Summary

One of the most dramatic challenges in the life of a plant occurs when the seedling emerges from the soil and exposure to light triggers expression of genes required for establishment of photosynthesis.

This process needs to be tightly regulated, as premature accumulation of light‐harvesting proteins and photoreactive Chl precursors causes oxidative damage when the seedling is first exposed to light. Photosynthesis genes are encoded by both nuclear and plastid genomes, and to establish the required level of control, plastid‐to‐nucleus (retrograde) signalling is necessary to ensure correct gene expression.

We herein show that a negative GENOMES UNCOUPLED1 (GUN1)‐mediated retrograde signal restricts chloroplast development in darkness and during early light response by regulating the transcription of several critical transcription factors linked to light response, photomorphogenesis, and chloroplast development, and consequently their downstream target genes in Arabidopsis.

Thus, the plastids play an essential role during skotomorphogenesis and the early light response, and GUN1 acts as a safeguard during the critical step of seedling emergence from darkness.

Keywords: chloroplast, greening, GUN1, light signalling, plastid retrograde signalling, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Establishment of photosynthesis through chloroplast biogenesis is a highly regulated and complex process. It is light regulated and under nuclear control, as chloroplast biogenesis starts by activation of the phytochromes leading to degradation of the PHYTOCHROME‐INTERACTING FACTORs (PIFs), the major transcriptional repressors of development in light, and massive nuclear transcriptional changes (Jiao et al., 2005; Leivar & Monte, 2014). Light triggers the first phase of chloroplast development characterized by an increased expression of the photosynthesis‐associated nuclear genes (PhANGs) (Dubreuil et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2019). This initial response is believed to be completely under nuclear control, but the second phase of development required to establish fully photosynthetically active chloroplasts depends upon a retrograde signal originating in the plastids (Dubreuil et al., 2018). The nature of this signal has been intensively sought after but has so far remained unknown. Paramount to the discovery of the existence of retrograde signals was the identification of GENOMES UNCOUPLED (GUN) genes, which link the developmental and physiological status of the chloroplasts with expression of nuclear genes (Susek et al., 1993). Among the GUN genes, GUN1 has attracted the most attention as it has been proposed to integrate several signals associated with plastid dysfunction, specifically those induced by inhibitors of chloroplast development like norflurazon or lincomycin (Sullivan & Gray, 1999; Koussevitzky et al., 2007; Tadini et al., 2016, 2020b; Llamas et al., 2017; Hernández‐Verdeja & Strand, 2018; Wu et al., 2018, 2019a; Marino et al., 2019; Shimizu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Although GUN1 contains domains often associated with RNA binding (Koussevitzky et al., 2007), a direct role in plastid RNA metabolism has never been confirmed, and GUN1 has rather been associated with other processes in the plastids, such as maintenance of chloroplast protein homeostasis, regulation of protein import, plastid RNA editing, plastid transcription, and tetrapyrrole biosynthesis through the interaction with several different plastid proteins (Tadini et al., 2016, 2020b; Llamas et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018, 2019a; Marino et al., 2019; Shimizu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Despite all these efforts, neither the biologically relevant function of GUN1 nor the nature of the GUN1‐derived signal, whether it is positive or negative, has been determined.

Emerging from darkness is a delicate balancing act, and recent reports have highlighted the importance of repressive mechanisms, both at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level, to block premature chloroplast development in the dark and to avoid overaccumulation of phototoxic photosynthetic products (Armarego‐Marriott et al., 2020). These repressive processes are largely controlled by the PIFs and the degradation of transcriptional regulators by the ubiquitin–proteasome (CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC (COP)/DE‐ETIOLATED (DET)/FUSCA) pathway (Seluzicki et al., 2017). In addition, the brassinosteroid‐responsive BRASSINAZOLE‐RESISTANT‐1 (BZR1) transcription factor (TF) has been reported to interact with PIF4 and form a module to control gene expression during skotomorphogenesis (Oh et al., 2012). The gibberellin‐regulated DELLA transcriptional regulators are present in etiolated cotyledons and also interact with the PIFs and thereby regulate the expression of the PIF target genes, such as genes encoding proteins involved in Chl biosynthesis and other photosynthetic proteins (Cheminant et al., 2011).

In addition to the light‐induced nuclear control, retrograde signalling is required for chloroplast biogenesis, and early studies indicated that a plastid signal pre‐exists in dark or is rapidly generated in response to light (Sullivan & Gray, 1999). One of the first phenotypes described for gun1 was reduced greening and survival of dark‐grown seedlings shifted to light (Susek et al., 1993), a phenotype probably linked to the high accumulation of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) in the dark‐grown gun1 mutants (Xu et al., 2016; Shimizu et al., 2019). The increased Pchlide and impaired de‐etiolation of gun1 mutants have been well described, but these phenotypes, and their implications for the GUN1‐dependent retrograde signal, have not been properly investigated. To gain insight into the actual physiological role of the GUN1‐mediated retrograde signal during chloroplast biogenesis and to explore a possible role of the plastids during skotomorphogenesis and early light response, we set our research focus on the dark‐grown plastid forms: etioplasts and proplastids. This approach revealed that GUN1 is already present both in proplastids and etioplasts and that GUN1 protein levels decrease in light and as chloroplast development progresses. We performed an RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐Seq) analysis to show that the GUN1‐mediated signal regulates nuclear gene expression already in the dark, before the onset of chloroplast development and during the early light response in the absence of any chemical or genetically induced plastid stress. GUN1 contributes to the fine‐tuning of nuclear gene expression in the dark and during the early light response, and thus acts as a safeguard during the critical developmental stage of greening.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia‐0 (Col‐0) and the transfer‐DNA (T‐DNA) insertion mutants gun1‐102 (SAIL_290_D09) and gun1‐103 (SAIL_742_A11) were used for all the experiments (Sun et al., 2011; Dietzel et al., 2015; Martín et al., 2016; Tadini et al., 2016). Plants were genotyped to confirm the T‐DNA insertions and identify homozygous individuals. Primers for genotyping are listed in Supporting Information Table S1. The Arabidopsis stable pluripotent inducible cell line has been described by Dubreuil et al. (2018).

To obtain the PGUN1:GUN1:YELLOW FLUORESCENT PROTEIN (YFP) construct, the GUN1 genomic region containing 1494 bp of the promoter was PCR‐amplified using the primers listed in Table S1 and cloned into pDONR207 (Invitrogen) and subcloned into pHGY binary vector (Yamaguchi et al., 2008). To generate the GUN1 artificial microRNA (amiRNA), primers were designed using wmd3–web microrna designer and used to engineer the amiRNA precursor by site‐directed mutagenesis using pRS300 as template (S. Ossowski, J. Fitz, R. Schwab, M. Riester & D. Weigel, personal communication; primers listed in Table S1). The amiRNA‐GUN1 precursor was cloned in pDONR207 and subcloned into pMDC7 binary vector (Curtis & Grossniklaus, 2003). All constructs were verified by sequencing and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101pM90 strain. Plants were transformed using the floral dip method (Clough & Bent, 1998), and cells as already described (Pesquet et al., 2010).

Growth conditions and treatments

Seeds were surface sterilized, plated on 1× Murashige & Skoog (MS) salt mixture supplemented with vitamins (Duchefa, Haarlem, the Netherlands) with 1% (w/v) sucrose, and stratified for 3 d at 4°C in darkness. For analysis with etiolated seedlings, germination was induced by exposing the seeds to white light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) for 5 h, followed by growth in darkness for 5 d at 22°C and shifted to constant white light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) for the indicated times.

For greening and survival assays, at least 50 seeds per replicate were sown on 1× MS plates with 2% (w/v) sucrose. After etiolation, the seedlings were transferred to constant white light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) and scored for seedlings with green open cotyledons after 48 h, or with green true leaves after 1 wk. For the evaluation of the gun phenotype the seedlings were grown 6 d under constant white light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) on 1× MS plates with 2% (w/v) sucrose supplemented with 0.5 mM lincomycin hydrochloride (L2774; Sigma). For the lincomycin treatment to analyse the GUN1:YFP signal in the confocal microscopy, the 1× MS media with 1% (w/v) sucrose was supplemented with 0.5 mM lincomycin hydrochloride or with distilled water as mock.

The Arabidopsis Col‐0 cell culture was grown in 1× MS supplemented with 3% (w/v) sucrose and maintained in the dark, 22°C, and constant shaking (Dubreuil et al., 2018). Chloroplast development was induced by transferring the cells to continuous light (150 μmol m−2 s−1), 22°C, MS media with 1% (w/v) sucrose and constant shaking (Dubreuil et al., 2018). For induction of amiRNA‐GUN1, the dark‐grown transgenic cell lines were supplemented with 5 µM β‐oestradiol (E2758; Sigma) or with ethanol 0.1% (v/v) as mock, after refreshing the medium and before light induction of chloroplast development. Cells were harvested by vacuum filtration at the indicated times and frozen in liquid nitrogen (N2).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated using an EZNA Plant RNA Mini Kit (Omega Bio‐tek, Norcross, GA, USA) from homogenized samples, and genomic DNA was removed by DNase I treatment (EN0525; Thermo‐Fisher, Uppsala, Sweden). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using 0.5 µg RNA with the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (1708891; Bio‐Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and 10× diluted. Real‐time PCR (qPCR) was performed using iQSYBR Green Supermix (1725006CUST; Bio‐Rad) in a CFX96 Real‐Time system (C1000 Thermal Cycler; Bio‐Rad) with a two‐step protocol. The primers used are listed in Table S1. All experiments were performed with four biological replicates. Relative gene expression was normalized to the expression of AT1G13320 for seedling and AT4G36800 for cell samples and calibrated to 1 relative to the indicated condition or genotype. Data analysis was done using CFX Manager (Bio‐Rad) and LinRegPCR software (Ramakers et al., 2003).

RNA preparation, sequencing, and data processing

Total RNA was extracted from whole seedlings using the RNeasy Plant Kit (Qiagen). The quantity and quality of the RNA were determined both by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) and Plant RNA Nano assay (v.1.3) built in an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System according to the RNA 6000 Nano kit protocol (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Samples were sequenced by the Beijing Genomics Institute using the DNBSEQ platform, obtaining an average yield of 4.93G data per sample. Adaptor contamination, ribosomal RNA, low‐quality reads, and reads with too many N bases were removed using SOAPnuke (Chen et al., 2018). The RNA‐Seq reads filtering summary is given in Table S2. Clean reads were aligned against TAIR 10.1 GCF_000001735.4 reference genome using Bowtie2 v.2.2.5 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012). Gene expression levels were quantified using Rsem v.1.2.12 (Li & Dewey, 2011). Normalized gene expression levels, calculated by variance stabilizing transformation, and differential expressed genes (DEGs) using q‐value ≤ 0.05 as threshold were obtained using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Volcano plots showing significant DEGs are available in Fig. S1. DEGs were ranked by fold change for further analysis.

