Abstract

We have identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2 a novel cluster of mobile genes encoding degradation of hydroxy- and halo-aromatic compounds. Nineteen open reading frames were located and, based on sequence similarities, were putatively identified as encoding a ring hydroxylating oxygenase (hybABCD), an ATP-binding cassette-type transporter, an extradiol ring-cleavage dioxygenase, transcriptional regulatory proteins, enzymes mediating chlorocatechol degradation, and transposition functions. Expression of hybABCD in Escherichia coli cells effected stoichiometric transformation of 2-hydroxybenzoate (salicylate) to 2,5-dihydroxybenzoate (gentisate). This activity was predicted from sequence similarity to functionally characterized genes, nagAaGHAb from Ralstonia sp. strain U2 (S. L. Fuenmayor, M. Wild, A. L. Boyes, and P. A. Williams, J. Bacteriol. 180:2522–2530, 1998), and is the second confirmed example of salicylate 5-hydroxylase activity effected by an oxygenase outside the flavoprotein group. Growth of strain JB2 or Pseudomonas huttiensis strain D1 (an organism that had acquired the 2-chlorobenzoate degradation phenotype from strain JB2) on benzoate yielded mutants that were unable to grow on salicylate or 2-chlorobenzoate and that had a deletion encompassing hybABCD and the region cloned downstream. The mutants' inability to grow on 2-chlorobenzoate suggested the loss of additional genes outside of, but contiguous with, the characterized region. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis revealed a plasmid of >300 kb in strain D1, but no plasmids were detected in strain JB2. Hybridization analyses confirmed that the entire 26-kb region characterized here was acquired by strain D1 from strain JB2 and was located in the chromosome of both organisms. Further studies to delineate the element's boundaries and functional characteristics could provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying evolution of bacterial genomes in general and of catabolic pathways for anthropogenic pollutants in particular.

Lateral gene transfer between bacteria can potentially affect a variety of processes in soil, including the biodegradation of organic pollutants (7, 8, 10, 12, 17, 27, 32, 55, 56, 61). Acquisition of catabolic genes can enhance contaminant biodegradation by increasing the diversity of organisms able to effect at least partial transformation of a compound or expanding on existing pathways so that degradation is more extensive or complete (mineralization). Pathway complementation is exemplified by strains engineered to possess the upper biphenyl degradation pathway as well as the lower chlorobenzoate and chlorocatechol pathways, resulting in an enhanced ability to mineralize polychlorinated biphenyls (18, 25, 35, 46). Similar hybrid pathways could evolve naturally in the environment by lateral gene transfer and affect the activity of microbial communities mediating polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) biodegradation, but relatively little is known about their occurrence.

The recovery of PCB-mineralizing strains from bioreactors or soil inoculated with the o-halobenzoate degrader Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2 (22, 53) appeared to reflect a natural gene transfer event. To facilitate identification of the biodegradation genes and gain tools needed for verification of gene transfer, we developed a mating system that exploited strain JB2's inability to utilize an s-triazine (cyanuric acid) as a sole nitrogen source (41). Strain JB2 was mated with Pseudomonas sp. strain D, which could grow on cyanuric acid and benzoate but not 2-chlorobenzoate (2-CBa). All isolates recovered after selection for growth on 2-CBa–cyanuric acid were strain D derivatives. Hybridization analysis of genomic digests from the parental strains and a selected isolate, Pseudomonas sp. strain D1, revealed DNA fragments that were present in strains D1 and JB2 but absent from strain D. We hypothesized that these fragments were part of the mobile DNA and that genes encoding 2-CBa degradation were present on these fragments or were linked to them. In the present study, we cloned and characterized the regions of the strain JB2 genome encompassing the fragments apparently acquired by strain D1 to test this hypothesis as well as to identify other genes that might function in biodegradation pathways or mobilization of the element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, culture media, and DNA manipulations.

P. aeruginosa strain JB2 and Pseudomonas hutiensis strains D and D1 were described previously (23, 41). Strain D1 was previously called strain JPL, and this designation was changed in accordance with standard criteria (9) to indicate that it is a derivative of strain D. Escherichia coli cultures of strains DH5α and JM109 were obtained from Promega (Madison, Wis.) and used for genomic library construction and routine cloning, respectively. E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS (Promega) was used for T7-directed expression of genes cloned into pET5a (Promega). Pseudomonads were grown on a mineral salts medium (MSM; 23) supplemented with an appropriate carbon source (4.2 mM benzoate or 3.2 mM 2-CBa). E. coli cells were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium to which ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (35 μg ml−1), or tetracycline (12 μg ml−1) was added for plasmid selection. Genomic DNA preparation, agarose gel electrophoresis, restriction enzyme digestion, DNA ligation, and E. coli transformation were done by standard procedures (3). Purification of PCR products and DNA fragments isolated from agarose gels was done by using the using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen), respectively.

Genomic library construction and screening.

Genomic DNA from 2-CBa-grown strain JB2 was partially digested with Sau3A, dephosphorylated, and ligated into the cosmid pRK7813 (26). The ligation mixture was packaged into bacteriophage λ particles by using the Gigapack II in vitro packaging system (Stratagene, Torrey Pines, Calif.) and transfected into cells of E. coli strain DH5α. DNA fragments previously detected by hybridization as common to strains JB2 and D1 (41) were recovered from an agarose gel, labeled as described above, and used in colony lift assays (3) to probe the strain JB2 genomic library. Cosmids were isolated from clones showing hybridization in the colony lifts and mapped by digestion with restriction enzymes.

