Abstract

Background

Vaccines are effective in preventing severe COVID‐19, a disease for which few treatments are available and which can lead to disability or death. Widespread vaccination against COVID‐19 may help protect those not yet able to get vaccinated. In addition, new and vaccine‐resistant mutations of SARS‐CoV‐2 may be less likely to develop if the spread of COVID‐19 is limited. Different vaccines are now widely available in many settings. However, vaccine hesitancy is a serious threat to the goal of nationwide vaccination in many countries and poses a substantial threat to population health. This scoping review maps interventions aimed at increasing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake and decreasing COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy.

Objectives

To scope the existing research landscape on interventions to enhance the willingness of different populations to be vaccinated against COVID‐19, increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake, or decrease COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy, and to map the evidence according to addressed populations and intervention categories.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register, Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded and Emerging Sources Citation Index), WHO COVID‐19 Global literature on coronavirus disease, PsycINFO, and CINAHL to 11 October 2021.

Selection criteria

We included studies that assess the impact of interventions implemented to enhance the willingness of different populations to be vaccinated against COVID‐19, increase vaccine uptake, or decrease COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy. We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised studies of intervention (NRSIs), observational studies and case studies with more than 100 participants. Furthermore, we included systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. We did not limit the scope of the review to a specific population or to specific outcomes assessed. We excluded interventions addressing hesitancy towards vaccines for diseases other than COVID‐19.

Data collection and analysis

Data were analysed according to a protocol uploaded to the Open Science Framework. We used an interactive scoping map to visualise the results of our scoping review. We mapped the identified interventions according to pre‐specified intervention categories, that were adapted to better fit the evidence. The intervention categories were: communication interventions, policy interventions, educational interventions, incentives (both financial and non‐financial), interventions to improve access, and multidimensional interventions. The study outcomes were also included in the mapping. Furthermore, we mapped the country in which the study was conducted, the addressed population, and whether the design was randomised‐controlled or not.

Main results

We included 96 studies in the scoping review, 35 of which are ongoing and 61 studies with published results. We did not identify any relevant systematic reviews. For an overview, please see the interactive scoping map (https://tinyurl.com/2p9jmx24).

Studies with published results

Of the 61 studies with published results, 46 studies were RCTs and 15 NRSIs. The interventions investigated in the studies were heterogeneous with most studies testing communication strategies to enhance COVID‐19 vaccine uptake. Most studies assessed the willingness to get vaccinated as an outcome. The majority of studies were conducted in English‐speaking high‐income countries. Moreover, most studies investigated digital interventions in an online setting. Populations that were addressed were diverse. For example, studies targeted healthcare workers, ethnic minorities in the USA, students, soldiers, at‐risk patients, or the general population.

Ongoing studies

Of the 35 ongoing studies, 29 studies are RCTs and six NRSIs. Educational and communication interventions were the most used types of interventions. The majority of ongoing studies plan to assess vaccine uptake as an outcome. Again, the majority of studies are being conducted in English‐speaking high‐income countries. In contrast to the studies with published results, most ongoing studies will not be conducted online. Addressed populations range from minority populations in the USA to healthcare workers or students. Eleven ongoing studies have estimated completion dates in 2022.

Authors' conclusions

We were able to identify and map a variety of heterogeneous interventions for increasing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake or decreasing vaccine hesitancy. Our results demonstrate that this is an active field of research with 61 published studies and 35 studies still ongoing. This review gives a comprehensive overview of interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake and can be the foundation for subsequent systematic reviews on the effectiveness of interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake.

A research gap was shown for studies conducted in low and middle‐income countries and studies investigating policy interventions and improved access, as well as for interventions addressing children and adolescents. As COVID‐19 vaccines become more widely available, these populations and interventions should not be neglected in research.

Plain language summary

Interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake

Background

Vaccines are effective in preventing death or severe illness from COVID‐19, a disease for which few treatments are available. Widespread vaccination against COVID‐19 may help protect those not yet able to get vaccinated. However, many people do not want to get vaccinated against COVID‐19. This can put them at increased risk of severe disease and death.

What was our aim?

We wanted to find out which interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake have been or are currently evaluated.

Methods

We searched medical databases and trial registries until the 11 of October 2021. We included all studies investigating interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake. We excluded studies looking at other vaccines, for example, measles. We included all forms of studies as long as they had more than 100 participants.

Once we found the studies, we categorised the interventions into the following groups: communication interventions, policy interventions, interventions to improve access, educational interventions, incentives, and multidimensional interventions. We summarised the results in an interactive scoping map. Furthermore, we mapped the study outcomes, the country in which the study was conducted, the study population, and the study design.

Results

We included 96 studies in evidence mapping, 35 of which are ongoing and 61 studies with published results. The interventions tested in these studies are very diverse. Many studies used communication strategies to convince people to get vaccinated against COVID‐19. Interventions that included information on vaccination or a mixture of different strategies were also often used.

A majority of studies were conducted in English‐speaking countries of the global north, for example, the USA. Moreover, most studies investigated digital interventions in an online setting. The populations addressed varied across the studies. For example, studies addressed healthcare workers, ethnic minorities in the USA, students, soldiers, villagers, at‐risk patients, or the general population.

For an overview, please see the interactive scoping map (https://tinyurl.com/2p9jmx24).

Conclusion

We identified a large number of studies that investigate how COVID‐19 vaccine uptake might be increased. However, more studies are needed focusing on lower‐middle‐income countries and on children. Future research should compare the effectiveness of different interventions to improve COVID‐19 vaccine uptake.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Intervention Group | Intervention | Outcomes | |||||||

| Vaccine hesitancy | Vaccine uptake | Willingness to get vaccinated | Agreement with COVID‐19 Policies | ||||||

| Proportion of participants with COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy | Decrease in vaccine hesitancy | Reactance1 | Number of participants who got vaccinated | Number of participants indicating the intention to get vaccinated |

Vaccine trust | Further interest in vaccine information | Agreement with COVID‐19 vaccine passport | ||

| Communication strategies | Behavioural messaging | NCT04871776; NCT04895683 | |||||||

| Text messages | NCT04801524 | ||||||||

| Healthcare providers' communication about the COVID‐19 vaccine | NCT04706403 | ||||||||

| Framing | Borah 2021*; Chen 2021*; *Fox 2021*; Galasso 2021*; Gong 2021*; Huang 2021*; Palm 2021*; Strickland 2021* | ||||||||

| Information messaging | Argote 2021*; Bokemper 2021*; OCEAN*; Schwarzinger 2021*; Thorpe 2021*; NCT04813770 | ||||||||

| Framing videos | Yuan 2021* | ||||||||

| Expert claims | Robertson 2021b* | ||||||||

| Messaging about benefits | Ashworth 2021 | ||||||||

| Gain vs. Loss framing | Reichardt 2021* | Hong 2021* | Peng 2021*; Ye 2021* | ||||||

| HCW vaccine ambassadors | NCT04981392 | NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID) | |||||||

| Affect messaging | Capasso 2021* | ||||||||

| Public service messages | Jin 2021* | ||||||||

| Norm Framing | Ryoo 2021* | Sinclair 2021* | |||||||

| Framing and source of information | Pink 2021*; Thunström 2021* | ||||||||

| Risk framing | Sudharsanan 2021* | ||||||||

| Visual Illustrations with vaccine information | Ugwuoke 2021* | ||||||||

| Persuasive messages | Kachurka 2021* | ||||||||

| Personalised communication | Stein 2021*; Santos 2021*; NCT04805931 (VEText); NCT04834726; NCT04924803; NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); ISRCTN15317247; NCT04952376; NCT04963790; NCT05027464 (CoVAcS) | Keppeler 2021* | |||||||

| Conversational agent | NCT04884750 | ||||||||

| Community influencer groups | PACTR202102846261362 | ||||||||

| Policy interventions | Mandatory vaccine policy | Sprengholz 2021* | |||||||

| Multidimensional interventions | High touch multi‐pronged behavioural intervention | NCT04732819 | |||||||

| Text messages for education outreach2 | NCT04800965 | ||||||||

| Nudging3 | NCT04867174 | NCT05037201 | Sotis 2021* | ||||||

| Culturally sensitive interventions | Marquez 2021*; NCT04542395; NCT04779138 | ||||||||

