Abstract

Background & Aims

Though lifestyle interventions can reverse disease progression in people with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease/non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH), unawareness about disease severity might compromise behavioural changes. Data from this first international cross‐sectional survey of individuals with NAFLD/NASH were used to identify correlates of both unawareness about fibrosis stage and its association with adherence to lifestyle adjustments.

Methods

Adults with NAFLD/NASH registered on the platform Carenity were invited to participate in an online 20‐min, six‐section survey in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom to describe their experience with NAFLD/NASH and its care (N = 1411). Weighted binary and multinomial logistic regressions were performed to estimate the effect of explanatory variables on unawareness of fibrosis stage and poor adherence to lifestyle changes respectively.

Results

In the study group, 15.5% had obesity and 59.2% did not know their fibrosis stage. After multiple adjustments, individuals with a body mass index (BMI) ≥35 were over twice as likely to not know their fibrosis stage. People with a BMI >30 had a threefold higher risk of having poor adherence to lifestyle changes. Unawareness about fibrosis stage was also significantly associated with poor adherence to lifestyle adjustments.

Conclusions

As fibrosis stage is becoming the main predictor of NAFLD progression, improving patient–provider communication—especially for people with obesity—about liver fibrosis stage, its associated risks and how to mitigate them, is needed. Training for healthcare professionals and promoting patient educational programmes to support behaviour changes should also be included in the liver health agenda.

Keywords: cross‐sectional study, lifestyle interventions, liver disease, patient–provider relationship

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- NASH

non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NAFLD

non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

- PCP

primary care physician

Lay Summary

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is managed with lifestyle interventions, but unawareness of liver disease severity may compromise adherence to these. NAFLD/NASH patients were surveyed to identify correlates of unawareness about fibrosis stage and its association with adherence to lifestyle changes with findings showing that those with a BMI ≥35 were over twice as likely not to know their fibrosis stage and that unawareness of fibrosis stage and moderate or severe obesity were significantly correlated to poor adherence to lifestyle interventions. As fibrosis stage is becoming the main predictor of NAFLD progression, improving patient–provider communication—especially for people with obesity—about liver fibrosis stage, its associated risks and how to mitigate them as well as promoting patient educational programmes to support behaviour changes, should be included in the liver health agenda.

1. INTRODUCTION

The rapid rise in the obesity epidemic worldwide, coupled with a potential end to the hepatitis C virus epidemic, enabled by the widespread use of direct‐acting antiviral therapy, have shifted the focus of public health and clinical liver disease actors towards non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) prevention and care. 1 Insulin resistance is key in NAFLD pathogenesis, and is very prevalent in people with diabetes and/or obesity. Even modest weight gain (i.e., 3–5 kg) is predictive of NAFLD development, irrespective of baseline body mass index (BMI). 2

NAFLD includes a spectrum of conditions ranging from steatosis (i.e., elevated levels of fat in the liver) to non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is an inflammatory and fibrotic stage of NAFLD that may progress to severe liver complications like cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and end‐stage liver disease. 3 Several drugs are currently under clinical development to limit inflammation and progression to advanced stages of liver fibrosis. 4 In parallel, there is increasing evidence that lifestyle interventions (e.g., dietary changes and exercise) are an effective first‐line approach for NAFLD management and prevention of NASH. For instance, consumption of specific polyphenol‐rich products (e.g., coffee and green tea, particularly) can potentially slow the progression of both NAFLD 5 , 6 and fibrosis. 7 , 8 , 9 Accordingly, lifestyle adjustments should be implemented from the first evidence of steatosis.

Substantial weight loss has been demonstrated to reverse liver disease in patients with steatosis and NASH. 10 However, sustained lifestyle changes and weight loss may be difficult‐to‐reach objectives in this population. 11 The intensive coaching needed to promote adherence to weight stabilisation programmes 10 may also be expensive and unsustainable. On the contrary, healthy nutritional habits, like following a Mediterranean diet, have been shown to be successful in reducing liver fat content, even without weight loss. 12

The main risk in patients with NAFLD/NASH is fibrosis progression. Health risks associated with this progression are often underestimated. Even in the nomenclature of the disease, the terms ‘fatty’ and ‘non‐alcoholic’ are incorporated in the definition, undermining the fibrosis risk compared to the ‘fatty’ risk, which carries over into the dialogue that healthcare providers have with patients. Consequently, as a result of misinformation and miscommunication, people with NAFLD/NASH may underestimate the graveness of the disease—seeing it as just a weight loss issue—and remain unaware of the importance of assessing and monitoring fibrosis stage. 13 Presently, it is unknown to what extent unawareness about fibrosis status may lead people with NAFLD/NASH to underestimate disease severity and hinder efforts by professionals to encourage these individuals to adhere to lifestyle adjustments. The latter could be exacerbated in people with obesity, a population which is often stigmatised in healthcare settings 14 , 15 and may be less exposed to comprehensive information about liver disease.

