Abstract

Background:

The 2018 physical activity guideline for Americans recommends a minimum of 150–300 minutes per week of moderate physical activity (MPA) or 75–150 minutes per week of vigorous physical activity (VPA) or an equivalent combination of both. However, it remains unclear whether higher levels of long-term VPA and MPA are, independently and jointly, associated with lower mortality.

Methods:

A total of 116,221 adults from 2 large prospective US cohorts (Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study, 1988–2018) were analyzed. Detailed self-reported leisure-time physical activity was assessed using a validated questionnaire, repeated up to 15 times. Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the association between long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Results:

During 30 years of follow-up, we identified 47,596 deaths. In analyses mutually adjusted for MPA and VPA, HRs (95% CIs) comparing individuals meeting the long-term leisure-time VPA guideline (75–149 min/week) vs. no VPA were 0.81 (0.76–0.87) for all-cause mortality, 0.69 (0.60–0.78) for CVD mortality and 0.85 (0.79–0.92) for non-CVD mortality. Meeting the long-term leisure-time MPA guideline (150–299 min/week) was similarly associated with lower mortality; 19–25% lower risk of all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality. Compared to those meeting the long-term leisure-time physical activity guideline, participants who reported 2 to 4 times above the recommended minimum of long-term leisure-time VPA (150–299 min/week) or MPA (300–599 min/week) showed 2–4% and 3–13% lower mortality, respectively. Higher levels of either long-term leisure-time VPA (≥300 min/week) or MPA (≥600 min/week) did not show clearly further lower all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality, nor harm. In joint analyses, for individuals who reported less than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA, additional leisure-time VPA was associated with lower mortality; however, among those who reported more than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA, additional leisure-time VPA did not appear to be associated with lower mortality beyond MPA.

Conclusion:

The nearly maximum association with lower mortality was achieved by performing approximately 150–300 min/week of long-term leisure-time VPA or 300–600 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA or an equivalent combination of both.

Keywords: Physical activity, vigorous activity, moderate activity, cardiovascular disease, mortality, guideline

Introduction

Regular physical activity has been consistently associated with reduced risk of major non-communicable diseases and premature death.1 The 2018 physical activity guidelines recommend adults to engage in at least 150–300 min per week of moderate physical activity (MPA) or 75–150 min per week of vigorous physical activity (VPA) or an equivalent combination of both intensities.2 In the physically active population, a growing number of people are performing higher levels of leisure-time physical activity to maintain health and improve fitness.3, 4 However, there are concerns regarding potential harmful effects on cardiovascular health of accumulating an excessive amount of VPA, such as exercise programs designed to run a marathon.5 It remains unclear whether engaging in high level of prolonged MPA or VPA over the recommended levels provides additional benefit or harmful effects on health.

Several studies have examined graded associations between total physical activity and mortality, showing no additional benefits after reaching a certain threshold of total physical activity,6, 7 while some studies showed a clear U-shaped association between physical activity and mortality.8 However, most studies had a single measure of self-reported or device-based physical activity at baseline with short follow-up, which is prone to reverse causation bias and cannot identify long-term adherents to high levels of physical activity. Our previous methodologic study showed that compared to single measure of physical activity, repeated measures of physical activity reduce these common biases observed in previous studies of physical activity and mortality.9 Additionally, application of a 2-year lag period between physical activity assessment and mortality substantially reduces the influence of reverse causation while longer lag periods (4–12 years) had minimal impact on the association beyond a 2-year lag. Despite the commonly recognized limitation of using single measures, previous studies generally did not employ the advanced methodologic approach of using repeated measures of physical activity.

Furthermore, previous studies have not examined the long-term association of VPA and MPA, separately and jointly, with explicit recognition that VPA and MPA may have different graded associations for different mortality outcomes. In addition to examining the independent association of physical activity intensity, it is also critical to investigate the joint association of VPA and MPA. For instance, studies have not isolated the added benefit of VPA in individuals with low levels of MPA in contrast to those with high levels of MPA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies suggested that for the same amount of total physical activity, a higher proportion of VPA to total physical activity was not associated with lower all-cause mortality.10 However, in a large prospective study, for the same amount of total physical activity, higher proportion of VPA was associated with a lower mortality risk.11 In contrast, some studies performed in middle-aged recreational runners have suggested that a high amount of VPA has deleterious effects on cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes.12–14 These findings suggest that the health benefits of physical activity may differ by dose (intensity and duration) as well as by the outcomes examined.

Therefore, the current study used two large prospective cohorts with up to 15 repeated measures of self-reported leisure-time physical activity over 30 years of follow-up to examine the graded association between long-term VPA and MPA and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Moreover, the joint association of different physical activity intensities with mortality was further examined.

Methods

Data sharing

The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be available to other researchers from the corresponding author on reasonable request for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) began in 1976 when 121,701 female nurses (age 30–55 years) were enrolled. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) began in 1986 when 51,529 male health professionals (age 40–76) were enrolled. At enrollment and every 2 years, participants were asked to complete questionnaires on demographic, lifestyle, and medical history information. The follow-up rate for both cohorts exceeded 90% for each questionnaire cycle. The present study included participants who had information on detailed leisure-time physical activity in 1986. To reduce the influence of reverse causation in the relationship between physical activity and mortality, the present study excluded participants diagnosed with CVD or cancer at baseline and applied a 2-year lag time between physical activity assessment and the time at risk of dying.9 Thus, our baseline was defined as 1988 for both NHS and HPFS. The final analysis included a total of 116,221 participants. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and those of participating registries as required.

Physical activity assessment

Detailed information on leisure-time physical activity was first assessed via self-reported questionnaire in 1986 and updated every 2 years. Up to 15 repeated measures of physical activity (median [10th-90th]: 11 [3–13]) were available and the same questionnaires were used over the follow-up, except that weight training information was added beginning from 1990 for HPFS and 2000 for NHS. The reproducibility and validity of physical activity questionnaire have been previously described.15–18 From the biennial questionnaires, participants were asked to report average hours they spent during the past year on various activities including walking, jogging, running, swimming, bicycling, calisthenics and other aerobic exercises, squash/racquetball, tennis, lower-intensity exercise, weightlifting, and outdoor work. To quantify the intensity of physical activity, we assigned a metabolic equivalent task (MET) which designate metabolic rates for a specific activity divided by metabolic rates at rest according to a compendium of physical activities.19 Moderate activity was defined as activities <6 MET including walking, lower-intensity exercise, weightlifting, and calisthenics. Vigorous activity was defined as activities ≥6 MET including jogging, running, swimming, bicycling, and other aerobic exercises, squash/racquetball, tennis, outdoor work, and stair climbing. Moderate and vigorous physical activities were calculated by summing the corresponding physical activities in MET-hours per week.

