Abstract

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a complex multisystem disorder characterized by orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia and may be triggered by viral infection. Recent reports indicate that 2%–14% of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survivors develop POTS and 9%–61% experience POTS-like symptoms, such as tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance, fatigue, and cognitive impairment within 6–8 months of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Pathophysiological mechanisms of post–COVID-19 POTS are not well understood. Current hypotheses include autoimmunity related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, autonomic dysfunction, direct toxic injury by SARS-CoV-2 to the autonomic nervous system, and invasion of the central nervous system by SARS-CoV-2. Practitioners should actively assess POTS in patients with post–acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms. Given that the symptoms of post–COVID-19 POTS are predominantly chronic orthostatic tachycardia, lifestyle modifications in combination with the use of heart rate–lowering medications along with other pharmacotherapies should be considered. For example, ivabradine or β-blockers in combination with compression stockings and increasing salt and fluid intake has shown potential. Treatment teams should be multidisciplinary, including physicians of various specialties, nurses, psychologists, and physiotherapists. Additionally, more resources to adequately care for this patient population are urgently needed given the increased demand for autonomic specialists and clinics since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering our limited understanding of post–COVID-19 POTS, further research on topics such as its natural history, pathophysiological mechanisms, and ideal treatment is warranted. This review evaluates the current literature available on the associations between COVID-19 and POTS, possible mechanisms, patient assessment, treatments, and future directions to improving our understanding of post–COVID-19 POTS.

Keywords: Autonomic dysfunction, COVID-19, Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, POTS, Dysautonomia, Long COVID, Post–COVID-19 POTS, Orthostatic intolerance, Tachycardia

A. Introduction

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a heterogeneous multifactorial disorder characterized by orthostatic tachycardia and intolerance, which significantly impairs quality of life.1 Patients with POTS experience cardiac (eg, palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance) and/or noncardiac (eg, mental clouding/“brain fog,” headaches, lightheadedness, fatigue, muscle weakness, gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbances, and chronic pain) symptoms, all of which reduce daily functional capacity.2, 3, 4, 5 Currently, the pathophysiology of POTS is not well-understood.1 , 5 Autonomic dysfunction, physical deconditioning, hypovolemia, and immunological mechanisms are among the factors contributing to symptoms of POTS.5

Recently, a number of case reports have been published describing patients who developed chronic symptoms and signs after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, which have been called “post–acute coronavirus disease (COVID) syndrome,” “post–acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 syndrome,” “post–coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome,” “long-haul COVID,” or “long COVID” and are usually defined as symptoms that persist for >4 weeks from acute illness.6 For the purposes of this article, we will refer to this disorder as long COVID. The symptoms of long COVID include breathlessness, palpitations, chest discomfort, fatigue, pain, cognitive impairment (brain fog), sleep disturbance, orthostatic intolerance, peripheral neuropathy symptoms, abdominal discomfort, nausea, diarrhea, joint and muscle pains, symptoms of anxiety or depression, skin rashes, sore throat, headache, earache, and tinnitus.6, 7, 8 Some of the symptoms and signs of long COVID, when combined with orthostatic tachycardia (typically an increase in 30 beats/min from lying to standing), can indicate a diagnosis of POTS associated with and/or induced by COVID-19 (referred to as post–COVID-19 POTS).6 , 9 We provide a timely and important review of the link between POTS and COVID-19, furthering our understanding on possible mechanisms, treatments, and future directions related to post–COVID-19 POTS.

B. POTS: Prevalence, clinical presentation, and pathophysiology

POTS predominantly affects young women, is the most prevalent form of orthostatic intolerance and dysautonomia, and has a global prevalence of 500,000 to 3 million people.5 , 10 Clinically, POTS is defined as chronic orthostatic intolerance with a heart rate (HR) increase of ≥30 beats/min within 10 minutes of standing up and without significant hypotension.5 In addition to the rapid increase in HR, patients can experience palpitations, dyspnea, syncope, brain fog, lightheadedness, blurred/tunnel vision, tremulousness, fatigue, weakness, chronic pain (eg, headache, temporomandibular joint disorder, and fibromyalgia), gastrointestinal issues (eg, abdominal pain, bloating, gastroparesis, and nausea), and sleep disturbances.2 , 4 , 10 , 11 Many of these symptoms of POTS overlap with symptoms seen in patients with long COVID.7

POTS symptoms may be induced by physical deconditioning, immunological factors, hypovolemia, autonomic dysfunction, elevated sympathetic tone, and venous pooling.1 , 10 , 12 Precipitating features of dysautonomia in POTS include baroreceptor dysregulation, elevated standing serum norepinephrine levels, and peripheral neuropathy, all of which can manifest simultaneously.13

Common comorbidities of POTS are mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, sensory neuropathy, venous compression syndromes, and autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and celiac disease.5 , 9 , 11 , 14 , 15

POTS symptoms can significantly impair functional status, mental health, and quality of life, making it difficult to work and causing many patients to become bedridden.1 , 10 , 16 In fact, ∼25% of patients with POTS report being unable to work and patients with POTS may also be at higher risk of depression.1 , 16 , 17 Moreover, a cross-sectional survey of 5556 adults with POTS found that 70% have experienced a loss of income and 21% have experienced job loss due to POTS.18

There are 5 subtypes of POTS based on its pathophysiology: joint hypermobility–related, neuropathic, hyperadrenergic, hypovolemic, and immune-related.10 Subtypes are not mutually exclusive and may overlap. Interestingly, nearly half of POTS cases are precipitated by acute viral infection and research suggests that postviral autoimmune activation may cause POTS.5 , 19 Common precipitating viral infections include Epstein-Barr virus causing mononucleosis, influenza, upper respiratory infections, and gastroenteritis; however, the mechanism behind these infectious triggers is still unclear.1 , 9 There is some evidence to suggest physical deconditioning that is preexisting or that often occurs after a viral illness may cause patients to be more vulnerable to acute viral infection–induced POTS.1 , 20

There is also a growing body of evidence reporting the presence of antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, α1, β1, and β2 adrenergic receptors antibodies, angiotensin 2 type 1 receptor antibodies, ganglionic N-type and P/Q-type acetylcholine receptor antibodies, opioid-like 1 receptor antibodies, and muscarinic M2 and M4 antibodies in patients with POTS.1 , 9 , 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The presence of these antibodies, suggesting autoimmunity, may explain some dysautonomia symptoms (eg, tachycardia and elevated standing plasma norepinephrine levels) found in POTS.21

