Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of bupivacaine compared with lidocaine in local anaesthesia in dental treatment. Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, Chinese BioMedical Literature Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched electronically. Relevant journals and references of studies included were hand-searched for randomised controlled trials comparing bupivacaine with lidocaine in terms of efficacy and safety. Sixteen studies were included, of which nine had low, six had moderate and one had high risk of bias. In comparison with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline, 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline showed a higher success rate in inflamed pulp (P = 0.03) but a lower success rate in vital pulp (P < 0.00001), a lower percentage of patients using postoperative analgesics (P < 0.00001), a longer onset times of pulpal anaesthesia and a longer duration of pulpal anaesthesia (P < 0.00001). In comparison with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline, 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline had same level of success rate (P = 0.29), and was better in postoperative pain control (P = 0.001) while 0.75% levobupivacaine had same level of postoperative pain control (P = 0.16); 0.5% levobupivacaine had higher success rate (P = 0.04) and was better in postoperative pain control (P = 0.001) than 2% lidocaine. There was no statistically significance in adverse events between two groups. Given the efficacy and safety, the bupivacaine group is better than the lidocaine group in dental operations that take a relatively long time, especially in endodontic treatments or where there is a need for postoperative pain management.

Key words: Bupivacaine, lidocaine, local anesthesia, meta-analysis, dentistry

INTRODUCTION

Management of pain is of great importance in dentistry, and sometimes prolonged analgesia is desirable1. According to the literature, more than 50% of Americans avoid dental treatments deliberately because of fear of pain, and similar data were found among Brazilians2., 3.. About 14% of 4- to 11-year-old Dutch children are dentally anxious, and the strongest fears are associated with pain4. As a result, local anaesthetics are commonly used to relieve pain and discomfort caused by dental treatment5.

Bupivacaine – the most widely used long-acting local aesthetic in surgery and obstetrics6 – was introduced into dentistry in 19727 and is considered to be one of the five major local anaesthetics used in dental treatments.5., 7., 8. According to statistics, 15,354 cartridges of bupivacaine solution were used in 2007 alone in Ontario9. In the last few decades, bupivacaine, the water-soluble amide local anaesthetic,1 has won a place in dentists’ armamentarium. This long-acting agent plays a significant role in the overall management of postoperative pain associated with dental care10. Because of its higher solubility in lipids and higher binding ability to proteins, bupivacaine has a longer duration of action than lidocaine, which is the gold standard all new local anaesthetics are compared with11., 12.. In addition, bupivacaine provides soft tissues, bones and pulp with relatively rapid and profound anaesthesia and therefore is widely used in dental treatments such as endodontic therapies, tooth extractions and dental surgery13. Levobupivacaine, the S-enantiomer of bupivacaine, is a new anaesthetic agent and is thought to have a better safety profile and equivalent efficacy compared with racemic bupivacaine14., 15., 16..

Clinically, several trials have compared bupivacaine with lidocaine in dental treatments in terms of efficacy and safety. However, the evidence base for bupivacaine’s reputation is not entirely obvious.

The aim of this paper was to investigate the efficacy and safety of bupivacaine compared with lidocaine in maxillary and mandibular infiltrations and block anaesthesia in patients presenting for routine non-complex dental treatments through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

METHODS

A protocol that specified the method was conducted in advance. Study selection, risk of bias assessment and data extraction were performed in duplicate by two calibrated reviewers. Any disagreement between them was resolved through discussion and any unresolved issues were brought to a third reviewer for consensus.

Selection criteria

The trials included should:

-

•

Be pre-emptive randomised controlled trials or quasi-randomised controlled trials that explored the efficacy and safety of bupivacaine compared with lidocaine in local anaesthesia of dental treatments

-

•

Have patients who go through dental treatment and need any aesthetic treatment regardless of their gender, race, social and economical status

-

•

Have an intervention group that received preoperative bupivacaine or levobupivacaine as the local anaesthetic compared to lidocaine in the control group

-

•

Have outcome variables that include success rate of the anaesthesia (SRA) (if supplementary anaesthesia was used, mepivacaine should be the initial anaesthetic and SRA only stands for the success rate of initial anaesthesia), percentage of patients using analgesics (PPA), onset time of pulpal anaesthesia (OTP), duration of pulpal anaesthesia (DTP) and adverse events (AE).

Exclusion criteria

The following articles were excluded:

-

•

Review articles, cohort studies, and other kinds of studies

-

•

Trials involving participants who were hypersensitive to bupivacaine, levobupivacaine or lidocaine, or were pregnant, lactating, unreliable and unable to return for follow-up

-

•

Trials involving participants who had a history of significant medical conditions, or took any medication that may affect anaesthetic assessment

-

•

Repetitive publication (only the well-described one was included).

