Abstract

The bacterial cell wall, whose main component is peptidoglycan (PG), provides cellular rigidity and prevents lysis from osmotic pressure. Moreover, the cell wall is the main interface between the external environment and internal cellular components. Given its essentiality, many antibiotics target enzymes related to the biosynthesis of cell wall. Of these enzymes, transpeptidases (TPs) are central to proper cell wall assembly and their inactivation is the mechanism of action of many antibiotics including β-lactams. TPs are responsible for stitching together strands of PG to make the crosslinked meshwork of the cell wall. This chapter focuses on the use of solid-phase peptide synthesis to build PG analogs that become site-selectively incorporated into the cell wall of live bacterial cells. This method allows for the design of fluorescent handles on PG probes that will enable the interrogation of substrate preferences of TPs (e.g. amidation at the glutamic acid residue, crossbridge presence) by analyzing the level of probe incorporation within the native cell wall of live bacterial cells.

Keywords: Acyl acceptor, Bacteria, Peptidoglycan, Synthetic stem peptide, Tripeptide

1. Introduction

Peptidoglycan (PG) is a fundamental component of bacterial cell walls and is therefore often the target of antibiotics (Vollmer, Blanot & de Pedro 2008b; Vollmer, Blanot & De Pedro 2008a; Typas et al. 2011). The basic PG unit is comprised of repeating disaccharides of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) that are modified with a short stem peptide. Although there are variations with the stem peptide primary sequence, it is typically composed of l-Ala-d-isoGlx-l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala, where Glx indicates glutamine or glutamic acid (Vollmer, Blanot & De Pedro 2008a). These units become polymerized by transglycosylation and transpeptidation (TP) reactions that crosslink the sugar and peptide moieties, respectively. Combined, these processes create a rigid meshwork that supports the cell wall structure and function. Covalent crosslinking of the PG scaffold is essential to maintain proper cell wall integrity (Vollmer & Holtje 2004; Sharif et al. 2013). As such, the sensitivity of this crosslinking step has been exploited by nature and drug discovery programs for the generation of antibiotics. Antibiotics (e.g., β-lactams, vancomycin, teixobactin) operate in diverse modes, including covalent modification of the active site and substrate sequestration, to impair the processing of nascent PG building blocks. Historically, these classes of antibiotics have been extremely successful in the treatment against bacterial pathogens. However, as bacteria are rapidly becoming resistant to current antibiotics (Ventola 2015), there is a need for improved methods to treat infections caused by pathogens. Despite the established utility in targeting PG crosslinking, there are fundamental aspects that remain poorly defined. We envision that chemical probes of PG crosslinking could complement biological methods to better elucidate the biology of cell wall assembly.

