Abstract

Background

considering the importance of social participation for quality of life and active ageing in older adults, it is an important target of social and health professionals’ interventions. A previous review of definitions of social participation in older adults included articles up to 2009; new publications and changes in the social context (e.g. social media and the COVID-19 pandemic) justify continuing this work.

Objective

this paper provides an updated inventory and synthesis of definitions of social participation in older adults. Based on a critical review by content experts and knowledge users, a consensual definition is proposed.

Methods

using a scoping study framework, four databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, AgeLine, PsycInfo) were searched with relevant keywords. Fifty-four new definitions were identified. Using content analysis, definitions were deconstructed as a function of who, how, what, where, with whom, when, and why dimensions.

Results

social participation definitions mostly focused on people’s involvement in activities providing interactions with others in society or the community. According to this new synthesis and input from content experts and knowledge users, social participation can be defined as a person’s involvement in activities providing interactions with others in community life and in important shared spaces, evolving according to available time and resources, and based on the societal context and what individuals want and is meaningful to them.

Conclusion

a single definition may facilitate the study of active ageing and the contribution of older adults to society, socioeconomic and personal development, benefits for older adults and society, self-actualisation and goal attainment.

Keywords: social engagement, social involvement, social activities, older adults, community participation

Key Points

Definitions of social participation should not reinforce social norms.

Involvement in meaningful interactions must be facilitated by health policies.

Future studies on definitions include older adults’ perspectives.

Introduction

Around the world, population ageing creates challenges for human and financial resources, individual health and quality of life, as well as equity and well-being in society [1]. Now more than ever, as the COVID-19 pandemic increases isolation and ageism [2], the importance of social interactions and participation is widely recognised (including in public policies) but this presents new challenges in terms of security and roles [3–5], At the beginning of the pandemic, one in three older Canadians (28.9%) reported concerns about maintaining social ties [6]. For most older Canadians (94.1%), opportunities for social interactions were and still are very limited. Based on a scoping review of the definitions of social participation in older adults, which included articles up to 2009, social participation could be defined as a person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community [7]. As a health determinant, enhanced social participation helps older adults to be active and, in response to concerns about population ageing [8] that inspired public policies (e.g. [9]), is a key proposal of the World Health Organisation (WHO). Following the UK Minister for Loneliness’ appointment, several countries in Europe considered officialising efforts to combat loneliness [10], against which social participation has a known protective effect [11]. Social participation is also associated with a reduced risk of mortality [12–14] and morbidity [15], greater functional independence [16], greater satisfaction with life [17], and shorter hospital stays [18].

When social participation is optimal [19], older adults might have a sense of purpose and contribution, and their engagement benefits society as well as themselves [20]. For example, volunteering encourages values such as altruism and also fosters the feeling of being valued and respected in one’s community, which in turn increases resilience in response to stress [21] and can lead to positive mental health outcomes, including less loneliness [22]. Social participation should be seen as encompassing involvement not only in non-profit and public organisations, including volunteering, but also in many other aspects such as social and leisure activities, and informal support between families and neighbours. By participating in society according to their needs, desires and capacities, older adults reduce their risk of social exclusion, which is a ‘process through which individuals become disengaged from mainstream society, depriving people of the rights, resources and services available to the majority’ [23:681], and increases as they grow older. Lack of access to material resources such as income and housing or to healthcare restricts social participation [24] and increases inequalities, which could be attributable to the combination of population ageing, ongoing economic instability and situations of vulnerability [25]. Many factors, such as being over 80 years of age, having a low income [26], belonging to a racial, ethnic or linguistic minority, presenting one or more disabilities, or identifying as belonging to a sexual or gender minority [27], can interact and increase the risk of marginalisation and social exclusion [25]. It is thus essential to promote older populations’ social participation using processes that enable their inclusion. Such processes include giving them a voice, providing meaningful opportunities and improving access to proximity resources, while respecting their rights [24, 28], fighting systemic ageism [29], and reviewing policies on participation in ageing [30, 31]. Promotion of social participation should consider a variety of life experiences, foster structural and cultural access to participatory settings, and offer spaces supporting new identities, including ageing with disabilities.

To expand the study of social participation and better understand, encourage and value older adults’ contribution to society, it is important to adopt a consensual and current definition of the concept. Although a previous review contained a content analysis of definitions and proposed a synthesis [7], a qualitative study presented results according to dimensions [32], and a concept analysis was carried out [33], many researchers still define this concept in their own way [34], which only exacerbates the confusion surrounding the meaning of social participation. Moreover, a recent study of the current generation of older adults reported a lack of alignment between their aspirations, concerns and participation opportunities, especially for women [35]. As witnesses to or being involved in societal advances in social, civil and political rights, this generation is diversified and generally reaches older age in better health and living active lives, searching for freedom, wishing to start new life projects, and advocating for self-determination and a greater citizen presence [36]. They also report needing spaces to contribute and do their activities, regardless of their health and without worrying about being productive and useful [37, 38]. Today’s ageing generation wants to participate and be recognised and active, not necessarily in roles valued by society or liberal policies based on contributing and volunteering, but in ways that reflect their own interests and capacities. Empowered older adults can describe their own experiences and reality [39]. Moreover, in keeping with approaches involving personalisation [40] and reablement [41], older adults should be involved in revisiting the definition of social participation, i.e. given a voice in the conceptual work. This paper provides an updated inventory and synthesis of definitions of social participation in older adults. Based on a critical review by content experts and knowledge users, a consensual definition is proposed.

Methods

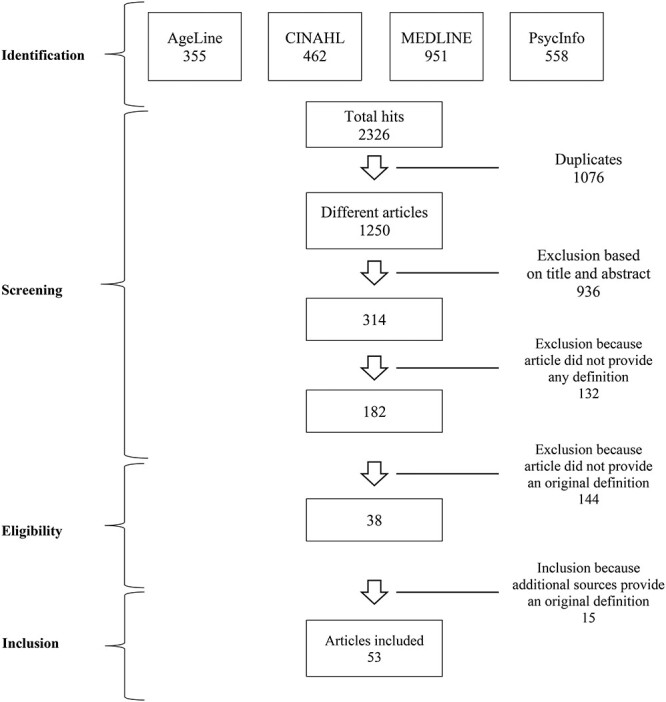

Following PRISMA guidelines [42], including collaboration between researchers and knowledge users [43] and validation by a documentalist (FL), the methodological framework for scoping studies [44, 45] was used to synthesise current knowledge concerning definitions of social participation in older adults. Papers retrieved were published between February 2009 and March 2020 in four databases with relevant keywords (Table 1). Papers were excluded if written in languages other than English or French or if they targeted a narrower concept (such as only participation in a senior centre or volunteering) that potentially did not fully represent the complexity of the concept of social participation. Inclusion criteria were that documents must: (i) report an empirical study, review or conceptual paper, and (ii) provide a definition of social participation. The definition selected must be an original statement (i.e. not refer to another source) of the meaning or description of the target concept. The title and, when available, abstract were reviewed for all papers identified through electronic searches carried out by MLT and ÉL. Reference lists, personal reference files of the principal investigator (ML), and websites were also searched.

