Abstract

The proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) technology has been rapidly developed since its birth in 2001, attracting rapidly growing attention of scientific institutes and pharmaceutical companies. At present, a variety of small molecule PROTACs have entered the clinical trial. However, as small molecule PROTACs flourish, non-small molecule PROTACs (NSM-PROTACs) such as peptide PROTACs, nucleic acid PROTACs and antibody PROTACs have also advanced considerably over recent years, exhibiting the unique characters beyond the small molecule PROTACs. Here, we briefly introduce the types of NSM-PROTACs, describe the advantages of NSM-PROTACs, and summarize the development of NSM-PROTACs so far in detail. We hope this article could not only provide useful insights into NSM-PROTACs, but also expand the research interest of NSM-PROTACs.

Key words: Non-small molecule PROTACs, Protein degradation, Peptide PROTACs, Nucleic acid PROTACs, Antibody PROTACs

Graphical abstract

In recent years, many non-small molecule PROTACs (NSM-PROTACs) have been developed, providing many new ideas and methods in the field of protein degradation.

1. Introduction

After drug design enters the era of molecular targeting, selective regulation of disease-causing proteins to treat and study diseases has always been the goal of the most researchers1. Obviously, small molecule inhibitors are the first to be used, which mainly block the function of the target protein through protein–ligand binding2. This mode of action is called “occupancy driven”3,4. However, many target proteins do not have clear binding pockets, making small molecule inhibitors helpless, and “undruggable” proteins have become synonymous with them5,6. Under this circumstance, technologies such as small interfering RNA (siRNA) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) have emerged to overcome the bottleneck of drug discovery7,8. However, the obvious potential side effects and the difficulty in the delivery of macromolecular drugs have become the main constraints for the development of these technologies9. In 2001, Sakamoto et al.10 achieved the degradation of methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2) for the first time through the proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) technology, which officially entered the field of vision of scientific researchers. This pioneer practice not only opened up a new path for the targeting of undruggable proteins, but also laid a theoretical foundation for the development of PROTACs.

The design of PROTACs is based on the ubiquitin‒proteasome system (UPS), a protein degradation mechanism widely present in cells11. This system can degrade waste proteins by 26S proteasome after being labeled with ubiquitin, thereby ensuring the maintenance of cell homeostasis12,13. PROTACs are a three-part heterobifunctional molecule, in which two ligands are combined with E3 ubiquitin ligase and protein of interest (POI) respectively, and the linker is responsible for connecting the two ligands and pulling them closer together (Fig. 1A)14,15. Furthermore, the overall PROTACs can artificially hijack the ubiquitin–proteasome system by forming a stable ternary complex with E3 ubiquitin ligase and POI, and then make the POI undergo sufficient ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome16, 17, 18, 19. Different from traditional small molecules, the POI degradation profile of PROTACs is dependent on the proximity-induced interactions between the E3 ubiquitin ligase and POI20,21. Therefore, researchers call the mode of action of PROTACs “event-driven”22,23. This mode of action does not require the high affinity between PROTACs and POI to be effective. Consequently, it makes possible for targeting many undruggable proteins24. In addition, PROTACs do not disappear after the primary degradation and can be reengaged in degradation25,26. Benefiting from this catalysis mechanism, PROTACs can exert degradative activity with substoichiometry, reducing toxic side effects and possibly improving safety profile27,28.

Figure 1.

(A) Protein degradation mechanism mediated by PROTACs; (B) In RTK activated cells, degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by phosphoPROTACs.

At present, a variety of small molecule PROTACs targeting several targets have entered clinical trials (Supporting Information Table S1)29. Especially, ARV-110 and ARV-471 still showed favorable pharmacokinetic profiles without conforming to Lipinski's rule of five and successfully entered phase 2 clinical trail30,31.

However, small molecule PROTACs also have certain disadvantages in targeted protein degradation, such as insufficiency of available POI ligand, adverse reactions, and difficulty in synthesis32,33. The emergence of non-small molecule PROTACs such as peptide PROTACs and nucleic acid PROTACs fills up the above-mentioned unmined fields, expanding the application range of PROTACs technology (Table 1). This article focusing on the development of NSM-PROTACs so far, will briefly categorize the published NSM-PROTACs, summarize their advantages, and discuss the future development of NSM-PROTACs. We hope to give researchers in the field of protein degradation a clearer understanding of NSM-PROTACs.

Table 1.

Components, advantages and disadvantages of NSM-PROTACs.

| PROTAC | POI ligand | E3 ligand | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecule PROTACs | Small molecule | Small molecule | High stability32/good membrane permeability34 | Limitation of degradation of all pathogenic proteins35/many adverse reactions |

| Peptide PROTACs | Peptide or small molecule | Peptide | Target more undruggable protein/easy to design and synthesis36/high specificity37/low toxicity38 | Poor DMPK profile39/instability40/potential immunogenicity41 |

| Nucleic acid PROTACsa | Nucleic acid | Small molecule | Ability to any degrade transcription factor in theory42 | Instability40/only degrade nucleic acid-binding proteins |

| Antibody PROTACsb | Antibody | Antibody | Ability to degrade membrane protein32 | High cost/instability40/potential immunogenicity43 |

Excluding aptamer–PROTAC conjugates.

Excluding antibody–PROTAC conjugates.

2. Peptide PROTACs

Peptide PROTAC is the earliest form of PROTACs. However, given the poor DMPK profile of peptides, small molecule PROTACs are preferred44. After the E3 ubiquitin ligases such as von Hippel Lindau (VHL), cereblon (CRBN) and Kelch-like ECH-related protein 1 (Keap1) were successively hijacked by small molecule ligands (Supporting Information Table S2), the pace of development of small molecule PROTACs has accelerated significantly45. But peptide PROTACs are still advancing, and notably, a variety of peptide ligands of E3 ubiquitin ligase have been used in the development of PROTACs (Table 2), and their high affinity and specificity have been widely confirmed.

Table 2.

Ligand of POI and E3 ubiquitin ligase for peptide PROTACs.

| POI or E3ligase | Sequence | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POI | ER |

|

57,58 |

| Akt |  |

59 | |

| CREPT | VRALKQKYEELKKEKESLVDK | 60 | |

| Tau | YQQYQDATADEQG | 61,62 | |

| α-Synclein | GVLYVGSKTR | 63,64 | |

| β-Catenin | 65 | ||

| PI3K | GPGGDYAAMGACPASEQGYEEMRA | 66 | |

| FRS2α | IENPQYFSDA | 66 | |

| X-protein | LCLRPVGAESRGRPVSGPFG | 67 | |

| E3 ligase | VHL | ALAPYIP LAP(OH)YI |

57,67,68 |

| Keap1 | LDPETGEYL | 61,69 | |

| SCFβ-TRCP | DRHDS(p)GLDS(p)M | 10 |

2.1. Advantages of peptide PROTACs

At present, most PROTACs use small molecules as target warheads, which depend to a large extent on the binding pocket of the target protein40,46. With the rapid development of structural biology, it is convenient to obtain peptides with high affinity to target protein epitopes36. In fact, peptide ligands are less difficult to develop relative to small molecules, mainly because it does not rely on traditional trial and error methods such as high-throughput screening47. In short, researchers can obtain the sequence of protein epitope mimics by analyzing the key residues of protein interactions and then synthesize the peptide ligands of the target protein according to the sequence48. At present, many targets that cannot be targeted by small molecules are degraded by peptide PROTACs (Table 2). Another way to develop targeting peptides with high affinity for POI is to use phage display and yeast display technologies49,50,which can find hundreds of target-specific peptides51,52. More importantly, these technologies do not rely on protein crystal complexes, and can obtain d-configuration peptide targeting warheads, which can avoid the easily degradable characteristics of peptide ligands in the body53. Relying on this kind of technology, the peptide ligands of E3 ubiquitin ligase and POI can be found more quickly54. In general, peptide PROTACs can enable the exploration of the conventional undruggable proteins more easily55,56.

On the other hand, peptide PROTACs could have an innate safety profile. In terms of approved peptide drugs, they have high biological activity and high specificity. Because the degradation products in the body are amino acids, which do not easily accumulate in specific tissues and organs, the toxic reaction is relatively weak. The binding interaction with the target protein could be strong and selective, ensuring the minimal non target adverse reactions38,70,71. Peptide PROTACs may inherit the excellent pharmacological and toxicological properties of available peptide drugs.