| Drawing attention to prosocial concerns | Jung 2021* | ||||||||

| Multidimensional information intervention | Kerr 2021* | ||||||||

| Vaccine education promotion management plan | NCT04761692 | ||||||||

| Phone‐based intervention for elders4 | NCT04870593 | ||||||||

| Incentives and nudging | Campos‐Mercade 2021* | ||||||||

| Multidimensional community intervention5 | NCT05022472 (2VIDA!) | ||||||||

| Multifaceted information intervention for HCW6 | Takamatsu 2021* | ||||||||

| Incentives and prosocial communication | Sprengholz 2021c* | ||||||||

| Multidimensional intervention for HCW7 | Howarth 2021* | ||||||||

| Education about herd immunity OR empathy condition | Pfattheicher 2021* | ||||||||

| Reminders and nudging | Senderey 2021* | ||||||||

| Incentives and easy access | Klüver 2021* | ||||||||

| Educational interventions | Entertainment‐education video | DRKS00023650 | |||||||

| Educational video | Witus 2021*; NCT04876885; NCT04960228; NCT04979416 | ||||||||

| Social marketing intervention | NCT04801030 | ||||||||

| Counselling | NCT04604743 | ||||||||

| Educational webinar | Kelkar 2021* | ||||||||

| Chatbot | Kobayashi 2021* | ||||||||

| Workshop | Talmy 2021* | ||||||||

| Rapid education | NCT04939506 | ||||||||

| Cultural‐appropriate Education | NCT04964154 (BRAVE) | ||||||||

| COVID‐19 vaccine information | Merkley 2021* | ||||||||

| Individualised information | Tran 2021* | ||||||||

| Incentives | Financial incentives8 | Kreps 2021*; Robertson 2021a*; Serra‐Garcia 2021*; Yu 2021*; Yu 2021b* | Duch 2021* | ||||||

| Lottery | Barber 2021*; Brehm 2021*; Sehgal 2021*; Thirumurthy 2021*; Walkey 2021*; NCT04951310 | ||||||||

*Studies have published results

1 Reactance was defined as "how frustrated, annoyed and disturbed participants felt about the vaccination situation" by the study authors (Sprengholz 2021).

2 Providing information as well as convincing people to get vaccinated via video, text messages and providing a link to schedule an appointment.

3 Nudges are behavioural interventions that influence people's choices from the perspective of policy‐makers or society, without restricting freedom of choice and changing the incentive system.

4 Calling elders to inform them of the vaccine and encouraging them to create buddy systems and gossip about the vaccine.

5Education and promotion (COVID‐19 awareness, education, health promotion), outreach and easy access (linkage to medical and supportive services, pop‐up vaccination sites)

6Education and information (lectures, educational sessions about the vaccine, informational leaflets), encouragement and risk reduction (vaccination‐encouraging announcements, allergy testing at risk of allergic reactions to the vaccine)

7Vaccine information (e.g. posters targeting vaccine misinformation, vaccine information packs) and vaccine role models (“Vaccine champions”, posters showing already vaccinated staff members

8Hypothetical financial fee or out‐of‐pocket cost for getting vaccinated

For an interactive version of this map, please see https://egmopenaccess.3ieimpact.org/evidence‐maps/interventions‐increase‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐uptake?

Background

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the current COVID‐19 outbreak a pandemic. The approval of the first COVID‐19 vaccine in December 2020 has been long‐awaited to help mitigate the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Currently, 10 vaccines are recommended by the WHO (WHO 2021a), and many more are in development (WHO 2021b). Countries with limited vaccine access might not be in the position to create and implement vaccine campaigns raising awareness and willingness to be vaccinated.

Widespread COVID‐19 vaccination is crucial to protecting population health ‐ vaccination has been shown to be highly effective in preventing severe COVID‐19 illness and death from the disease (Public Health Ontario 2021). In nursing homes and hospitals, in particular, vaccines are supposed to protect high‐risk populations from severe illness, including healthcare workers. Furthermore, high vaccine uptake may indirectly protect people with a weak response to the vaccine, such as the elderly or immunosuppressed patients, from severe COVID‐19 disease. High levels of vaccination against COVID‐19 ought also to help ensure the smooth operation of health systems, as unvaccinated people are hospitalised for COVID‐19 more often than vaccinated people (Lopez 2021). In addition, new and vaccine‐resistant mutations of SARS‐CoV‐2 are more likely to develop if the spread of COVID‐19 is not limited. However, vaccine hesitancy is a serious threat to the goal of nationwide vaccination (Thunstrom 2020).

Vaccine hesitancy: reasons and prevalence

A recent systematic review of global COVID‐19 vaccine acceptance rates shows that populations widely differ in their acceptance of the COVID‐19 vaccines (Sallam 2021). For example, nearly the whole population of Ecuador, Malaysia and Indonesia are willing to get vaccinated against COVID‐19, while the projected acceptance rate among the French population was only 58.9%. In the USA, where COVID‐19 vaccines are widely available for the adult population, about 30% of the population remain unvaccinated (KFF 2022). Likewise, in countries where the vaccine is not yet widely available, a low willingness to be vaccinated against COVID‐19 is predicted by experts (Afolabi 2021).

In addition to a broad distrust in and doubts about vaccines in general, there seem to be specific reasons for hesitancy towards COVID‐19 vaccines. Studies show that people distrust the COVID‐19 vaccines as they believe the vaccines were manufactured too quickly (Nguyen 2021), or are sceptical of the new mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid) technology used in some vaccines (Dror 2021). A number of conspiracy theories have been spread about the COVID‐19 vaccine that are likely influencing vaccination uptake (Romer 2020; Ullah 2021). For example, the mistaken belief that COVID‐19 is either a non‐existent or a harmless disease makes people unwilling to get vaccinated (Troiano 2021). Furthermore, people also express the fear of adverse vaccine reactions and long‐term harms of the COVID‐19 vaccine as a reason not to get vaccinated (Abu 2021).

Next to individual beliefs about COVID‐19, other characteristics are also associated with vaccine hesitancy. A survey conducted in the UK shows that factors such as negative experiences with the healthcare system and a general distrust of authorities are associated with COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy (Freeman 2020). For example, people voting for anti‐establishment parties in Austria are also more likely to be vaccine‐hesitant (Schernhammer 2021). Likewise, political partisanship is predictive for COVID‐19 vaccine uptake in the USA (Hamel 2021), where Democrats are more likely to get vaccinated than Republicans. Distrust in authorities is also high among marginalised populations that have been affected disproportionally by the pandemic (Jaiswal 2020). Additionally, as reported by several studies, being female is linked with a higher hesitancy towards COVID‐19 vaccination (Bono 2021; Edwards 2020). Other demographic variables, such as age, education and ethnicity have also been linked to vaccine hesitancy (Nguyen 2021a; Reno 2021).

Why it is important to do this review

While attitudes towards the COVID‐19 vaccine have been thoroughly researched (Ahmed 2021; Akarsu 2021; Al‐Jayyousi 2021), it is still unclear whether there are effective interventions available to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake. The WHO identifies five factors that are central to the willingness to get vaccinated (Brewer 2017): social processes and people's emotions and thoughts impact their motivation to get vaccinated. Practical issues, such as costs and access, then influence if someone will get vaccinated or not. Each factor can be an important starting point for an intervention to increase vaccine uptake. A plethora of interventions have been proposed to increase the willingness to get vaccinated or to decrease vaccine hesitancy for other diseases. For example, financial incentives have been shown to increase vaccine uptake for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations (Mantzari 2015), role models can increase vaccine uptake for hepatitis B (Vet 2010), and patient outreach has been utilised to increase pneumococcal vaccination (Winston 2007) and immunisation rates overall (Jacoboson Vann 2018). Moreover, Cochrane Reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of different interventions, such as face‐to‐face communication, incentives or mandatory vaccinations to increase vaccine uptake for diverse populations (Abdullahi 2020; Jacoboson Vann 2018; Kaufman 2018; Oyo‐Ita 2016). Interventions can be categorised as communication‐based interventions, motivational interventions, or as structural interventions based on health policies and increased accessibility (Dubé 2015; Jarrett 2015; Odone 2015; Wigham 2014).

