Abstract

Nasal septal cartilage perforations occur due to the different pathologies. Limited healing ability of cartilage results in remaining defects and further complications. This study sought to assess the efficacy of elastin–gelatin–hyaluronic acid (EGH) scaffolds for regeneration of nasal septal cartilage defects in rabbits. Defects (4 × 7 mm) were created in the nasal septal cartilage of 24 New Zealand rabbits. They were randomly divided into four groups: Group 1 was the control group with no further intervention, Group 2 received EGH scaffolds implanted in the defects, Group 3 received EGH scaffolds seeded with autologous auricular chondrocytes implanted in the defects, and Group 4 received EGH scaffolds seeded with homologous auricular chondrocytes implanted in the defects. After a 4-month healing period, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were obtained from the nasal septal cartilage, followed by histological evaluations of new tissue formation. Maximum regeneration occurred in Group 2, according to CT, and Group 3, according to both T1 and T2 images with 7.68 ± 1.36, 5.44 ± 2.41, and 8.72 ± 3.02 mm2 defect area respectively after healing. The difference in the defect size was statistically significant after healing between the experimental groups. Group 3 showed significantly greater regeneration according to CT scans and T1 and T2 images. The neocartilage formed over the underlying old cartilage with no distinct margin in histological evaluation. The EGH scaffolds have the capability of regeneration of nasal cartilage defects and are able to integrate with the existing cartilage; yet, they present the best results when pre-seeded with autologous chondrocytes.

Keywords: cartilage, nasal septum, regeneration, tissue scaffolds

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

The ultimate goal of tissue engineering is to develop a functional tissue to replace, preserve, or enhance the tissue function. Tissue engineering requires three main components: cells, scaffolds, and growth factors. There is a growing demand for clinically applicable novel scaffolds with easy fabrication. An ideal scaffold provides a compatible framework for the cells physically, chemically, and biologically.1,2

Cartilage has a limited healing capacity due to slow turnover rate and difficult migration of cells through the dense extracellular matrix, as well as its avascularity.3,4 Nasal septal cartilage is quadrangular hyaline cartilage that acts as a strut at the midline to support the lateral structures of the nose.5 Nasal septal cartilage perforations and defects occur due to trauma, iatrogenic procedures, neoplastic lesions, inflammation, infection, granulomatous diseases, or use of cocaine, toxic metals, or topical corticosteroids. Congenital defects may occur in the case of abnormal growth or developmental anomalies such as the cleft palate. The most common causes of nasal septal cartilage perforation include previous nasal surgery and trauma. Impairments in the nasal septal cartilage can compromise the nasal airway function and lead to symptoms such as epistaxis, crust formation, nasal congestion and dryness, rhinorrhea, malodor, and whistling.6-8

Several materials and techniques have been employed for the closure of such defects. Autologous auricular conchal9 or costal cartilage,10 mucoperichondrial flap, temporoparietal fascia graft, postauricular connective tissue,7 and mastoid cortical bone with its periosteum11 have been used for this purpose. Limited availability and donor site morbidity restrict the wide utilization of autologous grafts in reconstructive procedures.12 Synthetic materials, including silicone, porous polyethylene and bioactive glass, or allograft materials like Alloderm, serve as mechanical barriers, but they cannot integrate with the surrounding tissues, which raises the risk of infection and dislocation.13 Ideal treatment should not only include closure of the defect, but also rehabilitation of the normal structure and function of tissue.11,14-16

Numerous attempts have been made to engineer cartilage tissue. This entails harvesting a small amount of cartilage tissue and expanding isolated chondrocytes to obtain the required cell quantity. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from the bone marrow, synovium, and adipose tissue have been recruited to differentiate into chondrocytes. Suspension of the cells and injection into the cartilage defect or the transfer of hydrogel loaded with chondrocytes are practiced methods for articular cartilage regeneration that are not applicable in the maxillofacial region due to the fortifying role of cartilage in this region.17,18 Biodegradable scaffolds that fulfill the structural requirements have been proposed for this purpose, since they provide a three-dimensional (3D) mesh to which the chondrocytes can adhere and with which they can interact. The rate of biodegradation of scaffolds should be slower than the rate of cartilage tissue formation. Also, the scaffolds should not contain any cytotoxic or inflammatory byproducts. Poly-l-lactide, collagen, hyaluronan,17 polyglycolic acid,19 fibrin,4 l-polycaprolactone,20 and bacterial cellulose21 have been utilized as scaffolds to convey chondrocytes in cartilage tissue engineering.

Gelatin has been widely used in cartilage tissue engineering, even though it does not have sufficient consistency for structural support.22,23 Dynamic reciprocity between the gelatin amino-acid sequences and cells may enhance chondrocyte attachment.24 Elastin fibers and hyaluronic acid are components found in the extracellular matrix of cartilage and provide a familiar environment for the chondrocytes.25 The 3D printed porous elastin–gelatin–hyaluronic acid (EGH) scaffold has the potential to provide a compelling foundation for chondrocytes to penetrate, proliferate, and regenerate the cartilage tissue. Autologous cell sources do not have the risk of immunogenic rejection or disease transmission in clinical applications26; however, they have limited availability especially in the case of cartilage tissue regeneration. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage grafts are widely used in rhinoplasty.27 Although they have inferior performance compared with autologous grafts in histologic properties, durability, and aesthetics, their application has continued because there would be no need for an additional surgery to harvest autologous graft.28

Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are used for cartilage tissue imaging, but there is no agreement over which modality is superior in cartilage tissue projection. MRI scans have higher soft-tissue contrast resolution while CT scans have higher spatial resolution. Obtaining MRI scans with favorable contrast, spatial resolution, and different MRI sequences increase scanning time, resulting in motion artifacts, but CT scanners render images with lower risk of motion artifacts because of short scanning times.29 Consequently, both imaging modalities would be beneficial in cartilage tissue evaluations.

