Abstract

Aims and objectives

To explore the perspectives of people with dementia on being cared for by others, on the future and on the end of life, and to evaluate the capability and willingness of participants to have these conversations.

Background

Awareness about perspectives of people with dementia should decrease stigmatisation and improve their quality of life. Applying palliative care principles from an early stage is important to address diverse needs and to anticipate the future. Few studies investigate perspectives of people with dementia regarding palliative care, including advance care planning.

Design

Qualitative descriptive design.

Methods

We performed in‐depth interviews with 18 community‐dwelling persons with dementia in South‐Limburg, the Netherlands. Transcripts were analysed using an inductive content analysis. Two authors coded the data and regularly compared coding. All authors discussed abstraction into categories and themes. We followed the COREQ reporting guidelines.

Results

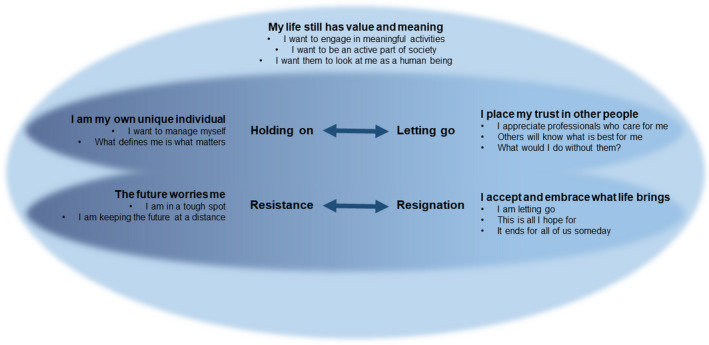

Five overarching themes derived from the interviews were as follows: (a) My life still has value and meaning, (b) I am my own unique individual, (c) I place my trust in other people, (d) The future worries me, and (e) I accept and embrace what life brings.

Conclusions

Participants' thoughts about the future and the end of life involved feelings of ambiguity and anxiety, but also of contentment and resignation. Despite worrying thoughts of decline, participants primarily demonstrated resilience and acceptance. They expressed appreciation and trust towards those who care for them. They wished to be recognised as unique and worthy humans, until the end of life.

Relevance to clinical practice

This study demonstrates capability and willingness of people with dementia to discuss the future and end‐of‐life topics. Public and professional awareness may facilitate opportunities for informal end‐of‐life discussions. Healthcare professionals should promote belongingness of persons with dementia and strive to build equal, trustful care relationships with them and their families.

Keywords: advance care planning, attitude to death, dementia, end‐of‐life care, family caregivers, nursing care, palliative care, qualitative research, quality of life

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

This paper demonstrates that people with early‐stage dementia, when given the opportunity, are capable and willing to talk about their future and to express their thoughts on the end of life.

The paper illustrates that individuals with dementia cope with their condition in different ways, which may influence how they perceive the future. Although opportunities for conversations about future care in the context of advance care planning should be offered regularly, this should be tailored to an individual's stance towards the future and readiness to discuss it.

The findings emphasise the need for an inclusive community for people with dementia, in which others facilitate them to fulfil basic human needs: to live a meaningful life and to maintain belongingness and uniqueness until the end of life.

1. INTRODUCTION

Societies may prioritise enabling the increasing number of people with dementia to ‘live well’ with their condition (WHO, 2012). People with dementia face multiple losses in their personal and social life, which disrupts their connection to others and the world around them (van Wijngaarden et al., 2019). We need societal awareness and understanding to support people with dementia and their families, to increase their quality of life and to reduce stigma (WHO, 2012). Dementia is a life‐limiting illness (Brodaty et al., 2012). Especially the moderate to advanced stages require care goals focusing on comfort and quality of life (van der Steen et al., 2014). Integrated care services are a cornerstone of high‐quality palliative care for people with dementia and should be adapted to specific needs that arise throughout the course of the disease (WHO, 2012). It is essential to study the perspectives of people with dementia themselves to optimise the quality of care provided to them, until the end of life.

2. BACKGROUND

Although the provision of palliative care particularly applies to the more advanced stages of dementia, a white paper states that ‘recognising its eventual terminal nature is the basis for anticipating future problems and an impetus to the provision of adequate palliative care’ (van der Steen et al., 2014). Therefore, an early palliative approach to care is recommended. In a palliative approach, professionals apply palliative care knowledge and principles to meet the needs of people with a life‐limiting illness, regardless of their prognosis (Sawatzky et al., 2016). Palliative care emphasises timely recognition and addressing of needs of a physical, psychosocial and spiritual or existential nature and involves care for families (van der Steen et al., 2014). Healthcare professionals such as nurses and physicians have an important role in discussing needs for future care with people with dementia and their families (Lee et al., 2017). Nonetheless, healthcare professionals may postpone or avoid end‐of‐life conversations to avert distress of persons with dementia or themselves (Poppe et al., 2013; Sinclair et al., 2016). Care staff sometimes perceive end‐of‐life topics (e.g. death) as a taboo, and they may find it uncomfortable to discuss the end of life (Livingston et al., 2012) or feel that such conversations are threatening to people with dementia (Poppe et al., 2013). Early conversations on future care in the context of advance care planning are important, as cognitive and language impairments may obstruct people with advanced dementia to make active decisions and to express their wishes (Dening et al., 2011). Palliative care knowledge and communication skills among healthcare professionals are needed to improve symptom management and to reduce burdensome treatments and avoidable hospitalisations at the end of life of people with dementia (van Riet Paap et al., 2015; van der Steen, 2010).

To offer adequate, personalised and timely palliative care, we must consider the perspectives of people with dementia on what it means to live with dementia and to be cared for by others (Hill et al., 2017). However, studies investigating perspectives on palliative care rarely include the perspectives of people with dementia themselves (Perrar et al., 2015). Although proxy ratings are an important source of information in the care for people with cognitive impairments, they cannot replace older adults' self‐report of aspects of health and well‐being (Neumann et al., 2000). Reports on experienced health differ systematically between proxies (i.e. informal or family caregivers and professional caregivers) and persons with dementia. Self‐rated quality of life of people with dementia is often higher than the ratings of proxies (Beerens et al., 2013; Bowling et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2019). This implies that people with dementia may value different aspects or have a different conceptualisation of quality of life (Griffiths et al., 2019). Another study found low to moderate agreement between people with early‐stage dementia and their families on preferences for future treatments in hypothetical end‐of‐life situations (Harrison Dening et al., 2016).

