Abstract

The plasmids in gut microbiomes have the potential to contribute to the microbiome community, as well as human health and physiology. Nevertheless, this niche remains poorly explored. In general, most microbiome studies focus on urban-industrialized groups, but here, we studied semi-isolated groups from South America and Africa, which would represent a link between ancestral and modern human groups. Based on open metagenomic data, we characterized the set of plasmids, including their genes and functions, from the gut microbiome of the Hadza, Matses, Tunapuco, and Yanomami, semi-isolated groups with a hunter, gather or subsistence lifestyle. Unique plasmid clusters and gene functions for each human group were identified. Moreover, a dozen plasmid clusters circulating in other niches worldwide are shared by these distinct groups. In addition, novel and unique plasmids harboring resistance (encompassing six antibiotic classes and multiple metals) and virulence (as type VI secretion systems) genes were identified. Functional analysis revealed pathways commonly associated with urban-industrialized groups, such as lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis that was characterized in the Hadza gut plasmids. These results demonstrate the richness of plasmids in semi-isolated human groups’ gut microbiome, which represents an important source of information with biotechnological/pharmaceutical potential, but also on the spread of resistance/virulence genes to semi-isolated groups.

Subject terms: DNA sequencing, Bioinformatics, Bacteria

Introduction

The human gut microbiome is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that performs several essential functions for human metabolism, nutrition, physiology, and immunity. Due to its high density and diversity of microorganisms, this environment is prone to constant genetic exchange between resident and transient bacteria1–4. Genetic transfers by plasmids in the gut have the potential to impact the ecology and evolution of the gut microbes. The acquisition of a plasmid and its cargo genes by gut bacteria or archaea may assist the microorganism's survival, fitness, and adaptation to the environment4–7. Some traits provided by plasmids in the gut have been associated with antibiotic (AR) and metal resistance (MR)7–10, salt tolerance11,12, and interbacterial competition13. Therefore, the set of plasmids in the human gut has the potential to modulate the gut microbiome community and introduce new traits, such as antibiotic resistance and virulence, to both resident and transient gut microbes4–14.

Many studies have assessed the microbial profile present in human gut microbiomes15–19. Although these studies have improved our knowledge on the subject, the set of plasmids in the gut microbiome is still poorly investigated despite its potential to modulate the microbiome physiology and, consequently, human health. Many human life aspects modulate the gut microbiome and its plasmids, including diet, lifestyle, therapy, consumption of pre- and probiotics, and diseases7,15–21. These aspects have been dramatically transformed during human history, which is evidenced by the current plethora of diets and lifestyles around the globe. The gut microbiome composition and functionality are products of a long coevolutionary host-microbe relationship, and the human gut plasmids also suggestively reflect this coevolution. As an example of the diet impacting mobile elements from the human gut, the seaweed in the Japanese daily diet was proposed to have transferred algal polysaccharide degradation genes to the Japanese microbiome20. The different diets of Fijians and Americans have been linked to the different glycoside hydrolase families encoded by mobile genes in the gut microbiome of these groups6. Moreover, the use of antimicrobials has been associated with the increase in the prevalence of mobile elements carrying functional resistance genes associated with synthetic antibiotics7–10,22–26.

Most of the microbiome studies have been focusing on urban-industrialized groups, and few have considered semi-isolated human groups15–19,27. However, the study of gut plasmids from semi-isolated groups has the potential to unravel genetic elements related to their unique lifestyle and environment. These groups retain valuable information about the microbiome before urbanization and industrialization impacted human diet and lifestyle, and also clues that can expand the field of prebiotics and probiotics for modern disorders prevention and treatment, as well as biomarkers that can form the basis for health and prognostic disease tests. So here, based on the gut microbiome survey from semi-isolated human groups, we investigated their plasmid content, including the set of accessory genes associated with these mobile elements that can modulate human health and physiology. We analyzed the set of plasmids and its accessory genes from the gut microbiome of four semi-isolated human groups: the Yanomami, the largest indigenous group from the Brazilian Amazon Forest19, the Matses, a remote hunter-gatherer group from the Peruvian Amazon Forest, the Tunapuco, a traditional agricultural community from the Peruvian Andean highlands16, and the Hadza, an indigenous ethnic group from northwestern Tanzania17. The geographical locations of these groups are presented in Fig. 1 and a summary of their diets and lifestyles is presented in Supplementary Note S1.

Figure 1.

Geographic locations of the four semi-isolated groups. Map generated in R, version 4.0.3. (https://www.R-project.org/) with the packages rnaturalearth, brazilmaps, sf and ggplot2.

Results

We identified a total of 290 putative plasmids in the gut microbiome of the Yanomami, Matses, Tunapuco, and Hadza. These putative plasmids were identified based on the nucleotide similarity with sequences of replication initiation protein (rep), mobilization protein (relaxase), mate-pair formation (MPF), and origin of transfer (oriT). The Yanomami was the group with significantly more plasmids identified (n = 184, FDR-corrected Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparisons: P < 0.05), followed by the Hadza (n = 52), the Matses (n = 36), and the Tunapuco (n = 18). The number of plasmids per metagenome varied from zero to 17 in the Yanomami, Matses, and Hadza, but in the Tunapuco it varied from zero to seven plasmids. However, one Yanomami metagenome stands out for harboring 90 plasmids (STable 1).

