Abstract

Deaths of despair, morbidity and emotional distress continue to rise in the US, largely borne by those without a college degree, the majority of American adults, for many of whom the economy and society are no longer delivering. Concurrently, all-cause mortality in the US is diverging by education in a way not seen in other rich countries. We review the rising prevalence of pain, despair, and suicide among those without a BA. Pain and despair created a baseline demand for opioids, but the escalation of addiction came from pharma and its political enablers. We examine the “politics of despair,” how less-educated people have abandoned and been abandoned by the Democratic Party. While healthier states once voted Republican in presidential elections, now the less-healthy states do. We review deaths during COVID, finding mortality in 2020 replicated existing relative mortality differences between those with and without college degrees.

Keywords: deaths of despair, opioid epidemic, COVID epidemic, politics of despair, educational status [N01.824.196], pain [F02.830.816.444]

INTRODUCTION

Our story is one in which the economy has increasingly come to serve some, but not all, Americans, and where a central division is between those who do or do not have a four-year college degree. While the college wage premium has soared to unprecedented levels, James (2012), Autor, Goldin and Katz (2020), the inequality between these two groups involves much more than money. The college degree has now become “a condition of dignified work and of social esteem” (Sandel 2020, Chapter 4), as well as a matter of life and death, with adult life expectancy rising for the college educated, and falling for the rest, Case & Deaton (2021a).

In our first paper, Case & Deaton (2015), we identified an increase in all-cause mortality among white non-Hispanics (WNHs) between the ages of 45 and 54. For this midlife group, the causes of death that were rising most rapidly were suicides, accidental drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease. The mortality increase between 1999 and 2013 from these three causes was 37 per 100,000, close to the increase in all-cause mortality, 34 per 100,000. This mechanical accounting took no note of changes in other important causes of death, particularly cardiovascular disease, on which more below. We documented that these three causes were also rising quickly for WNHs in every 5-year age group from 30–34 to 60–64. Along with the increase in mortality, we used nationally representative surveys to document an increase in a range of morbidity measures for midlife WNHs between 1997–1999 and 2011–2013; these included self-assessed physical health, neck, facial, joint and sciatic pain, as well as deteriorating measures of mental health (Kessler-6 score, days of poor mental health) and of the ability to handle activities of daily living. Behind the rising mortality there was a deepening ocean of physical and mental distress. A few months later, Case (2015) coined the term “deaths of despair,” as a shorthand for the total of the three causes of death and as a label that captured the self-inflicted component of all three. The descriptive tag resonated with the media, the results of the paper captured the interest of many researchers, and the term is often used now without explicit reference to our work.

American death rates from drugs, alcohol and suicide continue to climb, concentrated among those without a bachelor’s degree (BA). For white non-Hispanics, who were the primary focus of our initial paper, the age-adjusted alcohol-related mortality rate increased by 41 percent between 2013 and 2019 for those aged 25–74 without a BA, the suicide rate climbed by 17 percent, and the drug-related mortality rate increased by a stunning 73 percent. In the 20-teens, deaths of despair also began to rise among Black non-Hispanics (BNHs) and Hispanics without a BA, led by drug-related mortality, which more than doubled between 2013 and 2019; the suicide rate increased by a third for both groups, and alcohol-related mortality rates have risen by 30 percent for BNHs without a BA, and by 24 percent for Hispanics. These statistics are for the period leading up to the COVID epidemic. Unfortunately, if (when) vaccinations control the virus, there is no reason to expect that these deaths of despair among less-educated Americans will decline.

In the original paper, we linked the deaths to the economic and social conditions of less-educated Americans, an argument we developed comprehensively in our book, Case & Deaton (2020). There, we highlighted rising pain and other morbidity, falling real wages, declining attachment to employment, falling religious participation, increasing rates of nonmarital childbearing alongside declining rates of marriage. This “tangle of pathology” (echoing today among WNHs a term used in the 1965 Moynihan report describing similar dysfunctions in Black families half a century ago) was accompanied by a loss of social respect and political voice, while the share and influence of labor, especially less-skilled labor, fell relative to the share and influence of capital. In such a social and economic environment, we see rising despair as fertile ground for abusive self-soothing—through drugs, alcohol, and (perhaps) an excess of unhealthy eating—and, in extreme cases, for suicide. The link between despair and death is contingent on beliefs and customs, and particularly on the activities of unscrupulous drug dealers, both legal and illegal. We see the increasing mortality and declining adult life expectancy of less-educated Americans not only as a catastrophe in its own right but as a powerful indicator that American society is not working for the majority of its population.

In this paper, we update and extend our results, learning from and taking note of (at least some of) what has become an extensive literature—Google currently lists 450,000 hits (Scholar, 4,936 cites) to the terms “deaths of despair” or “diseases of despair”—so it is impossible to absorb more than a small fraction of the commentary. There are some particular problems that come from the original paper having been so widely reported. Errors and misinterpretations in the press that reflect common prejudices about drugs and alcohol became ingrained and ineradicable—white non-Hispanic men and women became white men or rural white men with no mention of women—and have led to academic papers purporting to correct or disagree with our work while actually confirming what we found. Beyond that, we have been criticized for missing important trends that happened after we wrote and which we could not have anticipated. The original paper was written in the summer of 2014, with data only to the end of 2013, before deaths in the Black and Hispanic communities stopped their rapid decline and started rising. Nor could we have claimed that rising deaths of despair up to 2013 were responsible for the three-year decline in life expectancy at birth that ran from 2014 through 2017 (then rising in 2018 and 2019 before falling again in the pandemic). We wrote about the changing patterns of deaths by race and about the importance of other deaths—particularly deaths from cardiovascular disease—in a later paper, Case & Deaton (2017a), and in our book, as did other writers, including a consensus report on rising midlife mortality from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2021), henceforth NASEM (2021), and we pursue those topics further in this paper.

In our book, we developed an account of the rising tide of despair, focusing on declining employment opportunities for those without a BA, especially the fall in “good jobs,” those with a sense of belonging, meaning, purpose and prospects for advancement, aggravated by an ever more expensive healthcare system—more than twice as expensive as other rich countries—a fifth of which is financed by an approximately flat tax on workers in amounts that often make low-skilled workers unemployable. An employer-sponsored individual (family) health plan cost $7,470 ($21,342) in 2020, $3.73 ($10.67) an hour for a 2,000-hour year, money that comes out of wages and take-home pay, Kaiser Family Foundation (2020). We also noted the lack of a comprehensive safety net in the US for those who are neither elderly nor children, both of whom are doing relatively well, see Currie & Schwandt (2018). Both the safety net and the financing of healthcare are radically different in other rich countries where—with a few exceptions—there are few deaths of despair. In line with Young’s (1958) original analysis, and the recent treatment by Sandel (2020), we emphasized the corrosive effects of American meritocracy on the unsuccessful, Young’s “populists”, who have to live with the “meritocratic hubris” of the “well-credentialed” (Young’s “hypocrisy”) and who, as they strive not to blame themselves, believe—with much justification—that society is rigged against them. It was this “toxic mix of hubris and resentment that propelled Trump to power,” Sandel (2020, Prologue).

In this paper, we look beyond deaths of despair to all-cause mortality, and document how mortality has risen for those without a four-year degree while continuing to fall for those who have one, something that was true after 2010 up to the COVID pandemic. While deaths of despair are part of this story, another important part is what has been happening to deaths from cardiovascular disease, whose decline was the driving force behind rising life expectancy in the last quarter of the 20th century, but where declines have leveled off, even for those with the degree, while reversing for those without. We also give attention to the mortality experiences of different racial and educational groups before and during the pandemic. In some cases, the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequalities, but that was not true in general. Finally, we document what is currently known about deaths of despair during the pandemic.

RISING DESPAIR, RISING PAIN, AND DETERIORATING MENTAL HEALTH

A key element of our account is that despair is rising, especially among Americans without a bachelor’s degree. Despair is a concept in common use, not a well-defined diagnostic category, let alone one with a clinically validated measure. As a result, it does not appear in national surveys in a way that allows direct documentation. Pain and mental health are perhaps more straightforward, but they necessarily rely on self-reported information. Researchers across many disciplines have picked up the challenge of documenting whether, and to what extent, pain and despair have been rising in the US, and there is now a broad consensus that both have been increasing for decades, especially among less-educated Americans.

Perhaps the best and least controversial measure of despair is the suicide rate itself, which rose by 36 percent from 1999 to 2019 among those aged 25–74 (age-adjusted). It is currently at its highest level since 1938, United States Congress Joint Economic Committee (2019), and its continued rise in the US stands in contrast to other countries as well as to the world as a whole, where suicide rates have been falling since 2000, Ritchie et al. (2021). Contrary to what was long believed, suicide rates in the US are higher among those with less education. While the age-adjusted suicide rate almost doubled from 1992 to 2019 among WNHs ages 25–74 without a BA, increasing from 17.6 to 31.1 per 100,000, there was almost no increase among those with the degree. Suicide rates were declining between 1990 and 2010 for less-educated Hispanics and BNHs, but rates began to rise after 2010, increasing from 7 to 10 per 100,000 (age-adjusted 25–74) between 2010 and 2019.

