Abstract

Objective

A Phase 3 open‐label safety study (NCT02721069) evaluated long‐term safety of diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco) in patients with epilepsy and frequent seizure clusters.

Methods

Patients were 6–65 years old with diagnosed epilepsy and seizure clusters despite stable antiseizure medications. The treatment period was 12 months, with study visits at Day 30 and every 60 days thereafter, after which patients could elect to continue. Doses were based on age and weight. Seizure and treatment information was recorded in diaries. Treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), nasal irritation, and olfactory changes were recorded.

Results

Of 163 patients in the safety population, 117 (71.8%) completed the study. Duration of exposure was ≥12 months for 81.6% of patients. There was one death (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy) and one withdrawal owing to a TEAE (major depression), both considered unlikely to be related to treatment. Diazepam nasal spray was administered 4390 times for 3853 seizure clusters, with 485 clusters treated with a second dose within 24 h; 53.4% of patients had monthly average usage of one to two doses, 41.7% two to five doses, and 4.9% more than five doses. No serious TEAEs were considered to be treatment related. TEAEs possibly or probably related to treatment (n = 30) were most commonly nasal discomfort (6.1%); headache (2.5%); and dysgeusia, epistaxis, and somnolence (1.8% each). Only 13 patients (7.9%) showed nasal irritation, and there were no relevant olfactory changes. The safety profile of diazepam nasal spray was generally similar across subgroups based on age, monthly usage, concomitant benzodiazepine therapy, or seasonal allergy/rhinitis.

Significance

In this large open‐label safety study, the safety profile of diazepam nasal spray was consistent with the established profile of rectal diazepam, and the high retention rate supports effectiveness in this population. A second dose was used in only 12.6% of seizure clusters.

Keywords: acute repetitive seizure, diazepam, intranasal, rescue, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity

Key Points.

This open‐label, long‐term study of diazepam nasal spray assessed safety in 163 patients with seizures

The study recorded 4390 administered doses of diazepam nasal spray during approximately 1.5 years of drug exposure

The retention rate was 71.8%, and a second dose of diazepam nasal spray was used in treating seizure clusters across 24 h in 485 clusters

The safety profile was generally similar across age, monthly usage, concomitant benzodiazepine therapy, and seasonal allergy/rhinitis subgroups

Diazepam nasal spray provides an accessible, socially acceptable route of administration with a safety profile consistent with the profile of rectal diazepam

1. INTRODUCTION

Some patients with epilepsy may experience seizure clusters (intermittent increases of seizure activity) despite maintenance antiseizure medications. 1 These clusters represent seizure emergencies that can last up to 24 h and are associated with an increased risk of prolonged seizures and status epilepticus, 2 more frequent emergency room visits, and disruption of the patient's and care partner's daily life. 3 Treatment with portable rescue medications by nonmedical individuals in the out‐of‐hospital context may reduce the need for hospitalization and may provide a sense of empowerment and improved quality of life for patients and care partners. 4

Benzodiazepines are the foundation of current rescue therapy. 1 , 5 Rectal diazepam has been available for more than 2 decades 6 in the European Union and United States; however, it may be difficult to administer during seizures, has significant social obstacles to widespread use, 7 and has wide pharmacokinetic patient‐to‐patient variability. 8 Other approved treatments reflect regulatory differences across regions. Buccal midazolam has been approved in the European Union for a decade for pediatric patients aged 3 months to <18 years to treat prolonged, acute, convulsive seizures. 9 , 10 , 11 Two newer intranasal benzodiazepine treatments are now available in the United States 12 , 13 and are designed to overcome the drawbacks of rectal administration, with potential advantages due to absorption by the nasal mucosa and bypassing gastrointestinal tract/hepatic first‐pass effects. 14 They are more accessible during a seizure and less embarrassing than rectal administration. 7 Other formulations and routes of administration are currently under investigation.

Diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco) is indicated for acute treatment of intermittent, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity (i.e., seizure clusters, acute repetitive seizures) that are distinct from a patient's usual seizure pattern in patients with epilepsy 6 years of age and older. 12 The formulation contains n‐dodecyl‐beta‐D‐maltoside (Intravail A3), a nonionic surfactant and absorption enhancement agent that promotes the transmucosal bioavailability of drugs. 15 The purpose of the present Phase 3 safety study was to evaluate the long‐term safety of repeated doses of diazepam nasal spray as rescue therapy in patients with epilepsy who have frequent seizure clusters (i.e., a real‐world‐use study).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

This was a Phase 3, open‐label, repeat‐dose safety study with patients from 21 centers in the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02721069). The study protocol, informed consent form, and other relevant study documentation were approved by ethics committees or institutional review boards at each site before study initiation. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles originating from the Declaration of Helsinki and consistent with good clinical practice and applicable regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was provided by patients or parents/guardians before study participation.

The study consisted of a 21‐day screening phase, baseline assessment period, and 12‐month treatment period with study visits at Day 30 and every 60 days thereafter, after which patients could elect to continue therapy at the discretion of the investigator and with approval of the sponsor. Telephone contact occurred 28 days after study termination to follow up on treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and concomitant medication use.