Covariate assessment

Information on age, race, height, weight, family history of disease, personal medical history, smoking, and sleep duration were assessed from the biennial questionnaires. Body mass index was calculated by weight in kilogram divided by height in meter squared. Dietary information was assessed using validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires every 4 years.20–22 The Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) was used to indicate overall diet quality (0–100).23

Outcomes ascertainment

Deaths were identified from the National Death Index, next of kin or postal system.24, 25 Through these methods, over 98% of deaths were ascertained for both cohorts. Information on the cause of death was collected by physician review of medical records. When medical records were not available, death certificates were obtained. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8 and 9) codes were used to classify deaths from cardiovascular disease (ICD code: 390–459 and 795) and non-CVD related causes. Moreover, CVD was defined as the composite of incident nonfatal myocardial infarction, fatal CHD, and fatal and nonfatal stroke. Nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke were confirmed by physicians according to the World Health Organization criteria26 and the National Survey of Stroke criteria,27 respectively.

Statistical analysis

Person-time was calculated from the baseline in 1988 until the time of death, or the end of the follow up period (January 2018 for HPFS and June 2018 for NHS), whichever occurred first. Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the association between long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity and deaths from all causes, CVD and non-CVD. Results from HPFS and NHS were pooled after testing for heterogeneity between cohorts (P>0.05). Cumulative average of repeated measures of physical activity was used to capture the long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity and to reduce within person measurement error. Based on the current physical activity guideline, MPA and VPA were finely categorized into 9 categories based on physical activity guideline (0, 1–74, 75–149, 150–224, 225–299, 300–374, 375–449, 450–599, ≥600 min/week).2 Because there was small number of participants who consistently reported no MPA over the entire follow-up, the reference group for MPA was broadened to 0–19 min/week (approximately 10% of the distribution). Multivariable-adjusted Cox regression model using age (month) as time scale with stratification by calendar time (year) and cohort, and additionally adjusted for race (white or non-white), family history of CVD (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), postmenopausal hormone use (women only) (premenopausal, postmenopausal current user, or postmenopausal never/past user), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–14.9, or 15.0+ g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), smoking status (never, past, or current: 1–14, 15–24, ≥25 cigs/day), sleep duration (≤6, 7–8, or >8), Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles), body mass index (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, 27–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2). To examine the independent association of long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity, VPA and MPA were mutually adjusted in all models.

In addition, restricted cubic spline models were used with 3 knots to flexibly model the shape of the association of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA with all-cause and cause-specific mortality.28 Given that VPA and MPA are correlated (r=0.2), joint analyses of MPA and VPA were conducted to examine how the combination of VPA and MPA was associated with mortality. Moreover, stratified analyses by potential effect modifiers such as age, sex, body mass index, smoking and alcohol were performed. Several sensitivity analyses were done by not adjusting for BMI/calorie intake (potential mediator), further adjusting for physical limitation or excluding those who did not engage in any physical activity (potential reverse causation). Additionally, different approaches of characterizing physical activity were compared (i.e., single measure at baseline, cumulative average of repeated measures for the first 10 years, 20 years and all follow-up years). As a secondary analysis, the long-term proportion of VPA to total physical activity (%VPA) instead of absolute level of MPA and VPA was used to examine the association between long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity and mortality. Lastly, the same analyses were repeated using incident CVD outcome, in addition to our primary mortality outcome, to examine the association between long-term leisure-time physical activity intensity and CVD risk.

All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants’ characteristics according to long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA are presented in Table 1. The mean age and BMI of participants over the follow-up was 66 years and 26 kg/m2. The majority of them were White and the percentage of female was 63%. Participants were also free of major chronic diseases (i.e., CVD and cancer) at baseline. Among participants with any physical activity, participants with higher long-term leisure-time VPA were younger while participants with higher long-term leisure-time MPA were older. Moreover, participants with higher long-term leisure-time VPA or MPA were leaner and had higher alcohol intake and diet quality score and lower prevalence of current smoking.

Table 1.

Age and sex standardized characteristics of person-years over the follow-up (N=116,221)a

| Vigorous Physical Activity (min/week) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| PA guideline | 0 Inactive | 1–74 Insufficient | 75–149 Sufficient | 150–224 ×2 | 225–299 ×3 | 300–374 ×4 | 375–449 ×5 | 450–599 ×6 | ≥600 ×8 or more |

| Person-years | 91573 | 1776378 | 539846 | 269767 | 122439 | 79642 | 39875 | 38387 | 26638 |

| Age, year | 61.5 (9.4) | 66.0 (10.6) | 66.7 (10.4) | 65.4 (10.7) | 66.0 (10.4) | 64.3 (10.9) | 65.3 (10.5) | 64.5 (10.8) | 63.1 (10.8) |

| Male, % | 3.1 | 33.7 | 36.2 | 43.6 | 48.8 | 55.1 | 55.9 | 59.5 | 59.8 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.7 (5.6) | 26.3 (4.5) | 25.6 (4) | 25.1 (3.7) | 24.9 (3.5) | 24.7 (3.4) | 24.5 (3.4) | 24.4 (3.4) | 24.2 (3.6) |

| White, % | 96.2 | 96.7 | 96.9 | 96.7 | 96.2 | 96.1 | 95.7 | 95.6 | 94.6 |

| Calorie, kcal/day | 1680 (455) | 1815 (503) | 1845 (493) | 1869 (506) | 1904 (519) | 1910 (531) | 1922 (536) | 1958 (550) | 2012 (590) |

| Alcohol, g/day | 6.0 (11.1) | 7.4 (11.4) | 7.8 (10.7) | 8.3 (10.7) | 8.8 (11) | 9.5 (11.7) | 9.3 (11.2) | 9.6 (11.3) | 9.4 (11.9) |

| AHEI score | 49.8 (9.6) | 51.1 (9.6) | 54.3 (9.5) | 55.9 (9.8) | 57.0 (9.9) | 57.6 (10) | 58.3 (10) | 58.6 (10) | 59.0 (10.3) |

