Abstract

Background

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma-cell disease that arises on the basis of a so-called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). The median age at disease onset is over 70. In Germany, there are approximately eight new cases per 100 000 inhabitants per year, or about 6000 new patients nationwide each year.

Methods

To prepare this clinical practice guideline, a systematic literature review was carried out in medical databases (MEDLINE, CENTRAL), guideline databases (GIN), and the search portal of the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). The recommendations to be issued were based on two international guidelines, 40 dossier evaluations and systematic reviews, 10 randomized controlled trials, and 37 observational studies and finalized in a structured consensus process.

Results

Because of its prognostic relevance, the use of the International Staging System (ISS) is recommended to stage MM and related plasma-cell neoplasms. When symptomatic MM is diagnosed, it is recommended to determine the extent of skeletal involvement by whole-body computed tomography. The indications for treatment shall be determined on the basis of the SLiM-CRAB criteria; in all patients with MM it is recommended to include the biological (rather than chronological) age in the decision-making process. In suitable patients, it is recommended that initial treatment includes high-dose therapy, followed by maintenance treatment. Even without high-dose treatment, a median progression-free survival of more than three years can be achieved with combination therapies. For the treatment of relapse, combinations of three drugs are more effective than doublet regimens with a median progression-free survival ranging from 10 to 45 months, depending on the study and prior therapy. Following anti-myeloma therapy, it is recommended to promptly offer physical exercise adapted to individual abilities to all patients who have the potential for rehabilitation, so that their quality of life can be sustained and improved.

Conclusion

This new clinical practice guideline addresses, in particular, the modalities of care that can be offered in addition to systemic antineoplastic therapy. In view of the significant recent advances in the treatment of myeloma, affected patients’ quality of life now largely depends on optimized interdisciplinary care.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disease and the second most common hematologic malignancy (1). It undergoes a more or less obligatory development from a precancerous condition called monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) and is characterized by nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue or diffuse aches and pains in the limbs. The incidence of MM in Germany is around eight new cases per 100 000 inhabitants per year, with a median onset age at diagnosis of >70 years (as of 2018; [2]). Between 1990 and 2016, the incidence rate has increased by 126% worldwide and is still rising, due in part to the growing and aging global population (2). In Germany, there were around 6350 new cases and 4180 deaths in 2018 (3).

Treatment options are constantly changing, with newly introduced drug groups and combinations that can be administered sequentially. So, although MM is not curable in most patients, it is now possible to achieve responses lasting several years. To provide a comprehensive, patient-centered management using these improved treatment options entails new challenges for diagnostics, prevention of complications, and symptom control.

The S3 consensus guideline, which has been prepared for the first time for Germany, compiles the current knowledge on this extensive topic and derives standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with MGUS and MM.

Methods

The S3 guideline was developed by an interdisciplinary group of clinicians, methodologists, patient representatives, and representatives of 25 professional societies and both German MM study groups (German-Speaking Myeloma Multicenter Group [GMMG], German Study Group Multiple Myeloma [DSMM]) under the auspices of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). It is published by the German Guideline Program in Oncology (GGPO) of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) in Germany, the German Cancer Society (DKG), and the German Cancer Aid (DKH). The participating professional societies and experts are listed in the eBox.

eBox. Professional societies, organizations, experts and participants.

Participating professional societies and organizations:

1) German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO) (in charge)

2) Working Group on Supportive Measures in Oncology (AGSMO)

3) Working Group on Oncological Rehabilitation and Social Medicine (AGORS)

4) Drug Control Board of the German Medical Profession (AKdÄ)

5) Working Group on Radiological Oncology (ARO)

6) Federal Association of German Pathologists (BDP)/German Society of Pathology (DGP)

7) Professional Association of Private-practice Hematologists and Oncologists in Germany (BNHO)

8) German Working Group on Bone Marrow and Blood Stem-Cell Transplantation (DAG-KBT)

9) German Society for Interventional Radiology and Minimally Invasive Therapy (DeGIR)

10) German Society for Radiation Oncology (DEGRO)

11) German Society of Nephrology (DGfN)

12) German Society for Geriatrics (DGG)

13) German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM)

14) German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (DGKL)

15) German Society of Nuclear Medicine (DGN)

16) German Society for Orthopedic and Trauma Surgery (DGOU)

17) German Society for Palliative Medicine (DGP)

18) German Society for Nursing Science (DGP)

19) German Leukemia & Lymphoma Aid (DLH)

20) German Network for Health Services Research (DNVF)

21) German Radiological Society (DRG)

22) German Society for Human Genetics (GfH)

23) German Society for Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology (GMDS)

24) Conference of Oncological and Pediatric Care (KOK)/German Cancer Society (DKG)

25) Working Group on Psycho-oncology (PSO)

Participating study groups:

German-speaking Myeloma Multicenter Group (GMMG)

German Study Group Multiple Myeloma (DSMM)

Participating experts:

Dr. Walter Baumann, retired (20) *,c,k

Dr. Marc-Andrea Bärtsch, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology and Rheumatology g

Dr. Bettina Beuthien-Baumann, German Cancer Research Center Heidelberg, Department of Radiology d

Prof. Dr. Thomas Benzing, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine II (11) *,f

University Lecturer Dr. Reiner Caspari, Niederrhein Hospital (3) **,i

Prof. Dr. Stefan Delorme, German Cancer Research Center Heidelberg, Department of Radiology (21) *,d,k

Prof. Dr. Thorsten Derlin, Hanover Medical School, Department of Nuclear Medicine (15) *,d,k

Dr. Sandra Maria Dold, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I e

Dr. Peter Eichhorn, Munich University Hospital, Institute for Laboratory Medicine (14) *,d

Prof. Dr. Hermann Einsele, Würzburg University Hospital, Medical Clinic and Polyclinic II (8) **,h

Prof. Dr. Monika Engelhardt, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I (1) *,e,h,k

Prof. Dr. Falko Fend, Tübingen University Hospital, Institute for Pathology and Neuropathology (6) *,d,k

University Lecturer Dr. Sebastian Fetscher, Sana Clinics Lübeck (4) *,b,f,g,h,j

M.Sc. Vanessa Piechotta, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I b

M.Sc. Angela Aldin, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I b

Dr. Christina Gerlach M.Sc., Mainz University Medical Center, Interdisciplinary Department of Palliative Care; Heidelberg University Hospital, Clinic for Palliative Care (17) **,j

University Lecturer Dr. Valentin Goede, St. Marien Hospital Cologne (12) *,e

Prof. Dr. Hartmut Goldschmidt, (NCT), Heidelberg University Hospital and National Center for Tumor Diseases, - Heidelberg Myeloma Centre and Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology (1) *,g

Dr. Giulia Graziani, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I h

Dr. Lana Harder, Institute for Tumor Genetics North (22) **,d,k

Matthias Hellberg-Naegele, Zurich Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Zurich University Hospital (24) *,g,h,j

University Lecturer Dr. Marco Herling, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I d

Prof. Dr. Jens Hillengaß, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center d

University Lecturer Dr. Karin Hohloch, Zurich Oncocenter Hirslanden (2) *,e,j

Maximilian Holler, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I e

University Lecturer Dr. Dr. Udo Holtick, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I (1) **,h

Dr. Ulrike Holtkamp, DLH (19) *,h

Dr. Stefanie Huhn, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology d

Prof. Dr. Michael Hundemer, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology d

Dr. Georg Jacobs, Practice for Hematology and Oncology Jacobs Duas Zwick (7) **

Prof. Dr. Anna Jauch, Heidelberg University Hospital, Institute for Human Genetics (22) *,d

