRT8, KRT18, and TFAP2C loci in TetO-GRHL3+ cells, compared to those in TetO-GRHL3− cells (Fig. 4F). Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis for the differentially accessible regions revealed significant increase in the binding of the GRHL, activating protein 2 (AP2), and GATA binding protein (GATA) families and a decrease in the binding of critical transcription factors associated with hESC pluripotency (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that GRHL3 was sufficient to drive acquisition of SE phenotype.

Fig. 4. GRHL3 induces SE commitment.

(A) Schematic diagram of establishment of a TetO-GRHL3 doxycycline-inducible expression system in hESC. Cells were induced with doxycycline for 7 days. TRE, tetracycline response element; rtTA, reverse tetracycline transactivator. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of GRHL3 (green) and KRT18 (red) in TetO-GRHL3+ and TetO-GRHL3− cells. Left: Phase contrast images. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes in TetO-GRHL3+ and TetO-GRHL3− cells. qRT-PCR values were normalized to the values in TetO-GRHL3− cells. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; t test). (D) Heatmap of germ layer–specific gene expression levels in TetO-GRHL3+ and TetO-GRHL3− cells. (E) PCA of RNA-seq data of TetO-GRHL3+ cells and hESCs at each time points during SE differentiation. (F) Genome browser tracks comparing ATAC-seq signal at KRT8/18, KRT7, and TFAP2C loci in TetO-GRHL3+ and TetO-GRHL3− cells. (G) Left: Scatterplot of differential accessibility in TetO-GRHL3+ versus TetO-GRHL3− cells. Sites identified as significantly differentially bound are shown in color (red, peaks increased; blue, peaks decreased). Right: Transcription factor motif enrichment in the regions of differential accessibility in TetO-GRHL3+ versus TetO-GRHL3− cells. TEAD, TEA domain transcription factor.

To validate whether TetO-GRHL3+ cells could differentiate into keratinocytes, we further cultured the cells in keratinocyte maturation medium. As expected, TetO-GRHL3+ cells successfully differentiated into keratinocytes with KRT5, KRT14, and TP63 expression and decreased KRT8 and KRT18 expression (fig. S4, C and D).

Positive feedback regulation of BMP4 and GRHL3 during SE commitment

Because GRHL3 induced SE differentiation without additional triggers, we next dissected how GRHL3 impel SE determination. By integrating our promoter capture Hi-C data from TetO-GRHL3+ cells and GRHL3 ChIP-seq data from SE-initiating cells, we observed that GRHL3 binding was accompanied by promoter interaction events and that it appeared more frequently at promoter interaction regions (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S5A). Combining the GRHL3-mediated promoter interactome with transcriptome data identified 607 up-regulated genes in TetO-GRHL3+ cells whose promoters were involved in GRHL3-mediated promoter interactions, including the SE-specific keratins (KRT7, KRT19, KRT8, and KRT18) and key SE regulators (GRHL3 and TFAP2C) (Fig. 5C and fig. S5B). In particular, these genes were enriched for several signaling pathways (BMP, WNT, and HIPPO), among which the BMP signaling was dominant (Fig. 5, D and E). By profiling the expression changes of BMP family members during SE initiation, we found that BMP4 expression was the most prominent in SE-initiating cells and TetO-GRHL3+ cells, suggesting the involvement of BMP4 activation in SE initiation (fig. S5C).

