Abstract

In recent years, the functional properties of peptides derived from food proteins have attracted considerable interest. Among them, bioactive peptides that can effectively bind metals have application prospects in the improvement of mineral bioavailability, and compensating for the shortcomings of the generally low bioavailability of inorganic mineral supplements. Although a reasonable understanding of structure activity relationship related to the calcium binding of peptides has been gained, physiological connections of peptides as mineral carriers to gastrointestinal uptake needs further research. Hence, this article reviews (1) the development of calcium supplements; (2) inorganic calcium sources and bone calcium; (3) source and acquisition of biologically active peptides; (4) calcium peptide chelation mechanism and structure–activity relationship; and (5) Methods for evaluating calcium bioavailability.

Keywords: Calcium supplement, Bioavailability, Calcium chelating peptide, Calcium binding capacity, Structure–activity

Introduction

Normal biological processes in the human body involves 22 inorganic elements, which can be replenished through daily diet. Calcium is one of the most abundant inorganic elements in human body (1.5–2.2% of total body weight) (Zhang et al., 2021a). Calcium participates in many important biological functions of the body, such as muscle contraction, nerve conduction, glandular secretion, and bone structural support (Liao et al., 2020; Vannucci et al., 2018). Adequate calcium intake can reduce the risk of chronic diseases, winning the title of ‘super nutrient’ for its role in reducing the risk of osteoporosis, high blood pressure, colon cancer, and other diseases (Chang et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2001). When the body's calcium intake is insufficient, calcium is released from the bones, and thus the risk of osteoporosis and other diseases increases.

The main source of calcium intake is daily food, and calcium content in green vegetables is usually lower than that of milk and dairy or meat products. The intake of calcium supplements and calcium-fortified food alleviates calcium deficiency. The intestinal tract serves an entry site of calcium ions to the body. Calcium is absorbed in the human gastrointestinal tract in two main ways: metabolism-driven intercellular transport and passive unsaturated pathway (paracellular pathway) (Diaz de Barboza et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2021). The absorption of dietary calcium is affected by many factors. Calcium precipitation easily occurs in a neutral intestinal environment; for instance, oxalic acid in spinach readily binds to calcium to produce insoluble calcium salt, and other cations, such as zinc and iron, can reduce the bioavailability of calcium (Liao et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2001). Therefore, calcium deficiency may still occur even when calcium intake is extremely high.

Development of calcium supplements

The development of calcium supplements has undergone four stages: inorganic calcium salt, organic acid calcium salt, amino acid chelate calcium, and peptide chelate calcium.

The first generation of inorganic calcium salt is mainly composed of calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate, and calcium chloride. Calcium exists in the form of ions, which is easy to form precipitation in the process of gastrointestinal digestion, and has obvious defects in calcium absorption and bioavailability, and long-term use may produce side effects and increase the burden on the human body (Felix and Danielle 1999; Zhang et al., 2021a).

The second generation of organic calcium mainly includes calcium lactate, calcium citrate, and calcium gluconate and is more soluble than the first generation of inorganic calcium salt but has the disadvantages of easily forming precipitates and having low efficiency in calcium supplements (Younes et al., 2018).

The third generation of amino acid chelated calcium overcomes the main limitation of the low bioavailability of ionic calcium but easily precipitates in the gastrointestinal environment, has low bioavailability when ionic calcium concentration is low, and is toxic when ionic calcium concentration is high. The absorption of calcium ions in the first two generations of calcium supplements depends on the calcium binding protein, but calcium amino acid chelate breaks this restriction. The amino acids surround calcium ions, are totally absorbed and do not dissociate immediately after entering the blood. Thus, they are considered good substitutes for ionic calcium supplements. However, the chelating reactions of amino acids and calcium are extremely costly to achieve and may produce unwanted color reactions and lipid oxidation reactions (Guo et al., 2014; Pawlos et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022).

The fourth generation of peptide chelate calcium has become a major research topic. Peptides binding to calcium as a ligand has many benefits, such as low energy consumption, fast transportation, and minimal carrier saturation, and can form soluble stable chelates with calcium ions. Peptide calcium chelates have attracted substantial interest due to their good adsorption properties and high bioavailability (Cai et al., 2017a). To date, researchers have isolated peptides with calcium chelation activities from many different food sources, such as Pacific cod skin protein (Wu et al., 2017), Antarctic krill protein (Hou et al., 2018), tilapia protein (He et al., 2022), soybean protein (Lv et al., 2013), and egg white protein (Bao et al., 2021b). Peptide calcium chelates are ideal calcium supplements because they have good stability and are easily absorbed in the stomach and intestines (Kai et al., 2018). Specially, casein phosphor peptides (CPPs) are phosphorylated peptide with good calcium supplement effect when combined with calcium chelates and have thus been commercially produced (Perego et al., 2015).

These calcium supplements may provide people suffering from lactose intolerance with nutritional food containing high amounts of bioavailable calcium.

Inorganic calcium and bone calcium

Calcium chloride, calcium hydroxide, and other inorganic calcium salts as calcium sources are usually reacted with bioactive peptides to form calcium peptide chelates. Bao et al. (2008) used calcium chloride as a calcium source and reacted it with soybean protein hydrolysate to produce a complex. The molecular weight of a peptide and the content of carboxyl group are two important factors affecting chelation reactions. Lv et al. (2013) combined soy protein hydrolysate with calcium chloride and believed that the complexes may have a positive effect on bone accretion of fast-growing animals through rat experiments.

Bone calcium binds to bioactive peptides, similar to calcium chloride. Larsen et al. (2000) showed that calcium extracted from the bones of small fish is effective and the bones are potential sources of calcium. Jung et al. (2006) extracted peptides and soluble calcium from the bones of Alaskan cod discarded during industrial processing and demonstrated the beneficial effects of the compounds as calcium fortifiers. Moreover, they used pepsin to release soluble Ca and isolate the peptide TBP (VLSGGTTMAMYTLV), which has a low molecular weight. TBP significantly inhibits the formation of insoluble phosphates and has the same binding characteristics as CPPs and calcium. In addition, TBD concentration determines calcium solubility.

