Abstract

A decrease in the ceramide content of the stratum corneum is known to cause dry and barrier‐disrupted skin. In this literature review, the clinical usefulness of preparations containing natural or synthetic ceramides for water retention and barrier functions was evaluated. The PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Igaku Chuo Zasshi databases were searched using keywords such as “ceramide”, “skincare products”, “barrier + hydration + moisture + skin”, and “randomized trial”. All database searches were conducted in February 2019. Forty‐one reports were selected based on the following criterion: comparative control studies that evaluated the effects of ceramide‐containing formulations based on statistical evidence. Among the 41 reports, 12 were selected using the patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome approach. These 12 reports showed that external ceramide‐containing preparations can improve dry skin and barrier function in patients with atopic dermatitis. However, a double‐blinded comparative study with a large sample size is warranted for appropriate clinical use.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, ceramides, dry skin, intercellular lipid of stratum corneum, skin barrier

1. INTRODUCTION

The skin, which covers the entirety of the human body, is the largest organ, and it fulfills a variety of functions and roles critical to homeostasis, including the following: (i) water retention in the body; (ii) thermoregulation; (iii) prevention of irritation and invasion of external microorganisms and foreign substances; and (iv) function as a sensory organ. Regarding the third barrier function, there are three important factors, namely filaggrin, tight junction, and stratum corneum lipids. Recent studies showed the important role of filaggrin gene mutation in barrier dysfunction of atopic dermatitis. 1 Although tight junction of the upper epidermis is a critical structure for skin barrier function, 2 the association with skin diseases is not yet fully elucidated and a possible role in barrier dysfunction of atopic dermatitis is suggested. 3

The outermost layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, is responsible for maintaining the barrier function of the skin, which is particularly important for preserving a constant internal environment. 4 The stratum corneum is composed of 10–15 layers of corneocytes separated by lipid layers and has been described as having a “brick and mortar” structure. 5 The intercellular lipids of the stratum corneum that make up these lipid layers form an amphipathic extracellular lipid matrix, which retains bound water, performs a moisturizing function, and maintains the strong bond between corneocytes. This lipid matrix acts as a barrier that prevents water loss from the epidermis and invasion of the body by external foreign substances. 6 , 7 The components of intercellular lipids are ceramides, cholesterols, and cholesterol esters. 8 Ceramides, which constitute approximately 50% of these lipids (by weight), are sphingolipids consisting of sphingosine bases bound to fatty acids via amide linkages. There are 12 subclasses of ceramides, categorized by the types of constituent sphingosines and fatty acids. 9

Treatment with an organic solvent to reduce its intercellular lipids of the stratum corneum has been shown to result in dry skin and reduced barrier function. 10 Additionally, a decrease in ceramide levels has been observed in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic dermatitis, and this decrease is considered to be a factor in the dry skin and decreased barrier function seen in atopic dermatitis. 11 To maintain and repair the skin barrier, it is important to reduce the aggravating factors. However, external supplementation of the lipid content, such as with ceramides, should be considered. Moisturizers that contain “blocking” ingredients such as petrolatum and lanolin prevent water loss by covering the surface of the skin. 12 Furthermore, the skin barrier function and water retention capacity of the stratum corneum are improved by moisturizers containing natural or synthetic ceramides. 13

In this study, in an effort to understand the clinical applications of synthetic ceramide or ceramide‐containing formulations, we reviewed both domestic and international literature to evaluate whether ceramide‐containing formulations are beneficial for improving skin dryness and barrier function.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search

The PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Igaku Chuo Zasshi (Ichushi) databases were searched using keywords such as “ceramide,” “skincare products,” “barrier + hydration + moisture + skin”, and “randomized trial.” All database searches were conducted in February 2019.