2.2. Development of peptide PROTACs

2.2.1. Methionine aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2)

The PROTACs technology first appeared in the sight of scientific researchers in the form of peptide complexes41. Sakamoto et al.10 used the phosphopeptide of IκBα to recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex SCFβ-TRCP, and used the MetAP2 covalent inhibitor ovalicin (OVA) as the POI ligand to design and synthesize the first protein targeting chimeric molecule Protac-1. By adding this PROTAC molecule to the extracts from unfertilized Xenopus laevis eggs, the degradation of MetAP2 was observed, and this result verified the feasibility of this technology.

2.2.2. Androgen (AR) and estrogen receptor (ER)

In 2003, in order to expand the scope of the target application of PROTACs, Sakamoto et al.72 replaced OVA with dihydrotestosterone and estradiol. It is well known that dihydrotestosterone and estradiol can specifically bind to AR and ER, respectively73,74. After injection of these modified PROTACs molecules into cells, ubiquitination and degradation of AR and ER were observed.

In 2016, Zhao et al.75 used an N-terminal aspartate crosslinking strategy to design an ER peptide modulator (TD-PERMs) with stable helix structure and excellent stability in serum, cell penetration, and cell viability. On this basis, they linked TD-PERMs with the peptide ligand of E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL to construct a novel ER-targeted TD-PROTAC57. Subsequent experiments proved that TD-PROTAC selectively induces the ubiquitination and degradation of ERα through a protease-dependent pathway (DC50 < 20 μmol/L in T47D cells), while the control peptide cannot degrade ERα. TD-PROTAC can reduce the transcription of ERα-related genes, inhibit the proliferation of ERα-positive cancer cells, promote their apoptosis, and have negligible cytotoxicity to ERα-negative cells. In addition, in vivo experiments showed that TD-PROTAC caused tumor regression in the MCF-7 mouse xenograft model. It is worth noting that, unlike the small molecule PROTACs that degrade ER, the TD-PROTAC binds to the coactivator binding site of ER, which may develop into a treatment method for breast cancer at different stages76.

In 2019, Dai et al.58 developed a peptide PROTAC that degrades ER with a strategy similar to the former. The only difference was that some amino acids in the side chain of the cyclic peptide were replaced with neopentyl glycine (Npg). This modification of cyclic peptides γ-methyl group may constrain the helical conformation77. The subsequent experimental results showed that the optimized compound I-6 showed strong antiproliferative activity (IC50 = 9.7 μmol/L in MCF-7 cells), high cell uptake and pro-apoptotic effect on ERα-positive cancer cells. Meanwhile, ERα degradation in a ubiquitin proteasome dependent manner was observed in ERα-positive MCF-7 cells. Finally, I-6 showed excellent antitumor activity in vivo in tumor bearing mice model with 4-T1 cells.

2.2.3. FKBP12

In 2004, Schneekloth et al.68 achieved for the first time the application of PROTACs technology to degrade target proteins in living cells by natural drug delivery. At the same time, the E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL was recruited to PROTAC molecules for the first time through the peptide ALAPYIP from HIF1α, which is another advancement of the PROTACs. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused with FK506 binding protein (FKBP12) and GFP fused with the androgen receptor (AR) were degraded under the treatment of the corresponding PROTACs. Importantly, a poly-d-arginine label was added at the carboxy-terminal, which made the overall PROTAC molecule obtain cell permeability. This is the first application of cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) in PROTACs, which provides a meaningful reference for the design of subsequent peptide PROTACs.

2.2.4. Akt

In 2016, Henning et al.59 used PROTACs technology to degrade Akt2 protein, providing new hope for cancer treatment targeting Akt. Akt2 was recruited by protein-catalyzed capture (PCC) agents previously developed78. PCC agents are a class of peptide ligands constructed using in-situ click chemistry and have high affinity with target proteins79,80. Notably, this ligand showed activating activity in the authors' previous study, so the present study also demonstrates that proteins can be degraded by PROTACs whether they are activated or not. Additionally, to enhance overall molecular permeability, HIV TAT peptide was added to this PROTAC. The degradation ability of this peptide PROTAC (CPP tri_a-PR) on Akt2 was validated in OVCAR3 cells, which could reduce the target protein to the lowest value 4 h after administration. They also observed a dose-dependent decrease in Akt after treatment with CPP tri_a-PR with an EC50 value of 128 ± 19 μmol/L.

2.2.5. PI3K/FRS2α

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) has been shown to play a key role in the development and progression of many types of cancer81. When the tyrosine residues of RTK are phosphorylated, some proteins with Src homology 2 (SH2) or phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains such as PI3K and FRS2α in this pathway can bind to the phosphorylated tyrosine region to further activate the cascade82,83. Therefore, selectively targeting proteins with PTB or SH2 domains for degradation can inactivate tyrosine kinase signals to inhibit tumor development84.

In 2013, Hines et al.66 proposed the concept of phosphoPROTACs based on the RTK pathway, which is a method for selectively targeting PROTACs to cancer cells (Fig. 1B). The author selected the phosphorylation motif of TrkA (tropomyosin receptor kinase A) and ErbB3 as the targeting peptide of FRS2α and PI3K, respectively, and connects the peptide ligand of VHL (ALAPYIP) to design phosphoPROTACs. In the absence of activated RTK, phosphoPROTACs cannot be phosphorylated. Thus, phosphoPROTACs cannot bind to the target protein, and the target protein would not be degraded. In contrast, after RTK activation, phosphoPROTACs are phosphorylated to create a binding site for the effector protein FRS2α or P13K, and then degrade in a VHL-dependent manner (degradation of FRS2α in PC12 cells: DC50 = 40 μmol/L, Dmax > 90%). In a mouse xenograft model, treatment with ErbB2PPPI3K resulted in a 40% reduction in tumor size, which is the first demonstration of anti-tumor activity in vivo.

2.2.6. CREPT

CREPT was first identified as a new oncogene by Lu et al.85 and it needs to be proven to have the potential as a therapeutic target for tumor. In 2020, Ma and his colleagues60 designed a cell-permeable peptide PROTAC that degrades CREPT based on the above research, named PRCT. The CREPT recruitment peptide in PRCT comes from its own interaction motif (KDVLSEKEKKLEEYKQKLARV) during its dimerization, which provides a new guide for the development of peptide ligands. PRCT shows a high affinity for CREPT by the above motifs, and the Kd value measured in microscale thermophoresis experiments is 0.34 ± 0.11 μmol/L. Western blot experiment results showed that PRTC can degrade CREPT in a proteasome-dependent manner in Panc-1, AsPc-1 and MIA-PaCa-2 cell lines (DC50 = 10 μmol/L). In addition, a transmembrane transit peptide (KRRRR) was added at the C-terminus of PRCT, and through flow cytometry and fluorescence imaging analysis experiments, it was concluded that PRTC can infiltrate pancreatic cancer cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

2.2.7. X-protein

Most hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV)86. X-protein plays an important role in virus replication87. In 2014, Montrose and colleagues67 reported peptide PROTACs degrading X-protein. Taking advantage of the characteristic that X-protein can form dimer, the author took its N-terminal oligomerization domain as the recruitment ligand of X-protein88. In addition, C-terminal instability domains (RHKLVRSPAPCKFFTSA) or ODD domain was connected to the former together with CCP (RRRRRRRR). They together constitute two X-protein-targeting PROTACs. In HepG2 cells expressing X-protein of full length or C-terminally truncated forms, the addition of the two PROTACs induced the degradation of X-protein. At the same time, they can inhibit X-protein-induced apoptosis as a dominant negative inhibitor. In short, the PROTACs have the potential for further research in HBV prevention and treatment.

2.2.8. Tau

Reducing the abnormal accumulation of tau protein is considered as a promising strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases different from other targets89. Traditional anti-tau therapy is discontinued due to its toxicity and/or lack of efficacy90. PROTAC provides a possible way to selectively remove these protein aggregates. However, like many disease-related non enzymatic proteins, it is difficult to target them with suitable small molecular compounds91.

