ABSTRACT

Anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME), which oxidize methane in marine sediments through syntrophic associations with sulfate-reducing bacteria, carry homologs of coenzyme F420-dependent sulfite reductase (Fsr) of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, a hyperthermophilic methanogen from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. M. jannaschii Fsr (MjFsr) and ANME-Fsr belong to two phylogenetically distinct groups, FsrI and FsrII, respectively. MjFsrI reduces sulfite to sulfide with reduced F420 (F420H2), protecting methyl coenzyme M reductase (Mcr), an essential enzyme for methanogens, from sulfite inhibition. However, the function of FsrIIs in ANME, which also rely on Mcr and live in sulfidic environments, is unknown. We have determined the catalytic properties of FsrII from a member of ANME-2c. Since ANME remain to be isolated, we expressed ANME2c-FsrII in a closely related methanogen, Methanosarcina acetivorans. Purified recombinant FsrII contained siroheme, indicating that the methanogen, which lacks a native sulfite reductase, produced this coenzyme. Unexpectedly, FsrII could not reduce sulfite or thiosulfate with F420H2. Instead, it acted as an F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase (FNiR) with physiologically relevant Km values (nitrite, 5 μM; F420H2, 14 μM). From kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural analyses, we hypothesize that in FNiR, F420H2-derived electrons are delivered at the oxyanion reduction site at a redox potential that is suitable for reducing nitrite (E0′ [standard potential], +440 mV) but not sulfite (E0′, −116 mV). These findings and the known nitrite sensitivity of Mcr suggest that FNiR may protect nondenitrifying ANME from nitrite toxicity. Remarkably, by reorganizing the reductant processing system, Fsr transforms two analogous oxyanions in two distinct archaeal lineages with different physiologies and ecologies.

IMPORTANCE Coenzyme F420-dependent sulfite reductase (Fsr) protects methanogenic archaea inhabiting deep-sea hydrothermal vents from the inactivation of methyl coenzyme M reductase (Mcr), one of their essential energy production enzymes. Anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME) that oxidize methane and rely on Mcr, carry Fsr homologs that form a distinct clade. We show that a member of this clade from ANME-2c functions as F420-dependent nitrite reductase (FNiR) and lacks Fsr activity. This specialization arose from a distinct feature of the reductant processing system and not the substrate recognition element. We hypothesize FNiR may protect ANME Mcr from inactivation by nitrite. This is an example of functional specialization within a protein family that is induced by changes in electron transfer modules to fit an ecological need.

KEYWORDS: anaerobic methane oxidation, anaerobic methanotrophic archaea, methanogen, F420-dependent nitrite reductase, F420-dependent sulfite reductase, FsrI, FsrII, coenzyme F420, F420H2, deazaflavin, electron transfer, iron-sulfur cluster, methane

INTRODUCTION

Microbial degradation of complex biopolymers in the marine sediments annually generates 85 to 300 Tg of methane, a potent greenhouse gas (1). However, oceans contribute a minor fraction to atmospheric emissions, and this is largely due to a microbial process known as the anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) (1, 2). In early 2000s, this conversion was shown to be a syntrophic process, where methane oxidation performed by environmental anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME) is coupled to sulfate reduction by sulfate-reducing bacteria (2–4). ANME are polyphyletic, with several clades closely related to methanogenic archaea in the phylum Halobacteriota (5). Collectively, these anaerobes employ a reversed methanogenesis pathway for methane oxidation (2, 6). Over the last 2 decades, several mechanisms for the syntrophy in AOM have been put forward, and it remains an active research topic (2–4, 7–13). In one case, it was hypothesized that ANME-2 archaea are capable of directly reducing sulfate to oxidize methane (3), bringing new attention to the genomic data linked to sulfate metabolism in ANME, including the homologs of F420-dependent sulfite reductase (Fsr) (8, 14–18). Fsr was first observed in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, a representative of an ancient lineage of methanogens from deep-sea hydrothermal vents (19). Genetic and biochemical analyses support a role in sulfite detoxification by the M. jannaschii Fsr (MjFsr), converting this potent inhibitor of methyl coenzyme M reductase, an essential enzyme for the methanogens, to sulfide, an essential sulfur source for anabolism in this hyperthermophilic methanogen (19–21). All described hyperthermophilic methanogenic archaea from deep-sea hydrothermal vents carry the fsr gene, suggesting that the ability to transform sulfite into bioavailable sulfur is advantageous in this environment (19, 22). It is also present in several hyperthermophilic, thermophilic, and mesophilic methanogens from hot springs, sewage digesters, peatland, and hypersaline and marine sediments (14, 19, 22). However, the specific function of Fsr in these diverse archaea has not been confirmed.

While early studies on Fsr identified homologs of the protein in ANME (22, 23), observations made in the field studies and laboratory experiments and further bioinformatic analyses brought about an ANME-specific focus on this enzyme (14–16, 24). An environmental metaproteomic analysis of marine methane seep sediment showed that a homolog of Fsr in ANME-2 lineages is overexpressed in the environment (14–16, 24). On the other hand, in sediment microcosm experiments, the members of ANME-2c are seen as sensitive to sulfite (14), and SO42− utilization in ANME-2 is likely assimilatory in nature and not coupled to methane oxidation (15). These findings raised new possibilities for the function of Fsr in ANME, and a comparative primary structure analysis has brought further attention to this topic (14).

The enzyme Fsr is a two-domain protein, where the N-terminal F420H2 dehydrogenase unit (Fsr-N) retrieves reducing equivalents from F420H2 and the C-terminal dissimilatory sulfite reductase (Dsr) unit (Fsr-C) utilizes them to reduce sulfite to sulfide (19, 22). A phylogenetic analysis showed that MjFsr-C and ANME-Fsr-C are distinct in their primary structures, and accordingly, the respective homologs have been named FsrI and FsrII (14). With one exception, all FsrI homologs occur in certain methanogens that belong to phylum Methanobacteriota, and the organisms carrying FsrII homologs belong to the phylum Halobacteriota (6, 14); Methanohalobium evestigatum, a moderate thermophile from Halobacteriota that was isolated from a salt lagoon, carries both FsrI and FsrII (14). Taken together, these studies suggest that an FsrII likely contributes to the ecophysiology of ANME in a manner that is different from the role of FsrI in M. jannaschii, and hence, FsrI and FsrII could have distinct catalytic properties. Accordingly, we have characterized the structural and catalytic properties of a homogenous preparation of an FsrII of the ANME-2c lineage, ANME2c-FsrII-6D, and found that it acts as an F420-dependent nitrite reductase (FNiR) and is incapable of reducing sulfite with F420H2. We describe the thermodynamic and structural basis for this distinction and discuss the possible ecophysiological relevance of the enzyme.

RESULTS

Heterologous expression and purification of recombinant ANME2c-FsrII-6D.

A recombinant Methanosarcina acetivorans strain carrying pDS701, a replicable expression vector for ANME2c-FsrII, was constructed for the study. An extract of cells of this strain that were induced with tetracycline was able to catalyze sulfite-dependent oxidation of reduced methyl viologen. This activity was absent in native M. acetivorans extracts, which lack Fsr (14, 19, 22). Thus, it was concluded that ANME2c-FsrII-6D was expressed with activity in M. acetivorans(pDS701) under tetracycline induction. Similar to MjFsrI (19), the ANME2c-FsrII-6D activity in the cell extracts was highly oxygen sensitive. Based on this initial finding, all enzyme purification steps were performed under strictly anaerobic conditions.

The enzyme was purified to apparent homogeneity via ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by sequential phenyl-Sepharose, QAE-Sephadex, and F420-Sepharose chromatography steps (19). It did not bind to the QAE-Sephadex at the operating pH of 7, and the same result was obtained with DEAE-Sephadex. However, the anion exchanger bound and removed other negatively charged non-FsrII proteins and molecules that could have affected the performance of the F420 affinity-based purification step that followed. This negative purification step was useful for our purpose. The chromatography results also suggested that at pH 7, ANME2c-FsrII-6D either carried a net positive charge or was neutral. An opposite scenario exists for MjFsrI, which binds to QAE-Sephadex at pH 7 (19) and therefore carries a negative charge under the operating conditions. A typical purification experiment yielded 0.72 ± 0.30 mg ANME2c-FsrII-6D protein per gram (wet weight) of cell pellet of the recombinant M. acetivorans strain.

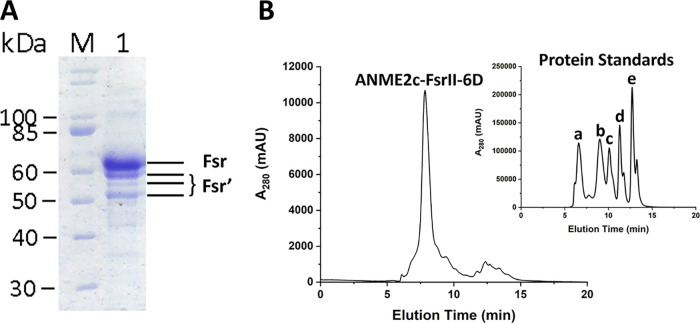

In SDS-PAGE, the preparation obtained from the F420-Sepharose chromatography step exhibited four bands (Fig. 1A) at ~52, ~55, ~58, and ~70 kDa, of which the last one matched the theoretical subunit size of ANME2c-FsrII-6D (69.23 kDa). Mass-spectrometric analyses confirmed that each of the bands corresponded to FsrII, indicating that the ~70 kDa band represented the intact subunit, with the smaller Fsr fragments representing degradation products likely produced during the sample preparation. A similar observation has been reported for MjFsrI (19). Confirming that the preparation of ANME2c-FsrII-6D obtained from the F420 affinity chromatography step was homogeneous, we continued with structural and spectroscopic characterization of the recombinant Fsr protein.

FIG 1.

Analysis for subunit size and quaternary structure of ANME2c-FsrII-6D. (A) SDS-PAGE gel with F420 affinity-purified recombinant ANME2c-FsrII-6D. Lanes: M, protein ladder; 1, ANME2c-FsrII-6D preparation. Fsr, ~70 kDa, intact FsrII; Fsr′, ~52, ~55, and ~58 kDa degradation products of FsrII. (B) Size exclusion-chromatographic analysis of ANME2c-FsrII-6D. The largest peak corresponded to Fsr (20 μg protein). (Inset) Elution of the following calibration standards (catalog number 151-1901; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA): a, thyroglobulin, 670,000 Da; b, gamma globulin, 158,000 Da; c, ovalbumin, 44,000 Da; d, myoglobin, 17,000 Da; e, vitamin B12, 1,350 Da. Figure S1 shows the calibration plot.