Search strategy and study inclusion

Electronic bibliographic sources including Medline (via 1946 to Jan 2013), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Jan 2013), EMBASE (via OVID, 1984 to Jan 2013), Chinese BioMedical Literature Database (1978 to Jan 2013), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, 1994 to Jan 2013) were searched without language limitation. Relevant Chinese- and English-language journals, and the reference sections of the studies included, were hand searched. In order to trace ongoing clinical trials, the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was searched and letters were sent to endodontics specialists.

The search strategy included MeSH and free text words, with the MeSH terms of ‘bupivacaine’, ‘lidocaine’, and ‘Anesthesia, Local’. Search strategies were combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify randomised trials.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool 2011 on the following seven domains: (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel, (4) blinding of outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective reporting and (7) other bias17. Each domain was judged as ‘high risk’, ‘unknown risk’ or ‘low risk’. A single trial was considered as low risk of bias if all the seven domains were judged as ‘low risk’, as ‘moderate risk of bias’ if any item was judged as ‘unknown risk’ and as ‘high risk of bias’ if any item was judged as ‘high risk of bias’.

The reliability of the meta-analysis outcomes was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) on the specified software, GRADEprofiler, and was recorded as high, moderate, low, or very low18.

Data extraction

A customised data extraction form was developed. The following items were included: method of randomisation, concealment and blinding, the number of participants and their demographic data, diagnostic criteria, usage of the solutions and the comparison, anaesthetic technique, dosage of solution, losses to follow-up and the reasons, and outcome details (name of variable and assessment criteria).

Data analysis

Review Manager 5.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was chosen for data analysis. Missing data were analysed if the authors of the initial trials could provide them. Statistical heterogeneity was explored by test for heterogeneity (I2 test) at the level of α = 0.10. If I2 > 50% and P ≤ 0.10, causes of heterogeneity were analysed, subgroup analysis was delivered and a random-effects model was used in the subsequent meta-analysis. If there was no or little heterogeneity (I2 ≤ 50%, P > 0.10), a fixed-effect model was used in the subsequent meta-analysis. The combined results for dichotomous data were expressed as relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs were calculated for continuous data. The statistical significance of the hypothesis test was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed z-tests). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the stability of the results. If the data could not be pooled, they were described. Funnel plots were chosen to detect publication bias if the number of studies included exceeded 10; the asymmetry of a funnel plot would suggest publication bias19., 20.. If crossover or split-mouth trials existed when meta-analysis was made, the carry-over/carry-across effect was first be assessed. If carry-over/carry-across effect was considered a problem, the analysis was based on the first period; if not, we attempted to approximate a paired analysis following the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions 5.1.0. If no crossover or split-mouth designs existed, the first period and second period were mixed and pooled with parallel groups and expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95%CIs21.

RESULTS

Search and study inclusion

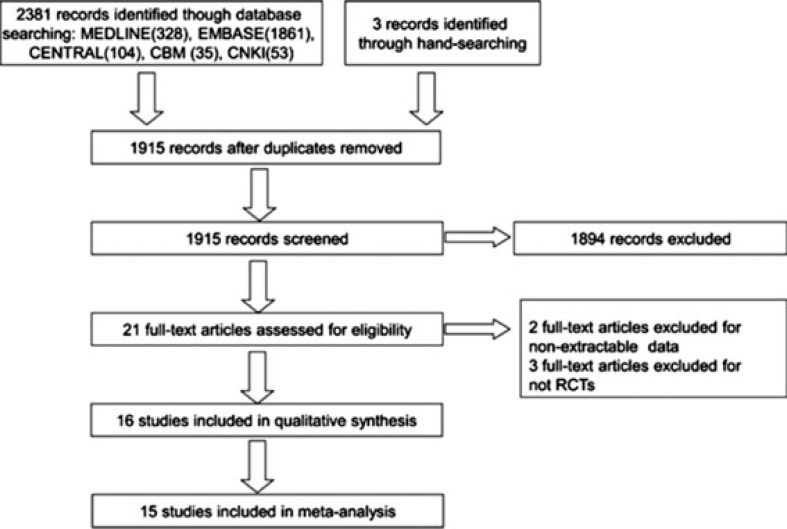

The original electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Chinese BioMedical Literature Database and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure identified 328, 1,861, 104, 35 and 53 potentially eligible articles, respectively. After screening the titles and abstracts, a total of 21 studies were considered eligible and their full texts were retrieved. Finally, five articles were excluded, so the number of studies included was 16, including 13 English-language studies1., 5., 22., 23., 24., 25., 26., 27., 29., 30., 31., 32., 33. and three Chinese-language studies28., 34., 35.(Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion.

