Abstract

Multitarget datasets that correlate bioactivity landscapes of small-molecules toward different related or unrelated pharmacological targets are crucial for novel drug design and discovery. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are critical membrane-bound transport proteins that impact drug and metabolite distribution in human disease as well as disease diagnosis and therapy. Molecular-structural patterns are of the highest importance for the drug discovery process as demonstrated by the novel drug discovery tool ‘computer-aided pattern analysis’ (‘C@PA’). Here, we report a multitarget dataset of 1,167 ABC transporter inhibitors analyzed for 604 molecular substructures in a statistical binary pattern distribution scheme. This binary pattern multitarget dataset (ABC_BPMDS) can be utilized for various areas. These areas include the intended design of (i) polypharmacological agents, (ii) highly potent and selective ABC transporter-targeting agents, but also (iii) agents that avoid clearance by the focused ABC transporters [e.g., at the blood-brain barrier (BBB)]. The information provided will not only facilitate novel drug prediction and discovery of ABC transporter-targeting agents, but also drug design in general in terms of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

Subject terms: Drug discovery and development, Chemical biology

| Measurement(s) | Influx • Efflux • Tracer • Transport velocity |

| Technology Type(s) | Fluorometry • Radioactivity • Plate reader • Flow cytometer • Tracer distribution |

| Factor Type(s) | half-maximal inhibition concentration |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Homo sapiens |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | cell culture |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Kingdom of Norway • Germany • Australia • Latvia |

Background & Summary

The superfamily of ABC transporters is of highest importance in terms of novel drug discovery, design, and development. ABC transporters are ubiquitously present in the human body1–4, and their (co-)expression has broad implications in human diseases. These diseases include prevalent [e.g., Alzheimer’s disease (AD)5,6, atherosclerosis7, or cancer1,3,6,8] and orphan [e.g., Tangier disease (ABCA1)9, Stargardt’s disease (ABCA4)10, harlequin ichthyosis (ABCA12)11, pseudoxanthoma elasticum (ABCC6)12, or adrenoleukodystrophy (ABCD1)13] pathological conditions. Together with tight-junction proteins, these membrane-bound efflux pumps are the backbone of systemic barrier formation14,15. Their localization at blood-tissue barriers impacts metabolite distribution and drug delivery, and hence, disease progress, treatment, and therapy15–19. Determinants that establish a correlation between the molecular structure of a small-molecule (drug) and its interaction with ABC transporters is key for the development of novel, safe, systemically applicable, and target-oriented (selective) drugs.

These determinants include descriptors that conserve certain physicochemical features of the small-molecules of interest, such as the calculated octanol-water partition coefficient (CLogP), molecular weight (MW), molar refractivity (MR), or topological polar surface area (TPSA), but also the number of hydrogen bond (H-bond) donors, H-bond acceptors, or rotatable bonds5. Other than that, more complex attributes can be summarized in fingerprints that represent certain molecular features of the small-molecule in a binary code (e.g., feature-, path-, and radial-fingerprints20–22). Unfortunately, comprehensive binary datasets do not exist for ABC transporters. However, the knowledge about such binary fingerprints could facilitate the development of (i) drugs that avoid clearance mediated by ABC transporters [e.g., targeting the BBB to treat central nervous system-(CNS)-related diseases23]; (ii) agents targeting ABC transporters to study their expression and/or function with state-of-the-art imaging techniques [e.g., by positron emission tomography (PET)16]; (iii) drugs that selectively target well-studied ABC transporters in human diseases (e.g., cancer1,3,4,6,8); (iv) broad-spectrum drugs that target several ABC transporters to ameliorate/cure an ABC transporter-associated pathological condition24; (v) polypharmacological agents to target and study particularly less- and under-studied ABC transporters by a multitargeting approach7,25–27; or (vi) combined/extended fingerprints to create high-quality compound collections that would provide a starting point of polypharmacology-focused virtual screenings7.

In the present work, we combined the concepts of the multitarget dataset7,27 and the binary distribution of substructures7. The latest version of the multitarget dataset contains 1,167 compounds that were evaluated against the well-studied ABC transporters ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2. A large substructure catalog was created, containing in total 604 active (= present) substructures within these 1,167 compounds of the updated multitarget dataset. The new binary pattern multitarget dataset (ABC_BPMDS) is freely available under the http://www.zenodo.org28 URL as well as the http://www.panabc.info website, and its use is free of charge.

Methods

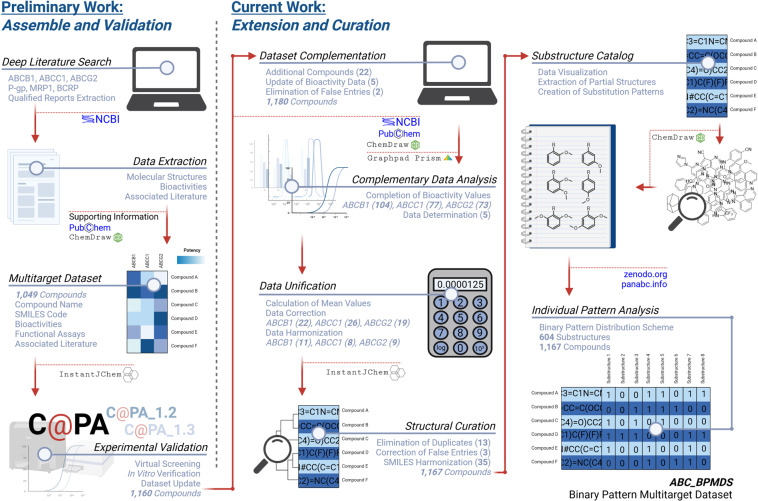

The generation of the ABC_BPMDS was a four-step process: (i) deep literature search including the selection of qualified reports, resulting in the exquisite compilation of the original multitarget dataset as reported earlier27 [including updates in our former7 and the present work (see below)]; (ii) manual curation of the given data, in particular: (a) calculation of bioactivity values for estimated bioactivity data and data determination, (b) unification and harmonization of bioactivity data, as well as (c) comparison, curation, and harmonization of molecular-structural data (SMILES codes); (iii) generation of a substructure catalog, in particular: (a) visual inspection of the 1,167 molecules of the updated multitarget dataset, (b) extraction of partial structures, (c) creation and extension of substitution patterns, as well as (d) screening of the multitarget dataset for these substructures, discovering 604 active substructures; and (iv) individual pattern analysis7 for uncovering the statistical distribution of these 604 active substructures amongst the 1,167 compounds of the multitarget dataset. The following sections will provide a detailed description on how the final ABC_BPMDS was assembled. Figure 1 provides an overview of the taken steps.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of the main workflow of assemble and validation as reported earlier in our preliminary work27, as well as the main steps of data extension and curation as part of the current work to generate the ABC_BPMDS. This graphic was created with BioRender.com (https://biorender.com).

Literature Collection of the Original Dataset

Qualified Reports

A deep literature search was the first step to compile the original multitarget dataset, which has been reported in detail before7,27. The National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)29 was used to search for qualified reports applying the keywords (i) ‘ABCB1’, (ii) ‘ABCC1’, (iii) ‘ABCG2’, (iv) ‘P-gp’, (v) ‘MRP1’, and (vi) ‘BCRP’. The keywords were used in all possible combinations to extract the maximal yield in reports. In addition to the genuine database search, the reference sections of the found reports were searched for potential additional literature to extract further qualified information.

