Abstract

The high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in various human diseases. However, a systematic, comprehensive pan‐cancer analysis of HMGB1 in human cancers remains to be reported. This study analysed the genetic alteration, RNA expression profiling and DNA methylation of HMGB1 in more than 30 types of tumours. It is worth noting that HMGB1 is overexpressed in malignant tissues, including lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) and thymoma (THYM). Interestingly, there is a positive correlation between the high expression of HMGB1 and the high survival prognosis of THYM. Finally, this study comprehensively evaluates the genetic variation of HMGB1 in human malignant tumours. As a prospective biomarker of COVID‐19, the role that HMGB1 plays in THYM is highlighted.

Keywords: bioinformatics, COVID‐19 biomarker, expression, HMGB1, pan‐cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Some studies have recently recognized high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a potential biomarker for severe COVID‐19. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The serum HMGB1 of patients with severe COVID‐19 is significantly elevated. In some circumstances, exogenous HMGB1 could promote the entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 into alveolar epithelial cells expressing the receptor ACE2. 2 Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the HMGB1‐AGR pathway can play an important role in blocking the expression of ACE2. HMGB1 is a multifunctional protein that plays different roles in different cell compartments. Extracellular HMGB1 is considered a damage‐associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein in response to stress, which serves as the central mediator of lethal systemic inflammation in tissue injury or infection. Alarmins are constitutive endogenous molecules that are released and activate the immune system in the event of tissue injury. 5 , 6 , 7 HMGB1 is one of the prototypical alarmins that activate innate immunity. 8 In addition, although the number of references to alarmins in the literature is increasing rapidly, the one most characteristic in health and disease is HMGB1. Finally, it is worth noting that cancer is known as one of the individual risk factors for COVID‐19, and many of the affected patients with COVID‐19 are patients with malignant tumours. 9 During the current COVID‐19 outbreak, one of the potential risks for cancer patients is the limited ability to access to necessary medical services. Furthermore, patients with lung cancer who are ≥60 years of age tend to have higher risks for COVID‐19 infection. 9 , 10 However, comprehensive pan‐cancer analyses have yet to be conducted to investigate the potential impact of HMGB1 aberration in human cancers. 11 , 12

Here, we conducted a pan‐cancer analysis of HMGB1 in malignant tumours. In the TCGA pan‐cancer analysis, the most common genetic alterations were investigated. Next, the expression of HMGB1 in tumour tissues and normal control tissues was compared. Since the new COVID‐19 is mainly transmitted through the air, one focus should be respiratory tumours. Furthermore, this study studied the genetic disorders of HMGB1 in cancer. Interestingly, COVID‐19 is related to aging and inflammatory diseases, and a dysfunctional thymus may be the predisposing factor. 13 , 14 We report that HMGB1 plays an important role in THYM. This result highlights the relationship between COVID‐19 patients and the disorders of the thymus gland through bioinformatics tools.

2. METHODS

2.1. Gene expression analysis of HMGB1

Initially, the tumour immune‐estimation resource, version 2 (TIMER2) webserver (http://timer.cistrome.org/) was used to investigate the mRNA expression difference of HMGB1 between tumour and normal tissues for the different tumours derived from the TCGA project. However, there are specific tumours with no normal tissues or very limited normal tissues in the TCGA project. For these tumours, the GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer‐pku.cn/, the gene expression profiling interactive analysis 2) webserver was used to compare box plots of the mRNA expression difference between the tumour tissues and the corresponding normal tissues of the genotype‐tissue expression (GTEx) database. 15

To determine the difference in HGMB1 protein expression between tumour tissues and the normal tissues, analyses of protein expression were performed on the Clinical Proteomic Tumour Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) datasets using the UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu). 16 Six tumours were available: breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colon cancer, renal cell cancer, endometrial cancer and lung adenocarcinomas. The UALCAN is a comprehensive and interactive web resource for analysing cancer OMICS data, including TCGA, MET500 and CPTAC. 16 Furthermore, this study investigated HMGB1 expression at different pathological stages across cancer types using the GEPIA2 stage‐plot module. The cut‐off value was set to 50% to separate the groups into high‐ and low‐expression cohorts.

2.2. Survival prognosis of HMGB1

GEPIA2 was also used to perform custom statistical methods, such as survival analyses on a given dataset to obtain differentially expressed genes or isoforms dynamically. The survival‐map module in GEPIA2 was applied to generate plots for overall survival (OS) and disease‐free survival (DFS). The cut‐off value was 50% to separate the groups into high‐ and low‐expression cohorts. The log‐rank test was used for hypothesis testing. The comparison/survival module, p‐Values, q‐Values and Kaplan–Meier plots of Disease‐Free, Overall, Disease‐specific and Progression‐Free were obtained for TCGA cases. Statistical analyses were performed using the ‘survival’ package with R statistical software, version 4.0.5.

2.3. DNA methylation and genetic alteration analyses

The DNA methylation level of HMGB1 was analysed using the methylation panel from the CGA module via UALCAN. 17 , 18 More than 30 tumours were available for the analyses.

