Abstract

Our previous study demonstrated that phosphodiesterase 8 (PDE8) could work as a potential target for vascular dementia (VaD) using a chemical probe 3a. However, compound 3a is a chiral compound which was obtained by chiral resolution on HPLC, restricting its usage in clinic. Herein, a series of non-chiral 9-benzyl-2-chloro-adenine derivatives were discovered as novel PDE8 inhibitors. Lead 15 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against PDE8A (IC50 = 11 nmol/L), high selectivity over other PDEs, and remarkable drug-like properties (worthy to mention is that its bioavailability was up to 100%). Oral administration of 15 significantly improved the cAMP level of the right brain and exhibited dose-dependent effects on cognitive improvement in a VaD mouse model. Notably, the X-ray crystal structure of the PDE8A–15 complex showed that the potent affinity and high selectivity of 15 might come from the distinctive interactions with H-pocket including T-shaped π–π interactions with Phe785 as well as a unique H-bond network, which have never been observed in other PDE−inhibitor complex before, providing new strategies for the further rational design of novel selective inhibitors against PDE8.

Key words: Phosphodiesterase 8 (PDE8), Vascular dementia, Structure-based drug design, MM-GB/SA, Free energy prediction, Structure–activity relationship, Binding potencies

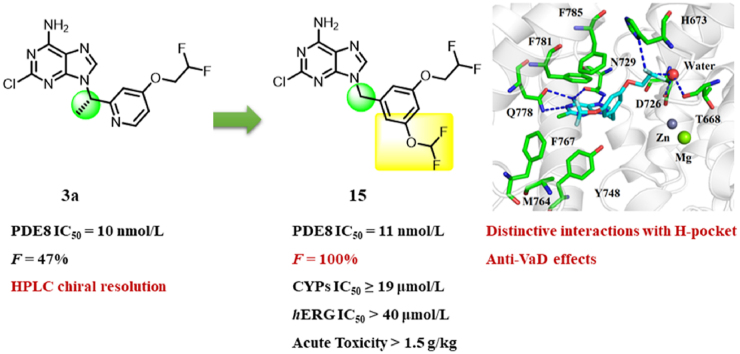

Graphical abstract

Structure-based optimization of 3a resulted in a non-chiral, orally active, and selective PDE8 inhibitor 15via unique interactions with H-pocket, which exhibited remarkable memory improvement effects in VaD mice.

1. Introduction

Vascular dementia (VaD) has been regarded as the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer's disease in the worldwide1. Cerebrovascular disease, ischemic or hemorrhagic brain injury will trigger the cognitive impairment in VaD patients2,3. Risk factors such as age, diabetes, and hypertension are also involved in the pathogenesis of VaD. Thus, the mechanism of VaD is complicated and still unclear. No specific medicine for VaD has been approved so far.

The cAMP/PKA and NO/cGMP/PKG signaling play a considerable role in the memory consolidation and long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission4, 5, 6. The phosphodiesterases (PDEs), a superfamily in charge of hydrolyzing cAMP and cGMP, can be divided into eleven isoforms (PDE1–PDE11)7. The PDE4, PDE7, and PDE8 subtypes specially hydrolyze cAMP whereas the PDE5, PDE6, and PDE9 ones specially hydrolyze cGMP. The other subfamilies hydrolyze cAMP and cGMP, simultaneously. Many PDEs inhibitors could enhance the cognitive abilities in the mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and etc., identifying PDEs as potential targets for memory improvement. For VaD, PDE3 inhibitor cilostazol could attenuated STZ diabetes induced VaD8. Recently, PDE4 inhibitor 4e discovered by our group, showed the cognitive improvement abilities in the VaD mouse model9.

Among all the PDEs, PDE8 showed the highest affinity for the hydrolysis of cAMP10, 11, 12, 13, indicating that PDE8 may be an efficient target for the cAMP-related diseases. However, only a few PDE8 inhibitors have been developed yet14, 15, 16, and most of them are even non-selective, limiting the exploration of the biological functions of PDE8 and the recognition mechanism studies of inhibitors with PDE8. Most recently, our group developed a series of selective PDE8 inhibitors and identified that PDE8 could work as a potential drug target against VaD via a chemical probe 3a17. However, 3a was a chiral compound and was difficultly obtained by chiral resolution on HPLC.

With our continuous interest in the discovery of PDE8 inhibitors, structural optimization of compound 3a was performed in this work (Fig. 1). A non-chiral compound 15 with potent affinity for PDE8 and high selectivity over other PDEs was obtained, which also showed remarkable drug-like properties and considerable memory improvement effects in the unilateral common carotid artery occlusion (UCCAO) mouse model. Notably, the cocrystal structure of 15 bound to PDE8 demonstrated that 15 formed distinctive interactions such as T-shaped π–π interactions with Phe785 and a unique hydrogen bond network with PDE8, which might be the major reason for the potent inhibitory activity of 15 against PDE8 and high selectivity over other PDEs, providing evidence for the further development of PDE8 inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Structural optimization of non-chiral PDE8 inhibitors as anti-VaD agents.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. The process of design novel potent PDE8 inhibitors using X-ray structure

Compared with compound 3a (PDE8A IC50: 10 nmol/L), the non-chiral compound 2c using the hydrogen atom instead of the (S)-methyl group of 3a, only showed an IC50 value of 357 nmol/L against PDE8A17. Another non-chiral compound 10 (Table 1) showed an IC50 value of 117 nmol/L against PDE8A. In order to develop non-chiral PDE8 inhibitors with excellent inhibitory activities, compound 10 was selected as the hit compound, and the cocrystal of the PDE8A–10 complex was obtained and analyzed for the rational design.