We conducted the first international survey of people with NAFLD/NASH to identify correlates of a lack of knowledge about fibrosis status and assess whether this unawareness was associated with poor adherence to lifestyle changes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Enrolment

Between 21 February and 16 September 2020, adults who were diagnosed with NAFLD/NASH by a physician registered on the online patient community platform Carenity were invited to participate in a survey in six countries: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. The Carenity platform was designed to help people living with chronic diseases better share their experience and find support and information from other patients about how to self‐manage their disease(s) and improve their quality of life.

The International NASH Patient Survey aimed to: (i) contextualise the unmet needs of all patients with NAFLD/NASH and (ii) understand the perception gap between patients and physicians about what NAFLD/NASH is and how it can be detrimental for health. It also aimed to estimate patients' knowledge of NAFLD/NASH and advanced fibrosis and assess their experience of current and prior interactions with healthcare professionals.

The study group included 1411 participants with NAFLD/NASH who completed the 20‐min online questionnaire detailing their knowledge of and experience with this disease and related care.

2.2. Data collection

The online questionnaire consisted of six sections, each exploring specific domains of the patients' experience with NAFLD/NASH care and associated comorbidities (Table 1). Based on responses, four scores were built as factors that affect the lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage and poor adherence to lifestyle changes (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Survey sections and descriptions

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Demographics | Questions about gender, education level, ethnicity and place of residence |

| 2. NASH diagnosis | Questions around the NASH diagnosis process (e.g., healthcare provider responsible for diagnosing, tests involved and information provided) |

| 3. Putting communication around NASH into context | Questions about interactions with and information received from healthcare providers, and the availability and quality of information in general, regarding health conditions like NASH and others (e.g., T2D, heart disease and obesity), and how this translates into treatment adherence (i.e., lifestyle adjustments) |

| 4. NASH experiences & ‘IQ’ | Questions around living with NASH (e.g., feelings about the diagnosis; understanding of the condition, its impact on health and its progression; types of health providers involved in its management and level of care received; and information and support received around treatment [i.e., lifestyle changes]) |

| 5. NASH communication deep dive | Questions about the specifics of information received around NASH (e.g., terms used upon diagnosis [i.e., liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and cancer] and level of understanding of these) and level of comfort in disclosing information about NASH and other diagnoses (e.g., T2D, heart disease and obesity) to others (i.e., family, friends and co‐workers) |

| 6. NASH’s impact on daily life | Questions around the impact of NASH on daily life (e.g., on health, mood, self‐care, activities of daily living, work, leisure and interactions with others [i.e., friends and family]) |

Notes: Prior to the main survey, participants answered screening questions (e.g., age, diagnosis/diagnoses received [e.g., T2D, high blood pressure, hyperlipidaemia and NASH], level of knowledge about their health status in relation to these [e.g., haemoglobin A1C, blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and liver function test results] and their interpretation of this information [i.e., how advanced they perceived their health condition to be based on this information]).

Abbreviations: IQ, intelligence quotient; NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

TABLE 2.

Descriptions of scores affecting study outcomes

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Information received from the physician and other healthcare staff (range 0–13). This score was the sum of the answers to 13 dichotomous items (no = 0 and yes = 1), each referring to a specific aspect of liver disease (from blood test results to treatments currently in development) |

| 2 | The number of healthcare staff managing their disease (range 0–10). This score was the sum of the answers to 10 proposed items, each representing care received from a specific healthcare professional (e.g., cardiologist, diabetologist, dietician, etc.) |

| 3 | A disclosure score (range 0–5) expressing the level of disease disclosure to close or extended family members, friends, colleagues and work supervisors, calculated as the sum total of five dichotomous items (no = 0 and yes = 1) |

| 4 | Level of knowledge about health complications regarding NAFLD/NASH progression (range 0–7). This score was the sum of the answers to 7 dichotomous items (no = 0 and yes = 1) about consequences associated with the disease (e.g., cancer, cirrhosis, fibrosis, liver failure, the need for liver transplantation, liver damage or none) |

Abbreviations: NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis.

2.3. Outcomes

Two outcomes were chosen: lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage and poor adherence to lifestyle changes. With respect to the former, we sought to characterise individuals who did not know their fibrosis stage and verify whether people with obesity were more unaware of their fibrosis stage than people without obesity, as we presumed that patient–provider communication focuses more on weight loss than fibrosis risk.

With respect to the latter, we wanted to verify to what extent a lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage, but also having obesity, predicted poor adherence to lifestyle changes, while accounting for potential confounders, including BMI.

Classification criteria for both outcomes are outlined in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Study outcome classification criteria

| Outcome | Classification criteria |

|---|---|

| Lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage |

An individual was classified as knowing their fibrosis stage if they answered ‘yes’ to at least one of the following three questions:

Respondents who answered ‘no’ to all three were classified as not knowing their fibrosis stage |

| Poor adherence to lifestyle changes |

Individuals were categorised into the following three groups:

|

Abbreviations: F0‐F4, fibrosis score 0‐fibrosis score 4; F‐score, fibrosis score; NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis.