Pain is a key to despair, because of its direct effects, and because it is a well-established correlate of suicide, Goldsmith et al. (2002), Case & Deaton (2017b). NASEM (2021) reviewed several studies that found rising levels of pain in the US. These include our 2015 paper, which documented increases in a range of specific pains (listed in the introduction), as well as Nahin et al. (2019) who used the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to find that the proportion of adults reporting painful health conditions increased from 32.9 percent in 1997–98 to 41.0 percent in 2013–14, and Zajacova et al. (2021) who find “a large escalation in pain prevalence among adults” (NASEM 2021, p. 254) from 1997–98 to 2013–14 in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Zimmer & Zajacova (2020) also document the “increasing pain prevalence in older Americans” from 1992 to 2014 in the Health and Retirement Study (p. 436). These patterns are consistent with those presented in a 2011 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report that found, using successive waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999–2000 to 2003–04, that “[i]n nearly every demographic group, there has been a steady increase in reporting of pain prevalence across these surveys.” NASEM (2011, p. 64). Case et al (2020) find, in both NHIS and Gallup data for the US, but not in data from Europe, that pain is lower among the elderly than among those in midlife when viewed in any given year, a biological improbability that is resolved by examining successive birth cohorts to show that those currently in midlife in the US have had higher pain levels throughout their lives than did the now elderly. Within a birth cohort, pain rises with age into old age, and pain rises between successive birth cohorts. These results echo those of Grol-Prokopczyk (2017) using the Health and Retirement Study.

NASEM (2011) writes in its summary that “[p]ain affects millions of Americans; contributes greatly to national rates of morbidity, mortality, and disability; and is rising in prevalence” (our italics), (p. 5). We have been unable to find any study that documents falling levels of pain.1 We therefore find it extraordinary that NASEM (2021, p. 253) should write, “The level of physical pain among adults in the United States is high and may be rising.” (our italics). Some commentators dismiss the increase in pain altogether. In an interview with the American Enterprise Institute, Edward Glaeser claims “there was no massive increase in physical pain over this time period. Joint pain, significant pain has been essentially flat,” Pethokoukis and Glaeser (2021). We believe that such statements, like NASEM’s (2021) conclusion, are false. Pain prevalence has been rising in the US at least since the early 1990s, especially among less educated Americans.

What about mental health? Increases in suicide are a stark measure of the erosion of mental health among those without a college degree. Consistent with this, the prevalence of serious mental distress among less-educated white non-Hispanics rose steadily from 1997 to 2017, measured in the NHIS using the Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale, Case & Deaton (2020). Blanchflower & Oswald (2020) construct a measure of “extreme distress” based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Respondents are asked to reflect on their mental health: “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Blanchflower & Oswald focus on the fraction of the population who reported such problems in all 30 of the last 30 days. In 1993, just 4 percent of people aged 25–74 without a BA reported such distress, but the figure had risen to 8 percent by 2019. Among those with a BA, distress rose too, but only from 2 percent to 3 percent.

Other measures of mental distress are based on life-satisfaction or life evaluation questions. One such is the fraction of the population who report that they are “not too happy” in the General Social Survey (GSS). From 1972 to 1990, this fraction showed no clear trend, but has trended upwards sharply since about 1990, and much more so among those with less education, Blanchflower & Oswald (2004, 2019). The United States Congress Joint Economic Committee (2019) also documents a decline in life-satisfaction in the GSS, and in Pew Surveys, although not in Gallup survey data. Our own calculations using Gallup surveys confirm a lack of trend from 2010 through 2017 (a short period, but longer periods have problems with changing questions and question-order effects, see Deaton (2012)). Goldman et al. (2018) examine a battery of psychological measures asked in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) longitudinal survey carried out in 1995–6 and 2011–14 among 4627 white non-Hispanics ages 24–76. They report that life satisfaction worsened over this period in MIDUS, as did measures of negative affect, positive affect and psychological wellbeing. Once again, the decline in mental health is more severe for those of low socioeconomic status. See also Graham (2017) for a broader documentation of widening disparities in wellbeing by education; she also documents that—except for the elderly, and for BNHs—people generally expected their lives to be worse in 5 years than they are today. These measures are not well understood and cannot be interpreted as rational forecasts, Schwandt (2016), Deaton (2018), but Graham’s view that they show lack of hope is a reasonable one.

All of the life-satisfaction questions have problems—a short sample for Gallup, small samples for GSS, and selective attrition between rounds in the MIDUS, Radler & Ryff (2010). Across countries, there is no correlation between life evaluation and suicide, Ritchie et al (2021), and there is evidence in the Gallup data that population averages of life evaluation questions, though sensitive to short run events, do not adequately reflect long-run trends, perhaps through adaptation, see again Deaton (2012). Case & Deaton (2017b) use Gallup data to examine the extent to which life-satisfaction is a good measure of mental distress: they write in their Abstract

Differences in suicides between men and women, between Hispanics, blacks, and whites, between age groups for men, between countries or US states, between calendar years, and between days of the week, do not match differences in life evaluation. By contrast, reports of physical pain are strongly predictive of suicide in many contexts.

If we accept, as we believe we must, that suicide is the ultimate indicator of mental distress and despair, then life satisfaction questions are unlikely to provide an adequate marker for despair. By contrast, the Kessler-6 measure and the measure constructed by Blanchflower & Oswald allow measurement over large samples taken over longer periods of time and focus directly on mental distress.

The evidence on suicide, on pain, and on mental distress show that despair has been rising in the US for twenty years or more, especially among those without a college degree; it is key evidence that the American economy and society is not delivering for them.

DESPAIR AND THE DEMAND AND SUPPLY OF OPIOIDS

Of the three causes of death that later became known as deaths of despair, it has been clear since our first paper that the largest component part of the total (plurality) is overdose deaths, and that an ever-larger share of the increase since the mid-1990s was drug-related. Some critics, including Masters et al (2018), Currie & Schwandt (2020) and Ruhm (2021), have contended that “deaths of despair” are not much more than an opioid epidemic, one of many that have recurrently plagued nations throughout history, and that despair, if it exists, is a sideshow. In the current epidemic, they argue, the villains are the pharma companies, the distributors, and their enablers in Congress, who swamped the country with largely unnecessary painkillers, leading in stages to an epidemic of illegal street drugs. This is the supply story of overdose deaths, and it is one with which we largely agree. Yet some have interpreted our work as arguing that rising despair caused the opioid deaths, “that these deaths are the result of an economy that left Americans behind and feeling trapped. In their desperation, they reached to oxycontin and codeine to cope with the insecurity of a global economy.” Pethokoukis (2021). The contrast here is between a supply driven opioid epidemic (unscrupulous pharma followed by deadly street drugs) and a demand driven epidemic, propelled by despair, in which pharma companies did little more than meet rising demand.

Many past epidemics of opioid addiction have happened during times of social or economic disintegration. The last major epidemic in the US was during and after the Civil War, see for example Macy (2018), though we might also count the heavy use of drugs among American troops in Vietnam, which led to little or no addiction when the soldiers returned home to a normal economic and social environment, Robbins (1993). The Opium Wars in China, which haunt the country to this day, were a flagrant attempt by the British opium merchants, Jardine and Matheson, disgracefully supported by the British parliament, to force the Qing emperor to allow them to get rich by selling the drug in China. But the wars would not have happened if the Qing Empire had not been in what eventually turned into terminal decay. Weak dysfunctional societies, like injured or dying animals, attract vultures who swoop in to scavenge. No one today would excuse Jardine and Matheson, nor Prime Minister Melbourne for sending in the navy, but it is impossible to understand what happened without understanding the dysfunction of the Empire, Lovell (2014), Platt (2018). When opioid overdoses rose rapidly in the US in the late 1990s, the vultures were the pharma companies and their political enablers but, by that time, less-educated Americans had suffered a quarter-century of job loss, wage decline, union loss, rising morbidity, failing marriages, and much more.