In 2016, Chu et al.62 reported the first tau-targeted protein degradation system using peptide-based PROTAC compounds, which consists of four motifs: (i) Tau recognition motif, (ii) linker, (iii) E3 ligase binding motif, and (iv) cell penetrating peptide (CPP) motif. In order to select the best tau recognition peptide, three known peptides were evaluated and the peptide corresponding to the YQYQDATADEQG sequence was determined to be the best in their research. Two E3 ligases were analyzed, namely Skp1-cullin-F box (SCF) ligase and VHL, respectively. The results show that VHL is better than SCF. VHL peptide ligand, linker (GSGS), tau protein peptide ligand and cell penetrating peptide (RRRRRRRR) were linked to establish the most active PROTAC compound TH006, which has a 32-amino-acid sequence. TH006 promotes polyubiquitination through E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL, successfully penetrates into cells and induces tau protein degradation. As a tau protein degrader for the treatment of AD, TH006 needs to have the ability to cross the blood‒brain barrier (BBB). However, this was not clearly explained by the authors. In utilizing TH006 for animal experimentation, the authors chose a combination of intranasal administration and intravenous injection, which may be intended to avoid BBB hindrance. At the same time, it also reflects that peptide PROTAC has some difficulties in penetrating the BBB. In conclusion, further clinical development of tau degrader based on peptide is required to fully consider their BBB permeability.

In 2018, Lu et al.61 again used PROTAC technology to degrade tau protein, but this time they used Keap1 binding motif. Keap1 is a substrate adaptor protein for a Cullin 3/Ring-Box1-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase complex92. It is well known that the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway has a cytoprotective function and can resist various exogenous and oxidative stresses that lead to neurodegenerative diseases and cancer93. In this study, the author used peptide PROTAC and tried to prove its potential application. For Tau-Keap1-CPP-PROTAC, the Kd values of Keap1 and Tau proteins were determined by isothermal titration calorimetry, and they were determined to be 22.8 and 763 nmol/L, respectively. The designed PROTAC molecule degraded the tau protein in SH-SY5Y, Neuro-2a and PC-12 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. And through the combined treatment experiment of proteasome inhibitor MG132 and Keap1 siRNA silencing, it was confirmed that the degradation was carried out by UPS. Although the BBB permeability of the PROTAC has not been evaluated, this study still has important value. It not only realizes the application of Keap1 peptide ligands, but also verifies that the E3 ubiquitin ligase Keap1 can be used in PROTAC technology and expands E3 toolbox94.

2.2.9. α-Synuclein

More and more studies have shown that α-synuclein plays an important role in the occurrence and development of Parkinson's disease95. In addition, the accumulation of α-synuclein can impair lysosomal function, thereby preventing its clearance from the cell through the lysosomal pathway96. Therefore, using the ubiquitin proteasome pathway to degrade α-synuclein protein may be a potential therapeutic strategy.

Qu et al.63 developed a peptide-based α-synuclein degradation agent with cell membrane permeability. The degradation agent consists of three parts, namely the cell penetrating part (CPD), α-synuclein binding domain (PBD) and proteasome targeting motif (PTM). Among them, the PDB is a segment (amino acids 36–45) of β-synuclein that has a high ability to bind to α-synuclein. For the CPD, the HIV-TAT peptide was selected, which makes the whole peptide PROTAC obtain permeability to cell membrane. Finally, the authors used the RRRG motif as the PTM part of this PROTAC, which was proven to target the proteasome97. Subsequent experimental results showed that this exogenous TAT-PBD-PTM peptide molecule with a length of 25 amino acids was sufficient to induce the down-regulation of α-synuclein protein in a time- and concentration-dependent manner in a cell model. Functionally, TAT-PBD-PTM rescued cytotoxicity induced by α-synuclein overexpression, and the effects were blocked by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in primary neurons. The above results indicate that the TAT-PBD-PTM peptide molecule may have the unique potential to target α-synuclein to treat PD, but the E3 ubiquitin ligase targeted by its PTM moiety is not well defined. Similarly, as a drug acting in the central nervous system (CNS), it is regrettable that the authors did not evaluate the BBB permeability of this PROTAC. However, the authors speculate that peptide PROTAC with TAT peptide has potential ability to cross BBB. On the other hand, TAT peptide was shown to have the ability to carry peptide cargos across the BBB in rat models98. For this reason, it may be feasible for TAT-PDB-PTM to pass through BBB99. This needs to be confirmed by more experiments in the future. At present, pharmaceutical technologies such as nanoparticles drug delivery system (NPDDS) may provide substantive assistance for peptide PROTAC to obtain BBB permeability100.

2.2.10. β-Catenin

At present, although many small molecule inhibitors of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway have been identified, none of the drugs has been approved for clinical use101. SAHPA1 and xStAx are two Axin-based stapled helical peptides that can bind to β-catenin, but in vivo, due to the rapid accumulation of β-catenin in tumors, it is still a challenge to drive them to effectively inhibit Wnt-dependent tumor growth65,102,103.

In 2020, Liao et al.104 used 6-aminocaproic acid to link the peptide ligands of VHL with xStAx and SAHPA1, respectively, and designed and synthesized the β-catenin-targeting peptide PROTAC: xStAx-VHLL and SAHPA1-VHLL. Researchers found that SAHPA1-VHLL has little effect on the stability of β-catenin, unsurprisingly it has little effect on Wnt/β-catenin signal. However, xStAx-VHLL has a strong inhibitory effect on Wnt signaling, and continues to degrade β-catenin in cancer cells and intestinal organoids derived from wild-type and APC–/– mice. xStAx-VHLL also inhibited tumor formation in xenograft mouse models and reduced intestinal tumors in APCmin/+ mice. In addition, xStAx-VHLL effectively inhibits the survival of tumor organoids in patients with colorectal cancer, which highlights its clinical potential. In two different cases of Wnt deficiency or accumulation, β-catenin has two different forms of phosphorylation and non-phosphorylation. Normally, phosphorylated β-catenin will be ubiquitinated and degraded by proteasome. Regrettably, whether β-catenin degraded by xStAx-VHLL is in a phosphorylated form was not explicitly stated. For the next step of development, this could be further clarified. Finally, the author puts forward ideas for the modification of xStAx-VHLL, such as replacing the VHL peptide ligand composed of natural amino acids or using other E3 ligands, which also have enlightening effects on the design of other peptide PROTACs.

3. Nucleic acid PROTACs

Nucleic acid PROTACs have evolved rapidly since the publication of TRAFTACs in 2021, and in less than a year transcription factor PROTACs (TRAFTACs, O'PROTACs and TF-PROTACs) that degrade transcription factors (Table 3), RNA-PROTACs that degrade RNA binding proteins, G4-PROTAC that degrade G4 binding proteins and aptamer based PROTACs have been developed105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110. These achievements show that nucleic acid PROTACs are quite attractive as a biological tool and a future disease treatment method.

Table 3.

Nucleic acid PROTACs targeting transcription factors (TF PROTACs).

3.1. Advantage of nucleic acid PROTACs

The emergence of TF PROTACs provides the possibility of direct targeting for diseases caused by various transcription factor disorders. Transcription factors (TFs), also known as trans acting factors, are a group of proteins that can bind to cis acting elements, enhancers or silencers located 50–5000 bp upstream of the transcription start site and participate in regulating the transcription efficiency of the target genes111. The imbalance or abnormal activity of TFs is the causative factor of many cancers and inflammatory diseases and TFs are considered to be a promising target for the treatment of related diseases112. With the exponential growth of knowledge about the assembly mechanism of transcription complexes, different strategies for indirectly regulating the activity of TFs with small molecule compounds have emerged, including blocking protein–protein interactions, protein-DNA interactions, and so on113,114. Unlike general TFs, nuclear hormone receptors contain a ligand binding domain (LBD), which makes it easier for small molecule PROTACs to target them115. Thus, since 2003, a number of small molecule PROTACs targeting the estrogen receptor (AR) and androgen receptor (ER) have been developed and continuously improved116. However, most other TFs lack ligand binding domains, which affects the development of small molecule TF PROTACs117. TF PROTACs that use endogenous nucleic acid sequences as transcription factor ligands provide a solution. Generally, the development of TF PROTACs only needs to analyze and synthesize the nucleic acid sequence that binds to the target protein, and connects it with E3 ubiquitin ligase to obtain the corresponding target protein degrading agent. This development paradigm bypasses the development of small molecule ligands for target proteins such as TFs and greatly reduces the difficulty of developing degraders for similar target proteins.