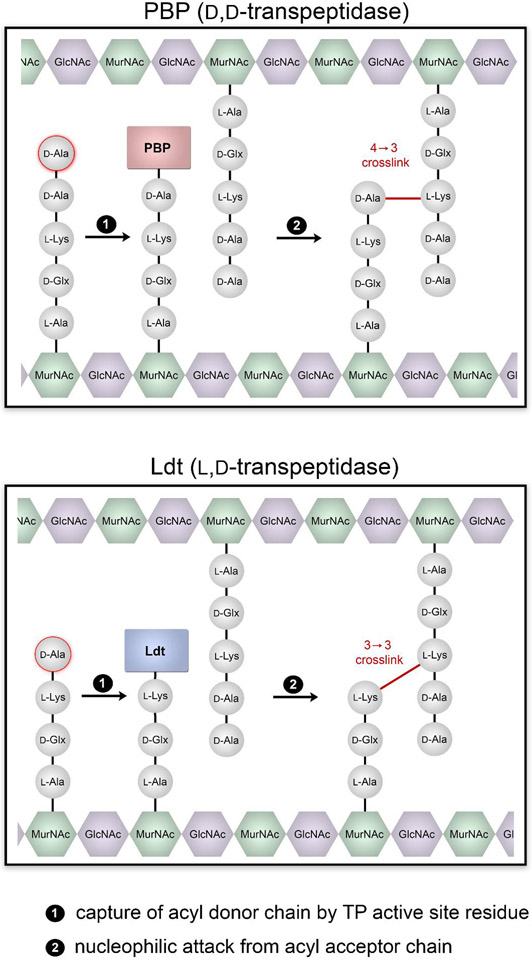

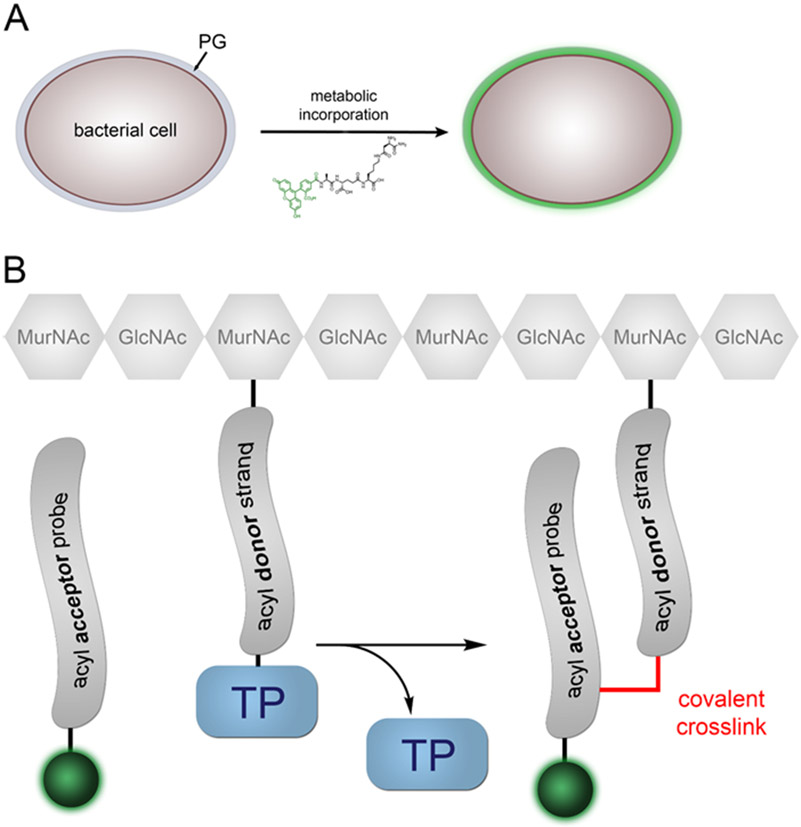

PG crosslinking enzymes are mainly classified as penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), also termed d,d-transpeptidases (d,d-TPs), or as l,d-TPs (Ldts). d,d-TPs initiate crosslinking by a nucleophilic attack of an active site serine at a pentameric acyl donor strand between the terminal d-Ala-d-Ala motif. The transpeptidase reaction then proceeds by a nucleophilic attack of an amino group at the third position l-Lys of an acceptor strand. The end result is that these enzymatic steps will generate a 4-3 crosslink across two PG stem peptides (Fig. 1). As the name implies, Ldts catalyze the reaction between a terminal l-Lys-d-Ala motif on a tetrapeptide donor strand by an active site cysteine. The second step of the reaction (the acyl-transfer step) requires that an amino group displaces the activated acyl-enzyme intermediate (Fig. 1). The subsequent steps are similar, with the principal difference being the generation of a 3-3 crosslink (Lupoli et al. 2011a).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the two primary modes of PG crosslinking. In the top, the PBP mediated crosslinking modality is depicted and the final crosslinking configuration is 4-3. In the bottom, crosslinking carried out by Ldts result in a 3-3 crosslinking configuration.

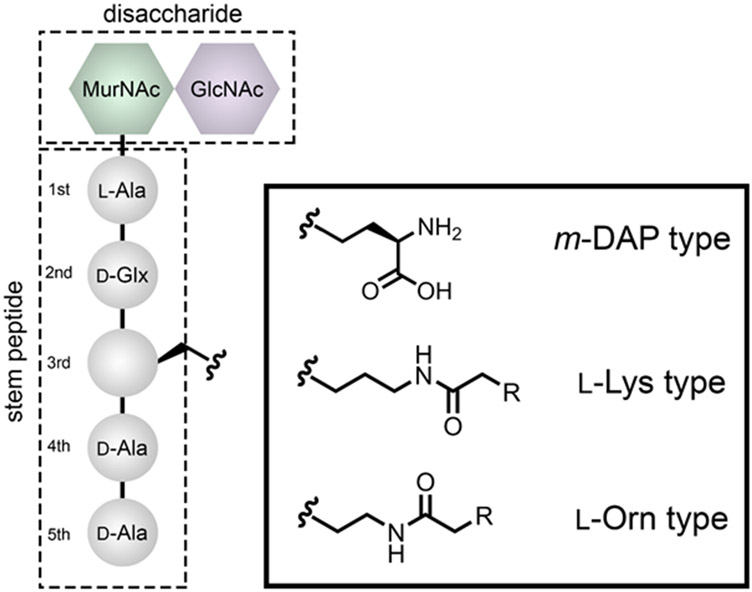

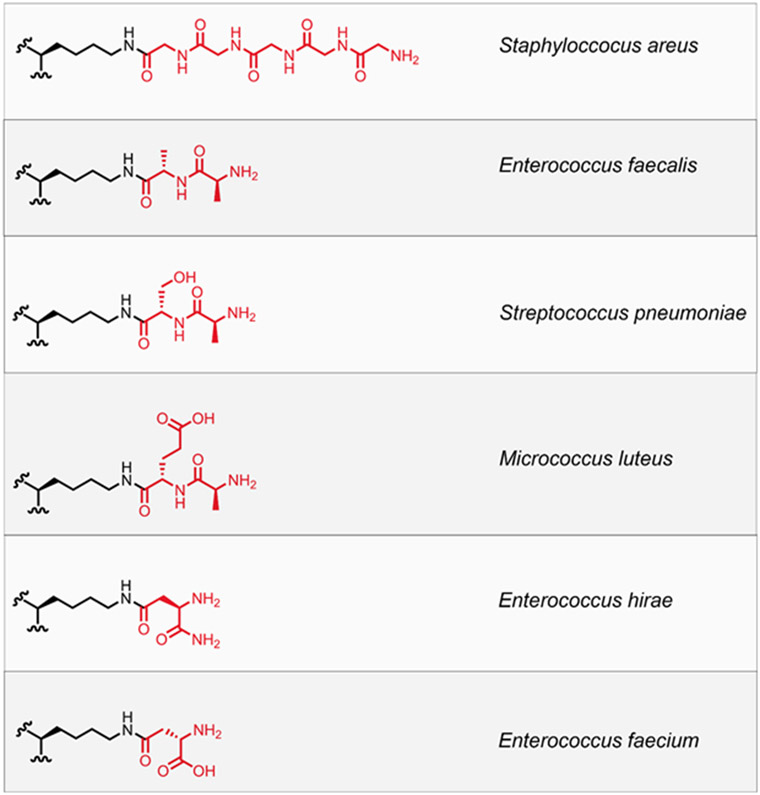

Across all known bacteria, the nucleophilic amino group is found in the 3rd position of the stem peptide. Considerable diversity in the 3rd position has been observed across various bacterial species (Fig. 2) (Schleifer & Kandler 1972b; Vollmer, Blanot & de Pedro 2008b). Distinctly, a large number of Gram-negative organisms, mycobacteria, and some Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium difficile) have a meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP) residue at the 3rd position instead of l-Lys. The major structural difference between l-Lys and m-DAP is the inclusion of a carboxylic acid in m-DAP. Although structurally subtle, this alteration has important biological implications in PG sensing. It was previously demonstrated that vegetative Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) release fragments of PG into the culture medium to trigger a synchronized germination of spores upon sensing of PG by the receptor PrkC (Shah et al. 2008; Dworkin 2014). PG fragments containing l-Lys failed to initiate germination, whereas the inclusion of the carboxylic acid in m-DAP led to a potent nanomolar level response (Squeglia et al. 2011). Relatedly, cell wall fragments released by bacteria released during cellular growth and division, which are known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), can be utilized by immune receptors to detect the possible presence of pathogens in a host (Wolf & Underhill 2018). In particular, the intracellular receptor in the host called nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1 (NOD1) is highly stimulated by fragments of PG containing m-DAP but not l-Lys (Strober et al. 2006). Further diversity within m-DAP has been observed in various bacterial types, namely the amidation at the sidechain carboxyl of m-DAP (Warth & Strominger 1971; Mahapatra et al. 2008; Bernard et al. 2011; Espaillat et al. 2016). Although a subtle chemical change, amidation of m-DAP can confer a selective advantage to type 6 secretion systems (Espaillat et al. 2016) and evade detection by the pattern recognition receptor that recognizes PG fragments (Vijayrajratnam et al. 2016; Wolf & Underhill 2018).