What caused the Opium Wars? What caused America’s opioid epidemic? Like many such questions in history and social science, there does not have to be a single or even fundamental cause. A car crashed because an intoxicated driver on an icy road did not see the approaching vehicle on the wrong side of the road; the crash would not have happened without all three circumstances. There is no unique cause, nor even a fundamental cause. We do not believe that the opioid epidemic in the US would have happened to the extent that it did without the ocean of pain and distress among less-educated Americans. The pharma companies targeted places that were hurting, where jobs had been lost, and where pain was prevalent. But it was the pharma companies and distributors who exploited the situation; indeed, this is what Cutler & Glaeser (2021) find, that the epidemic was worse in places with high levels of initial pain. That is the initial effect of “demand,” which was hugely amplified by addiction and by profit-seeking suppliers, further adding to pain and distress, which explains why almost all the increase in deaths were among those without a BA. The minds and bodies of educated Americans can also experience addiction, but they were protected from a similar epidemic by living in an economy and a society that was working for them. There is nothing in our work that supports the idea that rising pain justified the increased prescription of opioids, or that excuses the criminality of the suppliers. But those who argue that deaths of despair are just an opioid epidemic need to explain why those with a four-year degree are exempt.

As far as policy is concerned, stopping the distribution of drugs is an obvious immediate priority, Currie & Schwandt (2020). But even if that immensely difficult task were to be achieved, it would not eliminate the underlying despair, the suicides, and the abuse of alcohol. The denial of rising despair and the argument that deaths of despair are part of an opioid epidemic, akin to a biological epidemic that recurs from time to time, constructs an apologia for contemporary American capitalism in which all is well apart from a few bad pharma companies. Such an interpretation ignores the upsurge of pain, mental distress, and suicide, and the fact that educated Americans are exempt. The failure of contemporary capitalism is much broader and will not be cured by reining in the perpetrators of the opioid epidemic.

The activities of the drug industry have also shaped geographical differences in the patterns of deaths, even if the broad upstream risk factors are similar. In the face of despair, different people with different beliefs and backgrounds will respond differently, so that, for example, Tennesseans—a largely dry state—and Mormons in Utah will not abuse alcohol, though they are not protected against drug overdoses. Men tend to kill themselves with guns, and women with pills, but that does not cause us to deny that both are suicides. We do not therefore accept the argument by Ruhm (2021) and Simon & Masters (2021) that different geographical patterns of the details of deaths of despair disprove a common underlying cause, see also the similar defense of our interpretation by Siddiqi & Sod-Erdene (2021). Contingent factors, including beliefs and customs, as well as the activities of pharma and distributors, will be important in translating despair into death.

MORTALITY AND EDUCATION

A good way to assess the relationship between education, race/ethnicity, sex, and mortality in the US is to track the age-adjusted mortality rate of adults ages 25 to 74. This is a convenient measure that summarizes changes in mortality while holding the structure of the population constant over time. By age 25, most adults have completed their formal education; whether or not someone will graduate from college is not knowable at birth.

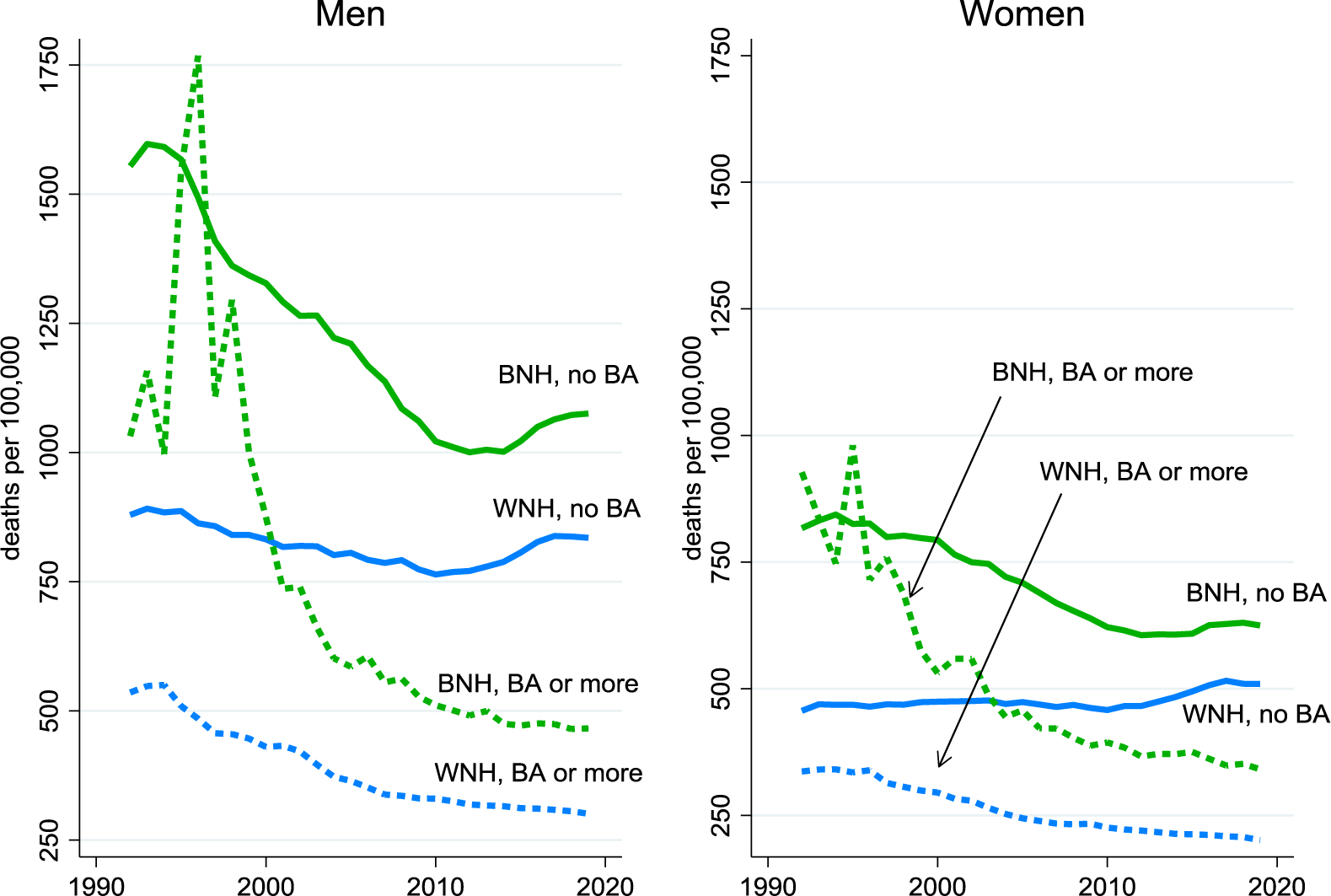

Mortality rates for the period 1992 to 2019 are presented in Figure 1, with men in the left panel and women in the right, for BNHs (in green) and WNHs (in blue), separately for those with and without a four-year degree.

Figure 1.

All-cause mortality rates by race, sex and education, age-adjusted 25–74

Those with a BA have lower mortality rates than those without, and the gaps between those with and without have widened markedly since 1992, something that is true for both Blacks and whites. As educational gaps have widened, racial gaps have narrowed, so that Blacks with a BA are now closer to whites with a BA than they are to Blacks without a BA, the opposite of the situation in 1992 and up to around 2000. Even so, Blacks continue to have higher mortality rates than whites—as has been true as far back as data have been collected—though the college degree is becoming more important relative to race. Non-college educated whites, particularly non-college educated white women, have done particularly badly in recent decades; the relatively poor outcomes for women come from the fact that progress against mortality from cardiovascular disease, which was the main driver of mortality decline for many years, relatively favored men because men were (and are) more likely to die from it.

Our finding of widening mortality gaps by education for Black men and women over the period 1992 to 2019 stands in contrast to the conclusion drawn in NASEM (2021), who report that “[a]lthough less-educated working-age Blacks also experienced higher mortality relative to working-age Blacks with more education, this disadvantage remained largely stable between 1990 and 2017” (NASEM 2021, p. 86).

The educational divide in Figure 1 is driven mostly by the educational divide in deaths of despair together with what has happened to cardiovascular disease. Really bad things began to happen after 2010, when all-cause mortality rates started to rise for those without a BA, though they continued to fall for those with a college degree, albeit more slowly. The marked progress made between the early 1990s and 2010 in closing the Black-white mortality gap stalled in the early 20-teens, particularly for men. This is when the opioid epidemic moved into African American and Hispanic communities, around the time that physicians pulled back on legal prescriptions of painkilling opioids, igniting a secondary epidemic of illegal street drugs. Beginning with heroin, then fentanyl, then fentanyl mixed with cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamines, these deadly combinations spread irrespective of race, but with the BA continuing to act as a talisman against overdose deaths.

The spread of death to the non-white communities is mostly from drug overdoses but not exclusively so, as we have seen with suicides. Deaths of despair among BNHs and among Hispanics began to rise after 2010; like those for WNHs, the increases are largely confined to those without a four-year college degree. About three-quarters of the increase for BNHs and Hispanics without a BA is accounted for by drug overdoses.

