Abstract

Background:

Childhood maltreatment has been associated with suicide thoughts and attempts; however, few longitudinal studies have assessed risk of suicidality into adulthood. Fewer have examined potential mediators (psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors).

Methods:

Prospective cohort design. Children with documented cases of maltreatment (N = 495, ages 0–11) were matched with non-maltreated children (N = 395) and followed up into adulthood. Psychiatric symptoms (depression, anxiety, dysthymia, post-traumatic stress, antisocial personality, and substance use) and environmental vulnerability (social isolation, physical disability/illness, and homelessness) were assessed at mean age 29 and suicide thoughts and attempts at 39. Structural equation models tested for mediation, controlling for age, sex, race, and IQ.

Results:

Childhood maltreatment predicted suicide attempts (Beta = .44, p<.001), but not suicide thoughts only. Individuals with only suicide thoughts differed significantly from those with suicide attempts in psychiatric symptoms, physical disability/ illness, and homelessness. There were significant paths from child maltreatment to suicide attempts through psychiatric symptoms (0.18, p<.001), ASPD (0.13, p<.001), substance use (0.07, p<.01), and homelessness (.10, p<.05).

Limitations:

Court cases of child maltreatment may not generalize to middle- or upper- class and non-reported cases. Effect sizes were small but significant.

Conclusions:

Psychiatric risk factors for suicide are well recognized. These new results provide strong evidence that environmental vulnerability factors, particularly homelessness, are associated with increased risk for suicide attempts and warrant attention. Although many people report suicide thoughts, maltreated children with more psychiatric symptoms and experience homelessness are more likely to attempt suicide and warrant targeted interventions.

1. Introduction

Suicide is a major public health concern and the 10th leading cause of death overall in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Based on community surveys, the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts is estimated to be 3%, whereas for suicidal thoughts it is 9% (Nock et al., 2008). Research has identified psychiatric risk factors for suicidal thoughts and attempts, including depression (Bolton and Robinson, 2010; Chabrol et al., 2007), anxiety (Fawcett et al., 1990; Mannuzza et al., 1992; Ohring et al., 1996; Sareen et al., 2005), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bolton and Robinson, 2010; Krysinska and Lester, 2010), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) (Ansell et al., 2015; Black, 2015; Goodwin and Hamilton, 2003), alcohol use (Boenisch et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2019; Darvishi et al., 2015; Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2009; Sher et al., 2009; Wilcox et al., 2004), and drug use (Artenie et al., 2015; Ashrafioun et al., 2017; Kazour et al., 2016; Marshall et al., 2011; Poorolajal et al., 2016; Youssef et al., 2016). In a meta-analysis of studies looking at proximal risk factors for suicide deaths, mood and drug use disorders were associated with 7–9 times increased risk (Conner et al., 2019). A recent study by Gobbi et al. (2019) shows that cannabis use during adolescence is associated with greater risk of depression, anxiety and suicidality in young adults.

A separate literature has focused on environmental vulnerability factors, including physical illness or health problems (Choi et al., 2019; Epstein and Spirito, 2009; Waern et al., 2002), functional impairment (Conwell et al., 2009), social isolation, and homelessness. Two systematic reviews found that social isolation is a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and attempts, although more studies have focused on adolescents and/or young adults (Calati et al., 2019; Hall-Lande et al., 2007) than adults ages 65 and older (Fassberg et al., 2012; Turvey et al., 2002). Calati et al. (2019) pointed out a number of confounding factors that need consideration when studying the role of social isolation, including abuse/life events, psychiatric disorders, alcohol/drugs, and medical conditions, among others. Higher rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts have also been associated with homelessness, although many studies are based on specialized samples, e.g., shelter users (Eynan et al., 2002), clinical samples of people with mental illnesses (Desai et al., 2003), or veterans (e.g., Schinka et al., 2012). In a recent review and meta-analysis of studies of suicidal ideation and attempts among homeless people, Ayano et al. (2019) found that the pooled current and lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was 17.8% and 41.6% and suicide attempts was 9.2% and 28.8%, respectively, substantially higher than estimates for the general population (Nock et al., 2008).

Childhood maltreatment has also been associated with suicidal thoughts and behavior (Friestad et al., 2014; Harford et al., 2014; Jeon et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2012) and psychiatric disorders in adulthood, including depression, anxiety, PTSD (Gilbert et al., 2009; Lindert et al., 2014; Widom, 1999; Widom et al., 2007), ASPD (Luntz and Widom, 1994; Widom, 1998), and environmental vulnerability factors (Algood et al., 2011; Coohey, 1996; Danese et al., 2009; Kendall-Tackett, 2002; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2017; Sullivan and Knutson, 2000; Sundin and Baguley, 2015). Thus, the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and attempts may be explained by two potential pathways through psychiatric disorders and environmental vulnerabilities. Although research has shown that various forms of psychopathology predict suicidality and different forms of psychiatric disorders and environmental vulnerabilities are outcomes frequently associated with childhood maltreatment, the role of these factors as mediators between childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and behaviors has infrequently been examined. In cross-sectional studies, researchers have examined anxiety, depression, and PTSD as potential mediators of the association between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation (Bahk et al., 2017; Lee, 2015; Lopez-Castroman et al., 2015) and a few longitudinal studies have examined relationships among childhood maltreatment, depression and suicidality (Brezo et al., 2008; Brown et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2014; Sachs-Ericsson, 2017; Thompson et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2012). Using data from the National Comorbidity Study (NCS), Sachs-Ericsson et al. (2017) found that the number of NCS2 DSM disorders served as an indirect pathway from non-violent child abuse to suicide attempts during a 10-year follow-up.

A frequently noted limitation of the existing literature is its heavy reliance on cross-sectional studies (Albanese et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2019; Sommer et al., 2019; Wetherall et al., 2018), which make attributions of causality difficult. In their review of studies on the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior, Miller et al. (2013, p. 163) concluded: “There also exists a clear need for longitudinal, prospective studies that compare large samples of youth with and without a CM (child maltreatment) history, to better understand developmental differences that may precipitate suicidal behavior.” A second limitation is that most of the studies rely on retrospective self-reports of childhood maltreatment or reports by proxies in psychological autopsy studies, which are open to recall bias. Third, although theories of suicide discuss different pathways for suicide attempts and suicide thoughts, two recent papers have pointed out the dearth of information about factors that differentiate the two groups (Albanese et al., 2019; Wetherall et al., 2018). To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to systematically examine psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors in a comprehensive model and to overcome many of the limitations of prior work.

1.1. Current study

Using a prospective cohort design, the current study examines whether childhood maltreatment is associated with increased risk for suicide in adulthood, whether psychiatric symptoms or environmental vulnerability factors mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidality, and whether individuals who make suicide attempts and those with suicidal thoughts only represent a single or discrete groups. We take advantage of a unique data set from a study of a large group of children with documented cases of childhood maltreatment and a matched control group without such histories who have been followed up into middle adulthood and assessed on multiple occasions. We focus on four major questions: (1) Do children with documented histories of maltreatment report more suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in later life, compared to matched controls? (2) Do individuals who report suicide attempts differ from those who report suicidal thoughts only in terms of psychiatric symptoms and environmental risk factors? (3) Do either psychiatric disorders (depression, dysthymia, anxiety, PTSD, ASPD, and substance use) in young adulthood or environmental vulnerability factors (social isolation, physical illness and disability, and homelessness) explain the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and attempts? (4) Does a combined model with psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors better explain the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and attempts in middle adulthood compared to models with only psychiatric symptoms or environmental vulnerability factors?