Dr. Lukas John, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology g

Dr. Dr. Johannes Jung, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I (1) **,h,k

Prof. Dr. Torsten Kluba, Dresden Hospital, Department of Orthopedics and Orthopädic Surgery (16) *,f

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Knauf, self-employed (7) *,c,e,h

Prof. Dr. Stefan Knop, Würzburg University Hospital, Medical Clinic and Polyclinic II h

University Lecturer Dr. Katharina Kriegsmann, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology d

Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Nicolaus Kröger, Hamburg Eppendorf University Medical Center, Medical Clinic and Polyclinic for Stem Cell Transplantation (8) *,g

Dirk Lang, Ulm University Hospital, Psychosocial Cancer Counseling Center (25) **,j,k

Prof. Dr. Constantin Lapa, Augsburg University Hospital, Nuclear Medicine (15) **,d,k

Jan Lüneburg, retired (19) **

Klaus-Werner Mahlfeld, retired (19) **

Dr. Elias K. Mai, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology g

Dr. Patrick Marschner, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I k

University Lecturer Dr. Maximilian Merz, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology; Leipzig University Hospital, Clinik and Polyclinic for Hematology, Cell Therapy and Hemostaseology d

Prof. Dr. Markus Munder, Mainz University Hospital, Medical Clinic and Polyclinic III (13) *,g,h

University Lecturer Dr. Claas Philip Nähle, Cologne University Hospital, Institute of Diagnostics and Interventional Radiology (9) *,f

Prof. Dr. Marc-Steffen Raab, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Hematology, Oncology, Rheumatology (1) **,d

Dr. Christina Ramsenthaler, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland; Hull York Medical School, Heslington, UK; King’s College London, London, UK j

Heinrich Recken, Hamburg Open University (18) *,i,j

Dr. Heike Reinhardt, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I e,h

Veronika Riebl, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I h

Prof. Dr. Andreas Rosenwald, Institute of Pathology, University of Würzburg (6) **

Prof Dr. Dr. c. h. Christof Scheid, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I (1) *,a,d,k

Dr. Sophia Scheubeck, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I e

Dr. Maximilian Schinke, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I k

University Lecturer Dr. Börge Schmidt, Essen University Hospital, Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometrics and Epidemiology (23) *,b

Katja Schoeller, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I e

Dr. Mario Schubert, Hamm Clinics (3) *,i

University Lecturer Dr. Robert Semrau, Radiotherapy Bonn-Rhein-Sieg (5) *,f,g

Dr. Bianca Senf, Frankfurt am Main University Hospital, University Cancer Center (25) *,j

Prof. Dr. Steffen Simon, Cologne University Hospital, Center for Palliative Medicine (17) *,j

University Lecturer Dr. Daniela Trog, Lukas Hospital, Neuss (10) *,d,g,k

Dr. Linus Alexander Völker, Cologne University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine II f

Prof. Dr. Ralph Wäsch, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine h,k

Prof. Dr. Tim Weber, Heidelberg University Hospital, Department of Diagnostics and Interventional Radiology (21) **,d,k

Dr. Niels Weinhold, Heidelberg University Hospital, Multiple Myeloma Section d

Dr. Matthias Weiß, Freiburg University Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine I k

Prof. Dr. Katja Weisel, Hamburg Eppendorf University Hospital, Medical Department II, Oncology, Hematology, Bone Marrow Transplantation with Division of Pneumology f

Numbers in brackets refer to membership of professional societies

| *: | Elected representative with voting rights |

| **: | Representative |

| a: | Working group: Aims of the Guideline |

| b: | Working group: Epidemiology |

| c: | Working group: Healthcare structures |

| d: | Working group: Diagnostics, staging classification and prognostic assessment |

| e: | Working group: Age and comorbidity |

| f: | Working group: Complications |

| g: | Working group: Timing and choice of first-line therapy |

| h: | Choice of therapy for recurrence |

| i: | Working group: Rehabilitation |

| j: | Working group: Supportive therapy, psycho-oncology und palliative medicine |

| k: | Working group: Scheduling of follow-up reviews (survivorship) |

The address details apply to the time of guideline completion.

After defining key questions and patient-relevant endpoints, a literature review was conducted (carried out by V. P., the eTable presents the search strategy). The results of the literature search were evaluated on the basis of their methodological quality. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach (“Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Approach”) (4). The recommendation strength of statements and recommendations that were not evidence-based was decided by expert consensus of the guideline group.

eTable. Drug overview of the indications approved for adult patients with multiple myeloma according to drug product information*.

| Drug | Approved therapy combinations | Approved indications | Important adverse reactions | Other information |

| Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD) | ||||

| Thalidomide (T) | Melphalan/prednisone (MPT) | ● untreated MM ≥ 65 yearsor ● pats. for whom high-dose chemotherapy is not an option |

● embryotoxicity ● polyneuropathy ● fatigue ● diarrhea ● thrombosis ● susceptibility to infections ● blood count changes ● elevated liver function tests ● tremor ● skin reactions ● somnolence ● constipation ● peripheral edema ● risk of secondary primary cancer |

● oral administration ● teratogenic – distribution to women of childbearing age only via pregnancy prevention program ● risk of hepatitis B reactivation ● thromboembolism prophylaxis based on risk factors |

| Bortezomib/dexamethasone(VTD) | ● untreated MM ● induction therapy ● eligible for HD with ASCT |

|||

| Daratumumab/bortezomib/ dexamethasone (Dara-VTd) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM ● eligible for ASCT |

|||

| lenalidomidee (R) | Monotherapy | ● maintenance therapy ● newly diagnosed MM after ASCT |

● embryotoxicity ● diarrhea ● thrombosis ● susceptibility to infections ● blood count changes ● elevated liver function tests ● heart disease ● muscle pain ● risk of secondary primary cancer |

● oral administration ● not approved for RVD induction therapy prior to ASCT, rejected by EMA ● teratogenic – distribution to women of childbearing age only via pregnancy prevention ‧program ● risk of hepatitis B reactivation ● thromboembolism prophylaxis based on risk factors |

| Dexamethasone (Rd) | ● untreated MM ● non-transplant pats.; after at least one previous treatment |

|||

| Bortezomib/dexamethasone (RVD or VRd) | ● untreated MM ● non-transplant pats. |

|||

| Melphalan/prednisone (RMP) | ● untreated MM ● non-transplant pats. |

|||

| Carfilzomib/dexamethasone (KRd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Ixazomib/dexamethasone (Ixa-Rd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Daratumumab/dexamethasone (Dara-Rd) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM, who are not eligible for ASCT ● after at least 1 previous treatment |

|||

| Elotuzumab/dexamethasone(Elo-Rd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Pomalidomide (P) | Bortezomib/dexamethasone (PVd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment, including lenalidomide | ● pancytopenia ● thromboembolic event ● pneumonia ● shortness of breath ● hypokalemia ● hyperglycemia ● risk of secondary primary cancer |