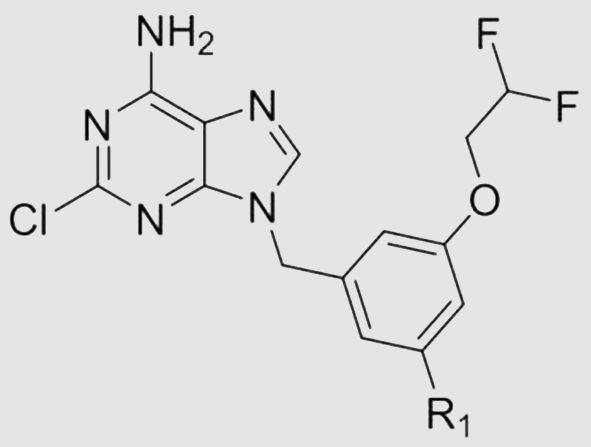

Table 1.

The prediction of binding free energies (ΔGbind, pred), IC50, and metabolic stability RLM t1/2 of target compounds.

| No. | R1 | ΔGbind, pred (kcal/mol) | IC50 (nmol/L)a | RLM t1/2 (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | –H | −33.22 ± 3.46 | 117 ± 6 | – |

| 11 | –F | −35.50 ± 2.31 | 51 ± 3 | – |

| 12 | –OH | −32.14 ± 3.05 | 193 ± 17 | – |

| 13 |  |

−36.52 ± 2.85 | 591 ± 11 | – |

| 14 | −37.27 ± 3.01 | 593 ± 69 | – | |

| 15 |  |

−37.94 ± 2.85 | 11 ± 1 | 169 |

| 16 |  |

−40.93 ± 2.66 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 6 |

| 17 |  |

−39.68 ± 2.66 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 16 |

| 18 |  |

−43.03 ± 2.61 | 20 ± 2 | – |

| 19 |  |

−38.80 ± 2.42 | 40 ± 1 | – |

| 20 | −41.17 ± 2.33 | 52 ± 5 | – | |

| 21 |  |

−37.38 ± 3.02 | 597 ± 61 | – |

| 22 |  |

−43.04 ± 2.53 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 8 |

| 23 |  |

−42.34 ± 3.27 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 39 |

| 24 |  |

−41.24 ± 2.75 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 27 |

| 25 |  |

−39.57 ± 2.78 | 13 ± 2 | – |

Data are given as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3).

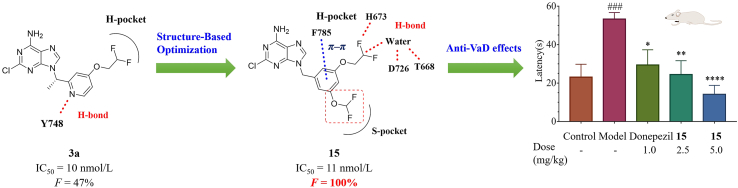

The binding pocket of PDE8 can divide into four subpockets like PDE418 and PDE219, including Q-pocket, M-pocket, S-pocket, and H-pocket (Fig. 2A). The 2-chloroadenine scaffold of 10 bound to Q-pocket, forming a π–π stacking interaction with Phe781 as well as four hydrogen bonds with Gln778 and Asn729. Compared with 3a forming a hydrogen bond with Tyr748, the difluoroethoxyl of 10 stretched deeper in H-pocket and formed a hydrogen bond with His673 instead of Tyr748 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In addition, owing to the strong electron-withdrawing effects of two fluorine atoms, the adjacent C–H tended to perform positive electrostatic potential, and interacted with Asp726 and Thr668 through water-bridged hydrogen bonds. Furthermore, the benzyl of compound 10 formed T-shaped π–π interactions with Phe781 and Phe785. To our knowledge, the hydrogen bond network and T-shaped π–π interactions in H-pocket have never been observed in PDE-inhibitor complex before. We observed that compound 10 mainly occupied Q-pocket and H-pocket, but hardly interacted with S-pocket. Thus, substituents were introduced at the meta-position of benzyl group to occupy S-pocket (Fig. 2B), which might form extra interactions with the adjacent residues Phe785, Met764, Phe767, and Tyr748, enhancing the inhibitory activity of target compounds.

Figure 2.

(A) Surrounding residues of four subpockets represents by four different colors in the PDE8A–10 complex (PDB ID: 7VSL). (B) Rational design of potent PDE8 inhibitors.

To accelerate the process of optimization, a MM-GB/SA approach was adopted to predict binding free energies (ΔGbind, pred) of designed compounds 11–25 with PDE8A (Table 1). Compared with hit 10 (−33.22 ± 3.46 kcal/mol), most designed compounds showed more negative ΔGbind, pred values, except for compound 12 (−32.14 ± 3.05 kcal/mol) with a comparable ΔGbind, pred value.

A PAINS-Remover20 (https://www.cbligand.org/PAINS/) screening was performed to avoid the pan assay interference compounds (PAINS), and all compounds satisfied the filter test and were synthesized.

2.2. Structure–activity relationships (SARs) of target compounds

Compared with the initial hit 10 (IC50 = 117 nmol/L), compound 11 with F atom at the R1 position exhibited a slightly better IC50 value of 51 nmol/L while compound 12 with a hydroxyl group showed a comparable IC50 value of 193 nmol/L against PDE8A. Both compound 13 with a methoxyl group and 14 with an ethoxyl group showed similar inhibitory activities against PDE8A. Compared with 13, 15 with a difluoromethoxyl group demonstrated significant increasement of the inhibitory potency, indicating that fluorine atom is in favor of S-pocket.

After changing the methoxyl group of 13 to substituents with larger volume of isopropyl (16) and isopropoxyl (17), the inhibitory activities against PDE8A were significantly improved. However, further increasing the volume of R1 substituents, such as cyclobutoxyl (18), cyclopropylmethoxyl (19), 2-methoxyethoxyl (20) and benzyloxyl (21), resulted in decreased inhibitory activities against PDE8A. Thus, the steric effect of R1 substituents played an important role when binding S-pocket. Isopropyl and isopropoxyl groups, with appropriate volume, were preferred for binding with S-pocket.