Gene regulatory network and functional analysis

The gene regulatory network (GRN) was built using TF2Network using positive coexpression values and motifs overrepresented on promoters of DEGs (Kulkarni et al., 2018). Only DEGs were considered to build the network, and all TFs that were not DEGs were removed from the GRN. TFs and their associated families were obtained from PlantTFDB (Jin et al., 2014). Network visualization was done with Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses were performed with the standalone version of GeneMerge (Castillo‐Davis & Hartl, 2003). Revigo was used to summarize and reduce GO terms (Supek et al., 2011). Prediction of subcellular localization was done with Suba4 (Hooper et al., 2017).

Transcriptomic data for comparisons were obtained from Martín et al. (2016) (GSE78969), Koussevitzky et al. (2007) (GSE5770), Wu et al. (2018) (GSE122667), Waters et al. (2009), and Ni et al. (2017). Venn diagrams were done with Venny (Oliveros, 2015).

Protochlorophyllide determination

Fifty seedlings grown in the dark for 5 d were harvested under dim green light and frozen in liquid N2. Pigments were extracted by mixing the homogenized material in ice‐cold 80% buffered acetone and incubation at 4°C in the dark overnight. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min at 14 000 g . The fluorescence emission spectra were obtained using a Jasco FP‐6500 spectrofluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 440 nm, bandwidth 5 nm, and emission recorded between 600 and 700 nm, bandwidth 5 nm.

Anthocyanin accumulation

To observe anthocyanin production we used the method described in Cottage et al. (2010). Briefly, the seeds were sterilized and sown in 1× MS with 2% sucrose supplemented with 0.5 mM lincomycin, stratified for 2 d at 4°C in darkness, and then grown at 22°C in constant white light (100 μmol m−2 s−1) for 4 d.

Confocal microscopy and quantification of fluorescence

Confocal laser‐scanning microscopy was performed with an inverted Carl‐Zeiss LSM880 system equipped with a Plan‐Apochromat 10×/0.45 M27 objective (numerical aperture: 0.45; Carl Zeiss) or a C‐Apochromat 40×/1.2 W Korr FCS M27 objective (numerical aperture: 1.20; Carl Zeiss). YFP detection was done using an excitation 514 nm wavelength laser and a 517–606 nm filter. Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) detection was done using an excitation 405 nm laser and a 415–505 nm filter. Chl autofluorescence was detected using an excitation 633 nm laser and 638–721 nm filter.

The quantification of GUN1:YFP signal was done with high‐resolution images (2048 × 2048 px2) of chloroplast captured with the C‐Apochromat 40×/1.2 W Korr FCS M27 objective. Raw confocal images were analysed using the Fiji processing image package (Schindelin et al., 2012). Circular brightest areas, 40 or 30 px in radius, within plastids of cotyledons or roots, respectively, were selected for the quantification of the fluorescence pixel intensity (Mean Grey Value tool in Fiji). The cotyledons were separated in etiolated seedlings to enable visualization and quantification of the signal. Only the central part of the cotyledons, corresponding to the spongy mesophyll cells, and the epidermis layer of the root tips were selected for the images used for the quantification. The quantification of GUN1:YFP in roots was performed on the epidermis layer of the root tips. A total of 15–20 chloroplasts were measured per cotyledon, and 9–15 cotyledons were analysed for each of the three independent biological replicates. Fifteen plastids per root were measured from three to five roots.

Statistical analyses

Statistics were done using R 3.6.0 (R Core Team, 2019), Rstudio 1.0.136 (RStudio Team, 2016), fsa (Ogle et al., 2019), and rcompanion (Mangiafico, 2019). Boxplots were done with BoxPlotR (http://shiny.chemgrid.org/boxplotr/). Heatmaps and bubble plots were done with ggplot (Wickham, 2016).

Results

GUN1 is present in proplastids and regulates expression of PhANGs

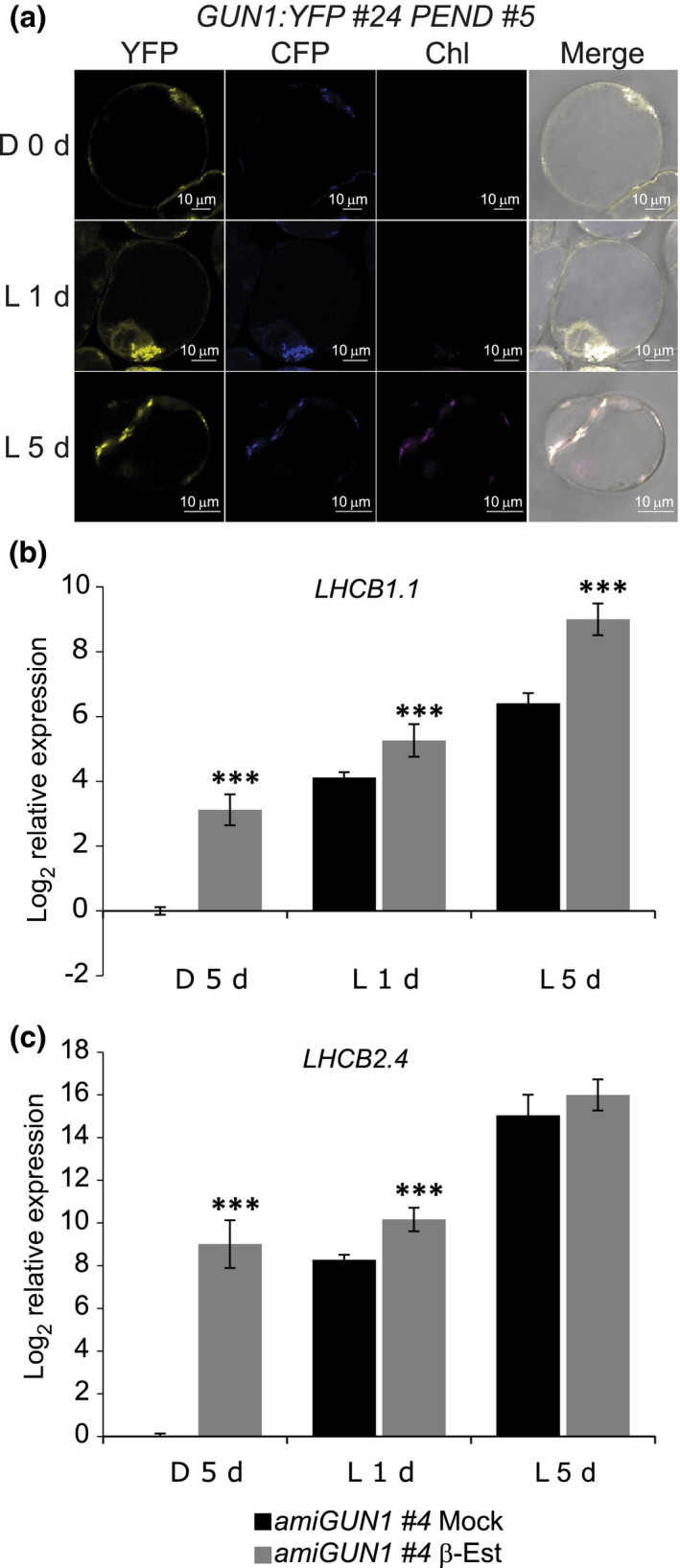

GUN1 is a very low abundant protein, but it has been detected in cotyledons of light‐grown Arabidopsis seedlings using a GUN1 35S‐driven overexpression line (Wu et al., 2018). To investigate GUN1 activity isolated from the plant developmental programme, we monitored levels of GUN1 during light‐induced greening of a pluripotent Arabidopsis single cell culture. In this cell culture, chloroplast development proceeds from proplastids to functional chloroplasts similarly to the process taking place in the meristems to form mature leaves. In the cell culture, the greening process is significantly slower than the process in light‐exposed etiolated seedlings, and the development of a mature functional chloroplast from the proplastids takes several days (Dubreuil et al., 2018). The cell line does, however, provide both high temporal and cellular resolution. We transformed the Arabidopsis cells with GUN1:YFP under the control of the GUN1 endogenous promoter (PGUN1:GUN1:YFP) and analysed GUN1:YFP localization in two independent lines. We used PLASTID ENVELOPE DNA‐BINDING:CFP, a marker for plastid nucleoids, to confirm plastid localization (Terasawa & Sato, 2005; Kindgren et al., 2012). Surprisingly, the confocal microscopy revealed that GUN1:YFP fluorescence is present in the proplastids of dark‐grown transgenic cells (Figs 1a, S2a). A clear fluorescence signal was detected both from the dark‐grown cells and the cells exposed to light for 1 and 5 d. The GUN1:YFP signal completely overlapped with the plastid marker, confirming a sole plastid localization of GUN1 under these conditions (Fig. 1a); and Chl autofluorescence is first detected at day 5, indicating that the proplastids initiated the transition to photosynthetically functional chloroplasts (Figs 1a, S2a). The cell images also clearly show movement of the plastids in response to light, and the proplastids cluster around the nucleus following light exposure (Fig. 1a) (Dubreuil et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

GUN1:YFP and GUN1 silencing in Arabidopsis cell culture. (a) Representative images of GUN1:YFP fluorescence in 7‐d‐old dark grown (0 d) and 1 d and 5 d of constant white light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) exposed GUN1:YFP #24 PEND #5 Arabidopsis cells transformed with PGUN1:GUN1:YFP construct. PEND:CFP was used as a marker for plastids. All the images were taken using the same confocal microscope settings. Bar, 10 μm. (b, c) LHCB1.1 and LHCB2.4 log2 relative expression in amiGUN1 #4 transgenic cells treated with ethanol (mock) or β‐oestradiol (β‐Est) to silence GUN1 and grown in dark for 5 d (D 5 d) and 1 or 5 d (L 1 d, L 5 d) following constant light exposure (150 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Gene expression was normalized to AT1G13320 and calibrated to 1 relative to mock treated cells D 5 d. Data represents the mean ± SE of the mean. Significance of the differences were determined by Wilcoxon test; ***, P < 0.001. ami, artificial microRNA; GUN1, GENOMES UNCOUPLED1; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; LHCB, LIGHT HARVESTING CHLOROPHYLL A/B; PEND, PLASTID ENVELOPE DNA‐BINDING; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

The PGUN1:GUN1:YFP cell lines clearly show that the GUN1 protein is present in proplastids and in the dark. To investigate the possibility that a GUN1‐dependent retrograde signal is active in the proplastids, we analysed expression of two known retrograde‐responsive PhANGs in the cell culture: LIGHT HARVESTING CHLOROPHYLL A/B (LHCB)1.1 and LHCB2.4. We generated independent transgenic cell lines with an oestradiol‐inducible amiGUN1 to reduce GUN1 expression (Fig. S2b). LHCB1.1 and LHCB2.4 showed higher expression levels in the oestradiol‐treated amiGUN1 dark‐grown cells and maintained higher expression during the early light response compared with the mock‐treated amiGUN1 cells in both lines (Figs 1b, S2c). The presence of GUN1 and the higher expression of LHCB genes in the amiGUN1 lines support a role for GUN1 and the GUN1 retrograde signal controlling nuclear gene expression in proplastids and during the chloroplast development process.