Secondly, aptamer based nucleic acid PROTACs elevate the targetability of conventional small molecule PROTACs. Although small molecule PROTACs have demonstrated significant advantages over traditional small molecule drugs in many ways, there is still an urgent need to develop novel strategies to improve their aqueous solubility, membrane permeability, and tumor targeting. Aptamer is a single-stranded nucleic acid composed of complex three-dimensional structures such as stems, loops, hairpins, and G4 polymers118. They bind to the target protein with high specificity and affinity through hydrogen bonding, van der Waals force, base stacking force and electrostatic effect. Compared with other targeting vectors, aptamer has many advantages, such as: easy preparation, easy structure modification, and good tissue permeability119,120. Notably, the nucleic acid aptamer AS1411 is rich in guanine bases, which can specifically recognize and bind to nucleolin, which is widely used as a biomarker for targeted anti-tumor therapy due to its high expression on the surface of cancer cells121. In addition, AS1411 itself has a good inhibitory activity on tumors with over-expression of nucleolin, and has been widely used as a transporter for tumor targeted delivery of small molecule drugs122. Sheng106 and Tan’s group138 respectively used AS1411 to construct two different types of aptamer-based nucleic acid PROTACs (aptamer–PROTACs), both of which proved its targeting and efficiency beyond normal small molecule PROTAC.

3.2. Development of nucleic acid PROTACs

3.2.1. Transcription factor (TF) PROTACs

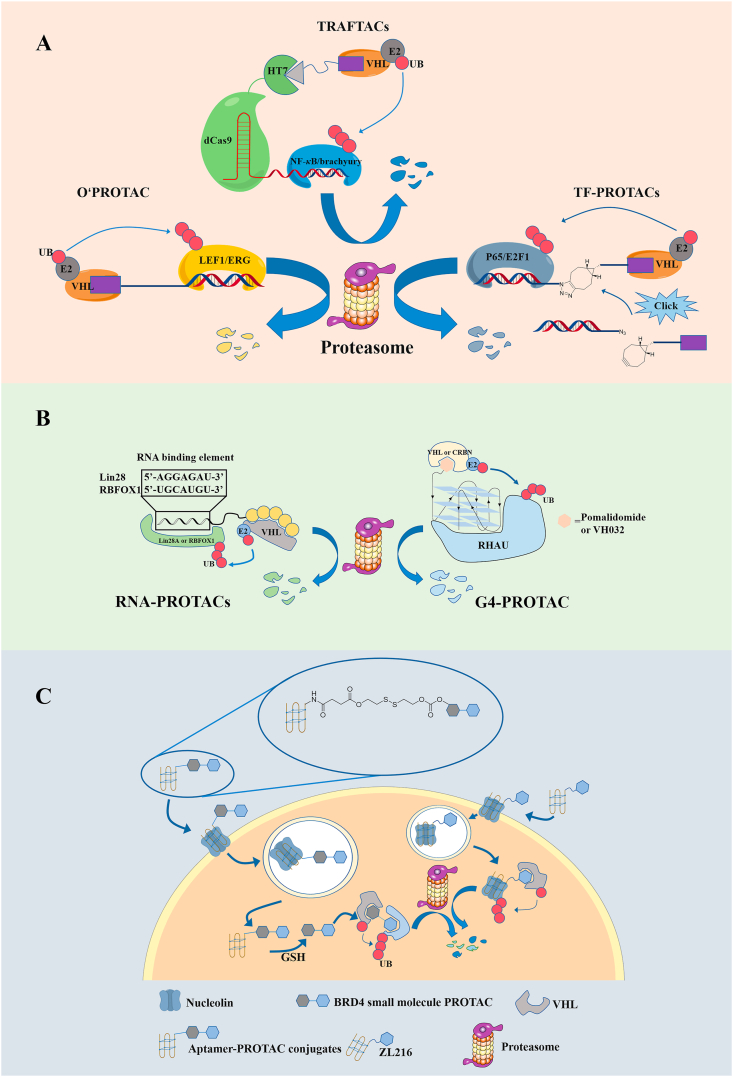

Samarasinghe et al.108 developed a transcription factor degradation technology called TRAFTACs (Fig. 2A). TRAFTACs contain a short transcription factor recognition sequence (dsDNA), which bypasses the limitation of insufficient small molecule ligands by using the inherent TF-DNA binding ability. The double-stranded DNA sequence of TRAFTAC is linked to CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which recognizes and binds to the dCas9-HT7 fusion protein. The HT7 is a modified bacterial dehalogenase that covalently reacts with a hexyl chloride tags123. Therefore, based on the HaloPROTAC study, after the researchers added HaloPROTAC, VHL was recruited to the dCas9-HaloTag7 adapter, which induced the proximity of TF and VHL124. Subsequently, TRAFTACs were applied to two oncogenic transcription factors and successfully demonstrated the knockout of two pathogenic transcription factors NF-κB and brachyury. In order to prove post-translational down-regulation, qRT-PCR experiments were performed, which showed that NF-κB RNA levels did not change after TRAFTAC or HaloPROTAC treatment. In addition, when using the inactive epimer of PROTAC, no significant TF degradation was observed, verifying the dependence of degradation on VHL E3 ligase recruitment. In order to prove the applicability of the TRAFTAC strategy to in vivo models of TF degradation, the authors microinjected ribonucleocomplexs of dCas9-HaloTag7, active or inactive HaloPROTAC and a brachyury-targeting nucleic acid sequence into zebrafish embryos. In embryos treated with complexes containing active HaloPROTAC, severe tail defects were observed, which is consistent with the necessity of brachyury in embryonic development and tail growth. This apparent phenotypic change due to the successful degradation of brachyury demonstrates the ability to target TFs degradation.

Figure 2.

Degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by nucleic acid PROTACs. (A) Degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by TF PROTACs; (B) Degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by RNA-PROTACs and G4-PROTAC; (C) Degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by aptamer–PROTACs.

The abnormalities of lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1) and ETS-related genes (ERG) are closely related to the proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells125, 126, 127. Shao et al.109 used a strategy similar to TRAFTAC to design and synthesize the nucleic acid PROTAC that degrades the above-mentioned transcription factors, and named it O’PROTAC (Fig. 2A). They used the double-stranded oligonucleotide sequences as ligands for recruiting LEF1 and ERG, respectively, and connected them to the E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL ligand through alkyl chains of different lengths128, 129, 130. Among them, the first three nucleotides TAC and ACG of the two sequences do not participate in the recognition of the target protein, and only play a role in protecting the oligonucleotide from degradation. Subsequent biological evaluation results showed that the two O'PROTACs OP-V1 and OP-C-N1 successfully promoted the degradation of the corresponding target proteins, inhibited their transcriptional activity, and inhibited the growth of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Compared with the TRAFTACs developed by Samarasinghe et al.108, O'PROTAC discards the artificially constructed dCas9-HT7 fusion protein, which improves the limitation of nucleic acid-based PROTAC in clinical application.

Different from O'PROTAC, Liu et al.107 used the Click reaction to connect DNA oligonucleotides and VHL ligands and called them TF-PROTACs (Fig. 2A). The selectivity of these TF-PROTACs depends on the DNA oligonucleotides used, which can be specific to the transcription factor of interest. The researchers synthesized two series of VHL-based TF-PROTAC (dNF-κB and dE2F) based on the azide–alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction of commercially available azide DNA oligomers and bicyclooctane-modified VHL ligands. After removing the excess ligand VHLL-XBCN through a simple purification process, TF-PROTAC was transfected into cells, and then based on the selective recognition/binding of TFs to DNA oligomers, TF-PROTAC was observed to degrade p65 and E2F1 at both VHL E3 ligase and the protease dependent manner. In addition, the two series of TF-PROTAC also showed excellent anti-proliferative effects in HeLa cells. This research significantly increases the targeting spectrum of PROTAC.

3.2.2. RNA-PROTACs

RNA binding proteins (RBPs) are an important part of the cell proteome131. RBP binds to RNA in a dynamic, coordinated and sequence selection manner, participates in all aspects of RNA metabolism, and plays an important and multi-faceted role in the process of post-transcriptional gene regulation132. In fact, some RBP expression dysregulation has been shown to cause disease, including cancer133. However, it has proven difficult to target RBP with conventional methods such as small molecule drugs134.