Our analysis using death certificates finds the (age-adjusted) drug-overdose mortality rate of Black non-Hispanics ages 25–64 without a BA was approximately four times the rate of that with a BA from the early 1990s to the early 20-teens. This stands in contrast to the conclusion drawn by NASEM (2021), which states that “the committee’s review of the literature showed that there was no difference in drug poisoning mortality by educational attainment among Blacks” (NASEM 2021, p. 5). The arrival of street fentanyl in 2013 led to a drug mortality rate among less-educated Blacks that was seven times greater than that among more-educated Blacks in 2019.

Linking education and mortality: alternative approaches and findings

Central to our story are the findings that both deaths of despair and deaths from all causes (as in Figure 1 above) behave differently according to education, with a particularly sharp break between those with and without the four-year degree.

We link education and death using the education levels reported on the death certificates—which also have information on cause of death, place, time, age, sex, race and ethnicity. This procedure has been followed by in a number of important earlier studies including Jemal et al (2008), Meara et al (2008), Olshansky et al (2012), Sasson (2016a, 2016b) and Sasson & Hayward (2019), all of which have documented widening inequalities between educational groups. Even so, the method is not without its critics, including of our work, Ruhm (2021) and NASEM (2021, p. 3), and the latter chose not to use education in their own calculations. Other prominent discussions of recent mortality in the US, e.g., Woolf et al. (2018) and Woolf & Schoomaker (2019) also ignore differential trends by education in spite of what we see as their central importance, not only in understanding mortality, but in linking mortality to its social determinants, particularly labor markets and social and familial structure.

The main concern is the accuracy of education reports on the death certificates; the person who (possibly) best knows his or her education is in no position to report, and the funeral director may not be well-informed. (There are similar concerns for the reporting of race and ethnicity.) The worst misclassifications appear to involve whether people graduated from high school, with fewer misclassifications for BA status, Rostron et al. (2010). In addition, after 2003, there was a gradual change that replaced years of education with highest grade attained. Our work uses the binary outcome of BA or not (or 16 or more years of education), so that misclassification will attenuate the differences in mortality rates between the two groups, and cannot create such differences where they do not exist. Other researchers, notably Montez et al. (2011), Montez & Zajacova (2013) and Hendi (2017) have used the mortality follow-up to the National Health Interview Survey, in which respondents to the surveys are matched to death records. These studies also found widening educational inequalities in mortality.

These follow-up methods can take advantage of the substantial amount of health information in the baseline survey, and can use the respondents’ own report of education; unfortunately, these too are error prone. Our calculations using the Current Population Survey show the fraction of people reporting a BA tends to increase with age within a birth cohort, by about 1.3 percentage points each decade of age after age 35, an increase too large to be explained by selective mortality. Beyond that, the NHIS and other household or individual surveys exclude the institutionalized population, the homeless as well as those in the military, in prison, or in elder-care facilities, so that mortality is understated and life expectancy overstated. Perhaps most seriously for our current purposes, because the original surveys and their follow-ups are small, they can only track broad mortality patterns, not the specific causes of death included in deaths of despair.

Small samples are not a problem when there are complete administrative data, as in Chetty et al. (2016), who use 1.4 billion tax records merged into the mortality data; this work has revealed important and previously unknown patterns of mortality and income across space, but cannot provide information on magnitudes not known to the tax authorities, such as race or education. Two recent studies overcome this difficulty as well as the small sample problem. Miller et al. (2021) and Olfson et al. (2021) merge into the death records the respondents from the American Community Survey (ACS), which has several million respondents each year. Olfson et al. (2021) focus explicitly on deaths of despair, and follow 3.5 million respondents in the 2008 ACS from 2008 through 2015. We can use their results, not only to check our own findings using education information that is self-reported, but to extend them based on the much richer sociodemographic information at baseline. On education in particular, the college degree is strongly protective against a death of despair, as well as for each of suicide, poisoning (drug overdose), and liver disease separately. As in our book, it is the BA that makes the difference, with similar higher hazards for high school or less and for some college; some college helps, but outcomes are closer to those with a high-school degree than to those with a four-year college degree.

Olfson et al. (2021) also document at the individual level the hazards associated with factors that we have shown are trending adversely for those without a college degree, not being employed (which includes the increasing number of those not looking for work, who are excluded from the number of unemployed), marital status other than being married, functional disabilities of various kinds, and low income. In our work, we have documented the deaths, as well as the increase in the adverse factors; Olfson et al. (2021) fill in the missing link by showing that individuals experiencing these setbacks are indeed more likely to die a death of despair. Given that the prevalence of adverse factors is increasing, the findings predict an increase in deaths of despair. Olfson et al. also document other precursors, e.g., military service is a risk factor for suicide, though not for other deaths of despair. With some differences, there is a broad similarity of risk factors across the three kinds of death, particularly not having a college degree, not being currently married, having low income, and being male. One important factor that has been much misinterpreted in the literature is rurality. Rural residence is protective against drug deaths and liver disease, but is a risk factor for suicide, presumably because of the long-standing and well-researched additional suicide risk in places with low population density.

A final comment on the measurement of education: in most rich countries, including the US, educational levels have been rising over time. According to the US Bureau of the Census (2021), in 2019, 36 percent of Americans aged 25 or older had completed at least four years of college, compared with 26 percent in 2000, and 11 percent in 1970. At the other end of the scale, only 10 percent of American adults did not have a high school diploma in 2019, compared with 16 percent in 2000, and 45 percent in 1970. Clearly, the people with a BA today are different from those with a BA in 1970. Demographic change is particularly dramatic for those without a high-school degree. When it was normal not to finish high school, many talented and ambitious people did not do so, whereas today, those not graduating are more negatively selected, not only on ability, but likely on health. By the same token, college graduates today may be less selected on ability or social background than used to be the case. This kind of selection means that, when we look at health outcomes for different educational groups, selection effects are part, perhaps an important part, of what we are observing—certainly so for those without a high school degree.

A useful analogy here is with the longstanding practice in labor economics of calculating the college wage premium, the percentage by which wages of college graduates exceed those of non-graduates. Selection works in the same way for these measures, and the effects of selection are present in estimates of the premium. But labor economists do not do what some papers in the health literature have recently done, which is convert educational qualifications into a percentile in the distribution of schooling, and then study the link with mortality, not by qualification, but by percentile in the education distribution. See Geronimus et al. (2019), Leive & Ruhm (2020) and, especially, Novosad et al. (2020), whose innovative statistical analysis illustrates the technical problems of working with a measure that is not well-defined for many people. To our way of thinking, the conversion solves no problems, and creates new ones, well-illustrated by Novosad et al. (2020). We understand a good deal about what a BA or other qualifications bring in terms of jobs and social status, but nothing at all about what a percentile brings, a measure that most people (or their employers) neither know nor have an interest in. And just as a fixed qualification corresponds to a shifting fraction of the population, so does a fixed percentile correspond to an ever-changing level of qualification. Both qualification and ability, and selection on ability, matter, and there is little choice but to deal with them, as is done in the literature on education and earnings.

Education and mortality in other rich countries

The phenomenon of rising mortality among less-well educated Americans has had no parallel in Western Europe. While the analysis of deaths of despair and of all-cause mortality by education is more difficult in other rich countries because education is typically not recorded at death, several countries link mortality to samples from censuses or other administrative records where education is recorded. The linked data can be used to study differences in all-cause mortality by education, or in major causes of death. Excellent work on education and mortality, both all-cause and important specific causes, in Europe has been carried out by Johan Mackenbach and collaborators, particularly Mackenbach et al. (2016) for 12 European countries or regions, and Mackenbach et al. (2018) for 27 European Countries. Mackenbach and his coauthors divide education qualifications into three (sometimes two) categories, low, medium and high, using the harmonized standards of the International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED (1997). These standards are reasonable, although they still face the challenge that there may be critical cutoffs that fulfil the function of the BA in the US, but which differ from country to country, and are not captured by three ISCED-based levels. Even so, these studies are invaluable, and much can be learned from them. As is to be expected, those with more education have lower mortality rates. In most of the countries, age-adjusted mortality rates fell from c1980 to 2014 for all three education levels, and in many countries fell by more for less-educated than for more educated people. But because the larger decreases for the less-educated started from higher baseline mortality rates, the percentage declines in mortality were smaller for the less educated group—a widening in relative mortality inequality while absolute mortality inequality decreased.

These European mortality patterns are different from, and much more benign than, those in the US, presented in Figure 1, where mortality rates for those with and without a BA are going in different directions. Mackenbach and his collaborators do not find this divergence in any European country in the 21st century, but there are six Eastern European countries—Hungary, Czechia, Poland, Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia—where, prior to 2000, mortality rates were rising for less-educated men while falling for more-educated men. (The same was true for women in two of these countries.)