Structural and spectroscopic characteristics of ANME2c-FsrII-6D.

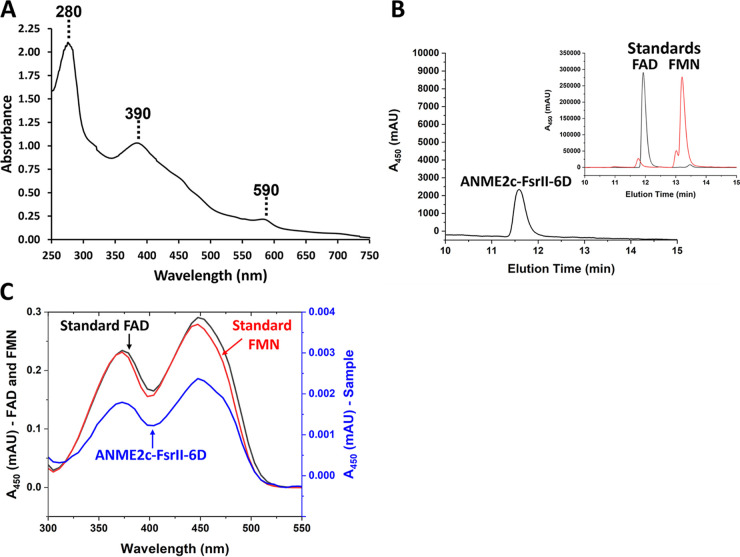

From the size exclusion chromatography data, the apparent native molecular mass of ANME2c-FsrII-6D was determined to be 289.44 kDa (Fig. 1B; also, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This value and the subunit size as determined via SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A) indicated that ANME2c-FsrII-6D was a tetramer of ~70 kDa subunits. The UV-visible spectrum of ANME2c-FsrII-6D exhibited three peaks at 280, 390, and 590 nm (Fig. 2A), which are typical of siroheme in the low-spin ferric state (19, 25). A reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of a methanol-methylene chloride extract of the protein showed that purified recombinant ANME2c-FsrII-6D contained FAD (Fig. 2B and C); the elution time and the UV-visible spectrum of the eluting cofactor were identical to those of FAD. An estimation based on HPLC analysis showed that 63.2 μg or 0.91 nmol of ANME2c-FsrII-6D contained 1.08 nmol FAD, suggesting that a subunit of ANME2c-FsrII-6D carried one bound molecule of this flavin.

FIG 2.

Analysis for prosthetic groups of ANME2c-FsrII-6D. (A) UV-visible spectrum of FsrII. A 300-μL anaerobic solution of 84 μg of homogeneous ANME2c-FsrII-6D in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 250 mM NaCl was analyzed in a quartz cuvette with a 1-cm light path sealed with a no. 00000 rubber stopper (EPDM rubber stopper, WidgetCo, Houston, TX). (B) Reverse-phase HPLC analysis of a methanol-methylene chloride extract of ANME2c-FsrII-6D. (Main plot) Analysis of a 100-μL methanol-methylene chloride extract of 63.2 μg homogeneous protein. The peak corresponds to FAD. (Inset) Analysis of a 10-μL solution of 1 mM FAD and FMN in distilled water. (C) UV-visible spectrum of flavin cofactor extracted from ANME2c-FsrII-6D and resolved on a reverse-phase column as described for panel B.

Bathophenanthroline and methylene blue assays revealed that ANME2c-FsrII-6D contained 15.36 ± 1.97 mol of iron and 15.02 ± 2.07 mol of acid-labile sulfur per subunit. These results suggested that each subunit of ANME2c-FsrII-6D assembled four [Fe4-S4] clusters.

Catalytic properties of ANME2c-FsrII-6D. (i) Nitrite and hydroxylamine reduction.

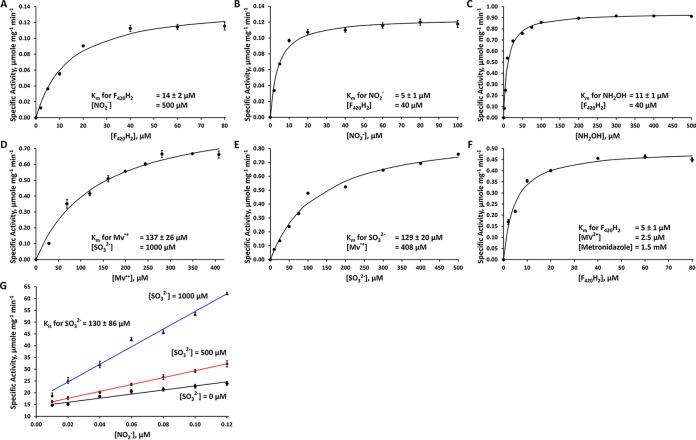

The lack of sulfite reduction activity with F420H2, the presumed native electron donor for Fsr, was unexpected, and further experiments were conducted to determine whether ANME2c-FsrII-6D was capable of reducing other substrates with F420H2. Notably, in assays with both nitrite and hydroxylamine, a substantial F420H2 oxidation activity was observed; hydroxylamine is a common intermediate of enzymatic reduction of nitrite (26–31). Furthermore, the addition of 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) stimulated the nitrite and hydroxylamine reduction activity by 1.5- and 5-fold, respectively. Thus, further assays of these activities occurred in the presence of DTT. At a fixed concentration of 500 μM for nitrite and a concentration range of 1 to 80 μM for F420H2, the apparent Km for F420H2 was determined to be 14 ± 2 μM and the maximum velocity (Vmax) value was 0.2 ± 0.01 μmol of F420H2 oxidized or 0.3 ± 0.02 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3A). Similarly, with 40 μM F420H2 and 2 to 100 μM nitrite, the apparent Km for nitrite was found to be 5 ± 1 μM and the Vmax was 0.2 ± 0.01 μmol of F420H2 oxidized or 0.3 ± 0.01 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3B). The apparent Km for hydroxylamine was also determined. Assays at 40 μM for F420H2 and 2 to 500 μM hydroxylamine, the apparent Km for hydroxylamine was found to be 11 ± 1 μM and the Vmax was 1 ± 0.02 μmol of F420H2 oxidized or 2 ± 0.04 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3C). These kinetic parameter values are also shown in Table 1. Considering that the reduction of nitrite to ammonium (NO2− to NH4+) is a 6-electron process and that for hydroxylamine to ammonium (NH2OH to NH4+) is a 2-electron process, ANME2c-FsrII-6D reduced hydroxylamine 21 times faster than nitrite. In a reaction mixture with 0.08 μmol of F420H2 and 0.40 μmol of nitrite, ANME2c-FsrII-6D produced 0.02 ± 0.001 μmol of F420 and 0.006 ± 0.005 μmol of ammonia after 30 min of reaction; these values represent averages from three independent assays. Considering that 3 mol of F420H2 (6 electrons) would be needed to reduce 1 mol of nitrite to ammonia, the above values represent 90% recovery of reducing equivalents from F420H2 into ammonia, indicating that it was the sole product. ANME2c-FsrII-6D was not able to utilize NADH or NADPH as electron donors with nitrite or hydroxylamine as an oxidant. The second partial reaction of the nitrite reductase activity could not be assayed because nitrite chemically oxidized the electron source, reduced methyl viologen (MV·+); the first partial reaction did not involve nitrite, and the respective activity was assayed as described in the following section. The kcat values for the nitrite reductase activity with respect to F420H2 and nitrite were 19 and 18 min−1, respectively, and for the sulfite reductase activity it was 64 min−1 with respect to both HSO3- and MV·+ (Table 1). A turnover value of 130 min−1 was recorded for the hydroxylamine reductase activity with respect to NH2OH (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Kinetic analysis of ANME2c-FsrII-6D reactions. (A to F) Specific activities of the enzyme at various concentrations of F420H2 (A), nitrite (B), hydroxylamine (C), reduced methyl viologen (D), sulfite (E), and F420H2-oxidized methyl viologen-metronidazole (F). (G) Double reciprocal plots for the data on the inhibition of nitrite reductase activity by sulfite. Each data point is an average of values from three assays. In panels A to F, each solid curve represents the best fit of the data to the Henry-Michaelis-Menten hyperbola function, v = Vmax [S]/(Km + [S]). Specific activity is defined as micromoles of F420H2 or reduced methyl viologen oxidized per minute per milligram of enzyme. A value for the amounts of sulfite or nitrite consumed was taken as one-third or one-sixth of that for F420H2 or reduced methyl viologen, respectively, assuming that sulfide or ammonia was the sole product. For panel G, the data were analyzed by fitting to the model v = Vmax [S]/{Km (1+[I]/Ki) + [S]}.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of ANME2c-FsrII-6Da

| Substrate concentrations | Km (μM) for the varied substrate | Kcat (min−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1 min−1) (with respect to the varied substrate) | Reaction (electron donor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2−, 500 μM; F420H2, varied (1–80 μM) | 14 ± 2 (F420H2) | 19 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.3 (F420H2) | NO2− reduction (F420H2) |

| F420H2, 40 μM; NO2−, varied (2–100 μM) | 5 ± 1 (NO2−) | 18 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 (NO2−) | NO2− reduction (F420H2) |

| F420H2, 40 μM; NH2OH, varied (2–500 μM) | 11 ± 1 (NH2OH) | 130 ± 3 | 12 ± 2 (NH2OH) | NH2OH reduction (F420H2) |

| HSO3−, 1,000 μM; MV·+, varied (29–408 μM) | 137 ± 26 (MV·+) | 64 ± 5 | 0.5 ± 0.1 (MV·+) | HSO3− reduction (MV·+)b |

| MV·+, 408 μM; HSO3−, varied (10–500 μM) | 129 ± 20 (HSO3−) | 64 ± 4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 (HSO3−) | HSO3− reduction (MV·+)b |

Km, Michaelis-Menten constant; kcat, turnover number expressed in terms of number of electrons transferred per enzyme subunit per min; kcat/Km, catalytic efficiency with respect to the varied substrate.

Nitrite reduction activity could not be assayed with MV·+ as the electron donor because NO2− oxidizes MV·+ chemically.

(ii) Sulfite reduction.