In order to enhance the π–π interactions with Phe781 and Phe785, compounds 22–25 with aromatic heterocycles at the R1 position were designed. As expected, all these compounds showed significantly increased inhibitory activities against PDE8A compared with compound 10. Compounds 22 with 4-pyridinyl, 23 with 3-pyridinyl, and 24 with 2-fluoropyridin-3-yl groups gave the IC50 values of 3.1, 4.8, and 5.9 nmol/L against PDE8A, respectively. Compound 25 with a smaller π-conjugated 2-furyl core afforded a relatively low inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 13 nmol/L against PDE8A.

The predicted binding free energies (ΔGbind, pred) of target compounds were outlined in Table 1. The experimental binding free energies (ΔGbind, exp) were calculated by the IC50 values against PDE8A (ΔGbind, exp ≈ RT lnIC50). A linear correlation achieved (Supporting Information Fig. S2) a considerable Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.68) between ΔGbind, pred and ΔGbind, exp, which demonstrated the MM-GB/SA approach could be efficiently applied to predict the ΔGbind, pred and thus could save the synthesis plus bioassay efforts.

2.3. The evaluation of metabolic stability by the rat liver microsomes (RLM)

The metabolic stability of most potent compounds including 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, and 24 were evaluated by the rat liver microsomes (RLM). Compound 16 with an isopropyl group and compound 17 with an isopropoxyl group gave the t1/2 values of 6 min and 16 min, respectively, revealing that aromatic hydrocarbon and alkyl aryl ether are unstable in the present of RLM. Due to the fluorine atom's blocking effect in metabolic oxidation, compound 15 (R1 = difluoromethoxyl) showed a great metabolic stability (t1/2 = 169 min). Compounds 22, 23, and 24 gave the t1/2 values of 8, 39, and 27 min, respectively, indicating that 3-pyridinyl derivatives are more stable than 4-pyridinyl derivatives. Thus compound 15 was subsequently subjected to other evaluations.

2.4. Remarkable selectivity index of compound 15

The selectivity profile of compound 15 over other PDEs was evaluated and the results are outlined in Table 2. Similar to 3a, compound 15 also exhibited remarkable selectivity index. The selectivities against PDE3A and PDE9A2 were more than 900-fold. Its values of selectivity index against PDE1C, PDE2A, PDE4D2, PDE5A1, PDE7A1, and PDE10A were 562-, 392-, 500-, 437-, 441-, and 111-fold, respectively. These results demonstrated that compound 15 exhibits high selectivity over other PDEs, thus is suitable for the further development as a lead compound.

Table 2.

Selectivity index of 15 against PDE subtypes.

| PDE subtype |

15 |

3a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nmol/L)a | Selectivity index | IC50 (nmol/L)b | Selectivity index | |

| PDE8A1 (480–820) | 11 ± 1 | / | 10 ± 1 | / |

| PDE1C (147–531) | 6179 ± 429 | 562 | 3095 ± 495 | 310 |

| PDE2A (580–919) | 4315 ± 171 | 392 | 2177 ± 104 | 218 |

| PDE3A (679–1087) | >10,000 | >909 | >10,000 | >1000 |

| PDE4D2 (86–413) | 5485 ± 486 | 499 | 7148 ± 340 | 715 |

| PDE5A1 (535–860) | 4835 ± 353 | 440 | >10,000 | >1000 |

| PDE7A1 (130–482) | 4853 ± 359 | 441 | >10,000 | >1000 |

| PDE9A2 (181–506) | >10,000 | >909 | >10,000 | >1000 |

| PDE10A (449–770) | 1224 ± 28 | 111 | 4436 ± 160 | 444 |

Data are given as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3).

Data reported from our previous report17. except the data of PDE1C, which was determined in this research.

2.5. Unique interactions observed in the cocrystal structure of 15 bound to PDE8

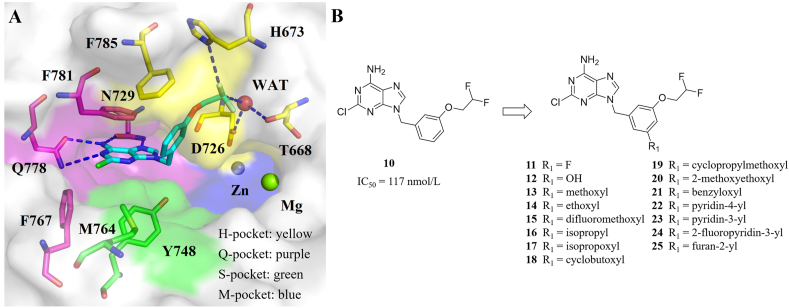

The crystal structures of complexes of PDE8–15, PDE8–17, and PDE8–22 (Fig. 3) were obtained, respectively. These three compounds adopted similar binding modes with PDE8 to hit 10.

Figure 3.

The cocrystal structures of 15, 17, and 22 with PDE8A. (A) The binding pattern of PDE8A-15 complex (PDB ID: 7VTV). 15 is shown as cyan sticks and the key residues are shown as green sticks. (B) Omit Fo−Fc electron density map of 15 at a contour level of 1.0σ. (C) The binding pattern of PDE8A–17 complex (PDB ID: 7VTW). (D) The binding pattern of PDE8A–22 complex (PDB ID: 7VTX).

The 2-chloroadenine core of compound 15 occupied Q-pocket and formed π–π interactions, van der Waals interactions, and H-bond interactions with Q-pocket. Its benzyl motif occupied H-pocket. Furthermore, it maintained the T-shaped π–π interaction with Phe785 and H-bond network (a direct H-bond with His673 and water-bridged hydrogen bonds with Asp726 and Thr668) in H-pocket. As mentioned above, these interactions have never been observed in PDE–inhibitor complex before. The difference between lead 15 and hit 10 is that the difluoromethoxyl group of 15 occupied S-pocket as our designed. Some part of compound 15 even stretched toward the edge of Q-pocket, forming van der Waals interactions plus hydrophobic interactions with Phe781, Phe785, Phe767, Tyr748, and Met764 (the side chain of Met764 is missing when analyzing the crystal structure).