Table 1.

Synthesis of databases searched, selected keywords and search strategies*

| Databases | MEDLINE (with Full Text), CINAHL, AgeLine and PsycInfo |

|---|---|

| Keywords[strategy: | 1. elder* OR seniors OR old* adult* OR geriatric OR aged OR ageing OR aging OR older people |

| 1 AND 2] | 2. community participation OR social participation OR social involvement OR social engagement OR community involvement OR community engagement OR civic participation OR social isolation OR social integration OR social contact* OR social activity* OR social inclusion* OR social interaction* OR solitude OR loneliness OR lonely OR social exclusion* |

*Complete search strategy is available upon request.

Conceptual definitions were extracted from each paper by MLT and ÉL and content-analysed using seven predetermined interrogative pronouns: who, how, what, where, with whom, when and why [7]. These pronouns identified critical dimensions of the concept of social participation [46]. Themes emerging from this condensation were deductively organised and renamed according to the Human Development Model–Disability Creation Process (HDM–DCP), a model of human development and disability [47] similar to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [48] in terms of approaches, objectives, and elements of the models’ components [49]. The HDM–DCP illustrates interactions between personal and environmental factors, and participation. Three of the researchers (MLT, MLB, KG) independently performed the content analysis with an inter-rater agreement before discussion of 96.9% (number of identical codes/total number of codes); it was then validated by the principal investigator (ML). All discrepancies were resolved through discussion between at least two members of the interdisciplinary research team, with final decisions approved by the principal investigator (ML).

To enrich and validate the results of this first step, as is often done in scoping studies [43], the dimensions identified with the seven interrogative pronouns provided the starting point for a 90-minute workshop conducted by the principal investigator (ML). This workshop aimed to reach a consensus on key elements of the definition of social participation and identify participants’ perceptions of related challenges and concerns. The workshop involved 32 content experts and knowledge users, i.e. 11 researchers, 8 partners, 7 collaborators and 6 students from an interdisciplinary (social work, medicine, occupational therapy, etc.) emerging partnership on older adults’ social participation [50, 51]. While workshop participants were mainly academics who conducted research on social participation, partners and collaborators came from community organisations working directly with or representing older adults (e.g. seniors’ groups, volunteer organisations and roundtables across the province). All dimensions identified were discussed, not just the commonest. The workshop began with testimony concerning social participation from three older adults and, to validate the main ideas, finished with a synthesis of the proposal. The workshop was audiotaped and a research professional took notes, mainly on a clipboard. The workshop also included a 15-minute PowerPoint presentation summarising preliminary results, followed by a 60-minute discussion on which key elements to retain. During this discussion, older adults primarily shared their views while some of the researchers briefly raised points from their own studies to stimulate debate. The notes and audiotape were considered throughout the content analysis of the definitions and when proposing a consensual definition. By revisiting the definitions three times, i.e. synthesis and workshop, and triangulating these perspectives, the authors of the present paper corroborated the analysis and a consensus on the definition was reached. This work was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council emerging partnership [#890–2012-0034].

Results

Of the 2,326 papers retrieved through electronic searches, almost half (n = 1,076; 46.3%) were duplicates and 936 did not meet the inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts (Figure 1). Of the remaining 314, more than two fifths were excluded (n = 132; 42.0%) since they did not provide a definition of social participation; nearly half were eliminated (n = 144; 45.9%) because they referred to another source. Ultimately, 54 original definitions (from 53 papers), 15 of which were added because of extended search strategies (reference lists, suggestions from colleagues, websites; Figure 1), were extracted and content-analysed (Table 2). Year of publication of the papers containing an original definition ranged from 1987 to 2020. Almost three quarters (n = 38; 71.7%) were published after 2010, with the most productive year being 2019 (n = 7; 13.2%). A majority of first authors were from North America (n = 20; 37.7%) and Europe (n = 17; 32.1%), principally working in healthcare and social services (n = 36; 69.2%; medicine, social work, psychology), and especially public health (n = 14; 26.9%). More than one-third of the journals that published the papers were from the fields of public health (n = 20; 37.7%) and gerontology or geriatrics (n = 18; 34.0%), with nearly one-tenth from rehabilitation (n = 5; 9.4%). Only a limited number (<6% each) of the definitions came from the psychology, sociology, education and social work literature. Most papers specifically concerned older adults (n = 36; 66.7%) and used the term social participation (n = 30; 56.6%) or social engagement (n = 16; 30.2%; Table 2). A majority (n = 41; 77.4%) reported empirical results, mostly from quantitative cross-sectional (n = 24; 45.3%) or longitudinal (n = 12; 22.6%) studies. One-fifth (n = 11; 20.8%) of the papers were more conceptual, with the majority from reviews.

Figure 1.

Flow chart

Table 2.

Definitions of social participation identified through an extensive search of the literature from February 2009 to March 2020 (N = 54)

| #Concepts (Author) [ref:page] | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Social participation (Hanson & Östergren) [52:850] | How actively the individual takes part in activities of formal and informal groups in society |

| Social engagement (Mor et al.) [53:2, 6] | Ability to take advantage of opportunities for social interaction; nursing home residents’ involvement in the social and recreational life of the facility |

| Social participation (Baum et al.) [54:415] | Individuals’ levels of participation in both social and civic affairs |

| Civic engagement (Adler & Goggin) [55:236] | Ways in which citizens participate in the life of a community in order to improve conditions for to others or to help shape the community’s future |

| Social participation (Lindström & The Malmö Shoulder-Neck Study Group) [56:283] | Person takes part in the activities of formal and informal groups as well as other activities in society |

| Social engagement (Hartwell & Benson) [57:331] | The extent to which individuals participate in a broad array of social roles, relationships and activities |

| Social participation (Plug et al.) [58:1811] | Ability to participate in work and education |

| Social participation (Brodie et al.) [59:5] | Collective activities that individuals may be involved in as part of their everyday lives. This might include: being a member of a community group, a tenant’s association or a trade union; supporting the local hospice by volunteering; and running a study group on behalf of a faith organisation |

