Abstract

T cell receptors (TCRs) recognize peptide antigens bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (p/MHC) that are expressed on cell surfaces; while B cell-derived antibodies (Abs) recognize soluble or cell surface native antigens of various types (proteins, carbohydrates, etc.). Immune surveillance by T and B cells thus inspects almost all formats of antigens to mount adaptive immune responses against cancer cells, infectious organisms and other foreign insults, while maintaining tolerance to self-tissues. With contributions from environmental triggers, the development of autoimmune disease is thought to be due to the expression of MHC risk alleles by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) presenting self-antigen (autoantigen), breaking through self-tolerance and activating autoreactive T cells, which orchestrate downstream pathologic events. Investigating and treating autoimmune diseases have been challenging, both because of the intrinsic complexity of these diseases and the need for tools targeting T cell epitopes (autoantigen-MHC). Naturally occurring TCRs with relatively low (micromolar) affinities to p/MHC are suboptimal for autoantigen-MHC targeting, whereas the use of engineered TCRs and their derivatives (e.g., TCR multimers and TCR-engineered T cells) are limited by unpredictable cross-reactivity. As Abs generally have nanomolar affinity, recent advances in engineering TCR-like (TCRL) Abs promise advantages over their TCR counterparts for autoantigen-MHC targeting. Here, we compare the p/MHC binding by TCRs and TCRL Abs, review the strategies for generation of TCRL Abs, highlight their application for identification of autoantigen-presenting APCs, and discuss future directions and limitations of TCRL Abs as immunotherapy for autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: TCR-like antibodies, autoimmune diseases, autoantigen presentation, immunotherapy, antigen-specific therapy

Introduction

To date, over 80 autoimmune diseases have been described (1), ranging from organ-specific (e.g., pancreas-specific Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and thyroid gland-specific Grave’s disease) to systemic conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)). Curative approaches for autoimmunity are lacking. Despite diverse manifestations and autoantigen sources, these autoimmune reactions typically share stages of initiation, propagation, and for some, periods of clinical remission (2).

Although environmental factors are thought to be required as triggers for disease, predisposition to autoimmunity most often reflects inherited factors, with MHC (human leucocyte antigen (HLA) in humans) alleles conferring the highest risk (3, 4). Typically, class I (MHC-I or HLA-I in humans) genes encode proteins that present peptides from intracellular antigens to CD8+ T cells, and class II (MHC-II or HLA-II in humans) genes encode proteins that present extracellular/endosomal antigens to CD4+ T lymphocytes (5). A number of particular HLA-II (i.e., HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP) alleles have been identified as critical risk factors for particular autoimmune diseases. For example, >90% celiac patients carry HLA-DQA1*05:01/HLA-DQB1*02:01 (6, 7), and >95% narcoleptic patients carry HLA-DQB1*06:02 (8, 9). In addition, the HLA-DRB1*04:01/*04:04 genotypes are risk alleles (odds ratios are ∼4.14 and ∼3.17, respectively) for RA (10) and the HLA-DRB1*15:01-DRB5*01:01 haplotype (up to 60% among Caucasians) is linked to multiple sclerosis (MS) (11). How these polymorphic MHC proteins interact with autoantigens and how autoantigen-MHC presenting APCs interact with autoreactive T cells are central questions in the field.

HLA-II+ APCs generate peptide/HLA-II (p/HLA-II) complexes (12, 13) that interact with cognate TCRs on CD4+ T cells, which orchestrate downstream autoimmune reactions (9, 14–16). Therefore, targeting autoantigen-HLA-II complexes on the APC surface with soluble TCR or TCRL reagents enables a specific way to investigate the initiation and propagation of autoimmunity. Here, we review current approaches and future directions for generating and using TCRL (also known as TCR mimic) Abs as research tools and potential therapeutics for autoimmune diseases.

Comparisons of TCRL Abs with TCRs

Abs share many similarities with TCRs in terms of diversity of the receptor repertoire and specificity for antigen recognition (17, 18). Abs, especially monoclonal Abs (mAbs) are widely used in research, diagnoses and therapies as specific immune-targeting agents (19), whereas TCRs have not been widely used (20). This is in large part due to the intrinsic difference in their antigen binding affinities. TCRs have micromolar affinities for cognate p/MHCs (21), whereas Abs have nanomolar affinities and interact with their specific antigens with >100x higher binding energies (22).

Each TCR contains two polypeptide chains: α and β, whereas each Ab consists of two heavy (H) and two light (L) chains. An Ab has two identical antigen-binding fragments (Fab, an H/L dimer) and a crystallizable fragment (Fc, from the H chain) that links the two Fab arms (22), yielding increased avidity for antigen. The Fab H/L heterodimer, like the TCR α/β heterodimer, uses two sets of complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) to directly contact the cognate antigen. The CDR regions are also referred to as the fragment variable (Fv) region. CDR3 of both Fabs and TCRs are hypervariable, with key amino acid residues governing antigen binding specificity. Residues within the germline-encoded CDR1 and CDR2 are less variable (17). Ab engineering usually focuses on CDRs of Fab or Fv heavy and/or light chains. To modify both chains using one gene cassette, a covalent link between the heavy and light chain fragments can be used, yielding single-chain Fv (scFv) for example.

As natural p/MHC receptors, TCRs have scientific, diagnostic and therapeutic potential, particularly if used as tetramers or higher order multimers to increase avidity (23), or if engineered to improve target affinity or avidity (23–25). Affinity improved and/or multimeric TCRs and TCR-engineered T cells have been used to target and clear tumor cells presenting cancer-related p/MHC-I (26). However, these reagents have seldom been used for autoantigen-MHC-II targeting, likely for several reasons. First, compared to TCRs recognizing foreign or neoantigens, MHC-II/autoantigen-reactive TCRs tend to have lower affinity, which typically allows their escape from thymic negative selection but activity for autoimmune responses (27); this affinity window is a poor starting point for affinity improvement by TCR engineering. Second, improved TCR affinity is often compromised by unpredictable cross-reactivity (28, 29), causing off-target staining during auto-APC characterization.