GUN1 is present in etioplasts and plastids of nongreen plant tissues

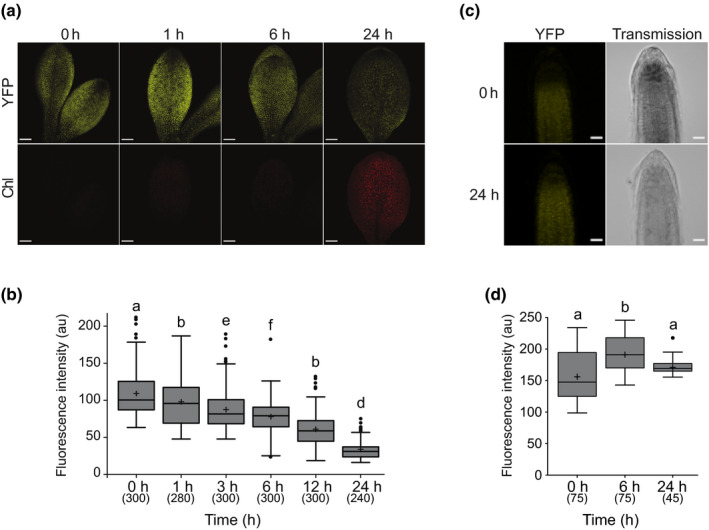

The existence of a retrograde signal in dark‐grown plants has been suggested by several studies (Sullivan & Gray, 1999; Woodson et al., 2013; Martín et al., 2016), and our new results demonstrating GUN1 presence and activity in proplastids also encouraged us to investigate GUN1 in etiolated seedlings. We analysed the levels of GUN1 protein in dark‐grown seedlings and during de‐etiolation, using Arabidopsis gun1‐102 and gun1‐103 mutants complemented with the same construct used in cell culture, PGUN1:GUN1:YFP (gun1‐102 GUN1:YFP and gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP), which allowed us to monitor GUN1 in seedlings under natural conditions. Independent transformed mutant lines recovered the wild‐type phenotype regarding accumulation of anthocyanins in 4‐d‐old seedlings (Cottage et al., 2010) and wild‐type expression of LHCB2.2 and LHCB2.4 upon lincomycin treatment (Koussevitzky et al., 2007), confirming that the GUN1:YFP fusion protein was functional (Fig. S3). The dynamics of GUN1:YFP accumulation during the de‐etiolation process was determined by confocal microscopy. A strong YFP fluorescence signal was detected in etioplasts of cotyledons from 5‐d‐old dark‐grown seedlings in all the complemented lines (Fig. S4a), indicating that GUN1 is present in nonphotosynthetic plastids before light‐induced differentiation. Following 24 h light exposure, the GUN1:YFP signal decreased and the GUN1 levels were almost undetectable (Fig. S4a). Expression of the transgene was detected with qPCR, indicating that the decrease in the fluorescence signal after 24 h in light is not due to reduced GUN1:YFP expression. The expression profile of the GUN1:YFP transgene is similar to the endogenous GUN1 during the dark to light shift (Fig. S4b,c). Furthermore, in contrast to the observation at the protein level, the expression of GUN1 increased in response to light. To further investigate the dynamics of the GUN1 protein, a more detailed study was performed using two complemented lines: gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP #6.3.6 and gun1‐102 GUN1:YFP #6.1.1. We analysed the GUN1 fluorescence signal over time following a shift of 5‐d‐old etiolated seedlings to constant light. Fluorescence could be detected in the cotyledons following 1 and 3 h exposure to light, but the levels were slightly lower compared with the dark. The GUN1 fluorescence signal declined further following 6 h and reached the lowest level after 24 h in the light, when the cotyledons were green and chloroplast developed (Figs 2a,b, S5a,b). We performed an immunoblot blot analysis using cotyledons of gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP from the time‐course experiment. The Western blot results displayed a similar pattern to the quantification of the fluorescence signal, with high GUN1:YFP protein levels in the etiolated cotyledons that decrease with light and progression of chloroplast development (Fig. S6; Methods S1). A second band of larger size appeared at the later time points (Fig. S6). This was also observed by Wu et al. (2018), but the significance of this band is unclear at this point.

Fig. 2.

GUN1:YFP in dark‐grown and light‐exposed Arabidopsis seedlings. (a) Fluorescence of GUN1:YFP in 5‐d‐old etiolated cotyledons of gun1‐102 GUN1:YFP #6.1.1 seedlings exposed 0, 1, 6, or 24 h to constant light (150 μmol m−2 s−1). Bar, 100 μm. (b) Quantification of GUN1:YFP based on fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units (au)) in plastids of seedlings grown as in (a). Results from three independent replicates, with four or five cotyledons per replicate and time‐point, and 20 chloroplasts per cotyledon (total n in parentheses). (c) Fluorescence of GUN1:YFP in 5‐d‐old etiolated roots of gun1‐102 GUN1:YFP #6.1.1 seedlings exposed 0 or 24 h to constant light (150 μmol m−2 s−1). Bar, 20 μm. (d) Quantification of GUN1:YFP based on fluorescence intensity in plastids of roots grown as in (c). Results from three or five roots and 15 chloroplasts per root (total n in parentheses). (a, c) All the images were taken using the same confocal microscopy settings. (b, d) Boxplot centre lines show the medians and plus signs show the mean of all the fluorescence intensity measurements; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles; potential outliers are plotted as circles. Significance of the differences and differences between groups were determined with a Kruskal–Wallis test, (b) P < 2.2e−16 and (d) P < 1.7e−7, and a post hoc Dunn test with Bonferroni correction. Groups sharing a letter do not differ significantly (α = 0.05). GUN1, GENOMES UNCOUPLED1; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

Degradation of GUN1 upon chloroplast development in light was consistent with the report using a P35S:GUN1:GFP line, showing that the GUN1 protein is highly unstable and that its degradation might be controlled by the CLPC chaperone (Wu et al., 2018). By contrast, GUN1:YFP levels in plastids of the root tissues remained high during the entire de‐etiolation process, further indicating that the GUN1 signal is active in nonphotosynthetic plastids independent of light (Figs 2c,d, S5c,d). The detection of elevated levels of the GUN1:YFP fusion protein in etioplasts and in root plastids indicates that GUN1‐dependent retrograde signal is active before the onset of chloroplast biogenesis in seedlings and that the degradation of GUN1 might be triggered by chloroplast biogenesis in photosynthetic tissues.

The GUN1 retrograde signal regulates nuclear gene expression in etiolated seedlings

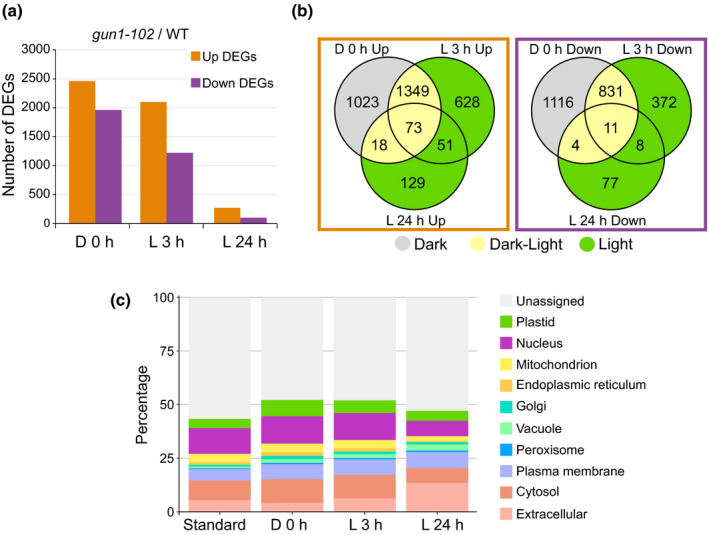

Until this date, most transcriptomic profiling of gun1 mutants has been done on light‐grown seedlings where chloroplast development has already been completed and GUN1 protein is at very low levels, or under conditions that block chloroplast development, such as growth on inhibitors like lincomycin or norflurazon (Koussevitzky et al., 2007; Marino et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019b; Richter et al., 2020). Our results suggest that GUN1 could contribute to the suppression of plastid development by controlling nuclear gene expression. In order to reveal the extent of GUN1‐dependent control of nuclear gene expression in etiolated seedlings and during early light response, we performed RNA‐Seq analysis of gun1‐102 and wild‐type 5‐d‐old etiolated seedlings (D 0 h), and 5‐d‐old etiolated seedlings subsequently exposed to light for 3 h (L 3 h) or 24 h (L 24 h). This allowed us to analyse the effect of GUN1 in etiolated seedlings when GUN1 levels are very high, during early light induction of chloroplast development when the levels are still high, and when chloroplast development is completed and GUN1 levels are at a minimum. In agreement with our observed protein data, the largest number of DEGs (q‐value ≤ 0.05, Fig. S1) in gun1‐102 compared with wild‐type was observed in etiolated seedlings with 4425 DEGs (2463 upregulated and 1962 downregulated genes), followed by seedlings exposed to 3 h light with 3323 DEGs (2101 upregulated and 1222 downregulated genes). In comparison, the number of DEGs after 24 h in light was 371 (271 upregulated and 100 downregulated), which reflects the low levels of GUN1 following 24 h light exposure (Fig. 3a; Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptomic analysis of dark‐grown and light‐exposed wild‐type (WT) and genomes uncoupled1 (gun1)‐102 Arabidopsis seedlings. (a) Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the gun1‐102 seedlings compared with the WT. Up and downregulated genes are shown for etiolated (D 0 h) and de‐etiolated for 3 h (L 3 h) or 24 h (L 24 h). (b) Venn diagrams showing the overlaps between conditions for the up and downregulated genes in gun1‐102. The DEGs exclusively deregulated in dark, dark and light, or only in light are highlighted in grey, yellow, or green, respectively. (c) Relative subcellular localization of the protein products in gun1‐102 DEGs. Estimation of the subcellular abundance was done with SUBA4 based on published experimental datasets. Standard represents all available TAIR10 Arabidopsis Genome Initiative identifiers with assigned high‐confidence subcellular localization.