Ghidini et al.105 introduced a new concept and developed a bifunctional molecule RNA-PROTAC to achieve the degradation of two RBPs (Fig. 2B). First, the researchers identified short oligonucleotides that are iso-sequential with the RNA consensus binding element (RBE) of an RBP as the target protein ligand. Subsequently, considering that oligoribonucleotides may be unstable in the presence of nucleases, diastereoisomeric phosphorothioate (PS) linkages and alkylation of the 2′-hydroxyl group were used instead of the phosphodiester backbone. Linking the modified oligoribonucleotides with the VHL peptide ligand, the author obtained the complete RNA-PROTACs. The results of subsequent biological experiments showed that RNA-PROTAC achieved the degradation of RNA-binding proteins LIN28 (DC50 = 2 μmol/L in NT2/D1 cells) and RBFOX1 (DC50 = 2 μmol/L in HEK293T cells), respectively. This discovery provides new ideas for the development of RBPs inhibition methods.

3.2.3. G4-PROTAC

G4, known as G-quadruplex, is an atypical nucleic acid secondary structure composed of DNA or RNA, which widely exists in living organisms and regulates gene transcription, replication and other functions135,136. The DEAH box helicase RHAU is a G4 binding protein that is highly expressed in tissues from patients with C9orf72 associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and is therefore an important therapeutic target137. Patil et al.110 linked a G4 warhead named T95-2T to CRBN and VHL small molecule ligands, respectively, through the click reaction to yield G4-PROTAC (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, marked degradation of RHAU was investigated in both the HeLa and K-562 cell lines to which G4-PROTAC had been added and the dependence of its degradative capacity on the ubiquitin proteasome pathway was also confirmed. This study demonstrates the feasibility of targeted protein degradation mediated by nonstandard nucleic acid structures, not just simple sequence motifs.

3.2.4. Aptamer–PROTACs

Sheng group106 designed the first aptamer–PROTAC conjugates (APCs) by connecting AS1411 with the small molecule BET-PROTAC through a linker with ester-disulfide structure (Fig. 2C). After APCs enters the cell, the disulfide bond of the linker is destroyed by GSH, and then the carbon anhydride ester bond is attacked by the free mercapto group to free the corresponding small molecule PROTACs. Compared with the unmodified BET-PROTAC, the conjugates showed excellent specificity and effective effect on the BET degradation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells overexpressing nucleolar protein (DC50 = 22 nmol/L, Dmax > 90% in MCF-7 cells). Combined with the analysis results of flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microcopy, it can be seen that AS1411 can mediate the membrane permeation process of APCs through macropinocytosis, although aptamer has large size and heavy negative charge. This study proved for the first time that aptamer binding helps to improve the tumor-targeting specificity of PROTAC, thereby enhancing in vivo anti-tumor activity and reducing toxicity.

According to the latest research by Zhang et al.138, nucleic acid aptamers can also be used directly as target protein ligands. They developed a PROTAC ZL216 based on the nucleic acid aptamer AS1411 (Fig. 2C), and it showed excellent serum stability and water solubility. A DBCO-azide click reaction is used to connect AS1411 and VHL ligand to form PROTAC ZL216. Based on the differential expression of nucleolar protein on the cell surface, ZL216 can specifically bind to and internalize to breast cancer cells, but not to normal breast cells. In addition, ZL216 can promote the formation of nucleolar protein-ZL216-VHL ternary complex in breast cancer cells, and effectively induce the degradation of nucleolar protein in vitro (DC50 = 13.5 nmol/L in MCF-7 cells, DC50 = 17.8 nmol/L in BT474 cells) and in vivo, thereby inhibiting the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. However, there are still some issues that need to be clarified in the follow-up, such as the influence of the length of the aptamer on the formation of ternary complexes and the degradation efficiency of PROTAC. In conclusion, this study proves another use of aptamers in the design and development of PROTACs, and at the same time provides a promising strategy for the development of tumor-selective PROTACs.

4. Antibody PROTACs

Antibody PROTACs is also a newly developed type of PROTAC in the past two years, giving PROTACs brand new functions and properties139. At present, antibody PROTACs are mainly divided into antibody–PROTAC conjugates, AbTACs and GlueTAC (Fig. 3A)140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146. Antibody–PROTAC conjugates are a trifunctional macromolecule, which is formed by connecting small molecule PROTAC and specific antibody through a cleavable linker. AbTACs are bispecific IgG and recruited E3 ubiquitin ligase and POI, respectively. GlueTAC is a membrane protein degrader mainly composed of nanobody with proximity reactive uncanonical amino acid (PrUAA). The three types of antibody PROTACs are different from each other, but each has advantages.

Figure 3.

(A) Degradation mechanism of target proteins mediated by different types of antibody PROTACs; (B) XIAP-based PROTAC for targeted degradation of ERα (PROTAC 5) and VHL-based PROTAC for targeted degradation of ERα (PROTAC 6); (C) Three ligation strategies for coupling antibodies to small molecules; (D) Structure of trastuzumab–PROTAC conjugate (Ab–PROTAC 3).

4.1. Advantage of antibody PROTACs

First of all, antibody–PROTAC conjugates can improve the pharmacokinetic properties of traditional small molecule PROTACs, increase their tissue selectivity, and avoid the side effects caused by protein degradation in normal cells147, 148, 149. Many of the in vivo assessments of degrader described in the previous literature have adopted a route of administration that may be difficult to convert to routine use in humans (for example, intraperitoneal administration)150,151. The combination of PROTACs and antibodies now provides an intravenous administration option for clinical trials, and has a stronger effect while reducing the amount of administration146.

Secondly, AbTACs and GlueTAC expand the POI range that PROTACs can degrade and incorporates cell-surface proteins into the degradation category of PROTACs technology, although they rely on the lysosomal pathway instead of the traditional ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. In short, they are considered a new general paradigm for degradation of cell-surface proteins.

4.2. Development of antibody PROTACs

4.2.1. Antibody–PROTAC conjugates

In 2020, Pillow et al.146 designed and obtained a VHL-based PROTAC molecule GNE-987 that targets BRD4 degradation. This degradation agent has picomolar cell efficacy. Subsequently, in view of its poor pharmacokinetic properties and unfavorable in vitro DMPK properties, researchers hope to solve its delivery problem for further in vivo activity evaluation. Therefore, they chose the hydroxyl group of the VHL ligand in GNE-987 as a connecting handle, and connected it to the CLL1 antibody through a carbonate moiety and a disulfide bond to obtain the antibody–PROTAC conjugate CLL1-5. In both HL-60 and EOL-1 xenograft models, CLL1-5 showed good in vivo activity, in vivo stability and pharmacokinetic properties. At the same time, Dragovich141 once again reported a group of antibody–PROTAC conjugates targeting estrogen receptor α (ERα). The PROTAC 5 and PROTAC 6 (Fig. 3B) that have degrading effects on ERα were linked to the HER2 specific antibody with three different ligation strategies (Fig. 3C), and it was observed that the antibody–PROTAC conjugates selectively induced ER degradation in MCF7-neo/HER2 cells.

In the same year, Maneiro and colleagues144 described a strategy for selectively degrading proteins in specific cell types. They designed and synthesized a trastuzumab–PROTAC conjugate (Fig. 3D). One conjugate contains four PROTAC molecules. Western blots showed that it selectively degraded BRD4 in HER2 positive cells, but not BRD4 in HER2 negative cells. Using live-cell confocal microscopy, the researchers showed that the internalization and lysosomal transport of the conjugate in HER2 positive cells resulted in the release of active PROTAC in an amount sufficient to induce effective BRD4 degradation. Using the catalytic effect of PROTACs and the tissue specificity of ADCs, antibody–PROTAC conjugates can remedy the disadvantages of PROTACs and ADCs144.

In addition, Dragovich et al.142,143 introduced their systematic research on antibody–PROTAC conjugates based on BRD4 degraders in 2021, and explored the effect of changes in conditions such as different warheads and linkers on the activity of antibody–PROTAC conjugates. Among them, the in vitro experimental results show that by selecting specific antibodies, the small molecule PROTAC can be directly delivered to the corresponding antigen-high expression cancer cells without redesigning the design of the relevant antibody linker. This study preliminarily confirmed the versatility of antibody and PROTAC coupling strategy.

