Abstract

This paper presents a methodological description of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the effect of Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST), a technology-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy (T-CBT) for depression, tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy, compared to an enhanced control condition. Depression is among the most common mental health conditions; yet the majority of adults with depression do not receive needed treatment due to limited access to mental health professionals, treatment-associated costs, distance to care, and stigma. These barriers are particularly salient in rural areas of the United States. T-CBT with human support is an accessible and effective treatment for depression; however, currently available T-CBTs have poor completion rates due to the lack of tailoring and other features to support engagement. ROST is a T-CBT specifically tailored for the rural setting and delivery by clergy, who are preferred, informal providers. ROST also presents core CBT content in a simple, jargon-free manner that supports multiple learning preferences. ROST is delivered virtually in a small group format across 8 weekly sessions via videoconferencing software consistent with other clergy-based programs, such as Bible studies or self-help groups. In this study, adults with depressive symptoms recruited from two rural Michigan counties will be randomized to receive ROST versus an enhanced control condition (N = 84). Depressive symptoms post-treatment and at 3 months follow-up according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) will be the primary outcome. Findings will determine whether ROST is effective for improving depression symptoms in underserved, under resourced rural communities.

Keywords: Rural mental health, Depression, Technology-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy (T-CBT), Clergy, Church setting

1. Introduction

Depression affects approximately 20% of U.S. adults throughout their lifetime [[1], [2], [3], [4]] and is the leading cause of disease burden worldwide [5]. Depression prevalence increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with approximately one-third of U.S. residents experiencing clinically significant symptoms [[6], [7], [8]]. If untreated, depression leads to impairment across multiple life domains [9,10]. Despite high depression prevalence and associated functional impairment, the majority of U.S. residents with depression do not get treatment [1,11]. Depression treatment access disparities are particularly salient in rural communities. Although rural residents experience depression at rates similar to their urban peers [3,[12], [13], [14]], they are significantly less likely to receive treatment [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]].

Treatment access disparities are driven by the lack of mental health providers in rural communities, with approximately 80% of social workers and 90% of psychologists and psychiatrists practicing in urban areas [20,21]. As a result, about 60% of rural residents in the U.S. live in mental health provider shortage areas [22]. The lack of rural providers perpetuates access challenges, including travel burden and distance to care [[23], [24], [25]]. Treatment-associated costs and the high proportion of uninsured and underinsured rural residents present further barriers [26,27]. Even if treatment is available, stigma [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]], perceived lack of anonymity [[33], [34], [35]], and preference for informal care [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]], lead to acceptability concerns that prevent rural residents from seeking mental health services.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a gold-standard evidence-supported psychosocial depression treatment [41,42], is effective when delivered individually, in groups, and with technology [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]]. Despite CBT's effectiveness, it is not widely available in routine treatment settings. Rural residents living with depression are less likely than urban peers to receive guideline-concordant care, like CBT [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19],52].

Technology-assisted CBT (T-CBT) offers promise for disseminating treatment to underserved populations, including rural residents. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the

Need for expanding T-CBT access [53,54]. However, existing T-CBTs for depression present engagement-related challenges [[55], [56], [57], [58]]. Currently available T-CBTs for depression are often text-heavy, academically oriented, and use jargon [55,58], all of which contributes to disengagement and dropout. Additionally, existing T-CBTs for depression are typically designed to be one-size-fits-all and cannot be tailored for client groups, settings, or contexts without substantial cost, time, and effort. This is particularly concerning as tailoring is associated with improved treatment engagement and outcomes [[59], [60], [61], [62]].

T-CBT is more effective with human support than when delivered without support. Meta-analytic review findings show that T-CBTs guided by a support person result in improved treatment adherence rates, comparable to face-to-face CBT [57]. Further, research indicates support for CBT can be effectively provided by non-mental health professionals [[63], [64], [65]]. Therefore, there is potential opportunity to build capacity in rural areas by training preferred, non-mental health providers to support T-CBT users.

Given the need to expand depression treatment access in rural communities, we designed “Raising Our Spirits Together” (ROST), an eight-session, group-based T-CBT tailored for rural adults and delivery by clergy. The present study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of ROST's effect on depressive symptoms, compared to an enhanced control condition (ECC). We also examine ROST's effect on anxiety symptoms as a secondary outcome and explore potential mediators and moderators of treatment effectiveness. This paper describes the methodology of the RCT testing ROST, providing an overview of the study protocol.

2. Method

2.1. Study design

This study uses a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. Eligible participants who are aged 18 and above, screen positive for at least mild depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score ≥ 5), and live in our participating rural communities in Michigan will be randomized

To receive the Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST) depression treatment program or to be part of the Enhanced Control Condition (ECC) that includes usual care and a research-supported depression workbook. All study procedures and materials were approved by an Institutional Review Board.

The two rural counties comprising the geographic catchment area of this study are mental health provider shortage areas, with median incomes lower than the national median income [66]. More than 90% of residents in these counties identify as white [66]. No more than 20% of residents in each county have a bachelor's degree, which is below the national average [66]. The majority of study team members have lived experience or previous practice and research experience in rural communities. All study team members will receive training specific to the rural context.

The RCT allows us to evaluate the preliminary effect of ROST on depressive symptoms, relative to the ECC. The objectives of the current study are to:

Objective 1: Evaluate whether ROST, compared to ECC, decreases depressive symptoms (primary outcome) and anxiety (secondary outcome) among rural adults.

Objective 1 Hypothesis: We hypothesize that ROST participants, compared to ECC participants, will have significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms at post-treatment and three-month follow-up time points.

Objective 2: Explore the relationship between potential mediators and moderators and expected outcomes. Though this RCT is focused on evaluating ROST's preliminary effectiveness and not powered to assess mechanisms of change, we will explore potential mediators and moderators and their relationship to expected outcomes to inform a larger trial of ROST, if results of this RCT are promising.

2.2. Recruitment

Study participants will be recruited from two rural Michigan counties over a 24-month recruitment window. Recruitment will be community-based, using both in-person and

Virtual/web-based strategies to reach potential participants in the participating counties.

Our initially planned recruitment strategies are based on input from our community partners, including clergy and human service providers; however, we will rely on a flexible recruitment approach informed by ongoing collaboration with community partners and our experience on the ground to identify the most acceptable, effective ways to reach potential participants in our target communities.

Our initial recruitment strategies will include posting flyers in community locations (e.g., libraries, coffee shops, grocery stores, dollar stores, restaurants, churches, social service agencies), distributing flyers at food banks, setting up booths at community events, such as farmers markets, fairs, and high school football games, running advertisements on local radio stations, and posting recruitment materials on relevant community websites and social media sites, with specific attention to community Facebook groups. Clergy members leading ROST intervention groups will also distribute flyers at their churches and may directly refer potential participants to the research project. Finally, we will advertise the research study through a university-based online clinical research website that allows community residents to identify research opportunities related to their geography and health and mental health needs.