| Social engagement (Dupuis-Blanchard) [60:1189] | A psychological thought process and a conscious behaviour that shapes all forms of social relationships and by which social ties and social networks are derived. This includes both relationships that are a source of social support and those that are less supportive |

| Social engagement (Park) [61:462] | Making social and emotional connections with people and the community; relationships with family, friends, and persons within the facility, social interactions through activities, reciprocity of relationships |

| Social engagement (Rubio et al.) [62:2] | Community involvement, for example, in terms of membership of neighbourhood associations, religious groups or nongovernmental organisations; formal social relations |

| Social participation (Broese van Groenou & Deeg) [63:448] | Social activities outside the home that provide opportunities to meet other people in productive or recreational activities |

| Social participation (Dalemans et al.) [64:537] | Performance of people in social life domains through interaction with others in the context in which they live |

| Social engagement (Kamiya et al.) [65:2] | A combination of objective and subjective measures of the salient aspects of people’s ‘social’ existence. The objective measures are defined by [. . .] participation in social groups (affiliation to or membership in religious, voluntary, political, and social associations or activities). The subjective measures comprise of perceptions of available emotional support from spouse, children, relatives and friends |

| Social participation (Levasseur et al.) [7:2146] | Person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community |

| Social participation (Andonian & MacRae) [66:2] | Older adults [. . .] involved and meaningfully engaged within the contexts of their lives, such as community, friends and areas of interest |

| Social participation (Guillen et al.) [67:333] | Contacts a person has with other individuals •-Informal: interactions that an individual has with relatives, friends and work colleagues in an informal setting •-Formal: interactions resulting from involvement in established organisations in society |

| Social engagement (Timonen et al.) [68:52] | Participation in leisure activities and volunteering, and connectedness to family and friendship networks |

| Civic engagement (Ekman & Amnå) [69:291, 296] | Individual or collective actions: •-Individual: activities based on personal interest in and attention to politics and societal issues •-Collective: voluntary work to improve conditions in the local community, for charity, or to help others (outside the own family and circle of friends) Activities within the civil domain |

| Social participation (Legh-Jones & Moore) [70:1363] | Person’s level of engagement in formal and informal groups |

| Social engagement (Min et al.) [71:2] | Formal social engagements and social interactions with other friends and relatives |

| Social engagement (Thomas) [72:549] | Participation in activities that involve interactions between or among people, capturing a broader array of social interactions and intensity of interaction that may contribute to greater social integration |

| Community participation (Chang et al.) [73:772] | Active involvement in activities that are intrinsically social and either occur outside the home or are part of a nondomestic role |

| Social participation (Ontario Seniors’ Secretariat et al.) [74:7] | Interaction that older adults have with other members of their community and the extent that the community itself makes this interaction possible |

| Social participation (Takeuchi et al.) [75:2] | Person’s involvement in social activities |

| Social engagement (Walker et al.) [76:939] | Contacts or connections between individuals that include some element of socio-emotional exchange, that is, flows of interactive, utilitarian and affective elements |

| Social participation (Buffel et al.) [77:657] | Formal [. . .] voluntary commitment to community organisations on a regular basis |

| Social participation (Dong & Simon) [78:82] | Engagement in daily social activities |

| Social engagement (Jang et al.) [79:642] | Participation in social activities and socialisation with others |

| Social participation (Kanamori et al.) [80:1] | Participation in civic groups that an individual can join, regardless of occupation or family situation |

| Social participation (Lewis) [81:274]Social participation (Michielsen et al.) [82:371] | Being actively involved with family and community •-Formal: participation in community organisations •-Informal: participation more based on personal development and well-being |

| Social engagement (Zhang et al.) [83:334] | Carrying out meaningful social roles through activities embedded within social relationships |

| Social participation (Niedzwiedz et al.) [11:25] | Attending external activities, such as social clubs or volunteering |

| Social participation (Provencher et al.) [84:976] | Accomplishing an attempted life habit without difficulty |

| Social participation (Tomioka et al.) [85:555] | Person’s engagement in social groups |

| Social participation (Bourassa et al.) [86:133] | People’s involvement in social activities |

| Community participation (Lin) [87:1161] | Involvement in local economic, political, cultural and voluntary activities |

| Social participation (Carver et al.) [88:2] | Form of social interaction that includes activities with friends, family and/or other individuals |

| Social engagement (Shibayama et al.) [89:1062] | Participation in social activities, such as community events, volunteerism or providing support to older people |

| Social participation (Tomioka et al.) [90:801] | Respondent’s social group involvement |

| Community integration (Camacho et al.) [91:526] | Community involvement and interaction with social networks (e.g. attended religious services, attended a public meeting or visited friends or relatives) |

| Social participation (Chanda & Mishra) [92:3] | Involvement in society had occurred [. . .] The aspects were: public meeting, attending a club, participating in society or other meetings, etc. |

| Social engagement (Gyasi et al.) [93:156] | Interaction with neighbours and participation in social activities including attending religious services, social clubs/organisation meetings, sports/cultural activities and civic/political organisations |

| Social participation (Hosokawa et al.) [94:317] | Both aggressive participation and passive participation in social interactions (i.e. both time spent in social interaction and time spent in presence of others together) |

| Social engagement (Kubota et al.) [95:187] | Taking part in events, meetings and activities within a local community |

| Social participation (Pan et al.) [96:1959] | Two categories •-Formal: participation through membership of an organised association •-Informal: day-to-day activities initiated by older people themselves, without an organisation |

| Social participation (Zheng et al.) [97:6] | Various activities in which the older adults participate in their neighbourhood, including five styles: volunteer works, self-management and mutual assistance activities, lectures and reports, recreational and sports activities, and interest groups |

| Social participation (Aroogh & Shahboulaghi) [33:68] | Conscious and active engagement in outdoor social activities leading to interacting and sharing resources with other people in the community, and the person has a personal satisfaction resulting from that engagement |

| Social participation (Government of Quebec) [98] | Participating in activities of a social nature, i.e. nurturing meaningful relationships, being part of a community, and participating in group, volunteer or paid work activities |

| Social engagement (Luo et al.) [99:2] | To engage in both individual and society-level activities. Also called social participation or social involvement, forms the basis of social relationships or participation in a community and provides a sense of belonging, social identity, and fulfilment |

| Social involvement (Schwartz et al.) [100:2] | •-Informal: relationships with people from one’s social network, such as family and friends, and focuses on useful interactions that entail provision of support in which adults are needed and beneficial •-Formal: activity in formal organisations, such as volunteering |

| Civic engagement (Serrat et al.) [101:39] | Psychological attentiveness to social and political issues |

| Civic participation (Serrat et al.) [101:39] | Action [on social and political issues]; behavioural in nature; activities conducted individually (termed individual, private or informal participation) or within a group or organisation (termed collective, public or formal participation); civic activities may primarily aim to help others, solve a community problem or produce common good, with no manifest political intention (referred to as social, civil, community, pre-political or latent political participation), or may explicitly seek to influence political outcomes (termed political participation or manifest political participation) |

Definitions

According to the content analysis based on the seven interrogative pronouns, dimensions related to how and what were found in most definitions (Table 3). Dimensions concerning who and where and with whom were present in almost half the definitions. Dimensions related to when and why were found less often (Table 3). No definitions specifically targeted instrumental activities or responsibilities (from the subcategories of activities and social roles, respectively; what), current (when) and satisfaction of needs or survival (why), but one definition newly focused on educating (from the contribution subcategories; why). Most definitions focused on people (who) involved (how) in activities providing interactions (what) with others (with whom) in society or the community (where). Following is a detailed description of the dimensions identified in the definitions for each interrogative pronoun.