In contemporary policy, practice and research, it is acknowledged that perspectives of people with dementia cannot be omitted when investigating their care needs. A few studies have described expectations of people with dementia regarding the future and end‐of‐life care (Goodman et al., 2013; Poole et al., 2018; Read et al., 2017), their needs in early palliative care (Beernaert et al., 2016) and their perspectives on decision‐making (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013). Little research is currently available that elicits perspectives of people with early‐stage dementia on receiving palliative care, on the approaching end of life and on discussing these issues. More awareness is needed of how people with dementia feel about their future, being cared for by others and discussing their end of life to adjust care provision to match their standards. The research question of the current study is: what are the perspectives of people with early‐stage dementia on being cared for by others now and in the future and on the end of life? Simultaneously, the study explores the flow of conversations with people with dementia about the future and the end of life.

3. METHODS

This study is part of a larger project entitled DEDICATED (Desired Dementia Care Towards End of Life). The goal of DEDICATED is to develop a method for long‐term care staff, which aims to improve person‐centred palliative care for people with dementia. The current study belongs to a series of studies that investigate the needs in palliative dementia care from different perspectives. It builds on previous findings from a scoping review and a survey on the needs of nursing staff (Bolt et al., 2020; Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, Pieters, et al., 2019), a secondary data analysis (Bolt et al., 2019) and an interview study on families' experiences with end‐of‐life care (Bolt et al., 2019).

3.1. Research design

We used a qualitative descriptive design and adopted a general naturalistic inquiry approach (Sandelowski, 2000). Data collection involved individual, semi‐structured, in‐depth interviews. We followed the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ, Tong et al., 2007; see checklist in Appendix S1).

3.2. Participants and recruitment

We recruited a criterion‐based (Table 1), purposive sample of people with early‐stage dementia. We aimed for a group comprising both males and females with varying ages above 64. Care professionals who collaborate in the DEDICATED project (i.e. dementia case managers, homecare nurses, a geriatrician and a nurse practitioner in elderly care) recruited participants in the Southern Netherlands. Recruiters made a clinical judgement about participants' cognitive abilities and whether an individual would be competent to engage in an interview and to judge their own willingness to do so. In case of doubt, they approached a legal representative and asked their permission to approach the person with dementia. Recruiters verbally informed eligible participants and (if applicable) their legal representative about the study and asked consent to be contacted by the researcher. If interested, participants and (if applicable) their representative obtained an information letter and a flyer.

TABLE 1.

Eligibility criteria for participation

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Judged by healthcare professional (recruiter):

|

Judged by healthcare professional (recruiter):

|

After 1 week, the researcher phoned the participant or the legal representative. They were then given the opportunity to ask additional questions and to indicate their interest in participating. Upon agreement, the researcher scheduled an appointment. The recruiters, who knew the participants well, were asked to inform the researchers beforehand about particularities that should be taken into account during the interview (such as sensitive topics or questions that could cause distress). The Research Ethics Committee (METCZ20180085) approved this study before its start. All participants verbally agreed to be interviewed. All participants or their legal representative provided written informed consent before the start of the interview. The recruiters had judged most participants to be competent to state their willingness to engage in the interview. A few participants, who had a legal representative signing the informed consent form, gave verbal consent themselves. Participation was strictly voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw their participation at any moment, for any reason. The recruiters approached 22 individuals. Four were not willing to participate. Main reasons for refusal were being occupied with other things (e.g. recovering from a fall, reorganising the house) or legal representatives not wanting to overburden their relative. Table 2 depicts the 18 participants: 11 males and 7 females. Their mean age was 82 (SD, 9) years and ranged from 65–94. The average duration of the interviews was 53 min (SD, 19) and ranged from 31–108 min.

TABLE 2.

Interview participants

| Pseudonym | Sex | Age | Informal caregiver | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present? | (Familial) relationship | |||

| Vincent | Male | 80 | Yes | Unrelated informal caregiver |

| Leonard | Male | 81 | Yes | Partner |

| Benjamin | Male | 83 | Yes | Partner |

| Oliver | Male | 83 | Yes | Partner |

| Anna | Female | 85 | No | – |

| James | Male | 77 | Yes | Partner |

| Lucasa | Male | 86 | No | – |

| Teddyb | Male | 93 | Yes | Son |

| Thomas | Male | 93 | No | – |

| Nora | Female | 89 | Yes | Niece |

| Joseph | Male | 73 | Yes | Partner |

| Lucy | Female | 94 | Yes | Daughter |

| David | Male | 72 | No | – |

| John | Male | 65 | No | – |

| Caroline | Female | 88 | Yes | Daughter |

| Eva | Female | 87 | Yes | Daughter |

| Julia | Female | 67 | Yes | Daughter |

| Sophie | Female | 82 | Yes | Unrelated informal caregiver |

A formal caregiver (case manager) was present during this interview.

The interviewee just moved to a residential care home and had more advanced dementia.

3.3. Data collection

A topic list was used flexibly to structure the interviews (Appendix S2). It included questions about receiving care from others, the future and the end of life. It also included questions about interprofessional collaboration and transitions of care; however, these topics are not the focus of the current article. The topic list was informed by expert views (i.e. dementia case managers), relevant literature (Perrar et al., 2015; van der Steen et al., 2014) and results from our previous studies (Bolt et al., 2020; Bolt, Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, & Meijers, 2019). For instance, the experts and our previous interview study with family caregivers emphasised the need for familiarity, which led to the question ‘What do others need to know about you, to care for you properly?’ To improve the topic list, we presented it to a working group of nurses, nurse managers, dementia case managers and patient representatives. We conducted two rehearsal interviews to obtain feedback. These interviews were held with, respectively, a family caregiver and a woman with dementia. Both gave written informed consent confirming the official procedure. The latter interview was transcribed and used in the final analysis, with permission. Minor, mainly textual, adaptations were made based on comments from the working group and rehearsal interviews. For instance, we replaced some factual questions, such as ‘who cares for you at home?’ and ‘how often do they come here?’ with more general questions, such as ‘do or did you receive help from other people?’ and ‘how do you feel about that?’ Whereas the topic list remained unchanged throughout the further data collection period, experiences from previous interviews contributed to nuances in subsequent conversations (e.g. focus on specific topics, the introduction of topics, use of examples for clarification). Recruiters provided participants' demographic information including age, gender and relationship with the informal caregiver (if present) before the interview.

