This cohort study analyzes ultra-widefield imaging data to determine whether predominantly peripheral lesions are associated with increased disease worsening beyond the risk associated with baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale score.

Key Points

Question

Does detection of predominantly peripheral diabetic retinopathy lesions (PPLs) outside the 7 standard Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study fields on ultra-widefield imaging improve the ability to predict rates of disease worsening (diabetic retinopathy progression or receipt of treatment) beyond the risk associated with baseline severity level?

Findings

In this cohort study, presence of fluorescein angiography PPL at baseline, independent of baseline diabetic retinopathy severity level, was associated with greater risk of disease worsening over 4 years, while presence of color PPL was not.

Meaning

Peripheral findings on ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography allow more accurate identification of eyes with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy at a greater risk for future disease worsening than provided by baseline severity level alone.

Abstract

Importance

Ultra-widefield (UWF) imaging improves the ability to identify peripheral diabetic retinopathy (DR) lesions compared with standard imaging. Whether detection of predominantly peripheral lesions (PPLs) better predicts rates of disease worsening over time is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether PPLs identified on UWF imaging are associated with increased disease worsening beyond the risk associated with baseline Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) score.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal observational study conducted at 37 US and Canadian sites with 388 participants enrolled between February and December 2015. At baseline and annually through 4 years, 200° UWF-color images were obtained and graded for DRSS at a reading center. Baseline UWF-color and UWF-fluorescein angiography (FA) images were evaluated for the presence of PPL. Data were analyzed from May 2020 to June 2022.

Interventions

Treatment of DR or diabetic macular edema was at investigator discretion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Predominantly peripheral lesions were defined as DR lesions with a greater extent outside vs inside the 7 standard ETDRS fields. Primary outcome was disease worsening defined as worsening 2 steps or more on the DRSS or receipt of DR treatment. Analyses were adjusted for baseline DRSS score and correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant.

Results

Data for 544 study eyes with nonproliferative DR (NPDR) were analyzed (182 [50%] female participants; median age, 62 years; 68% White). The 4-year disease worsening rates were 45% for eyes with baseline mild NPDR, 40% for moderate NPDR, 26% for moderately severe NPDR, and 43% for severe NPDR. Disease worsening was not associated with color PPL at baseline (present vs absent: 38% vs 43%; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.57-1.08; P = .13) but was associated with FA PPL at baseline (present vs absent: 50% vs 31%; HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.25-2.36; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Although no association was identified with color PPL, presence of FA PPL was associated with greater risk of disease worsening over 4 years, independent of baseline DRSS score. These results suggest that use of UWF-FA to evaluate retinas peripheral to standard ETDRS fields may improve the ability to predict disease worsening in NPDR eyes. These findings support use of UWF-FA for future DR staging systems and clinical care to more accurately determine prognosis in NPDR eyes.

Introduction

The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) is the established method for grading diabetic retinopathy (DR) and uses stereoscopic color fundus photographs to evaluate 7 defined retinal fields.1 These fields are focused primarily on the posterior pole and capture only 30% to 35% of the retinal surface. Baseline DRSS score has been shown to be highly predictive of future risk of DR worsening.2,3

Ultra-widefield (UWF) imaging captures up to 82% of the retina in a single image,4 allowing greater visualization of the retinal far periphery than with ETDRS protocol photographs. Several single-center studies and the DRCR Retina Network multicenter study Protocol AA (discussed herein) have demonstrated that DR lesions peripheral to the ETDRS fields are identified in approximately 40% of eyes and may imply a more advanced DR severity in 9% to 15% of eyes.5,6,7,8

Single-center studies have suggested that the presence of predominantly peripheral lesions (PPLs) may identify eyes at higher risk for future DR worsening independent of their baseline DRSS score.5,6,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF-FA) studies have also supported an association between PPL and peripheral nonperfusion in diabetic eyes.10,14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32

Given the improved ability to identify peripheral DR lesions outside the 7 standard ETDRS fields on UWF imaging, the DRCR Retina Network Protocol AA evaluated whether the detection of PPL on UWF-color or UWF-FA improves the ability to predict rates of retinopathy worsening over time beyond the risk associated with baseline DRSS score. We now report the 4-year longitudinal primary outcome of this multicenter study to determine whether PPLs on UWF-color photography and UWF-FA at baseline are associated with DR progression.

Methods

This prospective observational longitudinal study was conducted by the DRCR Retina Network at 37 clinical sites in the United States and Canada. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by multiple ethics boards. Study participants provided written informed consent. The protocol is available on the study website.33 The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. Study participants received a $25 or $50 gift or money card for each completed study visit. Maximum compensation to a participant was $250 over 4 years.

Study Population

Participants were at least 18 years old, had type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and had at least 1 eye with nonproliferative DR (NPDR) confirmed on ETDRS modified 7-field grading. Study eyes had no history of panretinal (scatter) photocoagulation or treatment with intravitreal agents over the previous 12 months and no center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) on clinical examination or spectral-domain optical coherence tomography as defined by prior DRCR Retina Network thresholds for central subfield thickness.34 Eyes were excluded if the investigator anticipated the need for panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal treatment within 6 months of enrollment. Participant-reported race and ethnicity were collected based on fixed categories.