The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal (cBioPortal, https://www.cbioportal.org/) is a user‐friendly and exploratory analysis tool for investigating multidimensional cancer genomic data sets. 1 , 19 Genetic alterations of HMGB1 in pan‐cancer were explored by the cBioPortal. The results of the mutations, amplifications, profound deletions and Copy number alteration (CNA) were gathered. The schematic diagram of the three‐dimensional (3D) structure of HGMB1 mutations was shown in a graphic panel in the mutations module.

2.4. Immune infiltration analysis of HMGB1

The Immune‐Estimation module of the TIMER2 webserver was used to explore the association between the level of HMGB1 expression and the abundance of immune cells of CD8+ T‐cells and cancer‐associated fibroblasts. The TIMER, EPIC, MCP‐COUNTER, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT‐ABS, QUANTISEQ and XCELL algorithms were applied to estimate immune infiltration. The results are demonstrated by both heatmap and scatter plots. In addition, the p‐values and partial correlation (partial_cor) values were calculated using the purity‐adjusted Spearman's test.

2.5. Gene‐related enrichment analysis

The STRING website (https://string‐db.org/) was applied to search HMGB1 under the protein name section in Homo sapiens organism. 20 , 21 The main parameters under the settings panel were set by checking (evidence) for the meaning of network edges and (Experiments) for active interaction sources. In addition, we selected (low confidence [0.150]) for the minimum required interaction score and (no more than 50 interactors) for the maximum number of interactors. Using these settings, 50 top HGMB1‐binding proteins were identified for further analysis.

The ‘Similar Gene Detection’ panel on the GEPIA2 webserver was applied to obtain the top 100 HGMB1‐correlated targeting genes based on the datasets from all TCGA tumours and normal tissues. Pearson correlation analysis of selected genes was conducted using the ‘Correlation Analysis’ module. The p‐value and the correlation coefficient were provided. TIMER2 produced the heatmaps; these contain the p‐values and partial correlation in the purity‐adjusted Spearman's test. The intersection analysis of the HMGB1‐binding and interacted genes was completed using a Venn diagram. Finally, the enriched pathway analyses were analysed using ‘clusterProfiler’ in R statistical software, version 4.0.5, and the bubble plots were produced by ‘tidyr’ and ‘ggplot2’ packages.

3. RESULTS

3.1. HMGB1 is overexpressed in three tumours out of 33 tumours

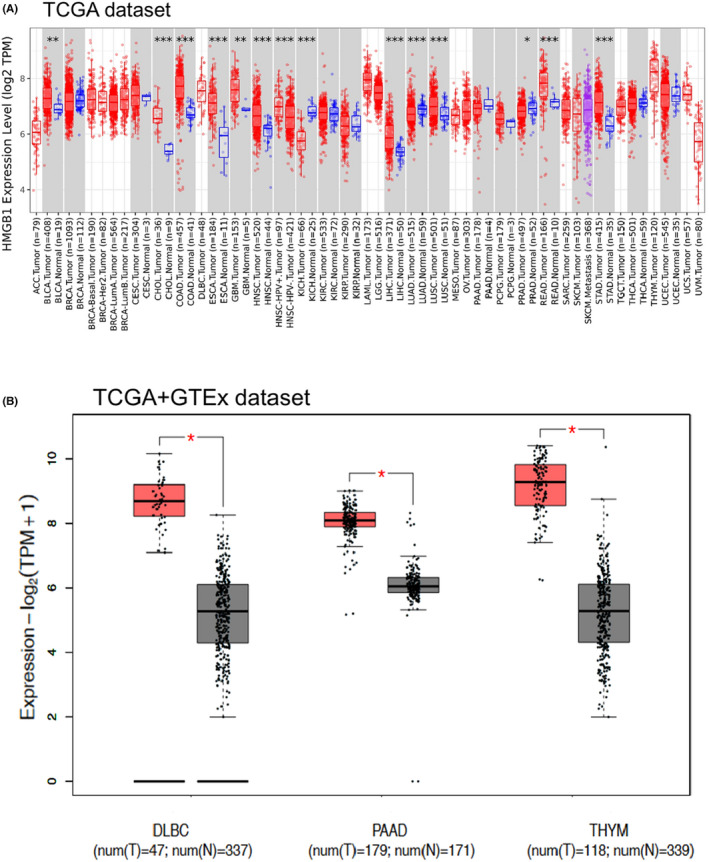

Initially, the expression pattern of HMGB1 was analysed across various cancer types of TCGA using TIMER2. As shown in Figure 1A, the expression levels of HMGB1 in the tumour tissues of CHOL (Cholangiocarcinoma), COAD (Colon adenocarcinoma), ESCA (Oesophageal carcinoma), HNSC (Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma), KICH (Kidney Chromophobe), LIHC (Liver hepatocellular carcinoma), LUAD (Lung adenocarcinoma), LUSC (Lung squamous cell carcinoma), READ (Rectum adenocarcinoma) and STAD (Stomach adenocarcinoma) are significantly different compared with the corresponding normal tissues (p < 0.001). Among them, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, LIHC, LUSC, READ and STAD are significantly higher expressed in tumour groups, while KICH and LUAD are lower expressed in the tumour groups.

FIGURE 1.