Compounds

Compounds were considered only if they had been evaluated against all three focused targets, ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2, including inactive compounds as well as selective, dual, and triple inhibitors. This information could be provided either in one single report (e.g., in case of the standard ABCG2 inhibitor Ko14330) or in several individual reports [e.g., in case of the standard ABCC1 inhibitor verlukast (MK571)31–36]. The molecular structures of qualified compounds were collected as SMILES codes. These were obtained either from (i) supplementary information of the respective report; (ii) the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)37 [e.g., in case of known drugs and drug-like compounds, such as the standard inhibitors verapamil (ABCB1), cyclosporine A (ABCB1 and ABCC1), verlukast (ABCC1), or Ko143 (ABCG2)]; or (iii) manual drawing according to the 2D representations as outlined in the respective report using ChemDraw Pro version 20.1.1.125. Isomeric SMILES were considered where applicable. SMILES codes that encoded aromatic substructures with lower-case letters in certain reports38,39 were unified according to the upper-case description scheme (structural curation)7.

Assays

Only functional assays were considered using either fluorescence labeling or radionuclide detection applying either living (selected or transfected) cells or membrane vesicles with reconstituted transporters. ATPase assays were not considered because ATPase activity and transporter inhibition may not be directly connected to each other. MDR reversal assay data was not considered because of the complexity of the involved processes and the fact that the triggered response(s) may not only be caused by ABC transporter inhibition. Table 1 provides an exhaustive list of functional tracers (and substrates) that were used to assess the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2. Table 2 summarizes all used host systems (cell lines and membrane vesicles) used for the evaluation of the 1,167 compounds against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2.

Table 1.

An exhaustive list of functional tracers that were used to functionally assess the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG27,27.

|

Table 2.

An exhaustive list of transporter host systems that were used to functionally assess the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS against the well-studied ABC transporters ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG27,27.

|

The assessment of the corresponding transporter by the respective host system is indicated by a black box. Regarding selected cells, the used cytotoxic agent is indicated under the respective transporter, and the cell subline abbreviation is given in brackets. The provided references are examples in which details in terms of the stated cell lines can be found7,38,42,48,52,84,89,93,95,97–114.

Bioactivity

The bioactivities (IC50 values) of the compounds were extracted from either (i) tables of the respective reports (including supplementary information); or (ii) screening figures with relative inhibition (Irel) values (%) compared to a standard (Imax; 100%). In the latter case, the IC50 values were estimated (either span or >, ≥, <, ~) in the previous multitarget dataset7,27.

Data Curation – Bioactivity Data

Dataset Update and Complementation

New reports particularly from 2021 and 2022 were taken into consideration to update the dataset with compounds that were evaluated against the three transporters ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2. In total, 22 new compounds were included into the list of qualified compounds7,40–42. In addition, we focused an extended literature search, particularly of known standard inhibitors of ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 to obtain bioactivities with less mathematical uncertainty which also align well with our empirical experience in the laboratory. These compounds included verapamil (ABCB143), cyclosporine A (ABCB141,43–46 and ABCC131,44–46), verlukast (ABCC131–36), and Ko143 (ABCG241,45). As a side note, the additional literature search also resulted in an update of bioactivity data of the natural compound piperine47. In the curation process to complement bioactivity values, we found that two compounds were erroneously included into the dataset (apatinib48 and ceritinib49). Both were not evaluated against ABCC1, and therefore, did not qualify for this dataset and were therefore removed.

Complementary Data Analysis

The bioactivity of several inhibitors could only be described as an estimation (either described as span, marked as ‘active’, or annotated with ‘>’, ‘≥’, ‘<’, ‘~’ in the previous dataset7,27). However, to allow for the use of the entire dataset in mathematical and computational operations, we sought to allocate defined bioactivity values to these compounds. Hence, the individual reports were analyzed and the given indications of bioactivity [e.g., screening figures, flow-cytometry histograms, or tables with bioactivity values other than IC50 values (e.g., percentages)] were taken into consideration for further data analysis. The specific bioactivity value (e.g., percentage inhibition) was extracted and correlated to the used compound concentration. By using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.0 applying the three-parameter logistic equation with a fixed Hill slope (=1.0), IC50 values were calculated and listed in the new multitarget dataset. A detailed curation protocol is provided on https://www.zenodo.org50 as well as he http://www.panabc.info website, and the related GraphPad Prism file containing the concentration-effect curves can be accessed without restrictions. In total, the bioactivity data of 104, 77, and 73 ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 inhibitors, respectively, have been calculated and complemented.

Data Determination

The bioactivities of five compounds [ayanin51, retusin51 (flavone derivative 1252), dihydrodibenzoazepine derivative 4i53, dregamine derivative 254, and tabernaemontanine derivative 2254] had to be determined without mathematical operations. The IC50 values of ayanin and retusin were stated as ‘>50 µM’ in the original report51. Usually, these kinds of statements (e.g., ‘>50 µM’, ‘>100’, ‘inactive’, etc) led to the allocation of such compounds into the ‘inactive’ category (arbitrary IC50 value of 2000 µM in the ABC_BPMDS). However, the authors of the respective publication stated that ayanin and retusin had some (weak) inhibitory activity51. Therefore, we decided to allocate an arbitrary value of 100 µM to these compounds to acknowledge their minor inhibitory potential against ABCC1. Dihydrodibenzoazepine derivative 4i53, dregamine derivative 254, and tabernaemontanine derivative 2254, on the other hand, reached over 100% inhibition at concentrations of 2.50 µM, 20.0 µM, and 20.0 µM, respectively. Unfortunately, these were the only indications of bioactivity by the authors of the original reports53,54. Hence, we decided to allocate arbitrary values of 0.999 µM53, 4.99 µM54, and 4.99 µM54, respectively, to acknowledge their potentially (very) high inhibitory power against ABCB1 as well as ABCG2 considering the effect-concentrations used in the original reports. These arbitrary IC50 values have been chosen since sub-classifications of bioactivity classes according to bioactivity thresholds (e.g., 1 and 5 µM) provided a better prediction in our previous works7.

Data Unification

Several compounds were evaluated in multiple assays, e.g., the mentioned standard inhibitors of ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2. However, to allocate one bioactivity value to one compound, a unification process was necessary. As IC50 values do not follow a normal distribution, the multiple IC50 values associated with one compound were subject to a three-step mathematical operation: (i) logarithmization of the IC50 values; (ii) calculation of the mean; and (iii) delogarithmization of the log(IC50)-mean value. The resultant mean value was allocated to the respective compound. It shall be noted that the bioactivities of the compounds curcumin I-III (ABCC1)55 and gefitinib (ABCB1 and ABCC1)56 were only given as a span in the original reports55,56, and hence, the mean of the respective span was taken for further operations. In total, 60, 48, and 209 ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 inhibitors have been given a new bioactivity value by these operations compared to the previous multitarget dataset7,27.

Data Correction and Harmonization

Through the complementary analysis process, several bioactivity values were corrected. This applied for compounds that were falsely marked as ‘inactive’ in the previous multitarget dataset (ABCB1: 22 compounds; ABCC1: 26 compounds; ABCG2: 19 compounds)7,27. Lastly, all bioactivity values of the ABC_BPMDS were harmonized according to a number of three significant digits. This harmonization resulted in a standardized format of presentation: (i) ‘XXX0 µM’; (ii) ‘XXX µM; (iii) XX.X µM; (iv) X.XX µM; (v) 0.XXX µM; and (vi) 0.0XX (X = any numeric value between 1–9). Here, 11, 8, and 9 ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 values have been changed compared to the previous multitarget dataset7,27.