To identify specific genes that depend upon GUN1, we compared the DEGs for the three conditions (D 0 h, L 3 h, and L 24 h). Overlapping DEGs showed a significant number of both shared and specific genes between the three time‐points (Fig. 3b). In total, 38% of the genes were exclusively deregulated in etiolated seedlings (Dark), 40% were common to both etiolated and de‐etiolated seedlings (Dark‐Light), and 22% were differentially expressed only in seedlings exposed to light (Light). These results again support an important role of GUN1 in etioplasts and during the transition from dark to light.

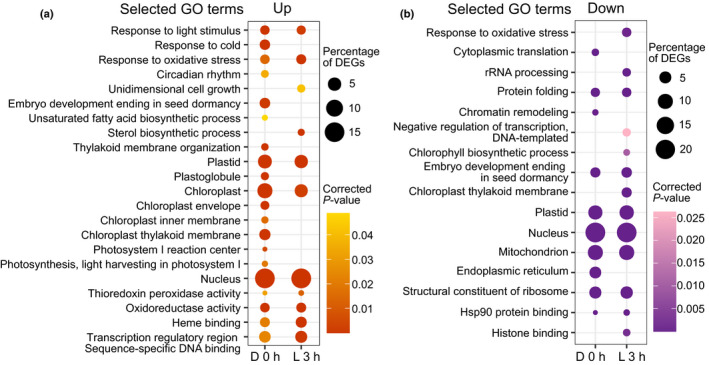

A detailed SUBA4 analysis of the predicted subcellular localization of the proteins encoded by the DEGs in each group revealed a large percentage of plastid‐localized proteins (Fig. 3c). The percentage of plastid proteins was high in the dark, and this decreased with time in light. The GO enrichment analysis for the up and downregulated genes in gun1‐102 at D 0 h and L 3 h also showed a significant number of plastid‐related terms, especially in D 0 h upregulated DEGs where genes linked to chloroplast membrane, thylakoid membrane and envelope, and photosystem I (PSI) were enriched (Figs 4a, S7a; Table S4). A detailed search revealed several upregulated LHCB genes (e.g. LHCB1.3, LHCB2.1, LHCB2.2, LHCB2.4, LHCB4.2, and LHCB3), and a specific upregulation in D 0 h of PSI and photosystem II (PSII) assembly factors, like ALBINO 3 and PIGMENT DEFECTIVE 149, and PSA2 (Fristedt et al., 2014; Schneider et al., 2014). Accordingly, many PSI (e.g. PSAO, PSAF, PSAH, PSAE, PSAH‐1, PSAL, PSAE‐1) and PSII (e.g. PSBP‐1, NPQ4, PSBR, PnsL2, PSBY, PSBX, PSBO1, PSBO2, PSBQ‐2) subunits were upregulated in the gun1‐102 mutant in D 0 h. Among the other enriched categories in the upregulated genes were GO terms related to plant development (e.g. BRZ‐INSENSITIVE‐LONG HYPOCOTYLS 4, DWARF IN LIGHT 1) and response to light (e.g. PIF1, 4, and 8, PHYB ACTIVATION TAGGED SUPPRESSOR 1, FAR‐RED‐ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1‐LIKE, and KIDARI), and in the downregulated genes there was an enrichment for plastid and thylakoid membranes (e.g. VARIEGATED2, CHLOROPLAST PROTEIN‐ENHANCING STRESS TOLERANCE, and FLUORESCENT IN BLUE LIGHT), protein folding, and translation (e.g. CHAPERONIN 60 BETA, CHLOROPLAST HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN 70‐1, CR88/HSP90.5, TRANSLOCON AT THE OUTER ENVELOPE MEMBRANE OF CHLOROPLASTS 33 and 159, HSP93‐III/CLPC2, EUKARYOTIC TRANSLATION INITIATION FACTOR 3C, 3B‐1, and 3B‐2) (Figs 4, S7b; Table S4). The GO terms enriched in the RNA‐Seq dataset reflect described targets for the GUN1 retrograde signal in response to plastid stress repressing chloroplast development, antagonizing the light development pathways, and regulating protein homeostasis, with the novelty that this response is present in dark‐grown etiolated seedlings.

Fig. 4.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of deregulated genes in genomes uncoupled1 (gun1)‐102. (a) Selected GO terms enriched in upregulated genes in etiolated (D 0 h) and de‐etiolated (L 3 h) gun1‐102 Arabidopsis seedlings. (b) Selected GO terms enriched in downregulated genes in etiolated (D 0 h) and de‐etiolated (L 3 h) gun1‐102 seedlings. (a, b) The size of the circles indicates the percentage of the deregulated genes, and the colour intensity indicates the significance (P‐value Bonferroni correction). The complete tables of enriched GO terms are in Supporting Information Fig. S5.

GUN1‐mediated and lincomycin‐triggered retrograde signals partially overlap

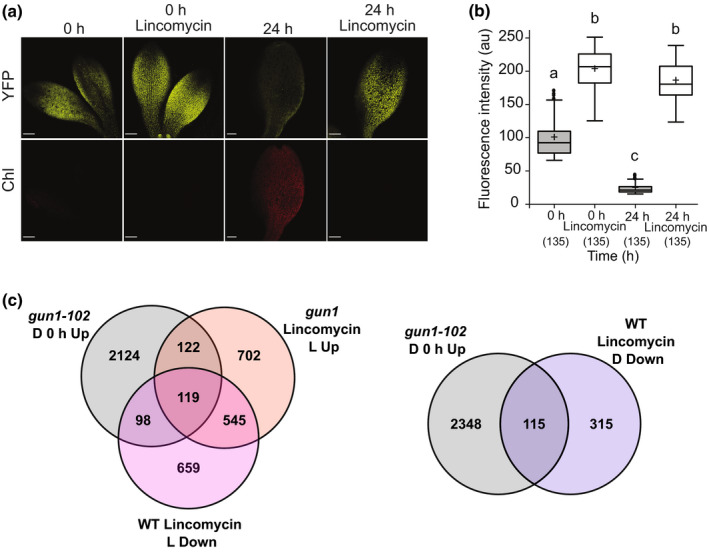

GUN1 is well characterized to play an important role in response to plastid stress conditions (Koussevitzky et al., 2007; Tadini et al., 2016, 2020b; Llamas et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018, 2019a; Marino et al., 2019; Shimizu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019), conditions that are also shown to block GUN1 degradation (Wu et al., 2018). We used lincomycin, an inhibitor of plastid translation, to test whether GUN1 levels were affected in etiolated and de‐etiolated seedlings using our mutant lines complemented with GUN1:YFP. A strong fluorescence signal was detected in the presence of lincomycin in etiolated and de‐etiolated gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP #6.3.6 and gun1‐102 GUN1:YFP #6.1.1 seedlings (Figs 5a,b, S8a,b). The GUN1:YFP levels in the lincomycin‐treated seedlings were significantly higher than in the nontreated seedlings, confirming that lincomycin‐induced plastid stress blocks GUN1 degradation even in the dark (Figs 5a,b, S8a,b).

Fig. 5.

GUN1:YFP response to lincomycin and comparison of etiolated gun1‐102 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with gun1 or wild‐type (WT) Arabidopsis seedlings treated with lincomycin. (a) Fluorescence of GUN1:YFP in 5‐d‐old etiolated cotyledons of gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP #6.3.6 seedlings grown with or without lincomycin and exposed 0 or 24 h to light. Bar, 100 μm. (b) Quantification of GUN1:YFP based on fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units (au)) in plastids’ seedlings grown as in (a). Results from three independent replicates, with three cotyledons per replicate and time‐point, and 15 chloroplasts per cotyledon (total n in parentheses). Boxplot centre lines show the medians and plus signs show the mean of all the fluorescence intensity measurements; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles; potential outliers are plotted as circles. Significance of the differences and differences between groups were determined with a Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 2.2e−16, and a post hoc Dunn test with Bonferroni correction. Groups sharing a letter do not differ significantly (α = 0.05). (c) Venn diagrams show the overlaps between gun1‐102 upregulated DEGs in etiolated seedlings (D 0 h Up) and gun1 upregulated DEGs in seedlings grown with lincomycin in light (Lincomycin L Up) or WT downregulated DEGs in seedlings grown with lincomycin in light (Lincomycin L Down) or dark (Lincomycin D Down). GUN1, GENOMES UNCOUPLED1; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

Retrograde signals induced by lincomycin are known to repress PhANGs, a repression that has been reported to be mainly mediated by GUN1 (Koussevitzky et al., 2007). We analysed GUN1 and lincomycin‐mediated transcriptomic profiles using previously published data (Koussevitzky et al., 2007; Martín et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019b). The comparison of the DEGs upregulated in gun1‐102 D 0 h with upregulated DEGs in the lincomycin light‐grown gun1 seedlings and downregulated DEGs in lincomycin light‐grown wild‐type seedlings revealed a relevant overlap, with 241 (9.8%) and 217 (8.8%) common DEGs, respectively (Fig. 5c). To avoid potential differences due to light signalling, we compared our data with downregulated DEGs in etiolated wild‐type seedlings with wild‐type seedlings treated with lincomycin. The results were similar, and an overlap of 115 DEGs (< 5%) was observed with the upregulated DEGs in gun1‐102 D 0 h (Fig. 5c). When the comparisons were made with our data for upregulated DEGs in gun1‐102 L 3 h the overlap was smaller (Fig. S8c). The shared DEGs at all the different comparisons showed enrichments in the GO terms related to photosynthesis (Table S5), and among them we found GOLDEN2‐LIKE 1 (GLK1) and GLK targets (Table S6). This is in agreement with the described role of GUN1 to repress PhANGs via GLK1 when chloroplast development is impaired (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Martín et al., 2016; Tokumaru et al., 2017). Taken together, our results suggest that there are common and exclusive pathways for GUN1 and lincomycin signals.