To resolve these issues stemming from natural TCRs, investigators developed TCRL mAbs by combining the high affinity of a mAb with the capacity to recognize p/MHC complexes (20). Some TCRL mAbs target intracellular antigens presented by MHC-I on tumor cells and have been applied as immunotherapeutics for cancers (30, 31). Crystallization studies have determined the structures of five p/MHC-I-specific TCRL mAbs in Fab formats binding to their p/MHC-I targets (32–35). Although CDR regions of all five TCRL Fab molecules interact with the peptide region of p/MHC-I complexes, only two (34) show the canonical docking geometry of TCRs with p/MHC (20). Thus, the TCR docking geometry that elicits TCR signaling (36) is not an absolute requirement for TCRL mAb development. Recently, the co-crystal structure of an MHC-II-restricted TCRL Fab bound by a gliadin peptide/HLA-DQ2.5 (DQA1*05:01/DQB1*02:01) complex has been determined (37). This Fab has picomolar affinity, adopts the canonical TCR docking geometry (38), and demonstrates desirable properties for p/MHC-II staining and specific T cell inhibition relevant to celiac disease (37).

Generation of TCRL mAbs targeting p/MHC-II complexes

Naturally occurring Abs rarely mimic TCR specificity for p/MHC antigen(s); therefore, the TCRL feature of an Ab is typically obtained through target-driven in vitro selection and/or Ab engineering. Advances in hybridoma technology (39), recombinant p/MHC synthesis (40), and binder selection via phage or yeast display (41, 42) have enabled protein engineering of TCRL mAb. As other reviews have summarized TCRL mAb generation (20, 30, 31), we focus on the available approaches relevant to TCRL mAbs specific for p/MHC-II.

Initially, mice or rats immunized with p/MHC-II complexes expressed by cells or as soluble, recombinant proteins were used to produce a candidate B cell pool from which B cell hybridomas (immortal B cell lines producing candidate mAbs) were generated. Although TCRL specificity was possible (43, 44), most often, p/MHC-II-specific enrichment and screening were required to identify hybridomas producing TCRL mAbs. To date, >20 p/MHC-II-specific TCRL mAbs have been generated using this approach (20, 45, 46) and about half are relevant to autoimmune diseases (Table 1). However, challenges persist: 1) limited B cell clonal candidates with peptide specificities and more clones with monomorphic MHC specificity due to the framework differences of MHC-II alleles or MHC-II from different species (immunization of HLA-transgenic mice (49) may help enrich for peptide-specific responses, see discussion below); 2) low throughput of hybridoma production and labor-intensive screening for p/MHC-II binding; 3) non-human origin of the Ab itself, limiting their therapeutic use. Notably, a human B cell hybridoma expressing a TCRL mAb recognizing an HLA-A2-derived self-peptide bound to HLA-DR1 was generated using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (59).

Table 1.

TCRL mAbs targeting autoimmunity-related p/MHC-II complexes.

| mAb Clone | Species | Format | Method | Disease/Model | T cell antigen/MHC | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-7-1, B-18-7, C-34-72 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | MS/EAE model | MBP87-99/I-As | (47) |

| S.1.6 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | MS | MBP/DR7 | (48) |

| R.1.D12 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | MS | MBP/DRw11 | (48) |

| MK16 | Mouse | Fab | Phage display | MS | MBP218-231/DR15 | (49) |

| 12A | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | RA | HC gp-39263-275/DR4 | (50, 51) |

| 2E4, 1F11, 2C3, 3A3, 3H5 | Human | Fab | Phage display | MS | MOG35-55/DR15 | (52) |

| G3H8 | Human | Fab; reconstructed full-length Ab | Phage display | T1D | GAD65555-567/DR4 | (52, 53) |

| mAb287 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | T1D/NOD mice | Insulin B9-23/I-Ag7 | (54, 55) |

| FS1 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | Diabetes/NOD mice | p63/I-Ag7 | (46) |

| 106, 107 | Human | scFv; reconstructed full-length Ab | Phage display | Celiac Disease | glia-α1a/DQ2.5 | (56) |

| mAb757 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | T1D/NOD mice | Insulin B9-23/I-Ag7 | (57) |

| 3-5 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | T1D/NOD mice | 2.5HIP/I-Ag7 | (58) |

| 206, 3.C11 | Human | scFv; reconstructed full-length Ab | Phage Display | Celiac Disease | glia-α2/DQ2.5 | (37) |

| Selected other TCRL mAbs mentioned in this mini review | ||||||

| Y-Ae | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | Self-antigen | Eα/I-Ab | (43, 44) |

| UL-5A1 | Human | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma* | Self-antigen | HLA-A2105-117/DR1 | (59) |

| I-5 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | Self-antigen | CLIP/DR3 | (60) |

| D-4, G-32, and G-35 | Mouse | Full-length Ab | Hybridoma | Model antigen | MCC/I-Ek | (61, 62) |

| 3M4E5 and 3M4F4 | Human | Fab | Phage Display | Tumor antigen | NY-ESO-1/A*0201 | (34) |

| 13.4.1 | Mouse | Fab | Phage Display | Viral antigen | HA255-262/H-2Kk | (63) |