2. Method

2.1. Design and Participants

This prospective cohort design study (Leventhal, 1982; Schulsinger et al., 1981) was initiated in 1986 with a large group of documented cases of childhood maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse and neglect) (N = 908) and a comparison group of children matched on the basis of age, sex, race/ethnicity, and approximate family social class at the time of the childhood maltreatment (N = 667) (Widom, 1989a). Because of the matching procedure, the subjects are assumed to differ only in the risk factor; that is, having experienced childhood maltreatment. Since it is not possible to assign subjects randomly to groups, the assumption of equivalency for the groups is an approximation. The control group may also differ from the maltreated individuals on other variables nested with maltreatment, for example, parent history of psychiatric disorders or inherited characteristics. Characteristics of the design include: (1) an unambiguous operationalization of maltreatment; (2) a prospective design; (3) a large sample; (4) a comparison group matched as closely as possible for age, sex, race and approximate social class background; and (5) assessment of the long-term consequences of maltreatment beyond childhood and adolescence into adulthood.

The rationale for identifying the maltreated group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases of child abuse and neglect were included here. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971. To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that temporal sequence was clear (that is, child neglect or abuse led to subsequent outcomes), maltreatment cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Thus, these are cases of childhood abuse and/or neglect. These design characteristics represent major strengths, but they also pose limitations about the generalizability of the findings.

A critical element of the design involved the selection of a matched control group of children without documented histories of childhood maltreatment (N = 667). This matching was important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between childhood maltreatment and subsequent outcomes is confounded with or explained by social class differences (Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; Conroy et al., 2010; MacMillan et al., 2001; Widom, 1989b). The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Similar procedures, with neighborhood school matches, have been used in studies of people with schizophrenia (e.g., Watt, 1972) to match approximately for social class. When random sampling is not possible, Shadish, Cook, and Campbell (2002) recommend using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes. The control group establishes the base rates of health outcomes expected in a sample of adults from comparable circumstances who did not come to court attention in childhood as victims of maltreatment.

To accomplish the matching, the abused and neglected children were divided into two groups, those under and those of school age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Using county birth record information, children under school age were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 1 week), and hospital of birth. Of the 319 abused and neglected cases, matches were found for 229 (72%) of the group. Children of school age were matched as closely as possible by sex, race, date of birth (+/− six months), and class in the elementary school system during 1967 through 1971. Records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches. Busing was not operational at this time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socioeconomically homogeneous neighborhoods. Matches were never made with students from another school, although it was sometimes necessary to select students from different classes or even different grades in the same school. Where an abused or neglected child had been held back a grade, resulting in a discrepancy between the child’s age and grade, the match was made on the basis of age. Where a child had attended special education classes during the period, attempts were made to include matches from such classes. Of the 589 school-age children in the abuse and neglect group, we found matches for 438 or 74% of the abused and neglected children.

Although the goal was to have 1:1 matching, non-matches occurred for a number of reasons. In the case of birth records, they occurred if the abused or neglected child was born outside the county or state, or if information about the date of birth was missing. In the case of school records, non-matches occurred because the elementary school had closed during the years since 1971 and class registers were consequently not available, or because schools had been primarily uniracial (they were not necessarily integrated at the time) and a same race match could not be found.

As part of the procedure used to select the control group children, official records were checked and any candidate comparison group child who had an official record of maltreatment in their childhood (N = 11) was eliminated and a second match was assigned to the comparison group to replace the individual excluded. Thus, the control group does not contain any known cases of child abuse or neglect. The number of participants in the comparison group who were actually abused or neglected, but not reported, is unknown.

The initial phase of the study compared the maltreated children to the matched comparison group (total N = 1,575) on arrest records (Widom, 1989b). The second phase of the study involved tracking, locating, and interviewing both groups during 1989–1995, approximately 22 years after the incidents of childhood maltreatment (N = 1,196, 76%). Another follow-up interview was conducted during 2000–2002 (N = 890, 74% of those previously interviewed). To summarize the design:

Court substantiated cases of child maltreatment and matched controls (ages 0–11) ➔

In-person interview 1 (mean age 29) ➔ In-person interview 2 (mean age 39)

Although there was attrition associated with death, refusals, and our inability to locate individuals over the various waves of the study, the composition of the sample at the three time points has remained about the same. The maltreatment group represented 56–58% at each time period; White, non-Hispanics were 62–66%; and males were 48–51% of the samples. There were no significant differences across the samples on these variables or in mean age across the phases of the study. Re-analyses of earlier findings were conducted using only matched pairs and the results did not change with the smaller sample size (Currie and Widom, 2010; Widom, 1989b; Widom et al., 2007).

The sample was mean age 29.23 (standard deviation (SD) = 3.84, range 18.95–40.70), 51.0% male, 61.5% White, non-Hispanic, and 38.5% Black, not of Hispanic origin, and 3.8% Hispanic (based on self-reports) at the time of the first interview (1989–1995). At the second interview in 2000–2002, the sample was mean age 39.0 (SD = 3.49, range 30–47), 48.9% male, 60.8% White, non-Hispanic, and 32.6% Black, non-Hispanic and other races.

2.2. Procedures

Two-hour in-person interviews that included a series of structured and semi-structured questionnaires and rating scales were conducted between 1989 and 1995 obtaining information about cognitive, intellectual, emotional, psychiatric, social and interpersonal functioning. The interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the participants’ group membership, and to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group. Participants were also blind to the purpose of the study and were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in that area during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and participants were provided written, informed consent. For individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was presented and explained verbally.

2.3. Measures and Variables

2.3.1. Childhood maltreatment.

Childhood maltreatment information was obtained from court records in a Midwestern metropolitan county area. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, and bone and skull fractures. Sexual abuse cases included felony sexual assault, fondling or touching, sodomy, incest, and rape. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents’ deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time and represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. Childhood maltreatment here is treated as a binary variable reflecting whether the person had experienced any type of documented maltreatment described above.

2.3.2. Interview 1: 1989–1995

2.3.2.1. Psychiatric disorders.

Psychiatric disorders were assessed during interviews between 1989–1995 (mean age= 29.23 years) according to DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III Revised (DIS-III-R) (Robins et al., 1989), a highly structured interview schedule designed for use by lay interviewers. Adequate reliability for the DIS-III has been reported (Helzer et al., 1985). The survey company who conducted the Epidemiological Catchment Area studies (W. W. Eaton et al., 1981) was hired to conduct the interviews. Field interviewers received a week of study-specific training and successfully completed practice interviews before beginning the study interviews. Field interviewer supervisors recontacted a random 10% of the respondents for quality control. Frequent contacts between field interviewers and supervisors were held to prevent interview drift, to monitor quality, and to provide continuous feedback. Computer programs were used for scoring the DIS-III-R and provided a count of the number of symptoms for each psychiatric disorder, including: major depressive disorder, dysthymia (a mood disorder characterized by chronic mildly depressed or irritable mood), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), and substance use. The number of lifetime symptoms was used for each disorder. Substance use represents the sum of symptoms for alcohol and drugs.

2.3.2.2. Social isolation (Kulka et al., 1990).

Respondents were asked a series of questions about the extent of their participation in social activities, including how often they got together with family members, other people for a hobby or leisure activities, close friends, and neighbors, or to attend a church, synagogue, or prayer group. For each question, there were eight possible response options: daily, several times per week, once per week, several times per month, once per month, several times per year, once a year or less, and never. Responses were coded 1 if the participant indicated that they never participated in that activity, all others were coded 0. In addition, they were asked whether they were married/living with someone (0) or not (1). Social isolation was the sum of these items.

2.3.2.3. Physical disability or illness.

This factor was based on (1) responses to a question about whether the participant had a serious physical illness or injury requiring hospital treatment in the past year, coded 1 = yes, and 0 = no, and (2) information recorded at the end of the interview about whether the participant had any of the following conditions, including grossly obese, very thin, skeleton-like, speech impediment, crippled, other apparent illness, disfigurements, blind, or deaf. If the interviewer indicated that the person had some physical disability, each was coded 1, otherwise it was coded 0. These scores were summed to create the variable.

2.3.2.4. Homelessness.

Homelessness was assessed during the first interview by asking participants if they had ever been homeless for at least a month or so. Responses were 1 = yes, 0 = no.

2.3.3. Interview 2: 2000–2002

Suicidal thoughts and attempts.