Rationale for conducting a scoping review

Research into measures to address COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy is emerging rapidly. The methodology of scoping reviews can be used to identify and map available evidence (Anderson 2008; Munn 2018). Hence, a scoping review will allow us to obtain a rapid, comprehensive overview of possible interventions and populations targeted.

No systematic or scoping review has yet systematically identified and analysed these interventions in the context of COVID‐19. COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy poses a substantial threat to population health and therefore, the evidence for interventions aimed at increasing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake needs to be investigated. This scoping review will help to define the scope of a subsequent systematic review.

Objectives

To scope the existing research landscape on interventions to enhance the willingness of different populations to be vaccinated against COVID‐19, increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake, or decrease COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy, and to map the evidence according to addressed populations and intervention categories.

Methods

Scoping review methodology

We followed the interim guidance on scoping reviews by Cochrane and the guidance of the Joanna Briggs Institute for conducting this review (Peters 2020). Furthermore, we consulted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) checklist (Tricco 2018) for the reporting of the results. Please see Appendix 1 for the completed checklist for this scoping review. The methods for this scoping review were published beforehand (Andreas 2021).

Inclusion criteria

Study design

We included studies that assess the impact of interventions implemented to enhance the willingness of different populations to be vaccinated against COVID‐19. As we wanted to get a broad overview of interventions being investigated and as no past reviews exist on this topic, we decided to include studies with the following designs: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised trials, observational studies (controlled pre‐post studies, interrupted time‐series studies, case‐control, cohort, and cross‐sectional studies), and single‐arm studies (uncontrolled pre‐post studies) with more than 100 participants. Furthermore, we included systematic reviews. For psychological experiments with hypothetical scenarios being tested, we decided to only include those studies that investigate scenarios that can be manipulated in a real‐world setting, so the findings can be translated into interventions. For example communication about vaccines can be manipulated, but vaccine efficacy cannot be manipulated.

Addressed population

In order to get a broad overview of all interventions and addressed populations, we did not limit the scope of our review by focusing on specific population groups. We also included studies testing interventions directed at healthcare providers, community leaders, or other role models to help these groups to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake more widely.

Interventions

We only included studies on interventions specifically addressing willingness to get vaccinated against COVID‐19, or intended to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake, or decrease COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy. We excluded interventions addressing hesitancy towards vaccines for diseases other than COVID‐19.

Outcomes

We did not limit the scope of our review by focusing on specific outcomes in order to get a broad overview of the outcome measures assessed in studies.

An overview of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

1. Inclusion criteria .

| Criteria | Details |

| Study designs |

|

| Population | Any population, no restrictions |

| Setting | No restrictions |

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | No restrictions |

RCTs: randomised controlled trials

2. Exclusion criteria .

| Criteria | Details |

| Study designs |

|

| Population | No exclusion criteria |

| Setting | No exclusion criteria |

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | No exclusion criteria |

HPV: human papillomavirus

Identification of relevant studies

For the identification of evidence syntheses and completed and ongoing studies systematic searches were performed by our Information Specialist (IM). They were peer‐reviewed by a second Information Specialist as part of the editorial process for this manuscript.

We searched the following electronic databases for primary studies from 1 January 2020 to 11 October 2021:

-

Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (CCSR) (www.covid-19.cochrane.org)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

PubMed;

Embase.com;

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/trialsearch);

medRxiv (www.medrxiv.org).

-

Web of Science Core Collection

Science Citation Index Expanded (1945 to present);

Emerging Sources Citation Index (2015 to present).

WHO COVID‐19 Global literature on coronavirus disease (search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/)

PsycINFO (Ovid 1806 to present);

CINAHL (EBSCO 1982 to present).

We searched the following electronic databases and websites for evidence syntheses from 1 January 2020 to 10 June 2021:

Evidence Aid Coronavirus (Covid‐19) (evidenceaid.org/evidence/coronavirus-covid-19/);

Usher Network for COVID‐19 Evidence Reviews (www.ed.ac.uk/usher/uncover/register-of-reviews);

Epistemonikos COVID‐19 L*OVE Platform (app.iloveevidence.com/loves);

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1 January 2020 to 10 June 2021) with a filter for systematic reviews (Wong 2006).

We searched for primary studies on 10 June 2021 and updated the search on 11 October 2021. We did not update the search for evidence syntheses, because we did not identify any relevant hits in the search of June. We began the search in January 2020 as this was when COVID‐19 was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the WHO.

Please see Appendix 2 for the search strategies for evidence syntheses and Appendix 3 for the search strategies for primary literature. The search was conducted in English, however, we did not exclude studies if they had not been published in English.

Study selection

Two review authors (MA, EB) independently screened titles and abstracts of identified records. We used the web‐based application Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/welcome) for title and abstract screening. Discrepancies between authors were discussed and in case the conflict persisted a third review author (CI) resolved conflicts. To ensure that all review authors screen consistently, we developed a guidance document to standardise the screening process. We then retrieved full‐text articles of all potentially included studies and assessed the eligibility of the remaining records against our pre‐defined eligibility criteria. This was also done independently and in duplicate. We documented reasons for the exclusion of full texts.

Extraction and presentation of data

Two authors (MA, EB) independently extracted the following information into a piloted data extraction sheet. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Study characteristics

-

Study design

Country of origin (where the study was conducted)

Characteristics of the population addressed by the intervention (age; gender; ethnicity)

Intervention details (timeframe; intervention category; intervention method)

Comparison details (if applicable)

Time of follow‐up (if applicable)

Outcomes (outcome measures; time points of outcome assessment)

Financial support and sponsoring

Disclosure of conflicts of interest (COIs)

If any of the above data were not available, we contacted the study authors for further information.

Summary and reporting of results

We presented the results in a tabular form using software by 3ie EGM (https://egmopenaccess.3ieimpact.org/evidence‐maps/interventions‐increase‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐uptake?) to create the evidence map. We mapped data according to the categories of interventions identified and the outcomes assessed. The classification of interventions was first based on a review by the SAGE working group for vaccine hesitancy (Larson 2014), and other systematic reviews addressing vaccine uptake (Dubé 2015; Jarrett 2015; Odone 2015; Wigham 2014; Winston 2007). We have added policy interventions (e.g. mandatory vaccine uptake) as we think these are especially relevant in the context of nationwide COVID‐19 vaccine rollouts. We adapted the categories originally published in our protocol to better fit the evidence we found. Thus, the final intervention categories were: education, policy interventions, communication interventions, incentives, interventions to improve access, and multidimensional interventions. Please see Table 4 for an overview and description of each category. Please see the Differences between protocol and review section for a justification of the changes made. Additionally, we mapped the region and country in which studies were conducted, the addressed population, as well as the study design.

3. Categorisation of interventions used in this review .

| Cetegory | Description |

|

Education |

Interventions aimed at educating or informing participants about COVID‐19, COVID‐19 vaccines, benefits of vaccine uptake and other aspects of the pandemic or vaccination. |

| Policy interventions | Interventions that can only be implemented across a whole jurisdiction by policymakers, such as mandatory vaccine policies. |

| Communication strategies | Interventions aiming to persuade people to get vaccinated. This can be in‐person communication but also communication used in different forms of media such as videos or written information. |

| Incentives |

|

| Interventions to improve access | Multidimensional interventions are interventions using more than one strategy. For example, educational interventions and communication strategies can be used together. |