Fig 2.

Variation of the type of amino acid found in the 3rd position within the stem peptide in bacterial PG. While there are other amino acids that naturally populate this position, for the large majority of bacteria characterized to date, they are derivatives of m-DAP, l-Lys, and l-Orn.

Other amino acids found in the 3rd position include l-Ornithine that is observed in Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, which has an acetylated glycine at the amino sidechain (Beck, Benach & Habicht 1990). For a large number of Gram-positive bacteria, the third position amino acid is a l-Lys. Interestingly, the PG from nearly all bacteria that have been analyzed do not have a l-Lys alone. The lysine residue is further acylated with various amino acids (e.g., l-Ala, Gly, l-Thr, d-Glu, d-Ser, etc.), a fragment that is typically referred to as the crossbridge (Stranden et al. 1997). Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium) adds a crossbridge to the 3rd position with d-iAsx (where Asx indicates asparagine or aspartic acid)(de Jonge, Gage & Handwerger 1996), Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) modifies this position with l-Ala-l-Ala, and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) modifies l-Lys with up to 5 Gly residues (Schleifer & Kandler 1972a). The unique nature of the crossbridge can impart significant biological effects. In the case of bacteriophage, these chemical features can provide a host-specific fingerprint as was recently observed for a family of bacteriophage that infects Lactobacillus casei (Regulski et al. 2013). Similarly, competing bacteria can leverage the crossbridge to target their foes as demonstrated by the biosynthesis of lysostaphin, which specifically cleave the crosslinking pentaglycine bridge, by Staphylococcus simulans (Schindler & Schuhardt 1964; Mitkowski et al. 2019). Another important aspect of the crossbridge is that, for most organisms, this structural modification appears to be essential for cellular viability. In S. aureus, the biosynthesis of the pentaglycine crossbridge involves 3 individual enzymes: FemX, FemA, and FemB (Maidhof et al. 1991; Henze et al. 1993; Monteiro et al. 2019). The pentaglycine crossbridge was recently shown to be essential for S. aureus cell integrity (Tschierske et al. 1999; Monteiro et al. 2019). Moreover, isolated PG fragments of one, three, and five glycine units were processed to varying levels by PBPs, which indicates that the number of glycine units can impact crosslinking levels (Srisuknimit et al. 2017a).

In general, TPs in the metabolic pathway of bacterial cell wall components have proven to have promiscuous recognition of their substrates in PG biosynthesis. As such, the treatment of cells with cell wall precursors or cell wall analogs can result in metabolic incorporation of these probes in cell wall building blocks. The tolerance of a wide range of variants within these metabolic probes provide a range of functional handles (e.g., fluorophores, click chemistry handles, hapten, biotin, etc) that can be selectively installed within the PG. Prior works have shown that single d-amino acid PG probes can be used to gain insight into the crosslinking of PG in live bacterial cells biology (Lupoli et al. 2011b; Kuru et al. 2012; Siegrist et al. 2013; Fura, Sabulski & Pires 2014; Lebar et al. 2014; Fura, Kearns & Pires 2015; Kuru et al. 2015; Pidgeon et al. 2015; Siegrist et al. 2015; Pidgeon & Pires 2017b; Pidgeon et al. 2019b; Apostolos, Pidgeon & Pires 2020). Our own research group has extensive experience in this area (Fura, Sabulski & Pires 2014; Fura, Kearns & Pires 2015; Fura & Pires 2015; Pidgeon et al. 2015; Pidgeon & Pires 2015; Sarkar & Pires 2015; Sarkar et al. 2016; Pidgeon & Pires 2017b; Pidgeon & Pires 2017a; Pidgeon & Pires 2017c). Additionally, full-length PG stem peptides have also been used in vitro and in vivo as probes of PG biosynthesis. A semi-synthetic method was described in 2013 to build m-DAP containing lipid II to analyze the glycosyltransferase and transpeptidase activities of PBP1A and PBP1B from Escherichia coli (Lebar et al. 2013). A recent improvement on the protocol related to lipid II production and isolation has streamlined the isolation of lipid II from Gram-negative and -positive bacteria (Qiao et al. 2017). Isolated lipid II from S. aureus was used to determine the number of Gly on the crossbridge required for TP activity to crosslink strands (Srisuknimit et al. 2017b), and to investigate substrate preferences of low molecular weight PBPs (Welsh et al. 2017). Fully synthetic PG precursors were also used in vitro to demonstrate the importance of amidation of the stem peptide for crosslinking by Ldts (Ngadjeua et al. 2018). A fluorescent stem peptide mimic using l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala as the recognition motif was shown to be accepted by bacterial PG machinery and labeled the cell walls of live S. aureus cells (Gautam et al. 2015), albeit fewer studies have been performed in live cells with stem peptide replicates. Our group has demonstrated how synthetic PG stem peptides can: (1) target specific classes of PG transpeptidases (Pidgeon et al. 2019b), (2) modulate immune responses (Dalesandro & Pires 2021), (3) analyze the remodeling of cross-bridges(Apostolos, Pidgeon & Pires 2020), and (4) be platforms to probe the mimicry of m-DAP (Apostolos et al. 2020). A major advantage of using synthetic analogs of PG stem peptides is the ability to systematically assess how structural alterations can impact the metabolic processing of PG in live bacterial cells.