| Sleep (7–8 hour/week), % | 54.7 | 49.0 | 52.0 | 49.3 | 48.1 | 45.4 | 45.9 | 43.5 | 38.1 |

| Family history of MI, % | 38.5 | 35.3 | 35.4 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 34.3 | 34.1 | 35.2 | 34.8 |

| Family history of cancer, % | 39.5 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 29.9 | 28.8 | 27.2 | 27.5 | 26.0 | 24.2 |

| Smoking, % | |||||||||

| Never | 44.4 | 45.3 | 46.6 | 46.7 | 47.0 | 47.3 | 47.8 | 47.5 | 50.7 |

| Past | 38.8 | 43.3 | 45.1 | 45.1 | 45.2 | 44.5 | 43.9 | 43.6 | 40.7 |

| Current | 13.5 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.6 |

| Total PA, hour/week | 1.9 (2.5) | 2.8 (2.7) | 4.8 (2.7) | 6.4 (2.9) | 8.1 (3.0) | 9.2 (3.2) | 11.0 (3.3) | 12.7 (3.5) | 18.9 (7.3) |

| MPA, hour/week | 1.9 (2.5) | 2.4 (2.6) | 3.0 (2.6) | 3.4 (2.8) | 3.8 (2.9) | 3.7 (3.2) | 4.2 (3.3) | 4.2 (3.4) | 5.2 (4.2) |

| VPA, hour/week | 0 | 0.4 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) | 5.5 (0.4) | 6.8 (0.4) | 8.5 (0.7) | 13.7 (5.4) |

|

| |||||||||

| Moderate Physical Activity (min/week) | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PA guideline | 0–19 Inactive | 20–74 Insufficient | 75–149 Insufficient | 150–224 Sufficient | 225–299 ×1.5 | 300–374 ×2 | 375–449 ×2.5 | 450–599 ×3 | ≥600 ×4 or more |

|

| |||||||||

| Person-years | 318798 | 736140 | 686117 | 480277 | 260727 | 198179 | 101430 | 118494 | 84382 |

| Age, year | 60.9 (10.6) | 64.2 (10.5) | 66.9 (10.2) | 66.9 (10.3) | 68.7 (9.8) | 67.0 (10.5) | 68.7 (10.1) | 68.1 (10.6) | 67.9 (10.8) |

| Male, % | 34.2 | 27.0 | 30.9 | 35.7 | 39.8 | 46.8 | 52.3 | 62.1 | 76.9 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.8 (5.2) | 26.5 (4.8) | 25.9 (4.2) | 25.6 (4.0) | 25.4 (3.8) | 25.3 (3.7) | 25.4 (3.8) | 25.3 (3.6) | 25.4 (3.7) |

| White, % | 95.0 | 96.7 | 97.1 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 95.8 | 95.6 |

| Calorie, kcal/day | 1735 (501) | 1772 (482) | 1814 (484) | 1842 (496) | 1886 (507) | 1902 (524) | 1941 (534) | 1990 (558) | 2086 (599) |

| Alcohol, g/day | 6.9 (11.9) | 6.6 (10.7) | 7.1 (10.5) | 7.8 (11) | 8.2 (11.1) | 9.0 (12) | 9.4 (12) | 10.2 (12.9) | 11.4 (13.8) |

| AHEI score | 49.5 (9.9) | 51.0 (9.4) | 52.9 (9.5) | 54.0 (9.7) | 54.6 (9.8) | 54.9 (10.1) | 54.7 (10.2) | 54.7 (10.4) | 54.1 (10.7) |

| Sleep (7–8 hour/week), % | 39.6 | 49.1 | 52.0 | 51.6 | 52.7 | 49.0 | 51.2 | 46.8 | 38.2 |

| Family history of MI, % | 36.1 | 36.0 | 35.5 | 35.6 | 34.8 | 34.5 | 34.1 | 33.5 | 31.7 |

| Family history of cancer, % | 30.6 | 33.5 | 32.1 | 31.2 | 30.5 | 28.2 | 27.9 | 25.4 | 21.3 |

| Smoking, % | |||||||||

| Never | 42.9 | 45.8 | 46.8 | 46.3 | 46.8 | 45.5 | 45.2 | 45.5 | 44.8 |

| Past | 41.5 | 43.0 | 44.3 | 44.6 | 44.7 | 44.8 | 44.7 | 43.3 | 42.4 |

| Current | 11.0 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 7.6 |

| Total PA, hour/week | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.9) | 4.7 (2.2) | 6.2 (2.3) | 7.4 (2.7) | 9.0 (2.8) | 10.7 (3.3) | 14.9 (5.1) |

| MPA, hour/week | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.4) | 6.8 (0.3) | 8.5 (0.6) | 12.8 (2.4) |

| VPA, hour/week | 0.8 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.8) | 1.7 (2.1) | 1.9 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.4) | 2.2 (2.7) | 2.3 (3.1) | 2.5 (4.3) |

Abbreviations: AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index; MI, myocardial infarction; MPA, Moderate intensity physical activity; PA, physical activity; VPA, Vigorous intensity physical activity.