This experimental study, after investigation of the biocompatibility of the scaffolds using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay and cell morphology study, aimed to assess the efficacy of a 3D-printed EGH scaffold alone and in combination with chondrocytes for the regeneration of nasal septal cartilage defects in rabbits.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gelatin (Type A, from porcine skin, Bioreagent grade) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, Massachusetts). Sodium hyaluronate (Research Grade, 500–749 kDa) was obtained from Lifecore Biomedical (Chaska, Minnesota), and elastin (Elastin-Soluble, No. ES12, 60 kDa) was purchased from Lifecore Biomedical. 1-Ethyl-3-(3 dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were obtained from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, Massachusetts).

2.1 ∣. 3D-printing of EGH scaffolds

The EGF ink composition was optimized according to a previously published protocol.23 Briefly, to prepare EGH ink, sodium hyaluronate (0.5 wt %; Research Grade, 500–749 kDa), porcine gelatin (8 wt %; Type A, from porcine skin, Bioreagent grade), and elastin (2 wt %; Elastin-Soluble, No. ES12) were mixed in deionized water at 50°C for 2 hr and then at 40°C overnight in order to stabilize the solution. EnvisionTEC 3D-Bioplotter (Manufacturer Series, Germany) was used to preparing 3D-print skeletons. The pressure, speed, container temperature, and platform temperature were adjusted to 0.6–1 bar, 18–21 mm/s, 30°C–32°C, and 8°C, respectively. The needle diameter and distance between strands were 250 μm and 1 mm, respectively. Each membrane contained 16 layers with strand angles of 0° and 90°. To cross-link 3D-printed EGF scaffolds, they were immersed in a solution of 70% ethanol containing 5 mg/ml ethyl(dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and 0.5 mg/ml NHS for 3 hr. The residual of cross-linker was removed by washing the scaffolds in 1 L of DI water four times (each time for 30 min). For long-term preservation of the 3D-printed EGF scaffolds, they were stored in 100% ethanol in a −20°C freezer.

2.2 ∣. Laser microscope analysis

LEXT OLS4000 3D Laser Microscope (Olympus, Japan) was utilized for imaging the membranes. The 3D Laser Measuring Microscopy does not require sample preparation, and the imaging can be performed under room conditions.

2.3 ∣. Morphology study

The morphology of the bone marrow-derived normal human mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs; ATCC company) cultured on the 3D-printed scaffolds was examined after 1 day of cell culturing in basal media using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Briefly, after seeding 8 × 104 viable BM-MSCs on each scaffold (5 mm × 5 mm), they were cultured at 37°C for 1 day. Then, the cell-seeded scaffolds were washed with ×1 PBS and fixed in Karnovsky's Fixative at 4°C overnight. In order to dehydrate the fixed samples, they were exposed to graded ethanol solutions and then dried at room temperature. The gold–palladium sputtering was applied on the dried samples, and the SEM images were taken at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV using a scanning electron microscope (JEOL USA Scanning Electron Microscopes).

2.4 ∣. Biocompatibility assay

The biocompatibility of the scaffolds was measured using MTT assay on BM-MSCs-seeded scaffolds. For this reason, after sterilizing the scaffolds using UV, 8 × 104 viable BM-MSCs were cultured on the prepared sterile scaffolds in 96-well plates in basal medium. The BM-MSCs cultured on the plate were considered to be the control group. After 1 and 7 days of cell culturing, the cells were incubated in a 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C. Then, the supernatant was removed, and 100 μl of DMSO was used for each sample to dissolve the formazan crystals. A Synergy HTX multimode reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont) was used to analyze the solutions at 570 nm. The experiment was repeated three times and the values were described with standard deviation. To determine the significant variation between groups t-test was used, and p < .05 was considered as statistically significant. The size of the punched scaffolds was 0.5 × 0.5 mm to fit in a 96-well plate. The viability% of the BM-MSCs was determined as follows:

| (1) |

where, OD is optical density, which has been measured by the Synergy HTX reader.

2.5 ∣. Experimental design

Twenty-four adult New Zealand rabbits with an approximate mean weight of 3 kg were selected and randomly assigned to four groups:

Group 1: The defects were created without further intervention (control group).

Group 2: The defects were created, and the EGH scaffolds were implanted at the defect site.

Group 3: Auricular cartilages measuring 5 × 5 mm were excised and chondrocytes were expanded and added to the EGH scaffolds. The rabbits received autologous cells.

Group 4: Expanded chondrocytes were added to the EGH scaffolds. The rabbits received homologous (allogeneic) cells.

MRI and CT scans were obtained from all rabbits after an observational period of 4 months. All the defects were histologically evaluated after euthanizing the rabbits.

2.6 ∣. Cell harvesting and culture

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran (IR.UMSHA. REC.1397.753). The surgical excision of the auricular cartilage was performed in six rabbits under general anesthesia induced with ketamine (35 mg/kg, Alfasan Co., Netherlands), xylazine (5 mg/kg; Alfasan Co., Netherlands), and acepromazine (1 mg/kg; Alfasan Co., Netherlands) administered via intramuscular injection. Next, 5 × 5 mm pieces of the auricular cartilage were excised. They were rinsed with Hank's balanced salt solution (Gibco, Paisley, UK) twice and incubated in 0.05 trypsin solution (Gibco) for 60 min. The segments were sliced into 1 mm2 pieces. The fragments were transferred to collagenase type II solution (Gibco) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Biosera, France), and stored in a shaking incubator operating at 70 rpm at 37°C for 24 hr. The suspension was filtered through a 100-μm nylon cell strainer (The SureStrain Premium Cell Strainer, MTC-Bio, New Jersey) and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The pellets were suspended in medium-199 (Gibco) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1% of 10,000 unit/10000 μg penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The suspended cells were adhered to T25 culture flasks (SPL Life Sciences, South Korea), thereafter incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells started to proliferate. Half of the medium was refreshed every other day. At 70% confluence, the adequate cells were passaged with 0.25% trypsin–0.02% ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Gibco) to the T75 culture flask (SPL Life Sciences, South Korea) (Figure 1). Passaging was repeated when the cells reached 70% confluence in T75 culture flask. The cells of each rabbit were used at passage 2 for seeding two scaffolds. One scaffold was re-implanted back into the same rabbit from which the auricular cartilage sample had been taken as autologous cells (Group 3), and the other scaffold was inserted in a rabbit with no previous auricular surgery as homologous cells (Group 4).