Interviews were held between August 2018–October 2019 and took place at the participants' own home at a time of their preference. Informal caregivers were allowed to be present in case this was preferred, though they were not actively involved in the interview. Two female researchers (SB and CK) with a background in, respectively, neuropsychology and biomedical sciences took turns leading the interviews. Both researchers were trained in qualitative interviewing as a part of their academic education and both had led in‐depth interviews before. In addition, they received a short training on interviewing people with dementia (e.g. make participants feel at ease, adapt to participant's level of understanding) from a nurse practitioner in elderly care. During each interview, the leading interviewer was accompanied by a co‐interviewer (SB, CK or another member of the research team). The accompanying member observed and sporadically asked additional questions for clarification. Before the start of each interview, the researchers used reassuring communication (‘small talk’) to establish a trustful connection with the participant. The purpose of the interview was explained in clear language, guiding the participant through the consent form before obtaining written consent. The researchers emphasised that there were no right or wrong answers and that they merely wished to learn from the perspectives of the person with dementia. Interviews were audio‐recorded with the participants' permission. The researchers closely monitored the well‐being and potential overburdening of participants during the interview by paying attention to signals of exhaustion, confusion or negative emotions. When considered appropriate, the interviewer asked whether the participant needed a break or wanted to end the conversation. The leading interviewer shortly debriefed participants and (if present) their legal representative and asked how they had experienced the conversation and how they felt about the interview topics. The researchers wrote brief field notes after the interviews regarding the atmosphere or particularities during the conversation. The scheduled duration of the interviews was 30–45 minutes.

The process of interviewing was guided by reflective bracketing (Tufford & Newman, 2012). Before initiating data collection, reflective discussions took place between the researchers, dementia care professionals and informal caregivers about the process of interviewing people with dementia and the content of the interviews. Moreover, two rehearsal interviews and the subsequent feedback promoted reflection. Reflection helped to identify pre‐existing knowledge, and it contributed to the researchers' awareness of their own role as interviewers, potential internal biases (e.g. prejudices about frail older people) and their own and others' assumptions and preconceptions on how persons with dementia perceive the end of life and on how they would respond to being interviewed. For instance, such assumptions included the idea that certain questions would be too complex (e.g. questions about potential future situations could be too cognitively challenging) or too confronting (e.g. questions about the future and end of life could induce distress in persons with a progressive illness).

To achieve openness, the interviewers used the attained self‐awareness to set aside assumptions and pre‐existing knowledge about the study topic and about the participants. They applied specific interviewing skills to enable a vulnerable group to speak in an open and trustful environment. For instance, they applied principles of active listening (Hargie, 2011). This involved nonverbal communication (e.g. adjusting one's height to level the other, adopt an open and attentive posture), reinforcement (e.g. encouraging the other to share their own opinion), open‐ended questioning, paraphrasing and reflecting (e.g. checking whether one's interpretation is correct, referring to past statements). The interviewers used feedback obtained immediately after the interviews, their notes and (fragments of) the audio recordings to reflect on their own interviewing style and on the attainment of an open atmosphere.

3.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables (e.g. age, sex) were calculated in Microsoft Excel. All interviews were transcribed clean verbatim for analyses. An inductive content analysis was performed, as the phenomenon under study requires more comprehensive knowledge (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The analysis was assisted by NVivo 12 software. Two researchers (SB and CK) read the interview transcripts to familiarise with the participants' stories. The unit of analysis involved the transcripts, and meaning units were fragments of texts (words, phrases or paragraphs), which were labelled with codes. Both researchers conducted inductive open coding separately on all transcripts and they met during regular analytical sessions to compare and discuss their coding. After analysis and discussion of the first three transcripts, the researchers used an agreed upon coding sheet with initial codes as a guide. In the continuing process, they labelled text fragments with initial codes when appropriate, altered initial codes, or formed additional inductive codes. After each next five interviews, the researchers compared their coding, discussed and refined codes that were added or altered and revised the coding sheet accordingly. Coding continued until data saturation was reached, at which point labelling text fragments did not require new codes. To confirm this, the lead author reread all transcripts to ensure the codes covered all content related to being cared for by others, the future and the end of life. Next, the researchers grouped codes together based upon resemblances to create categories. The final step in the analysis involved abstraction by collapsing categories into broader themes that reflected the underlying meaning (i.e. latent content) of categories and relationships between them (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

The analysis process was iterative and involved multiple analytical sessions during which the researchers compared their codes and code descriptions. In case of controversy, the researchers went back to the text fragments to check which definition captured its meaning. They moved back and forth reflectively between code definitions and text fragments. Data abstraction was an iterative process as well. The coders discussed the grouping of codes into categories and the subsequent grouping of categories into themes. The coders used their analytic sessions to confirm the interpretation of patterns. The lead author (SB) met with the co‐authors to seek agreement in data abstraction and the designation and interpretation of themes. This researcher triangulation increased rigour of the analysis. All authors agreed upon an illustration that was developed inductively from the themes to depict how the themes interrelate.

4. RESULTS

The following section tells the participants' story using pseudonyms (Table 2). Each theme consists of underlying categories, which were formed from the coded interview transcripts (Table 3). Figure 1 shows interrelations between the five themes and visualises tension between holding on and letting go, and resistance and resignation.

TABLE 3.

Structure of themes, categories and codes

| Theme | Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| My life still has value and meaning | I want to engage in meaningful activities | Keeping busy |

| Spending time purposefully | ||

| I want to be an active part of society | Social engagement | |

| Getting involved | ||

| Being put aside and forgotten | ||

| I want them to look at me as a human being | Say my piece | |

| Respect my dignity | ||

| I am my own unique individual | I want to manage myself | Do it myself |

| Do not want to be a burden | ||

| What defines me is what matters | My own environment and habits | |

| Memories that shaped me | ||

| Relationship to religion | ||

| I place my trust in other people | I appreciate professionals who care for me | Valuing caregivers |

| Having a connection | ||

| Unburden loved ones | ||

| Providing information | ||

| Others will know what is best for me | Others will know | |

| What would I do without them? | Directed by others | |

| What to do without them | ||

| The future worries me | I am in a tough spot | Confronted by decline |

| It is about me now | ||

| Tough world for older people | ||

| I am keeping the future at a distance | At a safe distance | |

| Staying at home for now | ||

| I accept and embrace what life brings | I am letting go | Acceptance |

| Ways to cope | ||

| Nothing more to ask for | ||

| This is all I hope for | Hope | |

| Content with this life | ||

| The future is now | ||

| Carrying on | ||

| It ends for all of us some day | Not a taboo topic | |

| The future will tell | ||

| All taken care of |

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual illustration of the interrelations between the five main themes, abstracted from categories. The illustration visualises tension between holding on and letting go, and resistance and resignation [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.1. My life still has value and meaning

When thinking about the future, the participants emphasised the importance of living a worthy and valuable life. As the dementia progressed, they insisted to hold on to activities that have meaning to them. They wanted to stay part of society and the social world. They wished for others to see their worth as a fellow, equal human being.

4.1.1. I want to engage in meaningful activities

It was important for participants to engage in activities that were meaningful and pleasant. For instance, particular hobbies in and around their own house, such as walking, reading the newspaper or doing the laundry, or activities organised by others (e.g. day care services).