Results

Results of the search

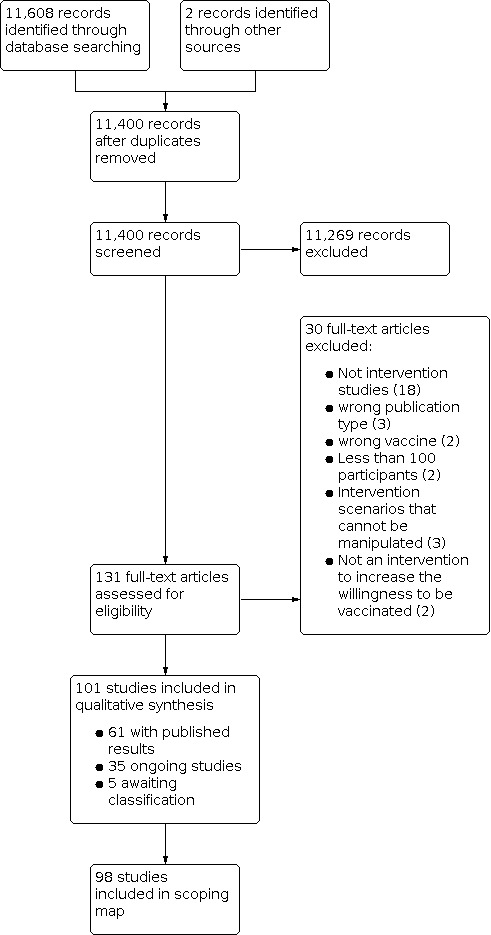

We identified 11,608 potentially relevant references. After the removal of duplicates (208), we screened 11,400 references based on their titles and abstracts, excluding 11,269 references because they did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria. We screened the full texts of the remaining 131 references, or, if these were not available, abstract publications or trial registry entries. We excluded 30 studies after the full‐text screening. We identified 101 eligible studies, five of which were assessed as awaiting classification as it was unclear from trial registries if they really are intervention studies. In the end, we included 96 studies in the interactive scoping map, 61 studies with published results, and 35 of which are ongoing. The process and results of study selection are documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

For an overview of all studies please see the Table 1 and the interactive scoping map.

Studies with published results

We included 61 studies with published results in the interactive scoping map. Of the studies with published results, 46 studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Argote 2021; Ashworth 2021; Bokemper 2021; Borah 2021; Campos‐Mercade 2021; Capasso 2021; Chen 2021; Duch 2021; Fox 2021; Galasso 2021; Gong 2021; Hong 2021; Huang 2021; OCEAN; Jin 2021; Jung 2021; Kachurka 2021; Kerr 2021; Keppeler 2021; Klüver 2021; Kreps 2021; Merkley 2021; Palm 2021; Peng 2021; Pfattheicher 2021; Pink 2021; Reichardt 2021; Robertson 2021a; Robertson 2021b; Santos 2021; Schwarzinger 2021; Sinclair 2021; Strickland 2021; Senderey 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Sotis 2021; Sprengholz 2021; Sprengholz 2021c; Sudharsanan 2021; Thorpe 2021; Thunström 2021; Ye 2021; Yu 2021; Yu 2021b; Yuan 2021; Witus 2021). Fifteen studies were non‐randomised intervention studies. Of these, two studies were uncontrolled post‐intervention studies (Kobayashi 2021; Ryoo 2021), and nine were uncontrolled retrospective cohort studies (Barber 2021; Brehm 2021; Kelkar 2021; Marquez 2021; Sehgal 2021; Stein 2021; Talmy 2021; Thirumurthy 2021; Walkey 2021). One study was a controlled cohort study (Ugwuoke 2021). Three studies had a pre‐post interventional design (Howarth 2021; Takamatsu 2021; Tran 2021).

A majority (29 of 61) of studies were conducted in the USA. One study was conducted in the USA and Germany, and one in the USA and UK. Six studies were conducted in China. Six studies were conducted in the UK, two in France, two in Japan, one in Sweden, one in Poland, one in Italy, one in Canada, four in Germany, and two in Israel. Furthermore, one study was conducted in Pakistan and one in Nigeria. One multinational study was carried out in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. One study was carried out in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. In summary, the majority of studies were conducted in high‐income countries. For an overview, please see our interactive scoping map, in which you can select regions and countries.

Forty‐one studies were conducted in an online setting, while 20 studies were conducted in person. Of the latter, one study was conducted in a university, five studies in a hospital setting, one study with a healthcare provider, and one study in a health system. Furthermore, one study was set in a military unit, one in Sweden, and one study in a Latinx community. Four studies were conducted in Ohio, USA and one study in 24 US states. One study was conducted via telephone in Germany, and one study via letters in a German municipality. One study was conducted in a camp for internally displaced persons. One study did not report a specific setting. In summary, a majority of published studies were conducted in an online setting, mostly testing hypothetical scenarios. We define online settings as interventions solely conducted online, for example, webinars or online surveys. For more detailed information, please see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Of the included studies, 11 were published on preprint servers (Argote 2021; Barber 2021; Duch 2021; Keppeler 2021; Kobayashi 2021; Marquez 2021; Senderey 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Strickland 2021; Thirumurthy 2021; Witus 2021).

Ongoing studies

We identified 35 ongoing studies. Of the ongoing studies, 29 studies are RCTs (DRKS00023650; ISRCTN15317247; NCT04604743; NCT04706403; NCT04732819; NCT04761692; NCT04800965; NCT04801524; NCT04805931 (VEText); NCT04813770; NCT04834726; NCT04867174; NCT04870593; NCT04871776; NCT04884750; NCT04895683; NCT04924803; NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID); NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); NCT04951310; NCT04952376; NCT04960228; NCT04963790; NCT04964154 (BRAVE); NCT04979416; NCT04981392; NCT05022472 (2VIDA!); NCT05027464 (CoVAcS); NCT05037201). Six studies have a non‐randomised intervention designs. Of those, one study will investigate the intervention in a prospective, two‐arm observational study (PACTR202102846261362). Three studies will utilise a non‐randomised trial design (NCT04876885; NCT04801030; NCT04939506). Two studies will use a pretest‐posttest design without a control group (NCT04542395; NCT04779138).

A majority (26 of 35) of ongoing studies are planned in the USA. One study will be conducted in the USA and China. Three studies will be conducted in the UK, three in Canada, one in Uganda, and one in India. In summary, a majority of ongoing studies are planned to be conducted in English‐speaking, high‐income countries.

Five of the ongoing studies will be conducted in an online setting, one study will be conducted via text messages and three via phone calls, while 11 studies are planned in person. Of the latter, two studies will be conducted in a hospital setting, two studies in a health centre, two studies within a healthcare provider, one in a primary care practice, one study in a skilled nursing facility, two in veteran health care, and one study in a rural clinic. Furthermore, two studies will be set in a church setting, one study in London, one in villages in Uganda, two in a university, one in a managed care setting, and two in public housing. One study will be conducted in southern California, one study will be conducted in Philadelphia, and one study will address vulnerable communities in Louisiana. Four studies did not report a specific setting. In summary, a majority of ongoing studies will address populations in person, most of them in a healthcare setting.

Eleven ongoing studies have estimated completion dates in 2022 (NCT04542395; NCT04964154 (BRAVE); NCT04800965; NCT04801524; NCT04867174; NCT04871776; NCT04895683; NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID); NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); NCT04952376; NCT04963790). For the estimated completion dates of all ongoing studies, please see the characteristics of included studies table for each study.

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies for the following reasons.

Three studies were excluded because they were an ineligible publication type; one was an opinion piece (Hofer 2021), one was a letter to the editor (Sprengholz 2021b), and the other one was a correction (Loomba 2021). Furthermore, one study was excluded because it investigated interventions for influenza vaccine uptake (Yousuf 2021), and one because it investigated measles, mumps and rubella uptake (Kirkpatrick 2021). We excluded two uncontrolled studies with less than 100 participants (Ali 2021; Gakuba 2021). Batteux 2021, Davis 2021 and Wagner 2021 were excluded as the studies investigate scenarios that cannot be manipulated. Loomba 2021a and Thaker 2021 measure the effect of misinformation on vaccine intent and thus are not relevant to the research objective. The other 18 studies were excluded because they did not investigate interventions (American Society of Safety Professionals 2021; Bell 2021; ChiCTR2100043018; Community Practitioner 2021; Crawshaw 2021; Crawshaw 2021b; Gehrau 2021; Guelmami 2021; Kaplan 2021; Knight 2021; Kumar 2021; Lim 2020; NCT04694651; Rahmandad 2021; Salali 2021; Shmueli 2021; Vasquez 2021; Yuen 2021).

Studies awaiting assessment

We classified five studies as awaiting assessment because from the trial registrations and publications of these studies it is not clear whether these studies will test interventions to enhance COVID‐19 vaccine uptake (INFORMED; NCT04460703; NCT04731870; Larson 2020; Supraneni 2021).