RNA expression of HMGB1 in different tumours using TCGA and GTEx datasets. (A) The expression status of the HMGB1 in different cancers or specific cancer subtypes was analysed through TIMER2. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (B) For the type of DLBC, PAAD and THYM in the TCGA project, the corresponding normal tissues of the GTEx database were included as controls. The red colour represents tumour groups, and grey represents normal controls

After combining the data from GTEx using GEPIA2 (Figure 1B), DLBC, PAAD and THYM presented the most significantly increased HMGB1 expression (log2FC = 2 and p < 0.001, Figure 1B). Because COVID‐19 is mainly transmitted through the airway, we focused on respiratory system tumours, such as LUAD, LUSC and THYM. However, HMGB1 remained unchanged in LUSC and only slightly increased in LUAD, the p‐value is not significant for LUAD.

The results of the CPTAC dataset showed lower expression of HMGB1 total protein in the primary tissues of breast cancer, lung cancer and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC; Figure S1, p < 0.001) than in normal controls but not others. The ‘Pathological Stage Plot’ module of GEPIA2 was used to examine whether HMGB1 expression may differ in different pathological stages of tumours. The outcomes indicated that HMGB1 expression levels were significantly associated with the clinical stage of the following cancer types: Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) (p‐value = 0.0239), LIHC (p‐value = 0.0209), SKCM (p‐value = 0.0133) and THCA (p‐value = 0.0348) but not others (Figure S2).

3.2. Overexpression of HMGB1 is linked to poor prognosis in five tumours

After examining the significant dysregulation of HMBG1 expression in different cancer types and its correlation with the pathological stage, one potential hypothesis is that this protein might be used as a prognostic indicator for certain cancer types. The cancer samples were divided into high‐ and low‐expression groups based on the expression levels of HMGB1. Then, the associations between the expression level of HMGB1 and prognostic significance with different tumours derived from TCGA and GEO databases were investigated.

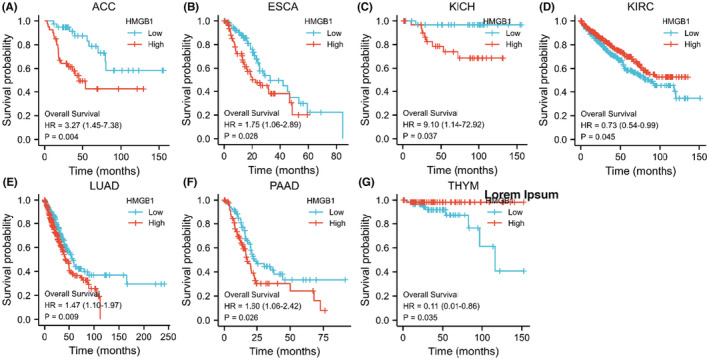

As shown in Figure 2, highly expressed HMGB1 was significantly associated with Overall Survival (OS) for cancers of ACC (p = 0.004), ESCA (p = 0.028), KICH (p = 0.037), KIRC (p = 0.045), LUAD (p = 0.009), PAAD (p = 0.026) and THYM (p = 0.035). DFS analysis showed that high HMGB1 expression is significantly correlated with poor prognosis for only HNSC (p = 0.025). These results indicated that the level of HMGB1 expression is differentially associated with the prognosis of different cancer types. Three tumours (DLBC, PAAD and THYM) presented significantly elevated HMGB1 expression. Both DFS and OS results demonstrated no direct relationship between HMGB1 expression and patient prognosis.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival (OS) data in HMGB1 abnormally expressed malignancies. In the different malignancies, the OS data are not directly related to the expression levels of HMGB1

This study showed that, compared with normal samples, the RNA expression of HMGB1 was not significantly up‐ or down‐regulated in LUADs. However, both the OS and DFS results of HMGB1 showed that the higher expression of HMGB1 could lead to significantly poorer patient outcomes in LUAD (Figure S3). This may indicate that RNA expression of HMGB1 is not correlated with patient outcomes. The DFS and OS are not significant for HMGB1 in LUSC (Figure S3). The HMGB1 serves as a double‐edged sword for patients with different tumours. For example, for OS, higher HMGB1 expression indicates a better prognosis in KIRC and THYM, but a significantly unfavourable outcome in ACC, ESCA, KICH, LUAD, PAAD and PRAD.

3.3. DNA methylation and genetic alteration analysis

Eleven probes in the HMGB1 promoter were used in this study to detect the DNA methylation level of HMGB1 (Figure S4). Interestingly, for respiratory system‐related tumours, such as LUAD, LUSC and THYM, the DNA methylation levels of HMGB1 were all decreased. There are three tumours (DLBC, PAAD and THYM) with the higher mRNA expression levels of HMGB1. However, the DNA methylation level of HMGB1 for these three tumours are not consistent. For example, PAAD with upregulated HMGB1 presented a significantly decreased DNA methylation level. Conversely, one HMGB1 upregulated tumour, THYM, presented a slightly upregulated DNA methylation level.

