Abstract

Objective:

This study sought to characterize change mechanisms that underlie GI symptom improvement in IBS patients undergoing two dosages of CBT for IBS as compared to a nondirective education/support (EDU) condition.

Method:

Data were collected in the context of a large RCT that randomized 436 Rome III-diagnosed IBS patients (M age = 41, 80 % female) to standard, clinic-based CBT (S-CBT), a largely home-based version with minimal therapist contact (MC-CBT) or Education that controlled for nonspecific effects. Outcome was measured with the IBS-version of the Clinical Global Improvement scale that was administered at week 5 and two weeks post-treatment (week 12). Potential mediators (IBS-Self efficacy (IBS-SE), pain catastrophizing, fear of GI symptoms and treatment alliance were assessed at weeks 3, 5, 8 during treatment with the exception of treatment expectancy that was measured at the end of session 1.

Results:

IBS-SE, a positive treatment expectancy, and patient-therapist agreement on how to achieve goals mediated effects of CBT early in treatment (rapid response, RR) and at post-treatment. Notwithstanding their different intensities, both CBT conditions had comparable RR rates (43–45%) and significantly greater than the EDU RR rate of 22%. While pain catastrophizing, fear of GI symptoms, and patient-therapist emotional boding related to post treatment symptom improvement, none of these hypothesized mediators explained differences between CBT and EDU, thereby lacking the mechanistic specificity of IBS-SE, task agreement, and treatment expectancy

Conclusion:

Findings suggest that CBT-induced symptom changes may be mediated by a constellation of CBT-specific (IBS-SE) and non-specific (task agreement, treatmentexpectancy) processes that reciprocally influence each other in complex ways to catalyze, improve, and sustain GI symptom relief.

Keywords: early response, chronic pain, treatment expectancy, working alliance, psychotherapy process

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder whose core symptoms – abdominal pain associated with stool irregularities (e.g., diarrhea, constipation, or both) – affect 40 million Americans. As the most prevalent of all GI disorders, IBS ranks high among reasons for physician visits (Sandler, 1990) and medical costs (1$ billion annually) in terms of medical treatment and procedures (Cash, Sullivan, & Barghout, 2005; Everhart & Ruhl, 2009; Ford, Harris, Lacy, Quigley, & Moayyedi, 2018), work absenteeism (Hahn, Yan, & Strassels, 1999), and nonmonetary costs such as psychological distress (Drossman et al., 1999; Lackner et al., 2013; Whitehead, Bosmajian, Zonderman, Costa, & Schuster, 1988) and diminished quality of life(Lackner et al., 2006; Whitehead, Burnett, Cook, & Taub, 1996) that rivals that of life threatening disease states including diabetes and hepatitis (Enck et al., 2016). Although some patients with specific IBS symptoms may respond to certain medications, no single medication— or class of medications —has been demonstrated to relieve the full spectrum of symptoms (Jailwala, Imperiale, & Kroenke, 2000).

Lacking a reliable biomarker, IBS is best understood as the product of dysregulation in the bi-directional neural connections (brain-gut axis) linking the gut to the cognitive and emotional centers in the brain (Mayer, Labus, Tillisch, Cole, & Baldi, 2015; Mayer & Tillisch, 2011). Alterations at any level of the brain-gut axis influence key pathophysiological processes (motility, visceral sensitivity, blood flow, secretion, Enck et al., 2016; Holtmann, Shah, & Morrison, 2017), but multiple lines of evidence (Mayer et al., 2019) highlight the importance of central processes (eg, restricted coping, stress reactivity, perceptual biases) in the perception and maintenance of symptoms, particularly among treatment seeking individuals who bear the greatest symptom burden in quality of life impairment, distress, and symptom severity

One measure of the influence of central factors on IBS comes from research validating the efficacy of psychological therapies of which cognitive behavioral therapy is the most rigorously studied. A recently completed NIH-funded multisite trial (Lackner et al., 2018) called the IBS Outcome Study (IBSOS) supports the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) whether delivered face-to-face over 10 weekly sessions (Standard or S-CBT) or primarily home-based with minimal therapeutic contact (MC-CBT) during 4 sessions. MC-CBT produced a statistically significant (p < .05) larger percent of treatment responders than a non-specific education/support comparator (EDU) at immediate post-treatment whether rated by patients (61.0% vs. 43.5%) or study gastroenterologists blind to treatment assignment (55.7% vs. 40.4%) at post treatment. Treatment response was largely maintained with negligible decay at quarterly intervals for 12 months (Lackner, Jaccard, Radziwon, et al., 2019). The version of CBT validated in the IBSOS and the focus of this study is the only psychological treatment for IBS that has met “strong evidence” criteria for an empirically validated treatment as specified by Division 12 of the American Psychological Association (Society of Clinical Psychology (Division 12), 2020). Its overall efficacy profile (i.e. IBS symptom improvement, onset of action, and long-term durability) is unmatched by dietary and pharmacological alternatives.

That said, a significant proportion of patients (40%) either do not respond or do not respond well enough for GI symptom change to register as clinically meaningful improvement. One pathway for improving the efficacy of CBT for IBS is to identify mediators of treatment outcome so that those mechanisms can be directly addressed to render more robust effect sizes or effect sizes of similar magnitude at lower personal or economic cost (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). Specifying the reasons that CBT for IBS works may help clarify (1) factors that maintain symptoms and (2) treatment components critical to facilitating symptomatic improvement. Rather than delivering inert, redundant, or even counterproductive procedures, clinicians and researchers can work toward refining and implementing “active” components with the greatest potency (Kazdin & Nock, 2003).

Treatment Mediators

Unfortunately, the search for why and how CBT works has generally eluded IBS researchers whose primary focus has, with some exceptions (Chilcot & Moss-Morris, 2013; Hesser, Hedman-Lagerlof, Andersson, Lindfors, & Ljotsson, 2018; Hesser, Hedman, Lindfors, Andersson, & Ljotsson, 2017; Hunt, Moshier, & Milonova, 2009; M. Jones, Koloski, Boyce, & Talley, 2011; Lackner et al., 2007; Ljotsson et al., 2013; Reme et al., 2011; Windgassen et al., 2017; Windgassen, Moss-Morris, Goldsmith, & Chalder, 2019) concerned the question of whether a given therapy “works”. One relatively well-conceived study (Hesser et al., 2018) highlighted fear of GI symptoms among other putative mediators (e.g. self-efficacy) as a change mechanism for the effect of internet-delivered exposure on behavioral avoidance in IBS patients. Whether this pattern of data applies to a broader (i.e., non-exposure-based) set of behavioral regimens that prioritize treatment goals (ie, GI symptom relief, J. M. Harvey et al., 2018) deemed most important to patients (Drossman et al., 2009) and physicians (Ford, Lacy, & Talley, 2017) is unknown.

Complicating the interpretability of this study is the investigators’ choice of measures from their mediator pool; for example, they inferred self-efficacy from a global measure of personal competence (PC) drawn from self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000). PC refers to perceptions of one’s capacity to achieve a desired outcome (Williams & Deci, 1996; Williams, Freedman, & Deci, 1998). High personal competence for IBS is reflected in thoughts such as “I am able to meet the challenge of managing IBS symptoms” or “I now feel capable of managing IBS symptoms”. In contrast, self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997) emphasizes efficacy expectancies (i.e. one’s confidence to carry out specific behaviors (Bandura, 1986)) over expected outcomes as the primary explanatory construct of symptom self-management. An individual with strong self-efficacy holds a pattern of efficacy expectancies defining his/her capacity to self-manage symptoms as, for example, “if I can catch IBS symptoms early or before they begin, I often can stop them from becoming problems” or “I can control bowel symptoms by recognizing their triggers” (Lackner, Krasner, & Holroyd, 2004). This subtle difference makes the two constructs to some extent conceptually if not empirically independent (Rodgers, Markland, Selzler, Murray, & Wilson, 2014). Because self-efficacy expectancies are more task-specific than perceived competence (Sweet, Fortier, Strachan, & Blanchard, 2012), they are more closely aligned with CBT’s goals which, in the case of this study, is to cultivate specific behavioral skills for relieving refractory IBS symptoms. We would therefore expect a sense of personal competence to have limited mediational value in explaining CBT’s effects relative to self-efficacy.

In the context of physical health problems, self-efficacy (SE) plays a significant role in influencing how people adjust to painful medical problems (Bandura, 1991; Buckelew et al., 1994; Keefe et al., 2003; Lorig & Holman, 1989). Individuals with high SE are more likely to believe they can carry out the requisite behaviors to control and manage physical symptoms(e.g., pain, health anxiety, Bandura, 1977; Bandura, 1986; Drossman et al., 2000; Holroyd, Nash, Pingel, Cordingley, & Jerome, 1991; Holroyd & Penzien, 1983; Holroyd et al., 1984; Sullivan et al., 2001). Those reporting higher levels of self-efficacy report lower pain levels of pain, less emotional distress, and fewer negative medical outcomes (Keefe, Rumble, Scipio, Giordano, & Perri, 2004). It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that a mechanism through which CBT improves GI symptoms is by promoting confidence in one’ ability to self-manage IBS symptoms (i.e. IBS SE).