To avoid the limitations of hybridoma approaches, phage display has been applied by several groups to screen Ab libraries for p/HLA-II binders (49, 52, 56) (Table 1). A typical library contains 108-1011 phage particles, each displaying an Ab variant on the surface. Phage display is achieved by covalently fusing Ab fragments, such as Fab and scFv, with a phage coat protein through molecular cloning (41, 70). Screening the library for binders to p/HLA-II relies on a process called “panning” or more recently “biopanning” (70). This process includes multiple rounds of negative selection (e.g., against irrelevant p/HLA-II) and positive selection (e.g., against target p/HLA-II). Designing Ab libraries in phage allows selection from mouse (49) or human (37, 52, 53, 56) antibody sources. To enrich for peptide-specific Abs in the mouse endogenous repertoire prior to construction of a phage-Fab library, the Fugger group immunized HLA-DR15 (DRA*01:01/DRB1*15:01) transgenic mice using DR15 molecules in complex with a myelin basic protein (MBP) peptide, leveraging the inherent DR15 tolerance of the model to skew the Ab response towards specificity for the MBP peptide (49). HLA-transgenic animal immunization followed by screening yielded a series of TCRL reagent findings, including the MBP/DR15-restricted TCRL mAb MK16 as mentioned (49), invariant chain peptide/HLA-DR mAb in another study (60), and an MHC-I-restricted TCRL mAb in additional work (63). Human Fab or scFv libraries built and expressed in phage have been mostly from large naïve repertoires (37, 52, 53, 56), which likely harbor TCRL candidates, albeit rare. Using stringent phage panning strategies, the Reiter and the Løset groups isolated DR-restricted (52, 53) and DQ-restricted (37, 56) human TCRL mAbs, respectively (Table 1). As these human Fabs or scFvs were not raised or matured against the target p/HLA-II, their affinities were suboptimal. Reconstructing a full-size Ab using the TCRL Fab or scFv increased the binding strength (37, 53). However, further affinity maturation may be useful. Recently, Frick et al. suggested a strategy to improve binder affinity via multiple rounds of phage-Ab library optimization and selection (37).

Combining phage display with yeast display is particularly useful for developing high affinity TCRL mAbs (71). Since first developed (42), yeast display technology has evolved, allowing surface display of monomeric or dimeric protein scaffolds (72, 73). Thus, either scFv or Fab identified from a phage-Ab library can be affinity matured using the yeast platform. Advantages of yeast display include 1) eukaryotic gene transcription and protein expression machinery for appropriate Ab folding; and 2) quantitative flow cytometry-based screening, ensuring high throughput selection for high-affinity Abs (74, 75).

TCRL mAbs as research tools and therapeutics for autoimmune diseases

Characterization of autoantigen-presenting APCs using TCRL mAbs

Presentation of autoantigen by APCs, especially professional MHC-II+ APCs, such as dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages (MФs), and B cells, is critical for CD4+ T cell activation and differentiation into helper T effector (Teff) or suppressive T regulatory (Treg) cells during autoimmune responses. An imbalance of Teff and Treg functions upon autoantigen recognition is believed to drive the loss of tolerance, with subsequent autoreactive T cell responses and production of autoantibodies (2). Therefore, the study of MHC-II+ autoantigen presenting cells (auto-APCs) is fundamental for understanding disease pathogenesis and may lead to novel immunotherapies. Murine models allow direct evaluation of tissue-resident and circulating APC subsets and enable genetic modifications of these APCs to assess their autoreactive functions. For example, using an experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) mouse model, Lipski et al. analyzed disease-related infiltrating MФs and resident retinal microglia by tissue immunostaining and cytometry-based immunophenotyping of isolated cells (76). In another model, single-cell sequencing was used to characterize tissue-infiltrating APCs in autoimmune diabetes (77). However, discoveries in murine models are not easily transferable to human diseases (78, 79).

Auto-APC identification using human samples is a preferred approach for clinical relevance. Early studies with human samples focused on APC enumeration in PBMC and biopsies. Increased frequency of circulating DCs was implicated in regulation of antigen presentation by islet cells and activation of autoreactive CD4+ T cells (80, 81). Recently, a novel approach was developed using PBMC to identify autoantigen-specific memory B cells, which are potent MHC-II+ APC (82). Therapeutic strategies focusing broadly on APC function have been developed, such as B cell depletion in SLE (83) and tolerogenic DC adoptive therapy (84). However, the key to the optimization of APC-directed immunotherapy is identification of autoantigen specificity.

Due to their high affinity and the ease with which they can be further engineered, TCRL mAbs have gradually replaced TCR-derived reagents in research and therapeutic development for autoimmunity. TCRL MK16, described above, identified microglia/MФs rather than astrocytes as the predominant auto-APCs in MS lesions (49). Human cartilage glycoprotein (HC gp-39, residues 263-275) represents a candidate T cell autoantigen in RA and can be presented by the RA susceptibility allele, HLA-DR4 (DRA*01:01/DRB1*04:01) (50, 85). TCRL mAb 12A specific for gp-39 (263-275)/DR4 identified autoantigen-presenting DCs in synovial tissue of DR4+ patients, indicating local presentation of gp-39 in inflamed joints (50, 51). Recently reported are several TCRL mAbs, specific for different gluten-derived peptide epitopes in complex with the celiac disease risk allele, HLA-DQ2.5. These complexes are known to be recognized by CD4+ T cells that drive disease (16, 38). The TCRL mAbs identified plasma cells, an unexpected APC, as the most abundant cell type presenting gluten peptides in gut biopsies from celiac patients (37, 56).

Although murine models cannot directly identify auto-APCs that function in human diseases, applying TCRL mAbs in these models may shed mechanistic light on disease pathology. For example, with specificity for a model antigen, moth cytochrome c-derived peptide (MCC, residues 95-103) bound by mouse MHC-II I-Ek, TCRL mAb determined that a minimum of 200–400 p/MHC-II complexes per APC was necessary for T-cell stimulation (61). This number is at least an order of magnitude higher than the minimum requirement of p/MHC-I complexes for licensing cytolytic activity of human CD8+ T cells (86, 87).