Dysautonomia symptoms have been previously reported in patients who recovered from SARS during the 2002 SARS epidemic.26, 27, 28 These patients reported fatigue, malaise, orthostatic intolerance, headaches, and dizziness upon standing. More recently, numerous case reports and studies have described patients recovering from COVID-19 as presenting with significant and debilitating POTS and POTS-like symptoms, suggesting that COVID-19 is yet another viral infection that can trigger POTS and that POTS is a distinct phenotype of long COVID.9 , 13 , 19 , 29, 30, 31 The associations between long COVID and POTS should thus be recognized and assessed in COVID-19 survivors.11 , 31 , 32 In addition, on the basis of our clinical experience, we have found that patients have less functional impairment and overall better quality of life when POTS is diagnosed and treated early in the course of long COVID. However, further research is needed to verify our findings.

C. Post–COVID-19 POTS

C.1. Prevalence and clinical presentation

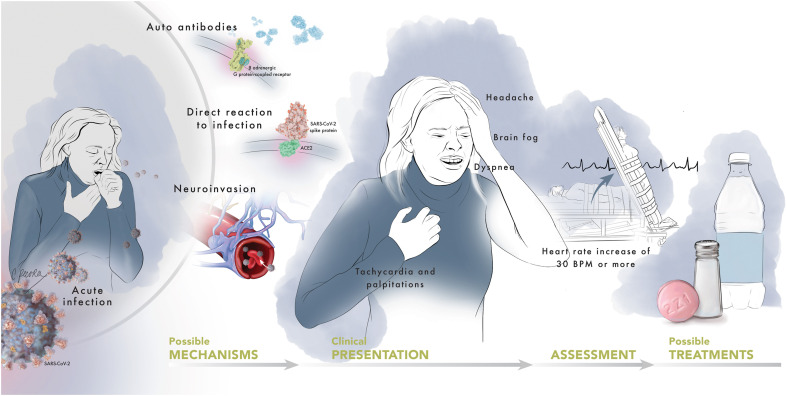

POTS and long COVID are both multisystem disorders.11 , 31 , 32 Although our knowledge of the prevalence of POTS in COVID-19 survivors is limited by most studies being retrospective or having small sample sizes, it is estimated that 2%–14% of COVID-19 survivors develop POTS and 9%–61% experience POTS-like symptoms, such as tachycardia and palpitations, within 6–8 months of infection (Figure 1 ).9 , 19 , 33, 34, 35 Additionally, symptoms suggestive of autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic intolerance and gastrointestinal dysfunction, as well as features of a hyperadrenergic state and symptoms of MCAS have been observed.9 , 19 , 36 , 37 Although a review by Larsen et al36 suggests that POTS may be the most common form of autonomic dysfunction in patients with long COVID, orthostatic intolerance and other autonomic abnormalities in the absence of POTS should also be considered.38 , 39 In patients with symptoms related to autonomic dysfunction arising in the parainfectious or postinfectious period of COVID-19 (n = 27), 63% of patients had abnormalities on autonomic function testing, most commonly orthostatic intolerance, and 22% of patients fulfilled criteria for POTS.39 However, the majority of patients experiencing orthostatic symptoms had normal autonomic testing results. Ultimately, expanded retrospective and prospective studies are needed to further explore and characterize the mechanisms and spectrum of autonomic dysfunction related to COVID-19, its long-term natural history, and management.

Figure 1.

Possible pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical presentations, assessment, and treatments for post–COVID-19 POTS. After infection by SARS-CoV-2, POTS may develop due to the production of autoantibodies that trigger sympathetic activation, direct reaction to infection, or invasion of the central nervous system. Common symptoms of post–COVID-19 POTS are tachycardia, headaches, brain fog, and dyspnea. Post–COVID-19 POTS can be assessed using a head-up tilt table test and managed with lifestyle changes (eg, increased salt and fluid intake and non–upright exercise) and pharmacotherapy (eg, heart rate–lowering medication). COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Illustration provided by Christina Pecora, MSMI, CMI.

There have also been reports of an increased incidence and number of referrals for POTS in autonomic clinics in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.6 , 36 Additionally, a global survey of 3762 COVID-19 survivors found that 30% of patients who developed chronic tachycardia after infection (n = 1680) reported experiencing an HR increase of >30 beats/min upon assuming an upright position.35 Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Lopez-Leon et al,7 which included 47,910 COVID-19 survivors aged 17–87 years, found that 80% of patients experience ≥1 long-term symptom in the period from 14 to 110 days post–viral infection. Among these patients, 58% report fatigue, 44% headaches, 27% brain fog or cognitive impairment, 24% dyspnea, 11% tachycardia and palpitations, and 10% decreased exercise tolerance,7 all of which are common symptoms of POTS. In fact, in a retrospective case review of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who underwent autonomic testing, it was posited that infection-related orthostatic intolerance is more common after COVID-19 infection than any other viral infection.39 Post–COVID-19 POTS can be severely debilitating, with a case series of 20 patients with dysautonomia after infection (75% of whom diagnosed with POTS) finding that 60% were unable to return to work and 25% needed work accommodations 8 months after infection.9