The plasmids were classified as conjugative, mobilizable, and non-mobilizable based on three plasmid markers: relaxase, MPF, and oriT. Thus, among the 290 plasmids identified in this study, 8 (~ 2.7%) were classified as conjugative, for harboring both relaxase and MPF; 89 (~ 30.6%) as mobilizable, for harboring relaxase and/or oriT without MPF; and the majority (n = 193, ~ 66.5%) as non-mobilizable, for not presenting relaxase and oriT. Considering the plasmid length, most of them (79.6%) is less than 10 Kb long, with 20% having between 10 and 90 Kb, and the longest plasmid has 115 Kb. These are the lengths of the contigs characterized as plasmids and they may not represent the length of the original plasmid. Information regarding each plasmid identified can be found in STable 1.

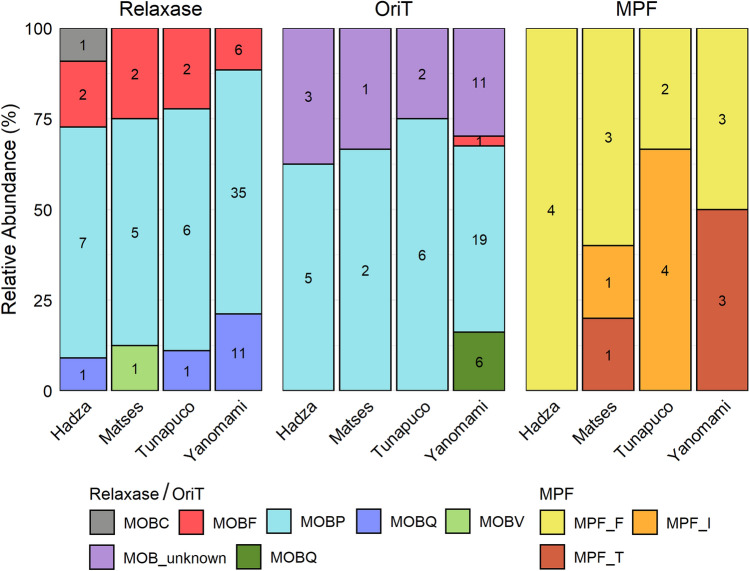

Moreover, mobilization (MOB) typing was used to classify the relaxase and oriT sequences of the conjugative and mobilizable plasmids into six MOB types. MOBP was the most prevalent type, followed by MOBQ, and MOBF (Fig. 2). Two other MOB families (MOBC and MOBV) were assigned to relaxases from the Hadza and Matses, respectively. MOBH was the only MOB family not identified. Besides, 16 oriT sequences did not match any of the six known MOB families and were classified as unknown. The MPF was also classified into classes and the most prevalent was MPFF, followed by MPFI and MPFT (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stacked bar chart representing the relative abundance (y-axis) of the MOB families and MPF types of the relaxase, oriT, and MPF identified in the gut plasmidomes of each group. Raw counts are also shown.

We explored the protein's functions encoded by the gut plasmids of the groups. The most abundant protein categories were Signaling/Cellular Processes (28–53%) and Genetic Information Processing (13–23%) (Stables 2, 3). The majority of the proteins associated with Signaling/Cellular Processes are part of Secretion (IV and VI) and Prokaryotic Defense Systems. The majority of proteins categorized as associated with Genetic Information Processing are related to Replication and Repair (Stables 2, 3). Some relevant gene functions identified in the gut plasmids differed by group. Considering the four human groups, functions related to lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis were exclusive to the Hadza, plant-pathogen interaction, immune system, and siderophore biosynthesis were exclusive to the Matses, flagellar assembly and drug and xenobiotics metabolism were exclusive to the Yanomami. Moreover, genes associated with Carbohydrate Metabolism and Other Amino Acids were only identified in the Matses and Yanomami. We also observed that the genes that generate energy metabolize different nutrients according to each group: Sulfur, Nitrogen and Methane in the Hadza, Matses and Yanomami, respectively.

Considering Prokaryotic Defense Systems, we performed focused analyses on identifying antimicrobial and metal resistance, and virulence, which in some cases, can directly impact the host's health. AR and MR genes and virulence factors (VFs) were found in 27 plasmids identified in 19/72 metagenomes (Stable 1). The Hadza was the group in which the gut set of plasmids harbored the highest number of AR, MR, or VFs (n = 25), followed by the Matses (n = 18), the Yanomami (n = 10), and the Tunapuco (n = 4). Considering all AR genes identified, they are associated with six antibiotic classes: aminoglycosides, β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, fosfomycin, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim. The most abundant AR genes found were aph (aminoglycoside resistance), tet (tetracycline resistance), and tem (beta-lactamase). The MR genes are associated with copper, iron, mercury, and multiple metals resistance. Concerning the VFs, one plasmid presents a heat-stable enterotoxin (astA), but the other VFs are mainly yersiniabactin, which besides being a VF, is also associated with iron resistance. The gene ybt, which is a siderophore yersiniabactin, was identified in a cluster of eight ybt genes in one plasmid recovered from one metagenome from the Matses (Stable 1).

Moreover, we also identified 119 transposase sequences in 49 plasmids. Therefore, some plasmids have more than one transposase. The vast majority have one to three transposases, but a plasmid recovered from Tunapuco had seven. The transposases were classified into families and the most prevalent was IS3 (n = 61).

Based on the clustering classification, the plasmids were split into three groups: 1, 2, and 3. Group 1 comprises plasmids that were assigned to plasmid clusters of the MOB-suite program database, therefore known plasmids. While plasmids that exceeded the distance threshold with all references in the database were classified in Groups 2 and 3, and therefore novel plasmids could be part of these groups. The former comprises plasmids shared among the metagenomes and were clustered, and the latter comprises unique plasmids. The plasmids of Group 1 (n = 96) were grouped into 63 clusters, Group 2 (n = 65) into 22 clusters, while the remaining 129 were singletons (Group 3).