Data Curation – Molecular-structural Data

The 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS were portrayed as canonical or isomeric SMILES codes as derived from the (i) respective report, (ii) PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), or (iii) SMILES generation tool of ChemDraw Pro version 20.1.1.125. All smiles were compared to each other to identify duplicates by using InstantJChem version 21.13.0. Through this individual cross-check of the molecular-structural data, 13 compounds were discovered as duplicates46,51,56–59 and their bioactivity values were merged with the original bioactivity data of the particular compound52,59–62. In addition, three compounds were identified to be incorrect in terms of their molecular structure and have been corrected in the dataset46,57,63.

Binary Pattern Generation

Background

In contrast to common molecular fingerprints for similarity-based virtual screenings20,64, the very recently reported novel drug discovery tool ‘computer-aided pattern analysis’ (‘C@PA’) identified that defined (=non-substituted) hydrogens and their positioning is particularly important in terms of the differentiation between selective and multitarget inhibition of ABC transporters7,26,27. Although certain fingerprints indeed consider polar hydrogens21,22, C@PA particularly discovered non-polar hydrogens with critical discriminatory potential in the virtual screening process7,26,27. However, the original C@PA worked with a very preliminary and limited dataset of 308 substructures which were compiled after multitarget dataset visualization and literature consideration65, of which only 162 substructures were active in the multitarget dataset of, at the time of the study, 1,049 compounds27.

Substructure Visualization, Identification, and Extension

For the development of a complete, detailed, and novel (multitarget) fingerprint, which may also universally be used in (multitarget) virtual screening approaches, the 1,167 compounds of the updated multitarget dataset were visualized using ChemDraw Pro version 20.1.1.125, and substructures were identified and extracted. The extracted substructures [e.g., single-standing/centered (hetero-)aromatic rings, condensed (hetero-)aromatic rings, (un)saturated side chains, extremities, and non-aromatic (hetero-)cycles, etc.] were derivatized by applying a heavy atom substitution scheme as already reported earlier26 (scaffold fragmentation and substructure hopping). Especially the presence and positioning of (non-polar) hydrogens in the sense of a proton/non-proton pattern scheme was stressed. These measures increased the quantity of substructural properties covered by the intended fingerprint. In addition, alternative datasets of ABC transporter modulators5 and modes of action (particularly ABC transporter activators)6,8 have been considered to gain complementary knowledge about potentially active substructures. The resultant substructures were subsequently searched in the 1,167 compounds (loaded as.csv file) using the query search function of InstantJChem version 21.13.0 and, if present, listed in the substructure catalog. As a result, a catalog of 604 active substructures has been assembled.

Individual Pattern Analysis7

In a final step, the multitarget dataset of 1,167 compounds was statistically analyzed for the listed 604 substructures of the substructure catalog. Here, the resultant list of hit molecules per substructure derived from the query search function of InstantJChem version 21.13.0 was saved and compared to the original list, translating the entry differences into a binary code [1 = substructure present (active substructure); 0 = substructure not present (inactive substructure)]. A binary pattern distribution scheme resulted which constituted the final ABC_BPMDS. It shall be taken note that the number of the very same substructure within the same compound was irrelevant; the presence (numeric value = 1) of the substructure was not an expression of how often the respective substructure appeared within the compound.

Data Records

The ABC_BPMDS is freely available in an .xlsx format under the http://www.zenodo.org28 URL as well as the http://www.panabc.info website and its use is free of charge. The dataset consists of (i) an individual database identifier for each compound; (ii) the original name of the compounds according to the original report(s); (iii) the IUPAC nomenclature of each compound generated by using ChemDraw Pro version 20.1.1.125; (iii) The SMILES code obtained either from the (a) supporting information of the respective report, (b) PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), or (c) manual drawing using ChemDraw Pro version 20.1.1.125; (iv) the physicochemical properties (a) CLogP, (b) calculated molecular water solubility (CLogS), (c) MW, (d) MR, (e) TPSA, (f) H-bond donors, (g) H-bond acceptors, (h) rotatable bonds, and (j) number of heavy atoms; (v) the associated bioactivity values expressed as (a) IC50 values [µM] against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 presented in the standardized format of three significant digits as outlined above [10log(mean)], and (b) pIC50 values against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2; (vi) the binary code (active = 1; inactive = 0) for each of the 604 evaluated substructures of the substructure catalog including their (a) trivial name, (b) SMILES code, (c) number of defined hydrogens, (d) number of heavy atoms, (e) total hit count, and (f) individual substructure identifier. The substructures are sorted from most abundant (left) to most rare (right); and (vii) the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) identifier (PMID) retrieved from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In addition, a detailed curation protocol as well as an associated GraphPad Prism file can be found on https://www.zenodo.org50 as well as the http://www.panabc.info website.

Technical Validation

Compounds

The 1,167 compounds were portrayed as canonical or isomeric SMILES codes as derived from the respective report or the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and imported into the MarvinSketch editor implemented in InstantJChem version 21.13.0. If the loaded SMILES code appeared as the intended original molecular representation according to the respective report or the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) without any errors, it was considered as valid.

Bioactivity Space Validation

In total, 113 reports between 1994 and 2022 have been collected, resulting in a final number of 1,167 compounds that were evaluated against ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2, including inactive compounds as well as selective, dual, and triple inhibitors. Amongst the 1,167 compounds are (i) 525 ABCB1 inhibitors, of which (a) 88 are selective ABCB1 inhibitors (no activity against ABCC1 and ABCG2; any given IC50 value), (b) 67 are potent ABCB1 inhibitors (IC50 values < 1 µM), and (c) 25 are selective and potent ABCB1 inhibitors; (ii) 344 ABCC1 inhibitors, of which (a) 61 are selective ABCC1 inhibitors (no activity against ABCB1 and ABCG2; any given IC50 value), (b) 45 are potent ABCC1 inhibitors (IC50 values < 1 µM), and (c) 11 are selective and potent ABCC1 inhibitors; (iii) 866 ABCG2 inhibitors, of which (a) 409 are selective ABCG2 inhibitors (no activity against ABCB1 and ABCC1; any given IC50 value), (b) 330 are potent ABCG2 inhibitors (IC50 values < 1 µM), and (c) 199 are selective and potent ABCG2 inhibitors.

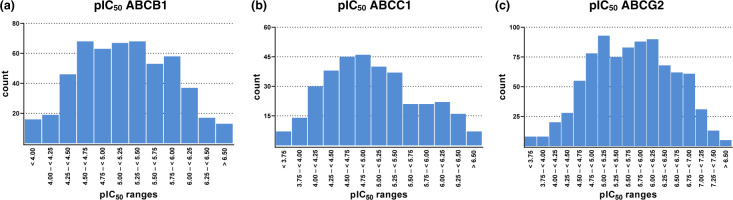

On the other hand, 38, 212, and 58 dual ABCB1/ABCC1, ABCB1/ABCG2, and ABCC1/ABCG2 inhibitors are present, respectively, of which 7, 99, and 13 can be considered as potent dual ABCB1/ABCC1, ABCB1/ABCG2, and ABCC1/ABCG2 inhibitors, respectively (IC50 < 10 µM). Finally, 187 triple ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 inhibitors can be defined, of which 54 can be considered as potent (IC50 < 10 µM; so-called ‘Class 7’ compounds7,26,27). Table 3 summarizes a survey of statistical parameters of the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of the pIC50 values of ABCB1 (A), ABCC1 (B), and ABCG2 (C) inhibitors amongst the entire ABC_BPMDS, which followed in all three cases a Gaussian normal distribution.

