Abstract

Aims

Cryoballoon (CB) based pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is a widely used technique for treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF); however the ideal energy dosing has not yet been standardized. This was a single-centre randomized clinical trial aiming at assessing the safety, acute efficacy, and clinical outcome of an individualized vs. a fixed CB ablation protocol using the fourth-generation CB (CB4) guided by pulmonary vein (PV) potential recordings and CB temperature.

Methods and results

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to two different dosing protocols: INDI-FREEZE group (individualized protocol): freeze-cycle duration of time to effect plus 90 s or interruption of the freeze-cycle and repositioning CB if a CB temperature of −30°C was not within 40 s. Control group (fixed protocol): freeze-cycle duration of 180 s. No-bonus freeze-cycle was applied in either patient group. The primary endpoint was freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia at 12 months. Secondary end points included procedural parameters and complications. A total of 100 patients with paroxysmal AF were prospectively enrolled. No difference was seen in the primary endpoint [INDI-FREEZE group: 38/47 (81%) vs. control group: 40/47, (85%), P = 0.583]. The total freezing time was significantly shorter in the INDI-FREEZE group (157 ± 56 s vs. 212 ± 83 s, P < 0.001), while procedure duration (57.9 ± 17.9 min vs. 63.2 ± 20.2 min, P = 0.172) was similar. No differences were seen in the minimum CB and oesophageal temperatures as well as in periprocedural complications.

Conclusion

Compared to the fixed protocol, the individualized approach provides a similar safety profile and clinical outcome, while reducing the total freezing time.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Ablation, Cryoballoon, Fourth generation cryoballoon, Time to effect, Total freezing time, Pulmonary vein isolation, Individualized approach, Randomized study

What’s new?

The ideal energy dosing for cryoballoon (CB)-based pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) has not yet been standardized. The INDI-FREEZE trial was a prospective randomized trial aiming at assessing the acute efficacy and clinical outcome of an individualized vs. a fixed ablation protocol using the fourth-generation CB guided by PV potential recordings and CB temperature.

The total freezing time was significantly shorter in the INDI-FREEZE group, while procedure duration was similar. No differences were seen in periprocedural complications.

Our findings guide further studies to implement individualized approaches and protocols to patients treatment to further improve outcomes and reduced periprocedural complications.

Introduction

The non-inferiority of cryoballoon (CB) as compared to radiofrequency (RF)-based pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) with regard to efficacy and safety for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) has been demonstrated in the FIRE AND ICE trial.1 As a consequence, CB PVI has become a standard choice for the rhythm control strategy in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), according to the latest guidelines. Various CB ablation strategies applied a fixed freeze-cycle duration of 180–240 s oftentimes followed by a ‘bonus’ freeze-cycle.2 However, ablation protocols have been modified aiming at shorter and fewer CB-applications, which demonstrated similar clinical outcomes.3,4 In order to obtain an improved individualized approach, a new parameter defining the time to pulmonary vein (PV) isolation—i.e. the ‘time to effect’ (TTE)—was introduced. It has been shown that TTE is an independent predictor of recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia. As a consequence, recent strategies have implemented the individual TTE into CB protocols. Individualized ablation strategies may be equally effective regarding acute and long-term clinical success with a potentially better safety profile. In this context, a TTE + 120 s protocol has been introduced and was found to be similar concerning acute efficacy with an even better safety profile.5 Previous observations showed that a TTE of <75 s and a temperature of −30°C after 30 s seemed to improve the durability of PVI.6,7 Taking this information into account, we designed an individualized dosing protocol implementing the TTE and the CB temperature. The fourth-generation CB (CB4, Artic Front Advance Pro, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA), with its tip shortened by 40% vs. the second-generation of CB (CB2), aims at an improved recording of PV signals.8 Recent analyses have demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of TTE recordings with the CB4 than the CB2.8 Initial clinical experience combining the TTE-based approach with the CB4 was associated with encouraging results.9 Even so, the optimal CB energy dosing has not been established yet. We therefore sought to assess, in patisents with symptomatic PAF, the efficacy, safety, and clinical outcome of PVI with the CB4 using either an individualized ablation protocol with an individualized, reduced freezing time as well as CB temperature assessments or a standard approach with a fixed freeze duration ablation protocol.

