Abstract

For genetic identification of Aspergillus Section Flavi isolates and detection of intraspecific variation, we developed a novel method for heteroduplex panel analysis (HPA) utilizing fragments of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) of the rRNA gene that was PCR amplified with universal primers. The method involves formation of heteroduplexes with a set of reference fragments amplified from Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, A. tamarii, and A. nomius and subsequent minislab vinyl polymer gel electrophoresis. The test panel is compared with species-specific standard panels (F-1, P-1, T-1, and N-1) generated by pairwise reannealing among four reference fragments. Of 90 test panels, 89 succeeded in identifying the species and 74 were identical to one of the four standard panels. Of the 16 new panels, 11 A. flavus/A. oryzae panels were identical and typed as F-2 and 4 of 5 A. nomius panels were typed as N-2 or N-3. The other strain, A. nomius IMI 358749, was unable to identify the species because no single bands were formed with any of the four reference strains. DNA sequencing revealed that our HPA method has the highest sensitivity available and is able to detect as little as one nucleotide of diversity within the species. When Penicillium or non-Section Flavi Aspergillus was subjected to HPA, the resulting bands of heteroduplexes showed apparently lower mobility and poor heteroduplex formation. This indicates that HPA is a useful identification method without morphological observation and is suitable for rapid and inexpensive screening of large numbers of isolates. The HPA typing coincided with the taxonomy of Section Flavi and is therefore applicable as an alternative to the conventional methods (Samson, R. A., E. S. Hoekstra, J. C. Frisvad, and O. Filtenborg, p. 64–97, in Introduction to Food- and Airborne Fungi, 6th ed., 2000).

Aspergillus Section Flavi has attracted worldwide attention for economic and public health reasons because of its industrial use and toxigenic potential. This Section consists of two groups of species; one includes Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius, all of which produce aflatoxin and cause serious problems worldwide in agricultural commodities (4). The other group includes the non-aflatoxin-producing species A. oryzae, A. sojae, and A. tamarii, which have been used for production of traditional fermented foods in Asia. Identification of the species has relied mainly upon the morphological characters used as taxonomic criteria (23). It is, however, difficult to identify Section Flavi species because of morphological divergence among isolates of the same species (15).

Recently, molecular genetic techniques have been used as tools with which to study the phylogeny and classification of Aspergillus Section Flavi. Egel et al. (6) reported that restriction enzyme analysis of a Taka-amylase A gene can divide the species of Section Flavi into several groups and detect intraspecific variations within A. nomius, A. tamarii, and A. flavus strains. On the basis of the sequence data of several protein-coding genes, Geiser et al. (10) failed to find any evidence that A. flavus and A. oryzae are independent species and suggested that A. oryzae has evolved by domestication from A. flavus. Other genetic attempts, by using Southern hybridization analyses, have been made to classify the Section Flavi strains with other genes as targets, such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms of nuclear and mitochondrial DNAs (21, 22), and sequence divergence of aflR genes involved in the aflatoxin pathway (3). The above-described methods have all provided useful information on the phylogenetic relationships among species of Aspergillus Section Flavi. However, there may be disadvantages in these genetic techniques in that they are time-consuming and complicated due to nucleotide sequencing, the emergence of many bands, isotope use, and cumbersome preparation of DNA.

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions ITS1 and ITS2, which evolve relatively faster than the coding regions of the rRNA gene, are present in tandemly repeated units and easily isolated by PCR amplification (12). Hence, such characters are useful for the classification of closely related organisms (9, 11, 24, 25). By using ITS regions (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2), we previously found that single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis assisted in the morphological identification of Section Flavi strains (17). This analysis effectively differentiates the species of Section Flavi but is applicable to only the strains of Section Flavi for the following reasons. The PCR products amplified with general primers are not section specific; the mobility of single-stranded DNA cannot be estimated because DNA mobility in gel is dependent on its secondary structure and its interaction with the gel matrix. Since the specificity is limited, some other fungi might show mobility indistinguishable from that of Section Flavi species.

Heteroduplex analysis allows genetic screening of unknown DNA fragments in a sequence-dependent manner. Briefly, similar but not identical DNA fragments obtained form heteroduplexes by their denaturation and reannealing. Unpaired and mismatched nucleotides affect the DNA structure and lower the electrophoretic mobility of the heteroduplexes by sequence divergence (5). This analytical method has been used in medical genetics (8) and to clarify the evolution of organisms including viruses (5, 16) and bacteria (19).

The purpose of the present study was to establish heteroduplex analysis for not only routine identification of Aspergillus Section Flavi species without using morphological techniques but also sensitive detection of genetic diversity within species. By forming interspecific heteroduplexes, heteroduplex panel analysis (HPA) markedly improved the discriminating power of sequence variability to as little as 1 bp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

A total of 94 Aspergillus Section Flavi strains, including 30 A. flavus, 13 A. oryzae, 16 A. parasiticus, 14 A. sojae, 10 A. tamarii, and 11 A. nomius strains, were used in this study. The origins, designations, and aflatoxin production of 68 of the 94 strains were described previously (17), and only the strain names are listed in Table 1. The 28 additional Section Flavi strains, 12 non-Section Flavi strains, and 5 Penicillim strains used are listed in Table 2. All strains were maintained on potato dextrose agar slants.