Table 3.

Synthesis of the content analysis of the original definitions of social participation found in the ageing literature

| Interrogative pronouns | Dimensions [reference # of definition provided in Table 2 retrieved from February 2009 to March 2020 only] | Frequency (%) Current synthesis (N = 54) | (%) Previous synthesis* (N = 43) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By dimensions | Total** | By dimensions | Total** | ||

| Who | 1. People2–4, 6, 8, 13, 14, 16, 24, 37, 47, 48, 52 | 13 (24.1) | 23 (42.6) | (14) | (53.5) |

| 1.1 Person1, 5, 15, 17, 20, 25, 30, 36, 41, 49 | 10 (18.5) | (44.2) | |||

| How | 2. Involvement1–6, 8, 11, 14–18, 22, 23, 25, 29–32, 34, 37, 38, 40–48, 50, 51, 54 | 35 (64.8) | 44 (81.5) | (62.8) | (76.7) |

| 2.1 Engagement16, 20, 21, 28, 36, 49, 51, 54 | 8 (14.8) | (9.3) | |||

| 3. Performance2, 7, 13, 19, 35, 54 | 6 (11.1) | (30.2) | |||

| What | 4. Activities1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 14–16, 19, 22, 23, 30, 33, 34, 35, 39, 46–48, 50, 52, 54 | 22 (40.7) | 50 (92.6) | (13.9) | (88.4) |

| 4.1 Social activities1, 3, 8, 11, 12, 14, 19, 25, 29, 37, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48–51, 54 | 19 (35.2) | (46.5) | |||

| 4.1.1 Productive activities12 | 1 (1.2) | (7.0) | |||

| 4.1.1.1 Work7, 50 | 2 (3.7) | (16.3) | |||

| 4.1.1.2 Voluntary activities8, 14, 18, 19, 27, 35, 38, 40, 48, 50, 52 | 11 (20.4) | (16.3) | |||

| 4.1.2 Community activities3, 8, 14, 19, 34, 40, 42–44, 46, 48, 53, 54 | 13 (24.1) | (25.6) | |||

| 4.2 Recreational activities12, 18, 44, 48 | 4 (7.4) | (18.6) | |||

| 4.3 Daily activities28, 47, 51 | 3 (5.6) | (11.6) | |||

| 4.4 Instrumental activities | – | (7) | |||

| 5. Social roles1, 5, 6, 17, 20, 21, 27, 32, 33, 47, 52 | 11 (20.4) | (16.3) | |||

| 5.1 Responsibilities | – | (4.7) | |||

| 6. Social interactions2, 6, 9, 10, 11–15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 26, 29, 33, 39, 42, 44, 45, 50–52 | 24 (44.4) | (51.1) | |||

| Where | 7. Environment2, 13, 17 | 3 (5.6) | 23 (42.6) | (2.3) | (60.5) |

| 7.1 Community or society1, 4, 5, 11–13, 15, 17, 19, 23, 38, 41, 43, 46, 48, 49–52, 54 | 20 (37.0) | (46.5) | |||

| 7.1.1 Organisations11, 17, 30, 32, 43, 47, 52 | 7 (13.0) | (20.9) | |||

| With whom | 8. Others10, 13, 14, 16–19, 21, 22, 24, 26, 29, 31, 39, 42, 44, 52 | 17 (31.5) | 26 (48.1) | (32.6) | (48.8) |

| 8.1 Group1, 5, 10, 11, 14, 16, 20, 27, 31, 36, 41, 50, 54 | 13 (24.1) | (27.9) | |||

| When | 9. Regular8, 27 | 2 (3.7) | 2 (3.7) | (16.3) | (23.3) |

| 10. Current | – | – | (7) | ||

| Why | 11. Development9, 12, 23, 26, 32, 53, 54 | 7 (13.0) | 15 (27.8) | (9.3) | (44.2) |

| 12. Meaningfulness14, 16, 19, 22, 49, 51, 52, 54 | 8 (14.8) | (25.6) | |||

| 12.1 Contribution22 | 1 (1.2) | (9.3) | |||

| 12.1.1 Helping4, 19, 49, 54 | 4 (7.4) | (16.3) | |||

| 12.1.2 Receiving52 | 1 (1.2) | (9.3) | |||

| 12.1.3 Educating7 | 1 (1.2) | – | |||

| 13. Satisfaction of needs or survival | – | – | (16.3) | ||

*Retrieved from January 1980 to February 2009 [7]

* *The same definition can appear under more than one dimension but only once for the total of each interrogative pronoun.

Who—Although one paper in five defined social participation from an individual perspective (person; Table 3), most definitions took a population perspective (people).

How—Social participation was mostly defined as involvement, i.e. taking part, and included participation, connection, contribution or integration of the person. While engagement referred to a stronger commitment and was mostly emphasised by public health, performance focused on actions and ability to take advantage of opportunities or participate.

What—Social interactions and activities were mainly found in the definitions, and generally came from the field of gerontology and geriatrics. Papers referred to life situations or different kind of activities: other, external, individual, collective, various, formal, informal, paid or voluntary. For one definition [62], social engagement specifically involves formal social relations, as opposed to informal ones that include ties to family and friends.

Where—Social participation was more commonly defined as happening in the community or society, especially in the public health literature, but also occurred in organisations, mostly related to gerontology and geriatrics. No definition specifically mentioned virtual participation.

With whom—Definitions mentioned that social participation involves family, friends, neighbours or other individuals, especially in gerontology and geriatrics, and also groups or associations, mostly in the public health field. Five definitions described how others or groups are involved, namely by offering social and emotional support, having a reciprocal relationship, or making the interaction possible.

When—According to two definitions, social participation takes place regularly.

Why—Finally, and mainly from the gerontology literature, approximately one definition in four mentioned that social participation involves development, mainly personal but also social (e.g. opportunities), or meaningfulness, such as helping others. Meaningfulness is based on older adults’ interests and what gives them a sense of belonging or fulfilment or contributes to their identity. Only one definition considered social participation as including support from others or being educated.