Bioinformatics.

Open reading frames (ORFs) were located with the ORF finder tool in DNAstar (DNAstar, Madison, Wis.). Nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarities were determined by BLAST-N and PSI-BLAST searches (1, 2). Protein motifs were identified by BLAST-P (2), BLOCKS (21), and TMHMM (54) analyses. Multiple sequence alignments were assembled by using CLUSTAL-W (60).

PFGE-CHEF.

Plasmid profiles were analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) by the contour-clamped homogenous electric field (CHEF) technique. Cells were lysed in agarose plugs by using the method of Buchrieser et al. (5). To linearize plasmids, plugs were treated with S1 nuclease (4). Plasmids were separated by using a CHEF-DR II (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) run at 200 V (21 h, 14°C) with switching times ramping from 1 to 40 s. The mid-range PFG Marker II (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was used as a molecular weight marker for linear DNA. Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60 harbors a ca. 85-kb plasmid (63) and was used as a positive control.

Hybridization analyses.

DNA segments used as probes were recovered from restriction enzyme digests of pJPL1 (Fig. 1). The exception was the probe targeting hybA, which was synthesized by PCR as described below. The digested fragments and PCR products were purified from agarose gels as described above and then were random-primed labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP (Genius kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). For Southern blotting, DNA was transferred from agarose gels to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) by using a Posiblot pressure blotter (Stratagene) and cross-linked to the membranes by using a UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). Hybridization was done under high stringency, and detection was by chemiluminescence (Genius chemiluminescence system; Boehringer Mannheim).

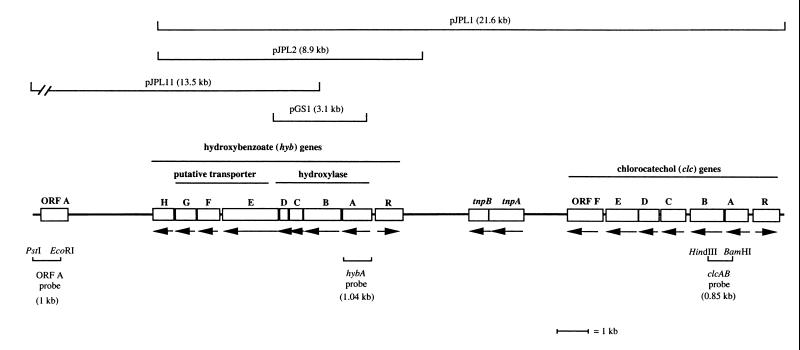

FIG. 1.

Map of transmissible DNA cloned from P. aeruginosa strain JB2. Putative genes are shown in boxes, and their orientations are indicated by the arrows. The sections and sizes of the cloned DNA encompassed by cosmid clones (pJPL1) and the region cloned for expression (pGS1) are indicated at the top. The insert in pJPL11 extends an additional 3.8 kb downstream of ORF A, but this region contains no additional ORFs and has been truncated. Regions of DNA to which probes were developed are shown at the bottom.

PCR.

PCR was used to amplify a 3,118-bp fragment encompassing the putative hybABCD genes. The primers (forward, 5′-ACT ATC AGA CGA CAT ATG GAG TTA C-3′; reverse, 5′-GTG ACC GCC ATG TGG ATC CTG TTT AT-3′) created NdeI and BamHI (italicized) sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The thermal cycling program was a 5-min hot start (95°C), 15 cycles of 1 min of denaturation (94°C), 1 min of annealing (50°C), and 5 min of extension (72°C), 20 cycles of 30 s of denaturation (94°C), 30 s of annealing (56°C), and 5 min of extension (72°C), and a final 10 min of extension (72°C). Reaction mixtures (50 μl total) contained 3 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 ng of template DNA, 0.4 mM concentrations of each primer, 1 M betaine, and 2% dimethyl sulfoxide. The primers used for amplification of hybA (forward, 5′-TAT ACT GGA TCC CCT GTA TAA AC-3′; reverse, 5′-CAT CCT AAG CTT GCT AAT CGG CG-3′) created BamHI and HindIII sites (italicized), respectively. Reaction mixtures were composed as described above with the following thermal cycling parameters: a 5-min hot start (95°C) followed by 30 cycles of 30 s of denaturation (95°C), 1 min of annealing, and 1.5 min of extension (72°C) and a final 10 min of extension (72°C). Following amplification, the reaction mixtures were mixed with 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 10 volumes of 100% ethanol (room temperature) and immediately centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min. The precipitated PCR products were dissolved in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and, following electrophoresis, were excised from agarose gels. Amplification of 16S rRNA genes from strains D and D1 was done by using primers (27F and 1492R) and thermal cycling conditions described by Devereux and Willis (11). Recovery and purification of PCR products from agarose gels were done as described above.

Heterologous expression.