For suicidal thoughts, participants were asked two questions: Has there ever been a period of two weeks or more when you felt like you wanted to die? Have you ever felt so low that you thought about committing suicide? If either of these responses was yes and the participant answered no to the suicide attempt question, then those who had only thoughts but no attempts were coded as 1. For suicide attempts, participants were asked whether they had ever attempted suicide and coded 1 if yes and 0 if no, regardless of whether they reported having suicidal thoughts. Using this scoring procedure, 90% of the 147 individuals who reported having made a suicide attempt reported suicidal thoughts as well. An additional 186 individuals reported suicidal thoughts but no suicide attempt.

2.3.4. Control variables

All analyses controlled for age, sex, race, and IQ. IQ was controlled because previous research has shown that maltreatment is associated with reduced IQ (Perez and Widom, 1994). IQ was measured by the Quick Test (Ammons and Ammons, 1962), an easily administered measure of verbal intelligence that correlates highly with WAIS full scale (.79-.80) and verbal (.79-.86) IQs (Dizzone and Davis, 1973). The normed Quick Test has an average normed score of 100 (SD = 10) and in the current sample: Control: M = 94; Maltreated: M = 87. It has been successfully used with ethnically diverse samples (Vance et al., 1988) and has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Joesting and Joesting, 1972; Zagar et al., 2013).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The first step in the analyses was to conduct basic descriptive statistics to examine characteristics of the maltreated and control groups and characteristics of individuals grouped by suicidality status. T-tests and ANOVAs were used for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables. Post hoc comparisons were made using the Tukey test or Bonferroni corrections to control for type I error.

In order to reduce potential bias associated with attrition from interview 1 to interview 2, multiple imputation (White et al., 2011) was used to handle missing data. The group variable (maltreated versus control), age, sex, race, IQ, psychiatric symptoms, environmental vulnerability factors, and whether the person had died in-between the two interviews were included in the predictive mean modeling algorithm for multiple imputation by chained equations. Only variables that were correlated with the target variable (r > 0.1) were included as a predictor. The imputation was repeated 20 times and imputed datasets were used for further analysis. Rubin’s (1987) rules were used to combine estimates from the imputed datasets.

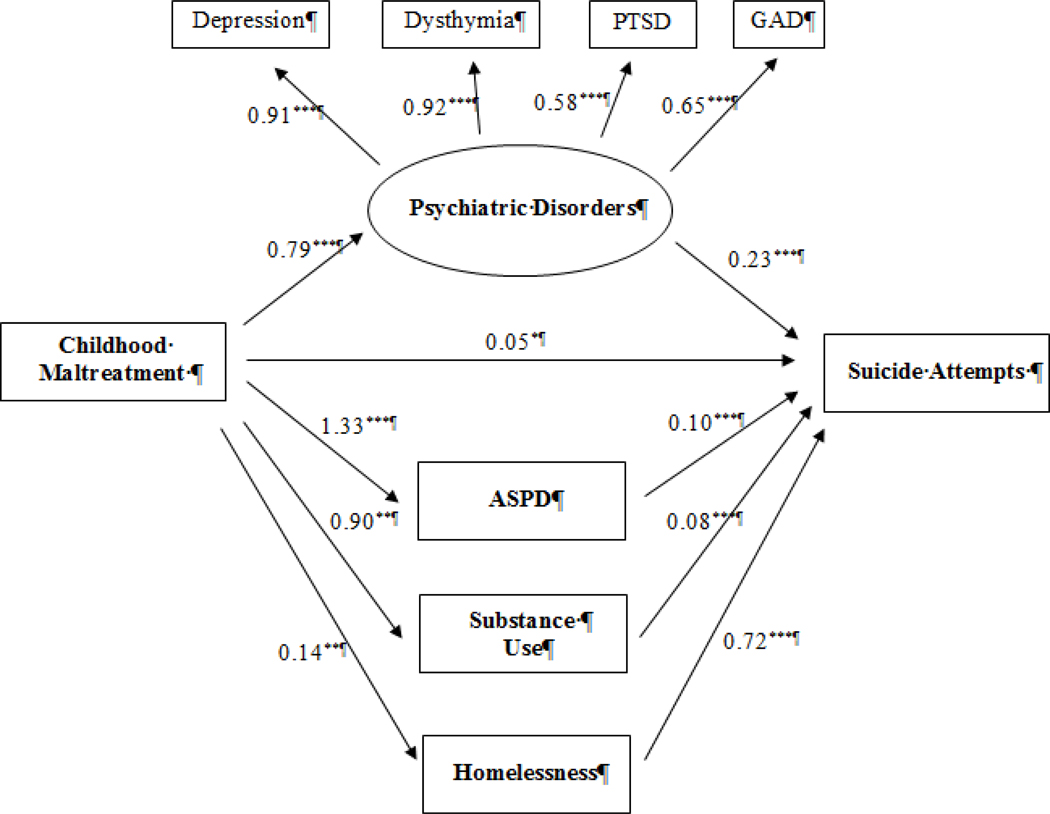

The next step involved a series of structural equation models (SEM) to test for mediation. We first tested individual models for each potential mediator, where childhood maltreatment was the independent variable and suicidal thoughts and attempts were the dependent variables in separate models. One psychiatric disorder or environmental vulnerability factor was included as a mediator in each individual model. We also conducted an exploratory factor analysis and found that symptoms of the four psychiatric disorders (depression, dysthymia, PTSD, and GAD) were highly correlated with one another and loaded on one factor. Factor loadings were 0.92 for depression, 0.92 for dysthymia, 0.65 for GAD and 0.59 for PTSD. However, ASPD and substance use symptoms did not correlate with the other four and were considered separate factors. In order to test whether a model that combined psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors had more predictive power than the individual models, a final full SEM model included the latent variable (depression, dysthymia, GAD, and PTSD), ASPD and substance use symptoms as unique variables, and homelessness (the only significant environmental vulnerability factor mediator) as predictors of suicide attempts.

Since suicidal thoughts and attempts were defined as dichotomous variables, standardized probit regression coefficients were reported. Probit regression is used to deal with binary and categorical outcomes. It uses an inverse normal link function and coefficients can be interpreted as the difference in z-score associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable. A confidence interval not overlapping zero is considered a significant difference. The probit regression yields the same results as a logistic regression in terms of detecting significance.

SEM models were run multiple times using Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimation method for each imputed dataset and then pooled. The magnitude of mediation effects was determined by the scale of indirect effects of childhood maltreatment to suicidal thoughts or attempts via each potential mediator. Overall fit indices [critical ratio [χ2], comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)] were reported to show model fit. All analyses were run in R [version 3.5.2, R-package MICE, R-package lavaan (version 0.6–3)].

3. Results

3.1. Childhood maltreatment and suicidality: Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents basic descriptive statistics for the maltreated children and matched controls at interviews 1 and 2. There were no differences between the maltreated and control groups in age at interview 1 or 2, sex, and race. However, individuals with histories of childhood maltreatment had significantly lower IQ scores than controls. Adults with histories of childhood maltreatment also had more symptoms of depression, dysthymia, PTSD, GAD, ASPD, and substance use and higher levels of environmental vulnerability factors (social isolation, physical illness or disabilities, and homelessness) than the control group in young adulthood. Individuals with documented histories of childhood maltreatment were also significantly more likely to report having made a suicide attempt (22.8%) compared to the control group (8.6%), whereas maltreated children were not more likely to report suicidal ideation (19.8% vs. 22.3%) than controls.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of individuals with documented histories of childhood maltreatment and matched controls

| Variable | Maltreated N = 495 | Control N =395 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | Chi square (df = 1) | p | |

| Female | 262 | 52.9 | 193 | 48.9 | 1.30 | 0.255 |

| White | 300 | 60.6 | 241 | 61.0 | 0.00 | 0.957 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T score | p | |