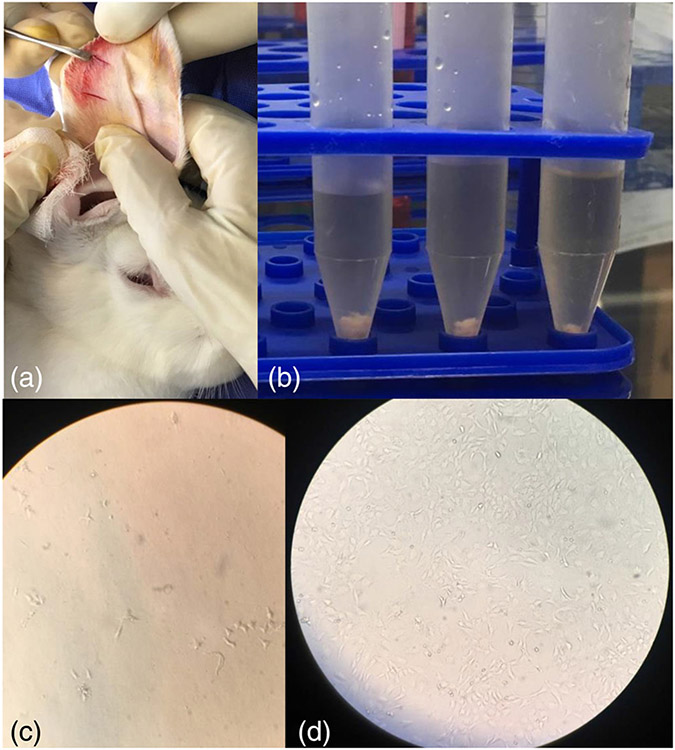

FIGURE 1.

Auricular chondrocytes were harvested and cultured. A piece of cartilage of the contralateral part of the rabbit's ear was excised (a), chondrocytes were isolated (b) and cultured. (c) The chondrocytes at the first stage of transfer to the culture flask and (d) the proliferated chondrocytes after 7 days

2.7 ∣. Seeding of scaffolds

The prepared pieces of the scaffolds (4 × 7 mm) were stored in 70% ethanol for 30 min, rinsed with PBS three times, and incubated in culture medium for 24 hr. At the second passage of subculture, when cells reach confluency (200,000 cells) suspended in 60 μl of FBS, they were added to each scaffold in a non-treated 12-well culture plate (SPL Life Sciences, South Korea) in two steps. The floor of the wells was wet with culture medium, and they were transferred to an incubator for 1 hr. Subsequently, the wells were filled with culture medium. After 48 hr, the scaffolds loaded with cells were ready for implantation in the created defects (Figure 2).

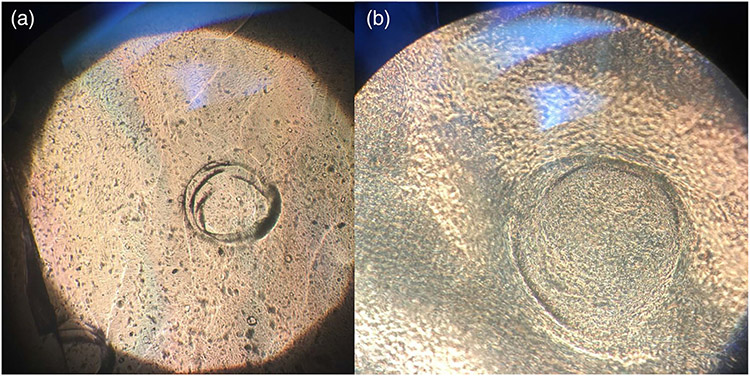

FIGURE 2.

Seeded scaffolds with chondrocytes at ×4 (a) and ×10 (b) magnifications

2.8 ∣. Surgical procedure

A total of 24 New Zealand white rabbits aged 9–18 months and weighing 2.5–4 kg were selected. General anesthesia was induced as described earlier for surgical excision of the auricular cartilage. The rabbits' snouts were shaved and prepped with povidone iodine. A pediatric uncuffed #2 endotracheal tube (Kaimed, China) was inserted into the nasal airway to maintain the airway patency during the procedure. Next, 0.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine was injected at three points into the nasal dorsum for local anesthesia induction and vasoconstriction. An incision was made at the midline from the frontonasal suture toward the nasal tip, and the skin flaps were elevated. The periosteum was incised as well, and periosteal flaps were elevated carefully to expose the nasal bones.

A bony window was created; the two horizontal and one parasagittal side of the window were separated from the adjacent bone, while one parasagittal side remained attached to the adjacent bone. The bony window was elevated from the free margins to the side of the attached margin. The nasal septal cartilage was exposed as such. The mucoperichondrium was dissected from both sides of the nasal septal cartilage. A 4 × 7 mm defect was created at the middle portion of the cartilage by a 15C blade while preserving the marginal integrity of the cartilage. Six rabbits in Group 1 received no scaffolds as the control group, while Group 2 received EGH scaffolds. EGH scaffolds seeded by autologous chondrocytes were placed in Group 3, and EGH scaffolds seeded by allogeneic chondrocytes were placed in Group 4 (Figure 3).