The PCR-amplified hybABCD genes were NdeI-BamHI digested and ligated into NdeI-BamHI-digested pET5a. In the resulting construct (pGS1), hybABCD were oriented such that they could be expressed under the control of the T7 promoter. The construct was transformed into E. coli strain JM109, and its structure was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis. The construct was harvested from strain JM109 and transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS for expression. Cultures (100 ml) of the latter were grown overnight (30°C) in LB-ampicillin-chloramphenicol medium, harvested, washed with phosphate buffer (13 mM, pH 7), resuspended in 2 ml of buffer, and inoculated into 200 ml of fresh LB-ampicillin medium. Cultures were then incubated at 30°C, and when the densities reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.5, T7 polymerase was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. After IPTG addition, the cultures were incubated for 4 h at 30°C. A culture of strain BL21(DE3)pLysS pET5a was treated identically to that carrying pGS1. After induction, the cultures were harvested, washed with MSM, and resuspended in 10 ml MSM. Test substrates were added to the cultures and to medium blanks from filter-sterilized aqueous stocks. When pyruvate was included in the reaction mixture, it was added from a filter-sterilized 1 M stock. The test cultures, control cultures, and media blanks were incubated with shaking at 30°C. Periodically, 750-μl aliquots were taken from the vessels, the cells were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 1 min), and supernatant was transferred to vials for analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography. At the end of the incubation, the remaining cell suspension was centrifuged and the supernatants were removed for extraction and analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

Analytical procedures.

Aqueous samples from cultures and blanks were analyzed directly by high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously (41). For GC-MS, culture supernatants were acidified with 5 N H2SO4 and extracted with 2 volumes of ethyl acetate. The organic phases were pooled, dehydrated over anhydrous Na2SO4, and brought to dryness with heating. The samples were then dissolved in methanol, transferred to reaction vials (Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa.), and dried under N2. Pyridine (500 μl) was added to dissolve the samples, followed by 500 μl of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide–trimethylchlorosilane (99:1 [vol/vol]; Supelco). The silylated samples were injected into a Hewlett-Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph equipped with a 7673A autosampler, split-splitless capillary column injection port, and a model 5972A mass selective detector. Operating parameters were as follows: injector, 250°C; detector, 250°C; He carrier gas, 1 ml min−1; and He make-up gas, 36 cm s−1. Separation was achieved with a J & W Scientific (Folsom, Calif.) DB-5MS fused silica capillary column (40 m by 0.25 mm; film thickness, 0.25 μm). The temperature program was 80°C for 2 min, and then ramping to 195°C at 20°C min−1 (12-min final hold). The detector interface and ion source temperatures were 300°C. The detector was operated in the electron ionization (70 eV) mode scanning masses of 30 to 400 (1.6 s decade−1).

Nucleotide sequence determination and sequence accession numbers.

Automated sequencing was done by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center on an ABI PRISM 373 DNA Sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). Sequence data obtained in this study were cataloged under GenBank accession numbers AF087482 (the mobile DNA including hybABCD) and AY049039 (P. hutiensis strain D 16S rRNA gene).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phylogenetic analysis of strains D and D1.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences from strain D and D1 were identical and had significant identities (97%) with several species of Herbaspirillium. However, the greatest identity (99.8% over 1,413 bp) was to P. huttiensis ATCC 14670T. Accordingly, the organisms' taxonomic affiliations were revised to P. huttiensis strains D and D1.

Genomic library screening.

Three strain JB2 genomic library clones that possessed DNA fragments that were previously detected by hybridization were identified (41) as common to strains JB2 and D1. Restriction enzyme analysis showed that the three clones were overlapping and collectively spanned ca. 26 kb (Fig. 1). Nineteen ORFs were located and, based on nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence similarities, were identified as putatively encoding (i) a ring hydroxylating oxygenase, (ii) an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type transporter, (iii) an extradiol ring-cleavage dioxygenase, (iv) transcriptional regulators, (v) enzymes mediating chlorocatechol degradation, and (vi) transposition functions.

Sequence and functional analysis of ring-hydroxylating oxygenase.

BLAST searches with the ORFs designated hybABCD returned similarities to the ferredoxin oxidoreductase, large α subunit, small β subunit, and ferredoxin components, respectively, of ring-hydroxylating oxygenases. The majority of these similarities were to naphthalene dioxygenase genes. However, the most significant identities were to genes encoding a salicylate 5-hydroxylase from Ralstonia sp. strain U2 (16), nitrotoluene dioxygenases from Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42 (39), and Burkholderia sp. strain DNT (58) or to two ORFs with unknown function located within the nitrotoluene dioxygenase gene clusters of strains JS42 and DNT.