Co-construction of an interdisciplinary consensual definition

According to content experts and knowledge users and based on previous results and testimony from three older adults, social participation can be defined as the action of being involved in community life, socially or politically and structured by the environment, which places can be shared, and which are significant. Participating socially is a conscious, free choice, not an obligation, and it takes various evolving but significant forms (leisure, volunteering, or social and community activities) according to available time. Social participation is highly personalised, i.e. based on individual priorities, motivations, and interests, and involves social interactions and relationships with others. While it can be achieved for oneself and simultaneously for community well-being and development, social participation gives life meaning. Based on the literature review and to better represent older adults, social participation can be defined as a person’s (who) involvement (how) in activities providing interactions (what) with others (with whom) in community life and in important shared spaces (where), evolving according to available time and resources (when), and based on the societal context and what individuals want and is meaningful to them (why).

Discussion

This paper provides an updated inventory and synthesis of 55 definitions of social participation in older adults, enriched by a discussion with content experts and knowledge users. Based on these findings, social participation can be defined as a person’s involvement in activities providing interactions with others in community life and in important shared spaces, evolving according to available time and resources, and based on the societal context and what individuals want and is meaningful to them. A consensual definition is important in order to better communicate, develop or select measuring instruments, intervene, develop policy or analyse research results [7]. Although it shares similarities with the previous synthesis [7], this new definition emphasises the where, when and why. One conceptual analysis of social participation also emphasised the importance of community-based activities, interpersonal interactions, sharing of resources, active participation and individual satisfaction [33]. The why of the current definition is also globally related to all dimensions of social participation identified by Raymond and colleagues [32], which were developing significant relationships, enjoying pleasant group activities, engaging in a collective project, assisting and supporting each other, sharing knowledge, and being empowered in decisions concerning themselves. These dimensions provide clear examples of what older adults want and what contributes to their development and is meaningful to some of them. However, this does not constitute a norm and may differ from societal expectations, an important point that cannot be overemphasised. Linked to the key elements of the mobilisation process (sense of belonging and attachment, learning and stimulation, self-accomplishment, health and well-being, reciprocity, community development and social change) [32], the dimensions also highlight the involvement and even the engagement of older adults. Compared to involvement, engagement indicates a contribution that can be more demanding and sustained [7]; this appeared more often in recent definitions. Finally, the number of original definitions increased compared to the previous synthesis. This may be attributable, not just to the longer period, but also to the greater importance of this concept in the last decade or to the persistent lack of agreement.

Given the importance of active ageing and the contribution of older adults to society, socioeconomic and personal development, benefits for older adults and society, self-actualisation and goal attainment. Also emphasising the why, the influence of some international health policies must not reinforce normative standards or society’s expectations and stigmatise older adults who choose not to be or cannot be involved in some social activities. Older adults can participate socially without being involved in an organisation, such as by doing activities with their grandchildren or helping neighbours, family, friends or others, or even during everyday activities such as shopping or going to the hairdresser. While ageing, personal (e.g. capacities) and environmental (e.g. architectural barriers) resources that are mobilised to participate socially can change [47] and might necessitate assistance from community organisations and health and social professionals [102]. To encompass a broader perspective of social participation, professionals who work with older adults might also help them to use relevant resources, and promote their autonomy and connectedness with the community [98]. Social participation must be recognised as a personal choice and human right, and health policies should include actions to facilitate involvement in activities or interactions meaningful to people, especially older adults with disabilities or insufficient personal or environmental resources.

Compared to the previous synthesis [7], recent definitions referred less often to where social participation takes place. Based on the workshop, community is important, as is community life, which highlights the importance of social interactions and activities that take place in the neighbourhood and other public spaces. During the COVID-19 pandemic and despite sanitary measures, using public spaces generated anxiety in older adults and most people worried about infecting family members or friends through social interactions [103], which greatly increased the risk of being socially isolated [104]. To foster physical distancing and restrict propagation of the virus, the size and ventilation of these public spaces and building materials used must be rethought. Friendliness and safety of neighbourhoods are also important factors associated with social participation that have been emphasised not only in policies (e.g. [28] or [8]) but also in empirical studies synthesised in a review [105]. Sometimes the environment itself can cause social exclusion [25], like stairs for people with limited mobility. With advancing age, life space can be even more restricted and the neighbourhood becomes a central element in the social participation of older adults [106, 107], including interactions between neighbours [108].

Time was also mentioned less often in this new synthesis, yet evolution of the concept over time is an important dimension, which was reported in this study’s workshop and documented in previous studies [109–115]. For instance, when interviewed about their neighbourhood participation, New Zealanders aged 85 and over reported holding onto everyday life as participating and being concerned about maintaining their capacities while ageing [116]. Evolution can occur not just in individuals but also between generations [35], justifying the need to revisit the concept over time, especially when important societal changes occur, such as increased use of social media or a pandemic. The workshop also raised the issue of the time available to participate socially, a dimension linked to ‘optimal’ participation, being the fit between an individual’s reality governing how (and how often; when) social activities are done and expectations about them [19].

Although the why and, more specifically, reference to meaningfulness were added after the workshop, fewer definitions in the recent literature included this dimension compared to the previous synthesis [7], a finding that may concern the baby boomer generation which values freedom, new life projects, self-determination and greater citizen presence [36]. In addition, older adults may feel they contribute to society and fulfil a role when they help others, such as by volunteering, babysitting or caring for family members [117]. The importance of meaningful activities and purposeful life has been highlighted, especially in the occupational sciences [118], and there are emerging interventions that empower older adults to develop their own routines fostering their health and making life more fulfilling. For example, Lifestyle Redesign® [119], a preventive occupational therapy intervention has been shown to improve health, be cost-effective [120] and has been adapted to many contexts, including Quebec, Canada [121, 122]. While it is important to prevent loneliness and isolation, social participation should not only be a way for older adults to stay active, it should also increase their well-being, feeling of being valued and sense of purpose. Finally, rather than being an obligatory contribution to society, including economic activities, meaningfulness should have a more central place in health policies, according to the content experts and knowledge users in this study. Thus, to improve health promotion, these policies should increase their scope to specifically include informal and meaningful participation, which would encompass a broader spectrum of the ageing population.

Strengths and limitations

Expanding upon a previous synthesis and using a rigorous, innovative procedure, a methodological framework for scoping studies and content analysis using interrogative pronouns, this study presents an in-depth review of many original definitions of social participation found in various multidisciplinary databases. This procedure involved at least two people analysing the content of definitions and a workshop with content experts and knowledge users from an emerging interdisciplinary partnership on social participation. Among its limitations, this study did not include the concepts of participation, societal participation, handicap, disability, meaningful activities and occupation, which generated too many unrelated results, although some papers using these concepts might have been relevant. Moreover, retrieving original definitions was occasionally challenging as papers sometimes define the concept implicitly or mainly for operationalisation purposes. Finally, although they might reflect an evolution in the definitions or different perspectives in the group, opinions from two groups of authors [85, 90, 101] might be overrepresented in the analysis as two original definitions were extracted for each group.