We tested the ability of ANME2c-FsrII-6D to reduce relevant sulfur oxyanions with the reductants: F420H2 (the predicted native electron donor), NADH, and NADPH. ANME2c-FsrII-6D did not oxidize F420H2 with sulfite or thiosulfate as electron acceptors and similar results were obtained in assays with NADH and NADPH as reductants. These conclusions were based on activity assays both with and without 0.5 mM DTT and more than 10 independently generated purified preparations.

Upon finding a lack of sulfite reduction with F420H2 by the enzyme, we examined if ANME2c-FsrII-6D could catalyze the following two partial reactions that have been observed with MjFsrI (19): F420H2 oxidation, transfer of electrons from F420H2 to the protein bound flavin coenzyme as catalyzed by Fsr-N; sulfite reduction, utilization of electrons transferred from reduced flavin via iron-sulfur clusters and siroheme prosthetic group of Fsr-C (19, 22). While the first is assayed with methyl viologen (MV2+) as the direct electron acceptor, the second partial reaction is observed with reduced methyl viologen (MV·+) as the reductant (19). The ANME2c enzyme catalyzed both partial reactions. The second reaction did not occur with thiosulfate as the electron acceptor.

We calculated the Km value for the substrates and maximum velocity (Vmax) for sulfite reduction from the second partial reaction. In assays with a fixed concentration of sulfite (1 mM) and a concentration range of 29 to 408 μM for MV·+, the apparent Km for MV·+ was determined to be 137 ± 26 μM and the value of maximum velocity (Vmax) was 1 ± 0.1 μmol of MV·+ oxidized or 1 ± 0.1 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3D). Similarly, at a fixed concentration of 408 μM for MV·+ and a sulfite concentration range of 10 to 500 μM, the apparent Km for sulfite was found to be 129 ± 20 μM and the Vmax value was 1 ± 0.1 μmol of MV·+ oxidized or the same amounts of electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3E). If DTT was omitted from the assay, the apparent Km for sulfite dropped to 28 ± 5 μM and the Vmax value dropped to 0.3 ± 0.01 μmol of MV·+ oxidized, or 0.3 ± 0.01 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme. In a reaction mixture with 0.8 μmol of MV·+ and 0.8 μmol of sulfite, ANME2c-FsrII-6D produced 0.02 ± 0.01 μmol of sulfide after 30 min of reaction; these values represented averages from three independent assays. This result represents a utilization of 13% of the reductant (MV·+) supplied in the assay toward sulfide production from sulfite, which is a 6-electron reduction process. The enzyme was able to oxidize F420H2 with a mixture of methyl viologen (MV2+) and metronidazole, where the former served as the direct artificial electron acceptor for the enzyme and was reduced to MV·+, and metronidazole regenerated MV2+ from MV·+. From assays with 2.5 μM MV2+, 1.5 mM metronidazole, and a concentration range of 2 to 80 μM for F420H2, the apparent Km for F420H2 was determined to be 5 ± 1 μM and Vmax was 0.5 ± 0.02 μmol of F420H2 oxidized or 1 ± 0.04 μmol electrons transferred per min per mg enzyme (Fig. 3F). A summary of the enzyme’s kinetic parameters is shown in Table 1.

(iii) Inhibition of nitrite reductase activity by sulfite.

The pattern seen in the double-reciprocal or Lineweaver-Burk plots of the data collected at a fixed concentration of 40 μM for F420H2 and with nitrite at 8.3 to 100 μM and sulfite at three different concentrations, 0, 500, and 1000 μM, suggested that sulfite was a competitive inhibitor of ANME2c-FsrII-6D for the enzyme’s nitrite reduction activity (Fig. 3G). In this assay, sulfite was not reduced, as ANME2c-FsrII-6D cannot reduce this oxyanion with F420H2, and truly acted as an inhibitor. A fitting of the data to the competitive inhibition model yielded a value of 130 ± 86 μM for the apparent inhibition constant (Ki) for sulfite; the standard error for the fitting suggested that the inhibition did not follow a standard model, and the mechanism underlying this departure is currently unknown.

Structural features of ANME2c-FsrII-6D and other FsrIIs and FsrIs—analysis of primary structure and computational models for three-dimensional structures.

Since the N- and C-terminal halves of an Fsr (Fsr-N and Fsr-C) represent two distinct domains performing two parts of the overall reactions, F420H2 oxidation and sulfite or nitrite reduction, respectively, we analyzed the features for ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C separately. From a comparison with MjFsrI, where the residues 1 to 311 and 325 to 620 represent the N- and C-terminal domains (19, 22), the ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C units were assigned to the 1 to 341 and 356 to 642 segments of ANME2c-FsrII.

N-terminal domain—iron-sulfur clusters.

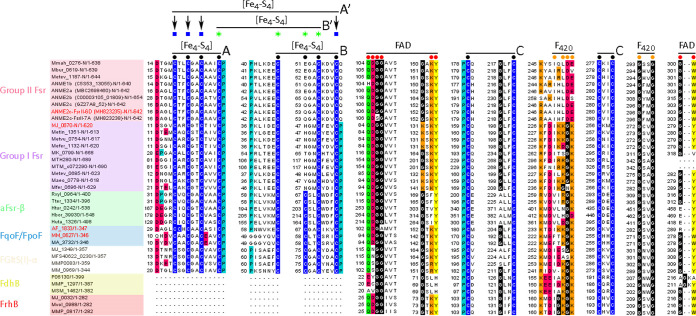

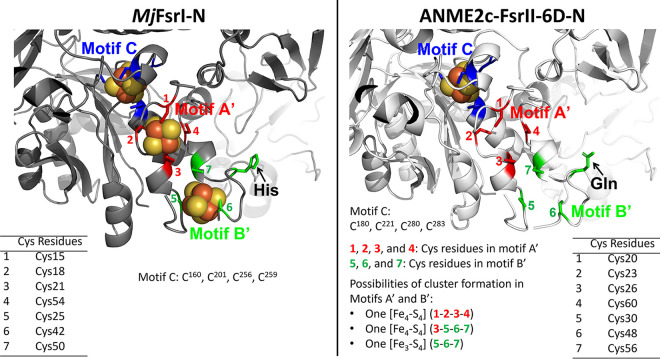

ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N and MjFsrI-N are homologs of the F420H2 dehydrogenase subunit F of F420H2:quinone oxidoreductase (FqoF) complex of A. fulgidus (32) and F420H2:phenazine oxidoreductase (FpoF) complex of Methanosarcina mazei (Fig. 4) (19, 22, 33). Both A. fulgidus FqoF and M. mazei FpoF carry two CX2CX2CX3CP or ferredoxin-type [Fe4-S4] cluster motifs (Fig. 4, motifs A and B). While the motif A features are conserved in all FsrI-Ns and FsrII-Ns, motif B of FsrI and FsrII lacked the second position Cys, and this position was occupied by a His in MjFsrI-N and Gln in ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N (Fig. 4). In addition, in FsrII, the terminal Pro residue was absent (Fig. 4). We also found that FsrI, FsrII, FpoF, and FqoF carry four more conserved cysteine residues, and we called this set motif C (Fig. 4). Since a solved three-dimensional structure of either an FsrI or FsrII is not available, to further gauge the potentials of iron-sulfur cluster assembly by cysteine residues of motifs A, B, and C in ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N and MjFsrI-N, we developed in silico models for these proteins using AlphaFold2 (34, 35).

FIG 4.

Multiple primary sequence alignment for ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N homologs. Conserved amino acid residues are represented as follows: blue, cysteine; cyan, proline; black, glycine; red, negatively charged (D or E); green, polar uncharged (S, T, N, or Q); orange, positively charged (H, R, or K); yellow, aromatic (F, Y, or W). Black bullets with overlines and A and B notations show [Fe4-S4] cluster assembly motifs; black circles with overlines and C notation represent conserved cysteine residues, red circles with overlines show the flavin binding motif (89, 90), and orange circles with overlines show the F420 binding motif (89); blue squares and green stars with overlines and A′ and B′ notations, respectively, show [Fe4-S4] cluster assembly motifs identified in the AlphaFold2 models. Fsr, F420-dependent sulfite reductases (14, 19, 22); aFsr-β, F420H2 dehydrogenase subunit of a putative F420H2-dependent assimilatory type siroheme sulfite reductase (22); FqoF/FpoF, F420H2 dehydrogenase subunit of a membrane-bound proton pumping F420H2 dehydrogenase complex (32, 33); FGltS(I)-α, F420H2 dehydrogenase subunit of a putative F420H2-dependent glutamate synthase (22, 91); FdhB, formate dehydrogenase subunit B (92); FrhB: F420-reducing [NiFe]-dehydrogenase subunit B (77). Open reading frame (ORF) numbers of the proteins, except those from ANME, are presented in the NCBI format (abbreviated organism name_respective ORF number). For an ANME protein, the NCBI ORF number appears within parentheses following the abbreviated organism name. “-N” indicates that only the N-terminal part of the polypeptide is shown. Ranges following slashes are amino acid residues for the complete protein. The names of proteins that are of particular interest in the study are shown in red. ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N, MH823235; MjFsrI-N, MJ_0870; FpoF of Archaeoglobus fulgidus, AF_1833; FqoF of Methanosarcina mazei, MM_0627. Abbreviations of organism names: Mmah, Methanohalophilus mahii DSM 5219; Mbur, Methanococcoides burtonii DSM 6242; Metev, Methanohalobium evestigatum Z-7303; MJ, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii DSM 2661; Metin, Methanocaldococcus infernus ME; Metvu, Methanocaldococcus vulcanius M7; Mefer, Methanocaldococcus fervens AG86; MK, Methanopyrus kandleri AV19; MTH, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus ΔH; MTM, Methanothermobacter marburgensis strain Marburg; Maeo, Methanococcus aeolicus Nankai-3; Mfer, Methanothermus fervidus DSM 2088; Rxyl, Rubrobacter xylanophilus DSM 9941; Tter, Thermobaculum terrenum ATCC BAA-798; Htur, Haloterrigena turkmenica DSM 5511; Hbor, Halogeometricum borinquense DSM 11551; Huta, Halorhabdus utahensis DSM 12940; AF, Archaeoglobus fulgidus DSM 4304; MM, Methanosarcina mazei Gö1; MA, Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A; MFS40622, Methanocaldococcus sp. FS406-22; MMP, Methanococcus maripaludis S2; P06130, accession number for Methanobacterium formicicum FdhB; MSM, Methanobrevibacter smithii ATCC 35061; Mvol, Methanococcus voltae A3; ANME, anaerobic methanotrophic archaea.