Well, we usually walk around outside. Gives you something to do, gives you the feeling that you can still do something valuable. (Vincent)

Meaningful activities were activities that the person had been used to doing throughout his or her life. Sometimes trying new activities was appreciated, though there was a lot of variety in personal interests and in the type of activities that individuals (would) want to engage in, either in the community or in a facility. It was important for the participants that (future) caregivers considered these preferences.

I am passionate about music. Yes, having the opportunity [to make music], that would be ideal. (David)

4.1.2. I want to be an active part of society

Besides engaging in purposeful activities, participants emphasised that they wanted to stay an active member of society. They did not want to be set aside, even when the dementia got worse.

Well, that I can still do what I do, and that I am not put into a corner like an old doll. (Vincent)

Ways of staying an active and involved member of society included following the news, going out in public or joining clubs or committees. Most importantly, participants wanted to maintain social connections. They valued spending time with family members, friends or other people who share the experience of living with dementia.

I like living here, and I am also, I am not lonely. I get a lot of visitors and [daughter] picks me up every weekend, sometimes. (Lucy)

4.1.3. I want them to look at me as a human being

Thinking about other people who care for them, one of the most important things for participants was that they could speak up and that they were heard.

Well, for starters, talk to me like an equal, you know, I always appreciate that very much. (Lucas)

Some of the participants mentioned that it bothered them to think that other people, mainly professional caregivers, were not taking them seriously. Moreover, it was important for participants to maintain their dignity, particularly when other people took over certain (intimate) care tasks. Thinking about the future, if the dementia got worse, some participants feared losing their dignity. Being treated carefully and with respect may help to accept others' assistance while maintaining a feeling of self‐worth.

Well, you will simply get used to it [being cared for by others], you can accept it more easily when they explain to you “see, I am here to care for you,” and that they respect a person's dignity. (Vincent)

4.2. I am my own unique individual

The participants wanted to be seen as full‐fledged members of human society. They wanted others to see them for autonomous, unique individuals, with their own wishes, uses and particularities that define them.

4.2.1. I want to manage myself

All participants appreciated doing things in their own way and independently of others. Throughout their lives, they had been independent individuals and they were still very keen on managing themselves.

No, I am not that dependent, I prefer to manage myself, actually. And I prefer to make my own decisions. (Thomas)

Some of them found it difficult to accept assistance from others. Moreover, some disliked the feeling of being a burden to others or that they had to depend on others to fulfil their needs. They tried to do as much as they could by themselves, as long as they were still capable. It annoyed some of the participants when people took over tasks that they could easily do by themselves.

Well, I always say that everything that I can do myself, they should not do that for me, I want to do that myself. That is training. If you do sports, you have to practice every day as well. (Eva)

They thought that professional caregivers should be kept at bay as long as possible, or at least their assistance should be kept to a minimum. The thought of becoming more dependent in the future bothered or even scared some of the participants.

That I cannot, that I will become dependent on other people. That I will have to wait until someone gets there to wash me and I don't know what else, argh, that seems terrible to me. (Anna)

4.2.2. What defines me is what matters

All participants were keen on their own environment and routines. They liked to be at home, surrounded by their own things and the people that are familiar to them. Most of them knew their neighbourhood and hoped to stay in this familiar place in the future. Participants were inclined to talk about their memories: particular moments or situations that shaped them through the course of life. These private, unique stories had sometimes had an impact on their stance towards others and their view on life.

The first thing that comes to mind is that, if you have been a teacher for years, standing in front of a class full of teenagers, you are armed. Yes, I think, by being a teacher, I have learned about all these different characters, and you have those here [day care] as well. (Lucas)

Another factor that helped shape the participants' perspectives on life was religion. Most of them still found support in religion or religious activities such as saying prayers.

I still pray every day. And I pray every night before I go to bed. (Lucy)

Some had mixed feelings about religion. One participant had a special interest in Buddhism. A few others had distanced themselves from the church or showed little interest in religion. Most participants barely felt the need to discuss this topic with professional caregivers; it was more of a private matter to them.

4.3. I place my trust in other people

Although the participants preferred to do things by themselves, most of them also trusted other people who cared for them then or who might care for them in the future. They typically spoke warmly about these others. Most seemed prepared to put their trust in others to care for them, to make decisions for them or to manage other aspects of their life.

4.3.1. I appreciate professionals who care for me

Talking about professional caregivers such as the family doctor, the case manager and homecare workers, participants primarily expressed gratefulness and admiration. Most of them recognised that they need care or support in certain aspects of life or that they might need more care and support someday. Their expectations of having professionals caring for them were partly based on experiences in other situations (e.g. receiving care in the hospital, witnessing professionals caring for a family member). Some participants did receive homecare themselves, and they praised professional caregivers for being hardworking and skilful.

Well, in the first place that they are very good at what they do (…). They are skillful. They are really doing an excellent job. (James)

Moreover, some participants recognised that professional caregivers may help to unburden family caregivers. It was very important to the participants to build a trustful, empathetic care relationship with professional caregivers. Therein, it is important to get to know each other and to invest in an honest, harmonious connection.

[Case manager] treats me very well. As if we are two close friends. (Oliver)

Yes, they enjoy being here, we always make it a pleasant occasion, I always have coffee ready (…). If you trust each other, everything else will be better too. (Eva)

Getting familiar and building rapport were considered essential for a good care relationship. Also, humour was valuable to some of the participants.

Well, sometimes it is simply hilarious, (…) a somewhat older person who, well, who also held the opinion that a good laugh was very welcome, as we were not at the funeral yet, you know. And this [humor] was applied, which was very pleasant. (Leonard)

4.3.2. Others will know what is best for me

Although participants valued making their own decisions and speaking up for themselves; when it comes to making decisions surrounding the end of life they placed a lot of trust in others. Even when they had not explicitly talked about their wishes, participants trusted their loved ones to be aware of what they would or would not want.

Well, I think that it means that, without having discussed it, we believe that we naturally know these things about each other. In good faith. (Lucas)

These ‘trusted others’ were generally partners, family members or other informal caregivers, whereas a few participants mentioned physicians. For some of the participants, their trust in others was linked to the absence of clear advance directives and not having formally discussed end‐of‐life decisions.

No, but I think that doctors are very good at foreseeing how a patient will recover from anesthesia or whatever they have to recover from. (Eva)

Yeah well, what should I be thinking about that [the future]? I leave myself to others, you know. (Teddy)

4.3.3. What would I do without them?

Most of the participants recognised that other people played an increasingly important role in their lives. Participants needed help and support in certain areas of life, as some things were not as easy as they used to be.