● oral administration ● teratogenic – distribution to women of childbearing age only via pregnancy prevention program ● risk of hepatitis B reactivation ● thromboembolism prophylaxis based on risk factors |

| Dexamethasone (Pd) | ● relapsed/refractory MM, after at least 2 previous treatments, including lenalidomide and bortezomib and progression during the previous treatment | |||

| Daratumumab/dexametha-sone (Dara-Pd) | ● pats. with MM, who have already received 1 previous treatment with a proteasome inhibitor and lenalidomide and were refractory to lenalidomideor ● who have already received at least 2 previous treatments involving lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and who have demonstrated disease progression during or after the previous treatment |

|||

| Isatuximab/dexamethasone (Isa-Pd) | ● pats. mit relapsed/refractory MM, who have received at least 2 previous treatments, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and disease progression during the previous treatment | |||

| Elotuzumab/dexamethasone (Elo-Pd) | ● pats. mit relapsed/refractory MM, who have received at least 2 previous treatments, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and disease progression during the previous treatment | |||

| Proteasome inhibitors | ||||

| Bortezomib (V) | Monotherapy | ● progressive MM after at least 1 previous treatment and ASCT or not eligible for ASCT | ● polyneuropathy ● blood count changes and hematologic toxicity ● herpes zoster reactivation |

● subcutaneous administration ● German Joint Federal Committee, Annex VI to Section K of the Drug Guidelines, as of 08/2021: prescription of approved drugs for unapproved use (off-label use), Part A, XXXIII ● acyclovir for herpes zoster prophylaxis |

| Pegylated. liposomal doxorubicin | ● progressive MM after at least 1 previous treatment and ASCT or not eligible for ASCT | |||

| Dexamethasone (Vd) | ● progressive MM after at least 1 previous treatment and ASCT or not eligible for ASCT | |||

| Melphalan/prednisone (VMP) | ● untreated MM ● pats. not eligible for HD and ASCT |

|||

| Dexamethasone (VD) | ● untreated MM ● induction therapy ● pats. eligible for HD with ASCT |

|||

| Thalidomide/dexamethasone(VTD) | ● untreated MM ● induction therapy ● eligible for HD with ASCT |

|||

| Cyclophosphamide/dexame-thasone (VCD) | ● induction therapy ● newly diagnosed MM ● the instructions for the application of the directive should be observed, including ● use especially in pats. with peripheral polyneuropathy or an increased risk of developing peripheral polyneuropathy |

|||

| Daratumumab/melphalan/ prednisone (Dara-VMP) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM ● not eligible for ASCT |

|||

| Daratumumab/thalidomide/dexamethasone (Dara-VTd) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM ● not eligible for ASCT |

|||

| Daratumumab /dexamethasone (Dara-Vd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Panobinostat/dexamethasone (PAN-Vd) | ● pats. with relapsed/refractory MM, who have received at least 2 previous treatments, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory drug | |||

| Carfilzomib (K) | Daratumumab/dexametha-sone (Dara-Kd or KdD) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | ● hematologic toxicity ● thromboembolic event ● hypertension ● heart disease ● fatigue ● herpes-zoster reactivation ● renal failure ● heart damange (rare) ● polyneuropathy (rare) |

● acyclovir for herpes zoster prophylaxis ● venous thromboembolism prophylaxis recommended |

| Lenalidomide/dexamethasone (KRd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Dexamethasone (Kd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Isatuximab/dexamethasone (Isa-Kd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Ixazomib (Ixa) | Lenalidomide/dexamethasone (Ixa-Rd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | ● hematologic toxicity ● nausea ● skin reactions ● peripheral edema ● herpes zoster reactivation |

● oral administration ● to be taken at the latest 1 hr before or at the earliest 2 hrs after a meal ● venous thromboembolism prophylaxis recommended ● acyclovir for herpes zoster prophylaxis |

| Antibodies | ||||

| Daratumumab (Dara) IV | Lenalidomide/dexamethasone (Dara-Rd) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM, who are not eligible for ASCT ● after at least 1 previous treatment |

● infusion reactions (for example, breathing problems, chills, etc; primarily before the first administration) ● susceptibility to infections ● pancytopenia ● loss of appetite ● polyneuropathy ● headache ● hypertension ● diarrhea ● constipation ● nausea ● pancreatitis ● fatigue ● fever ● backache |

● long infusion time ● standard diagnostics prior to blood transfusions may be hindered and delayed ● risk of hepatitis B reactivation |

| Bortezomib, melphalan, dexamethasone (Dara-VMP) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM ● not eligible for ASCT |

|||

| Bortezomib/thalidomide/de-xamethasone (Dara-VTd) | ● pats. with newly diagnosed MM ● not eligible for ASCT |

|||

| Bortezomib/dexamethasone(Dara-Vd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Monotherapy | ● pats. with relapsed/refractory MM, who have already been treated with a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory drug and had disease progression during the previous treatment | |||

| Daratumumab (Dara) SC | in addition:Pomalidomide/dexamethasone (Dara-Pd) | ● pats. with MM, who have already received 1 previous treatment with a proteasome inhibitor and lenalidomide and were refractory to lenalidomideor ● who have already received at least 2 previous treatments containing lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor and have shown disease progression during or after the previous treatment |

● susceptibility to infections ● pancytopenia ● loss of appetite ● polyneuropathy ● headache ● hypertension ● diarrhea ● constipation ● nausea ● pancreatitis ● fatigue ● fever ● backache |

SC only |

| Isatuximab (Isa) | Pomalidomide/dexamethasone (Isa-Pd) | ● pats. with relapsed/refractory MM who have already received at least 2 previous treatments, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and had disease progression during the previous treatment | ● infusion-related reactions ● susceptibility to infections ● pancytopenia ● shortness of breath ● diarrhea ● nausea ● squamous cell carcinoma of the skin |

|

| Carfilzomib/dexamethasone (Isa-Kd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | |||

| Elotuzumab (Elo) | Lenalidomide/dexamethasone(Elo-Rd) | ● after at least 1 previous treatment | ● infusion-related reactions ● diarrhea ● herpes zoster infections ● pneumonia ● infections of the upper airways ● lymphopenia ● thromboembolic event ● liver toxicity |

● thromboembolism prophylaxis |

| Pomalidomide/dexamethasone (Elo-Pd) | ● pats. with relapsed/refractory MM who have received at least 2 previous treatments, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and had disease progression during the previous treatment | |||

| Other substances | ||||

| HDAC inhibitor | ||||

| Panobinostat | Bortezomib/dexamethasone (PAN-Vd) | ●pats. with relapsed/refractory MM who have received at least 2 previous treatments, including bortezomib and 1 immunomodulatory drug | ● pneumonia ● myelosuppression ● hypotension ● gastrointestinal symptoms, arrhythmia ● cardiac ischemia |

● oral administration |

| Antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) | ||||

| Belantamab mafodotin | Monotherapy | ● pats. with MM, at least 4 previous treatments and disease refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, 1 immunomodulator and 1 monoclonal anti-CD38 antibody, and disease progression during the previous treatment | ● pneumonia ● pancytopenia ● eye or corneal diseases ● nausea ● diarrhea ● pyrexia ● fatigue ● infusion-related reactions |

● opthalmological examinations, artificial tears |

| XPO1 inhibitor | ||||

| Selinexor | Dexamethasone | ● approved by EMA: at least 4 previous treatments, refractory to at least 2 proteasome inhibitors, 2 immunomodulators and 1 monoclonal anti-CD38 antibody, and had disease progression during the previous treatment | ● susceptibility to infections ● pancytopenia ● metabolic disorders ● insomnia ● confusion ● dizziness ● headache ● dysgeusia ● blurred vision ● nausea ● diarrhea ● constipation ● abdominal pain ● fatigue ● fever |