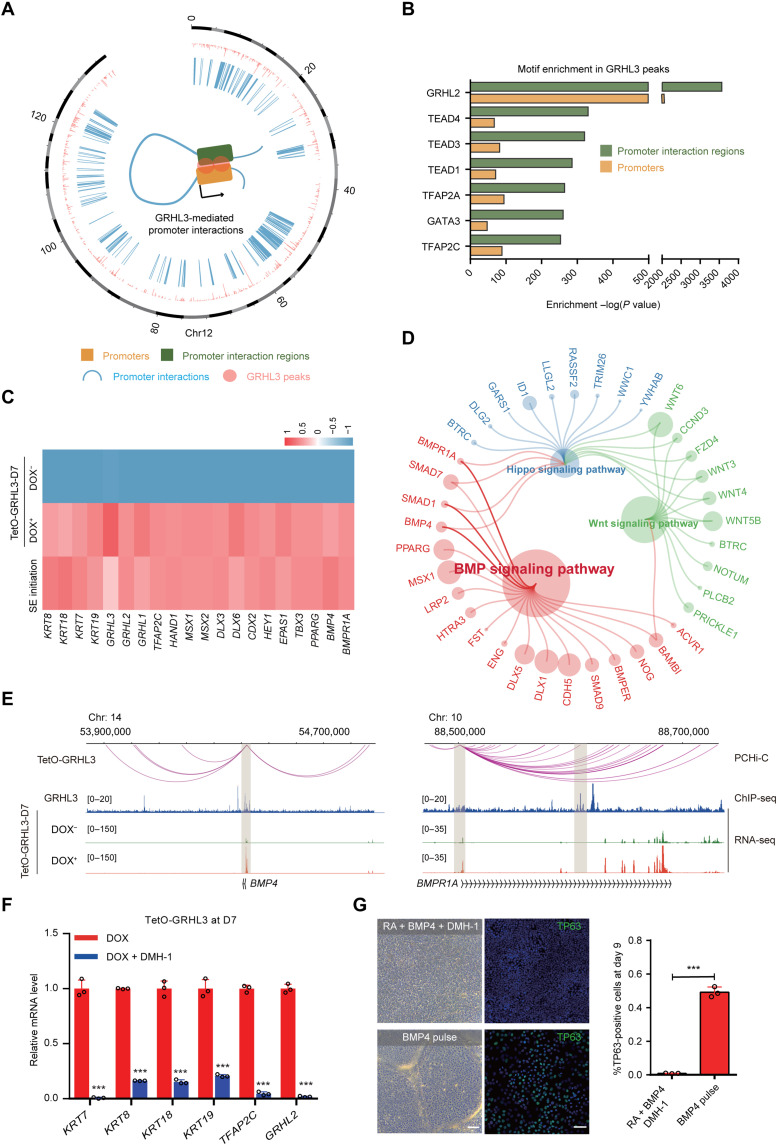

Fig. 5. Positive feedback of the BMP4-GRHL3 axis mediated SE commitment.

(A) Circos diagram of genomic promoter associated interactions mediated by GRHL3 in TetO-GRHL3+ cells. The pink color refers to GRHL3 peak. The blue color refers to promoter interactions. (B) Enrichment of transcription factor motifs identified by HOMER in GRHL3 peaks of promoter interaction regions or promoters. (C) Heatmap showing expression levels of representative genes in SE-initiating cells, TetO-GRHL3+ and TetO-GRHL3− cells. (D) Pathway enrichment analysis of representative genes in TetO-GRHL3+ cells. (E) Genome browser view of promoter interactions, GRHL3, and RNA-seq signals at BMP4 and BMPR1A loci. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes in TetO-GRHL3+ cells with or without DMH-1 for 7 days. qRT-PCR values were normalized to the values in control cells. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; ***P < 0.001; t test). (G) Phase contrast images and TP63 staining of the differentiated hESCs after 9 days of culture. Top: hESCs treated with RA/BMP4/DMH-1. Bottom: hESC treated with a 1-day pulse of BMP4. Right: Quantification of the percentage of TP63+ cells. Values are shown as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; ***P < 0.001; t test). Scale bars, 100 μm.

We then used dorsomorphin homolog 1 (DMH-1), an inhibitor of BMP, to investigate the regulatory interaction between BMP4 signaling and GRHL3 during SE commitment. Notably, DMH-1–treated TetO-GRHL3+ cells failed to express the SE markers, KRT7, KRT8, KRT18, and KRT19, and SE regulators, TFAP2C and GRHL2, indicating that BMP4 signaling is essential for GRHL3-induced SE initiation (Fig. 5F and fig. S5D). DMH-1 also remarkably suppressed the expression of key SE elements during SE differentiation, including GRHL3, suggesting that GRHL3 functions as a downstream regulator of BMP4 signaling (fig. S5, E and F). After interrupting the BMP pathway, the differentiated hESCs failed to acquire an epithelial-like morphology, and TP63 expression was undetectable (Fig. 5G). Unexpectedly, the percentage of TP63+ cells markedly increased by 1 day of BMP4 stimulation, highlighting the guiding role of BMP4 signaling in SE commitment (Fig. 5G). Together, these results demonstrate that positive feedback loop occurs between BMP4 and GRHL3 and that this loop is required for SE commitment.

DISCUSSION

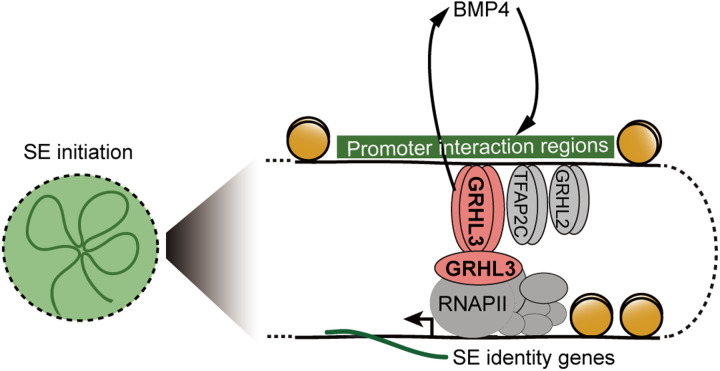

Significant efforts have been made to identify the lineage-determining transcription factors that can drive the initiation of cell fate commitment. Here, by monitoring the dynamic changes in MRGs, we defined the initiation stage during SE differentiation, which enabled a comprehensive evaluation of previously uncharted cis-regulatory elements and specific transcription factors, of which GRHL3 was unexpectedly found as an “initiation factor” for SE commitment (Fig. 6). Our study offers an improved strategy for unraveling the principles of cell fate decisions, highlights the cell-specific interactions occurring between cis-regulatory elements and promoters, and advances the field of epigenetics in the control of SE lineage specification.