Table 3.

Statistical survey of the span as well as median and mean values of the bioactivity of the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes.

| inhibitor class | count | IC50 span [µM] | pIC50 span | IC50 median [µM] | pIC50 median | IC50 mean [µM] | pIC50 mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC_BPMDS | 1,167 | 0.0153–1630 | 7.815–2.788 | 4.39 | 5.358 | 3.84 | 5.416 |

| All ABCB1 | 525 | 0.0153–1460 | 7.815–2.836 | 6.37 | 5.196 | 6.32 | 5.199 |

| All ABCC1 | 344 | 0.146–1630 | 6.836–2.788 | 11.2 | 4.951 | 9.26 | 5.033 |

| All ABCG2 | 866 | 0.0234–405 | 7.631–3.393 | 1.95 | 5.710 | 2.00 | 5.698 |

| Selective ABCB1 | 88 | 0.0153–708 | 7.815–3.150 | 2.51 | 5.599 | 3.41 | 5.467 |

| Selective ABCC1 | 61 | 0.222–112 | 6.654–3.951 | 5.97 | 5.224 | 5.63 | 5.249 |

| Selective ABCG2 | 409 | 0.0234–405 | 7.631–3.393 | 1.06 | 5.975 | 1.13 | 5.948 |

| Dual ABCB1/ABCC1 | 38 | 0.289–180 | 6.539–3.745 | 20.4 | 4.692 | 15.2 | 4.819 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 212 | 0.0255–333 | 7.593–3.478 | 4.43 | 5.354 | 3.85 | 5.415 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 58 | 0.0988–163 | 7.005–3.788 | 10.1 | 4.996 | 6.92 | 5.160 |

| Triple ABCB1/ABCC1/ABCG2 | 187 | 0.0475–1630 | 7.323–2.788 | 6.98 | 5.156 | 6.74 | 5.172 |

The pIC50 values have been calculated by using the negative decadic logarithm of the respective bioactivity value.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of bioactivity values (pIC50) of the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS against ABCB1 (a), ABCC1 (b), and ABCG2 (c).

Physicochemistry Space Validation

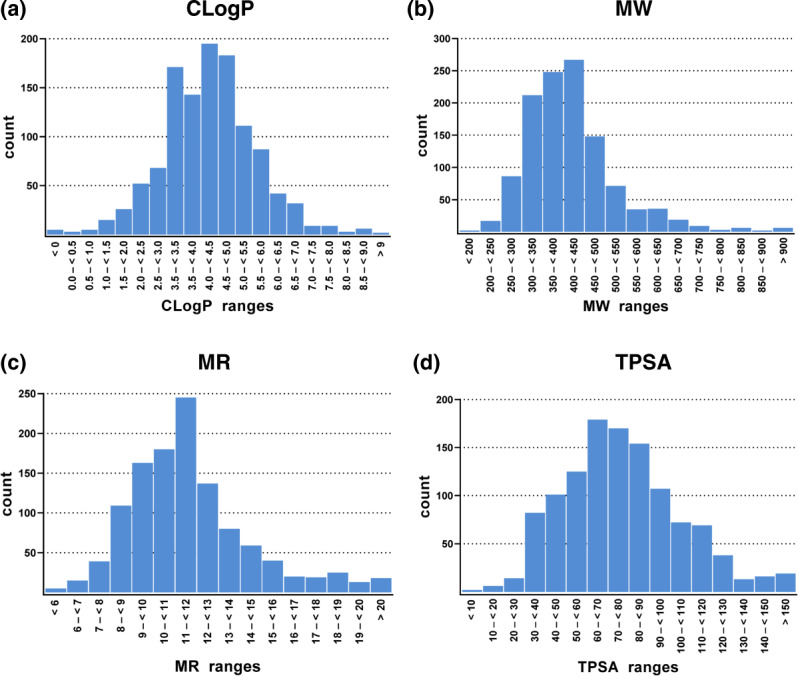

Physicochemical properties shape not only the pharmacological profile of ABC transporter inhibitors66–69, but are also very often used as additional discriminators in virtual screening processes7,26,27,38. To prove that the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS have a balanced distribution of physicochemical attributes, the ABC_BPMDS was analyzed for the CLogP, MW, MR, and TPSA using MOE version 2019.01. Figure 3 demonstrates that these physicochemical properties are normally distributed within the ABC_BPMDS comparable to other reported datasets23,70. Table 4 summarizes the median and mean values of CLogP, MW, MR, and TPSA of the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes. The median and mean values are well-aligned, which accounts for the equal distribution of values.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of the important physicochemical115 properties CLogP (a), MW (b), MR (c), and TPSA (d) amongst the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS as determined by MOE version 2019.01.

Table 4.

Statistical survey of median and mean values of the important physicochemical properties CLogP, MW, MR, and TPSA amongst the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes as determined by MOE version 2019.01.

| inhibitor class | count | CLogP median | CLogP mean | MW median | MW mean | MR median | MR mean | TPSA median | TPSA mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC_BPMDS | 1,167 | 4.33 | 4.26 | 403.39 | 418.38 | 11.27 | 11.73 | 73.86 | 77.87 |

| All ABCB1 | 525 | 4.40 | 4.78 | 432.43 | 458.67 | 12.07 | 12.90 | 73.63 | 79.56 |

| All ABCC1 | 344 | 3.91 | 3.88 | 420.44 | 442.92 | 11.72 | 12.37 | 76.10 | 84.82 |

| All ABCG2 | 866 | 4.34 | 4.25 | 396.37 | 415.32 | 11.13 | 11.64 | 74.73 | 79.01 |

| Selective ABCB1 | 88 | 5.22 | 5.47 | 452.11 | 481.94 | 13.08 | 13.70 | 61.42 | 65.98 |

| Selective ABCC1 | 61 | 3.37 | 3.41 | 374.49 | 377.22 | 11.07 | 10.70 | 69.77 | 75.29 |

| Selective ABCG2 | 409 | 4.38 | 4.35 | 372.38 | 381.58 | 10.39 | 10.67 | 73.86 | 75.14 |

| Dual ABCB1/ABCC1 | 38 | 5.03 | 4.80 | 475.56 | 471.03 | 13.19 | 13.20 | 70.05 | 78.29 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 212 | 4.42 | 4.52 | 420.23 | 434.62 | 11.86 | 12.32 | 75.69 | 75.83 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 58 | 3.62 | 3.68 | 376.91 | 398.33 | 10.52 | 11.23 | 76.26 | 80.98 |

| Triple ABCB1/ABCC1/ABCG2 | 187 | 3.95 | 3.91 | 432.44 | 472.47 | 11.91 | 13.10 | 79.44 | 90.45 |