It is an extraordinary condemnation of health in the US that its post-2010 mortality patterns show parallels with the events in the post-transition countries of Eastern Europe. Those countries too had very high rates of death from alcohol, suicide, and drug overdoses, which a large and contested literature attributes to social and economic collapse, see for example Stuckler et al. (2009), Cornia & Paniccià (2000).

A POLITICS OF DESPAIR

If the majority of Americans are failing to thrive while a minority prospers, why does the democratic process not work to improve their material and health outcomes? The question is important, not just instrumentally, but substantively, because living in a functioning democracy is good in and of itself, and the lack of effective political voice is one reason to despair. One answer comes from Woolhandler et al. (2021) in a Lancet Commission report on public policy and health in the Trump era. They describe a negative feedback loop in which “the neoliberal policies that inflicted economic hardship and worsened health” did not, as might have been expected in a well-functioning democratic state, generate a political demand for better safety nets and health provision, because less-educated whites see such policies as favoring minorities at their expense. Instead, the authors argue, less-educated whites vote for conservative candidates who oppose such programs, candidates who are suspicious of government in general and whose wealthy backers oppose the taxes necessary to pay for such programs. Blacks and more educated whites react in the opposite direction, widening political polarization, which on net favors the right and provides an opening for populist politicians such as Donald Trump. These ideas echo the literature on the loss of white-privilege to minorities, particularly African Americans, and its corrosive effects on white working-class self-respect, health, and voting preferences, Cherlin (2014), Wilkerson (2020), Siddiqui et al. (2019), Metzl (2019). Indeed, McCarthy (2017) argues that the unwillingness of whites to finance healthcare for Blacks was an important reason why the US, unlike other rich countries, did not build a national health system after World War 2.

This account matches much of the data. Immediately after the Presidential election of 2016, several studies noted correlations between deaths of despair, changes in life expectancy, and the Republican share of the vote, Monnat (2016) and Bor (2017). Bor finds a correlation of (minus) −0.67 across counties between changes in life expectancy from 1980 and 2014 and the share of each county’s vote going to Trump. There is a similar cross-county correlation between Trump’s vote share and the fraction of each county’s population that is non-Hispanic white without a college degree, and with a composite of indicators of ill-health, The Economist (2016).

Here we track what has happened to education, health, and voting patterns as the economy turned against the white working class. We look across states, where the data on life expectancy is much more precise than at the county level; many counties do not have large enough populations to permit estimates of life expectancy without smoothing or imputation. The changing cross-state relationship between adult life expectancy (life expectancy at 25) and the fraction of the population with a four-year college degree is a good starting point. In 1960, there were few BAs in any state, and the fraction of the state with a college degree was almost uncorrelated with state adult life expectancy. Over time, the fraction of BAs grew, as did the dispersion of education across states, and the fraction of adults with a BA became more highly correlated with adult life expectancy; the interstate correlation increased from 0.05 in 1960 to 0.17 in 1980, 0.33 in 2000, and 0.47 in 2018 (authors calculations from IPUMS data, Ruggles et al (2021) and US Mortality Database (2021)). Education is likely important for state life expectancy, but more-educated states are also richer, have better health-related behaviors, higher tobacco prices, and more complete access to Medicaid, Couillard et al. (2021).

The economy began to turn against the white working class around 1970. Real wages began to decline for workers without a BA, and there was a long slow decline—interrupted but never fully restored during economic booms—of job opportunities for less-educated men, much of it driven by the decline in employment in American manufacturing. Globalization was important, though less important than automation, as was the relentless increase in the costs of healthcare, much of which is paid for through what is essentially a head tax on wages. In our book, we link this decline of work and of earnings to a range of other social and economic dysfunctions and ultimately to morbidity and mortality. Unionization, which had reached its peak in the 1950s, declined to the point where today only 6.3 percent of private sector workers are unionized. Unions raised wages for their members, and to a lesser extent for non-members, provided workers some control over working conditions, and gave them political power both locally and nationally because unions worked with the Democrats to support working-class concerns.

Since the 1970s, there has been a slow rolling and still ongoing divorce between Democrats and the white working class, a divorce that is central to the politics of despair. Especially after the catastrophic 1968 Democratic convention, the party slowly oriented itself away from its traditional working-class and union base towards what it is today, a coalition of minorities and educated professionals. This process is still ongoing, so that, for example, the voters in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin that tipped the 2016 election to Trump had already moved away from Obama in 2012 compared with 2008, Monnat & Brown (2017). As jobs were lost, less-educated workers moved to the right, especially but not only in the south, a move that was hastened by the Democratic Party’s embrace of Civil Rights, Kuziemko & Washington (2018).

Slow moving trends make it difficult to attribute causality. Autor et al. (2020) look at the political consequences of the China shock, the loss of jobs that followed China’s admission into the World Trade Organization, which provided a clearly-demarcated exogenous change in the labor market. They document rising political polarization among both voters and donors from 2000 to 2016, but with the move to the left by progressives not large enough to offset the move to the right, nor the loss of the middle, so that moderate Democrats in Congress were on net replaced by right-wing Republicans. As Autor et al. (2020) emphasize, their focus on China does not mean the analysis is confined to job loss attributable to China, but it provides a local lens on a much more widespread phenomenon. In 2016, in particular, “many less-educated American saw Donald Trump as a strong leader” and saw him as “their hero,” Achen and Bartels (2016, Afterword, p. 335), and many voted for him who had not voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, perhaps expressing a long-standing resentment over loss of jobs, status, and dignity.

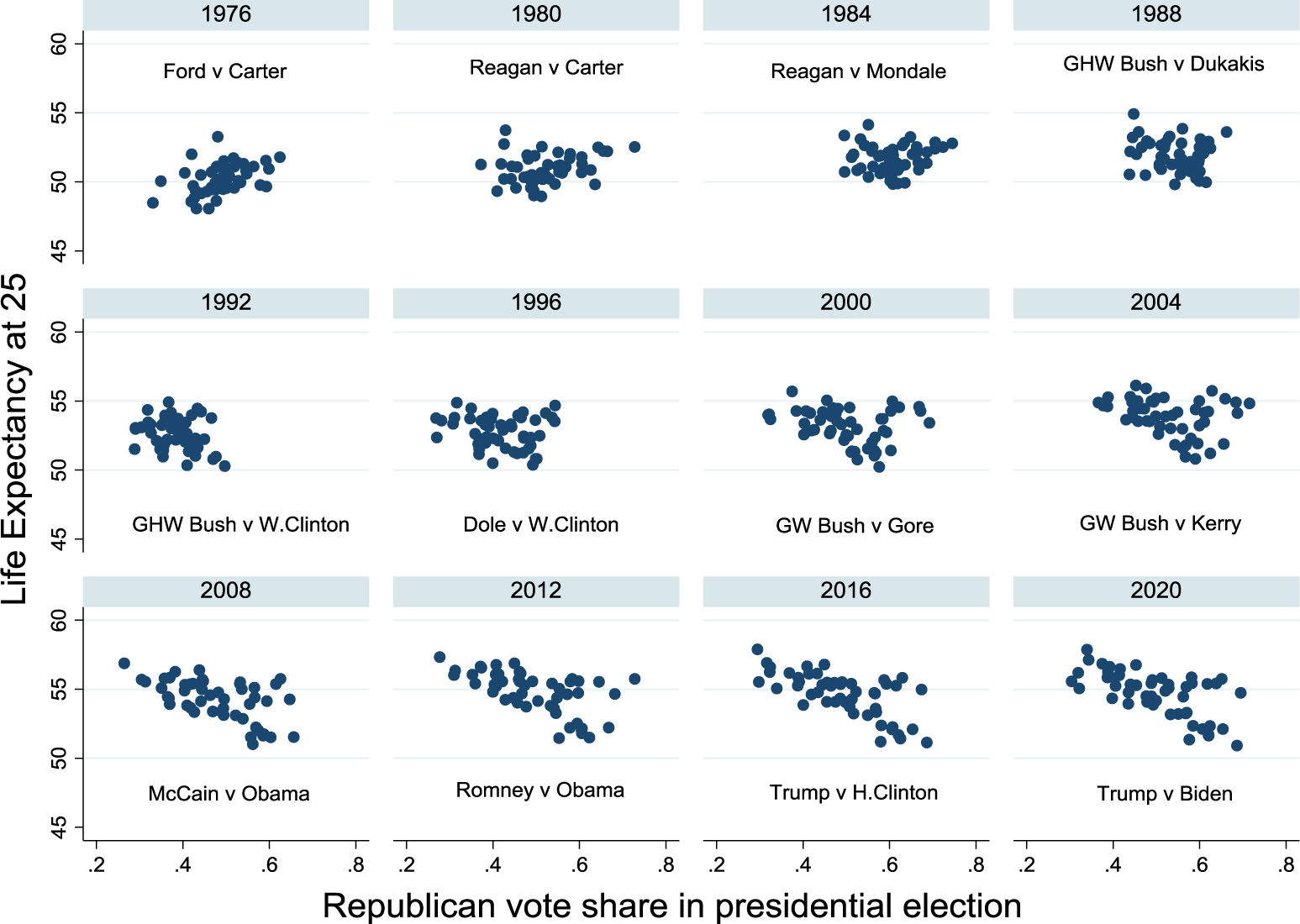

States with a higher fraction of more educated citizens are states with higher life expectancy, so the divorce between the Democratic party and the white working class has meant that red states are now less healthy than blue states, a reversal of what was once the case. Figure 2 shows what happened in each Presidential election since 1976, and plots the share of the vote going to the Republican candidate against adult life expectancy, data from MIT Election Data Science Lab (2021) and US Mortality Database (2021).