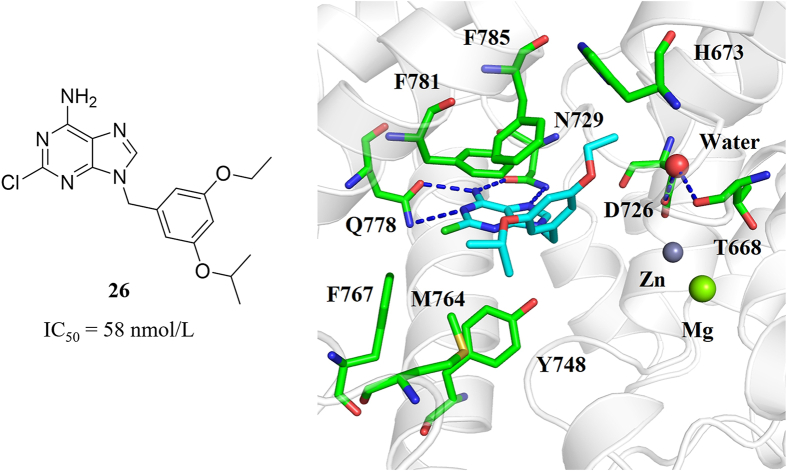

In order to validate the importance of unique H-bond network, we modified the difluoroethoxyl group of 17 (IC50 = 5.0 nmol/L) to an ethoxyl group of 26 (Fig. 4). The IC50 value of 26 dropped to 58 nmol/L, indicating that the H-bond network is in favor of ligand binding. In addition, we found that Phe785 in PDE8 is a unique residue according to the comparison of residues in H-pocket by sequence alignment (Supporting Information Table S1). Only PDE8 includes the residue with aromatic side chain (phenylalanine) at position 785, while other PDEs with alkyl side chains. The unique π–π interaction with Phe785 and H-bond network may account for the high selectivity of 15, providing a novel approach for the discovery of potent PDE8 inhibitors with high selectivity index.

Figure 4.

Compound 26 and its predicted binding mode with PDE8.

2.6. Remarkable drug-like profiles of 15

In terms of the inhibitory activity, selectivity index, and metabolic stability, compound 15 was further subjected to evaluate pharmacokinetic (PK) profile using SD rats (Table 3). After an oral dose of 5.0 mg/kg, 15 exhibited a moderate half-life of 7.92 h and an excellent bioavailability (F) of 100%. The Cmax and AUC(0–∞) of compound 15 were 1560 ng/mL and 23,665 h ng/mL, indicating that 15 had a high level of exposure in vivo. The plasma concentration of compound 15 was still up to 275 ng/mL at 24 h after the oral administration, which was 62 times of its IC50 value.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of 15 in SD rats.

| Parameters | p.o. (5.0 mg/kg) | i.v. (2.5 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (h) | 7.92 ± 0.50 | 5.37 ± 0.86 |

| Tmax (h) | 6.67 ± 2.31 | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 1560 ± 223 | |

| AUC(0–t) (h·ng/mL) | 20,544 ± 2779 | 10,142 ± 635 |

| AUC(0–∞) (h·ng/mL) | 23,665 ± 2970 | 10,611 ± 852 |

| MRT(0–t) (h) | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 7.81 ± 1.18 |

| F (%) | 100 |

We further examined other drug-like profiles of 15, including solubility, human plasma protein binding (PPB), unbound brain concentration, cytochrome P450 (CYP450) inhibition, hERG inhibition, and acute toxicity (Table 4). The human PPB of 15 was 97.6%. The inhibition against CYP450 and hERG were weak, and no acute toxicity was observed for an oral dose of 1.5 g/kg. After an oral dose of 5.0 mg/kg at 4 h in C57BL/6J mice, the brain concentration of 15 in the brain homogenates was 114 ng/g (about 281 nmol/L), which is much higher than the IC50 (11 nmol/L) of 15 and strong enough to active the cAMP signal for memory improvement.

Table 4.

Drug-like profiles of 15.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| clogPa | 3.4 |

| tPSAa | 84 |

| Solubility (pH 7.3)b | 4 μg/mL |

| Human plasma protein binding | 97.6% |

| Unbound brain concentrationc | 114 ng/g |

| Cytochrome P450 inhibition (IC50) | |

| CYP2C19 | 19 μmol/L |

| CYP2C9, 2D6, 1A2 | >25 μmol/L |

| CYP3A4-M, 3A4-T | >50 μmol/L |

| hERG inhibition (IC50) | >40 μmol/L |

| Acute toxicity | >1.5 g/kg |

cLogP and tPSA were predicted by Discovery Studio.

The solubility was tested by HPLC.

After an oral dose of 5.0 mg/kg at 4 h in C57BL/6J mice.

Compared with the PDE8 inhibitors 24 (IC50 = 43 nmol/L) reported by Pfizer15,16, lead 15 achieved the excellent and higher inhibitory activity (IC50 = 11 nmol/L) against PDE8A and high selectivity over other PDEs. In addition, the pharmacokinetic profiles such as oral bioavailability and metabolic stability have been also improved. Furthermore, lead 15 had considerable brain penetrability and physicochemical properties (tPSA: 84, clogP: 3.4), which is more suitable to be developed for the CNS diseases.