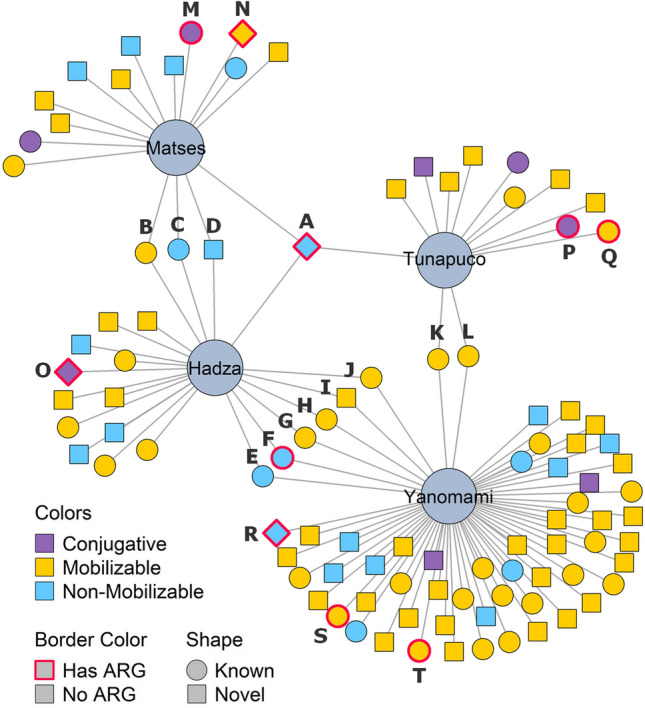

To infer the plasmids shared among the studied human groups, we generated a network based on the plasmid clusters characterized by MOB-suite (Fig. 2). The network revealed that 12/85 clusters (Group 1, n = 9; and Group 2, n = 3) are shared among the human groups, mostly between the Hadza and the Yanomami. Moreover, to expand our scenario, we also performed BLAST analysis on the plasmids shared among the groups. In this way, we found that the set of plasmids in the semi-isolated groups’ gut microbiome has a high similarity with plasmids spread worldwide in bacteria from humans, animals, environments, and foods (Table 1, Stable 4). Even Group 2 clusters, potentially comprising novel plasmids, presented similarities with known plasmids. However, the BLAST analysis of the plasmid cluster “R” returned no matches, indicating the presence of novel plasmids in this cluster.

Table1.

Mobility prediction and antibiotic resistance genes of the plasmid clusters A-T from the network.

| ID | Mobility | Groups | ARGs | Locality/Continent | Samples/Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Non-mobilizable | H/M/T | dfrf (Hadza) | Asia,Europe,N./S. America | Avian, Food, Human, Housefly, Cattle, Rat |

| B | Mobilizable | H/M | – | Eastern Asia, Europe, New Zealand, USA | Avian, Environment, Food, Human, Cattle |

| C | Non-mobilizable | H/M | – | China, Europe, Islas Malvinas, USA | Avian, Human, Housefly, Livestock, Rat |

| D | Non-mobilizable | H/M | – | Denmark, Islas Malvinas | Rat |

| E | Non-mobilizable | H/Y | – | Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, USA | Environment, Food, Human, Cattle, Rat, Sewage |

| F | Non-mobilizable | H/Y | tem, aph (H) tem (Y) | China,France | Environment, Food |

| G | Mobilizable | H/Y | – | Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, N. America | Avian, Environment, Human, Cattle |

| H | Mobilizable | H/Y | – | Africa, Australia, China, Europe, USA | Environment, Human, Swine |

| I | Mobilizable | H/Y | – | Europe, India, N./S. America | Food, Human |

| J | Mobilizable | H/Y | – | Australia, Asia, Europe, N/S.America | Avian, Canine, Environment, Human, Cattle, Sewage |

| K | Mobilizable | T/Y | – | Asia, Australia, Europe, USA | Avian, Environment, Human, Livestock, Mollusk |

| L | Mobilizable | T/Y | – | Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, N. America | Avian, Canine, Environment, Food, Human, Livestock |

| M | Conjugative | M | fosA | Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, USA | Avian, Canine, Human, Livestock, Panda |

| N | Mobilizable | M | ctx | Asia, Australia, Europe, N./S. America | Human |

| O | Conjugative | H | aph, tet | Asia, Europe, N. America | Avian, Canine, Human, Livestock |

| P | Conjugative | T | ctx | Asia, Europe, USA | Avian, Human |

| Q | Mobilizable | T | tetB | Asia, Australia, Europe, N. America | Human, Livestock |

| R | Non-mobilizable | Y | tetU | – | – |

| S | Mobilizable | Y | tem | Asia, Europe, Oceania, N./S. America | Avian, Canine, Human, Livestock |

| T | Mobilizable | Y | qnrB | Asia, Europe, N./S. America | Avian, Human |

The hosts and niches shown refer to the plasmids that had high similarity to this cluster by blast analysis. Groups: H—Hadza; M—Matses, T—Tunapuco, Y—Yanomami.