The in silico models presented clear possibilities for the formation of iron-sulfur clusters by motifs A and B, as well as a previously unrecognized motif C, in MjFsrI-N, FpoF, and FqoF (Fig. 4 and 5 and Fig. S2). The residues involved in the structures of motif A and B were also a bit different from those identified in sequence alignment, and we called these redefined motifs A′ and B′ (Fig. 4 and 5 and Fig. S2). The AlphaFold2 model of ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N suggested that motif C could form an [Fe4-S4] cluster. However, the following structural elements bring additional potentials for cluster formation (Fig. 5): motif A′, [Fe4-S4] cluster; a combination of Cys residues 3, 5, 6, and 7, [Fe4-S4] cluster; motif B′, [Fe3-S4] cluster. Since the iron and acid labile sulfur content data predict that ANME2c-FsrII-6D carries four [Fe4-S4] clusters and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C is predicted to hold 2 such units, from the above-mentioned modeling results we hypothesize that ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N assembles two [Fe4-S4] clusters, one of which would be in motif C and another via one of the three additional possibilities presented above.

FIG 5.

Iron-sulfur cluster binding residues of MjFsrI-N and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N based on AlphaFold2 model prediction. Modeled structures of MjFsrI-N and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N with docked [Fe4-S4] clusters from M. marburgensis F420-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenase (Frh; PDB ID 3ZFS) (89). Cysteine residues of motifs A′, B′, and C are shown as described for Fig. 4.

C-terminal domain.

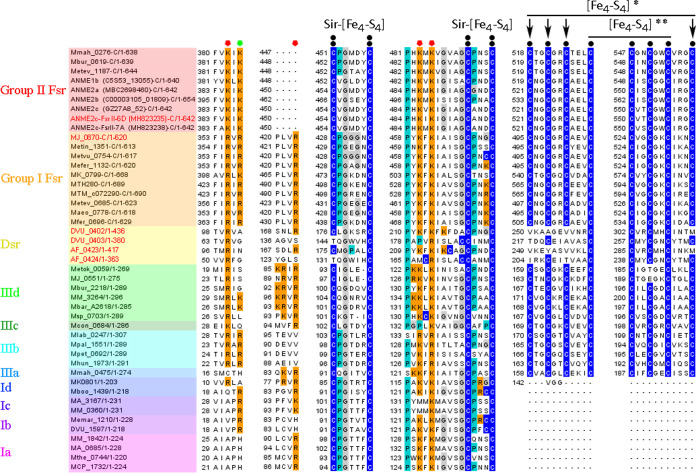

The C-terminal half of ANME2c-FsrII-6D (ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C) carried sequence features that are typical of a siroheme-[Fe4-S4] cluster and two additional [Fe4-S4] clusters of MjFsrI-C and DsrA, but, as elaborated below, it differed from the latter two in terms of sulfite binding residues (Fig. 6 and 7).

FIG 6.

Multiple-sequence alignment of ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C homologs. Amino acid residues are represented as follows: blue, cysteine; cyan, proline; gray, glycine; orange, positively charged (H, R, or K). Black circles represent conserved cysteine residues, double black bullets represent siroheme-[Fe4-S4] cluster binding residues, red polygons show sulfite binding residues, the green polygon shows conserved positively charged residues [RK] in group I and group II Fsrs, black bullets with overlines show [Fe4-S4] cluster assembly motifs, and single and double asterisks show peripheral and additional [Fe4-S4] centers, respectively (22). ORF numbers of the proteins are presented as described in the legend to Fig. 4. “-C” indicates that only the C-terminal part of the polypeptide is shown. Range following slashes are amino acid residues for the complete protein. Dsr, dissimilatory sulfite reductase; Ia-d, group I dissimilatory sulfite reductase like protein (Dsr-LP) subgroups a to d; IIIa-d, group III Dsr-LP subgroups a to d. The names of proteins that are of particular interest in the study are shown in red. ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C, MH823235; MjFsrI-C, MJ_0870; Dv-DsrA/B, Dsr subunits A and B of Desulfovibrio vulgaris strain Hildenborough, DVU_0402 and DVU_0403; Af-DsrA/B, Dsr subunits A and B of Archaeoglobus fulgidus DSM 4304, AF_0423 and AF_0424. Metok, Methanothermococcus okinawensis IH1; Mbar, Methanosarcina barkeri strain Fusaro; Msp, Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091; Mcon, Methanosaeta concilii GP-6; Mlab, Methanocorpusculum labreanum Z; Mpal, Methanosphaerula palustris E1-9c; Mpet, Methanoplanus petrolearius DSM 11571; Mhun, Methanospirillum hungatei JF-1; Mboo, Candidatus Methanoregula boonei 6A8; Memar, Methanoculleus marisnigri JR1; Mthe, Methanosaeta thermophila PT; MCP, Methanocella paludicola SANAE. The legend to Fig. 4 presents abbreviations of other organisms’ names.

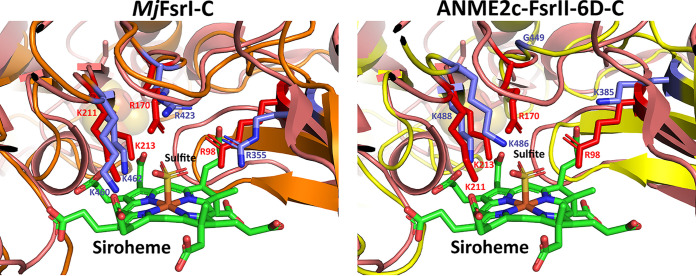

FIG 7.

Sulfite binding pocket of MjFsrI-C and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C. Structural alignments of A. fulgidus DsrA with MjFsrI-C and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C, respectively. The protein backbones of A. fulgidus DsrA, MjFsrI-C, and ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C are in deep salmon, orange, and yellow, respectively. Carbon atoms of residues involved in the formation of sulfite binding site of A. fulgidus DsrA and MjFsrI-C/ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C are in red and purple, respectively. The residue numbers correspond to A. fulgidus DsrA (red) and MjFsrI-C/ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C (purple). For siroheme and sulfite the following color code is used: green, carbon; blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; yellow, sulfur; orange, iron.

(i) Peripheral and additional [Fe4-S4] clusters.

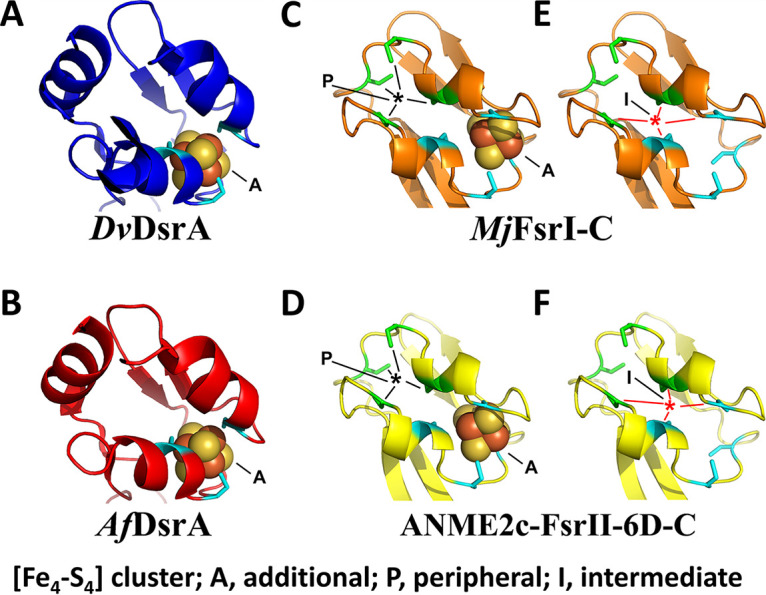

In the current study, an AlphaFold2 modeling and alignment with X-ray crystallographic structures of A. fulgidus and D. vulgaris DsrA subunits (PDB IDs 3MM5 and 2V4J) suggested that a set of Cys residues in a configuration that is different from what was previously proposed (19, 22) contribute to peripheral and additional [Fe4-S4] clusters in all FsrI-Cs and FsrII-Cs (Fig. 6 and 8). These newly recognized motifs were CX2CX2CXnC (peripheral) and CXnCX2CX2C (additional) (Fig. 6). Of these, the peripheral [Fe4-S4] cluster is not present in A. fulgidus and D. vulgaris DsrA or DsrB subunits (Fig. 6). In A. fulgidus and D. vulgaris DsrAs, which are the catalytic subunits, the space required for the binding of the peripheral [Fe4-S4] cluster is present, but it lacks cysteine residues (Fig. 8A and B). The relative locations of the Cys residues for peripheral and additional clusters in FsrI-C and FsrII-C have brought up three possibilities for the [Fe4-S4] cluster formation in these units (Fig. 8): (i) assembly two of [Fe4-S4] clusters, peripheral and additional (Fig. 8C and D); (ii) only the additional cluster as seen in DsrA (Fig. 8C and D); (iii) only one [Fe4-S4] cluster positioned in the middle of the peripheral and additional site and formed by utilizing two Cys residues from each site (Fig. 8E and F). The [Fe4-S4] clusters representing these possibilities will experience different protein environments, and therefore, will exhibit different redox properties and midpoint redox potential values (E0′). In summary, both FsrI-C and FsrII-C are predicted to hold two to three [Fe4-S4] clusters, one of which may be ligated to the siroheme, whereas DsrAs in A. fulgidus and D. vulgaris assemble only one [Fe4-S4] cluster in addition to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] unit.

FIG 8.

[Fe4-S4] cluster binding pockets of Fsr-C homologs. (A) Desulfovibrio vulgaris DsrA (DvDsrA; PDB ID 2V4J). (B) Archaeoglobus fulgidus DsrA (AfDsrA; PDB ID 3MM5). (C and E) MjFsrI-C. (D and F) ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C. Carbon atoms of conserved cysteine residues involved in the binding of a [Fe4-S4] cluster are colored as follows: DsrA (as in panels A and B), cyan; additional and peripheral [Fe4-S4] clusters of MjFsrI-C and FsrII-C (as in panels C to F), cyan and green, respectively.

(ii) Sulfite and nitrite binding sites.