While the occurrence of post–COVID-19 POTS is reported by several authors,19 , 36 , 37 , 39 it is difficult to assess an exact prevalence of POTS in COVID-19 survivors because of a heterogeneity of examined populations and a lack of applying rigorous diagnostic criteria for POTS diagnosis in existing studies. According to the available data, 9% of 1733 patients with COVID-19 reported palpitations at 6 months after symptom onset.34 In addition, the prevalence of both resting HR increase and palpitations was 11% in 47,910 patients with long-COVID syndrome.7 Clinical data provided by Ståhlberg et al31 found that 25%–50% of patients at a tertiary post-COVID-19 multidisciplinary clinic reported tachycardia or palpitations persisting >12 weeks. In a global survey of 3762 participants with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, ∼14% reported an increase in HR of >30 beats/min upon standing, suggesting the possibility of POTS (by the time respondents took the survey, 9% of them were diagnosed with POTS).35 Fifteen of 20 patients (75%) who presented to an outpatient referral dysautonomia clinic with persistent neurological and cardiovascular complaints after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, and who had evidence of orthostatic intolerance on a tilt table test or a 10-minute stand test, were diagnosed with POTS.9 Also, in a study by Shouman et al39 where autonomic testing was conducted for post–COVID-19 symptoms suggesting para-/postinfectious autonomic dysfunction, 22% of patients fulfilled the criteria for POTS. However, in an observational study of 85 patients with long COVID, POTS was diagnosed in only 2% of those with orthostatic intolerance (66% of total).38 In summary, we can estimate the prevalence of post–COVID-19 POTS as 2%–75% depending on the patient characteristics and applied diagnostic criteria. Most probably, it is ∼2%–14% in the general population of COVID-19 survivors,35 ∼22% in patients with symptoms indicating autonomic dysfunction,39 ∼31% of those who report tachycardia,35 and ∼75% of those with cardiovascular complaints and orthostatic intolerance.9 Further research, both basic and clinical, is needed to better understand the pathophysiology of post–COVID-19 POTS and establish its real prevalence.

C.2. Possible mechanisms

Presently, our knowledge of the mechanisms behind post–COVID-19 POTS is still evolving (Figure 1). Additionally, possible pathophysiological pathways are not mutually exclusive and may occur simultaneously or overlap.13 One possible mechanism is that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus causing COVID-19, triggers the production of autoantibodies, which in turn react with autonomic nerve fibers, autonomic ganglia, G protein–coupled receptors, or other neuronal or cardiovascular receptors, leading to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.9 , 39, 40, 41 By activating adrenergic and muscarinic receptors, autoantibodies may result in peripheral nervous system dysfunction and venous pooling, tachycardia, and autonomic dysregulation, subsequently manifesting as POTS.9 , 31 For instance, Blitshteyn and Whitelaw9 found elevated inflammatory cytokines and autoimmunity markers in patients presenting with autonomic dysfunction and POTS after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Another case report found elevated ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody levels (111 pmol/L; <53 pmol/L is ideal) in a patient with post–COVID-19 POTS.39 In addition, many patients after SARS-CoV-2 infection are physically deconditioned, which may further perpetuate a vicious cycle of POTS development.39 , 42

Alternatively, post–COVID-19 POTS may arise because of a direct toxic action of SARS-CoV-2 on target cells, leading to tissue injury.43 , 44 SARS-CoV-2 attaches its spike protein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor––which is expressed in multiple tissues––to enter cells, causing multisystem damage manifested as pulmonary and extrapulmonary COVID-19.43, 44, 45 Subsequent cardiovascular system damage can result from renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system dysregulation, hyperinflammation, and hypercoagulability with thrombosis (including microvascular thrombi).25 , 45 SARS-CoV-2 can cause structural damage to the lungs, kidneys, heart, liver, and pancreas, even in nonhospitalized low-risk patients or patients with mild symptoms.46, 47, 48 It has been suggested that several of these COVID-19 manifestations may contribute through various pathways to post–COVID-19 tachycardia and post–COVID-19 POTS.31 , 45 For example, COVID-19–related pulmonary injury can lead to reflex tachycardia and oxygen desaturation in COVID-19 survivors.49 Furthermore, a recent review on SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins posited that spike proteins can produce neurotoxic effects (eg, via endothelial damage, autoimmunity mechanisms, or neuroinflammation), which could possibly result in POTS symptoms, such as chronic fatigue and brain fog, after infection.47 , 50

Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 is known to have neuroinvasive capabilities via both direct and indirect mechanisms.51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 For the direct mechanism, SARS-CoV-2 invades the central nervous system and autonomic nervous system (ANS) through the olfactory nerve, neuronal pathways, blood circulation, and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the brainstem.57, 58, 59 In the indirect mechanism, it has been suggested that ANS invasion occurs through the enteric nervous system and its sympathetic afferent neurons through gastrointestinal tract infection.60 , 61 Autopsies of deceased patients with COVID-19 confirm SARS-CoV-2’s ability to invade the central nervous system, with SARS-CoV-2 RNA being found in the brain of 30%–40% of cases.62, 63, 64 Additionally, a postmortem case series of patients with COVID-19 found SARS-CoV-2 RNA and proteins in the brainstem of 50% and 40% of cases with available samples, respectively.65 Moreover, an autopsy analysis by Meinhardt et al66 of 33 patients with COVID-19 identified SARS-CoV-2 and spike proteins in the primary cardiovascular and respiratory centers of the medulla oblongata and the olfactory mucosal-neuronal junction, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 can infiltrate the brainstem via the olfactory system. The brainstem plays a vital role in regulating the cardiovascular system, ANS, and neurotransmitter systems.67 For example, the caudal ventrolateral medulla is responsible for sympathetic nervous system (SNS) control and heart rhythm.68 As such, SARS-CoV-2 brainstem invasion and disruption could possibly be related to autonomic dysregulation and several POTS symptoms (eg, tachycardia, brain fog, fatigue, and increased sympathetic activation) seen in patients with post–COVID-19.53 , 69

In addition, excessive bed rest, night sweats, fever, and nausea typically accompany SARS-CoV-2 infection and may interact synergistically to produce hypovolemia, baroreflex dysfunction, diminished cardiac output, and cardiac SNS activation.11 , 31 , 70 These symptoms can lead to physical deconditioning and ultimately POTS, causing patients to experience a cycle of exercise intolerance, chronic fatigue, low stroke volume, and increased SNS activation.11 , 32 , 71 Furthermore, infection-related stress can activate the SNS and trigger pro-inflammatory cytokine production (ie, cytokine storm) and sympathetic overstimulation, leading to tachycardia, tremors, and sweating.70 , 72 , 73 For instance, COVID-19–related cytokine hyperactivation is associated with SNS stimulation and has been noted in patients with long COVID presenting with chronic fatigue, orthostatic intolerance, presyncope, and brain fog.73 , 74

Another postulated mechanism is SARS-CoV-2 infecting and destroying extracardiac postganglionic SNS neurons via immune- or toxin-mediated pathways, thereby increasing cardiac sympathetic tone.60 , 73 However, there is no literature to support these possible mechanisms yet.