2.2. Literature selection

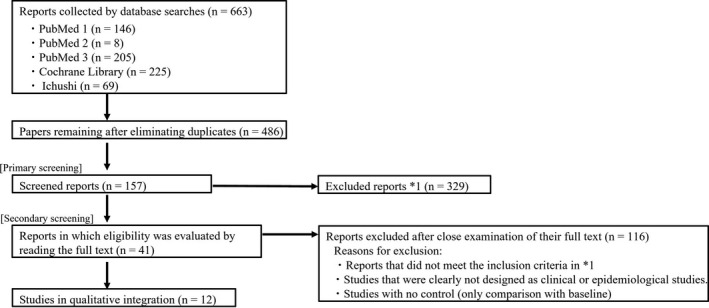

In the first round of screening, we examined the titles and abstracts of all retrieved papers (regardless of language) and selected studies concerned with the external application of ceramide‐containing formulations to moisturize and improve the barrier function of human skin. Studies on the application of ceramide‐containing formulations to the skin of non‐human animals, p.o. administration of ceramides, mechanisms of ceramide lipid metabolism, or basic studies of designer drugs (e.g., for cancer therapies) were excluded. Furthermore, duplicate results (i.e., retrieval of the same paper from multiple databases) were excluded. In the second round of screening, the full texts of selected papers were read; letters and non‐systematic reviews were excluded; and clinical or epidemiological studies that fit the evaluation objectives of this study were selected (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Literature search flowchart. Date from literature search. PubMed 1: 18 February 2019; PubMed 2: 18 February 2019; PubMed 3: 18 February 2019; Cochrane Library: 18 February 2019; Ichushi: 18 February 2019. *1 Reports not meeting the following inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts were excluded: English‐language or Japanese reports on skin care effects (improvement of skin conditions) using a ceramide‐containing preparation. Exclusion criteria: research on drug development, including studies using non‐human skin, oral administration (functional foods and medical products), lipid metabolism, and cancer treatment

2.3. Critical examination

In the first stage of the review process, we evaluated each research report. The evidence level of each study was ranked according to its research design, and the content of each study was organized into the patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) format. 14 Furthermore, research designs were ranked according to existing evidence level systems (Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine 2011 levels of evidence, LOE): meta‐analyses and systematic reviews were ranked as LOE 1; randomized controlled trials (RCT), LOE 2; non‐RCT, LOE 3; cohort and case–control studies, LOE 4; and case collections, LOE 5. 15

In the second stage of the review process, we used the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) system, which is on its way to becoming the global standard for evidence‐based medicine evaluations. 16 In cases where it was possible to integrate findings from multiple similar studies, we evaluated the overall evidence level of these studies after integration (as quantitative systematic reviews or meta‐analyses).

3. RESULTS

The results obtained from PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Ichushi are shown in Figure 1. A total of 663 reports were extracted. After eliminating duplicates across databases, 486 papers remained. After the first round of screening of these 486 papers, 157 remained. Finally, after the second round of screening, 41 papers were found to discuss the moisturizing and barrier improvement effects of the application of ceramide‐containing formulations on human skin (Table 1). 13 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 PICO and effect‐index similarity analyses were performed for these 41 papers.

TABLE 1.

Forty‐one reports obtained through the second round of screening

| Ref. number | Authors | Year | Skin disease/condition | LOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Spada et al. | 2018 | Normal skin/sensitive skin | 2 |

| 17 | Marseglia et al. | 2014 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 18 | Draelos | 2011 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 19 | Frankel et al. | 2011 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 20 | Sugarman et al. | 2009 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 21 | Miller et al. | 2011 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 22 | Draelos | 2008 | Eczema | 2 |

| 23 | Berardesca et al. | 2001 | Atopic dermatitis, irritation contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis | 2 |

| 24 | Sugiura et al. | 2006 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 25 | Kircik | 2014 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 26 | Wananukul et al. | 2013 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 27 | Yamagishi et al. | 2011 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 28 | Hata et al. | 2002 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 29 | Mizutani et al. | 2001 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 30 | Koppes et al. | 2016 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 31 | Lee et al. | 2003 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 32 | Nakamura et al. | 1999 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 33 | Ma et al. | 2017 | Atopic dermatitis | 2 |

| 34 | Matsumoto et al. | 2007 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| 35 | Weber et al. | 2012 | Sebum deficiency | 2 |

| 36 | Morganti et al. | 1999 | Mild dry skin | 2 |

| 37 | Daehnhardt et al. | 2016 | Sebum deficiency | 2 |

| 38 | Machado et al. | 2007 | Sebum deficiency | 3 |

| 39 | Nojiri et al. | 2018 | Sebum deficiency | 2 |

| 40 | Liu et al. | 2015 | Psoriasis | 2 |

| 41 | Kiyohara et al. | 2014 | Health‐care workers (hand irritation caused by repeated hand washing) | 2 |

| 42 | Lodén et al. | 2000 | Healthy skin of healthy people or skin treated with tape stripping/sodium lauryl sulfate | 2 |

| 43 | Kucharekova et al. | 2002 | Healthy skin of healthy people or skin treated with tape stripping/sodium lauryl sulfate | 3 |