| Age at interview 1 | 29.14 | 3.73 | 29.45 | 3.85 | 1.23 | 0.218 |

| Age at interview 2 | 38.99 | 3.51 | 39.09 | 3.46 | 0.39 | 0.696 |

| IQ score (standardized) | 87.00 | 12.48 | 94.06 | 12.69 | 8.30 | <0.001 |

| Interview 1 (Mean age = 29.3) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T score | p |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | ||||||

| Depression | 3.86 | 2.79 | 3.07 | 2.67 | 4.29 | <0.001 |

| Dysthymia | 2.82 | 2.20 | 2.11 | 1.98 | 5.05 | <0.001 |

| PTSD | 6.30 | 6.13 | 4.10 | 5.13 | 5.82 | <0.001 |

| GAD | 4.79 | 5.45 | 3.74 | 4.64 | 3.11 | 0.002 |

| ASPD | 4.47 | 4.06 | 3.19 | 3.23 | 5.24 | <0.001 |

| Substance use | 4.61 | 4.71 | 3.71 | 4.12 | 3.05 | 0.002 |

| Environmental Vulnerability | ||||||

| Social isolation | 2.53 | 1.12 | 2.31 | 1.01 | 2.95 | 0.003 |

| Physical illness/disabilities | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 3.84 | <0.001 |

| Homelessness (N, %) | 132 | 26.7 | 50 | 12.7 | 25.65 | <0.001 |

| Interview 2 (Mean age = 39.0) | N | % | N | % | Chi square (df=1) | p |

| Suicidality Status (Interview 2) | ||||||

| No thoughts, no attempt | 284 | 57.4 | 273 | 69.1 | 12.83 | <0.001 |

| Thoughts only | 98 | 19.8 | 88 | 22.3 | 0.829 | 0.363 |

| Attempts (including thoughts) | 113 | 22.8 | 34 | 8.6 | 32.12 | <0.001 |

Notes: SD = standard deviation; Depression = major depressive disorder; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder. Psychiatric symptoms represent the number of lifetime symptoms. Substance use symptoms refer to the sum of the number of lifetime alcohol and drug symptoms from the DIS-III-R.

3.2. Characteristics of individuals with suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the three groups of individuals who differed in suicidality status at interview 2 (those who reported no suicidal thoughts or attempt, suicidal thoughts only, or having made a suicide attempt). There were no differences in ages across the three groups. More maltreated individuals (76.9%) and females (61.9%) reported having made a suicide attempt compared to those who reported thoughts only and no thoughts or attempt, whereas significantly more of those who identified as White, non-Hispanic (64.6%) reported having suicidal thoughts only, compared to those who reported an attempt or no thoughts or attempts. Individuals who reported having no suicidal thoughts or attempts and having made a suicide attempt had lower IQ scores than those who reported having suicidal thoughts only.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of three suicidality groups: no suicide thoughts or attempt, suicide thoughts only, and suicide attempt

| Variable | No suicide thoughts/no suicide attempt N = 557 | Suicide Thoughts Only N =186 | Suicide Attempt N =147 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Chi square (df=2) | p | |

| Abuse/neglect | 284 | 51.0 a | 98 | 52.7 a | 113 | 76.9 b | 32.38 | <0.01 |

| Female | 275 | 49.4 a | 89 | 47.8 a | 91 | 61.9 b | 8.32 | 0.016 |

| White | 316 | 57.1 a | 128 | 68.8 b | 95 | 64.6a,b | 9.13 | 0.008 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F value | p | |

| Age at interview 1 | 29.36 | 3.81 | 29.44 | 3.74 | 28.76 | 3.71 | 1.64 | 0.194 |

| Age at interview 2 | 39.15 | 3.53 | 39.03 | 3.44 | 38.62 | 3.35 | 1.34 | 0.263 |

| IQ score (standardized) | 89.47 a | 13.24 | 93.13 b | 13.06 | 88.79 a | 11.71 | 6.46 | 0.002 |

| Interview 1 | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F value | p |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | ||||||||

| Depression | 2.72 a | 2.45 | 4.48 b | 2.73 | 5.33 c | 2.67 | 72.27 | <0.001 |

| Dysthymia | 1.89 a | 1.80 | 3.21 b | 2.16 | 3.99 c | 2.23 | 72.48 | <0.001 |

| PTSD | 4.27 a | 5.24 | 5.75 b | 5.68 | 8.84 c | 6.60 | 31.58 | <0.001 |

| GAD | 3.27 a | 4.51 | 5.39 b | 5.37 | 6.84 c | 5.76 | 31.78 | <0.001 |

| ASPD | 3.30 a | 3.40 | 4.31 b | 3.78 | 5.68 c | 4.43 | 20.72 | <0.001 |

| Substance use | 3.29 a | 3.92 | 5.56 b | 4.67 | 6.01 b | 5.23 | 30.04 | <0.001 |

| Environmental Vulnerability | ||||||||

| Social isolation | 2.28 | 1.01 | 2.23 | 1.05 | 2.45 | 1.19 | 1.8 | 0.141 |

| Physical illness/disabilities | 0.20 a | 0.48 | 0.24a,b | 0.48 | 0.36 b | 0.60 | 6.7 | 0.003 |

| Homelessness (N, %) | 83 | 14.9 a | 42 | 22.6 a | 57 | 38.8 b | 41.41 | <0.001 |

Notes: Pairwise comparisons are indicated with superscript letters. Significance level is determined by adjusted p values from Bonferroni correction or Tukey’s method. Groups that differ significantly from one another have different superscript letters. SD = standard deviation; Depression = major depressive disorder; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder. Psychiatric symptoms represent the number of lifetime symptoms. Substance use symptoms refer to the sum of the number of lifetime alcohol and drug symptoms from the DIS-III-R.

Individuals who reported having made a suicide attempt had more psychiatric symptoms than individuals who reported suicidal thoughts only and both groups had more symptoms than those without any suicidal thoughts or attempts. Individuals who reported having made a suicide attempt also had more physical disabilities or illnesses and a higher rate of homelessness compared to those who had suicidal thoughts only and those with neither suicidal thoughts nor attempts. Social isolation was not associated with differences in the likelihood of reporting suicidal thoughts or attempts.