However, binding reactions of animal bones or inorganic calcium salts as calcium sources with calcium-ion-chelating peptides have not been explored extensively.

Calcium-chelating peptide

Sources of calcium-chelating peptides

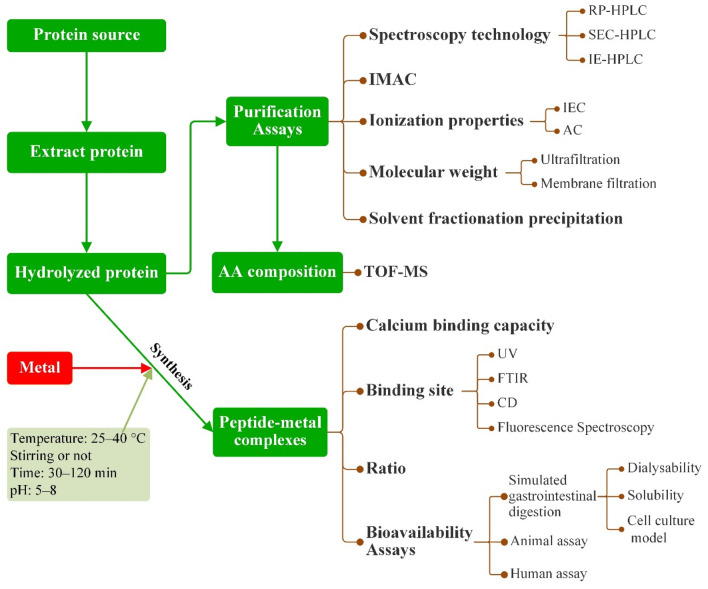

Bioactive peptides are encrypted within the primary structures of proteins but can be released by proteolysis (Auestad and Layman 2021). Sources of calcium-chelating peptides is abundant, including plant, animal and microbial proteins. Plant seeds and fruit are rich in proteins, such as the calcium-chelating peptides isolated from lemon basil seeds by Kheeree et al. (2022). Complexes containing calcium play positive roles in promoting effect on calcium transport and absorption. Essential amino acids in animal proteins are relatively complete. Liu et al. (2020) isolated calcium-binding peptides in tilapia and believed that calcium-binding peptides chelated with calcium ions can be used as a good raw material for calcium supplements. In addition, some peptides isolated from microorganisms have been found to have good calcium binding properties (Cai et al., 2017b). Figure 1 shows the process of obtaining, purifying, synthesizing and analyzing metal-binding peptides and their complexes.

Fig. 1.

Process of obtaining, purifying, synthesizing, and analyzing metal-binding peptides and their complexes

Direct method

The preparation methods of bioactive peptides include biological enzymatic hydrolysis, acidolysis, alkali decomposition and fermentation (Kaur et al., 2019). Enzymatic hydrolysis is widely used in preparing calcium-chelated peptides because of its high safety, short cycle, and high controllability. Proteases have different hydrolysis sites, and the hydrolysis products of the same protein samples vary, and thus the proper selection of proteases and hydrolysis conditions is a prerequisite for the preparation of protein peptides with high chelating activities (Kaur et al., 2019). In the present study, pepsin, alkaline protease, trypsin, central protease, and flavor protease were used.

Calcium peptides chelated through the enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins from different sources are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of animal protein to prepare calcium peptide chelate

| Protein source | Types of proteases | Peptide: CaCl2 ratio | Reaction conditions | Identified peptide sequence | Binding site (group) | Bioavailability assay | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea cucumber | Trypsin, pepsin | 1:1 molar ratio | Stirring (50 °C, pH 8.0, 1 h); adding ethanol; centrifugation (12000 g, 5 min) | NEDDLNK | Carboxyl oxygen and amino nitrogen atoms of two Glu and one Asp | Digestion model in vitro | (Cui et al., 2018) |

| Pig bone | Alcalase, neutrase | 4:1 mass ratio | pH 9, 50 °C for 40 min, then centrifugation (10,733 g, 10 min, 4 °C) | / | Carboxyl oxygen and amino nitrogen atoms | Caco-2 cell monolayers | (Wu et al., 2019) |

| Egg white | Neutrase | 4:1 mass ratio | pH 8.2, 53 °C for 30 min | / | Asp, Glu, Lys, Thr, Gly, Cys | Caco-2 cell monolayers | (Huang et al., 2021) |

| Tilapia | Complex pro-tease | 1:1.11 mass ratio | Incubation (37 °C, pH 7.8, 30 min); add sodium phosphate buffer; incubation (30 min); centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10 min) | YGTGL; LVFL | Carboxyl oxygen and amino nitrogen atoms | / | (Liu et al., 2020) |

| Pacific cod bone | Trypsin, neutral protease | 30 g hydrolysate: 11 g CaCl2 | Stirring (50 °C, pH 7.0) for 1 h; adding ethanol; centrifugation (7000 g, 15 min); collect precipitation | / | Carboxyl and amino groups | Wistar rat model | (Kai et al., 2018) |

Table 2.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of plant and microbial protein to prepare calcium peptide chelate

| Protein source | Types of proteases | Peptide: CaCl2 ratio | Chelating reaction conditions | Identified peptide sequence | Binding site (group) | Bioavailability assay | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemon basil seeds | Alcalase | 0.5 mg/mL protein hydrolysates to 1 mL of 9 mM CaCl2 | Stirring (pH 7.5, 37 °C,150 rpm, 2 h); centrifugation (15,900 g, 10 min) | AFNRAKSKALEN; YDSSGGPTPWLSPY | Amino nitrogen atoms and the oxygen atoms on the carboxyl group | Caco-2 cell monolayers | (Kheeree et al., 2022) |

| Schizochytrium sp. | Alcalase, favourzyme | / | / | YL | Carboxyl oxygen atoms, amino nitrogen atoms, the nitrogen and oxygen atoms of amide bonds | Caco-2 cell monolayers | (Cai et al., 2017b) |

| Sunflower seed; peanut | Pepsin, trypsin | 1:3.33 mass ratio | Incubation (30 min); add ethanol; centrifugation (2268 g, 20 min) | Peptide contains a large number of characteristic amino acid sequences | Carboxyl and amino groups | Caco-2 cell monolayers | (Bao et al., 2021a) |

| Manchurian walnut | Alcalase | 3:1 mass ratio | pH 8, 40 min, 45 °C | / | Amino nitrogen atoms, carboxyl groups and the C=O of the peptide bond which has a negative dipole | Simulate gastrointestinal digestion in vitro | (Fang et al., 2020) |

Chemical modification

The chemical modification of a polypeptide is a method for modifying and changing the structures or side chain groups of the main peptide chains and altering the biochemical properties of peptides.