The GUN1 retrograde signal controls the expression of a large number of transcription factors during the de‐etiolation process

Among the DEGs obtained by comparing gun1‐102 with wild‐type plants in D 0 h and L 3 h, there was a high percentage of genes encoding nuclear‐localized proteins (Fig. 3c). The GO cellular component term ‘nucleus’ was enriched for all the DEGs, and the GO term ‘transcription regulatory region sequence‐specific DNA binding’ was enriched in the upregulated genes in both D 0 h and L 3 h (Figs 4, S7), suggesting that the expression of transcriptional regulators was affected. So far, only a few TFs have been described to respond to the GUN1 retrograde signal (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Richter et al., 2020). Two of them are the GLKs, major regulators of chloroplast biogenesis. In our transcriptomics profile of gun1‐102, only GLK1 was upregulated at the three time‐points, confirming previous reports indicating that the GUN1 retrograde signal primarily regulates GLK1 expression, and not GLK2 (Martín et al., 2016). We used available transcriptomic data for the GLKs (Waters et al., 2009; Ni et al., 2017) to search for potential GLK‐downstream genes in our dataset. There is a small overlap between the genes induced by the GLKs and the upregulated DEGs in gun1‐102 at D 0 h, L 3 h, and L 24 h. In total, only 15% of the DEGs in gun1‐102 are also under GLK control (Fig. S9).

It has been reported that GUN1 promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to inhibitors of plastid biogenesis through the regulation of several MYELOBLASTOSIS (MYB) genes and potentially of ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) (Ruckle & Larkin, 2009; Richter et al., 2020). In line with these results, we found expression of MYB12 and HY5 to be downregulated in gun1‐102 in L 3 h, but only two early anthocyanin biosynthesis genes were downregulated in the mutant (PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA LYASE and 4‐COUMAROYL COA LIGASE) (Fig. S10a). Together with GLKs, the MYB12 and HY5 represent the few already suggested targets of the GUN1 signal.

To investigate the possibility that GUN1 is regulating TFs other than what have been reported in the literature, we screened our dataset and found 308 TFs deregulated in gun1‐102, mainly in D 0 h and L 3 h, which is in accordance with the higher number of DEGs at these two time‐points (Fig. S10a). GO enrichment, excluding terms related to transcription, indicated that these transcriptional regulators were involved in response to hormones, light, abiotic factors, and development (Fig. S10b). Among the TFs downregulated in gun1‐102 we found the already mentioned MYB12 and HY5, but also REPRESSOR OF GA1‐3 1, a DELLA protein that affects the activity of HY5 and PIFs in the dark (Figs S10, S11) (Alabadí et al., 2008), ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3‐LIKE 1 (EIL1), which is involved in the ethylene‐dependent regulation of de‐etiolation (Zhong et al., 2009), and ATAF2, which is implicated in photomorphogenesis responses by regulating brassinosteroid catabolism (Peng et al., 2015).

Among the upregulated TFs in gun1‐102 were transcriptional regulators involved in de‐etiolation, response to light, and other developmental processes (Fig. S10c). A detailed search identified several known transcriptional regulators associated with the transition from dark to light, such as PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, and PIF8 that are major repressors of development in light and chloroplast biogenesis (Pham et al., 2018), BZR1 and BRI1‐EMS‐SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1) that are involved in the brassinosteroid regulation of photomorphogenesis and repression of chloroplast development in dark (Yu et al., 2011), G‐BOX BINDING FACTOR 3 that interacts with the GLKs (Tamai et al., 2002), BASIC LEUCINE ZIPPER 16 and 68 (bZIP16 and 68) that regulate LHCB expression and photomorphogenesis (Shaikhali et al., 2012), and B‐BOX DOMAIN PROTEINS 21, 24, and 25 that regulate photomorphogenesis through the regulation of HY5 (Fig. S11) (Xu, 2020). Interestingly, a great number of these TFs were not present in the lincomycin DEGs (Fig. S12), and were only found to be misregulated in our gun1‐102 dataset, including PIFs, BES1, and BZR1, and several bZIP involved in photomorphogenesis.

Our data reveal that loss‐of‐function of GUN1 results in misexpression of several key TFs associated with light signalling, response to hormones, and chloroplast biogenesis during early seedling development. These data strongly suggest that the GUN1‐mediated control over nuclear TFs during chloroplast and seedling development would be broader than previously reported.

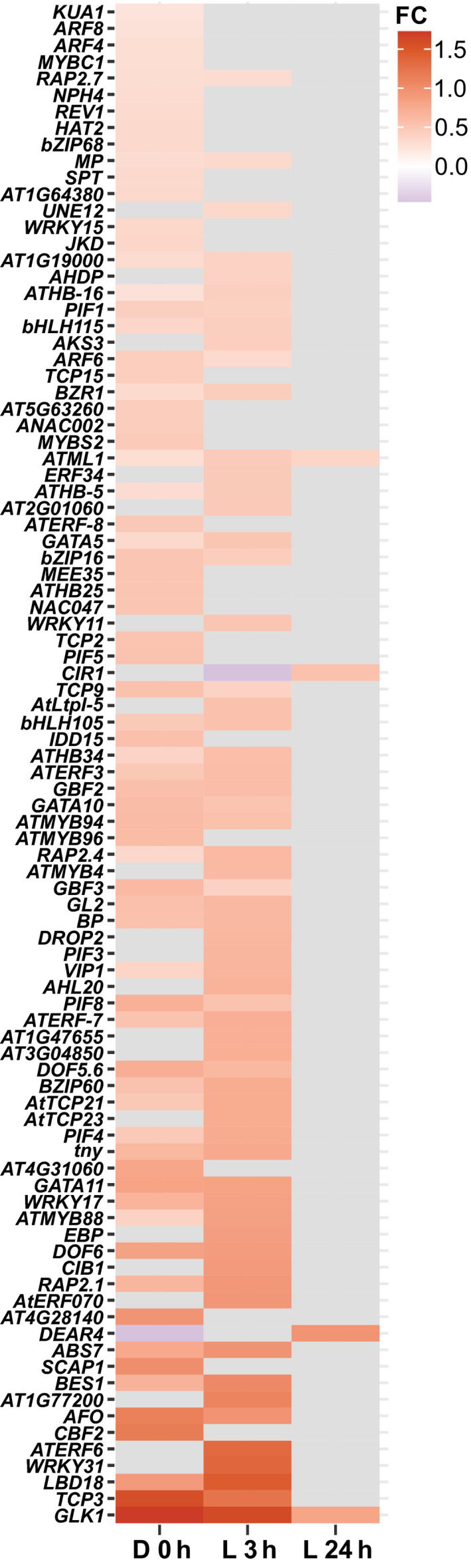

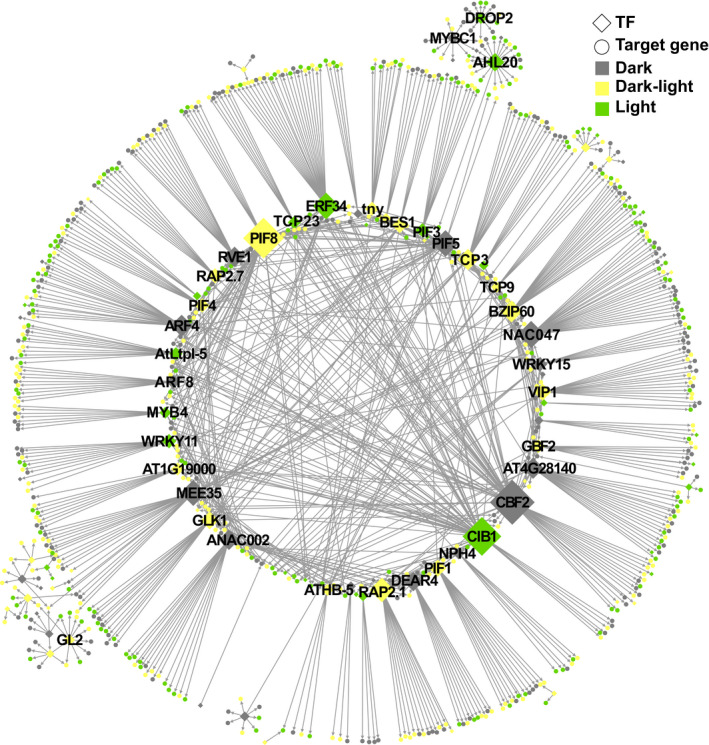

Gene regulatory network for upregulated transcription factors in gun1‐102

Since the GUN1‐dependent retrograde signal is mainly known to repress nuclear gene expression and there were a high number of TFs associated with early seedling development in the group of upregulated TFs in gun1‐102, we focused our efforts on these transcriptional regulators. To assess whether these TFs could be involved in the GUN1 regulation and play a role in the GUN1‐dependent retrograde signal we used TF2Network (Kulkarni et al., 2018) and found 92 upregulated TFs in gun1‐102 that potentially regulate the DEGs (Fig. 6). After the removal of negative coexpression values, we obtained a GRN with 835 nodes, 1043 regulatory interactions, and 79 upregulated TFs that had at least one putative binding site in promoters of the gun1‐102 DEGs (Table S7). To help visualize the most connected TFs, we represented the GRN using a radial layout (Fig. 7). Among the most interconnected TFs in the inner circle were some of the TFs linked to photomorphogenesis mentioned earlier, like the PIFs, BES1, and GLK1. Many of the genes encoding these TFs were upregulated in both dark and light conditions in gun1‐102 (BES1, GLK1, PIF1, 4, and 8). When we compared the top 10 upregulated TFs in gun1‐102 with the top 10 most interconnected, we found three TFs: C‐REPEAT BINDING FACTOR 2 (CBF2), RELATED TO AP2 1 (RAP2.1), and CRYPTOCHROME‐INTERACTING BASIC‐HELIX‐LOOP‐HELIX 1 (CIB1) (Figs 6, 7, S11). None of these TFs have been directly linked to plastid signals during chloroplast development. CBF2, upregulated in etiolated gun1‐102 seedlings, is a major regulator of cold acclimation, and among its downstream genes there are chloroplast proteins involved in thylakoid membrane protection that were deregulated in the gun1‐102 D 0 h sample (e.g. COLD REGULATED 314 THYLAKOID MEMBRANE 2). Although a role for the CBFs in etiolated seedlings has not been reported, earlier work has revealed that the CBFs are regulated by plastid signals (Norén et al., 2016). RAP2.1, which was found to be upregulated in D 0 h and L 3 h, has been described as a repressor of abiotic stress responses regulating the expression of response genes like some COLD REGULATED genes (Dong & Liu, 2010). CIB1, upregulated only in L 3 h, is involved in flowering in response to blue light by interacting with CRYPTOCHROME 2 and CONSTANS (Liu et al., 2018). Taken together, our results from the RNA‐Seq analysis strongly indicate that the GUN1 retrograde signal regulates a large number of TFs, beyond the already described GLK1, to control nuclear gene expression before the onset of light and during the first hours of light response.