Studies included in the scoping map

Please see our interactive scoping map (https://egmopenaccess.3ieimpact.org/evidence‐maps/interventions‐increase‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐uptake?) and the Table 1 for an overview of the interventions and outcomes used in studies as well as study location, population, and design. Please note that studies with published results as well as ongoing studies were included in the scoping map.

Studies with published results

Participants

The interventions investigated in the studies addressed a wide variety of different participants. Howarth 2021, Santos 2021, Takamatsu 2021, and Yu 2021b addressed healthcare workers. Kelkar 2021 and Stein 2021 included cancer patients. Patients in France were addressed in Tran 2021. Marquez 2021 included Latinx community members in San Francisco. Israeli soldiers participated in Talmy 2021, and American veterans and the general population in Thorpe 2021. Adult US citizens participated in Ashworth 2021, Barber 2021, Bokemper 2021, Borah 2021, Brehm 2021, Duch 2021, Fox 2021, Huang 2021, Jung 2021, Kreps 2021, Palm 2021, Pink 2021, Robertson 2021a, Robertson 2021b, Ryoo 2021, Sehgal 2021, Serra‐Garcia 2021, Sotis 2021, Strickland 2021, Thirumurthy 2021, Thunström 2021, Witus 2021, Walkey 2021, and Yuan 2021. Adult US and UK citizens participated in Sudharsanan 2021. Merkley 2021 included Canadian residents. Chen 2021, Gong 2021, and Peng 2021 included Chinese citizens and Yu 2021 Hong Kong citizens. Kerr 2021, Sinclair 2021, Pfattheicher 2021, and OCEAN included UK citizens. US citizens and German citizens participated in Sprengholz 2021 and German adults only in Keppeler 2021, Klüver 2021, Reichardt 2021, and Sprengholz 2021c. Japanese residents participated in Kobayashi 2021, Pakistani residents in Jin 2021, Polish residents in Kachurka 2021 and Swedish residents in Campos‐Mercade 2021. Israeli citizens were addressed by Senderey 2021. Internally displaced persons in Nigeria were addressed by Ugwuoke 2021. Argote 2021 included adults in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru and Galasso 2021 included adults in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. French citizens participated in Schwarzinger 2021 and Italian citizens in Capasso 2021. Young adults participated in Hong 2021 and Ye 2021.

All studies report a sample size of more than 100 participants. In summary, a majority of interventions were targeted towards US adults. For more detailed information on sample size, please see the characteristics of included studies tables. Population groups can also be selected in the interactive evidence map.

Interventions

Interventions were grouped as educational interventions, incentives, policies, communication strategies, increased access and multidimensional interventions. In summary, a majority of published studies tested communication strategies to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake. For more detailed information on the interventions, please see the evidence map as well as the characteristics of included studies table and Table 1.

Communication interventions

Thirty‐four studies tested communication strategies to increase the willingness to vaccinate against COVID‐19 (Argote 2021; Ashworth 2021; Bokemper 2021; Borah 2021; Capasso 2021; Chen 2021; Fox 2021; Galasso 2021; Gong 2021; Hong 2021; Huang 2021; Jin 2021; Kachurka 2021; Keppeler 2021; Merkley 2021; OCEAN; Palm 2021; Peng 2021; Pink 2021; Reichardt 2021; Robertson 2021b; Ryoo 2021; Santos 2021; Stein 2021; Sudharsanan 2021; Schwarzinger 2021; Strickland 2021; Sinclair 2021; Sotis 2021; Thunström 2021; Ugwuoke 2021; Witus 2021; Ye 2021; Yuan 2021), with most studies using framing as a method. Framing is the selection or highlighting of certain aspects of an issue to bring these to the forefront in communication and encourage particular interpretations (Entman 1993). For example, some studies compared gain and loss frames (Hong 2021; Peng 2021; Reichardt 2021; Ye 2021). Text messages, E‐mails, letters, webpages, posters, and face‐to‐face communication were used as media to transport messages about COVID‐19.

Incentives

Eleven studies investigated financial incentives to enhance COVID‐19 vaccine uptake (Barber 2021; Brehm 2021; Duch 2021; Kreps 2021; Robertson 2021a; Sehgal 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Thirumurthy 2021; Walkey 2021; Yu 2021; Yu 2021b). Specifically, a majority of studies investigated vaccine lotteries, where it is possible to win a cash price for getting vaccinated. Other studies researched the effectiveness of financial incentives to motivate people to get vaccinated.

Multidimensional interventions

Ten studies investigated multidimensional interventions, that evaluated a mix of educational, communicational, and policy interventions as well as improved access (Howarth 2021; Jung 2021; Kerr 2021; Klüver 2021; Marquez 2021; Pfattheicher 2021; Senderey 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Sprengholz 2021c; Takamatsu 2021). For example, one study combined incentives with easy access to vaccines (Klüver 2021).

Educational interventions

Five studies investigated educational interventions such as workshops or information texts. Specifically, Kelkar 2021 conducted a webinar, Talmy 2021 investigated the use of workshops to educate soldiers about COVID‐19 vaccines, Thorpe 2021 used online fact boxes to educate veterans, Kobayashi 2021 investigated a chatbot answering questions about COVID‐19 and vaccines, and Tran 2021 utilised an interactive web tool to offer individualised information for users.

Policy interventions

One study investigated a policy intervention (Sprengholz 2021), specifically the effects of a mandatory vaccine policy.

Interventions to improve access

We did not identify any studies with published results that investigate the effects of improved access.

Control conditions

Most studies used control arms in which other intervention strategies were tested or in which the intervention was slightly altered (Argote 2021; Ashworth 2021; Bokemper 2021; Borah 2021; Duch 2021; Campos‐Mercade 2021; Capasso 2021; Chen 2021; Fox 2021; Galasso 2021; Gong 2021; Hong 2021; Howarth 2021; Huang 2021; Jin 2021; Jung 2021; Kachurka 2021; Kelkar 2021; Keppeler 2021; Klüver 2021; Kreps 2021; Merkley 2021; OCEAN; Palm 2021; Peng 2021; Pfattheicher 2021; Pink 2021; Reichardt 2021; Robertson 2021a; Robertson 2021b; Ryoo 2021; Senderey 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Sinclair 2021; Sotis 2021; Sprengholz 2021; Sprengholz 2021c; Strickland 2021; Sudharsanan 2021; Takamatsu 2021; Thorpe 2021; Thunström 2021; Tran 2021; Ye 2021; Yu 2021; Yu 2021b; Yuan 2021). Most studies had more than one control condition. Nine studies had control conditions with no intervention (Barber 2021; Brehm 2021; Kerr 2021; Schwarzinger 2021; Sehgal 2021; Thirumurthy 2021; Ugwuoke 2021; Walkey 2021; Witus 2021). One study had a delayed control condition (Santos 2021). Four studies were uncontrolled (Kobayashi 2021; Marquez 2021; Talmy 2021; Stein 2021).

Outcome measures

The willingness to get vaccinated for COVID‐19 was assessed as an outcome in 43 studies (Ashworth 2021; Argote 2021; Bokemper 2021; Borah 2021; Capasso 2021, Chen 2021; Fox 2021; Galasso 2021; Gong 2021; Howarth 2021; Huang 2021; Jin 2021; Jung 2021; Kachurka 2021; Klüver 2021; Kelkar 2021; Kerr 2021; Kobayashi 2021; Keppeler 2021; Kreps 2021; Merkley 2021; OCEAN; Palm 2021; Robertson 2021a; Robertson 2021b; Schwarzinger 2021; Serra‐Garcia 2021; Sudharsanan 2021; Sinclair 2021; Sprengholz 2021c; Strickland 2021; Tran 2021; Peng 2021; Pfattheicher 2021; Pink 2021; Thorpe 2021; Thunström 2021; Ugwuoke 2021; Witus 2021; Ye 2021; Yu 2021; Yu 2021b; Yuan 2021). Usually, this outcome was assessed with survey questions on the intention to get vaccinated.