Molecular-Structure Space Validation

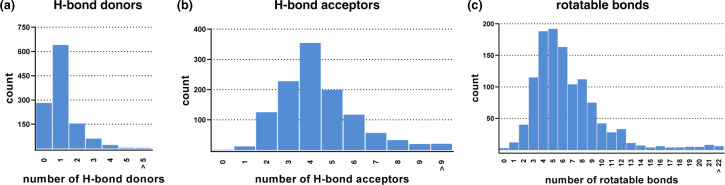

H-bonds and molecular flexibility are crucial aspects in terms of ligand-target interactions, especially for ABC transporters71. Hence, we analyzed the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS for their number of H-bond donors, H-bond acceptors, and rotatable bonds. Figure 4 visualizes the found distributions amongst the entire ABC_BPMDS. Together with CLogP and MW, H-bond donors and acceptors play a major role in the drug-likeliness as defined by Lipinsky72, particularly influencing drug absorption, distribution, and permeation. Considering the ‘Lipinski rule of five’ (CLogP ≤ 5; MW ≤ 500; H-bond donors ≤ 5; H-bond acceptors ≤10), a large majority of compounds of the ABC_BPMDS fulfils these requirements. In particular, (i) 73.8% of compounds have CLogP values of ≤5, (ii) 84.0% of compounds have a MW of ≤500, (iii) 99.7% of compounds have ≤5 H-bond donors, and (iv) 98.6% of compounds have ≤10 H-bond acceptors. Table 5 summarizes the median and mean values of H-bond donors, H-bond acceptors, and rotatable bonds of the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes. Hence, the ABC_BPMDS contains suitable templates for future drug design and therapeutic development purposes, however, leaves also enough molecular-structural and physicochemical space for explorational analyses beyond the ‘Lipinski rule of five’ for the creation of inhomogeneous high-quality compound collections and compound libraries.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of H-bond donors (a), H-bond acceptors (b), and rotatable bonds (c) amongst the 1,167 compounds of the ABC_BPMDS as determined by MOE version 2019.01.

Table 5.

Statistical survey of median and mean values of H-bond donors, H-bond acceptors, and rotatable bonds amongst the entire ABC_BPMDS as well as important sub-classes as determined by MOE version 2019.01.

| inhibitor class | count | H-bond donors median | H-bond donors mean | H-bond acceptors median | H-bond acceptors mean | rotatable bonds median | rotatable bonds mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC_BPMDS | 1,167 | 1 | 1.12 | 4 | 4.43 | 6 | 6.50 |

| All ABCB1 | 525 | 1 | 1.07 | 4 | 4.95 | 7 | 7.72 |

| All ABCC1 | 344 | 1 | 1.28 | 4 | 4.87 | 6 | 6.91 |

| All ABCG2 | 866 | 1 | 1.15 | 4 | 4.42 | 5 | 6.51 |

| Selective ABCB1 | 88 | 1 | 0.75 | 4 | 4.70 | 8 | 7.70 |

| Selective ABCC1 | 61 | 1 | 1.46 | 4 | 4.03 | 6 | 5.57 |

| Selective ABCG2 | 409 | 1 | 1.14 | 4 | 3.79 | 5 | 5.35 |

| Dual ABCB1/ABCC1 | 38 | 1 | 0.895 | 4 | 4.32 | 6 | 6.74 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 212 | 1 | 0.986 | 4 | 4.78 | 7 | 7.87 |

| Dual ABCC1/ABCG2 | 58 | 1 | 1.14 | 4 | 4.40 | 4.5 | 5.66 |

| Triple ABCB1/ABCC1/ABCG2 | 187 | 1 | 1.35 | 4 | 5.40 | 6 | 7.76 |

Usage Notes

Status Quo

Practical Use

An easy-to-use sort function allows the user to discriminate the compounds regarding their bioactivities toward the targets, physicochemical properties, or molecular-structural features, but also in terms of the 604 different substructures. Hence, the user can retrieve the necessary binary pattern information for subsequent virtual screening and rational drug design approaches.

Special Considerations

The majority of the compounds was evaluated in proper full-blown concentration effect curves within the original report, providing either only one single IC50 or two IC50 values from different assays for biological validation, resulting mostly in minor standard deviations or standard errors. However, considering established reference compounds, many IC50 values have been reported that are not fully covered by the deep literature search. Moreover, these drugs and drug-like compounds were tested in various assays, and thus, their IC50 values vary in a greater span than of other compounds. In addition, data processing prior to the original publication varied from laboratory to laboratory [e.g., number of concentrations tested, manner of assay performance (non-standardized procedures), manner of data analysis (e.g., three- vs four-parameter logistic equation, relative vs absolute inhibition), data presentation (single-point screening graphic vs full-blown concentration effect curve, number of significant digits, in- or exclusion of standard deviation and/or standard error)] – contributing to a greater uncertainty of these particular data. Furthermore, the assays themselves that were considered for the ABC_BPMDS were various [e.g., influx vs efflux assay, fluorescence labeling vs radionuclide detection, manner of substrate (e.g., calcein AM vs mitoxantrone), selected cells vs transfected cells vs membrane vesicles) – contributing to a general variation in data that is hidden due to the fact that most compounds were only evaluated in one particular assessment system. These aspects should be considered when using the ABC_BPMDS, however, at the same time, it should be taken note that our previous work demonstrated the strength of substructural patterns based on the previous version of the ABC_BPMDS7,26,27. A list of compounds affected by these variations in assessment systems can be found in the curation protocol under the https://www.zenodo.org50 URL (10.5281/zenodo.6405752) or on the http://www.panabc.info web site.

Future Perspective

Extension – New Compounds

The ABC_BPMDS provides the core application for extension to other, less- and under-studied ABC transporters. Particularly, the addressing of under-studied ABC transporters by multitarget agents poses a promising prospect for future drug discovery and development. Several compounds of the ABC_BPMDS have been demonstrated to address other ABC transporters as well5,25,26, such as benzbromarone5,7,25–27, cyclosporine A5,7,25–27, dipyridamole7,27,73–77, erlotinib7,27,78,79, imatinib5,7,25–27, nilotinib7,27,78,80,81, ritonavir7,27,82, verapamil5,7,25–27, and verlukast5,7,25–27,33. These ‘truly multitarget pan-ABC transporter inhibitors’25 are the primary focus for extension of the ABC_BPMDS, particularly with respect to their substructural elements that promote multitargeting. On the other hand, the addition of multitarget agents that are not part of the ABC_BPMDS will contribute valuable input to the polypharmacological space as charted by the future ABC_BPMDS_1.2.

Extension – New Substructures (‘ABC_BPMDS_1.2’)

The substructural elements of the mentioned truly multitarget pan-ABC transporter inhibitors include 4-anilinopyrimidine7,27, benzyl7, cyano7,27, 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl7, fluorine7,27, furan7,26, ethylene diamine7, ethylene hydroxy7, hydroxy7, isopropyl7,27, methylene hydroxy7, phenethyl7, piperazine7,27, pyrimidine7,26, quinazoline7,27, thiazlole7,26, and thioether7. These and other substructures will be re-evaluated with respect to true multitargeting, and thus, receive a differential value dependent on the purpose of the subsequent studies. Furthermore, the addition of multitarget agents that are not part of the ABC_BPMDS will contribute valuable input to the substructure catalog, extending the substructural output of the future ABC_BPMDS_1.2. Specifically, this information beyond known multitarget fingerprints will enable the exploration and exploitation of under-studied ABC transporters as potential drug targets of the future.