Characteristics of the included studies

The 16 studies contained seven parallel designs1., 26., 27., 28., 29., 31., 35. and nine crossover designs5., 22., 23., 24., 25., 30., 32., 33., 34.. None of the nine crossover studies reported the statistics of the first and second periods separately; they could not undergo a paired analysis because of insufficient data. The success of anaesthesia was defined in three studies5., 24., 25. as patients obtaining 80 readings with an electronic pulpal tester (EPT) within a certain period after injection, in three studies29., 31., 32. as patients feeling no pain or mild pain during the treatment by visual analogue scale (VAS) and in three studies27., 28., 35. judged by doctors according to patients’ clinical status and questionnaires. The analgesic tablets patients used included Tylenol,23., 30. ibuprofen,1., 34. noraminophenason22; two studies28., 31. did not provide the exact names. The onset time of pulpal anaesthesia was defined in two studies24., 25. as occurring from the completion of injection to the first of two consecutive 80 readings with an EPT. In two other studies24., 27., 33., the duration of pulpal anaesthesia was defined as occurring from the onset of pulpal anaesthesia to the last of two consecutive 80 readings with EPT. The other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included

| Study | Study design | Country | Sex (male/female) | Age | Methods | Anaesthesia technique | Solution dosage | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linden23 | Crossover | USA | Total 20 | 20–65 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in periodontal surgeries of both maxillary and mandibular regions on separate occasions at least 2 weeks apart | IANB, infiltration, posterior alveolar block and palatal injections | Unclear | PPA |

| Fernandez24 | Crossover | USA | 26/13 | 20–30 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1: 100,000 adrenaline in mandibular teeth on separate occasions at least 1 week apart | IANB | 1.8 ml | SRA, OTP, DTP |

| Gross25 | Crossover | USA | 20/13 | 18–36 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in maxillary teeth on separate occasions at least 1 week apart | Infiltration | 1.8 ml | SRA, OTP |

| Neal26 | Parallel | USA | Totally 62 | Unclear | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in the extraction of third molars | Unclear | Unclear | DTP |

| Moore27 | Parallel | USA | 14/18 | 21–70 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in endodontic therapy | Unclear | Unclear | SRA, DTP |

| Sampaio29 | Parallel | Brazil | Totally 70 | 18–50 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in mandibular molars diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis | IANB | 1.8 ml | SRA |

| Abdulwahab5 | Crossover | USA | 6/12 | 18–53 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in mandibular first molars on separate occasions no shorter than 1 week and no longer than 3 weeks | Infiltration | 0.9 ml | SRA |

| Xu28 | Parallel | China | 17/23 | 20–54 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in both mandibular and maxillary teeth diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis | Unclear | Unclear | SRA, PPA |

| Rood1 | Parallel | UK | 29/64 | 18–41 | Compared 0.75% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline in removal of mandibular impacted molars | IANB & infiltration | 2 ml for IANB and 1 ml for infiltration | PPA, AE |

| Zhou34 | Crossover | China | 16/18 | 19–38 | Compared 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine in removal of mandibular third molars on separate occasions 2 weeks apart | IANB and infiltration | 2 ml for IANB and 1 ml for infiltration | PPA |

| Zhou35 | Parallel | China | 69/51 | 19–58 | Compared 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine in teeth preparation of mandibular regions | IANB | 2 ml | SRA |

| Markovic22 | Crossover | Serbia | Totally 12 | Unclear | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline in removal of lower third molars on separate occasions 14 days apart | IANB | 2 ml | PPA |

| Kaurich30 | Crossover | USA | Totally 10 | 44–70 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in periodontal surgeries of mandibular regions on separate occasions 1 month apart | IANB | Unclear | PPA |

| Danielsson31 | Parallel | Sweden | 149/145 | 18–68 | Compared 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline in removal of mandibular third molars | IANB & infiltration | 3–4 ml | SRA, PPA |

| Danielsson32 | Crossover | Sweden | 14/6 | 18–30 | Compared 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline in oral surgeries of maxillary regions on separate occasions 2 weeks apart | Infiltration | 1 ml | SRA |

| Teplitsky33 | Crossover | Canada | Totally 23 | 22–33 | Compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in both maxillary and mandibular regions | IANB | Unclear | OTP, DTP |

PPA, percentage of patients using analgesics; OTP, onset time of pulpal anesthesia; DTP, duration of pulpal anesthesia; SRA, success rate of the anesthesia; AE, adverse events; IANB, inferior alveolar nerve block.