A majority of studies (48 of 61) used an unvalidated questionnaire (e.g., “If there is a COVID‐19 vaccine available, are you willing to be vaccinated?” Gong 2021) to measure the willingness to get vaccinated or did not give any information on the source or their questionnaire. Some studies used only one question to measure the willingness to get vaccinated, while others used scales with more than one question. Validated questionnaires or questionnaires adapted from other studies were used in Borah 2021, Capasso 2021, Jin 2021, Kelkar 2021, Kerr 2021, OCEAN, Sinclair 2021, Peng 2021, Pfattheicher 2021, Sudharsanan 2021, Witus 2021, and Ye 2021. One study used the clicks on pages to register for a vaccine appointment as a proxy for the willingness to get vaccinated (Keppeler 2021).

Thirteen studies assessed vaccine uptake as an outcome (Barber 2021; Brehm 2021; Campos‐Mercade 2021; Hong 2021; Marquez 2021; Santos 2021; Sehgal 2021; Senderey 2021; Stein 2021; Takamatsu 2021; Talmy 2021; Thirumurthy 2021; Walkey 2021). This outcome was usually assessed using real‐world data on vaccination rates in the studied population. Reactance was measured in two studies (Reichardt 2021; Sprengholz 2021). Duch 2021 investigated further interest in vaccine information as an outcome. Vaccine hesitancy was measured in Ryoo 2021. Agreement with COVID‐19 passports was assessed in Sotis 2021.

Some studies also reported secondary outcomes. These were not mapped in the interactive scoping map and are further described in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Ongoing Studies

Please note that ongoing studies were also included in the mapping of the results.

Participants

Participant characteristics also differ between ongoing studies. African American and Latinx communities are addressed in four ongoing studies (NCT04761692; NCT04542395; NCT04779138; NCT05022472 (2VIDA!)). Furthermore, NCT04801030 plans to include African American adults and NCT04884750 churchgoers in Black churches in the USA. Ethnically diverse minority populations are being recruited in NCT04867174. Native American residents are recruited in NCT04964154 (BRAVE). NCT04871776 aims to address hospital patients, and NCT04834726 at‐risk patients. Nursing home residents and staff are participating in NCT04732819. NCT04876885 includes Ontario residents and healthcare professionals, and NCT05037201 employees in a US healthcare service. Patients are recruited in NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah), NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID), NCT04952376, NCT04963790, and NCT04981392. NCT04800965 and NCT04801524 aim to include university students. US veterans are participating in NCT04805931 (VEText). Adult US citizens participate in NCT04706403, NCT04951310, and NCT04979416, US and Chinese residents in DRKS00023650. ISRCTN15317247 includes UK citizens, NCT04895683 includes London citizens and NCT04813770 Scottish residents. US veterans are recruited in NCT05027464 (CoVAcS). Ugandan villagers participate in PACTR202102846261362. NCT04870593 aims to address elderly Indian residents. NCT04939506 addresses vaccine‐hesitant US adults. NCT04924803 aims to recruit drug users. All studies, except for NCT04604743 and NCT04960228 plan to include adults aged 18 years or older.

All ongoing studies report a sample size of more than 100 participants. Larger studies plan to recruit more than 20,000 participants (for example, DRKS00023650). For more detailed information on sample size, please see the Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Interventions

Interventions were grouped as educational interventions, incentives, policies, communication strategies, increased access and multidimensional interventions.

Communication interventions

Sixteen ongoing studies plan to test communication strategies to increase the willingness to vaccinate against COVID‐19. Nine of these studies plan the use of personalised communication strategies (ISRCTN15317247; NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); NCT04924803; NCT04805931 (VEText); NCT04834726; NCT04895683; NCT04952376; NCT04963790; NCT05027464 (CoVAcS); ) such as personalised text messages as reminders. The other studies use different strategies to persuade people to get vaccinated (NCT04706403; NCT04801524; NCT04871776; NCT04981392; NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID); PACTR202102846261362; NCT04884750).

Educational interventions

Twelve ongoing studies aim to investigate educational interventions such as workshops or information texts (DRKS00023650; NCT04604743; NCT04779138; NCT04801030; NCT04813770; NCT04876885; NCT04939506; NCT04960228; NCT04979416; NCT04964154 (BRAVE); PACTR202102846261362; NCT04542395).

Multidimensional interventions

Six ongoing studies plan to investigate multidimensional interventions that mix different intervention categories (NCT04732819; NCT04867174; NCT04761692; NCT04800965; NCT04870593; NCT05022472 (2VIDA!)).

Incentives

One ongoing study plans to investigate a lottery as an incentive to get vaccinated (NCT04951310).

Interventions to improve access

We did not identify any ongoing studies that investigate the effects of improved access.

Control conditions

To control intervention effects, a majority (18 of 35) of ongoing studies plan to use an active control (DRKS00023650; ISRCTN15317247; NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); NCT04981392; NCT04964154 (BRAVE); NCT04924803; NCT05022472 (2VIDA!); NCT04952376; NCT04963790; NCT05037201; NCT04761692; NCT04801524, NCT04813770; NCT04834726; NCT04867174; NCT04870593; NCT04884750; NCT04960228). Eleven studies compare the intervention to current practices (NCT04800965; NCT04801030; NCT04876885; NCT04732819; NCT04805931 (VEText); NCT04871776; NCT04895683; NCT04979416; NCT04951310; NCT05027464 (CoVAcS); NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID)). Three studies do not further specify the control condition (NCT04706403; PACTR202102846261362; NCT04604743) and three are uncontrolled (NCT04542395; NCT04779138; NCT04939506).

In summary, educational and multidimensional interventions are the most used types of interventions in ongoing studies. For a more detailed description of interventions, please see the Characteristics of ongoing studies table and the Table 1.

Outcome measures

Twenty‐four ongoing studies plan to assess vaccine uptake as an outcome (ISRCTN15317247; NCT04604743; NCT04779138; NCT04800965; NCT04801030; NCT04801524; NCT04805931 (VEText); NCT04834726; NCT04867174; NCT04884750; NCT04895683; NCT04870593; NCT04732819; NCT04761692; NCT04542395; NCT04939506; NCT04939519 (SCALE‐UP Utah); NCT04981392; NCT04964154 (BRAVE); NCT04924803; NCT04951310; NCT05027464 (CoVAcS); NCT04952376; NCT04963790). Usually, the studies plan to assess this outcome using real‐world data on vaccination rates in the studied population. Furthermore, the willingness to get vaccinated for COVID‐19 is assessed as an outcome in seven studies (NCT04706403; NCT04813770; NCT04876885; NCT05037201; NCT04960228; NCT04979416; NCT04930965 (LA‐CEAL: HALT COVID)). Usually, this outcome is assessed with survey questions on the intention to get vaccinated. One study aims to assess the decrease of vaccine hesitancy (DRKS00023650), and two studies the proportion of vaccine hesitancy among participants (NCT04801524; PACTR202102846261362). One study assesses vaccine confidence or trust (NCT05022472 (2VIDA!)). Some studies also reported secondary outcomes. These were not mapped in the interactive scoping mapand are further described in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified 101 eligible studies and classified five studies of these as awaiting classification since it was unclear from trial registries if they really are intervention studies. Of the 96 included studies, 61 studies have published results and 35 are ongoing. Interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake were very heterogeneous and included communication interventions (50), educational interventions (17), multidimensional interventions (16), and incentives (12), as well as policy interventions (1). The mapping of the results shows that interventions are mostly assessed with regard to their potential to increase the willingness to get vaccinated or COVID‐19 vaccine uptake. A smaller proportion of studies looked at interventions to decrease vaccine hesitancy. Only one study assessed the agreement with COVID‐19 policies as an outcome. A majority of studies was conducted in English‐speaking high‐income countries. Populations that were addressed were diverse with studies addressing healthcare workers, ethnic minorities in the US, students, soldiers, villagers, at‐risk patients, or the general population. A majority of the studies addressed adult participants. Most studies investigated the interventions in a randomised‐controlled setting.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence summarised here demonstrates a wide range of interventions addressing specific populations in English‐speaking high‐income countries. However, we could only identify a small number of studies set in low and middle‐income countries.

Moreover, we only identified four studies that focused specifically on young people. Since some vaccines against COVID‐19 are now also approved for young adults and children, it is of utmost importance to investigate interventions addressing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake in younger populations.