Conclusion

This scoping study provides an updated inventory and synthesis of definitions of social participation in older adults enriched by a critical review involving content experts and knowledge users. Although the literature mostly defined social participation as people’s involvement in activities providing interactions with others in society or the community, content experts and knowledge users emphasised the importance of community life and shared spaces. Moreover, social participation should be seen as evolving with available time and resources and based on what individuals want and is meaningful to them [123] and the societal context. As the pandemic clearly showed, social participation and interactions are essential for people’s well-being. To enable community organisations, healthcare providers and decision-makers to encourage social participation, on the ground and in policies, a deep understanding of its conceptualisation is needed as it evolves with virtual communications and respect for social distancing. In their studies, researchers must provide a definition of social participation and choose a measuring instrument accordingly. Future studies should involve older adults, family members and professionals working with them and examine how social participation is operationalised and measured. To make it easier to compare research results, the aim should be to achieve a consensus regarding a single definition and a measuring instrument.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Évelyne Laroche (ÉL), Karine Gagnon (KG), Francis Lacasse (FL), Emanuelle Mignot and Mélanie Lopez for their help with the literature review, and the interdisciplinary members from the emerging partnership who participated in the workshop on definitions.

Contributor Information

Mélanie Levasseur, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada; School of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada; Institute on Aging and Seniors’ Social Participation, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada.

Marika Lussier-Therrien, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada.

Marie Lee Biron, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada.

Émilie Raymond, Institute on Aging and Seniors’ Social Participation, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; School of Social Work and Criminology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada.

Julie Castonguay, Institute on Aging and Seniors’ Social Participation, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; School of Social Work and Criminology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; College Centre of Expertise in Gerontology, Cégep de Drummondville, Drummondville, Québec, Canada.

Daniel Naud, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada.

Mireille Fortier, Institute on Aging and Seniors’ Social Participation, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada.

Andrée Sévigny, Institute on Aging and Seniors’ Social Participation, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; College Centre of Expertise in Gerontology, Cégep de Drummondville, Drummondville, Québec, Canada.

Sandra Houde, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada; Bishop’s University, Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada.

Louise Tremblay, Research Centre on Aging, Eastern Townships Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre – Sherbrooke University Hospital Centre (CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS), Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council emerging partnership (#890–2012-0034). Mélanie Levasseur is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator (#360880).

References

- 1. World Health Organisation (WHO) . Ageing and health. World Health Organisation; 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (15 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser S, Lagacé M, Bongué B et al. Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing 2020; 49: 692–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Employment and Social Development Canada . Emergency Community Support Fund. Canada.ca: 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/emergency-community-support-fund.html (15 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Government of Quebec . Soutien financier à des organismes travaillant auprès des aînés en situation de vulnérabilité [Financial support for organizations working with vulnerable seniors]. Quebec.ca: 2021. https://www.quebec.ca/famille-et-soutien-aux-personnes/aide-financiere/soutien-financier-organismes-travaillant-aupres-aines-situation-vulnerabilite/ (15 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charron E, Tremblay-Paradis O, Castonguay J et al. Le bénévolat des personnes aînées en période de pandémie : présentation des résultats préliminaires [Seniors volunteering during a pandemic: presentation of preliminary results], 2020.

- 6. Statistics Canada . Crowdsourcing: Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians’ Mental Health Public Use Microdata File: 13-25-0002. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, Raymond E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med 2010; 71: 2141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization (WHO) . Global age-friendly cities: a guide. Geneva, CH: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Government of Quebec . Plan d’action 2018–2023 Un Québec pour tous les âges [Action Plan 2018–2023 A Quebec for All Ages]. Sainte-Foy, QC: Ministère de la santé et des Services sociaux du Québec, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noack R. Isolation is rising in Europe. Can loneliness ministers help change that? Washington Post; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/02/02/isolation-is-rising-in-europe-can-loneliness-ministers-help-change-that/ (9 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niedzwiedz CL, Richardson EA, Tunstall H, Shortt NK, Mitchell RJ, Pearce JR. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: is social participation protective? Prev Med 2016; 91: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nyqvist F, Pape B, Pellfolk T, Forsman AK, Wahlbeck K. Structural and cognitive aspects of social capital and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Soc Indic Res 2014; 116: 545–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psych Sci 2015; 10: 227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith SG, Jackson SE, Kobayashi LC, Steptoe A. Social isolation, health literacy, and mortality risk: findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Health Psychol 2018; 37: 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010; 7: e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levasseur M, Gauvin L, Richard L et al. Associations between perceived proximity to neighborhood resources, disability, and social participation among community-dwelling older adults: results from the VoisiNuAge study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 1979–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, Whiteneck G. Accomplishment level and satisfaction with social participation of older adults: association with quality of life and best correlates. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newall N, McArthur J, Menec V. A longitudinal examination of social participation, loneliness, and use of physician and hospital services. J Aging Health 2015; 27: 500–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rochette A, Korner-Bitensky N, Levasseur M. ‘Optimal’participation: a reflective look. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28: 1231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swinford E, Galucia N, Morrow-Howell N. Applying gerontological social work perspectives to the coronavirus pandemic. J Gerontol Soc Work 2020; 63: 513–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richaud L, Amin A. Mental health, subjectivity and the city: an ethnography of migrant stress in shanghai. Int Health 2019; 11: S7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson JK, Stewart AL, Acree M et al. A community choir intervention to promote well-being among diverse older adults: results from the community of voices trial. J Gerontol B 2020; 75: 549–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sacker A, Ross A, Mac Leod CA, Netuveli G, Windle G. Health and social exclusion in older age: evidence from understanding society, the UK household longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017; 71: 681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs . Identifying social inclusion and exclusion. In: Report on the World Social Situation 2016 - Leaving no one Behind: The Imperative of Inclusive Development. New York, NY: United Nations, 2016; 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walsh K, Scharf T, Keating N. Social exclusion of older persons: a scoping review and conceptual framework. Eur J Ageing 2017; 14: 81–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prattley J, Buffel T, Marshall A, Nazroo J. Area effects on the level and development of social exclusion in later life. Soc Sci Med 2020; 246: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walsh K, O’Shea E, Scharf T. Rural old-age social exclusion: a conceptual framework on mediators of exclusion across the lifecourse. Ageing Soc 2020; 40: 2311–37. [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organisation (WHO) . Active ageing: a policy framework. Geneva, CH: WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Officer A, de la Fuente-Núñez V. A global campaign to combat ageism. Bull World Health Organ 2018; 96: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raymond E, al. et. Community participation of older adults with disabilities. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 2014; 24: 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raymond E, Castonguay J, Fortier M, Sévigny A. The social participation of older people: Get on board, as they used to say! In: Billette V, Marier P, Séguin A-M, eds. Getting wise about getting old: Debunking myths about aging. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2020; 181–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raymond É, Sévigny A, Tourigny A. Participation sociale des aînés: la parole aux aînés et aux intervenants [Social participation of seniors: What seniors and stakeholders have to say]. In: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Institut sur le vieillissement et la participation sociale des aînés de l’Université Laval, Direction de santé publique de l’Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale et Centre d’excellence sur le vieillissement de Québec du Centre hospitalier affilié universitaire de Québec, 2012.