| 44 | Huang et al. | 2008 | Healthy skin treated with sodium lauryl sulfate | 3 |

| 45 | De Paepe et al. | 2002 | Healthy skin treated with sodium lauryl sulfate or acetone | 2 |

| 46 | De Paepe et al. | 2000 | Healthy skin treated with sodium lauryl sulfate | 2 |

| 47 | Shinohara et al. | 2014 | Hand–foot skin reaction (induced by sorafenib) | 2 |

| 48 | Tsuboi et al. | 2006 | Health‐care workers (hand irritation caused by repeated hand washing) | 3 |

| 49 | Ishikawa et al. | 2003 | Pressure ulcers | 3 |

| 50 | Hao et al. | 2015 | Pressure ulcer | 3 |

| 51 | Cannizzaro et al. | 2018 | Irritated skin (side‐effect of oral isotretinoin) | 2 |

| 52 | Okuda et al. | 2002 | Healthy skin of healthy people | 3 |

| 53 | Byun et al. | 2012 | Healthy people (skin damage due to UV exposure) | 2 |

| 54 | Sugita et al. | 2009 | Healthy women (age‐related wrinkles on the outer corners of the eyes, nasolabial folds) | 2 |

| 55 | Berger et al. | 2018 | Ostomy skin (skin protectant) | 4 |

| 56 | Colwell et al. | 2018 | Ostomy skin (skin protectant) | 2 |

Abbreviations: LOE, Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine level of evidence; UV, ultraviolet.

3.1. Critical examination

To examine the possibility of conducting a quantitative meta‐analysis, we attempted to compare studies with common subjects and interventions.

First, let us consider studies that evaluated ceramide‐containing formulations in the context of atopic dermatitis. One report detailed a 28‐day evaluation of young children with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis, in which the efficacy of ceramide‐containing formulations was equivalent to that of topical steroids (control group). 20 Another report detailing a 21‐day evaluation of the same formulation in young children with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis found no significant difference in the efficacy between the ceramide‐containing formulation and a petrolatum; however, the petroleum was more cost‐effective. 21 We believe that the difference in the severity of atopic dermatitis of targeted patients, their age, and trial period are all reasons for the same product receiving different evaluations in these two reports. However, even if ceramide‐containing formulations did not perform significantly differently from petroleum when skin symptoms were comparatively mild, ceramide‐containing formulations exhibited the same effect as topical steroids when symptoms were more severe. This suggests that in addition to their moisturizing and barrier function‐improving effects, ceramide‐containing formulations possess anti‐inflammatory properties.

In other similar studies, even when the same ceramide‐containing formulations were used, differences in skin condition (patient, P), trial duration (intervention, I), and comparison product (comparison, C) led to a variety of observed effects (outcome, O). Thus, we determined that it would be difficult to implement our planned second‐stage critical examination, the quantitative meta‐analysis recommended by the GRADE system. Therefore, we returned to the first stage of our critical evaluation process and decided to limit ourselves to collecting target papers, selecting papers with representative evidence, and conducting a qualitative meta‐analysis. Our selection criteria were as follows: (i) controlled studies (LOE ≥ 2 as categorized by the aforementioned research design‐based system); and (ii) studies that used statistical methodologies to investigate the moisturizing and/or barrier function‐improving effects of ceramide‐containing formulations.

3.2. Qualitative meta‐analysis

From among the 41 reports discussing the moisturizing and barrier function‐improving effects of ceramide‐containing formulations, we searched for comparative RCT (which have a high LOE) that targeted patients with skin barrier function disorders. After excluding studies that used skin irritation models in healthy individuals, we found 12 reports that targeted skin illnesses. The breakdown of these studies is as follows: atopic dermatitis, eight reports; xerosis, three reports; and hand–foot skin reaction, one report.

An overview of these 12 papers, which we used to evaluate the effects of ceramide‐containing formulations, is given in Table 2. 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 47 Most studies on atopic dermatitis targeted mild‐to‐moderate illness, and ceramide‐containing formulations were shown to improve skin function, such as by improving water content and inhibiting transepidermal water loss. Outlines of several representative examples from these reports are provided below.

TABLE 2.