Surprisingly, the plasmids from the clusters “A”, “E”, and “C” (Fig. 3), previously characterized as non-mobilizable (Stable 1), were the clusters identified in a higher number of metagenomes. The cluster “A” was the most prevalent in the metagenomes analyzed, present in the Hadza (n = 3), Matses (n = 3), and Tunapuco (n = 1). The same rep and TolA sequences characterized the plasmids from cluster “A”, including the Hadza plasmids (n = 3), which also harbor a dfrf (dihydrofolate reductase) trimethoprim resistance gene. Besides that, this cluster was inferred by the MOB-suite as potentially hosted by bacteria of the genus Campylobacter. The clusters “E” and “C” harbor known plasmids, with no relevant functions so far assigned. The mobilizable cluster “F'' shared between the Hadza and Yanomami carries beta-lactamase resistance genes, besides some Hadza's plasmids also carry aph (aminoglycoside resistance). Conjugative plasmids carrying AR genes were identified in cluster “M” (fosA gene), cluster “O” (aph and tet genes), and cluster “P” (ctx gene) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Network based on the plasmid clusters (smaller-sized nodes) harbored and shared between the human groups (bigger-sized nodes). Non-mobilizable plasmids that were identified in only one metagenome were removed from this analysis. Identification of the plasmid clusters A-T is also shown. Network generated in R, version 4.0.3. (https://www.R-project.org/) with the packages igraph and ggplot2.

Besides the plasmids shared among the human groups, we also observed plasmids with the potential to be human group-specific as some from Group 2 clusters (n = 8) identified only in metagenomes from Hadza (n = 2) and Yanomami (n = 6). The Yanomami-specific clusters were classified as mobilizable (n = 4), but the others and Hadza's plasmids were non-mobilizable. These “human group-specific” plasmid clusters carry genes associated with Metabolism, mostly related to Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis, and also genes that encode Transport Proteins and Transposases.

Discussion

Diet and lifestyle have changed dramatically throughout human evolution, first with the introduction of farming (~ 10,000 years ago), and more recently, with the introduction of industrially processed foods, hygienic conditions, antimicrobials, pollution, and other factors27,28. These transformations in human lifestyle have been widely associated with the selection and modulation of the gut microbes and with a substantial loss of gut bacterial diversity15–19,27. However, this microbial profile restructuration not only involves the microbial taxa but, responding to selective pressures, also the mobilome4. Moreover, modern diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, and allergies, partially driven by the lifestyle, have been associated with the loss and variation of bacterial taxa and mobile elements diversity in the gut microbiome28,29.

In the present study, we analyzed the set of plasmids and their accessory genes from the gut microbiome of four semi-isolated human groups: the Yanomami from the Brazilian Amazon Forest19, the Matses from the Peruvian Amazon Forest, the Tunapuco from the Peruvian Andean highlands16, and the Hadza from northwestern Tanzania17. These datasets are some of the few high-quality shotgun metagenomes available from hunter-gatherers, human groups whose gut microbiomes represent a link between the ancestral and modern human groups. The bacterial composition and functionality of these four human groups have been previously analyzed, and although they have a similar contrasting composition compared to urban-industrialized groups, each of them has particular characteristics related to their different ecological niches, genetics, and diets15–19. The gut plasmids analysis showed a similar pattern, in which specific plasmid clusters and gene functions are unique for each human group, yet they also share significant parts of their set of plasmids. Moreover, a dozen of plasmid clusters are shared among these semi-isolated human groups living in distant and distinct geographical niches. In addition, some of these shared plasmid clusters have also been detected worldwide in humans, animals, environments, and foods. This could indicate that these plasmids are part of our ancestral microbiome and that they remain in the human population to this day, but could also reveal that the global inter-niche exchange of plasmids eventually carried out by modern practices could be reaching distinct semi-isolated human groups and their environments.

In general, plasmids can be classified by their relaxase and oriT, which comprise six MOB families, and MPF, which comprises four families23,30. Based on a database of plasmid markers, the gut plasmids of our study were mostly characterized by the families MOBP, MOBQ, and MOBF. The MOBP, a cluster of actively evolving relaxases, is the most prevalent family in plasmids databases, featuring a considerable proportion of short plasmids30,31. Indeed, most of the plasmids that we identified are short plasmids (< 10 Kb). Moreover, the MOBC and MOBV families, low prevalent families in plasmid databases, were identified in two novel plasmids of the Hadza and Matses. This highlights the yet underexplored scenario that modulates the plasmids and diversity in the gut microbiome30,31. Concerning the quantitative aspect, the Yanomami presented the largest set of plasmids in their gut and the Tunapuco the smallest, likely reflecting their remarkably different diet, lifestyle, and environment. Although both groups inhabit the Amazon Region, the Yanomami’s subsistence is based on gathering and hunting wild plants and animals in the Amazon Forest, the world's largest and most biodiverse tropical rainforest19,32,33. In contrast, Tunapuco’s subsistence is based on local agricultural produce and homegrown small animals located in the Peruvian Andean highlands, at an elevation between 2500 and 3100 m above sea level16,32,33.

The gut microbes usually process undigested carbohydrates, proteins, and fat, producing additional energy from the diet and also metabolites that can impact human physiology34. These metabolic functions, encoded by chromosomes and plasmids of the gut microbes, are selected/modulated according to the components of the human’s host diet7,20,34,35. In these groups, the food seasonality and their eventual nomadic behavior are selection pressures that can drive a variety of changes in the gut throughout the year, including in the set of plasmids. So, to rapidly adapt to the new/seasonal dietary components, specific enzymes must be selected and spread among the gut microbes34,35. This may explain why only the groups that inhabit the Amazonian Forest (Yanomami and Matses) have plasmid accessory genes associated with Carbohydrate and Other Amino Acids Metabolism. These groups live in a hotspot of diversity, therefore they are always coming into contact with various dietary components, which must be metabolized32–35. Moreover, their niches and consequently, the distinct selective pressures, contribute to the selection of plasmids’ content that participates in the metabolism of molecules from their diet. The functions identified as group-exclusive follow this context. For example, only in the Hadza set of plasmids was observed the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis pathway. This pathway is known for inducing strong inflammatory responses, but contrastingly, it also has anti-inflammatory actions when produced by certain gut bacteria, such as Bacteroidetes. Indeed, the Hadza harbor this phylum in their gut microbiomes15,17. LPS has been proposed to be used in the prevention or treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases that are induced by pro-inflammatory LPS36. The gut accessory genome, represented by the gut plasmids, constitutes an underexplored plethora of genes and functions and an important source of information with potential biotechnological or pharmaceutical value37,38.