Until more evidence is available on the effects of interventions focused on increasing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake for lower‐middle‐income countries and younger populations, decision‐makers may want to draw on the findings of systematic reviews of related interventions to inform their decision‐making. For example, several Cochrane Systematic Reviews have investigated strategies to enhance vaccine uptake for other vaccines (Abdullahi 2020; Jacoboson Vann 2018; Kaufman 2018; Oyo‐Ita 2016; Thomas 2018).

None of the studies that we identified assessed the efficacy of policy interventions that have been implemented in 'real‐world' or practice settings. We only identified one study of policy interventions, and this investigated the effects of a hypothetical mandatory vaccine policy in a laboratory setting (Sprengholz 2021). With strategies such as mandatory vaccination or travel restrictions for unvaccinated people being discussed or implemented, studies to evaluate the impact of such strategies are becoming increasingly important. Moreover, we only identified one multidimensional study that investigated the effects of improved access (Klüver 2021) and no study only investigating improved access. Since interventions based on increased access to vaccines are effective in other contexts (Dubé 2015), this research gap should be addressed in future studies. Overall, the description of interventions was very heterogeneous and differed in detail. Especially for ongoing studies, interventions often were not well‐described and thus our categorization of them is preliminary.

Finally, while validated questionnaires to measure the willingness to get vaccinated or vaccine hesitancy are available, the majority of the included studies did not use these. Future studies should employ validated instruments to measure COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy and willingness.

Potential biases in the review process

While we published a protocol for this review beforehand (Andreas 2021), it was not peer‐reviewed by external experts. Furthermore, although we registered the protocol in advance, the studies that we identified made a change to the intervention categorisation necessary. We adapted the intervention categories to better fit the evidence. Specifically, we added the category “multidimensional interventions” as many studies used a mixture of intervention categories. Additionally, instead of summarising education interventions under communication strategies, it became a separate category. We also added "interventions to improve access" as a separate category. These changes enabled us to more accurately map our findings.

We identified no other potential sources of bias in our review process.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for research and practice

We were able to identify and map a number of heterogeneous interventions for increasing COVID‐19 vaccine uptake or decreasing vaccine hesitancy. Our results demonstrate that this is an active field of research with 61 published studies and 35 studies still ongoing. The contexts and populations in which the interventions were tested were diverse and thus enable policymakers to identify evidence for specific populations.

While we could identify a heterogenous evidence base for interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake in this scoping review, future research should address the following research gaps:

Developing and evaluating intervention strategies in low and middle‐income countries in order to inform health policies in these contexts

The majority of studies were conducted in experimental settings only. Studies are also needed on the effectiveness of interventions already in use in routine practice

Developing and evaluating interventions that address adolescents or children

Developing and evaluating interventions to improve access to vaccination

Developing and evaluating policy interventions

Few studies use validated questionnaires to measure outcomes such as the willingness to vaccinate. Future research should therefore develop and use validated instruments for these outcomes

Implications for a subsequent effectiveness review

This scoping review cannot answer the question of which interventions are most effective to increase COVID‐19 vaccine willingness. However, it provides a systematic overview of interventions, study design, populations, and settings of studies researching interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake and willingness to vaccinate. We identified 61 published studies and an additional 35 ongoing studies, many of which are RCTs. Furthermore, many ongoing studies have estimated completion dates in 2022. Thus, a systematic review comparing the effectiveness of the various interventions to increase COVID‐19 vaccine uptake seems both feasible and warranted.

Nevertheless, this scoping review has also highlighted some challenges of conducting a subsequent systematic review. Firstly, the COVID‐19 pandemic is rapidly evolving, both within and between countries, making it hard to compare studies conducted in different contexts. Criteria such as the timing of the intervention should therefore be considered as subgroup analyses in a meta‐analysis. Secondly, this scoping review has demonstrated that a range of different measures to increase vaccine uptake exist. It follows that the comparison of different interventions in a systematic review with meta‐analysis might be difficult, especially regarding study heterogeneity. Thus, comparing effectiveness within an intervention category might be most appropriate for a subsequent systematic review. Furthermore, in the process of writing this review, we have adapted the categorisation system for interventions to better differentiate between the numerous intervention types we identified. The updated system can be used for a subsequent systematic review or similar scoping reviews; however, whether further adjustments will be required, remains to be seen.

Finally, the dynamic nature of the COVID‐19 pandemic highlights the importance of providing up‐to‐date evidence to inform policy decisions. New variants and new vaccines have emerged while we worked on this scoping review, that have likely impacted the ability of vaccines to block transmission and may have influenced willingness to get vaccinated. To best reflect the fast‐paced COVID‐19 pandemic, a living systematic review might be most appropriate.

In conclusion, as COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy remains an urgent topic in most countries, a future systematic review can help to inform evidence‐based strategies to address the willingness to vaccinate against COVID‐19.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2022 | Amended | Edits to faulty hyperlinks |

History

Review first published: Issue 8, 2022

Acknowledgements

This review was published in collaboration with the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group. We would like to thank the Co‐ordinating Editor Simon Lewin for his excellent editorial support and valuable comments on the review.

We would like to thank the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) for making their software to create user evidence maps available to us and for supporting us throughout the process of creating the map.

We thank the team of the Referat für Medizinische Versorgung, Infektionsschutz, Hygiene from the Ministerium für Arbeit, Gesundheit und Soziales des Landes Nordrhein‐Westfalen for their participation in our stakeholder discussions and their valuable feedback on this scoping review.

The research was part of the Willie‐Vacc project supported by the German Research Foundation (Enhancing the willingness of healthcare workers to be vaccinated against COVID‐19 in Germany (SK 146/3‐1)).

We thank Jo Platt (Information Specialist, Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancer Group) for peer‐reviewing the search strategy.

Editorial and peer‐reviewer contributions:

The following people conducted the editorial process for this article.

Sign‐off Editor (final editorial decision): Simon Lewin; Joint Co‐ordinating Editor of Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC), Norweigan Institute for Public Health Managing Editor (selected peer reviewers, collated peer‐reviewer comments, provided editorial guidance to authors, edited the article): Helen Wakeford, Central Editorial Service, Cochrane Editorial Assistant (conducted editorial policy checks and supported editorial team): Leticia Rodrigues, Central Editorial Service, Cochrane Copy Editor (copy editing and production): Heather Maxwell, Cochrane Peer‐reviewers (provided comments and recommended an editorial decision): Jessica Kaufman, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Holly Seale, University of New South Wales, and Majdi Sabahelzain, School of Health Sciences, Ahfad University for Women (clinical/content review), Solmaz Piri(consumer review), Chantelle Garrity (methods review), Robin Featherstone, Central Editorial Service (search review), Simon Lewin, Co‐ordinating Editor, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC).

Appendices

Appendix 1. PRISMA‐ ScR Checklist for this review

| Item | PRISMA‐ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | Done? | Section |

| 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | yes | Title |

| 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | yes | Abstract |

| 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | yes | Background |

| 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | yes | Objective |

| 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | yes | Methods |

| 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | yes | Methods |

| 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | yes | Methods |

| 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | yes | Appendix |

| 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | yes | Methods |

| 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | yes | Mehods |

| 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | yes | Methods |

| 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | No; No critical appraisal conducted | |

| 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | yes | Methods |

| 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | yes | Figure 1: Flow diagram |

| 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | yes | Characteristics of included studies Table |

| 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | No; No critical appraisal conducted | |

| 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | yes | Summary of findings table, Interactive scoping map |

| 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | yes | Results |

| 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | yes | Results |

| 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | yes | Discussion |

| 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | yes | Discussion |

| 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | yes | Sources of support, Acknowledgements |

[Enter text here]

Appendix 2. Search Strategies for Evidence Syntheses

Evidence Aid Coronavirus (Covid‐19) (evidenceaid.org/evidence/coronavirus-covid-19/)

searched by text word vaccin*

Usher Network for COVID‐19 Evidence Reviews (www.ed.ac.uk/usher/uncover/register-of-reviews)

searched by text word vaccin*

Epistemonikos L*OVE Covid‐19 (app.iloveevidence.com/loves)

search by text word vaccin* and limited to broad syntheses and systematic review

MEDLINE (Ovid 1946 to present)

# Searches

1 (COVID or "COVID‐19" or COVID19 or "SARS‐CoV‐2" or "SARS‐CoV2" or SARSCoV2 or "SARSCoV‐2").tw,kf.