Risk of bias of the included studies

Among the studies included, nine had a low risk of bias5., 23., 24., 25., 27., 29., 30., 31., 32., six had a moderate risk of bias1., 22., 28., 33., 34., 35. and one had a high risk of bias26 because single blinding was used and the outcome was likely to be influenced by incomplete blinding in that study. We excluded this last study from meta-analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of the studies included

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Risk of bias of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linden23 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Fernandez24 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Gross25 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Neal26 | U | U | H | U | L | L | U | H |

| Moore27 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Sampaio29 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Abdulwahab5 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Xu28 | U | U | U | U | L | U | U | M |

| Rood1 | L | U | L | L | L | L | U | M |

| Zhou34 | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | M |

| Zhou35 | U | U | L | U | U | U | U | M |

| Markovic22 | U | L | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Kaurich30 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Danielsson31 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Danielsson32 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Teplitsky33 | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | M |

L, low risk of bias; U, unknown risk of bias; H, high risk of bias; M, moderate risk of bias.

Efficacy and safety of mepivacaine compared to lidocaine

Success rate

0.5% Bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline versus 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline

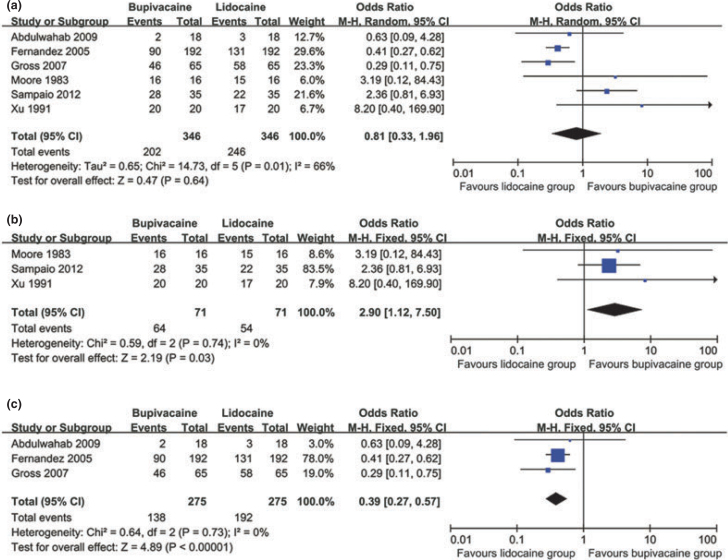

Six studies5., 24., 25., 27., 28., 29. compared 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline and 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline. The outcome of meta-analysis showed no statistical significance between the two groups (OR 0.81; 95%CI 0.33–1.96; P = 0.64) in success rate of local anaesthesia (Figure 2a). When the condition of pulp was considered, three studies27., 28., 29. containing inflamed pulp only were pooled and the outcome showed that the bupivacaine group was superior to the lidocaine group in success rate assessed by VAS or patients’ feelings and expressions during treatment (OR 2.90; 95%CI 1.12–7.50; P = 0.03) (Figure 2b). The other three studies5., 24., 25. containing vital pulp were pooled and the outcome showed that the bupivacaine group was inferior to the lidocaine group assessed by EPT (OR, 0.39; 95%CI, 0.27–0.57; P < 0.00001) (Figure 2c). The GRADE showed that the reliability of this outcome was moderate.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis comparing 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in success rate of overall (a), inflamed pulp (b) and vital pulp (c) in local anaesthesia in dentistry.

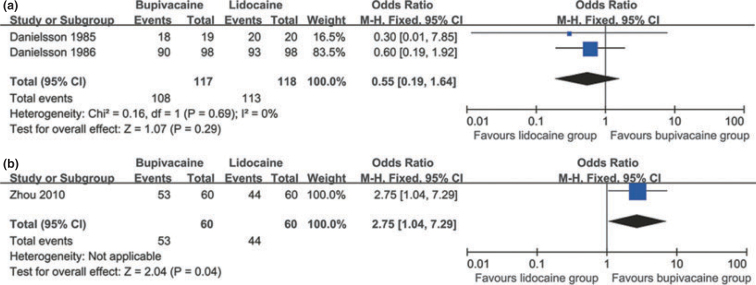

0.75% Bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline versus 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline

The pooled outcome from two studies31., 32. showed that there was no statistical significant between the two groups in success rate of vital pulp (OR 0.55; 95%CI 0.19–1.64; P = 0.29). (Figure 3a)

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis comparing 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1: 200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline (a) and 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine (b) in success rate of local anaesthesia in dentistry.