● no product information available in German yet |

| CAR-T | ||||

| Idecabtagen vicleucel | ● pats. with relapsed/refractory MM, who have received at least 3 previous treatments, including 1 immunmodulator, 1 proteasome inhibitor and 1 anti-CD38 antibody, and had shown disease progression during the previous treatment | ● susceptibility to infections ● pancytopenia ● cytokine release syndrome ● hypogammaglobulinemia ● metabolic disorders ● encephalopathy ● headache ● dizziness ● tachycardia ● hypertension ● hypotension ● shortness of breath ● cough ● nausea ● diarrhea ● constipation ● arthralgia ● fever ● fatigue ● asthenia ● edema ● chills |

● tocilizumab and emergency equipment available on standby in the event of cytokine release syndrome | |

| Cytostatic agents (alphabetic) | ||||

| Bendamustine | Prednisone | ● primary therapy for MM (Durie-Salmon stage II with progression or stage III), pats. > 65 years and not eligible for ASCT, who already present clinical neuropathy at the time of diagnosis which excludes treatment with thalidomide or bortezomib | ● myelosuppression ● infections ● nausea ● cardiac dysfunction ● skin reactions ● tumor lysis syndrome |

● risk of hepatitis B reactivation |

| Cyclophosphamide (C) | (Prednisone) | ● remission induction for plasmacytoma (also in combination with prednisone) | ● blood count changes ● hair loss at higher doses possible ● myelosuppression ● cystitis prophylaxis required (hydration + mesna at doses >400 mg/m 2 /d) ● mucositis ● alopecia |

● available in both IV and oral drug forms ● German Joint Federal Committee, Annex VI to Section K of the Drug Guidelines, as of 08/2021: prescription of approved drugs for unapproved use (off-label use), Part A, XXXIII. |

| Bortezomib/dexamethasone (VCD) | ● induction therapy, newly diagnosed MM ● the instructions for the application of the directive should be observed, including: use especially in pats. with peripheral polyneuropathy or an increased risk of developing peripheral polyneuropathy |

|||

| Doxorubicin | ● advanced MM | ● cardiotoxicity (maximum cummulative dose 400–550 mg/m2) ● myelosuppression ● extravasation risk |

||

| Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin | Bortezomib | ● progressive MM in pats. after at least 1 previous treatment and who have already undergone bone marrow transplantation or are not eligible for it | ● cardiomyopathia ● myelosuppression ● infusion reactions ● hand-foot skin reaction ● gastrointestinal toxicity |

|

| Melphalan | In combination with prednisone/ prednisolone or other anti-myeloma therapeutic agents or as high-dose monotherapy for conditioning before ASCT | ● multiple myeloma (plasmacytoma); see product information | ● blood count changes ● hair loss possible at higher doses ● myelosuppression ● extravasation risk ● urea ↑ ● mucositis ● alopecia |

● available in both IV and oral drug forms |

* Note: as of 09/2021; the current, approved indications for use, the dosages of the respective drugs in the various combination therapies, the number of cycles and any necessary dose reductions must be checked against the latest product information before use.

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; EMA, European Medicines Agency; HD, high-dose chemotherapy; MM, multiple myeloma; pats., patients

A detailed description of the methods, including how conflicts of interest were managed, can be found in the guideline report (5).

Results

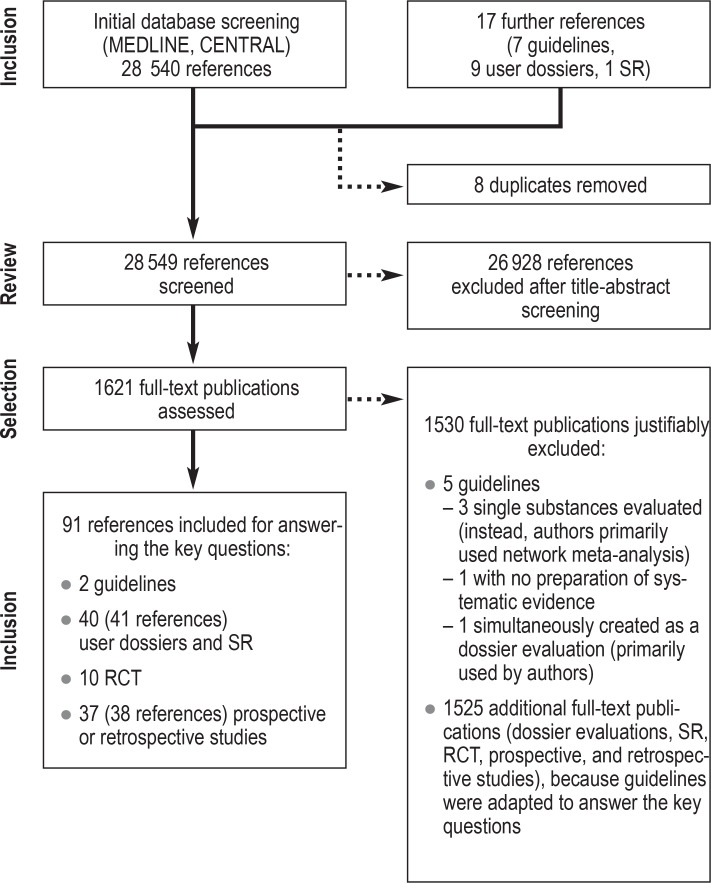

The literature review identified 28 557 publications of potential relevance. Of these, two guidelines, 40 (41 references) systematic reviews with meta-analysis and dossier evaluations, ten randomized controlled trials, and 37 (38 references) prospective or retrospective studies were used to answer the key questions. The process of literature identification is presented graphically in eFigure 3. Since no adequate studies were identified for many of the key questions, the recommendations were based on expert consensus in this case.

eFigure 3.

Presentation of the literature search

RCT, randomized controlled study; SR, systematic review

The long version, short version, and guideline report can be accessed on the AWMF and GGPO websites and are available digitally via the GGPO guideline app (6– 8). A patient guideline is currently in progress.

Diagnostics and staging classification

Staging classification and prognostic assessment

If a monoclonal paraprotein is detected in serum or urine, then MM and other hematologic diseases should first be excluded (expert consensus), see Box. MGUS is characterized by the presence of a paraprotein without evidence of hematologic disease. MM is defined by the detection of at least 10% atypical clonal plasma cells on bone marrow examination. Differentiation of MM from related plasma cell neoplasms should be based on prognostic and therapeutic differences (expert consensus). The International Staging System (ISS) of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) is recommended for staging, while the revised ISS (R-ISS) should be used when genetic findings are available (expert consensus).

Molecular cytogenetics

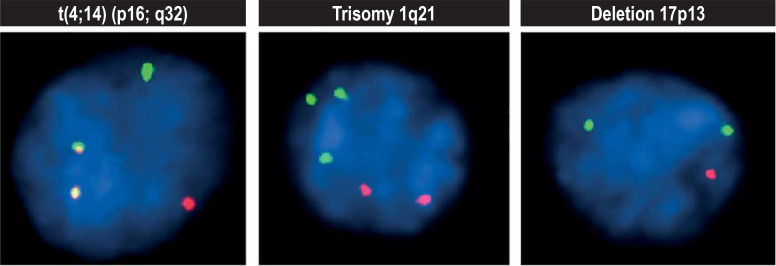

Multiple myeloma has many genetic alterations (10) which distinguish it from other lymphoid neoplasms with monoclonal gammopathy and allow for risk stratification (11– 13). With MM, prior to commencing treatment, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) should be performed on the CD138-positive plasma cells of the bone marrow aspirate, enriched by magnetic cell sorting to detect high-risk chromosomal alterations (1q gains, t(4;14) translocations or FGFR3-IGH fusion, t (14;16) or IGH-MAF fusion, and t (14;20) or IGH-MAFB fusion, 17p-deletion [TP53 gene]) (expert consensus) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

High-risk chromosomal abnormalities in multiple myeloma: red and green fluorescent gene probes can detect chromosomal fusions (superimposition of red and green as a yellow signal at t[4;14]), gains (third green signal at trisomy 1q21), or losses (only one red signal at deletion 17p13).