The sulfite binding site of a DsrA subunit of a dissimilatory sulfite reductase is comprised of four positively charged residues (PDB IDs 3MM5 and 2V4J) (36, 37). In A. fulgidus DsrA, these residues are R98, R170, K211, and K213 (Fig. 6) and the same residues also coordinate the nitrogen and oxygen atoms of nitrite (27). An analysis of the respective primary structures suggested a similar situation exists in FsrI-Cs, while some distinctions were observed for FsrII-Cs (Fig. 6 and 7). Specifically, FsrII-C lacked the second of the four sulfite binding residues (Fig. 6) and structural modeling suggested that in ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C this Arg residue was substituted with a Gly (Fig. 7) (14). All Arg residues of the sulfite binding site of ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C were also replaced with Lys residues (Fig. 6 and 7). These replacements reduce the side chain length, and glycine does not have a charged side chain and is smaller than Arg. Thus, the above-mentioned changes created a larger and less positively charged pocket at the sulfite binding site in ANME2c-FsrII-6D-C than that in MjFsrI. These features likely provide an enhanced structural flexibility in the positioning of the substrate and perhaps providing the enzyme an ability to bind other substrates that are larger than sulfite (14) (Fig. 7). However, similar to MjFsrI, ANME2c-FsrII-6D was unable to reduce thiosulfate which is larger than sulfite. It remains to be determined whether ANME2c-FsrII-6D reduces a larger substrate with a sulfonate group. The above-mentioned structural departures were not responsible for a lack of sulfite reduction by the ANME2c-FsrII-6D with F420H2 because when reduced methyl viologen (MV·+) was used as an electron donor, the enzyme was able to reduce this oxyanion (Fig. 3D and E).

Iron-sulfur cluster contents of ANME2c-FsrII-6D and MjFsrI.

For the combined N-terminal and C-terminal domains the in silico model yielded the following possibilities in terms of the nature and number of the iron-sulfur cluster: MjFsrI, 5 or 6 [Fe4-S4] clusters; ANME2c-FsrII-6D, 4 or 5 [Fe4-S4] clusters with or without an [Fe3-S4] cluster. Our chemical assays suggested that ANME2c-FsrII-6D carries 15 Fe and 15 acid-labile sulfur units which closely correspond to four [Fe4-S4] clusters. The difference between the iron-sulfur cluster contents of MjFsrI and ANME2c-FsrII-6D likely would pertain to the N-terminal domain or specifically the motif B of this unit.

DISCUSSION

This study began with the hypothesis that the catalytic features of FsrII and its ecophysiological roles are distinct from those of FsrI and that this specialization likely has a substantial effect on AOM (14), a globally important geochemical process (1). The significance of these possibilities called for an examination of the catalytic properties of the FsrII. Accordingly, we generated a recombinant form of the FsrII from ANME-2c archaea in Methanosarcina acetivorans, and purified the enzyme, and characterized its biochemical properties. This is the first case where a homogenous and active form of an ANME enzyme with elaborate metallocenters was produced using a methanogen as the expression host, purified, and biochemically characterized. An ANME methyl-coenzyme M reductase, also a metalloenzyme, was previously expressed in M. acetivorans; however, the recombinant enzyme has yet to be purified to homogeneity (38). We discuss below our finding that the ANME-2c FsrII is an F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase, the structural basis for this specialization, and its possible ecophysiological relevance.

Generation of ANME-FsrII in a recombinant and homogeneous form with predicted prosthetic groups and enzymatic activity.

The methanotrophic ANME-2c archaea have yet to be isolated in pure culture, and the generation of a significant amount of biomass for ANME-2c consortia, with a doubling time of several weeks, is challenging (39, 40). Therefore, the use of a recombinant system for expressing and characterizing ANME proteins offers a method for enhancing our understanding of ANME physiology and protein function in the absence of pure cultures of these archaea. Prior work has shown that a careful selection of a phylogenetically related genetically tractable host matters in both successful heterologous expression of an Fsr and achieving activity in the recombinant protein (20). For example, while E. coli is a commonly used host for heterologous expression of proteins, it is unsuitable for the expression of MjFsrI in a soluble and active form. On the other hand, in Methanococcus maripaludis, a close relative of M. jannaschii (41), MjFsrI could be overexpressed with activity (20). We initially attempted to express ANME2c-FsrII-6D using M. maripaludis as the host; however, a mass-spectrometric analysis of cell extracts using a previously described method (42) showed that the produced protein was barely above detection in the recombinant strain (data not shown). Additionally, in assays with either F420H2 or reduced methyl viologen (MV·+) as the electron donor, the cell extracts did not exhibit a sulfite reductase activity (data not shown). All follow-up work with ANME2c-FsrII-6D was subsequently conducted in Methanosarcina acetivorans as the expression host, which presented several advantages over M. maripaludis for this study. Not only is M. acetivorans a genetically amenable methanogen, but this archaeon is also phylogenetically closely related to the ANME-2c, both belonging to the order Methanosarcinales (2, 6, 43). This relatedness provided an enhanced possibility of proper folding for the heterologously expressed ANME2c-FsrII-6D. Another important consideration is that M. acetivorans increased the likelihood of assembling a suitable type of siroheme in the recombinant ANME-2c protein. The siroheme structures are known to carry organism-specific modifications, such as the amidation of one of the acetate chains in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Allochromatium vinosum (44, 45). M. acetivorans lacks Fsr but carries four homologs of dissimilatory sulfite reductase-like proteins (Dsr-LPs) (22), and these Dsr-LPs have the structural features for assembling siroheme-[Fe4-S4] clusters (22), and a representative of this protein (P590) carrying a siroheme unit has been isolated from a Methanosarcina species (46). As mentioned above, M. maripaludis, which lacks Fsr and possesses a Dsr-LP (20, 22), can generate active MjFsrI from a cloned gene (20). Consequently, the selection of M. acetivorans increased the probability of proper folding for the heterologously expressed ANME FsrII protein and the incorporation of a proper type of siroheme into it. Indeed, M. acetivorans carrying an expression vector that we constructed in this study, pDS701, produced recombinant ANME-FsrII with activity and a UV-visible spectrum that is characteristic of a siroheme protein (Fig. 2A and 3). This result also confirmed that M. acetivorans can produce siroheme.

ANME2c-FsrII-6D, F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase (FNiR) with an F420H2-nonutilizing sulfite reduction activity.

The FsrII of ANME-2c is a structural homolog of MjFsr-I which reduces sulfite to sulfide with F420H2 as a reductant (19), and it was unexpected to find that this FsrII could not reduce sulfite using F420H2 as the electron donor. Since nearly all characterized sulfite reductases also reduce nitrite (19, 26–29, 47) (Table S1) and MjFsrI exhibits this activity (E. F. Johnson, C. Heryakusuma, and B. Mukhopadhyay, unpublished data), we examined the potential for ANME2c-FsrII-6D to reduce nitrite. Assays with the ANME-2c FsrII confirmed active reduction of nitrite to ammonia with F420H2 as the reductant, with a Km value for nitrite (5 μM) that is comparable to that of bona fide nitrite reductases described from other organisms (Table S1). The Km value of ANME2c-FsrII-6D for the electron donor F420H2 was also comparable to that of other F420H2-utilizing enzymes, including MjFsrI and F420H2-dependent thioredoxin reductase (DFTR) from M. jannaschii, FpoF of Methanosarcina mazei, and FqoF of Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Table S1) (19, 32, 33, 48, 49). Therefore, the F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase activity of ANME2c-FsrII-6D appears to be physiologically relevant.

A comparison of the respective kinetic constant values (Table 1) revealed valuable mechanistic information for the nitrite, hydroxylamine, and sulfite reduction activities. The apparent Km value for sulfite was 26 times higher than that of nitrite, and this property was consistent with ANME2c-FsrII-6D being a nitrite reductase. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) values for nitrite and sulfite reduction could not be compared, as these two reactions had to be measured with different electron donors (Table 1), although individually, they provided key insights. The reduction of nitrite to ammonia by nitrite reductases generally proceeds through intermediate formation of hydroxylamine, and nitrite reductases frequently exhibit hydroxylamine reductase activity (26–31). Consistent with this, ANME2c-FsrII-6D exhibited an F420H2-dependent hydroxylamine reductase activity with a physiologically relevant Km value for NH2OH (Table 1 and Table S1). The catalytic efficiency of this activity was 3-fold higher than that for the overall nitrite reduction reaction, suggesting that this enzyme was capable of preventing the intracellular accumulation of hydroxylamine, which is toxic to many organisms (50). Based on our characterization of nitrite and hydroxylamine activity from ANME2c-FsrII-6D, it appears that the function of the FsrII clade in ANME-2 (14) is distinct from that of FsrI in the hyperthermophilic methanogen M. jannaschii, with the ANME-2c version of this enzyme serving as a nitrite, rather than sulfite reductase, utilizing F420H2 as a reductant. We propose naming this enzyme F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase (FNiR).

Basis for discrimination between nitrite and sulfite in ANME2c-FsrII-6D.

Our initial analyses examined the ability of the Fsr enzyme to recognize its predicted substrate, which was sulfite. The potential oxyanion binding site of ANME2c-FsrII-6D differed structurally from those of dissimilatory sulfite reductases or Dsrs to some extent (Fig. 7), and the apparent Km of the enzyme for sulfite (~130 μM) was 11-fold higher than that of MjFsrI (12 μM) (19), suggesting that sulfite may not be the preferred substrate for this enzyme. Also, sulfite is a poor competitive inhibitor of nitrite reduction by ANME2c-FsrII-6D, as the Ki for sulfite was about 26 times higher than the Km for nitrite (Fig. 3B and G). However, as discussed below, these factors did not underlie the observed lack of F420H2-dependent sulfite reductase in ANME2c-FsrII-6D. The conclusion for the other substrate, F420H2, was similar, as the enzyme exhibited both physical interaction with F420 and catalytic activity with F420H2, even though its putative F420-binding site deviated structurally from that of MjFsrI and Methanothermobacter marburgensis FrhB; ANME2c-FsrII-6D bound to the F420 affinity column and exhibited an apparent Km for F420H2 (~14 μM) that was comparable to that of MjFsrI (21 μM) (19) (Table S1). Thus, the absence of F420H2-dependent sulfite reductase activity in ANME2c-FsrII-6D was unlikely to be due to a lack of substrate recognition by the enzyme.