In addition to IBS self-efficacy and fear of GI symptoms, the present research explores three potential mediators of CBT for IBS: (a) pain catastrophizing; (b) therapeutic alliance, and (c) treatment expectancies. We discuss each, in turn.

Pain Catastrophizing.

Pain catastrophizing refers to the tendency to magnify the threat value of pain sensation, to respond to pain with a sense of helplessness, and difficulty controlling pain-related thoughts in anticipation of, during or after a pain episode. Its consistent and relatively strong association with intensified pain, distress, and functional limitations (Sullivan et al., 2001) across multiple pain disorders, including IBS (Lackner, Quigley, & Blanchard, 2004), makes pain catastrophizing one of the most robust psychological features of chronic pain patients (Trost et al., 2015). To the extent that an efficacious regimen of CBT reduces painful symptoms (Eccleston, Williams, & Morley, 2009), it may do so through cognitive change strategies that teach patients to challenge and dispute the catastrophic content of pain cognitions.. If so, we would expect that pain catastrophizing accounts for improvement of IBS whose cardinal symptom is abdominal pain (Camilleri, 2018) That said, to the extent that catastrophizing is largely an outcome expectancy (i.e., belief that a particular outcome will occur, as for example, “when I feel pain it is terrible”), then it may have less mechanistic strength than an efficacy expectancy like SE that are regarded as more robust predictors of behavior (Lackner, Carosella, & Feuerstein, 1996). Further, while hailed as “key for achieving treatment success” (p. 2, Crombez et al., 2020), pain catastrophizing has not distinguished itself as being a change mechanism with any specificity for CBT (J. W. Burns, Day, & Thorn, 2012; J. W. Burns, Van Dyke, Newman, Morais, & Thorn, 2020; Turner et al., 2016). Further, it has recently received criticism for its construct and content validity (Crombez et al., 2020), raising questions about how a concept that is neither well operationalized nor assessed can effectively underpin behavioral pain treatments such as CBT for IBS.

Therapeutic Alliance.

CBT effects are often attributed to its influence on nonspecific factors that are “common” across different psychotherapies (Beitman, Goldfried, & Norcross, 1989; Frank, 1961; Frank & Frank, 1993; Goldfried, 1980; Wampold, 2001) and unrelated to therapeutic orientation or procedure. One such factor is therapeutic alliance, which refers to the emotional bond that develops between client and therapist and their collaborative work on mutually agreed upon tasks toward shared goals (Bordin, 1979; Krupnick et al., 1996; Waddington, 2002). Meta analyses on the salutary effects of therapeutic alliance on outcomes following psychotherapy have yielded small to moderate effect sizes of about d = 0.25 (Horvath, Del Re, Fluckiger, & Symonds, 2011; Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000). To the extent that treatment necessarily plays out in a relational context, the therapeutic alliance may be a particularly important change mechanism in the psychological treatment of IBS given interpersonal problems can potentiate symptom onset (Gwee et al., 1996) and are linked to cognitive-affective processes (e.g., pain catastrophizing) that modulate illness experience (Lackner & Gurtman, 2004).

Because one of the CBT conditions of our study was a primarily home-based behavioral treatment that included only four one hour sessions (MC-CBT), one could argue that it provides insufficient opportunities for fostering a strong therapeutic alliance than the more standard 10 sessions version that meets weekly for 10 weeks (S-CBT). The additional sessions of S-CBT may provide sufficient structure, guidance, and support for skills building, engender trust and confidence (i.e. SE), and support around stressful life circumstances that MC CBT patients have to navigate independently. Patients assigned to home-based CBT, on the other hand, are introduced to skills training in one of four clinic sessions and are provided corrective feedback regarding compliance with home exercises in two 5–10 min telephone calls. Otherwise, learning is largely self-directed through the use of home study materials (Lackner & Holroyd, 2010). To the extent that the alliance produces therapeutic change, then we would expect greater symptom improvement among S-CBT patients than MC-CBT patients based on the number of treatment sessions (10 v 4). This hypothesis is consistent with broader literature that the magnitude of symptom relief is a function of session frequency (Falkenström, Josefsson, Berggren, & Holmqvist, 2016; Rutherford, Tandler, Brown, Sneed, & Roose, 2014). Alternatively, the therapeutic value of alliance may not depend on the total number of interactions over time but the timing of quality interactions (Barber & DeRubeis, 2001) that engages the collaborative force of key aspect(s) of alliance, particularly early on when its therapeutic potential has greatest strategic value (Hersoug, Hoglend, Havik, von der Lippe, & Monsen, 2009; Horvath, 2001).

If the quality of alliance established early on is critical to the success of therapy (Hersoug, Monsen, Havik, & Hoglend, 2002), then the number or frequency of face-to-face sessions distinguishing MC- and S-CBT may be less clinically significant than what transpires at strategic sessions early on when patients are introduced to therapy and oriented to what it entails. That said, early strong initial alliance may not necessarily be therapeutic if it simply reflects unrealistic treatment expectations that potentiate negative outcome, premature termination and dropout (Mohl, Martinez, Ticknor, Huang, & Cordell, 1991; Sharf, Primavera, & Diener, 2010). None of these alliance issues have been explored in the context of psychotherapy trials for IBS or other behavioral pain treatments. It is also unclear how alliance works together with treatment-specific factors (e.g. SE) to produce therapeutic change.

Unfortunately, conclusions regarding the potential influence of alliance on subsequent IBS outcome are difficult to make because of methodological limitations of prior studies. The notion that therapeutic change depends on relational factors comes largely from studies correlating outcome indices (e.g., symptom change) with therapeutic relationship ratings assessed at a single point midway through treatment. The assessment of alliance typically occurs after substantial amount of improvement has already occurred among a sizable proportion of therapy patients (D. D. Burns & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1992). As such, any observed covariation between symptom change and alliance may not necessarily reflect its true mediational value. It is conceivable that patients who describe themselves as improved post-treatment become favorably disposed toward their therapists such that they are perceived as warmer, more empathic, and caring. Similarly, therapists may relate more positively to treatment-responsive patients who in turn rate their therapists more favorably (Loeb et al., 2005). In both scenarios, perceptions of the alliance are a consequence, not cause, of symptom change. To control for temporal confound, the present study used a design with multiple assessments during acute phase of both putative mediators and symptom relief. This improves on design of prior mechanistic IBS studies that have assessed hypothesized mediators only at pre- and post-treatment follow up(s) (e.g., Chilcot & Moss-Morris, 2013; Hunt et al., 2009; Lackner et al., 2007; Windgassen et al., 2019) or at midtreatment point (M. Jones et al., 2011) after a change in symptoms has occurred in a sizable proportion of CBT-treated patients (Lackner et al., 2010), violating a principle of temporal precedence that change in putative mediator must occur before change in outcome.

Treatment Expectations.

A fifth mechanism are the beliefs patients have about how likely they are to benefit from treatment. Positive treatment expectations have been a longstanding cognitive process deemed critical to effective psychotherapy particularly during its early stages (Frank & Frank, 1993). Patients entering treatment who are more optimistic about a positive outcome may be more likely to comply with the demands of a learning-based treatment like CBT and more likely to invest time and effort to achieve its goals (Bandura, 1986) than those with negative outcome expectancies. Treatment expectations (either positive or negative) have prognostic value across different disorders and treatments of varying orientation (Arnkoff, Glass, & Shapiro, 2002; Dozois & Westra, 2005; Greenberg, Constantino, & Bruce, 2006). Whether this pattern of results apply to CBT for IBS (or other chronic pain disorder) is unknown. Of two behavioral treatments (Everitt et al., 2019) identified as having particularly robust efficacy profiles (Black et al., 2020), only one (Lackner et al., 2018) controlled for treatment expectancy, suggesting that observed effect of CBT may not necessarily be due to its technical procedures per se to some extent by non-specific processes such as treatment expectancy and/or quality of therapeutic alliance.