TABLE 1.

Aspergillus Section Flavi strains used in this study

| Species | Straina |

|---|---|

| A. flavus | P-39-1R, S-21, A0518, HIC 6044, S-281, RIB 1427T (NRRL 1957), RIB 1403 (ATCC 9643), RIB 4007 (NRRL A-4018b), RIB 1406 (IFO 7600), RIB 1407 (IFO 8558), RIB 1410, ATCC 28539, ATCC 28543 |

| A. oryzae | OPS 14, HIC 6154, OPS 21, IFO 30113 (ATCC 22788), IFO 30104 (ATCC 22786), IFO 5375T (ATCC 4814, Thom no. 113), IFO 30102, IFO 30103 (ATCC 22787), RIB 1038 (NRRL 506), RIB 1029 (IFO 5239), RIB 1120 (IFO 5388), RIB 1039 (ATCC 16870), RIB 40 (ATCC 42149) |

| A. parasiticus | P-12-2, P-35-3, A0544, A0515, A0524, A0540, IFO 4082, RIB 1037 (NRRL 465), RIB 4033 (IFO 4301), RIB 4002 (ATCC 22789), RIB 4003 (NRRL 2999), ATCC 15517R, ATCC 26692 |

| A. sojae | IFO 4200 (ATCC 20245), IFO 5241, IFO 30112, IFO 4403, IFO 4391 (ATCC 11906), IFO 32074, RIB 410, RIB 1044 (ATCC 42250), RIB 934, RIB 1023, RIB 1040, RIB 1042 (ATCC 42249), RIB 1045T (ATCC 42251), RIB 1059 (IFO 4204) |

| A. tamarii | IFO 7465, A0754R, S-65-1, HIC 6212, SP-27-3, SP-27-4, S-33-1, A0757, RIB 3006 |

| A. nomius | ATCC 15546R, T (NRRL 13137), NRRL 6552, IMI 358750, IMI 358749, IMI 358751, IMI 358752 |

Abbreviations: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; IFO, Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, Japan; S, P, and SP, National Institute of Health Sciences, Japan; HIC, Hatano Reseach Institute, Food and Drug Safety Center, Japan; A, Public Health Institute of Kobe City; OPS, Osaka Prefectural Institute of Public Health; RIB, National Research Institute of Brewing, Tax Administration Agency, Japan; NRRL, Culture Collection of the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research; IMI, International Mycological Institute. Superscripts: R, reference strain; T, type culture or representative strain.

TABLE 2.

Aspergillus Section Flavi and the other isolates used in this study

| Straina | Geographical origin | Source | Aflatoxin productionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. flavus OPS 374 | Japan (Okinawa) | Sugar field soil | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 375 | Vietnam | Sugar stem | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 398 | Japan (Okinawa) | Sugar field air | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 399 | Thailand | Sugar field soil | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 400 | Thailand | Sugar field soil | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 402 | Vietnam | Sugar field soil | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 405 | Thailand | Rice | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 406 | Vietnam | Rice | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 407 | Vietnam | Rice | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 408 | Vietnam | Peanuts | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 410 | Vietnam | Coffee | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 411 | Vietnam | Coffee | − |

| A. flavus OPS 412 | Vietnam | Coffee | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 419 | Thailand | Rice | NTc |

| A. flavus OPS 421 | Thailand | Peanuts | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 422 | Thailand | Peanuts | + (B) |

| A. flavus OPS 423 | Vietnam | Peanuts | + (B) |

| A. parasiticus OPS 393 | Vietnam | Peanuts | + (B, G) |

| A. parasiticus OPS 394 | Vietnam | Peanuts | + (B, G) |

| A. parasiticus OPS 417 | Vietnam | Peanuts | + (B, G) |

| A. tamarii RIB3005 (NRRL429)T | China | Soy sauce | − |

| A. nomius OPS 372 | Vietnam | Sugar stem | + (B, G) |

| A. nomius OPS 387 | Japan (Okinawa) | Sugar stem | + (B, G) |

| A. nomius OPS 401 | Vietnam | Sugar field soil | + (B, G) |

| A. nomius NRRL 25393 | Japan (Okinawa) | Soil | + (B, G) |

| A. nomius OPS 420 | Vietnam | Rice | NT |

| A. niger IFO 8541 (NRRL3122) | Unknown | Unknown | |

| A. niger OPS 56 | Japan | Tea leaves | |

| A. niger OPS 86 | Japan | Orange juice | |

| A. fumigatus IFO 4400 | Japan | Soil | |

| A. fumigatus OPS 43 | Japan | Air | |

| A. nidulans OPS 17 | Japan | Soil | |

| A. clavatus OPS 53 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| A. ostianus IFO 4081 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| A. versicolor OPS 51 | Philippines | Soybean lees | |

| A. terreus OPS 46 | Japan | Soil | |

| A. candidus OPS 2 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| A. ochraceus OPS63 | Brazil | Coffee | |

| P. expansum IFO 8800 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| P. cyclopium IFO 7225 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| P. roqueforti OPS 16 | France | Cheese | |

| P. digitatum OPS 85 | Japan | Orange | |

| P. frequentans OPS114 | Japan | Yogurt |

For definitions of the abbreviations used, refer to the footnote to Table 1.