2.7. Significant therapeutic effects in VaD mice

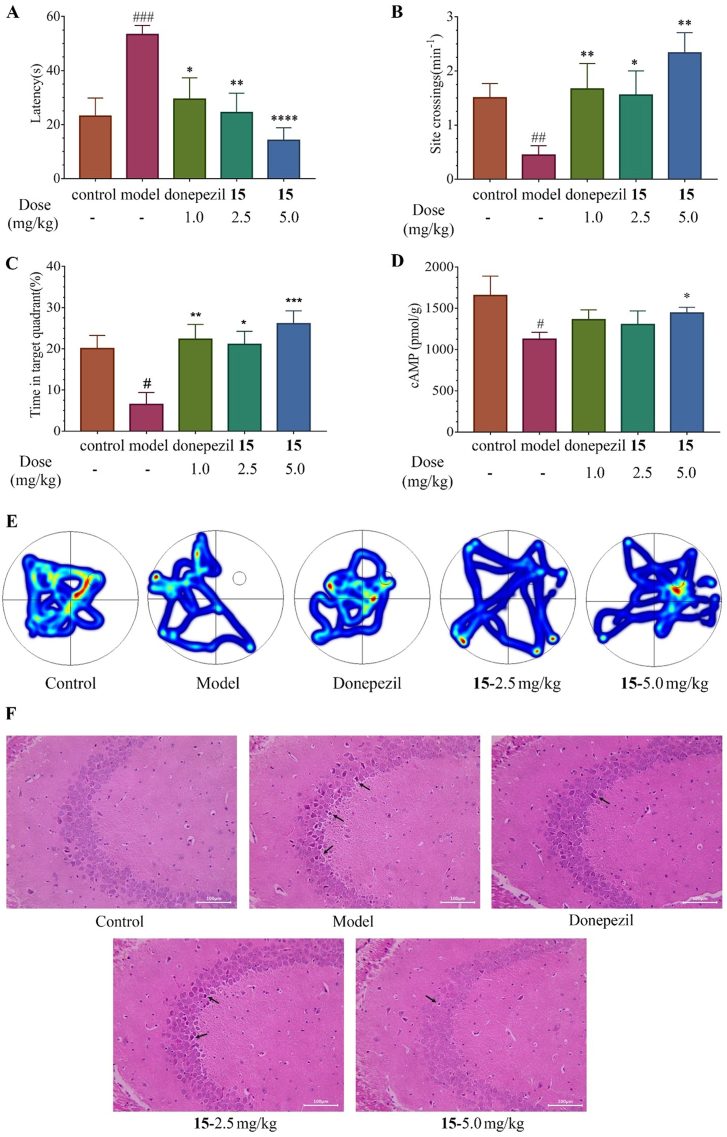

It is well demonstrated that mice treated with permanent UCCAO would lead to chronic hypoperfusion and ischemic injury including ischemic white matter (WM) lesions and lacunes21,22. Thus, a VaD mouse model with the right common carotid artery occlusion was adopted. After treatment with vehicle, compound 15 (2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg, p.o.) and donepezil (1.0 mg/kg, p.o.) for 3 weeks, respectively, the learning and memory ability was evaluated by Morris water maze (MWM) test. After removing the platform on the spatial probe trial day, the trajectories of each mouse were recorded, and the escape latency time (ELT) to find the platform site of each mouse, the number of the platform site crossings, and residence time in the target quadrant were analyzed.

As shown in Fig. 5, the ELT of the model group significantly increased in comparison with the control group. Meanwhile, the number of the platform site crossings was notably decreased compared with the control group and the identical trend was observed in residence time in the target quadrant, which strongly demonstrated that the cognitive impairment occurred in UCCAO-treated mice and the VaD mouse model was built successfully.

Figure 5.

The cognitive impairment of UCCAO mice has been improved after orally administration with compound 15 at the doses of 2.5 mg/kg and 5.0 mg/kg. (A) Escape latency time of mice (s). (B) Site crossings (min−1). (C) Time in the target quadrant (%). (D) cAMP levels of the right brain in mouse (pmol/g). (E) Image is representative trajectories from each group. (F) Representative images of each group with hematoxylin and eosin straining in hippocampal CA3 region (HE, × 200). Donepezil at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg was probed as a positive control. Scale bar: 100 μm. Data are represented as mean values ± SEM (n = 8–12 in each group). #P < 0.05 vs control; ##P < 0.01 vs control; ###P < 0.001 vs control; ∗P < 0.05 vs model; ∗∗P < 0.01 vs model; ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs model; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs model, respectively.

Compared with the model group, oral administration with compound 15 at the dose of 2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg as well as the positive control donepezil at the dose of 1.0 mg/kg markedly decreased the ELT after the platform was removed in the spatial probe trial day. Furthermore, a significant increase was observed in the number of the platform site crossings in 15-treated and donepezil-treated mice and the similar trend came to the residence time in the target quadrant. These results indicated that learning and memory functions had been improved in those mice. Besides, oral administration of 15 at 5.0 mg/kg daily showed a better ELT than that of 2.5 mg/kg. Consistently, the same dose responses in their therapeutic effects were observed on the number of the platform site crossings and residence time in the target quadrant. We also measured the concentration of cAMP in the right brain of all groups (Fig. 5D). Brain tissue cAMP levels of the model group were significantly decreased in comparison with the control group. Meanwhile, both low and high dose of 15 treatments upregulated the level of cAMP.

The histological changes were observed using the HE staining method. Compared with the control group with hippocampus neurons tightly arranged in a rounded shape and clear nucleolus, the neurons in model groups were shrunken or lost with scattered arrangement. The treatment of 15 clearly reduced the shrunken or irregular neurons and decreased the neurons loss as the positive control donepezil. All these results suggested that lead 15 showed notable therapeutic effects on cognitive impairment improvement and efficiently improved the spatial learning and memory ability in VaD mouse model, which identified lead 15 as a novel PDE8 inhibitor for VaD treatment.