PICO for reports selected via the second round of screening

| Ref. no. | Research design | LOE | Patient (P) | Intervention (I) | Comparator (C) | Outcome (O) | Species of ceramide or pseudo‐ceramide | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target illness | Cases (sex, age) | Indices | Results | ||||||

| 17 | Open‐label RCT (evaluator blinded) | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

107 cases (59 males/48 females, 5.9 years old)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 6 weeks |

Control cream Dosage: applied to affected area 2 times daily Period: 6 weeks |

|

ESS over the 6‐week period was significantly lower in the group using ceramide‐containing cream than in the control group. Both groups exhibited good tolerance. | Ceramide 3 |

| 18 | Double‐blind RCT (body partitioned) | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

20 cases (20 females, ≥18 years old)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks (one of either the left or right leg or arm) |

Hyaluronic acid‐containing emollient cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks (one of either the left or right leg or arm) |

|

Both groups showed significant improvement in all clinical signs and symptoms. However, hyaluronic acid foam significantly improved eczema severity by 2 weeks, while ceramide‐containing cream did not. | Not mentioned |

| 21 | Open‐label RCT (evaluator blinded) | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

39 cases (2–17 years old)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 3 times daily Period: 3 weeks |

Glycyrrhetinic acid‐containing cream moisturizer (commercial product) Dosage: applied 3 times daily Period: 3 weeks |

|

No difference in efficacy was observed among the three groups. The moisturizer (commercial product) was cost‐effective. | Synthetic ceramide |

| 20 | Open‐label RCT | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (moderate‐to‐severe) |

121 cases (48 males/73 females)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 3 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

Fluticasone‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

|

There was no difference in the improvement in itching, sleep habits, and patient/family scores, but fluticasone‐containing cream showed early improvement in SCORAD and IGA. | Not mentioned |

| 25 | Double‐blind RCT (body partitioned) | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

55 cases (27 males/28 females, 37.5 months old)

|

Ceramide‐containing moisturizer Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 8 weeks |

Hydrocortisone‐containing moisturizer Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 8 weeks |

|

The severity was similar with both agents, but the suppression of transepidermal water loss was superior with the ceramide‐containing moisturizer. | Not mentioned |

| 30 | Double‐blind RCT (body partitioned) | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

95 cases (35 males/60 females, 21–51 years old)

|

Ceramide + Mg‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 6 weeks (left or right side) |

Hydrocortisone moisturizer Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 6 weeks (left or right side) |

|

The ceramide‐containing cream had the same degree of improvement as hydrocortisone and was significantly superior to the moisturizer. The ceramide‐containing cream was superior to the hydrocortisone and moisturizer in improving skin hydration. | Ceramide 1, 3, 6II |

| 31 | Open‐label randomized cross‐over trial | 2 | Atopic dermatitis |

27 cases (16 males/11 females, 4.4 years old)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

Moisturizer (commercial product) Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

Efficacy (change in SCORAD score) | Both treatments resulted in improvements, but moisturizers showed better results than the ceramide‐containing cream. | Pseudo‐ceramide |

| 33 | Double‐blind RCT | 2 | Atopic dermatitis (mild‐to‐moderate) |

64 cases (27 males/37 females)

|

Ceramide‐containing moisturizer Dosage: applied 2 times daily Ceramide cleanser Dosage: applied 1 time daily Period: 12 weeks |

Ceramide cleanser Dosage: applied 1 time daily Period: 12 weeks |

|

The moisturizer + cleanser therapy delayed the time to recurrence by ~2 months, and the recurrence rate after 12 weeks was low, resulting in high patient satisfaction. | Ceramide precursor |

| 36 | Double‐blind RCT | 2 | Sebum deficiency |

40 cases (40 females, 23–35 years old)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 12 weeks |

Placebo Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 12 weeks |

|

The ceramide‐containing cream maintained the skin structure and significantly improved both skin surface lipids and skin hydration. | Ceramide 6 |

| 37 | Double‐blind RCT | 2 | Sebum deficiency (xerosis) |

12 cases (3 males/9 females, 32–58 years old) Ceramide‐containing cream Placebo (base cream only) |

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

Placebo Dosage: applied 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

|

Reconstitution of stratum corneum lipids was seen. | Ceramide 3 |

| 39 | Double‐blind RCT | 2 | Sebum deficiency (xerosis) |

39 cases (39 females)

|

Ceramide‐containing cream Dosage: applied at least 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

Placebo Dosage: applied at least 2 times daily Period: 4 weeks |

|

Skin irritation improved quickly with ceramide‐containing cream, accompanied by a significant increase in keratin ceramide levels. | Pseudo‐ceramide |

| 47 | Open‐label RCT | 2 | Hand‐foot skin reaction |

33 cases (26 males/7 females)

|

Ceramide‐containing dressing Dosage: changed every 2–3 days Period: 4 weeks |

Urea‐containing cream Dosage: apply 2–3 times a day Period: 4 weeks |

Percentage of patients with HFSR worsening from grade 1 to grade 2/3 over a period of time | The ceramide‐containing dressing suppressed worsening on the sole of the foot, but there was no difference in the symptoms on both arms. | Not mentioned |

The reports had an LOE ≥ 2 and evaluated the moisturizing/barrier function‐improving effects of ceramide‐containing formulations.