Study team contact information will be on all recruitment materials. Interested potential participants may contact the study team directly. If our clergy partners refer an individual to the project and the individual is interested in participating, they will have the option of completing a contact form so the study team can contact them at a later time.

Given high rates of mental health stigma in rural communities, all recruitment materials will avoid stigmatizing terms and include diverse images in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, and age, promoting inclusiveness.

If we experience recruitment challenges, we will consider partnering with rural counties adjacent to the counties currently participating in the study in order to increase our catchment area while retaining a focus on increasing access to depression treatment in rural communities.

We will have continued conversations with our community partners about recruitment strategies and, in response to any recruitment difficulties, we will work together to identify new and additional ways of engaging with potential participants in their communities.

2.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are designed to align with our goal of testing ROST in a way that most closely aligns with its potential real-world implementation in underserved rural communities.

To be eligible for inclusion, a participant needs to live in one of two participating rural Michigan counties for at least the past year, screen positive for at least mild depressive symptoms on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) [67], and not currently receiving Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) treatment. Participants taking psychotropic medication may participate. Participants will be advised to continue taking any psychotropic medication according to their clinician/physician's instructions and medication stabilization will not be required for inclusion. Depressive disorder diagnoses, which will be considered in data analysis, will be assessed via structured interview (MINI v. 7)68 but are not required for inclusion. These inclusion criteria increase study access for underserved persons with a range of symptoms, helps fill groups faster, and is most generalizable to real world implementation.

Exclusion criteria include current psychotic symptoms and/or current use of non-prescribed opiates or cocaine that would interfere with study participation, current receipt of CBT for depression (>1 time per month), completion of a prior course of CBT, cognitive impairment that would interfere with study participation, and prominent suicidal or homicidal ideation with imminent risk. Subjects with significant suicide/self-harm or homicide risk must be excluded on ethical grounds and will receive appropriate, immediate resources and referrals.

Since ROST and all study assessments are delivered in English, potential participants who do not speak English are excluded.

ROST was developed to fill an unmet need and lack of services for rural residents experiencing mild to moderate symptoms. When a need for a stepped level of care is identified at any time during study participation, participants will be connected to a licensed clinician on the study team who will assess risk, engage in safety planning when needed, and provide appropriate referrals and resources. Most communities have resources accessible to residents with severe depressive symptoms and/or acute needs, such as suicidal ideation.

Depending on risk level, referrals may be made to crisis services at community mental health, psychiatric emergency services, or to the participants’ primary care provider. This approach is likely replicable in most rural communities. The resources and referrals provided to participants include these local resources as well as telehealth resources and crisis lines (phone and text).

2.4. Random assignment

Eligible participants entering the study will be randomized to ROST or the ECC. Randomization will occur in replicated blocks across conditions. A randomization schedule was created with the assumption that there will be 14 total groups, seven assigned to the ROST treatment condition and seven assigned to the ECC. We expect all groups to have approximately six members. If participant flow prevents timely assembly, smaller groups will be considered to avoid extended delays. Therefore, we also created a supplementary randomization schedule of four groups with two assigned to the ROST treatment group and two assigned to the ECC. The study statistician created the randomization schedule and only one other study team member has access to the randomization schedule. Once a group is enrolled in the study, the condition they are randomly assigned to is revealed to the principal investigator and project coordinator. All study team members conducting post-treatment and follow-up assessments are blinded.

2.5. Assessment

Screening. Individuals interested in participating in this study will either contact the study team independently or will complete a contact form permitting a Research Associate to contact them. Research Associates will communicate with interested participants via phone and will privately explain the purpose of the study. If potential participants are still interested in the study, the Research Associate will invite them to complete an initial phone screening. Research.

Associates will obtain oral consent from potential participants before beginning the initial phone screening.

Potential participants who provide oral consent will complete an initial screening over the phone with a trained Research Associate. The phone screen will include a depression screen (PHQ-2) [69] administered by a trained Research Associate. Potential participants will also be asked screening questions regarding their age, how long they have resided in one of our partnering rural Michigan counties, and their psychosocial treatment history. Given close-knit social networks in rural communities, where potential participants may be randomized to a treatment condition with others they know or know of, the consent process includes a thorough review of our procedures for protecting privacy and confidentiality.

All persons who meet initial eligibility criteria based on screening, including scoring ≥ 2 on the PHQ-2, will be invited to participate in a baseline interview to determine further eligibility. If potential participants are interested in moving forward with study participation, the Research Associate will work with the potential participant to schedule a baseline interview at their convenience. Potential participants will not be remunerated for the screening phase of the study. Reasons for screening and baseline refusal will be collected and coded for use in data analysis.

Baseline Assessment Interview. All participants who meet screening eligibility criteria and consent to participate in the research study, will complete a baseline interview to diagnose depression and comorbid psychiatric conditions and assess other psychometric and demographic variables, including potential mechanisms of change (mediators) and potential moderators (see Table 1). Potential mechanisms of change were informed by existing literature on CBT (e.g., thoughts, behaviors) as well as rural culture (e.g., stigma, social support, openness to accepting help). Existing literature was also used to identify potential moderators, including clinical factors (e.g., depressive symptom severity) and factors specific to ROST's delivery by clergy (e.g., religiosity). Though the current study is not powered for mediation and moderation analyses, including these exploratory measures will help us gain preliminary understanding of potentially important mediators and moderators so that, if this RCT demonstrates the ROST intervention's preliminary effectiveness, these variables can be tested in a larger RCT with longer term follow-up, adequately powered for mediation and moderation analyses.

Table 1.

RCT of ROST v. ECC Measures List and Administration Schedule.

| Category | Measures | Items | Timepoint(s) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [69] (PHQ-2) | 2 | Screening | PR |

| 6-item Mini Mental Status Exam [76] | 6 | Screening | IA | |

| Diagnosis | MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview v. 7 for DSM-V disorders [68] (MINI) | 60+ | BL, PT, FU | DI |

| Symptom Scales | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [67] (PHQ-9) | 10 | BL PT FU; Sessions 1-8 |

PR |

| Generalized Anxiety D-7 [77] (GAD-7) | 7 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Functional Impairment | Sheehan Disability Scale [78] (SDS) | 3 | BL, PT, FU | PR |

| Quality of Life Enjoyment & Satisfaction Questionnaire–SF [79] (Q-LES-SF) | 14 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Mechanisms of Change/Mediators | Thoughts | |||

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire [72] (ATQ) | 30 | Sessions 1-8 | PR | |

| Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale – Short Forms [80] (DAS) | 18 | BL; PT; FU | PR | |

| Behaviors | ||||

| Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale [73] (BADS) | 25 | Sessions 1-8 | PR | |

| Environmental Reward Observation Scale [81] (EROS) | 10 | BL; PT; FU | PR | |

| Stigma | ||||

| Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Scale [82] (PDDS; public stigma) | 12 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale [83] (ISMIS; internal stigma) | 29 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Social Support | ||||