Rapid Response to Treatment

In many CBT treatment contexts, a sizable proportion of patients show a rapid response to treatment based on the early phase of treatment (Wilson, 1999). In a wait list controlled study of CBT for IBS, Lackner et al (2010) found that rapid response characterized 30% of CBT treated IBS patients. Rapid responders were significantly more likely than non-rapid responders to meet criteria for a treatment responder at post-treatment and to maintain this response at 3 month follow up. Clinic-based CBT had comparable (30%) rapid response rate as MC-CBT suggesting that rapidity of response is not wholly dependent on the frequency of sessions or what occurs in session. Because the comparison group was a wait list control it is not clear whether rapidity of response is unique to CBT. This would require the addition of an active comparator arm that controls for nonspecific effects. Ilardi and Craighead (1994) argue that because rapid response occurs before introduction of cognitive change work it is a function of nonspecific processes not technical procedures specific to CBT. Wilson (1999) and Lackner et al (2010) countered that the demands of homework assignments particularly self-monitoring introduced before cognitive change work is formally initiated is sufficient to induce a perceptual shift that accelerates treatment response and may explain why rapid response typifies CBT. In contrast, other psychotherapies (Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinsky, 1986) do not emphasize real time self-monitoring that generates a functional analysis of symptom maintaining factors and have a symptom trajectory following a more gradual dose-response pattern. Self-monitoring may promote self-efficacy (SE) by fostering a sense of control over symptoms that are regarded as uncontrollable and unpredictable (Fennell & Teasdale, 1987). To the extent that self-monitoring is a distinctive aspect of CBT (Wilson, 1999), then we would expect that CBT would accelerate treatment response and influence treatment response through the acute phase and at post treatment. The present research tests this possibility. How treatment alliance impacts the onset of action of CBT and trajectory through post treatment is unknown. For example, it is not known what aspect of the alliance – the emotional bond that develops between patient and therapist, their agreement on goals, and/or the tasks deployed to achieve these goals – drives symptom relief and underlying change mechanisms (e.g. SE, fear of GI symptoms, pain catastrophizing, etc.) The notion that that the emotional bond between provider and patient is such a critical dimension of therapeutic alliance (Charon, 2001; Drossman & Ruddy, 2020) is so widely accepted that it has largely eluded empirical study. It is possible that the emotional bond is a consequence of positive treatment outcome (Webb et al., 2011) and more superfluous in producing therapeutic change than dimensions such as whether patient and provider agree on the tasks or goals of treatment.

The Present Study

The purpose of this prospective study was to characterize how common and treatment-specific factors are associated with treatment response in patients who undergo one of two dosages of CBT as compared with a treatment featuring IBS education. Based on prior research, we predict that two common factors – treatment expectations and quality of alliance established early in treatment – will “set the stage” for positive treatment response that CBT would leverage through cognitive change strategies that foster IBS self-efficacy underlying symptom relief. We expect that a well-defined constellation of common and specific factors will help explain the therapeutic advantage of CBT over a non-specific comparator whose emphasis on support and the provision of information constitutes a relatively weak way of changing SE from a social learning perspective (Bandura, 1977).

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 436 adults (18–70 years) who presented with GI symptoms that were at least moderately severe (i.e., occurred at least twice weekly and caused some life interference), consistent with Rome III diagnostic criteria (Drossman, Corazziari, Talley, Thompson, & Whitehead, 2006), and unaccompanied by organic gastrointestinal disease (e.g., IBD, colon cancer, etc.) as determined by a board-certified gastroenterologist. Patients were excluded if they presented evidence of current structural/biochemical abnormalities or other primary GI disease that better explained gastrointestinal symptoms; had been diagnosed for a malignancy other than localized basal or squamous cell carcinomas of the skin in the past 5 years; were undergoing IBS-targeted psychotherapy; could not commit to completing all scheduled follow up visits; had an unstable extraintestinal condition or a major psychiatric disorder (e.g., depression with severe suicidality, psychotic disorder); reported a current gastrointestinal infection or an infection within 2 weeks before evaluation; used a gut-sensitive antibiotic during the 12 weeks prior to baseline assessment. Institutional review board approval and written (UB, May 19, 2009; NU, December 19, 2008), signed consent were obtained before the study began. This study was completed in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Additional details of the IBSOS are provided in the primary outcome report (Lackner et al., 2018).

Treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy.

Cognitive behavioral therapy was delivered in two dosages: a) 10 weekly, 60-minute sessions of standard, clinic based CBT (S-CBT) or a 4 session primarily home-based version with minimal therapist contact (MC-CBT) in which patients received home-study materials (Lackner & Holroyd, 2010) covering the same procedures as S-CBT: information regarding brain-gut interactions; real-time self-monitoring that provides a functional analysis of the cognitive and behavioral processes maintaining the patient’s IBS symptoms; muscle relaxation to dampen physiological arousal; worry control that targets two transdiagnostic perceptual biases (A. G. Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafron, 2004) underlining cognitive rigidity: (1) an expectancy bias (i.e. “What if…?) that overestimates the risk of negative events based on unclear or ambiguous stimuli and (2) an interpretative bias that amplifies their perceived cost and consequences when they occur (i.e. “If only…”); flexible problem solving (Radziwon & Lackner, 2015) that teaches “appraisal-fit[ness]” skills that teach ways to deploy situationally appropriate coping strategies (emotion vs problem focused responses based on more accurate reading of contextual demands such as stressor controllability. As with other low intensity CBT programs (Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Loeb, Wilson, Gilbert, & Labouvie, 2000) that emphasize patient implementation over therapist oversight, the MC-CBT therapist functions more as a “facilitator” (Fairburn, 1995) providing rationale for treatment, corrective feedback, encouragement and structure to treatment, clarifying content, monitoring progress, and troubleshooting around homework difficulties during two 5–10 minute telephone calls. Because CBT is a learning based treatment that emphasizes extra-session practice of behavioral assignments (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Kazantzis, Whittington, & Dattilio, 2010) to maintain and enhance progress toward treatment goals, homework compliance during the previous week was rated by the treating clinician during each treatment encounter using a 6-item scale ranging from 0 =0% [participant did not attempt the assigned homework], 1 = 1–25% of homework completed, 2 = 26–50%, 3 = 51–75%, 4 = 76–100% of homework completed, 5 = completed more of the assigned than was requested) using a procedure featured in prior research (Taylor et al., 2001). As we have reported elsewhere (Lackner et al., 2018), homework compliance rates were 68% and 57% for MC-CBT and S-CBT, respectively.

IBS Education/Support.

A non-directive education/support condition (EDU; Lackner et al., 2012)) was implemented in accord with best practices (Balderson et al., 2016) (i.e. structurally equivalent to MC-CBT in time, attention, etc). This departs from prior IBS trials that have purposely engineered education-oriented comparators (Craske et al., 2011; Drossman, Toner, & Whitehead, 2003; Toner et al., 1998) to be as inert as possible by proscribing the provision of support, reassurance and other non-specific psychotherapeutic processes (Toner, 2001). Beyond evidencing diminishing therapy credibility beliefs as EDU-treated patients progressed through treatment (Drossman, Toner, Whitehead, et al., 2003), this approach imbalances the necessary structural equivalence of the two low intensity conditions on key non-specific dimensions, potentially exaggerating the technical effects of CBT better attributable to generic effects of simply receiving treatment of any modality or orientation (i.e. receiving support, reassurance). Because the IBSOS sought to characterize the long-term durability of treatment effects, an intentionally inert comparator raised an ethical issue of retaining subjects with a chronic pain disorder long term through 12 months post treatment in a condition known to be clinically inferior to CBT at enrollment. For these reasons, we designed a non-specific comparator that optimized the therapeutic value of education and support. EDU participants were provided the rationale that obtaining accurate, science-based information about IBS, its clinical features, epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, role of medical tests, and treatment options was therapeutic particularly in conjunction with an opportunity to share their personal experiences of having a refractory digestive disorder in a safe, non-stigmatizing environment where they could reflect about the meaning and impact of their illness experience to a knowledgeable, caring health care provider. Therapists exercised an empathic, nonjudgmental stance and other therapeutic elements of the psychotherapeutic relationship (e.g., active listening, reassuring style, etc; collaborative goal setting; agreeing on tasks and methods for how to achieve goals) while avoiding the technical elements specific to CBT (e.g. prescribing behavioral changes through skills building such as cognitive challenges or formal problem solving around stressors). Like MC-CBT, EDU was delivered over 10 weeks in 4 sessions with 2 10-minute phone calls the goal of which was to provide support and clarify understanding of patient education material. To control for receipt of the workbook assigned in MC-CBT, patients received a copy of IBS: Learn to Take Charge Of It of It (Gordon, 2004), a patient education book that reinforced the therapeutic value of information (“It all comes down to this: An informed patient is an empowered one”). Technical differentiation of EDU vs CBT protocols was enhanced with a custom book printing that extracted pages that covered proscribed behavioral techniques (e.g. step by step relaxation exercise) featured in the CBT conditions. In addition to weekly readings, EDU participants tracked symptoms (but not accompanying thoughts and emotions as in self-monitoring of CBT), food intake (e.g. meals, fiber content) physical activity, and completed at the end of Session 1 a stress profile (Nowack, 1999) that generated a personalized interpretative report of the patient’s stress, health habits, social resources, personality and coping style relative to a standardization sample without behavior change recommendations overlapping with CBT (e.g., relaxation, challenging thoughts, problem solving, etc). Compliance with previous week’s home assignments was monitored at each encounter with the same scheme used for therapeutic homework of CBT (see above). Therapists encouraged patients to complete home exercises but refrained from emphasizing the message delivered in CBT that they facilitated acquisition of symptom self-management skills through practice, consolidation, and generalization of what was learned in session to their natural environment. Instead, home exercises were designed to reinforce information covered in session. Compliance to home assignments was 71%.