2.4. Potential explanatory variables

2.4.1. Knowledge of liver fibrosis

Among the main potential explanatory variables, we explored sociodemographic variables, area and country of origin, obesity and severe obesity (estimated via BMI), how advanced participants perceived their liver disease to be, time since diagnosis, discussion of biological results with their physician, a score about the information received from their physician and other healthcare staff about the disease, receiving information from their doctor about the different stages of fibrosis, the number of healthcare staff managing their disease and the level of liver disease disclosure to family members.

Other variables explored were knowledge about their biological markers (e.g., low‐density lipoprotein level), comorbidities, general understanding of fibrosis, type of healthcare professional diagnosing them with NAFLD/NASH, general knowledge and understanding of NAFLD/NASH progression, time devoted by the prescribing physician to provide them with information, general understanding of what fibrosis stages are and current health issues being treated other than NAFLD/NASH (Tables 4 and 5).

TABLE 4.

Independent factors associated with lack of knowledge of fibrosis score (weighted logistic regression, crude odds ratios [OR] and adjusted odds ratios [AOR] and their 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] N = 1411)

| Characteristics | Fibrosis score a | Univariable analysis a | Multivariable analysis a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known 40.8% | Unknown 59.2% | OR | 95% CI | p‐value | AOR | 95% CI | p‐value | |||

| % | % | |||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 67.6 | 32.4 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 30–39 | 51.3 | 48.7 | 1.98 | 1.13 | 3.46 | .016 | 2.37 | 1.18 | 4.82 | .017 |

| 40–49 | 43.7 | 56.3 | 2.69 | 1.57 | 4.61 | <.001 | 2.48 | 1.22 | 5.04 | .012 |

| 50–59 | 39.5 | 60.5 | 3.19 | 1.9 | 5.37 | <.001 | 2.51 | 1.28 | 4.89 | .007 |

| 60+ | 31.3 | 68.7 | 4.57 | 2.67 | 7.81 | <.001 | 3.65 | 1.84 | 7.24 | <.001 |

| Country | ||||||||||

| UK | 47.2 | 52.8 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Germany | 35.2 | 64.8 | 1.64 | 1.10 | 2.47 | .016 | 1.32 | 0.72 | 2.40 | .372 |

| France | 36.6 | 63.4 | 1.55 | 0.98 | 2.44 | .061 | 1.18 | 0.62 | 2.23 | .611 |

| Canada | 40.5 | 59.5 | 1.31 | 0.83 | 2.07 | .245 | 1.48 | 0.77 | 2.82 | .240 |

| Italy | 32.1 | 67.9 | 1.89 | 1.21 | 2.95 | .002 | 2.34 | 1.24 | 4.40 | .008 |

| Spain | 51.8 | 48.2 | 0.83 | 0.53 | 1.30 | .420 | 1.45 | 0.80 | 2.66 | .223 |

| Have you discussed the results of your liver function tests with your doctor in the past year? | ||||||||||

| No | 20.5 | 79.5 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 57.8 | 42.2 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.25 | <.001 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.36 | <.001 |

| BMI | ||||||||||

| <20 | 43.9 | 56.1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| [20–25[ | 54.0 | 46.0 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 7.45 | .740 | 0.26 | 0.004 | 18.44 | .534 |

| [25–30[ | 43.4 | 56.6 | 1.02 | 0.47 | 2.22 | .957 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 2.52 | .828 |

| [30–35[ | 36.5 | 63.5 | 1.36 | 0.85 | 2.19 | .196 | 1.27 | 0.61 | 2.65 | .527 |

| ≥35 | 28.3 | 71.7 | 1.99 | 1.38 | 2.86 | <.001 | 2.26 | 1.37 | 3.40 | .001 |

| How advanced do you believe your NAFLD is? | ||||||||||

| Early stage | 34.8 | 65.2 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Advanced stage | 61.8 | 38.2 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.46 | <.001 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.38 | <.001 |

| How long ago were you diagnosed with NAFLD/NASH? | ||||||||||

| <1 year | 35.3 | 64.7 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| [1–5 years[ | 48.8 | 51.2 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.79 | .001 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.91 | .017 |

| [5–10 years[ | 40.2 | 59.8 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.23 | .325 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 1.25 | .211 |

| [10–20 years[ | 26.7 | 73.3 | 1.50 | 0.88 | 2.54 | .136 | 1.05 | 0.46 | 2.38 | .906 |

| ≥20 years | 25.1 | 74.9 | 1.63 | 0.64 | 4.16 | .306 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.54 | .287 |

| Score 1: information received by the physician and other healthcare staff about the disease | ||||||||||

| Mean [95% CI] | 4.7 [4.4–5.0] | 2.7 [2.6–2.9] | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.77 | <.001 | 0.9 | 0.84 | 0.98 | .012 |

| As best as you can remember, did your doctor explain the different stages? | ||||||||||

| No | 24.5 | 75.5 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 67.1 | 32.9 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.22 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.39 | <.001 |

| I do not remember | 29.3 | 70.7 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1.18 | .248 | 0.93 | 0.56 | 1.53 | .755 |

| Score 2: number of healthcare staff managing their disease | ||||||||||

| Mean [95% CI] | 1.5 [1.4–1.6] | 0.9 [0.8–1.0] | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.60 | <.001 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.93 | .011 |

| Score 3: score expressing level of disease disclosure to family members, friends and colleagues | ||||||||||

| Mean [95% CI] | 3.2 [3.0–3.3] | 2.1 [1.9–2.2] | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.7 | <.001 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.90 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis; ref, reference category.