The putative ferredoxin oxidoreductase, HybA (predicted Mr, 35,002 Da), was 52 to 59% identical to ferredoxin reductases from strains JS42, DNT, and U2. Each of these proteins had in the N terminus the C-X4-C-X2-C-X2-C motif characteristic of [2Fe-2S] binding domains conserved in plant-type ferredoxins (33, 36, 38). HybB (predicted Mr, 48,928 Da) was 78% identical to NagG, which is the proposed α subunit of the strain U2 salicylate 5-hydroxylase. HybB was also 78% identical to the polypeptide predicted for ORF2 from strain DNT and 74% identical to the truncated version of ORF2 from strain JS42. Collectively, HybB, NagG, and the polypeptide predicted for ORF2DNT had 75% identity. Consistent with characteristics of other α subunits, HybB possessed the C-X-H-X15-17-C-X2-H motif for binding of a Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster (33, 36, 38) and the conserved His-208, His-213, and Asp-362 residues that may coordinate mononuclear iron at the active site (19, 30, 31, 40). HybC (predicted Mr, 18,479 Da) was 57% identical to NagH, the proposed β subunit of the strain U2 salicylate hydroxylase, and 57% identical to ORF X (unknown function) from strain DNT. HybC also had 61% identity to a truncated putative polypeptide, PahH, from a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon catabolic gene cluster in Comamonas testosteroni strain H (GenBank accession no. AF252550). The proposed ferredoxin, HybD (predicted Mr, 10,950), had 51 to 63% identity with ferredoxins from strains JS42, DNT, and U2, all of which possessed a Rieske [2Fe-2S] binding domain.

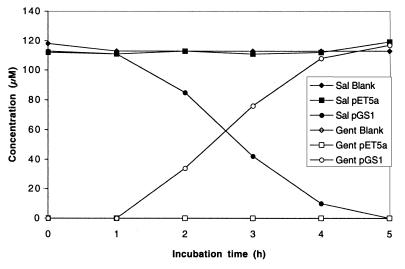

E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS pGS1 was tested for activity with benzoate (Ba), 2-CBa, 2-nitrotoluene, 2-hydroxybenzoate (salicylate), 3-hydroxybenzoate (3-HBa), and 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBa) as substrates. There was no detectable transformation of Ba, 2-CBa, 3-HBa, or 4-HBa. For 2-nitrotoluene, one minor peak (ca. 0.1% of total peak area) that was unique to the E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS pGS1 culture was detected after 3 h of incubation. Because it was a minor product, we did not characterize it further. With salicylate, a significant decrease in substrate concentration and accumulation of gentisate was detected within 2 h (Fig. 2), and after a 5-h incubation, salicylate was quantitatively transformed to a metabolite identified by GC-MS as gentisate. There was no significant decrease in the salicylate concentrations in the medium blanks or in incubations with E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS pET5a.

FIG. 2.

Time course of salicylate (Sal) transformation to gentisate (Gent) by E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells expressing hybABCD (pGS1). Controls were E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells with the vector alone (pET5a) and medium containing substrate but no cells (blank).

The salicylate 5-hydroxylase activity demonstrated for hybABCD was consistent with that predicted from sequence identity to functionally characterized genes nagAaGHAb from Ralstonia sp. strain U2 (16, 66). Most of the salicylate hydroxylases described in the literature are monomeric flavoprotein monooxygenases that transform salicylate to catechol (57, 59, 64, 65). To the best of our knowledge, the present report and that of Fuenmayor et al. (16) are the only two confirmed examples of salicylate hydroxylase activity associated with oxygenases outside the flavoprotein group. The enzymes produced by hybABCD and nagAaGHAb are also unique in that the conversion of salicylate to gentisate has been reported for only one of the flavoprotein monooxygenases (57). The proposed salicylate 5-hydroxylase of strains JB2 and U2 thus has characteristics that bridge enzyme families; it is a functional homolog of flavin monooxygenases (e.g., salicylate hydroxylase) but has the subunit composition and associated signature sequences characteristic of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases.

While hybABCD and nagAaGHAb have a number of structural and functional similarities, the integration of these genes into broader gene clusters and metabolic pathways differs. In strain U2, nagAaGHAb are clustered with 15 other nag genes that collectively encode the complete pathway for metabolism of naphthalene through the gentisate pathway (66). This physical arrangement is not conserved in strain JB2. Furthermore, strain JB2 does not grow on naphthalene but can utilize salicylate and gentisate as sole carbon sources. Strains D and D1 grew only on salicylate. Why strains JB2 and D1 differed in gentisate utilization is currently unknown but could indicate that genes for gentisate metabolism were either not present on the same mobile element as hybABCD, were present on the same element in JB2 but subsequently deleted after transfer to D1, or were transferred and retained along with hybABCD but were not expressed in strain D1. Further physical characterization of the element in strain JB2 is needed to answer this question.

Sequence analysis of regions downstream of hybABCD.

Three ORFs had amino acid sequence similarities to components of an ABC-type membrane transport system (hybEFG; Fig. 1). ABC transporters minimally consist of a transmembrane domain and a nucleotide-binding domain, which we propose were represented by HybE and HybFG, respectively. The polypeptide expected for hybE (predicted Mr, 66,039) was strongly hydrophobic, with a grand average of hydropathy of 0.80, and possessed at least 12 probable membrane-spanning α-helices. HybE had sequence similarities to proteins either known or hypothesized to be the transmembrane domain of ABC-type transport systems. A putative membrane-spanning protein from the carbazole-degrader Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (49) had the largest continuous region of similarity to HybE, with 30% identity over residues 40 to 485. All other significant similarities were to one of two regions of HybE that covered residues 27 to 312 or residues 328 to 438; this pattern could indicate a gene fusion in hybE. The greatest similarities found for the first and second regions were to HbaF (34% identity) and HbaG (38% identity), respectively, which putatively comprised the transmembrane domain of an ABC transporter in Rhodopseudomonas palustris strain CGA009 (13). It is interesting that in strain CGA009, hbaF and hbaG occur within a large cluster of genes for anaerobic degradation of benzoate (13). The polypeptides expected for hybF (predicted Mr, 26,968) and hybG (predicted Mr, 25,726) possessed Walker consensus sequences A (P loop) and B, which are proposed to function as ATP-binding sites (48, 62). In HybG, a region with similarity to the ABC transporter family signature (C motif) was located N terminal of the Walker B site (24, 52). The known or putative transporters that had similarity in the nucleotide-binding domains to HybF and HybG were the same group that had similarity in the transmembrane domain to HybE.