- 33. Aroogh MD, Shahboulaghi FM. Social participation of older adults: a concept analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2020; 8: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piškur B, Daniëls R, Jongmans MJ et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil 2014; 28: 211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Majón-Valpuesta D, Pérez-Salanova M, Ramos P, Haye A. “It’s impossible for them to understand me ‘cause I haven’t said a word”: how women baby boomers shape social participation spaces in old age. J Women Aging 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van Der Vlugt E, Audet-Nadeau V, Bien vieillir au Québec. Portrait des inégalités entre générations et entre personnes aînées [Aging well in Quebec: Portrait of inequalities between generations and between seniors]. Montréal, QC: Observatoire québécois des inégalités, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinson M, Minkler M. Civic engagement and older adults: a critical perspective. Gerontologist 2006; 46: 318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raymond É, Grenier A, Lacroix N. La participation dans les politiques du vieillissement au Québec: discours de mise à l’écart pour les aînés ayant des incapacités? Développement humain, handicap et changement social 2016; 22: 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sévigny A, Frappier A, Abgrall V, Caron G. Parcours de bénévolat en soins palliatifs: diversités et similarités. Les Cahiers francophones de soins palliatifs 2015; 15: 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 301–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Francis J, Fisher M, Rutter D. Reablement: a cost-effective route to better outcomes. London, UK: Social Care Institute for Excellence London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst 2008; 6: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Levack WM. Ethics in goal planning for rehabilitation: a utilitarian perspective. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Polatajko H, Backman CL, Baptiste S, Davis J, Eftekhar P, Harvey A. Human occupation in context. In: Polatajko H, Townsend E, eds. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being, & Justice through Occupation, 2nd edition. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2007; 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fougeyrollas P, Boucher N, Edwards G, Grenier Y, Noreau L. The disability creation process model: a comprehensive explanation of disabling situations as a guide to developing policy and service programs. Scand J Disabil Res 2019; 21: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization (WHO) . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, St-Cyr TD. Comparing the disability creation process and international classification of functioning. Disability and Health models CJOT 2007; 74: 233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sévigny A, Raymond E, Castonguay J, Fortier M. Développement de partenariat sur la participation sociale des aînés [Development of a partnership concerning the social participation of seniors], 2015.

- 51. Raymond E. La participation sociale des aînés: des savoirs en action [Social participation of older adults: knowledge in action], 2016.