Methods

Patient characteristics

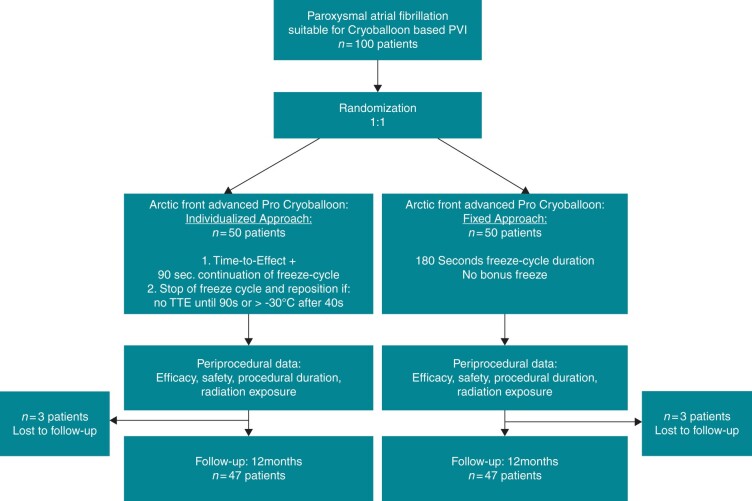

A total of 100 patients with symptomatic PAF were prospectively enrolled. The patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion into two groups: the individualized-protocol (INDI-FREEZE) group receiving an individualized ablation protocol and the control group receiving a fixed-duration ablation protocol (Figure 1). Exclusion criteria were prior left atrial (LA) ablation attempts, a LA diameter >60 mm, severe valvular heart disease, or contraindications to post-interventional oral anticoagulation. Prior to PVI, a transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed to rule out intracardiac thrombi and to assess the LA diameter. No further pre-procedural imaging was performed. In patients on vitamin K antagonists the procedure was performed under therapeutic INR values of 2–3. In patients on new oral anticoagulants, the morning dose on the day of the procedure was omitted. All patients gave written informed consent and all patient information was anonymized. The INDI-FREEZE trial was approved by the local ethics committee (Lübeck ablation registry ethical review board number: WF‐028/15) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT03747263).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart showing the 1:1 randomization in the INDI-FREEZE trial. PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; TTE, time to effect.

Cryoballoon ablation

All procedures were performed by operators highly experienced in CB procedures. The detailed intraprocedural management has been described in previous studies from our centre.9 In brief, the procedure was performed under deep sedation using boluses of midazolam, fentanyl, and a continuous infusion of propofol. Two right femoral vein punctures were performed and two 8F short sheaths were inserted. Prior to transseptal puncture (TSP), one diagnostic catheter was introduced via the right femoral vein and positioned within the coronary sinus. A single TSP was performed under fluoroscopic guidance using a modified Brockenbrough technique and an 8.5F transseptal sheath. Afterwards the LA access was confirmed by contrast medium injection. Selective PV angiography was then performed to identify the pulmonary vein (PV) ostia utilizing a 7F multipurpose catheter or directly via the transseptal sheath. The transseptal sheath was exchanged over a guidewire for the 15F Flexcath Advance sheath. The sheath was continuously flushed with heparinized saline (20 mL/h). After TSP heparin boluses were administered targeting an activated clotting time of >300 s. During energy delivery, a continuous oesophageal temperature monitoring was performed using an oesophageal temperature probe (Sensitherm; St Jude Medical, Inc. or CIRCA S‐CATH™) positioned according to the individual CB location. The intraluminal oesophageal temperature cut-off was set at 15°C.10 During energy delivery along the septal PVs, continuous phrenic nerve (PN) pacing with maximum output and pulse width (12 mA, 2.9 ms) at a cycle length of 1000 ms was performed, using the diagnostic catheter positioned in the superior vena cava. Capture of PN was monitored by intermittent fluoroscopy and by tactile feedback of diaphragmatic contractions. In addition, the continuous motor action potential (CMAP) was monitored. Weakening or loss of diaphragmatic movement, as well as a reduction of CMAP amplitude of ≥30% led to an immediate stop of energy delivery. In the case of PN palsy (PNP), no additional freeze cycle was applied along with the septal PVs.