Extension – New Modes and Targets

Particularly, the inclusion of, for example, different modes of modulation (e.g., activation), bioactivity measurements [e.g., in vitro (ATPase assays or MDR reversal assays), in silico binding mode analyses (e.g., molecular docking or molecular dynamics simulations), or structural information (e.g., x-ray, cryo-EM, homology-modelling, or AlphaFold83)] will promote the discovery of drug candidates with distinctive mode of action. Furthermore, the logistics outlined in this work also provide a useful framework for similar data mining and descriptor approaches with respect to different pharmacological targets [e.g., under-studied human/bacterial ABC transporters, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels (ICs), solute carriers (SLCs; PANSLC, http://www.panslc.info) or tyrosine kinases (TKs)].

Acknowledgements

S.M.S. is supported by the Walter Benjamin and Research Grant Programmes of the German Research Foundation [DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Germany; #446812474, #504079349 (PANABC)]. P.J.J. appreciates the Cancer Institute of New South Wales Career Development Fellowship (#CDF171147) support. J.P. received funding from the DFG (Germany; #263024513), Nasjonalforeningen (Norway; #16154), HelseSØ (Norway, #2019054, #2019055, #2022046), Barnekreftforeningen (Norway; #19008), EEA and Norway grants Kappa programme [Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Czech Republic; #TO100078 (TAČR TARIMAD)], Norges forskningsråd [Norway; #295910 (NAPI), #327571 (PETABC)], and the European Commission (European Union; #643417). PETABC is an EU Joint Programme - Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project. PETABC is supported through the following funding organizations under the aegis of JPND – www.jpnd.eu: NFR #327571 – Norway; FFG #882717 – Austria; BMBF #01ED2106 – Germany; MSMT #8F21002 – Czech Republic; VIAA #ES RTD/2020/26 – Latvia; ANR #20-JPW2-0002-04 – France, SRC #2020-02905 – Sweden. The projects receive funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement #643417 (JPco-fuND). V.N is supported by the Research Grant Programme of the DFG [#504079349 (PANABC)]. The authors like to thank ChemAxon for providing academic research license for InstantJChem.

Author contributions

S.M.S. Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. P.J.J. Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding Acquisition. J.P. Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition. V.N. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Code availability

The ABC_BPMDS is available without any restrictions under the http://www.zenodo.org28 URL (10.5281/zenodo.6384343). In addition, a detailed curation protocol including a GraphPad Prism file are provided under the https://www.zenodo.org50 URL (10.5281/zenodo.6405752). All information is also available on the http://www.panabc.info website and the use is free of charge.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang JQ, et al. Multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs): Structure, function and the overcoming of cancer multidrug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2021;54:100743. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil-Martins E, Barbosa DJ, Silva V, Remiao F, Silva R. Dysfunction of ABC transporters at the blood-brain barrier: Role in neurological disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;213:107554. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasello M, Giudice AM, Scotlandi K. The ABC subfamily A transporters: Multifaceted players with incipient potentialities in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sodani K, Patel A, Kathawala RJ, Chen ZS. Multidrug resistance associated proteins in multidrug resistance. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31:58–72. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pahnke, J. et al. Strategies to gain novel Alzheimer's disease diagnostics and therapeutics using modulators of ABCA transporters. Free Neuropathol2, 10.17879/freeneuropathology-2021-3528 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Wiese M, Stefan SM. The A-B-C of small-molecule ABC transport protein modulators: From inhibition to activation-a case study of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (ABCC1) Med Res Rev. 2019;39:2031–2081. doi: 10.1002/med.21573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namasivayam, V. et al. Structural feature-driven pattern analysis for multitarget modulator landscapes. Bioinformatics, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab832 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Stefan SM, Wiese M. Small-molecule inhibitors of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 and related processes: A historic approach and recent advances. Med Res Rev. 2019;39:176–264. doi: 10.1002/med.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper AJ, Hegele RA, Burnett JR. Tangier disease: update for 2020. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2020;31:80–84. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremers FPM, Lee W, Collin RWJ, Allikmets R. Clinical spectrum, genetic complexity and therapeutic approaches for retinal disease caused by ABCA4 mutations. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;79:100861. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkhatib, A. M. & Omar, M. in StatPearls (2022).