0.5% levobupivacaine versus 2% lidocaine

Only one study35 compared 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine and the outcome showed that the former was superior to the latter in success rate of vital pulp (OR 2.75; 95%CI 1.04–7.29; P = 0.04). (Figure 3b)

Percentage of patients using postoperative analgesics

The pooled outcome from four studies22., 23., 28., 30. showed that PPA in the 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline was lower than that in the 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline (OR 0.27; 95%CI 0.12–0.64; P = 0.003) (Figure 4a). The GRADE showed that the reliability of this outcome was moderate. The PPA for 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline was lower than that for 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline (OR 0.32; 95%CI 0.16–0.63; P = 0.001) when one study31 was considered (Figure 4b). There was no statistical significance in PPA when comparing 0.75% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline (OR 0.47; 95%CI 0.16–1.34; P = 0.16) when one study1 was considered (Figure 4c). In addition, the PPA was lower in 0.5% levobupivacaine compared with 2% lidocaine34 (OR 0.11; 95%CI 0.03–0.43; P = 0.001) (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis in percentage of patients using postoperative analgesic tablets (PPA) in dentistry comparing 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline (a), 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline (b), 0.75% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline (c) and 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine (d).

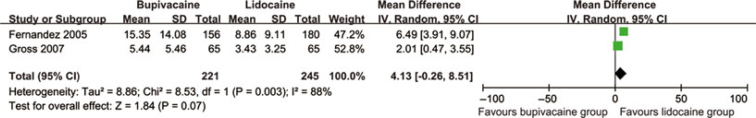

Onset time of pulpal anaesthesia (OTP)

The pooled outcome from two studies24., 25. demonstrated no statistical significance between 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline and 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in terms of onset time of pulpal anaesthesia (MD 4.13; 95%CI −0.26–8.51; P = 0.07) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis comparing 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in onset time of pulpal anesthesia (OTP).

When tooth sites were taken into consideration, the outcomes showed that the bupivacaine group had a longer onset time of pulpal anaesthesia than the lidocaine group in either mandibular region or maxillary region (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis outcomes of onset time of pulpal anesthesia in different region

| Teeth sites | Mean difference (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Mandibular region | 6.49 (3.91–9.07) | <0.00001 |

| Maxillary region | 2.01 (0.47–3.55) | 0.01 |

Duration time of pulpal anaesthesia (DTP)

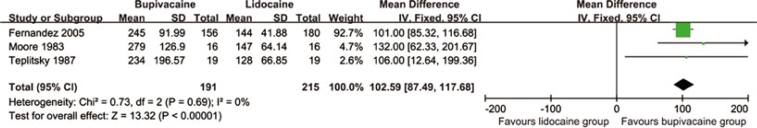

The pooled outcome from three studies24., 27., 33. demonstrated that 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline had a longer duration time of pulpal anaesthesia than that of 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline (MD 102.59; 95%CI 87.49–117.68; P < 0.00001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis comparing 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1: 200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in duration time of pulpal anesthesia (DTP)

Adverse events

Two studies reported adverse events1., 23.. The outcome showed no statistical significance between 0.75% levobupivacaine and 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline or between 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline and 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in terms of adverse events (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage, number and odds ratio of subjects who experienced post-injection side effects

| Adverse events | Studies included | Percentage and number of events in bupivacaine group | Percentage and number of events in lidocaine group | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | Linden23 | 55 (11/20) | Unclear | – | – |

| Nausea, abdominal discomfort, dizziness and feeling faint | Rood1 | 7 (2/29) | 23 (7/30) | 0.24 (0.05 1.29) | 0.10 |

DISCUSSION

In clinical use, bupivacaine is available as a 0.5% solution plus 1:200,000 adrenaline in dentistry7. When the success rate of local anaesthesia in dentistry was considered, the meta-analysis results showed that 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline might be superior to 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in inflamed pulp assessed by VAS or patients’ feelings and expressions during dental treatment but inferior to 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline in vital pulp assessed by EPT.