The CB4 was advanced into the LA via the 15 Fr steerable sheath and a spiral mapping catheter (20 mm diameter; Achieve, Medtronic) was advanced into the target PV to record electrical activity. The spiral catheter was placed in a proximal position to facilitate real-time TTE recording. The occlusion of the PV ostium was verified by contrast dye injections. A ‘pop‐out’ phenomenon was defined as a balloon dislodgement from the PV ostium after initializing the freezing process. This was evaluated by a second injection of contrast medium and fluoroscopy 5–10 s after initializing the freezing process. If stable occlusion was verified, the freeze cycle was continued; if the occlusion was not perfect the balloon was slightly repositioned and a third contrast dye injection was utilized to verify occlusion or the freeze cycle was stopped and a further attempt was made. The minimum CB cut‐off temperature was set at −60°C. The PVs were treated in a clockwise sequence (LSPV, LIPV, RIPV, RSPV). A gentle pull‐down manoeuvre was performed for the LIPV and RIPV after 70 s of freezing time. In patients in AF at the time of the procedure, electrical cardioversion was performed after the final freeze cycle and PVI was reconfirmed for each PV in sinus rhythm.

Energy dosing

INDI-FREEZE group

In the INDI-FREEZE group, the PV potentials were continuously registered via the intraluminal spiral mapping catheter concomitant with energy delivery until PVI, and then the freeze-cycle was prolonged for an additional 90 s. If no PVI was achieved after 90 s or a temperature of <−30°C was not reached after 40 s, freezing was stopped and the CB was repositioned to possibly achieve a better position. No-bonus freeze-cycle was applied. If no real-time PV signal recordings were obtained, a standard freeze-cycle of 180 s was applied.

Control group

In the control group, a fixed protocol was utilized. The PV signals were recorded but were not used to individualize the ablation time. For each PV, a fixed freeze-cycle of 180 s was applied. If PVI was not achieved with the first freeze-cycle, another 180 s freeze-cycle was applied until documented PVI. No-bonus freeze-cycle was applied after confirmed PVI.

Post-procedural proceeding and follow-up

A figure-of-eight suture and a pressure bandage were used to prevent femoral bleeding. The pressure bandage was removed after 4 h and the suture was removed on the next day. Following ablation, all patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography immediately, after 2 h, and on Day 1 to rule out a pericardial effusion. In patients on vitamin K antagonists with an INR <2.0, low molecular weight heparin was administered until a therapeutic INR of 2–3 was achieved. Novel oral anticoagulants were reinitiated 6 h post-ablation. Anticoagulation was continued for at least 3 months and maintained thereafter based on the individual CHA2DS2‐VASc score. Previously ineffective antiarrhythmic drugs or a new antiarrhythmic drug were prescribed and continued for 3 months post ablation. All patients were treated with proton‐pump inhibitors for 6 weeks. Following a 3 months blanking period, patients completed outpatient clinic visits, including ECG and 72 h-Holter ECG at 3, 6, and 12 months. In addition, regular telephone interviews were performed. Additional outpatient clinic visits were immediately initiated in cases of symptoms suggestive of arrhythmia recurrence.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint was defined as freedom from documented AF/atrial tachycardia (AT) recurrence 12 months after PVI, including a 90-day blanking period. Recurrence was defined as any ECG-documented atrial tachyarrhythmia lasting for at least 30 s, including AF as well as AT and atrial flutter.

Secondary endpoints

The secondary endpoints were: acute procedural success defined as the ability to confirm electrical isolation with a circular mapping catheter in sinus rhythm, procedural parameters (procedure time, fluoroscopy time), number and duration of freeze cycles, as well as periprocedural complications [cardiac tamponade, phrenic nerve injury, stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA), severe bleeding, atrioesophageal fistula, and death].

Statistical analysis

The sample size was based on previous findings (ICE-T trial)6 and was calculated as follows: With 50 subjects in each group, the lower limit of the observed one-sided 95.0% confidence interval will be expected to exceed −12% with 80% power when freedom from the primary endpoint is expected at 82% in the control group and at 88% in the INDI-FREEZE group; results are based on 100 000 simulations using the Newcombe-Wilson score method to construct the confidence interval. Continuous variables are presented as means and SDs; they were compared using Student's t-test. Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies; they were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test (in case of small expected cell frequencies). All P‐values are two‐sided and a P‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed with the SAS statistical analysis software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 100 consecutive patients were randomized to either the INDI-FREEZE group (n = 50) or the control group (n = 50) from December 2018 to May 2020. The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were seen between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| INDI-FREEZE | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 50 | 50 | |

| Age (years) | 67 ± 12 | 68 ± 10 | 0.974 |

| Body mass index | 26.6 ± 4 | 27.7 ± 5 | 0.531 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 0.999 |

| LA volume index (mL/m²) | 33.0 ± 8.8 | 33.2 ± 9.3 | 0.932 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 25 (50) | 23 (44) | 0.689 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 50 (100) | 50 (100) | 0.999 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 0.999 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 32 (64) | 34 (68) | 0.673 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2, n (%) | 1 (2) | 5 (10) | 0.921 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 12 (24) | 7 (14) | 0.892 |

| Prior stroke/TIA, n (%) | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 0.461 |

Values are counts (n), n (%), or mean ± standard deviation.