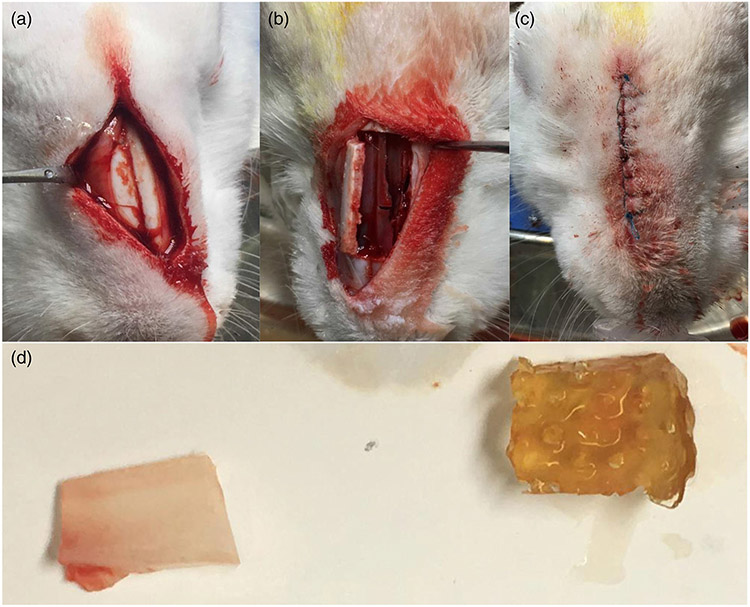

FIGURE 3.

Surgical procedure to create defect in the nasal septal cartilage and scaffold implantation. Subperiosteal flap exposed the nasal bones (a), a bony window provided access to the nasal septal cartilage (b) and after creating a defect and replacing the extracted piece of cartilage (on the left) with the scaffold (on the right) (d), the flaps were tightly sutured (c)

The elevated mucoperichondrium of both sides was reapproximated and sutured by 4-0 vicryl sutures (SUPA, Iran) to hold the scaffolds in place. The bony window was returned to its previous position without further intervention. The periosteal flaps were reapproximated over the bone and sutured in a continuous locking fashion with 4-0 vicryl suture. Finally, the skin flaps were sutured by 3-0 nylon sutures (SUPA, Iran). The rabbits were extubated, and oxytetracycline spray was used as a local antiseptic. Each rabbit received four doses of morphine sulfate (10 mg/ml) every 12 hr to relieve postoperative pain and three doses of oxytetracycline every 24 hr delivered intramuscularly. The rabbits were supervised for the first signs of infection or discomfort. A 4-month healing period was given to the rabbits.

2.9 ∣. Imaging

The MRI scans of the rabbit heads were obtained using a 1.5 T system (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens, Germany). The 3D T2 images were obtained at 25°C with the following sequence parameters: TR: 10.81 ms, TE: 4.84 ms, field of view: 150 mm, matrix: 320 × 320, slice thickness: 0.5 mm, distance between images: 0.5 mm, and signal to noise ratio: 1.00. The 3D T1 images were obtained at 25°C with TR: 14.5 ms, TE: 6.19 ms, field of view: 150 mm, matrix: 320 × 320, slice thickness: 0.5 mm, distance between images: 0.5 mm, and signal to noise ratio: 1.00.

The CT scans of the rabbit heads were obtained using a 16-slice CT scanner (Somatom Sensation, Siemens, Germany) with 120 kVp, 100 mAs, 0.8 mm slice thickness, 512 × 512 matrix, and 0.75 s rotation time.

The defect size was calculated by measuring the largest interruption in the nasal septal cartilage in coronal and axial planes. They were assumed as the major and minor axes of the oval-shaped defect and the defect area was calculated based on the ellipse area calculation formula (major axis × minor axis × π). The mean defect area of each experimental and control group was calculated. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normality assumption of data. Because the distribution of data was not normal, the Kruskal–Wallis rank test was used to analyze the differences between the groups. The Dunn's post-hoc test was used for pairwise comparisons. Differences were perceived statistically significant at p ≤ .05. Statistical analyses were performed by Stata 14.2 (StataCorp. LLC, Texas).

2.10 ∣. Histopathological assessment

The rabbits were euthanized by pentobarbital (120 mg/kg). A second surgery was performed to remove the nasal septal cartilage. The nasal septal cartilage was incised along with the mucoperichondrium to avoid redundant manipulation of the regenerated neocartilage. The specimens were fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution and then were embedded in paraffin. Next, 8-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin to detect cartilage formation and its relationship with the surrounding cartilage. Two sections were made at the borders of each defect. A blinded histopathologic evaluation was performed. Six visual histopathological parameters were assessed based on the following criteria. (a) Tissue integrity: the main section for histopathological evaluation was made at the border of the defect. When the integrity of the adjacent sections toward the defects was not retained, “no tissue integrity” was recorded for that specimen. (b) Inflammation: infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells were interpreted as presence of inflammation in the specimens. (c) Fibrosis: this would be seen as increase and intensification of collagen fibers in the stroma. (d) Granulation tissue: these tissues are composed of multiple vessels formed by endothelial cells and infiltration of inflammatory cells. (e) Calcification: the presence of amorphous basophilic structures indicate calcification. (f) Cartilage tissue formation: When presence of cartilage tissue was confirmed at the borders of the defect by histopathological evaluation, the neocartilage tissue formation was reported.