The prevalent gene functions that were identified in the gut plasmids of all groups, such as Prokaryotic Defense Systems, Secretion Systems, and Replication and Repair, are associated with core plasmid genes39,40. However, the type VI Secretion Systems (T6SS) is not plasmid ubiquitous, moreover, it is associated with interbacterial competition, bacteria-host interactions, and virulence41–43. Therefore, if the T6SS is harbored by a commensal microbe, it can prevent the microbiome disassembly by an invading bacteria. In contrast, if T6SS is carried by an invading bacteria, the community assembly can be disestablished, resulting in dysbiosis41–43.

Interestingly, we observed a resistome in the gut plasmids of these human groups that have no or limited exposure to synthetic antibiotics, as well as reported in other isolated or semi-isolated groups/locations7,24,44. Most of these AR genes are associated with β-lactam and tetracycline resistance, which are commonly seen in soil and water environments45. In fact, Hadza and Yanomami gut plasmids harbor accessory genes with the function of biosynthesis of Penicillin and Cephalosporin. Therefore, the AR genes in these semi-isolated groups may have originated from an environment where antibiotic-producing microbes naturally occur, and also may have reached these groups via contact with antibiotic-exposed populations22,24,46,47. Since the Hadza and Matses presented the highest numbers of resistance and virulence genes in their gut plasmids, we speculate that these groups have been more impacted by urban-industrialized lifestyles, in a way that may be favoring the selection and expansion of these genes. A previous study with the Hadza, in fact, showed the existence of antibiotic resistance genes, in this population that has little to no antibiotic exposure, even though they have a lower amount of AR genes in comparison with an urban-industrialized population17.

In the same way, metal resistance genes present in the gut plasmids can reflect bacterial adaptations to environmental conditions. Indeed, the Yanomami niche is likely to be contaminated with cadmium due to the continuous discharge of batteries by them over decades19, however, the natural or artificial presence of metal in the other group’s environment is unknown. Moreover, MR genes can impact the community assembly of the gut microbiomes and consequently affect host health48. Concerning the virulome, there is no prevalence of bacterial virulence-associated factors in the gut plasmids, with the expectation of T6SS. In fact, these factors are not prevalent within environmental bacteria but occur more often in pathogens in clinical settings49. In addition, the plasmids recovered also harbor transposases, mainly the IS3 family, which is widely distributed and one of the largest and most abundant Insertion Sequence families among plasmids50.

The gut plasmids recovered and characterized here represent an achievement in the study of the gut microbiome of semi-isolated groups, providing a snapshot of the forces that modulate the gut microbiome given the unique as well as global scenarios to which these human groups are exposed. Although we have focused only on plasmids from the human gut, other mobile elements, such as bacteriophages, must also be relevant in this context. Beyond that, we are aware that our study has biases and limitations, for example, the plasmid identification that is based on the current plasmid markers in the databases. However, different studies have successfully carried out bioinformatic analysis of sequences and addressed them to plasmids, mainly when the plasmids were in vitro isolated from the strains51,52. The semi-isolated groups may harbor plasmid markers that have not yet been characterized and this may have resulted in the general lack of relaxase, MPF, and oriT sequences identified. As a result, most plasmids were classified as novel and non-mobilizable. Indeed, new MOB families have often been reported30,53–57. Besides, the complexity of metagenomic assembly tends to produce shorter contigs and may have hampered the identification of the whole genetic content of the plasmids58. In addition, the largest number of genes found in the plasmids have no known functionality. Indeed, the set of plasmids from the gut microbiome is a recognized source of novel genes and gene products, so the presence of unknown or novel elements is expected38. However, these results highlight the knowledge gap in this field and in databases, which is often attributed to the difficulties in studying plasmids from complex environments, such as microbiomes40,59.

Methods

For this study, we analyzed shotgun metagenomic data from previously published gut microbiome studies of semi-isolated human groups: semi-isolated hunter-gatherer communities from South America and Africa (Yanomami from Brazilian Amazon19, n = 15; Matses from Peruvian Amazon16, n = 24; and Hadza from Tanzania17, n = 27), and a rural agriculturalist community from the Andean highlands in Peru (Tunapuco16, n = 12). These datasets comprise paired-end sequences generated on Illumina sequencers, and bioinformatic processing was performed in parallel. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The diet of the hunter-gatherer communities is mainly based on the consumption of highly fibrous tubers and vegetal foods, while the diet of the rural agriculturalist community is based on the local agricultural produce of stem and root tubers, and homegrown small animals.