Therapeutic potential of TCRL mAbs in autoimmune diseases

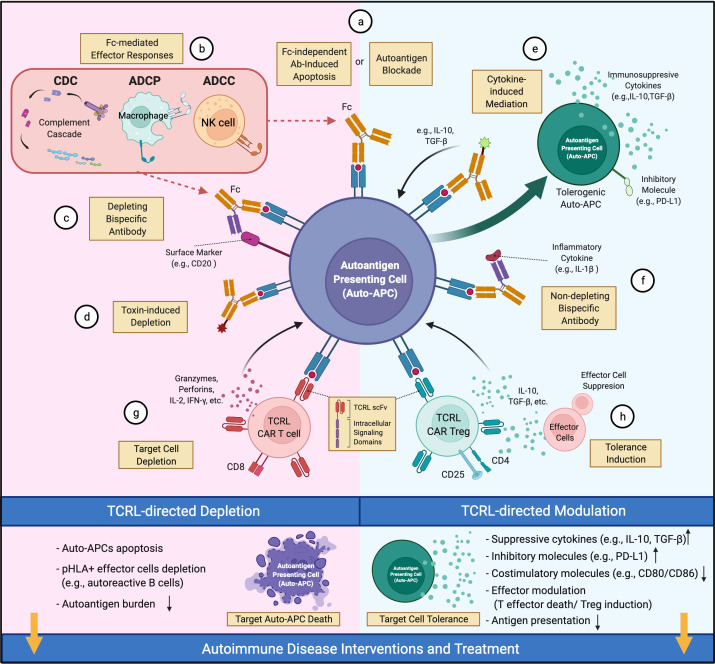

TCRL mAbs have not been intensively investigated as therapeutics for autoimmune diseases, although their pre-clinical examination in cancers (30, 31) suggests therapeutic potential. In cancer, TCRL mAbs can target intracellular tumor antigens presented by cell surface MHC-I molecules, broadening the original oncoantigen spectrum targeted by Ab-based therapy. However, a limitation of TCRL mAb in this setting is low TCRL Ab coverage per cell due to MHC-I downregulation on tumors (30). In contrast, MHC-II is typically up-regulated on auto-APCs in autoimmunity. Further, the tight linkage of particular autoimmune diseases with particular MHC-II alleles (3) provides defined allelic targets for TCRL mAbs. Although depletion of pathology-driving cells, as in cancer therapy, is a therapeutic option in autoimmunity, TCRL mAb therapy typically aims to reestablish healthy immune balance among cells like CD4+ Teff and Treg cells by non-depleting mechanisms (Figure 1). Here, we propose a few options for future TCRL autoimmune therapeutics, based on advances in TCRL mAb cancer therapies (30, 31) and Ab therapies for autoimmune diseases (19, 88).

Figure 1.

Therapeutic potential of TCRL mAbs in autoimmune diseases. TCRL mAbs specific for autoantigen/HLA complexes can elicit therapeutic effects via depleting (pink) or non-depleting (cyan) mechanisms. (A) TCRL mAbs either block autoantigen presentation or induce apoptosis of target cells. (B) TCRL mAbs induce Fc-mediated cytotoxicity through various effector mechanisms. (C, F) Bispecific antibodies targeting autoantigen/HLA complexes and either a surface marker of target cells or a pathogenic-related cytokine; (D) TCRL mAb–toxin conjugates induce auto-APC depletion by payload effector molecules, including cytokines, toxins or radioactive substances. (E) TCLR mAb-cytokine conjugates guide the delivery of immunomodulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) to auto-APCs for tolerance induction. (G) TCRL scFv fragments are reformatted into CARs for auto-APC targeting and depletion. (H) CD4+CD25+ TCRL CAR Treg cells suppress Teff function and induce tolerance. (This figure was created with BioRender.com).

Antibody treatment can induce target cell apoptosis (89) or (via Ab Fc region) lead to antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) (88, 90) (Figures 1A, B). For example, anti-CD20 mAbs, FDA-approved for RA and primary progressive MS (91, 92), appear to work by depletion of CD20+ B cells, including those that present autoantigen to T cells and give rise to autoantibody-producing plasma cells. However, unclear long-term benefits and side effects (e.g., lack of vaccine Ab response) of broad B cell elimination are concerns (88). Alternatively, one may consider engineering a bispecific Ab (BsAb), coupling specificity of anti-CD20 and anti-autoantigen p/MHC for targeted depletion of pathology-related B cells (Figure 1C). In NOD mice, an autoimmune diabetes model, TCRL mAb alone were reported to delay diabetes onset, likely due to selective deletion of auto-APCs (54, 55); detailed mechanism and systemic immune impact await further investigation.

Non-depleting TCRL mAbs, for example those with low FcR binding (93, 94), provide additional avenues for therapeutic interventions. TCRL mAbs can limit autoantigen-MHC accessibility and reduce activation of cognate T cells (Figure 1A). This has long been the rationale for evaluating TCRL mAb specificity and functionality in vitro or in mouse models (37, 49, 50, 53, 54). Additionally, autoimmune modulators conjugated to or coupled with TCRL mAbs could facilitate modulator delivery to autoantigen-MHC-II-enriched sites of disease. Such modulators include toxins (Figure 1D), immunoregulatory cytokines, and antibodies that neutralize effector molecules or regulate effector cell activity (88). Cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β that induce tolerogenic DC (95) with therapeutic efficacy (84) might reestablish tolerance at sites harboring auto-APCs (Figure 1E). Coupling TCRL mAb to FDA-approved antibodies that target inflammatory cytokines, as available for TNF, IL-6 and IL-1β, could localize their immunosuppressive effect to the sites of pathology (Figure 1F). TCRL mAbs could also be used in a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) format for constructing CAR T cells (Figure 1G). In diabetic NOD mice, CAR T cells expressing an insulin peptide/MHC-II TCRL mAb modulated autoimmunity (54, 55). In addition, re-directing Treg cells to the autoimmune milieu was shown to suppress autoreactive Teff cells in several models (96). Thus, it may be fruitful to introduce TCRL CARs into Treg cells for autoantigen-MHC directed Treg cell activity (Figure 1H).