All analyses are weighted with weight proportional to the age‐gender distribution of a population with NAFLD/NASH, in order to control for selection bias of participants and allow for inter‐country comparisons.

TABLE 5.

Other characteristics of patients associated with their knowledge of their score of fibrosis (weighted logistic regression, crude odds ratios [OR] and their 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] N = 1411)

| Characteristics | Fibrosis score | Univariable analysis a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Known 40.8% |

Unknown 59.2% |

OR | 95% CI | p‐value | ||

| % | % | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 47.1 | 52.3 | Ref | |||

| Female | 33.4 | 66.6 | 1.77 | 1.37 | 2.3 | <.001 |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary/elementary | 53.2 | 46.8 | Ref | |||

| Lower secondary school | 27.7 | 72.3 | 2.97 | 1.03 | 8.54 | .044 |

| Other | 42.1 | 57.9 | 1.56 | 0.59 | 4.15 | .589 |

| Score 4: Number of complications after liver disease progressed | ||||||

| Mean [95% CI] | 3.69 [3.50–3.88] | 2.74 [2.58–2.91] | 0.782 | 0.73 | 0.84 | <.001 |

| I have a good understanding of how NASH progresses over time | ||||||

| Strongly disagree | 20.8 | 79.2 | ||||

| Somewhat disagree | 33.8 | 66.2 | 0.514 | 0.330 | 0.802 | <.001 |

| Somewhat agree | 50.3 | 49.7 | 0.258 | 0.172 | 0.388 | <.001 |

| Strongly agree | 52.7 | 47.3 | 0.235 | 0.143 | 0.384 | <.001 |

| Please indicate the type of area where you live in | ||||||

| I live in a city or urban area | 48.0 | 52.0 | Ref | |||

| I live in a medium‐sized town or suburb | 39.1 | 60.9 | 1.44 | 1.03 | 2.01 | .031 |

| I live in a small town or rural area | 32.1 | 67.9 | 1.96 | 1.43 | 2.67 | <.001 |

| Comorbidities (any disease besides NAFLD/NASH) | ||||||

| 0 | 47.8 | 52.2 | Ref | |||

| 1–2 | 38.3 | 61.7 | 1.48 | 1.1 | 1.98 | .009 |

| 3 or more | 36.2 | 63.8 | 1.61 | 1.1 | 2.37 | .015 |

| What my test results say about the health of my liver | ||||||

| No understanding/little understanding | 27.5 | 72.5 | Ref | |||

| Adequate/complete understanding | 51.0 | 49.0 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.48 | <.001 |

| How easy do you find it to talk to other people about the conditions you are living with in regards to NAFLD/NASH? | ||||||

| Difficult | 36.0 | 64.0 | Ref | |||

| Easy | 47.7 | 52.3 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.80 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis; ref, reference category.

All analyses are weighted with weight proportional to the age‐gender distribution of a population with NAFLD/NASH, in order to control for selection bias of participants and allow for inter‐country comparisons.

2.4.2. Adherence to lifestyle changes

The main potential predictors for this outcome were knowledge of liver fibrosis (first outcome [see above]), sociodemographic variables, area and country of origin, BMI and persons who provided support for lifestyle changes. Other variables tested included the level of general knowledge and understanding of NAFLD/NASH progression and disclosure to others, whether information was received about fibrosis from healthcare staff, perceptions and experiences about NAFLD/NASH diagnosis, and number of health staff currently managing their disease.

2.5. Statistical methods

The dataset was weighted using the age‐sex distribution of patients with NASH in the US 16 which was used as a ‘standard population’ to enable inter‐country comparisons. Variables were expressed as a weighted percentage with respect to the whole study group.

Weighted binary and multinomial logistic regressions were performed to estimate the effect of explanatory variables on both study outcomes, respectively, in univariable and multivariable analyses. Final multivariable models were built by including variables with a liberal p < .2 in the univariable analysis and maintaining them if they remained significantly associated with the outcome (p < .05), even when the other correlates were entered. Odds ratios, p‐values and 95% confidence intervals were computed. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 16 for Windows) software (StataCorp).