Study Design

The study aimed to enroll at least 175 eyes with and 175 eyes without PPL on UWF-color images (color PPL), with approximately 40% of study eyes with mild NPDR (ETDRS level 35), 40% with moderate or moderately severe NPDR (ETDRS levels 43-47), and 20% with severe NPDR (ETDRS level 53).

Follow-up visits occurred annually for 4 years. At each visit, images were acquired with the Optos 200Tx (97.5%) or Optos California (2.5%) after pupillary dilation. Initiation of treatment for DR or DME was at investigator discretion. When initial treatment was planned, participants first underwent all study procedures.

Image Acquisition and Grading

The UWF-color imaging procedure included two 200° central images and two (or 4 at baseline) 200° steered images. Given the agreement in DRSS score between ETDRS 7-field and UWF images within the same retinal area, acquisition of ETDRS 7-field photographs was discontinued after baseline. UWF-FA was required at the baseline, 1-year, and 4-year visits.8,12,35

Photographs of the 7 ETDRS fields and all UWF images were graded at the Beetham Eye Institute of the Joslin Diabetes Center. Score on the DRSS was evaluated on ETDRS 7-field and UWF-color images, while PPL presence and extent was determined independently from UWF-color and UWF-FA images. Graders were masked to clinical characteristics and features from other imaging modalities. As previously reported,8,35 UWF images were first automatically overlaid with a template mask through which only the idealized ETDRS 7-field area was visible (termed masked). Once the masked grading was complete, the mask template was removed to reveal the full image, including the retinal periphery for grading (termed unmasked). Each lesion type (hemorrhages and/or microaneurysms [H/Ma], intraretinal microvascular abnormalities [IRMA], venous beading, and new vessels elsewhere) was graded separately and considered predominantly peripheral in a specific field if more than 50% of the lesions were in the retinal periphery compared with inside the ETDRS fields. An eye was considered to have PPL if any lesion graded in any of fields 3 through 7 was predominantly peripheral.12

Outcomes

The primary outcome (disease worsening) is a time-to-event outcome, defined as either worsening by 2 or more steps on the DRSS assessed within the ETDRS fields from the UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment over 4 years of follow-up. Secondary outcomes based on UWF-color masked images include development of proliferative DR, development of vitreous hemorrhage (including at clinical examinations), and improvement by 2 or more steps on the DRSS. Baseline presence of color PPL and FA PPL were primary risk factor candidates. Secondary risk factor candidates included baseline type of PPL (H/Ma, IRMA, venous beading, or new vessels elsewhere), number of peripheral fields with PPLs, location of PPLs (fields 3-7), and DRSS score on ETDRS images.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis comparing eyes with and without baseline PPL (color and FA) was conducted using Cox proportional hazards models with adjustment for baseline DRSS score from masked UWF-color images. A robust sandwich estimate of the covariance matrix was used to account for the correlation between the 2 study eyes of the same participant. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI were presented along with the Kaplan-Meier estimates. The proportional hazards assumptions were evaluated by testing the interaction of covariates with time and checking Martingale residuals.36 Participants who did not meet the primary outcome but received vitrectomy, intravitreal anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), or intravitreal steroid for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. Data for study participants who were lost to follow-up or completed the study without meeting the primary outcome were censored at the last completed visit.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the potential effect of informative censoring due to receipt of non-DR treatment or loss to follow-up and various imaging modalities.37,38,39 Analyses of secondary outcomes and secondary risk factors paralleled the primary outcome analysis. Comparisons of secondary PPL groups (ie, PPL by type and location) were only performed when the primary PPL risk factor demonstrated a significant association (P < .05). As type I error rate is not fully controlled at 5%, some significant findings may occur by chance. All P values were 2-sided. Analyses were performed using SAS/STAT version 15.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Participants