2 (vaccin* adj5 (hesitanc* or hesitant* or hesitat* or uptake or "up‐take" or "take up" or trust* or distrust* or misinformation or barrier* or refusal or resist* or "anti‐vaccination" or "anti vaccine" or willing* or unwilling* or intent* or accept* or perception* or behaviour* or behavior* or belief* or view* or opinion or communication* or perspective* or attitude* or knowledge or concern or concerns or concerned or motivation or reject or confidence or "undecided" or "irresolute" or uncertain or nonintent or decide or deciding or decision* or consent* or perceiv* or aware*)).tw,kf.

3 cochrane database of systematic reviews.jn. or search*.tw. or meta analysis.pt. or medline.tw. or systematic review.tw. or systematic review.pt.

(Wong 2006 – systematic reviews filter – high specificity, 90,2% sens / 98,4% spec)

4 1 and 2 and 3

5 limit 4 to yr="2020 ‐Current"

Appendix 3. Search Strategies for Primary Literature

Cochrane COVID‐19 study register

vaccin*

AND

hesitanc* or hesitant* or hesitat* or uptake or "up‐take" or "take up" or trust* or distrust* or misinformation or barrier* or refusal or resist* or "anti‐vaccination" or "anti vaccine" or willing* or unwilling* or intent* or accept* or perception* or behaviour* or behavior* or belief* or believ* or view* or opinion* or communication* or perspective* or attitude* or knowledge or concern or concerns or concerned or motivation or reject or confidence or "undecided" or "irresolute" or uncertain or nonintent or decide or deciding or decision* or consent* or perceiv* or aware* or vaxxer* or "vaccination rates" or intend* or message* or encourage* or framing*

Web of Science

#1 TI=((vaccin* NEAR/5 (COVID OR COVID19 OR "SARS‐CoV‐2" OR "SARS‐CoV2" OR SARSCoV2 OR "SARSCoV‐2" OR "SARS coronavirus 2" OR "2019 nCoV" OR "2019nCoV" OR "2019‐novel CoV" OR "nCov 2019" OR "nCov 19" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "novel coronavirus disease" OR "novel corona virus disease" OR "corona virus disease 2019" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "novel coronavirus pneumonia" OR "novel corona virus pneumonia" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2")))) OR AB=((vaccin* NEAR/5 (COVID OR COVID19 OR "SARS‐CoV‐2" OR "SARS‐CoV2" OR SARSCoV2 OR "SARSCoV‐2" OR "SARS coronavirus 2" OR "2019 nCoV" OR "2019nCoV" OR "2019‐novel CoV" OR "nCov 2019" OR "nCov 19" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "novel coronavirus disease" OR "novel corona virus disease" OR "corona virus disease 2019" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "novel coronavirus pneumonia" OR "novel corona virus pneumonia" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"))

#2 TI=((hesitanc* OR hesitant* OR hesitat* OR uptake OR "up‐take" OR "take up" OR trust* OR distrust* OR misinformation OR barrier* OR refusal OR resist* OR "anti‐vaccination" OR "anti vaccine" OR willing* OR unwilling* OR intent* OR accept* OR perception* OR behaviour* OR behavior* OR belief* OR believ* OR view* OR opinion* OR communication* OR perspective* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR concern OR concerns OR concerned OR motivation OR reject OR confidence OR "undecided" OR "irresolute" OR uncertain OR nonintent OR decide OR deciding OR decision* OR consent* OR perceiv* OR aware* OR vaxxer* OR "vaccination rates" OR intend* OR message* OR encourage* OR framing*))) OR AB=((hesitanc* OR hesitant* OR hesitat* OR uptake OR "up‐take" OR "take up" OR trust* OR distrust* OR misinformation OR barrier* OR refusal OR resist* OR "anti‐vaccination" OR "anti vaccine" OR willing* OR unwilling* OR intent* OR accept* OR perception* OR behaviour* OR behavior* OR belief* OR believ* OR view* OR opinion* OR communication* OR perspective* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR concern OR concerns OR concerned OR motivation OR reject OR confidence OR "undecided" OR "irresolute" OR uncertain OR nonintent OR decide OR deciding OR decision* OR consent* OR perceiv* OR aware* OR vaxxer* OR "vaccination rates" OR intend* OR message* OR encourage* OR framing*)

#3 #1 AND #2

WHO COVID‐19 global literature on coronavirus disease

Advanced search:

vaccin*

AND

hesitanc* or hesitant* or hesitat* or uptake or "up‐take" or "take up" or trust* or distrust* or misinformation or barrier* or refusal or resist* or "anti‐vaccination" or "anti vaccine" or willing* or unwilling* or intent* or accept* or perception* or behaviour* or behavior* or belief* or believ* or view* or opinion* or communication* or perspective* or attitude* or knowledge or concern or concerns or concerned or motivation or reject or confidence or "undecided" or "irresolute" or uncertain or nonintent or decide or deciding or decision* or consent* or perceiv* or aware* or vaxxer* or "vaccination rates" or intend* or message* or encourage* or framing*

PscycINFO Ovid

Search Strategy:

# Searches

1 immunization/

2 covid‐19/

3 (vaccin* adj8 (covid or covid‐19 or covid19 or "SARS‐CoV‐2" or "SARS‐CoV2" or SARSCoV2 or "SARSCoV‐2" or "SARS coronavirus 2")).mp.

4 (hesitanc* or hesitant* or hesitat* or uptake or "up‐take" or "take up" or trust* or distrust* or misinformation or barrier* or refusal or resist* or "anti‐vaccination" or "anti vaccine" or willing* or unwilling* or intent* or accept* or perception* or behaviour* or behavior* or belief* or believ* or view* or opinion* or communication* or perspective* or attitude* or knowledge or concern or concerns or concerned or motivation or reject or confidence or "undecided" or "irresolute" or uncertain or nonintent or decide or deciding or decision* or consent* or perceiv* or aware* or vaxxer* or "vaccination rates" or intend* or message* or encourage* or framing*).mp.

5 202*.up.

6 1 and 2

7 (3 or 6) and 4 and 5

CINAHL EBSCO

S1 MH "COVID‐19 Vaccines"

S2 MH "Anti‐Vaccination Movement"

S3 MM "Immunization"

S4 MH "COVID‐19"

S5 TX (vaccin* N8 (covid or covid‐19 or covid19 or "SARS‐CoV‐2" or "SARS‐CoV2" or SARSCoV2 or "SARSCoV‐2" or "SARS coronavirus 2"))

S6 S1 OR ( S4 AND (S2 OR S3) ) OR S5

S7 TX hesitanc* or hesitant* or hesitat* or uptake or "up‐take" or "take up" or trust* or distrust* or misinformation or barrier* or refusal or resist* or "anti‐vaccination" or "anti vaccine" or willing* or unwilling* or intent* or accept* or perception* or behaviour* or behavior* or belief* or believ* or view* or opinion* or communication* or perspective* or attitude* or knowledge or concern or concerns or concerned or motivation or reject or confidence or "undecided" or "irresolute" or uncertain or nonintent or decide or deciding or decision* or consent* or perceiv* or aware* or vaxxer* or "vaccination rates" or intend* or message* or encourage* or framing*

S8 S6 AND S7

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Argote 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | Different information about COVID‐19 vaccine:

Motivation treatment:

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | COI: NR Funding: NR |

|

Ashworth 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | Different messaging about benefits of the COVID‐19 vaccine:

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Barber 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | Lottery | |

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes | Vaccine uptake | |

| Notes |

|

|

Bokemper 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | Experiment 1:

Experiment 2: The statement was randomly assigned to one of six values, (1) a positive or (2) negative statement by Dr. Anthony Fauci, (3) a positive or (4) negative statement by President Trump, (5) a joint positive statement by Trump and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, or (6) a positive Trump statement and a negative Pelosi statement |

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

|

|

| Notes | Sponsor/ funding: NR COI: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. |

|

Borah 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | Framing

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Brehm 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions | "Vax‐a‐Million" Lottery | |

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes | Vaccine uptake | |

| Notes |

|

|

Campos‐Mercade 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Interventions |

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|