Symbols: +, positive; −, negative. The aflatoxin type(s) produced is in parentheses.

NT, not tested.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification analysis were performed as described previously (17). PCR conditions were slightly modified. After addition of 7% dimethyl sulfoxide to a reaction mixture (25 μl), PCR amplification was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (model 2400; Perkin-Elmer Cetus Corp., Norwalk, Conn.) under the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 7 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 40°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR amplification achieved higher yields by addition of 7% dimethyl sulfoxide to the reaction mixture.

HPA.

Reference fragments for HPA were prepared by PCR amplification of the ITS regions of four strains: A. flavus P 39-1, A. parasiticus IFO 4082, A. tamarii A0754, and A. nomius ATCC 15546. All strains were previously characterized by PCR-SSCP analysis (17). Three microliters of the tested fragments, amplified from a total of 108 strains used, was mixed with an equal volume of each reference fragment and 1 μl of gel loading buffer (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine). To form heteroduplex molecules, the mixtures were denatured at 94°C for 5 min, followed by slow cooling to 20°C for 10 min in a model PJ2000 DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus Corp.). The resulting heteroduplexes were applied to a hydrolink mutation detection enhancement (MDE) gel (FMC BioProducts) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Electrophoresis was performed in 0.6× TBE buffer (53.4 mM Tris-acetate and 1.2 mM EDTA) at 300 V for 2.5 h at a constant temperature of 20°C in a minislab gel apparatus (gel size, 90 by 80 by 0.75 mm; AE-6410; ATTO, Co., Tokyo, Japan). The gels stained with ethidium bromide were scanned with a video capture apparatus (AE 6915, Printgraph; ATTO, Co.), and then images (NIH image, version 1.62; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/) were stored on a Macintosh computer.

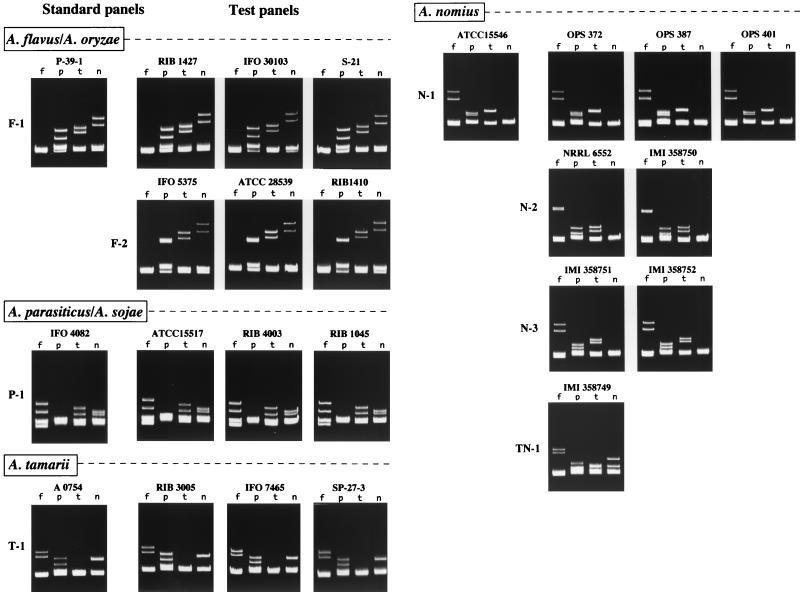

Standard panels of F-1, P-1, T-1, and N-1 (see Fig. 1) were made up with combinations of six characteristic banding patterns of the heteroduplexes, which were generated by pairwise reannealing among four reference fragments and subsequent MDE gel electrophoresis. Each species-specific panel also contained a homoduplex band generated from the reference fragment itself. The standard panel images were stored on a computer and compared with the panels tested in this study.

FIG. 1.

HPA panels of Aspergillus Section Flavi strains obtained by using ITS-region DNAs amplified by PCR. The left panels of reference strains P-39-1, IFO4082, A0754, and ATCC 15546 are the standard panels of F-1, P-1, T-1, and N-1, respectively. On the right are the test panels of 20 strains that are indicated above the panels. F-2, N-2, N-3, and TN-1 are additional new panels of heteroduplex types. Heteroduplex bands in lanes f, p, t, and n were formed with reference strains of A. flavus, A. parasiticus, A. tamarii, and A. nomius, respectively.

Nucleotide sequencing.