For the ORF identified as hybH, no significant nucleotide sequence similarities were found in BLAST-N searches. However, the putative polypeptide (predicted Mr, 25,945 Da) possessed an N-terminal, helix-turn-helix motif and showed similarity to a variety of Lys-R-type transcriptional regulatory proteins. The greatest similarity was to HybR (40% identity), which was the putative protein upstream of hybABCD. HybH also had 39% identity with NagR, the putative regulatory protein upstream of nagAaGHAb (66), and with NahR, the transcriptional regulator of the naphthalene degradation genes from pNAH7 (51).

The final ORF, ORF A, showed no significant nucleotide sequence similarities in BLAST searches. But, the putative protein (predicted Mr, 34,108) had similarities to a number of extradiol dioxygenases. The greatest identity (36%) was to a 2,3-dioxygenase from the naphthalenesulfonate-degrader Sphingomonas sp. strain BN6 (20). The predicted polypeptide also had 30% identity to catechol 2,3-dioxygenase II from Ralstonia eutropha strain JMP 222 (28) and 30% identity to a 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase from Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 (47).

Analysis of regions upstream of hybABCD

The ORF designated hybR was adjacent to, but oriented in the opposite direction of, hybA (Fig. 1). The putative HybR polypeptide (predicted Mr, 34,461 Da) possessed an N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif, which forms the DNA-binding domain characteristic of the LysR family (50). HybR had 53% identity to NahR, which is a LysR activator of the naphthalene and salicylate operons on pNAH7 (51), and 60% identity to NagR, a putative LysR transcriptional activator of the nag cluster from strain U2 (66). Predicted proteins from regions upstream of ntdAa and dntAa in strains JS42 and DNT had identities with HybR of 63 and 64%, respectively.

Further upstream were ORFs with similarity to genes encoding transposition functions and chlorocatechol (clc) degradation genes (Fig. 1). The former of these included a transposase (tnpA) and a transposase-associated ATP-binding protein (tnpB) of the IS21/IS1162 family (15). The genes of the clc cluster represented the complete suite of enzymes for chlorocatechol degradation and had identities of at least 98% to putative functional homologs from pAC27 (6, 14) or Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (29). These genes were as follows (gene product function; origin): clcR (LysR-type transcriptional regulator; pAC27), clcA (chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase; pAC27), clcB (chloromuconate lactonase; pAC27), ORF C (unknown; Pseudomonas sp. strain B13), clcD (dienelactone hydrolase; strain B13), and clcE (maleylacetate reductase; strain B13). The ORF downstream of clcE had 99% identity with a partial sequence downstream of clcE in strain B13 (29); the polypeptide predicted for this ORF had only weak similarity to a putative protein from Streptomyces coelicolor (45).

The presence of the clc genes was, in addition to the phenotype of chlorobenzoate degradation acquired by strain D1, an indication that the mobile element encoded functions for the metabolism of haloaromatic compounds as well as for hydroxybenzoate degradation. The clc operon encodes the modified ortho pathway for catabolism of chlorocatechols (14), which are intermediates in the aerobic metabolism of chloroaromatic compounds, including chloro-benzoates, -benzenes, -biphenyls, -phenols, and -phenoxyacetates. Of these, strain JB2 grows only on chlorobenzoates (23). Given these growth characteristics, we hypothesize that in strains JB2 and D1, the clc-encoded functions are involved in the downstream metabolism of di- and tri-CBas.

Hybridization and PFGE-CHEF analyses.