Each metagenome was independently subjected to de novo assembly through metaSPAdes v.3.1360 using default parameters. For plasmid identification, MOB-recon and MOB-typer modules from the MOB-suite program were used61. These modules identified putative plasmids from the contigs of each metagenome and searched for replication gene (rep), mobilization protein (relaxase), mate-pair formation (MPF), and the origin of transfer (oriT). Based on the presence/absence of these plasmid markers, the plasmids’ mobility was predicted61. Optional tools for the classification of potential circular or linear plasmids were not performed and it is reasonable to expect the recovery of both types of plasmids. To avoid false positives we removed from the analysis the plasmids with no markers identified by the MOB-suite. For characterization, pairwise genomic distances between each plasmid identified and each reference plasmid cluster was calculated. Thus, each plasmid identified was assigned to their closest reference plasmid cluster or as a novel plasmid depending on the predicted genomic distance, using the MOB-suite database as reference61. Following the MOB-suite analysis, the function “dist” of the Mash program62 was used to calculate the pairwise genomic distances between all novel plasmids identified in the groups. If the distance between the novel plasmids was lower than 0.05, they were assigned to the same novel cluster. This distance metric allows the clustering of plasmids with considerable differences in length, which is useful in this case, since plasmids can undergo diverse changes in their sequence content61. Based on the clustering classification, the plasmids were split into three groups. Group 1 comprises plasmids that were assigned to plasmid clusters from the reference database. Group 2 comprises plasmids assigned as novel and clustered into novel clusters. Group 3 comprises unique plasmids, with no significant similarity/coverage to the plasmids in the database or to other plasmids found in the metagenomes. Moreover, only plasmid clusters identified in at least three metagenomes from one same human group were considered with the potential to be group-specific.

We also used FragGeneScan v.1.3163 to predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) in the contigs assigned as plasmids. Thereafter, Abricate (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate) was used to screen the ORFs against the MegaRes v.264 and VFDB65 databases. Abricate results were filtered for a minimum DNA identity of 75% and minimum coverage of 50%66. Functional annotation and assignment of KEGG functional categories to the ORFs were performed using the KOfamKOALA tool67, considering a threshold of 0.01. The plasmids were also annotated using Prokka68 for transposase identification.

Network analysis of the plasmids identified in the four groups was performed based on the plasmid clusters characterized by MOB-suite. The network was constructed with the igraph R package (http://igraph.org/r/). In this network, the smaller-sized nodes represent the plasmids, which are linked to the bigger-sized nodes that represent the groups that harbor these plasmids. We removed from this analysis non-mobilizable plasmids that were identified in only one metagenome.

In order to investigate which other hosts and niches these plasmids have been identified, we performed a search analysis on each plasmid using the online BLAST tool69 with the nt/nr database. We removed results with similarity and coverage less than 70% and e-value less than 1e-5. To recover metadata information from the accession numbers of the plasmids that matched our putative plasmids, we used a custom python script based on the Entrez module of the Biopython package.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the support given by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) [Finance Code 001]; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ); and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.C. and A.V.; Methodology, Formal analysis and Investigation: L.C.; Supervision: A.V.; Writing: L.C. and A.V.

Data availability

The metagenomic data of the gut microbiomes used in this study were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) BioProject PRJNA268964 for Reference 16, BioProject PRJNA278393 for Reference 17, and BioProject PRJNA527208 for Reference 19. The putative plasmids generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-16392-z.