Establishing the diagnosis

If MM is suspected, total protein quantification, protein electrophoresis with M gradient determination, immunofixation, and free light chain analysis in serum are required in addition to patient history and physical examination (expert consensus). The M gradient represents a pathological additional spike on serum electrophoresis, usually in the gamma globulin fraction region. Further laboratory tests should reveal significant organ dysfunction (for example, renal failure) and myeloma-associated features (for example, degree of antibody deficiency).

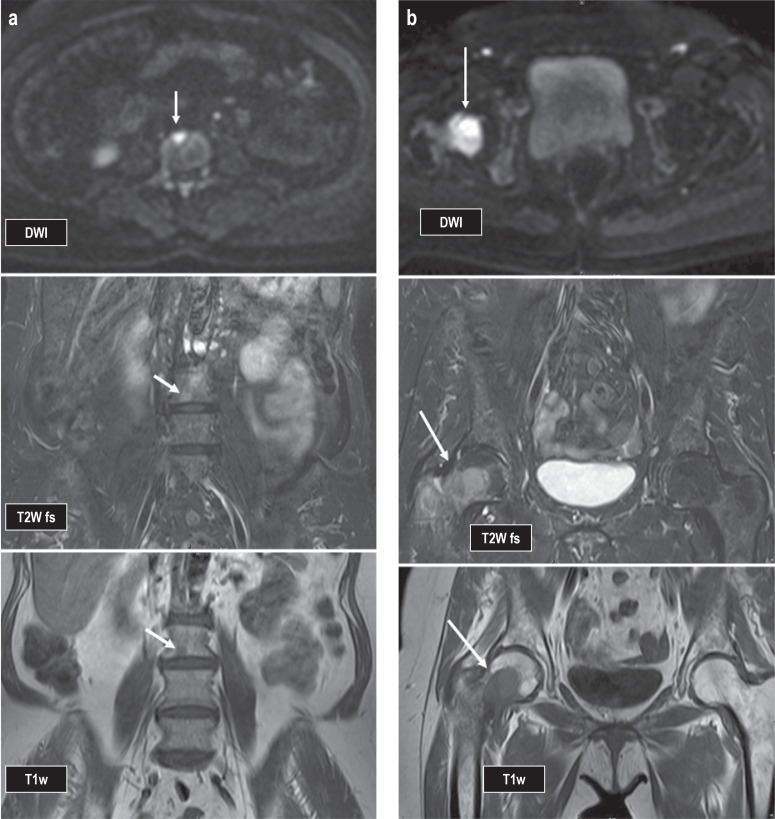

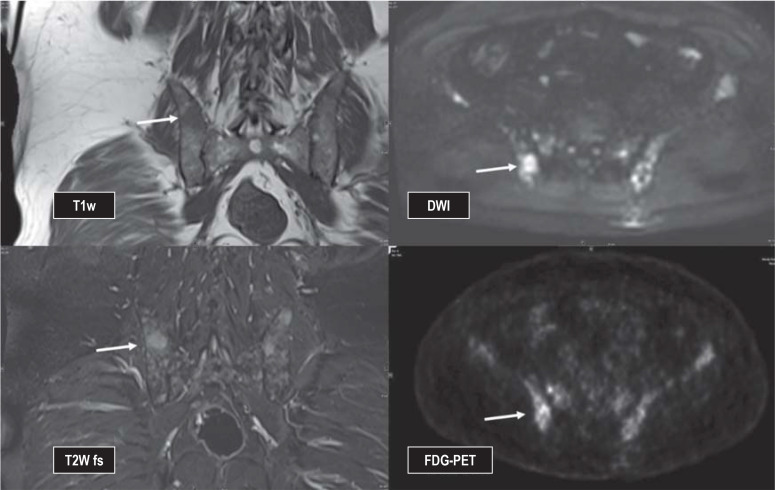

In addition, a bone marrow biopsy should also be obtained (expert consensus). Organ biopsies other than bone marrow are only performed if organ involvement or extramedullary myeloma manifestations are suspected. Full-body computed tomography (CT) should be obtained if MM is suspected and in patients with non-IgM MGUS (IgM, immunoglobulin-M) who have both a serum M protein >1.5 g/dL and an abnormal light chain ratio (expert consensus). In patients with solitary plasmacytoma, whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET/CT) should be used to identify additional MM manifestations (recommendation grade: A) (Figures 2a and b). However, whole-body MRI and PET examinations are not included in the list of services covered by the statutory health insurance funds; reimbursement is therefore not guaranteed.

Figure 2.

Female patient, 65 years old at time of imaging studies; progression from SMM to MM. First appearance of two focal lesions on MRI (see arrows): a) in the third lumbar vertebral body (L3) measuring 7 × 8 mm and b) in the right femoral neck measuring 3.3 × 2.5 cm; this finding in combination with bone destruction (cortical breach is already visible on MRI).

DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; MM, multiple myeloma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SMM, smoldering multiple myeloma; T1w, T1-weighted image; T2w FS, T2-weighted image with fat suppression

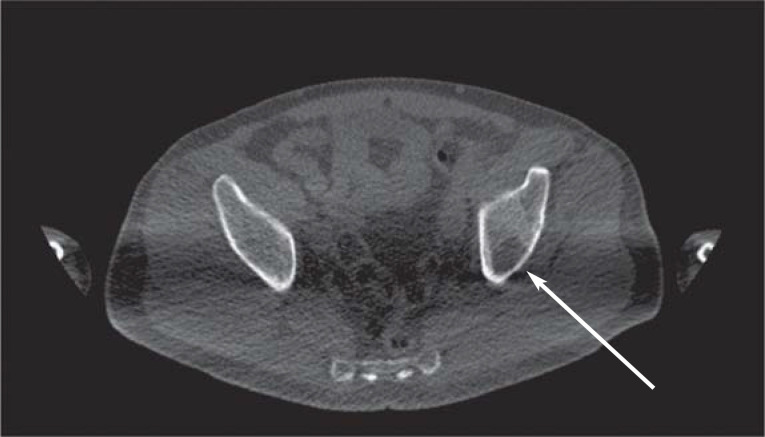

The SLiM-CRAB criteria of the IMWG define MM requiring treatment. In addition to plasma cell infiltration of at least 10%, these criteria include evidence of MM-related end organ damage (hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions) or one or more myeloma-defining biomarker(s) (i.e., clonal plasma cell content in bone marrow ≥60%, serum free light chain ratio [affected/unaffected] ≥100, or >1 focal lesion >5 mm on whole-body MRI imaging). Involvement of focal lesions includes at least one well-circumscribed destruction of mineralized bone typical of myeloma or at least two foci typical of myeloma >5 mm on MRI or CT, or at least one lesion with concomitant osteolysis on PET-CT (efigure 1).

eFigure 1.

First-time appearance of osteolysis in the left iliac bone (arrow) on native computed tomography

A CT scan should be obtained to detect skeletal damage. Cushioning the arms may result in better CT image quality by avoiding beam hardening artifacts (expert consensus). Conventional skeletal survey radiographs should be avoided (expert consensus) and performed only when clinically indicated. Supplemental whole-body MRI or PET-CT may be performed to assess bone marrow involvement and possible extramedullary foci (expert consensus). If whole-body CT fails to show osteolysis, whole-body MRI, or alternatively MRI of the spine and pelvis, should be performed (expert consensus) (efigure 2). PET/CT may be obtained instead of whole-body MRI (expert consensus). The relevance of both modalities for assessing response or progression is currently being further assessed in studies.

eFigure 2.