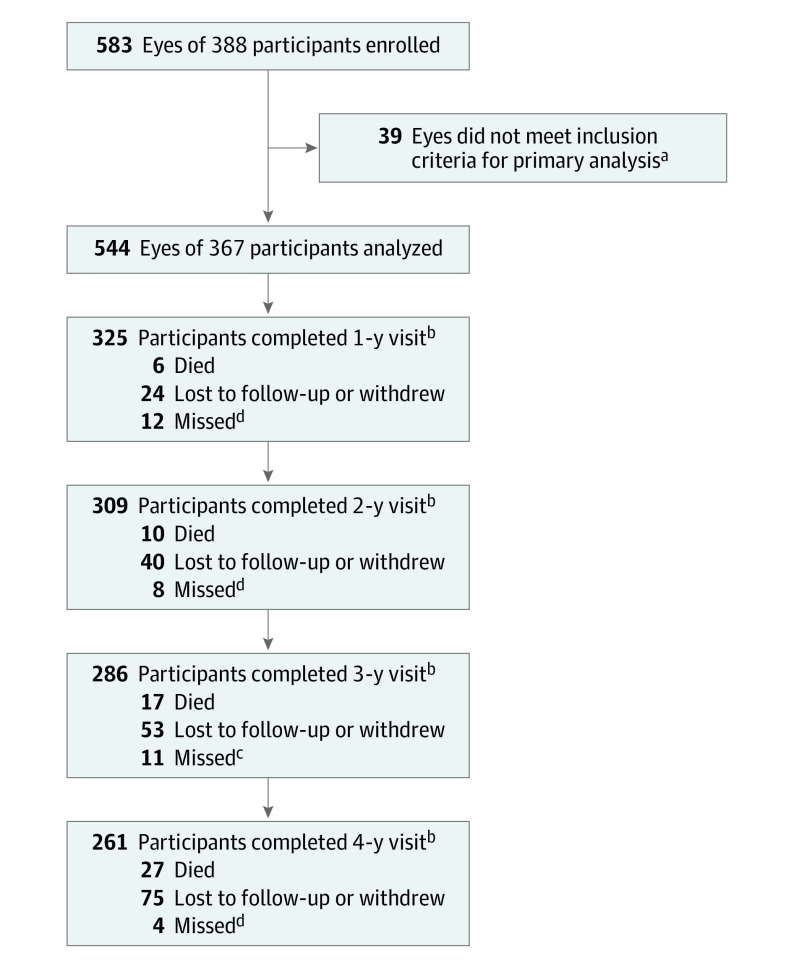

From February 2015 to December 2015, the study enrolled a total of 388 participants. Data were analyzed from May 2020 to June 2022. The analysis cohort consists of 544 study eyes from 367 participants who had at least 1 eye with NPDR on UWF-color that was gradable for PPL. The overall 4-year visit completion rate was 77%, excluding deaths (Figure 1); retention by presence of PPL is reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Median (IQR) age was 62 (53-69) years, 182 (50%) participants were female, and 249 (68%) were non-Hispanic White (Table40,41).

Figure 1. Visit Completion Over 4 Years.

The primary analysis is a time-to-event analysis. Eyes that did not meet the outcome were censored at the last completed visit.

aIncludes only participants who had at least 1 study eye with a baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale score of 35-53.

bCounts all participants who completed the visit within the following windows (±0.5 y from the target): 183-547 days for 1-year visit, 548-912 days for 2-year visit, 913-1277 days for 3-year visit, and 1278-1642 days for 4-year visit. Numbers of participants who died and were lost to follow-up or those who withdrew are cumulative.

cIncludes participants who completed only a phone visit after missing the annual visit. Participants completing the visit outside the analysis window were considered as missing the visit: 1 at year 1, 1 at year 2, and 1 at year 3.

dParticipants completing the visit outside the window were considered as missing the visit.

Table. Baseline Characteristics in the Overall Cohort.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | |

| No. of participants | 367 |

| Female | 182 (49.6) |

| Male | 185 (50.4) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62 (53-69) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White | 249 (68) |

| Black or African American | 68 (19) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 32 (9) |

| Asian | 10 (3) |

| More than 1 race | 3 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander | 1 (<1) |

| Unknown or not reported | 4 (1) |

| Diabetes type | |

| Type 1 | 50 (14) |

| Type 2 | 313 (85) |

| Uncertain | 4 (1) |

| Duration of diabetes, median (IQR), y | 20 (13-28) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, median (IQR), %a | 7.9 (7.0-9.0) |

| Insulin use | 265 (72) |

| Mean arterial pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 97 (91-106) |

| History of hypertension | 287 (78) |

| History of high cholesterol/dyslipidemia | 257 (70) |

| Taking fenofibrate at baseline | 15 (4) |

| Taking metformin at baselineb | 170 (48) |

| eGFR, median (IQR), mL/min/1.73 m2c | 86 (61-90) |

| Participants with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 49 (13) |

| Participants with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 163 (44) |

| Unknown eGFR | 155 (42) |

| ACRc | |

| Median (IQR) | 23 (8-108) |

| No albuminuria (<30) | 117 (32) |

| Microalbuminuria (30-300) | 63 (17) |

| Macroalbuminuria (>300) | 29 (8) |

| Unknown | 158 (43) |

| Participants with 2 study eyes | 177 (48) |

| Study eye ocular characteristics | |

| No. of study eyes | 544 |

| Visual acuity letter score, median (IQR) | 86 (89-81) |

| Snellen equivalent, median (IQR) | 20/20 (20/16-20/25) |

| DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF masked) | |

| Mild NPDR (35) | 172 (32) |

| Moderate NPDR (43) | 149 (27) |

| Moderately severe NPDR (47) | 79 (15) |

| Severe and very severe NPDR (53) | 144 (26) |

| DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF unmasked) | |

| Mild NPDR (35) | 138 (25) |

| Moderate NPDR (43) | 133 (24) |

| Moderately severe NPDR (47) | 103 (19) |

| Severe and very severe NPDR (53) | 158 (29) |

| Inactive PDR (60) or mild PDR (61) | 6 (1) |

| Moderate PDR (65) | 5 (<1) |

| Ungradable | 1 (<1) |

| Difference in DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF unmasked vs masked)d | |