Fig. 6. A proposed mechanical model of SE initiation.

An early initiation factor, GRHL3, drives SE initiation by priming chromatin accessibility and activating the SE identity gene expression. A positive feedback loop between GRHL3 and BMP4 controls SE commitment.

Cell morphological changes occur in various biological processes. Microtubules assembled and formed a spindle-shaped apparatus around the mitotic chromosomes in dividing cells (29), while the destruction of the actin cytoskeleton promotes programmed cell death and leads to cell shrinkage, which is a ubiquitous feature of apoptosis (30, 31). Here, we demonstrated that MRGs are closely intertwined with cell fate transitions. Dynamic changes in MRGs distinguished the process of in vitro SE differentiation into pluripotency, initiation, and maturation stages. Of these, the marked cytoskeleton remodeling, including the early onset of expression of two pairs of intermediate filament keratins in simple epithelia (KRT7/19 and KRT8/18), contributed to the definition of the SE initiation stage. As the SE matures, the expression of MRGs associated with epithelial basement membrane components and extracellular matrix structural constituents, such as COL1A1 and COL3A1, gradually became dominant. However, identifying cell fate transition based on MRG pattern may be inadequate, and more cell differentiation models are required to further validate this correlation.

A major highlight of this work is that we portrayed the promoter interactions mapping of the SE initiation stage. These chromatin interactions identified promoter interaction regions with active enhancer that are enriched for epigenomic features, such as H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, which was consistent with the results of several recent elegant studies, demonstrating that forced looping of enhancers to promoters induces gene activation (4, 5, 22). By integrating analysis of the promoter interactions, epigenomics, and transcriptomic datasets, we identified a previously unknown master regulator, GRHL3, and a set of genes, SE identity genes from the cis-regulatory networks, which were closely associated with the epithelial development and contributed to cellular identity. Specifically, GRHL3 binding was found to lead to nucleosome displacement and deposition of the H3K4me1 and H3K27ac marks, which was consistent with previous reports showing that GRHL family members have the characteristics of pioneer factors (32).

Notably, the peaks of GRHL3 and TFAP2C expression and substantial remodeling of the scaffold proteins occurred at the SE initiation stage, rather than a gradual increase in these key components across the differentiation process, suggesting that the initiation of the cell fate determination is a relatively rapid and intense process with the stimulation of morphogens. Recent work on early commitment revealed that a 7-day treatment with BMP4 failed to induce hESC differentiation into SE (33). In this study, SE differentiation could be triggered by a 1-day pulse of BMP4, suggesting that long-term BMP4 stimulation may result in a cross-inhibition of the cell fate transition, trapping the differentiated cells in an intermediate state between pluripotency and SE initiation. However, the differentiation efficiency of the BMP4 pulse was lower than that of RA/BMP4 and GRHL3 induction. Therefore, we speculate that factors other than BMP4 signaling are required to synergistically regulate SE commitment, especially the elimination of unnecessary BMP4-activating genes that may counteract the initiation of SE differentiation. It will be interesting to clarify the precise mechanisms underlying the interactions of core transcription factors and morphogen signals in future studies.

The proper development of tissues from germ layers relies on their regulatory interactions. Surface ectoderm adhesion plays an essential role in neural tube closure, and deficiency of integrin subunit beta 1 (ITGB1) in surface ectodermal cells leads to open spina bifida (34). During craniofacial development, TFAP2A and TFAP2B within the facial ectoderm mediate ectodermal-mesenchymal communication through WNT signaling pathway, which is critical for growth of neural crest–derived craniofacial bone and cartilage (35). Thus, investigating the characteristics and signaling pathways of SE could also uncover the regulatory mechanism for the development of adjacent tissue layers.

The single-layered SE is the basis for the formation of epidermis. In the presence of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), SE can differentiate into keratinocytes (1), which further initiate the epidermal stratification program to establish a multilayered skin. In addition, SE also has the potential to differentiate into other ectodermal tissues, including corneal and oral epithelium, hair follicles, and mammary glands. The specification of these ectodermal appendages depends on various signaling molecules in the environment. Notably, several morphogens have been shown to play important roles in epithelial development. FGF8, nodal growth differentiation factor (NODAL), and BMP4 are known to be essential mediators of oral surface ectoderm specification (36, 37), while secreted frizzled related protein 2, Dickkopf-1, BMP4, and transforming growth factor–β function to promote ocular surface ectoderm commitment (38, 39). Therefore, we speculate that tissue-specific lineages could be obtained from SE with the synergetic action of morphogens, which will be of great benefit to regenerative medicine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

hESCs culture

H1 hESCs (XY) and modified cell lines were cultured in mTeSR1 (STEMCELL Technologies) using hESC-Qualified Matrix (Corning). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged every 3 to 4 days. Cells were routinely screened for mycoplasma.