Abbreviations: BSA, percent of body surface area of atopic dermatitis; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; HFSR, hand–foot skin reaction; LOE, Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine level of evidence; PICO, patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome; PRO, patient‐reported outcome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SCORAD, Severity Scoring for Atopic Dermatitis; VAS, visual analog scale.

Marseglia et al. 17 targeted patients with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis. They compared 72 cases in which a ceramide‐containing cream was used (mean age, 6 years) with 35 cases in which a cream base was used (mean age, 5.8 years). They observed an obvious improvement in symptoms among patients who used the ceramide‐containing cream and concluded that the cream was effective for treating mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis.

Sugarman et al. 20 targeted patients with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis. They compared 59 cases in which a ceramide‐containing cream was used (mean age, 8.2 years) with 62 cases in which topical steroids (fluticasone cream) were used (mean age, 7.0 years). Both treatments improved the severity Scoring for Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) and pruritus as well as sleep scores, and the degree of improvement was equivalent.

Wananukul et al. 26 compared ceramide‐containing formulations with topical hydrocortisone in 55 patients with atopic dermatitis (age, 3 months to 14 years). Both formulations were applied to all patients, one on lesions on the right side of the body and the other on lesions on the left side. They found that while symptom improvement was equivalent, ceramide‐containing formulations exhibited a superior moisturizing effect.

The effectiveness of ceramide‐containing formulations has also been demonstrated in xerosis. The three reports we selected 35 , 36 , 37 were all comparisons of ceramide‐containing creams with cream bases. In these studies, ceramide‐containing creams increased the lipid content of the stratum corneum and had a moisturizing effect.

Although only one report was found, the effectiveness of ceramide‐containing formulations in hand–foot syndrome caused by molecular target drugs in cancer patients has also been shown. 47

4. DISCUSSION

Treatment of the stratum corneum with a chemical solvent to remove intercellular lipids of the stratum corneum, including ceramides, reduces stratum corneum water content and increases transepidermal water loss; in other words, it reduces skin barrier function. 10 The decrease in ceramide levels with age 57 causes dryness and wrinkles of the skin 58 and also leads to a decrease in barrier recovery ability. 59 Furthermore, a decrease in lipid content, including ceramides, in the stratum corneum has been reported in psoriasis and xerosis. 60 , 61 Finally, changes in the ratio of stratum corneum ceramide subtypes have been observed in atopic dermatitis, which is known to cause dry skin and decreased barrier function. 62 From the above, it has been concluded that ceramides are a central component of the intercellular lipid matrix and that they play a critical role in moisturizing the skin and maintaining barrier function. 63 , 64

Basic research on various functions of ceramides is also ongoing, Recently, the production pathway of acylceramides, the most important ceramide for skin barrier formation, has been elucidated, 65 and the abnormal production of acylceramides is found to be the cause of ichthyosis. However, systematic review of the literature has not been conducted from clinical viewpoints. Thus, this review collected papers with an LOE of 2 or more that discuss the clinical effects of ceramide‐containing formulations on skin moisture and barrier function. After a two‐round screening process, we narrowed down our selection to 41 papers that reported on RCT and used statistical methods. From among these, we extracted 12 reports using the PICO method.

In comparisons of ceramide‐containing formulations with control moisturizers or placebo formulations, ceramide‐containing formulations exhibited equivalent or better efficacy than comparison products in all studies. Many of these studies evaluated results using severity scores and/or improvement scores, and while the standards for these metrics were established prior to the study, in some cases, evaluations of transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum structure, and stratum corneum morphology were added to increase objectivity. 26 , 30 , 39 In these reports, ceramide‐containing formulations were shown to reduce transepidermal water loss, improve stratum corneum structure, and/or increase stratum corneum lipid content; thus, these reports detail the efficacy of ceramide‐containing formulations. Further, clinical research indicates that, in elderly individuals, topical use of ceramide‐containing formulations of sufficiently high concentration improved hydration and the barrier function of the stratum corneum. 66 Meanwhile, in artificial dry skin, topical use of ceramide‐containing formulations increased stratum corneum water content. 11 It is not clearly described which ceramides are used in all studies (Table 2). In the future, it will be important to investigate the efficacy of different types of ceramides.

