Abstract

Background

Cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (CTCL) patients often suffer from recurrent skin infections and profound immune dysregulation in advanced disease. The gut microbiome has been recognized to influence cancers and cutaneous conditions; however, it has not yet been studied in CTCL.

Objectives

To investigate the gut microbiome in patients with CTCL and in healthy controls.

Methods

A case‐control study was conducted between January 2019 and November 2020 at Northwestern’s busy multidisciplinary CTCL clinic (Chicago, Illinois, USA) utilizing 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicon sequencing and bioinformatics analyses to characterize the microbiota present in fecal samples of CTCL patients (n = 38) and age‐matched healthy controls (n = 13) from the same geographical region.

Results

Gut microbial α‐diversity trended lower in patients with CTCL and was significantly lower in patients with advanced CTCL relative to controls (P = 0.015). No differences in β‐diversity were identified. Specific taxa were significantly reduced in patient samples; significance was determined using adjusted P‐values (q‐values) that accounted for a false discovery rate threshold of 0.05. Significantly reduced taxa in patient samples included the phylum Actinobacteria (q = 0.0002), classes Coriobacteriia (q = 0.002) and Actinobacteria (q = 0.03), order Coriobacteriales (q = 0.003), and genus Anaerotruncus (q = 0.01). The families Eggerthellaceae (q = 0.0007) and Lactobacillaceae (q = 0.02) were significantly reduced in patients with high skin disease burden.

Conclusions

Gut dysbiosis can be seen in patients with CTCL compared to healthy controls and is pronounced in more advanced CTCL. The taxonomic shifts associated with CTCL are similar to those previously reported in atopic dermatitis and opposite those of psoriasis, suggesting microbial parallels to the immune profile and skin barrier differences between these conditions. These findings may suggest new microbial disease biomarkers and reveal a new angle for intervention.

Introduction

Cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (CTCL) comprises a heterogeneous group of non‐Hodgkin’s lymphomas involving skin‐homing malignant T‐cells. While CTCL remains to be robustly understood, it is likely influenced by both host and environmental factors. Strong clinical evidence connects CTCL and the microbial world. Patients with advanced CTCL suffer from significant morbidity secondary to recurrent infections and individuals with frequent infections tend to have more advanced disease that is less responsive to CTCL therapies. 1 , 2 , 3 Moreover, prolonged courses of broad‐spectrum antibiotics have been shown to reduce malignant cytokine activity and tumor burden in advanced‐stage CTCL patients. 4 Concomitant with these phenomena is profound immune dysregulation that may be antecedent to or a consequence of pathogenic microbial activity. 5 As such, CTCL is believed to foster global microbial dysbiosis. The microbiome is an emerging focus within this field; however, the gut microbiota of CTCL have yet to be characterized.

Gut dysbiosis has been associated with cancer and inflammatory skin disease. Studies have demonstrated the tumorigenic potential of certain bacterial taxa and their powerful immunomodulatory abilities. 6 Immune dysfunction can also alter the gastrointestinal microcosm to allow or stimulate the growth of virulent bacteria. 5 This finding suggests augmented gut dysbiosis may simultaneously encourage and reflect more severe immune dysfunction. Gut dysbiosis is also understood to promote systemic disease through cytokine‐induced inflammation, aberrant effector T‐cell activation, and gut epithelial barrier disruptions that result in bacterial translocation. 5 , 7 , 8 Increased gastrointestinal abundance of pro‐inflammatory, immune‐sensitizing species like Ruminococcus gnavus and loss of anti‐inflammatory, protective species such as Faecalibacterium may be linked to the dysregulated cytokine signatures characteristic of atopic dermatitis (AD), 9 , 10 psoriasis, 11 , 12 , 13 and hidradenitis suppurativa. 14 Because gut dysbiosis has been demonstrated in other inflammatory skin conditions and cancers, we hypothesize alterations in the gut microbiome may also be associated with CTCL disease progression.

To better understand the gut microbiome of CTCL, we conducted a cross‐sectional analysis of the microbiota present in stool samples from CTCL patients and healthy controls.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00209226). Personal data and stool samples were collected from the Northwestern University Cutaneous Lymphoma specialty clinic between 2019 and 2020 in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent and HIPAA Authorization for Research were obtained from all participants prior to study enrollment. Each patient had clinically‐ and biopsy‐confirmed CTCL, as reviewed by an expert dermatopathologist (JG).