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation List −12 (ISEL-12) [84] | 12 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Willingness to Accept Help | ||||

| Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale – SF [85] | 10 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment [86] | 24 | BL, PT, FU | PR | |

| User Engagement | ||||

| User Engagement Scale -Short Form [90] | 12 | PT | PR | |

| Moderators | Religiosity | |||

| The Duke University Religion Index [89] | 5 | BL | PR | |

| Depression Severity | ||||

| Beck Depression Inventory [89] (BDI) | 21 | BL | PR | |

| Cognitive Therapy Scale: Rating Manual [91] | 13 | Sessions 1-8 | IA | |

| Treatment Fidelity & Adherence | Expectancy Rating 75 | 6 | BL, Session 3 | PR |

| Group Cohesiveness Scale 74 | 7 | Sessions 1,4,8 | PR | |

Abbreviations: PR: Participant Report; DI: Diagnostic Interview; IA: Independent Assessor.

The baseline interview assessment will take approximately 2 h to complete. The interview will be completed over the phone or via secure, web-based videoconferencing software (i.e., Zoom). Participants will receive $25 for completing the baseline interview. All baseline interviews will be completed by Research Associates who have clinical mental health experience and education and have received extensive training in interview-based measures. The baseline assessment is comprehensive and lengthy; however, this assessment was administered in our pilot study of ROST without barriers to participation or adherence [70]. Assessments are scheduled at participants’ convenience with breaks provided as needed.

If participants endorse suicidal ideation on the MINI v. 7,68 the Research Associate will initiate the study's suicide protocol. Research Associates will review participants' risk level in real time based on the MINI's Suicidality Module. If a participant is at low risk, based on the MINI's suicide risk classification, the Research Associate will encourage them to call the local Psychiatric Emergency Service if needed and to discuss feelings with family members or a trusted person in their life. Participants who are at low risk for suicidal ideation will continue participating in the study, with their suicidal ideation monitored regularly to ensure the risk remains low. If a participant is at moderate or high risk for suicidal ideation, the Research Associate will immediately connect them to a licensed clinician on the study team. The licensed clinician will assess risk and develop a safety plan with the participant and the Research Associate. After the plan is developed, it will be documented by the Research Associate who will complete a text-entry action plan via the REDCap survey.

Assessments Throughout Treatment. Participants randomized to the ROST condition will complete a series of measures after each ROST session. The measures will be completed via.

REDCap online survey software. Research Associates will administer the online measures via a link to REDCap surveys distributed via email. Participants access the link and complete surveys after the group, while still in the Zoom “room.” Research Associates will join the Zoom “room” once the session is done to support and monitor survey completion. Participants will complete weekly depression ratings (PHQ-9) to track symptoms during ROST. If participants endorse suicidal ideation on the PHQ-9 (score >0 on Question 9) [67], they will complete the Columbia- Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [71]. C-SSRS scores will be calculated via the REDCap survey software. Research Associates will review participants’ risk level in real time based on their C-SSRS score. If a participant is at low risk, the Research Associate will encourage them to call the local Psychiatric Emergency Service if needed and to discuss feelings with family members or a trusted person in their life. Participants who are at low risk for suicidal ideation will continue participating in ROST sessions and their suicidal ideation will be monitored weekly via the C-SSRS to ensure it remains low. If a participant is at moderate or high risk for suicidal ideation, the Research Associate will immediately connect them to a licensed clinician on the study team. The licensed clinician will assess risk and develop a safety plan with the participant and the Research Associate. Participants randomized to ROST who experience clinical deterioration over time in treatment (as indicated by an increase of 5 points or more on the PHQ-9 for participants with scores of 10 or above) will be contacted by a study team member and referred to local resources that can provide an increased level of care.

Participants will also complete the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire [72] and the Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale [73] after each weekly ROST session. The Group Cohesion Scale [74] will be completed during Sessions 1, 4, and 8 and the Expectancy Rating [75] scale will be completed during Session 3. Participants receive $10 each time they complete these measures at the end of a session.

Post-treatment and Follow-up Assessment Interviews. All participants who meet eligibility criteria based on their baseline assessment interview and are randomized to a treatment condition will be asked to complete assessment interviews at post-treatment (PT) and at 3-month follow-up (FU) timepoints. These assessment interviews will be completed over the phone or via secure, web-based videoconferencing software (i.e., Zoom). Research Associates will administer the same measures at post-treatment and three-month follow-up that were assessed during the baseline interview (see Table 1). Supplemental questions will be asked to participants randomized to the ROST condition who did not respond to the treatment or dropped out of treatment. This will allow us to gather information on intervention acceptability, feasibility, and sustainability. Participants will receive $25 for completing each follow up interview. These interviews will take one and a half to 2 h to complete. The same suicide protocol described in the Baseline Assessment Interview section, above, will be utilized for the post-treatment and three-month follow-up assessment interviews.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Screening

Depression Screening. Individuals interested in participating in the study will complete an initial phone screening that will include the PHQ-2 [69]. The PHQ-2 is a two-question screening tool for depression that asks how frequently, over the last two weeks, individuals have: 1) had little interest or pleasure in doing things and 2) felt down, depressed, or hopeless. Responses range from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3), with scores ranging from zero to six. The PHQ-2 is well-established and widely used, with good construct validity and excellent internal consistency [76]. For this study, if an individual receives a score of 2 or higher on the PHQ-2, they will be asked to schedule a baseline assessment interview to determine study eligibility (See Table 1 for a summary of measures and their administration method).

Screening for Cognitive Impairment. Individuals interested in participating in the study will complete an initial phone screening that includes the 6-item Mini Mental Status Exam [76]. The 6-item Mini Mental Status Exam screens for cognitive impairment and dementia. If an individual gets a score of 4 or higher on the Mini Mental Health Status Exam, they will be asked to schedule a baseline assessment interview to determine study eligibility.

Measure of Suicidal Ideation. The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale – Screen Version [71] will be used to assess suicidal ideation among participants randomized to the ROST treatment condition who endorse anything other than a zero (0) on item 9 of the PHQ-9, when completing measures after each session. The CSSRS – Screen Version is a clinician administered interview that includes six items assessing individuals' suicidal thoughts, method(s), intent, plan, and behaviors. The CSSRS supports clinicians in determining individuals’ suicide risk, based on their severity.