Measures

GI Symptom Improvement.

Because of the heterogeneity of IBS and its multisymptom (pain, stool irregularities) complexion, global measure of relief such as the CGI is deemed preferable to a single symptom measure (e.g., pain intensity). Global IBS symptom improvement was based on the IBS version (Lackner et al., 2008) of the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I (Guy, 1976.) per recommendations for both pain and IBS trials (Dworkin et al., 2008; Irvine et al., 2006): “Compared to how you felt prior to entering the study, how would you rate the IBS symptoms for which you sought treatment during the past week?” (1 = substantially worse, 2 = moderately worse 3, slightly worse, 4= no change, 5 = slightly improved, 6 = moderately improved, 7 = substantially improved). Patients who rated symptoms as “substantially” or “moderately” improved qualified as treatment responders. CGI-IBS was administered at weeks 5 and 12 (post treatment follow up).

Working Alliance.

The patient version of the short form (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006) of the Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) is a 12 item self-report measure of three conceptually distinct aspects of therapeutic alliance based on Bordin’s tripartite model (1983): agreement that patient and provider share therapy goals (e.g., “____ and I are working towards mutually agreed upon goals”), agreement on the tasks of therapy to meet goals (e.g., “I feel that the things I do in therapy will help to accomplish the changes that I want”), and their emotional bond (e.g., “___ and I respect each other”). Four items assess each subscale each of which are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from never to always. The WAI has good predictive validity (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006). The scheduled timing of the administration of the WAI and other process measures corresponded with weeks of overlap in client-therapist encounters (face to face or telephonic) across all conditions (weeks 1, 3, 5, 8) and was designed to establish temporal precedence (Kazdin, 2007) with symptom improvement. Because the principle of temporal precedence requires a change in the proposed mediator precede a change in outcome, data obtained at week1 was not included as there was no pretreatment interaction with therapist for deriving change score on the WAI. Similarly, any mechanistically relevant change in outcome occurring after a change in proposed mediator at week 10 would have occurred after treatment ended. For these reasons, analyses were based on data collected at weeks 3, 5, and 8 with exception of treatment expectancy that was, as is convention, administered once (week 1). Composite reliability (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011) was .87 for both the Goals and Tasks subscales and .85 for the Emotional Bond Subscale

Self-Efficacy – IBS.

The IBS-SE Scale (Lackner, Krasner, et al., 2004) consists of 25 items rated on a 7 point scale that ranges from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Items reflect patients’ confidence in their ability to control and manage IBS episodes (e.g., “I can keep even bad bowel symptoms from disrupting my day by changing the way I respond to them”). Scores with higher self-efficacy reflecting stronger confidence to self-manage IBS. Composite reliability in the current sample was .93.

Treatment Expectancies.

At the end of session 1 after treatment rationale was provided, patients’ expectancy of improvement was assessed using the six-item Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (Deviliya & Borkovec, 2000). For the present study, we used the expectancy item that asks patients to rate on a 0 to 100% scale (in 10 unit increments): “By the end of the treatment, how much improvement in IBS symptoms do you think will occur”. Beyond its high face validity, this expectancy item is the most commonly used index of treatment expectancy in psychotherapy research (Thompson-Hollands, Bentley, Gallagher, Boswell, & Barlow, 2014). The composite reliability was .89.

Fear of GI Symptoms.

The Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI, Labus et al., 2004) is a 15 item measure whose items are rated on a 6-point scale, reverse scored, yielding a range of scores from 0 (no GI-specific anxiety) to 75 (severe GI-specific anxiety) with higher scores signifying greater fear of GI symptoms. The scale had an average composite reliability of .87.

Pain Catastrophizing,

The 2-item version of the Pain Catastrophizing subscale of the abbreviated Coping Strategies Questionnaire (Jensen, Keefe, Lefebvre, Romano, & Turner, 2003) asks patients to rate the frequency with which they engage in thoughts reflecting catastrophizing. Respondents rate each item using a scale ranging from 0 (never do) to 7 (always do). Higher scores indicate higher levels of pain catastrophizing. The average composite reliability was .79

Analytic Plan

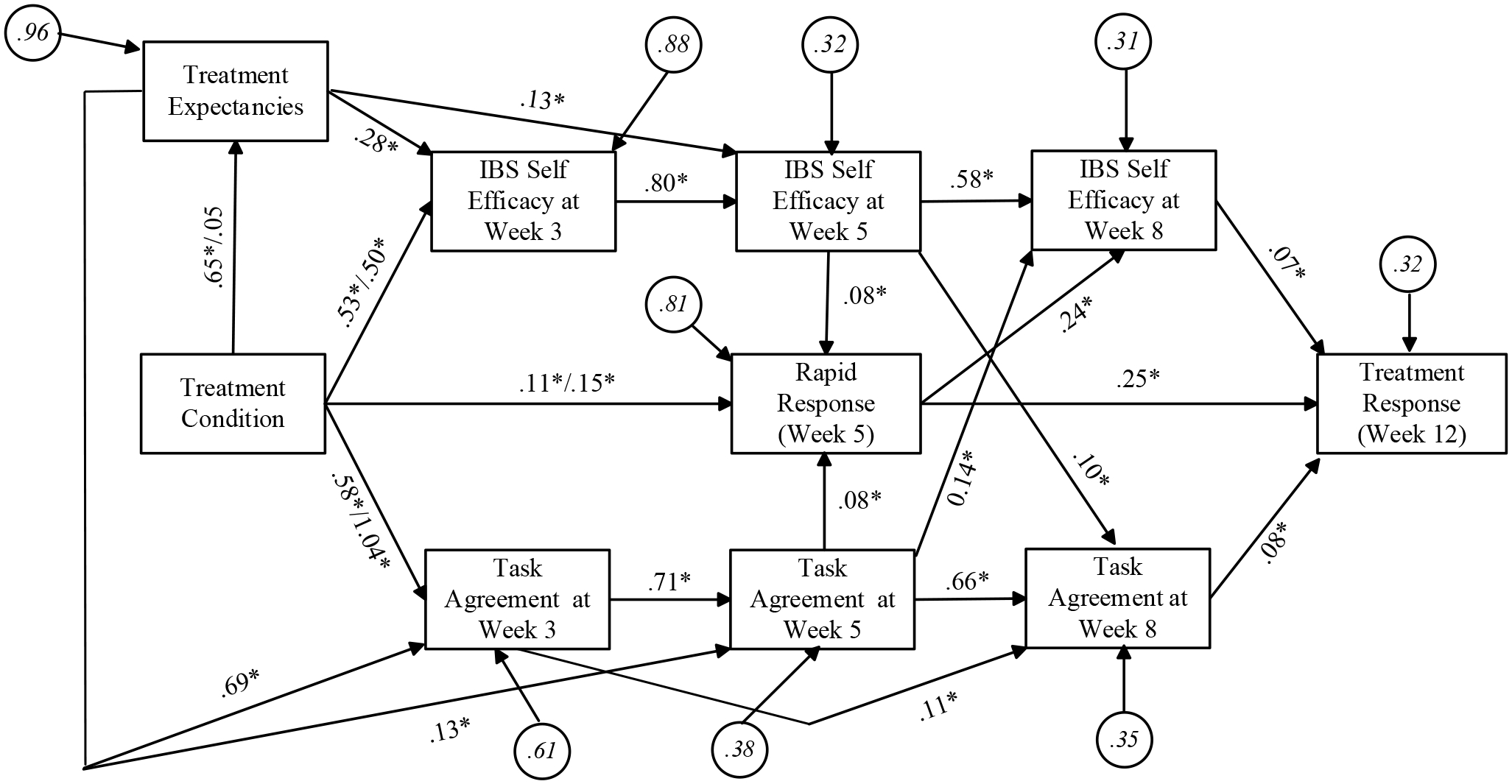

The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with Huber-White robust maximum likelihood (option MLR in Mplus 8.0). There were no latent variables. The dichotomously scored CGI measured at week 12 was the primary outcome. The tested structural model is in Figure 1. The model also included within-time correlated disturbances, although these covariances are omitted from Figure 1 to reduce clutter. The presence of multiple mediators, one of which is dichotomous (early treatment response at week 5) coupled with a dichotomous outcome (treatment response at week 12) complicates mediation analysis. One analytic strategy uses SEM with a latent propensity logistic framework as applied to binary outcome equations. We used instead modeling based on a modified linear probability model (MLPM), which has advantages over logit based approaches and also has considerable simulation data affirming its utility (Angrist & Pischke, 2008; Cheung, 2007; Deke, 2014; Hellevik, 2009; Horrace & Oaxaca, 2003; von Hippel, 2015, 2017). This is particularly true given our interest in estimating marginal probability effects rather than odds ratios or the coefficients associated with latent variables presumed to underlie dichotomous outcomes (see Mood, 2010; Norton, Dowd, & Maciejewski, 2018; Richard, Kristia, & Ander, 2018). Mediation tests relied on the joint significance test that evaluates if all the links in a mediational chain are statistically significant (Yzerbyt, Muller, Batailler, & Judd, 2018). Given a focus on mediation and mechanisms, per protocol analyses were used. Intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses are inappropriate because they focus on late-stage clinical trials that address effectiveness rather than efficacy. ITT analyses confound mechanisms that underlie both adherence and efficacy. Our focus was exclusively on mechanisms underlying efficacy (see Dallal, 2012; Feinman, 2009; Gross & Fogg, 2004). For elaboration, see the on-line supplement. Missing data were addressed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods per the default options in Mplus. For a discussion of our use of covariates, see the on-line supplement. Tests of the statistical significance of mediation relied on the joint significance test (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006; Yzerbyt et al., 2018)), which relies on statistically significant path coefficients for each link in a given mediational chain.