After digestion of the amplified DNA (approximately 600 bp) with EcoRI, the resulting two fragments (approximately 300 bp) treated with a DNA-blunting kit (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) were ligated into the HincII and EcoRI sites of the pUC18 vector. The ligated DNA was transformed into Escherichia coli XL1 Blue. DNA double digested with EcoRI and PstI was electrophoresed on agarose gel to confirm that the cloned inserts were approximately 300 bp. At least three clones containing each digested fragment were selected based on the presence or absence of the EcoO109I site, which was identified by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, as reported previously (17). The selected clones were purified with Q Sepharose fast flow (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Uppsala, Sweden). Double-stranded sequencing of each clone was performed with an ALF autoread sequencer (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology) by using an autoread sequencing kit (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology). Sequence information was used only when two or more independent clones showed the same sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The DNA sequence data obtained in this study were aligned with the Clustal W program, version 1.6 (13), followed by manual adjustment. The PHYLIP 3.5 package (7) was used for phylogenetic analysis. A distance matrix was generated by the two-parameter method of Kimura (14) in the DNADIST program. Phylogenetic trees were then constructed by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (NEIGHBOR program) and the maximum-likelihood (ML) method (DNAML program). SEQBOOT was used to generate 100 bootstrapped data sets.

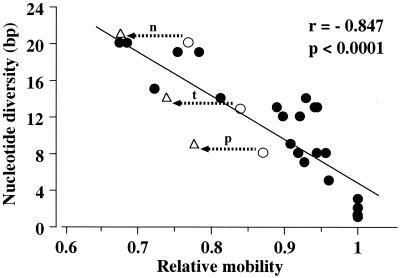

The relative mobilities of heteroduplexes were calculated as the average distance of migration of the two heteroduplex bands divided by that of the homoduplex bands. The values were then plotted against nucleotide diversity (base pairs) between heteroduplex types of ITS regions, which were calculated based on sequence alignments by counting gaps. The reduction value was the difference in relative mobility relative to the nucleotide diversity.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequence data of 10 strains reported in the present study have been submitted to the DDBJ database and assigned accession no. D84353 to D84358 and AB000533 to AB000536, inclusive.

RESULTS

Identification by HPA panels.

Of 42 HPA panels that were generated from 29 A. flavus and 13 A. oryzae strains of various origins, 31 panels (20 of A. flavus and 11 of A. oryzae) matched the F-1 standard panel, while the other strains showed a new HPA pattern. The panels of nine A. flavus strains (RIB 1410, ATCC 28539, OPS 375, OPS 398, OPS 402, OPS 406, OPS 421, OPS 422, and OPS 423) and two A. oryzae strains (IFO 5375 and RIB 1039) showed identical HPA patterns and were designated type F-2. Strains of type F-2 formed a single band with the reference strain of A. flavus (lanes f in panel F-2 of Fig. 1), as did those of type F-1. In pairing with other reference strains, however, strains of type F-2 displayed heteroduplex bands with apparently lower mobility than those of strains of type F-1 (Fig. 1). An additional character used to discriminate type F-2 from type F-1 was the formation of overlapping heteroduplex bands with the A. parasiticus reference strain (lanes p in panel F-2 of Fig. 1). The panels of all 15 A. parasiticus and 14 A. sojae strains matched the P-1 standard panel. All nine panels of A. tamarii strains also matched the T-1 standard panel. Of the 10 HPA panels of A. nomius strains, 5 matched the N-1 standard panel while the other strains yielded 3 different panels (N-2, N-3, and TN-1 in Fig. 1). The new panels of NRRL 6552 and IMI 358751 (designated N-2 and N-3, respectively) were identical to those of IMI 358750 and IMI 358752, respectively. These two types were differentiated from type N-1 in that types N-1 and N-2 showed overlapping heteroduplex bands in lanes t and f, respectively. Type N-3 showed two distinct heteroduplex bands in lanes f, p, and t. Despite the variability shown in A. nomius HPA panels, all nine strains but IMI 358749 (TN-4 type) formed a single band with the reference strain of A. nomius. One strain, IMI 358749, displayed unique HPA panels designated type TN-1. IMI 358749 formed heteroduplex bands with mobility shifts even when reannealed with the other A. nomius strains (data not shown).

In short, 93 of the 94 Aspergillus Section Flavi strains, including four reference strains, were identified by HPA as the corresponding species named by morphological and physiological identification. Only IMI 358749 was unidentifiable, since no single bands were formed with the four reference strains.

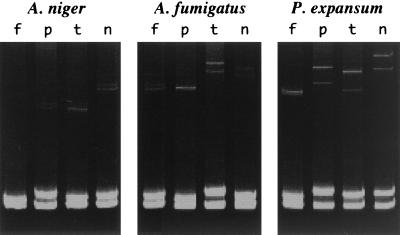

When 12 strains of non-Section Flavi Aspergillus species were subjected to HPA, heteroduplex bands were shown on an MDE gel but their electrophoretic mobilities were apparently lower than those of the heteroduplexes formed between two of the Section Flavi strains (Fig. 2). Similar findings were obtained with the five strains of Penicillium examined (Fig. 2). The heteroduplex banding patterns of HPA panels were highly reproducible under the present conditions.

FIG. 2.