D. Patient assessment for post–COVID-19 POTS

Health practitioners should be actively assessing for POTS in COVID-19 survivors, especially in patients with long COVID symptoms. Given that existing studies have found POTS to be relatively common in COVID-19 survivors, all patients who present with any signs or symptoms of POTS, including tachycardia, palpitations, dizziness, lightheadedness, brain fog, fatigue, weakness, or exercise intolerance, should be screened for POTS (Figure 1). Also, both cardiac (related to structural cardiac damage, such as myocarditis and myocardial involvement) and extracardiac (such as pulmonary embolism, hyperthyroidism, pneumonia, anemia, and inflammatory disease) non–POTS-related causes of tachycardia should be excluded using various tests. Additionally, other causes of various symptoms associated with POTS (eg, exercise intolerance)––which may originate from various disorders related to COVID-19 other than POTS (eg, myocardial involvement, myocardial injury, and myocarditis)––should be investigated (eg, using cardiac imaging modalities such as echocardiography or biomarkers such as troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations).

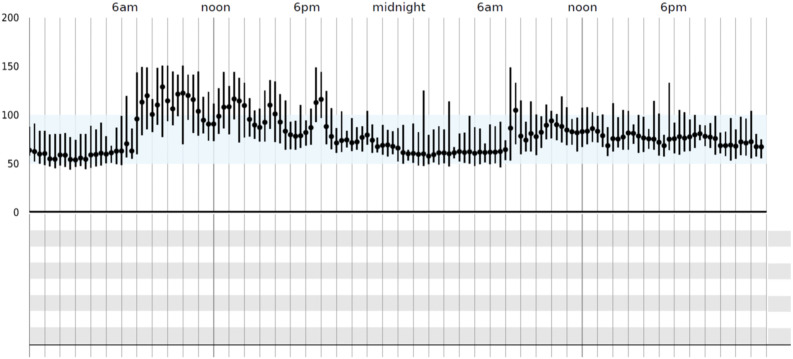

In addition to conducting a comprehensive physical examination, in-office orthostatic vitals (blood pressure/HR assessment after 10 minutes of being supine and after 10 minutes of standing) can help with the diagnosis of POTS. The diagnosis of POTS can subsequently be confirmed if the patient experiences a ≥30 beats/min HR increase without orthostatic hypotension within the first 10 minutes of a head-up tilt table test or standing test.1 , 75 It is also suggested that tilt table and standing tests be performed in the morning to maximize diagnostic sensitivity.76 Many patients may not have the classic 30-point increase in HR during their clinic visit and instead may exhibit a trend toward increased HR with standing. For these patients, an outpatient event monitor/Holter monitor can help delineate HR patterns (increased HR >100 beats/min during the day with minimal activity) (Figure 2 ) and rule out other arrhythmias.31 , 77 In addition, many patients with post–COVID-19 may exhibit inappropriate sinus tachycardia and may not have a postural increase in their HR.31 , 78 , 79 For patients with post–COVID-19 inappropriate sinus tachycardia, the treatment approach would be similar to POTS.31 For the majority of patients with post–COVID-19, minimal testing is required to evaluate for POTS.77 In some patients with suspected POTS, evaluation of autoantibodies/autoimmune biomarkers, plasma catecholamines, and comprehensive autonomic testing should also be considered. However, for patients whose symptoms do not improve or who have new cardiopulmonary symptoms during the post–COVID-19 period, additional testing outlined below should be considered.

Figure 2.

Example of 24-hour heart rate pattern on a Holter monitor. This figure shows heart rate patterns from an event monitor with elevated heart rates over 100 beats/min during waking hours with minimal activity. This assessment can help delineate heart rate patterns and rule out other arrhythmias. This pattern is suggestive of POTS/IST. An outpatient event monitor/Holter monitor can be used to assess POTS/IST in patients who have symptoms to suggest POTS/IST and but do not exhibit the 30 beats/min increase in HR during their clinic visit and exhibit a trend toward increased HR upon standing. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IST = inappropriate sinus tachycardia; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

A transthoracic echocardiogram can be used to rule out structural heart disease and to assess myocardial involvement related to COVID-19.1 , 31 Specifically, echocardiography is one of the 3 main basic cardiac testing modalities (along with electrocardiography and troponin concentration, ie, “triad testing”) recommended for evaluating and managing cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19.8 No cardiac testing is recommended for asymptomatic patients, patients with mild to moderate noncardiopulmonary symptoms, or patients with remote infection (≥3 months) without ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms. All patients with cardiopulmonary symptoms (eg, chest pain/pressure, dyspnea, palpitations, and syncope) require cardiac testing including echocardiogram.

Importantly, numerous presentations of myocardial involvement related to COVID-19 have been reported and include, but are not limited to, myocarditis, acute coronary syndrome, demand ischemia, multisystem inflammatory syndrome, Takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy, cytokine storm, acute cor pulmonale resulting from macropulmonary or micropulmonary emboli, myocardial injury from chronic conditions such as preexisting heart failure, and acute viral infection unmasking subclinical heart disease, in all of which echocardiography plays an important role for diagnostics and risk stratification.8 Echocardiographic data from prospective studies of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 suggest that myocardial dysfunction, ranging from abnormal ventricular strain to overt left and right ventricular systolic dysfunction, may be present in up to 40%.80 , 81

If an abnormal result of initial cardiac testing is obtained, additional tests may be needed. This can include cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging for suspected myocarditis, coronary angiography for suspected acute coronary syndrome, or computed tomography pulmonary angiography for suspected pulmonary embolism.8 Although a recent population-based study of young adults (aged <20 years) from 48 US health care organizations estimated the incidence of myocarditis with COVID-19 at ∼450 per million, prospective and retrospective studies of hospitalized patients, autopsy data, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance suggest that the overall incidence is higher.82