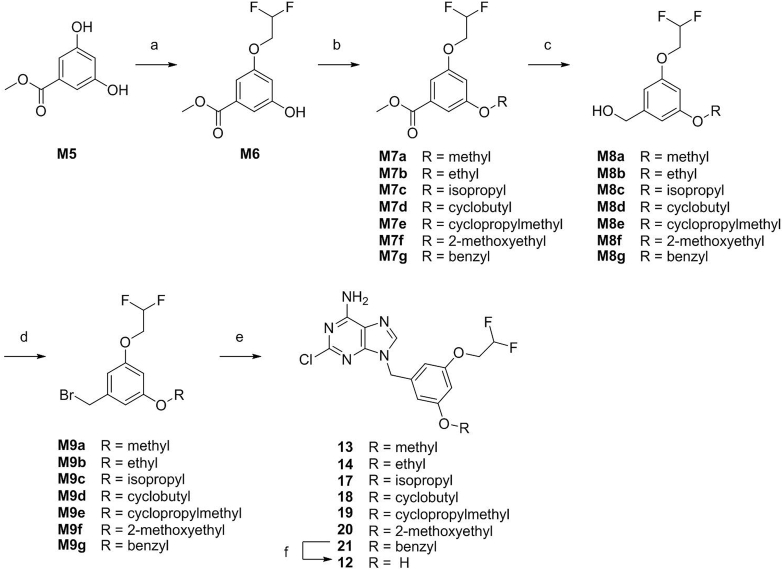

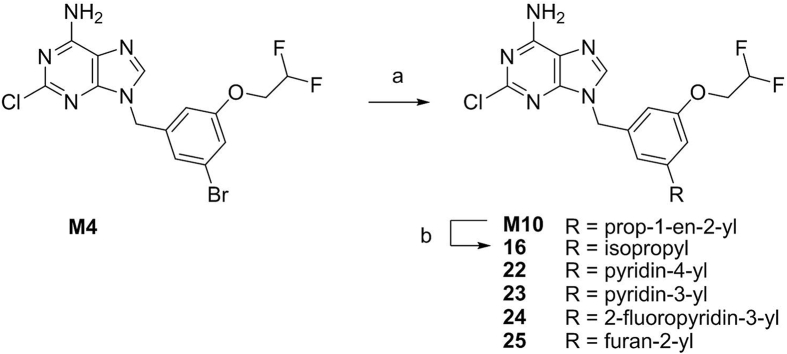

2.8. Chemistry

The synthetic routes for target compounds are depicted in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 4. The key intermediate M4 was synthesized by a process starting from the substitution of 3-bromo-5-methylphenol (M1a) with 2-bromo-1,1-difluoroethane, followed by Wohl–Ziegler bromination23,24 and then coupling to 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine using cesium carbonate. Intermediate M4 was treated with Pd-C/H2 to give 10. The synthesis of compound 11 was similar to that of M4 using 3-fluoro-5-methylphenol as starting material (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for compounds 10 and 11. Reagents and conditions: (a) 2-bromo-1,1-difluoroethane, cesium carbonate, acetonitrile, reflux, overnight; (b) N-bromosuccinimide, azodiisobutyronitrile, carbon tetrachloride, reflux, 4 h; (c) 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine, cesium carbonate, N,N-dimethylformamide, 70 °C, overnight; (d) Pd/C, H2, methanol/tetrahydrofuran, r.t., overnight.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic route for compounds 12–14 and 17–21. Reagents and conditions: (a) 2-bromo-1,1-difluoroethane, potassium iodide, potassium carbonate, acetonitrile, reflux, overnight; (b) alkyl bromides or benzyl bromide, cesium carbonate, acetonitrile, reflux, overnight; (c) lithium aluminum hydride, tetrahydrofuran, r.t., 4 h; (d) phosphorus tribromide, dichloromethane, 0 °C to r.t., 4 h; (e) 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine, cesium carbonate, N,N-dimethylformamide, 70 °C, overnight; (f) Pd/C, H2, methanol/tetrahydrofuran, r.t., overnight.

Scheme 3.

Synthetic route for compounds 16 and 22–25. Reagents and conditions: (a) aromatic boric acids or pinacol vinylboronate, [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II), potassium carbonate, 1,4-dioxane/water, 100 °C, overnight; (b) Pd/C, H2, methanol/tetrahydrofuran, r.t., overnight.

Scheme 4.

Synthetic route for compound 15. Reagents and conditions: (a) potassium hydroxide, acetonitrile/water, 1 h; (b) 2-bromo-1,1-difluoroethane, cesium carbonate, acetonitrile, reflux, overnight; (c) N-bromosuccinimide, azodiisobutyronitrile, carbon tetrachloride, reflux, 4 h; (d) 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine, cesium carbonate, N,N-dimethylformamide, 70 °C, overnight.

For the preparation of compounds 12–14 and 17–21 (Scheme 2), methyl 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate (M5) was substituted by 2-bromo-1,1-difluoroethane, followed by substitution with corresponding alkyl bromides or benzyl bromide to give M7a−g. The esters M7a−g were reduced using lithium aluminum hydride to yield alcohols M8a−g. The alcohols M8a−g were brominated using phosphorus tribromide to give benzyl bromide derivatives M9a−g, followed by coupling to 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine using cesium carbonate to produce target compounds 13–14 and 17–21. Reduction of compound 21 with H2 and Pd/C as a catalyst gave compound 12.

As shown in Scheme 3, compounds M10 and 22–25 were synthesized by Suzuki coupling25 of intermediate M4 with aromatic boric acids or pinacol vinylboronate in the presence of potassium carbonate as a base and Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 as a catalyst. Then, reaction of M10 with H2 and Pd/C produced compound 16.

The synthesis of compound 15 is shown in Scheme 4. The starting material 5-methylbenzene-1,3-diol (M11) was subjected to difluoromethylation, difluoroethylation, bromination and coupling to 2-chloro-9H-purin-6-amine to obtain compound 15.