HPA panels of A. niger IFO 8340, A. fumigatus OPS 43, and Penicillium expansum IFO 8800 obtained by using ITS region DNAs amplified by PCR. Heteroduplex bands in lanes f, p, t, and n were formed with reference strains of A. flavus, A. parasiticus, A. tamarii, and A. nomius, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

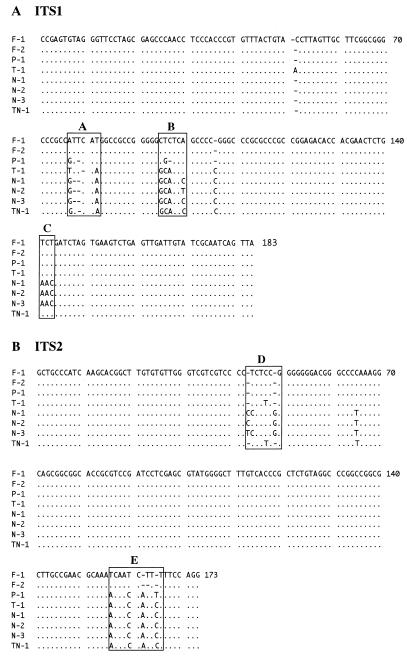

To verify the findings of HPA analysis, the PCR products sequenced from 24 strains were as follows: four references used in this study and an additional 13 strains of standard types, A. flavus strains of type F-1 (RIB 1427 and S-21), A. oryzae strains of type F-1 (IFO 30113 and HIC 6154), A. parasiticus strains of type P-1 (P-12-2 and IFO 4082), A. sojae strains of type P-1 (IFO 4200 and IFO 5241), A. tamarii strains of type T-1 (RIB 3005 and SP-27-3), A. nomius strains of type N-1 (OPS 372, OPS 387, and OPS 401); seven strains of new types identified by HPA, A. oryzae IFO 5375 (type F-2), A. flavus ATCC 28539 (type F-2), and A. nomius strains of type N-2 (NRRL 6552 and IMI 358750), of type N-3 (IMI 358751 and IMI 358752), and of type TN-1 (IMI 358749). The ITS regions amplified by PCR ranged from 594 to 598 bp. The nucleotide sequences of ITS1 (Fig. 3A) and ITS2 (Fig. 3B) were aligned for comparison with A. flavus P-39-1 (type F-1). The coding regions, the 3′ end of the 18S genes (11 bp), the 5.8S genes (157 bp), and the 5′ end of the 28S genes (38 bp), were identical among all of the strains examined (data not shown). ITS1 and ITS2 sequences of A. flavus strains of type F-1 and A. parasiticus strains of type P-1 were all identical to those of A. oryzae strains of type F-1 and A. sojae strains of type P-1, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence alignments for ITS1 (A) and ITS2 (B) of rRNA genes from Aspergillus Section Flavi strains. F-1, A. flavus P-39-1; F-2, A. oryzae IFO 5375; P-1, A. parasiticus IFO 4082; T-1, A. tamarii A0754; N-1, A. nomius ATCC 15546; N-2, A. nomius NRRL 6552; N-3, A. nomius IMI 358751; TN-1, A. nomius IMI 358749. Dots indicate identity to the sequence of F-1. Dashes indicate alignment gaps (insertion or deletion differences). Boxes A to E indicate variable regions.

Most sequence differences were located together in the ITS1 and ITS2 genes, as shown in five places indicated with boxes in Fig. 3. These sequences were found to possess several gaps in addition to substitutions. Type F-2 differed from type F-1 by only a single gap at position 163 in box E, whereas types N-2 and N-3 differed from N-1 by only two nucleotide substitutions and one nucleotide substitution, respectively, at position 100 in box B and at positions 43 and 44 in box D. Type TN-1 was revealed to be more analogous to type T-1 in sequences in boxes C and D than to types N-1, N-2, and N-3.

Sequence diversity and relative mobilities of heteroduplex bands.

The ITS regions of eight types had interspecific diversities ranging from 5 to 21 bp (Table 3), which were detected as mobility shifts of heteroduplex bands on an MDE gel (Fig. 1). Intraspecific diversity was shown in A. nomius (1 to 8 bp) and A. flavus/A. oryzae (only 1 bp) but not in A. parasiticus/A. sojae or A. tamarii. Type TN-1 A. nomius had the highest intraspecific diversity (8 bp) and the lowest interspecific diversity from A. tamarii (5 bp). Except for type TN-1, intraspecific diversity (1 to 3 bp) did not display any heteroduplex bands with mobility shifts (lane f of F-2 and lanes n of N-2 to N-3 in Fig. 1), while other interspecific heteroduplexes (lanes p, t, and n of F-2 and lanes f, p, and t of N-2 and N-3 in Fig. 1) displayed mobility shifts apparently different from those of the corresponding standard panels.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide diversity of ITS regions among Aspergillus Sect. Flavi strainsa

| Typea | Nucleotide diversity (no. of bases) from:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-1 (595)b | F-2 (594) | P-1 (595) | T-1 (598) | N-1 (598) | N-2 (598) | N-3 (598) | TN-1 (597) | |

| F-1 | 0 | |||||||

| F-2 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| P-1 | 8 | 9 | 0 | |||||

| T-1 | 13 | 14 | 9 | 0 | ||||

| N-1 | 20 | 21 | 14 | 13 | 0 | |||

| N-2 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 2 | 0 | ||

| N-3 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| TN-1 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 0 |