| UWF unmasked worse | 86 (16) |

| Same grading | 450 (83) |

| UWF masked worse | 7 (1) |

| Lens status | |

| Aphakic | 1 (<1) |

| PC IOL | 134 (25) |

| Phakic | 409 (75) |

| OCT CST Spectralis equivalent, median (IQR), μme | 277 (260-295) |

| OCT volume, median (IQR), mm2f | 6.9 (6.6-7.3) |

| History of DME treatment | 119 (22) |

| Focal laser for DME | 114 (21) |

| Anti-VEGF for DME | 31 (6) |

| Corticosteroids (including implants) for DME | 5 (<1) |

| Predominantly peripheral lesions | |

| On UWF-color | 221 (41) |

| On UWF-FAg | 247 (46) |

| On both UWF-color and UWF-FAg | 136 (25) |

Abbreviations: ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; CST, central subfield thickness; DME, diabetic macular edema; DRSS, Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fluorescein angiography; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PC IOL, posterior chamber intraocular lens; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PPLs, predominantly peripheral lesions; UWF, ultra-widefield; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Unavailable for 6 participants.

Unavailable for 11 participants. Percentage is based on participants with available information.

Blood and urine samples were added approximately 5 months after study recruitment began, and baseline eGFR and urine ACR measurements were not collected for 156 participants.

Excluding 1 eye with ungradable unmasked grade. Percentage is based on eyes with available information.

Cirrus measurements were converted to Spectralis equivalents using the following formula: Spectralis = 40.78 + 0.95 × Cirrus.40

Retinal volume measurements were converted to Stratus equivalents using the following formulas: Stratus = −1.21 + 1.02 × Cirrus; Stratus = −2.05 + 1.06 × Spectralis.41

FA PPLs were ungradable for 2 eyes. Percentage is based on eyes with available information.

Among the 544 eyes, PPLs were present in 221 eyes (41%) on UWF-color and 247 (46%) on UWF-FA (2 eyes had unavailable FA PPL grading). Median baseline visual acuity letter score was 86 letters (approximate Snellen 20/20). Baseline participant and study eye ocular characteristics by PPL and by 4-year visit completion status are shown in eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1.

Among the 542 eyes with gradable color PPL and FA PPL, 136 eyes (25%) had PPL present on both images, 111 (20%) had FA PPL only, 85 (16%) had color PPL only, and 210 (39%) had PPL absent on both. Grading of baseline FA PPL and color PPL presence was discordant in 36% of eyes (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Among eyes with PPL, H/Ma was the most common type (180/221 eyes [81%] on UWF-color and 225/247 eyes [91%] on UWF-FA), and PPLs were most frequently observed in fields 3, 4, and 6 (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Treatment Initiation

Over 4 years, treatment for DR or DME was initiated in 18% of eyes with 11% receiving treatment for DR and 14% receiving treatment for DME. Treatments given by baseline DRSS subgroup are reported in eTable 5 in Supplement 1. Only 1% of eyes received treatment with anti-VEGF, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR or DME.

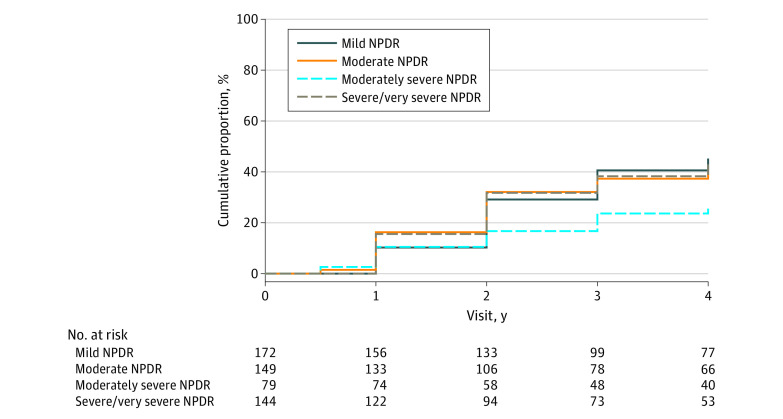

Primary Outcome: DR Worsening or Receipt of DR Treatment

The cumulative proportion of disease worsening, ie, worsening of 2 or more steps on the DRSS or treatment for DR through 4 years was 40% (95% CI, 36%-45%) overall, 45% (95% CI, 37%-54%) in eyes with baseline mild NPDR, 40% (95% CI, 32%-49%) with moderate NPDR, 26% (95% CI, 17%-38%) with moderately severe NPDR, and 43% (95% CI, 34%-53%) with severe or very severe NPDR on UWF-color masked images (Figure 2). Stratified by baseline DRSS score, disease worsening occurred in 31% (95% CI, 24%-39%), 37% (95% CI, 27%-48%), 43% (95% CI, 34%-54%), and 56% (95% CI, 47%-65%) among eyes with mild (n = 186), moderate (n = 103), moderately severe (n = 112), and severe/very severe NPDR (n = 134), respectively (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Cumulative Proportion of Disease Worsening Through 4 Years by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) Score on Masked Ultra-Widefield (UWF) Color Images.

Worsening was defined by either a worsening of 2 or more steps on the DRSS within Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of diabetic retinopathy (DR) treatment. Eyes receiving treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. Eyes not meeting the primary outcome or receiving non-DR treatment were censored at the last visit. The cumulative proportion of primary outcome was 45% (95% CI, 37%-54%) in eyes with baseline mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), 40% (95% CI, 32%-49%) with moderate NPDR, 26% (95% CI, 17%-38%) with moderately severe NPDR, and 43% (95% CI, 34%-53%) with severe or very severe NPDR.