Potential side effects of TCRL mAb therapy targeting autoantigen-MHC complexes

For TCRL mAbs that are on-target (specific for autoantigen-MHC) and on-tissue (targeting autoimmune lesion), their primary actions will be to deplete auto-APCs and/or to modulate the CD4+ T cell-mediated immune responses (Figure 1). However, adverse effects may arise after target auto-APC depletion or following immunomodulation. A potential concern with cell-depleting TCRL mAbs is autoantigen release from apoptotic auto-APCs, which may propagate autoimmunity (2). On-target but off-tissue or off-target binding by TCRL mAbs raises other risks, such as unpredictable cross-reactive interaction between these Abs and highly homologous HLA-II allelic proteins or mimetic self-peptides. For example, unexpected cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced TCR reagents targeting cancer-related MAGE A3/HLA-A*01 complex was reported to result in fetal cardiotoxicity (29). Regardless of target specificity, immune activation or suppression subsequent to TCRL mAb administration may lead to unpredictable toxicities, such as new autoimmune reactions or reduced host defense. In general, most safety and side effect concerns associated with traditional Ab therapies (97, 98) are worthy of attention during TCRL Ab development and preclinical evaluation. To minimize the chance of causing adverse effects, efforts in 1) Fc engineering/modification to control Fc-mediated effector function, 2) advanced affinity maturation to avoid exaggerated/prolonged mAb binding to the target, and 3) rigorous immunopharmacology studies in vitro and in animal models (97), will be crucial at stages prior to clinical trials.

Future directions

Despite great promise, effectively leveraging modern TCRL technologies in autoimmune therapy still requires optimization: First, advanced tools and innovative strategies for autoantigen discovery are still needed, as highly accurate identification and characterization of HLA-restricted peptide antigens are a prerequisite for downstream development of TCRL agents. Secondly, directed evolution and affinity maturation for low affinity TCRL candidates are still challenging, although combinatorial libraries designed using phage and yeast display platforms offer potential solutions. As more and more TCR and TCRL mAb structures emerge, machine learning (99) may offer more guidance on TCRL engineering. Last, for use in physiologic conditions, protein scaffolds other than mAbs sometimes possess better properties including protein stability, reduced immunogenicity, and increased tissue penetration (90, 100). Lessons learned from TCRL mAb development can be applied to alternative protein scaffolds (90) to expand TCRL methodology. Ongoing TCRL projects are focusing on resolving these issues, in hopes of opening an era for next generation autoimmune research and therapies.