Diazepam nasal spray doses administered were based on the patient's age and body weight (Table 1). Patients and care partners were trained on the use of the nasal sprayer and were instructed to administer a second dose 4–12 h later if needed (≥4 h per current labeling 12 ) and to allow 5 days before repeating the dose. Investigators could adjust the dose for effectiveness (if there were no safety concerns) or safety if needed. A patient diary was used to record seizure timing and drug administration. Specific seizure types triggering use of diazepam nasal spray were not recorded by patients or caregivers during the seizure emergency.

TABLE 1.

Dosing

| Age range | Dose a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg | 10 mg | 15 mg | 20 mg | |

| Age = 6–11 years | ||||

| Weight, kg | 10–18 | 19–37 | 38–55 | 56–74 |

| Age ≥ 12 years | ||||

| Weight, kg | 14–27 | 28–50 | 51–75 | ≥76 |

The 5‐ and 10‐mg dosage strengths were administered in one spray; 15 and 20 mg were administered in two sprays. This dosing schedule is also reflected in the current labeling. 12

2.2. Patients

Inclusion criteria were as follows: male or female patients aged 6–65 years with a diagnosis of partial or generalized epilepsy with motor seizures or seizures with a clear alteration of awareness; occurrence of seizures despite a stable antiseizure medication regimen that, in the opinion of the investigator, might have needed benzodiazepine intervention for seizure control at least, on average, once every other month (i.e., six times per year); participation of a qualified care partner or medical professional who could administer study medication in the event of a seizure; if female and of childbearing potential, use of an approved method of birth control; no clinically significant abnormal findings on medical history, physical examination, or electrocardiogram (QT interval, using Fridericia's correction formula, <450 ms for male patients and <470 ms for female patients); and agreement to comply with study procedures.

History of status epilepticus was permitted. There was no restriction on concomitant use of benzodiazepines (e.g., clobazam), including use as maintenance therapy. Patients with a history of seasonal allergies or rhinitis were not excluded.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: significant injury, major surgery, or open biopsy within 30 days of screening; participation in another interventional study (excluding DIAZ.001.04); positive serum pregnancy test; positive blood screen for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody, alcohol, or drugs of abuse (medical use of marijuana was permitted) during screening; active major depression, a past suicide attempt, or suicidal ideation; a history of allergy/adverse response to diazepam; or a history of a clinically significant medical condition that would jeopardize the safety of the patient.

2.3. Safety

Incidence and seriousness of TEAEs were collected at the time of onset or exacerbation, and their possible relationship to therapy was assessed, physical/neurological examination results were collected, and TEAEs were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 20.1. Other safety and tolerability assessments included nasal irritation, which was measured objectively by a trained observer on a 6‐point scale, ranging from "No sign of nasal irritation or mucosal erosion" to "Septal perforation" (Table S1). 16 Olfactory changes were measured using the NIH Toolbox Odor Identification Test. 17

2.4. Effectiveness and tolerance

The study was open label, in a setting similar to the real world, with concomitant benzodiazepine use permitted; it therefore did not include efficacy endpoints but did allow exploratory analysis of effectiveness and benzodiazepine tolerance. The proportion of seizure clusters during which a second dose of diazepam nasal spray was given within a 24‐h period after the initial seizure was an exploratory, proxy measure for effectiveness. Two markers were explored as a potential signal of benzodiazepine tolerance: (1) the use of second doses of diazepam nasal spray within 24 h in patients on concomitant benzodiazepines, and (2) the need for a second dose in those using diazepam nasal spray on a more frequent basis.

2.5. Data analysis

Safety data were summarized. Descriptive statistics were calculated for actual values, change from baseline values for vital signs, and change from screening for clinical laboratory tests. Subgroup analyses included comparisons based on patient age (6–11 and 12–65 years); those taking or not taking concomitant benzodiazepines; those with and without seasonal allergies; and between those whose mean monthly usage of diazepam nasal spray was one to two doses per month, two to five doses per month, and more than five doses per month.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Disposition