Fig. 6.

Upregulated transcription factors in Arabidopsis gun1‐102. Heatmap of the 92 upregulated transcription factors in gun1‐102 with potential targets among the differentially expressed genes according to TF2Network. FC, fold change.

Fig. 7.

Gene regulatory network representation of predicted regulatory interactions of 92 upregulated Arabidopsis transcription factors (TFs) and their respective differentially expressed gene (DEG) targets are represented. Positive coexpression values and motifs overrepresented on promoters of target DEGs were considered to create regulatory interactions. Only the main connected component is represented. Sizes of TF nodes are proportional to the number of connections. A file with the network information is available in Supporting Information Table S7.

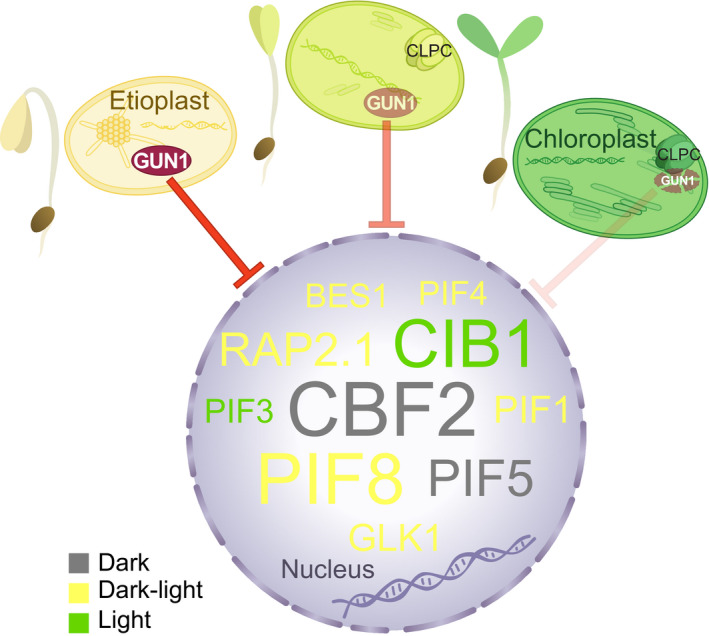

Discussion

Emerging from darkness is a dangerous task for seedlings, as the levels of Chl‐binding proteins and Chl intermediates must be carefully controlled to provide sufficient material to build the photosynthetic machinery, while avoiding a lethal oxidative burst that results from the overaccumulation of these components when the seedling is exposed to light (op den Camp et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017). We herein show that plastids play a major part in controlling this dangerous process through a negative GUN1‐mediated retrograde signal that restricts chloroplast development by regulating the transcription of several critical TFs linked to light response, photomorphogenesis, and chloroplast development, and consequently their downstream target genes (Fig. 8). Based on our data, we present a model where the GUN1‐mediated retrograde signal is active before light‐triggered chloroplast biogenesis and without any plastid impairment. We found GUN1 (1) to be present in the dark, (2) to control expression of transcriptional regulators, which further (3) affect the expression of downstream photosynthesis‐related genes in both seedlings and in cell lines mimicking meristematic cells, and (4) prevent premature chloroplast development and seedling damage. Our results strongly indicate that GUN1 has a protective role and is clearly active before the transition to photoautotrophy in response to light.

Fig. 8.

Working model for GENOMES UNCOUPLED1 (GUN1) during chloroplast biogenesis in Arabidopsis. GUN1 is present in proplastids and etioplasts giving rise to a retrograde signal that regulates a large number of critical transcription factors (TFs) linked to light response, photomorphogenesis, and chloroplast development, and consequently their downstream genes. As the light response proceeds, GUN1 levels decrease through degradation by the chloroplast chaperone CLPC, the regulation of TFs and their downstream genes is released, transcription of photosynthesis‐associated nuclear genes is boosted and the establishment of fully functional chloroplasts is achieved. In the nucleus are depicted representative GUN1‐repressed TFs only in etiolated seedlings (grey), in etiolated and de‐etiolated seedlings (yellow), or only in de‐etiolated seedlings (green). Sizes of TFs are relative to the amount of connections in the gene regulatory network (Fig. 7; Supporting Information Table S7). BES1, BRI1‐EMS‐SUPPRESSOR 1; CBF2, C‐REPEAT BINDING FACTOR 2; CIB1, CRYPTOCHROME‐INTERACTING BASIC‐HELIX‐LOOP‐HELIX 1; GLK1, GOLDEN2‐LIKE 1; PIF, PHYTOCHROME‐INTERACTING FACTOR; RAP2.1, RELATED TO AP2 1.

In darkness, a complex network of transcriptional regulators, such as the PIFs, EIN3/EIL1, BZR1/BES1, and DELLA proteins, repress chloroplast development and photomorphogenesis (Hernández‐Verdeja et al., 2020). Light activation of phytochromes lifts this repression and generates an induction of the GLK genes and stabilization of the TF HY5, leading to the first nuclear transcriptional changes that give rise to chloroplast development and de‐etiolation (Jiao et al., 2007; Leivar & Monte, 2014). In response to plastid stress, the GUN1 retrograde signal antagonizes the light signalling pathway and converges on GLK1 (Martín et al., 2016). We show here that GUN1 controls the expression of PIFs (PIF1, 4, 5), BZR1 and BES1, and GLK1 in etiolated seedlings (Figs 2a,b, 6, 7). At the critical stage of the initial light‐induced transcriptional activation, GUN1 is still present, repressing several PIFs (PIF1, 3, 4, and 8), BRZ1, BES1, and GLK1, and promoting HY5 expression (Figs 2a,b, 6, 7, S10). As chloroplast development progresses and the potential risk of oxidative damage decreases, GUN1 is degraded and is shown to reach a minimum at 24 h, when the chloroplasts are functional (Wu et al., 2018). The reduced GUN1 levels lifts the negative plastid regulation of nuclear expression and allows for full expression of the PhANGs (Fig. 8).

Despite the large effect on gene expression, the gun1 mutants do not demonstrate a constitutive photomorphogenic phenotype in the dark, similar to the well‐characterized cop and det mutants (Wei & Deng, 1996). In addition to the massive transcriptional changes, the transition from dark to light also results in a global increase in translational activity, with an altered translation of about one‐third of all transcripts (Liu et al., 2012). Moreover, reduced translation in the dark of specific photomorphogenic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) has been linked to processing bodies, which regulate decay or translational arrest of the specific mRNAs (Jang et al., 2019). Many components of the repressive network and their downstream genes controlled by GUN1 are under strict posttranscriptional regulation in the dark (Hernández‐Verdeja et al., 2020), and the increased expression observed in gun1 may not correlate with an increase in the proteins required to enter photomorphogenesis. Thus, translational activity appears to be regulated by light‐controlled mechanisms that are, to a large extent, independent of GUN1. However, our proposed model for GUN1 could account for the subtle phenotype of gun1 mutants, with higher Pchlide accumulation in etiolated seedlings and lower survival rates when etiolated seedlings are exposed to light (Fig. S13) (Susek et al., 1993; Xu et al., 2016; Shimizu et al., 2019). Our model could explain the second plastid‐dependent increase of nuclear transcription required for the final establishment of photosynthesis (Dubreuil et al., 2018; Armarego‐Marriott et al., 2019), and once chloroplast development has reached a critical point, GUN1 is degraded (Figs 2, S5, S6) and transcription of the PhANGs is boosted to achieve fully functional chloroplasts.

By using artificial stress conditions, such as norflurazon and lincomycin, GUN1 has been assigned a role in communicating stress conditions in the plastids to the nucleus. Our results support that GUN1 relays the lincomycin‐dependent retrograde signal also in the dark and that this signal represses PhANG expression mainly through GLK1, which is common to all transcriptomics profiles (Figs 5, S8, S12). However, the small overlaps between the transcriptomics data suggest that GUN1 and lincomycin independently regulate specific gene sets. Although the experimental conditions for the transcriptomics analysis that were compared are somewhat different, three different available datasets for lincomycin‐treated seedlings provided similar results for the overlap between GUN1 in the dark and following growth on lincomycin, which support the hypothesis of convergent and divergent signalling pathways for GUN1 and lincomycin. Our data strongly indicate that the inhibitors traditionally used to study retrograde signals lock the seedlings in the developmental state prevailing in darkness by stabilizing GUN1 and repressing PhANGs. This is supported by recent reports indicating that GUN1 is important to maintain nuclear encoded polymerase activity for the transcriptional adaptive response (Δrpo phenotype) upon plastid impairment, promoting the transcriptional activity that prevails in nondeveloped plastids (Loudya et al., 2020; Tadini et al., 2020a). Any interference with plastid development, such as the conditions used in the mutant screen where gun1 was identified (Susek et al., 1993), will inhibit GUN1 degradation (Figs 5, S8) (Wu et al., 2018), nuclear gene expression will remain repressed, and chloroplast development will not proceed (Dubreuil et al., 2018).

Our data from the roots revealed a novel feature of GUN1 that could further support the role of GUN1 in maintaining nonphotosynthetic plastid types. Plastids in the roots develop into colourless nonphotosynthetic forms, generally termed leucoplasts, and GUN1 was found in the leucoplasts at high levels irrespective of light conditions (Figs 2c,d, S5c,d). These results indicate that GUN1 degradation is dependent on normal progression of plastid‐to‐chloroplast development. This opens the question on organ‐specific GUN1 function and the regulation of GUN1 degradation. Plastid retrograde signals have been shown to be active in roots, and at least the signals originated in response to defects in plastid translation are mediated by GUN1 and have effects on root development (Sullivan & Gray, 1999; Garnik et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020).