3 ∣. RESULTS

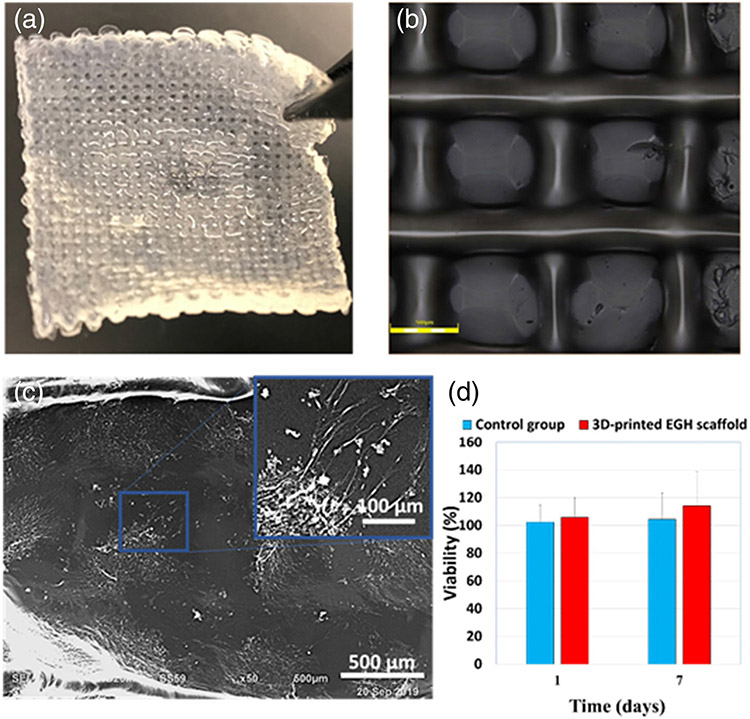

The 3D-printed EGH scaffolds were fabricated using 3D-printer (Figure 4a). The laser microscope images showed the structure of the fabricated 3D scaffold surface (Figure 4b). Three configurational characters of the membrane can be observed from the microscope images, orientation of the fibers, the fiber size, and the pore size. Since we have 3D-printed the layers of the membrane with the strand angles of 0° and 90°, the right angle between strands, or the quarter turn as the fiber orientation, was expected, which is confirmed in the microscope images (Figure 4b).

FIGURE 4.

In vitro characterization of the scaffold (a) The 3D-printed EGH scaffolds. (b) 3D Laser microscope images of scaffold. (c) The SEM images of the BM-MSCs cultured on the 3D-printed EGH scaffold 1 days after culturing in basal media. (d) Viability % of BM-MSCs after 1 and 7 days of culturing in basal medium on 3D-printed EGH scaffolds, and plate, as a control group

During the printing procedure, the diameter of the needle was 250 μm, and the distance between strands was 1 mm. However, as can be seen in the microscope image of Figure 4b, the diameter of the strands is larger than the needle diameter after printing. This is due to the spread of the gel when landing on the surface from the extrusion needle. According to the microscope image, the strand size became approximately 300–400 μm. On the other hand, such spread decreased the distance between strands, and thus, the pore size became smaller than 1 mm. As can be seen in Figure 4b, the pore size is approximately 500 μm.

The morphology of the BM-MSCs cultured on the scaffolds after 1 day is shown in Figure 4c. The images show the cells attached well and spread on the surface of the scaffold, and their morphology looked to form a spindle structure, as the morphology of BM-MSCs cultured on the plate. To determine the biocompatibility of the scaffolds, the MTT assay was performed on the BM-MSC-seeded scaffolds in the basal medium after 1 and 7 days. The BM-MSCs cultured in the plate were considered as the control group (Figure 4d). As the results demonstrated, the scaffolds were not toxic for the BM-MSCs.

All rabbits tolerated the surgical procedure. No sign of infection was noted at the surgical site or respiratory tract. The defect area was evaluated on T1 and T2 MRI and CT images (Figure 5). The mean defect area on T1, T2, and CT images calculated for the four experimental groups is reported in Table 1. Since the defects were created with 15C blades, the borders of the defects were sharp after surgery. Observation of a smaller defect, compared with the primary defect size with irregular margins on the images, was interpreted as neocartilage formation.

FIGURE 5.

CT scans in the sagittal (a), axial (b), and coronal (c) sections. MRI T1 scans in the sagittal (d), axial (e), and coronal (f) planes. MRI T2 scans in the sagittal (g), axial (h), and coronal (i) planes. The defects are determined by star

TABLE 1.

Mean and SD area of the defects (mm2) in nasal septal cartilage of each experimental and control group in CT, T1 MRI, and T2 MRI scans after 4 months healing period

| CT | MRI (T1) | MRI (T2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6) | 28.78 ± 3.64 | 22.06 ± 3.43 | 24.29 ± 2.84 |