References

- 1.Dionisio F, Matic I, Radman M, Rodrigues OR, Taddei F. Plasmids spread very fast in heterogeneous bacterial communities. Genetics. 2002;162(4):1525–1532. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Chen X, Skogerbø G, Zhang P, Chen R, He S, Huang DW. The human microbiome: A hot spot of microbial horizontal gene transfer. Genomics. 2012;100(5):265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne MJ, Zitomersky NL, McGuire AM, Earl AM, Comstock LE. Evidence of extensive DNA transfer between bacteroidales species within the human gut. MBio. 2014;5:e01305–e1314. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01305-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner A, Matthias T, Aminov R. Potential effects of horizontal gene exchange in the human gut. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Licht TR, Wilcks A. Conjugative gene transfer in the gastrointestinal environment. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;58C:77–95. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(05)58002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broaders E, Gahan CG, Marchesi JR. Mobile genetic elements of the human gastrointestinal tract: potential for spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Gut Microbes. 2013;4(4):271–280. doi: 10.4161/gmic.24627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito IL, Yilmaz S, Huang K, Xu L, Jupiter SD, Jenkins AP, Naisilisili W, Tamminen M, Smillie CS, Wortman JR, Birren BW, Xavier RJ, Blainey PC, Singh AK, Gevers D, Alm EJ. Mobile genes in the human microbiome are structured from global to individual scales. Nature. 2016;535(7612):435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature18927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumpert H, Kubicek-Sutherland JZ, Porse A, Karami N, Munck C, Linkevicius M, Adlerberth I, Wold AE, Andersson DI, Sommer MOA. Transfer and persistence of a multi-drug resistance plasmid in situ of the infant gut microbiota in the absence of antibiotic treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2017;26(8):1852. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wein T, Hulter NF, Mizrahi I, Dagan T. Emergence of plasmid stability under non-selective conditions maintains antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2595. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10600-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tepekule B, Abel Zur Wiesch P, Kouyos RD, Bonhoeffer S. Quantifying the impact of treatment history on plasmid-mediated resistance evolution in human gut microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116(46):23106–23116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912188116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culligan EP, Sleator RD, Marchesi JR, Hill C. Functional metagenomics reveals novel salt tolerance loci from the human gut microbiome. ISME J. 2012;6(10):1916–1925. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broaders E, O'Brien C, Gahan CG, Marchesi JR. Evidence for plasmid-mediated salt tolerance in the human gut microbiome and potential mechanisms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016;92(3):19. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hols P, Ledesma-García L, Gabant P, Mignolet J. Mobilization of microbiota commensals and their bacteriocins for therapeutics. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27(8):690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarowska J, Futoma-Koloch B, Jama-Kmiecik A, Frej-Madrzak M, Ksiazczyk M, Bugla-Ploskonska G, Choroszy-Krol I. Virulence factors, prevalence and potential transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from different sources: Recent reports. Gut Pathog. 2019;21(11):10. doi: 10.1186/s13099-019-0290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnorr SL, Candela M, Rampelli S, Centanni M, Consolandi C, Basaglia G, Turroni S, Biagi E, Peano C, Severgnini M, Fiori J, Gotti R, De Bellis G, Luiselli D, Brigidi P, Mabulla A, Marlowe F, Henry AG, Crittenden AN. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat. Commun. 2014;15(5):3654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obregon-Tito AJ, Tito RY, Metcalf J, Sankaranarayanan K, Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Zech XuZ, Van Treuren W, Knight R, Gaffney PM, Spicer P, Lawson P, Marin-Reyes L, Trujillo-Villarroel O, Foster M, Guija-Poma E, Troncoso-Corzo L, Warinner C, Ozga AT, Lewis CM. Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 2015;25(6):6505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rampelli S, Schnorr SL, Consolandi C, Turroni S, Severgnini M, Peano C, Brigidi P, Crittenden AN, Henry AG, Candela M. Metagenome sequencing of the hadza hunter-gatherer gut microbiota. Curr. Biol. 2015;25(13):1682–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, Turroni F, Ferrario C, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1379–1390. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conteville LC, Oliveira-Ferreira J, Vicente ACP. Gut Microbiome biomarkers and functional diversity within an amazonian semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer group. Front. Microbiol. 2019;30(10):1743. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hehemann JH, Correc G, Barbeyron T, Helbert W, Czjzek M, Michel G. Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature. 2010;464(7290):908–912. doi: 10.1038/nature08937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravi A, Estensmo ELF, Abée-Lund TML, Foley SL, Allgaier B, Martin CR, Claud EC, Rudi K. Association of the gut microbiota mobilome with hospital location and birth weight in preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2017;82(5):829–838. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW, Schwarz C, Froese D, Zazula G, Calmels F, Debruyne R. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature. 2011;477(7365):457. doi: 10.1038/nature10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smillie C, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EP, de la Cruz F. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74(3):434–452. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemente JC, Pehrsson EC, Blaser MJ, Sandhu K, Gao Z, Wang B, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Contreras M, Noya-Alarcón Ó, Lander O, McDonald J, Cox M, Walter J, Oh PL, Ruiz JF, Rodriguez S, Shen N, Song SJ, Metcalf J, Knight R, Dantas G, Dominguez-Bello MG. The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians. Sci Adv. 2015;1(3):e1500183. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pehrsson EC, Tsukayama P, Patel S, Mejía-Bautista M, Sosa-Soto G, Navarrete KM, Calderon M, Cabrera L, Hoyos-Arango W, Bertoli MT, Berg DE, Gilman RH, Dantas G. Interconnected microbiomes and resistomes in low-income human habitats. Nature. 2016;533(7602):212–216. doi: 10.1038/nature17672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smits SA, Leach J, Sonnenburg ED, Gonzalez CG, Lichtman JS, Reid G, Knight R, Manjurano A, Changalucha J, Elias JE, Dominguez-Bello MG, Sonnenburg JL. Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science. 2017;357(6353):802–806. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta VK, Paul S, Dutta C. Geography, ethnicity or subsistence-specific variations in human microbiome composition and diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2017;23(8):1162. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo T, Kamm MA, Colombel JF, Ng SC. Urbanization and the gut microbiota in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15(7):440–452. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17(4):219–232. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, de la Cruz F. The diversity of conjugative relaxases and its application in plasmid classification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33(3):657–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douarre PE, Mallet L, Radomski N, Felten A, Mistou MY. Analysis of COMPASS, a new comprehensive plasmid database revealed prevalence of multireplicon and extensive diversity of IncF plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 2020;24(11):483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sioli H. The Amazon and its Main Affluents: Hydrography, Morphology of the River Courses, and River Types. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 127–165. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verìssimo A, Capobianco JPR. Biodiversidade na Amazônia Brasileira: Avaliação E Ações Prioritárias Para a Conservação, Uso Sustentável e Repartição de Benefícios. Instituto Socioambiental. (2001). Available at: https://books.google.com.br/books/about/Biodiversidade_na_amazonia_brasileira.html?id=VrhcAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y Accessed from 4 May 2021.