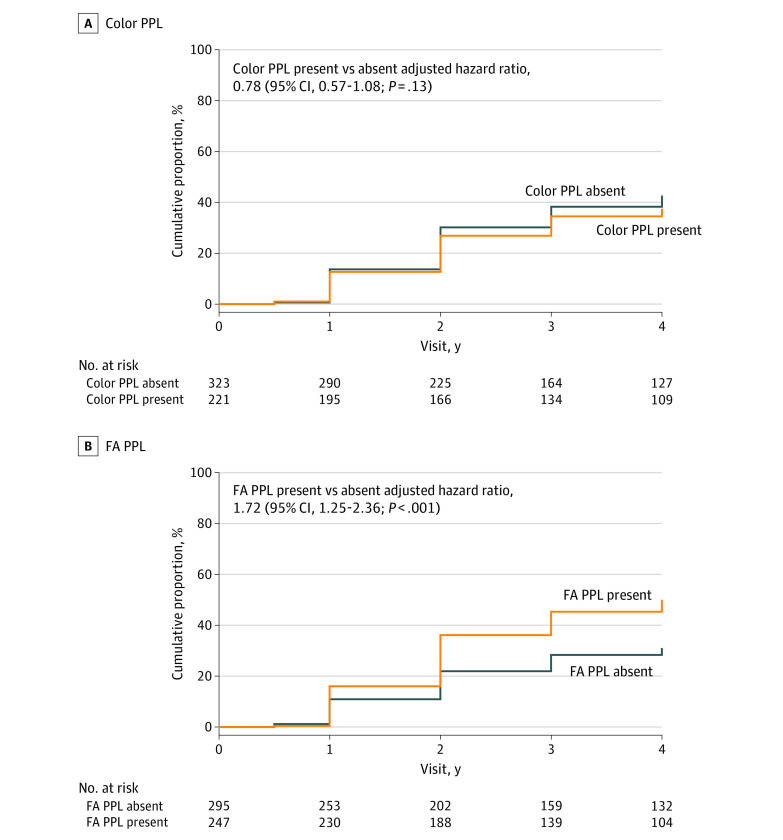

Stratified by baseline PPL status, 38% (95% CI, 31%-45%) of eyes with color PPL and 43% (95% CI, 37%-49%) without color PPL met the primary outcome of disease worsening (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.57-1.08; P = .13) (Figure 3A). The primary outcome rate was 50% (95% CI, 44%-57%) in eyes with FA PPL and 31% (95% CI, 25%-38%) in eyes without FA PPL (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.25-2.36; P < .001) (Figure 3B). Worsening by 2 or more steps on the DRSS was the primary reason for eyes in each group meeting the primary outcome (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Consistent results were seen in the sensitivity analyses evaluating the possible effect of potentially informative censoring of non-DR treatment and loss to follow-up (eTables 7-9 in Supplement 1). Disease worsening over time by color PPL and FA PPL within each DRSS score are shown in eFigures 2 and 3 in Supplement 1. The cumulative proportion of eyes meeting the primary outcome by PPL type and PPL presence by photographic field appears in eTable 10 in Supplement 1. Baseline FA PPL types of H/Ma and IRMA were found to be individually associated with the risk of meeting the primary outcome over time.

Figure 3. Cumulative Proportion of Disease Worsening Through 4 Years.

Worsening was defined by either a worsening of 2 or more steps on the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) within Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) fields on masked ultra-widefield (UWF) color images or receipt of diabetic retinopathy (DR) treatment. Eyes receiving treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. Eyes not meeting the primary outcome or receiving non-DR treatment were censored at the last visit. The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for baseline DRSS score within the ETDRS fields on UWF-color images and the correlation between the 2 study eyes from the same participant. According to predominantly peripheral lesion (PPL) status on color images at baseline (A), the cumulative proportion for primary outcome of disease worsening was 38% (95% CI, 31%-45%) for eyes with color PPL and 43% (95% CI, 37%-49%) without color PPL. According to PPL status on fluorescein angiography (FA) at baseline (B), the cumulative proportion for primary outcome of disease worsening was 50% (95% CI, 44%-57%) in eyes with FA PPL and 31% (95% CI, 25%-38%) in eyes without FA PPL.

Secondary DR Outcomes

The percentage of eyes developing proliferative DR or receiving DR treatment was 17% (95% CI, 12%-23%) among eyes with color PPL and 26% (95% CI, 21%-32%) among eyes without (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.57-1.44; P = .67) but was higher among eyes with FA PPL than those without (24% vs 20%; HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.05-2.45; P = .03) (eTable 11 in Supplement 1). Development of vitreous hemorrhage or initiation of DR treatment occurred in 10% (95% CI, 6.6%-15%) of eyes with color PPL and 12% (95% CI, 8.8%-17%) of eyes without color PPL (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.67-2.41; P = .45) and in 12% of eyes with FA PPL and 11% of eyes without FA PPL (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.79-2.59; P = .24) (eTable 12 in Supplement 1). Secondary outcomes by each of the secondary risk factors are provided in eTables 11-13 in Supplement 1. Eyes with baseline FA PPL of new vessels elsewhere had an increased rate of development of proliferative DR and DR treatment. Additional exploratory outcomes by baseline PPL status are reported in eTable 14 in Supplement 1.