1.1. Rationale

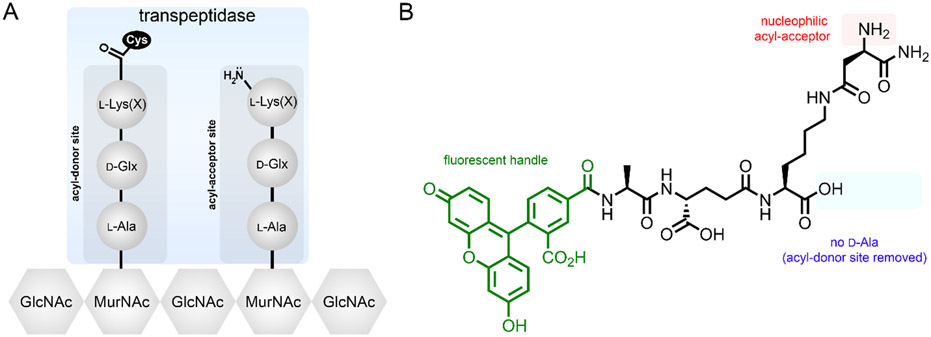

The use of synthetic stem peptide probes provides a versatile platform to design and develop tools to understand how chemical remodeling of PG (e.g., amidation, crossbridge modification, etc.) can modulate crosslinking levels in live bacterial cells. With access to probes that target specifically acyl-acceptor or acyl-donor activity, a method can be established to study and interrogate TP substrate preferences (Fig. 4A). Here, we highlight the synthesis and use of fluorescent stem peptide mimetics that provide a means to interrogate potential endogenous PG structural modifications and how those modifications affect their incorporation into the cell wall meshwork.

Fig. 4.

General strategy to hijack the PG crosslinking machinery. (A) As shown, the active site of Ldts has a cysteine residue that forms a covalent thioester intermediate with the acyl donor strand. Next, the nucleophilic amino group on the acyl-acceptor strand displaces the thioester to form a stable amide bond. An analogous process happens for PBPs, with the main difference being the length of the stem peptide and the active site residue (serine instead of cysteine). (B) Basic structure of one of the tripeptide probes used to interrogate crossbridge preferences. Note that the crossbridge retains the nucleophilic amino group that will be the acyl-acceptor site. Also, the tripeptide is devoid of any d-Ala residues within the stem peptide, which forces the probe to be processed at the acyl-acceptor site. Finally, the fluorescent moiety is installed at the N-terminus, a site that tolerates non-natural modifications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, equipment, and reagents

All peptide related reagents (resin, coupling reagents, deprotection reagents, amino acids, and cleavage reagents) were purchased from ChemImpex and were used without further purification.

25 mL peptide synthesis vessel, coarse, 2 mm PTFE (purchased from Chemglass Life Sciences)

Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-Wang resin

Cannonical and noncannoncal amino acids with corresponding protecting groups (see synthesis for more details)

5(6)-carboxyfluorescein

20% piperidine in dimethylformamide (DMF)

Methanol

Dichloromethane (DCM)

Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA)

N, N, N’,N’-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uranium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU)

0.5 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

50 mL conical tubes (sterile, polypropylene)

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

Triisopropylsilane (TIPS)

Ice-cold diethyl ether

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer pH 8.4

E. faecium D344S grown in liquid brain heart infustion (BHI), a gift from Dr. Arthur (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Institut Pasteur)

E. faecalis 29212 (grown in liquid BHI), S. aureus SC01 (grown in lysogeny broth, LB), Lactobacillus casei (L. casei, grown in Difco lactobacilli MRS broth) were from the Pires laboratory glycerol stocks

Lactococcus lactis (L. lactis) ATCC 11454 grown in liquid BHI purchased from ATCC

Formaldehyde

14 mL polypropylene round-bottom tube (for culturing)

1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (conical bottom, sterile)

1 mL (volume size) sterilized U-bottom 96-well plates for culturing

400 μL (volume size) sterile 96-well U-bottom plates for washing cells and flow analysis

Centrifuge (standard rotor and rotor for 96-well plates)

High-performance liquid chromatographer (HPLC)

C8(2) reversed-phase column

Mass spectrometer (MS)

Lyophilizer

UV-VIS Spectrophotometer

Cuvettes

Shaking incubator

Flow cytometer

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of fluorescent tripeptides

Tripeptide mimetics were synthesized by solid-phase peptide synthesis with modifications at the second position, d-isoGlx (where Glx is either glutamine or glutamic acid) and at the epsilon amine of l-Lys (to mimic the endogenous crossbridge found in each bacterial strain assayed). A tripeptide (l-Ala-d-isoGlx-l-Lys) was chosen as the model probe due to the fact that it acts strictly as an acyl-acceptor in the catalyzed TP mechanism since it lacks the terminal d-Ala required to be an acyl-donor (Fig. 4B). Our previous work had demonstrated that a tetrapeptide probe with the epsilon amine of Lys acetylated acts strictly as an acyl-donor (Pidgeon et al. 2019a).

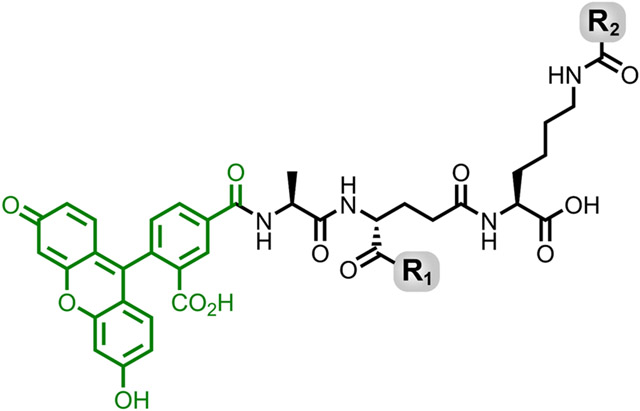

Briefly, Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-Wang resin was used as the solid support, and standard peptide coupling procedures were followed to build the l-Ala-d-isoGlx-l-Lys scaffold. The N-terminus was modified with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein to track incorporation of each probe into the PG. Removal of the Mtt group with 1% TFA in DCM yielded a free amine on resin at the second position for coupling with the desired crossbridge amino acid to provide a library of tripeptide derivatives. The library included all probes with the basic scaffold of a tripeptide (Fig. 5) and they are individually listed in Table 1.

Fig. 5.

Basic chemical structure of all tripeptide probes investigated.

Table 1:

Tripeptide derivatives synthesized for each bacterial strain studied.

| E. faecium | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| TriQK | NH2 | H |

| TriEN | OH | d-iAsn |

| TriQN | NH2 | d-iAsn |

| TriQD | NH2 | d-iAsp |

| TriQNac | NH2 | d-iAsn(NAc) |

| E. faecalis | R1 | R2 |

| TriQK | NH2 | H |

| TriQAA | NH2 | l-Ala-l-Ala |

| TriQaa | NH2 | d-Ala-d-Ala |

| TriQAAac | NH2 | l-Ala-l-Ala(NAc) |

| TriEAA | OH | l-Ala-l-Ala |

| S. aureus | R1 | |

| TriQK | NH2 | |

| TriQG1-6 | (Gly)1-6 |

2.2.1.1. Protocol

Charge a 25 mL peptide vessel with 250 mg of Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-Wang resin (0.14 mmol).