Furthermore, because there is no available DNA methylation dataset for DLBC normal control, the comparison analyses were conducted across different patient populations. Similarly, the comparison is not statistically significant for DLBC. These results confirmed that abnormal HMGB1 expression was not solely due to DNA methylation. Further exploration should be done for histone modifications and glycosylation. 22 , 23

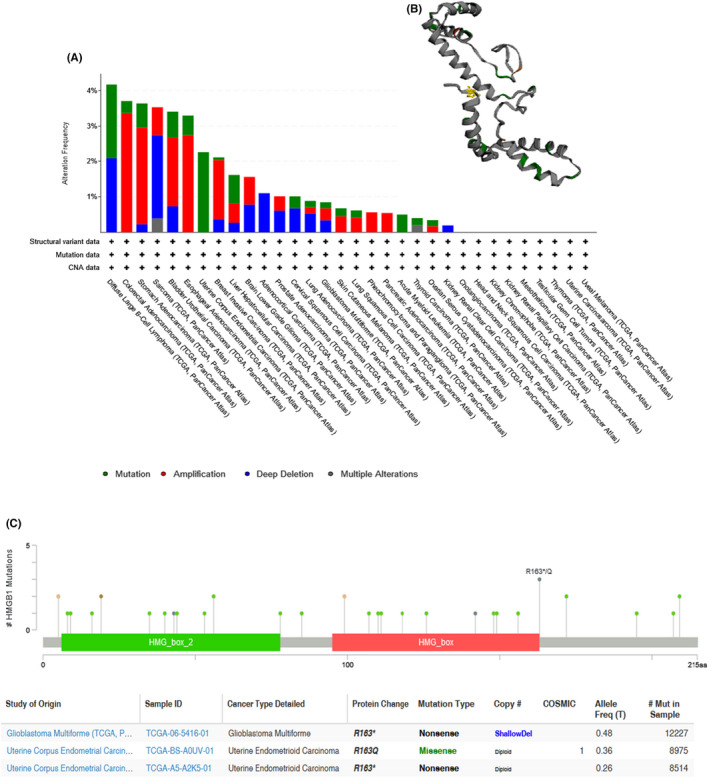

Genetic alterations of HMGB1 were observed among different cancer samples from the TCGA database. The pan‐cancer analysis of HMGB1 in different malignancies demonstrates that the most frequent DNA alterations are amplification, mutations and deep deletions in the TCGA pan‐cancer panel (Figure 3A). Amplification was mainly distributed in COAD, STAD, bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) and ESCA. Mutations were mainly distributed in DLBC, UCEC and LIHC. The most frequent deep deletions were observed in DLBC, sarcoma (SARC) and ACC patients (Figure 3A). For DLBC, SARC and ACC patients, the deep deletions appeared more than 50% in alteration frequency. In addition, HMGB1 mutations in different malignancies were distributed across HMG_box and HMG_box_2 domains without hot spot mutation sites (Figure 3C). The most observed frequent mutation was R163*/Q; the 3D structure of the HMGB1 mutations is shown in a graphic panel (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Genetic variation of HMGB1 in different tumours. (B) The 3D structure of HMGB1 mutations. The yellow colour highlighted the mutation R163*/Q. (C) HMGB1 mutations were distributed across all exons of HMGB1 without hot spot mutation site in TCGA cohort using cBioPortal

The results showed that mutations were not statistically relevant to RNA expression of HMGB1 (Figure S5). Furthermore, copy variations were also not significantly relevant to HMGB1 expression (Figure S5). One possible explanation is that the upregulation of HMGB1 expression is not a direct consequence of genetic variation. Thus, we further investigated the post‐translation features of HMGB1 in 33 cancers.

3.4. Phosphorylation levels of HMGB1 in several cancers

The differences in HMGB1 phosphorylation levels were compared between normal tissue and primary tumour tissues using CPTAC datasets for four types of tumours (breast cancer, clear cell carcinoma, LUAD and UCEC). Figure S6 summarizes the phosphorylation sites of HMGB1, which are significantly different from the control group: S35 locus and S100 locus. The S35 locus demonstrates a significantly lower phosphorylation level in primary tumour tissues compared with normal tissues for breast cancer (p = 2e‐05), LUAD (p = 6e‐38) and UCEC (p = 9e‐06) (Figure S6). By contrast, the S100 locus is the only one to exhibit a significantly decreased phosphorylation level for breast cancer (Figure S6, p = 2e‐04), but not for LUAD and UCEC.