Author contributions

YL, WJ, and EM wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Fugger L, Jensen LT, Rossjohn J. Challenges, progress, and prospects of developing therapies to treat autoimmune diseases. Cell (2020) 181(1):63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenblum MD, Remedios KA, Abbas AK. Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. J Clin Invest (2015) 125(6):2228–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI78088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dendrou CA, Petersen J, Rossjohn J, Fugger L. HLA variation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18(5):325–39. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caliskan M, Brown CD, Maranville JC. A catalog of GWAS fine-mapping efforts in autoimmune disease. Am J Hum Genet (2021) 108(4):549–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neefjes J, Jongsma ML, Paul P, Bakke O. Towards a systems understanding of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11(12):823–36. doi: 10.1038/nri3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet (2018) 391(10115):70–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hung SC, Hou T, Jiang W, Wang N, Qiao SW, Chow IT, et al. Epitope selection for HLA-DQ2 presentation: Implications for celiac disease and viral defense. J Immunol (2019) 202(9):2558–69. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bassetti CLA, Adamantidis A, Burdakov D, Han F, Gay S, Kallweit U, et al. Narcolepsy - clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol (2019) 15(9):519–39. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang W, Birtley JR, Hung SC, Wang W, Chiou SH, Macaubas C, et al. In vivo clonal expansion and phenotypes of hypocretin-specific CD4(+) T cells in narcolepsy patients and controls. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):5247. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13234-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Busch R, Kollnberger S, Mellins ED. HLA associations in inflammatory arthritis: emerging mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Rheumatol (2019) 15(6):364–81. doi: 10.1038/s41584-019-0219-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin R, Sospedra M, Eiermann T, Olsson T. Multiple sclerosis: doubling down on MHC. Trends Genet (2021) 37(9):784–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Busch R, Rinderknecht CH, Roh S, Lee AW, Harding JJ, Burster T, et al. Achieving stability through editing and chaperoning: regulation of MHC class II peptide binding and expression. Immunol Rev (2005) 207:242–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang W, Adler LN, Macmillan H, Mellins ED. Synergy between b cell receptor/antigen uptake and MHCII peptide editing relies on HLA-DO tuning. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):13877. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50455-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scally SW, Petersen J, Law SC, Dudek NL, Nel HJ, Loh KL, et al. A molecular basis for the association of the HLA-DRB1 locus, citrullination, and rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med (2013) 210(12):2569–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ooi JD, Petersen J, Tan YH, Huynh M, Willett ZJ, Ramarathinam SH, et al. Dominant protection from HLA-linked autoimmunity by antigen-specific regulatory T cells. Nature (2017) 545(7653):243–7. doi: 10.1038/nature22329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christophersen A, Lund EG, Snir O, Sola E, Kanduri C, Dahal-Koirala S, et al. Distinct phenotype of CD4(+) T cells driving celiac disease identified in multiple autoimmune conditions. Nat Med (2019) 25(5):734–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0403-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jung D, Alt FW. Unraveling V(D)J recombination; insights into gene regulation. Cell (2004) 116(2):299–311. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00039-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooper MD, Alder MN. The evolution of adaptive immune systems. Cell (2006) 124(4):815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yasunaga M. Antibody therapeutics and immunoregulation in cancer and autoimmune disease. Semin Cancer Biol (2020) 64:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoydahl LS, Frick R, Sandlie I, Loset GA. Targeting the MHC ligandome by use of TCR-like antibodies. Antibodies (Basel) (2019) 8(2):32. doi: 10.3390/antib8020032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alcover A, Alarcon B, Di Bartolo V. Cell biology of T cell receptor expression and regulation. Annu Rev Immunol (2018) 36:103–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sela-Culang I, Kunik V, Ofran Y. The structural basis of antibody-antigen recognition. Front Immunol (2013) 4:302. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Subbramanian RA, Moriya C, Martin KL, Peyerl FW, Hasegawa A, Naoi A, et al. Engineered T-cell receptor tetramers bind MHC-peptide complexes with high affinity. Nat Biotechnol (2004) 22(11):1429–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holler PD, Holman PO, Shusta EV, O'Herrin S, Wittrup KD, Kranz DM. In vitro evolution of a T cell receptor with high affinity for peptide/MHC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97(10):5387–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weber KS, Donermeyer DL, Allen PM, Kranz DM. Class II-restricted T cell receptor engineered in vitro for higher affinity retains peptide specificity and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2005) 102(52):19033–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507554102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones HF, Molvi Z, Klatt MG, Dao T, Scheinberg DA. Empirical and rational design of T cell receptor-based immunotherapies. Front Immunol (2020) 11:585385. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.585385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koehli S, Naeher D, Galati-Fournier V, Zehn D, Palmer E. Optimal T-cell receptor affinity for inducing autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2014) 111(48):17248–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402724111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holler PD, Chlewicki LK, Kranz DM. TCRs with high affinity for foreign pMHC show self-reactivity. Nat Immunol (2003) 4(1):55–62. doi: 10.1038/ni863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cameron BJ, Gerry AB, Dukes J, Harper JV, Kannan V, Bianchi FC, et al. Identification of a titin-derived HLA-A1-presented peptide as a cross-reactive target for engineered MAGE A3-directed T cells. Sci Transl Med (2013) 5(197):197ra03. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. He Q, Liu Z, Liu Z, Lai Y, Zhou X, Weng J. TCR-like antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol (2019) 12(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0788-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duan Z, Ho M. T-Cell receptor mimic antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther (2021) 20(9):1533–41. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hulsmeyer M, Chames P, Hillig RC, Stanfield RL, Held G, Coulie PG, et al. A major histocompatibility complex-peptide-restricted antibody and t cell receptor molecules recognize their target by distinct binding modes: crystal structure of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A1-MAGE-A1 in complex with FAB-HYB3. J Biol Chem (2005) 280(4):2972–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411323200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mareeva T, Martinez-Hackert E, Sykulev Y. How a T cell receptor-like antibody recognizes major histocompatibility complex-bound peptide. J Biol Chem (2008) 283(43):29053–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804996200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stewart-Jones G, Wadle A, Hombach A, Shenderov E, Held G, Fischer E, et al. Rational development of high-affinity T-cell receptor-like antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2009) 106(14):5784–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901425106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ataie N, Xiang J, Cheng N, Brea EJ, Lu W, Scheinberg DA, et al. Structure of a TCR-mimic antibody with target predicts pharmacogenetics. J Mol Biol (2016) 428(1):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adams JJ, Narayanan S, Liu B, Birnbaum ME, Kruse AC, Bowerman NA, et al. T Cell receptor signaling is limited by docking geometry to peptide-major histocompatibility complex. Immunity (2011) 35(5):681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frick R, Hoydahl LS, Petersen J, du Pre MF, Kumari S, Berntsen G, et al. A high-affinity human TCR-like antibody detects celiac disease gluten peptide-MHC complexes and inhibits T cell activation. Sci Immunol (2021) 6(62):eabg4925. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg4925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Petersen J, Montserrat V, Mujico JR, Loh KL, Beringer DX, van Lummel M, et al. T-Cell receptor recognition of HLA-DQ2-gliadin complexes associated with celiac disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2014) 21(5):480–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature (1975) 256(5517):495–7. doi: 10.1038/256495a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kozono H, White J, Clements J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Production of soluble MHC class II proteins with covalently bound single peptides. Nature (1994) 369(6476):151–4. doi: 10.1038/369151a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith GP. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science (1985) 228(4705):1315–7. doi: 10.1126/science.4001944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol (1997) 15(6):553–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murphy DB, Lo D, Rath S, Brinster RL, Flavell RA, Slanetz A, et al. A novel MHC class II epitope expressed in thymic medulla but not cortex. Nature (1989) 338(6218):765–8. doi: 10.1038/338765a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rudensky A, Rath S, Preston-Hurlburt P, Murphy DB, Janeway CA, Jr. On the complexity of self. Nature (1991) 353(6345):660–2. doi: 10.1038/353660a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhong G, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN. Production, specificity, and functionality of monoclonal antibodies to specific peptide-major histocompatibility complex class II complexes formed by processing of exogenous protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94(25):13856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spanier JA, Frederick DR, Taylor JJ, Heffernan JR, Kotov DI, Martinov T, et al. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies against peptide in the context of MHCII using magnetic enrichment. Nat Commun (2016) 7:11804. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aharoni R, Teitelbaum D, Arnon R, Puri J. Immunomodulation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by antibodies to the antigen-ia complex. Nature (1991) 351(6322):147–50. doi: 10.1038/351147a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Puri J, Arnon R, Gurevich E, Teitelbaum D. Modulation of the immune response in multiple sclerosis: production of monoclonal antibodies specific to HLA/myelin basic protein. J Immunol (1997) 158(5):2471–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krogsgaard M, Wucherpfennig KW, Cannella B, Hansen BE, Svejgaard A, Pyrdol J, et al. Visualization of myelin basic protein (MBP) T cell epitopes in multiple sclerosis lesions using a monoclonal antibody specific for the human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR2-MBP 85-99 complex. J Exp Med (2000) 191(8):1395–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Steenbakkers PG, Baeten D, Rovers E, Veys EM, Rijnders AW, Meijerink J, et al. Localization of MHC class II/human cartilage glycoprotein-39 complexes in synovia of rheumatoid arthritis patients using complex-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol (2003) 170(11):5719–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baeten D, Steenbakkers PG, Rijnders AM, Boots AM, Veys EM, De Keyser F. Detection of major histocompatibility complex/human cartilage gp-39 complexes in rheumatoid arthritis synovitis as a specific and independent histologic marker. Arthritis Rheumatol (2004) 50(2):444–51. doi: 10.1002/art.20012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dahan R, Tabul M, Chou YK, Meza-Romero R, Andrew S, Ferro AJ, et al. TCR-like antibodies distinguish conformational and functional differences in two- versus four-domain auto reactive MHC class II-peptide complexes. Eur J Immunol (2011) 41(5):1465–79. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dahan R, Gebe JA, Preisinger A, James EA, Tendler M, Nepom GT, et al. Antigen-specific immunomodulation for type 1 diabetes by novel recombinant antibodies directed against diabetes-associates auto-reactive T cell epitope. J Autoimmun (2013) 47:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang L, Crawford F, Yu L, Michels A, Nakayama M, Davidson HW, et al. Monoclonal antibody blocking the recognition of an insulin peptide-MHC complex modulates type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111(7):2656–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323436111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang L, Sosinowski T, Cox AR, Cepeda JR, Sekhar NS, Hartig SM, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells targeting a pathogenic MHC class II:peptide complex modulate the progression of autoimmune diabetes. J Autoimmun (2019) 96:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hoydahl LS, Richter L, Frick R, Snir O, Gunnarsen KS, Landsverk OJB, et al. Plasma cells are the most abundant gluten peptide MHC-expressing cells in inflamed intestinal tissues from patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology (2019) 156(5):1428–39.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cepeda JR, Sekhar NS, Han J, Xiong W, Zhang N, Yu L, et al. A monoclonal antibody with broad specificity for the ligands of insulin B:9-23 reactive T cells prevents spontaneous type 1 diabetes in mice. MAbs (2020) 12(1):1836714. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2020.1836714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matsumoto Y, Kishida K, Matsumoto M, Matsuoka S, Kohyama M, Suenaga T, et al. A TCR-like antibody against a proinsulin-containing fusion peptide ameliorates type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2021) 534:680–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wolpl A, Halder T, Kalbacher H, Neumeyer H, Siemoneit K, Goldmann SF, et al. Human monoclonal antibody with T-cell-like specificity recognizes MHC class I self-peptide presented by HLA-DR1 on activated cells. Tissue Antigens (1998) 51(3):258–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stang E, Guerra CB, Amaya M, Paterson Y, Bakke O, Mellins ED. DR/CLIP (class II-associated invariant chain peptides) and DR/peptide complexes colocalize in prelysosomes in human b lymphoblastoid cells. J Immunol (1998) 160(10):4696–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reay PA, Matsui K, Haase K, Wulfing C, Chien YH, Davis MM. Determination of the relationship between T cell responsiveness and the number of MHC-peptide complexes using specific monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol (2000) 164(11):5626–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Baldwin KK, Reay PA, Wu L, Farr A, Davis MM. A T cell receptor-specific blockade of positive selection. J Exp Med (1999) 189(1):13–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Andersen PS, Stryhn A, Hansen BE, Fugger L, Engberg J, Buus S. A recombinant antibody with the antigen-specific, major histocompatibility complex-restricted specificity of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1996) 93(5):1820–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dadaglio G, Nelson CA, Deck MB, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Characterization and quantitation of peptide-MHC complexes produced from hen egg lysozyme using a monoclonal antibody. Immunity (1997) 6(6):727–38. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80448-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Morkowski S, Goldrath AW, Eastman S, Ramachandra L, Freed DC, Whiteley P, et al. T Cell recognition of major histocompatibility complex class II complexes with invariant chain processing intermediates. J Exp Med (1995) 182(5):1403–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dass SA, Selva Rajan R, Tye GJ, Balakrishnan V. The potential applications of T cell receptor (TCR)-like antibody in cervical cancer immunotherapy. Hum Vaccin Immunother (2021) 17(9):2981–94. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1913960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Muraille E, Gounon P, Cazareth J, Hoebeke J, Lippuner C, Davalos-Misslitz A, et al. Direct visualization of peptide/MHC complexes at the surface and in the intracellular compartments of cells infected in vivo by leishmania major. PloS Pathog (2010) 6(10):e1001154. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sengupta S, Board NL, Wu F, Moskovljevic M, Douglass J, Zhang J, et al. TCR-mimic bispecific antibodies to target the HIV-1 reservoir. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2022) 119(15):e2123406119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2123406119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu X, Xu Y, Xiong W, Yin B, Huang Y, Chu J, et al. Development of a TCR-like antibody and chimeric antigen receptor against NY-ESO-1/HLA-A2 for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer (2022) 10(3):e004035. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ledsgaard L, Kilstrup M, Karatt-Vellatt A, McCafferty J, Laustsen AH. Basics of antibody phage display technology. Toxins (Basel) (2018) 10(6):236. doi: 10.3390/toxins10060236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhao Q, Ahmed M, Tassev DV, Hasan A, Kuo TY, Guo HF, et al. Affinity maturation of T-cell receptor-like antibodies for wilms tumor 1 peptide greatly enhances therapeutic potential. Leukemia (2015) 29(11):2238–47. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liu R, Jiang W, Li Y, Mellins ED. RIPPA: Identification of MHC-II binding peptides from antigen using a yeast display-based approach. Curr Protoc (2022) 2(1):e350. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liu R, Jiang W, Mellins ED. Yeast display of MHC-II enables rapid identification of peptide ligands from protein antigens (RIPPA). Cell Mol Immunol (2021) 18(8):1847–60. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00717-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Feldhaus MJ, Siegel RW, Opresko LK, Coleman JR, Feldhaus JM, Yeung YA, et al. Flow-cytometric isolation of human antibodies from a nonimmune saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display library. Nat Biotechnol (2003) 21(2):163–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jiang W, Boder ET. High-throughput engineering and analysis of peptide binding to class II MHC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107(30):13258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006344107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lipski DA, Dewispelaere R, Foucart V, Caspers LE, Defrance M, Bruyns C, et al. MHC class II expression and potential antigen-presenting cells in the retina during experimental autoimmune uveitis. J Neuroinflammation (2017) 14(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0915-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zakharov PN, Hu H, Wan X, Unanue ER. Single-cell RNA sequencing of murine islets shows high cellular complexity at all stages of autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med (2020) 217(6):e20192362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20192362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Thayer TC, Wilson SB, Mathews CE. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am (2010) 39(3):541–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lee BH, Gauna AE, Pauley KM, Park YJ, Cha S. Animal models in autoimmune diseases: lessons learned from mouse models for sjogren's syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (2012) 42(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8288-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Allen JS, Pang K, Skowera A, Ellis R, Rackham C, Lozanoska-Ochser B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are proportionally expanded at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and enhance islet autoantigen presentation to T-cells through immune complex capture. Diabetes (2009) 58(1):138–45. doi: 10.2337/db08-0964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bottazzo GF, Dean BM, McNally JM, MacKay EH, Swift PG, Gamble DR. In situ characterization of autoimmune phenomena and expression of HLA molecules in the pancreas in diabetic insulitis. N Engl J Med (1985) 313(6):353–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508083130604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Joosse BA, Jackson JH, Cisneros A, Santhin AB, Smith SA, Moore DJ, et al. High-throughput detection of autoantigen-specific b cells among distinct functional subsets in autoimmune donors. Front Immunol (2021) 12:685718. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.685718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Parodis I, Stockfelt M, Sjowall C. B cell therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: From rationale to clinical practice. Front Med (Lausanne) (2020) 7:316. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Phillips BE, Garciafigueroa Y, Trucco M, Giannoukakis N. Clinical tolerogenic dendritic cells: Exploring therapeutic impact on human autoimmune disease. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1279. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vos K, Miltenburg AM, van Meijgaarden KE, van den Heuvel M, Elferink DG, van Galen PJ, et al. Cellular immune response to human cartilage glycoprotein-39 (HC gp-39)-derived peptides in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. Rheumatol (Oxf) (2000) 39(12):1326–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Purbhoo MA, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM. T Cell killing does not require the formation of a stable mature immunological synapse. Nat Immunol (2004) 5(5):524–30. doi: 10.1038/ni1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bernardeau K, Gouard S, David G, Ruellan AL, Devys A, Barbet J, et al. Assessment of CD8 involvement in T cell clone avidity by direct measurement of HLA-A2/Mage3 complex density using a high-affinity TCR like monoclonal antibody. Eur J Immunol (2005) 35(10):2864–75. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ke Q, Kroger CJ, Clark M, Tisch RM. Evolving antibody therapies for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Front Immunol (2020) 11:624568. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.624568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yu XZ, Anasetti C. Enhancement of susceptibility to fas-mediated apoptosis of TH1 cells by nonmitogenic anti-CD3epsilon F(ab')2. Transplantation (2000) 69(1):104–12. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001150-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Boder ET, Jiang W. Engineering antibodies for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng (2011) 2:53–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mok CC. Rituximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an update. Drug Des Devel Ther (2013) 8:87–100. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S41645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rigby W, Tony HP, Oelke K, Combe B, Laster A, von Muhlen CA, et al. Safety and efficacy of ocrelizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a forty-eight-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase III trial. Arthritis Rheumatol (2012) 64(2):350–9. doi: 10.1002/art.33317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Brezski RJ, Georgiou G. Immunoglobulin isotype knowledge and application to fc engineering. Curr Opin Immunol (2016) 40:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Brezski RJ, Kinder M, Grugan KD, Soring KL, Carton J, Greenplate AR, et al. A monoclonal antibody against hinge-cleaved IgG restores effector function to proteolytically-inactivated IgGs in vitro and in vivo. MAbs (2014) 6(5):1265–73. doi: 10.4161/mabs.29825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Boks MA, Kager-Groenland JR, Haasjes MS, Zwaginga JJ, van Ham SM, ten Brinke A. IL-10-generated tolerogenic dendritic cells are optimal for functional regulatory T cell induction–a comparative study of human clinical-applicable DC. Clin Immunol (2012) 142(3):332–42. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Maldini CR, Ellis GI, Riley JL. CAR T cells for infection, autoimmunity and allotransplantation. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18(10):605–16. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0042-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Brennan FR, Morton LD, Spindeldreher S, Kiessling A, Allenspach R, Hey A, et al. Safety and immunotoxicity assessment of immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies. MAbs (2010) 2(3):233–55. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hansel TT, Kropshofer H, Singer T, Mitchell JA, George AJ. The safety and side effects of monoclonal antibodies. Nat Rev Drug Discovery (2010) 9(4):325–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dhusia K, Su Z, Wu Y. A structural-based machine learning method to classify binding affinities between TCR and peptide-MHC complexes. Mol Immunol (2021) 139:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhu L, Yang X, Zhong D, Xie S, Shi W, Li Y, et al. Single-domain antibody-based TCR-like CAR-T: A potential cancer therapy. J Immunol Res (2020) 2020:2454907. doi: 10.1155/2020/2454907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]