- 12.Bisaccia, F., Koshal, P., Abruzzese, V., Castiglione Morelli, M. A. & Ostuni, A. Structural and Functional Characterization of the ABCC6 Transporter in Hepatic Cells: Role on PXE, Cancer Therapy and Drug Resistance. Int J Mol Sci22, 10.3390/ijms22062858 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Turk BR, Theda C, Fatemi A, Moser AB. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: Pathology, pathophysiology, diagnostic testing, newborn screening and therapies. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2020;80:52–72. doi: 10.1002/jdn.10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdallah, I. M., Al-Shami, K. M., Yang, E. & Kaddoumi, A. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Increases Amyloid-Related Pathology in TgSwDI Mice. Int J Mol Sci22, 10.3390/ijms22031231 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gomez-Zepeda, D., Taghi, M., Scherrmann, J. M., Decleves, X. & Menet, M. C. ABC Transporters at the Blood-Brain Interfaces, Their Study Models, and Drug Delivery Implications in Gliomas. Pharmaceutics12, 10.3390/pharmaceutics12010020 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hernandez-Lozano I, et al. PET imaging to assess the impact of P-glycoprotein on pulmonary drug delivery in rats. J Control Release. 2022;342:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckmueller H, Cascorbi I. ABCB1, ABCG2, ABCC1, ABCC2, and ABCC3 drug transporter polymorphisms and their impact on drug bioavailability: what is our current understanding? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2021;17:369–396. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2021.1876661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girardin F. Membrane transporter proteins: a challenge for CNS drug development. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:311–321. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.3/fgirardin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cascorbi I. Role of pharmacogenetics of ATP-binding cassette transporters in the pharmacokinetics of drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:457–473. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers D, Hahn M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:742–754. doi: 10.1021/ci100050t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender A, Mussa HY, Glen RC, Reiling S. Molecular similarity searching using atom environments, information-based feature selection, and a naive Bayesian classifier. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2004;44:170–178. doi: 10.1021/ci034207y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng F, Xi Y, Huang J, Ayers PW. A curated diverse molecular database of blood-brain barrier permeability with chemical descriptors. Sci Data. 2021;8:289. doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-01069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefan SM. Multi-target ABC transporter modulators: what next and where to go. Future Med Chem. 2019;11:2353–2358. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namasivayam V, Stefan K, Pahnke J, Stefan SM. Binding mode analysis of ABCA7 for the prediction of novel Alzheimer's disease therapeutics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:6490–6504. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Namasivayam V, Silbermann K, Pahnke J, Wiese M, Stefan SM. Scaffold fragmentation and substructure hopping reveal potential, robustness, and limits of computer-aided pattern analysis (C@PA) Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:3269–3283. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namasivayam V, Silbermann K, Wiese M, Pahnke J, Stefan SM. C@PA: Computer-Aided Pattern Analysis to Predict Multitarget ABC Transporter Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2021;64:3350–3366. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefan SM, Jansson PJ, Pahnke J, Namasivayam V. 2022. A curated binary pattern multitarget dataset of focused ABC transporter inhibitors. zenodo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Benson D, Boguski M, Lipman D, Ostell J. The National Center for Biotechnology Information. Genomics. 1990;6:389–391. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90583-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weidner LD, et al. The Inhibitor Ko143 Is Not Specific for ABCG2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:384–393. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.225482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson BG, Tan KW, Osa-Andrews B, Iram SH. High-content screening of clinically tested anticancer drugs identifies novel inhibitors of human MRP1 (ABCC1) Pharmacol Res. 2017;119:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csandl MA, Conseil G, Cole SP. Cysteinyl Leukotriene Receptor 1/2 Antagonists Nonselectively Modulate Organic Anion Transport by Multidrug Resistance Proteins (MRP1-4) Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44:857–866. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.069468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsson P, Pedersen JM, Norinder U, Bergstrom CA, Artursson P. Identification of novel specific and general inhibitors of the three major human ATP-binding cassette transporters P-gp, BCRP and MRP2 among registered drugs. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1816–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu CP, Klokouzas A, Hladky SB, Ambudkar SV, Barrand MA. Interactions of mefloquine with ABC proteins, MRP1 (ABCC1) and MRP4 (ABCC4) that are present in human red cell membranes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mrowczynska L, Bobrowska-Hagerstrand M, Wrobel A, Soderstrom T, Hagerstrand H. Inhibition of MRP1-mediated efflux in human erythrocytes by mono-anionic bile salts. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3173–3178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leier I, Jedlitschky G, Buchholz U, Keppler D. Characterization of the ATP-dependent leukotriene C4 export carrier in mastocytoma cells. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang S, Tan DS. Advancing chemistry and biology through diversity-oriented synthesis of natural product-like libraries. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silbermann K, Stefan SM, Elshawadfy R, Namasivayam V, Wiese M. Identification of Thienopyrimidine Scaffold as an Inhibitor of the ABC Transport Protein ABCC1 (MRP1) and Related Transporters Using a Combined Virtual Screening Approach. J Med Chem. 2019;62:4383–4400. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riganti C, et al. Design, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Modeling of Tetrahydroisoquinoline Derivatives: Discovery of A Potent P-Glycoprotein Ligand Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Stem Cells. J Med Chem. 2019;62:974–986. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagiannis D, et al. Alisertib shows negligible potential for perpetrating pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions on ABCB1, ABCG2 and cytochromes P450, but acts as dual-activity resistance modulator through the inhibition of ABCC1 transporter. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2022;434:115823. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dakhlaoui I, et al. Synthesis and biological assessment of new pyrimidopyrimidines as inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) Bioorg Chem. 2021;116:105326. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.To KKW, et al. Reversal of multidrug resistance by Marsdenia tenacissima and its main active ingredients polyoxypregnanes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;203:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muller H, et al. New functional assay of P-glycoprotein activity using Hoechst 33342. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:7470–7479. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silbermann K, Li J, Namasivayam V, Stefan SM, Wiese M. Rational drug design of 6-substituted 4-anilino-2-phenylpyrimidines for exploration of novel ABCG2 binding site. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;212:113045. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silbermann K, et al. Superior Pyrimidine Derivatives as Selective ABCG2 Inhibitors and Broad-Spectrum ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 Antagonists. J Med Chem. 2020;63:10412–10432. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krapf MK, Wiese M. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 4-Anilino-quinazolines and -quinolines as Inhibitors of Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2) J Med Chem. 2016;59:5449–5461. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bi X, et al. Piperine enhances the bioavailability of silybin via inhibition of efflux transporters BCRP and MRP2. Phytomedicine. 2019;54:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mi YJ, et al. Apatinib (YN968D1) reverses multidrug resistance by inhibiting the efflux function of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7981–7991. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu J, et al. Effect of ceritinib (LDK378) on enhancement of chemotherapeutic agents in ABCB1 and ABCG2 overexpressing cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2015;6:44643–44659. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stefan SM, Jansson PJ, Pahnke J, Namasivayam V. 2022. Supplementary Information - A curated binary pattern multitarget dataset of focused ABC transporter inhibitors. zenodo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Pick A, et al. Structure-activity relationships of flavonoids as inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:2090–2102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Juvale K, Stefan K, Wiese M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of flavones and benzoflavones as inhibitors of BCRP/ABCG2. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;67:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gu X, et al. Discovery of alkoxyl biphenyl derivatives bearing dibenzo[c,e]azepine scaffold as potential dual inhibitors of P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:3419–3421. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paterna A, et al. Monoterpene indole alkaloid azine derivatives as MDR reversal agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chearwae W, et al. Curcuminoids purified from turmeric powder modulate the function of human multidrug resistance protein 1 (ABCC1) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:376–388. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ozvegy-Laczka C, et al. High-affinity interaction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors with the ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1485–1495. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antoni F, et al. Tariquidar-related triazoles as potent, selective and stable inhibitors of ABCG2 (BCRP) Eur J Med Chem. 2020;191:112133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krapf MK, Gallus J, Wiese M. Synthesis and biological investigation of 2,4-substituted quinazolines as highly potent inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) Eur J Med Chem. 2017;139:587–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pick A, Wiese M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors influence ABCG2 expression in EGFR-positive MDCK BCRP cells via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:650–662. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obreque-Balboa JE, Sun Q, Bernhardt G, Konig B, Buschauer A. Flavonoid derivatives as selective ABCC1 modulators: Synthesis and functional characterization. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;109:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Juvale K, Gallus J, Wiese M. Investigation of quinazolines as inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:7858–7873. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Juvale K, Wiese M. 4-Substituted-2-phenylquinazolines as inhibitors of BCRP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6766–6769. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schafer A, Kohler SC, Lohe M, Wiese M, Hiersemann M. Synthesis of Homoverrucosanoid-Derived Esters and Evaluation as MDR Modulators. J Org Chem. 2017;82:10504–10522. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Durant JL, Leland BA, Henry DR, Nourse JG. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2002;42:1273–1280. doi: 10.1021/ci010132r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jordan AM, Roughley SD. Drug discovery chemistry: a primer for the non-specialist. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schmitt SM, Stefan K, Wiese M. Pyrrolopyrimidine Derivatives as Novel Inhibitors of Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1) J Med Chem. 2016;59:3018–3033. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marighetti F, Steggemann K, Karbaum M, Wiese M. Scaffold identification of a new class of potent and selective BCRP inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:742–751. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marighetti F, Steggemann K, Hanl M, Wiese M. Synthesis and quantitative structure-activity relationships of selective BCRP inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:125–135. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stefan, S. M. Purines and 9-deazapurines as Modulators of Multidrug Resistance-associated Protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1)-mediated Transport 14.11.2017 edn, 1 (2017).