This review clearly indicates that there is clinical significance in the topical use of ceramide‐containing formulations in dermatological disorders such as atopic dermatitis. No clinical study indicated any adverse events of note. As far as our qualitative evaluation is concerned, we believe that ceramide‐containing formulations exhibit a certain level of efficacy in improving dry skin and skin barrier function. In the future, double‐blind comparative trials of ceramide‐containing formulations that incorporate a large number of cases are necessary to determine the illnesses and the severity to which the application of ceramides to the skin surface is clinically useful.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Kono T, Miyachi Y, Kawashima M. Clinical significance of the water retention and barrier function‐improving capabilities of ceramide‐containing formulations: A qualitative review. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1807–1816. 10.1111/1346-8138.16175

Funding Information

Non‐Profit Organization Health Institute Research of Skin

[Correction added on 15 October 2021 after first online publication: The Funding Information was added to the article]

REFERENCES

- 1. Cabanillas B, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis and filaggrin. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;42:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoshida K, Yokouchi M, Nagao K, Ishii M, Amagai M, Kubo A. Functional tight junction barrier localizes in the second layer of the stratum granulosum of human epidermis. Dermatol Sci. 2015;77:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Egawa G, Kabashima K. Barrier dysfunction in the skin allergy. Allergol Int. 2018;67:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madison KC. Barrier function of the skin: "La Raison d'Être" of the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christophers E. Cellular architecture of the stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 1971;56:165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Golden GM, Guzek DB, Kennedy AE, McKie JE, Potts RO. Stratum corneum lipid phase transitions and water barrier properties. Biochem. 1987;26:2382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elias PM, Menon GK. Structural and lipid biochemical correlates of the epidermal permeability barrier. Adv Lipid Res. 1991;24:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grubauer G, Feingold KR, Harris RM, Elias PM. Lipid content and lipid type as determinants of the epidermal permeability barrier. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore DJ, Rawlings AV. The chemistry, function and (patho)physiology of stratum corneum barrier ceramides. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39:366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Imokawa G. Structure and function of intercellular lipids in the stratum corneum. Yukagaku. 1995;44:751–66. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imokawa G, Abe A, Jin K, Higaki Y, Kawashima M, Hidano A. Decreased level of ceramides in stratum corneum of atopic dermatitis: AN etiologic factor in atopic dry skin? J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:523–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsutsumi H, Usugi T, Kawano J, Ishida A, Hayashi S. Effect of occlusivity of oil film by the states of oil film on the skin surface. J Soc Cosmet Chem Jpn. 1979;13:37–43. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spada F, Barnes TM, Greive KA. Skin hydration is significantly increased by a cream formulated to mimic the skin's own natural moisturizing systems. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:491–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106:420–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence [Internet]. Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine; 2011 [cited 2021 Apr]. Available from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