- 52. Hanson B, Östergren P-O. Different social network and social support characteristics, nervous problems and insomnia: theoretical and methodological aspects on some results from the population study ‘men born in 1914’, Malmö. Sweden Soc Sci Med 1987; 25: 849–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mor V, Branco K, Fleishman J et al. The structure of social engagement among nursing home residents. J Gerontol B 1995; 50: P1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baum FE, Bush RA, Modra CC et al. Epidemiology of participation: an Australian community study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54: 414–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adler RP, Goggin J. What do we mean by ‘civic engagement’? J Transform Educ 2005; 3: 236–53. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lindström M. Malmö shoulder-neck study group. Psychosocial work conditions, social participation and social capital: a causal pathway investigated in a longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62: 280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hartwell SW, Benson PR. Social integration: A conceptual overview and two case studies. In: Avison WR, McLeod JD, Pescosolido BA, eds. Mental health, social mirror. Boston, MA: Springer, 2007; 329–53. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Plug I, Peters M, Mauser-Bunschoten EP et al. Social participation of patients with hemophilia in the Netherlands. Blood 2008; 111: 1811–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brodie E, Cowling E, Nissen N, Paine AE, Jochum V, Warburton D. Understanding Participation: A Literature Review. London, UK: Involve, Institute for Volunteering Research, and NCVO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dupuis-Blanchard S et al. The significance of social engagement in relocated older adults. Qual Health Res 2009; 19: 1186–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Park NS. The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. J Appl Gerontol 2009; 28: 461–81. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rubio E, Lázaro A, Sánchez-Sánchez A. Social participation and independence in activities of daily living: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2009; 9: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Van Groenou MB, Deeg DJ. Formal and informal social participation of the’young-old’in the Netherlands in 1992 and 2002. Ageing Soc 2010; 30: 445–65. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dalemans RJP, al. et. Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2010; 45: 537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kamiya Y, Whelan B, Timonen V, Kenny RA. The differential impact of subjective and objective aspects of social engagement on cardiovascular risk factors. BMC Geriatr 2010; 10: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Andonian L, Mac RA. Well older adults within an urban context: strategies to create and maintain social participation. Br J Occup Ther 2011; 74: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guillen L, Coromina L, Saris WE. Measurement of social participation and its place in social capital theory. Soc Indic Res 2011; 100: 331–50. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Timonen V, Kamiya Y, Maty S. Social engagement of older people. In: Barrett A, Burke H, Cronin H et al., eds. Fifty Plus in Ireland 2011: First results from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Dublin, IE: Trinity College Dublin, 2011; 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ekman J, Amnå E. Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Hum Affairs 2012; 22: 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Legh-Jones H, Moore S. Network social capital, social participation, and physical inactivity in an urban adult population. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74: 1362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Min J, Lee K, Park J, Cho S, Park S, Min K. Social engagement, health, and changes in occupational status: analysis of the Korean longitudinal study of ageing (KLoSA). PLoS One 2012; 7: e46500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. J Aging Health 2012; 24: 547–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chang F-H, Coster WJ, Helfrich CA. Community participation measures for people with disabilities: a systematic review of content from an international classification of functioning, disability and health perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 771–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ontario Seniors’ Secretariat, Accessibility Directorate of Ontario, University of Waterloo, McMaster University. Finding the right fit: age-friendly community planning. Ottawa, ON: Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Takeuchi K, Aida J, Kondo K, Osaka K. Social participation and dental health status among older Japanese adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e61741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Walker J, Orpin P, Baynes H et al. Insights and principles for supporting social engagement in rural older people. Age Ageing 2013; 33: 938. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Buffel T, De Donder L, Phillipson C, Dury S, De Witte N, Verte D. Social participation among older adults living in medium-sized cities in Belgium: the role of neighbourhood perceptions. Health Promot Int 2014; 29: 655–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dong X, Li Y, Simon MA. Social engagement among US Chinese older adults—findings from the PINE study. J Gerontol A 2014; 69: S82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jang Y, Park NS, Dominguez DD, Molinari V. Social engagement in older residents of assisted living facilities. Aging Ment Health 2014; 18: 642–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kanamori S et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e99638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lewis J. The role of the social engagement in the definition of successful ageing among Alaska native elders in Bristol Bay. Alaska Psychol Dev Soc 2014; 26: 263–90. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Michielsen M, Comijs HC, Aartsen MJ et al. The relationships between ADHD and social functioning and participation in older adults in a population-based study. J Atten Disord 2015; 19: 368–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang W, Feng Q, Liu L, Zhen Z. Social engagement and health: findings from the 2013 survey of the shanghai elderly life and opinion. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2015; 80: 332–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Provencher V, Desrosiers J, Demers L, Carmichael P-H. Optimizing social participation in community-dwelling older adults through the use of behavioral coping strategies. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 38: 972–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Association between social participation and instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults. J Epidemiol 2016; 26: 553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bourassa KJ, Memel M, Woolverton C, Sbarra DA. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment Health 2017; 21: 133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lin W. A study on the factors influencing the community participation of older adults in China: based on the CHARLS2011 data set. Health Soc Care Community 2017; 25: 1160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Carver LF, Beamish R, Phillips SP, Villeneuve M. A scoping review: social participation as a cornerstone of successful aging in place among rural older adults. Geriatrics 2018; 3: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Shibayama T, Noguchi H, Takahashi H, Tamiya N. Relationship between social engagement and diabetes incidence in a middle-aged population: results from a longitudinal nationwide survey in Japan. J Diabetes Investig 2018; 9: 1060–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: a community-based longitudinal study. J Gerontol B 2018; 73: 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Camacho D, Lee Y, Bhattacharya A, Vargas LX, Kimberly L, Lukens E. High life satisfaction: exploring the role of health, social integration and perceived safety among Mexican midlife and older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work 2019; 62: 521–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Chanda S, Mishra R. Impact of transition in work status and social participation on cognitive performance among elderly in India. BMC Geriatr 2019; 19: 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gyasi RM, Yeboah AA, Mensah CM, Ouedraogo R, Addae EA. Neighborhood, social isolation and mental health outcome among older people in Ghana. J Affect Disord 2019; 259: 154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hosokawa R, Kondo K, Ito M et al. The effectiveness of Japan’s community Centers in facilitating social participation and maintaining the functional capacity of older people. Res Aging 2019; 41: 315–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kubota A, Carver A, Sugiyama T. Associations of local social engagement and environmental attributes with walking and sitting among Japanese older adults. J Aging Phys Act 2019; 28: 187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Pan H, Donder LD, Dury S, Wang R, Witte ND, Verté D. Social participation among older adults in Belgium’s Flanders region: exploring the roles of both new and old media usage. Inf Commun Soc 2019; 22: 1956–72. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zheng Z, Chen H, Yang L. Transfer of promotion effects on elderly health with age: from physical environment to interpersonal environment and social participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Direction régionale de santé publique . Participation sociale des aînés [Social Participation of Seniors]. Santé Montréal: 2016. https://santemontreal.qc.ca/en/professionnels/drsp/sujets-de-a-a-z/participation-sociale-des-aines/information-generale/ (16 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 99. Luo M, Ding D, Bauman A, Negin J, Phongsavan P. Social engagement pattern, health behaviors and subjective well-being of older adults: an international perspective using WHO-SAGE survey data. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Schwartz E, Ayalon L, Huxhold O. Exploring the reciprocal associations of perceptions of aging and social involvement. J Gerontol B 2020; 76: 563–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Serrat R, Scharf T, Villar F, Gómez C. Fifty-five years of research into older People’s civic participation: recent trends, future directions. Gerontologist 2020; 60: e38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Levasseur M, Lefebvre H, Levert M-J et al. Personalized citizen assistance for social participation (APIC): a promising intervention for increasing mobility, accomplishment of social activities and frequency of leisure activities in older adults having disabilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016; 64: 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dionne M, Hamel D, Rochette L, Tessier M, Tourigny A. COVID-19: Pandémie et conséquences pour les personnes âgées de 60 ans et plus [COVID-19 - Pandemic and implications for people aged 60 years and older]. Québec, QC: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Committee . COVID-19: Tackling Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Seniors in a Pandemic Context. Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2020. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/publications/3033-social-isolation-loneliness-seniors-pandemic-covid19 (16 February 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 105. Levasseur M, Généreux M, Bruneau J-F et al. Importance of proximity to resources and to recreational facilities, social support, transportation and neighbourhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: results from a scoping study. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lord S, Després C, Ramadier T. When mobility makes sense: a qualitative and longitudinal study of the daily mobility of the elderly. J Environ Psychol 2011; 31: 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Lord S, Piché D. Vieillissement et aménagement: Perspectives plurielles [Aging and planning: Plural perspectives]. Montréal, QC: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lantagne Lopez M, Godbout A, Raymond É, Landry B, Sévigny A. Revue des écrits: Le voisinage entre ainés [literature review: Neighborliness between seniors]. Sainte-Foy, QC: Institut Sur le vieillissement et la participation sociale des aînés (IVPSA). Université Laval 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Antoci A, Sacco PL, Vanin P. Social capital accumulation and the evolution of social participation. J Socio Econ 2007; 36: 128–43. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Desrosiers J, Noreau L, Rochette A, Bourbonnais D, Bravo G, Bourget A. Predictors of long-term participation after stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28: 221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Desrosiers J, Demers L, Robichaud L, Vincent C, Belleville S, Ska B. Short-term changes in and predictors of participation of older adults after stroke following acute care or rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2008; 22: 288–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Desrosiers J, Robichaud L, Demers L, Gelinas I, Noreau L, Durand D. Comparison and correlates of participation in older adults without disabilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009; 49: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Raymond K, Levasseur M, Mathieu J, Gagnon C. Progressive decline in daily and social activities: a 9-year longitudinal study of participation in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019; 100: 1629–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Rochette A, Desrosiers J, Bravo G, St-Cyr-Tribble D, Bourget A. Changes in participation after a mild stroke: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007; 14: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Viscogliosi C, Belleville S, Desrosiers J, Caron CD, Ska B. Participation after a stroke: changes over time as a function of cognitive deficits. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011; 52: 336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Conaglen J. Everyday Urban Neighbourhood Participation in Advanced Age. 2019. http://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/12580?show=full (16 February 2021, date last accessed).

- 117. van Leeuwen KM, van Loon MS, van Nes FA et al. What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. PLoS One 2019; 14: 1–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Pierce DE. Occupational Science for Occupational Therapy. 1st edition. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Clark F, Blanchard J, Sleight A et al. Lifestyle Redesign: The Intervention Tested in the USC Well Elderly Studies. 2nd edition. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Lévesque M-H, Trépanier J, Sirois M-J, Levasseur M. Effects of lifestyle redesign on older adults: a systematic review. Can J Occup Ther 2019; 86: 48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Levasseur M, Filiatrault J, Lariviere N et al. Influence of lifestyle redesign® on health, social participation, leisure, and mobility of older French-Canadians. Am J Occup Ther 2019; 73: 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Lévesque M-H, Trépanier J, Tardif M-È et al. Lifestyle redesign® (Remodeler sa vie): first pilot study among older French-Canadians. Can J Occup Ther 2020; 87: 241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Pristavec T. Social participation in later years: the role of driving mobility. J Gerontol B 2018; 73: 1457–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]