Data were updated over the follow up

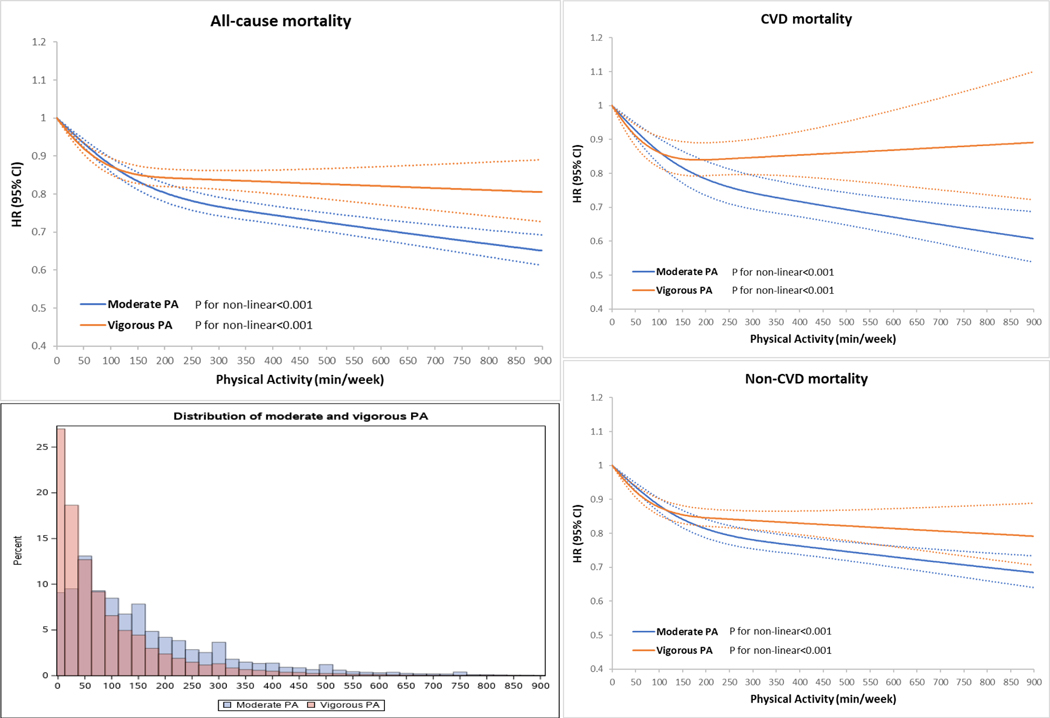

During 2,984,545 person-years of follow-up (median of 26 years), we documented 47,596 deaths. Compared to those with no long-term leisure-time VPA, participants who met the long-term leisure-time physical activity guideline (75–149 min/week of VPA) had 19% lower all-cause mortality (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.76–0.87), 31% lower CVD mortality (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.60–0.78) and 15% lower non-CVD mortality (HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.79–0.92) (Table 2). Participants who reported 2 to 4 times the recommended minimum of long-term leisure-time VPA (150–299 min/week) was associated with further lower mortality (i.e., approximately 21–23% lower all-cause mortality, 27–33% lower CVD mortality, and 19% lower non-CVD mortality). Higher levels of long-term leisure-time VPA (≥300 min/week) did not show further lower mortality. In the restricted cubic spline models, long-term leisure-time VPA was associated with substantially lower risk of all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality and the inverse association for long-term leisure-time VPA tended to level off in the higher range (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Associations between long-term leisure-time VPA and all-cause and cause-specific mortality (pooled results of HPFS and NHS, 1988–2018)

| Outcome | Deaths | Person years | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| VPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0 | 1194 | 91573 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1–74 | 31297 | 1776378 | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) |

| 75–149 | 7907 | 539846 | 0.50 (0.47–0.53) | 0.81 (0.76–0.87) |

| 150–224 | 3494 | 269767 | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) |

| 225–299 | 1595 | 122439 | 0.46 (0.43–0.50) | 0.77 (0.72–0.84) |

| 300–374 | 937 | 79642 | 0.47 (0.43–0.51) | 0.78 (0.72–0.85) |

| 375–449 | 459 | 39875 | 0.43 (0.38–0.48) | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) |

| 450–599 | 444 | 38387 | 0.45 (0.40–0.50) | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) |

| ≥600 | 269 | 26638 | 0.45 (0.39–0.51) | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| VPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0 | 285 | 92503 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1–74 | 6896 | 1805615 | 0.56 (0.50–0.64) | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) |

| 75–149 | 1625 | 547572 | 0.44 (0.39–0.50) | 0.69 (0.60–0.78) |

| 150–224 | 788 | 273018 | 0.45 (0.40–0.52) | 0.73 (0.64–0.85) |

| 225–299 | 341 | 123927 | 0.40 (0.34–0.47) | 0.67 (0.57–0.79) |

| 300–374 | 203 | 80485 | 0.39 (0.33–0.47) | 0.68 (0.56–0.82) |

| 375–449 | 105 | 40288 | 0.38 (0.31–0.48) | 0.65 (0.52–0.82) |

| 450–599 | 99 | 38787 | 0.37 (0.29–0.47) | 0.67 (0.53–0.84) |

| ≥600 | 68 | 26886 | 0.41 (0.31–0.54) | 0.71 (0.54–0.93) |

| Non-CVD mortality | ||||

| VPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0 | 909 | 91874 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1–74 | 24401 | 1784220 | 0.65 (0.61–0.70) | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) |

| 75–149 | 6282 | 541810 | 0.53 (0.49–0.57) | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) |

| 150–224 | 2706 | 270676 | 0.50 (0.46–0.54) | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) |

| 225–299 | 1254 | 122803 | 0.50 (0.45–0.54) | 0.81 (0.74–0.89) |

| 300–374 | 734 | 79866 | 0.51 (0.46–0.56) | 0.82 (0.74–0.91) |

| 375–449 | 354 | 39988 | 0.45 (0.40–0.51) | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) |

| 450–599 | 345 | 38507 | 0.49 (0.43–0.55) | 0.80 (0.70–0.90) |

| ≥600 | 201 | 26704 | 0.47 (0.40–0.55) | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; MPA, Moderate intensity physical activity; VPA, Vigorous intensity physical activity. We applied 2-year lag time between physical activity assessment and the time at risk of death.

Multivariable-adjusted model used Cox regression model using age (month) as time scale with stratification by calendar time (year) and cohort, and additionally adjusted for race (white or non-white), family history of cardiovascular disease (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), postmenopausal hormone use (women only) (premenopausal, postmenopausal current user, or postmenopausal never/past user), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–14.9, or 15.0+ g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), smoking status (never, past, or current: 1–14, 15–24, ≥25 cigs/day), sleep duration (≤6, 7–8, or >8 hours/day), Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles), body mass index (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, 27–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2). VPA and MPA were mutually adjusted.

Figure 1. Dose-response relationship of long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA with all-cause mortality (pooled results of HPFS and NHS, 1988–2018).

Restricted cubic spline model with 3 knots specified at 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles was performed using age (month) as time scale with stratification by calendar time (year) and cohort, and additionally adjusting for race (white or non-white), family history of cardiovascular disease (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), postmenopausal hormone use (premenopausal, postmenopausal current user, or postmenopausal never/past user), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–14.9, or 15.0+ g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), smoking status (never, past, or current: 1–14, 15–24, ≥25 cigs/day), sleep duration (≤6, 7–8, or ≥8 hours/day), Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles), body mass index (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, 27–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2). VPA and MPA were mutually adjusted.