3. Conclusions

Herein, we performed structure-based optimization on compound 3a, affording a series of non-chiral PDE8 inhibitors. Lead 15 showed potent inhibitory activity against PDE8A (IC50 = 11 nmol/L) and high selectivity profile against other PDE isoforms. The cocrystal structure of PDE8-15 revealed a novel binding pattern including a T-shaped π–π interaction with Phe785 and hydrogen bond network with H-pocket, providing new evidences to design highly selective PDE8 inhibitors. In addition, lead 15 exhibited remarkable drug-like properties like a bioavailability of 100% and its oral administration improved the cAMP level of the right brain, and exhibited dose-dependent effects on the improvement of spatial learning and memory capability in VaD mouse model.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

The synthetic routes and characterization data of target compounds were provided in Supporting Information.

4.2. Molecular modeling

The cocrystal structure of the PDE8–10 complex (PDB ID: 7VSL) was chosen for molecular modeling. All target compounds were directly constructed on the basis of the conformation of 10 bound to PDE8. The procedures for molecular dynamics (MD) simulation were same as our previous studies26,27. For each protein-ligand system, 8 ns MD simulations were carried out by NPT ensemble with pressure of 1 atm and temperature of 300 K under periodic boundary conditions. The bonds with hydrogen atoms were restrained by SHAKE algorithm so that the time step was set to two fs28,29. The long-range electrostatic interactions was treated by the partial mesh Ewald (PME) method with a cutoff of 8 Å30,31. After 8 ns MD simulation, the binding free energy was predicted by the MM-GB/SA approach32, 33, 34 in Amber 2035 suite using 100 snapshots from 7 to 8 ns trajectory.

4.3. Protein expression and purification

The PDE8A protein was expressed and purified by the previously reported protocols17. E. coli BL21 (Codonplus, DE3) cells harboring the recombinant pET15b-PDE8A1 plasmid (480–820)36,37 were cultured in 2 × YT medium at 37 °C until OD600 = 0.6–0.8, followed by induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.1 mmol/L) at 25 °C for one day. The pellet was denatured in guanidine (7.8 mmol/L) and Tris-HCl (0.1 mmol/L, pH 8.0) for 12 h, and then purified by the nickel nitriloacetic acid (Ni-NTA) column (Qiagen). The elution was added dropwise into the refolding buffer and carried out without swinging at 4 °C for 72 h, followed by purification using hydroxyapatite HTP GEL (Bio-Rad), Q-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and a gel filtration column Sephacryl S100 (GE Healthcare).

Other PDE isoforms were expressed and purified by similar procedures without denaturing and refolding process as our previous papers9,17,27,38, 39, 40, 41.

4.4. Bioassay test and crystallization

3H-cAMP, the substrate for PDE8A, was diluted with the buffer containing Tris-HCl (20 mmol/L, pH 7.5), manganese chloride (10 mmol/L), and dithiothreitol (1 mmol/L) to about 20,000 cpm per assay. The mixture was reacted at 25 °C for 15 min and then terminated by adding zinc sulphate, following by barium hydroxide. The radioactivity of unreacted 3H-cAMP in the supernatant was tested by a PerkinElmer 2910 liquid scintillation counter. The IC50 was fitted by nonlinear regression using at least eight different concentrations. Each test was measured at least three times.

Same procedures for crystallization were performed as previous report9,17,38, 39, 40. And the details of diffraction data and structure refinement statistic were given in Supporting Information Table S2.

4.5. Drug-like profiles determinations

The procedures for the determination of RLM stability, PK properties, human PPB, CYP450 inhibition, hERG inhibition, and acute toxicity were same as our previous studies17,38, 39, 40.

4.6. UCCAO mouse model and Morris water maze test

The similar experiments (Supporting Information) have been performed as our previously reported protocols9,17. All animal care and experimental protocols were in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Institutes of Health Publication, revised 1996, No. 86-23, Bethesda, MD) and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee for Animal Research of Sun Yat-sen University (IACUC number: SYSU-IACUC-2021-000129).

4.7. cAMP concentration assay

The mice’ brains were quickly removed, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C before tested. The competitive enzyme immunoassay was used to measure the cAMP levels (ADI-900-163, Enzo Life Sciences, Exeter, UK). Brain tissue homogenized in 0.1 mol/L HCl with 10 volumes. After centrifuge for 10 min, the supernatant was diluted to 5 times with 0.1 mol/L HCl and then tested by non-acetylated protocol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (21877134, 22077143, 81903542,and 21977127), Science Foundation of Guangzhou City (201904020023, China), Fundamental Research Funds for Hainan University (KYQD(ZR)-21031, China), Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515011883, China), Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2017BT01Y093, China),and Guangdong Province Higher Vocational Colleges & Schools Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2016, China). We cordially thank Prof. Hengming Ke from Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, for his assistance with the molecular cloning, expression, purification, determination of the crystal structures, and bioassay of PDEs.

Author contributions

Xu-Nian Wu and Qian Zhou contributed equally to this work, lead the research, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Ya-Dan Huang and Xi Xie performed the biological tests. Zhe Li performed molecular docking and dynamic simulation calculations. Yinuo Wu and Hai-Bin Luo supervised the entire research with conceptualization, analysis and resources.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.012.