F-1, A. flavus P-39-1 and A. oryzae IFO 30113; F-2, A. oryzae IFO 5375; P-1, A. parasiticus IFO 4082 and A. sojae IFO 4200; T-1, A. tamarii A0754; N-1, A. nomius ATCC 15546; N-2, A. nomius NRRL 6552; N-3, A. nomius IMI 358751; TN-1, A. nomius IMI 358749.

The numbers within parentheses indicate the sizes (base pairs) of ITS region DNAs amplified by PCR.

The relative mobilities of all of the heteroduplex bands formed among the eight types of strain were plotted against nucleotide diversity, and then the best-fit curve was drawn (Fig. 4) by using a linear equation. The correlation coefficient for the linear regression of the heteroduplex relative mobility against the nucleotide diversity was 0.847 with a significance level (P value) of <0.0001. In spite of the general correlation, the mobility shift distance was not absolutely proportional to the nucleotide diversity number. A drastic reduction in relative mobility was observed in interspecific heteroduplexes, as shown between the F-1 and F-2 panels in Fig. 1. The reduction values between lanes p, t, or n were very high, 0.09 (arrow p), 0.10 (arrow t), and 0.09 (arrow n), respectively (Fig. 4). A smaller mobility shift of interspecific heteroduplexes was observed between panels N-1 and N-2 or N-3, and their reduction values ranged from 0.01 to 0.03.

FIG. 4.

Relative mobilities of heteroduplexes and pairwise nucleotide diversity of ITS regions among the eight heteroduplex types shown in Table 2. They were calculated as the average distance of migration of the two heteroduplex bands divided by the distance of migration of the homoduplex bands. The values were then plotted against nucleotide diversity. Differences in relative mobility shown in Fig. 1 between F-1 (○) and F-2 (▵) are indicated by the arrows: p, A. parasiticus; t, A. tamarii; n, A. nomius.

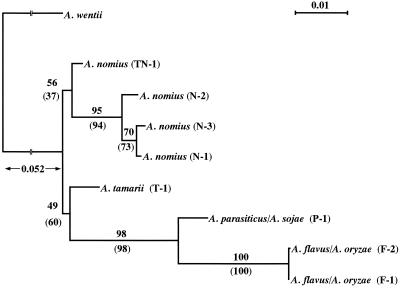

Phylogenetic analysis.

From the data on the ITS1 and ITS2 sequences from the six species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by the NJ or ML method to show the genetic relationships among Aspergillus Section Flavi species. The sequence data of ITS1 and ITS2 from A. wentii (EMBL database accession no. U03522 and U03523, respectively) served as an outgroup. The rooted NJ tree (Fig. 5) was topologically identical to the ML tree (data not shown) in major respects. Bootstrap analysis strongly supported an A. flavus/A. oryzae–A. parasiticus/A. sojae clade (NJ, 98%; ML, 98%), an A. flavus/A. oryzae clade (NJ, 100%; ML, 100%), and an A. nomius clade, except for type TN-1 (NJ, 95%; ML, 94%). The A. tamarii–A. flavus/A. oryzae–A. parasiticus/A. sojae and A. nomius type TN-1-A. nomius type N-1 to N-3 clades had low bootstrap values in NJ and ML trees. When IMI 358749 (type TN-1) was excluded from the analysis, the bootstrap support for the A. tamarii–A. flavus/A. oryzae–A. parasiticus/A. sojae clade increased from 60 to 83% in the ML tree but not in the NJ tree. In order of genetic proximity to A. flavus, A. parasiticus was most closely related, followed by A. tamarii and finally A. nomius.

FIG. 5.

NJ phylogenetic analysis of eight heteroduplex types of Aspergillus Section Flavi based on an ITS region nucleotide sequence comparison. Codes in parentheses correspond to those presented in Fig. 3. Numbers indicate bootstrap frequencies (percent) based on NEIGHBOR and DNAML analyses (in parentheses), respectively. The bootstrap value of 60% was increased to 83% when IMI 358749 (type TN-1) was excluded from the ML analysis. The scale indicates 1.0% divergence.