E. Management of post–COVID-19 POTS

Until more evidence emerges on whether treating post–COVID-19 POTS is different from treating non–COVID-19-related POTS, current guidelines for POTS should be used for patients presenting with post–COVID-19 POTS.36 Nonpharmacotherapy options include increasing fluid (2–3 L/d) and salt (10–12 g/d) intake, avoiding excessive standing and dehydration, wearing compression socks, and performing physical counterpressure measures.13 , 33 , 77 , 83 It is also recommended by the Heart Rhythm Society that nonpharmacological therapies be used first and pharmacological intervention be used when necessary.77 Although increasing exercise has been suggested in some long COVID treatment guidelines,70 it should be noted that some patients with post–COVID-19 dysautonomia and POTS have reported post–exertional malaise, exercise intolerance, and chronic fatigue.7 , 35 Providers (eg, physicians, physiotherapists, and nurse practitioners) should incrementally implement exercise therapy that is specific for POTS (eg, Levine protocol) and physical reconditioning measures.36 Patients should be educated on physical counterpressure measures and exercises that can be performed in a semi-recumbent or supine position, as these can improve both mental and physical well-being.83, 84, 85, 86, 87 For example, graded exercise combined with increased salt and water intake has been shown to significantly improve quality of life and blunt the HR increase from supine to standing.87 Also, medications that increase HR, lower blood pressure, and may cause or worsen orthostatic intolerance should be discontinued when possible.77 This includes, but is not limited to, α-receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, ganglionic blocking agents, hydralazine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, nitrates, opiates, phenothiazines, sildenafil citrate, tricyclic antidepressants, oral contraceptives containing drospirenone, norepinephrine transporter inhibitors, or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.33 , 77

Pharmacological intervention may be warranted if lifestyle modifications do not succeed in relieving POTS symptoms.70 , 77 While no specific pharmacological therapies are currently approved for the treatment of patients with post–COVID-19 POTS, various treatments may be used empirically.1 , 8 , 10 , 77 , 88 Given that there is no standardized formula for treatment, the type of medication is individualized for each patient and dependent on a patient’s underlying symptoms and suspected phenotype.77 , 88 Some current medications and their targeted pathophysiological pathways and symptoms include (in alphabetical order) antihistamines (MCAS), β-blockers (tachycardia and hyperadrenergic state),89 clonidine and α-methyldopa (hyperadrenergic state and tachycardia),90 , 91 desmopressin acetate (hypovolemia and orthostatic intolerance),92 droxidopa (hypovolemia and orthostatic intolerance; note that the use of droxidopa for POTS requires further investigation in clinical trials),93 fludrocortisone (hypovolemia and orthostatic intolerance),94 , 95 ivabradine (tachycardia),10 midodrine (venous pooling and orthostatic intolerance),96 modafinil (brain fog),97 nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (tachycardia),98 pyridostigmine (tachycardia and muscle weakness), saline intravenously (hypovolemia and orthostatic intolerance),99 , 100 and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (venous pooling, orthostatic intolerance, and psychotropic effect).1 , 31 , 77 , 88 , 101 , 102 Potential pharmacotherapies (medications with suggested doses) to treat POTS symptoms in COVID-19 survivors are summarized in Table 1 . It should be noted that patients with POTS are often more sensitive to pharmacological treatments.88 As such, treatments should be initiated with the lowest dose and increased only when needed to improve symptoms and provided the drug is well-tolerated.88 For example, if tachycardia predominates, a low-dose β-blocker (eg, bisoprolol, metoprolol, nebivolol, propranolol) or a nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (eg, diltiazem, verapamil) may be added and gradually titrated to slow the HR.8 Medications can also be used in combination with one another given their specific mechanisms of action.88

Table 1.

| Medication | Targeted disorder(s)/symptom(s) | Suggested dose |

|---|---|---|

| Acute saline intravenously | Hypovolemia, orthostatic intolerance | 2 L intravenously over 2–3 h |

| Antihistamines | Mast cell activation syndrome | Depending on the specific medication |

| β-Blocker (bisoprolol, metoprolol, nebivolol, propranolol) | Tachycardia Propranolol: tachycardia, hyperadrenergic state, exercise intolerance, orthostatic intolerance, migraine, anxiety |

Depending on the specific medication Propranolol: 10–20 mg, ≤4× daily |

| Clonidine | Hyperadrenergic state, tachycardia | 0.1–0.2 mg, 2–3× daily or long-acting patch |

| Desmopressin acetate | Hypovolemia, orthostatic intolerance | 0.1–0.2 mg, as needed |

| Droxidopa | Hypovolemia, orthostatic intolerance Note: the use of droxidopa for POTS requires further investigation in clinical trials |

100–600 mg, 3× daily |

| Fludrocortisone | Hypovolemia, orthostatic intolerance | 0.1–0.2 mg, daily (at night) |

| Ivabradine | Tachycardia, fatigue10 | 2.5–7.5 mg, 2× daily |

| α-Methyldopa | Hyperadrenergic state, tachycardia | 125–250 mg, 2× daily |

| Midodrine | Venous pooling, orthostatic intolerance | 2.5–10 mg, 3× daily (the first dose taken in the morning before getting out of bed and the last dose taken no later than 4 PM; typically at 8 AM, 12 PM, and 4 PM) |

| Modafinil | “Brain fog” | 50–200 mg, 1–2× daily |

| Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (verapamil, diltiazem) | Tachycardia | Depending on the specific medication |

| Pyridostigmine | Tachycardia, muscle weakness | 30–60 mg, ≤3× daily |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Venous pooling, orthostatic intolerance, psychotropic effect |

Depending on the specific medication |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Given that the symptoms of post–COVID-19 POTS are predominantly chronic orthostatic tachycardia, a combination of graded exercise rehabilitation and medications that selectively lower HR is recommended.31 , 77 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 103 For example, in the first case report of post–COVID-19 POTS, Miglis et al37 reported complete symptom improvement after prescription of compression socks, increased salt and fluid intake, clonidine, and propranolol. Another case series found prescribing a low-dose β-blocker, rehabilitative reconditioning, and cognitive behavioral therapy yielded complete resolution of symptoms in a patient with post–COVID-19 POTS.39 In their case report, Kanjwal et al104 found that ivabradine and increased salt and fluids significantly improved orthostatic symptoms and tachycardia. Interestingly, a case series of 3 patients diagnosed with POTS after SARS-CoV-2 infection found that while β-blockers (the type of β-blockers was unspecified) coupled with compression stockings and increased fluid and salt intake did not ameliorate symptoms and sometimes even worsened symptoms, switching to ivabradine resulted in significant improvement.19 Other case reports have also suggested that ivabradine combined with lifestyle modifications such as compression socks and greater salt/fluid intake may work well.9 , 13 , 19 , 70 , 104 , 105 Mechanistically, ivabradine’s potential to effectively treat post–COVID-19 POTS is tenable given that it selectively inhibits the Ifunny channel in the sinoatrial node to lower HR without the added side effects such as lowering blood pressure, fatigue, or edema that can accompany β-blockers or calcium channel blockers.10 , 88 In previous studies on treating POTS with ivabradine, including a recent placebo-controlled crossover study,10 ivabradine has significantly lowered HR, improved quality of life, and decreased the change in norepinephrine levels from supine to standing without any clinically significant effects on blood pressure.10 , 106, 107, 108, 109, 110 However, more robust studies are needed to determine the best course of treatment in post–COVID-19 POTS.