AF, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrium.

Acute ablation results

In the INDI-FREEZE group, 99.5% of the PVs were successfully isolated (n = 199/200 PVs), while in the control group all PVs were isolated (n = 198/198 PVs). There was no significant difference between the groups regarding the minimum CB temperature (−46.1 ± 6.3°C vs. –45.3 ± 6.9°C, P = 0.941) or the minimum oesophageal temperature (32.5 ± 5.2°C vs. 33.1 ± 3.8°C, P = 0.954). The incidence of TTE recordings was significantly higher in the INDI-FREEZE group (138 (69%) vs. 99 (50%), p < 0.001), and a trend toward shorter TTE was also observed in these patients as compared to the control group (43 ± 23 s vs. 50 ± 31 s, P = 0.073). No difference was noted in the total procedure and fluoroscopy times, while the total freezing time was significantly shorter in the INDI-FREEZE group (157 ± 56 s vs. 212 ± 83 s, p < 0.001). The total amount of contrast medium was also smaller in the INDI-FREEZE group (63 ± 17ml vs. 74 ± 23ml, P = 0.006). The results were similar regarding the total number of isolated PVs and total CB cycles per PV. Details of the acute ablation characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Procedural details

| INDI-FREEZE | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PVs, n | 200 | 198 | |

| Total number of isolated PVs | 199 (99.5) | 198 (100) | 0.999 |

| Total CB cycles | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.867 |

| Single-shot isolations | 185 (93) | 162 (82) | <0.01 |

| Minimum CB temperature (°C) | −46.1 ± 6.3 | −45.3 ± 6.9 | 0.941 |

| Minimum oesophageal temperature (°C) | 32.5 ± 5.2 | 33.1 ± 3.8 | 0.954 |

| Time to PVI (s) | 43 ± 23 | 50 ± 31 | 0.073 |

| TTE recordings | 138 (69) | 99 (50) | <0.001 |

| Duration of total freezing time/PV (s) | 157 ± 56 | 212 ± 83 | <0.001 |

| Duration of total freezing time/patient (s) | 619 ± 127 | 842 ± 162 | <0.001 |

| Total procedure time (min) | 57.9 ± 17.9 | 63.2 ± 20.2 | 0.172 |

| Total fluoroscopy time (min) | 15.0 ± 10.3 | 14.2 ± 7.5 | 0.698 |

| Total amount of contrast medium (mL) | 63 ± 17 | 74 ± 23 | 0.006 |

| INDI-FREEZE protocol only | |||

| Interruption of freezing cycle (TTE not <90 s), n (%) | 2 (1) | ||

| Interruption of freezing cycle (temp not −30° after 40 s), n (%) | 8 (4) | ||

| Major complications | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.307 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.999 |

| Phrenic nerve injury | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0.558 |

| Stroke/TIA | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.879 |

| Severe bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.999 |

| Atrioesophageal fistula | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.999 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.999 |

Values are counts (n), n (%), or mean ± standard deviation.

CB, cryoballoon; PV(s), pulmonary vein(s); PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; temp, temperature; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; TTE, time to effect.