3.3. Childhood maltreatment, psychiatric disorders, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts

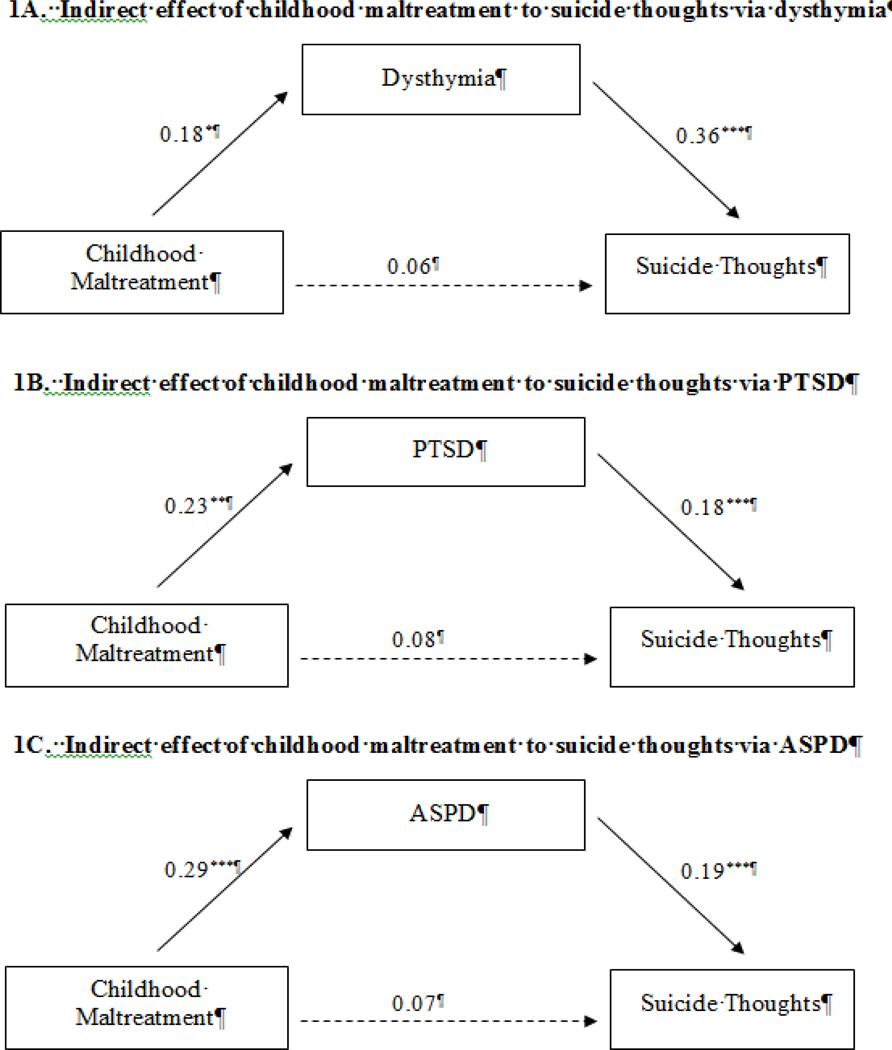

The results from the SEM models indicate that the total effect of childhood maltreatment on suicidal thoughts was not significant (total effect = 0.13, p = 0.235) and none of the models showed a significant direct path from childhood maltreatment to suicidal thoughts (see Table S1). However, there were significant indirect paths through dysthymia (indirect effect = 0.07, p = 0.022), PTSD (indirect effect = 0.04, p = 0.018), and ASPD (indirect effect = 0.06, p = 0.010) (see Figures 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Results of individual structural equation models showing the indirect effect of childhood maltreatment to suicide thoughts through dysthymia (1A) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1B) and anti-social personality disorder (ASPD) (1C). Solid lines are significant paths; dotted lines are not significant. Analyses control for age, sex, race and IQ score. Panel 1A: Total effect: 0.13; Total indirect effects = 0.07*, Model fit: χ2=18.867**, CFI = 0.797, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA =0.061. Panel 1B: Total effect: 0.13; Total indirect effects = 0.04*, Model fit: χ2=25.405***, CFI = 0.000, TLI = 0.679, RMSEA =0.073. Panel 1C: Total effect: 0.13; Total indirect effects = 0.06**, Model fit: χ2=107.568***, CFI = 0.000, TLI = 0.412, RMSEA =0.160. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001

In contrast to suicidal thoughts, the total effect of childhood maltreatment on suicide attempts was significant (total effect = 0.56, p <0.001) and all five separate models showed a direct path from child maltreatment to suicide attempts (see Table 3). There were significant indirect paths from child maltreatment to suicide attempts through depression (indirect effect = 0.11, p = 0.006), dysthymia (indirect effect = 0.14, p < 0.001), PTSD (indirect effect = 0.11, p < 0.001), GAD (indirect effect = 0.09, p = 0.005), ASPD (indirect effect = 0.12, p < 0.001) and substance use (indirect effect = 0.08, p = 0.004). In each of these separate models, the percent of the total effects explained for each mediator was: dysthymia (25.00%), ASPD (21.43%), depression (19.64%), PTSD (19.64%), and substance use (14.29%).

Table 3.

Structural equation models for childhood maltreatment predicting suicide attempts via psychiatric disorders

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | p | χ 2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.32, 0.80 | <0.001 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.44 | 0.11 | 0.22, 0.67 | <0.001 | 18.066** | 0.866 | 0.967 | 0.061 |

| CM -> Depression | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.08, 0.39 | 0.002 | ||||

| Depression -> Suicide Attempts | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.40, 0.56 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> Depression -> Suicide Attempts | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.19 | 0.006 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.19, 0.64 | 0.001 | 26.963*** | 0.812 | 0.953 | 0.078 |

| CM -> Dysthymia | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.13, 0.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| Dysthymia -> Suicide Attempts | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.42, 0.57 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> Dysthymia -> Suicide Attempts | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.06, 0.23 | 0.001 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.22, 0.69 | <0.001 | 33.398*** | 0.427 | 0.857 | 0.088 |

| CM -> PTSD | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.14, 0.45 | <0.001 | ||||

| PTSD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.27, 0.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> PTSD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.04, 0.17 | 0.001 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.24, 0.70 | <0.001 | 13.644* | 0.838 | 0.96 | 0.050 |

| CM -> GAD | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.10, 0.41 | 0.001 | ||||

| GAD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.26, 0.43 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> GAD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03, 0.15 | 0.005 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.21, 0.66 | <0.001 | 79.637*** | 0.046 | 0.731 | 0.142 |

| CM -> ASPD | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.19, 0.49 | <0.001 | ||||

| ASPD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.28, 0.46 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> ASPD -> Suicide Attempts | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06, 0.19 | <0.001 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempts | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.26, 0.70 | <0.001 | 70.431*** | 0.016 | 0.746 | 0.133 |

| CM -> Substance use | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.08, 0.37 | 0.003 | ||||

| Substance use -> Suicide Attempts | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.27, 0.43 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> Substance use -> Suicide Attempts | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.13 | 0.004 |

Notes: Beta = change in z score per unit change in independent variables; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; χ 2 = critical ratio chi square; degrees of freedom for chi-square test = 3; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI =Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CM = childhood maltreatment; Depression = major depressive disorder; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; ASPD = antisocial personal disorder. All psychiatric symptoms represent the number of lifetime symptoms. Substance use symptoms refer to the sum of the number of lifetime alcohol and drug symptoms from the DIS-III-R. All analyses controlled for age, sex, race and IQ score.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p<0.001

3.4. Childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and attempts through environmental vulnerability factors

Table 4 shows the detailed results of SEM models with the environmental vulnerability factors. Homelessness was the only environmental vulnerability factor that showed a significant indirect path to suicide attempts (indirect effect = 0.10, p = 0.003). There was also a non-significant trend for homelessness to predict suicidal thoughts (indirect effect = 0.03, p = 0.07).

Table 4.

Structural equation models for childhood maltreatment predicting suicide thoughts and suicide attempts via environmental vulnerability factors

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | p | χ 2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects: CM -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.08, 0.33 | 0.230 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.08, 0.34 | 0.220 | 51.893*** | <0.001 | 19.606 | 0.109 |

| CM -> Social Isolation | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.00, 0.28 | 0.056 | ||||

| Social Isolation-> Suicide Thoughts | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.12, 0.07 | 0.645 | ||||

| CM -> Social Isolation -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.661 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.10, 0.33 | 0.275 | 22.606** | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.067 |

| CM -> Physical Illness | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.05, 0.26 | 0.187 | ||||

| Physical Illness -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.01, 0.18 | 0.083 | ||||

| CM -> Physical Illness -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.441 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.12, 0.31 | 0.383 | 9.133 | 0.225 | 0.694 | 0.036 |

| CM -> Homelessness | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.07, 0.44 | 0.008 | ||||

| Homelessness -> Suicide Thoughts | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.03, 0.23 | 0.013 | ||||

| CM -> Homelessness> Suicide Thoughts | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00, 0.07 | 0.070 | ||||

| Total Effects: CM -> Suicide attempt | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.32, 0.79 | <0.001 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempt | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.31, 0.78 | <0.001 | 41.97*** | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.100 |

| CM -> Social Isolation | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.06, 0.36 | 0.006 | ||||

| Social Isolation-> Suicide Attempt | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05, 0.16 | 0.316 | ||||

| CM -> Social Isolation -> Suicide Attempt | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.04 | 0.364 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempt | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.31, 0.77 | <0.001 | 26.946*** | <0.001 | 0.618 | 0.078 |

| CM -> Physical Illness | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.03, 0.29 | 0.121 | ||||

| Physical Illness -> Suicide Attempt | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.08, 0.26 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> Physical Illness -> Suicide Attempt | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01, 0.05 | 0.155 | ||||

| Direct: CM -> Suicide Attempt | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.23, 0.69 | <0.001 | 10.692* | 0.608 | 0.902 | 0.042 |

| CM -> Homelessness | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.14, 0.54 | 0.001 | ||||

| Homelessness -> Suicide Attempt | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.20, 0.37 | <0.001 | ||||

| CM -> Homelessness -> Suicide Attempt | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.03, 0.16 | 0.003 |

Notes: Beta = change in z score per unit change in independent variables; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; χ 2 = critical ratio chi square; degrees of freedom for chi-square test = 3; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI =Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CM = childhood maltreatment. Physical illness includes physical illness and disabilities. All analyses controlled for age, sex, race and IQ.