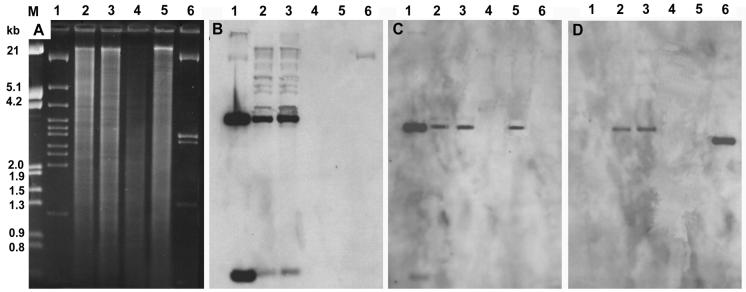

Genomic DNA of strains JB2, D, and D1 were examined with probes targeting an internal region of cloned DNA as well as to the left and right extremities (Fig. 1). Strains JB2 and D1 yielded identical hybridization patterns to all probes, whereas there was no hybridization by any probe to strain D (Fig. 3). Thus, all of the cloned strain JB2 DNA was transmissible and acquired by strain D1. Subculturing of either strain JB2 or strain D1 on benzoate gave rise to mutants unable to grow on salicylate or 2-CBa. Genomic DNA from mutants of both strains hybridized to the clcAB probe but not to probes targeting hybA or ORF A (Fig. 3). Thus, mutants of both strain JB2 and D1 had undergone a deletion that encompassed the hyb genes and extended beyond the left side of the characterized region. As 2-CBa was not a substrate for the hybABCD-encoded hydroxylase, the 2-CBa− phenotype undoubtedly resulted from the loss of other genes that were outside of, but probably contiguous with, the characterized region. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have in a separate study identified a separate set of genes encoding an o-halobenzoate dioxygenase in strain JB2 and demonstrated acquisition of these along with hybABCD by strain D1 (W. J. Hickey and G. Sabat, submitted for publication).

FIG. 3.

Southern hybridization of PstI-digested cosmid and genomic DNA. (A) Agarose gel. Lanes: M, EcoRI-HindIII-digested λ DNA; 1, cosmid pJPL1; 2, strain JB2 genomic; 3, strain D1 genomic; 4, strain D genomic; 5, strain D1 2-CBA mutant; 6, cosmid pJPL11. Also shown are membranes showing hybridization of samples in the agarose gel to probes targeting hybA (B), clcAB (C), or ORF A (D). (B to D) Lanes 1 to 6 are as described above.

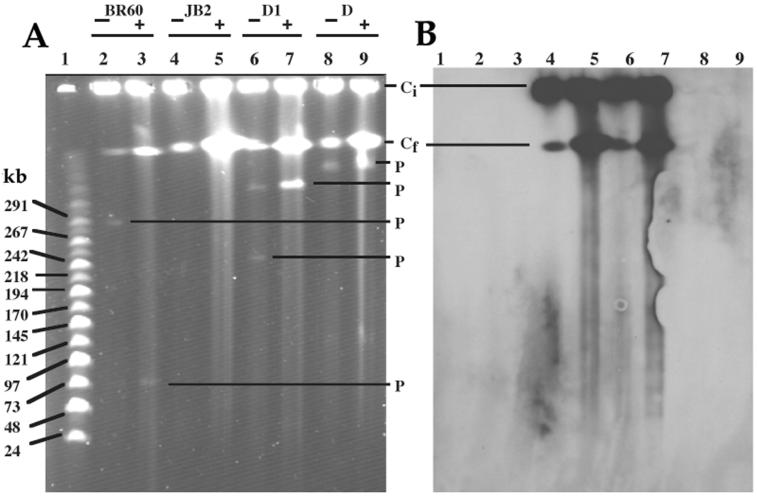

Genomic DNAs separated by PFGE-CHEF showed one band in strain D and two bands in strain D1 that could correspond to plasmids (Fig. 4). The positive control, strain BR60, also showed one plasmid band (Fig. 4). No plasmids were visible in the strain JB2 preparation (Fig. 4). The S1 nuclease-digested pBRC60 migrated close to its expected size of ca. 85 kb (63). One plasmid band was visible in the S1-treated preparations of strain D and strain D1 (designated pD and pD1, respectively); no plasmids were visible in the S1-digested strain JB2 DNA. Because pD and pD1 migrated above the largest marker, their size could not be estimated reliably but we could conclude that both were ca. >300 kb and that pD was the larger of the two. The smaller of the two bands visible in the undigested strain D1 preparation was lacking from the S1 nuclease digest; this might be explained as a small plasmid (ca. <20 kb) that eluted from the gel during electrophoresis. In both strain JB2 and strain D1, the hybA probe hybridized to areas that corresponded to fragmented or intact chromosomal DNA but not to a plasmid band (Fig. 4). The difference between pD and pD1 in apparent size suggested some type of rearrangement, but based on the available data, we could not determine if this alteration had any connection to the gene transfer event under study. However, we could conclude that if pD mediated intercellular movement, perhaps in a process like retrotransfer (42), the mobilized strain JB2 DNA characterized in this study was completely relocated to the chromosome upon entry in strain D1.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of total cellular DNAs from Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60 (lanes 2 and 3), P. aeruginosa strain JB2 (lanes 4 and 5), P. huttiensis strain D1 (lanes 6 and 7), P. huttiensis sp. D (lanes 8 and 9) by PFGE-CHEF (A) and Southern hybridization to the hybA probe (B). Lane 1 contains linear DNA size markers. Strain BR60 harbors an 85-kb plasmid (pBRC60) and was included as a positive control. Nondigested (−) and S1-digested (+) samples are indicated. Positions of intact chromosomal DNA (Ci), fragmented chromosomal DNA (Cf), and plasmid DNA (P) are indicated.

While the nature of the mobile element is unknown, the data available so far indicate that it has a propensity for chromosomal integration. This behavior appears similar to that reported for the clc element from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (43, 44), the bph-sal element from Pseudomonas putida strain KF715 (37), or Tn4371 from R. eutropha strain A5 (34). All of these are chromosomal elements with intercellular mobility. Further investigation is needed to determine the full extent and characteristics of the element. Such studies will further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying evolution of bacterial genomes in general and of catabolic pathways for anthropogenic pollutants in particular.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by USDA NRICGP (9501422 to W.J.H.), US EPA (R82-7103-01-0 to W.J.H.), and the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences (Hatch project 3452 to W.J.H.).