Male patient, 59 years of age, initial diagnosis of multiple myeloma, staging before initiation of therapy, has multiple focal lesions, for example in the right dorsal iliac bone, visualized on MRI as well as on PET (arrow)

DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FDG-PET, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

T1w, T1-weighted image; T2w FS, T2-weighted image with fat suppression

Initiating therapy

The SLiM-CRAB criteria of the IMWG serve as the basis for the initiation of therapy (13). In addition to the SLiM-CRAB criteria, the presence of other symptoms may necessitate therapy (for example, recurrent infections, hyperviscosity syndrome, tumor pain, paraneoplastic polyneuropathy). MGUS with organ dysfunction requires a biopsy of the affected organ to be performed (expert consensus) and for example in case of renal involvment should be treated as monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS), (expert consensus). Treatment should also be initiated in the presence of AL amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease (LCDD) (expert consensus).

In all patients with MM, biological age should be used instead of chronological age when making treatment decisions (expert consensus). For this purpose, the patient’s general condition, comorbidities, physical activity, and social integration should be taken into account – for example, by using the Karnofsky Index, according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status, or by using myeloma-validated comorbidity scores, such as the R-MCI (Freiburger Revised Myeloma Comorbidity Index) or the IMWG-FI (International Myeloma Working Group Frailty Index). Estimation of acceptable treatment intensity should also be reassessed after initiating therapy (expert consensus). The selection of options and intensity for systemic therapy has been well described in various previous resources (14– 16). Systemic therapy is aimed at suppressing myeloma activity over as long a period as possible and is therefore usually continued as maintenance therapy until it becomes ineffective or intolerable—either as a constant combination of different drugs or as a sequence of combinations, for example induction, consolidation, maintenance. According to data from the Robert Koch Institute, the five-year relative survival rate in 2018 was 54% for females and 52% for males (2).

Selecting appropriate therapy

There is an ever-increasing choice of agents and modalities available for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Due to the large number of possible combinations, it is becoming increasingly difficult to provide evidence-based recommendations, especially since direct comparative studies are often lacking. Therefore, the following constitutes recommendations for a therapeutic strategy.

High-dose therapy and stem cell transplantation

Patients eligible for high-dose therapy should initially receive combination therapy to reduce disease activity (induction therapy) (recommendation grade: A) (overall survival after induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation as compared with drug therapy: hazard ratio [HR]: 0.76; 95% confidence interval: [0.42; 1.36]; progression-free survival [PFS]: HR 0.55 [0.41; 0.74]); result of a meta-analysis of four trials [2421 patients]) (17). This recommendation is based on the clinically relevant and statistically significant improvement in PFS. Given the very good treatment options for relapse, there is no statistically significant advantage in overall survival. General health should be used to assess transplant eligibility rather than chronological age (recommendation grade: B). This assessment should be reviewed on completion of induction treatment (expert consensus). Patients should receive a triple or quadruple combination as induction therapy (recommendation grade: A) (overall survival of a triple combination as compared with a quadruple combination: HR 1.04 [0.91; 1.19]; result of a meta-analysis of five trials [1765 patients]; overall survival of a quadruple combination as compared with a triple combination: HR 0.43 [0.23; 0.80], result of a randomized controlled trial [1085 patients]) (18, 19). As yet, there is insufficient evidence to support any particular regimen or specific number of cycles, as not all combinations have been comparatively assessed.

Melphalan should be avoided during induction therapy in patients in whom high-dose therapy cannot be ruled out (expert consensus). Prolonged induction therapy prior to harvesting of stem cells (>4–6 cycles) should also be avoided, especially if it involves lenalidomide or other immunomodulatory agents (expert consensus).

Drug therapy

All patients should be offered maintenance therapy with lenalidomide after high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (recommendation grade: A) (overall survival after autologous stem cell transplantation with lenalidomide maintenance therapy as compared with placebo maintenance or no maintenance therapy: HR 0.75 [0.63; 0.90]; result of a meta-analysis of three trials [1208 patients]) (20). Maintenance therapy should last at least two years and should be continued until disease progression (recommendation grade: A).

Non-transplant patients should receive continuous therapy (recommendation grade: A) and should be treated initially with a triple or quadruple combination in the absence of serious comorbidities (recommendation grade: B). All tested combinations have demonstrated a clinically relevant and statistically significant advantage, not only with regard to PFS but also to overall survival. A list of prospective randomized treatment modalities is compiled in the Table, and an overview of the individual drugs approved for MM is provided in the eTable. However, an optimal therapeutic regimen cannot be provided due to the lack of comparative studies. The US American Society of Cancer (ASCO) guideline, the joint European Haematology Association (EHA), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guideline, and the IMWG guideline provide compilations on the manifold treatment options (16, 21, 22).

Table. Randomized comparative studies on the therapy of multiple myeloma (in alphabetical order)*1.

| Median PFS | Median OS | SAE | Response | CR | |||||||||||

| Study | Study register | Inter- vention | Comparison | Inter- vention | Comparison | HR for PFS[95% CI] | Inter- vention | Comparison | HR for OS[95% CI] | Inter- vention | Comparison | Inter- vention | Comparison | Inter- vention | Comparison |

| First line, transplant-ineligible | |||||||||||||||

| ALCYONE (e1, e2) | NCT02195479 | Dara VMP | VMP | 36 | 19 | 0.42 [0.34; 0.51] | NR | NR | 0.60 [0.46; 0.80] | 42% | 33% | 91% | 74% | 43% | 24% |

| MAIA (e3, e4) | NCT02252172 | Dara Rd | Rd | NR | 32 | 0.56 [0.43; 0.73] | NR | NR | 0.68 [0.53; 0.86] | 63% | 63% | 80% | 66% | 48% | 25% |

| SWOG S0777 (e5) | NCT00644228 | VRd | Rd | 43 | 30 | 0.71 [0.56; 0.91] | 75 | 64 | 0.71 [0.52; 0.96] | 52 % | 47% | 82% | 72% | 16% | 8% |

| Relapse | |||||||||||||||

| APOLLO (e6) | NCT03180736 | Dara Pd | Pd | 12 | 7 | 0.63 [0.47; 0.85] | NR | NR | − | 50 % | 39% | 69% | 46% | 25% | 4% |

| ASPIRE (e7) | NCT01080391 | KRd | Kd | 26 | 17 | 0.66 [0.55; 0.78] | 48 | 40 | 0.79 [0.67; 0.95] | 65% | 57% | 87% | 67% | 32% | 9% |

| BOSTON (e8) | NCT03110562 | SVd*2 | Vd | 14 | 10 | 0.70 [0.53; 0.93] | NR | 25 | 0.84 [0.57; 1.23] | 24% | 30% | 76% | 62% | 17% | 10% |

| CANDOR (e9) | NCT03158688 | Dara Kd | Kd | 29 | 15 | 0.59 [0.45; 0.78] | NR | NR | − | 56% | 46% | 84% | 73% | 33% | 13% |

| CASTOR (e10) | NCT02136134 | Dara Vd | Vd | 17 | 7 | 0.31 [0.24; 0.39] | NR | NR | − | 42% | 34% | 84% | 63% | 19% | 9% |