The overall thermodynamics of the redox reaction between F420H2 and the oxyanions was not a possible factor contributing to the unexpected activity profile for ANME2c-FsrII-6D, as the respective ΔG°′ values predict that the reduction of both sulfite and nitrite with F420H2 are thermodynamically feasible (equations 4 and 5). The enzyme reduced nitrite, hydroxylamine, and MV·+ but not sulfite with F420H2. However, with MV·+ as the electron donor, ANME2c-FsrII-6D exhibited a robust sulfite reductase activity with high kcat and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) (Table 1). These suggested that in ANME, the reducing equivalents derived from F420H2 were not suitable for reducing sulfite.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

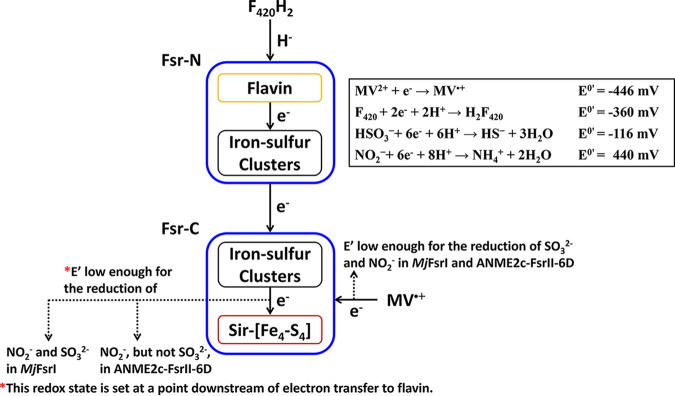

Since F420H2 is a hydride donor, the first step of electron transfer in an Fsr involves FAD, the only available hydride acceptor in the enzyme residing in the N-terminal domain (Fig. 9). Then, these electrons are transported through the iron-sulfur cluster systems of the N- and C-terminal domains to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] center at Fsr-C, where an oxyanion is reduced (19, 22). It is possible that one or more of these intermediate electron carriers, or even the one donating directly to the oxyanion reduction site, operate at a redox potential that is higher than that of the primary reductant, F420H2, thereby raising the redox potential of the retrieved electrons and making these less potent reductants. On the other hand, MV·+ likely transfers the electrons directly to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] center, thus bypassing the redox potential-altering steps. Accordingly, we hypothesize that although both F420H2 (E0′, −360 mV; equation 1) and MV·+ (E0′, −446 mV; equation 6) are thermodynamically competent in reducing sulfite (E0′, −116 mV; equation 3) and nitrite (E0′, +440 mV; equation 2), in ANME2c-FsrII-6D, the electrons derived from F420H2 are delivered to the siroheme-site at a redox potential value that is too high for the reduction of sulfite and yet suitable for nitrite reduction. In contrast, the electron transfer path in MjFsrI retains the reducing power of electrons derived from F420H2 to a level that is suitable for reducing sulfite, which would obviously favor nitrite reduction, an easier task. Since MV·+ can deliver electrons to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] center without such an alteration, it facilitates the reduction of both oxyanions for both MjFsrI and ANME2c-FsrII-6D. These results suggest that the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] centers of these two enzymes are equally competent in oxyanion reduction.

FIG 9.

Electron transfer in F420-dependent sulfite reductase (Fsr). In Fsr, protein-bound flavin is reduced by F420H2, and the electrons from reduced flavin are transferred via a set of iron-sulfur clusters to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] center, where an oxyanion is reduced. “Fsr-N” and “Fsr-C” indicate the N- and C-terminal halves of the Fsr, respectively.

We rationalize the above-stated hypothesis in terms of the cofactor contents and modeled structures of ANME2c-FsrII-6D and MjFsrI (Fig. 5 and 7). The siroheme and flavin contents of ANME2c-FsrII-6D were consistent with the expectations from the known properties of MjFsrI, FpoF, and FqoF (19, 32, 48), and a similar agreement was seen for the predicted numbers and natures of the C-terminal iron-sulfur clusters. However, ANME2c-FsrII-6D-N seemingly differed from MjFsrI-N in terms of the iron-sulfur cluster contents (Fig. 4 and 5), predicting distinct redox properties for these units. Also, a major change in the charge environment (from positive to negative) at the F420-binding site of ANME2c-FsrII-6D as predicted from a primary structure comparison could impact the electron transfer process. For these distinctions, the FsrII of ANME-2c (ANME2c-FsrII-6D) and FsrI of M. jannaschii (MjFsrI) could deliver F420H2-derived electrons to the siroheme-[Fe4-S4] center at different redox potentials.

Potential ecophysiological role of F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase in ANME.

The FsrII homologs occur in ANME and in selected psychrophilic and mesophilic methanogens from marine and hypersaline habitats, all belonging to the phylum Halobacteriota (6, 14, 19, 22). In contrast, as mentioned above, FsrI occurs exclusively in certain methanogens that belong to the phylum Methanobacteriota, with widespread presence in vent isolates, sporadic occurrence in thermophiles from hot springs, sewage digesters, and salt lagoons, and rare existence in mesophilic species (6, 14, 19, 22). The only exception to this distribution is Methanohalobium evestigatum, a moderate thermophile from Halobacteriota that was isolated from a salt lagoon, as it appears to carry both FsrI and FsrII (14). These distinctions in the distribution of FsrI and FsrII bring up the possibility that these clades may be optimized for the different environments and host physiology.

The initial presumption of FsrII having a role in sulfite detoxification was reasonable considering the highly reducing methane seep sediments, where elevated concentrations of sulfide and sulfur intermediates from sulfate-coupled AOM are common (16, 51, 52) and where transient oxygen exposure from bioturbation or methane ebullition could generate sulfite (19, 22). A similar situation has been suggested for the deep-sea hydrothermal vent habitat of M. jannaschii (19, 22). Sulfite is known to inactivate methyl coenzyme M reductase (Mcr) in methanogens, including members of the Methanosarcinales (53, 54), and MjFsrI protects M. jannaschii from this damage (19, 20). As Mcr is essential in methanogens and ANME, catalyzing both the last step of methanogenesis and the first step of ANME methanotrophy (12, 43), it is reasonable to assume that ANME archaea are also likely similarly sensitive to sulfite. Indeed, methane seep sediment microcosm experiments using ANME-2c as a dominant methane-oxidizing archaeon showed that sulfite inhibited rates of methane oxidation (14). It was therefore surprising that ANME2c-FsrII-6D appeared incapable of reducing sulfite with its natural electron carrier F420.

The demonstration of F420H2-dependent nitrite reductase activity by ANME2c-FsrII-6D introduces new ideas about the potential ecophysiological role of FsrII. Even at low micromolar concentrations, nitrite has been shown to oxidize the Ni(I) center of F430 in Mcr in methanogens, rendering this essential enzyme inactive (55, 56). This observation leads to a hypothesis that FNiR is a nitrite detoxification enzyme for ANME-2c, playing a physiological role that is analogous to that of MjFsrI with respect to sulfite (19, 20). M. jannaschii overexpresses FsrI in response to the presence of sulfite in the growth medium (19, 20), and deletion of the fsr gene results in sulfite sensitivity in this methanogen (21). An ANME FsrII has been found to be overexpressed under in situ conditions; however, corresponding information on porewater nitrogen concentrations and speciation was unfortunately not provided in these studies (14–16, 24).

Nitrite has been measured at low concentrations within methane seeps (57), and at least one study has reported the presence of anammox (anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing) bacteria in seep sediments, which carry out a redox process that couples ammonia oxidization with nitrite reduction (58), suggesting that exposure of ANME to nitrite in marine seeps is possible. The involvement of FsrII in nitrite detoxification is also interesting from the perspective of its phylogenetic distribution, as it appears to be common among marine ANME lineages but conspicuously lacking in ANME-2d (Candidatus ‘Methanoperedens nitroreducens’), a close methanotrophic relative found in terrestrial environments that is capable of directly oxidizing methane with nitrate reduction (59). In this ANME lineage, nitrite is predicted to be oxidized by a nitrite reductase (nrfAH) using menaquinol as the electron donor (60). These biochemical findings and structural predictions point to new research directions for increasing our understanding of the ecophysiological role of FsrII in ANME and its evolutionary history.

In summary, through heterologous expression in a related host methanogen, this study uncovered novel functionality of the group II Fsr in uncultured methanotrophic ANME-2 archaea. In ANME-2, Fsr group II appears to function solely as a coenzyme F420 utilizing nitrite reductase (FNiR), a role that is notably distinct from group I Fsr. In the hyperthermophilic methanogen M. jannaschii, FsrI catalyzes F420 coupled sulfite reduction and may also serve as a nitrite reductase. The FsrII enzyme is hypothesized to restrict the use of sulfite via fine-tuned control of the redox potential of the electrons delivered at its oxyanion reduction site. If the prediction about the physiological role of ANME-2c FsrII is proven to be correct, it would show that both FsrI and FsrII protect the same enzyme, methyl coenzyme M reductase (Mcr), from inactivation by two structurally similar oxyanions, sulfite and nitrite, respectively, in archaea from different habitats involved in methane production and consumption. Our study also showed that subtle changes in the predicted protein structure likely alters the properties of the redox centers, contributing to functional diversification in the Fsr protein family. These insights, along with the available heterologous expression system for an ANME-FsrII (this study) and MjFsrI (20) and a recently developed genetic analysis system for M. jannaschii (21), will allow detailed characterization of the Fsrs, which seem to be key factors in major marine geochemical processes. This genetic toolbox alongside recent methodological innovations in the structural analyses of proteins (61) shows significant potential for expanding our mechanistic understanding of redox active proteins in uncultured or difficult-to-grow archaea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans.

M. acetivorans C2A strain WWM60 (62) was grown in a high-salt medium with 50 mM trimethylamine (HS-TMA) as a methanogenic substrate as described previously (63). For growth in liquid culture, 25 mL or 300 mL of HS-TMA medium in a 160-mL or 530-mL serum bottle (Wheaton Science Products, Millville, NJ), respectively, was used. Inoculated cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking at 75 rpm in a C24 incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ). For growth on solid medium, agar (2% [wt/vol]) was added as a solidifying agent to the medium, and the inoculated plates were placed inside an Oxoid anaerobic jar (model HP0011A; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) which was sealed and filled with a mixture of N2 and CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) containing 7.5 ppm of H2S at a pressure of 105 Pa. The jar was left inside the anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI), which contained a mixture of N2, CO2, and H2 (76:20:4 [vol/vol/vol]), and maintained at 37°C. To select M. acetivorans strains harboring pDS701, an M. acetivorans–Escherichia coli shuttle vector, puromycin was added to the solid or liquid medium at a final concentration of 2 or 1 μg/mL, respectively.