It is also important to monitor mental health symptoms in patients with post–COVID-19 POTS given that patients with POTS already reported a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety before the COVID-19 pandemic.16 Furthermore, initial evidence shows significant psychiatric morbidity in COVID-19 survivors.34 , 111 In addition, Shouman et al39 suggested that orthostatic symptoms may be aggravated by disease-related anxiety and deconditioning in COVID-19 survivors with POTS. The authors also found the combined use of HR inhibitors (eg, β-blockers and ivabradine), rehabilitative reconditioning, and cognitive behavioral therapy effectively managed both physical and psychiatric symptoms.39 Patients should also be reassured that POTS is not fatal and does not indicate heart disease, in addition to being made aware that disease anxiety can exacerbate symptoms.39 , 112 Assessment for mental health symptoms in patients presenting with POTS symptoms after infection and the use of multidisciplinary approaches that encompass mental and physical well-being for patients with post–COVID-19 POTS is warranted.

Future directions

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, availability and accessibility to medical care for patients with POTS was severely lacking, with many patients experiencing limited access and long wait times for appointments––sometimes as long as ≥6–12 months––at autonomic clinics.6 , 36 The pandemic has already placed an increased strain on autonomic clinics and specialists, meaning more resources are urgently needed. In March 2021, the American Autonomic Society6 issued a statement arguing for more staffing and testing capacity, increased communication between autonomic specialists and other providers to improve awareness and knowledge of post–COVID-19 POTS, and multidisciplinary treatment teams that include nurses, psychologists, and physiotherapists. These improvements will be necessary to handle the increasing caseload and evolving needs of the population with post–COVID-19 POTS.

Additionally, more research and funding are needed to improve our understanding of post–COVID-19 POTS. For example, knowledge of the natural history and pathophysiology of post–COVID-19 POTS is still evolving and needs further study.6 It also remains unclear how POTS symptoms persist after SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, effective therapies for treating disease and modifying symptoms for this population are of urgent concern.31 There are also questions of whether patients with post–COVID-19 POTS are different from patients with non–COVID-19-related POTS.6

Conclusion

There has been a sharp rise in the incidence of POTS since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic because of SARS-CoV-2 being an acute viral infectious trigger. In this review, several possible pathophysiological mechanisms for post–COVID-19 POTS were discussed, ranging from POTS arising because of SARS-Co-V-2 invading the central nervous system to the production of autoantibodies that trigger sympathetic activation and POTS symptoms. As with non–COVID-19-related POTS, HR-lowering drugs coupled with lifestyle modifications have shown potential in treating orthostatic tachycardia and dysautonomia symptoms. Practitioners should also frequently screen for mental health symptoms since patients with post–COVID-19 POTS may be at higher risk of depression and anxiety. Treatment teams should be multidisciplinary to encompass a patient’s physical and mental health. Ultimately, a patient’s treatment plan should be tailored to their symptoms and will likely require a combination of pharmacotherapy and lifestyle modifications. Finally, future research is needed on this growing public health problem to adequately understand and care for patients with post–COVID-19 POTS.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: Mr Ormiston was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, United States, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States. The content of this review is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH.