Figure 1.

Structural Model for Mediation of the Treatment Response

RESULTS

Screening of Potential Mediators.

We conducted preliminary analyses on the hypothesized mediators plus an additional candidate mediator, homework completion (home exercises were assigned in all three treatment conditions) to refine the mediational modeling in the primary analysis. Two necessary conditions must exist in order for a mediator to be plausible. First, it must be affected by the treatment condition, i.e., there must be mean differences in the mediator as a function of treatment. Second, the mediator must be related to the treatment outcome. In addition to IBS self-efficacy and treatment expectancies, we evaluated the subscales of the working alliance measure (working alliance – goals; working alliance – tasks (task agreement); working alliance – bond) and homework completion. Of the full set of mediators we considered, only treatment expectancies, IBS-self-efficacy, and task agreement met the minimal criteria for being viable change mechanisms. We therefore only included these mediators in the model (see the on-line supplement for details).

All included mediators were measured on an arbitrary metric. To make the metrics more comparable and interpretable, each mediator was transformed to a common metric ranging from 0 to 10 using the POMP (percent of maximum possible score method; see (Cohen, Cohen, Aiken, & West, 1999; Widaman, Little, Preacher, & Sawalani, 2011). The transformation subtracted the lowest possible score from the raw score, dividing this result by the highest possible score, and then multiplying the result by 10. For the new metric for any scale, a score of 0 meant the patient had the lowest possible score on the original scale and a score of 10 meant the patient had the highest possible score on the original scale. A score of 5 meant the patient scored at the mid-point of the original scale. A score of 2.0 meant the patient scored a value on the original scale that was 20% of the highest possible score, a score of 4.0 meant the patient scored a value on the original scale that was 40% of the highest possible score, a score of 8.0 meant the patient scored a value on the original scale that was 80% of the highest possible score, and so on.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on all key variables. The percentages for treatment response at the posttest were the same as those reported in our prior published primary outcome study (Lackner et al., 2018). Rapid response rates, which have not been previously reported, were 43% in MC-CBT, 45% in S-CBT and 22% in EDU conditions.

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Condition

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 436) | MC-CBT (n = 145) | S-CBT (n = 146) | EDU (n = 145) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.4 (14.8) | 40.9 (14.6) | 41.1 (14.4) | 42.2 (15.4) |

| Women, n (%) | 350 (80.3%) | 124 (85.5%) | 112 (76.7%) | 114 (79.2%) |

| Race/ethnicity n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 390 (89.4%) | 133 (91.7%) | 128 (87.7%) | 129 (89.0%) |

| African American | 28 (6.4%) | 8 (5.5%) | 9 (6.2%) | 11 (7.6%) |

| Other or missing | 18 (4.2%) | 4 (2.8%) | 9 (6.2%) | 5 (3.5%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Never married | 185 (42.4%) | 61 (44.1%) | 60 (41.1%) | 64 (44.1%) |

| Married | 185 (42.4%) | 68 (46.9%) | 58 (39.7%) | 59 (40.7%) |

| Separated/Divorced | 57 (13.1%) | 11 (7.6%) | 26 (17.8%) | 20 (13.8%) |

| Widowed | 9 (2.1%) | 5 (3.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Income, $, mean (SD) | 74.0 (54.2) | 77.9 (56.4) | 73.1 (52.2) | 71.3 (54.0) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| High school or less | 99 (22.7%) | 31 (21.4%) | 30 (20.5%) | 38 (26.2%) |

| Associate or vocational technical | 65 (14.9%) | 25 (17.2%) | 22 (15.1%) | 18 (12.4%) |

| College degree | 142 (32.6%) | 54 (37.2%) | 41 (28.1%) | 47 (33.1%) |

| Postgraduate degree | 127 (29.1%) | 35 (24.1%) | 52 (35.6%) | 40 (27.6%) |

| Missing | 3 (0.7%) | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Employed full- or part-time | 277 (63.5%) | 92 (63.4%) | 91 (62.3%) | 94 (64.8%) |

| Unemployed | 109 (25.0%) | 38 (26.2%) | 40 (27.4%) | 31 (21.4%) |

| Homemaker | 13 (3.0%) | 4 (2.8%) | 5 (3.4%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| Retired | 33 (7.6%) | 9 (6.2%) | 9 (6.2%) | 15 (10.3%) |

| Missing | 4 (0.9%) | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Predominant bowel type, n (%) | ||||

| Constipation | 130 (29.8%) | 43 (29.7%) | 40 (27.4%) | 47 (32.4%) |

| Diarrhea | 188 (43.1%) | 59 (40.7%) | 67 (45.9%) | 62 (42.8%) |

| Mixed | 98 (22.5%) | 33 (22.8%) | 35 (24.0%) | 30 (20.7%) |

| Undifferentiated | 20 (4.6%) | 10 (6.9%) | 4 (2.7%) | 6 (4.1%) |

| Years with IBS, mean (SD) | 17.1 (14.4) | 15.7 (13.3) | 17.7 (13.3) | 17.7 (16.4) |

| Received medical care for IBS (lifetime), n (%) | 328 (75.2%) | 107 (73.8%) | 116 (79.5%) | 105 (72.4%) |

| IBS treatment-naive, n (%) | 10 (2.2%) | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (1.9%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| Assessment scores, mean (SD) | ||||

| IBS Symptom Severity Scalea | 281.9 (72.1) | 278.0 (68.6) | 285.1 (76.7) | 282.4 (71.0) |

| Brief Symptom Inventorya | ||||

| Anxiety | 4.50 (4.50) | 4.22 (4.26) | 4.27 (4.41) | 5.02 (4.81) |

| Depression | 3.97 (4.29) | 4.07 (4.47) | 3.82 (4.33) | 4.03 (4.09) |

| Somatization | 4.22 (3.93) | 4.16 (4.31) | 4.00 (3.56) | 4.54 (3.91) |

| Global Severity Index | 12.7 (11.0) | 12.4 (11.6) | 12.1 (10.5) | 13.6 (10.8) |

| Medical comorbidities, # | 4.6 (4.9) | 4.8 (5.2) | 4.3 (4.7) | 4.8 (5.0) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities, # | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.7) |

| Medication use for IBS symptoms, n (%) | 292 (67.0%) | 94 (64.8%) | 95 (65.1%) | 103 (71.0%) |

| Pain medication | 35 (8.0%) | 9 (6.2%) | 13 (8.9%) | 13 (9.0%) |

| Bowel medication | 271 (62.2%) | 86 (59.3%) | 87 (59.6%) | 98 (67.6%) |

| Multi-symptom medication | 20 (4.6%) | 6 (4.1%) | 7 (4.8%) | 7 (4.8%) |

| Psychiatric medication | 26 (6.0%) | 8 (5.5%) | 12 (8.2%) | 6 (4.1%) |

Note.

= number of comorbidities

Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms; IBS-SSS ≥ 300 = severe.

SEM Analyses

Figure 1 presents the results of the tested SEM analyses. The overall fit of the model was satisfactory based on the collective pattern of multiple fit indices (chi square = 38.42, df = 19, p < 0.05; RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI = 0.03 to 0.07) with a p value for close fit = 0.51; CFI = 0.99, standardized root mean square residual = 0.03). Inspection of the modification indices revealed no theoretically meaningful, sizeable indices. No statistically significant normalized residuals were observed when comparing predicted versus observed covariances on a cell-by-cell basis. The conclusions discussed below did not change as a function of different modeling strategies in sensitivity analyses (e.g., using logit instead of MLPM functions). We now highlight seven sets of path coefficients that are of substantive interest and supplement them with results from total effects analyses for the model and effect decomposition.

1. Rapid treatment response at week 5 was predictive of IBS symptom improvement at week 12 (post treatment).

Overall and collapsing across all treatment conditions, 36% of the sample were early responders to treatment by week 5. Of these early responders, 86% of them were treatment responders at the 12-week post-treatment assessment. Thus, rapidity of treatment response was predictive of the final treatment response. Of the non-responders at week 5, 44.5% eventually qualified as responders at the 12-week post-treatment assessment -- that is, they needed the full treatment regimen to achieve a positive treatment response. For those patients who do not show an early response, nearly half of them will go on to show positive treatment response at post treatment.