In vitro differentiation of hESCs into keratinocyte

For SE differentiation, H1 hESCs were digested into colonies of 100 to 200 μm in diameter and seeded onto Matrigel-coated plates. The next day, mTeSR1 medium was changed to Essential 6 medium (E6; Gibco) supplemented with recombinant human BMP4 (5 ng/ml; R&D Systems) and 1 μM RA (R&D Systems). For keratinocyte maturation, after 7 days of E6 differentiation, the E6 medium was further replaced with Defined Keratinocyte serum-free medium (Gibco) with growth supplements containing EGF (Millipore) and FGF (R&D Systems). Medium was changed every 2 days.

Generation of GRHL3-knockout cell line

We used CRISPR-Cas9–mediated genome editing to generate GRHL3-knockout hESC lines. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) for Cas9 nicking were designed using the CRISPR Design Tools (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no) and cloned into the LentiCRISPRv2 plasmid. H1 hESCs were infected by lentivirus and selected with puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 48 hours. Surviving hESCs were digested with accutase (STEMCELL Technologies) into single cells and maintained in mTeSR1 supplemented with the Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 (Tocris). Individual clones were picked and expanded individually, and knockout clones were verified by Sanger sequencing, Western blotting, and immunofluorescence. The sequences of gRNA are as follows: GRHL3-knockout gRNA, GTAATCATAGAGGAAGCTCA.

Generation of GRHL3-inducible hESCs

To control GRHL3 expression in an inducible fashion, ESCs containing doxycycline-inducible GRHL3 (TetO-GRHL3) were generated by inserting GRHL3 cDNA into a lentiviral vector pTSB-Tight-mcherry-EF1-tetR-F2A-Puro containing an elongation factor 1 (EF1) promoter–driven rtTA-F2A-PURO cassette and a tetracycline response element promoter–driven transgene expression cassette. Stable lines containing TetO-GRHL3 were generated by lentiviral infection and selected with puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 48 hours.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cDNA preparation, the PrimeScript Real-Time Master Mix Kit (Takara) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed on a real-time detection system using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad). PCR conditions included 1 cycle of 95°C for 3 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a normalization control. A list of the primer used is provided in table S1.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche). Proteins were run on a 10% Criterion TGX gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane before with 3% skim milk in tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20. Primary antibodies used were against GRHL3 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA059960; 1:1000) and GAPDH (Abcam, ab9485; 1:1000).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 4% polyformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, permeabilized, and blocked using phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. Following overnight incubation with primary antibodies, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were then counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were GRHL3 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA059960; 1:500), KRT8 (Invitrogen, MA514428; 1:500), KRT18 (Invitrogen, MA512104; 1:500), KRT7 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4465S; 1:500), KRT19 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MS-1902-P; 1:1000), NANOG (GeneTex, GTX100863; 1:500), TP63 (GeneTex, GTX102425; 1:500), ADD2 (Proteintech, 14640-1-AP; 1:500), TUBB4A (Abcam, ab179509; 1:500), DSP (Proteintech, 25318-1-AP; 1:500), and COL3A1 (Abcam, ab184993; 1:500). Secondary antibodies were from the Alexa Fluor series (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000).

RNA sequencing library preparation and data processing

The RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) libraries were prepared using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit (Illumina) and sequenced to a depth of 30 million reads using a HiSeq X10-PE150 system (Illumina). Raw reads were evaluated for quality using FASTQC 0.11.5 (40) and were trimmed to remove adaptor sequences using Trimmomatic 0.39 tools (41). Reads were aligned to the human hg19 reference genome by STAR 2.6.1 (42) and quantified using RSEM-1.3.0 (43). Differentially expressed genes with a fold change of ≥2 and a false discovery rate (FDR) of ≤0.05 were determined using DESeq2 1.20.0. The identified MRGs were differentially expressed between at least two time points (44). The RNA-seq data were from two biological samples.

Public transcriptome data of mouse epidermal progenitors at embryonic day 9 were downloaded, evaluated for quality using FASTQC 0.11.5 (40), and trimmed to remove adaptor sequences using Trim Galore 0.5.0 tools. Reads were aligned to the mouse mm10 reference genome by STAR 2.6.1 (42) and quantified using RSEM 1.3.0 (43).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing

Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28906) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium for 10 min at room temperature. Formaldehyde was then quenched with 125 mM glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, 50046) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were lysed in sonication buffer [50 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS]. Chromatin was sheared with Covaris M220 focused-ultrasonicator to an average DNA fragment length of 200 to 500 base pairs (bp). Chromatin was then diluted in lysis buffer without SDS and immunoprecipitated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The immunocomplexes were captured with Protein A and Protein G magnetic beads (1:1, Invitrogen). After three washes with sonication buffer, two washes with low-salt wash buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, and 0.5% Na-deoxycholate], and one wash with TE buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA], chromatin was then eluted from beads and de–cross-linked with 1% SDS in TE for 4 hours. After 1-hour digestion at 37°C with proteinase K (Invitrogen) and ribonuclease A (Invitrogen), DNA was purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN), and then the purified DNA was used to prepare libraries using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, KK8502) for Illumina PE150 sequencing following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The antibodies used for ChIP-seq (5 μg per ChIP) are as follows: anti-H3K27ac (Millipore, 07-360), anti-H3K27me3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9733S), anti-H3K4me1 (Active Motif, 39297), anti-H3K4me3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9751S), anti-GRHL3 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA059960), anti-GRHL2 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA004820), anti-TFAP2C (Abcam, ab218107).