| ELOQUENT-2 (e11) | NCT01239797 | Elo Rd | Rd | 19 | 15 | 0.71 [0.59; 0.86] | 48 | 40 | 0.78 [0.63; 0.96] | 65% | 56% | 79% | 66% | 4% | 7% |

| ELOQUENT-3 (e12) | NCT02654132 | Elo Pd | Pd | 10 | 5 | 0.54 [0.34; 0.86] | NR | NR | − | 53% | 55% | 53% | 26% | 8% | 2% |

| ENDEAVOR (e13, e14) | NCT01568866 | Kd | Vd | 19 | 9 | 0.53 [0.44; 0.65] | 48 | 39 | 0.76 [0.63; 0.92] | 59% | 40% | 77% | 63% | 13% | 6% |

| ICARIA-MM (e15) | NCT02990338 | Isa Pd | Pd | 12 | 7 | 0.60 [0.44; 0.81] | NR | NR | 0.69 [0.46; 1.0] | 62% | 54% | 60% | 35% | 5% | 1% |

| IKEMA (e16) | NCT03275285 | Isa Kd | Kd | NR | 19 | 0.53 [0.32; 0.89] | NR | NR | − | 59% | 57% | 87% | 83% | 40% | 28% |

| OPTIMISMM (e17) | NCT01734928 | PVd | Vd | 11 | 7 | 0.61 [0.49; 0.77] | NR | NR | 0.98 [0.73; 1.32] | 61% | 43% | 82% | 50% | 16% | 4% |

| POLLUX (e18) | NCT02076009 | Dara Rd | Rd | 45 | 18 | 0.44 [0.35; 0.55] | NR | NR | − | 49% | 42% | 93% | 76% | 57% | 23% |

| TOURMALINE-1 (e19, e20) | NCT01564537 | Ixa Rd | Rd | 21 | 15 | 0.74 [0.59; 0.94] | 54 | 52 | 0.94 [0.78; 1.13] | 40% | 44% | 78% | 72% | 14% | 7% |

*1 This table is not part of the guideline but presents the underlying clinical results.

*2 Selinexor is currently approved only in combination with dexamethasone, but not in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone.

Approved treatment for recurrence without results from randomized comparative studies: belantamab mafodotin, idecabtagene vicleucel

Dara, daratumumab; d, dexamethasone; Elo, elotuzumab; Isa, isatuximab; Ixa, ixazomib; K, carfilzomib; M, melphalan; P, pomalidomide; R, lenalidomide; S, selinexor; V, bortezomib;

CR, complete response; HR, Hazard Ratio; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival in months; PFS, progression-free survival in months;

SAE, severe adverse events; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Radiotherapy

In cases of multiple involvement, radiotherapy should be used to treat osteolytic bone lesions to prevent local complications (for example, fractures) or to treat intractable pain resulting from osseous or non-osseous involvement (expert consensus). Radiotherapy can be administered simultaneously with systemic (maintenance) therapy, although this should be done in close consultation with a medical oncologist (expert consensus). Treatment of solitary plasmacytoma is by radiotherapy. This is achieved by applying a dose of between 40 and 50 Gy (recommendation grade: B). Treatment with a dose lower than 40 Gy should not be given because of the significantly lower local control rate (recommendation grade: A) (overall survival after radiotherapy with ≥40 Gy as compared with <40 Gy: HR: 0.62 [0.54; 0.72]; result of a retrospective analysis of 2816 patients) (23). Radiotherapy should also be given following initial surgical treatment (e.g. for a pathological fracture) (expert consensus).

Therapy response and therapy continuation Assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD)

Flow cytometry or genetic methods can be used to measure MRD in bone marrow. Studies have shown that MRD negativity resulted in significantly prolonged PFS (HR: 0.41 [0.36; 0.48]; 14 studies [1273 patients] included in meta-analysis) and overall survival (HR: 0.57 [0.46; 0.71]; 12 studies [1100 patients] included in meta-analysis) (statement) (20). However, there are no study results available to date evaluating MRD status as a basis for therapeutic decisions (MRD-guided treatment) (statement). Therefore, assessment of MRD status is reserved for clinical trials (recommendation grade: 0).

Consequences upon treatment response or in the event of an increase in disease activity

If progression is not otherwise suspected, MGUS with a high risk of progression, smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), or successfully treated solitary plasmacytoma without evidence of persistent or systemic plasmacytic disease should undergo annual whole-body MRI or whole-body CT combined with MRI of the spine and pelvis over a period of five years (expert consensus).

High-dose therapy should be given in patients with MM regardless of response during induction therapy (recommendation grade: B). Free light chain assay should be used to classify treatment response in hyposecretory myeloma, and analysis of clonal plasma cell content in bone marrow or alternatively by serial imaging using whole-body MRI or PET-CT in non-secretory myeloma (expert consensus). If therapy only produces stable disease, then a change in therapy should be considered (expert consensus). Furthermore, therapy should be recommenced or changed (expert consensus)

if new end-organ damage develops (according to CRAB criteria),

in the case of progressive extramedullary disease or high dynamics of biochemical parameters,

and in the case of disease progression during on-going therapy or early progression after the end of therapy.

If relapse occurs, therapy should be continued until progression, depending on initial response, tolerability, toxicity, and patient preference (recommendation grade: B). A variety of treatment options are available, with combinations of three substances being preferred over doublet combinations due to better efficacy (expert consensus). The Table lists tested and available combinations. Here, all triple combinations show improved PFS, and in some cases longer overall survival, although the studies are not comparable with each other due to different patient characteristics and differences in prior therapies.

Symptom control and follow-up rehabilitation

Patients with MM often suffer from bone pain secondary to skeletal involvement. Pain management should be provided according to the S3-consensus guidelines on palliative care, regardless of the disease stage (expert consensus) (24).

Antiresorptive agents (bisphosphonates or RANKL inhibitors [RANKL, Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand]) are used for bone manifestations to inhibit osteoclast activity. Substitution therapy with vitamin D and calcium should be given during RANKL inhibitor therapy in the absence of hypercalcemia, whereas it may be given optionally during bisphosphonate therapy (expert consensus), because hypocalcemia usually remains asymptomatic during bisphosphonate therapy.

Physical exercise has long been a subject of critical debate in patients with MM. However, studies have shown that physical activity is safe and can both improve quality of life and reduce symptom severity. Results of a Cochrane review showed, among other things, less fatigue after aerobic exercise compared with no aerobic exercise (mean improvement of 0.31 points [0.13; 0.48] on a scale of -1 to 1; nine studies [826 patients included in meta-analysis]). Improvement in quality of life with aerobic exercise is possible, but the evidence here is uncertain (mean difference of 0.11 points [0.03; 0.24] on a scale of -1 to 1; eight studies [1259 patients included in meta-analysis]) (25).

Therefore, after completion of myeloma-specific therapy, follow-up rehabilitation should be offered to all patients capable of undergoing rehabilitation (expert consensus). Physical exercise is well tolerated by patients, even in the acute treatment phase and even under high-dose therapy (26– 28). Adjusted physical training should be offered to patients early (recommendation grade: B). The aim is to improve the quality of life of those affected and to help them regain an active and self-determined lifestyle.

Discussion

The S3-consensus guideline provides both evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations for the diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up of patients with MM and its specific manifestations, especially for care related to systemic therapy. The rapid further development of treatment options and the expected new comparative studies will require ongoing adaptation in the sense of a living guideline. Findings from key publications that modify recommendations should be integrated in a timely manner through annual update checks.

BOX. WHO classification of plasma cell neoplasms (9).