Figure 2.

Adult life expectancy and share of presidential votes for Republican

The interstate correlation goes from (positive) +0.42 when Gerald Ford was the Republican candidate—the healthier states voted for Ford and against Carter—to (negative) –0.69 in 2016, and –0.64 in 2020 (using 2018 estimates of adult life expectancy). The least healthy states voted for Trump and against Biden. (These correlations are similar for life expectancy at birth.) These recent votes are surely not for a President who will dismantle safety nets but against a Democratic party that represents an alliance of minorities who working-class whites see as displacing them and challenging their once solid if unperceived privilege, and an educated elite that has benefited from globalization and from a soaring stock market based on rising profitability of the firms that have increasingly denied them jobs.

Vaccinations to protect against COVID-19 are a current example of the association between ill-health and GOP voters. By September 2021, the average fully-vaccinated rate in counties that voted for Trump was 39.9 percent, compared with 52.8 percent among those who voted for Biden, Kaiser Family Foundation (2021). We currently (August 2021) have the extraordinary situation where leaders of one of America’s two main parties are working against mask and vaccination mandates, measures that could save the lives of their supporters. Less-educated Americans have learned not to trust Washington or other important institutions, including science, putting themselves (and their neighbors) in grave danger.

EPIDEMICS COLLIDE: DEATHS OF DESPAIR AND THE COVID PANDEMIC

The interaction of the epidemic we describe—of deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide—with the COVID-19 pandemic raises many important questions; here, we discuss two. First, did the economic and psychological consequences of the pandemic—mass job loss, anxiety, and depression—lead to a spike in deaths of despair? The obvious reference here is the large literature that positively links unemployment and suicide, given that between February and May 2020 more than 20 million non-farm jobs were lost and the official unemployment rate rose from 3.5 percent to 13.3 percent. Anxiety and unemployment may also have increased the demand for drugs and alcohol and limited the availability of treatment. Second, how did the educational pattern of mortality play out during the pandemic? The obvious presupposition is that, because less-educated workers are more likely to be in frontline jobs, and because more educated workers could continue their employment remotely and safely, mortality rates for the less-educated should rise relative to those for the more educated.

At the time of writing, the pandemic is less than two years old, and the data will be incomplete and provisional for some time. There was indeed an increase in drug overdoses early in the pandemic, but drug deaths were increasing prior to the pandemic, and they fell somewhat after May 2020. Suicides fell in 2020 compared with 2019, and we currently know little about alcohol deaths. Mortality rates were higher in 2020 than in 2019 for those with and without a college degree but, remarkably, there was little or no increase in the relative mortality rates of less-educated to more-educated Americans in 2020 over 2019.

In May 2020, Alex Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services, presumably advised by the administration’s economists, argued in the Washington Post that reopening the economy was necessary, not just for income and employment, but for health, because unemployment would bring suicides and opioid deaths, citing studies that estimated that each one percent increase in unemployment increased suicides by one percent (Reeves et al. 2012) and opioid overdose deaths by three percent (Hollingsworth et al. 2017). President Trump claimed that lockdowns would cause “tremendous death” and “suicides by the thousands.” That these predictions were borne out in fact is claimed for deaths of despair by Mulligan (2020), and for opioid overdoses by the fact that drug overdoses reached 93,331 in 2020, more than 20,000 deaths higher than the previous record of 70,630 in 2019. However, the full story is a good deal more complex.

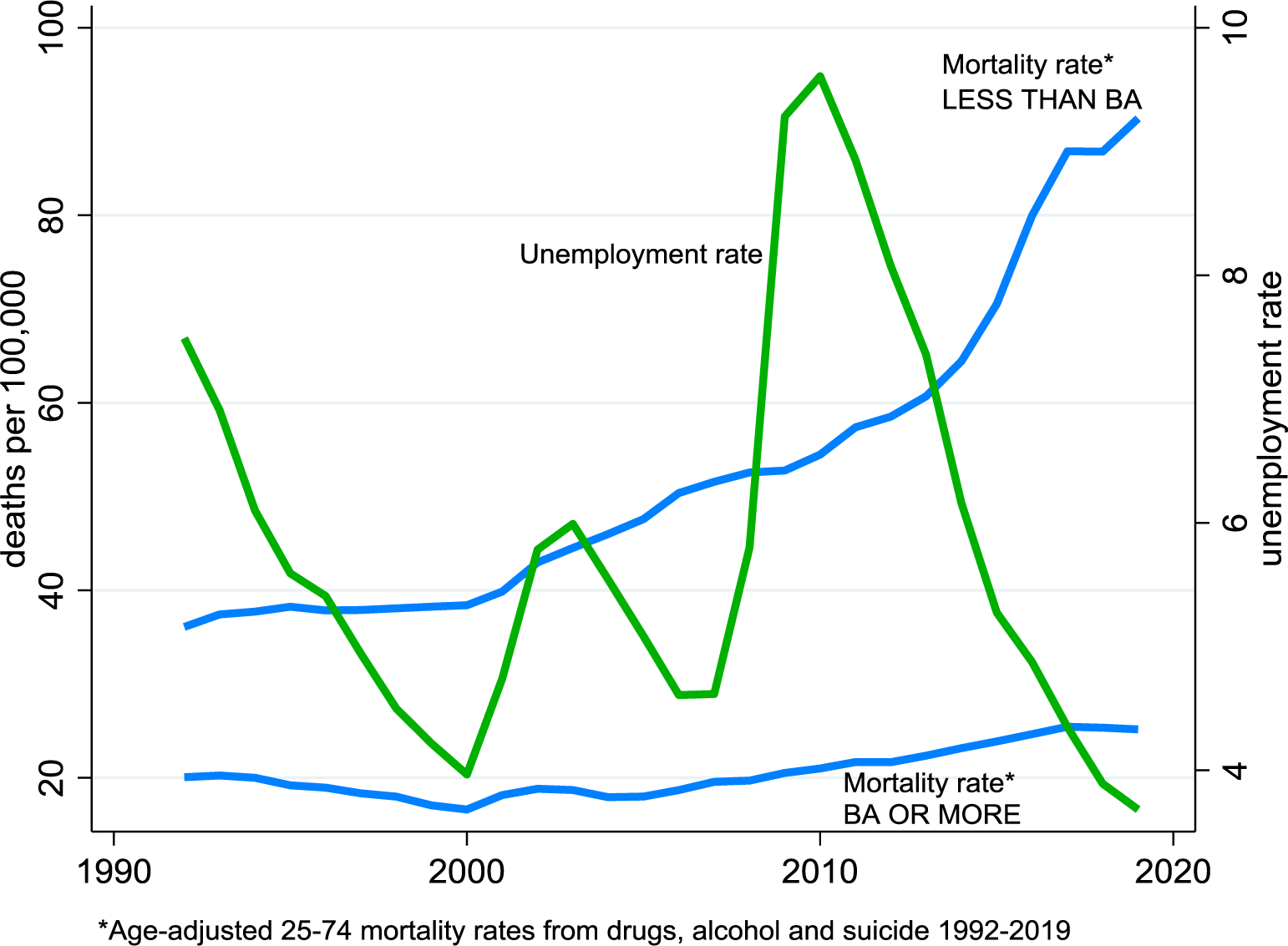

The Reeves et al (2012) finding on suicide and unemployment is replicated by Philipps & Nugent (2014). Both studies use evidence from US states; Reeves et al. use data from 1999 to 2010, and Philipps & Nugent from 1997 to 2010. Figure 3 shows the unemployment rate from 1992 to 2019 together with the mortality rate from deaths of despair; the suicide component of these deaths rose steadily over the period. If we confine ourselves to data from the late 1990s until 2010, there is a strong positive relationship between suicide and unemployment—both are trending upward—and it is those coincident trends, disaggregated to the state level, that underlie the previous results. After 2010, unemployment fell steadily as the economy recovered up to the pandemic, but there was no diminution in the inexorable rise in suicides. This disconnect, a change from the previously documented pattern, was known well before the pandemic and should have been a warning against predictions that lockdowns would drive up the national suicide rates.