Contributor Information

Yinuo Wu, Email: wyinuo3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Hai-Bin Luo, Email: hbluo@hainanu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.O'Brien J.T., Thomas A. Vascular dementia. Lancet. 2015;386:1698–1706. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalaria R.N. Neuropathological diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia with implications for Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:659–685. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1571-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw J.M., Smith C., Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483–497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abel T., Nguyen P.V., Barad M., Deuel T.A., Kandel E.R., Bourtchouladze R. Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell. 1997;88:615–626. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitolo O.V., Sant'Angelo A., Costanzo V., Battaglia F., Arancio O., Shelanski M. Amyloid beta-peptide inhibition of the PKA/CREB pathway and long-term potentiation: reversibility by drugs that enhance cAMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13217–13221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172504199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan M.M., Ryan B., Kyrke-Smith M., Logan B., Tate W.P., Abraham W.C. Temporal profiling of gene networks associated with the late phase of long-term potentiation in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beavo J.A. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: functional implications of multiple isoforms. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:725–748. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A., Kumar A., Jaggi A.S., Singh N. Efficacy of cilostazol a selective phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor in rat model of streptozotocin diabetes induced vascular dementia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;135:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang J., Huang Y.Y., Zhou Q., Gao Y., Li Z., Wu D., et al. Discovery and optimization of α-mangostin derivatives as novel PDE4 inhibitors for the treatment of vascular dementia. J Med Chem. 2020;63:3370–3380. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakics V., Karran E.H., Boess F.G. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soderling S.H., Bayuga S.J., Beavo J.A. Cloning and characterization of a cAMP-specific cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8991–8996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamanuma M., Yuasa K., Sasaki T., Sakurai N., Kotera J., Omori K. Comparison of enzymatic characterization and gene organization of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 8 family in humans. Cell Signal. 2003;15:565–574. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher D.A., Smith J.F., Pillar J.S., St Denis S.H., Cheng J.B. Isolation and characterization of PDE8A, a novel human cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:570–577. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demirbas D., Wyman A.R., Shimizu-Albergine M., Cakici O., Beavo J.A., Hoffman C.S. A yeast-based chemical screen identifies a PDE inhibitor that elevates steroidogenesis in mouse leydig cells via PDE8 and PDE4 inhibition. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeNinno M.P., Wright S.W., Visser M.S., Etienne J.B., Moore D.E., Olson T.V., et al. 1,5-Substituted nipecotic amides: selective PDE8 inhibitors displaying diastereomer-dependent microsomal stability. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:3095–3098. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeNinno M.P., Wright S.W., Etienne J.B., Olson T.V., Rocke B.N., Corbett J.W., et al. Discovery of triazolopyrimidine-based PDE8B inhibitors: exceptionally ligand-efficient and lipophilic ligand-efficient compounds for the treatment of diabetes. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:5721–5726. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Y., Wu X.N., Zhou Q., Wu Y., Zheng D., Li Z., et al. Rational design of 2-chloroadeninederivatives as highly selective phosphodiesterase 8A inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2020;63:15852–15863. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Card G.L., England B.P., Suzuki Y., Fong D., Powell B., Lee B., et al. Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure. 2004;12:2233–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J., Yang Q., Dai D., Huang Q. X-ray crystal structure of phosphodiesterase 2 in complex with a highly selective, nanomolar inhibitor reveals a binding-induced pocket important for selectivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11708–11711. doi: 10.1021/ja404449g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baell J.B., Holloway G.A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshizaki K., Adachi K., Kataoka S., Watanabe A., Tabira T., Takahashi K., et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induced by right unilateral common carotid artery occlusion causes delayed white matter lesions and cognitive impairment in adult mice. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y., Gu J.H., Dai C.L., Liu Q., Iqbal K., Liu F., et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion causes decrease of O-GlcNAcylation, hyperphosphorylation of tau and behavioral deficits in mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:10. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohl A. Bromierung ungesättigter Verbindungen mit N-Brom-acetamid, ein Beitrag zur Lehre vom Verlauf chemischer Vorgänge. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1919;52:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziegler K., Schenck G., Krockow E.W., Siebert A., Wenz A., Weber H. Die synthese des cantharidins. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1942;551:1–79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyaura N., Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z., Lu X., Feng L.J., Gu Y., Li X., Wu Y., et al. Molecular dynamics-based discovery of novel phosphodiesterase-9A inhibitors with non-pyrazolopyrimidinone scaffolds. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:115–125. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00389f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X.N., Huang Y.D., Li J.X., Yu Y.F., Zhou Q., Zhang C., et al. Structure-based design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel pyrimidinone derivatives as PDE9 inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. SETTLE: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of N-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N.log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou T.J., Wang J.M., Li Y.Y., Wang W. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:69–82. doi: 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L., Sun H., Li Y., Wang J., Hou T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 3. The impact of force fields and ligand charge models. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:8408–8421. doi: 10.1021/jp404160y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massova I., Kollman P.A. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspect Drug Discov. 2000;18:113–135. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Case D.A., Aktulga H.M., Belfon K., Ben-Shalom I.Y., Brozell S.R., Cerutti D.S., et al. University of California; San Francisco: 2021. Amber 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H., Yan Z., Yang S., Cai J., Robinson H., Ke H. Kinetic and structural studies of phosphodiesterase-8A and implication on the inhibitor selectivity. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12760–12768. doi: 10.1021/bi801487x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan Z., Wang H., Cai J., Ke H. Refolding and kinetic characterization of the phosphodiesterase-8A catalytic domain. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;64:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y., Tian Y.J., Le M.L., Zhang S.R., Zhang C., Huang M.X., et al. Discovery of novel selective and orally bioavailable phosphodiesterase-1 inhibitors for the efficient treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Chem. 2020;63:7867–7879. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D., Huang Y., Chen Y., Huang Y.Y., Geng H., Zhang T., et al. Optimization of chromeno[2,3-c]pyrrol-9(2H)-ones as highly potent, selective, and orally bioavailable PDE5 inhibitors: structure–activity relationship, X-ray crystal structure, and pharmacodynamic effect on pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Med Chem. 2018;61:8468–8473. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y., Zhang S., Zhou Q., Zhang C., Gao Y., Wang H., et al. Discovery of highly selective and orally available benzimidazole-based phosphodiesterase 10 inhibitors with improved solubility and pharmacokinetic properties for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2339–2347. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H., Liu Y., Chen Y., Robinson H., Ke H. Multiple elements jointly determine inhibitor selectivity of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases 4 and 7. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30949–30955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.