3. RESULTS

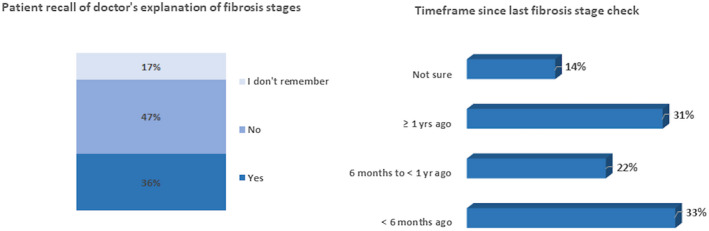

The number of participants per country ranged from 218 (Italy) to 276 (UK). Men accounted for 54.1% of the total, 15.5% had obesity, 69.6% had comorbidities and, independently from their knowledge of their liver fibrosis stage, 75.3% of NAFLD/NASH patients perceived themselves as being in an early fibrosis stage. Sex‐age distributions were similar across all countries. Of the total, 59.2% did not know their fibrosis stage and 34.4% and 14.0% were either non‐adherent to lifestyle changes or reported that these did not concern them respectively. Twenty‐three percent reported feeling overwhelmed when diagnosed with NAFLD/NASH. One‐fifth (19.4%) reported three or more comorbidities, while 31.1% reported that it had been over a year since their last fibrosis assessment (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient recall of doctor’s explanation on fibrosis stages and timeframe since last fibrosis stage

Most patients were diagnosed by a hepatologist (27.1%), gastroenterologist (25.6%) or a primary care physician (PCP)/general practitioner (20.3%). A quarter (24.7%) had been diagnosed <1 year before the study, 43.1% between 1 and 5 years before and 32.3% more than 5 years before. Just over half (54.7%) of patients had a fibrosis stage assessment within the previous 12 months. More than half of the study sample received support to make the necessary lifestyle changes from family/friends, doctors and other healthcare professionals.

Specifically, among people with NAFLD/NASH who reported comorbidities, 84.0% and 78.3% thought that they had early‐stage fibrosis, while 32.6% and 34.0% reported having little/no understanding about fibrosis or cirrhosis consequences. Furthermore, 56.9% of the whole study sample reported having little/no understanding of the signs indicative of deteriorating NAFLD/NASH. Only 14.0% reported a good understanding about NAFLD/NASH progression.

3.1. Factors associated with a lack of knowledge about fibrosis stage

Table 4 reports the univariable and multivariable analyses of the main independent correlates of lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage (i.e., the first outcome). The results show that after adjustment for age, country of origin and no self‐reported advanced stage fibrosis, individuals who were aware of their fibrosis stage were more likely to have discussed their liver tests with their physician in the last year, to have received more information from different healthcare providers (in particular from their main provider about the various stages of NAFLD/NASH) and to have been diagnosed between 1 and 5 years before the survey. The higher the number of health staff managing their disease (a proxy of disease severity) the higher the probability was that they knew their fibrosis stage. Interestingly, the level of participant disclosure of their liver disease to family/friends/colleagues was significantly positively associated with knowledge of fibrosis stage. People with severe obesity (BMI ≥35) were over two times more likely not to know their liver fibrosis status. Other variables associated with a lack of knowledge of fibrosis stage, which were not entered in the final multivariable model, are presented in Table 5.

3.2. Factors associated with poor adherence to lifestyle changes

Table 6 reports factors associated with poor adherence versus high adherence to lifestyle changes (univariable and multivariable analysis) and predictors of reporting not to be concerned by lifestyle changes versus high adherence. We will only discuss the results for the first comparison, as it is difficult to characterise individuals who did not feel concerned, as they include people who did not answer or people who were not informed by their main healthcare provider about the need for lifestyle changes. After multiple adjustments, a lack of knowledge about fibrosis stage was significantly associated with poor adherence to lifestyle changes; women were less likely to be adherent to lifestyle adjustments than men. People with obesity (BMI ≥30) had a threefold higher risk of having poor adherence to lifestyle changes. People reporting having received support from nurses and other health staff were 63.0% less likely to have poor adherence (i.e., 2.7 times more likely to be adherent) to lifestyle adjustments.

TABLE 6.

Predictors of non‐adherence to lifestyle changes (multinomial weighted logistic regression a , crude odds ratios [OR] and adjusted odds ratios [AOR] and their 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] N = 1411)

| Characteristics | Lifestyle changes | Multivariable analysis b | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor versus good adherence | Poor versus good adherence | ||||||||||

| Good adherence (51.6%) | Poor adherence (34.4%) | Not a concerned (14.0%) | OR | 95% CI | p‐value | AOR | 95% CI | p‐value | |||

| % | % | % | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 59.1 | 32.5 | 8.40 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Female | 42.8 | 36.6 | 20.6 | 1.55 | 1.17 | 2.06 | .002 | 1.44 | 1.02 | 2.01 | .040 |

| Countries | |||||||||||

| UK | 43.5 | 27.8 | 28.7 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Germany | 41.9 | 44.1 | 14.0 | 1.65 | 1.05 | 2.59 | .031 | 1.32 | 0.75 | 2.33 | .337 |

| France | 37.2 | 46.2 | 16.6 | 1.95 | 1.18 | 3.22 | .010 | 1.90 | 1.04 | 3.50 | .037 |

| Canada | 63.4 | 34.1 | 2.50 | 0.84 | 0.50 | 1.40 | .505 | 0.70 | 0.39 | 1.29 | .258 |

| Italy | 63.6 | 27.3 | 9.10 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 1.14 | .142 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.92 | .027 |

| Spain | 62.9 | 27.2 | 9.90 | 0.68 | 0.40 | 1.15 | .148 | 0.88 | 0.49 | 1.59 | .681 |