Figure 3.

Unemployment and deaths of despair

The Hollingsworth et al. paper includes year fixed-effects in their state level regressions. This is equivalent to netting out all macro country-wide effects from their data, so that whatever their evidence at the state level, the macro countrywide relationship between drug deaths and unemployment has been deleted prior to their analysis, so that their state-level results cannot be used to predict—and indeed do not predict—the national toll from drug deaths associated with the pandemic. Indeed, their Figure 1 shows drug deaths continuing to rise as unemployment fell after 2010. The figures in our book, as well as in Case & Deaton (2017a), show that deaths of despair, the sum of suicides, overdose deaths, and alcoholic liver disease, were rising before the Great Recession, rose at the same rate during the Great Recession, and rose at a faster rate after the Great Recession. The unemployment rate over the recession, which rose from 5 percent in January 2008 to 10 percent in October 2009 and then slowly declined until 2019, had no perceptible effect on deaths of despair, which continued their relentless rise, see Figure 3.

Given that the aggregate time-series relationship between suicide, drug deaths, and unemployment had already ceased to exist, it is perhaps not so surprising that Azar’s predictions did not come to pass during the pandemic. The provisionally estimated suicide rate in 2020 was lower than in 2019, with 44,834 deaths as opposed to 47,511 deaths, lower than in any year since 2015, Ahmad & Anderson (2021). Compared with previous years, the decline seems to have been strongest in April and May, slowly reverting to the 2016–2019 average by the middle of the year, Rossen et al. (2021). There is similar evidence from other countries of a decline in suicides in the early month of the pandemic, Pirkis et al (2021). It is tempting, perhaps too tempting, to take the analogy between the pandemic and war, and to note the well-documented result that suicide falls in wartime, see for example Thomas & Gunnell (2010); however, the social solidarity that is associated with war is hardly a good description of the state of the US in April and May 2020.

Overdose deaths, by contrast, were substantially higher in 2020 than in 2019 or in 2018. There are reasons to expect that the COVID pandemic played a role in this. Connections with trusted drug dealers may have been broken, leaving those purchasing drugs in the hands of sellers more likely to mix drugs with fentanyl. Social isolation may have left users without someone present who could administer naloxone if an overdose occurred. Also, treatment may have been harder to access and face-to-face 12-step meetings stopped in-person gatherings for some time. That said, the increase in drug overdoses began long before the pandemic, increasing slowly through 2019, and then rapidly increasing in February, March, and April, with a peak in May 2020, before falling back to the March level by December, CDC (2021a). The May peak coincides with peak anxiety about the pandemic, but the 2019 increase in overdoses, and initial acceleration in 2020 is too early, and it is unclear why there was the decline in the second half of the year.

Most of the increase in overdose deaths came from synthetic opioids, of which fentanyl is the most important. Some of the increase is likely the spread of fentanyl to the western US; the share of drug deaths from synthetic opioids has increased from around 20 percent in 2016 to more than 60 percent by end-2020. Mulligan’s (2020) calculations are misleading because they compare 2020 with 2018 (a year in which there had been a small downturn in drug deaths), and miss the increase during 2019 and the first months of 2020, which preceded and had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Overdose deaths were running at 8,250 a month in the first four months of 2021 compared with 7,700 per month in 2020, and 5,885 per month in 2019. These numbers are large, even in comparison with COVID-19 deaths; in the first year of the pandemic, there were 100,000 overdose deaths compared with 535,000 deaths from COVID.

In summary, suicides fell in 2020, at around the time of maximum anxiety during the pandemic, drug overdose deaths rose—but they were already on their way up, though it is certainly possible that the pandemic contributed. As of the time of writing, November 2021, we know little about deaths from alcoholic liver disease, although there are concerns that alcohol and other addictions can act as coping responses, Koob et al. (2020). As was true of drug deaths, deaths from alcoholic liver disease had been rising year on year prior to the arrival of COVID, and any analysis of the epidemic’s effects will need to make assumptions about what increase in alcohol-related deaths would have occurred in its absence.

In 2020, there were 503,976 more deaths than in 2019, including 345,323 that were officially recorded as deaths from COVID-19, Ahmad & Anderson (2021). Our story at the beginning of this review was one of two Americas, with and without a college degree, and the diverging mortality rates between them. Given that the pandemic posed very different risks for more or less educated Americans, it might be expected that the mortality gap would have widened during the pandemic. The probability of dying of COVID is the product of the probability of infection and the probability of death conditional on infection. Both probabilities are higher for less-educated workers, because of differential exposure and because of higher rates of comorbidities, such as obesity and diabetes, that increase the risk of death once infected. Previously disadvantaged Americans, particularly Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians and Alaskan Natives were disproportionately likely to die, CDC (2021b), Aslan et al (2021). For the current discussion, the issue is what happened by education, an analysis of which is given in Case & Deaton (2021b). For each of six race/ethnicities, for men and for women, and for older and younger Americans, they find, as expected, that the increase in mortality rate from 2019 to 2020 was, in all cases, higher for those without a college degree. What is much more surprising is the finding that the relative mortality rates, the ratios of mortality rates for those without and with a BA, changed hardly at all from 2019 to 2020. While it was true that COVID was much more likely to kill those without a college degree, the relative mortality rates were the same as before the pandemic. It was bad in the pandemic, but it was bad before, a stunning measure of the mortality consequences of not having the degree, even in “normal” times.

CONCLUDING THOUGHT

Growing inequality in America since 1970 includes diverging fortunes for those with and without a four-year college degree. The evidence on growing mortality and morbidity that we first highlighted in 2015 continues up to and into the COVID-19 pandemic. Even if the opioid epidemic is brought under control—itself a very difficult task given that so much of the supply is now illegal—the underlying despair is likely to remain. The prospects for less-educated Americans remain bleak unless there are fundamental changes in the way that the American economy operates.

Acknowledgement:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AG060104 and R01AG053396.

Footnotes

Cutler and Glaeser (2021) present results from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) in which self-reported pain does not increase over the period from 2000 to 2016. The is curious, given that each incoming MEPS sample is a sub-sample of the previous year’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which documents increases in pain over this period. This may reflect sample attrition: the response rate for the MEPS in 2016 was about two-thirds that of the NHIS. https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_response_rate.jsp. In contrast to results reported in Cutler and Glaeser (Appendix Table A.5), we find statistically significant upward trends in lower back, neck and facial pain for adults ages 25 and older in the NHIS (1997–2018), sex- and age-adjusted to the 2000 US population.

Contributor Information

Anne Case, School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544.

Angus Deaton, School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90007.

LITERATURE CITED

- Achen CH, Bartels LM. 2016. Democracy for realists: why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. 2021. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA 325(18):1829–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsan M, Chandra A, Simon K. 2021. The great unequalizer: initial health effects of COVID-19 in the United States. J. Econ. Perspect. 35(3):25–46 [Google Scholar]

- Autor D, Dorn D, Hanson G, Majlesi K. 2020. Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. Am. Econ. Rev. 110(10):3139–83 [Google Scholar]

- Autor D, Goldin C, Katz LF. 2020. Extending the race between education and technology. AEA Pap. and Proc. 110:347–51 [Google Scholar]

- Azar AM, 2020, We have to reopen—for our health, Washington Post, May 21. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/reopening-isnt-a-question-of-health-vs-economy-when-a-bad-economy-kills-too/2020/05/21/c126deb6-9b7d-11ea-ad09-8da7ec214672_story.html [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. 2004. Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J. Public Econ. 88:1359–86 [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. 2019. Unhappiness and pain in modern America: a review essay, and further evidence, on Carol Graham’s Happiness for All. J. Econ. Lit. 57(2):385–402 [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. 2020. Trends in extreme distress in the United States, 1993–2019. Am. J. Public Health 110(10):1538–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J. 2017. Diverging life expectancies and voting patterns in the 2016 US presidential election, Am. J. Public Health 107(10):1560–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, 2015. “Deaths of despair” are killing America’s white working class, Quartz, December 30. https://qz.com/583595/deaths-of-despair-are-killing-americas-white-working-class/ [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2015. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112(49):15078–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2017a. Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act Spring:397–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2017b. Suicide, age, and wellbeing: an empirical investigation. In Insights in the Economics of Aging, ed. Wise DA, DA, pp. 307–34. Chicago: Univ Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2020. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A, Stone AA. 2020. Decoding the mystery of American pain reveals a warning for the future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117(40):24785–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2021a. Life expectancy in adulthood is falling for those without a BA degree, but as educational gaps have widened, racial gaps have narrowed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118(11): e2024777118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. 2021b. Mortality rates by college degree before and during COVID-19. NBER Work. Pap. No. 29328, Natl. Bur. Econ. Res, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2021a. Monthly provisional counts of deaths by select causes, 2020–2021. Aug 18. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Monthly-Provisional-Counts-of-Deaths-by-Select-Cau/9dzk-mvmi [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2021b. Health disparities. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm#RaceHispanicOrigin(accessed Aug 14, 2021)