| EGH (n = 6) | 7.68 ± 1.36 | 13.01 ± 2.50 | 14.26 ± 2.59 |

| EGH + autologous cells (n = 6) | 7.92 ± 2.78 | 5.44 ± 2.41 | 8.72 ± 3.02 |

| EGH + homologous cells (n = 6) | 12.12 ± 3.07 | 9.89 ± 3.58 | 10.86 ± 2.45 |

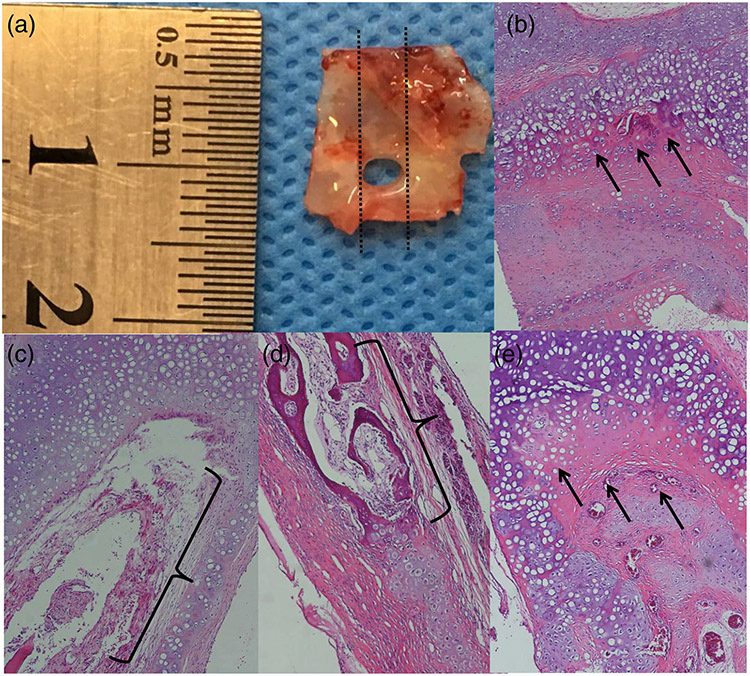

The results of the post-hoc test following Kruskal–Wallis test are reported in Table 2. The significance of differences (p-value) in defect size after a 4-month healing period between groups in CT, MRI T1, and T2 images is presented. The smallest defect size and maximum regeneration were noted in the EGH group on CT images (7.68 ± 1.36 mm2) and the EGH plus autologous cells group on both T1 (5.44 ± 2.41 mm2) and T2 (8.72 ± 3.02 mm2) images. The largest defect size was found in the control group on all CT (28.78 ± 3.64 mm2), T1 (22.06 ± 3.43 mm2), and T2 (24.29 ± 2.84 mm2) images; this group received no further regenerative intervention after defect creation. A significant difference in defect size was found only between the EGH group and the control group and between the EGH plus autologous cell group and the control group on CT images. On T1 images, a significant difference in defect size was found between the EGH plus autologous cells group and the control group, EGH plus homologous cell group and the control group, and EGH plus autologous cells group and the EGH group. On T2 images, significant differences in defect size were found between the EGH plus autologous cell group and the control group and also between the EGH plus homologous cell group and the control group. Histological findings are presented in Table 3. The number of observed histopathological parameters in each group specimens is reported. Figure 6 illustrates different histological findings mentioned in Table 3. Neocartilage formation along background cartilage tissue in an EGH scaffold specimen is presented in Figure 6b. Granulation tissue formation (Figure 6c) and bone formation (Figure 6d) are two findings in EGH plus homologous cell specimens. Neocartilage formation is well illustrated in an EGH plus autologous cell specimen (Figure 6e).

TABLE 2.

Significance of the differences (p-value) in defect size after healing period between groups in CT, MRI T1, and MRI T2 scans

| Control | EGH | EGH + autologous cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | EGH | <.001 | ||

| EGH + autologous cells | <.001 | .472 | ||

| EGH + homologous cells | .205 | .289 | .312 | |

| MRI T1 | EGH | .459 | ||

| EGH + autologous cells | <.001 | .016 | ||

| EGH + homologous cells | .012 | .471 | .478 | |

| MRI T2 | EGH | .616 | ||

| EGH + autologous cells | .001 | .131 | ||

| EGH + homologous cells | .036 | .674 | .709 |

TABLE 3.

The number of observations of histopathological parameters in each group specimens

| Tissue integrity | Inflammation | Fibrosis | Granulation tissue | Calcification | Cartilage tissue formation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| EGH | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| EGH + autologous cells | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| EGH + homologous cells | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

FIGURE 6.

Closest tissue to the borders of the defect; the dashed lines indicate the location of section for histological assessment (a), neocartilage formation (arrows) in an EGH scaffold specimen (b), granulation tissue formation (brackets) in an EGH plus homologous cell specimen (c), bone formation (brackets) in an EGH plus homologous cell specimen (d), and neocartilage formation (arrows) in an EGH plus autologous cell specimen (e)

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

We have selected the composition of 8% gelatin, 2% elastin, and 0.5% sodium hyaluronate to design this membrane. The rationale behind such selection is related to: (a) the suitable characters of each component, (b) the optimized printability of the composition, and (c) the positive in vitro result of using this composition to regenerate cartilage.

Regarding the suitable characters of each component, it is known that gelatin is low-cost and highly cell-attractant,30 sodium hyaluronate enhances the chemical signaling among cells,31 and elastin benefits from good biological activity, elasticity, and long-term stability.32 Regarding the optimized printability of the composition, we have previously performed comprehensive rheological analyses on various compositions of these three components.33 The results confirmed that the composition of 8% gelatin, 2% elastin, and 0.5% sodium hyaluronate presented the perfect printability with reproducible outcomes.33 Moreover, the 3D-printed membrane was shown to be robust, flexible, and suturable with appropriate mechanical properties and good surgical handling.33,34 Besides, our previous in vitro analyses of the similar membrane with the same composition confirmed its promising capability to regenerate cartilage.35

The size and location of the nasal septal cartilage defect dictate the treatment, which can vary from the closure of the defect with adjacent flaps to the use of synthetic materials.11 Restricted availability and morbidity of the donor site in autologous flaps, as well as the risk of infection and disintegration in synthetic materials, make the desired treatment difficult.14-16 Chondrocytes require a scaffold to facilitate their growth and proliferation as well as their movement along the defect.21 The 3D porous EGH scaffold allows the chondrocytes to penetrate, proliferate, and differentiate.

Few in vivo studies have tried to regenerate the nasal septal cartilage.8 Most studies have been carried out to evaluate materials and techniques for the regeneration of nasal septal cartilage defects. Martinez Neto et al.21 used bacterial cellulose to regenerate defects artificially created in the nasal septal cartilage of rabbits. The implanted cellulose scaffolds served as an infrastructure for epithelialization in cases that remained in place. In our study, we identified cartilage tissue formation in all the experimental groups despite Martinez Neto et al.'s21 study that their scaffold acted as a bed for the epithelium to proliferate. Bermueller et al.13 attempted to regenerate the nasal septal cartilage of rats with marine collagen scaffolds. They detached the total nasal septum and placed the collagen scaffolds. They compared the results of three groups: control group, collagen scaffold, and collagen scaffold seeded with chondrocytes. They reported cartilage formation in the implanted scaffolds and scaffolds accompanied by chondrocytes. Scaffolds seeded with cells showed higher efficacy for cartilage tissue regeneration. Although the scaffold they implanted is totally different from the composition we utilized for cartilage regeneration, the superior performance of seeded scaffolds with chondrocytes compared with the scaffolds alone is similar. Elsaesser et al.36 used porcine decellularized nasal septal cartilage to regenerate perforations they created in the nasal septal cartilage of rats. They used xenograft collagen scaffolds. They implanted the scaffolds in perforations alone and in combination with chondrocytes. The regenerated cartilage in the implanted scaffolds integrated with the surrounding cartilage, and the perforations were completely closed with neocartilage tissue. There was no significant difference between the scaffold alone and the scaffold with cells. They reported that the xenograft collagen scaffold is a promising material for nasal septal cartilage tissue engineering. Unlike the Bermueller et al.13 study that excised the whole nasal septal cartilage and did not maintain a cartilage bed for the scaffold insertion, Elsaesser et al.36 created a defect in the nasal cartilage similar to our study and preserved a cartilage margin around the defect that supported the implanted scaffold. They could get the integrity in the nasal septal cartilage by the xenograft collagen scaffold insertion in the defects they had created, an ideal treatment that EGH scaffold could not fulfill. It should be noticed that they used a 4 mm biopsy punch to perforate the nasal septal cartilage that makes a much smaller perforation than the defect we created. In accordance to our study the performance of the seeded scaffolds in cartilage regeneration was not statistically different from scaffolds alone.