Disclosures: Dr Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, United States, Bayer, Germany, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Denmark, Novartis, Switzerland, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK118278-01 and R01 HL136407), the American Heart Association, United States (SDG #15SDG2233005), and the Department of Homeland Security, United States/Federal Emergency Management Agency, United States (EMW-2016-FP-00788). Mr Ormiston and Dr Świątkiewicz have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Zadourian A., Doherty T.A., Swiatkiewicz I., Taub P.R. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: prevalence, pathophysiology, and management. Drugs. 2018;78:983–994. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0931-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karas B., Grubb B.P., Boehm K., Kip K. The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a potentially treatable cause of chronic fatigue, exercise intolerance, and cognitive impairment in adolescents. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:344–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb06760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubb B.P. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117:2814–2817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.761643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raj S.R. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Circulation. 2013;127:2336–2342. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryarly M., Phillips L.T., Fu Q., Vernino S., Levine B.D. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1207–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj S.R., Arnold A.C., Barboi A., et al. Long-COVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American Autonomic Society statement. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31:365–368. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Leon S., Wegman-Ostrosky T., Perelman C., et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Writing Committee. Gluckman T.J., Bhave N.M., Allen L.A., et al. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus decision pathway on cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 in adults: myocarditis and other myocardial involvement, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and return to play. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1717–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blitshteyn S., Whitelaw S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients. Immunol Res. 2021;69:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taub P.R., Zadourian A., Lo H.C., Ormiston C.K., Golshan S., Hsu J.C. Randomized trial of ivabradine in patients with hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:861–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein D.S. The possible association between COVID-19 and postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:508–509. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garland E.M., Celedonio J.E., Raj S.R. Postural tachycardia syndrome: beyond orthostatic intolerance. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:60. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Sullivan J.S., Lyne A., Vaughan C.J. COVID-19-induced postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome treated with ivabradine. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-243585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knuttinen M.-G., Zurcher K.S., Khurana N., et al. Imaging findings of pelvic venous insufficiency in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Phlebology. 2021;36:32–37. doi: 10.1177/0268355520947610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ormiston C.K., Padilla E., Van D.T., et al. May-Thurner syndrome in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a case series. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022;6:ytac161. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson J.W., Lambert E.A., Sari C.I., et al. Cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety sensitivity are impaired in patients with the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Front Physiol. 2014;5:230. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald C., Koshi S., Busner L., Kavi L., Newton J.L. Postural tachycardia syndrome is associated with significant symptoms and functional impairment predominantly affecting young women: a UK perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourne K.M., Chew D.S., Stiles L.E., et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is associated with significant employment and economic loss. J Intern Med. 2021;290:203–212. doi: 10.1111/joim.13245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson M., Ståhlberg M., Runold M., et al. Long-haul post-COVID-19 symptoms presenting as a variant of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Swedish experience. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyner M.J., Masuki S. POTS versus deconditioning: the same or different? Clin Auton Res. 2008;18:300–307. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H., Yu X., Liles C., et al. Autoimmune basis for postural tachycardia syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watari M., Nakane S., Mukaino A., et al. Autoimmune postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:486–492. doi: 10.1002/acn3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X., Li H., Murphy T.A., et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor autoantibodies in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunning W.T., III, Kvale H., Kramer P.M., Karabin B.L., Grubb B.P. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is associated with elevated G-protein coupled receptor autoantibodies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Linden J., Almskog L., Liliequist A., et al. Thromboembolism, hypercoagulopathy, and antiphospholipid antibodies in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a before and after study of enhanced anticoagulation. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2 doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Y.L., Leong H.N., Hsu L.Y., et al. Autonomic dysfunction in recovered severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau S.-T., Yu W.-C., Mok N.-S., Tsui P.-T., Tong W.-L., Cheng S.W.C. Tachycardia amongst subjects recovering from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Int J Cardiol. 2005;100:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moldofsky H., Patcai J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero-Sánchez C.M., Díaz-Maroto I., Fernández-Díaz E., et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020;95:e1060–e1070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ocher R.A., Padilla E., Hsu J.C., Taub P.R. Clinical and laboratory improvement in hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) after COVID-19 infection. Case Rep Cardiol. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/7809231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ståhlberg M., Reistam U., Fedorowski A., et al. Post-COVID-19 tachycardia syndrome: a distinct phenotype of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Am J Med. 2021;134:1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casey P., Ang Y., Sultan J. COVID-19-induced sarcopenia and physical deconditioning may require reassessment of surgical risk for patients with cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:8. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-02117-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kavi L. Postural tachycardia syndrome and long COVID: an update. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;72:8–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp22X718037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis H.E., Assaf G.S., McCorkell L., et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen N.W., Stiles L.E., Miglis M.G. Preparing for the long-haul: autonomic complications of COVID-19. Auton Neurosci. 2021;235 doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miglis M.G., Prieto T., Shaik R., Muppidi S., Sinn D.-I., Jaradeh S. A case report of postural tachycardia syndrome after COVID-19. Clin Auton Res. 2020;30:449–451. doi: 10.1007/s10286-020-00727-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monaghan A., Jennings G., Xue F., Byrne L., Duggan E., Romero-Ortuno R. Orthostatic intolerance in adults reporting long COVID symptoms was not associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Front Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.833650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shouman K., Vanichkachorn G., Cheshire W.P., et al. Autonomic dysfunction following COVID-19 infection: an early experience. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallukat G., Hohberger B., Wenzel K., et al. Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent long-COVID-19 symptoms. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guilmot A., Maldonado Slootjes S., Sellimi A., et al. Immune-mediated neurological syndromes in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. J Neurol. 2021;268:751–757. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10108-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu C.-M., Wong R.S.-M., Wu E.B., et al. Cardiovascular complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:140–144. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andargie T.E., Tsuji N., Seifuddin F., et al. Cell-free DNA maps COVID-19 tissue injury and risk of death and can cause tissue injury. JCI Insight. 2021;6 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.147610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puntmann V.O., Carerj M.L., Wieters I., et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennis A., Wamil M., Alberts J., et al. Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theoharides T.C. Could SARS-CoV-2 spike protein be responsible for long-COVID syndrome? Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:1850–1861. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02696-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotecha T., Knight D.S., Razvi Y., et al. Patterns of myocardial injury in recovered troponin-positive COVID-19 patients assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1866–1878. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y.-M., Shang Y.-M., Song W.-B., et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hugon J., Msika E.-F., Queneau M., Farid K., Paquet C. Long COVID: cognitive complaints (brain fog) and dysfunction of the cingulate cortex. J Neurol. 2022;269:44–46. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10655-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Z., He W., Lan Y., et al. The evidence of porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus induced nonsuppurative encephalitis as the cause of death in piglets. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2443. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khatoon F., Prasad K., Kumar V. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: available evidences and a new paradigm. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:619–630. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00895-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yachou Y., El Idrissi A., Belapasov V., Ait Benali S. Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2657–2669. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paniz-Mondolfi A., Bryce C., Grimes Z., et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020;92:699–702. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin R., Feng W., Wang T., et al. Concomitant neurological symptoms observed in a patient diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1782–1784. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zoghi A., Ramezani M., Roozbeh M., Darazam I.A., Sahraian M.A. A case of possible atypical demyelinating event of the central nervous system following COVID-19. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;44 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y.-C., Bai W.-Z., Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:552–555. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baig A.M., Khaleeq A., Ali U., Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu D., Yang X.O. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-Kuraishy H.M., Al-Gareeb A.I., Qusti S., Alshammari E.M., Gyebi G.A., Batiha G.E.-S. Covid-19-induced dysautonomia: a menace of sympathetic storm. ASN Neuro. 2021;13 doi: 10.1177/17590914211057635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toljan K. Letter to the Editor regarding the Viewpoint “Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanism”. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:1192–1194. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wichmann D., Sperhake J.-P., Lütgehetmann M., et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:268–277. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puelles V.G., Lütgehetmann M., Lindenmeyer M.T., et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:590–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanley B., Naresh K.N., Roufosse C., et al. Histopathological findings and viral tropism in UK patients with severe fatal COVID-19: a post-mortem study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e245–e253. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matschke J., Lütgehetmann M., Hagel C., et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:919–929. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meinhardt J., Radke J., Dittmayer C., et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yong S.J. Persistent brainstem dysfunction in long-COVID: a hypothesis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12:573–580. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oshima N., Kumagai H., Iigaya K., et al. Baro-excited neurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:500–506. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boldrini M., Canoll P.D., Klein R.S. How COVID-19 affects the brain. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:682–683. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dani M., Dirksen A., Taraborrelli P., et al. Autonomic dysfunction in “long COVID”: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med. 2021;21:e63–e67. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fu Q., Vangundy T.B., Galbreath M.M., et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2858–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Porzionato A., Emmi A., Barbon S., et al. Sympathetic activation: a potential link between comorbidities and COVID-19. FEBS J. 2020;287:3681–3688. doi: 10.1111/febs.15481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.González-Hermosillo J.A., Martínez-López J.P., Carrillo-Lampón S.A., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 symptoms, a potential link with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a 6-month survey in a Mexican cohort. Brain Sci. 2021;11:760. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11060760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mastitskaya S., Thompson N., Holder D. Selective vagus nerve stimulation as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of ARDS: a rationale for neuro-immunomodulation in COVID-19 disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.667036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sidhu B., Obiechina N., Rattu N., Mitra S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thijs R.D., Brignole M., Falup-Pecurariu C., et al. Recommendations for tilt table testing and other provocative cardiovascular autonomic tests in conditions that may cause transient loss of consciousness. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31:369–384. doi: 10.1007/s10286-020-00738-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheldon R.S., Grubb B.P., II, Olshansky B., et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:e41–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miglis M.G., Larsen N., Muppidi S. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia in long-COVID and other updates on recent autonomic research. Clin Auton Res. 2022;32:91–94. doi: 10.1007/s10286-022-00854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aranyó J., Bazan V., Lladós G., et al. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia in post-COVID-19 syndrome. Sci Rep. 2022;12:298. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun W., Zhang Y., Wu C., et al. Incremental prognostic value of biventricular longitudinal strain and high-sensitivity troponin I in COVID-19 patients. Echocardiography. 2021;38:1272–1281. doi: 10.1111/echo.15133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Szekely Y., Lichter Y., Taieb P., et al. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in COVID-19: a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142:342–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singer ME, Taub IB, Kaelber DC. Risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 infection in people under age 20: a population-based analysis [published online ahead of print March 21, 2022]. medRxiv. https://doi:10.1101/2021.07.23.21260998.