You take this into account of course, that you cannot do everything by yourself anymore, so you have to hire other people to do things for you, so to speak. (Vincent)

Most participants accepted this, and they welcomed loved ones and other individuals entering their life and providing support. Nonetheless, a few of them noted that it was hectic at times, especially when multiple unfamiliar faces got involved within a short period.

So it is, the quiet life that we had, has become very hectic. (James)

Most importantly, loved ones often took on a prominent supporting role and participants appreciated them for helping out and taking over tasks. What would I do without them? Although this question reflected gratefulness, for some participants it also reflected anxiety.

I say this a hundred times a day. What would I do if she was not here? She does everything for me. (Benjamin)

4.4. The future worries me

All participants experienced, in one way or another, confrontation by decline. Former activities were becoming more and more difficult to pursue and some participants already had to give up on them. For some, observing this deterioration made it uneasy or unpleasant to think about the future, knowing that things might ‘get worse’. This triggered a sense of resistance.

4.4.1. I am in a tough spot

The participants were aware of their condition, and they recognised that they did not function in their daily lives the way they used to. A few of them also disliked the quick digitalisation of society and their inability to follow along. It bothered most of the participants that seemingly simple abilities that they used to take for granted were now challenging them in their daily routines.

Well, it is not pleasant, I can tell you. I have always done everything by myself, and then suddenly, it is all gone. (Nora)

I stood there with my t‐shirt in my hands and I just did not know where to start. What do I do with this thing? What is this? Well, that was not a pretty sight. (Joseph)

Most of them were also aware of the likeliness that their memory and overall functioning would decline further, which was an unsettling thought. Some participants expressed worries about having to leave their own home.

Yes, that scares me. If I would not know what is going on anymore, that I would have to leave this place [home]. (Lucy)

Thinking about the future, participants were uncertain and it was hard for them to imagine what awaits. This uncertainty raised concerns for some of them. Some of the participants witnessed others with dementia in later stages, and they considered that the same might be waiting for them, which was a confronting thought.

I do not want to end up walking around a ward with a doll, like my mother in law. Or like people that are rattling at the door because they want to go home, to their children or to their mommy or daddy. (Julia)

4.4.2. I am keeping the future at a distance

Thinking about the future and potential scenarios in case the dementia would get worse was unpleasant and therefore, most participants preferred keeping the future ‘at bay’.

I am not going to wrap my head around it [the future]. I am living right now, and how things will be in the future, well, I will see when I get there. (John)

Some of them recognised this as an avoidant way of coping with unpleasant thoughts about the future. Others stated that they did not care about the future or the end of life and therefore did not bother to talk about it.

See, people talking about dying, for instance. I do not care about that at all (…). I assume that I will stay alive, period. (Thomas)

A few of the participants never considered discussing end‐of‐life wishes before, and they wondered whether it might be useful. Some of them recognised that it is something that they would need to think or talk about at some point, but they mostly stated that now is not the time.

If I have to suffer, there is still plenty of time to talk about it. For now, just leave me be. (Eva)

For some, thinking or talking about the future or specifically thinking about having to leave their own home caused distress and was therefore preferably avoided.

4.5. I accept and embrace what life brings

In contrast to the ominousness and, at times, anxiety experienced by participants when thinking about the future, they also expressed hope, acceptance and contentment with life. Most participants lived day by day and tried to make the most out of their lives. They accepted losses, dealt with challenges and found ways to cope with their condition. Most participants expressed contentment with the life they had lived and that they were living. Also, most were rather down‐to‐earth about the end of life, regarding it as something that all of us will have to deal with someday and that we have no control over.

4.5.1. I am letting go

The participants had developed ways to deal with and adapt to their gradual losses. They tried to seize the days while they last, and most of them expressed gratitude for things that they were still able to do. Besides living their life as it was now, there was not much more for them to ask for.

You know, so, you just have to learn to live with it and be grateful that you can still do things. (Vincent)

Most of them were aware that there was nothing that they could do about their decline and some stated that acceptance is key to still living a pleasurable life. As most things in life, living with dementia is something that one had to get used to.

Everything is still alright, as long as you do not put up a fight. (Caroline)

4.5.2. This is all I hope for

The participants expressed contentment with the life they were currently living and the life they had lived. They did not hope for a lot more in the future and mainly wished that things would stay the way that they were now for as long as possible.

Yes, I am a very content person. Where I am, what I do, honestly. As long as she is here with me, nothing bad can happen to me. (Joseph)

They primarily hoped to stay healthy for a bit longer, and most of them had a positive stance towards the days that were to come in the near future. Some of the participants believed that there was no future beyond these days; their time had come and gone and that was alright.

I do not really have much of a future anymore, I have lived through it all, I have lived a very good and pleasant life. (Eva)

4.5.3. It ends for all of us someday

The end of life is an ambiguous topic, and most of the participants expressed mixed feelings when talking about it. The end of life was somewhat mysterious, and although thinking or talking about death was upsetting for a few of them, most participants also expressed resignation and regarded death as something inevitable that awaits all humans one day.

Yes, well, it [dying] can happen and it can happen to anyone, and the older you get, the higher the odds, I presume. (Sophie)

Accordingly, most participants ‘had taken care of’ certain arrangements surrounding the end of life, such as creating a living will or discussing or documenting wishes about after their death.

I am very down to earth when it comes to that. (…) My children know what needs to happen, they know where I wish to be cremated and they know where I want them to scatter my ashes. (Anna)

No one knows what the future will bring. Therefore, some participants were sceptical about ‘directing’ the end of life, even though death was not necessarily a taboo topic.

You can, look, how things will work out in the end… Anyway, that will mainly unfold as it happens, when or wherever that is, I think. (Leonard)

5. DISCUSSION

This study shows the perspectives of people with dementia on being cared for by others, on their future and on the end of life. It shows that not only the participants were capable of having a conversation about the future and the end of life; they were also willing to share their thoughts. They offered valuable insight into their perspectives. The participants expressed a strong wish to live a meaningful life and to be seen by others as worthy and unique humans. They wanted to stay active and involved as a member of society for as long as possible. Nonetheless, the participants were confronted with their declining functioning, which posed challenges to maintaining their independence in daily routines and activities. The thought of further decline was unpleasant and participants preferred distancing themselves from this worrying future. They were generally content with their current existence and tended to live day by day. They wished for things to stay this way, and they did not hope for much more. Although they wished to remain autonomous for as long as possible, they placed a fair amount of trust in others to support them, care for them or make decisions for them about the end of life. They appreciated other people who helped them and they valued trustful and friendly connections. Although ambiguity and sometimes anxiety or denial lingered when thinking about the future, most participants perceived death itself as something inevitable, which involved a sense of resignation.