3.5. Immune infiltration analysis

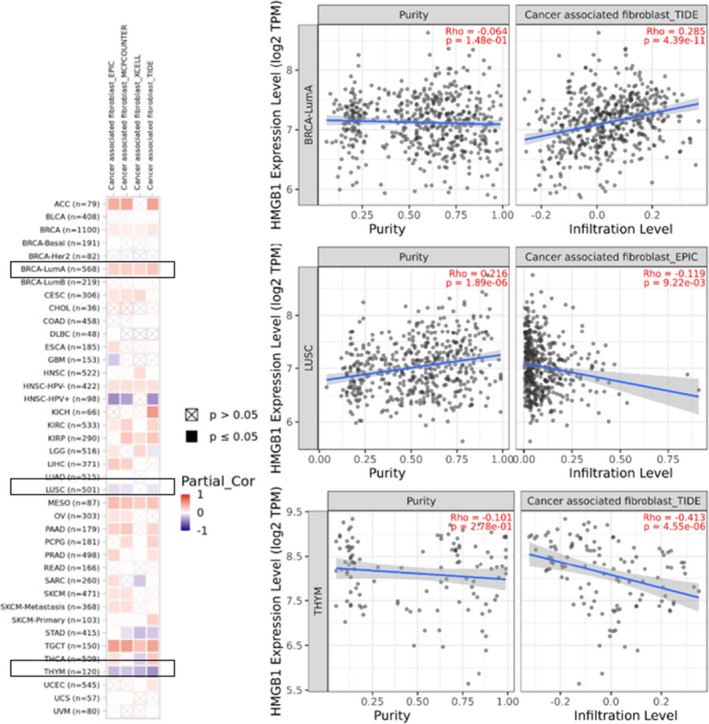

As an important part of the tumour microenvironment, tumour‐infiltrating immune cells were reported to be closely related to the initiation, promotion, progression or metastasis of tumours. 24 , 25 Furthermore, according to previous research, cancer‐associated fibroblasts regulate the functions of various cancer‐infiltrating immune cells. 26 , 27 Therefore, the algorithms of TIMER, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT‐ABS, QUANTISEQ, XCELL, MCPCOUNTER and EPIC were used to study the potential relationship between the expression of HMGB1 and the infiltration level of different immune cells in TCGA for different tumour types.

After a series of analyses, statistically positive correlations were observed between HMGB1 expression and CD8+ T‐cell immune infiltration in HNSC‐HPV+, LUAD, LUSC and THYM based on seven out of the ten algorithms (Figure S7). These positive correlations do not infect the prognosis directly. In addition, the positive correlations were detected between HMGB1 expression and the immune infiltration of cancer‐associated fibroblasts in the TCGA tumours of BRCA‐LumA, MESO and TGCT based on all or most algorithms (Figure S8). The negative correlations were detected between HMGB1 expression and the immune infiltration of cancer‐associated fibroblasts in the TCGA tumours of HNSC_HPV+ based on all or most algorithms. The scatter plots of these tumours were also provided for one of the most significant algorithms. For example, the expression level of HMGB1 in THYM is statistically positively correlated with the infiltration level of cancer‐associated fibroblasts (Figure 4, cor = −0.413, p = 4.55e‐06) based on the TIDE algorithm.

FIGURE 4.

Relationship between HMGB1 expression and cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Four algorithms (EPIC, MCPCOUNTER, XCELL and TIDE) were used to investigate the possible relationship between HMGB1 expression and infiltration of CAF in various cancer types. The right panel shows the correlation and scatterplot for the three selected cancer types

3.6. Enrichment of HMGB1‐related partners

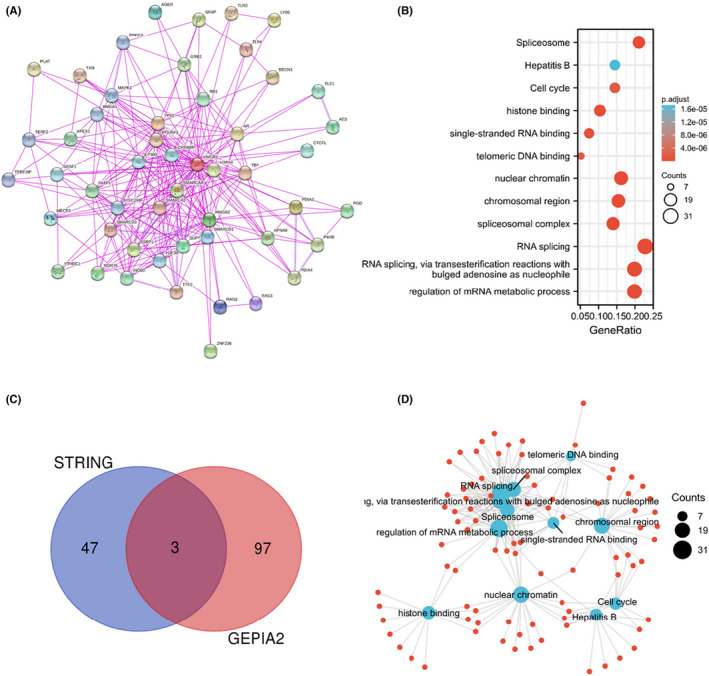

To further explore the molecular mechanism of HMGB1 in tumorigenesis, the HMGB1 expression‐related genes or proteins were obtained from a series of pathway enrichment analyses. First, 50 binding proteins were observed using the STRING tool, all supported by experimental evidence. The interaction network of these proteins is presented in Figure 5. Next, based on the GEPIA2 tool, the top 100 genes related to HMGB1 expression were obtained by combining all tumour expression data of TCGA. Finally, the two datasets were combined to perform further KEGG and GO enrichment analyses.

FIGURE 5.