2.6.2. Primary outcome measure

Measure of participants' depressive symptoms. The primary outcome measure for assessing ROST's preliminary effect on depression compared to the ECC is the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [67]. The PHQ-9 is a ten-item measure that assesses depressive symptom severity as a continuous measure. Individuals are asked how frequently, over the last two weeks, they have experienced nine depressive symptoms included in DSM criteria, with responses ranging from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). PHQ-9 scores range from zero to 27, with scores of 10 or above indicating probable Major Depressive Disorder. After the symptom focused questions, there is one additional item, focused on functional impairment, asking individuals to indicate how difficult their depressive symptoms have made it for them to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people. Participants experiencing at least mild depressive symptoms (score ≥ 5 on the PHQ-9) are eligible for participation in this study. The PHQ-9 is a widely used instrument with good construct and criterion validity and excellent internal consistency, shown to effectively measure depression outcomes in response to treatment [67].

2.6.3. Diagnosis

Diagnostic interview. Diagnostic interviews assessing DSM-5 disorders at baseline, post-treatment and 3-month follow up assessment interviews will be conducted using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview v.7 [68]. The MINI will be administered by Research Associates trained to a standard (see 2.7 below). Research Associates conducting post-treatment and three-month follow-up assessment interviews will be blinded to participants’ treatment condition. The MINI is a widely used structured interview with excellent test-retest and interrater reliability [68].

Although the MINI is an extensive diagnostic tool, participants only complete the modules for which they endorse the screening question. Diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder is not required for study eligibility; however, it is important to identify and document participants’ diagnoses, especially since rural adults are an understudied population in mental health intervention and services research. Administering the MINI will allow us to understand co-morbidities among this population and explore their potential impact on intervention effects. Additionally, the MINI will be used to help us identify participants who do not meet inclusion criteria. Finally, though not the primary outcome measure, the MINI allows us to examine the proportion of participants whose diagnostic status changes over time in treatment.

2.6.4. Symptoms scales

Measures of other mental health symptoms. We will assess comorbid anxiety symptoms as a secondary outcome using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [77]. The GAD- 7 is a seven-item measure that asks participants to rate how frequently they experienced anxiety symptoms included in DSM criteria over the last two weeks on a scale ranging from not at all (0) to almost every day (3). Scores range from zero (0) to 21, with scores of 10 or above indicating probable Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). The GAD-7 is a widely used measure with good reliability, as well as good criterion, construct, convergent validity [77].

2.6.5. Functional impairment

Measures of functioning. Overall disability will be measured using Sheehan Disability Scale [78]. The SDS is a commonly used three-item measure of functional impairment that has high internal consistency and construct validity [78]. In addition, we will measure quality of life using the Quality of Life and Enjoyment Questionnaire [79]. This 14-item scale assesses physical health, subjective feelings, leisure activities, social relationships, general activities, satisfaction with medications, and life satisfaction. The Q-LES-Q-SF has good reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change [79].

2.6.6. Mechanisms of change

Measures of Thoughts. Participants’ thoughts will be measured using the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire [72] and the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale – Short Form [80]. The 30-item Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ) will be completed by participants randomized to the.

ROST condition at every ROST treatment session. The ATQ has adequate validity and reliability [72]. The 18-item Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale – Short Form will be completed by participants at the baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow up assessment interviews. The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale – Short Form has adequate psychometric properties [80].

Measures of Behaviors. Participants' behaviors will be measured via the Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale [73] and the Environmental Reward Observation Scale [81]. The BADS, a 25-item measure assessing individuals’ activation over the course of treatment, has good reliability and validity [73]. The measure will be completed by participants randomized to the ROST condition after every ROST treatment session. The EROS is a 10-item measure of increased behavior and positive affect as a consequence of rewarding environmental experiences. The measure, which has strong internal consistency and good construct and convergent validity [81], will be completed by all participants at all three assessment interviews.

Measures of perceived stigma of mental illness. Participants’ perceptions of public mental illness stigma will be measured using the Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Scale [82]. The PDDS is 12-item scale assessing beliefs about public stigma that has adequate reliability and validity [82]. Internalized mental health stigma will be assessed using the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale [83]. The ISMI is a 29-item scale that assesses alienation, stereotype endorsement, perceived discrimination, social withdraw, and stigma resistance. The scale has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability and good construct validity [83].

Measure of Social Support. Social support will be measured using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List −12 [84]. This 12-item measure will be completed by participants at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up assessment interviews. The ISEL-12 has adequate psychometric properties [84].

Measures of Willingness to Accept Help. Participants’ willingness to accept help will be assessed using the 10-item Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale – Short Form [85] and the 24-item Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment [86]. Both measures have adequate reliability and validity and will be completed at baseline, post-treatment, and 3- month follow-up time points [85,86].

Measure of User Engagement. The 12-item User Engagement Scale-Short Form [87] will be used to assess the level of engagement with the ROST intervention among participants randomized to the ROST treatment condition. Elements of user engagement assessed vie the USE-SF include aesthetic appeal, focused attention, perceived usability, and reward. The USE- SF will be completed as part of the post-treatment assessment interview.

2.6.7. Moderators

Measure of Religiosity. The 5-item Duke University Religion Index [88] will be used to assess organizational religious activity, non-organizational religious activity, and subjective religiosity at baseline. The DUREL has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability and good convergent validity [88].

Measure of Depressive Symptom Severity. Depressive symptom severity will be assessed via the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [89]. The BDI is a widely used 21-item scale that assesses depressive symptom severity, with scores ranging from zero to 63. The BDI demonstrates good internal consistency and concurrent validity [89].

2.6.8. Treatment fidelity & adherence

Measures of treatment credibility and beliefs. Treatment expectations will be measured using the Expectancy Rating Scale [75]. This is a four item self-report instrument designed to assess patient expectations regarding change with treatment. The Expectancy Rating Scale will be administered during the baseline assessment interview and again during Session 3 of the ROST intervention so that participants randomized to the ROST condition can report expectations after they have been well socialized to the treatment. The Expectancy Rating Scale has high internal consistency and high test-retest reliability [75].

Measure of group cohesion. We will administer the Group Cohesiveness Scale [74], a 7- item self-report questionnaire assessing perceptions of cohesion and engagement with group members, via a five-point scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree).

The GCS will be administered to participants randomized to the ROST treatment condition after Sessions 1, 4, and 8. The GCS demonstrates high internal consistency [74].

2.6.9. Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic Characteristics. As part of the baseline assessment interview, we will collect sociodemographic information including participants’ gender, date of birth, race/ethnicity, education level, family composition, employment status, and church affiliation.

2.7. Training interviewers

Diagnostic interviewers with clinical experience and mental health education will be trained to complete structured diagnostic interviews using the MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview v. 7 (MINI) [68]. They will be trained by licensed clinicians on the study team who have deep experience conducting MINI assessments via a didactic training course. After completing the didactic training, trainees will rate audio recorded “gold-standard” MINI interviews until they achieve agreement on diagnostic ratings for three consecutive interviews. After matching on three consecutive gold standard MINI interview recordings, each diagnostic interviewer will participate in role play of two diagnostic interviews with a trained interviewer. Finally, the trainee will be observed doing two or more MINI interviews until there is a 90% agreement on the MINI ratings. Audio tapes of diagnostic interviews will be reviewed by two licensed clinicians on the investigative team and ongoing weekly supervisions will be held with all diagnostic interviewers to review tapes, review diagnoses, and address additional training needs.