DISCUSSION

The HPA presented herein is a novel system that enables accurate identification of the species of Aspergillus Section Flavi and subdivision based on highly sensitive discrimination of sequence variability. Gaps lead to the formation of a bulge in the heteroduplex, bend the DNA axis, and affect the mobility shift much more than do simple substitutions (bubble) (2). However, none of the intraspecific heteroduplexes that contained even a gap or two substitutions displayed any mobility shift under the present HPA conditions in a minislab MDE gel with a shorter distance (ca. 8 cm). These disadvantageous conditions contributed to identification of the strains to the species level. The formation of interspecific heteroduplexes between strains of different species significantly improved the ability of HPA to detect a single-base substitution or a single-base gap. The highest sensitivity must have been due to the bulge in heteroduplexes resulting from the gap variation in ITS sequences because of the regions not coding proteins. For example, F-1 and F-2 interspecific heteroduplexes formed with P-1 had a marked difference in mobility shifts, although the sequence difference between F-1 and F-2 was only a single-base (T) gap. This can be explained by the increase in bulge size, 2 bp (AT) to 3 bp (ATT), by only one additional gap. It has been suggested that the magnitude of DNA bending depends on the bulge size (2, 20), and the ATT bulge disrupted the flanking of TA and GC base pairs and affected the AC bubble near the bulge (1). From these presumptions, the conformational change of DNA in the heteroduplexes formed between P-1 and F-2 was much greater than that between P-1 and F-1. This might explain the easy detection of the 1-bp diversity between types F-1 and F-2. One- or two-bp diversity among A. nomius types was detected by smaller mobility shifts of interspecific heteroduplexes. In such cases as the interspecific heteroduplexes formed with type T-1, interspecific heteroduplexes of N-1, N-2, and N-3 were discriminated from one another, although each intraspecific heteroduplex was not. The largest difference between inter- and intraspecific heteroduplexes was the presence in the former of a larger number of concurrent mismatches containing bubbles and bulges at common positions in the ITS regions. This suggests that such mismatches act as a cofactor to enhance minor conformational differences among three heteroduplexes introduced by base effects of the bulge and the bubble.

Two heteroduplex types, F-1 and F-2, created by HPA were common in the A. flavus and A. oryzae strains tested, and thus, there was no association with aflatoxin production. Such intraspecific diversity and the conspecificity found in A. parasiticus and A. sojae were confirmed by subsequent nucleotide sequencing. Early genetic approaches (6, 10) with several protein-coding genes as targets have failed to identify substantial interspecific diversity between A. flavus and A. oryzae. These genetic findings have therefore provided no justification for maintaining the industrial fungi A. oryzae and A. sojae as individual species even if there are subtle morphological differences (15). If the industry requires discrimination of each pair, additional tests, such as random amplification of polymorphic DNA (26), will have to be done.

Greater intraspecific diversity of A. nomius, 1 to 3 bp, was accurately detected by HPA, and it created three heteroduplex types in the 10 strains of A. nomius, except IMI35849, examined in the present study. The diversity is also evident in Taka amylase A gene analysis (6), by which seven of the A. nomius strains, except IMI35849, were divided into three groups. These findings were in agreement with the DNA complementarity studies of Kurtzman et al. (18), who found relatively lower homology within A. nomius strains (85 to 100%).

IMI 35849 (type TN-1), which HPA failed to identify, also showed an unusual SSCP pattern and morphological atypicalness (4), as reported previously (17). The heteroduplexes formed with A. tamarii displayed the fastest migration bands (relative mobility, 0.96). Such a high value indicated a closer relationship between the two strains, since the relative mobilities detected in the present study were correlated with nucleotide diversity (Fig. 4). Such information was consistent with the phylogenetic tree illustrated in Fig. 5, in which IMI 358749 was most closely related to A. tamarii and formed an independent clade separated from that of the A. nomius group (95 or 94% bootstrap support). Based on these genetic and morphological characters, it is suggested that IMI 358749 is an intermediate strain between A. tamarii and A. nomius.

Cross-genus or -species formation of heteroduplexes was observed in HPA of Penicillium and non-Section Flavi Aspergillus strains. Such fungi, however, could easily be identified as a species different from Aspergillus Section Flavi (relative mobility, 0.67 to 0.96) by their apparently lower mobility (relative mobility below 0.52) and poor formation of heteroduplex bands. This was due to the lower DNA homology of the ITS regions between the fungi tested and the Section Flavi strains that served as references and which indicates that our HPA is more specific to section Flavi than is the SSCP method (17). HPA also identified several industrial strains as A. oryzae or A. sojae that had lost the ability to form conidia because of repeated transfers for many years. The discriminating power of HPA suggests that it allows direct identification of the Section Flavi isolates without morphological observation. This may also be the case with nonliving fungi. It may also be possible to detect cryptic species in morphologically atypical isolates of Section Flavi.

ITS sequences are generally known to reflect phylogenetic relationships very well. Indeed, there were disagreements between the ITS-based phylogenetic relationships and traditional taxonomic arrangements in some fungi such as Fusarium (25), Trichoderma (11), and Trichophyton (24). The HPA typing of ITS regions we developed coincided well with the taxonomy of Section Flavi. In addition, the time to identification from a small amount of fungal mycelia could be 1 day, including DNA extraction, amplification, and electrophoresis, whereas morphological methods require at least a week for cultivation. HPA must therefore be applicable and practical as an alternative to the conventional method (23).