In terms of long-term leisure-time MPA, compared to those with almost no long-term leisure-time MPA, participants who met the long-term leisure-time physical activity guideline (150–224 and 225–299 min/week of MPA) had 20–21% lower all-cause mortality (HR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.77–0.83; HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.76–0.82), 22–25% lower CVD mortality (HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.84; HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.68–0.82) and 19–20% lower non-CVD mortality (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.78–0.85; HR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.77–0.84) (Table 3). Participants who reported 2 to 4 times the recommend minimum of long-term leisure-time MPA (300–599 min/week) had gradually 3–13% further lower mortality (i.e., approximately 26–31% lower all-cause mortality, 28–38% lower CVD mortality, and 25–27% lower non-CVD). Higher level of long-term leisure-time MPA (≥600 min/week) showed similar associations with mortality as those achieving 300–599 min/week. In the restricted cubic spline models, long-term leisure-time MPA was associated with substantially lower risk of all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality and the inverse association for long-term leisure-time MPA continued to strengthen over the entire range of activity assessed in the cohort (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Associations between long-term leisure-time MPA and all-cause and cause-specific mortality (pooled results of HPFS and NHS, 1988–2018)

| Outcome | Deaths | Person years | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| MPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0–19 | 4606 | 318798 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 20–74 | 11143 | 736140 | 0.75 (0.72–0.78) | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) |

| 75–149 | 11158 | 686117 | 0.62 (0.60–0.64) | 0.84 (0.81–0.88) |

| 150–224 | 7451 | 480277 | 0.57 (0.55–0.60) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) |

| 225–299 | 4586 | 260727 | 0.55 (0.53–0.57) | 0.79 (0.76–0.82) |

| 300–374 | 3111 | 198179 | 0.54 (0.51–0.56) | 0.74 (0.70–0.77) |

| 375–449 | 1843 | 101430 | 0.53 (0.50–0.56) | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) |

| 450–599 | 2135 | 118494 | 0.51 (0.48–0.54) | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) |

| ≥600 | 1563 | 84382 | 0.51 (0.49–0.55) | 0.68 (0.64–0.73) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| MPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0–19 | 1050 | 322738 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 20–74 | 2344 | 746570 | 0.73 (0.67–0.78) | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) |

| 75–149 | 2295 | 697063 | 0.58 (0.54–0.62) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) |

| 150–224 | 1632 | 487337 | 0.55 (0.51–0.60) | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) |

| 225–299 | 1016 | 265158 | 0.52 (0.47–0.57) | 0.75 (0.68–0.82) |

| 300–374 | 738 | 201109 | 0.51 (0.46–0.56) | 0.72 (0.65–0.79) |

| 375–449 | 441 | 103025 | 0.49 (0.44–0.55) | 0.71 (0.63–0.79) |

| 450–599 | 499 | 120364 | 0.44 (0.40–0.49) | 0.62 (0.55–0.69) |

| ≥600 | 395 | 85717 | 0.46 (0.41–0.52) | 0.63 (0.56–0.71) |

| Non-CVD mortality | ||||

| MPA (minutes/week) | ||||

| 0–19 | 3556 | 319904 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 20–74 | 8799 | 738754 | 0.76 (0.73–0.79) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) |

| 75–149 | 8863 | 688821 | 0.64 (0.61–0.66) | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) |

| 150–224 | 5819 | 482197 | 0.59 (0.56–0.61) | 0.81 (0.78–0.85) |

| 225–299 | 3570 | 261938 | 0.57 (0.54–0.59) | 0.80 (0.77–0.84) |

| 300–374 | 2373 | 198983 | 0.55 (0.52–0.58) | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) |

| 375–449 | 1402 | 101948 | 0.55 (0.51–0.58) | 0.75 (0.71–0.80) |

| 450–599 | 1636 | 119083 | 0.54 (0.51–0.58) | 0.73 (0.68–0.77) |

| ≥600 | 1168 | 84819 | 0.54 (0.51–0.58) | 0.71 (0.67–0.76) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; MPA, Moderate intensity physical activity; VPA, Vigorous intensity physical activity. We applied 2-year lag time between physical activity assessment and the time at risk of death.

Multivariable-adjusted model used Cox regression model using age (month) as time scale with stratification by calendar time (year) and cohort, and additionally adjusted for race (white or non-white), family history of cardiovascular disease (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), postmenopausal hormone use (women only) (premenopausal, postmenopausal current user, or postmenopausal never/past user), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–14.9, or 15.0+ g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), smoking status (never, past, or current: 1–14, 15–24, ≥25 cigs/day), sleep duration (≤6, 7–8, or >8 hours/day), Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles), body mass index (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, 27–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2). VPA and MPA were mutually adjusted.