We demonstrate here that a true physiological function of GUN1 is to suppress expression of PhANGs in the dark and to protect the seedling during emergence from the soil by fine‐tuning nuclear gene expression. Furthermore, the sustained accumulation of the GUN1 protein in the root tissue suggests that the regulatory mechanism behind the dynamics of GUN1 levels is only present in tissues that are normally exposed to light and have photosynthetic activity. Thus, not only does GUN1 act as a safeguard during the critical step of seedling emergence from darkness, GUN1 could also contribute to the organ‐specific control of PhANG expression and chloroplast development.

Author contributions

TH‐V, LV, and ÅS conceptualized the research, analysed data, and wrote the paper. TH‐V, LV, XJ, AV, and CD performed the experiments. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Volcano plots showing the selection of significant DEGs.

Fig. S2 GUN1:YFP and GUN1 silencing in Arabidopsis cell culture.

Fig. S3 Complementation analysis of gun1 mutants with PGUN1:GUN1:YFP.

Fig. S4 GUN1:YFP fluorescence and gene expression in etiolated and de‐etiolated gun1 GUN1:YFP seedlings.

Fig. S5 GUN1:YFP in dark‐grown and light‐exposed gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP #6.3.6 seedlings.

Fig. S6 Immunoblot analysis of GUN1:YFP during the greening process.

Fig. S7 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of deregulated genes in gun1‐102.

Fig. S8 GUN1:YFP response to lincomycin and comparison of de‐etiolated gun1‐102 DEGs with gun1 or WT seedlings treated with lincomycin.

Fig. S9 Comparison of gun1‐102 upregulated genes with GLK‐induced genes.

Fig. S10 Functional analysis of deregulated transcription factors in gun1‐102.

Fig. S11 Expression levels from the RNA‐Seq replicates and qPCR validation for selected transcription factors.

Fig. S12 Transcription factors involved in photomorphogenesis deregulated in gun1‐102 compared with lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Fig. S13 Greening rate, survival, and Pchlide accumulation of etiolated gun1 seedlings.

Methods S1 Protein extraction, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting.

Table S1 Oligonucleotide sequences of primers used in this study.

Table S2 RNA‐Seq reads filtering summary.

Table S3 Differential expressed genes with raw values of filter parameters.

Table S4 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of DEGs.

Table S5 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of commons DEGs of gun1‐102 and lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Table S6 GLK targets in common DEGs of gun1‐102 and lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Table S7 GRN topology data and outgoing neighbours.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Foundation (2020‐03958) to VR and the Foundation for Strategic Research (ARC19‐0051) to ÅS. We would like to thank the UPSC Bioinformatics Facility for support with the data handling and computing.

Contributor Information

Tamara Hernández‐Verdeja, Email: t.hernandez-verdeja@lancaster.ac.uk.

Åsa Strand, Email: asa.strand@umu.se.

Data availability

Sequencing data and a description of samples are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) as accession no. PRJEB47885.