5.1. Meaning of life and personhood

People with dementia in previous studies expressed aspects that are important to their quality of life, which include overall well‐being and functioning, participation in activities, maintaining friendships and having a sense of belonging (de Boer et al., 2007). In their review, de Boer and colleagues focused on how people with dementia experience living with the condition. Although our study had a different focus, we found a similar desire of people with dementia to stay an active member of society and to be valued by others as an individual, also through the later stages. The need for belongingness and recognition are basic and universal psychological needs (Maslow, 1943). Fulfilling these needs through engagement in meaningful activities and participation in day‐to‐day life are important to life meaning and well‐being (Eakman, 2013). In our study, while talking about the future and dependency on others for care towards the end of life, these basic human needs surfaced. The findings point to specific expectations, beliefs or fears that people with dementia hold about their future, in which those needs may be compromised. Similarly, a previous study found that people with dementia fear ‘losing control’, which involves a fear of dependency, being a burden to others and loss of role functioning (Read et al., 2017). The wish to live a worthy and meaningful life might be challenged when one has dementia, as in western society cognitive functions are viewed as core human abilities and prerequisites to maintain self‐control, independence, personhood and meaningful relations with others (Post, 2000). Descartes' famous quote ‘Cogito ergo sum’, ‘I think, therefore I am’ is fundamental in western philosophy and suggests that ‘thinking’ (i.e. cognition) is inextricably linked to ‘being’. Person‐centred care in dementia promotes personhood and aims to foster a sense of belongingness through empathetic care relationships characterised by recognition, respect and trust (Kitwood & Bredin, 1992). Our results underline the importance of empathetic relationships and suggest that ‘being seen’ by others is highly valuable to people living with early‐stage dementia.

5.2. (Blindly) trusting others in end‐of‐life decision‐making

Most participants in our study were willing to talk about their view on the end of life and on discussing care plans, although some declared disinterest or unwillingness to think about or plan for the future. Shared decision‐making and advanced care planning are suggested key elements of palliative dementia care (van der Steen et al., 2014). In our study, some of the participants reported that they had not discussed future care simply because no one had asked them about it. The provision of information and the initiation of advance care planning is primarily the responsibility of healthcare professionals, albeit tailored to the individual's readiness (Sinclair et al., 2016; Zwakman et al., 2018). Similar to previous findings (Poole et al., 2018), participants in our study who reported to have ‘taken care of’ end‐of‐life arrangements often referred to living wills or post‐death arrangements rather than details about future care. Moreover, as in our study, people with early‐stage dementia may feel it is not yet ‘time’ to discuss end‐of‐life wishes formally (Dickinson et al., 2013). More research is needed to investigate how advance care planning for people with dementia can be implemented into practice and to inform healthcare professionals on proper ways to establish shared decision‐making in setting goals of (palliative) care.

The participants in our study commonly trusted their loved ones to make the right decisions on their behalf, even if their wishes had not been discussed. This corresponds to previous findings, which describe confidence of people with dementia in their family members to know and advocate for their wishes at the end of life (Poole et al., 2018). The eminent trust of people with dementia in their family members to manage their care is at odds with experiences of families with end‐of‐life care, who may feel unprepared (Caron et al., 2005; Forbes et al., 2000). Nonetheless, in a previous study, we found that family caregivers of people with dementia sometimes felt confident in making decisions even if the person with dementia had never discussed the end of life with them (Bolt, Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, & Meijers, 2019). There are many factors that influence experiences with proxy decision‐making other than the presence or absence of explicit end‐of‐life wishes (Harrison Dening et al., 2016; Hirschman et al., 2006; Kwak et al., 2016). Previous studies emphasise the importance of trust between proxy decision‐makers and staff in long‐term care (Bolt, Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, & Meijers, 2019; Cresp et al., 2018). A trustful care relationship contributes to proxies' confidence and an overall positive experience with decision‐making.

5.3. Coping and the tension between holding on and letting go

The impact of living with dementia on one's quality of life is influenced by coping strategies used by people with dementia (de Boer et al., 2007). Coping strategies show how people come to terms with their condition. In our study, participants merely demonstrated resilience. They aimed to continue living their lives by staying active and socially involved. Some openly struggled with bothersome symptoms, whereas others minimised or normalised having dementia or used humour to cope. Strategies of denial and avoidance mainly applied to (not) thinking about the end of life. Coping strategies used by people with dementia may serve self‐maintenance or self‐adjustment, and the types of coping strategies used by individuals may change as the dementia progresses (Steeman et al., 2006). Fetherstonhaugh et al. (2013) found that people with dementia prefer if others provide ‘subtle support’, enabling them to maintain feelings of control and independence in their decisions and choices. They experience a tension between letting go and wanting to hold on to their abilities for as long as possible. Our study adds to these findings by demonstrating that the tension between holding on and letting go extends beyond decision‐making and coping strategies and applies to the overall experience of living with, coming to terms with, and thinking about the future with dementia. Future research may explore how specific coping mechanisms relate to readiness for end‐of‐life communication.

5.4. Limitations and strengths

The study used a purposive, criterion‐based sample recruited by care professionals. Recruiters made a judgement about potential participants' willingness and ability to be interviewed based on their knowledge of the individual resulting from an established care relationship. This fact may have biased the results as people that were not considered willing or able to be interviewed may hold different perspectives. The participants' responses may be biased as individuals who are prepared to openly discuss end‐of‐life topics may be more likely to participate.

During some of the interviews, an informal caregiver was present. Although they were not formally involved and requested not to interfere, some had additional remarks or helped the person with dementia to answer questions. During one interview, a formal caregiver insisted on being present and intervened several times during the conversation (e.g. commenting on the difficulty of questions being asked). One participant had just moved to a care home and had more advanced dementia. Although he did not understand some of the questions, he touched on the same themes. This suggests that the findings may apply to people in different stages of dementia. A pre‐defined topic list guided the interviews; although participants were invited to address additional topics, certain aspects were not questioned nor addressed (e.g. sexuality).

This study's key strength is that it describes the perspective of people with dementia themselves while simultaneously demonstrating the capability of people with dementia to discuss the future and the end of life. During the interviews, the researchers pursued openness, which meant increased self‐awareness and setting aside judgements and personal perspectives. This supported a trustful and safe interview environment and researchers' receptiveness to the participants' perspectives. Interview transcripts hold multiple meanings and an interviewer's frame of reference and personal characteristics (e.g. age, gender, education and religious or spiritual belief systems) may affect data collection and interpretation (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The frequent analytical discussions enabled reflection on the researchers' own position throughout this study (e.g. role as interviewers, possible biases and influence on the research). The reflective nature of the process strengthened the rigour of the analysis and the trustworthiness of the findings.