| BMI | |||||||||||

| <20 | 59.2 | 27.8 | 13.0 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| [20–25[ | 24.8 | 46.0 | 29.2 | 3.96 | 0.87 | 63.4 | .330 | 2.39 | 0.10 | 62.5 | .587 |

| [25–30[ | 48.9 | 40.1 | 11.0 | 1.75 | 0.77 | 3.97 | .180 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 2.75 | .944 |

| [30–35[ | 33.7 | 47.6 | 18.7 | 3.00 | 1.80 | 5.00 | <.001 | 3.12 | 1.74 | 5.60 | <.001 |

| ≥35 | 28.6 | 55.4 | 16.0 | 4.14 | 2.74 | 6.23 | <.001 | 2.98 | 1.82 | 4.87 | <.001 |

| Fibrosis score | |||||||||||

| Known | 66.8 | 26.2 | 7.0 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Unknown | 41.2 | 40.0 | 18.8 | 2.48 | 1.84 | 3.33 | <.001 | 1.70 | 1.14 | 2.41 | .008 |

| Nurse support c | |||||||||||

| Poor | 37.9 | 43.2 | 18.9 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Good | 71.3 | 22.9 | 5.8 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.39 | <.001 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.54 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ref, reference category.

Only the results comparing poor adherence versus good adherence to lifestyle changes were reported as the comparison of ‘not concerned’ versus good adherence was meaningless.

All analyses are weighted with weight proportional to the age‐gender distribution of a population with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease/non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis, in order to control for selection bias of participants and allow for inter‐country comparisons.

Nurses and other health staff other than physicians for lifestyle changes; poor = no+low, good = moderate+high.

4. DISCUSSION

This study investigating the perceptions and experiences of people with NAFLD/NASH with their disease and the care received is the first multi‐country study performing an in‐depth exploration of this population’s knowledge about their disease and their needs. There are two major findings: first, people with severe obesity were, paradoxically, those who most frequently reported not knowing their fibrosis stage. Second, poor adherence to lifestyle changes was more frequent in people who were unaware of their fibrosis stage and in people with obesity. A secondary, but important, finding was that women were more likely to report poor adherence to lifestyle changes in comparison with men.

Monitoring fibrosis status in people with NAFLD/NASH is a pillar of disease management 3 , 4 , 17 because of the negative prognosis owing to its progression. 18 Unfortunately, identifying novel non‐invasive markers of fibrosis for patient subtypes and for monitoring the effectiveness of interventions is challenging. 17 , 19 Paradoxically, while research into the clinical management of people with NAFLD/NASH, novel treatments and combined approaches all expand care perspectives for this patient population, 4 , 10 our results showed a profound lack of knowledge about the disease—and especially fibrosis stage—in a considerable number of the participants in this study. This lack of knowledge clearly depends on the quality and quantity of patient–provider communication, as was confirmed by the fact that people aware of their fibrosis stage reported having discussed their liver tests with their physician in the previous year and receiving more information from different healthcare providers, especially a general explanation about their NAFLD/NASH stage from their main physician. The lack of information highlighted here may reflect the possibility that some healthcare providers had limited knowledge about the disease and that some only made limited use of fibrosis markers to monitor it. Previous research 13 found that only 18%, 30% and 65% of PCPs, endocrinologists and gastroenterologists, respectively, reported using fibrosis scores in clinical practice, and that less than half of endocrinologists and PCPs indicated that they would refer a patient with suspected NASH to a specialist. To improve information provision for patients, healthcare providers should engage in more thorough discussion with them regarding NAFLD/NASH (e.g., their fibrosis stage, associated risks and how to prevent progression) and make use of new informative tools like the ‘Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: A patient guideline’ 20 (and the accompanying short version of it), which covers the disease in detail and was co‐created with patient group representatives, clinicians and public health experts.

The number of healthcare providers managing the participant’s disease (NAFLD/NASH) was associated with better knowledge of fibrosis stage. This correlate should be interpreted as an indirect indicator of the severity of the disease (i.e., patients with a more severe fibrosis stage are more aware of it) but also of a more comprehensive care model fulfilling the needs of this population in terms of access to and receipt of care. 21 This result is in line with the hypothesis that people with advanced disease are more aware of their fibrosis stage. By contrast, people with obesity—a population at higher risk of fibrosis progression—were less knowledgeable about their fibrosis status, perhaps because their physicians were more likely to speak about the risks associated with being overweight and the importance of weight loss for reducing their cardiometabolic risk, than about their fibrosis progression. Indeed, for years, liver health has not been prioritised (and, in some cases, is completely neglected) in guidelines for physicians and nurses 22 for the management of people with obesity. 23 Although we cannot exclude that stigmatising attitudes by healthcare providers and discrimination can worsen many outcomes, 24 it is probable that some providers may simply have so‐called ‘inertia’ 23 ‐ defined as the failure to establish appropriate targets and escalate treatment to achieve treatment goals–and are also unable to deliver specific up‐to‐date information on liver health to this population. In any case, the result is the same: people with obesity do not receive comprehensive information about liver‐associated risks. Furthermore, patients diagnosed between 1 and 5 years before the date of the survey were more likely to report that they were aware of their fibrosis stage than those recently diagnosed; this association was undoubtedly a proxy of continued recent care and better recall of information provided by health staff.