Remove the Fmoc protecting group of Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-Wang resin with 15 mL 20% piperidine in DMF for 30 minutes with agitation at room temperature.

Wash the resin with 15 mL of DCM and methanol (3 times with each solvent). Add Fmoc-d-glutamic acid α-amide (3 eq, 152 mg, 0.42 mmol) for Gln peptides or Fmoc-d-glutamic acid-tert-butyl ester (3 eq, 175 mg, 0.42 mmol) for Glu peptides, HBTU (3 eq, 156 mg, 0.42 mmol), and DIEA (6 eq, 0.144 mL, 0.84 mmol) in DMF (15 mL) to the peptide vessel. Shake the vessel for 2 hours at ambient temperature.

Wash the resin with 15 mL of DCM and methanol (3 times with each solvent). Continue the synthesis as described, by removing Fmoc groups with 20% piperidine, washing the resin, and adding the sequential amino acids.

As the final residue, couple 2 equivalents of 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (103 mg, 0. 28 mmol) with HBTU and DIEA and agitate the resin overnight. The following morning, wash the resin with DCM and methanol (as before). Additionally, wash the resin with 0.5 M NaOH to remove residual fluorescein.

To modify the Lys crossbridge, remove the Mtt protecting group with 10 mL of 1% TFA in DCM and let the vessel shake for 15 minutes. Repeat this step 3 more times.

Add the desired amino acid(s) for the crossbridge to the vessel with HBTU, DIEA, and DMF (a slight excess of DIEA may be necessary at this step as residual TFA may linger) and let the vessel shake for 2 hours. Wash the resin as before, couple any additional amino acids or remove final Fmoc-protecting groups before cleaving the peptide from solid support.

To cleave the peptide from resin, transfer the resin to a 50 mL conical tube. Add a solution of 95% TFA, 2.5% deionized water, and 2.5% TIPS to the tube and rotate it at ambient temperature for 2 hours.

Filter the resin and concentrate the resulting solution under a stream of nitrogen until less than 5 mL of liquid remains.

Add 30-35 mL of ice-cold diethyl ether to the conical tube and triturate to crash out the desired peptide.

Collect the peptide at 2,300 g for 10 minutes. Discard the diethyl ether. Purify the resulting peptide.

2.2.2. Purification of fluorescent peptides

Each probe was purified using a Waters 600 controller and pump with a reversed phase C8(2) column and absorbance monitored at 220 nm with the following method: flow rate 10 mL/min, injection 3 mL, eluant A 100% H2O with 0.1% TFA and eluant B 100% methanol with 0.1% TFA. Inlet file (A/B): 0-7 min 95/5, 7-70 min 0/100, 70-85 min 95/5. Peaks were collected and the identity of each compound was confirmed using mass spectrometry (MS). Individual collections of samples were lyophilized to yield purified products. Stocks were made in deionized H2O and concentration was characterized in 0.1M NaHCO3 buffer pH 8.4 by measure of the absorbance at 492 nm and ε = 75,000 for 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein.

The intent of Glu and Gln probes were to assess if modifications to the amidation state of the stem peptide were tolerated by TPs in a live cell when the substrate was only an acyl-acceptor. Unmodified and acetylated Lys sidechains were intended to be used as negative controls since they would lack the endogenous crossbridge, or the free amine necessary for transpeptidation would be blocked. Within the peptides designed for E. faecium, the d-isoAsn amidation state was interrogated with Asp, and the d-Ala-d-Ala crossbridge was designed to test the importance of the l-Ala-l-Ala stereochemistry at the Lys sidechain in E. faecalis. In S. aureus, varying lengths of the Gly crossbridge (1, 3, and 5) have been shown to be accepted by TPs to different levels in vitro (Srisuknimit et al. 2017b). The tripeptides with Gly residues 1-6 were designed to assay the preference of these varying sidechain lengths by live cell machinery.

2.2.3. Substrate specificity of TP enzymes in live bacterial cells

The substrate specificity of TP enzymes was assayed by incubating live cells from stationary phase cultures diluted 1:100 in fresh media with 100 μM of each probe overnight to allow incorporation of the probes into the PG. For probes that become incorporated as part of the PG, the incubation step should result in the fluorescent tagging of the PG scaffold (Fig. 6A). The analog of the acyl-acceptor strand should become covalently crosslinked into the PG matrix, should the crossbridge be recognized by the PG transpeptidase machinery (Fig. 6B). The level to which each probe was accepted by TP machinery, thus providing insight on TP substrate preferences, could then be assessed by quantification via flow cytometry. These levels would provide insight on how primary sequences of the acyl-acceptor strand modulate the amount of crosslinking within the cell wall.

Fig 6.

Live cell assay with tripeptide probes. (A) Incubation of live cells with tripeptide probes could lead to labeling of the PG scaffold for the tripeptide probes that are readily accepted by the PG crosslinking machinery. (B) Schematic diagram showing how the tripeptide, acyl-acceptor mimics, can be incorporated by the transpeptidase (TP) machinery.