2.8. Training independent evaluators

To ensure fidelity, an independent assessor (IA: Masters-level clinician with CBT experience and study-specific training) will rate group leader adherence and competence using a version of the Cognitive Therapy Scale: Rating Manual [90] adapted for this study. All RCT sessions will be audio-recorded with participant consent and rated by the IA for treatment adherence and group leader competence. Licensed clinicians on the study team will review audio-recordings and competency ratings. The IA will regularly attend research meetings to discuss findings.

Licensed clinicians on the study team will also provide weekly supervision to group leaders during active ROST treatment groups. Prior to supervision, the licensed clinicians will review session recordings for coverage of content and group leader competence, in order to address any identified issues during weekly supervision with group leaders. We will develop a plan to incorporate missing content into the next session.

2.9. Treatment conditions

Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST). ROST is an 8-session, technology-assisted, group-based CBT for depression that was intentionally designed for the rural context and for delivery by clergy. Clergy facilitate weekly ROST sessions in a way that mirrors small group programming typically offered in church settings, such as Bible studies and support groups. Our team of researchers and community partners felt that the social connection and support from a group format in a non-stigmatizing setting would supersede any anonymity concerns for most participants and would also likely increase openness to future treatment if needed.

ROST uses a combination of video-based educational content, text-based educational content, and a character-driven storyline to introduce core CBT concepts, including psychoeducation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and problem solving. See Table 2 for an overview of ROST session content, in-session activities, and homework exercises. The ROST intervention package also includes a participant workbook and a facilitator manual for group leaders.

Table 2.

Raising our spirits together (ROST) T-CBT depression treatment program overview.

| Session | Core CBT Principle | Session Summary | In-Session Activities and Homework/Action Plans |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low Mood & Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Psychoeducation |

|

Identify Depressive Symptoms Impacting Our Lives Set Goals for Time in Program |

| 2: The Importance of Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

Identify Activities for Enjoyment and Activities for Accomplishment Brainstorm Activities We Did in the Past Activity Scheduling |

| 3: Tools for Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

Identify Activities That Can Be Done Alone, With Others, For Free, and Quickly and Simply Set Activity Goals |

| 4: Identifying Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

Identify Negative Thoughts We Have About Ourselves, Our Situation, and the Future Connect Common Negative Thoughts to Thinking Errors Complete Thought Tracker |

| 5: Talking Back to Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

Evaluate the Accuracy of Our Negative Thoughts Practice Talking Back to Negative Thoughts Complete Thought Record Take Action Based on More Accurate Thoughts |

| 6: Beliefs and Our Mood | Identifying and Challenging Faulty Beliefs |

|

Identify Faulty Beliefs That Aren't Working For Us Complete a Cost-Benefit Analysis of Our Faulty Belief(s) Identify an Action Plan for Combatting Our Faulty Belief(s) |

| 7: Overcoming Setbacks | Problem Solving |

|

Identify a Setback/Potential Setback and its Impact on Our Thoughts and Actions Use Problem Solving Identify Solutions to Address Our Setback/Potential Setback |

| Take Action Based on Solution(s) Selected Using Problem Solving | |||

| 8: Putting It All Together & Relapse Prevention | Program Review and Relapse Prevention |

|

Reflect on Actions Taken During the Program & What We Learned |

|

Reflect on Talking Back to Negative Thoughts & What We Learned | ||

| Reflect on Problem Solving to Overcome Setbacks & What We Learned | |||

| Identify Ways We Will Seek Support for Our Low Mood Now That the Program is Ending |

ROST was created and is housed on the “Entertain Me Well” platform, an online platform developed to deliver CBT in an entertaining, straightforward, widely accessible manner, while allowing treatment customization for client groups, delivery settings, and contexts. Entertain Me Well uses a combination of video, text, audio, and graphics, including a character-driven storyline, to introduce core concepts in a way that supports multiple learning preferences.

Additionally, interactive exercises and homework/action plan exercises are streamlined to be

More intuitive and less academically oriented while focusing on central concepts. For more information about Entertain Me Well see: Weaver et al., 2021[91], Himle et al., 2021 [92].

We employed a community-engaged iterative process to tailor ROST for the rural context and for delivery by clergy. This process involved the selection and integration of images, quotes, vignettes, and examples that are most relevant and relatable for this population and setting. For example, each session begins with a quote from scripture that connects to the core CBT content being delivered that day. We also identify potential activities for behavioral activation in Session 2 and 3 that can be done for easily and for free within the rural context that often lacks resources and infrastructure. Additionally, aspects of rural culture, related to self-reliance and independence, led to the inclusion of “I cannot ask for help” as an example of a faulty belief that is explored in Session 6.

Participants randomized to ROST will complete eight weekly group-based treatment sessions that last for approximately 60 min. ROST will be delivered virtually, via secure, web-based videoconferencing software (i.e., Zoom). Participants and clergy facilitating ROST will join the virtual group sessions, with clergy sharing their screen to show the T-CBT content in a manner similar to a “watch party.” Due to potential concerns about lack of anonymity and privacy among rural residents, clergy take time at the start of the first ROST session to set up group ground rules. One of the ground rules relates to privacy and confidentiality, specifically the expectation that everything discussed in the group, stays in the group. Given the virtual nature of the group, there is also discussion of joining the group sessions from a private space.

Enhanced Control Condition (ECC). An enhanced control condition (ECC) is an appropriate comparison condition for the RCT, given the limited treatment access in participating rural communities. When participants screen positive for depression, there is an ethical obligation to provide resources and referrals. ECC participants will receive a research-supported self-help workbook that provides psychoeducation [93], as well as local resource guides and appropriate referrals. Ongoing risk assessment of ECC participants will occur at post-treatment and three-month follow-up assessment interviews. The suicide risk protocol, described in the Baseline Assessment Interview section, above, will be followed if suicidal ideation is present during any interaction with participants randomized to the ECC.

2.10. ROST group leader training and supervision

Group leaders will complete a training program developed by the study team. First, group leaders will complete a web-based training on CBT for Depression created by Dr.

Kenneth Koback [94]. Next, the group leaders, who are local pastors, will complete one full day of in-person training with licensed clinicians on the study team. The in-person training will include didactic modules on depression, cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, group facilitation skills, and safety planning, as well as interactive case studies and role plays. The group leaders will then complete a second day of in-person training focused on the ROST intervention program's structure and content. The ROST-specific training will include an overview of the technology-assisted program, the facilitator manual, and fidelity ratings. The group leaders will be asked to role play core components of the intervention (i.e., behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving) as well as key group leader roles/responsibilities, including introducing in-session activities, leading weekly check-ins, and reviewing action plans/homework. At the end of the second day of in-person training, group leaders will complete the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Knowledge Questionnaire [95]. Gaps in knowledge will be addressed as needed by the study team.