Enrichment analysis of the HMGB1 gene. (A) Fifty proteins that bind to HMGB1 were identified using the STRING tool. In addition, 100 genes associated with HMGB1 were acquired from the TCGA database. (B) KEGG pathway analysis based on the HMGB1‐binding and interacted genes. (C) An intersection analysis of the HMGB1‐binding and correlated genes was conducted. (D) The cnetplot for the molecular function data in GO analysis

An intersection analysis of these two datasets contained three common members (HMGB2, SRSF1 and SSRP1). Moreover, the related heat maps demonstrated that there are positive correlations between HMGB1 and RP11‐673C5.1 (R = 0.87), HMGB1P5 (R = 0.69), EXOSC8 (R = 0.69), HNRNPA2B1 (R = 0.68), SRSF3 (R = 0.67), MED4 (R = 0.65), RFC3 (R = 0.63) and HNRNPR (R = 0.63). These positive correlations are statistically significant (all P < 0.001). In addition, the corresponding heat map demonstrates that in most cancer types, there is a positive correlation between HMGB1 and the above five genes (Figure S9).

The two data sets (obtained by STRING and GEPIA2) were combined for further KEGG and GO enrichment analysis. The KEGG and GO results highlight the following potential pathways: ‘RNA splicing’, ‘RNA splicing, via transesterification reactions with bulged adenosine as a nucleophile’ and ‘regulation of mRNA metabolic process’ in biological processes (BP) GO components and ‘Spliceosome’ in the KEGG pathway database (Figure 5).

4. DISCUSSION

Emerging applications report the functional link between HMGB1 and clinical diseases, especially COVID‐19. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 However, the role of the multifunctional HMGB1 in the molecular pathogenesis of different tumours remains unclear. This study analysed the genetic changes, RNA expression, protein expression and DNA methylation of HMGB1 in more than 30 tumours. A significant overexpression of HMGB1 was observed in DLBC, PAAD and THYM. The correlation analysis of HMGB1 and survival prognosis has also been performed. In addition, low DNA methylation of HMGB1 was found in most tumours with high HMGB1 expression. The result of genetic alterations (Figure 3A) demonstrates that the most frequent DNA alterations are amplification, mutations and deep deletions. The patterns of genetic alterations for HMGB1 differ across cancer types. For DLBC, both the mutations and deep deletions were observed in DLBC patients. For SARC, the most frequent genetic alterations are deep deletions. In conclusion, this study investigates the genetic variation of HMGB1 in human malignant tumours.

LUAD is the most common type among the COVID‐19 patients with malignant tumours. 28 , 29 In addition, lung cancer patients have been confirmed to have a higher COVID‐19 incidence and more severe symptoms. 28 , 29 Here, we demonstrated that RNA expression of HMGB1 is significantly upregulated in THYM patients but not significantly changed in LUAD and LUSC. The phosphorylation analyses using the CPTAC dataset included four cancer types. Results demonstrated the decreased phosphorylation levels of S35 and S100 for different tumours. Furthermore, the findings showed that compared with the normal control group, the total protein and phosphorylation level of HMGB1 at the S35 locus in the primary tumour was significantly lower for breast cancer, LUAD and UCEC (Figure S6, all p < 0.01). However, the total protein levels of HMGB1 were significantly higher for both ovarian cancer and colon cancer. Although the clinical significance of these post‐translational modification sites remains to be determined, the current analyses do not rule out the possibility that the significantly decreased level of HMGB1 phosphorylation of S35 is a by‐product of a functionally significant dysregulated signal in tumour cells. In addition, more experiments are needed to evaluate further the potential role of S35 and S100 phosphorylation of HMGB1 and the role of related cell cycle regulation in tumorigenesis.

The significant changes of phosphorylation are consistent with the expression level of HMGB1 total protein between normal tissue and primary tissue for breast cancer, clear cell RCC and UCEC (Figure S1 and Figure S6). The change of phosphorylation is not directly correlated with expression of HMGB1 (Figure 1 and Figure S6). Moreover, there are statistically positive correlations observed between HMGB1 expression and CD8+ T‐cell immune infiltration in HNSC‐HPV+, LUAD, LUSC and THYM, however, these positive correlations do not infect the prognosis directly (Figure 2 and Figure S7). Interestingly, the high expression of HMGB1 is related to the significantly increased survival rate for THYM, based on the OS result for HMGB1 (Figure 2), which may indicate the potential function of HMGB1 in specific tumours.

As this is a pan‐cancer analysis and the presented results show that the function of HMGB1 is different in different cancer types, and the relationship of prognosis are different from the results of immune infiltrations. These results demonstrated that the function of HMGB1 in different cancer types is different, such as the correlation of HMGB1 with CAFs is positive in BRCA‐LumA, MESO and TGCT; but is negative in HNSC‐HPV+, which may indicate that the mechanism of HMGB1 is different in different cancer types.