Assay for transposase accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing

The ATAC-seq was performed as previously described (45). Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were digested, collected, and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, and 0.1% Tween 20] for 5 min. Tn5 transposition of nuclei pellets was carried out at 37°C for 30 min using the TruePrep DNA Library Prep Kit (Vazyme Biotech, TD501). The transposed DNA fragments were purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and then amplified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ATAC-seq libraries were sequenced with an Illumina HiSeq X10 instrument.

Data analysis of ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq

ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq paired-end reads were trimmed to remove adaptor sequences using Trimmomatic 0.39 tools (41) and then aligned to human hg19 reference genome using BWA 0.7.17 software (46), followed by filtering of uniquely mapped reads using the Picard MarkDuplicates 2.18.16 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq peak detection was performed using MACS2 2.1.1 (47); for sharp peaks, the option -f BAMPE -B -SPMR -q 0.001 -call-summits -fix-bimodal -seed 11521 -extsize 200 was used; for broad peaks (H3K27me3 and H3K4me1), the option -f BAMPE -B --SPMR --fix-bimodal --extsize 500 --broad --broad-cutoff 0.1 --seed 11521 was used; and for ATAC peaks, the following parameters were used: -f BAMPE -B --SPMR -q 0.001 --call-summits –nomodel --shift -100 --extsize 200.

The deepTools multiBamSummary was used to analyze the Pearson correlation coefficient based on the read coverages of the genomic region of the BAM files. Two independent biological replicates displayed a high degree of similarity. Peaks from replicate samples were merged by HOMER mergePeaks command, and bigWig files were created from scaled bedGraph files generated by MACS2. Heatmaps and profiles for normalized ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq were generated using deepTools 3.0.2 (48). Peak annotation was performed by the HOMER’s annotatePeaks.pl program (49) with the default parameters. BEDTools (50) intersect was used to statistically analyze the rate of overlap between the two sets of genomic features.

Promoter capture Hi-C

Promoter capture Hi-C libraries were performed as previously described (51, 52). Briefly, cells were cross-linked for 10 min with 1% formaldehyde and quenched with 0.2 M glycine final concentration for 5 min at room temperature and then on ice for 15 min. The cross-linked cells were then lysed, and the cross-linked chromatin were digested overnight by Hind III [New England Biolabs (NEB)] restriction enzyme and marked with biotin-14–2′-deoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate (Invitrogen) and ligated using T4 DNA ligase (NEB). Chromatin was then de–cross-linked overnight, and the ligated DNA was purified using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After removal of biotin from unligated DNA ends, purified DNA was sheared to 300- to 600-bp fragments. The purified DNA was further blunt end–repaired, A-tailed, and SureSelect adaptor–added, followed by purification through biotin-streptavidin–mediated pull-down and PCR amplification.

Capture Hi-C of promoters was carried out with SureSelect XT Library Prep Kit ILM using the custom-designed biotinylated RNA capture bait library. The Hi-C library DNA was mixed with the custom paired-end blockers following the manufacturer’s instructions (Agilent Technologies). After library enrichment, a postcapture PCR amplification step was carried out using paired-end (PE) PCR 1.0 and PE PCR 2.0 primers (Illumina). Paired-end reads for Promoter capture Hi-C libraries were obtained with NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina).

Data processing for promoter capture Hi-C

Raw sequencing reads were processed using HiCUP pipeline (53), which mapped the positions of di-tags against the human hg19 reference genome, filtered out experiment artifacts, such as circularized reads and religations, and removed all duplicate reads. Interaction strength scores were computed using CHiCAGO pipeline (54). All trans-interactions and the interactions spanning more than 1 Mb were discarded. Interactions were merged from biological replicates using CHiCAGO, and those with a CHiCAGO score of ≥5 were considered in our study. Genome-wide interactions were visualized using WashU EpiGenome browser (55).

ChromHMM analysis

A hidden Markov model–based method was implemented using ChromHMM 1.10 (56) with default settings. Genome-wide chromatin was segmented into seven chromatin states based on the following histone modification ChIP data: H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, and H3K27me3. Specifically, active enhancers were defined by the presence of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac and the absence of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3. Active promoters were defined by the presence of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac and the absence of H3K27me3 and H3K4me1.

Motif enrichment analysis

The HOMER findMotifsGenome function (49) was used for motif analysis with default parameters. Motifs were analyzed on ±1000-bp sequences around the peak centers. Motifs enriched in ATAC peaks were found on ±50-bp sequences around peak centers. The results of known and de novo motif enrichments were presented.