Throughout the RCT, the group leaders will receive ongoing supervision and training. All ROST sessions will be audio recorded. The audio recordings will be reviewed by licensed clinicians on the study team. Licensed clinicians on the study team will hold weekly supervision with group leaders during active ROST treatment groups to review session audio tapes and address additional training needs.

2.11. Data analysis plan

The primary outcome measure for assessing ROST's preliminary effect on depression relative to an ECC is the PHQ-9. Analyses will adjust for baseline scores to increase precision. Other baseline covariates will be examined for association with outcome variables. Those accounting for change in the estimated treatment effect will be retained in final analyses to optimize power and precision [96]. As ROST is group-based, with participants blocked on time of screening prior to randomization, individuals' observations cannot be assumed to be independent. Due to this possible lack of statistical independence between participants in the same group, mixed linear (multilevel) growth modeling [97] will be used to test for the preliminary effect of ROST relative to ECC on depressive symptoms. Mechanisms of change will be explored by adding variables targeted by the intervention (e.g., thoughts, behaviors, stigma) as time-varying covariates to multilevel models predicting the course of depression over time [98]. To explore the possibility that treatment effects may differ for those presenting with low versus high religiosity and moderate versus severe depression, baseline religiosity and baseline depression severity will be examined as potential moderators.

Although this RCT is not powered for mediation or moderation tests, effect sizes from these analyses will inform future fully powered research testing ROST. Analyses will be “intent-to- treat,” as all subjects undergoing randomization will be included, and we will use multiple imputation methods [99] to handle data missing at follow-up. Sensitivity analyses will be used to examine the influence of missingness on findings.

2.12. Sample size and power analysis

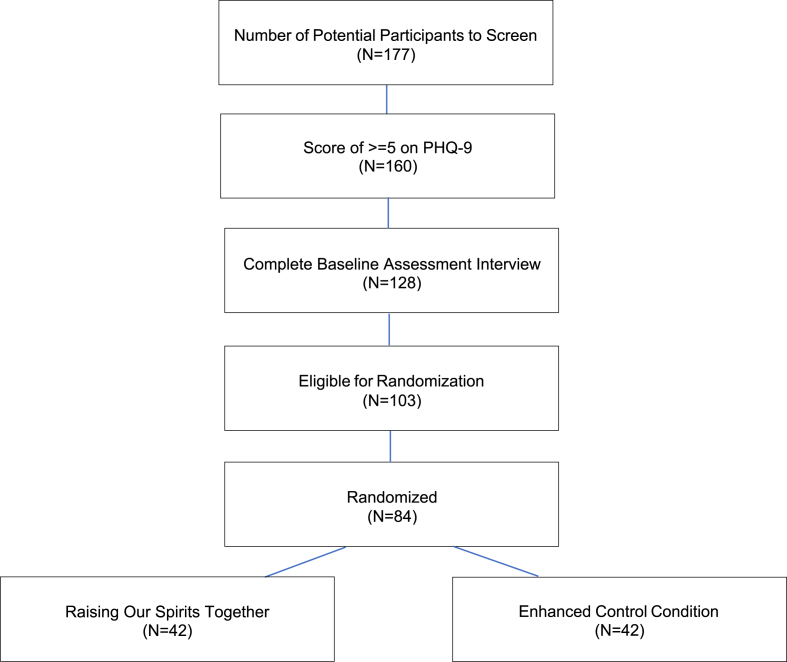

We expect to recruit 128 participants, 84 of whom we anticipate will enroll, i.e., enter the study after randomization to one of the arms. We expect to screen 177 persons, with 90% of those persons meeting screening criteria, providing informed consent, and agreeing to a baseline assessment interview (N = 160). Of those 160 participants, we expect 80% who complete baseline assessment interviews will meet eligibility criteria (N = 128). We expect 80% of those 128 participants to be randomized to a treatment condition (N = 103). Of those randomized to a treatment condition, we expect 82% (N = 84; ROST = 42; ECC = 42) to participate in their assigned condition and be included in the RCT (see Fig. 1 for expected participant flow). These expectations are informed by study team members’ prior research conducted in underserved, under-resourced settings, including rural communities.

Fig. 1.

Expected ROST CONSORT flow diagram.

A sample of 84 subjects who participate in their study condition after randomization should provide power of .80 to find a significant (at 2-tailed p < .05) comparative effect size for an intervention change of d = 0.80 or above, which is within the range found in meta-analyses of technology-assisted CBT with human support [43,45].

2.13. Trial status

The randomized controlled trial of ROST versus the ECC began in September 2020 and is currently underway. We anticipate that enrollment in the active phase of the study will be completed in 2022. Follow-up assessments are in progress and will conclude in 2022 as well. This project was approved by an institutional review board and the trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04502186). We developed a comprehensive participant safety protocol that provides participants same-day contact with a licensed clinician on the study team for suicidality, homicidality, clinical deterioration, or any other safety-related concerns.

3. Discussion

There is great potential to use technology to increase mental health treatment access, and the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the feasibility of offering care remotely [53,54]. However, treatment access disparities remain among underrepresented and underserved groups, including rural residents [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. Given the myriad of barriers to care experienced by rural residents [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]], including the lack of local mental health professionals [[20], [21], [22]], it is imperative to investigate ways to develop capacity to deliver treatment in community settings where rural residents naturally go for help. T-CBT with human support has demonstrated comparable effectiveness to face-to-face CBT for treating depression [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47],57]; however, user engagement with existing T-CBT programs have been negatively impacted by their text-heavy, academic nature and one-size-fits-all approach [[55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62]]. This study seeks to address these depression treatment access disparities in rural areas by evaluating the effectiveness of an innovative, entertaining T- CBT for depression, Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST), tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy.

If ROST is effective in improving depressive symptoms compared to the ECC, the findings from this study have the potential for a wide-spread public health impact in rural areas. First, leveraging existing community resources, such as clergy, to deliver needed depression treatment offers an important community-level approach to building capacity and increasing access to care in a way that is feasible and acceptable. ROST's delivery by clergy aligns with rural residents' preference for seeking mental health treatment from informal systems of care, including clergy [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Additionally, delivery by clergy likely lessens the stigma that rural residents' commonly have around mental health needs and treatment [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. Further, the community-engaged approach to developing and tailoring ROST resulted in specific attention to packaging and delivering ROST in way that is designed to fit with clergy's practice patterns and bandwidth. Specifically, ROST is delivered in a small group format that mirrors the format of other small group programs and studies led by clergy. If ROST is effective, the intervention model can be replicated in a larger hybrid effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial [100] that identifies and tests implementation strategies, as well as evaluates clinical outcomes.