2. CBT–treated patients were more likely to be rapid responders than patients in the EDU condition.

Based on the total effect analyses, we found that in the EDU condition, 22% of the patients were rapid responders by week 5. By contrast, the percent of rapid responders in the MC-CBT and S-CBT groups was 43 and 45%, respectively. These differences between each CBT group and the EDU group were statistically significant, (z = 3.57, p < 0.05 for MC-CBT and z = 3.63, p < 0.05). As seen in Figure 1, rapid response differences reflect both the direct effects of the treatment condition on early response as well as effects through the mediators of positive treatment expectancy, IBS self-efficacy, and task agreement dimension of the alliance.

3. Treatment expectancies, IBS self-efficacy and client-therapist agreement on the tasks of therapy to achieve goals (task agreement) are each more positive in the MC-CBT conditions than in the EDU condition.

Based on total effects analyses, the mean values for the three mediators were more positive in the MC-CBT condition than the EDU condition at all time points. This pattern also applied to the S-CBT condition versus EDU, with the exception of task agreement at weeks 5 and 8 and for treatment expectancies. Table 2 presents the relevant estimated mean differences, significance tests, confidence intervals, and Cohen’s d.

Table 2.

Mean Difference between CBT Conditions and EDU on Mediators

| MC-CBT - EDU | S-CBT - EDU | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment expectancies | 0.65* ±0.32 (0.56) | 0.05 ±0.34 (0.11) |

| IBS Self-efficacy at week 3 | 0.71*±0.34 (0.60) | 0.51*±0.34 (0.43) |

| IBS Self-efficacy at week 5 | 0.65*±0.28 (0.64) | 0.41*±0.29 (0.40) |

| IBS Self-efficacy at week 8 | 0.66*±0.27 (0.68) | 0.42*±0.26 (0.44) |

| Alliance- Task Agreement at week 3 | 1.03*±0.41 (0.71) | 1.07*±0.42 (0.76) |

| Alliance – Task Agreement at week 5 | 0.76*±0.37 (0.63) | 0.25±0.41 (0.17) |

| Alliance - Task Agreement at week 8 | 0.67*±0.30 (0.71) | 0.32±0.33 (0.27) |

(Notes: * p < 0.05; Entries after the ± are margins of error operationalized as half widths of the 95% confidence interval; Cohen’s d are in parentheses)

4. Treatment expectancies, IBS self-efficacy and agreement that the tasks of therapy are useful for achieving its goals (task agreement) each are consistent with mediation of some of the effect of CBT treatment versus EDU on both early treatment response as well as treatment response at week 12.

The modeled mediational dynamics were complex, but all three of the identified mediators were linked to both rapid response as well as to treatment response at week 12. This is apparent from the pattern of statistically significant paths in the various mediational chains via the logic of the traditional joint significance test of mediation. As noted above, MC-CBT had 20% more rapid responders than EDU even though they were structurally equivalent (e.g., four 1-hour sessions). Effect decomposition analyses found that 9% of these were due to the elevated status on the three mediators combined (z = 4.25, p < 0.05) whereas the remaining 11% were due to other unmeasured mediators not identified in our study as reflected by the direct effect of the treatment condition on early response (z = 1.97, p < 0.05). For the S-CBT condition, the three mediators combined were associated with a 5% increase in rapid responders relative to EDU (z = 2.32, p < 0.05), with the remaining 15% being due to other unmeasured mediators as captured by the direct effect (z = 2.88, p < 0.05).

For the effect of MC-CBT on the final treatment response (week 12), MC-CBT had 16% more treatment responders than EDU. Effect decomposition analyses found that 14% of these were due to the elevated status on the three mediators combined (z = 4.95, p < 0.05). The results for the S-CBT condition showed that S-CBT had 13% more treatment responders than EDU, of which 9% were due to the elevated status on the three mediators combined (z = 4.21, p < 0.05). The intensity of treatment (low vs high) did not significantly influence how much the three mediators impacted treatment response

5. There is evidence that stronger treatment expectancies for improvement just after treatment commences but before treatment procedure are fully implemented, collapsing across conditions, are associated with ensuing higher levels of IBS self-efficacy and higher levels of task agreement at weeks 3, 5 and 8 of treatment.

A total effects analysis found that the path coefficient from treatment expectancies just after treatment rationale is provided to IBS self-efficacy at week 3 was 0.28 (z = 5.10, p < 0.05), at week 5 it was 0.35 (z = 6.34, p < 0.05), and at week 8 it was 0.36 (z = 7.55, p < 0.05). The path coefficient from treatment expectancies to task agreement at week 3 was 0.69 (z = 13.20, p < 0.05), at week 5 it was 0.62 (z = 11.25, p < 0.05), and at week 8 it was 0.50 (z = 10.01, p < 0.05).

6. There is evidence consistent with reciprocal causation between ratings of self-efficacy and agreement between patient and therapist that the tasks of therapy are useful for achieving its goals (task agreement): Self-efficacy at week 5 is related to task agreement at week 8 and task agreement at week 5 is related to self-efficacy at week 8.

A strength of longitudinal SEM is its ability to provide perspectives on possible reciprocal causality. We found evidence for such a causal dynamic. Specifically, the path coefficient linking ratings of self-efficacy at week 5 to task agreement at week 8 was 0.14 (z = 3.66, p < 0.05) and the path coefficient linking task agreement at week 5 to ratings of self-efficacy at week 8 was 0.10 (z = 3.37, p < 0.05). In other words, self-efficacy judgements (i.e. confidence in the ability to self-manage IBS symptoms) at week 5 impact the extent to which therapeutic alliance is deemed collaborative around mutually agreed upon tasks carried out in subsequent weeks for relieving GI symptoms

7. There is evidence consistent with reciprocal causation between rapid treatment response and IBS self-efficacy: Self-efficacy at week 5 is associated with treatment response at week 5 and rapid response at week 5 is associated with self-efficacy at week 8.

We also found evidence for potential reciprocal causality between rapid treatment response and IBS self-efficacy. The path coefficient linking feelings of self-efficacy at week 5 to rapid response at week 5 was 0.08 (z = 4.42, p < 0.05) and the path coefficient linking rapid response at week 5 to self-efficacy ratings at week 8 was 0.24 (z = 2.20, p < 0.05)

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate common vs CBT-specific factors in accounting for GI symptom improvement in IBS patients who were treated with CBT as compared with a nonspecific education support control. We focused primarily on three CBT-based mechanisms, self-efficacy to manage IBS symptoms, fear of GI symptoms and pain catastrophizing, and 2 common ones, alliance and treatment expectancy. We also included compliance with home exercises although this was not a primary a priori hypothesized mediator. Our main finding was that both CBT—specific and common, nonspecific factors account for GI symptom improvement to some extent. Their effects which are more fully delineated below are both synergetic and to some extent independent at various points of the acute phase. Based on a summary of the field by Burns et al (2020), this is arguably the first psychosocial pain study that has demonstrated mechanistic specificity between a credible nondirective comparator (EDU) and CBT and that takes into account technically identical CBT protocols of different dosages.

Neither pain catastrophizing nor fear of GI symptoms met the conditions for mediator viability. To be sure, there was some evidence that these variables relate to post treatment ratings of IBS symptom improvement (see the on-line supplement), but they could not account well for the differences between CBT and EDU observed in this study. In light of broader research that has not established treatment specificity (J. W. Burns et al., 2012; J. W. Burns, Van Dyke, Newman, Morais, & Thorn, 2020; Turner et al., 2016) for pain catastrophizing, future research needs to address the possibility that what consistently modulates pain experience across multiple disease states (J. W. Burns et al., 2012) may not necessarily make for a suitable change mechanism for behavioral pain treatments. It is also possible that pain catastrophizing is simply a non-specific index of overall level of cognitive-affective distress. This explanation may explain why pain catastrophizing changes prospectively with treatments that range from acceptance-based therapies (Craner, Lake, Bancroft, & George, 2020) to yoga (Hall, Kamper, Emsley, & Maher, 2016) even those that do not formally proscribe formal cognitive change work that are a defining feature of CBT. We think it is time that the field looks beyond pain catastrophizing for an adequate change mechanism for understanding why and how CBT relieves painful medical disorders like IBS. Beck’s Generic Cognitive Model (e.g., Beck & Haigh, 2014) would argue that pain catastrophizing does not induce symptom change because as a “surface level” cognition its content or “meaning and interpretation” (and by extension symptom impact) is driven by biased processing (e.g.,. such as the perseverative quality of thought) that conventional behavioral pain treatments do not systematically target. In fact, cognitive processes such as rumination are largely regarded as the focus of third-wave treatments (M. P. Jensen, Thorn, Carmody, Keefe, & Burns, 2018) that are concerned with “what we do with our cognitions (e.g., ignore them, select the most useful ones to focus on, accept them without judgment, etc” (Jensen, Thorn, Carmody, Keefe, & Burns, 2018). Our data suggests that CBT protocols, that systematically teach patients how they can alter biased processing style (i.e. cognitive process such as repetitive negative thought and its resultant perceptual biases) may have more therapeutic benefit (e.g. symptom relief) than classic CBT pain protocols that focus narrowly on changing the validity and content of pain cognitions like pain catastrophizing or third-wave treatments that emphasize the expression or experience of negative internal states (e.g., pain, anxiety) after their initiation and divorced from their meaning. In other words, a binary distinction between cognitive process and content, while intuitive from the perspective of conceptually distinct therapeutic orientations, may not reflect the complexity of how individuals perceive the world (including their symptoms), why empirically-validated treatments with symptom relieving properties work, and how they induce symptom change. As far as fear of GI symptoms, it may very well mediate avoidance behaviors (Hesser et al., 2018) but our data do not support it being a mediator of the effect of CBT on IBS symptom improvement. This result has broader clinical significance for both practitioners and patients of all IBS types not only the subset who are hypervigilant to visceral sensations (Delvaux, 2002).