In terms of the adherence to lifestyle changes, individuals with no knowledge about liver fibrosis had a 70% higher risk of poor adherence than those who were aware of their fibrosis stage. This confirms our initial hypothesis, independently of the country of origin. We also found that support provided by nurses may foster engagement in the lifestyle changes necessary to reduce the severity of NAFLD/NASH. Support from other healthcare professionals was associated with this outcome in the univariable analysis, but not in the multivariable analysis. As both the obesity and NAFLD /NASH epidemics continue to worsen and given that lifestyle changes are currently the most effective strategy to reverse the course of NAFLD/NASH, 2 the involvement of nurses in treatment education programmes 25 may expand the number of entry points for liver care for people with NAFLD/NASH.

The involvement of nurses but also of other healthcare staff in patient treatment education 26 , 27 can be particularly relevant for patients with obesity, and also for women with NAFLD/NASH, as in our study, both of these groups were at higher risk of not adhering to lifestyle changes. The lower adherence to lifestyle change adjustments in women in our study is not consistent with a previous systematic review targeting people with obesity regardless of NAFLD/NASH comorbidities, 28 which found that men were at higher risk of non‐adherence to such programmes. Perhaps, our result is related to the specificity of our study sample, as they already had NAFLD/NASH.

As logistic regression is a multiplicative model, this means that women with obesity who were unaware of their liver fibrosis stage had an almost 12‐fold greater risk of poor adherence to lifestyle changes. This suggests the need for gender‐specific interventions which better target women, in particular women with obesity, as they constitute a highly stigmatised group in all settings, including healthcare. 29

Considering country effects, people in Italy were almost twice as likely to not know their fibrosis stage compared with the UK, where a lack of knowledge about fibrosis stage was less prevalent than the other countries. We do not know whether the better knowledge about fibrosis status in patients in the UK can be interpreted in terms of better information given by health providers and ultimately country preparedness for NASH management. 30 The results of better adherence to lifestyle changes in Italy and Spain may both reflect the easiness of adopting a Mediterranean diet, but also the fact that obesity prevalence is lower in these countries. 31

4.1. Limitations and strengths

The main limitation of this study is that subgroups more likely to participate in online surveys may have been overrepresented. However, the study was weighted with respect to the age‐gender distribution of a population with NAFLD/NASH in the US from 1988–1994, 16 which were the only available data. This allowed for better accounting for under‐representation of specific groups by country and performing of inter‐country comparisons. Moreover, owing to the cross‐sectional nature of the study, we cannot infer causality from the associations found. However, they provide interesting indications about the importance of communicating about liver fibrosis stage, in particular, for people with obesity who were those who knew less about their fibrosis stage. This may be because communication with them is centred on weight and weight loss and not on liver health.

The main strengths of the study include its multi‐country context, which allowed us to have individuals followed in healthcare systems with different degrees of organisation and preparedness to manage NAFLD/NASH. 30 This survey also includes patients who are not easily recruited for hospital‐based studies and who may contribute to estimate better the association which would have been underestimated in hospital‐based studies, where those lost to follow‐up cannot be surveyed. Furthermore, the online survey ensured that participants with NAFLD/NASH could express their knowledge and perceptions freely, without any taboo or judgement from medical staff.

5. CONCLUSIONS

There is a sequential link between improving patient–provider communication about liver fibrosis stage and liver disease progression as greater patient awareness may facilitate better adherence to lifestyle changes, ultimately leading to better liver health. As the assessment of liver fibrosis is becoming the central assessment for predicting NAFLD disease progression to advanced stages, patient knowledge of their fibrosis stage should become a priority to improve liver health. Despite the seriousness of NASH‐related morbidity and mortality, patient–provider communication—especially for people with obesity—about fibrosis stage, its associated risks and how to reverse them, needs to improve as better patient knowledge means better adherence to treatment and enhanced liver and general health. Training for healthcare professionals and promoting patient educational programmes to support behavioural changes to prevent NAFLD progression are further interventions which should be urgently included in the international clinical and public health agendas.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

P. C. acknowledges research grants from MSD, outside the submitted work and Intercept Pharmaceuticals for the submitted work. A. T. is a current employee of Intercept Pharmaceuticals. J. L. C. acknowledges advisory and speaker fees from Gilead Sciences and AbbVie, and grants from Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. J. V. L. acknowledges grants and speaker fees from Gilead Sciences and MSD and speaker fees from AbbVie, Genfit and Intercept, outside the submitted work. A. M., F. M. and C. P. have nothing to disclose.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Patients involved in this study were informed when they registered on the Carenity platform that they consented expressly and specifically to the collection, handling and storing of their personal and health data. They were also informed of the purposes of the study and gave their explicit consent to the processing of their data before starting the survey, which was completely anonymous. Thus, submission to an ethical committee was not required.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Patients involved in this study were informed when they registered on the Carenity platform that they consented expressly and specifically to the collection, handling and storing of their personal and health data. They were also informed of the purposes of the study and gave their explicit consent to the processing of their data before starting the survey, which was completely anonymous.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J. V. L. acknowledges support to ISGlobal from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the ‘Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019‐2023’ Programme (CEX2018‐000806‐S) and from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Programme.