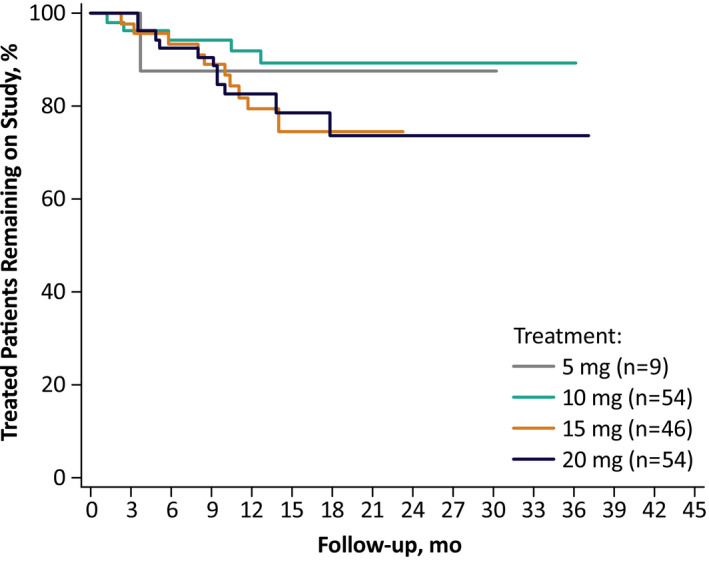

The study was conducted from April 11, 2016 to July 23, 2020 (last patient completed, final data), and 175 patients were enrolled. Twelve patients discontinued before dosing; therefore, the safety population consisted of 163 patients who received at least one dose of diazepam nasal spray (Table 2). In this safety population, 19 (10.9%) patients withdrew voluntarily, and 11 (6.3%) were lost to follow‐up. There was one death, due to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, and one patient withdrew owing to a TEAE of major depression; both of these were considered unlikely to be related to treatment. Fourteen (8.0%) patients withdrew for other reasons: seven for study closure, three for lack of compliance/noncompliance, two for transferred locations/moved, one required substantial amount of study drug, and one for lack of effectiveness. One hundred seventeen patients completed the study, for an overall retention rate of 71.8% (117/163; Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the safety population, N = 163

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | |

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.1 (15.1) |

| Median (range) | 18.0 (6–65) |

| 6–11 years, n (%) | 45 (27.6) |

| ≥12 years, n (%) | 118 (72.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 74 (45.4) |

| Female | 89 (54.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 134 (82.2) |

| Black/African American | 16 (9.8) |

| Asian | 4 (2.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 5 (3.1) |

| Other | 4 (2.5) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 151.6 (24.8) a |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 60.2 (33.6) b |

| During study | |

| Exposure | |

| Mean days (SD) | 528.7 (251.7) |

| Median days (range) | 458 (56–1230) |

| <6 months, n (%) | 9 (5.5) |

| 6–<12 months, n (%) | 21 (12.9) |

| ≥12 months, n (%) | 133 (81.6) |

| Number of doses per month, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.5) |

| Range | 1–10 |

| Number of doses per patient, mean (SD) | 26.9 (42.5) |

| Range | 1–356 |

| Doses administered, total | 4390 |

| Seizure clusters treated | 3853 |

| Concomitant benzodiazepine use during study, n (%) | |

| Yes | 125 (76.7) |

| No | 38 (23.3) |

| Presence of seasonal allergies/rhinitis, n (%) | |

| Yes | 70 (42.9) |

| No | 93 (57.1) |

n = 159.

n = 162.

FIGURE 1.

Patients remaining on study over time

3.2. Exposure

The mean duration for patients on study was 17.4 months (minimum, 1.8; maximum, 40.4) and the majority of patients (133, 81.6%) had a duration of exposure of ≥12 months (Table 2). There were a total of 3853 seizure clusters treated with 4390 doses of diazepam nasal spray. Dosing errors, including partial dose (n = 22, e.g., use of a single spray for the 15‐ and 20‐mg multispray doses); improper dosing time (n = 15); and mechanical error due to device malfunction, administration error, and other/unknown (n = 5), were reported in 42 doses, yielding a rate of correct dosing of 99.0%. There were 87 (53.4%) patients who used diazepam nasal spray one to two times per month, 68 (41.7%) patients who used it two to five times per month, and eight (4.9%) who used it more than five times per month. Throughout the study, the mean number of doses per patient was 26.9, with a median of 14.0 and with a range of 1–356. Eighty‐six (52.8%) patients used an average of two or more doses per month. During the study, 16 patients had their dose adjusted to the next higher dose (i.e., additional 5 mg to prior dose), two were adjusted up two dose levels (i.e., 10 mg added to prior dose), and one dose was reduced to the next lower level (i.e., decreased 5 mg from prior dose).

3.3. Safety

Across the duration of the study, TEAEs irrespective of relationship to study drug were reported for 82.2% of patients. Other than seizure, the most common were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection (12.3% each) and pyrexia (10.4%; Table 3). Somnolence occurred in 11 patients (6.7%) overall (10 mild, one moderate), and three (1.8%) were considered treatment related. Serious TEAEs that occurred in two or more patients were seizure, 24 patients (14.7%); status epilepticus and pneumonia, seven patients (4.3%) each; epilepsy, five patients (3.1%); and seizure cluster, pancreatitis, vomiting, pyrexia, aspiration pneumonia, anxiety, and scoliosis in two patients (1.2%) each. One patient discontinued owing to a TEAE of major depression, which was not deemed treatment related. There was one death, due to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, considered unlikely to be related to treatment. There were no serious TEAEs that were considered to be related to diazepam nasal spray. Thirty patients had TEAEs considered to be possibly or probably related to treatment with diazepam nasal spray, with nasal discomfort (6.1%); headache (2.5%); and dysgeusia, epistaxis, and somnolence (1.8% each) being the most common (Table 3). Nasal discomfort occurred in 10 patients overall; all were considered treatment related (eight were mild, two were moderate). Headache occurred in seven patients overall (four were rated mild in severity and three moderate); four were considered treatment related. Dysgeusia occurred in three patients overall (two were mild, one moderate); all were considered treatment related. Epistaxis occurred in four patients overall (three were mild, one moderate), of which three were considered treatment related.