Construction of an M. acetivorans strain expressing ANME FsrII and expression of the heterologous protein.

The coding sequence for FsrII was previously PCR amplified from the metagenomic DNA extracted from an ANME-2-dominated methane seep sediment and cloned into the plasmid pCR4-TOPO (14). For the current study, from one such clone, called Fsr-5207-6D, an expression vector for FsrII, named pDS701, was developed by following a previously described method (62); the details of this step appear in the supplemental material. This vector was introduced into M. acetivorans using a liposome-mediated transformation method, and the transformant was selected on HS-TMA solid medium containing puromycin (64). The expression of the recombinant protein, called ANME2c-FsrII-6D, in M. acetivorans(pDS701) was induced by addition of tetracycline to the liquid culture to a final concentration of 100 μg/mL, and the induced cells were examined for the expression of the heterologous protein via SDS-PAGE analysis of cell extracts.

Purification of ANME2c-FsrII-6D.

Heterologously expressed ANME2c-FsrII-6D was purified primarily by following a previously described procedure (19). All steps described below, except for the centrifugation of materials with volumes larger than 20 mL, occurred inside an anaerobic chamber that contained a mixture of N2 and H2 (96:4 [vol/vol]) and maintained at room temperature (~25°C). For the centrifugation of higher-volume materials, a Nalgene centrifuge bottle (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) was filled and sealed inside the chamber, then centrifuged outside, and taken back into the chamber for the collection of the supernatant and pellet. All column-chromatographic steps were performed employing gravity flow. Followings are the details of the purification experiment.

Six grams of wet cell pellet of M. acetivorans(pDS701) containing recombinant ANME2c-FsrII-6D was resuspended in 30 mL of a 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7 (buffer A), containing 0.2 mg/mL DNase I (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA). The resulting suspension that contained the lysed cells resulting from the osmotic shock in the low-ionic-strength solution was homogenized via serial passages through 18-, 22-, and 25-gauge needles in that sequence. The lysate was centrifuged at 48,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant obtained from this step was fractionated on ice by precipitation with ammonium sulfate at two sequential stages, representing 30% and 60% saturations of the salt. At each stage, the suspension was centrifuged at 48,000 × g and at 4°C for 20 min. The pellet from 60% (NH4)2SO4 saturated extract was dissolved in a 1 M (NH4)2SO4 solution prepared in buffer A and fractionated over chromatography resins, each packed in a 1- by 20-cm column (Econo-Column; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). The first step involved a column with 6 mL of phenyl-Sepharose resin (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) that was pre-equilibrated with 1 M (NH4)2SO4; all (NH4)2SO4 solutions were prepared in buffer A. After the sample was loaded onto it, the column bed was washed with the following (NH4)2SO4 solutions in buffer A at 1 M, 0.75 M, 0.5 M, 0.25 M, and 0 M in that sequence, and in each case the volume was 18 mL, except that the first was 36 mL. For each wash, fractions of 6-mL volumes were collected. Eluates from 0 M (NH4)2SO4 wash contained Fsr activity and were pooled. This pool was loaded onto a column packed with 6 mL of QAE-Sephadex (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) that was pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The flowthrough from the column contained Fsr activity, and the respective fractions were pooled and then loaded onto a column with 4 mL F420-Sepharose resin that was pre-equilibrated with buffer A; F420-Sepharose was prepared as described previously (19, 65, 66). The column bed was washed with the following NaCl solutions prepared in buffer A at 0 M, 0.25 M, 0.5 M, 0.75 M, and 1 M in that sequence; for the first wash, the volume was 24 mL and for each of the rest it was 12 mL. The 0.25 M NaCl fractions contained Fsr activity and were pooled. The pooled enzyme preparation was analyzed for composition via SDS-PAGE, and the observed protein bands were characterized via mass spectrometry. The enzyme preparation was also used for enzymatic activity assays.

SDS-PAGE, mass-spectrometric analysis, and size exclusion chromatography.

SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (67). For identifying the proteins present in an SDS-PAGE gel band, the tryptic peptides generated from an in-gel digestion with trypsin were separated by one-dimensional reversed-phase chromatography and analyzed on an LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (68, 69). The acquired tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data were searched using Sipros (70) against a database which was composed of the predicted proteome of Methanosarcina acetivorans (71) and a protein sequence for ANME2c-FsrII-6D (accession number QBZ96224). Initial results were filtered with a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) threshold at the peptide level estimated by the target–decoy approach (72). A minimum of two peptides, one of them unique, was required for each identified protein. Size exclusion chromatography was performed as described previously (49, 73) and detailed in the supplemental material.

Determination of flavin content of ANME2c-FsrII-6D.

From purified ANME2c-FsrII-6D, flavin was extracted via a previously described nondegradative method (74) with some modifications. A 100-μL solution of 63.2 μg purified protein in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) was combined with a 500-μL methanol-methylene chloride mixture (9:10 [vol/vol]) and vortexed vigorously for 60 s. The mixture was then supplemented with 240 μL of 0.1 M ammonium acetate pH 6.0, vortexed vigorously for 60 s, and centrifuged at 17,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. Following the centrifugation, 700 μL of the aqueous phase was filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane filter (Pall Acrodisc syringe filter; Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY). A 100-μL aliquot of this filtered extract was resolved on a 4.6- by 250-mm Vydac analytical HPLC C18 column (Separation Group, Hesperia, CA) by using a previously described method (75) with the following details. The HPLC instrumentation was the same as that which we used for size exclusion chromatography and described in the supplemental material. The solvents were a solution containing 2% acetonitrile and 27.5 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.7 (A) and 100% acetonitrile (B), and the flow rate was 0.6 mL/min. The sample was applied under a flow of 100% A, and the elution was performed with the following gradients (percent B in A): 0%, 0 to 2 min; 0% to 2%, 2 to 6 min; 2% to 10%, 6 to 15 min; 10% to 100%, 15 to 18 min; 100% (isocratic), 18 to 21 min; and 100% to 0%, 21 to 24 min. The elution was monitored at 450 nm, and the UV-visible spectra of the eluted compounds were collected by use of the diode array detector. The standards were flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The nature of the ANME2c-FsrII-6D-bound flavin was determined from the elution time and the spectrum of the eluted compound. The amount of FAD present in an extract was estimated by use of a standard plot of peak area against micromoles of FAD applied to the column.

Enzymatic activity assays.

The F420H2-dependent sulfite and nitrite reduction activities of ANME2c-FsrII-6D were measured spectrophotometrically under strictly anaerobic conditions using reduced F420 (F420H2) as the reductant and following methods described previously (19, 76). It involved the monitoring of F420H2 oxidation at 400 nm, and the reaction rate was calculated using the extinction coefficient value of 25 mM−1 cm−1 (77). For each standard assay, a 0.8-mL reaction mixture containing the following components was used: 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 40 μM F420H2, 0.5 mM DTT (if desired), 500 μM sodium sulfite or nitrite, and 12 μg purified ANME2c-FsrII-6D. Reduced F420 (F420H2) was generated via chemical reduction of F420 dissolved in water with NaBH4 (19, 49, 65), and unreacted NaBH4 was titrated using HCl.

The Fsr-N-specific partial activity of ANME2c-FsrII-6D was assayed using a strategy that has been described for F420H2 dehydrogenase (65) and used with MjFsrI (19). Here, with F420H2, Fsr-N reduces methyl viologen (MV2+) to MV·+ (reduced methyl viologen), and metronidazole continuously removes MV·+, which is a colored product of the reaction, by chemically oxidizing it to colorless MV2+ (65). This system allows an interference-free observation of the formation of F420 spectrophotometrically at 400 or 420 nm and also helps to keep the concentration of MV2+ constant (65). In our study, the assay was performed in a 0.8-mL reaction mixture containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 40 μM F420H2, 2.5 μM MV2+, and 1.5 mM metronidazole, and the reaction was monitored at 400 nm (19). The Fsr-C-specific partial reaction, the reduction of sulfite, was followed with MV·+ as the electron donor. Here, the measurement was performed using the Fsr standard assay as described above except that the electron donor was 500 μM reduced methyl viologen (MV·+), and the progress of the reaction was monitored at 560 nm (ε560 for MV·+, 8 mM−1 cm−1 [77]); MV·+ was generated by reducing MV2+ in water with a Zn wire overnight inside an anaerobic chamber (19).

The standard assay with F420H2 as the electron donor was also used to test the ability of ANME2c-FsrII-6D to reduce thiosulfate and hydroxylamine, and here, these electron acceptors were used at a final concentration of 500 μM in place of sulfite and nitrite. Similarly, the ability of the enzyme to use NADH and NADPH in place of F420H2 as electron donors was examined with sulfite and nitrite as electron acceptors, and in each case, the concentration of the reduced coenzyme was 50 μM and the progress of the reaction was followed at 340 nm. For the kinetic studies, the concentrations of the relevant substrates were varied. Coenzyme F420 was purified from Methanothermobacter marburgensis (19, 76, 78).

Assays for iron, acid-labile sulfur, sulfide, ammonia, and protein.

The iron and acid-labile sulfur contents of ANME2c-FsrII-6D were estimated via bathophenanthroline and methylene blue methods, respectively (79–81). In each case, a solution of the protein in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, was used. For iron estimation, which was performed aerobically, 100 μL of the protein solution (51 μg protein) was mixed with 100 μL of 325 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.5, and 50 μL of 10% (wt/vol) ascorbic acid. This mixture was diluted with 700 μL of distilled water and incubated at 25°C for 10 min. Then, 50 μL of a 0.5% (wt/vol) solution of bathophenanthroline in the acetate buffer was added to the mixture, and the absorbance of this final solution was read at 535 nm. Ferrous ammonium sulfate, Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, was used as the standard.