Self-efficacy as a key CBT-specific mediator

By the same token, it is premature to dismiss self-efficacy as a change mechanism of the efficacy of CBT when it is formally evaluated and not inferred (Hesser et al., 2018) from a measure of personal competence. Our data are consistent with social learning theory hypothesis that CBT -- whether delivered in-person across 10 weekly sessions or via a home-based regimen -- strengthens patients’ confidence in their ability to self-manage IBS (i.e. IBS self-efficacy) which in turn improves GI symptoms. The effect of CBT on SE begins to manifest itself as early as week 3 and persists through immediate follow up, two weeks after treatment completed. The SE effect is not dependent on session frequency. It is possible that session 1 of MC-CBT provides greater experiential learning opportunities that social learning theory deems critical to strengthening self-efficacy and subsequent behavior change (Bandura, 1986).

Expectancy and alliance as key common, “non-specific” mediators

With respect to non-specific or common factors, results support the importance of treatment expectancy and therapeutic alliance as change mechanisms. Consistent with prior research (Constantino, Arnkoff, Glass, Ametrano, & Smith, 2011), patients who reported positive treatment expectancy at the end of the first session were more likely to report early symptom improvement early on (week 5) and at week 12 two weeks after treatment ended. A similar pattern of results held for therapists-patient task agreement dimension of therapeutic alliance from the patient’s perspective. Patients who more strongly agreed with therapists on how to achieve treatment goals (task agreement) reported symptom improvement at week 5 and tended to maintain these gains post treatment. The combination of high IBS self-efficacy, a positive treatment expectancy, and task agreement appears to have a catalytic effect on GI symptom improvement with CBT tending to better leverage these dynamics than EDU. The advantage that CBT has over EDU in GI symptom relief corresponds with elevated levels of three mediators at weeks 3 and 5 of the 10 week-acute phase (as well as 2 week post treatment follow up (week12).

Treatment expectancy seems to be associated with therapeutic effects in at least two ways. Cognitively, it is associated with IBS self-efficacy both directly (weeks 3 and 5) and indirectly (week 8) which, in turn, is associated with improved GI symptoms. Beyond this cognitive pathway, treatment expectancy was also associated with improved GI symptoms via an interpersonal route that runs through the shared understanding between patient and clinician that the tasks of therapy are suitable for achieving treatment goals (i.e. symptom relief). Patients who believe that treatment will improve symptoms are more likely to agree that its tasks will relieve their GI symptoms. It is notable that the interpersonal route that expectancy takes is not dependent on session frequency highlighting the importance of agreed upon tasks that build on a clear, compelling rationale delivered in session 1 and reinforced thereafter either verbally and/or through self-study materials. These data suggest that non-specific therapeutic processes can be effectively exported to some extent beyond clinic setting without diluting their impact, a finding that is relevant to the development of less resource intensive digital therapeutics whose real-world value has been compromised by persistence, dropout and adherence issues (Andersson, Titov, Dear, Rozental, & Carlbring, 2019).

Reciprocal relationship between CBT-specific and common mediators

Interestingly, we also found support for a reciprocal causal relationship between patient – therapist task agreement and self-efficacy such that as patients grow more confident in their ability to self-manage IBS symptoms (week 5), their conviction that treatment tasks will meet their goals increases (task agreement) and culminates in improved GI symptoms. At the same time, stronger task agreement at week 5 is associated with stronger self-efficacy at week 8, which in turn is associated with improved GI symptoms at post treatment. These data exemplify the likely complex dynamics of CBT-specific and non-specific processes underlying symptom relief during psychotherapy which, to our knowledge, have not been as systematically detailed in the psychotherapy process literature.

Task agreement as key dimension of therapeutic alliance

The finding that collaborative agreement on the usefulness of tasks of therapy for achieving its goals (task agreement) accounts for some of the effect of CBT on outcome echoes research of Webb et al (2011) who found that variation in symptom change in cognitive therapy-treated depressed patients was more strongly associated with therapist-patient agreement on tasks. In Webb et al. (2011), the relational bond between patient and therapist did not emerge as an independent predictor which Webb et al interpreted as evidence that the emotional bond “may be more of a consequence, than a cause, of symptom change” (2011). In other words, a well-structured, empirically derived treatment that lays out a strong treatment rationale and mutually agreed upon procedures for how to achieve goals is likely to provide therapeutic benefit from which a strong emotional bond between patient and therapist emerges. Although we found that relational bonding was associated with symptom improvement (see the on-line supplement), it was evident that it, like goal agreement, took a secondary role to task agreement among the alliance variables. The centrality of task agreement echoes prior alliance-outcome research with our clinical disorders (Buchholz & Abramowitz, 2020; Hoffart, Øktedalen, Langkaas, & Wampold, 2013). Hoffart et al attributed this pattern of results to the more structured nature of behavioral treatments like CBT. If so, we would expect that client-therapist goal agreement would also emerge as a working mediator for CBT based on its strong collaborative stance around clearly defined goals which is accentuated in a clinical trial where treatment is manualized, goal-focused and time-limited. This is not what we found, suggesting that client-therapist agreement about tasks has an empowering (i.e. self-efficacy enhancing) impact on symptom improvement that is more therapeutic than shared decision making around goals to which they are directed.

Low intensity CBT promotes rapid response

Our data replicate our previous finding (Lackner et al., 2010) of rapid response in CBT-treated IBS patients enrolled in a wait-list controlled study. That we replicated these findings in a RCT using a nondirective comparator argue against the notion that rapid response is merely a non-specific psychotherapeutic phenomenon that comes with the provision of help and hope in the context of a warm, trusting, supportive and caring relationship (Forand & Derubeis, 2013). If this were the case, we would have expected higher rapid response rate in the S-CBT or EDU condition by virtue of their greater session intensity (10 session S-CBT) or supportive focus (EDU), respectively. This was not the case: low intensity CBT condition had comparable rapid response rate as S-CBT (43 vs 45%) and a significantly higher rapid response rate than EDU (22%). We believe that the structure, focus, strict time limits, collaborative stance, and emphasis on a limited number of sequential skills that intuitively build on each other and are practiced in natural setting where symptoms occur has an empowering impact that catalyzes symptom changes. This is consistent with the principles of self-directed learning (e.g. we learn best in natural environment where theoretical knowledge is more readily transferred to practical contexts; (Merriam & Baumgartner, 2020). Data raise the intriguing question of whether the structure and format of low intensity behavioral treatments represent working mechanisms for outcomes independent of CBT-specific and nonspecific processes that have been a historical focus of mediation research. If so, the built-in efficiencies (fewer clinic visits, home study) of low intensity may not only have practical advantages (i.e. cost, convenience, patient satisfaction, accessibility). Their practicality may confer therapeutic advantages that facilitate learning of symptom self-management much like self-regulated learning programs promote learning of foreign languages, mathematics, and other cognitive skills whose proficiency is to some extent maximized by leveraging contextual factors (eg environment where knowledge is learned and applied) (Zimmerman, 2000). As a cognitively-oriented therapy, MC-CBT may engage critical self-regulated learning processes that increase one’s ability to self-manage painful physical symptoms. This is an important and underexplored area for further psychotherapy process research particularly during COVID-19 era that place a premium on results-oriented home-based treatments.