Common peptide modification methods can be divided into the following four categories according to the modification site of the peptide: N-terminal modification (acylation modification), carbon-terminal modification (amidation modification), intermediate residue modification (glycosylation modification, phosphorylation modification, etc.), and deamidation, cyclization modification (Luo et al., 2022).

Chelating mechanism and structure–activity relationship of peptide calcium

In general, peptide–calcium complex reactions are performed by mixing polypeptide solutions with CaCl2 at a specific temperature and time (Liao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021c). The reactions are accelerated by stirring the solutions. Under most conditions, pH can be controlled by adding a buffer to a reaction medium because deprotonation groups facilitate the binding of metals (Caetano-Silva et al., 2020).

Binding principle of peptide-metal chelates

The prerequisite for the connection between peptide and calcium is the presence of one or more electron donors on the surfaces of peptides. These electron donors coordinate with calcium ions. Structurally, calcium ions are components of chelates (Hu et al., 2004; Tian et al., 2021; Ueda et al., 2003). Peptides contribute electron pairs to calcium ions and are therefore considered Lewis bases, whereas the calcium ions are considered Lewis acids. Peptide–metal ion reactions occur because of the interactions between Lewis acids and Lewis bases (Caetano-Silva et al., 2020).

Molecules with affinity for biominerals must have basic structures that facilitate their binding to minerals. Three conditions should be met in the generation of complexes: (1) ligand containing functional groups that can form covalent bonds; (2) the existence of such complexes should be spatial; (3) the formation of the complex must be possible in energy. Amino acids sequences play a vital role in the ability of polypeptides to bind to metals. In addition, polypeptide structure, steric effect, and molecular weight are important factors affecting the mineral binding ability of peptides (Caetano-Silva et al., 2021).

Binding sites of peptide-metal chelates

Current research on peptide calcium binding mechanism has explored phosphate group-calcium (CPPs, PPPs), carboxy-calcium amino acid-calcium complexes and histidine, cysteine, and amide. Except a small number of amino acid side chains, calcium ions are chelated mainly by the α-amino and carboxyl groups of amino acids (Chen et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2017).In the characterization of calcium peptide chelation mechanisms, the essence of calcium peptide binding is that calcium ions react with specific chemical groups in polypeptides. This article divides these reactions into three types: (1) phosphoric group-calcium; (2) carboxy-calcium and amino-calcium; (3) other modes (Zhang et al., 2021c).

Phosphoric group-calcium

The most representative phosphate-group-calcium-binding modes are CPPs and phosvitin phosphopeptides (PPPs) (Sun et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021).

CPPs are phosphorylated peptides derived from casein and can be released by the enzymatic hydrolysis of αs1, αs2, and β-CN in vivo or in vitro and bind to calcium irons in unidentate, bidentate, or tridentate geometries (Dong et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2020). Additionally, CPPs are phosphorylated and can be formed with calcium and exert good calcium supplementation effects. Most CPPs contain a cluster SpSpSpEE composed of up to three phosphoserine groups and two glutamate residues. It is a highly polar acidic sequence that binds to minerals, such as Ca, and plays an important role in mineral bioavailability (Esther et al., 2005; Miquel et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2018).

PPPs are obtained through the trypsin hydrolysis of phosvitin, and the content of phosphate groups is a key factor affecting the calcium binding capacity of phosvitin. Moreover, PPPs with 35% phosphate content effectively enhance calcium binding and inhibition ability and thus promote the formation of insoluble calcium phosphate (Sun et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2021).

Carboxyl-calcium and amino-calcium

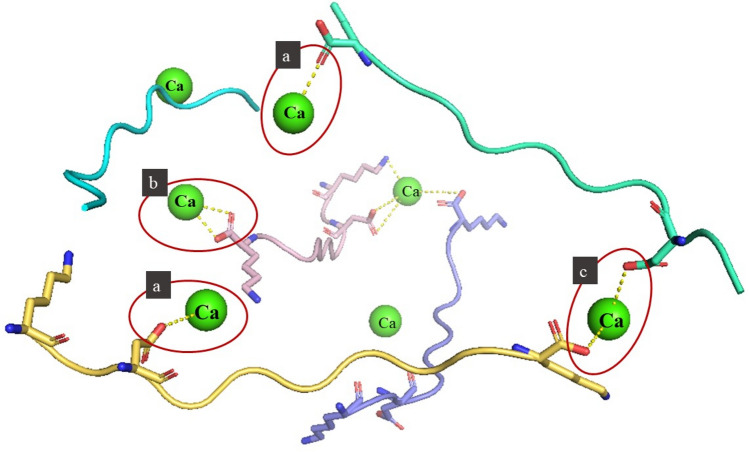

Carboxyl groups and amino groups also play an important role in peptide calcium binding reactions. Zhang et al. (2019) isolated a novel calcium-binding peptide (KGDPGLSPGK) from Pacific cod bone gel hydrolysate. The binding sites of the peptide and calcium were characterized through circular dichroism, infrared spectroscopy, and other techniques; they found that the oxygen atom of aspartic acid-3 carboxyl group and the nitrogen atom of lysine-10 side chain amino group were involved in chelation (Fig. 2). The amino nitrogen and carboxyl oxygen atoms in the polypeptide identified by Xu et al. (2022)were also found to play an important role in binding calcium. Cui et al. (2018) studied the Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra before and after they combined calcium-binding peptide extracted from sea cucumber hydrolysate with calcium ion, and found that the vibration of amide-I band (C=O stretching vibration) shifted from 1668.12 cm−1 to 1667.90 cm−1 and that of amide-II band (N–H bending and C-N stretching vibrations) from 1544.31 to 1557.67 cm−1. They attributed these shifts to the vibration of the carboxylate group of the NDEELNK peptide. The vibration of N–H shifted from 3294.91 to 3399.94 cm−1, indicating that the calcium ions affected N–H band of the NDEELNK peptide. Kheeree et al. (2022) identified two polypeptides AFNRAKSKALNEN and YDSSGGPTPWLSPY from lemon basil seeds and found that the calcium binding reaction took place through the activity of amino nitrogen and carboxyl oxygen.

Fig. 2.

Combination of calcium ions and negatively charged carboxylic acid groups. (A) unidentate mode; (B) bidentate mode; (C) CIP mode

The combination of calcium ions and negatively charged carboxylic acid groups has two modes: the contact ion pair (CIP) and α mode. The CIP is the direct contact of two ions, whereas α mode is the binding of calcium ions to one oxygen atom and another suitable organic atom in carboxyl oxygen. The CIP state can be subdivided into a state in which two carboxyl oxygen atoms are coordinated with calcium ions (bidentate mode) and another in which only one oxygen atom is combined with calcium ion (unidentate mode) (Fig. 2) (Einspahr and Bugg 1981; Kahlen et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2018).

Moreover, Lemke et al. (2021) found that glutamate and aspartic acid interact differently with calcium. Aspartic acid tends to pull a large number of ions nearby, whereas glutamic acid is bound to the same calcium ion by multiple carboxylic acid groups.

Other modes

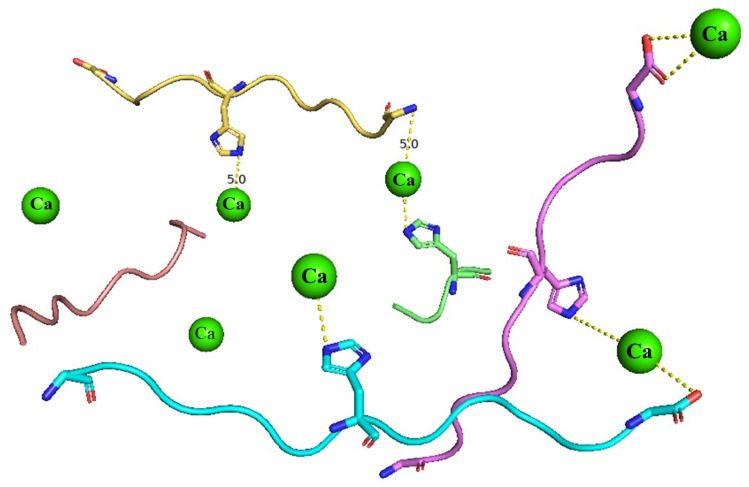

In addition to phosphoric, carboxyl, and amino groups, common ligands include the imidazolyl group of histidine (His), thio group of cysteine (Cys) and phenolic acid of tyrosine (Tyr). Chen et al. (2017) showed that peptide extracted from the skin of Alaskan cod, GPAGPHGPPG, have good calcium-binding ability and the δ-N of the imidazole ring of histidine is a binding site with divalent metal ions (Fig. 3) WEWLHYW is a calcium chelate peptide hydrolyzed from tilapia protein hydrolysates (Charoenphun et al., 2013), and Glu and His may play an important role in complexing with calcium ions. He et al. (2022) found that the carbonyl groups of Asp, Pro, Ser, and Lys residues involved the chelating of Ca2+ in their molecular simulation.

Fig. 3.

Chelating peptide (GPAGPHGPPG) derived from Alaska pollock skin binds with calcium on the δ-N of the imidazole ring of histidine

Although there have been a number of studies on the binding sites of calcium-binding peptides, further research on the structure relationship, stereochemical structure, and dynamic process of calcium peptide binding is needed.

Ratio

The ratio of peptides to metals vary greatly, and peptides can share electron pairs with metal ions and act as ligands. Owing to the high affinity of ligand molecules, the number of ligands is lower than or equal to that of metals, and proteins chelate calcium ions at a stoichiometric ratio of 1:3 (Liao et al., 2019). Similarly, the peptide in Xu et al. (2022) bound to calcium spontaneously at the stoichiometry of 1:1. However, if a ligand is a mixture of different peptides hydrolyzed from the same substance, MM cannot be determined but is indicated with a range. A peptide and metal is usually used in a mass/mass ratio. Therefore, drawing conclusions from the processes and results of binding in different mixtures with calcium ions is difficult. Tables 1 and 2 list the optimal proportion of protein hydrolysate or peptides combined with calcium ions from plant and animal sources, respectively.

The ratio of peptides to calcium ions depends on the type of ligand during some purification steps, the binding strength of peptides, and other factors. In general, the coordination amount should be higher than the metal content. This condition ensures that peptides are sufficient at all metal ion sites. The average affinity of these peptides is often lower than that of specific synthetic peptides (Caetano-Silva et al., 2020).

Molecular weight

Molecular weight has a significant effect on chelation reactions, and peptides with low molecular weights usually have high reactivity in the chelation process (Tian et al., 2021). Budseekoad et al. (2018) found that small peptides have more chelating activities than large peptides in mung bean protein hydrolysates with Ca2+. This may be due to when the molecular weight of a peptide is extremely large, bioactive groups hidden inside cannot be exposed, and biological activity cannot be observed. In contrast, side chains of small peptides expose more binding sites. Similar results were obtained in the study of Xu et al. (2022), the calcium binding capacity of peptide DGPSGPK (656.32 Da) obtained from tilapia bone protein hydrolysis could reach 111.98 µg/mg. By comparing the chelating abilities of cucumber seed peptides with different molecular weights with calcium, Wang et al. (2017) found that the chelating abilities of peptides smaller than 6 kDa were stronger than those of peptides larger than 6 kDa.