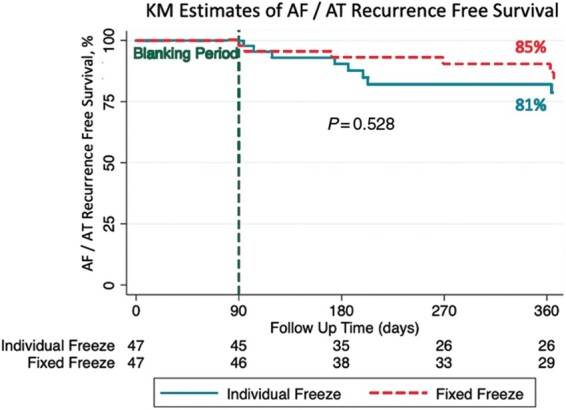

Primary endpoint

In each group, 3 patients were lost to follow-up. Single procedure success rates after 12 months (including a 90-day blanking period) were similar in both groups (INDI-FREEZE group: 38/47, 81%; control group: 40/47, 85%) P = 0.583 (Figure 2). At the 12-month follow-up visit, 11 patients were on antiarrhythmic drugs (INDI-FREEZE group: n = 7; control group: n = 4; P = 0.336). A total of 4 patients per group received a repeat procedure. Of 16 PVs treated by the INDI-FREEZE protocol 6 PVs (RSPV: 1, RIPV: 3, LSPV: 1, LIPV: 1; (37.5%) showed reconduction, while 3/16 PVs (RSPV: 2, LSPV: 1) treated by the fixed protocol showed recondition (18.8%, P = 0.238).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier arrhythmia-free survival curves showing no significant difference in clinical outcome during the 12 months follow-up. A total of three patients were lost to follow-up in each group.

Complications

No death, cardiac tamponade, severe bleeding, or atrioesophageal fistula occurred during the study. A total of four major complications were noted, 3 (6%) in the INDI-FREEZE group and 1 (2%) in the control group (P = 0.307). One patient suffered a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) in the INDI-FREEZE group. The patient developed systems of apraxia and sensibility disorders of his face. An intracerebral CT did not detect any intracranial bleeding. Resitutio ad integrum of the symptoms were found within less than 24 h. The mechanism of the TIA remains unclear. Phrenic nerve injury was the most frequent major complication, with 2 (4%) cases in the individualized TTE group and one (2%) case in the fixed duration group (P = 0.558). All PNPs recovered within 6 months of follow-up. Details of major periprocedural complications are depicted given in Table 2.

Discussion

The INDI-FREEZE trial sought to compare the procedural efficacy, ablation characteristics, and clinical outcome of an individualized vs. a fixed ablation protocol in patients with PAF utilizing the CB4. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial to compare two CB dosing protocols in CB4-based PVI. The major findings of this study are:

No significant differences were observed in the 12-months arrhythmia-free survival.

The total freezing time was significantly shorter in the INDI-FREEZE group.

There was no difference regarding the total fluoroscopy time and total procedural time.

The rate of major peri- and post-procedural complications was similar.

Since the FIRE AND ICE trial was published in 2016, CB-based PVI has become the cornerstone of catheter-based treatment of AF patients.1 Due to the shorter procedural time and shorter learning curve compared with radiofrequency-based PVI, this single-shot technique might become the new standard approach in selected patients. Even so, energy dosing protocols are not yet standardized. Recently, it has been shown that an individualized approach using TTE is safe and efficient, aiming for a shorter procedural time and a reduction in energy transfer.3,6 The concept of empiric bonus freeze-cycle has been abandoned since clinical trials demonstrated the non-inferiority of single-shot PVI in terms of procedural efficacy and clinical outcome.4 Previous studies showed that a TTE of <75 s and a steep temperature drop of −30°C after 30 s seems to improve the durability of PVI.6,7 To take account for these findings, the individualized INDI-FREEZE protocol was designed implementing (i) a shortened TTE-based freeze-cycle of TTE + 90s; (ii) a steep temperature drop of at least −30°C after 40 s; and (iii): no-bonus freeze-cycle.

Cryoballoon ablation efficacy

Recent studies focusing on the CB4 showed a high rate of TTE recordings (47–85%), high incidence of single-shot PVI (82–85%), and excellent clinical outcome with different ablation protocols, including fixed and individualized approaches.4,6,11,12 As discussed above, a high incidence of real-time PV potential recordings is an essential condition for the individualized TTE-based PVI. In our analysis, live PV potentials were recorded in 69% of PVs in the INDI-FREEZE group. This finding might be explained by the study protocol for this group. As expected, the total freezing time was significantly shorter for the personalized approach, but with no significant difference in the total procedure and total fluoroscopy time. The total amount of contrast medium was also lower in the individualized group. No difference was seen in the total number of freezing cycles per PV and total number of isolated PVs which confirms the non-inferiority of the individualized protocol in terms of acute efficacy. With these findings, it appears advisable for clinicians to implement TTE and CB temperature drop into individualized energy dosing protocols. Due to the fact that shorter freezing times did not lead to worse outcomes our data might influence other groups to further evaluate the optimal energy dosing protocol for CB-based PVI.