Practice Implications

Clinically, our data have important implications for practitioners of behavioral pain treatments for disorders like IBS. At the broadest level, treatment gains involve changing information processing style manifested in a tendency to overestimate the probability of negative events (threat expectancy (Elsenbruch, 2014)), interpretative bias that reflects a tendency to inflate the costs or consequences of adverse events (Park et al., 2018), and a rigid coping style preferentially geared toward solving problems regardless of their objective controllability (Cheng, Hui, & Lam, 2000; Radziwon & Lackner, 2015). Which specific perceptual bias underlies symptom fluctuations is beyond the scope of this paper as is the relative therapeutic value of specific cognitive techniques featured in the MC-CBT protocol. The pattern of data suggest that gaining sufficient confidence to self-manage painful IBS symptoms (i.e. self-efficacy) comes about by first changing the way patients think (cognitive process) not simply the content of pain-specific thoughts (e.g., pain catastrophizing) as traditional CBT models have traditionally conceptualized matters (Jensen et al., 2018). In our protocol, this is done through worry control strategies that target discrete cognitive biases (interpretive, expectancy biases) arising from repetitive negative thought and flexible problem solving training that tackle a rigid, nondiscriminative coping style oriented toward problem-focused, control-oriented responses regardless of situational demands (e.g., stressor controllability). In light of the efficacy comparability of clinic-based S-CBT and home-based MC-CBT, the symptom-ameliorating elements of therapeutic alliance need not depend solely on face to face interactions (e.g., clinic, telephonic) but conveyed indirectly through engaging and user friendly home study materials that reinforce both the technical content of MC-CBT (e.g., flexible problem solving) and operative relational processes (e.g. agreed upon tasks).

Our study suggests that future research should consider in more depth the possible causal dynamics between bonding and client-therapist task agreement. Is there a critical amount of emotional bonding that draws patients out and brings them and their therapist to a consensus around tasks that comprise an empirically validated treatment regimen? Does too much emotional bonding (e.g., demonstrative empathy, reflective listening) interfere with consensus building around critical tasks of therapy (e.g. establishing a credible explanation for why IBS symptoms are self-perpetuating and what a patient can do to reverse the stress-painful GI symptom cycle)? Is a minimum level of emotional bonding required for task agreement to achieve beneficial effects? If emotional bond between patient and therapist support task agreement, it can as we show here be achieved relatively efficiently (≤4 1 hour sessions) without any decrement in efficacy relative to office-based CBT that requires 60% more therapist contact time. These are important questions for future research that specify precise technical and common factors that promote symptom relief, their interaction, and when -- and where -- they are optimally induced for maximum gain and minimal cost.

Given the observed reciprocal relationship between self-efficacy and task agreement, it is worth considering whether self-efficacy’s long-term impact is boosted by patient and clinician agreement on treatment tasks during the acute phase. If so, we would expect that task agreement struck during treatment may have long term prognostic value in explaining CBT’s enduring effects after treatment completion. What stage of therapy clients and clinicians are most likely to agree on tasks has greatest prognostic value is an important area for further psychotherapy process research with useful clinical implications for practitioners of different orientations (behavioral, medical, dietary). In our clinical work, we find that having patients review a hard copy of their initial evaluation during the first session goes a long way in bringing therapists and patients to agreement around tasks that form the basis of CBT, strengthens positive expectancy for a positive outcome, supports self-efficacy, engages them in the learning process, reduces risk of dropout, and, by extension, preserves clinical resources for those who are most likely to benefit. Data support this clinical observation.

Limitations

The current study has limitations that we sought to mitigate in an effort to render robust findings with optimal interpretability. As is the case in many psychotherapy trials, our sample included individuals who volunteered for a behavioral treatment for a chronic medical problem. It is possible that study participants were more psychologically minded, motivated and open to a biobehavioral formulation of their condition than those who did not seek (or were not referred to) psychological treatment for their IBS. Self-selection is an issue for any treatment whether delivered in or out of an RCT. We mitigated selection bias by recruiting a broad sample of the “entire eligible patient population” (G. T. Jones, Jones, Beasley, & Macfarlane, 2017) from the community, primary care, and specialty (e.g., GI, OB/GYN) clinics to yield a less biased efficacy profile (even though tertiary care IBS patients are more distressed (Whitehead, Bosmajian, Zonderman, Costa, & Schuster, 1988) they are more responsive to psychosocial therapies than symptomatic community counterparts (Raine et al., 2002), making this study particularly rigorous relative to studies that recruit solely from a single specialty practice whose patients often differ from those in community on key clinical characteristics (Drossman et al., 2009). The relative homogeneity of our sample – white, female, relatively educated – may limit generalizability to a more diverse patient mix.

We relied on patient reported outcome (PRO) measures to gauge treatment effects and their mechanistic underpinnings. While the PRO featured in this study is recommended for both IBS and chronic pain trials (Dworkin et al., 2005; Irvine et al., 2006), its inherent subjectivity may introduce bias, although we have found a high level of correspondence between patient reported measures of symptom relief and blind physician ratings (Lackner et al., 2018; Lackner, Jaccard, Radziwon, et al., 2019). Whether this correspondence extends to perceptions of the therapeutic alliance from the clinicians’ perspective is unknown but of questionable clinical significance given the preference the alliance field attaches to patients’ experience (Webb et al., 2011). The study focused on a handful of variables drawn from social learning theory (self-efficacy) as well as the pain (e.g. catastrophizing), IBS (fear of GI symptoms), and psychotherapy literatures (i.e., alliance, treatment expectancy) regarding non-specific factors of highest impact potential and was not designed as an exhaustive analysis of all candidate mediators. One could argue that a two-item version of pain catastrophizing has psychometric limitations (e.g. construct validity) and that a different pattern of results would emerge had we used the parent version of the CSQ. We are not so sure. The two item version correlates highly (r = .91, Jensen et al., 2003) with the parent version (Rosenstiel & Keefe, 1983) and our results align with the findings of a growing number of other large studies that have failed to support pain catastrophizing as a mediator sensitive to change or with treatment specificity (J. W. Burns et al., 2020). As we wrote above, self-reported pain catastrophizing suffers from validity issues (content, construct) unrelated to instrument brevity. In fact, the two items of the brief CSQ catastrophizing scale the present study used are among the top five items reflecting pain catastrophizing across full length pain catastrophizing measures(Crombez et al., 2020), suggesting that in this case brevity optimizes validity.

The results of the study beg the question as to what mediates the durability of treatment response. This is an important question beyond the scope (or study design) of this paper which concerns the factors that account for the efficacy of CBT. That said, given that we saw little erosion in treatment response over 12 month follow up period (with MC-CBT’s effect not S-CBT’s increasing over time; (Lackner, Jaccard, Firth, et al., 2019), we suspect that mediational effect of CBT-specific variables like self-efficacy extend beyond the acute phase but this is an empirical question worthy of further study. Because IBSOS participants had no therapeutic interaction after treatment ended, we doubt relational variables mediate long-term outcome.

Analytically, portions of the SEM model are based on correlational rather than experimental data, making causal inferences for those parts of the model ambiguous. The prospective nature of the design helps address the matter but it does not do so definitively. Bias in coefficients can result from measurement error, left out variable error (Mauro, 1990), and sequential ignorability in mediation modeling (Imai, Keele, & Yamamoto, 2010; VanderWeele, 2015). These considerations also suggest caution when interpreting results (however, sensitivity analyses with a range of covariates did not alter conclusions). Finally, the possible presence of equivalent and alternative models that can equally account for the data also must be kept in mind (Bollen & Pearl, 2013; Hayduk, 2014). We approach SEM from the perspective that the posited causal model (Figure 1) is a priori reasonable, consistent with prior theory, and makes predictions about how the observed data should pattern themselves. Given the data did, in fact, reveal patterns consistent with the model increases our confidence in the model and its parameter estimates, but it does necessarily prove the model is correct.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the above limitations, our data suggest GI symptom improvement among refractory IBS patients depends on a small, well-defined, conceptually distinct, and actionable constellation of CBT-specific and common processes. These factors are stronger for CBT than a nondirective IBS education/support condition regardless of intensity but they (particularly nonspecific effects) are more fully operative in the low resource intensity version of CBT (MC-CBT) that required 60% therapist contact than standard CBT. Data both challenge the notion that treatment-induced effects are necessarily played out in a relational context and specify precise change mechanisms that may underlie the effects of treatments delivered across traditional (clinic-based) and low intensity modalities (e.g., mobile, web, telephonic, bibliotherapy), thereby expanding CBT’s scope and scalability.

Supplementary Material

Public health significance.

This study highlights the mechanistic value of targeting patients’ confidence in their ability to self-manage IBS (self-efficacy), treatment expectancy, and agreement of tasks used to achieve therapy goals of cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with moderate to severe IBS, the most common GI disorder seen by primary care and GI physicians. The study specifies common and CBT-specific processes that influence the magnitude and rapidity of treatment response for a prevalent chronic pain disorder refractory to conventional medical therapies.

Acknowledgement.

We thank our IBSOS colleagues at UB, Northwestern, NIH, Frontier Science (Data Coordinating Center) for their support of this research. These include Mark Byroads, Darren Brenner, MD, Ann Marie Carosella, PhD., Gregory D. Gudleski, PhD, Frank Hamilton, MD, MPH, Leonard A. Katz, MD, Laurie Keefer, PhD, Susan S. Krasner, PhD, Chang-Xing Ma, PhD,. Christopher Radziwon, PhD, Patricia Robuck, PhD, MPH, Michael D. Sitrin, MD, We are particularly grateful for the efforts of Rebecca Firth, MHA who provided administrative oversight of the IBSOS.

Grant Support: