In this issue of Blood, Niemann et al1 investigate the outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The outcomes cover a span of almost 2 years. The authors focused on the surges of different SARS-CoV-2 variants, and they found a much milder course for COVID-19 during the time that the omicron variant was dominant, with a 30-day mortality rate as low as 1% in younger patients not tested at hospital sites.

On the basis of the data collected in the Danish registry, the authors analyzed the outcomes of populations tested at hospital sites (patient data were thereby included in the electronic health records [EHRs] system) during 4 different time periods between March 2020 and the end of January 2022. They found a significant improvement in the period from November 2021 to January 2022, when omicron and its subvariant BA.2 first emerged and then became dominant. The 30-day hospital admission rates declined from 83% to 55%, intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates declined from 13% to 0%, and 30-day overall survival improved from 83% to 91% (during the period when the omicron variant dominated), but decreased again to 77% with the occurrence of the BA.2 subvariant. Even more importantly, when the analysis was extended to include 640 patients in the CLL registry who tested positive (by polymerase chain reaction assay) for SARS-CoV-2 outside the EHRs system, the 30-day overall survival increased from 88% to 98% over the observation period.

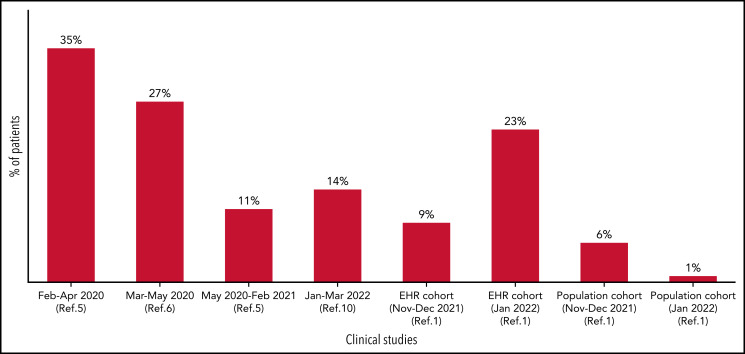

With more than 510 000 000 infections and more than 6 200 000 cumulative deaths worldwide (https://covid19.who.int/ as of 15 May 2022), COVID-19 has had a dramatic impact on populations all over the world. Patients with hematologic malignancies are more profoundly affected because they have a 34% mortality rate when hospitalized as a result of COVID-19.2 Among those with hematologic malignancies, patients with CLL were at higher risk because of CLL-associated immune dysfunction. Patients with CLL who required active treatment had a worse outcome, even in the era of targeted agents. Large retrospective series during the first wave of COVID-19 documented a case fatality rate as high as 33%,3,4 with an improvement to 20% during the second wave in 1 international retrospective cohort of hospitalized patients with CLL.5 However, this more favorable outcome was not confirmed in a large European cohort of 941 patients with CLL and COVID-19 (see Figure); in that case, the fatality rate of hospitalized patients actually increased slightly to 38.4%.6

COVID-19–related mortality in patients with CLL over time. The COVID-19–related mortality in patients with CLL during different waves of COVID-19 (initial studies on the left) is depicted. Initial studies (up to 35%, on the left) reported the highest mortality rate for COVID-19, whereas more recent retrospective series documented a much lower mortality rate (1%-23%, depending on the setting of data collection).

Since December 2020, the availability of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 raised hopes of preventing severe disease. As expected, vaccine response is impaired in patients with CLL. Only 40% of patients developed detectable antibodies after 2 vaccine doses (ranging from 80% in those in clinical remission to 0% in those receiving active anti-CD20 therapy) with generally lower titers in those who do respond.7 The jury is still out regarding the dynamics of the T-cell response after vaccination. The results are contradictory regarding the generation and reactivity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with hematologic malignancies.8 This is expected, considering that the evaluation of T-cell function is complex and that it is more difficult to reliably assess cellular responses. Despite the need for further studies to better address the immune response, primary vaccination and booster doses are recommended for all patients with CLL regardless of serological results. In addition to vaccines, several treatment modalities, including monoclonal antibodies (eg, sotrovimab, etesevimab-bamlanivimab, imdevimab-casirivimab) and antiviral treatments (initially remdesivir, then nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and molnupiravir) have been approved to prevent infections from progressing from mild-moderate to severe. These treatments have been administered to immunocompromised patients and are associated with improved outcomes.8 However, most of the monoclonal antibody products rapidly fell from grace because they were largely ineffective for the novel variants of concern that keep emerging. Recently, the combination of 2 long-acting antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab, has been authorized as pre-exposure prophylaxis for COVID-19 in patients who are moderately to severely immunocompromised. The initial authorized dose of tixagevimab/cilgavimab was increased to 300 mg/300 mg because higher doses increase the chance of preventing infection by the omicron subvariants.

In this challenging scenario, the study by Niemann et al suggests that the odds that patients with CLL can control their SARS-CoV-2 infection and avoid severe manifestations (including death) are improving. Recent work has suggested that, in the general population, the risk of severe outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection is substantially lower for those infected with the omicron variant, including for more severe end points.9 The analysis by Niemann et al concentrates on immunocompromised patients and confirms that this reduction in the risk of severe outcomes also holds true for younger patients with CLL who are not included in the EHR system. When focusing on the cohort with data extracted from the EHRs system, even though hospitalization and ICU admission rates declined, the mortality rate maintained high at 23% during the period when omicron sublineage BA.2 dominated. Because the EHR population was characterized by an older median age and the need for hospital access, this category of patients is more fragile. They would benefit from timely screening, prompt intervention, and close follow-up to avoid a dismal outcome. These findings are in keeping with the recent report from the Israeli group10 of a 31% case fatality rate in hospitalized patients with CLL during the time of omicron dominance (January to March 2022).

The study by Niemann et al has some limitations. The data we analyzed were extracted from EHRs and/or a registry in which information on SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels, number of vaccine doses received, and specifics of COVID-19 prophylaxis were missing. No information on hospitalization rate or ICU admission was available for the population cohort. Nevertheless, the findings of this study, if validated in different settings, would suggest that we are indeed making progress in managing patients with CLL and COVID-19. Although it is not clear how much each of the pieces (vaccines, other prophylactic and mitigation measures, treatment, and the properties of viral strains) contributed to the improvement, the trend is favorable. Hopefully, we can continue to drastically reduce the mortality rate in this vulnerable patient population by maximally exploiting each component of the antiviral strategies and improving them. It is also critically important to make each of these components available to all patients with CLL worldwide. Progress has been made, but more needs to be done to remove the COVID-19 shackles from patients with CLL.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.S. was a member of advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Janssen. Y.H. has received honoraria from Janssen, AbbVie, Roche, Astra-Zeneca and Medison Pharma.

REFERENCES

- 1.Niemann CU, da Cunha-Bang C, Helleberg M, Ostrowski SR, Brieghel C. Patients with CLL have a lower risk of death from COVID-19 in the Omicron era. Blood. 2022;140(5):445-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood. 2020;136(25):2881-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mato AR, Roeker LE, Lamanna N, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with CLL: a multicenter international experience. Blood. 2020;136(10):1134-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarfò L, Chatzikonstantinou T, Rigolin GM, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a joint study by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL, and CLL Campus. Leukemia. 2020;34(9):2354-2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roeker LE, Eyre TA, Thompson MC, et al. COVID-19 in patients with CLL: improved survival outcomes and update on management strategies. Blood. 2021;138(18):1768-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatzikonstantinou T, Kapetanakis A, Scarfò L, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with CLL: an update of the international ERIC and Campus CLL study. Leukemia. 2021;35(12):3444-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(23):3165-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langerbeins P, Hallek M. COVID-19 in patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2022;140(3):236-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. ; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium . Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronstein Y, Gat R, Levi S, et al. COVID-19 in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases during the Omicron variant surge. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(6):578–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.