- 34.Oliphant K, Allen-Vercoe E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: Major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0704-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fragiadakis GK, Smits SA, Sonnenburg ED, Van Treuren W, Reid G, Knight R, Manjurano A, Changalucha J, Dominguez-Bello MG, Leach J, Sonnenburg JL. Links between environment, diet, and the hunter-gatherer microbiome. Gut Microbes. 2019;10(2):216–227. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1494103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin TL, Shu CC, Chen YM, Lu JJ, Wu TS, Lai WF, Tzeng CM, Lai HC, Lu CC. Like cures like: Pharmacological activity of anti-inflammatory lipopolysaccharides from gut microbiome. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;30(11):554. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogilvie LA, Firouzmand S, Jones BV. Evolutionary, ecological and biotechnological perspectives on plasmids resident in the human gut mobile metagenome. Bioeng. Bugs. 2012;3(1):13–31. doi: 10.4161/bbug.3.1.17883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almeida A, Nayfach S, Boland M, Strozzi F, Beracochea M, Shi ZJ, Pollard KS, Sakharova E, Parks DH, Hugenholtz P, Segata N, Kyrpides NC, Finn RD. A unified catalog of 204,938 reference genomes from the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39(1):105–114. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurokawa K, Itoh T, Kuwahara T, Oshima K, Toh H, Toyoda A, Takami H, Morita H, Sharma VK, Srivastava TP, Taylor TD, Noguchi H, Mori H, Ogura Y, Ehrlich DS, Itoh K, Takagi T, Sakaki Y, Hayashi T, Hattori M. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res. 2007;14(4):169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smillie CS, Smith MB, Friedman J, Cordero OX, David LA, Alm EJ. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature. 2011;480(7376):241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature10571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logan SL, Thomas J, Yan J, Baker RP, Shields DS, Xavier JB, Hammer BK, Parthasarathy R. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system can modulate host intestinal mechanics to displace gut bacterial symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115(16):E3779–E3787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720133115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peñil-Celis A, Garcillán-Barcia MP. Crosstalk between type VI secretion system and mobile genetic elements. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;13(6):126. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Custodio R, Ford RM, Ellison CJ, Liu G, Mickute G, Tang CM, Exley RM. Type VI secretion system killing by commensal Neisseria is influenced by expression of type four pili. Elife. 2021;7(10):e63755. doi: 10.7554/eLife.63755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez MF, Kurth D, Farías ME, et al. First report on the plasmidome from a high-altitude lake of the andean puna. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1343. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibson MK, Forsberg KJ, Dantas G. Improved annotation of antibiotic resistance determinants reveals microbial resistomes cluster by ecology. ISME J. 2015;9(1):207–216. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benveniste R, Davies J. Aminoglycoside antibiotic-inactivating enzymes in actinomycetes similar to those present in clinical isolates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1973;70(8):2276–2280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forsberg KJ, Reyes A, Wang B, Selleck EM, Sommer MO, Dantas G. The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science. 2012;337(6098):1107–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.1220761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiu K, Warner G, Nowak RA, Flaws JA, Mei W. The impact of environmental chemicals on the gut microbiome. Toxicol. Sci. 2020;176(2):253–284. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leitão JH. Microbial virulence factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(15):5320. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandler M, Fayet O, Rousseau P, Ton Hoang B, Duval-Valentin G. Copy-out–paste-in transposition of IS 911: A major transposition pathway. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015;3(4):3–4. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0031-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dumas E, Christina Boritsch E, Vandenbogaert M, et al. Mycobacterial pan-genome analysis suggests important role of Plasmids in the radiation of type VII secretion systems. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8(2):387–402. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgado SM, Paulo Vicente AC. Genomics of Atlantic Forest Mycobacteriaceae strains unravels a mobilome diversity with a novel integrative conjugative element and plasmids harbouring T7SS. Microb. Genom. 2020;6(7):mgen000382. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wisniewski JA, Traore DA, Bannam TL, Lyras D, Whisstock JC, Rood JI. TcpM: A novel relaxase that mediates transfer of large conjugative plasmids from Clostridium perfringens. Mol. Microbiol. 2016;99(5):884–896. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coluzzi C, Guédon G, Devignes MD, Ambroset C, Loux V, Lacroix T, Payot S, Leblond-Bourget N. A glimpse into the world of integrative and mobilizable elements in streptococci reveals an unexpected diversity and novel families of mobilization proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2017;20(8):443. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramachandran G, Miguel-Arribas A, Abia D, Singh PK, Crespo I, Gago-Córdoba C, Hao JA, Luque-Ortega JR, Alfonso C, Wu LJ, Boer DR, Meijer WJ. Discovery of a new family of relaxases in Firmicutes bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(2):e1006586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guzmán-Herrador DL, Llosa M. The secret life of conjugative relaxases. Plasmid. 2019;104:102415. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.102415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soler N, Robert E, Chauvot de Beauchêne I, Monteiro P, Libante V, Maigret B, Staub J, Ritchie DW, Guédon G, Payot S, Devignes MD, Leblond-Bourget N. Characterization of a relaxase belonging to the MOBT family, a widespread family in Firmicutes mediating the transfer of ICEs. Mob. DNA. 2019;10:18. doi: 10.1186/s13100-019-0160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Acman M, van Dorp L, Santini JM, Balloux F. Large-scale network analysis captures biological features of bacterial plasmids. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):2452. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16282-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):824–834. doi: 10.1101/gr.213959.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robertson J, Nash JHE. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb Genom. 2018;4(8):e000206. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ondov BD, Treangen TJ, Melsted P, Mallonee AB, Bergman NH, Koren S, Phillippy AM. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rho M, Tang H, Ye Y. FragGeneScan: predicting genes in short and error-prone reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(20):e191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doster E, Lakin SM, Dean CJ, Wolfe C, Young JG, Boucher C, Belk KE, Noyes NR, Morley PS. MEGARes 2.0: A database for classification of antimicrobial drug, biocide and metal resistance determinants in metagenomic sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D561–D569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen L, Yang J, Yu J, Yao Z, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin Q. VFDB: A reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D325–D328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carroll LM, Wiedmann M, den Bakker H, Siler J, Warchocki S, Kent D, Lyalina S, Davis M, Sischo W, Besser T, Warnick LD, Pereira RV. Whole-genome sequencing of drug-resistant salmonella enterica isolates from dairy cattle and humans in New York and Washington States reveals source and geographic associations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83(12):e00140–e217. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00140-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aramaki T, Blanc-Mathieu R, Endo H, Ohkubo K, Kanehisa M, Goto S, Ogata H. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(7):2251–2252. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 2009;15(10):421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The metagenomic data of the gut microbiomes used in this study were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) BioProject PRJNA268964 for Reference 16, BioProject PRJNA278393 for Reference 17, and BioProject PRJNA527208 for Reference 19. The putative plasmids generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.