Safety profile

Characteristic complications of CB‐based PVI such as PNP or a significant drop in intraluminal oesophageal temperatures potentially resulting in oesophageal thermal injury typically occur at later stages of the freeze cycles. The ‘time to luminal oesophageal temperature 15°C drop’,13 and the ‘time to PN weakening’ are generally at later stages during the freeze cycle.14 Even if the total freezing time was significantly shorter in the INDI-FREEZE group, no difference was seen regarding the rate of major complications (P = 0.307) or minimal oesophageal temperature (P = 0.954), confirming the safety profile of the study protocol. These findings are in line with other reports on the reduced freezing time protocols.8,9,15,16

Clinical outcome

There was no significant difference between the groups regarding arrhythmia-free survival for the follow-up period of 12 months. With a 12-month clinical success rate of 81% (INDI-FREEZE) and 85% (control) our findings are in line with other recent studies focusing on different CB dosing protocols in PAF patients.6 The single-centre randomized ICE-T trial evaluated an individualized ablation protocol based on the TTE. If a TTE of >75 s was detected a bonus freeze-cycle was applied in the ICE-T group while in the control group a bonus freeze-cycle was applied in every PV. For this approach, similar 12-month clinical success rates of 88% (ICE-T) and 82% (control) were found.6 However, many previous studies suggested omitting a bonus freeze-cycle which was shown to achieve equal efficacy with an improved safety profile.2,4,17–20

Limitations

This is a single-centre randomized clinical trial with a limited number of patients. The power calculation was based on the data of a pilot trial (ICE-T).6 Therefore one important limitation of the current trial is the power to detect potentially significant differences in the primary outcome. Thus, confirmation in a larger patient cohort from multiple centres is needed. Due to the relatively low incidence of periprocedural complications in both groups, a larger cohort might establish whether the reduced energy delivery in the shortened ablation protocol provides a better safety profile. The present trial cannot establish if an even shorter freezing duration would still be efficient for durable PVI. For this trial, there was no blinding and no corelab or events committee. The ECGs were evaluated by experienced study nurses who were not involved in any other part of the research project. This fact is a further limitation of the trial. Although a total of six patients were lost to follow-up (three per group) the monitoring adherence of the remaining 96 patients was 100%. The monitoring was limited to 72-h Holter ECGs at 3, 6, and 12 months. Due to this intermittent monitoring, a risk of error for the primary endpoint could not be excluded. Additional this limitation might overestimate the overall success rate and closer follow-up (e.g. via implantable loop recorders) may have detected a higher of recurrences.

Conclusion

The individualized ablation protocol showed equal findings in terms of safety, acute efficacy, and clinical outcome, while providing a shorter total freezing duration compared to a fixed protocol. It appears reasonable to implement TTE and CB temperature drop into individualized energy dosing protocols.

Conflict of interest: C.H.H. received travel grants and research grants from Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Abbott and Cardiofocus and speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster and Cardiofocus. R.R.T. is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Biotronik and Biosense Webster and received speaker honoraria from Biosense Webster, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and Abbot Medical. KHK reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Biosense Webster outside the submitted work. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

Data cannot be shared for ethical/privacy reasons.

Contributor Information

Christian Hendrik Heeger, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany; German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Partner Site Hamburg/Kiel/Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany.

Sorin Stefan Popescu, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany; Carol Davila, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Roza Saraei, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Bettina Kirstein, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Sascha Hatahet, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Omar Samara, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Anna Traub, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Marcel Fehe, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Gabriele D’Ambrosio, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Ahmad Keelani, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Michael Schlüter, LANS Cardio, Stephansplatz 5, 20354 Hamburg, Germany.

Charlotte Eitel, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Julia Vogler, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Karl Heinz Kuck, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany; LANS Cardio, Stephansplatz 5, 20354 Hamburg, Germany.

Roland Richard Tilz, University Heart Center Lübeck, Division of Electrophysiology, Medical Clinic II (Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany; German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Partner Site Hamburg/Kiel/Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany.