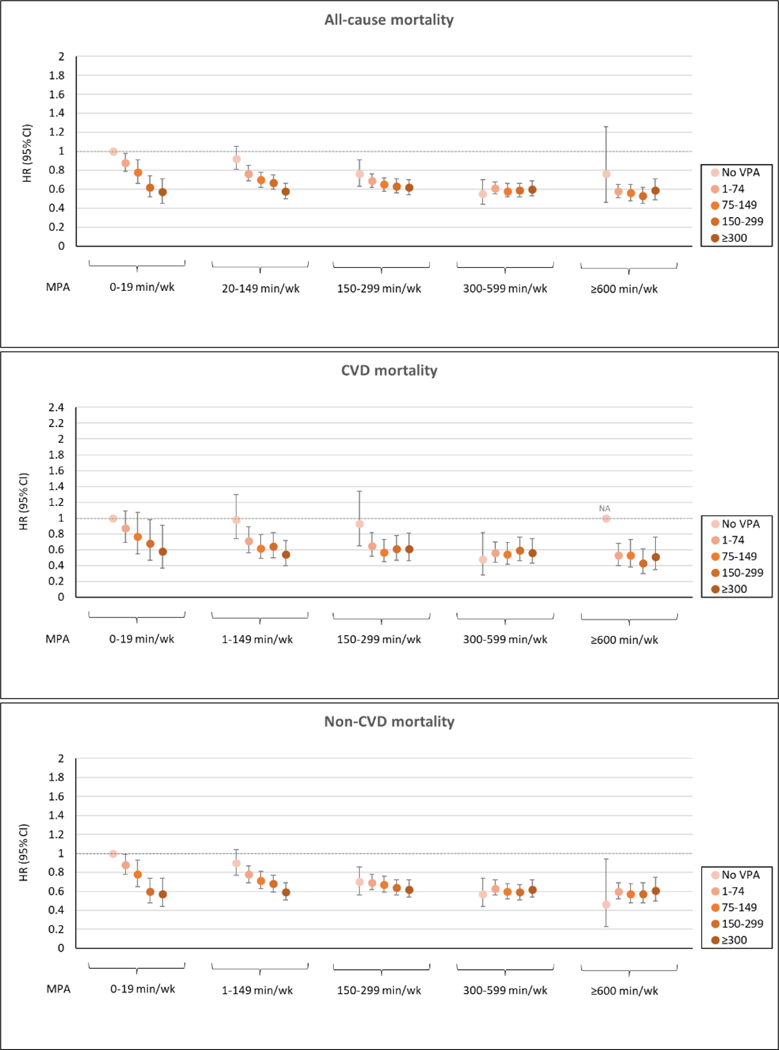

In the joint analyses of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA, a strong inverse association between VPA and all-cause and cause-specific mortality was found among those who had insufficient long-term leisure-time MPA (<150 min/week) while a weaker inverse association was shown among those who met the long-term leisure-time MPA guideline (Figure 2). There was no clear inverse association of long-term leisure-time VPA among those who met 2+ times the long-term leisure-time MPA guideline. In the stratified analyses, an inverse association of long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA with all-cause mortality was consistently found regardless of age, sex, body mass index, smoking and alcohol intake (Supplementary Table 1). However, the inverse association tended to be stronger among individuals with lower BMI.

Figure 2. Joint association of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA with all-cause and cause-specific mortality (pooled results of HPFS and NHS, 1988–2018).

Multivariable-adjusted model used Cox regression model using age (month) as time scale with stratification by calendar time (year) and cohort, and additionally adjusted for race (white or non-white), family history of cardiovascular disease (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), postmenopausal hormone use (women only) (premenopausal, postmenopausal current user, or postmenopausal never/past user), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–14.9, or 15.0+ g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), smoking status (never, past, or current: 1–14, 15–24, ≥25 cigs/day), sleep duration (≤6, 7–8, or >8 hours/day), Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles), body mass index (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, 27–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2). NA, not available due to insufficient power (less than 10 deaths).

In sensitivity analyses, the association between long-term leisure-time VPA, MPA and mortality was consistent without adjustment for BMI/calorie intake or with additional adjustment for physical limitation. When excluding participants with no physical activity, long-term leisure-time MPA showed similar associations with mortality but long-term leisure-time VPA tended to show more clearly that high levels of VPA do not provide additional benefit (Supplementary Table 2). Compared to the cumulative average of repeated physical activity measures, use of single measure at baseline showed weaker inverse associations with mortality and tended to show a U-shaped association (Supplementary Table 3). However, use of cumulative average of first 10 and 20 years of physical activity measures showed consistently inverse associations with mortality with no clear indication of higher mortality in the higher range of physical activity. In secondary analyses using proportion of VPA to total physical activity, compared to those with no long-term leisure-time VPA, participants with any long-term leisure-time VPA had lower all-cause and cause-specific mortality (Supplementary Table 4). However, participants reporting more than 25% of long-term leisure-time VPA did not show further lower mortality. The joint analyses of long-term leisure-time proportion of VPA and total physical activity showed that higher proportion of long-term leisure-time VPA was inversely associated with mortality among those who had insufficient (1–149 min/week) or met the physical activity guideline (150–299 min/week) (Supplementary Figure 1). Higher long-term leisure-time proportion of VPA was not associated with further lower mortality among active participants with 2+ times the physical activity guideline.

In additional analyses of using incident CVD outcome, an inverse association of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA with CVD risk was consistently observed (Supplementary Table 5). Compared to those with no long-term leisure-time VPA, participants who met the long-term leisure-time VPA guideline (75–149 min/week of VPA) had 22% lower CVD (HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.70–0.87), 25% lower CHD (HR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64–0.87) and 14% lower stroke (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.73–1.01). Meeting the long-term leisure-time MPA guideline (150–299 min/week) showed weaker associations; 5–11% lower risk of CVD, CHD, and stroke. Participants who reported 2 to 4+ times the recommended minimum of long-term leisure-time VPA or MPA had small but additionally lower CVD and CHD risk (Supplementary Figure 2). In the joint analyses of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA, an inverse association between long-term leisure-time VPA and CVD risk was observed among those who had long-term leisure-time MPA below 300 min/week (Supplementary Figure 3). Sensitivity analyses showed similar patterns as the mortality outcomes (Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Discussion

In two large prospective cohort studies with up to 15 repeated measures of self-reported leisure-time physical activity, the nearly lowest mortality was observed among individuals who reported approximately 150–300 min/week of long-term leisure-time VPA or 300–600 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA. Higher levels of either VPA or MPA did not show clearly further lower all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality, nor harm. Moreover, for individuals who reported less than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA, additional leisure-time VPA was associated with lower mortality; however, among those who reported more than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA, additional leisure-time VPA did not appear to be associated with lower mortality beyond MPA.

Comparison with other studies

A pooled analysis of 6 cohort studies (all self-reported) showed that meeting the recommended physical activity guideline by either leisure-time MPA or VPA was associated with substantially lower risk of mortality with the maximal benefits observed at approximately 3–5 times the recommended physical activity guideline (22.5–40 MET-hour/week).7 A meta-analysis of 48 studies (5 device-based and all others self-reported) reported consistent results that high amount of total physical activity, at approximately 5–7 times the physical activity guideline, was associated with reduced risk of mortality.6 However, these studies relied on physical activity measured at a single time and the detailed association of physical activity intensity and dose with cause-specific mortality was not examined. Moreover, no studies examined the joint association of long-term VPA and MPA with mortality. Relatively little is known on the association between long-term physical activity intensity and mortality.10 A review of 5 prospective cohorts showed that for the same amount of physical activity, VPA and MPA provide similar benefits on mortality reduction.10 A large study of US adults from the National Health Interview Survey also showed comparable associations between the recommendations of MPA (150–299 vs. 0 min/week) and VPA (75–149 vs 0 min/week).11 However, among participants with any physical activity, higher proportion of VPA to total physical activity (50–75%) was associated with a 17% lower risk of all-cause mortality (after adjusting for total physical activity) though no consistent inverse association was observed for CVD and cancer mortality.