We thank Charles Kaspar for the use of the CHEF apparatus and R. Campbell Wyndham for providing the culture of Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Alejandro A S, Schäffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S J, Gish W, Miller W, Meyers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton B M, Harding G P, Zuccaralli A J. A general method for sizing large plasmids. Anal Biochem. 1995;226:235–240. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchrieser C, Weagant S D, Kaspar C W. Molecular characterization of Yersinia enterocolitica by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and hybridization of DNA fragments to ail and pYV probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4371–4379. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4371-4379.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coco W M, Rothmel R K, Henikoff S, Chakrabarty A M. Nucleotide sequence and initial functional characterization of the clcR gene encoding a LysR family activator of the clcABD chlorocatechol pathway in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:417–427. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.417-427.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison J. Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid. 1999;42:73–91. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dejonghe W, Goris J, El Fantroussi S, Hofte M, De Vos P, Verstraete W, Top E M. Effect of dissemination of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) degradation plasmids on 2,4-D degradation and on bacterial community structure in two different soil horizons. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3297–3304. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3297-3304.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demerec M, Adelberg E A, Clark A J, Hartman P E. A proposal for a uniform nomenclature in bacterial genetics. Genetics. 1966;54:61–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/54.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derore H, Demolder K, Dewilde K, Top E, Houwen F, Verstraete W. Transfer of the catabolic plasmid RP4Tn4371 to indigenous soil bacteria and its effect on respiration and biphenyl breakdown. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;15:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux R, Willis S G. Amplification of ribosomal RNA sequences. 1995. p. 3.3.1. : 1–11. In A. D. L. Akkermans, J. D. van Elsas, and F. de Bruijn (ed.), Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Droge M, Puhler A, Selbitschka W. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of conjugative antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from bacterial communities of activated sludge. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s004380051191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egland P G, Pelletier D A, Dispensa M, Gibson J, Harwood C S. A cluster of bacterial genes for anaerobic benzene ring degradation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6484–6489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franz B, Chakrabarty A M. Organization and nucleotide sequence determination of a gene cluster involved in 3-chlorocatechol degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4460–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freiberg C, Fellay R, Bairoch A, Broughton W, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuenmayor S L, Wild M, Boyes A L, Williams P A. A gene cluster encoding steps in conversion of naphthalene to gentisate in Pseudomonas sp. strain U2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2522–2530. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2522-2530.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulthorpe R R, Wyndham R C. Transfer and expression of the catabolic plasmid pBRC60 in wild bacterial recipients in a fresh-water ecosystem. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1546–1553. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1546-1553.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havel J, Reineke W. Total degradation of various chlorobiphenyls by cocultures and in vivo constructed hybrid pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;78:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegg E L, Que L. The 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad—an emerging structural motif in mononuclear non-heme iron(II) enzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:625–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heiss G, Muller J, Altenbucher J, Stolz A. Analysis of a new dimeric extradiol dioxygenase from a naphthalenesulfonate-degrading sphingomonad. Microbiology. 1997;143:1691–1699. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henikoff S, Henikoff J G. Protein family classification based on searching a database of blocks. Genomics. 1994;19:97–107. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hickey W J, Brenner V, Focht D D. Mineralization of 2-chloro- and 2,5-dichlorobiphenyl by Pseudomonas sp. strain UCR2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;98:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hickey W J, Focht D D. Degradation of mono-, di-, and tri-halogenated benzoates by Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3842–3850. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3842-3850.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins C. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hrywna Y, Tsoi T V, Maltseva O V, Quensen J F, Tiedje J M. Construction and characterization of two recombinant bacteria that grow on ortho- and para-substituted chlorobiphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2163–2169. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2163-2169.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones J D G, Gutterson N. An efficient mobilizable cosmid vector, pRK7813, and its use in a rapid method for marker exchange in Pseudomonas fluorescens strain HV37a. Genetics. 1987;61:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ka J O, Tiedje J M. Integration and excision of a 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degradative plasmid in Alcaligenes paradoxus and evidence of its natural intergeneric transfer. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5284–5289. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5284-5289.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabisch M, Fortnagel P. Nucleotide sequence of the metapyrocatechase II (catechol 2,3-dioxygenase II) gene mcpII from Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP 222. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5543–5548. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasberg T, Seibert V, Schloemann M, Reineke W. Cloning, characterization, and sequence analysis of the clcE gene encoding maleylacetate reductase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3801–3803. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3801-3803.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kauppi B, Lee K, Carredano E, Parales R E, Gibson D T, Eklund H, Ramaswamy S. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Struct Fold Des. 1998;6:571–586. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange S J, Que L. Oxygen activating nonheme iron enzymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1998;2:159–172. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margesin R, Schinner F. Heavy metal resistant Arthrobacter sp.—a tool for studying conjugational plasmid transfer between Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. J Basic Microbiol. 1997;37:217–227. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620370312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason J R, Cammack R. The electron-transport proteins of hydroxylating bacterial dioxygenases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:277–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merlin C, Springael D, Toussaint A. Tn4371: a modular structure encoding a phage-like integrase, a Pseudomonas-like catabolic pathway, and RP4/Ti-like transfer functions. Plasmid. 1999;41:40–54. doi: 10.1006/plas.1998.