6. CONCLUSIONS

When thinking about the future and the end of life, the people with dementia in this study expressed a variety of feelings, such as ambiguity, anxiety, contentment and resignation. Despite fear of further decline and dependency, they demonstrated resilience and acceptance towards death. The individuals expressed thankfulness for the life that they had lived and they hoped for things to stay the same for as long as possible. When thinking about being cared for by others, the individuals in this study expressed appreciation and trust. They had a particularly strong wish to live a worthy and meaningful life and to maintain uniqueness and belongingness until the end of life. Others should regard and treat people with dementia as equal and worthy human beings to fulfil their basic human need to ‘matter’ and to ‘belong’.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

This study holds particular practical value by demonstrating that, when given the opportunity, most participants with dementia showed openness, willingness and capability to discuss the future and the end of life in a non‐medical informal setting. Some of the participants did not recall having been asked about their end‐of‐life wishes and wondered whether it would be helpful to discuss this some time. Public and professional awareness is needed on the value of (informal) end‐of‐life conversations. Although this may be particularly relevant with regard to dementia, awareness and normalisation of end‐of‐life communication may also serve other populations with chronic life‐limiting conditions. Training and education is needed to equip healthcare professionals to inform people with dementia and their families and to initiate such conversations in a sensitive manner (Harrison Dening et al., 2019).

The current findings add to the literature as they evoke questions about the appropriateness and desirability of advance care planning for people with dementia. As an important part of an early palliative care approach, conversations in the context of advance care planning should be tailored to an individual's life view, preferences and readiness to talk. A wish to refrain from talking about the future and to relinquish care decisions to (knowledgeable) others should be respected. Yet, opportunities for conversations about future care and the end of life should be offered regularly, as individuals' readiness to talk may change. The process of advance care planning itself may promote such readiness (Zwakman et al., 2018). Our study demonstrates that even persons who do not wish to discuss their end of life may be willing to share their thoughts on the future and on why they would or would not bother to discuss or document care wishes in advance. When aiming to discuss the future, it might be helpful to first explore how individuals cope with their condition.

Healthcare professionals should invest in building equal and trustful care relationships with persons with dementia and their family caregivers. To achieve this, one should acknowledge (‘see’) the person with dementia and invest in getting to know them. A previously described culture change movement towards person‐centred care in nursing homes (Koren, 2010) applies to a range of settings in which people with dementia reside, including the community. In adopting a palliative approach to care for persons with dementia and their families, communities and care organisations should promote person‐centredness and relationship‐centredness by fostering belongingness of people with dementia and by involving family caregivers. It is important that long‐term care managers facilitate healthcare professionals to apply person‐centred and relationship‐centred care, for instance by giving them sufficient time and space to build strong relationships. Policy makers may promote person‐centredness by setting up dementia‐friendly policies and by funding initiatives that support participation of people with dementia in society.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors SB and JM set up the design of the study, and JvdS, JS and SZ approved the study design. SB and CK collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data first. All authors were involved in the final interpretation of the data. SB prepared the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all participants of this study, and their loved ones, for their openness and willingness to share their thoughts with us. We thank the dementia case managers and other healthcare professionals for their help in setting up the interviews and for the recruitment of participants. A special thanks to recruiter and nurse practitioner Ina Schutgens, who gave additional and valuable advice on interviewing people with dementia, and to qualitative research expert Albine Moser, RN, MPH, PhD, who helped us to clarify the methodology in the article.

Funding information

ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development [grant number 844001405] provided funding for this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study have not been made publicly available due to ethical and legal reasons. The interview transcripts (in Dutch) contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of participants. Participants did not consent for their data to be shared publicly.