However, some peptides with large molecular weights can also show good metal-ion-chelating abilities. For example, sunflower seed peptides (1–3 kDa) and peanut peptides (≥ 10 kDa) have high Ca-binding content (Bao et al., 2021a). Ying et al. (2013) analyzed the chelating activity of soybean peptides for calcium and showed that the level of chelating activity of peptides with molecular weights between 10,000 and 30,000 Da was higher than that of peptides with molecular weights of less than 10,000 Da.

Inconsistencies among these experimental results may be related to the method used for separation, the effectiveness of separation, and the accuracy of peptide size estimation. The effects of molecular weight on metal chelating peptides and metal chelation activity needs further study.

Bioavailability evaluation

The bioavailability of minerals that the body can use can be characterized by the proportions of specific nutrients in a particular food or diet, that is, the accessibility of nutrients for normal metabolic and physiological processes. Metal-chelating peptides have some degree of resistance to gastrointestinal digestion and may be absorbed during gastrointestinal digestion. Therefore, the bioavailability of minerals requires bioactive peptides that support the transport of calcium from food to the intestinal mucosa during gastrointestinal digestion and prevent it from precipitating; calcium that reaches intestinal cells or passes through intestinal cells to reach target cells can be released from the complex (Guo et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2021). Table 3 lists the current industry applications of these complexes.

Table 3.

Application status of peptide-calcium chelates in the industry

| Protein source | Peptide-calcium complexes | Function | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calf skin; porcine skin | E7-BMP-2 peptide chelate calcium | Anti-resorption effect; osteoinductive effect | Mineralized nanofiber fragments | (Boda et al., 2020) |

| By-products of Chlamys farreri | Amino acids chelated calcium | Promote bone formation; inhibit bone resorption; improve bone microstructure | Functional food resource in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis | (Song et al., 2022) |

| Casein | Ca-CPP; Ca-dekCPP | Enhance the uptake of calcium ions | Dietary supplements | (Perego et al., 2015) |

| Mytilus edulis | PIE-Ca | Facilitate calcium uptake and proliferation of osteoblasts; inhibit bacteria | Efficient material for bone graft used during spinal surgery | (Xu et al., 2022) |

| Cattle bone | CPs-Ca | Improve digestion stability of calcium ions | Novel calcium supplement and high-value utilization of cattle bone | (Zhang et al., 2021a) |

| Egg white | Egg white peptide-calcium complex | Slow the release of calcium in gastric digestion | EWP-Ca-loaded nanoliposomes | (Zhang et al., 2021b) |

E7-BMP-2 heptaglutamate conjugated bone morphogenetic protein 2, Ca-CPP Natural CPP with calcium complexes, Ca-dekCPP synthetical CPP with calcium complexes, PIE IEELEEELEAER peptide, CPs cattle bone collagen peptides

Calcium peptide chelates can considerably improve the bioavailability of calcium ions. Methods for measuring and evaluating the bioavailability of calcium include the in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion, animal experiments, human colon cancer cell models, and experimental methods for humans.

In vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion

The in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion is a method for evaluating the bioavailability of calcium after the configuration of a simulated gastrointestinal fluid under human digestive tract conditions and then measuring calcium content in a digested sample after simulated digestion. By simulating gastrointestinal digestion using digestive enzymes in vitro, Chen et al. (2017) found that the calcium-chelating peptide GPAGPHGPPG, which was extracted from Alaskan cod skin, has good stability and most of the peptides (75%) remained intact after gastrointestinal enzyme digestion. They believed that the resistance of this peptide is related to its four proline residues. Cui et al. (2018) studied a combination of polypeptides extracted from sea cucumber eggs with calcium and found that a complex was produced after disaggregation and self-aggregation in a mesh during simulated gastrointestinal digestion. The possible mechanism needs further research.

Owing to differences between simulated gastrointestinal fluid and actual human gastrointestinal environment, the effectiveness of bioavailability needs to be further studied.

Animal experiment

The synthesis of metal-binding peptides has become a major endeavor, and in vivo studies have become possible. Rat models are widely used because of their short cycles and high homology between rat and human genes. Kai et al. (2018) synthesized a Pacific cod bone hydrolysate-calcium complex and confirmed that it improved intestinal calcium absorption and reduced the rate of bone loss in ovariectomized rats with osteoporosis. Peng et al. (2017) extracted collagen peptides with high affinity for calcium from blood and bone, and their results showed that the apparent absorption rate and retention rate of calcium-binding ossein group significantly improved compared with those of CaCO3 groups, that is, binding between calcium and bone collagen polypeptide improved the bioavailability of calcium. Bao et al. (2021b) compared the calcium absorption levels of egg white peptide calcium chelate and calcium chloride in a rat model and found that the group containing peptide and calcium showed better absorption capacity.

Owing to differences between animals and humans, many limitations hinder the extrapolation of the results of animal experiments to humans.

Human colon cancer cell model

The Caco-2 cell model was first proposed by Hidalgo et al. (1989) in 1989. The Caco-2 cell model is human-cloned colon adenocarcinoma cell. The structure and function of cultured cells are similar to those of human intestinal epithelial cells. This model is widely used in studying the absorption mechanism of trace elements and is an important tool in studying the bioavailability of calcium-peptide-conjugated compounds (Liao et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020).

Cui et al. (2018) studied the complexes of peptides extracted from sea cucumber eggs and combined with calcium ion by using a Caco-2 cell model. Hydrolyzed peptides in sea cucumbers can promote calcium absorption in the form of dietary supplements. Chen et al. (2017) extracted the chelating peptide GPAGPHGPPG from Alaskan cod skin and investigated its effect on mineral transport in Caco-2 cells. Their results showed that GPAGPHGPPG showed high stability in gastrointestinal enzyme digestion and significantly promoted calcium transport in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Similarly, Xu et al. (2022) demonstrated that calcium peptide binding promoted calcium uptake and proliferation of osteoblasts in Caco-2 cells.