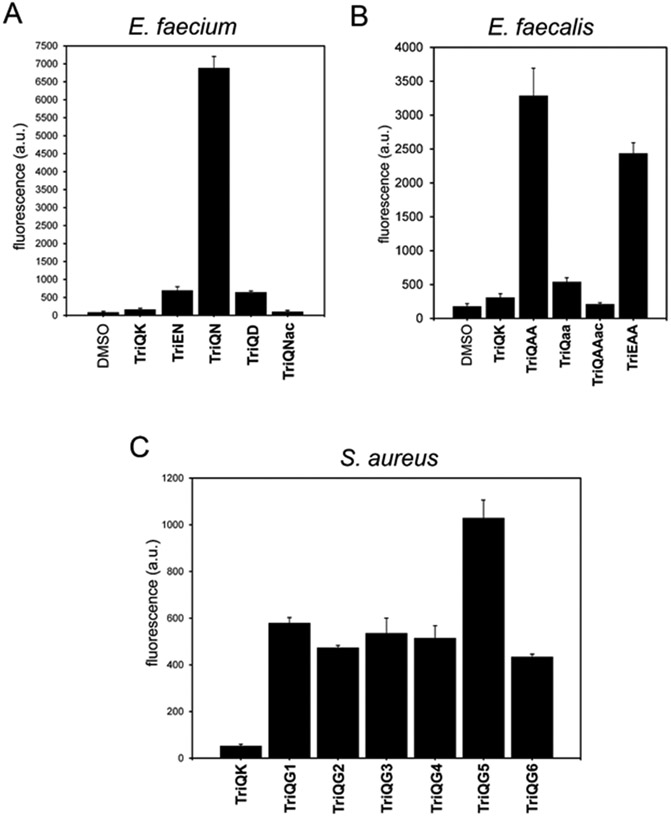

In E. faecium cells, TP machinery generally appeared to have a preference for TriQN, where the d-iAsn crossbridge is present and d-iGlx is amidated (Gln), over TriQK which lacked the native sidechain modification. Additionally, lack of amidation at the crossbridge (i.e. d-iAsp) and at the d-iGlx backbone (d-iGlu) led to near-background levels of fluorescence, indicating that amidation at these sites is important for PBP and Ldt enzyme recognition of acyl-acceptor substrates. Importantly, these preferences that are imperative for crosslinking of the PG strands could suggest the importance of Aslfm, the enzyme that appends the β-carboxyl group of d-iAsx (leaving the α-carboxyl group free and sometimes amidated) to the Lys sidechain in bacterial cells, as a potential drug target (Staudenbauer & Strominger 1972). Further, this reveals the preference of d-iGlx amidation for E. faecium TPs, which to this point remained unresolved in terms of impact on processing at the acyl-acceptor site, although in vitro characterization suggested lack of amidation at this site impaired PG crosslinking (Zapun et al. 2013; Ngadjeua et al. 2018). The crossbridge presence (d-iAsn) was demonstrated to be the nucleophilic amino group involved in acyl-acceptor activity, as blocking it with acetylation (TriQNac) led to background levels of fluorescence.

In E. faecalis cells, tripeptide probes containing the native l-Ala-l-Ala crossbridge were preferentially incorporated into the PG, regardless of the amidation state of d-iGlx. Similar to the findings in E. faecium cells, the presence of the crossbridge for the acyl-acceptor strand to be recognized by TPs could highlight the potential therapeutic target of BppA1 and BppA2, ligases that transfer the first and second l-Ala to the ε-amine of Lys (Bouhss et al. 2002). Baseline fluorescence of TriQaa and TriQAAac highlighted stereospecificity of the acyl-acceptor position at the l-Ala-l-Ala crossbridge and demonstrated that the endogenously mimicked crossbridge was the nucleophilic amino group involved in acyl-acceptor activity. S. aureus TP substrate presence was investigated next, where addition of just one Gly residue on the sidechain of Lys led to preferential labeling as compared to unmodified Lys. Crossbridges of 2-5 Gly had comparable labeling levels and extending to 6 Gly did not seem to impact crosslinking largely, suggesting a level of flexibility in the acceptor strand for the cell.

To test the substrate specificity of TP enzymes in live bacterial cells, utilize the protocol outlined below.

2.2.3.1. Protocol

Generate stationary phase cultures of each strain in their respective media from a frozen glycerol stock. Briefly, dip a sterilized pipette tip into a frozen glycerol stock of the strain of interest and eject the tip into 5 mL of liquid media in a 14 mL polypropylene round-bottom tube (sterile).

Prepare media supplemented with 100 μM of the desired probe (diluted from a master stock that has been previously characterized as described in section 2.2.2) in sterile microcentrifuge tubes. To prepare to perform the assay in triplicate, with each well of a 1 mL volume 96-well plate containing 200 μL of media, prepare slightly more than 600 μL of the media with each probe.

Aliquot 200 μL of the media (blank and with each probe, 3 wells per each condition) into the 1 mL volume 96-well plate. Prewarm the media for 5 minutes at 37°C.

From the stationary phase culture, dilute cells 1:100 in the 200 μL of media that has been aliquoted and prewarmed in the 96-well plate.

Allow the cells to grow overnight in a shaking incubator at 37°C and 250 RPM.

Transfer the cells and media to a sterile 96-well plate (400 μL volume) and centrifuge the plate at 2,700 g for 4 min to harvest the cells.

Decant the supernatant and resuspend cells in 200 μL of 1X PBS, followed by centrifugation to wash (same conditions as step 6). This step should be repeated for a total of three iterations.

After the final wash, resuspend cells in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Allow the cells to sit at room temperature for 30 min (protected from light to prevent photobleaching) before washing for a final time.

Resuspend the cells in 1X PBS and dilute cells to an appropriate concentration for analysis by flow cytometry. Typically, a 40-fold dilution of cells (from the 200 μL suspension) in fresh PBS provides an amenable rate of events per second as analyzed by the flow cytometer.

Monitor the fluorescence of each sample by recording a minimum of 10,000 events per sample within the gated population set on the forward-scatter-area (FSC-A) versus side-scatter-area (SSC-A) plot. For bacterial cells, these axes should be set in the logarithmic scale. Additionally, monitor the FITC-height (H) versus counts for each sample in a histogram plot. Record the mean FITC-H for the gated population. Take the average of all three samples and determine the standard deviation for error. For 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein labeled cells, the AttuneNxT flow cytometer with a 488 nm blue laser and 488/10 nm bandpass filter was used.

2.2.4. Troubleshooting and Optimization

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Anticipated mass of peptide product not observed |

|

| No/sluggish bacterial cell growth |

|

| Bacterial cells that previously labeled with Fl-probe (particularly iAsn crossbridge probes) are showing near-background fluorescence levels |

|

| Events collected by the flow cytometer are too few per sample to reach 10,000 |

|

| FITC-H vs. counts histogram does not show a single, clean peak or there appears to be two distinct populations in the scatter |

|

3. Summary

Transpeptidation reactions are critical for cell wall crosslinking to ensue. As such, TP enzymes are largely the target of antibiotics. PG stem peptide strands are the substrates for TPs, but subtle alterations to their primary sequence have seldom been studied in live bacterial cells. Here, we outline a method to use stem peptide mimetic probes with a fluorescent handle to directly assay the preferences of TPs in vivo. This process paved the way for sought after information regarding the amidation state of the PG strand, as well as the importance of the crossbridge for acyl-acceptors. In combination with our prior work that explained the use of acyl-donor probes (Pidgeon et al. 2019a), these two methods of thought in conjunction can assay the enzymatic preferences of each strand in whole cells.