REFERENCES

- Beerens, H. C. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , Verbeek, H. , Ruwaard, D. , & Hamers, J. P. H. (2013). Factors associated with quality of life of people with dementia in long‐term care facilities: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(9), 1259–1270. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernaert, K. , Deliens, L. , De Vleminck, A. , Devroey, D. , Pardon, K. , Block, L. V. D. , & Cohen, J. (2016). Is there a need for early palliative care in patients with life‐limiting illnesses? Interview study with patients about experienced care needs from diagnosis onward. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 33(5), 489–497. 10.1177/1049909115577352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , Meijers, J. M. M. , van der Steen, J. T. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , & Zwakhalen, S. M. G. (2020). Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for persons with dementia at home or in nursing homes: A survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52(2), 164–173. 10.1111/jnu.12542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , van der Steen, J. T. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , & Meijers, J. M. M. (2019). What do relatives value most in end‐of‐life care for people with dementia? International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 25(9), 432–442. 10.12968/ijpn.2019.25.9.432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , van der Steen, J. T. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , Pieters, S. , & Meijers, J. M. M. (2019). Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for people with dementia at home or in long‐term care facilities: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 96, 143–152. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , Verbeek, L. , Meijers, J. M. M. , & van der Steen, J. T. (2019). Families’ experiences with end‐of‐life care in nursing homes and associations with dying peacefully with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(3), 268–272. 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A. , Rowe, G. , Adams, S. , Sands, P. , Samsi, K. , Crane, M. , Joly, L. , & Manthorpe, J. (2015). Quality of life in dementia: A systematically conducted narrative review of dementia‐specific measurement scales. Aging & Mental Health, 19(1), 13–31. 10.1080/13607863.2014.915923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H. , Seeher, K. , & Gibson, L. (2012). Dementia time to death: A systematic literature review on survival time and years of life lost in people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(7), 1034–1045. 10.1017/s1041610211002924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron, C. D. , Griffith, J. , & Arcand, M. (2005). End‐of‐life decision making in dementia: The perspective of family caregivers. Dementia, 4(1), 113–136. 10.1177/1471301205049193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cresp, S. J. , Lee, S. F. , & Moss, C. (2018). Substitute decision makers’ experiences of making decisions at end of life for older persons with dementia: A systematic review and qualitative meta‐synthesis. Dementia (London) , 19(5), 1532–1559. 10.1177/1471301218802127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, M. E. , Hertogh, C. M. , Droes, R. M. , Riphagen, I. I. , Jonker, C. , & Eefsting, J. A. (2007). Suffering from dementia – The patient's perspective: A review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(6), 1021–1039. 10.1017/s1041610207005765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dening, K. H. , Jones, L. , & Sampson, E. L. (2011). Advance care planning for people with dementia: A review. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(10), 1535–1551. 10.1017/s1041610211001608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, C. , Bamford, C. , Exley, C. , Emmett, C. , Hughes, J. , & Robinson, L. (2013). Planning for tomorrow whilst living for today: The views of people with dementia and their families on advance care planning. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(12), 2011–2021. 10.1017/s1041610213001531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakman, A. M. (2013). Relationships between meaningful activity, basic psychological needs, and meaning in life: Test of the meaningful activity and life meaning model. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health (Thorofare N J), 33(2), 100–109. 10.3928/15394492-20130222-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S. , & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetherstonhaugh, D. , Tarzia, L. , & Nay, R. (2013). Being central to decision making means I am still here!: The essence of decision making for people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(2), 143–150. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S. , Bern‐Klug, M. , & Gessert, C. (2000). End‐of‐life decision making for nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(3), 251–258. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, C. , Amador, S. , Elmore, N. , Machen, I. , & Mathie, E. (2013). Preferences and priorities for ongoing and end‐of‐life care: A qualitative study of older people with dementia resident in care homes. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(12), 1639–1647. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U. H. , & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, A. W. , Smith, S. J. , Martin, A. , Meads, D. , Kelley, R. , & Surr, C. A. (2019). Exploring self‐report and proxy‐report quality‐of‐life measures for people living with dementia in care homes. Quality of Life Research, 29(2), 463–472. 10.1007/s11136-019-02333-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal communication: Research, theory and practice (5th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening, K. , King, M. , Jones, L. , Vickestaff, V. , & Sampson, E. L. (2016). Advance care planning in dementia: Do family carers know the treatment preferences of people with early dementia? PLoS One, 11(7), e0159056. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening, K. , Sampson, E. L. , & De Vries, K. (2019). Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliative Care: Research and Treatment, 12, 1178224219826579. 10.1177/1178224219826579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S. R. , Mason, H. , Poole, M. , Vale, L. , & Robinson, L. (2017). What is important at the end of life for people with dementia? The views of people with dementia and their carers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(9), 1037–1045. 10.1002/gps.4564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, K. B. , Kapo, J. M. , & Karlawish, J. H. T. (2006). Why doesn't a family member of a person with advanced dementia use a substituted judgment when making a decision for that person? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(8), 659–667. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203179.94036.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood, T. M. , & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well‐being. Ageing and Society, 12(3), 269–287. 10.1017/S0144686X0000502X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, M. J. (2010). Person‐centered care for nursing home residents: The culture‐change movement. Health Affairs, 29(2), 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J. , De Larwelle, J. A. , Valuch, K. O. , & Kesler, T. (2016). Role of advance care planning in proxy decision making among individuals with dementia and their family caregivers. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9(2), 72–80. 10.3928/19404921-20150522-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. P. , Bamford, C. , Poole, M. , McLellan, E. , Exley, C. , & Robinson, L. (2017). End of life care for people with dementia: The views of health professionals, social care service managers and frontline staff on key requirements for good practice. PLoS One, 12(6), e0179355. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G. , Pitfield, C. , Morris, J. , Manela, M. , Lewis‐Holmes, E. , & Jacobs, H. (2012). Care at the end of life for people with dementia living in a care home: A qualitative study of staff experience and attitudes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 643–650. 10.1002/gps.2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, P. J. , Araki, S. S. , & Gutterman, E. M. (2000). The use of proxy respondents in studies of older adults: Lessons, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(12), 1646–1654. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03877.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrar, K. M. , Schmidt, H. , Eisenmann, Y. , Cremer, B. , & Voltz, R. (2015). Needs of people with severe dementia at the end‐of‐life: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 43(2), 397–413. 10.3233/JAD-140435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole, M. , Bamford, C. , McLellan, E. , Lee, R. P. , Exley, C. , Hughes, J. C. , Harrison‐Dening, K. , & Robinson, L. (2018). End‐of‐life care: A qualitative study comparing the views of people with dementia and family carers. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 631–642. 10.1177/0269216317736033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe, M. , Burleigh, S. , & Banerjee, S. (2013). Qualitative evaluation of advanced care planning in early dementia (ACP‐ED). PLoS One, 8(4), e60412. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post, S. G. (2000). The concept of Alzheimer disease in a hypercognitive society. In Concepts of Alzheimer disease: Biological, clinical and cultural perspectives (pp. 245–256). [Google Scholar]

- Read, S. T. , Toye, C. , & Wynaden, D. (2017). Experiences and expectations of living with dementia: A qualitative study. Collegian, 24(5), 427–432. 10.1016/j.colegn.2016.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky, R. , Porterfield, P. , Lee, J. , Dixon, D. , Lounsbury, K. , Pesut, B. , Roberts, D. , Tayler, C. , Voth, J. , & Stajduhar, K. (2016). Conceptual foundations of a palliative approach: A knowledge synthesis. BMC Palliative Care, 15(1), 5. 10.1186/s12904-016-0076-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. B. , Oyebode, J. R. , & Owens, R. G. (2016). Consensus views on advance care planning for dementia: A Delphi study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(2), 165–174. 10.1111/hsc.12191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeman, E. , De Casterlé, B. D. , Godderis, J. , & Grypdonck, M. (2006). Living with early‐stage dementia: A review of qualitative studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 54(6), 722–738. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufford, L. , & Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 11(1), 80–96. 10.1177/1473325010368316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, J. T. (2010). Dying with dementia: What we know after more than a decade of research. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 22(1), 37–55. 10.3233/jad-2010-100744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, J. T. , Radbruch, L. , Hertogh, C. M. P. M. , de Boer, M. E. , Hughes, J. C. , Larkin, P. , Francke, A. L. , Jünger, S. , Gove, D. , Firth, P. , Koopmans, R. T. C. M. , & Volicer, L. (2014). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 197–209. 10.1177/0269216313493685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riet Paap, J. , Mariani, E. , Chattat, R. , Koopmans, R. , Kerhervé, H. , Leppert, W. , Forycka, M. , Radbruch, L. , Jaspers, B. , Vissers, K. , Vernooij‐Dassen, M. , & Engels, Y. (2015). Identification of the palliative phase in people with dementia: A variety of opinions between healthcare professionals. BMC Palliative Care, 14, 56. 10.1186/s12904-015-0053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijngaarden, E. , Alma, M. , & The, A. M. (2019). ‘The eyes of others’ are what really matters: The experience of living with dementia from an insider perspective. PLoS One, 14(4), e0214724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012). Dementia: A public health priority. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75263/9789241564458_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0AF0CA6DADC145549CA73B630CAC33A3?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- Zwakman, M. , Jabbarian, L. J. , van Delden, J. , van der Heide, A. , Korfage, I. J. , Pollock, K. , Rietjens, J. , Seymour, J. , & Kars, M. C. (2018). Advance care planning: A systematic review about experiences of patients with a life‐threatening or life‐limiting illness. Palliative Medicine, 32(8), 1305–1321. 10.1177/0269216318784474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study have not been made publicly available due to ethical and legal reasons. The interview transcripts (in Dutch) contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of participants. Participants did not consent for their data to be shared publicly.