Histological and immunohistological techniques are traditionally used to evaluate the engineered tissues, but these techniques are not able to provide volumetric or functional information.37 MRI illustrates soft tissues with high resolution. In vivo imaging of cartilage tissue is not simple. Chou et al.24 fabricated gelatin–hyaluronic acid–chondroitin sulfate scaffolds. They seeded a group with cells and implanted them and monitored cartilage tissue formation on T1 and T2 MRI images. T2 diminished during several image acquisitions, which is indicative of enhancement in cellularity of the tissue and macromolecular formation. Although Chou et al. used one of the most similar compositions to EGH scaffold to regenerate cartilage tissue, the methodology of monitoring tissue formation is completely different from this study. What makes the present study valuable is quantization of imaging data to infer the regeneration ability of the scaffolds. Welsch et al.38 investigated femoral cartilage tissue on T2 images and concluded that MRI is a reliable imaging modality for the assessment of cartilage tissue regeneration. CT provides images with high resolution, which results from a small focal spot of the X-ray tube and the remarkable ability of its imaging receptor.37 Although MRI is superior to CT in soft tissue visualization, the contrast between the empty space of the defect and the surrounding cartilage tissue on CT images could be precisely recognized. Thus, the preferable characteristics of CT could be beneficial in determining the defect size.

In the present study, the size of the defects created in the surgical session is 4 × 7 mm, 28 mm2. The area of defects after a 4-month healing period was compared with this initial defect size. When the defect size after the healing period has a smaller area than 28 mm2, we can interpret it as neotissue formation, and the identity of this tissue can be recognized by further histopathological evaluations. The size of defects decreased in all groups after the healing period. This indicates that the cartilage has slight repair potential without further regenerative guidance, and the size of defects in the control group was larger than those in other groups. This repair ability has been noticed in previous studies as well and is probably due to the potential of the adjacent perichondrial cells to differentiate and proliferate into the defect.39

The midsagittal planes would illustrate the defects more evidently but would not present the actual dimensions of the defects, due to the presence of nasal septal deviation or distanced boundaries of the defect that are likely attributed to the weak structural consistency against respiratory traumas (such as coughing and sneezing) in presence of the defect. Consequently, the largest interruption of nasal septal cartilage detected in the coronal and axial planes when scrolling the sections was assumed as the diameter of oval-shaped defects; the defect area was calculated as such. The EGH scaffolds, both alone and seeded with homologous chondrocytes or autologous chondrocytes, improve cartilage regeneration in nasal septal cartilage defects. The EGH scaffolds provide a suitable environment for chondrocytes to migrate through and deposit cartilage tissue; yet, the best results are obtained when EGH scaffolds are pre-seeded with autologous chondrocytes. Since the cartilage is an avascular tissue, homologous grafts may encounter less immune response and further resorption or rejection, but it should be noted that nasal septal cartilage has the adjacent mucoperichondrium on both sides, which is a tissue with a rich blood supply40 and has the potential of unfavorable immune reaction induction to the grafted homologous tissue. It may justify the better performance of EGH plus autologous cell group and even EGH alone in healing of the defects. EGH plus homologous cell group present better results compared with the control group in cartilage regeneration, demonstrating the superiority of scaffold application even with homologous cells compared with no intervention. Nevertheless, the most specimens with inflammation (two out of six) are related to EGH plus homologous cell group, and undesirable tissues (one granulation tissue and one osseous tissue) formed in the defect area are found in EGH plus homologous cell group too. The EGH group presents no statistically significant difference to the cell loaded scaffold groups except to the EGH plus autologous cell group in MRI T1 images that indicates, although an adjunctive surgery for autologous cell harvest and subsequent cell culture and scaffold seeding leads to the best results in cartilage regeneration, it may not cost the extra effort and following complications for the subjects. However, it is important to investigate in future studies if these differences affect the clinical improvement of complications.

In histological evaluations, cartilage tissue formation was recognized in all specimens. However, none of the defects were closed completely, and tissue integrity was not ideal in any of the specimens. The regenerated neocartilage at the defect margins formed over the underlying old cartilage, and no detectable border existed between them. In three specimens in the control group and one specimen in EGH plus homologous cell group, granulation tissue was found in the defect space. Bone formation was found in one of EGH plus homologous cell specimens. The surgical procedure of the defect creation and scaffold implantation were performed in the same session. As a result, we did not observe the atrophic borders of the cartilage. This could be the reason for cartilage tissue formation in a bed of cartilage without a clear boundary, resulting in integrity in the histological evaluation. Further similar studies should deliberate designing an instrument to punch the septal cartilage because standardization of the defect size in all samples was challenging due to difficult access.