4.2.2. AbTACs

In 2021, different from the aforementioned antibody–PROTACs that improve targeting and pharmacokinetic properties, Cotton et al.140 used bispecific IgGs (BsIgG) called AbTACs to simultaneously recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases RNF43 and PD-L1, resulting in PD-L1 degradation (Fig. 3A). The author points out that, compared to E3 ubiquitin ligases such as VHL and CRBN, RNF43 is a single-pass E3 ligase with a structured ectodomain, which has the conditions for developing an antibody-based degradation membrane protein PROTAC152. Subsequently, the author verified the above-mentioned hypothesis with the GFP model protein, and prepared a recombinant antibody for the ectodomain of RNF43. On the other hand, atezolizumab was used as a recruiting antibody for PD-L1. Finally, the two were assembled and spliced to obtain BsIgG AC-1. A two-step BLI experiment proved that AC-1 can indeed bind RNF43 and PD-L1 at the same time. The MDA-MB-241 cell line was further treated with AC-1, and it was found that AC-1 effectively induced PD-L1 degradation, with a DC50 of 3.4 nmol/L and a maximum degradation percentage of 63% in 24 h. In addition, PD-L1 was also degraded in AC-1 treated MDA-MB-231, HCC827 and T24 cell lines, indicating that AC-1 has a wide range of cell applicability.

4.2.3. GlueTAC

In the same year, Zhang et al.153 developed the covalent nanobody-based PROTAC strategy, named GlueTAC, which is considered to be another paradigm for targeted degradation of membrane proteins (Fig. 3A). Nanobodies are antibodies derived from heavy chains and have excellent application prospects in the treatment of solid tumors154. The author combined the MS assisted screening platform (MSSP) and the genetic code expansion (GCE) strategy to design and produce a nanobody variants (gluebody), which can specifically covalently bind to PD-L1 and recruit PD-L1155. Notably, this specific binding is achieved through the modification of proximity reactive uncanonical amino acid (PrUAA). In order to enhance the internalization and degradation of PD-L1 mediated by Gluebody, the researchers added cell-penetrating peptide and lysosome-sorting sequence (CPP-LSS) to its C-terminal, and finally obtained the target product GlueTAC. Subsequently, cell and animal experiments showed that GlueTAC could efficiently degrade PD-L1, had sustained T cell activation, and significantly inhibited tumor growth in mice.

5. Other non-small molecule protein degraders

In recent years, while NSM-PROTACs are optimized in all aspects, the development of other protein targeted degradation technologies is also accelerating. Significantly, we found that macromolecule has been applied many times in these technologies. Although this paper mainly introduces the extension of PROTACs, given that other technologies play an important role in the field of protein degradation, we try to help researchers better understand them through tables (Table 4).

Table 4.

Other non-small molecule protein degraders.

| Name | Target | Target type | Applied macromolecules | Degradation pathway | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bispecific aptamer chimeras | PTK-7/Met | Membrane protein | Nucleic acid (aptamer) | Lysosome | 156 |

| F-box/intrabody-targeted protein degradation | RHOB-GTP | Intracellular protein | Antibody (nonobody) | Proteasome | 157 |

| M6Pn-LYTACs | ApoE4/EGFR/CD71/PD-L1 | Extracellular/membrane protein | Glycopeptide/antibody | Lysosome | 158 |

| GalNAc-LYTACs | EGFR/integrins/α-DNP antibody/MIF/NeutrAvidin | Extracellular/membrane protein | Tri-GalNAc/peptide/antibody | Lysosome | 159, 160, 161 |

| Sweeping antibodies | IL-6R/C5 | Free antigen | Antibody | Lysosome | 162,163 |

| Abdegs or Seldegs | IgG/trastuzumab | Antibody | Antigen | Lysosome | 164,165 |

6. Conclusions

In the past two decades, PROTACs technology has developed vigorously, representing a new direction in drug discovery166,167. Among them, small molecule PROTACs are obviously more favored. However, in the face of more undruggable targets, the lack of corresponding small molecule ligands seems to limit the scope of small molecule PROTACs149. It requires researchers on one hand to advance technological advances to identify a large number of available small molecule ligands, and on the other hand to target easy-to-develop peptides and nucleic acid ligands, and design suitable NSM-PROTACs to expand more degradable targets168.

With the birth of PROTACs technology, peptide PROTACs have the longest history, degrading more than ten kinds of undruggable targets169. However, compared with small molecule PROTACs, the huge molecular weight and multi-polar functional groups of peptide PROTACs may lead to poor DMPK profile39,170. For this reason, in the early stage, peptide PROTACs were administered by injections to verify the in vivo efficacy10. However, how to improve the DMPK profile of peptide PROTACs is still a major hurdle that plagues researchers. With the use of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) in peptide PROTACs, the membrane permeability of peptide PROTACs has been greatly improved34,171. Currently, three CPPs are mainly used in peptide PROTACs, namely HIV TAT peptide, poly-d-arginine and Xentry34. In addition, stable peptides constructed by variable chemical methods are another effective method to increase the membrane permeability of peptides172.

In the past, the main challenge of targeting transcription factors (TFs) was the lack of suitable ligand capsules on them173. As a new member of NSM-PROTACs, TF PROTACs bypassed this obstacle by using nucleotide chains as ligands to recruit TFs. This highly innovative design is of great significance for curing diseases caused by TFs imbalance. Similarly, the PROTACs also have in vivo delivery problems. Solving this problem will make TF PROTACs have bright clinical prospects.

In addition, the coupling of nucleic acid aptamers, antibodies and small molecule PROTACs has greatly improved their targeting and pharmacokinetic properties139,169. Therefore, these two methods should be strongly considered during the preclinical exploration of PROTACs. In the future, finding the differences in antigen expression between different cancer cells and preparing suitable antibodies may be more promoting the clinical development of small molecule PROTACs. Notably, PROTAC, which uses antibodies as ligands for POI and E3 ubiquitin ligase, has been initially successful in the field of cell membrane degradation, and whether it can be extended to the degradation of other membrane proteins remains to be studied140.

Since 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has ravaged the world. In fact, the virus has increasingly become the Public Health Enemy No. 1. The difficult problem for researchers is to quickly find a safe, reliable and targeted antiviral drug. For antiviral therapy, the innate advantages of PROTACs are overcoming drug resistance and removal of all protein function. Additional studies have shown that antiviral PROTACs stimulate the host immune response to virus20. In addition to the X-protein peptide PROTAC mentioned above, Wispelaere and his colleagues174 adopted small molecule PROTACs to demonstrate the great potential of PROTACs in the antiviral field. In the future, it may be an interesting attempt to target a key protein that can bind to viral nucleic acid sequences and design a nucleic acid PROTACs to fight the virus. Ribonuclease targeting chimeras (RIBOTACs) are new degradation technology, which can recruit ribonucleases (RNases) to degrade RNA175. Taking advantage of this technology to directly target the viral genome and kill the virus as a powerful antiviral therapy, an attempt has been made on SARS-CoV-2 by Disney et al.176 with breakthrough progress.

Finally, the instability of endogenous macromolecules should also be considered in the development process of NSM-PROTACs40. The emergence of new targeted protein degradation technologies also requires attention, such as: LYTACs, ATTACs and AUTACs158,177,178. In the absence of further advancement of the above technologies, combining them with macromolecules such as peptides, nucleic acids, antibodies, etc. may be surprising in the field of protein degradation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Projects 81773581, 82173680 and 81930100 of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, CPU2018GY02 of Double First Class Innovation Team of China Pharmaceutical University, the Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University (No. SKLNMZZ202003); the “Qing Lan” Project of Jiangsu Province, and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (No. YESS20180146, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.022.

Contributor Information

Xiaoli Xu, Email: xuxiao_li@cpu.edu.cn.

Qidong You, Email: youqd@163.com.

Zhengyu Jiang, Email: jiangzhengyucpu@163.com.