HMGB1 is quickly released into the circulation in severe mechanical trauma, related conditions and sepsis. 3 , 30 This is related to the destructive and self‐harming features of the innate immune response. In some life‐threatening diseases, HMGB1 levels are remarkably high and associated with acute inflammation, such as stroke and acute myocardial infarction. 3 , 30 In the most severely ill patients, HMGB1 autoantibodies in sepsis models are associated with a good prognosis. 31 In injury‐mediated sterile inflammation, HMGB1 is released as an early mediator to activate the release of TNF‐α and other cytokines. In animals, systemic administration of HMGB1 could be fatal. 32 Many animal studies have shown the beneficial use of neutralizing antibodies or recombinant antagonists to inhibit HMGB1, thrombomodulin box A or the N‐terminal portion on haemorrhagic shock, 33 , 34 ischemia/reperfusion, 35 myocardial 36 and acute lung. 37 In contrast, HMGB1 could also serve as an advanced mediator of sepsis and have beneficial effects in preclinical sepsis studies. 38 , 39

A wide range of immune deconvolution methods were applied to investigate the correlation between HMGB1 expression and the immune infiltration level of CD8+ T‐cells in 33 tumours. The results first suggested the correlation between HMGB1 expression and the estimated infiltration value of cancer‐associated fibroblasts in certain tumours, including the TCGA tumours of BRCA‐LumA, HNSC_HPV‐, MESO and TGCT. The DNA methylation levels were down‐regulated for LUAD, LUSC and THYM (Figure S4). There are positive correlations between HMGB1 expression and the immune infiltration level of CD8+ T‐cells in lung and thymic cancers, such as LUAD, LUSC and THYM (Figure S7). It is worth noting that the current research is based on bioinformatics analysis. Therefore, further functional and clinical verification is necessary.

Interestingly, the mRNA expression of HMGB1 is significantly increased in THYM (Figure 1B), and this increased expression could lead to a better OS for patients with THYM (Figure 2). Different from other cancer types, there is a significantly negative correlation between THYM and cancer‐associated fibroblasts (Figure S8). At the same time, there is a significantly positive correlation between THYM and T‐cell CD8+ (Figure S7). Furthermore, the results from STRING and GEPIA2 analyses shared three members (HMGB2, SRSF1 and SSRP1) for the enrichment analyses of HMGB1‐related partners (Figure 5C, Figure S10). These three members have been reported to be associated with lung cancers or breast cancers. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45

In this study, we unified several publicly available databases to investigate the expression of the HMGB1, explored correlations with prognosis and evaluated potential mechanisms of regulation in tumour patients. We utilized the TCGA, ONCOMINE, cBioPortal, UALCAN, GEPIA and STRING databases to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the structure and function of the HMGB1. Based on the results of the correlation analysis of HMGB1 and survival prognosis using GEPIA2, it can be seen that the overexpression of HMGB1 is significantly associated with poor prognosis of the five tumours (ACC, ESCA, KICH, LUAD and PAAD), while the overexpression of HMGB1 is also significantly associated with better prognosis of KIRC and THYM. These results suggest that the expression of HMGB1 has the potential to serve as a poor prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for cancer patients.

COVID‐19 is a respiratory disease that causes severe symptoms in the lungs. However, one of the differences from other respiratory diseases is that the high fatality rate is initially due to thick, copious mucus in the lungs and then, to the impairment of lung function 46 , 47 . Therefore, the disease of the chest cavity caused by thymic cancer, such as THYM, could greatly promote mucus secretion or make it easier for the mucus to affect the lungs. This finding helps us understand the further impact of thoracic cavity structure and function on COVID‐19, rather than only focusing on lung function. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first discovery of COVID‐19 and THYM through HMGB1.

In summary, the pan‐cancer analysis of HMGB1 showed that the expression of HMGB1 was significantly related to the prognosis, genetic changes, immune cell infiltration and drug sensitivity of different tumours in cancer patients. HMGB1 acts as a tumour promoter in most of the tumours studied and has the potential to be used as a potential marker for prognosis. This helps us understand the role of HMGB1 in tumorigenesis. Most conclusions were drawn from bioinformatics analysis in the current research. More experiments are needed to evaluate further the potential role of HMGB1 in THYM to support the bioinformatic results. Thus, further research should explore how HMGB1 promotes tumorigenesis, such as through the analysis of gene alterations and the related signalling pathways. For cancer treatment, further research should pay attention to the role of HMGB1 in immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shoukai Yu: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal). Lingmei Qian: Investigation (equal). Jun Ma: Conceptualization (supporting); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILBILITY STATEMENT

All the data used in this study are obtained from publicly available databases, the data and results analysed in this study are available on request.

Supporting information

Figure S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank numerous investigators who contributed datasets used in this manuscript and members of the Lemos lab for discussions at Harvard University.

Yu S, Qian L, Ma J. Genetic alterations, RNA expression profiling and DNA methylation of HMGB1 in malignancies. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26:4322‐4332. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17454

Funding information

This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Human Resource Bureau and Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (Pujiang Talent Program grant numbers, No. 19PJC085).

Contributor Information

Shoukai Yu, Email: shoukaiyu@sjtu.edu.cn.