5 ∣. CONCLUSION

The EGH scaffolds, both alone and in combination with homologous chondrocytes or autologous chondrocytes, can enhance cartilage regeneration in nasal septal cartilage defects. The EGH scaffolds present a novel framework for cartilage regeneration and demonstrate the best results when pre-seeded with autologous chondrocytes. Based on the results of the present study, EGH has the potential for use in nasal septal cartilage regeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Research and Technology Center of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. Part of the research reported in this article was supported by National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15DE027533. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14479734.v1

REFERENCES

- 1.Melek LN. Tissue engineering in oral and maxillofacial reconstruction. Tanta Dent J. 2015;12(3):211–223. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard D, Buttery LD, Shakesheff KM, Roberts SJ. Tissue engineering: strategies, stem cells and scaffolds. J Anat. 2008;213(1):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Osch GJ, Brittberg M, Dennis JE, et al. Cartilage repair: past and future: lessons for regenerative medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(5):792–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fussenegger M, Meinhart J, Hobling W, Kullich W, Funk S, Bernatzky G. Stabilized autologous fibrin-chondrocyte constructs for cartilage repair in vivo. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(5):493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holden PK, Liaw LH, Wong BJ. Human nasal cartilage ultrastructure: characteristics and comparison using scanning electron microscopy. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(7):1153–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scierski W, Polok A, Namyslowski G, et al. Study of selected biomaterials for reconstruction of septal nasal perforation. Otolaryngol Pol. 2007;61(5):842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzinger SE. Diagnosing and treating nasal septal perforations. Aesthet Surg J. 2005;25(5):524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavernia L, Brown WE, Wong BJF, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Toward tissue-engineering of nasal cartilages. Acta Biomater. 2019;88:42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua DY, Tan HK. Repair of nasal septal perforations using auricular conchal cartilage graft in children: report on three cases and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(7):1219–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanci D, Üstün O, Yilmazer AB, Göker AE, Kumral TL, Uyar Y. Costal cartilage and costal perichondrium sandwich graft in septal perforation repair. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31(5):1327–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedroza F, Patrocinio LG, Arevalo O. A review of 25-year experience of nasal septal perforation repair. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotter N, Haisch A, Bücheler M. Cartilage and bone tissue engineering for reconstructive head and neck surgery. Eur Arch Oto-rhinolaryngol. 2005;262(7):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bermueller C, Schwarz S, Elsaesser AF, et al. Marine collagen scaffolds for nasal cartilage repair: prevention of nasal septal perforations in a new orthotopic rat model using tissue engineering techniques. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:2201–2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berghaus A Implants for reconstructive surgery of the nose and ears. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;6:Doc06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang DT, Irace AL, Kawai K, Rogers-Vizena CR, Nuss R, Adil EA. Nasal septal perforation in children: presentation, etiology, and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;92:176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin MF, Premakumar Y, Seifalian AM, Szarko M, Butler PE. Biomechanical characterisation of the human nasal cartilages; implications for tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshi K, Fujihara Y, Saijo H, et al. Three-dimensional changes of noses after transplantation of implant-type tissue-engineered cartilage for secondary correction of cleft lip-nose patients. Regen Ther. 2017;7:72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson D, Reuther MS. Tissue-engineered cartilage for facial plastic surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22(4):300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oseni A, Crowley C, Lowdell M, Birchall M, Butler PE, Seifalian AM. Advancing nasal reconstructive surgery: the application of tissue engineering technology. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6(10):757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison RJ, Nasser HB, Kashlan KN, et al. Co-culture of adipose-derived stem cells and chondrocytes on three-dimensionally printed bioscaffolds for craniofacial cartilage engineering. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):E251–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez Neto EE, Dolci JE. Nasal septal perforation closure with bacterial cellulose in rabbits. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(4):442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han M-E, Kang BJ, Kim S-H, Kim HD, Hwang NS. Gelatin-based extracellular matrix cryogels for cartilage tissue engineering. J Ind Eng Chem. 2017;45:421–429. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhat S, Lidgren L, Kumar A. In vitro neo-cartilage formation on a three-dimensional composite polymeric cryogel matrix. Macromol Biosci. 2013;13(7):827–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou CH, Lee HS, Siow TY, et al. Temporal MRI characterization of gelatin/hyaluronic acid/chondroitin sulfate sponge for cartilage tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(8):2174–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sophia Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health. 2009;1(6):461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homicz MR, Schumacher BL, Sah RL, Watson D. Effects of serial expansion of septal chondrocytes on tissue-engineered neocartilage composition. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(5):398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sajjadian A, Naghshineh N, Rubinstein R. Current status of grafts and implants in rhinoplasty: part II. Homologous grafts and allogenic implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):99e–109e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wee JH, Mun SJ, Na WS, et al. Autologous vs irradiated homologous costal cartilage as graft material in rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(3):183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuno H, Sakamaki K, Fujii S, et al. Comparison of MR imaging and dual-energy CT for the evaluation of cartilage invasion by laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(3):524–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su K, Wang C. Recent advances in the use of gelatin in biomedical research. Biotechnol Lett. 2015;37(11):2139–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Entwistle J, Hall CL, Turley EA. HA receptors: regulators of signalling to the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61(4):569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee AY, Han B, Lamm SD, Fierro CA, Han H-C. Effects of elastin degradation and surrounding matrix support on artery stability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;302(4):H873–H884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehghani S, Rasoulianboroujeni M, Ghasemi H, et al. 3D-printed membrane as an alternative to amniotic membrane for ocular surface/conjunctival defect reconstruction: an in vitro and in vivo study. Biomaterials. 2018;174:95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tayebi L, Rasoulianboroujeni M, Moharamzadeh K, Almela TK, Cui Z, Ye H. 3D-printed membrane for guided tissue regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;84:148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tayebi L, Cui Z, Ye H. A tri-component knee plug for the 3rd generation of autologous chondrocyte implantation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elsaesser AF, Bermueller C, Schwarz S, Koerber L, Breiter R, Rotter N. In vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo effects of a decellularized xenogeneic collagen scaffold in nasal cartilage repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:1668–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Appel AA, Anastasio MA, Larson JC, Brey EM. Imaging challenges in biomaterials and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34(28):6615–6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welsch GH, Trattnig S, Hughes T, et al. T2 and T2* mapping in patients after matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation: initial results on clinical use with 3.0-tesla MRI. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(6):1515–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser ML, Karam AM, Sepehr A, et al. Cartilage regeneration in the rabbit nasal septum. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1730–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aksoy F, Yildirim YS, Demirhan H, Özturan O, Solakoglu S. Structural characteristics of septal cartilage and mucoperichondrium. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(1):38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14479734.v1