Gene ontology analysis

The online software Metascape (57) (www.metascape.org) was used for gene ontology enrichment analysis with pvalueCutoff = 0.01 and qvalueCutoff = 0.05.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (58) was performed according to the developer’s protocol with weighted enrichment statistic and signal-to-noise ranking metric. The normalized enrichment score, nominal P value, and FDR Q value reflected the significance of enrichment level.

Differential ATAC-seq peak analysis

DiffBind (59) package from Bioconductor with the default parameters was used to identify differentially accessible peaks between two sample groups. All accessible peaks from all samples were merged into a union peak list, and all dispersions were estimated. Differentially accessible peaks were selected with the DESeq2 package using raw read counts of each sample in the union peak list using a log2 fold change of ≥1 and an FDR of <0.05. The read counts of the differentially accessible peaks in each sample were further normalized by z score transformation. Hierarchical clustering was used to cluster the peaks and samples. Correlation heatmap and PCA dot chart based on the affinity scores for ATAC-seq samples was also plotted using DiffBind package with the default settings.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the significance of differences between groups. All error bars were calculated in GraphPad Prism, and data were presented as the means ± SD. In all figure legends, n value represents the number of independent biological replicates.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Chen and their team at EHBIO Gene Technology (Beijing) for advice and assistance with bioinformatics analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by Projects of International Cooperation and Exchanges National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (no. 32061160364), NSFC (no. 81721003), and Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (no. 2016ZT06S029).

Author contributions: H.O. provided the idea, conceived this project, and contributed to the discussion and writing. Y.L. contributed to the discussion and revised the manuscript. H.H. designed and performed the experiments and data analysis and wrote the manuscript. J.L. performed the experiments and contributed to the experimental design. M.L. provided comments and contributed to the data analysis. S.W. and J.Z. performed cell culture. H.G., L.Z., Y.H., C.C., K.M., J.T., B.W., Y.Y., and L.W. helped the experiments.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The accession number for the publicly available RNA-seq data used in this paper is GEO: GSE97213.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S5