- Cherlin AC. 2014. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, Lin S, Scuderi B, et al. 2016. The association between income and life-expectancy in the United States, 2001−2014. JAMA 315(16):1750–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornia GA, Paniccià R. (eds) 2000. The Mortality Crisis in Transitional Economies. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Couillard BK, Foote CL, Gandhi K, Meara E, Skinner J. 2021. Rising geographic disparities in US mortality. J. Econ. Perspect. 35(4):123–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Schwandt H. 2018. Inequality in mortality decreased among the young while increasing for older adults, 1990–2010. Science 352(6286):708–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Schwandt H. 2020. The opioid epidemic was not caused by economic distress but by factors that could be more rapidly addressed. NBER Work. Pap. No. 27544, Natl. Bur. Econ. Res, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Glaeser EL. 2021. When innovation goes wrong: technological regress and the opioid epidemic. J. Econ. Perspect. 35(4):171–96 [Google Scholar]

- Deaton A. 2012. The financial crisis and the wellbeing of America. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 64(1):1–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton A. 2018. What do self-reports of wellbeing say about life-cycle theory and policy? J. Public Econ. 162:18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Rodriguez JM, Timpe B. 2019. Weathering, drugs, and whack-a-mole: fundamental and proximate causes of widening educational inequity in U.S. life expectancy by sex and race, 1990–2015. J. Health. Soc. Behav. 60(2):222–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Glei DA, Weinstein M. 2018. Declining mental health among disadvantaged Americans. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115(28):7290–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK, Pelimar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE, eds., Reducing Suicide: a National Imperative, Washington, DC: National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C. 2017. Happiness for All? Unequal Hopes and Lives in Pursuit of the American Dream, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Grol-Prokopczyk H. 2017. Sociodemographic disparities in chronic pain, based on 12-year longitudinal data. Pain 158(2):313–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendi A 2017. Trends in education-specific life expectancy, data quality, and shifting education distributions: a note on recent research. Demography 54(3):1203–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth A, Ruhm CJ, Simon K. 2017. Macroeconomic conditions and opioid abuse. J. Health Econ. 56: 222–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Standard Classification of Education 1997. 2006. UNESCO Institute of Statistics. Re-edition http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-1997-en_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- James J 2012. The college wage premium, Economic Commentary, 2012–10, Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland; https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/economic-commentary-archives/2012-economic-commentaries/ec-201210-the-college-wage-premium.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Murray T, Thun MJ. 2008. Widening of Socioeconomic Inequalities in U.S. Death Rates, 1993–2001. PLoS ONE 3(5):e2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. 2020 Employer health benefits survey. Oct. https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2020-section-1-cost-of-health-insurance/ [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. The red/blue divide in COVID-19 vaccination rates is growing. Jul 08 https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/the-red-blue-divide-in-covid-19-vaccination-rates-is-growing/ [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Powell P, White A. 2020. Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19. Am. J. Psychiatry 177(11):1031–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuziemko I, Washington E. 2018. Why did the Democrats lose the South? Bringing new data to an old debate. Am. Econ. Rev. 108(10): 2830–67 [Google Scholar]

- Leive A, Ruhm CJ. 2020. Has mortality risen disproportionately for the least educated? NBER Work Pap. No. 27512, Natl. Bur. Econ. Res, Washington, DC: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell J. 2014. The opium war: drugs, dreams, and the making of modern China. New York: Overlook Press [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Kulhánova I, Artnik B, Bopp M, Borrell C, et al. 2016. Changes in mortality inequalities over two decades: register based study of European countries. BMJ 353:i1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Valverde JR, Artnik B, Bopp M, Brønnum-Hansen H, et al. 2018. Trends in health inequalities in 27 European countries. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115(25):6440–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy B. 2018. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America. New York: Hachette Book Group [Google Scholar]

- Masters RK, Tilstra AM, Simon DH. 2018. Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans, Int. J. Epidemiol. 47(1):81–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MA. 2017. Dismantling Solidarity: Capitalist Politics and American Pensions Since the New Deal Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. 2016. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981−2000. Health Aff 27(2):350–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzl JM, 2019, Dying of Whiteness. New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Wherry LR, Mazumder B. Estimated mortality increases during the COVID-19 pandemic by socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity. 2021. Health Aff: 40(8):1252–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIT Election Data Science Lab. 2021. electionlab.mit.edu/data

- Monnat SM. 2016. Deaths of Despair and Support for Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election. Research Brief, The Pennsylvania State University; https://smmonnat.expressions.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/ElectionBrief_DeathsofDespair.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Monnat SM, Brown DL. 2017. More than a rural revolt: landscapes of despair and the 2016 Presidential Election. J. Rural Stud. 55:227–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Hummer RA, Hayward MD, Woo H, Rogers RG. 2011. Trends in the educational gradient of US adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Res Aging 33:145–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Zajacova A. 2013. Trends in mortality risk by education level and cause of death among US white women from 1986 to 2006. Am J Public Health 103:473–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan DP. 1965, The negro family: the case for national action, Office of Policy Planning and Research, US Department of Labor, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan CB. 2020. Deaths of despair and the incidence of excess mortality in 2020. NBER Work. Pap. No. 28203, Natl. Bur. Econ. Res, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Nahin RL, Sayer B, Stussman BJ, Feinberg TM. 2019. Eighteen-year trends in the prevalence of, and health care use for, noncancer pain in the United States: Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J. Pain 20(7):796–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. 2011. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2021. High and rising mortality rates among working-age adults. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novosad P, Rafkin C, Asher S. 2020. Mortality change among less educated Americans. http://www.dartmouth.edu/ñovosad/nra-mortality.pdf

- Olfson M, Cosgrove C, Altekruse SF, Wall MM, Blanco C. 2021. Deaths of despair: adults at high risk for death by suicide, poisoning, or chronic liver disease in the US. Health Aff 40(3):505–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, Binstock RH, Boersch-Supan A, et al. 2012. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening and many may not catch up. Health Aff 31(8):1803–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethokoukis J 2021. 5 questions for Ed Glaeser on the economics of the opioid crisis, AEIdeas Blog Post, July 30. https://www.aei.org/economics/5-questions-for-ed-glaeser-on-the-economics-of-the-opioid-crisis/ [Google Scholar]

- Pethokoukis J, Glaeser E. 2021. A supply-side explanation of the opioid crisis: my long-read Q & A with Ed Glaeser, Blog post, July 29. https://www.aei.org/economics/how-did-entrepreneurs-respond-to-covid-19-my-long-read-qa-with-ed-glaeser/ [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Nugent CN. 2014. Suicide and the great recession of 2007–2009: the role of economic factors in the 50 states. Soc. Sci. & Med. 116:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J, John A, Sangsoo S, DelPozo-Banos M, Arya V, et al. 2021. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 8: 579–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt SM. 2018. Imperial Twilight: The Opium Wars and the End of China’s Last Golden Age. New York: Knopf [Google Scholar]

- Radler BT, Ryff CD. 2010. Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. J Aging Health 22(3):307–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A, Stuckler D, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang S-S, et al. 2012. Increase in state suicides in the USA during economic recession. Lancet 380(9856):1813–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H, Roser M, Ortiz-Ospina E. 2021. Suicide. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/suicide [Google Scholar]

- Robbins LN. 1993. Vietnam veterans’ rapid recovery from heroin addiction: a fluke or a normal expectation. Addiction 88:1041–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen LM, Hedegaard H, Warner M, Ahmad FB, Sutton PD. 2021. Early provisional estimates of drug overdose, suicide, and transportation-related deaths: nowcasting methods to account for reporting lags. NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release Report 011. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/reports.htm [Google Scholar]

- Rostron BL, Boies JL, Arias E. 2010. Education reporting and classification on death certificates in the United States, Vital Health Stat 2(151):1–21. National Center for Health Statistics; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Flood S, Foster S, Goeken R, Pacas J, Schouweiler M, Sobek M. 2021. IPUMS USA: Version 11.0[dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2021 10.18128/D010.V11.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ. 2021. Living and dying in America: an essay on deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. J. Econ Lit In press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel M. 2020. The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux [Google Scholar]

- Sasson I. 2016a. Trends in life expectancy and lifespan variation by educational attainment: United States, 1990−2010. Demography 53:269–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson I 2016b. Diverging trends in cause-specific mortality and life years lost by educational attainment: evidence from United States Vital Statistics Data, 1990−2010. PLoS ONE 11(10):e0163412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson I, Hayward M. 2019. Association between educational attainment and causes of death among white and black US adults, 2010−2017. JAMA 322(8):756–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]