Jun Ma, Email: majun@shtrhospital.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen L, Long X, Xu Q, et al. Elevated serum levels of S100A8/A9 and HMGB1 at hospital admission are correlated with inferior clinical outcomes in COVID‐19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(9):992‐994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen R, Huang Y, Quan J, et al. HMGB1 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for severe COVID‐19. Heliyon. 2020;6(12):e05672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson U, Ottestad W, Tracey KJ. Extracellular HMGB1: a therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID‐19? Mol Med. 2020;26(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Street ME. HMGB1: a possible crucial therapeutic target for COVID‐19? Horm Res Paediatr. 2020;93(2):73‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan JK, Roth J, Oppenheim JJ, et al. Alarmins: awaiting a clinical response. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2711‐2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersson U, Yang H, Harris H. High‐mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) operates as an alarmin outside as well as inside cells. Semin Immunol. 2018;38:40‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goh J, Behringer M. Exercise alarms the immune system: a HMGB1 perspective. Cytokine. 2018;110:222‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang H, Wang L, Chen Y, et al. Outcomes of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection in 107 patients with cancer from Wuhan, China. Cancer. 2020;126(17):4023‐4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID‐19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10241):1907‐1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernandez C, Huebener P, Pradere JP, Antoine DJ, Friedman RA, Schwabe RF. HMGB1 links chronic liver injury to progenitor responses and hepatocarcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(6):2436‐2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tan G, Huang C, Chen J, Zhi F. HMGB1 released from GSDME‐mediated pyroptotic epithelial cells participates in the tumorigenesis of colitis‐associated colorectal cancer through the ERK1/2 pathway. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kellogg C, Equils O. The role of the thymus in COVID‐19 disease severity: implications for antibody treatment and immunization. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(3):638‐643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belarbi Z, Brem FL, Nasri S, Imane S, Noha EO. An uncommon presentation of COVID‐19: concomitant acute pulmonary embolism, spontaneous tension pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema (a case report). Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large‐scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556‐W560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen F, Chandrashekar DS, Varambally S, Creighton CJ. Pan‐cancer molecular subtypes revealed by mass‐spectrometry‐based proteomic characterization of more than 500 human cancers. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Men C, Chai H, Song X, Li Y, Du H, Ren Q. Identification of DNA methylation associated gene signatures in endometrial cancer via integrated analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression systematically. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(6):e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shinawi T, Hill VK, Krex D, et al. DNA methylation profiles of long‐ and short‐term glioblastoma survivors. Epigenetics. 2013;8(2):149‐156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401‐404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. STRING v11: protein‐protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome‐wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607‐d613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein‐protein networks, and functional characterization of user‐uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605‐D612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tikoo K, Patel G, Kumar S, et al. Tissue specific up regulation of ACE2 in rabbit model of atherosclerosis by atorvastatin: role of epigenetic histone modifications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93(3):343‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Towler P, Staker B, Prasad SG, et al. ACE2 X‐ray structures reveal a large hinge‐bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17996‐18007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fridman WH, Galon J, Dieu‐Nosjean MC, et al. Immune infiltration in human cancer: prognostic significance and disease control. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;344:1‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steven A, Seliger B. The role of immune escape and immune cell infiltration in breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel). 2018;13(1):16‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X, Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer‐associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(2):99‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kwa MQ, Herum KM, Brakebusch C. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts: how do they contribute to metastasis? Clin Exp Metastasis. 2019;36(2):71‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1108‐1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peltz ED, Moore EE, Eckels PC, et al. HMGB1 is markedly elevated within 6 hours of mechanical trauma in humans. Shock. 2009;32(1):17‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barnay‐Verdier S, Fattoum L, Borde C, Kaveri S, Gibot S, Maréchal V. Emergence of autoantibodies to HMGB1 is associated with survival in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(6):957‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, et al. HMG‐1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285(5425):248‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim JY, Park JS, Strassheim D, et al. HMGB1 contributes to the development of acute lung injury after hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288(5):L958‐L965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abeyama K, Stern DM, Ito Y, et al. The N‐terminal domain of thrombomodulin sequesters high‐mobility group‐B1 protein, a novel antiinflammatory mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1267‐1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia‐reperfusion. J Exp Med. 2005;201(7):1135‐1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, et al. High‐mobility group box‐1 in ischemia‐reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117(25):3216‐3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ogawa EN, Ishizaka A, Tasaka S, et al. Contribution of high‐mobility group box‐1 to the development of ventilator‐induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(4):400‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, et al. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high‐mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(1):296‐301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andersson U, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:139‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gao KL, Li M, Zhang KP. Imperatorin inhibits the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells by regulating HMGB2. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2021;35(1):227‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fu D, Li J, Wei J, et al. HMGB2 is associated with malignancy and regulates Warburg effect by targeting LDHB and FBP1 in breast cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2018;16(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang W, Li L, Zhao L. LINC00184 plays an oncogenic role in non‐small cell lung cancer via regulation of the miR‐524‐5p/HMGB2 axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(21):9927‐9938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. de Miguel FJ, Sharma RD, Pajares MJ, Montuenga LM, Rubio A, Pio R. Identification of alternative splicing events regulated by the oncogenic factor SRSF1 in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(4):1105‐1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Anczuków O, Akerman M, Cléry A, et al. SRSF1‐regulated alternative splicing in breast cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60(1):105‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dermawan J, Gurova K, Pink J, Dowlati A, De S. Quinacrine overcomes resistance to erlotinib by inhibiting FACT, NF‐κB, and cell‐cycle progression in non–small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(9):2203‐2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kumar SS, Binu A, Devan AR, Nath LR. Mucus targeting as a plausible approach to improve lung function in COVID‐19 patients. Med Hypotheses. 2021;156:110680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Manckoundia P, Franon E. Is persistent thick copious mucus a Long‐term symptom of COVID‐19? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7(12):002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1