Carrieri P, Mourad A, Marcellin F, et al. Knowledge of liver fibrosis stage among adults with NAFLD/NASH improves adherence to lifestyle changes. Liver Int. 2022;42:984–994. doi: 10.1111/liv.15209

Handling Editor: Luca Valenti

Funding InformationThis study was funded in full by Intercept.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data, analytic methods and study material are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lazarus JV, Mark HE, Anstee QM, et al. Advancing the global public health agenda for NAFLD: a consensus statement. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(1):60‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zelber‐Sagi S, Lotan R, Shlomai A, et al. Predictors for incidence and remission of NAFLD in the general population during a seven‐year prospective follow‐up. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1145‐1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Association for the Study of the L, European Association for the Study of D, European Association for the Study of O . EASL‐EASD‐EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388‐1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neuschwander‐Tetri BA. Therapeutic landscape for NAFLD in 2020. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1984‐1998.e1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cicero AFG, Colletti A, Bellentani S. Nutraceutical approach to non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): the available clinical evidence. Nutrients. 2018;10(9), 1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shabalala SC, Dludla PV, Mabasa L, et al. The effect of adiponectin in the pathogenesis of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the potential role of polyphenols in the modulation of adiponectin signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anty R, Marjoux S, Iannelli A, et al. Regular coffee but not espresso drinking is protective against fibrosis in a cohort mainly composed of morbidly obese European women with NAFLD undergoing bariatric surgery. J Hepatol. 2012;57(5):1090‐1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bambha K, Wilson LA, Unalp A, et al. Coffee consumption in NAFLD patients with lower insulin resistance is associated with lower risk of severe fibrosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(8):1250‐1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hossain N, Kanwar P, Mohanty SR. A comprehensive updated review of pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical treatment for NAFLD. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7109270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Romero‐Gomez M, Zelber‐Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol. 2017;67(4):829‐846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hallsworth K, Adams LA. Lifestyle modification in NAFLD/NASH: facts and figures. JHEP Rep. 2019;1(6):468‐479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, et al. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):138‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wessels DH, Rosenberg Z. Awareness of non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis and treatment guidelines: what are physicians telling us? World J Hepatol. 2021;13(2):233‐241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flint SW, Oliver EJ, Copeland RJ. Editorial: obesity stigma in healthcare: impacts on policy, practice, and patients. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubino F, Puhl RM, Cummings DE, et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):485‐497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lazo M, Hernaez R, Eberhardt MS, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(1):38‐45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tacke F, Weiskirchen R. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)‐related liver fibrosis: mechanisms, treatment and prevention. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(8):729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy‐proven NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1265‐1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wong VW, Adams LA, de Ledinghen V, Wong GL, Sookoian S. Noninvasive biomarkers in NAFLD and NASH ‐ current progress and future promise. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(8):461‐478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Francque SM, Marchesini G, Kautz A, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a patient guideline. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lazarus JV, Anstee QM, Hagstrom H, et al. Defining comprehensive models of care for NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:717‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ritten A, LaManna J. Unmet needs in obesity management: from guidelines to clinic. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(S1):S30‐S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leey J, Cusi K. Editorial: diabetes, obesity and clinical inertia‐the recipe for advanced NASH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(8):1220‐1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E. Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective association between obesity and physiological dysregulation: evidence from a population‐based cohort. Psychol Sci. 2019;30(7):1030‐1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fillingham A, Peters S, Chisholm A, Hart J. Early training in tackling patient obesity: a systematic review of nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(3):396‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rogge MM, Merrill E. Obesity education for nurse practitioners: perspectives from nurse practitioner faculty. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25(6):320‐328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ockene JK, Ashe K, Peterson KS, Fitzgibbon M, Buscemi J, Dulin A. Society of Behavioral Medicine Call to action: include obesity/overweight management education in health professional curricula and provide coverage for behavior‐based treatments of obesity/overweight most commonly provided by psychologists, dieticians, counselors, and other health care professionals and include such providers on all multidisciplinary teams treating patients who have overweight or obesity. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(2):653‐655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burgess E, Hassmen P, Pumpa KL. Determinants of adherence to lifestyle intervention in adults with obesity: a systematic review. Clin Obes. 2017;7(3):123‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, Gorin AA, Suh YJ. Missing the target: including perspectives of women with overweight and obesity to inform stigma‐reduction strategies. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3(1):25‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lazarus JV, Palayew A, Carrieri P, et al. European 'NAFLD preparedness Index' ‐ is Europe ready to meet the challenge of fatty liver disease? JHEP Rep. 2021;3(2):100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data, analytic methods and study material are available from the corresponding author upon request.