Second, this study leverages technology in way that is likely acceptable for rural adults with depression and has the potential for broad dissemination via clergy in rural communities. ROST is delivered virtually, by a preferred informal provider, using videoconferencing software. This delivery format is similar to a watch party and offers a unique way to build group cohesion, community, and support, with the use of technology. As many churches moved to virtual worship services and programming and human service organizations moved to virtual appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic, ROST's delivery format was consistent with what both clergy and community members were experiencing across a variety of contexts. When thinking about ROST's potential broader implementation and dissemination, more attention to technology access, both highspeed/broadband internet and devices, is needed. That said, leveraging technology offers important opportunities to reduce mental health treatment barriers related to cost, insurance status [26,27], travel, distance to care [[23], [24], [25]], and stigma [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]] that are often experienced by rural residents. ROST's virtual delivery allows rural residents to receive evidence-supported depression treatment without engaging with formal services, which likely reduces concerns about lack of anonymity that are common in rural communities.

Third, this study provides an important opportunity to increase our knowledge of the effectiveness of T-CBT for depression supported by non-mental health professionals in rural areas. Few studies have tested CBT for depression in rural settings in the United States. All existing studies of CBT for depression delivered in rural settings included intervention adaptations; however, most studies did not assess treatment fidelity of the modified treatments [101]. Additionally, most studies utilized single group trial designs or quasi-experimental designs, which limits our understanding of the effect of adapted CBT for depression in rural communities in the U.S. [101]. This study addresses some of these gaps by clearly defining and describing the ROST T-CBT program, including treatment tailoring, employing a rigorous randomized controlled trial design, and incorporating a comprehensive process for assessing fidelity.

There are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. First, the population is limited to those in two rural Michigan counties and may not generalize to other regions or communities. Second, the study primarily focuses on depression, as it is one of the most common mental health conditions and is a risk factor for poor outcomes including suicide. That said, our focus on depression meant we were unable to expand the intervention to address other mental health diagnoses. Third, this study began during the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; however it was designed prior to the pandemic and therefore, impacts of the pandemic on rural residents’ mental health or the potential increased need for mental health services could not have been anticipated and are not accounted for in the methods. Fourth, this study included an extensive assessment battery that, although critical to establishing feasibility, preliminary effectiveness, and exploring potential mediators and moderators, is not sustainable for real world implementation of ROST by clergy. Our team of researchers and community partners believe a small number of low burden assessments can be employed by clergy for ROST implementation. Further attention to this issue is needed and warranted. Finally, participants who are reluctant to utilize electronic communication or experience barriers to accessing adequate information technology might be missed.

4. Conclusion

This RCT of ROST compared to an ECC will evaluate the effects of this innovative, entertaining, tailored T-CBT on depressive symptoms among rural adults. It the RCT reveals that ROST can be successfully delivered virtually by clergy and if it reduces rural adults’ depressive symptoms, it will have potentially important public health impacts given the considerably negative consequences of untreated depression and the lack of available, accessible, and acceptable treatment resources in rural areas of the United States.

We feel that the current trial is particularly significant in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated need for virtual mental health treatment that can be feasible and sustainably offered in low-resource settings. The mental health service system in many rural communities across the United States has limited infrastructure and does not have the resources to meet care needs. Additionally, given rural residents’ preferences for informal treatment, it is critical to identify ways to build capacity among existing community resources where residents naturally go for help with depression. It is likely that our intervention model, leveraging group-based technology-supported CBT with support from clergy, a preferred, local provider, may offer a promising solution for increasing access to depression treatment in rural areas.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [K01MH110605].

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the U.S.Department of Veterans Affairs.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K.R., Walters E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Koretz D., Merikangas K.R., Rush A.J., Walters E.E., Wang P.S. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler R.C., McGonagle K.A., Zhao S., Nelson C.B., Hughes M., Eshleman S., Wittchen H.-U., Kendler K.S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasin D.S., Sarvet A.L., Meyers J.L., Saha T.L., Ruan W.J., Stohl M., Grant B.F. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatr. 2018;75:336–346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich M.J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA. 2017;317 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826. 1517-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., Weaver M.D., Robbins R., Facer-Childs E.R., Barger L.K., Czeisler C.A., Howard M.E., Rajaratnam S.M. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.) 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Glob. Health. 2020;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marciniak M.D., Lage M.J., Dunayevich E., Russell J.M., Bowman L., Landbloom R.P., Levine L.R. The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress. Anxiety. 2005;2:178–184. doi: 10.1002/da.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P.S., Berglund P.A., Kessler R.C. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv. Res. 2003;38:647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olfson M., Blanco C., Marcus S.C. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176:1482–1491. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blazer D.G., Kessler R.C., McGonagle K.A., Swartz M.S. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the national comorbidity survey. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Probst J.E., Laditka S.B., Moore C.G., Harun N., Powell M.P., Baxley E.G. Rural-urban differences in depression prevalence: implications for family medicine. Fam. Med. 2006;38:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J.L. Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Soc Pyschiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortney J.C., Harman J.S., Xu S., Dong F. The association between rural residence and the use, type, and quality of depression care. J. Rural Health. 2010;26:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley D., Bird D., Dempsey P. In: Rural Health in the United States. Ricketts T., editor. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. Mental health and substance abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauenstein E.J., Peddada S.D. Prevalence of major depressive episodes in rural women using primary care. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:185–202. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang P.S., Lane M., Olfson M., Pincus H.A., Wells K.B., Kessler R.C. Twelve- month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2005;62:629–639. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P.S., Demler O., Olfson M., Pincus H.A., Wells K.B., Kessler R.C. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2006;163:1187–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis A.R., Konrad T.R., Thomas K.C., Morrissey J.P. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009;60:1315–1322. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawyer D., Gale J., Lambert D. National Association for Rural Mental Health; Waite Park, MN: 2006. Rural and Frontier Mental and Behavioral Health Care: Barriers, Effective Policy Strategies, Best Practices. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Resources and Services Administration . Bureau of Health Workforce; 2019. Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas.https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amundson B. America's rural communities as crucibles for clinical reform: establishing collaborative care teams in rural communities. Fam. Syst. Health. 2001;19:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gjesfjeld C.D., Weaver A., Schommer K. Rural women's transitions to motherhood: understanding social support in a rural community. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2012;15:435–448. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan M.F. The President's New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003;54:1467–1474. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proctor B.D., Semega J.L., Kollar M.A. U. S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2016. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015 (Current Population Reports) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . 2017. Geography of Poverty.https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-econo my-population/rural-poverty-well- being/geog raphy-of-poverty.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buckwalter K.C. In: The Elderly with Chronic Mental Illness. Light E., Lebowitz E., editors. Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY: 1991. The chronically mentally ill elderly in rural environments; pp. 216–231. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crumb L., Mingo T.M., Crowe A. vol. 13. Mental Health & Prevention; 2019. pp. 143–148. (Get over it and Move on”: the Impact of Mental Illness Stigma in Rural, Low-Income United States Populations). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill C.E., Fraser G.J. Local knowledge and rural mental health reform. Community Ment. Health J. 1995;31:553–568. doi: 10.1007/BF02189439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rost K., Smith G.R., Taylor J.L. Rural-urban differences in stigma and the use of care for depressive disorders. J. Rural Health. 1993;9:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1993.tb00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheffler M.J. Culturally sensitive research methods of surveying rural/frontier residents. West. J. Nurs. Res. 1999;21:426–435. doi: 10.1177/01939459922043866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logan T.K., Stevenson E., Evans L., Leukefeld C. Rural and urban women's perceptions of barriers to health, mental health, and criminal justice services: implications for victim services. Violence Vict. 2004;19:37–62. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.1.37.33234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rost K., Fortney J., Fischer E., Smith J. Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2002;59:231–265. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smalley K.B., Yancey C.T., Warren J.C., Naufel K., Ryan R., Pugh J.L. Rural mental health and psychological treatment: a review for practitioners. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010;66:479–489. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox J.C., Blank M., Rovnyak V.G., Barnett R.Y. Barriers to help seeking for mental disorders in a rural impoverished population. Community Ment. Health J. 2001;37:421–436. doi: 10.1023/a:1017580013197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox J.C., Merwin E.I., Blank M. De facto mental health services in the rural south. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 1995;64:434–468. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merwin E., Hinton I., Dembling B., Stern S. Shortages of rural mental health professionals. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2003;17:42–51. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merwin E., Snyder A., Katz E. Differential access to quality rural healthcare: professional and policy challenges. Fam. Community Health. 2006;29:186–194. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weaver A., Himle J., Elliott M., Hahn J., Bybee D. Rural residents' depressive symptoms and help-seeking preferences: opportunities for church-based intervention development. J. Relig. Health. 2019;58:1661–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craske, date.