- 83.Fu Q., Levine B.D. Exercise and non-pharmacological treatment of POTS. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fu Q., Levine B.D. Exercise in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2015;188:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu Q., Vangundy T.B., Shibata S., Auchus R.J., Williams G.H., Levine B.D. Exercise training versus propranolol in the treatment of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Hypertension. 2011;58:167–175. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shibata S., Fu Q., Bivens T.B., Hastings J.L., Wang W., Levine B.D. Short-term exercise training improves the cardiovascular response to exercise in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Physiol. 2012;590:3495–3505. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.George S.A., Bivens T.B., Howden E.J., et al. The International POTS Registry: evaluating the efficacy of an exercise training intervention in a community setting. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miller A.J., Raj S.R. Pharmacotherapy for postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moon J., Kim D.-Y., Lee W.-J., et al. Efficacy of propranolol, bisoprolol, and pyridostigmine for postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:785–795. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gaffney F.A., Lane L.B., Pettinger W., Blomqvist C.G. Effects of long-term clonidine administration on the hemodynamic and neuroendocrine postural responses of patients with dysautonomia. Chest. 1983;83:436–438. doi: 10.1378/chest.83.2_supplement.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shibao C., Arzubiaga C., Roberts L.J., II, et al. Hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in mast cell activation disorders. Hypertension. 2005;45:385–390. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000158259.68614.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Coffin S.T., Black B.K., Biaggioni I., et al. Desmopressin acutely decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruzieh M., Dasa O., Pacenta A., Karabin B., Grubb B. Droxidopa in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e157–e161. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fortunato J.E., Shaltout H.A., Larkin M.M., Rowe P.C., Diz D.I., Koch K.L. Fludrocortisone improves nausea in children with orthostatic intolerance (OI) Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:419–423. doi: 10.1007/s10286-011-0130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sheldon R., Raj S.R., Rose M.S., et al. Fludrocortisone for the prevention of vasovagal syncope: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ross A.J., Ocon A.J., Medow M.S., Stewart J.M. A double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study of the vascular effects of midodrine in neuropathic compared with hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci. 2014;126:289–296. doi: 10.1042/CS20130222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kpaeyeh A.G., Mar P.L., Raj V., et al. Hemodynamic profiles and tolerability of modafinil in the treatment of POTS: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:738. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Okutucu S., Görenek B. Review of the 2019 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia: what is new, and what has changed? Anatol J Cardiol. 2019;22:282–286. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2019.93507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Figueroa R.A., Arnold A.C., Nwazue V.C., et al. Acute volume loading and exercise capacity in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Appl Physiol. 2014;117:663–668. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00367.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gordon V.M., Opfer-Gehrking T.L., Novak V., Low P.A. Hemodynamic and symptomatic effects of acute interventions on tilt in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2000;10:29–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02291387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Raj S.R., Black B.K., Biaggioni I., et al. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: less is more. Circulation. 2009;120:725–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Taneja I., Bruehl S., Robertson D. Effect of modafinil on acute pain: a randomized double-blind crossover study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:1425–1427. doi: 10.1177/0091270004270292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hassani M., Fathi Jouzdani A., Motarjem S., Ranjbar A., Khansari N. How COVID-19 can cause autonomic dysfunctions and postural orthostatic syndrome? A review of mechanisms and evidence. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2021;9:434–442. doi: 10.1111/ncn3.12548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kanjwal K., Jamal S., Kichloo A., Grubb B.P. New-onset postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome following coronavirus disease 2019 infection. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2020;11:4302–4304. doi: 10.19102/icrm.2020.111102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yong S.J., Liu S. Proposed subtypes of post-COVID-19 syndrome (or long-COVID) and their respective potential therapies. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32:e2315. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barzilai M., Jacob G. The effect of ivabradine on the heart rate and sympathovagal balance in postural tachycardia syndrome patients. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2015;6 doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McDonald C., Frith J., Newton J.L. Single centre experience of ivabradine in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Europace. 2011;13:427–430. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Delle Donne G., Rosés Noguer F., Till J., Salukhe T., Prasad S.K., Daubeney P.E.F. Ivabradine in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: preliminary experience in children. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18:59–63. doi: 10.1007/s40256-017-0248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruzieh M., Sirianni N., Ammari Z., et al. Ivabradine in the treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a single center experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;40:1242–1245. doi: 10.1111/pace.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Oliphant C.S., Owens R.E., Bolorunduro O.B., Jha S.K. Ivabradine: a review of labeled and off-label uses. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s40256-016-0178-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-Month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lei L.Y., Chew D.S., Sheldon R.S., Raj S.R. Evaluating and managing postural tachycardia syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86:333–344. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.18002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]