TABLE 3.

TEAEs, N = 163

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients with TEAEs | 134 (82.2) |

| Patients with serious TEAEs | 50 (30.7) |

| Death | 1 (.6) |

| Important medical events | 10 (6.1) |

| Required/prolonged hospitalization | 44 (27.0) |

| Most common TEAEs, occurring in >5% of patients | |

| Seizure | 31 (19.0) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 20 (12.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 20 (12.3) |

| Pyrexia | 17 (10.4) |

| Influenza | 13 (8.0) |

| Pneumonia | 12 (7.4) |

| Somnolence | 11 (6.7) |

| Urinary tract infection | 11 (6.7) |

| Nasal discomfort | 10 (6.1) |

| Diarrhea | 9 (5.5) |

| Vomiting | 9 (5.5) |

| Patients with related a TEAEs, occurring in >2 patients | 30 (18.4) |

| Nasal discomfort | 10 (6.1) |

| Headache | 4 (2.5) |

| Dysgeusia | 3 (1.8) |

| Epistaxis | 3 (1.8) |

| Somnolence | 3 (1.8) |

| Cough | 2 (1.2) |

| Eye irritation | 2 (1.2) |

| Fatigue | 2 (1.2) |

| Lacrimation increased | 2 (1.2) |

| Migraine | 2 (1.2) |

| Rhinalgia | 2 (1.2) |

| Rhinorrhea | 2 (1.2) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Classified as possibly or probably related to treatment.

3.4. Other safety and tolerability measures

No clinically relevant changes were observed in laboratory measures and vital signs, including blood pressure and respiration rate. The nasal irritation test, assessed by a trained observer, showed that most patients experienced no sign of nasal irritation as shown by 764 of the 781 assessments throughout the study, and the few cases of irritation were transient. At baseline, four patients (2.5%) had Grade 1A nasal irritation (Table S1 shows details of grading). From Day 30 to Day 365, there were a total of 13 patients with any degree of nasal irritation (Grade 1A or 1B). At each time point, 0–3 patients (0%–1.8%) had nasal irritation. The majority of the 13 observations of irritation were Grade 1A, with only three patients with Grade 1B. Grade 1B irritation was recorded for one patient on Days 150, 270, and 330. There were no significant olfactory changes as measured by the NIH Toolbox Odor Identification Test (data not shown).

3.5. Subgroup safety analyses

Pediatric patients 6–11 years of age (n = 45) had a somewhat higher rate of TEAEs (91.1%) than patients 12–65 years of age (78.8% of the 118 patients in this age group) and a somewhat lower rate of diazepam nasal spray‐related TEAEs (6.7% and 22.9%, respectively; Table 4). In the concomitant benzodiazepine analysis, patients taking concomitant benzodiazepines had generally similar rates of TEAEs (107/125 patients, 85.6%) compared with the smaller group of patients who were not taking concomitant benzodiazepines (27/38, 71.1%). The concomitant benzodiazepine group experienced a numerically greater proportion of TEAEs considered to be diazepam nasal spray‐related (20.8% vs. 10.5%). In the seasonal allergies/rhinitis analysis, patients without seasonal allergies experienced TEAEs (74/93 patients, 79.6%) at a similar frequency as those who had seasonal allergies (60/70, 85.7%). Diazepam nasal spray–related TEAEs were 16.1% for patients without allergies and 21.4% for those with allergies. In the analysis based on mean monthly usage, the proportion of patients with TEAEs was 78.2% in patients using one to two doses per month (68/87 patients), 85.3% in those receiving two to five doses per month (58/68), and 100% in the few receiving more than five doses per month (8/8). Patients with higher monthly use of diazepam nasal spray experienced a numerically higher proportion of TEAEs considered to be treatment related (11.5%, 25.0%, and 37.5%, respectively).

TABLE 4.

Summary and subgroup comparisons of TEAEs

| Subgroup | TEAEs, n (%) | Serious TEAEs, n (%) | Drug‐related TEAEs, n (%) a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| 6–11 years, n = 45 | 41 (91.1) | 18 (40.0) | 3 (6.7) |

| ≥12 years, n = 118 | 93 (78.8) | 32 (27.1) | 27 (22.9) |

| Concomitant benzodiazepine use | |||

| Yes, n = 125 | 107 (85.6) | 42 (33.6) | 26 (20.8) |

| No, n = 38 | 27 (71.1) | 8 (21.1) | 4 (10.5) |

| Seasonal allergies/rhinitis | |||

| Yes, n = 70 | 60 (85.7) | 26 (37.1) | 15 (21.4) |

| No, n = 93 | 74 (79.6) | 24 (25.8) | 15 (16.1) |

| Monthly dosing frequency, mean | |||

| 1–2, n = 87 | 68 (78.2) | 26 (29.9) | 10 (11.5) |

| >2–5, n = 68 | 58 (85.3) | 21 (30.9) | 17 (25.0) |

| >5, n = 8 | 8 (100.0) | 3 (37.5) | 3 (37.5) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Possibly or probably related to treatment.