References

- Alabadí D, Gallego‐Bartolomé J, Orlando L, García‐Cárcel L, Rubio V, Martínez C, Frigerio M, Iglesias‐Pedraz JM, Espinosa A, Deng XW et al. 2008. Gibberellins modulate light signaling pathways to prevent Arabidopsis seedling de‐etiolation in darkness. The Plant Journal 53: 324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armarego‐Marriott T, Kowalewska Ł, Burgos A, Fischer A, Thiele W, Erban A, Strand D, Kahlau S, Hertle A, Kopka J et al. 2019. Highly resolved systems biology to dissect the etioplast‐to‐chloroplast transition in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiology 180: 654–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armarego‐Marriott T, Sandoval‐Ibañez O, Kowalewska Ł. 2020. Beyond the darkness: recent lessons from etiolation and de‐etiolation studies. Journal of Experimental Botany 71: 1215–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo‐Davis CI, Hartl DL. 2003. GeneMerge – post‐genomic analysis, data mining, and hypothesis testing. Bioinformatics 19: 891–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheminant S, Wild M, Bouvier F, Pelletier S, Renou J, Erhardt M, Hayes S, Terry MJ, Genschik P, Achard P. 2011. DELLAs regulate chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis to prevent photooxidative damage during seedling deetiolation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1849–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen Y, Shi C, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Li S, Li Y, Ye J, Yu C, Li Z et al. 2018. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration‐supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high‐throughput sequencing data. GigaScience 7: gix120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. 1998. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottage A, Mott EK, Kempster JA, Gray JC. 2010. The Arabidopsis plastid‐signalling mutant gun1 (genomes uncoupled1) shows altered sensitivity to sucrose and abscisic acid and alterations in early seedling development. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 3773–3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. 2003. A Gateway cloning vector set for high‐throughput functional analysis of genes in planta . Plant Physiology 133: 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel L, Gläßer C, Liebers M, Hiekel S, Courtois F, Czarnecki O, Schlicke H, Zubo Y, Börner T, Mayer K et al. 2015. Identification of early nuclear target genes of plastidial redox signals that trigger the long‐term response of Arabidopsis to light quality shifts. Molecular Plant 8: 1237–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CJ, Liu JY. 2010. The Arabidopsis EAR‐motif‐containing protein RAP2.1 functions as an active transcriptional repressor to keep stress responses under tight control. BMC Plant Biology 10: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil C, Jin XU, de Dios Barajas‐López J, Hewitt TC, Tanz SK, Dobrenel T, Schröder WP, Hanson J, Pesquet E, Grönlund A et al. 2018. Establishment of photosynthesis through chloroplast development is controlled by two distinct regulatory phases. Plant Physiology 176: 1199–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristedt R, Williams‐Carrier R, Merchant SS, Barkan A. 2014. A thylakoid membrane protein harboring a DnaJ‐type zinc finger domain is required for photosystem I accumulation in plants. Journal of Biological Chemistry 289: 30657–30667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnik EY, Tarasenko VI, Gorbunova AI, Shmakov VN, Konstantinov YM. 2019. Genome uncoupled (gun) phenotype is associated with root growth repression in Arabidopsis seedlings grown on lincomycin. Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology 31: 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández‐Verdeja T, Strand Å. 2018. Retrograde signals navigate the path to chloroplast development. Plant Physiology 176: 967–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández‐Verdeja T, Vuorijoki L, Strand Å. 2020. Emerging from the darkness: interplay between light and plastid signalling during chloroplast biogenesis. Physiologia Plantarum 169: 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper CM, Castleden IR, Tanz SK, Aryamanesh N, Millar AH. 2017. SUBA4: the interactive data analysis centre for Arabidopsis subcellular protein locations. Nucleic Acids Research 45: D1064–D1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang G‐J, Yang J‐Y, Hsieh H‐L, Wu S‐H. 2019. Processing bodies control the selective translation for optimal development of Arabidopsis young seedlings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 116: 6451–6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Lau OS, Deng XW. 2007. Light‐regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nature Reviews Genetics 8: 207–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Ma L, Strickland E, Deng XW. 2005. Conservation and divergence of light‐regulated genome expression patterns during seedling development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 3239–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Zhang H, Kong L, Gao G, Luo J. 2014. PlantTFDB 3.0: a portal for the functional and evolutionary study of plant transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Research 42: 1182–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizaki T, Matsumura H, Nakayama K, Che FSF‐S, Terauchi R, Inaba T, Oa RSW, Kakizaki T, Matsumura H, Nakayama K et al. 2009. Coordination of plastid protein import and nuclear gene expression by plastid‐to‐nucleus retrograde signaling. Plant Physiology 151: 1339–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindgren P, Kremnev D, Blanco NE, de Dios Barajas‐López J, Fernández AP, Tellgren‐Roth C, Small I, Strand Å. 2012. The plastid redox insensitive 2 mutant of Arabidopsis is impaired in PEP activity and high light‐dependent plastid redox signalling to the nucleus. The Plant Journal 70: 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koussevitzky S, Nott A, Mockler TC, Hong F, Sachetto‐Martins G, Surpin M, Lim J, Mittler R, Chory J. 2007. Signals from chloroplasts converge to regulate nuclear gene expression. Science 316: 715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SR, Vaneechoutte D, Van De VJ, Vandepoele K. 2018. TF2Network: predicting transcription factor regulators and gene regulatory networks in Arabidopsis using publicly available binding site information. Nucleic Acids Research 46: e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped‐read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E. 2014. PIFs: systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell 26: 56–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN. 2011. Rsem: accurate transcript quantification from RNA‐Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12: e323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Ma J, Sun X, Zhao C, Ma C, Wang X. 2020. RAB GTPASE HOMOLOG 8D is required for maintenance of both the root stem cell niche and meristem. The Plant Journal 105: 1225–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MJ, Wu SH, Chen H‐M, Wu S‐H. 2012. Widespread translational control contributes to the regulation of Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. Molecular Systems Biology 8: 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Liu R, Li Y, Shen X, Zhong S, Shi H. 2017. EIN3 and PIF3 form an interdependent module that represses chloroplast development in buried seedlings. Plant Cell 29: 3051–3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li X, Ma D, Chen Z, Wang J, Liu H. 2018. CIB1 and CO interact to mediate CRY2‐dependent regulation of flowering. EMBO Reports 19: e45762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas E, Pulido P, Rodriguez‐Concepcion M. 2017. Interference with plastome gene expression and Clp protease activity in Arabidopsis triggers a chloroplast unfolded protein response to restore protein homeostasis. PLoS Genetics 13: e1007022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudya N, Okunola T, He J, Jarvis P, López‐Juez E. 2020. Retrograde signalling in a virescent mutant triggers an anterograde delay of chloroplast biogenesis that requires GUN1 and is essential for survival. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 375: e20190400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA‐seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 15: e550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiafico S. 2019. rcompanion: functions to support extension education program evaluation. R package v.2.3.25. [WWW document] URL https://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=rcompanion [accessed 1 February 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Naranjo B, Wang J, Penzler JF, Kleine T, Leister D. 2019. Relationship of GUN1 to FUG1 in chloroplast protein homeostasis. The Plant Journal 99: 521–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín G, Leivar P, Ludevid D, Tepperman JM, Quail PH, Monte E. 2016. Phytochrome and retrograde signalling pathways converge to antagonistically regulate a light‐induced transcriptional network. Nature Communications 7: e11431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni F, Wu L, Wang Q, Hong J, Qi Y, Zhou X. 2017. Turnip yellow mosaic virus P69 interacts with and suppresses GLK transcription factors to cause pale‐green symptoms in Arabidopsis . Molecular Plant 10: 764–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norén L, Kindgren P, Stachula P, Rühl M, Eriksson ME, Hurry V, Strand Å. 2016. Circadian and plastid signaling pathways are integrated to ensure correct expression of the CBF and COR genes during photoperiodic growth. Plant Physiology 171: 1392–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle DH, Wheeler P, Dinno A. 2019. fsa: fisheries stock analysis. R package v.0.8.30. [WWW document] URL https://github.com/droglenc/FSA [accessed 1 February 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Zhu J‐Y, Wang Z‐Y. 2012. Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nature Cell Biology 14: 802–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveros JC. 2015. Venny. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams. [WWW document] URL https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html [accessed 19 August 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- op den Camp RG, Przybyla D, Ochsenbein C, Laloi C, Kim C, Danon A, Wagner D, Hideg É, Göbel C, Feussner I et al. 2013. Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 2320–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Zhao J, Neff MM. 2015. ATAF2 integrates Arabidopsis brassinosteroid inactivation and seedling photomorphogenesis. Development 142: 4129–4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesquet E, Korolev AV, Calder G, Lloyd CW, Centre JI, Lane C. 2010. The microtubule‐associated protein AtMAP70‐5 regulates secondary wall patterning in Arabidopsis wood cells. Current Biology 20: 744–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham VN, Kathare PK, Huq E. 2018. Phytochromes and phytochrome interacting factors. Plant Physiology 176: 1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [WWW document] URL https://www.R‐project.org/ [accessed 1 February 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Lekanne Deprez RH, Moorman AFM. 2003. Assumption‐free analysis of quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neuroscience Letters 339: 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter AS, Tohge T, Fernie AR, Grimm B. 2020. The genomes uncoupled ‐dependent signalling pathway coordinates plastid biogenesis with the synthesis of anthocyanins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 375: e20190403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team . 2016. RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston, MA, USA: RStudio. [WWW document] URL http://www.rstudio.com/ [accessed 1 February 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckle ME, Larkin RM. 2009. Plastid signals that affect photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana are dependent on GENOMES UNCOUPLED 1 and cryptochrome 1. New Phytologist 182: 367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda‐Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B et al. 2012. Fiji: an open‐source platform for biological‐image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Steinberger I, Strissel H, Kunz HH, Manavski N, Meurer J, Burkhard G, Jarzombski S, Schünemann D, Geimer S et al. 2014. The Arabidopsis Tellurite resistance C protein together with ALB3 is involved in photosystem II protein synthesis. The Plant Journal 78: 344–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seluzicki A, Burko Y, Chory J. 2017. Dancing in the dark: darkness as a signal in plants. Plant, Cell & Environment 40: 2487–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikhali J, Norén L, de Dios Barajas‐López J, Srivastava V, König J, Sauer UH, Wingsle G, Dietz KJ, Strand Å. 2012. Redox‐mediated mechanisms regulate DNA binding activity of the G‐group of basic region leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Journal of Biological Chemistry 287: 27510–27525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. 2003. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research 13: 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Kacprzak SM, Mochizuki N, Nagatani A, Watanabe S, Shimada T, Tanaka K, Hayashi Y, Arai M, Leister D et al. 2019. The retrograde signaling protein GUN1 regulates tetrapyrrole biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 116: 24900–24906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J, Gray J. 1999. Plastid translation is required for the expression of nuclear photosynthesis genes in the dark and in roots of the pea lip1 mutant. Plant Cell 11: 901–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Feng P, Xu X, Guo H, Ma J, Chi W, Lin R, Lu C, Zhang L. 2011. A chloroplast envelope‐bound PHD transcription factor mediates chloroplast signals to the nucleus. Nature Communications 2: e477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. 2011. Revigo summarizes and visualizes long lists of Gene Ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6: e21800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susek RE, Ausubel FM, Chory J. 1993. Signal‐transduction mutants of Arabidopsis uncouple nuclear CAB and RBCS gene‐expression from chloroplast development. Cell 74: 787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadini L, Jeran N, Peracchio C, Masiero S, Colombo M, Pesaresi P. 2020a. The plastid transcription machinery and its coordination with the expression of nuclear genome: plastid‐encoded polymerase, nuclear‐encoded polymerase and the Genomes Uncoupled 1‐mediated retrograde communication. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 375: e20190399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadini L, Peracchio C, Trotta A, Colombo M, Mancini I, Jeran N, Costa A, Faoro F, Marsoni M, Vannini C et al. 2020b. GUN1 influences the accumulation of NEP‐dependent transcripts and chloroplast protein import in Arabidopsis cotyledons upon perturbation of chloroplast protein homeostasis. The Plant Journal 101: 1198–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadini L, Pesaresi P, Kleine T, Rossi F, Guljamow A, Sommer F, Mühlhaus T, Schroda M, Masiero S, Pribil M et al. 2016. GUN1 controls accumulation of the plastid ribosomal protein S1 at the protein level and interacts with proteins involved in plastid protein homeostasis. Plant Physiology 170: 1817–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai H, Iwabuchi M, Meshi T. 2002. Arabidopsis GARP transcriptional activators interact with the Pro‐rich activation domain shared by G‐box‐binding bZIP factors. Plant and Cell Physiology 43: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa K, Sato N. 2005. Visualization of plastid nucleoids in situ using the PEND‐GFP fusion protein. Plant and Cell Physiology 46: 649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumaru M, Adachi F, Toda M, Ito‐Inaba Y, Yazu F, Hirosawa Y, Sakakibara Y, Suiko M, Kakizaki T, Inaba T. 2017. Ubiquitin–proteasome dependent regulation of the GOLDEN2‐LIKE 1 transcription factor in response to plastid signals. Plant Physiology 173: 524–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Wang P, Korkaric M, Capper RG, Saunders NJ, Langdale JA. 2009. GLK transcription factors coordinate expression of the photosynthetic apparatus in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 21: 1109–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N, Deng XW. 1996. The role of the COP/DET/FUS genes in light control of Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant Physiology 112: 871–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, NY, USA: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson JD, Perez‐Perez J, Schmitz RJ, Ecker JR, Chory J. 2013. Sigma factor‐mediated plastid retrograde signals control nuclear gene expression. The Plant Journal 73: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G‐Z, Chalvin C, Hoelscher MP, Meyer EH, Wu XN, Bock R. 2018. Control of retrograde signaling by rapid turnover of GENOMES UNCOUPLED 1. Plant Physiology 176: 2472–2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G‐Z, Meyer EH, Richter AS, Schuster M, Ling Q, Schöttler MA, Walther D, Zoschke R, Grimm B, Jarvis RP et al. 2019a. Control of retrograde signalling by protein import and cytosolic folding stress. Nature Plants 5: 525–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G‐Z, Meyer EH, Wu S, Bock R. 2019b. Extensive posttranscriptional regulation of nuclear gene expression by plastid retrograde signals. Plant Physiology 180: 2034–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D. 2020. COP1 and BBXs‐HY5‐mediated light signal transduction in plants. New Phytologist 228: 1748–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chi W, Sun X, Feng P, Guo H, Li J, Lin R, Lu C, Wang H, Leister D et al. 2016. Convergence of light and chloroplast signals for de‐etiolation through ABI4–HY5 and COP1. Nature Plants 2: e16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Kubo M, Fukuda H, Demura T. 2008. VASCULAR‐RELATED NAC‐DOMAIN7 is involved in the differentiation of all types of xylem vessels in Arabidopsis roots and shoots. The Plant Journal 55: 652–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EJ, Yoo CY, Liu J, Wang HE, Cao J, Li F‐W, Pryer KM, Sun T‐P, Weigel D, Zhou P et al. 2019. NCP activates chloroplast transcription by controlling phytochrome‐dependent dual nuclear and plastidial switches. Nature Communications 10: e2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo CY, Pasoreck EK, Wang H, Cao J, Blaha GM, Weigel D, Chen M. 2019. Phytochrome activates the plastid‐encoded RNA polymerase for chloroplast biogenesis via nucleus‐to‐plastid signaling. Nature Communications 10: e2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Li L, Zola J, Aluru M, Ye H, Foudree A, Guo H, Anderson S, Aluru S, Liu P et al. 2011. A brassinosteroid transcriptional network revealed by genome‐wide identification of BESI target genes in Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal 65: 634–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Huang J, Chory J. 2019. GUN1 interacts with MORF2 to regulate plastid RNA editing during retrograde signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 116: 10162–10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Zhao M, Shi T, Shi H, An F, Zhao Q, Guo H. 2009. EIN3/EIL1 cooperate with PIF1 to prevent photo‐oxidation and to promote greening of Arabidopsis seedlings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106: 21431–21436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Volcano plots showing the selection of significant DEGs.

Fig. S2 GUN1:YFP and GUN1 silencing in Arabidopsis cell culture.

Fig. S3 Complementation analysis of gun1 mutants with PGUN1:GUN1:YFP.

Fig. S4 GUN1:YFP fluorescence and gene expression in etiolated and de‐etiolated gun1 GUN1:YFP seedlings.

Fig. S5 GUN1:YFP in dark‐grown and light‐exposed gun1‐103 GUN1:YFP #6.3.6 seedlings.

Fig. S6 Immunoblot analysis of GUN1:YFP during the greening process.

Fig. S7 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of deregulated genes in gun1‐102.

Fig. S8 GUN1:YFP response to lincomycin and comparison of de‐etiolated gun1‐102 DEGs with gun1 or WT seedlings treated with lincomycin.

Fig. S9 Comparison of gun1‐102 upregulated genes with GLK‐induced genes.

Fig. S10 Functional analysis of deregulated transcription factors in gun1‐102.

Fig. S11 Expression levels from the RNA‐Seq replicates and qPCR validation for selected transcription factors.

Fig. S12 Transcription factors involved in photomorphogenesis deregulated in gun1‐102 compared with lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Fig. S13 Greening rate, survival, and Pchlide accumulation of etiolated gun1 seedlings.

Methods S1 Protein extraction, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting.

Table S1 Oligonucleotide sequences of primers used in this study.

Table S2 RNA‐Seq reads filtering summary.

Table S3 Differential expressed genes with raw values of filter parameters.

Table S4 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of DEGs.

Table S5 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of commons DEGs of gun1‐102 and lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Table S6 GLK targets in common DEGs of gun1‐102 and lincomycin transcriptomic data.

Table S7 GRN topology data and outgoing neighbours.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Data Availability Statement