The use of the 80-μA reading EPT is a criterion for pulpal anesthesia36., 37., and no patient response to an 80-μA reading ensures pulpal anaesthesia in vital asymptomatic teeth. In our study, we focused on trials in which researchers evaluated the presence or absence of pulpal anaesthesia by using EPT, VAS and patients’ feelings and expressions. As for teeth with vital pulp anaesthetic success is often defined as the percentage of participants who achieve two consecutive EPT readings of 80 within 15 minutes of administration of anaesthetic and sustain this lack of responsiveness continuously for 60 minutes. However, for symptomatic teeth, a lack of response to EPT may not guarantee that a tooth is experiencing profound pulpal anaesthesia and what really matters is that the patients do not suffer from unbearable pain during the treatment. Therefore, VAS and the patients’ feelings and expressions during the treatment were used to evaluate the anaesthetic success.

However, there was a disparity between inflamed pulp and vital pulpal in success rate from the meta-analysis when comparing bupivacaine and lidocaine. One possible reason for this disparity might be the complex mechanism of neuroinflammatory and neuropulpal interactions such as odontoblast interactions occurring in inflamed pulp, which is different in vital pulp38. Thus, bupivacaine, which had lower success rate in vital pulp, had higher success rate in inflamed pulp. However, this is not yet clear38. Another possible reason for the disparity might be that bupivacaine, as a long-acting local anaesthetic, had a longer time for pain control than lidocaine. Dental treatments such as pulpectomy take a relatively long time, and bupivacaine thus has an advantage over lidocaine in pain control in this situation. Another possible reason might be that EPT was not a reliable indicator for actual analgesia and was not always accurate39. Therefore, how patients really feel was a better indicator of success.

Furthermore, from the meta-analysis, 0.5% levobupivacaine had a higher success rate than 2% lidocaine. Levobupivacaine, which was considered in the early 1970s was proven to be less toxic, both intravenously and subcutaneously, than bupivacaine in mouse, rat and rabbit without any apparent loss of local anaesthetic potency6. Later, levobupivacaine was proven safer than bupivacaine but had a similar efficacy1. Levobupivacaine is always supplied as a 0.75% or 0.5% solution in dentistry, but these were not recommended concentrations in dentistry until now.

The time of onset of anaesthesia is directly related to the rate of epineural diffusion correlated with the percentage of drug in the base form which is proportional to the pKa of that agent40. The outcome of meta-analysis shows the 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline might have longer onset time compared with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline both in mandibular and maxillary regions. The pKa is 8.1 for bupivacaine but is 7.9 for lidocaine, therefore, bupivacaine had longer onset time of pulpal anaesthesia than lidocaine. According to the literature, the onset time is 5–8 minutes for bupivacaine but 2–4 minutes for lidocaine40. In addition, the protein-binding abilities of local anaesthetic agents primarily influence the anaesthetic duration of action41. The outcome of meta-analysis indicated that 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline had a longer duration of pulpal anaesthesia than 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline, probably because bupivacaine was more highly protein bound (95%) than lidocaine (65%)41. According to Malamed7, the durations of pulpal anaesthesia and soft tissue anaesthesia were 90–180 minutes and 240–540 minutes, respectively, for 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline, but were 60 minutes and 180–300 minutes, respectively, for 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline.

Postoperative pain is a common phenomenon after surgery as a result of surgical trauma and the release of pain mediators, therefore postoperative pain control is an essential part of routine oral surgical procedures42., 43.. It has already been proven that the painless postoperative period can be significantly prolonged if long-acting local anaesthetics are used44. The outcomes of meta-analyses in our study indicate that the percentage of patients using postoperative analgesic tablets was is lower when comparing 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline, 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline and 0.5% levobupivacaine with 2% lidocaine, probably because the bupivacaine group has a longer duration of anaesthesia than the lidocaine group, thus bupivacaine can relieve pain and discomfort for a longer time than lidocaine. However, the 0.75% levobupivacaine group had a lower percentage of patients using postoperative analgesic tablets than the group given 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline and this might be because of an insufficient number of subjects included in the study and the absence of adrenaline in levobupivacaine.

In terms of adverse events, the toxicity of bupivacaine is less than one-fourth that of lidocaine7. Bupivacaine is thought to be less safe than other long-acting local anaesthetics, especially with regard to cardiac toxicity, mainly because bupivacaine showed a high potential for accumulation in the sodium channel, as it entered rapidly during the action potential but exited slowly during recovery6. Thus, the accentuation of bupivacaine cardiotoxicity must also be considered in patients taking chronic medications that depress cardiac function, such as beta blockers, calcium channel45 and cardiac glycosides46. Levobupivacaine is considered to be safer than bupivacaine on both animal and human trials1., 6.. Lidocaine may have cardiac toxicity, which is uncommon at clinical used doses; however, it has anticonvulsant actions at low doses and proconvulsant actions at high doses6. The results showed no statistical significance between bupivacaine or levobupivacaine and lidocaine, probably because of the limited sample size and the small number of randomised controlled trials reporting adverse events when comparing bupivacaine and lidocaine.