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mokross H, Schmidt E, Reineke W. Degradation of 3-chlorobiphenyl by in vivo constructed hybrid pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90053-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niedle E L, Hartnett C, Ornston L N, Bairoch A, Rekik M, Harayama S. Nucleotide sequences of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus benABC genes for benzoate 1,2 dioxygenase reveal evolutionary relationships among multicomponent oxygenases. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5385–5395. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5385-5395.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishi A, Tominaga K, Furukawa K. A 90-kilobase conjugative chromosomal element coding for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KF715. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1949–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1949-1955.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otaka E, Ooi T. Examination of protein sequence homologies. V. New perspectives on evolution between bacterial and chloroplast-type ferredoxins inferred from sequence evidence. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:246–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parales J V, Kumar A, Parales R E, Gibson D T. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding 2-nitrotoluene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. JS42. Gene. 1996;181:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parales R E, Lee K, Resnick S M, Jiang H Y, Lessner D J, Gibson D T. Substrate specificity of naphthalene dioxygenase: effect of specific amino acids at the active site of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1641–1649. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1641-1649.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pérez-Lesher J, Hickey W J. Use of an s-triazine nitrogen source to select for and isolate a recombinant chlorobenzoate-degrading Pseudomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;133:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos-Gonzalez M-I, Ramos-Diaz M-A, Ramos J L. Chromosomal gene capture mediated by the Pseudomonas putida TOL catabolic plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4635–4641. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4635-4641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravatn R, Studer S, Springael D, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Chromosomal integration, tandem amplification, and deamplification in Pseudomonas putida F1 of a 105-kilobase genetic element containing the chlorocatechol degradative genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4360–4369. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4360-4369.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravatn R, Studer S, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Int-B13, an unusual site-specific recombinase of the bacteriophage P4 integrase family, is responsible for chromosomal insertion of the 105-kilobase clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5505–5514. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5505-5514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redenbach M, Kieser H M, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood D A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigues J L M, Maltseva O V, Tsoi T V, Helton R R, Quensen J F, Fukuda M, Tiedje J M. Development of a Rhodococcus recombinant strain for degradation of products from anaerobic dechlorination of PCBs. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:663–668. doi: 10.1021/es001308t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakai, M., E. Masai, H. Asami, K. Sugiyama, K. Kimbara, and M. Fukuda. 1999. Diversity of the meta-cleavage dioxygenese genes in a strong PCB degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Genbank BAA98135 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Saraste M, Sibbald P R, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop—a common motif in ATP-binding and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato S, Ouchiyama N, Kimura T, Nojiri H, Yamane H, Omori T. Cloning of genes involved in carbazole degradation of Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10: nucleotide sequences of genes and characterization of meta-cleavage enzymes and hydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4841–4849. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4841-4849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schell M A. Transcriptional control of the nah and sal hydrocarbon-degradation operons by the nahR gene product. Gene. 1985;36:301–309. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider E, Hunke S. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport systems: functional and structural aspects of the ATP-hydrolyzing subunits/domains. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Searles D. Ph.D. dissertation. Riverside: University of California-Riverside; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sonnheammer E L L, von Heijne G, Krogh A. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. 1998. pp. 175–182. . Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. American Association of Artificial Intelligence, Menlo Park, Calif. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Springael D, Kreps S, Mergeay M. Identification of a catabolic transposon, Tn4371, carrying biphenyl and 4-chlorobiphenyl degradation genes in Alcaligenes eutrophus A5. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1674–1681. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1674-1681.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Springael D, Ryngaert A, Merlin C, Toussaint A, Mergeay M. Occurrence of Tn4371-related mobile elements and sequences in (chloro)biphenyl-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:42–50. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.42-50.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suemori A, Kurane R, Tomizuka N. Purification and properties of 3 types of monohydroxybenzoate oxygenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis S-1. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1487–1491. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suen W C, Haigler B E, Spain J C. 2,4-Dinitrotoluene dioxygenase from Burkholderia sp. strain DNT: similarity to naphthalene dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4926–4934. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4926-4934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takemori S, Hon-nami K, Kawahara F, Katahiri M. Mechanism of the salicylate hydroxylase reaction. VI. The monomeric nature of the enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;342:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(74)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Clustal-W—improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsuda M, Tan H M, Nishi A, Furukawa K. Mobile catabolic genes in bacteria. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;87:401–410. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the alpha-subunits and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wyndham R C, Straus N A. Catabolic instability, plasmid deletion and recombination in Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:237–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00407786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamamoto S, Katagiri M, Maeno H, Hayaishi O. Salicylate hydroxylase, a monooxygenase requiring flavin adenine dinucleotide. I. Purification and general properties. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:3408–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.You I S, Murray R I, Jollic D, Gunsalus I C. Purification and characterization of salicylate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas putida PPG7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92000-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou N Y, Fuenmayor S L, Williams P A. nag genes of Ralstonia (formerly Pseudomonas) sp. strain U2 encoding enzymes for gentisate catabolism. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:700–708. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.700-708.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]