- 16. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Alonso‐Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marseglia A, Licari A, Agostinis F, Barcella A, Bonamonte D, Puviani M, et al. Local rhamnosoft, ceramides and L‐isoleucine in atopic eczema: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:271–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draelos ZD. A clinical evaluation of the comparable efficacy of hyaluronic acid‐based foam and ceramide‐containing emulsion cream in the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frankel A, Sohn A, Patel RV, Lebwohl M. Bilateral comparison study of pimecrolimus cream 1% and a ceramide‐hyaluronic acid emollient foam in the treatment of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:666–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sugarman JL, Parish LC. Efficacy of a lipid‐based barrier repair formulation in moderate‐to‐severe pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:1106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller DW, Koch SB, Yentzer BA, Clark AR, O'Neill JR, Fountain J, et al. An over‐the‐counter moisturizer is as clinically effective as, and more cost‐effective than, prescription barrier creams in the treatment of children with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:531–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Draelos ZD. The effect of ceramide‐containing skin care products on eczema resolution duration. Cutis. 2008;81:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berardesca E, Barbareschi M, Veraldi S, Pimpinelli N. Evaluation of efficacy of a skin lipid mixture in patients with irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis or atopic dermatitis: a multicenter study. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuki H, Kiyokane K, Matsuki T, Sato S, Imokawa G. Reevaluation of the importance of barrier dysfunction in the nonlesional dry skin of atopic dermatitis patients through the use of two barrier creams. Exog Dermatol. 2004;3:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kircik LH. Effect of skin barrier emulsion cream vs a conventional moisturizer on transepidermal water loss and corneometry in atopic dermatitis: a pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1482–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wananukul S, Chatproedprai S, Chunharas A, Limpongsanuruk W, Singalavanija S, Nitiyarom R, et al. Randomized, double‐blind, split‐side, comparison study of moisturizer containing licochalcone A and 1% hydrocortisone in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96:1135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamagishi K, Hagiwara K, Tomiyama T, Gasa S, Yamashita T. Effects of topical application of glucosylceramide from tamogitake mushrooms (pleurotus cornucopiae) on skin moisture in patients with atopic dermatitis. J New Rem Clin. 2011;60:630–8. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hata M, Tokura Y, Takigawa M, Tamura Y, Imokawa G. Efficacy of using pseudoceramide‐containing cream for the treatment of atopic dry skin in comparison with urea cream. Nishinihon J Dermatol. 2002;64:606–11. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mizutani H, Takahashi M, Shimizu M, Kariya K, Sato H, Imokawa G. Clinical evaluation of pseudo‐ceramide containing cream for the patients with atopic dermatitis. Nishinihon J Dermatol. 2001;63:457–61. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koppes SA, Charles F, Lammers L, Frings‐Dresen M, Kezic S, Rustemeyer T. Efficacy of a cream containing ceramides and magnesium in the treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double‐blind, emollient‐ and hydrocortisone‐controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee EJ, Suhr KB, Lee JH, Park JK, Jin CY, Youm JK, et al. The clinical efficacy of a multi‐lamellar emulsion containing pseudoceramide in childhood atopic dermatitis: an open crossover study. Ann Dermatol. 2003;15:133–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakamura S, Honma M, Kashiwagi T, Sakai H, Hashimoto Y, Iizuka H. The examination of usefulness and safety of synthesis simulation ceramide cream for the atopic dermatitis. The comparison with the heparinoid inclusion salve. Nishinihon J Dermatol. 1999;61:671–81. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma L, Li P, Tang J, Guo Y, Shen C, Chang J, et al. Prolonging time to flare in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a randomized, investigator‐blinded, controlled, multicenter clinical study of a ceramide‐containing moisturizer. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matsumoto T, Yuasa H, Kai R, Ueda H, Ogura S, Honda Y. Skin capacitance in normal and atopic infants, and effects of moisturizers on atopic skin. J Dermatol. 2007;34:447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weber TM, Kausch M, Rippke F, Schoelermann AM, Filbry AW. Treatment of xerosis with a topical formulation containing glyceryl glucoside, natural moisturizing factors, and ceramide. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:29–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morganti P, Fabrizi G, James B. A new cosmetic solution for a mild to moderate xerosis. J Appl Cosmetol. 1999;17:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Daehnhardt D, Daehnhardt‐Pfeiffer S, Schulte‐Walter J, Neubourg T, Hanisch E, Schmetz C, et al. The influence of two different foam creams on skin barrier repair of foot xerosis: a prospective, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled intra‐individual study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;29:266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Machado M, Bronze MR, Ribeiro H. New cosmetic emulsions for dry skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nojiri H, Ishida K, Yao XQ, Liu W, Imokawa G. Amelioration of lactic acid sensations in sensitive skin by stimulating the barrier function and improving the ceramide profile. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu M, Li X, Chen XY, Xue F, Zheng J. Topical application of a linoleic acid‐ceramide containing moisturizer exhibit therapeutic and preventive benefits for psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kiyohara Y, Mitsui T, Domoto T. The availability and safety of pro's choice hand cream for hand roughening. J Jpn Organ Clin Dermatolog. 2014;31:486–93. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lodén M, Bárány E. Skin‐identical lipids versus petrolatum in the treatment of tape‐stripped and detergent‐perturbed human skin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:412–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kucharekova M, Schalkwijk J, Van De Kerkhof PCM, Van Der Valk PGM. Effect of a lipid‐rich emollient containing ceramide 3 in experimentally induced skin barrier dysfunction. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang HC, Chang TM. Ceramide 1 and ceramide 3 act synergistically on skin hydration and the transepidermal water loss of sodium lauryl sulfate‐irritated skin. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Paepe K, Roseeuw D, Rogiers V. Repair of acetone‐ and sodium lauryl sulphate‐damaged human skin barrier function using topically applied emulsions containing barrier lipids. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:587–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Paepe K, Derde MP, Roseeuw D, Rogiers V. Incorporation of ceramide 3B in dermatocosmetic emulsions: effect on the transepidermal water loss of sodium lauryl sulphate‐damaged skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shinohara N, Nonomura N, Eto M, Kimura G, Minami H, Tokunaga S, et al. A randomized multicenter phase II trial on the efficacy of a hydrocolloid dressing containing ceramide with a low‐friction external surface for hand‐foot skin reaction caused by sorafenib in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:472–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsuboi R, Arai K, Sumida H, Nishio M, Hasebe K, Hiroki Y, Okuda M. Efficacy of an alcohol‐based hand rub containing synthetic pseudo‐ceramide for reducing skin roughness of the hand. Jpn J Environ Infect. 2006;21:73–80. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ishikawa S, Togashi H, Tamura S, Sanada H, Konya C, Kitayama Y, et al. Influence of new skin cleanser containing synthetic pseudo‐ceramide on the surrounding skin of pressure ulcers. Jpn J Pressure Ulcer. 2003;5:508–14. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hao DF, Feng G, Chu WL, Chen ZQ, Li SY. Evaluation of effectiveness of hydrocolloid dressing vs ceramide containing dressing against pressure ulcers. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:936–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cannizzaro MV, Dattola A, Garofalo V, Duca ED, Bianchi L. Reducing the oral isotretinoin skin side effects: efficacy of 8% omega‐ceramides, hydrophilic sugars, 5% niacinamide cream compound in acne patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Okuda M, Yoshiike T, Ogawa H. Detergent‐induced epidermal barrier dysfunction and its prevention. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Byun HJ, Cho KH, Eun HC, Lee M‐J, Lee Y, Lee S, et al. Lipid ingredients in moisturizers can modulate skin responses to UV in barrier‐disrupted human skin in vivo. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65:110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sugita T, Saito S, Nakayama Y, Takada A. A clinical effect of “EYE‐CARE‐CREAM N” on facial wrinkles and the skin elasticity. Med Cons New‐Remed. 2009;46:1203–8. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berger A, Inglese G, Skountrianos G, Karlsmark T, Oguz M. Cost‐effectiveness of a ceramide‐infused skin barrier versus a standard barrier: findings from a long‐term cost‐effectiveness analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2018;45:146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Colwell JC, Pittman J, Raizman R, Salvadalena G. A randomized controlled trial determining variances in ostomy skin conditions and the economic impact (ADVOCATE Trial). J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2018;45:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rogers J, Harding C, Mayo A, Banks J, Rawlings A. Stratum corneum lipids: the effect of ageing and the seasons. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996;288:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Choi JW, Kwon SH, Huh CH, Park KC, Youn SW. The influences of skin viscous‐elasticity, hydration level and aging on the formation of wrinkles: a comprehensive and objective approach. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:e349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Matsumoto M, Umemoto N, Sugiura H, Uehara M. Difference in ceramide composition between "dry" and "normal" skin in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:246–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Motta S, Monti M, Sesana S, Mellesi L, Ghidoni R, Caputo R. Abnormality of water barrier function in psoriasis. Role of ceramide fractions. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:452–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yamanaka M, Hamanaka S, Tsuchida T. Stratum corneum lipid abnormalities in the skin of a patient with senile xerosis. J Dermatol. 2004;114:967–75. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Janssens M, van Smeden J, Gooris GS, Bras W, Portale G, Caspers PJ, et al. Increase in short‐chain ceramides correlates with an altered lipid organization and decreased barrier function in atopic eczema patients. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2755–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Narangifard A, den Hollander L, Wennberg CL, Lundborg M, Lindahl E, Iwai I, et al. Human skin barrier formation takes place via a cubic to lamellar lipid phase transition as analyzed by cryo‐electron microscopy and EM‐simulation. Exp Cell Res. 2018;366:139–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kihara A. Synthesis and degradation pathways, functions, and pathology of ceramides and epidermal acylceramides. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;63:50–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yamamoto H, Hattori M, Chamulitrat W, Ohno Y, Kihara A. Skin permeability barrier formation by the ichthyosis‐causative gene FATP4 through formation of the barrier lipid ω‐O‐acylceramide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:2914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Danby SG, Brown K, Higgs‐Bayliss T, Chittock J, Albenali L, Cork MJ. The effect of an emollient containing urea, ceramide NP, and lactate on skin barrier structure and function in older people with dry skin. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;29:135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]