3.5. Full path model with psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors as mediators between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts

The final analysis examined whether a model including both psychiatric symptoms and homelessness would produce a better model fit and the results indicated that the full path model with psychiatric symptoms and homelessness converged. Figure 2 presents the results of the combined model with pathways from childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts through psychiatric disorders as a latent construct, and ASPD, substance use, and homelessness as separate factors. The total effect of childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts (total effect = 0.53, p < 0.001) in the individual models became non-significant in the full SEM model (direct effect = 0.05, p = 0.652), indicating mediation. The four indirect paths from childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts through the latent construct of psychiatric disorders (indirect effect = 0.18, p < 0.001), ASPD (indirect = 0.13, p < 0.001), substance use (indirect effect = 0.007, p = 0.005), and homelessness (indirect effect = 0.10, p = 0.002) were all significant. Psychiatric symptoms explained more than a third of the total effects (33.96%), followed by ASPD (24.53%), homelessness (18.87%), substance use (13.21%), and childhood maltreatment (9.43%).

Figure 2.

Results of full structural equation model with significant paths from childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts through a latent construct composed of symptoms of four psychiatric disorders (depression, dysthymia, PTSD, and GAD) and three separate paths representing symptoms of antisocial personality disorder and substance use, and homelessness. Analyses control for age, sex, race and IQ score. Total effect = 0.53***; indirect effects through psychiatric disorders = 0.18***, ASPD = 0.13***, substance use = 0.07**, and homelessness = 0.10**; total indirect effects = 0.48***. Model fit indices: χ 2(df = 44) = 1367.301***, CFI = 0.434, TLI = 0.640, RMSEA = 0.100***. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001

4. Discussion

The first question we asked was whether individuals with documented histories of childhood maltreatment were more likely to report suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, compared to matched control children, when both groups were followed up prospectively into later life. Our findings indicated that childhood maltreatment predicted suicide attempts in middle adulthood, whereas childhood maltreatment did not predict suicidal thoughts only. Because these results only partially supported our hypotheses, a possible explanation seems warranted. Many of the prior studies that have reported an association between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation have focused on adolescents (e.g., Brezo et al., 2008; Brown et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2012) or even younger children (Thompson et al., 2005). Reports of suicidal thoughts or ideation during adolescence are a fairly common phenomenon (D. K. Eaton et al., 2012) and studies of adolescents reflect a snapshot of this stage of life. It may be that this snapshot differs from the perspective of an adult, where suicide attempts are salient events accompanied by pain and suffering, compared to more common suicidal thoughts that may be less clearly remembered. There is some evidence to support this possibility. In one study of adults, Bahk et al. (2017) did not find an association between suicidal ideation and physical or emotional abuse. Arata et al. (2007) also did not find an association between childhood sexual abuse and suicidality, although their measure was a composite that included a number of phenomena, not directly linked to suicide. A longitudinal study with youth (some of whom had substantiated cases of childhood neglect) found that childhood neglect did not independently predict future suicide attempts (Brown et al., 1999). In addition, although some studies included both suicidal ideation and attempts, many did not make direct comparisons (e.g., Harford et al., 2014).

As expected, individuals with documented histories of childhood maltreatment had more symptoms of depression, anxiety, dysthymia, PTSD, ASPD, and substance use than controls (Afifi et al., 2008; Gilbert et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 1999; Lindert et al., 2014; Sugaya et al., 2012; Widom, 1999; Widom et al., 2007). Also, consistent with the existing literature (Algood et al., 2011; Coohey, 1996; Danese et al., 2009; Kendall-Tackett, 2002; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2017; Sullivan and Knutson, 2000; Sundin and Baguley, 2015), we also found that previously maltreated children had higher levels of environmental vulnerability (social isolation, physical disability and illness, and homelessness) in young adulthood.

The second question was whether the two suicidality groups -- those with thoughts only and those with suicide attempts -- would differ in term of psychiatric symptoms and environmental risk factors. The findings were striking and showed differences among the three groups that reflected a clear progression from those with no suicidal thoughts or attempts to those with suicidal thoughts only to those who reported suicide attempts having the most psychiatric symptoms and environmental risk factors. Although some researchers have collapsed different forms of suicidal behavior and associated risk factors into one variable (e.g., Arata et al., 2007; Brent et al., 1993; Fortune et al., 2005; Grilo et al., 1999; Kaplan et al., 1999; Kisiel and Lyons, 2001), these new results add to a growing body of research suggesting that suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts are distinct phenomena (Albanese et al., 2019; Klonsky and May, 2015; van Orden et al., 2010; Wetherall et al., 2018). Collapsing suicidal ideation and suicide attempts into one measure may mask significant differences in these relationships.

Only a small subset of those who think about suicide will make an attempt, and even fewer will die by suicide (van Orden et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2018). Estimates from nationally representative studies indicate that each year, 3.3 percent of Americans report active suicidal ideation), 1.0 percent develop a plan for suicide, and 0.6 percent attempt suicide (Kessler, Berglund, Borges, et al., 2005). Consistent with the results of community surveys indicating that suicidal thoughts are more common than attempts (Nock et al., 2013), in our sample, 16.5% reported attempts and 31.3% reported suicidal thoughts (this figure includes 90% of those who made attempts). Many people have suicidal thoughts at some point in their lives, but our findings show that adults with a history of childhood maltreatment have more psychiatric symptoms (depression, dysthymia, anxiety, PTSD, ASPD, and substance use) and higher rates of homelessness that may lead them on a trajectory of higher risk for suicide attempts. These results provide some support for the model of suicidal behavior proposed by Maris (1991, 2002) that emphasizes the interaction of multiple factors across several domains of risk, on the assumption that those with suicidal ideation only have fewer risk factors, those who make suicide attempts have more risk factors, and those who commit suicide would manifest the most interacting risk factors. Earlier research has shown the importance of interactions in the prediction of suicidal behavior (e.g., O’Connor et al., 2010).

Interestingly, the one characteristic not consistent with this pattern of a progression from lower to higher levels of suicide risk was IQ. IQ was controlled because of its significance as an outcome for maltreated children (Perez and Widom, 1994) and because it is related to other factors (e.g., impulse control, problem solving ability, stress management) (Cloitre et al., 2010; Perroud et al., 2010; Springer et al., 2007; van Harmelen et al., 2013), which have been related to suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Bender et al., 2011; Braquehais et al., 2010; Dour et al., 2011; Gvion and Apter, 2011; Quiñones et al., 2015). Our new results indicated that those with suicidal thoughts only had significantly higher IQ than the other two groups. In other research, higher IQ has been shown to be a protective factor for maltreated children. In the current study, it may be that the higher IQ exerted a protective influence on these individuals, leading to thoughts but not to suicide attempts.