In conclusion, ITS1 and ITS2 genes contain sufficient interspecific and minimal intraspecific sequence diversity, allowing identification of the species of Aspergillus Section Flavi by HPA. This method is rapid and sensitive and requires minimal technological expertise, in contrast to conventional morphological methods. HPA typing also coincided well with the taxonomy of the Section Flavi and it must therefore be applicable as an alternative to the traditional method.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kosuke Takatori (National Institute of Health Sciences), Norihiro Toyazaki (Public Health Research Institute of Kobe City), Katuya Gomi and Osamu Yamada (National Research Institute of Brewing, Tax Administration Agency), and Hiroshi Fujikawa (Tokyo Metropolitan Research Laboratory of Public Health) for providing the strains of Aspergillus section Flavi. We also thank Peter J. Cotty (Southern Regional Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture), Masakatsu Ichinoe (Tokyo Kasei University), and Haruo Takahashi (Public Health Laboratory of Chiba Prefecture) for providing strains of A. nomius and for helpful comments. We especially thank Genji Sakaguchi (Osaka Prefecture University) for critical review and correction of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aboul-ela F, Murchie A I H, Homans S W, Lilley D M J. Nuclear magnetic resonance study of a deoxyoligonucleotide duplex containing a three base bulge. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:173–188. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya A, Lilley D M J. The contrasting structures of mismatched DNA sequences containing looped-out bases (bulges) and multiple mismatches (bubbles) Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6821–6839. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.17.6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang P-K, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Bennett J W. Sequence variability in homologs of the aflatoxin pathway gene aflR distinguishes species in Aspergillus Section Flavi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:40–43. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.40-43.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotty P J, Bayman P, Egel D S, Elias K S. Agriculture, aflatoxins and Aspergillus. In: Powell K A, Renwick A, Peberdy J F, editors. The genus Aspergillus: from taxonomy and genetics to industrial applications. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delwart E L, Shpaer E G, Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Grez M, Rübsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins J I. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay:analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egel D S, Cotty P J, Elias K S. Relationships among isolates of Aspergillus sect. flavi that vary in aflatoxin production. Phytopathology. 1994;84:906–912. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package) version 3.57c. Seattle: University of Washington; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguly A, Rock M J, Prockop D J. Conformation-sensitive gel electrophoresis for rapid detection of single-base differences in double-stranded PCR products and DNA fragments: evidence for solvent-induced bends in DNA heteroduplexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10325–10329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaskell G J, Carter D A, Britton W J, Tovey E R, Benyon F H L, Løvborg U. Analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions of ribosomal DNA in common airborne allergenic fungi. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1567–1569. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiser D M, Pitt J I, Taylor J W. Cryptic speciation and recombination in the aflatoxin-producing fungus Aspergillus flavus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:388–393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grondona I, Hermosa R, Tejada M, Gomis M D, Mateos P F, Bridge O D, Monte E, Garcia-Acha L. Physiological and biochemical characterization of Trichoderma harzianum, a biological control agent against soilborne fungal plant pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3189–3198. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3189-3198.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hibbett D S. Ribosomal RNA and fungal systematics. Trans Mycol Soc Jpn. 1992;33:533–556. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins D. Clustal W, version 1.6. Cambridge, United Kingdom: The Europian Bioinformatics Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klich M A, Pitt J I. Differentiation of Aspergillus flavus from A. parasiticus and other closely related species. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1988;91:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreis S, Whistler T. Rapid identification of measles virus strains by the heteroduplex mobility assay. Virus Res. 1997;47:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumeda Y, Asao T. Single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of PCR-amplified ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers to differentiate species of Aspergillus Section Flavi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2947–2952. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2947-2952.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtzman C P, Horn B W, Hesseltine C W. Aspergillus nomius, a new aflatoxin-producing species related to Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus tamarii. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1987;53:147–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00393843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leys E J, Smith J H, Lyons S R, Griffen A L. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains by heteroduplex analysis and detection of multiple strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3906–3911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3906-3911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilley D M. Kinking of DNA and RNA by base bulges. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7140–7142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moody S F, Tyler B M. Restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA of the Aspergillus flavus group: A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2441–2452. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2441-2452.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moody S F, Tyler B M. Use of nuclear DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms to analyze the diversity of the Aspergillus flavus group: A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2453–2461. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2453-2461.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson R A, Hoekstra E S, Frisvad J C, Filtenborg O, editors. Introduction to food- and airborne fungi. 6th ed. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; 2000. Identification of the common food- and airborne fungi, Aspergillus; pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Summerbell R C, Haugland R A, Li A, Gupta A K. rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 sequences of asexual, anthropophilic, dermatophytes related to Trichophyton rubrum. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4005–4011. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4005-4011.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waalwijk C, de Koning J R A, Baayen R P, Gams W. Discordant groupings of Fusarium spp. from sections Elegans, Liseola and Dlaminia based on ribosomal ITS1 and ITS2 sequences. Mycologia. 1996;88:361–368. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan G-F, Liu C-S, Chen C-C. Differentiation of Aspergillus parasiticus from Aspergillus sojae by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2384–2387. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2384-2387.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]