- 70.Stepanov D, Canipa S, Wolber G. HuskinDB, a database for skin permeation of xenobiotics. Sci Data. 2020;7:426. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00764-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pajeva IK, Wiese M. Pharmacophore model of drugs involved in P-glycoprotein multidrug resistance: explanation of structural variety (hypothesis) J Med Chem. 2002;45:5671–5686. doi: 10.1021/jm020941h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bieczynski F, Burkhardt-Medicke K, Luquet CM, Scholz S, Luckenbach T. Chemical effects on dye efflux activity in live zebrafish embryos and on zebrafish Abcb4 ATPase activity. FEBS Lett. 2021;595:828–843. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schadt S, et al. Minimizing DILI risk in drug discovery - A screening tool for drug candidates. Toxicol In Vitro. 2015;30:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sager G, et al. Novel cGMP efflux inhibitors identified by virtual ligand screening (VLS) and confirmed by experimental studies. J Med Chem. 2012;55:3049–3057. doi: 10.1021/jm2014666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu CP, Calcagno AM, Hladky SB, Ambudkar SV, Barrand MA. Modulatory effects of plant phenols on human multidrug-resistance proteins 1, 4 and 5 (ABCC1, 4 and 5) FEBS J. 2005;272:4725–4740. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smeets PH, van Aubel RA, Wouterse AC, van den Heuvel JJ, Russel FG. Contribution of multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2/ABCC2) to the renal excretion of p-aminohippurate (PAH) and identification of MRP4 (ABCC4) as a novel PAH transporter. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2828–2835. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000143473.64430.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beretta GL, Cassinelli G, Pennati M, Zuco V, Gatti L. Overcoming ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance: The dual role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors as multitargeting agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;142:271–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheung L, et al. Identification of new MRP4 inhibitors from a library of FDA approved drugs using a high-throughput bioluminescence screen. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eadie LN, Dang P, Goyne JM, Hughes TP, White DL. ABCC6 plays a significant role in the transport of nilotinib and dasatinib, and contributes to TKI resistance in vitro, in both cell lines and primary patient mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hupfeld T, et al. Tyrosinekinase inhibition facilitates cooperation of transcription factor SALL4 and ABC transporter A3 towards intrinsic CML cell drug resistance. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:204–213. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ambrus C, Bakos E, Sarkadi B, Ozvegy-Laczka C, Telbisz A. Interactions of anti-COVID-19 drug candidates with hepatic transporters may cause liver toxicity and affect pharmacokinetics. Sci Rep. 2021;11:17810. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chearwae W, Anuchapreeda S, Nandigama K, Ambudkar SV, Limtrakul P. Biochemical mechanism of modulation of human P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) by curcumin I, II, and III purified from Turmeric powder. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:2043–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dohse M, et al. Comparison of ATP-binding cassette transporter interactions with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:1371–1380. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.031302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colabufo NA, et al. Multi-drug-resistance-reverting agents: 2-aryloxazole and 2-arylthiazole derivatives as potent BCRP or MRP1 inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:188–195. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jekerle V, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of WK-X-34, a novel inhibitor of P-glycoprotein and BCRP, using radio imaging techniques. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:414–422. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mathias TJ, et al. The FLT3 and PDGFR inhibitor crenolanib is a substrate of the multidrug resistance protein ABCB1 but does not inhibit transport function at pharmacologically relevant concentrations. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:300–309. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Telbisz, A. et al. Interactions of Potential Anti-COVID-19 Compounds with Multispecific ABC and OATP Drug Transporters. Pharmaceutics13, 10.3390/pharmaceutics13010081 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Zhang Y, Laterra J, Pomper MG. Hedgehog pathway inhibitor HhAntag691 is a potent inhibitor of ABCG2/BCRP and ABCB1/Pgp. Neoplasia. 2009;11:96–101. doi: 10.1593/neo.81264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vagiannis D, Yu Z, Novotna E, Morell A, Hofman J. Entrectinib reverses cytostatic resistance through the inhibition of ABCB1 efflux transporter, but not the CYP3A4 drug-metabolizing enzyme. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;178:114061. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tan KW, Sampson A, Osa-Andrews B, Iram SH. Calcitriol and Calcipotriol Modulate Transport Activity of ABC Transporters and Exhibit Selective Cytotoxicity in MRP1-overexpressing Cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46:1856–1866. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.081612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lempers VJ, et al. Inhibitory Potential of Antifungal Drugs on ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters P-Glycoprotein, MRP1 to MRP5, BCRP, and BSEP. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:3372–3379. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02931-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Holland ML, Allen JD, Arnold JC. Interaction of plant cannabinoids with the multidrug transporter ABCC1 (MRP1) Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;591:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teodori E, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of stereo- and regioisomers of amino aryl esters as multidrug resistance (MDR) reversers. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;182:111655. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scoparo CT, et al. Dual properties of hispidulin: antiproliferative effects on HepG2 cancer cells and selective inhibition of ABCG2 transport activity. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;409:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pawarode A, et al. Differential effects of the immunosuppressive agents cyclosporin A, tacrolimus and sirolimus on drug transport by multidrug resistance proteins. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang XC, Sun YL, Salim AA, Chen ZS, Capon RJ. Parguerenes: Marine red alga bromoditerpenes as inhibitors of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) in multidrug resistant human cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kita DH, et al. Mechanistic basis of breast cancer resistance protein inhibition by new indeno[1,2-b]indoles. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1788. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79892-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Munoz-Martinez F, et al. Celastraceae sesquiterpenes as a new class of modulators that bind specifically to human P-glycoprotein and reverse cellular multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7130–7138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sun S, et al. The two enantiomers of tetrahydropalmatine are inhibitors of P-gp, but not inhibitors of MRP1 or BCRP. Xenobiotica. 2012;42:1197–1205. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2012.702247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sen R, et al. The novel BCR-ABL and FLT3 inhibitor ponatinib is a potent inhibitor of the MDR-associated ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2033–2044. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li S, et al. Piperine, a piperidine alkaloid from Piper nigrum re-sensitizes P-gp, MRP1 and BCRP dependent multidrug resistant cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2011;19:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhu HJ, et al. Characterization of P-glycoprotein inhibition by major cannabinoids from marijuana. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:850–857. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ivnitski-Steele I, et al. High-throughput flow cytometry to detect selective inhibitors of ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 transporters. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6:263–276. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Teng YN, et al. beta-carotene reverses multidrug resistant cancer cells by selectively modulating human P-glycoprotein function. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kannan P, et al. The "specific" P-glycoprotein inhibitor Tariquidar is also a substrate and an inhibitor for breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:82–89. doi: 10.1021/cn100078a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sachs J, et al. Novel 3,4-Dihydroisocoumarins Inhibit Human P-gp and BCRP in Multidrug Resistant Tumors and Demonstrate Substrate Inhibition of Yeast Pdr5. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:400. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gu X, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel bifendate derivatives bearing 6,7-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e]azepine scaffold as potent P-glycoprotein inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;51:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ma SL, et al. Lapatinib antagonizes multidrug resistance-associated protein 1-mediated multidrug resistance by inhibiting its transport function. Mol Med. 2014;20:390–399. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wu CP, et al. Overexpression of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) mutant cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rijpma SR, et al. Atovaquone and quinine anti-malarials inhibit ATP binding cassette transporter activity. Malar J. 2014;13:359. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Holland ML, Lau DT, Allen JD, Arnold JC. The multidrug transporter ABCG2 (BCRP) is inhibited by plant-derived cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:815–824. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krauze A, et al. Thieno[2,3-b]pyridines–a new class of multidrug resistance (MDR) modulators. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:5860–5870. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Namasivayam, V. et al. Physicochemistry shapes bioactivity landscape of pan-ABC transporter modulators: anchor point for innovative Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Int J Biol Macromol10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.07.062 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Stefan SM, Jansson PJ, Pahnke J, Namasivayam V. 2022. A curated binary pattern multitarget dataset of focused ABC transporter inhibitors. zenodo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stefan SM, Jansson PJ, Pahnke J, Namasivayam V. 2022. Supplementary Information - A curated binary pattern multitarget dataset of focused ABC transporter inhibitors. zenodo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The ABC_BPMDS is available without any restrictions under the http://www.zenodo.org28 URL (10.5281/zenodo.6384343). In addition, a detailed curation protocol including a GraphPad Prism file are provided under the https://www.zenodo.org50 URL (10.5281/zenodo.6405752). All information is also available on the http://www.panabc.info website and the use is free of charge.