For the estimation of the acid-labile sulfur content, the first few steps occurred inside an anaerobic chamber containing a mixture of N2 and H2 (96:4 [vol/vol]), and these employed a micro-gas diffusion cell made up of a 5.6-mL, 75- by 10-mm borosilicate glass Kimax tube (Duran Wheaton Kimble, Millville, NJ) with an insert of a 30- by 3.5-mm capillary tube (Duran Wheaton Kimble, Millville, NJ) (19, 82). The annular space of the diffusion cell was filled with 100 μL of anaerobic protein solution (51 μg protein), and 20 μL of 1 M NaOH was added to the capillary. The tube was closed tightly with a No. 000 rubber stopper (EPDM rubber stopper, WidgetCo, Houston, TX). Then, 100 μL of anaerobic 1 M HCl was added to the annular space of the cell with a syringe, and the tube was incubated at 25°C for 30 min to release the acid-labile sulfur as H2S gas; H2S was trapped in the NaOH solution in the capillary. At this point, the capillary was taken out of the glass tube, and its contents were diluted with 80 μL of distilled water, pipetted out into a new glass tube, and mixed with 200 μL of a 0.5 M Zn acetate solution and 550 μL of distilled water. The tube with a suspension of ZnS precipitate was sealed with a No. 000 rubber stopper (EPDM rubber stopper, WidgetCo, Houston, TX) and brought outside the anaerobic chamber, and 100 μL of 0.1% (wt/vol) N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine in 20% (vol/vol) H2SO4 was added to it with a syringe. Then, the rubber stopper of the tube was removed, and 50 μL of 1% (wt/vol) FeCl3 in 4% (vol/vol) H2SO4 was added to the assay mixture. After incubation under air at 25°C for 15 min, the absorbance of the resultant solution was read at 670 nm. Sodium sulfide was used as the standard. From the values of Fe and sulfide (moles per microgram of protein) derived from the above-described assays, and considering that the theoretical subunit mass of the protein is 69.10 kDa, the values for the Fe and acid-labile sulfur contents of ANME2c-FsrII-6D were calculated.

The ammonia produced in an enzymatic reaction mixture was captured and assayed following the above-described protocol for the determination of acid-labile sulfur content, except that for the ammonia assay, the capillary was filled with 1 M HCl, the release of ammonia gas was initiated by the addition of 1 M NaOH to the reaction mixture that was placed in the annular space, and the ammonia concentration in the solution retrieved from the capillary was estimated via a glutamate dehydrogenase-based assay employing a kit (kit AA0100, Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein concentration was estimated via Bradford assay (83) using the dye reagent purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA).

Bioinformatics methods.

The apparent kinetic constants for the uninhibited reactions catalyzed by ANME2c-FsrII-6D were obtained by fitting the initial velocity data to the Henri-Michaelis-Menten equation: v = Vmax [S]/(Km + [S]) (where v is initial velocity, [S] is substrate concentration, Km is the Michaelis constant, and Vmax is maximum velocity) by using Solver in Microsoft Excel (84). The initial velocity data from inhibition studies were analyzed by fitting to the competitive inhibition model, v = Vmax [S]/{Km (1+[I]/Ki) + [S]} (where [I] is inhibitor concentration and Ki is the inhibition constant), using an R statistical package (85). Theoretical values for the isoelectric points (pIs) of ANME2c-FsrII-6D and MjFsrI were calculated using the ExPASy-ProtParam tool (86).

Multiple-sequence alignment of protein sequences was performed using MUSCLE (87) with default settings and the output was visualized in Jalview 2.11.0 (88). The 3D structures of MjFsrI and ANME2c-FsrII-6D were predicted by using AlphaFold2 in the default setting (35) run on the ColabFold platform (34) (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb). The predicted structures were visualized using PyMOL (PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 2.3.2; Schrödinger, LLC). Docking of prosthetic groups into the modeled 3D structures of MjFsrI and ANME2c-FsrII-6D were performed as a structural alignment by employing the align command line in PyMOL; for the N-terminal half (Fsr-N), the alignment was performed with the Methanothermobacter marburgensis F420-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenase subunit B (FrhB; PDB ID 3ZFS, chain C), and for the C-terminal half (Fsr-C), it was performed with the Archaeoglobus fulgidus dissimilatory sulfite reductase subunit A (DsrA; PDB ID 3MM5, chain A).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William W. Metcalf of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his laboratory members for providing Methanosarcina acetivorans strains, plasmids, and protocols that have been used in the study for the heterologous expression of FNiR. We also thank Kylie Allen of the Virginia Tech Department of Biochemistry for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Astrobiology: Exobiology and Evolutionary Biology grant NNX13AI05G to B.M. and the Virginia Tech Agricultural Experiment Station Hatch Program (CRIS project VA-160021). C.H. was supported with a fellowship from the Genetics, Bioinformatics, and Computational Biology Ph.D. Program of the Virginia Tech. This work was also supported in part by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Marine Symbiosis program (GBMF grant 9324) and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, award number DE-SC0020373 to V.J.O.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

[This article was published on 13 June 2022 with a standard copyright line (“© 2022 American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.”). The authors elected to pay for open access for the article after publication, necessitating replacement of the original copyright line with the one above, and this change was made in the current version, posted on 29 June 2022.]

Contributor Information

Victoria J. Orphan, Email: vorphan@gps.caltech.edu.

Biswarup Mukhopadhyay, Email: biswarup@vt.edu.

Julie A. Maupin-Furlow, University of Florida

REFERENCES

- 1.Reeburgh WS. 2007. Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem Rev 107:486–513. 10.1021/cr050362v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knittel K, Boetius A. 2009. Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process. Annu Rev Microbiol 63:311–334. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milucka J, Ferdelman TG, Polerecky L, Franzke D, Wegener G, Schmid M, Lieberwirth I, Wagner M, Widdel F, Kuypers MM. 2012. Zero-valent sulphur is a key intermediate in marine methane oxidation. Nature 491:541–546. 10.1038/nature11656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiber L, Holler T, Knittel K, Meyerdierks A, Amann R. 2010. Identification of the dominant sulfate-reducing bacterial partner of anaerobic methanotrophs of the ANME-2 clade. Environ Microbiol 12:2327–2340. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chadwick GL, Skennerton CT, Laso-Perez R, Leu AO, Speth DR, Yu H, Morgan-Lang C, Hatzenpichler R, Goudeau D, Malmstrom R, Brazelton WJ, Woyke T, Hallam SJ, Tyson GW, Wegener G, Boetius A, Orphan VJ. 2022. Comparative genomics reveals electron transfer and syntrophic mechanisms differentiating methanotrophic and methanogenic archaea. PLoS Biol 20:e3001508. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinke C, Chuvochina M, Mussig AJ, Chaumeil PA, Davin AA, Waite DW, Whitman WB, Parks DH, Hugenholtz P. 2021. A standardized archaeal taxonomy for the Genome Taxonomy Database. Nat Microbiol 6:946–959. 10.1038/s41564-021-00918-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wegener G, Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Tegetmeyer HE, Boetius A. 2015. Intercellular wiring enables electron transfer between methanotrophic archaea and bacteria. Nature 526:587–590. 10.1038/nature15733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyerdierks A, Kube M, Kostadinov I, Teeling H, Glockner FO, Reinhardt R, Amann R. 2010. Metagenome and mRNA expression analyses of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea of the ANME-1 group. Environ Microbiol 12:422–439. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheller S, Yu H, Chadwick GL, McGlynn SE, Orphan VJ. 2016. Artificial electron acceptors decouple archaeal methane oxidation from sulfate reduction. Science 351:703–707. 10.1126/science.aad7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skennerton CT, Chourey K, Iyer R, Hettich RL, Tyson GW, Orphan VJ. 2017. Methane-fueled syntrophy through extracellular electron transfer: uncovering the genomic traits conserved within diverse bacterial partners of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea. mBio 8:e01561-17. 10.1128/mBio.01561-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGlynn SE, Chadwick GL, Kempes CP, Orphan VJ. 2015. Single cell activity reveals direct electron transfer in methanotrophic consortia. Nature 526:531–535. 10.1038/nature15512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGlynn SE. 2017. Energy metabolism during anaerobic methane oxidation in ANME archaea. Microbes Environ 32:5–13. 10.1264/jsme2.ME16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Chadwick GL, Kempes CP, Orphan VJ, Meile C. 2021. Controls on interspecies electron transport and size limitation of anaerobically methane-oxidizing microbial consortia. mBio 12:e03620-20. 10.1128/mBio.03620-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H, Susanti D, McGlynn SE, Skennerton CT, Chourey K, Iyer R, Scheller S, Tavormina PL, Hettich RL, Mukhopadhyay B, Orphan VJ. 2018. Comparative genomics and proteomic analysis of assimilatory sulfate reduction pathways in anaerobic methanotrophic archaea. Front Microbiol 9:2917. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Skennerton CT, Chadwick GL, Leu AO, Aoki M, Tyson GW, Orphan VJ. 2022. Sulfate differentially stimulates but is not respired by diverse anaerobic methanotrophic archaea. ISME J 16:168–177. 10.1038/s41396-021-01047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Gruber-Vodicka HR, Buttigieg PL, Tegetmeyer HE, Boetius A, Wegener G. 2018. Gene expression and ultrastructure of meso- and thermophilic methanotrophic consortia. Environ Microbiol 20:1651–1666. 10.1111/1462-2920.14077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milucka J, Widdel F, Shima S. 2013. Immunological detection of enzymes for sulfate reduction in anaerobic methane-oxidizing consortia. Environ Microbiol 15:1561–1571. 10.1111/1462-2920.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang FP, Zhang Y, Chen Y, He Y, Qi J, Hinrichs KU, Zhang XX, Xiao X, Boon N. 2014. Methanotrophic archaea possessing diverging methane-oxidizing and electron-transporting pathways. ISME J 8:1069–1078. 10.1038/ismej.2013.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson EF, Mukhopadhyay B. 2005. A new type of sulfite reductase, a novel coenzyme F420-dependent enzyme, from the methanarchaeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. J Biol Chem 280:38776–38786. 10.1074/jbc.M503492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson EF, Mukhopadhyay B. 2008. Coenzyme F420-dependent sulfite reductase-enabled sulfite detoxification and use of sulfite as a sole sulfur source by Methanococcus maripaludis. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3591–3595. 10.1128/AEM.00098-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Susanti D, Frazier MC, Mukhopadhyay B. 2019. A genetic system for Methanocaldococcus jannaschii: an evolutionary deeply rooted hyperthermophilic methanarchaeon. Front Microbiol 10:1256. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susanti D, Mukhopadhyay B. 2012. An intertwined evolutionary history of methanogenic archaea and sulfate reduction. PLoS One 7:e45313. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]