Discussion

In this multicenter longitudinal 4-year observational study of eyes with NPDR without center-involved DME, risk of DRSS worsening or treatment was not associated with color PPL but was significantly associated with FA PPL, when adjusting for baseline DRSS score. Eyes with FA PPL had a 1.7-fold greater risk of disease worsening over 4 years. Thus, among eyes with NPDR, the presence of PPL identified using UWF-FA imaging appears to be a marker for increased risk of disease worsening that is not detectable using standard ETDRS 7-field photography or UWF-color imaging alone.

The association between PPLs and risk of DR worsening confirms observations made more than 50 years ago during the Airlie House Symposium by Beetham and others42 on the importance of the retinal periphery in accurately determining DR disease activity. Despite the awareness of the importance of peripheral findings as far back as the 1960s, the ETDRS DRSS does not incorporate the presence or severity of DR lesions outside the posterior pole because of technological limitations at that time in imaging the retinal periphery. The current study does not suggest that peripheral lesions are more important than those found in the posterior pole but rather that they add significantly to the risk assessment provided by the DRSS.

Among the eyes in this study, PPLs were a common finding; 41% of eyes by UWF-color and 46% by UWF-FA had at least 1 field with DR lesions located predominantly peripheral to the retinal area visualized by ETDRS photography. The predominant lesions that drive determination of PPL on both color photographs and FA are H/Ma. Although the majority of eyes had concordant determination of PPL on color and FA images, a substantial minority of 36% had disparate gradings for PPL on these 2 imaging modalities. As shown in previous work, the use of UWF-FA identifies substantially more DR lesions than UWF-color.43 UWF-FA identifies 3- to 5-fold more microaneurysms, with 37.5% of eyes having more severe DR on UWF-FA vs UWF-color imaging.43 Data from this cohort suggest that the additional lesions found on UWF-FA may provide a more thorough assessment of disease activity and better ability to determine the likelihood of future worsening and need for treatment.

Not only was the presence of FA PPL strongly associated with greater risk of disease worsening over time in this cohort, but this association was consistently present within DRSS subgroups and with multiple individual PPL types (H/Ma, IRMA and new vessels elsewhere). Increasing retinal nonperfusion has been shown to be associated with presence of FA PPL. A prior report from this cohort of eyes found that approximately 70% of retinal nonperfusion in diabetic eyes is located outside the posterior pole.35 Thus, the appearance of these peripheral lesions may reflect underlying vascular pathology related to peripheral retinal ischemia and nonperfusion.

Although previous studies found an association between color PPL and DRSS worsening, this study did not identify an association between peripheral lesions on color fundus photographs and DR outcomes. In contrast to prior reports, which were single-center investigations, this was a multicenter study across sites in the United States and Canada. In addition, whereas other studies graded DR on a global level for each eye and combined DRSS scores into a simplified scale (eg, categorizing eyes with DRSS level 43 or 47 as moderate NPDR instead of categorizing them into moderate and moderately severe NPDR, respectively),1 DRSS score in this study was determined based on individual lesion-level grading according to the methods established in the ETDRS. An unexpected finding in this study was the lack of a consistent trend for more severe baseline DR on UWF masked color images to be associated with higher risk of DR worsening or need for treatment over time. However, risk of the primary outcome was associated with baseline DRSS score on ETDRS photographs.

Based on these data, findings on UWF-color are not interchangeable with findings on UWF-FA. Future efforts to optimize the predictive potential of the DRSS should consider the incorporation of FA PPL and other FA findings to provide a more accurate assessment of risk for disease worsening in research and clinical settings. This could be particularly important in DR screening programs that do not routinely evaluate the retinal periphery and where accurate risk determination is essential for triage of appropriate care. The predictive benefit of UWF-FA for disease worsening in eyes with NPDR will be balanced against practical considerations of increased health care costs and exposing patients to the small risks associated with FA. However, future advances in noninvasive imaging methods such as optical coherence tomography angiography might eventually be able to recapitulate the key findings of UWF-FA. Additionally, artificial intelligence algorithms might be successful at identifying reliable and reproducible biomarkers on color imaging that reflect the pertinent findings on UWF-FA. Future post hoc analyses of this cohort may also address whether fellow eye information on standard or UWF color imaging enables risk assessment to the level of the UWF-FA in a study eye.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the last year of follow-up was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which hindered the ability of some study participants to comply with study visits. The 4-year follow-up was only 77% (excluding deaths). Second, most UWF images (97.5%) for this study were captured on P200Tx (Optos) imaging devices; subsequent advances in retinal imaging have led to the development of newer UWF technology with improved superior and inferior image capture that also allows imaging of the retinal far periphery with improved resolution.44 The improved peripheral imaging capabilities of currently available UWF imaging devices might favorably affect the identification of color PPL, but it is unknown whether this would substantially change the association of color PPL with the primary outcome of this study. Third, the ability of clinicians to identify peripheral DR lesions or assess a retina for nonperfusion was not assessed in this study. Fourth, the association between FA PPL and visual impairment and the effect on rates of visual loss should FA PPL be overlooked clinically were not directly addressed.