References

- 1. Kuck KH, Brugada J, Furnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KRet al. . Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wissner E, Heeger CH, Grahn H, Reissmann B, Wohlmuth P, Lemes Cet al. . One-year clinical success of a “no-bonus” freeze protocol using the second-generation 28 mm cryoballoon for pulmonary vein isolation. Europace 2015;17:1236–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen S, Schmidt B, Bordignon S, Perrotta L, Bologna F, Chun KRJ.. Impact of cryoballoon freeze duration on long-term durability of pulmonary vein isolation: ICE re-map study. Jacc Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heeger CH, Wissner E, Wohlmuth P, Mathew S, Hayashi K, Sohns Cet al. . Bonus-freeze: benefit or risk? Two-year outcome and procedural comparison of a “bonus-freeze” and “no bonus-freeze” protocol using the second-generation cryoballoon for pulmonary vein isolation. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:774–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heeger C-H, Wissner E, Mathew S, Hayashi K, Sohns C, Reißmann Bet al. . Short tip-big difference? First-in-man experience and procedural efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation using the third-generation cryoballoon. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chun KR, Stich M, Furnkranz A, Bordignon S, Perrotta L, Dugo Det al. . Individualized cryoballoon energy pulmonary vein isolation guided by real-time pulmonary vein recordings, the randomized ICE-T trial. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Su W, Kowal R, Kowalski M, Metzner A, Svinarich JT, Wheelan Ket al. . Best practice guide for cryoballoon ablation in atrial fibrillation: the compilation experience of more than 3000 procedures. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:1658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Straube F, Dorwarth U, Pongratz J, Bruck B, Wankerl M, Hartl Set al. . The fourth cryoballoon generation with a shorter tip to facilitate real-time pulmonary vein potential recording: feasibility and safety results. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heeger C, Bohnen J, Popescu S, Meyer‐Saraei R, Fink T, Sciacca Vet al. . Experience and procedural efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation using the fourth and second generation cryoballoon: the shorter, the better? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021;32:1553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Metzner A, Burchard A, Wohlmuth P, Rausch P, Bardyszewski A, Gienapp Cet al. . Increased incidence of esophageal thermal lesions using the second-generation 28-mm cryoballoon. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:769–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reissmann B, Wissner E, Deiss S, Heeger C, Schlueter M, Wohlmuth Pet al. . First insights into cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation taking the individual time-to-isolation into account. Europace 2017;19:1676–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rottner L, Fink T, Heeger CH, Schluter M, Goldmann B, Lemes Cet al. . Is less more? Impact of different ablation protocols on periprocedural complications in second-generation cryoballoon based pulmonary vein isolation. Europace 2018;20:1459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miyazaki S, Kajiyama T, Watanabe T, Hada M, Yamao K, Kusa Set al. . Characteristics of phrenic nerve injury during pulmonary vein isolation using a 28-mm second-generation cryoballoon and short freeze strategy. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Furnkranz A, Bordignon S, Schmidt B, Perrotta L, Dugo D, Lazzari MDet al. . Incidence and characteristics of phrenic nerve palsy following pulmonary vein isolation with the second-generation as compared with the first-generation cryoballoon in 360 consecutive patients. Europace 2015;17:574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mathew S, Rottner L, Warneke L, Maurer T, Lemes C, Hashiguchi Net al. . Initial experience and procedural efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation using the fourth-generation cryoballoon - a step forward? Acta Cardiol 2020;75:754–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rottner L, Mathew S, Reissmann B, Warneke L, Martin I, Lemes Cet al. . Feasibility, safety, and acute efficacy of the fourth‐generation cryoballoon for ablation of atrial fibrillation: another step forward? Clin Cardiol 2020;43:394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Straube F, Dorwarth U, Hartl S, Bunz B, Wankerl M, Ebersberger Uet al. . Outcome of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation with the cryoballoon using two different application times: the 4- versus 3-min protocol. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2016;45:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heeger CH, Rexha E, Maack S, Rottner L, Fink T, Mathew Set al. . Reconduction after second-generation cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation- impact of different ablation strategies. Circ J 2020;84:902–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tebbenjohanns J, Hofer C, Bergmann L, Dedroogh M, Gaudin D, von WAet al. . Shortening of freezing cycles provides equal outcome to standard ablation procedure using second-generation 28 mm cryoballoon after 15-month follow-up. Europace 2016;18:206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ciconte G, Asmundis C, de Sieira J, Conte G, Giovanni GD, Mugnai Get al. . Single 3-minute freeze for second-generation cryoballoon ablation: one-year follow-up after pulmonary vein isolation. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be shared for ethical/privacy reasons.