3.6. Effectiveness and tolerance

An exploratory investigation of how many times a second dose of diazepam nasal spray was used across 24 h was performed as a proxy for effectiveness. Diazepam nasal spray was administered 4390 times for 3853 seizure clusters, with a second dose used for 485 seizure clusters (12.6%). Note that 52 doses were recorded in the diaries that were not reported as first or second doses in 24 h; diaries did not necessarily specify whether those doses were used to treat additional seizures or whether there were other reasons for administration. Among the 485 seizure clusters treated with a second dose within a 24‐h period after the initial dose, the second dose was taken 0–4 h later in 152 (31.3%) clusters, 0–6 h later in a cumulative 224 (46.2%) clusters, and 0–12 h later in a cumulative 318 (65.6%) clusters.

No clinically relevant difference in second doses was demonstrated for patients with higher monthly usage of diazepam nasal spray, nor for those on concomitant benzodiazepines. For those patients receiving two to five doses of diazepam nasal spray per month, 231 of 2387 (9.7%) seizure clusters were treated with a second dose in 24 h. For those patients using concomitant benzodiazepines, 426 of 3399 (12.5%) seizure clusters were treated with a second dose.

4. DISCUSSION

This was an open‐label, long‐term safety study in 163 patients with epilepsy who had seizure clusters despite stable antiseizure medications, and it represents one of the largest studies to date of patients with seizure clusters. The safety profile of diazepam nasal spray was consistent with the established safety profile of rectal diazepam. Exposure was ≥1 year in 81.6% of patients. Treatment‐related TEAEs were only reported in 18.4% of patients. Nasal irritation was generally mild and transient, and there were no clinically relevant olfactory changes. The retention rate of 71.8% over a mean exposure of 17.4 months supports the effectiveness of the nasal spray in this population with multiple complex seizure types.

Notably, this study also recorded the largest number of total doses of study drug administered in a study of seizure cluster rescue treatment (n = 4390) and a mean usage of 2.3 doses per month for each patient. This compares to 1578 seizure treatments that occurred in 149 patients, 4 and 56 seizure clusters in 56 patients 18 observed in diazepam rectal gel studies. The present study included 45 children aged 6–11 years, those with concomitant benzodiazepines, those with seasonal allergies, and those with prior status epilepticus, suggesting that these results may be applicable to a broad patient population. Only one patient withdrew from the study owing to a TEAE (depression); neither this nor the single sudden unexpected death in epilepsy was deemed to be related to treatment. In the small proportion of TEAEs considered to be related to diazepam nasal spray, the most common were nasal discomfort (6.1%) and headache (2.5%), and no serious TEAEs were considered to be related to treatment. Assessments showed no greater amounts of nasal irritation during the study than at baseline.

In this population of patients with intractable epilepsy and seizure clusters, the overall rate of somnolence (6.7%) was substantially lower than previously reported in a Phase 1 study of diazepam nasal spray in healthy adults not taking concomitant medications (56.6%). 19 Although this difference has not been investigated, the study settings (long‐term treatment in the community vs. a single‐dose crossover in‐clinic study) and populations differed. Notably, 97.8% of incidents of somnolence in the healthy volunteer study, irrespective of relationship to study drug, were judged to be mild (data on file). Reports of somnolence from patients and caregivers are individually subjective and can be affected by patient‐related factors in real‐world populations that are familiar from postictal somnolence and the sedating effects of other rescue or maintenance therapies.

Cardiorespiratory events, which have been associated with high‐dose intravenous benzodiazepines, 20 were not observed. The substantial duration and extent of exposure to diazepam nasal spray in this study reinforce the generalizability of these results to real‐world use.

Three concentrations of diazepam nasal spray (5, 7.5, and 10 mg in .1 ml) and four doses (5, 10, 15, and 20 mg) allow for patient‐specific dosing based on age and weight. 12 The formulation also contains vitamin E to enhance the nonaqueous solubility of diazepam 21 without the toxicities that have been observed with organic solvents. 22 This vitamin E acetate is not heated, so it does not produce the toxic ketene that has been associated with vaping. 23 The large droplet size of diazepam nasal spray (>10 μm) means that absorption occurs through the nasal mucosa and that pulmonary deposition is unlikely. 24 , 25

In a study in 48 healthy adults, diazepam nasal spray provided a rapid and noninvasive route of administration and had comparable bioavailability and less variability versus rectal diazepam administration. 19 In an open‐label study of 57 patients with epilepsy, a single dose of diazepam nasal spray showed rapid diazepam absorption with similar exposure in ictal/peri‐ictal and interictal conditions, and its overall pharmacokinetic profile was similar to that seen in healthy adults. 26 The safety profile seen in this study was generally consistent with that for rectal diazepam in prior studies. 4 , 19 , 26 , 27