Our findings are in line with the previous studies supporting the current recommended physical activity level (either MPA or VPA) for health benefits, but our study further adds new evidence that may inform the current physical activity guidelines for optimal health outcomes for the general public. First, our study leveraged repeated measures of self-reported leisure-time physical activity over decades and thus our findings better reflected one’s long-term average physical activity intensity during middle and late adulthood. In contrast, most previous studies assessed one’s physical activity intensity at one time point. A previous study evaluated the influence of biases in the physical activity-mortality analysis and found evidence that compared to use of repeated measures, use of single physical activity measure was more susceptible to measurement error and reverse causation and consequently affected the shape of the graded association, particularly in the higher level of physical activity.9 This bias in the dose-response is presumably because inconsistent or sporadic high physical activity may not represent consistently high physical activity (life-course approach). In the past several years, accelerometry-measured studies have drawn great attention because of their strength to reduce measurement error compared to studies with self-reported questionnaires.29 However, an important caveat is that almost all accelerometry studies had a single measure of physical activity at baseline and relatively short follow-up times (~5 years).30 Thus, currently these studies cannot solve the issue of inconsistent/sporadic vs. consistent/high physical activity and are at risk of reverse causation as well as measurement error to some extent.

Second, our study quantified the graded association of long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA levels above 4–8 times the recommended physical activity guidelines. Intriguingly, different shapes of the dose-response relationship for long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA were found depending on causes of death. Previous studies mainly focused on quantifying the upper threshold of benefits for total physical activity,6, 7 but it is also critical to tease out the effects of MPA and VPA to provide more refined physical activity guidelines in terms of dose and intensity. Our study supports the current physical activity guideline and further suggests that performing high level of long-term leisure-time MPA beyond 4 times the minimum recommended physical activity guideline (approximately 600 min/week of MPA) was consistently inversely associated with all-cause, CVD and non-CVD mortality. However, there was no monotonic linear inverse association across all range of long-term leisure-time VPA. The nearly maximal benefit on mortality reduction of VPA was observed around 150–300 min/week, twice the currently recommended VPA range of 75–150 min/week. There was no greater risk of mortality even at very high level of VPA though no additionally lower mortality was observed beyond 300 min/week of VPA.

Third, our joint analyses of long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA offers practical evidence on the optimal level of combined MPA and VPA. As expected, substantially lower risk of mortality was observed among individuals who had adequate levels of both long-term leisure-time MPA and VPA. More specifically, higher levels of long-term leisure-time VPA were associated with lower mortality among those with long-term leisure-time MPA levels below 300 min/week but not among those who already had high levels of long-term leisure-time MPA above 300 min/week. Similarly, higher levels of long-term leisure-time MPA were associated with lower mortality among those with long-term leisure-time VPA levels below 150 min/week but not among those who already had high levels of long-term leisure-time VPA above 150 min/week. Our findings suggest that any combinations of medium to high levels of VPA (75–300 min/week) and MPA (150–600 min/week) can provide nearly the maximum mortality reduction (approximately 35–42%). More importantly, insufficiently active people (<75 min of VPA or <150 min/week of MPA) could get greater benefits on mortality reduction (approximately 22–31%) by adding moderate levels of either VPA (75–150 min/week) or MPA (150–300 min/week). Our study provides evidence to guide generally healthy individuals to choose the right amount and intensity of physical activity over lifetime to maintain their overall health.

Our stratified analyses consistently found an inverse association between long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA and mortality regardless of age groups. There is a natural propensity toward more VPA in younger individuals and more MPA in older individuals. The similar pattern was observed in our cohorts, but there was no evidence that either long-term leisure-time VPA or MPA is particularly more strongly associated with mortality in older individuals compared to younger individuals. Our study suggests that in addition to long-term leisure-time MPA, long-term leisure-time VPA in generally healthy older adults can be an effective means of improving health.

In regards to cause-specific mortality, similar shapes of the association between long-term leisure-time VPA, MPA and different causes of mortality (e.g., CVD vs. non-CVD) were observed. It is well documented that light to moderate regular physical activity prevents CVD, but previous studies also showed evidence that long-term high intensity endurance exercise (e.g., marathons, triathlons, long distance bicycle races) may cause adverse events such as myocardial fibrosis, coronary artery calcification, atrial fibrillation as well as sudden cardiac death.12–14 Our findings on the graded association suggest that there is no harmful effect of high long-term leisure-time VPA on cardiovascular health. However, more studies, ideally with repeated objective physical activity measures and long follow-up, are needed to investigate the effect of high amount of VPA on CVD outcomes and to identify the optimal dose and intensity of long-term physical activity for health benefits.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths including a large study population, long follow-up time and detailed information on covariates. Moreover, up to 15 repeated measures of detailed leisure-time physical activity over 30 years can minimize reverse causation and within person measurement error and allow to examine the long-term associations of VPA and MPA, both separately and jointly, with mortality. There are several limitations as well. First, although our study used validated physical activity questionnaires, there is inevitable random measurement error. Moreover, non-leisure-time physical activity such as occupational and transport-related physical activity, which may have differential associations with health outcomes,31 was not reported. However, our study included health professionals and thus occupational physical activity is likely low with limited variability. Although it is the beyond the scope of our paper, cumulative average of repeated measures may not account for potential large variations of physical activity across the lifespan. In our cohorts, approximately 33–44% (MPA) and 46–62% (VPA) of participants had relatively stable physical activity over time while the other participants either decreased or increased their physical activity over time (Supplementary Table 6). This further supports the importance of utilizing repeated measures of physical activity to better understand one’s physical activity over the lifespan. Our study focused on the ‘long-term’ aspects of physical activity intensity but more studies with repeated measures are needed to explore the trajectory of physical activity intensity in relation to health outcomes. Second, given the nature of observational study, residual confounding may exist. Third, our cohorts primarily included white health professionals that may limit the generalizability of our findings; however, this may enhance internal validity by increasing adherence, more accurate reporting, and possibly lower potential for residual confounding. Also, there is no convincing evidence that the biologic relationships between physical activity and health outcomes are qualitatively different across racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Our study supports the current physical activity guideline and further suggests that the nearly maximum association with lower mortality can be achieved by performing approximately 150–300 min/week of long-term leisure-time VPA or 300–600 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA or an equivalent combination of both. There was no clear additional association beyond these levels although higher levels of long-term leisure-time VPA and MPA were consistently inversely associated with mortality. Moreover, addition of long-term leisure-time VPA was associated with substantially lower mortality for individuals who reported less than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA but no additional association of long-term leisure-time VPA was observed for those who already reported more than 300 min/week of long-term leisure-time MPA.