- 42.David D., Cristea I., Hofmann S.G. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatr. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrews G., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrews G., Basu A., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., English C.L., Newby J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018;55:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butler A.C., Chapman J.E., Forman E.M., Beck A.T. The empirical status of cognitive-behavior therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuijpers P., Noma H., Karyotaki E., Cipriani A., Furukawa T.A. Effectiveness and acceptability of cognitive behavioral therapy delivery formats in adults with depression: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatr. 2019;76:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Firth J., Torous J., Nicholas J., Carney R., Pratap A., Rosenbaum S., Sarris J. The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatr. 2017;16:287–298. doi: 10.1002/wps.20472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hofmann S.G., Asnaani A., Vonk I.J., Sawyer A.T., Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2012;36:427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J., Theng Y.-L., Foo S. Game-based digital interventions for depression therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014;17:519–527. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright J.H., Owen J.J., Richards D., Eells T.D., Richardson T., Brown G.K., Barrett M., Rasku M.A., Polser G., Thase M.E. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2019;80:18r12188. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18r12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang A., Bornheimer L.A., Weaver A., Franklin C., Hai A.H., Guz S., Shen L. Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary care depression and anxiety: a secondary meta- analytic review using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. J. Behav. Med. 2019;42:1117–1141. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hepner et al., 2017.

- 53.Wind T.R., Rijkeboer M., Andersson G., Riper H. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic: the ‘black Swan’for Mental Health Care and a Turning Point for E-Health; p. 20. Internet interventions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaebel W., Stricker J. E‐mental health options in the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;78:441–442. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farvolden P., Denisoff E., Selby P., Bagby R.M., Rudy L. Usage and longitudinal effectiveness of a Web-based selfhelp cognitive behavioral therapy program for panic disorder. J. Med. Internet Res. 2005;7:e7. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez E., Salem D., Swift J.K., Ramtahal N. Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: magnitude, timing, and moderators. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83:1108. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Ballegooijen W., Cuijpers P., Van Straten A., Karyotaki E., Andersson G., Smit J.H., Riper H. Adherence to Internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waller R., Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol. Med. 2009;39:705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrera M., Jr., Castro F.G., Strycker L.A., Toobert D.J. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013;81:196. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krebs P., Prochaska J.O., Rossi J.S. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev. Med. 2010;51:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morrison L.G. Theory-based strategies for enhancing the impact and usage of digital health behaviour change interventions: a review. Digital Health. 2015;1 doi: 10.1177/2055207615595335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noar S.M., Benac C.N., Harris M.S. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:673. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roy-Byrne P., Craske M.G., Sullivan G., Rose R.D., Edlund M.J., Lang A.J.…Stein M.B. Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Himle J.A., Bybee D., Steinberger E., Laviolette W.T., Weaver A., Vlnka S., Golenberg Z., Levine D.S., Heimberg R.G., O'Donnell L.A. Work-related CBT versus vocational services as usual for unemployed persons with social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;63:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang A., Bornheimer L.A., Weaver A., Franklin C., Hai A.H., Guz S., Shen L. Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary care depression and anxiety: a secondary meta- analytic review using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. J. Behav. Med. 2019;42:1117–1141. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Census Bureau U.S. 2020. American Community Survey Quick Facts: 2016-2020 5 Year Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sheehan D.V. 2015. M.I.N.I. MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview. English Version 7.0.0 for DSM–5. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weaver A., Zhang A., Landry C., Hahn J., McQuown L., O'Donnell L.A., et al. Technology-assisted, group-based CBT for rural adults' depression: open pilot trial results. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2022;32:131–145. doi: 10.1177/10497315211044835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Posner K., Brent D., Lucas C., Gould M., Stanley B., Brown G.…Mann J. vol. 10. Columbia University Medical Center; New York, NY: 2008. (Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hollon S.D., Kendall P.C. Cognitive self-statements in depression: development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1980;4:383–395. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanter J.W., Mulick P.S., Busch A.M., Berlin K.S., Martell C.R. The Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale (BADS): psychometric properties and factor structure. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007;29:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wongpakaran T., Wongpakaran N., Intachote-Sakamoto R., Boripuntakul T. The group cohesiveness scale (GCS) for psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr. Care. 2013;49:58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2012.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Borkovec T.D., Nau S.D. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatr. 1972;4:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mini-Mental Status Exam.

- 77.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sheehan D.V., Harnett-Sheehan K., Raj B.A. The measurement of disability. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1996;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Endicott J., Nee J., Harrison W., Blumenthal R. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beck A.T., Brown G., Steer R.A., Weissman A.N. Factor analysis of the dysfunctional attitude scale in a clinical population. Psychol. Assess.: J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;3:478. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Armento M.E., Hopko D.R. The environmental reward observation scale (EROS): development, validity, and reliability. Behav. Ther. 2007;38:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Link B. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am. Socio. Rev. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]