The present results support the use of diazepam nasal spray in a wide range of subgroups with seizure clusters. Findings were generally similar across age groups, with somewhat fewer TEAEs in adolescents and adults and fewer diazepam nasal spray–related TEAEs recorded in children than in those 12 years or older (6.7% and 22.9%, respectively). Higher rates of TEAEs and diazepam nasal spray‐related TEAEs were seen in patients receiving concomitant benzodiazepines, which is consistent with interim data, 28 and in patients with higher monthly usage of diazepam nasal spray. These results might reflect a mismatch between the subgroups or reflect increased exposure to benzodiazepines (of note, although serious TEAEs were higher in these subgroups, no serious TEAEs were considered to be related to treatment), or greater usage could be a marker of epilepsy severity. The seasonal allergy/rhinitis group analysis, in a patient population with a mean treatment duration spanning the seasons across >1 year, showed similar rates of diazepam nasal spray‐related TEAEs (consistent with an interim analysis 29 ), suggesting that there were no safety signals related to seasonal allergies/rhinitis. Overall, the safety and tolerability results were as expected from previous studies of diazepam nasal spray, including lack of change in blood pressure and respiratory rate, with no findings of respiratory depression. 16 , 19 , 26

Seizure clusters may last 24 h or more, as shown by a study of seizure diaries in which 58.5% of 1177 patients with seizure clusters had a seizure 6–24 h after the initial seizure in a cluster. 30 , 31 Therefore, the ideal rescue treatment would provide single‐dose effectiveness across a full day. In the present study, 163 patients experienced 3853 seizure clusters, of which 485 (12.6%) were treated with a second dose of medication in 24 h. The low rate of using a second dose, even in the patients receiving concomitant benzodiazepines or receiving diazepam nasal spray more than two times per month, suggests that tolerance does not appear to be a concern and reaffirms interim findings. 32 Based on the results of this study and findings of high bioavailability of a proven agent using a new route of administration, 14 diazepam nasal spray provides a welcome new therapeutic option for the treatment of seizure clusters, joining other products/formulations approved in various jurisdictions and treatment populations. 9 , 13 , 33

Although rectal diazepam has been commonly used in the outpatient context and has a well‐established efficacy and safety profile, 8 , 34 the less‐intrusive intranasal method of diazepam administration offers a clear advantage for patients and their care partners, and this diazepam nasal spray formulation has comparable pharmacokinetic properties and a safety profile consistent with the rectal formulation. 19 , 26 , 35 With rectally administered diazepam in a long‐term study (N = 149), 1215 out of a total of 1578 seizures (77.0%) were controlled across 12 h 4 ; in our study (N = 163), 4390 doses of diazepam nasal spray were administered, and second doses were used for only 12.6% of seizure clusters across 24 h. Patients with status epilepticus were excluded from the rectally administered study, but those with prior status epilepticus were allowed in the present study. Study designs were similar between the two studies (open‐label, out‐of‐clinic dosing, included adults and children with seizure clusters, and permitted concomitant benzodiazepines) and included the same proportion of adult patients (52%); differences include a lower age limit (2–5 years permitted) in the rectally administered study, variations in treatment protocol, probable differing baseline antiseizure medications given when the studies were performed, and potential differences in epilepsy severity or etiology. Specific seizure types treated were not recorded in either study. Both studies evaluated safety and tolerability and had similar evaluations of the use of a second dose, with the rectal diazepam study designating seizure control at 12 h as the efficacy endpoint and the present study measuring use of a second dose within 24 h as a measure of effectiveness. Although results cannot be compared directly and no studies have directly compared diazepam nasal spray with other therapies for seizure clusters or similar indications, they suggest the effectiveness of the initial dose of diazepam for seizure clusters in these two long‐term, real‐world‐like studies.

There are limitations associated with the design and interpretation of this study. This was an open‐label safety study; therefore, there was no control or comparator group. The absence of a control population makes it difficult to determine the degree to which TEAEs are related to treatment or other factors and how they might have differed from those associated with other agents. In addition, as a safety study, it was not powered to test statistical differences. The relatively small size of some subgroups (e.g., patients using >5 doses/month [n = 8]) limits conclusions about these subgroups. Interpretation of retention is somewhat challenging, and comparing this study to other studies may be difficult owing to different patient populations and different seizure types, which were not recorded in the present study during the seizure emergencies. However, diazepam nasal spray contains the proven agent diazepam, and the reference formulation (diazepam rectal gel) was shown in randomized, placebo‐controlled studies to treat seizure clusters. 4 , 18 , 27 The nasal spray formulation has shown comparable bioavailability and lower intrapatient variability compared with rectal diazepam. 19 These and other clinical findings permitted diazepam nasal spray to utilize an approval pathway that did not require use of a control.