Conclusions

The DRCR Retina Network Protocol AA study provides robust information on the natural history of a contemporary DR cohort followed up over 4 years using UWF imaging. Although no association was identified with color PPL, the presence of FA PPL was associated with a significantly greater risk of ETDRS DRSS worsening or treatment over 4 years independent of DRSS score. These results suggest use of UWF-FA to evaluate retina peripheral to standard ETDRS fields improves the ability to predict disease worsening in NPDR eyes. These findings support use of UWF-FA for future DR staging systems and clinical care to more accurately determine prognosis in NPDR eyes.

eFigure 1. Cumulative proportion of disease worsening (DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment) through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on standard ETDRS fundus photographs

eFigure 2. Stratified Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on UWF-color and color-PPL

eFigure 3. Stratified Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on UWF-color and FA-PPL

eTable 1. Visit Completion Over 4 Years

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Baseline PPL Status

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics by 4-Year Visit Completion

eTable 4. Comparison of Baseline PPL on UWF-Color and UWF-FA Images

eTable 5. Treatment Initiation During Follow-up by Baseline DRSS Level

eTable 6. Initial event for eyes meeting the primary outcome

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by Color-PPL

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by FA-PPL

eTable 9. Receipt of Treatment for Non-DR Conditions or Lost to Follow-up by Baseline Characteristics

eTable 10. Primary Outcome: DR worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 11. Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 12. Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 13. Secondary Outcome: DRSS improvement by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 14. Exploratory Outcomes by Primary PPL Characteristics on UWF-Color and UWF-FA Images

Nonauthor collaborators

References

- 1.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group . Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs—an extension of the modified Airlie House classification: ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):786-806. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group . Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):823-833. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL III, Klein RE, et al. ; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group . Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oishi A, Hidaka J, Yoshimura N. Quantification of the image obtained with a wide-field scanning ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(4):2424-2431. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Sun JK, Noble J, Aiello LM, Aiello LP. Nonmydriatic ultrawide field retinal imaging compared with dilated standard 7-field 35-mm photography and retinal specialist examination for evaluation of diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(3):549-559.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kernt M, Hadi I, Pinter F, et al. Assessment of diabetic retinopathy using nonmydriatic ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Optomap) compared with ETDRS 7-field stereo photography. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2459-2463. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen ML, Broe R, Frydkjaer-Olsen U, et al. Comparison between Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study 7-field retinal photos and non-mydriatic, mydriatic and mydriatic steered widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy for assessment of diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(1):99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiello LP, Odia I, Glassman AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Comparison of Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study standard 7-field imaging with ultrawide-field imaging for determining severity of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(1):65-73. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.4982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashraf M, Shokrollahi S, Salongcay RP, Aiello LP, Silva PS. Diabetic retinopathy and ultrawide field imaging. Semin Ophthalmol. 2020;35(1):56-65. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2020.1729818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wessel MM, Aaker GD, Parlitsis G, Cho M, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Ultra-wide-field angiography improves the detection and classification of diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2012;32(4):785-791. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182278b64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Tolls D, et al. Potential efficiency benefits of nonmydriatic ultrawide field retinal imaging in an ocular telehealth diabetic retinopathy program. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):50-55. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Sun JK, Soliman AZ, Aiello LM, Aiello LP. Peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultrawide field imaging: distribution and potential impact on diabetic retinopathy severity. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2587-2595. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price LD, Au S, Chong NV. Optomap ultrawide field imaging identifies additional retinal abnormalities in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:527-531. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S79448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva PS, Dela Cruz AJ, Ledesma MG, et al. Diabetic retinopathy severity and peripheral lesions are associated with nonperfusion on ultrawide field angiography. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2465-2472. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talks SJ, Manjunath V, Steel DH, Peto T, Taylor R. New vessels detected on wide-field imaging compared to two-field and seven-field imaging: implications for diabetic retinopathy screening image analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(12):1606-1609. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neubauer AS, Kernt M, Haritoglou C, Priglinger SG, Kampik A, Ulbig MW. Nonmydriatic screening for diabetic retinopathy by ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Optomap). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(2):229-235. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0631-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verma A, Alagorie AR, Ramasamy K, et al. ; Indian Retina Research Associates (IRRA) . Distribution of peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultra-wide field fundus imaging in diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(4):725-733. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04607-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sim DA, Keane PA, Rajendram R, et al. Patterns of peripheral retinal and central macula ischemia in diabetic retinopathy as evaluated by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(1):144-153.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver SC, Schwartz SD. Peripheral vessel leakage (PVL): a new angiographic finding in diabetic retinopathy identified with ultra wide-field fluorescein angiography. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(1-2):27-33. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.481239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wessel MM, Nair N, Aaker GD, Ehrlich JR, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Peripheral retinal ischaemia, as evaluated by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography, is associated with diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):694-698. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell JF, Al-Khersan H, Shi Y, et al. Retinal nonperfusion in proliferative diabetic retinopathy before and after panretinal photocoagulation assessed by widefield OCT angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;213:177-185. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couturier A, Rey PA, Erginay A, et al. Widefield OCT-angiography and fluorescein angiography assessments of nonperfusion in diabetic retinopathy and edema treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(12):1685-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pichi F, Smith SD, Abboud EB, et al. Wide-field optical coherence tomography angiography for the detection of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(9):1901-1909. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04773-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagasawa T, Tabuchi H, Masumoto H, et al. Accuracy of diabetic retinopathy staging with a deep convolutional neural network using ultra-wide-field fundus ophthalmoscopy and optical coherence tomography angiography. J Ophthalmol. 2021;2021:6651175. doi: 10.1155/2021/6651175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan W, Wang K, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, et al. Distribution of nonperfusion area on ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography in eyes with diabetic macular edema: DAVE Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;180:110-116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan W, Uji A, Nittala M, et al. Retinal vascular bed area on ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography indicates the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;bjophthalmol-2020-317488. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy S, Hu A, Schwartz SD. Ultra wide field fluorescein angiography guided targeted retinal photocoagulation (TRP). Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24(1):9-14. doi: 10.1080/08820530802519899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel RD, Messner LV, Teitelbaum B, Michel KA, Hariprasad SM. Characterization of ischemic index using ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography in patients with focal and diffuse recalcitrant diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(6):1038-1044.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wykoff CC, Nittala MG, Zhou B, et al. ; Intravitreal Aflibercept for Retinal Nonperfusion in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Study Group . Intravitreal aflibercept for retinal nonperfusion in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: outcomes from the randomized RECOVERY trial. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(12):1076-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholson L, Ramu J, Chan EW, et al. Retinal nonperfusion characteristics on ultra-widefield angiography in eyes with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):626-631. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Querques L, Parravano M, Sacconi R, Rabiolo A, Bandello F, Querques G. Ischemic index changes in diabetic retinopathy after intravitreal dexamethasone implant using ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography: a pilot study. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54(8):769-773. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-1010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin AM, Rusu I, Orlin A, et al. Retinal reperfusion in diabetic retinopathy following treatment with anti-VEGF intravitreal injections. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:193-200. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S118807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaeb Center for Health Research . DRCR.net public website. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://www.drcr.net