Non-IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) (IgM, immunoglobulin M) (precancerous condition)

-

Plasma cell myeloma

asymptomatic (smoldering) myeloma

non-secretory myeloma

plasma cell leukemia

-

Plasmocytoma

solitary plasmacytoma of bone

extraosseous (extramedullary) plasmacytoma

-

Immunoglobulin deposition diseases

primary amyloidosis

systemic light- and heavy-chain deposition diseases

-

Plasma cell neoplasms with associated paraneoplastic syndrome

polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy and skin changes (POEMS syndrome)

telangiectasias, erythrocytosis, monoclonal gammopathy, paranephritic abscess, intrapulmonary shunting (TEMPI syndrome)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. sc. hum. Anna Jauch, Institute of Human Genetics, Heidelberg University Hospital, and Prof. Stefan Delorme MD, German Cancer Research Center Heidelberg, Research Unit Imaging and Radiation Oncology, for providing us with the figures used.

Translated from the original German by Dr. Grahame Larkin, MD

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Einsele has received consultancy fees and fees for lecture activities from the companies Janssen, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis and Takeda and serves as a scientific advisor to these companies. He received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi.

Prof. Goldschmidt has received consultancy fees from the companies Adaptive Biotechnology, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Jannsen, Sanofi and Takeda. He has received payment for authorship from the companies Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis and Sanofi. He received research funding from the companies Novartis, MorphoSys, Glycomimetics, HD Pharma, Amgen, Takeda IQVIA, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline and OIS.

Prof. Scheid has received consultancy fees from the University Hospital Cologne Management and from the companies Novartis, Amgen, Janssen, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Takeda. He received fees for lecture activities from the companies Novartis, Amgen, Janssen, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Takeda. He has received study support (third-party funds) for carrying out commissioned studies for the companies Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Pfizer and Amgen. He received research funding from the companies Novartis, Takeda and Janssen.

Prof. Engelhardt has received consultancy fees and fees for lecture activities from the companies Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen. He received research funding from the companies Janssen, Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

As with many other professional journals, clinical guidelines in Deutsches Ärzteblatt are not subject to the peer review process, as S3 guidelines are texts that have been assessed and discussed by experts (peers) and already enjoy a broad consensus.

References

- 1.Kazandjian D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: a unique malignancy. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:676–681. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A, et al. Global burden of multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1221–1227. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RKI. Vol. 13. Berlin: 2021. Multiples Myelom. Krebs in Deutschland für 2017/2018. Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten und Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e. V; pp. 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, AWMF) Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge für Patienten mit monoklonaler Gammopathie unklarer Signifikanz (MGUS) oder Multiplem Myelom. 2022; Leitlinienreport 1.01, AWMF Registernummer: 018/035OL. www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Multiples_Myelom/LL_Multiples_Myelom_Leitlinienreport_1.0.pdf (last accessed on 23 February 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF) Onkologische S3-Leitlinien - jetzt als App. 2021. www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/app/ (last accessed on 23 February 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF) Onkologische Leitlinien. www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/ (last accessed on 23 February 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V. (AWMF) AWMF online. Das Portal der wissenschaftlichen Medizin. www.awmf.org/awmf-online-das-portal-der-wissenschaftlichen-medizin/ (last accessed on 19 January 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenna RW, Kyle RA, Kuehl WM, Harris NL, Coupland RW, Fend F. Plasma cell neoplasms In: WHO Classification of tumours of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri S, Stein H, editors. IARC. Lyon: 2017. pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avet-Loiseau H, Daviet A, Brigaudeau C, et al. Cytogenetic, interphase, and multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses in primary plasma cell leukemia: a study of 40 patients at diagnosis, on behalf of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and the Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Blood. 2001;97:822–825. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dingli D, Ailawadhi S, Bergsagel PL, et al. Therapy for relapsed multiple myeloma: guidelines from the mayo stratification for myeloma and risk-adapted therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:578–598. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paquin AR, Kumar SK, Buadi FK, et al. Overall survival of transplant eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: comparative effectiveness analysis of modern induction regimens on outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International myeloma working group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–e548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:470–476. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wörmann BDC, Einsele H, Goldschmidt H, et al. Multiples Myelom. Empfehlungen der Fachgesellschaft zur Diagnostik und Therapie hämatologischer und onkologischer Erkrankungen. Berlin: DGHO Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie e. V.: 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikhael J, Ismaila N, Cheung MC, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma: ASCO and CCO Joint Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1228–1263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhakal B, Szabo A, Chhabra S, et al. Autologous transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in the era of novel agent induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:343–350. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H, Zhou L, Peng L, Fu W, Zhang C, Hou J. Bortezomib-thalidomide-based regimens improved clinical outcomes without increasing toxicity as induction treatment for untreated multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of phase III randomized controlled trials. Leuk Res. 2014;38:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC, et al. Association of minimal residual disease with superior survival outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:28–35. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau P, Kumar SK, San Miguel J, et al. Treatment of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: recommendations from the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:e105–e118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goyal G, Bartley AC, Funni S, et al. Treatment approaches and outcomes in plasmacytomas: analysis using a national dataset. Leukemia. 2018;32:1414–1420. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0099-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onkologie L. Erweiterte S3-Leitlinie Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht-heilbaren Krebserkrankung. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knips L, Bergenthal N, Streckmann F, Monsef I, Elter T, Skoetz N. Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with haematological malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009075.pub3. CD009075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barthels FR, Smith NS, Sønderskov Gørløv J, et al. Optimized patient-trajectory for patients undergoing treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:750–758. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.999872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker ED, Larson J, Kujath A, Peace D, Rondelli D, Gaston L. Strength training following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:238–249. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181fb3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oechsle K, Aslan Z, Suesse Y, Jensen W, Bokemeyer C, de Wit M. Multimodal exercise training during myeloablative chemotherapy: a prospective randomized pilot trial. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1927-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Mateos MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:518–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Mateos MV, Cavo M, Blade J, et al. Overall survival with daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:132–141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2104–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1582–1596. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:519–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Boccadoro M, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma (APOLLO): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:801–812. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Siegel DS, Dimopoulos MA, Ludwig H, et al. Improvement in overall survival with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:728–734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Grosicki S, Simonova M, Spicka I, et al. Once-per-week selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus twice-per-week bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma (BOSTON): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Usmani SZ, Quach H, Mateos M-V, et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): updated outcomes from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:65–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Spencer A, Lentzsch S, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: updated analysis of CASTOR. Haematologica. 2018;103:2079–2087. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.194118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Dimopoulos MA, Lonial S, Betts KA, et al. Elotuzumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: extended 4-year follow-up and analysis of relative progression-free survival from the randomized ELOQUENT-2 trial. Cancer. 2018;124:4032–4043. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Dimopoulos MA, Dytfeld D, Grosicki S, et al. Elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1811–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Orlowski RZ, Moreau P, Niesvizky R, et al. Carfilzomib-dexamethasone versus bortezomib-dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: updated overall survival, safety, and subgroups. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19:522–530e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Attal M, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:2096–2107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Moreau P, Dimopoulos MA, Mikhael J, et al. Isatuximab, carfilzomib, and dexamethasone in relapsed multiple myeloma (IKEMA): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2361–2371. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Richardson PG, Oriol A, Beksac M, et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:781–794. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Bahlis NJ, Dimopoulos MA, White DJ, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: extended follow-up of POLLUX, a randomized, open-label, phase 3 study. Leukemia. 2020;34:1875–1884. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1621–1634. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Richardson PG, Kumar SK, Masszi T, et al. Final overall survival analysis of the TOURMALINE-MM1 phase III trial of ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2430–2442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]