5. CONCLUSION

In this large open‐label safety study of 163 treated patients who were administered 4390 doses, the safety profile of diazepam nasal spray was comparable to the reported profile of rectal diazepam. The safety profile of diazepam nasal spray was generally similar across subgroups based on age, monthly usage of diazepam nasal spray, concomitant benzodiazepine therapy, and seasonal allergy/rhinitis, speaking to the broad applicability of the findings. In addition, the retention rate of 71.8% across a mean of approximately 1.5 years and usage of a second dose in the 24 h after the initial dose in only 485 clusters is suggestive that diazepam nasal spray is effective in treating seizure clusters.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J.W.W. has served as an advisor or consultant for CombiMatrix, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Neurelis, NeuroPace, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, and Upsher‐Smith Laboratories; has served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Cyberonics, Eisai, Lundbeck, Mallinckrodt, Neurelis, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, and Upsher‐Smith Laboratories; and has received grants for clinical research from Acorda Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Insys Therapeutics, Lundbeck, Mallinckrodt, Neurelis, NeuroPace, Upsher‐Smith Laboratories, and Zogenix. I.M. is an employee of Marinus Pharmaceuticals and has served as a consultant/advisor and/or speaker for GW Pharmaceuticals, Insys Therapeutics, Neurelis, NeuroPace, and Visualase and as a study investigator for GW Pharmaceuticals. R.E.H. has received research support from UCB Pharmaceuticals, Neurelis, and Biogen, and is an advisor for Neurelis. D.D. receives salary support from the NIH, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health, Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and Epilepsy Study Consortium; is an investigator on research grants awarded to CHOP from Zogenix, Greenwich Biosciences, UCB, Brain Sentinel, Neurelis, Q‐State, USL, Aquestive, Bio‐Pharm, Insys, SK Life Science, and Encoded Therapeutics; has received travel expenses for protocol development conferences or investigator meetings from Marinus, Ovid/Takeda, Ultragenyx, USL, Pfizer, and Zogenix; and has received honoraria and/or travel support for continuing medical education and other educational programs from Wake Forest University School of Medicine, American Epilepsy Society, American Academy of Neurology, Epilepsy Foundation of America, Epilepsy Foundation of North Carolina, Medscape, Miller Medical Communications, Ecuador Neurology Project, Ministry of Health of the United Arab Emirates, and Seoul National University. M.R.S. has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Medtronic and is an advisor for Neurelis and has received research support from Eisai, Medtronic, Neurelis, Pfizer, SK Life Science, Takeda, Sunovion, UCB Pharma, and Upsher‐Smith. K.L. has received research support from Intracellular Therapies, SK Life Science, Genentech, Biotie Therapies, Monosol, Aquestive Therapeutics, Engage Therapeutics, Xenon, Lundbeck, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Sunovion, Acorda, Eisai, UCB, Livanova, Axsome, and Acadia. B.V. is an advisor for Neurelis. E.B.S. has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Eisai, Lundbeck, Nutricia, Novartis, Greenwich, Epitel, Encoded Therapeutics, and Qbiomed and is an advisor for Neurelis. D.T. has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Avexis, Marinus, and Neurelis. J.D. has received research funding from the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles, Neurelis, Novartis, Ovid, Aquestive, and UCB. A.L.R. is an employee of and has received stock options from Neurelis. E.C. is an employee of and has received stock and stock options from Neurelis. None of the other authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Table S1‐S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided at the direction of the authors by Robin Smith, PhD, of the Curry Rockefeller Group (Tarrytown, NY), which also provided additional editorial assistance including formatting and proofreading. This support was funded by Neurelis (San Diego, CA).

Wheless JW, Miller I, Hogan RE, Dlugos D, Biton V, Cascino GD, et al; for the DIAZ.001.05 Study Group . Final results from a Phase 3, long‐term, open‐label, repeat‐dose safety study of diazepam nasal spray for seizure clusters in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2021;62:2485–2495. 10.1111/epi.17041

Funding information

This study was funded by Neurelis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Penovich PE, Buelow J, Steinberg K, Sirven J, Wheless J. Burden of seizure clusters on patients with epilepsy and caregivers: survey of patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. Neurologist. 2017;22(6):207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haut SR, Shinnar S, Moshe SL, O'Dell C, Legatt AD. The association between seizure clustering and convulsive status epilepticus in patients with intractable complex partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1999;40(12):1832–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Komaragiri A, Detyniecki K, Hirsch LJ. Seizure clusters: a common, understudied and undertreated phenomenon in refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;59:83–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell WG, Conry JA, Crumrine PK, Kriel RL, Cereghino JJ, Groves L, et al. An open‐label study of repeated use of diazepam rectal gel (Diastat) for episodes of acute breakthrough seizures and clusters: safety, efficacy, and tolerance. North American Diastat Group. Epilepsia. 1999;40(11):1610–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jafarpour S, Hirsch LJ, Gainza‐Lein M, Kellinghaus C, Detyniecki K. Seizure cluster: definition, prevalence, consequences, and management. Seizure. 2019;68:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fitzgerald BJ, Okos AJ, Miller JW. Treatment of out‐of‐hospital status epilepticus with diazepam rectal gel. Seizure. 2003;12(1):52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kapoor M, Cloyd JC, Siegel RA. A review of intranasal formulations for the treatment of seizure emergencies. J Control Release. 2016;237:147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garnett WR, Barr WH, Edinboro LE, Karnes HT, Mesa M, Wannarka GL. Diazepam autoinjector intramuscular delivery system versus diazepam rectal gel: a pharmacokinetic comparison. Epilepsy Res. 2011;93(1):11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shire Pharmaceuticals . Buccolam: summary of product characteristics. [cited 2021 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product‐information/buccolam‐epar‐product‐information_en.pdf