Another type of human colon cancer cell is HT-29. Sun et al. (2017) studied the bioavailability of sea cucumber egg hydrolysate-calcium complexes. They found that these complexes improved the solubility of calcium under simulated gastrointestinal digestion conditions and promoted the absorption of calcium by Caco-2 and HT-29 cells.

The human colon cancer cell model has some shortcomings such as long culture time and susceptibility to contamination, but it has good homology and is currently recognized as the most ideal model for evaluating mineral element absorption.

Human experiment

In human experiments, calcium supplements are consumed by people with calcium deficiency, the content of calcium in the blood and urine samples of these people are measured and monitored for a specific period, and the bioavailability of calcium is evaluated (Samozai and Kulkarni 2015). Given that the human nutrition evaluation experiments are relatively complex, has long periods, heavy tasks, and low public acceptance, they are rarely used (Larder et al., 2021).

Overall, Minerals used for food fortification are usually used in inorganic forms, such as calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate, which have low bioavailability and can easily form deposits during gastrointestinal digestion. Natural metal-chelating peptides have been identified, which are of great significance to infants, the elderly, and the functional food industry. Although some peptide-metal complexes have been used in food fortification, research on the synthesis of peptide-metal complexes in food matrices is lacking, and a long time is needed before these complexes can be effectively used by the food industry. Peptide-metal chelates have potential as food ingredients for niche product rather than as replacement for metal salts. When selecting calcium supplements, we should also choose a suitable calcium supplement in combination with ourselves.

Although a level of understanding of structure activity relationships related to mineral-ligand binding has been achieved, further research on the physiological relationship between polypeptides as mineral carriers and gastrointestinal uptake is still needed. Moreover, the binding behavior of potential ligands in human diet needs to be further clarified and verified.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. U1904110, 32172259), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (Grant No. 212300410033), the Program for the Top Young Talents of Henan Associate for Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021), and the Innovative Funds Plan of Henan University of Technology (Grant No. 2021ZKCJ03).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Minghui Zhang, Email: zhangminghui12021@163.com.

Kunlun Liu, Email: knlnliu@126.com.

References

- Auestad N, Layman DK. Dairy bioactive proteins and peptides: a narrative review. Nutrition Reviews. 2021;79:36–47. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuab097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao XL, Lv Y, Yang BC, Ren CG, Guo ST. A study of the soluble complexes formed during calcium binding by soybean protein hydrolysates. Journal of Food Science. 2008;73:C117–C121. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Yuan X, Feng G, Zhang M, Ma S. Structural characterization of calcium-binding sunflower seed and peanut peptides and enhanced calcium transport by calcium complexes in Caco-2 cells. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2021;101:794–804. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao ZJ, Zhang PL, Sun N, Lin SY. Elucidating the calcium-binding site, absorption activities, and thermal stability of egg white peptide-calcium chelate. Foods. 2021;10:12. doi: 10.3390/foods10112565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boda SK, Wang HJ, John JV, Reinhardt RA, Xie JW. Dual delivery of alendronate and E7-BMP-2 peptide via calcium chelation to mineralized nanofiber fragments for alveolar bone regeneration. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2020;6:2368–2375. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budseekoad S, Yupanqui CT, Sirinupong N, Alashi AM, Aluko RE, Youravong W. Structural and functional characterization of calcium and iron-binding peptides from mung bean protein hydrolysate. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018;49:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Silva ME, Netto FM, Bertoldo-Pacheco MT, Alegria A, Cilla A. Peptide-metal complexes: obtention and role in increasing bioavailability and decreasing the pro-oxidant effect of minerals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;61:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1761770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Silva ME, Netto FM, Bertoldo-Pacheco MT, Alegria A, Cilla A. Peptide-metal complexes: obtention and role in increasing bioavailability and decreasing the pro-oxidant effect of minerals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2021;61:1470–1489. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1761770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XX, Lin JP, Wang SY. Novel peptide with specific calcium-binding capacity from Schizochytrium sp. protein hydrolysates and calcium bioavailability in Caco-2 cells. Marine Drugs. 2017;15:3–16. doi: 10.3390/md15010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XX, Yang Q, Lin JP, Fu NY, Wang SY. A specific peptide with calcium-binding capacity from defatted Schizochytrium sp. protein hydrolysates and the molecular properties. Molecules. 2017;22:544. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang GR, Tu MY, Chen YH, Chang KY, Chen CF, Lai JC, Tung YT, Chen HL, Fan HC, Chen CM. KFP-1, a novel calcium-binding peptide isolated from kefir, promotes calcium influx through TRPV6 channels. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2021;65:e2100182. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202100182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoenphun N, Cheirsilp B, Sirinupong N, Youravong W. Calcium-binding peptides derived from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) protein hydrolysate. European Food Research and Technology. 2013;236:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00217-012-1860-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Guo L, Du F, Chen T, Hou H, Li B. The chelating peptide (GPAGPHGPPG) derived from Alaska pollock skin enhances calcium, zinc and iron transport in Caco-2 cells. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2017;52:1283–1290. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Ji HW, Zhang ZW, Zeng XG, Su WM, Liu SC. A novel calcium-chelating peptide purified from Auxis thazard protien hydrolysate and its binding properties with calcium. Journal of Functional Foods. 2019;60:103447. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P, Lin S, Jin Z, Zhu B, Song L, Sun N. In vitro digestion profile and calcium absorption studies of a sea cucumber ovum derived heptapeptide-calcium complex. Food Function. 2018;9:4582–4592. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00910D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz de Barboza G, Guizzardi S, Tolosa de Talamoni N. Molecular aspects of intestinal calcium absorption. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;21:7142–7154. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Yu Y, Yan J, Jin Y. Tracking casein phosphopeptides during fermentation by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Chinese Journal of Chromatography. 2017;35:587–593. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2017.03012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einspahr H, Bugg CE. The geometry of calcium carboxylate interactions in crystalline complexes. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials. 1981;37:1044–1052. doi: 10.1107/S0567740881005037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esther M, Angel GJ, Amparo A, Reyes B, Rosaura F, Isidra R. Identification of casein phosphopeptides released after simulated digestion of milk-based infant formulas. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005;53:3426–3433. doi: 10.1021/jf0482111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Ruan G, Hao J, Regenstein JM, Wang F. Characterization and antioxidant properties of Manchurian walnut meal hydrolysates after calcium chelation. LWT - Food Science and Technology. 2020;130:109632. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felix B, Danielle P. Nutritional aspects of calcium absorption. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129:9–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Harnedy PA, Li B, Hou H, Zhang Z, Zhao X, FitzGerald RJ. Food protein-derived chelating peptides: biofunctional ingredients for dietary mineral bioavailability enhancement. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2014;37:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He JL, Guo H, Zhang M, Wang M, Sun LP, Zhuang YL. Purification and characterization of a novel calcium-binding heptapeptide from the hydrolysate of Tilapia bone with its osteogenic activity. Foods. 11: 468 (2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo IJ, Raub TJ, Borchardt RT. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:736–749. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(89)80072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou H, Wang S, Zhu X, Li Q, Fan Y, Cheng D, Li B. A novel calcium-binding peptide from Antarctic krill protein hydrolysates and identification of binding sites of calcium-peptide complex. Food Chemistry. 2018;243:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Sheehan JH, Chazin WJ. The mode of action of centrin. binding of Ca2+ and a peptide fragment of Kar1p to the C-terminal domain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:50895–50903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Lan YQ, Liao WW, Lin L, Liu G, Xu HM, Xue JP, Guo BY, Cao Y, Miao JY. Preparation, characterization and biological activities of egg white peptides-calcium chelate. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 2021;149:112035. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung W, Karawita R, Heo S, Lee B, Kim S, Jeon Y. Recovery of a novel Ca-binding peptide from Alaska Pollack (Theragra chalcogramma) backbone by pepsinolytic hydrolysis. Process Biochemistry. 2006;41:2097–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2006.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlen J, Salimi L, Sulpizi M, Peter C, Donadio D. Interaction of charged amino-acid side chains with ions: an optimization strategy for classical force fields. Journal of Physical Chemistry b. 2014;118:3960–3972. doi: 10.1021/jp412490c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai Z, Bafang L, Qianru C, Zhaohui Z, Xue Z, Hu H. Functional calcium binding peptides from Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) bone: calcium bioavailability enhancing activity and anti-osteoporosis effects in the ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis rat model. Nutrients. 2018;10:1325–1340. doi: 10.3390/nu10091325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Singh J, Devgon I, Khan MA, Jangra S. Hydrolysis Method For Preparation Of Bioactive Peptides. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research. 2019;6:626–634. [Google Scholar]