Fig. 3.

Examples of crossbridges found in bacteria that incorporate an l-Lys within the 3rd position of the stem peptide in PG. The chemical structure is shown on the left and the bacterial species is accompanied on the right side. It should be noted that there can be additional chemical modifications to the crossbridges shown (e.g., amidation and addition of other amino acids).

Fig. 7.

Results from live cell labeling with the specified tripeptide probes. Flow cytometry analysis of E. faecium (A), E. faecalis (B), and S. aureus (C) treated overnight with 100 μM of tri-peptide probes. Data are represented as mean + SD (n = 3).

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by GM124893-01 (M.P).

References

- Apostolos AJ, Nelson JM, Silva JRA, Lameira J, Achimovich AM, Gahlmann A, Alves CN & Pires MM (2020) Facile Synthesis and Metabolic Incorporation of m-DAP Bioisosteres Into Cell Walls of Live Bacteria. ACS Chem Biol, 15, 2966–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolos AJ, Pidgeon SE & Pires MM (2020) Remodeling of Cross-bridges Controls Peptidoglycan Cross-linking Levels in Bacterial Cell Walls. ACS Chem Biol, 15, 1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck G, Benach JL & Habicht GS (1990) Isolation, preliminary chemical characterization, and biological activity of Borrelia burgdorferi peptidoglycan. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 167, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard E, Rolain T, Courtin P, Hols P & Chapot-Chartier MP (2011) Identification of the amidotransferase AsnB1 as being responsible for meso-diaminopimelic acid amidation in Lactobacillus plantarum peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol, 193, 6323–6330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhss A, Josseaume N, Severin A, Tabei K, Hugonnet J-E, Shlaes D, Mengin-Lecreulx D, van Heijenoort J & Arthur M (2002) Synthesis of the l-Alanyl-l-alanine Cross-bridge of Enterococcus faecalis Peptidoglycan*. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277, 45935–45941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalesandro BE & Pires MM (2021) Induction of Endogenous Antibody Recruitment to the Surface of the Pathogen Enterococcus faecium. ACS Infect Dis, 7, 1116–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge BL, Gage D & Handwerger S (1996) Peptidoglycan composition of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Microb Drug Resist, 2, 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J (2014) The medium is the message: interspecies and interkingdom signaling by peptidoglycan and related bacterial glycans. Annu Rev Microbiol, 68, 137–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espaillat A, Forsmo O, El Biari K, Bjork R, Lemaitre B, Trygg J, Canada FJ, de Pedro MA & Cava F (2016) Chemometric Analysis of Bacterial Peptidoglycan Reveals Atypical Modifications That Empower the Cell Wall against Predatory Enzymes and Fly Innate Immunity. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 138, 9193–9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fura JM, Kearns D & Pires MM (2015) D-Amino Acid Probes for Penicillin Binding Protein-based Bacterial Surface Labeling. J Biol Chem, 290, 30540–30550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fura JM & Pires MM (2015) D-amino carboxamide-based recruitment of dinitrophenol antibodies to bacterial surfaces via peptidoglycan remodeling. Biopolymers, 104, 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fura JM, Sabulski MJ & Pires MM (2014) D-amino acid mediated recruitment of endogenous antibodies to bacterial surfaces. ACS Chem Biol, 9, 1480–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Kim T, Shoda T, Sen S, Deep D, Luthra R, Ferreira MT, Pinho MG & Spiegel DA (2015) An Activity-Based Probe for Studying Crosslinking in Live Bacteria. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 54, 10492–10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze U, Sidow T, Wecke J, Labischinski H & Berger-Bachi B (1993) Influence of femB on methicillin resistance and peptidoglycan metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol, 175, 1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru E, Hughes HV, Brown PJ, Hall E, Tekkam S, Cava F, de Pedro MA, Brun YV & VanNieuwenhze MS (2012) In Situ probing of newly synthesized peptidoglycan in live bacteria with fluorescent D-amino acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 51, 12519–12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru E, Tekkam S, Hall E, Brun YV & Van Nieuwenhze MS (2015) Synthesis of fluorescent D-amino acids and their use for probing peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial growth in situ. Nat Protoc, 10, 33–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebar MD, Lupoli TJ, Tsukamoto H, May JM, Walker S & Kahne D (2013) Forming Cross-Linked Peptidoglycan from Synthetic Gram-Negative Lipid II. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135, 4632–4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebar MD, May JM, Meeske AJ, Leiman SA, Lupoli TJ, Tsukamoto H, Losick R, Rudner DZ, Walker S & Kahne D (2014) Reconstitution of peptidoglycan cross-linking leads to improved fluorescent probes of cell wall synthesis. J Am Chem Soc, 136, 10874–10877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupoli TJ, Tsukamoto H, Doud EH, Wang T-SA, Walker S & Kahne D (2011a) Transpeptidase-mediated incorporation of D-amino acids into bacterial peptidoglycan. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133, 10748–10751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupoli TJ, Tsukamoto H, Doud EH, Wang TS, Walker S & Kahne D (2011b) Transpeptidase-mediated incorporation of D-amino acids into bacterial peptidoglycan. J Am Chem Soc, 133, 10748–10751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra S, Crick DC, McNeil MR & Brennan PJ (2008) Unique structural features of the peptidoglycan of Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol, 190, 655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidhof H, Reinicke B, Blumel P, Berger-Bachi B & Labischinski H (1991) femA, which encodes a factor essential for expression of methicillin resistance, affects glycine content of peptidoglycan in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Bacteriol, 173, 3507–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitkowski P, Jagielska E, Nowak E, Bujnicki JM, Stefaniak F, Niedzialek D, Bochtler M & Sabala I (2019) Structural bases of peptidoglycan recognition by lysostaphin SH3b domain. Sci Rep, 9, 5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro JM, Covas G, Rausch D, Filipe SR, Schneider T, Sahl HG & Pinho MG (2019) The pentaglycine bridges of Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan are essential for cell integrity. Sci Rep, 9, 5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngadjeua F, Braud E, Saidjalolov S, Iannazzo L, Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Hugonnet JE, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Patin D, Ethève-Quelquejeu M, Fonvielle M & Arthur M (2018) Critical Impact of Peptidoglycan Precursor Amidation on the Activity of l,d-Transpeptidases from Enterococcus faecium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chemistry, 24, 5743–5747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE, Apostolos AJ, Nelson JM, Shaku M, Rimal B, Islam MN, Crick DC, Kim SJ, Pavelka MS, Kana BD & Pires MM (2019a) L,D-Transpeptidase Specific Probe Reveals Spatial Activity of Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking. ACS Chemical Biology, 14, 2185–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE, Apostolos