- 10. Scott RC, Besag FM, Neville BG. Buccal midazolam and rectal diazepam for treatment of prolonged seizures in childhood and adolescence: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9153):623–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McIntyre J, Robertson S, Norris E, Appleton R, Whitehouse WP, Phillips B, et al. Safety and efficacy of buccal midazolam versus rectal diazepam for emergency treatment of seizures in children: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neurelis . Valtoco (diazepam nasal spray). Full prescribing information. San Diego, CA: Neurelis; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13. UCB . NAYZILAM® (midazolam nasal spray). Full prescribing information. Smyrna, GA: UCB; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cloyd J, Haut S, Carrazana E, Rabinowicz AL. Overcoming the challenges of developing an intranasal diazepam rescue therapy for the treatment of seizure clusters. Epilepsia. 2021;62:846–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maggio ET, Pillion DJ. High efficiency intranasal drug delivery using Intravail® alkylsaccharide absorption enhancers. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2013;3(1):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal SK, Kriel RL, Brundage RC, Ivaturi VD, Cloyd JC. A pilot study assessing the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of diazepam after intranasal and intravenous administration in healthy volunteers. Epilepsy Res. 2013;105(3):362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dalton P, Doty RL, Murphy C, Frank R, Hoffman HJ, Maute C, et al. Olfactory assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80(11 Suppl 3):S32–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cereghino JJ, Mitchell WG, Murphy J, Kriel RL, Rosenfeld WE, Trevathan E. Treating repetitive seizures with a rectal diazepam formulation: a randomized study. The North American Diastat Study Group. Neurology. 1998;51(5):1274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hogan RE, Gidal BE, Koplowitz B, Koplowitz LP, Lowenthal RE, Carrazana E. Bioavailability and safety of diazepam intranasal solution compared to oral and rectal diazepam in healthy volunteers. Epilepsia. 2020;61(3):455–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lacroix L, Fluss J, Gervaix A, Korff CM. Benzodiazepines in the acute management of seizures with autonomic manifestations: anticipate complications! Epilepsia. 2011;52(10):e156–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Azzi A, Ricciarelli R, Zingg JM. Non‐antioxidant molecular functions of alpha‐tocopherol (vitamin E). FEBS Lett. 2002;519(1–3):8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sperling MR, Haas KF, Krauss G, Seif Eddeine H, Henney HR 3rd, Rabinowicz AL, et al. Dosing feasibility and tolerability of intranasal diazepam in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(10):1544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu D, O'Shea DF. Potential for release of pulmonary toxic ketene from vaping pyrolysis of vitamin E acetate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(12):6349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) . Guidance for industry: bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for nasal aerosols and nasal sprays for local action. Rockville, MD: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) . Guidance for industry: nasal spray and inhalation solution, suspension, and spray drug products—chemistry, manufacturing, and controls documentation. Rockville, MD: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hogan RE, Tarquinio D, Sperling MR, Klein P, Miller I, Segal EB, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of VALTOCO (NRL‐1; diazepam nasal spray) in patients with epilepsy during seizure (ictal/peri‐ictal) and nonseizure (interictal) conditions: a phase 1, open‐label study. Epilepsia. 2020;61(5):935–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dreifuss FE, Rosman NP, Cloyd JC, Pellock JM, Kuzniecky RI, Lo WD, et al. A comparison of rectal diazepam gel and placebo for acute repetitive seizures. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(26):1869–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Segal EB, Tarquinio D, Miller I, Wheless JW, Dlugos D, Biton V, et al. Evaluation of diazepam nasal spray in patients with epilepsy concomitantly using maintenance benzodiazepines: an interim subgroup analysis from a phase 3, long‐term, open‐label safety study. Epilepsia. 2021;62(6):1442–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vazquez B, Wheless J, Desai J, Rabinowicz AL, Carrazana E. Lack of observed impact of history or concomitant treatment of seasonal allergies or rhinitis on repeated doses of diazepam nasal spray administered per seizure episode in a day, safety, and tolerability: interim results from a phase 3, open‐label, 12‐month repeat‐dose safety study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Symphony Health Integrated DataVerse®. [cited 2021 Aug 17]. Available from: https://symphonyhealth.com/what‐we‐do/view‐health‐data

- 31. Fisher RS, Bartfeld E, Cramer JA. Use of an online epilepsy diary to characterize repetitive seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;47:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cascino GD, Tarquinio D, Wheless JW, Hogan RE, Sperling MR, Liow K, et al. Lack of observed tolerance to diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco®) after long‐term rescue therapy in patients with epilepsy: interim results from a phase 3, open‐label, repeat‐dose safety study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;120:107983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bausch Health US . Diastat ® C‐IV (diazepam rectal gel). Full prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ: Bausch Health US; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maglalang PD, Rautiola D, Siegel RA, Fine JM, Hanson LR, Coles LD, et al. Rescue therapies for seizure emergencies: new modes of administration. Epilepsia. 2018;59(Suppl 2):207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanimoto S, Pesco Koplowitz L, Lowenthal RE, Koplowitz B, Rabinowicz AL, Carrazana E. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of diazepam after intranasal administration of NRL‐1 to healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2020;9(6):719–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐S2