The third question was whether psychiatric disorders or environmental vulnerability factors explained the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal thoughts and attempts. These results showed that the psychiatric disorders mediated the path from maltreatment to suicide attempts, with the most variance explained by dysthymia, followed by antisocial personality disorder. Some studies have examined potential psychiatric symptoms as mediators. Miller et al. (2014) found that depression mediated the relationship between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation. Bahk et al. (2017) found that physical abuse and emotional abuse indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through anxiety. In a nationally representative survey of adults in Korea, Lee (2015) found that depressive symptoms mediated the association between emotional abuse and suicidality. Thompson et al. (2005) reported that anxiety and depression mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidality among 8 year olds. Brezo et al. (2008) found that aggression at age 6 years was most relevant, among those who had attempted suicide, in participants who reported the most severe childhood abuse type (both physical and sexual). Felzen (2002) found that interpersonal problems mediated the relationship between maltreatment and social behavior. To our knowledge, previous research has not systematically examined and compared the explanatory power of these internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

We also examined social and environmental risk factors, as suggested in an editorial in a special issue on suicide-related research (van Harmelen et al., 2019) that called attention to increasing interest in social and environmental factors that may be intervention targets and modifiers of treatment effects. While our findings showed that maltreated children had higher levels of environmental vulnerability factors, only homelessness represented a significant path from childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts. The current findings confirm previous research that has reported a link between homelessness and suicidal thoughts and attempts (Ayano et al., 2019; Desai et al., 2003; Eynan et al., 2002; Lee, 2015; Schinka et al., 2012; van Orden et al., 2010), but extends that literature with evidence from a non-clinical sample of maltreated children with documented histories followed prospectively into adulthood.

Surprisingly, we did not find a path from physical disability and illness to suicide attempts, despite the fact that maltreated children had higher rates. It may be that the participants in this study did not have as severe illnesses and physical disabilities as reported in previous papers (Choi et al., 2019; Conwell et al., 2009; Waern et al., 2002). Given that previous studies have focused on the relationship between physical illness and disabilities in elderly populations, it is possible that these findings might change with advancing age of the participants and may reveal a relationship in the future. Also, in contrast to the existing literature, although more individuals with histories of childhood maltreatment reported being socially isolated compared to the controls, social isolation did not play a significant role in predicting suicide thoughts or attempts. According to de Catanzaro (1995), people are more prone to suicide the less attached they feel to a social group and the weaker they feel about their chances of becoming part of a social community. High levels of connectedness and social supports have been found to be protective against suicidal outcomes (Calati et al., 2019; Hall-Lande et al., 2007). Calati et al. (2019) also pointed out that there are two components of social isolation – an objective social isolation (e.g., living alone) and subjective feelings of being alone – that are incorporated in risk assessments of suicide. The measure used here was based on answers to questions about how often participants got together with family members, other people for a hobby or leisure activities, close friends, or neighbors, or to attend a church, synagogue, or prayer group. This measure did not include a subjective measure of being alone, but rather was defined as never interacting with family or friends and not being married. It is possible that a different measure of social isolation or a measure of social support might have revealed a stronger role in predicting suicide thoughts and attempts and should be examined in future research.

The last question was whether the combination of psychiatric symptoms and environmental vulnerability factors would better explain the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts compared to a model with only psychiatric symptoms or environmental factors. Looking only at model fit, none of the models showed a perfect fit. However, the final model indicated that when both sets of factors were included, the path from childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts became non-significant. Psychiatric symptoms explained more than a third of the total effects, followed by antisocial personality disorder, homelessness, substance use, and the smallest percent by childhood maltreatment. Thus, in addition to reinforcing the important role of internalizing symptoms (anxiety, depression, dysthymia, and PTSD) (Bahk et al., 2017; Brezo et al., 2008; Brown et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2002; Lee, 2015; Lopez-Castroman et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2014; Sachs-Ericsson, 2017; Sareen et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2012), these new findings demonstrate an externalizing path through antisocial personality disorder and substance use symptoms to suicide attempts. A number of previous studies have documented associations between antisocial personality disorder (Apter et al., 1995; Apter et al., 1991; Brezo et al., 2006; Hills et al., 2009; Jokinen et al., 2010; Links et al., 2003; Maddocks, 1970; Verona et al., 2004) and conduct disorder (Apter et al., 1995; Brent et al., 1993). However, this path warrants further research and clinical attention.

4.1. Limitations

Despite the many strengths of this study, including the use of a unique data set on the long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment; a prospective longitudinal design that spans over 30 years from childhood to young adulthood to middle adulthood; a clear operationalization of childhood maltreatment; a matched control group of children also followed up; correct temporal sequence of key variables; and interviews with high-risk individuals in households without telephones or in prison, a number of limitations should be noted. Because these cases were identified through the courts, these findings are not generalizable to unreported or unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment. Because this sample is predominantly from the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, these findings cannot be generalized to cases of abuse and neglect that might occur in middle or upper class families. This study represents the experiences of children growing up in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the Midwest part of the United States and may raise concerns about applying these findings to the present society. However, the maltreatment cases studied here are quite similar to current cases being processed by the child protection system and the courts. One difference is that these children were not provided with extensive services or treatment options as are available today and, thus, the results of this study represent the natural history of the development of maltreated children whose cases have come to the attention of the courts. Because suicidality was measured about 10 years after the assessment of the psychiatric disorders, it is possible that some of the participants who did not have symptoms at the first interview might have developed symptoms during the following years. Although determining the age of onset of psychiatric disorders is acknowledged as methodologically challenging, there is consensus that most adult mental health disorders have their onset by adolescence (Jones, 2013; Kessler et al., 2007; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, et al., 2005). We did not have information about emotional maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, or family history of suicide, and are not able to reliably examine whether characteristics of the abuse (type, age of onset, or intensity) have different relationships to suicide thoughts and attempts. Finally, the fit for the path models was not high, even for the more full model, suggesting that there are likely to be other factors and causal mechanisms at work. Future research should examine the role of other factors such as social support, impulsivity, aggression, emotion regulation, genetic factors, and biomarkers that may explain the path from childhood maltreatment to suicidality. As the participants in this study age, it will be important to continue this examination of suicidality and additional factors that may contribute to their risk.

4.2. Conclusions

These results add to a growing body of research suggesting that suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts are distinct phenomena. Adults with a history of childhood maltreatment overall have more psychiatric internalizing and externalizing symptoms (depression, dysthymia, anxiety, PTSD, ASPD, and substance use) and higher rates of homelessness that place them on a trajectory of higher risk for suicide attempts. While the psychiatric risk factors for suicide are well recognized, these new results provide strong evidence that at least one environmental vulnerability factor, i.e., homelessness, is associated with increased risk for suicide attempts and warrants heightened attention from clinicians and others working with at-risk populations. Better understanding of the mechanisms linking childhood maltreatment to suicide attempts will contribute to effective interventions to reduce risk.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Childhood maltreatment predicts suicide attempts, not suicidal thoughts only.

Adults with suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts differ in the extent of their psychiatric symptoms, physical illnesses and disabilities, and experience of homelessness.

Environmental vulnerability factors increase risk for suicide attempts.

Psychiatric and substance use symptoms and homelessness are pathways linking child maltreatment to suicide attempts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 2011-WG-BX-0013), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), NIA (AG058683), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of Justice. We express appreciation for helpful suggestions by Peggilee Wupperman and reviewers of a previous draft of this manuscript.