Authors contributions

Zhengyu Jiang, Xiaoli Xu and Qidong You conceived and designed this review. Sinan Ma wrote the original manuscript. Jianai Ji, Yuxuan Zhu, Junwei Dou and Yuanyuan Tong collected the references. Xian Zhang, Shicheng Xu and Tianbao Zhu made the figures. Zhengyu Jiang, Xiaoli Xu and Qidong You revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cromm P.M., Crews C.M. Targeted protein degradation: from chemical biology to drug discovery. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang P., Zhou J. Proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC): a paradigm-shifting approach in small molecule drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2018;18:1354–1356. doi: 10.2174/1568026618666181010101922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adjei A.A. What is the right dose? The elusive optimal biologic dose in phase Ⅰ clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4054–4055. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luh L.M., Scheib U., Junemann K., Wortmann L., Brands M., Cromm P.M. Prey for the proteasome: targeted protein degradation–a medicinal chemist s perspective. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2020;59:15448–15466. doi: 10.1002/anie.202004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dang C.V., Reddy E.P., Shokat K.M., Soucek L. Drugging the ‘undruggable' cancer targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:502–508. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao H., Sun X., Rao Y. PROTAC technology: opportunities and challenges. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11:237–240. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoch K.M., Miller T.M. Antisense oligonucleotides: translation from mouse models to human neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2017;94:1056–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokatlian T., Segura T. vol. 2. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol; 2010. pp. 305–315. (siRNA applications in nanomedicine). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crews C.M. Inducing protein degradation as a therapeutic strategy. J Med Chem. 2018;61:403–404. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto K.M., Kim K.B., Kumagai A., Mercurio F., Crews C.M., Deshaies R.J. Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to the skp1-cullin-f box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141230798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley D.L., Crews C.M. Small-molecule control of intracellular protein levels through modulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:2312–2330. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang D., Baek S.H., Ho A., Kim K. Degradation of target protein in living cells by small-molecule proteolysis inducer. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:645–648. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravid T., Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–690. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paiva S.L., Crews C.M. Targeted protein degradation: elements of PROTAC design. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;50:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondeson D.P., Mares A., Smith I.E., Ko E., Campos S., Miah A.H., et al. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:611–617. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettersson M., Crews C.M. Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs)–past, present and future. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2019;31:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maniaci C., Ciulli A. Bifunctional chemical probes inducing protein–protein interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;52:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin Y.H., Lu M.C., Wang Y., Shan W.X., Wang X.Y., You Q.D., et al. Azo-protac: novel light-controlled small-molecule tool for protein knockdown. J Med Chem. 2020;63:4644–4654. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng G., Li D., Kang Y., Hou T. Integrative modeling of PROTAC-mediated ternary complexes. J Med Chem. 2021;64:16271–16281. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Ortiz W., Zhou M.M. Could PROTACs protect us from COVID-19? Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:1894–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bondeson D.P., Smith B.E., Burslem G.M., Buhimschi A.D., Hines J., Jaime-Figueroa S., et al. Lessons in PROTAC design from selective degradation with a promiscuous warhead. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25:78–87 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salami J., Crews C.M. Waste disposal–an attractive strategy for cancer therapy. Sci. 2017;355:1163–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mou Y., Wen S., Gao X., Jiang Z.Y. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras: a kaleidoscope of targeted protein degradation. Future Med Chem. 2022;14:139–141. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2021-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An S., Fu L. Small-molecule PROTACs: an emerging and promising approach for the development of targeted therapy drugs. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neklesa T.K., Winkler J.D., Crews C.M. Targeted protein degradation by PROTACs. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;174:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y., Pu C., Fu Y., Dong G., Huang M., Sheng C. NAMPT-targeting PROTAC promotes antitumor immunity via suppressing myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:2859–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burslem G.M., Crews C.M. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell. 2020;181:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Testa A., Hughes S.J., Lucas X., Wright J.E., Ciulli A. Structure-based design of a macrocyclic PROTAC. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2020;59:1727–1734. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider M., Radoux C.J., Hercules A., Ochoa D., Dunham I., Zalmas L.P., et al. The protactable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:789–797. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie H., Liu J., Alem Glison D.M., Fleming J.B. The clinical advances of proteolysis targeting chimeras in oncology. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2021;2:511–521. doi: 10.37349/etat.2021.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber K. The PROTAC gold rush. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:12–16. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J., Jin J., Shen Y., Zhang L., Gong G., Bian H., et al. Emerging protein degradation strategies: expanding the scope to extracellular and membrane proteins. Theranostics. 2021;11:8337–8349. doi: 10.7150/thno.62686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes S.J., Testa A., Thompson N., Churcher I. The rise and rise of protein degradation: opportunities and challenges ahead. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:2889–2897. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin J., Wu Y., Chen J., Shen Y., Zhang L., Zhang H., et al. The peptide PROTAC modality: a novel strategy for targeted protein ubiquitination. Theranostics. 2020;10:10141–10153. doi: 10.7150/thno.46985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding Y., Fei Y., Lu B. Emerging new concepts of degrader technologies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41:464–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelay-Gimeno M., Glas A., Koch O., Grossmann T.N. Structure-based design of inhibitors of protein–protein interactions: mimicking peptide binding epitopes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:8896–8927. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaspar A.A., Reichert J.M. Future directions for peptide therapeutics development. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He R., Finan B., Mayer J.P., DiMarchi R.D. Peptide conjugates with small molecules designed to enhance efficacy and safety. Molecules. 2019;24:1855. doi: 10.3390/molecules24101855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantrill C., Chaturvedi P., Rynn C., Petrig Schaffland J., Walter I., Wittwer M.B. Fundamental aspects of DMPK optimization of targeted protein degraders. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:969–982. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burslem G.M., Crews C.M. Small-molecule modulation of protein homeostasis. Chem Rev. 2017;117:11269–11301. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou Y., Ma D., Wang Y. The PROTAC technology in drug development. Cell Biochem Funct. 2019;37:21–30. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng C.S.C., Banik S.M. Taming transcription factors with TRAFTACs. Cell Chem Biol. 2021;28:588–590. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Regenmortel M.H. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of synthetic peptides. Biologicals. 2001;29:209–213. doi: 10.1006/biol.2001.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He M., Lv W., Rao Y. Opportunities and challenges of small molecule induced targeted protein degradation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:685106. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.685106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin L., Hu Q. Chimera induced protein degradation: PROTACs and beyond. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;206:112494. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raina K., Crews C.M. Targeted protein knockdown using small molecule degraders. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;39:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee A.C., Harris J.L., Khanna K.K., Hong J.H. A comprehensive review on current advances in peptide drug development and design. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2383. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang Y.M., Lin D.Q., Yao S.J. Review on biomimetic affinity chromatography with short peptide ligands and its application to protein purification. J Chromatogr A. 2018;1571:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y., Liu M., Xie S. Harnessing phage display for the discovery of peptide-based drugs and monoclonal antibodies. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27:1–8. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666201111144353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linciano S., Pluda S., Bacchin A., Angelini A. Molecular evolution of peptides by yeast surface display technology. Medchemcomm. 2019;10:1569–1580. doi: 10.1039/c9md00252a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hetrick K.J., Walker M.C., van der Donk W.A. Development and application of yeast and phage display of diverse lanthipeptides. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4:458–467. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandya P., Sayers R.O., Ting J.P., Morshedian S., Torres C., Cudal J.S., et al. Integration of phage and yeast display platforms: a reliable and cost effective approach for binning of peptides as displayed on-phage. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang H.N., Liu B.Y., Qi Y.K., Zhou Y., Chen Y.P., Pan K.M., et al. Blocking of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction by a D-peptide antagonist for cancer immunotherapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:11760–11764. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishida T., Ciulli A. E3 ligase ligands for PROTACs: how they were found and how to discover new ones. SLAS Discov. 2021;26:484–502. doi: 10.1177/2472555220965528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han L.Y., Zheng C.J., Xie B., Jia J., Ma X.H., Zhu F., et al. Support vector machines approach for predicting druggable proteins: recent progress in its exploration and investigation of its usefulness. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H., Dong J., Cai M., Xu Z., Cheng X.D., Qin J.J. Protein degradation technology: a strategic paradigm shift in drug discovery. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:138. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang Y., Deng Q., Zhao H., Xie M., Chen L., Yin F., et al. Development of stabilized peptide-based PROTACs against estrogen receptor α. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:628–635. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai Y., Yue N., Gong J., Liu C., Li Q., Zhou J., et al. Development of cell-permeable peptide-based PROTACs targeting estrogen receptor α. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;187:111967. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henning R.K., Varghese J.O., Das S., Nag A., Tang G., Tang K., et al. Degradation of Akt using protein-catalyzed capture agents. J Pept Sci. 2016;22:196–200. doi: 10.1002/psc.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma D., Zou Y., Chu Y., Liu Z., Liu G., Chu J., et al. A cell-permeable peptide-based PROTAC against the oncoprotein CREPT proficiently inhibits pancreatic cancer. Theranostics. 2020;10:3708–3721. doi: 10.7150/thno.41677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu M., Liu T., Jiao Q., Ji J., Tao M., Liu Y., et al. Discovery of a Keap1-dependent peptide PROTAC to knockdown tau by ubiquitination–proteasome degradation pathway. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;146:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chu T.T., Gao N., Li Q.Q., Chen P.G., Yang X.F., Chen Y.X., et al. Specific knockdown of endogenous tau protein by peptide-directed ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu J., Ren X., Xue F., He Y., Zhang R., Zheng Y., et al. Specific knockdown of α-synuclein by peptide-directed proteasome degradation rescued its associated neurotoxicity. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27:751–762 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaltiel-Karyo R., Frenkel-Pinter M., Egoz-Matia N., Frydman-Marom A., Shalev D.E., Segal D., et al. Inhibiting α-synuclein oligomerization by stable cell-penetrating β-synuclein fragments recovers phenotype of Parkinson's disease model flies. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grossmann T.N., Yeh J.T., Bowman B.R., Chu Q., Moellering R.E., Verdine G.L. Inhibition of oncogenic Wnt signaling through direct targeting of β-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17942–17947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hines J., Gough J.D., Corson T.W., Crews C.M. Posttranslational protein knockdown coupled to receptor tyrosine kinase activation with phosphoPROTACs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8942–8947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217206110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montrose K., Krissansen G.W. Design of a PROTAC that antagonizes and destroys the cancer-forming X-protein of the hepatitis B virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schneekloth J.S., Jr., Fonseca F.N., Koldobskiy M., Mandal A., Deshaies R., Sakamoto K., et al. Chemical genetic control of protein levels: selective in vivo targeted degradation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3748–3754. doi: 10.1021/ja039025z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu M.C., Chen Z.Y., Wang Y.L., Jiang Y.L., Yuan Z.W., You Q.D., et al. Binding thermodynamics and kinetics guided optimization of potent Keap1–Nrf2 peptide inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2015;5:85983–85987. [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGregor D.P. Discovering and improving novel peptide therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fosgerau K., Hoffmann T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakamoto K.M., Kim K.B., Verma R., Ransick A., Stein B., Crews C.M., et al. Development of PROTACs to target cancer-promoting proteins for ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1350–1358. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T300009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yao L., Fan Z., Han S., Sun N., Che H. Apigenin attenuates the allergic reactions by competitively binding to ER with estradiol. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1046. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shizu R., Yokobori K., Perera L., Pedersen L., Negishi M. Ligand induced dissociation of the AR homodimer precedes AR monomer translocation to the nucleus. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16734. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao H., Liu Q.S., Geng H., Tian Y., Cheng M., Jiang Y.H., et al. Crosslinked aspartic acids as helix-nucleating templates. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:12088–12093. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qin W., Xie M., Qin X., Fang Q., Yin F., Li Z. Recent advances in peptidomimetics antagonists targeting estrogen receptor α-coactivator interaction in cancer therapy. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:2827–2836. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Speltz T.E., Fanning S.W., Mayne C.G., Fowler C., Tajkhorshid E., Greene G.L., et al. Stapled peptides with γ-methylated hydrocarbon chains for the estrogen receptor/coactivator interaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:4252–4255. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nag A., Das S., Yu M.B., Deyle K.M., Millward S.W., Heath J.R. A chemical epitope-targeting strategy for protein capture agents: the serine 474 epitope of the kinase Akt2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:13975–13979. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lewis W.G., Green L.G., Grynszpan F., Radić Z., Carlier P.R., Taylor P., et al. Click chemistry in situ: acetylcholinesterase as a reaction vessel for the selective assembly of a femtomolar inhibitor from an array of building blocks. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1053–1057. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<1053::aid-anie1053>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Agnew H.D., Rohde R.D., Millward S.W., Nag A., Yeo W.S., Hein J.E., et al. Iterative in situ click chemistry creates antibody-like protein-capture agents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4944–4948. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Du Z., Lovly C.M. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:58. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0782-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schlessinger J., Lemmon M.A. SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sc. STKE. 2003;2003:RE12. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.191.re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xiang H., Zhang J., Lin C., Zhang L., Liu B., Ouyang L. Targeting autophagy-related protein kinases for potential therapeutic purpose. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:569–581. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gu S., Cui D., Chen X., Xiong X., Zhao Y.J.B. PROTACs: an emerging targeting technique for protein degradation in drug discovery. Bioessays. 2018;40:1700247. doi: 10.1002/bies.201700247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu D., Wu Y., Wang Y., Ren F., Wang D., Su F., et al. CREPT accelerates tumorigenesis by regulating the transcription of cell-cycle-related genes. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Motavaf M., Safari S., Saffari Jourshari M., Alavian S.M. Hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of the virus X protein. Acta Virol. 2013;57:389–396. doi: 10.4149/av_2013_04_389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Venkatakrishnan B., Zlotnick A. The structural biology of hepatitis B virus: form and function. Annu Rev Virol. 2016;3:429–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim J.H., Sohn S.Y., Benedict Yen T.S., Ahn B.Y. Ubiquitin-dependent and -independent proteasomal degradation of hepatitis B virus X protein. BBRC (Biochem Biophys Res Commun) 2008;366:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ittner L.M., Ke Y.D., Delerue F., Bi M., Gladbach A., van Eersel J., et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Congdon E.E., Sigurdsson E.M. Tau-targeting therapies for alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:399–415. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang C., Ward M.E., Chen R., Liu K., Tracy T.E., Chen X., et al. Scalable production of ipsc-derived human neurons to identify tau-lowering compounds by high-content screening. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:1221–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jiang Z.Y., Lu M.C., Xu L.L., Yang T.T., Xi M.Y., Xu X.L., et al. Discovery of potent Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interaction inhibitor based on molecular binding determinants analysis. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2736–2745. doi: 10.1021/jm5000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Magesh S., Chen Y., Hu L. Small molecule modulators of Keap1-Nrf2-are pathway as potential preventive and therapeutic agents. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:687–726. doi: 10.1002/med.21257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Konstantinidou M., Li J., Zhang B., Wang Z., Shaabani S., Ter Brake F., et al. PROTACs–a game-changing technology. Expet Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14:1255–1268. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2019.1659242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Savitt D., Jankovic J. Targeting alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease: progress towards the development of disease-modifying therapeutics. Drugs. 2019;79:797–810. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cuervo A.M., Stefanis L., Fredenburg R., Lansbury P.T., Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Sci. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bonger K.M., Chen L.C., Liu C.W., Wandless T.J. Small-molecule displacement of a cryptic degron causes conditional protein degradation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:531–537. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fan X., Jin W.Y., Lu J., Wang J., Wang Y.T. Rapid and reversible knockdown of endogenous proteins by peptide-directed lysosomal degradation. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:471–480. doi: 10.1038/nn.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Au Y.Z., Wang T., Sigua L.H., Qi J. Peptide-based PROTAC: the predator of pathological proteins. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wong H.L., Wu X.Y., Bendayan R. Nanotechnological advances for the delivery of cns therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:686–700. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Krishnamurthy N., Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in cancer: update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cui H.K., Zhao B., Li Y., Guo Y., Hu H., Liu L., et al. Design of stapled α-helical peptides to specifically activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell Res. 2013;23:581–584. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xing Y., Clements W.K., Kimelman D., Xu W. Crystal structure of a β-catenin/axin complex suggests a mechanism for the β-catenin destruction complex. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2753–2764. doi: 10.1101/gad.1142603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liao H., Li X., Zhao L., Wang Y., Wang X., Wu Y., et al. A PROTAC peptide induces durable β-catenin degradation and suppresses Wnt-dependent intestinal cancer. Cell Discov. 2020;6:35. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ghidini A., Clery A., Halloy F., Allain F.H.T., Hall J. RNA-PROTACs: degraders of RNA-binding proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2021;60:3163–3169. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]