Table S1

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S2 to S5

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Li L., Wang Y., Torkelson J. L., Shankar G., Pattison J. M., Zhen H. H., Fang F., Duren Z., Xin J., Gaddam S., Melo S. P., Piekos S. N., Li J., Liaw E. J., Chen L., Li R., Wernig M., Wong W. H., Chang H. Y., Oro A. E., TFAP2C- and p63-dependent networks sequentially rearrange chromatin landscapes to drive human epidermal lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell 24, 271–284.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan X., Wang D., Burgmaier J. E., Teng Y., Romano R. A., Sinha S., Yi R., Single cell and open chromatin analysis reveals molecular origin of epidermal cells of the skin. Dev. Cell 47, 133 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenfelder S., Furlan-Magaril M., Mifsud B., Tavares-Cadete F., Sugar R., Javierre B. M., Nagano T., Katsman Y., Sakthidevi M., Wingett S. W., Dimitrova E., Dimond A., Edelman L. B., Elderkin S., Tabbada K., Darbo E., Andrews S., Herman B., Higgs A., LeProust E., Osborne C. S., Mitchell J. A., Luscombe N. M., Fraser P., The pluripotent regulatory circuitry connecting promoters to their long-range interacting elements. Genome Res. 25, 582–597 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin A. J., Barajas B. C., Furlan-Magaril M., Lopez-Pajares V., Mumbach M. R., Howard I., Kim D. S., Boxer L. D., Cairns J., Spivakov M., Wingett S. W., Shi M., Zhao Z., Greenleaf W. J., Kundaje A., Snyder M., Chang H. Y., Fraser P., Khavari P. A., Lineage-specific dynamic and pre-established enhancer-promoter contacts cooperate in terminal differentiation. Nat. Genet. 49, 1522–1528 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freire-Pritchett P., Schoenfelder S., Varnai C., Wingett S. W., Cairns J., Collier A. J., Garcia-Vilchez R., Furlan-Magaril M., Osborne C. S., Fraser P., Rugg-Gunn P. J., Spivakov M., Global reorganisation of cis-regulatory units upon lineage commitment of human embryonic stem cells. eLife 6, e21926 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang N., Mendieta-Esteban J., Magli A., Lilja K. C., Perlingeiro R. C. R., Marti-Renom M. A., Tsirigos A., Dynlacht B. D., Muscle progenitor specification and myogenic differentiation are associated with changes in chromatin topology. Nat. Commun. 11, 6222 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siersbaek R., Madsen J. G. S., Javierre B. M., Nielsen R., Bagge E. K., Cairns J., Wingett S. W., Traynor S., Spivakov M., Fraser P., Mandrup S., Dynamic rewiring of promoter-anchored chromatin loops during adipocyte differentiation. Mol. Cell 66, 420–435.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pombo A., Dillon N., Three-dimensional genome architecture: Players and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 245–257 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furlong E. E. M., Levine M., Developmental enhancers and chromosome topology. Science 361, 1341–1345 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker J., Marti-Renom M. A., Mirny L. A., Exploring the three-dimensional organization of genomes: Interpreting chromatin interaction data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 390–403 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shahbazi M. N., Scialdone A., Skorupska N., Weberling A., Recher G., Zhu M., Jedrusik A., Devito L. G., Noli L., Macaulay I. C., Buecker C., Khalaf Y., Ilic D., Voet T., Marioni J. C., Zernicka-Goetz M., Pluripotent state transitions coordinate morphogenesis in mouse and human embryos. Nature 552, 239–243 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng H., Xie P., Liu L., Kuang X., Wang Y., Qu L., Gong H., Jiang S., Li A., Ruan Z., Ding L., Yao Z., Chen C., Chen M., Daigle T. L., Dalley R., Ding Z., Duan Y., Feiner A., He P., Hill C., Hirokawa K. E., Hong G., Huang L., Kebede S., Kuo H. C., Larsen R., Lesnar P., Li L., Li Q., Li X., Li Y., Li Y., Liu A., Lu D., Mok S., Ng L., Nguyen T. N., Ouyang Q., Pan J., Shen E., Song Y., Sunkin S. M., Tasic B., Veldman M. B., Wakeman W., Wan W., Wang P., Wang Q., Wang T., Wang Y., Xiong F., Xiong W., Xu W., Ye M., Yin L., Yu Y., Yuan J., Yuan J., Yun Z., Zeng S., Zhang S., Zhao S., Zhao Z., Zhou Z., Huang Z. J., Esposito L., Hawrylycz M. J., Sorensen S. A., Yang X. W., Zheng Y., Gu Z., Xie W., Koch C., Luo Q., Harris J. A., Wang Y., Zeng H., Morphological diversity of single neurons in molecularly defined cell types. Nature 598, 174–181 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paluch E., Heisenberg C. P., Biology and physics of cell shape changes in development. Curr. Biology. 19, R790–R799 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heisenberg C. P., Bellaiche Y., Forces in tissue morphogenesis and patterning. Cell 153, 948–962 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munjal A., Philippe J. M., Munro E., Lecuit T., A self-organized biomechanical network drives shape changes during tissue morphogenesis. Nature 524, 351–355 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luxenburg C., Pasolli H. A., Williams S. E., Fuchs E., Developmental roles for Srf, cortical cytoskeleton and cell shape in epidermal spindle orientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 203–214 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler L. C., Blanchard G. B., Kabla A. J., Lawrence N. J., Welchman D. P., Mahadevan L., Adams R. J., Sanson B., Cell shape changes indicate a role for extrinsic tensile forces in Drosophila germ-band extension. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 859–864 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinsmore J. H., Solomon F., Inhibition of MAP2 expression affects both morphological and cell division phenotypes of neuronal differentiation. Cell 64, 817–826 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens D. W., Lane E. B., The quest for the function of simple epithelial keratins. Bioessays 25, 748–758 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koster M. I., Roop D. R., Mechanisms regulating epithelial stratification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 93–113 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green H., Easley K., Iuchi S., Marker succession during the development of keratinocytes from cultured human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15625–15630 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song M., Yang X., Ren X., Maliskova L., Li B., Jones I. R., Wang C., Jacob F., Wu K., Traglia M., Tam T. W., Jamieson K., Lu S. Y., Ming G. L., Li Y., Yao J., Weiss L. A., Dixon J. R., Judge L. M., Conklin B. R., Song H., Gan L., Shen Y., Mapping cis-regulatory chromatin contacts in neural cells links neuropsychiatric disorder risk variants to target genes. Nat. Genet. 51, 1252–1262 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolopoulou E., Hirst C. S., Galea G., Venturini C., Moulding D., Marshall A. R., Rolo A., De Castro S. C. P., Copp A. J., Greene N. D. E., Spinal neural tube closure depends on regulation of surface ectoderm identity and biomechanics by Grhl2. Nat. Commun. 