- Kheeree N, Kuptawach K, Puthong S, Sangtanoo P, Srimongkol P, Boonserm P, Reamtong O, Choowongkomon K, Karnchanatat A. Discovery of calcium-binding peptides derived from defatted lemon basil seeds with enhanced calcium uptake in human intestinal epithelial cells, Caco-2. Scientific Reports. 2022;12:4659. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08380-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larder CE, Iskandar MM, Kubow S. Gastrointestinal digestion model assessment of peptide diversity and microbial fermentation products of collagen hydrolysates. Nutrients. 2021;13:2720. doi: 10.3390/nu13082720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen T, Thilsted SH, Kongsbak K, Hansen M. Whole small fish as a rich calcium source. British Journal of Nutrition. 2000;83:191–196. doi: 10.1017/S0007114500000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke T, Edte M, Gebauer D, Peter C. Three reasons why aspartic acid and glutamic acid sequences have a surprisingly different influence on mineralization. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2021;125:10335–10343. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c04467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao WW, Liu SJ, Liu XR, Duan S, Xiao SY, Yang ZN, Cao Y, Miao JY. The purification, identification and bioactivity study of a novel calcium-binding peptide from casein hydrolysate. Food and Function. 2019;10:7724–7732. doi: 10.1039/C9FO01383K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao WW, Chen H, Jin WG, Yang ZN, Cao Y, Miao JY. Three newly isolated calcium-chelating peptides from tilapia bone collagen hydrolysate enhance calcium absorption activity in intestinal Caco-2 cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2020;68:2091–2098. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YL, Cai XX, Wu XP, Lin SN, Wang SY. Fabrication of snapper fish scales protein hydrolysate-calcium complex and the promotion in calcium cellular uptake. Journal of Functional Foods. 2020;65:103717. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BT, Zhuang YL, Sun LP. Identification and characterization of the peptides with calcium-binding capacity from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin gelatin enzymatic hydrolysates. Journal of Food Science. 2020;85:114–122. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Lu W, Dai X, Qu X, Zhu C. The role of TRPV channels in osteoporosis. Molecular Biology Reports. 2021;49:577–585. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06794-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo MN, Xiao J, Sun SW, Cui FC, Li W, Liu G, Li YQ, Cao Y. Deciphering calcium-binding behaviors of casein phosphopeptides by experimental approaches and molecular simulation. Food and Function. 2020;11:5284–5292. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00844C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JQ, Yao XT, Soladoye OP, Zhang YH, Fu Y. Phosphorylation modification of collagen peptides from fish bone enhances their calcium-chelating and antioxidant activity. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 2022;155:112978. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y, Liu H, Ren J, Li X, Guo S. The positive effect of soybean protein hydrolysates-calcium complexes on bone mass of rapidly growing rats. Food Function. 2013;4:1245–1251. doi: 10.1039/c3fo30284a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GD, Jarvis JK, McBean LD. The importance of meeting calcium needs with foods. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2001;20:168S–185S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel E, Alegría A, Barberá R, Farré R. Casein phosphopeptides released by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of infant formulas and their potential role in mineral binding. International Dairy Journal. 2005;16:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2005.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlos M, Znamirowska A, Zagula G, Buniowska M. Use of calcium amino acid chelate in the production of acid-curd goat cheese. Foods. 2020;9:994. doi: 10.3390/foods9080994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Hou H, Zhang K, Li B. Effect of calcium-binding peptide from Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) bone on calcium bioavailability in rats. Food Chemistry. 2017;221:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego S, Del Favero E, De Luca P, Dal Piaz F, Fiorilli A, Cantu L, Ferraretto A. Calcium bioaccessibility and uptake by human intestinal like cells following in vitro digestion of casein phosphopeptide-calcium aggregates. Food Function. 2015;6:1796–1807. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00672K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samozai MN, Kulkarni AK. Do calcium supplements increase serum and urine calcium levels in post-menopausal women? Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging. 2015;19:537–541. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JL, Liu GF, Song YH, Jiao K, Wang SL, Cao TF, Yu J, Wei YX. Positive effect of compound amino acid chelated calcium from the shell and skirt of scallop in an ovariectomized rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2022;102:1363–1371. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Wu H, Du M, Tang Y, Liu H, Fu Y, Zhu B. Food protein-derived calcium chelating peptides: A review. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2016;58:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Cui P, Lin S, Yu C, Tang Y, Wei Y, Xiong Y, Wu H. Characterization of sea cucumber (stichopus japonicus) ovum hydrolysates: calcium chelation, solubility and absorption into intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2017;97:4604–4611. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Liu F, Liu G, Miao J, Xiao H, Xiao J, Qiu Z, Luo Z, Tang J, Cao Y. Effects of casein phosphopeptides on calcium absorption and metabolism bioactivity in vitro and in vivo. Food Function. 2018;9:5220–5229. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00401C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Wang YX, Bao ZJ, Cui PB, Wang S, Lin SY. Calcium binding to herring egg phosphopeptides: Binding characteristics, conformational structure and intermolecular forces. Food Chemistry. 2020;310:125867. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian QJ, Fan Y, Hao L, Wang J, Xia CS, Wang JF, Hou H. A comprehensive review of calcium and ferrous ions chelating peptides: preparation, structure and transport pathways. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2021;11:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.2001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda EKM, Gout PW, Morganti L. Current and prospective applications of metal ion–protein binding. Journal of Chromatography a. 2003;988:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)02057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci L, Fossi C, Quattrini S, Guasti L, Pampaloni B, Gronchi G, Giusti F, Romagnoli C, Cianferotti L, Marcucci G, Brandi ML. Calcium intake in bone health: a focus on calcium-rich mineral waters. Nutrients. 2018;10:1930. doi: 10.3390/nu10121930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gao A, Chen Y, Zhang X, Li S, Chen Y. Preparation of cucumber seed peptide-calcium chelate by liquid state fermentation and its characterization. Food Chemistry. 2017;229:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Li B, Hou H, Zhang H, Zhao X. Isolation and identification of calcium-chelating peptides from Pacific cod skin gelatin and their binding properties with calcium. Food Function. 2017;8:4441–4448. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01014A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WM, He LC, Liang YH, Yue LL, Peng WM, Jin GF, Ma MH. Preparation process optimization of pig bone collagen peptide-calcium chelate using response surface methodology and its structural characterization and stability analysis. Food Chemistry. 2019;284:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Zhu ZX, Chen H, Han LY, Shi PJ, Dong XF, Wu D, Du M, Li TT. Application of a Mytilus edulis-derived promoting calcium absorption peptide in calcium phosphate cements for bone. Biomaterials. 2022;282:121390. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying L, Xiaolan B, He L, Jianhua R, Shuntang G. Purification and characterization of calcium-binding soybean protein hydrolysates by Ca2+/Fe3+ immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) Food Chemistry. 2013;141:1645–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes M, Aggett P, Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Dusemund B, Filipic M, Frutos MJ, Galtier P, Gundert-Remy U, Kuhnle GG, Lambre C, Leblanc JC, Lillegaard IT, Moldeus P, Mortensen A, Oskarsson A, Stankovic I, Waalkens-Berendsen I, Woutersen RA, Wright M, McArdle H, Tobback P, Pizzo F, Rincon A, Smeraldi C, Gott D, Nutrient EPFA. Evaluation of di-calcium malate, used as a novel food ingredient and as a source of calcium in foods for the general population, food supplements, total diet replacement for weight control and food for special medical purposes. European Food Safety Authority Journal. 2018;16:e05291. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Li J, Hou H, Zhang H, Li B. Purification and characterization of a novel calcium-biding decapeptide from Pacific cod (Gadus Macrocephalus) bone: molecular properties and calcium chelating modes. Journal of Functional Foods. 2019;52:670–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.11.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HR, Zhao LY, Shen QS, Qi LW, Jiang S, Guo YJ, Zhang CH, Richel A. Preparation of cattle bone collagen peptides-calcium chelate and its structural characterization and stability. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 2021;144:111264. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PL, Bao ZJ, Jiang PF, Zhang SM, Zhang XM, Lin SY, Sun N. Nanoliposomes for encapsulation and calcium delivery of egg white peptide-calcium complex. Journal of Food Science. 2021;86:1418–1431. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XW, Jia Q, Li MY, Liu HP, Wang Q, Wu YR, Niu LL, Liu ZT. Isolation of a novel calcium-binding peptide from phosvitin hydrolysates and the study of its calcium chelation mechanism. Food Research International. 2021;141:110169. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HX, Yang Y, Shu X, Wang YW, Wu SS, Ran QP, Liu JP. The binding of calcium ion with different groups of superplasticizers studied by three DFT methods, B3LYP, M06–2X and M06. Computational Materials Science. 2018;152:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.05.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao MD, Li SS, Ahn DU, Huang X. Phosvitin phosphopeptides produced by pressurized hea-trypsin hydrolysis promote the differentiation and mineralization of MC3T3-E1 cells via the OPG/RANKL signaling pathways. Poultry Science. 2021;100:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]