In clinical use, bupivacaine and levobupivacaine is recommended for use in lengthy dental procedures for which pulpal anaesthesia in excess of 90 minutes is required, especially for endodontic treatment and management of postoperative pain. It is not recommended in younger patients or in those where the risk of postoperative soft tissue injury produced by self-mutilation is increased, such as in physically and mentally disabled persons. It is seldom used in children because paediatric dental procedures are usually of short duration7.

Unfortunately, this review is not free of limitations. Although the articles acquired had highly reliable outcomes, there was still some bias in the reviewing process. The consistency of results across studies and the precision of the pooled data will affect the strength of inference from systematic reviews considerably. The number of studies included in some meta-analyses was small, which might yield bias in the outcomes. Furthermore, selection bias could not be avoided completely, and is a problem faced by all systematic reviews. Parallel trials and crossover trials were mixed together in meta-analysis because of imperfect reporting data in the studies, which might cause deviation in the outcome. The reviewers searched electronic databases and ongoing studies databases; hand-searching was also done which could help restrict such bias. Clinical heterogeneity among the studies could not be fully avoided and the number of participants included in each study was small, thus lacking statistical power. The low diversity of the studies, the small sample size and the unexplained statistical heterogeneity limit the overall conclusions and call for further studies to obtain more stable outcomes.

We expect more higher-quality studies comparing bupivacaine plus adrenaline, or levobupivacaine plus adrenaline with lidocaine plus adrenaline to further evaluate the efficacy of the two solutions. We also expect more research exploring the difference in mechanisms of inflamed pulp and vital pulp in local anaesthesia. We also expect more systematic trials on adverse events between the two solutions to further evaluate their safety.