10, 2487 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowak J. A., Polak L., Pasolli H. A., Fuchs E., Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 3, 33–43 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verzi M. P., Shin H., He H. H., Sulahian R., Meyer C. A., Montgomery R. K., Fleet J. C., Brown M., Liu X. S., Shivdasani R. A., Differentiation-specific histone modifications reveal dynamic chromatin interactions and partners for the intestinal transcription factor CDX2. Dev. Cell 19, 713–726 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadowaki M., Nakamura S., Machon O., Krauss S., Radice G. L., Takeichi M., N-cadherin mediates cortical organization in the mouse brain. Dev. Biol. 304, 22–33 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Depaepe V., Suarez-Gonzalez N., Dufour A., Passante L., Gorski J. A., Jones K. R., Ledent C., Vanderhaeghen P., Ephrin signalling controls brain size by regulating apoptosis of neural progenitors. Nature 435, 1244–1250 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Callaerts P., Halder G., Gehring W. J., PAX-6 in development and evolution. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 483–532 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecland N., Luders J., The dynamics of microtubule minus ends in the human mitotic spindle. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 770–778 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jo M., Kim T. H., Seol D. W., Esplen J. E., Dorko K., Billiar T. R., Strom S. C., Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat. Med. 6, 564–567 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakahira H., Enari M., Nagata S., Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature 391, 96–99 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs J., Atkins M., Davie K., Imrichova H., Romanelli L., Christiaens V., Hulselmans G., Potier D., Wouters J., Taskiran I. I., Paciello G., González-Blas C. B., Koldere D., Aibar S., Halder G., Aerts S., The transcription factor Grainy head primes epithelial enhancers for spatiotemporal activation by displacing nucleosomes. Nat. Genet. 50, 1011–1020 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pattison J. M., Melo S. P., Piekos S. N., Torkelson J. L., Bashkirova E., Mumbach M. R., Rajasingh C., Zhen H. H., Li L., Liaw E., Alber D., Rubin A. J., Shankar G., Bao X., Chang H. Y., Khavari P. A., Oro A. E., Retinoic acid and BMP4 cooperate with p63 to alter chromatin dynamics during surface epithelial commitment. Nat. Genet. 50, 1658–1665 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mole M. A., Galea G. L., Rolo A., Weberling A., Nychyk O., De Castro S. C., Savery D., Fassler R., Ybot-Gonzalez P., Greene N. D. E., Copp A. J., Integrin-mediated focal anchorage drives epithelial zippering during mouse neural tube closure. Dev. Cell 52, 321–334.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Otterloo E., Milanda I., Pike H., Thompson J. A., Li H., Jones K. L., Williams T., AP-2α and AP-2β cooperatively function in the craniofacial surface ectoderm to regulate chromatin and gene expression dynamics during facial development. eLife 11, e70511 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochiai H., Suga H., Yamada T., Sakakibara M., Kasai T., Ozone C., Ogawa K., Goto M., Banno R., Tsunekawa S., Sugimura Y., Arima H., Oiso Y., BMP4 and FGF strongly induce differentiation of mouse ES cells into oral ectoderm. Stem Cell Res. 15, 290–298 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li E., Materna S. C., Davidson E. H., Direct and indirect control of oral ectoderm regulatory gene expression by Nodal signaling in the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 369, 377–385 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi Y., Hayashi R., Shibata S., Quantock A. J., Nishida K., Ocular surface ectoderm instigated by WNT inhibition and BMP4. Stem Cell Res. 46, 101868 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashi R., Ishikawa Y., Sasamoto Y., Katori R., Nomura N., Ichikawa T., Araki S., Soma T., Kawasaki S., Sekiguchi K., Quantock A. J., Tsujikawa M., Nishida K., Co-ordinated ocular development from human iPS cells and recovery of corneal function. Nature 531, 376–380 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wingett S. W., Andrews S., FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res 7, 1338 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B., Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T. R., STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li B., Dewey C. N., RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buenrostro J. D., Giresi P. G., Zaba L. C., Chang H. Y., Greenleaf W. J., Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H., Durbin R., Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C. A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D. S., Bernstein B. E., Nusbaum C., Myers R. M., Brown M., Li W., Liu X. S., Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramirez F., Ryan D. P., Gruning B., Bhardwaj V., Kilpert F., Richter A. S., Heyne S., Dundar F., Manke T., deepTools2: A next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y. C., Laslo P., Cheng J. X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C. K., Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M., BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagano T., Varnai C., Schoenfelder S., Javierre B. M., Wingett S. W., Fraser P., Comparison of Hi-C results using in-solution versus in-nucleus ligation. Genome Biol. 16, 175 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mifsud B., Tavares-Cadete F., Young A. N., Sugar R., Schoenfelder S., Ferreira L., Wingett S. W., Andrews S., Grey W., Ewels P. A., Herman B., Happe S., Higgs A., LeProust E., Follows G. A., Fraser P., Luscombe N. M., Osborne C. S., Mapping long-range promoter contacts in human cells with high-resolution capture Hi-C. Nat. Genet. 47, 598–a606 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wingett S., Ewels P., Furlan-Magaril M., Nagano T., Schoenfelder S., Fraser P., Andrews S., HiCUP: Pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Research 4, 1310 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cairns J., Freire-Pritchett P., Wingett S. W., Varnai C., Dimond A., Plagnol V., Zerbino D., Schoenfelder S., Javierre B. M., Osborne C., Fraser P., Spivakov M., CHiCAGO: Robust detection of DNA looping interactions in capture Hi-C data. Genome Biol. 17, 127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou X., Li D., Zhang B., Lowdon R. F., Rockweiler N. B., Sears R. L., Madden P. A., Smirnov I., Costello J. F., Wang T., Epigenomic annotation of genetic variants using the roadmap epigenome browser. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 345–346 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ernst J., Kellis M., ChromHMM: Automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods 9, 215–216 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A. H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S. K., Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S. L., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., Mesirov J. P., Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu D. Y., Bittencourt D., Stallcup M. R., Siegmund K. D., Identifying differential transcription factor binding in ChIP-seq. Front. Genet. 6, 169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S5

Table S1

References

Tables S2 to S5