AUTHOR STATEMENT

This work was supported in part by grants from NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 2011-WG-BX-0013), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), NIA (AG058683), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of Justice. We express appreciation for helpful suggestions by Peggilee Wupperman and reviewers of a previous draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG, Stein MB, & Sareen J, 2008. Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. American journal of public health 98, 946–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese BJ, Macatee RJ, Stanley IH, Bauer BW, Capron DW, Bernat E, . . . Schmidt NB, 2019. Differentiating suicide attempts and suicidal ideation using neural markers of emotion regulation. J Affect Disorders 257, 536–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algood CL, Hong JS, Gourdine RM, & Williams AB, 2011. Maltreatment of children with developmental disabilities: An ecological systems analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev 33, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ammons RB, & Ammons CH, 1962. The Quick Test (QT): Provisional Manual. Psychological Reports 11, 111–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Wright AG, Markowitz JC, Sanislow CA, Hopwood CJ, Zanarini MC, . . . Grilo CM, 2015. Personality disorder risk factors for suicide attempts over 10 years of follow-up. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 6, 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apter A, Gothelf D, Orbach I, Weizman R, Ratzoni G, Har-Even D, & Tyano S, 1995. Correlation of suicidal and violent behavior in different diagnostic categories in hospitalized adolescent pateints. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 34, 912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apter A, Kotler M, Sevy S, Plutchik R, Brown SL, Foster H, . . . van Praag HM, 1991. Correlates of risk of suicide in violent and nonviolent psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 148, 883–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, & O’Brien N, 2007. Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse Neglect 31, 393–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artenie AA, Bruneau J, Zang G, Lesperance F, Renaud J, Tremblay J, & Jutras-Aswad D, 2015. Associations of substance use patterns with attempted suicide among persons who inject drugs: Can distinct use patterns play a role? Drug Alcohol Depen 147, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafioun L, Bishop TM, Conner KR, & Pigeon WR, 2017. Frequency of prescription opioid misuse and suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts. Journal of Psychiatric Research 92, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayano G, Tsegay L, Abraha M, & Yohannes K, 2019. Suicidal ideation and attempt among homeless people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiat Quart 90, 829–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk YC, Jang SK, Choi KH, & Lee SH, 2017. The relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation: Role of maltreatment and potential mediators. Psychiat Invest 14, 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, & Joiner TE, 2011. Impulsivity and suicidality: The mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. J Affect Disorders 129, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, 2015. The natural history of antisocial personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 60, 309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boenisch S, Bramesfeld A, Mergl R, Havers I, Althaus D, Lehfeld H, . . . Hegerl U, 2010. The role of alcohol use disorder and alcohol consumption in suicide attempts--a secondary analysis of 1921 suicide attempts. Eur Psychiat 25, 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, & Robinson J, 2010. Population-attributable fractions of Axis I and Axis II mental disorders for suicide attempts: Findings from a representative sample of the adult, noninstitutionalized US population. American Journal of Public Health 100, 2473–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Corwyn RF, 2002. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual review of psychology 53, 371–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braquehais MD, Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, & Sher L, 2010. Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Comprehensive Psychiatry 51, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, . . . Baugher M, 1993. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: A case-control study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 32, 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezo J, Paris J, & Turecki G, 2006. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113, 180–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezo J, Paris J, Vitaro F, Hebert M, Tremblay RE, & Turecki G, 2008. Predicting suicide attempts in young adults with histories of childhood abuse. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science 193, 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, & Smailes EM, 1999. Childhood abuse and neglect: Specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38, 1490–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, Oasi O, Olie E, Carvalho AF, & Courtet P, 2019. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. J Affect Disorders 245, 653–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Web-Based Injury Statisics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS): Leading Causes of Death Reports. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Chabrol H, Rodgers R, & Rousseau A, 2007. Relations between suicidal ideation and dimensions of depressive symptoms in high-school students. J Adolescence 30, 587–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HB, Munroe S, Gray K, Porta G, Douaihy A, Marsland A, . . . Melhem NM, 2019. The role of substance use, smoking, and inflammation in risk for suicidal behavior. J Affect Disorders 243, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, & Conwell Y, 2019. Physical health problems as a late-life suicide precipitant: Examination of coroner/medical examiner and law enforcement reports. The Gerontologist 59, 356–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Nooner K, Zorbas P, Cherry S, Jackson CL, . . . Petkova E, 2010. Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 167, 915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Bridge JA, Davidson DJ, Pilcher C, & Brent DA, 2019. Meta-analysis of mood and substance use disorders in proximal risk for suicide deaths. Suicide & life-threatening behavior 49, 278–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy K, Sandel M, & Zuckerman B, 2010. Poverty grown up: How childhood socioeconomic status impacts adult health. J Dev Behav Pediatr 31, 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Hirsch JK, Conner KR, Eberly S, & Caine ED, 2009. Health status and suicide in the second half of life. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 25, 371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coohey C, 1996. Child maltreatment: Testing the social isolation hypothesis. Child Abuse and Neglect 20, 241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, & Widom CS, 2010. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment 15, 111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, . . . Caspi A, 2009. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 163, 1135–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishi N, Farhadi M, Haghtalab T, & Poorolajal J, 2015. Alcohol-related risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide: A meta-analysis. PloS One 10, e0126870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Catanzaro D, 1995. Reproductive status, family interactions, and suicidal ideation: Surveys of the general public and high-risk groups. Ethnology and Sociobiology 16, 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Liu-Mares W, Dausey DJ, & Rosenheck RA, 2003. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a sample of homeless people with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191, 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizzone MF, & Davis WE, 1973. Relationship between Quick Test and WAIS IQs for brain-injured and schizophrenic subjects. Psychological Reports 32, 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dour HJ, Cha CB, & Nock MK, 2011. Evidence for an emotion–cognition interaction in the statistical prediction of suicide attempts. Behaviour Research and Therapy 49, 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, . . . Prevention. 2012. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 61, 1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Regier DA, Locke BZ, & Taube CA, 1981. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. Public health reports 96, 319–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, & Spirito A, 2009. Risk factors for suicidality among a nationally representative sample of high school students. Journal of Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 39, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eynan R, Langley J, Tolomiczenko G, Rhodes AE, Links P, Wasylenki D, & Goering P, 2002. The association between homelessness and suicidal ideation and behaviors: Results of a cross-sectional survey. Suicide & life-threatening behavior 32, 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassberg MM, van Orden KA, Duberstein P, Erlangsen A, Lapierre S, Bodner E, . . . Waern M, 2012. A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9, 722–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, & Gibbons R, 1990. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 147, 1189–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felzen JC, 2002. Child maltreatment 2002: Recognition, reporting and risk. Pediatrics International 44, 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flensborg-Madsen T, Knop J, Mortensen EL, Becker U, Sher L, & Gronbaek M, 2009. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk of completed suicide - irrespective of other psychiatric disorders. A longitudinal cohort study. Psychiatry Research 167, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune S, Seymour F, & Lambie I, 2005. Suicide behaviour in a clinical sample of children and adolescents in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 34, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Friestad C, Ase-Bente R, & Kjelsberg E, 2014. Adverse childhood experiences among women prisoners: Relationships to suicide attempts and drug abuse. Int J Soc Psychiatr 60, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, & Janson S, 2009. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373, 68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi G, Atkin T, Zytynski T, Wang S, Askari S, Boruff J, . . . Mayo N, 2019. Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, & Hamilton SP, 2003. Lifetime comorbidity of antisocial personality disorder and anxiety disorders among adults in the community. Psychiatry Research 117, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Fehon DC, Martino S, & McGlashan TH, 1999. Psychological and behavioral func- tioning in adolescent psychiatric inpatients who report histories of childhood abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry 156, 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gvion Y, & Apter A, 2011. Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: A review of the literature. Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research 15, 93–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, & Neumark-Sztainer D, 2007. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence 42, 265–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Yi HY, & Grant BF, 2014. Associations between childhood abuse and interpersonal aggression and suicide attempt among U.S. adults in a national study. Child Abuse and Neglect 38, 1389–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy LT, Spitznagel EL, Stoltzman RK, Farmer A, & Brockington IF, 1985. A comparison of clinical and diagnostic interview schedule diagnoses: Physician reexamination of lay-interviewed cases in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 42, 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills AL, Afifi TO, Cox BJ, Bienvenu OJ, & Sareen J, 2009. Externalizing psychopathology and risk for suicide attempt: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 197, 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HJ, Roh MS, Kim KH, Lee JR, Lee D, Yoon SC, & Hahm BJ, 2009. Early trauma and lifetime suicidal behavior in a nationwide sample of Korean medical students. J Affect Disorders 119, 210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joesting J, & Joesting R, 1972. Quick Test validation: Scores of adults in a welfare setting. Psychological Reports 30, 537–538. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, & Bernstein DP, 1999. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry 56, 600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, & Brook JS, 2002. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry 59, 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen J, Ouda J, & Nordstrom P, 2010. Noradrenergic function and HPA axis dysregulation in suicidal behaviour. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]