- 34.Chalam KV, Bressler SB, Edwards AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Retinal thickness in people with diabetes and minimal or no diabetic retinopathy: Heidelberg Spectralis optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(13):8154-8161. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva PS, Liu D, Glassman AR, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Assessment of fluorescein angiography nonperfusion in eyes with diabetic retinopathy using ultrawide field retinal imaging. Retina. 2022;42(7):1302-1310. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of Martingale-based residuals. Biometrika. 1993;80(3):557-572. doi: 10.1093/biomet/80.3.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchanan AL, Hudgens MG, Cole SR, Lau B, Adimora AA; Women’s Interagency HIV Study . Worth the weight: using inverse probability weighted Cox models in AIDS research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(12):1170-1177. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV Jr, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34(4):541-554. doi: 10.2307/2530374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun JK, Josic K, Melia M, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Conversion of central subfield thickness measurements of diabetic macular edema across Cirrus and Spectralis optical coherence tomography instruments. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2021;10(14):34. doi: 10.1167/tvst.10.14.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bressler SB, Edwards AR, Chalam KV, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Writing Committee . Reproducibility of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography retinal thickness measurements and conversion to equivalent time-domain metrics in diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(9):1113-1122. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg MF, Fine SL; US Public Health Service . Symposium on the treatment of diabetic retinopathy [Public Health Service publication No. 1890]. US Neurological and Sensory Disease Control Program. Published 1969.

- 43.Ashraf M, Shokrollahi S, Pisig AU, et al. Retinal vascular caliber association with nonperfusion and diabetic retinopathy severity depends on vascular caliber measurement location. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(6):571-579. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta A, El-Rami H, Barham R, et al. Effect of phase-plate adjustment on retinal image sharpness and visible retinal area on ultrawide field imaging. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(4):587-591. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0270-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Cumulative proportion of disease worsening (DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment) through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on standard ETDRS fundus photographs

eFigure 2. Stratified Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on UWF-color and color-PPL

eFigure 3. Stratified Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level on UWF-color and FA-PPL

eTable 1. Visit Completion Over 4 Years

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Baseline PPL Status

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics by 4-Year Visit Completion

eTable 4. Comparison of Baseline PPL on UWF-Color and UWF-FA Images

eTable 5. Treatment Initiation During Follow-up by Baseline DRSS Level

eTable 6. Initial event for eyes meeting the primary outcome

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by Color-PPL

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by FA-PPL

eTable 9. Receipt of Treatment for Non-DR Conditions or Lost to Follow-up by Baseline Characteristics

eTable 10. Primary Outcome: DR worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 11. Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 12. Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 13. Secondary Outcome: DRSS improvement by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images through 4 years by baseline DRSS level and PPL characteristics

eTable 14. Exploratory Outcomes by Primary PPL Characteristics on UWF-Color and UWF-FA Images

Nonauthor collaborators