Supplementary Material

Clinical perspective.

What is new?

A comprehensive analysis of the association between long-term physical activity intensity and mortality using repeated measures of physical activity is lacking.

The nearly lowest risk of mortality was observed among individuals who reported approximately 150–300 min/week of long-term leisure-time vigorous physical activity or 300–600 min/week of long-term leisure-time moderate physical activity or an equivalent combination of both.

No harmful association was shown among individuals who reported more than 4 times the recommended minimum levels of long-term leisure-time moderate and vigorous physical activity.

What are the clinical implications?

These findings support the current physical activity guidelines and further suggest higher levels of long-term leisure-time vigorous and moderate physical activity to achieve the maximum benefit of mortality reduction.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the NHS and HPFS for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (UM1 CA186107, U01 CA167552 and P01 CA87969).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AHEI

Alternate Healthy Eating Index

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-up Study

- MET

Metabolic Equivalent Task

- MPA

Moderate Physical Activity

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- VPA

Vigorous Physical Activity

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT and Group LPASW. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The lancet. 2012;380:219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM and Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama. 2018;320:2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitti A, Nikolaidis PT, Villiger E, Onywera V and Knechtle B. The “New York City Marathon”: participation and performance trends of 1.2 M runners during half-century. Research in Sports Medicine. 2020;28:121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knechtle B, Di Gangi S, Rüst CA, Rosemann T and Nikolaidis PT. Men’s participation and performance in the Boston marathon from 1897 to 2017. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;39:1018–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMullen CW, Harrast MA and Baggish AL. Optimal running dose and cardiovascular risk. Current sports medicine reports. 2018;17:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blond KA-Ohoo Brinklov CF, Ried-Larsen MA-Ohoo, Crippa A and Grontved A. Association of high amounts of physical activity with mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. . Br J Sports Med. 2019;bjsports-2018–100393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A, Hartge P, De Gonzalez AB, Visvanathan K, Campbell PT, Freedman M, Weiderpass E and Adami HO. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175:959–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnohr P, O’Keefe JH, Lavie CJ, Holtermann A, Lange P, Jensen GB and Marott JL. U-Shaped Association Between Duration of Sports Activities and Mortality: Copenhagen City Heart Study. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2021;96:3012–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DH, Rezende LF, Ferrari G, Aune D, Keum N, Tabung FK and Giovannucci EL. Physical activity and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: assessing the impact of reverse causation and measurement error in two large prospective cohorts. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2021;36:275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez JPR, Sabag A, Juan MM, Rezende LF and Pastor-Valero M. Do vigorous-intensity and moderate-intensity physical activities reduce mortality to the same extent? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2020;6:e000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Nie J, Ferrari G, Rey-Lopez JP and Rezende LFM. Association of Physical Activity Intensity With Mortality: A National Cohort Study of 403 681 US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Gerche A, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, Inder WJ, Taylor AJ, Bogaert J, MacIsaac AI, Heidbüchel H and Prior DL. Exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction and structural remodelling in endurance athletes. European heart journal. 2012;33:998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Keefe JH, Patil HR, Lavie CJ, Magalski A, Vogel RA and McCullough PA. Potential adverse cardiovascular effects from excessive endurance exercise. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87:587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Möhlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Breuckmann F, Bröcker-Preuss M, Nassenstein K, Halle M, Budde T, Mann K, Barkhausen J and Heusch G. Running: the risk of coronary events: prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. European heart journal. 2008;29:1903–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, Rosner B, Kriska A and Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. International journal of epidemiology. 1994;23:991–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Ascherio A and Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology. 1996:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Shaar L, Pernar CH, Chomistek AK, Rimm EB, Rood J, Stampfer MJ, Eliassen AH, Barnett JB and Willett WC. Reproducibility, Validity, and Relative Validity of Self-Report Methods for Assessing Physical Activity in Epidemiologic Studies: Findings From the Women’s Lifestyle Validation Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2022;191:696–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pernar CH, Chomistek AK, Barnett JB, Ivey K, Al-Shaar L, Roberts SB, Rood J, Fielding RA, Block J, Li R, Willett WC, Parmigiani G, Giovannucci EL, Mucci LA and Rimm EB. Validity and Relative Validity of Alternative Methods to Assess Physical Activity in Epidemiologic Studies: Findings from the Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs JD, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF and Paffenbarger JR. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1993;25:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB and Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1993;93:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B and Willett WC. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. International journal of epidemiology. 1989;18:858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH and Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;122:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ and Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142:1009–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA and Stampfer MJ. Test of the national death index and Equifax nationwide death search. American journal of epidemiology. 1994;140:1016–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Dysert DC, Lipnick R, Rosner B and Hennekens CH. Test of the National Death Index. American journal of epidemiology. 1984;119:837–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendis S, Thygesen K, Kuulasmaa K, Giampaoli S, Mähönen M, Ngu Blackett K and Lisheng L. World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008–09 revision. International journal of epidemiology. 2011;40:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker AE, Robins M and Weinfeld FD. The National Survey of Stroke. Clinical findings. Stroke. 1981;12:I13–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrie RA, Dawson NV and Garland A. Quantile regression and restricted cubic splines are useful for exploring relationships between continuous variables. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2009;62:511–517. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW, Whincup P, Diaz KM, Hooker SP, Chernofsky A, Larson MG, Spartano N, Vasan RS, Dohrn IM, Hagstromer M, Edwardson C, Yates T, Shiroma E, Anderssen SA and Lee IM. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. Bmj. 2019;366:l4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezende LF, Lee DH, Ferrari G and Giovannucci E. Confounding due to pre-existing diseases in epidemiologic studies on sedentary behavior and all-cause mortality: a meta-epidemiologic study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2020;52:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holtermann A, Krause N, van der Beek AJ and Straker L. The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:149–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.