AJ, Nelson JM, Shaku M, Rimal B, Islam MN, Crick DC, Kim SJ, Pavelka MS, Kana BD & Pires MM (2019b) L,D-Transpeptidase Specific Probe Reveals Spatial Activity of Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking. ACS Chem Biol, 14, 2185–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE, Fura JM, Leon W, Birabaharan M, Vezenov D & Pires MM (2015) Metabolic Profiling of Bacteria by Unnatural C-terminated D-Amino Acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 54, 6158–6162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE & Pires MM (2015) Metabolic remodeling of bacterial surfaces via tetrazine ligations. Chem Commun (Camb), 51, 10330–10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE & Pires MM (2017a) Cell Wall Remodeling by a Synthetic Analog Reveals Metabolic Adaptation in Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci. ACS Chem Biol, 12, 1913–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE & Pires MM (2017b) Cell Wall Remodeling of Staphylococcus aureus in Live Caenorhabditis elegans. Bioconjug Chem, 28, 2310–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon SE & Pires MM (2017c) Vancomycin-Dependent Response in Live Drug-Resistant Bacteria by Metabolic Labeling. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 56, 8839–8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y, Srisuknimit V, Rubino F, Schaefer K, Ruiz N, Walker S & Kahne D (2017) Lipid II overproduction allows direct assay of transpeptidase inhibition by beta-lactams. Nat Chem Biol, 13, 793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski K, Courtin P, Kulakauskas S & Chapot-Chartier MP (2013) A novel type of peptidoglycan-binding domain highly specific for amidated D-Asp cross-bridge, identified in Lactobacillus casei bacteriophage endolysins. J Biol Chem, 288, 20416–20426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Libby EA, Pidgeon SE, Dworkin J & Pires MM (2016) In Vivo Probe of Lipid II-Interacting Proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 55, 8401–8404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S & Pires MM (2015) d-Amino acids do not inhibit biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One, 10, e0117613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CA & Schuhardt VT (1964) Lysostaphin: A New Bacteriolytic Agent for the Staphylococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 51, 414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer KH & Kandler O (1972a) Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriological reviews, 36, 407–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer KH & Kandler O (1972b) Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriological reviews, 36, 407–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah IM, Laaberki MH, Popham DL & Dworkin J (2008) A eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinase signals bacteria to exit dormancy in response to peptidoglycan fragments. Cell, 135, 486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif S, Kim SJ, Labischinski H, Chen J & Schaefer J (2013) Uniformity of glycyl bridge lengths in the mature cell walls of fem mutants of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol, 195, 1421–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist MS, Swarts BM, Fox DM, Lim SA & Bertozzi CR (2015) Illumination of growth, division and secretion by metabolic labeling of the bacterial cell surface. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 39, 184–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist MS, Whiteside S, Jewett JC, Aditham A, Cava F & Bertozzi CR (2013) (D)-Amino acid chemical reporters reveal peptidoglycan dynamics of an intracellular pathogen. ACS Chem Biol, 8, 500–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeglia F, Marchetti R, Ruggiero A, Lanzetta R, Marasco D, Dworkin J, Petoukhov M, Molinaro A, Berisio R & Silipo A (2011) Chemical basis of peptidoglycan discrimination by PrkC, a key kinase involved in bacterial resuscitation from dormancy. J Am Chem Soc, 133, 20676–20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisuknimit V, Qiao Y, Schaefer K, Kahne D & Walker S (2017a) Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking Preferences of Staphylococcus aureus Penicillin-Binding Proteins Have Implications for Treating MRSA Infections. J Am Chem Soc, 139, 9791–9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisuknimit V, Qiao Y, Schaefer K, Kahne D & Walker S (2017b) Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking Preferences of Staphylococcus aureus Penicillin-Binding Proteins Have Implications for Treating MRSA Infections. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139, 9791–9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudenbauer W & Strominger JL (1972) Activation of d-Aspartic Acid for Incorporation into Peptidoglycan. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 247, 5095–5102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranden AM, Ehlert K, Labischinski H & Berger-Bachi B (1997) Cell wall monoglycine cross-bridges and methicillin hypersusceptibility in a femAB null mutant of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol, 179, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A & Watanabe T (2006) Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat Rev Immunol, 6, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschierske M, Mori C, Rohrer S, Ehlert K, Shaw KJ & Berger-Bachi B (1999) Identification of three additional femAB-like open reading frames in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 171, 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA & Vollmer W (2011) From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat Rev Microbiol, 10, 123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventola CL (2015) The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 40, 277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayrajratnam S, Pushkaran AC, Balakrishnan A, Vasudevan AK, Biswas R & Mohan CG (2016) Bacterial peptidoglycan with amidated meso-diaminopimelic acid evades NOD1 recognition: an insight into NOD1 structure-recognition. Biochem J, 473, 4573–4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W, Blanot D & De Pedro MA (2008a) Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 32, 149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W, Blanot D & de Pedro MA (2008b) Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 32, 149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W & Holtje JV (2004) The architecture of the murein (peptidoglycan) in gram-negative bacteria: vertical scaffold or horizontal layer(s)? J Bacteriol, 186, 5978–5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth AD & Strominger JL (1971) Structure of the peptidoglycan from vegetative cell walls of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry, 10, 4349–4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MA, Taguchi A, Schaefer K, Van Tyne D, Lebreton F, Gilmore MS, Kahne D & Walker S (2017) Identification of a Functionally Unique Family of Penicillin-Binding Proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139, 17727–17730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AJ & Underhill DM (2018) Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol, 18, 243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A, Philippe J, Abrahams KA, Signor L, Roper DI, Breukink E & Vernet T (2013) In vitro Reconstitution of Peptidoglycan Assembly from the Gram-Positive Pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. ACS Chemical Biology, 8, 2688–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]