A summary of the clinical evidence concludes that in comparison with 2% lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline, 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline had a higher success rate of local anesthesia in inflamed pulp but a lower success rate in vital pulp, longer onset time of pulpal anaesthesia, longer duration of pulpal anaesthesia and was superior in postinjection pain control. In comparison with 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline, 0.75% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline had the same level of success rate, and was better in postoperative pain control. In addition, 0.75% levobupivacaine was similar to 2% lidocaine plus 1:80,000 adrenaline in postoperative pain control. Further, 0.5% levobupivacaine had a higher success rate and was better in postoperative pain control than 2% lidocaine. No evidence could be found to conclude that bupivacaine was less safe than lidocaine. In conclusion, given the efficacy and safety of the two solutions, the bupivacaine group is better than the lidocaine group for use in dental operations that would take a relatively long time, especially in endodontic treatments and where there is a need for postoperative pain management.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rood JP, Coulthard P, Snowdon AT, et al. Safety and efficacy of levobupivacaine for postoperative pain relief after the surgical removal of impacted third molar: a comparison with lidocaine and adrenaline. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(02)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peretz B, Moshonov J. Dental anxiety among patients undergoing endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1998;24:435–437. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstein J, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patient with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2004;30:568–571. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000125317.21892.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J, et al. Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:101–107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdulwahab M, Boynes S, Moore P, et al. The efficacy of six local anesthetic formulations used for posterior mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1018–1024. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox B, Durieux ME, Marcus MA. Toxicity of local anesthetics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17:111–136. doi: 10.1053/bean.2003.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malamed SF. In: Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 6th edn. Malamed SF, editor. Mosby; Chicago: 2012. Clinical action of specific agents; pp. 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt RG, Anderson PF, McDonald NJ, et al. The pulpal anesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:493–504. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffen AS, Haas DA. Survey of local anesthetic use by Ontario dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore PA, Nahouraii HS, Zovko JG, et al. Dental therapeutic practice patterns in the U. S. I. anesthesia and sedation. Gen Dent. 2006;54:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sisk AL, Dionne RA, Wirdzek PR. Evaluation of etidocaine hydrochloride for local anesthesia and postoperative pain control in oral surgeries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:84–88. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poorni S, Veniashok B, Senthikumar AD. Anesthetic efficacy of four percent articaine for pulpal anesthesia by using inferior alveolar nerve block and buccal infiltration techniques in patients with irreversible pulpitis: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Endod. 2011;37:1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sisk AL. Long-acting local anesthetics in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1992;39:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mather LE. Disposition of mepivacaine and bupivacaine enantiomers in sheep. Br J Anaesth. 1991;67:239–246. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox CR, Faccenda KA, Gilhooly C, et al. Extradural S(–)-bupivacaine-comparison with racemic RS-bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:289–293. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardsley H, Gristwood R, Baker H, et al. A comparison of the cardiovascular effects of levobupivacaine and rac-bupivacaine following intravenous administration to healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:245–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green S. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0 Version. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, editors. John Wiley& Sons; Chichester: 2011. Assessing risk of bias in included studies; pp. 182–234. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0 Version. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 2011. Addressing reporting biases; pp. 279–311. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0 Version. Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, editors. John Wiley& Sons; Chichester: 2011. Special topics in statistics; pp. 429–467. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markovic AB, Todorovic L. Postoperative analgesia after lower third molar surgery: contribution of the use of long-acting local anesthetics, low-power laser, and diclofenac. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e4–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linden ET, Abrams H, Matheny J, et al. A comparison of postoperative pain experience pain following periodontal surgery using two local anesthetic agents. J Periodontol. 1986;57:637–642. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.10.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez C, Reader A, Beck M, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bupivacaine and lidocaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Endod. 2005;31:499–503. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000167395.61075.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross R, McCartney M, Reader A, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bupivacaine and lidocaine for maxillary infiltration. J Endod. 2007;33:1021–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neal JA, Welch TB, Halliday RW. Analysis of the analgesic efficacy and cost-effective use of long-acting local anesthetics in outpatient third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:283–285. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90136-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore PA, Dunsky J, Mass B. Bupivacaine anesthesia – a clinical trial for endodontic therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:176–179. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu SS, Qian CH. Clinical research of bupivacaine in endodontic treatment. J Comprehensive Stomatol. 1991;7:113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sampaio RM, Carnaval TG, Lanfredi CB, et al. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy between bupivacaine and lidocaine in patients with irreversible pulpits of mandibular molar. J Endod. 2012;38:594–597. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaurich M, Otomo-Corgel J, Nagy RJ. Comparison of postoperative bupivacaine with lidocaine on pain and analgesic use of following periodontal surgery. J West Soc Periodontol Periodontal Abstr. 1997;45:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danielsson K, Evers H, Holmlund A, et al. Long-acting local anesthetics in oral surgery: clinical evaluation of bupivacaine and etidocaine for mandibular nerve block. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(86)80131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danielsson K, Evers H, Nordenram A. Long-acting local anesthetics in oral surgery: an experimental evaluation of bupivacaine and etidocaine for oral infiltration anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 1985;32:65–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teplitsky PE, Hablichek CA, Kushneriuk JS. A comparison of bupivacaine to lidocaine with respect to duration in the maxilla and mandible. J Can Dent Assoc. 1987;53:475–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou XD, Lv J, Chen ZL, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of levobupivacaine for surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molar and postoperative pain control. Med J Chin Peoples Armed Police Forces. 2011;22:305–307. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou XD, Zhao WF, Lv J, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of levobupivacaine for teeth preparation of vital pulp. J Clin Stomatol. 2010;26:630–631. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dreven LJ, Reader A, Beck M, et al. An evaluation of an electric pulp tester as a measure of analgesia in human vital teeth. J Endod. 1987;13:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(87)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gertosimo AJ, Archer RD. A clinical evaluation of the electric pulp tester as an indicator of local anesthesia. Oper Dent. 1996;21:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hargreaves KM, Goodis HE, Seltzer S. 1st edn. Quintessence Pub Co Inc; Chicago: 2002. Seltzer and Bender’s Dental Pulp; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooley RL, Stillry J, Lubow RM. Evaluation of a digital pulptester. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Truant AP, Takman B. Different physical–chemical and neuropharmacological properties of local anesthetic agents. Anesth Analg. 1959;38:478–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covino BG. Physiology and pharmacology of local anesthetic agents. Anesth Prog. 1981;28:98–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seymour RA, Walton JG. Pain control after third molar surgery. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:457–485. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro RD, Cohen BH. Perioperative pain control. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1992;4:663–674. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caruso JM, Brokaw WC, Blanton EE. Bupivacaine and lidocaine compared for postoperative pain control. Gen Dent. 1989;37:148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adsan H, Tulunay M, Onaran O. The effect of verapamil and nimodipine on bupivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity in rats: an in vivo and in vitro study. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:818–824. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roitman K, Sprung J, Wallace M. Enhancement of bupivacaine cardiotoxicity with cardiac glycosides and beta-adrenergic blockers: a case report. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:658–661. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199303000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]