Participants

Of CTCL patients (n = 38), 27 patients had been diagnosed with mycosis fungoides (MF), 5 with Sézary syndrome (SS), and 6 with non‐MF/SS CTCL (Table 1, Table S1). Patients were untreated or receiving standard‐of‐care therapies, including skin‐directed (n = 18, 82%) and select systemic treatments (n = 10, 26%) (Table S2). Patients were excluded if they used any form of antibiotics within the preceding 4 weeks. Modified Severity‐Weighted Assessment Tool (mSWAT) was assessed by the principal investigator (XAZ). The HC group (n = 13) was composed of age‐matched volunteers without CTCL or other active skin diseases from the same geographical region. Statistical analyses were completed using STATA SE (College Station, TX, USA).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients (n = 38) and healthy controls (n = 13)

| Patients | Controls | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 38 | 13 | |

| Gender* | |||

| Male | 27 (71.0) | 7 (53.8) | 0.265† |

| Female | 11 (29.0) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Age (year)** | 64.6 (17.5–83.4) | 53.8 (24.4–79.1) | 0.118† |

| Race/ethnicity* | |||

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.235† |

| Black | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| White | 30 (79.0) | 10 (76.9) | |

| White/Hispanic | 4 (10.4) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Other/Hispanic | 1 (2.6) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Phototype* | |||

| Light (FST I–III) | 34 (89.5) | 12 (92.3) | 0.772† |

| Dark (FST IV–VI) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Comorbidities* | |||

| HTN | 13 (34.2) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000‡ |

| DLP | 16 (42.1) | 5 (38.5) | 0.529‡ |

| GERD | 10 (26.3) | 5 (38.5) | 0.487‡ |

| Diagnosis subtype* | |||

| MF | 27 (71.0) | – | |

| SS | 5 (13.2) | – | |

| Non‐MF/SS CTCL | 6 (15.8) | – | |

| Clinical stage* | |||

| Early (IA–IIA) | 20 (52.6) | – | |

| Mid/Late (IIB–IVB) | 18 (47.4) | – | |

| Disease duration (y)** | 2.7 (0.15–29.6) | – | |

| mSWAT** | 14 (2–159) | – | |

CTCL, cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma; DLP, dyslipidemia; FST, Fitzpatrick skin phototype; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux; HTN, hypertension; MF, mycosis fungoides; mSWAT, modified Severity‐Weighted Assessment Tool; SS, Sézary syndrome.

*N (%); **Median (range); †Two‐tailed t‐test; ‡Fisher’s exact test.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Patients were instructed to swab stool from toilet paper immediately after defecation using study‐provided sterile swabs and tubes. 15 , 16 Samples were sent by overnight mail to our facility and promptly stored at −80°C. Genomic DNA was extracted with a Maxwell® RSC Fecal Microbiome DNA Kit (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) on a Maxwell® RSC Instrument, following the manufacturer's protocol.

16S rRNA amplification and sequencing

Genomic DNA was prepared for sequencing using a two‐stage amplicon sequencing workflow, as described previously. 17 Genomic DNA was PCR‐amplified using primers targeting the V4 region of microbial 16S rRNA genes. The primers, 515F modified and 806R modified, contained 5′ linker sequences compatible with Access Array primers for Illumina sequencers (Fluidigm; South San Francisco, CA). 18 PCRs were performed in a total volume of 10 μL using MyTaq™ HS 2X Mix (Bioline), primers at 500 nmol/L concentration, and approximately 1000 copies per reaction of a synthetic double‐stranded DNA template (described below). Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 5′ (initial denaturation), followed by 28 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The second‐stage PCR reaction contained 1 μL of PCR product from each reaction and a unique primer pair of Access Array primers. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 5′ (initial denaturation), followed by 8 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina MiniSeq sequencer (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA) with 15% phiX spike‐in and paired‐end 2 × 153 base sequencing reads.

A synthetic double‐stranded DNA spike‐in was created as a gBLOCK by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA). The design basis was a 999 base pair (bp) region of the 16S rRNA gene of Rhodanobacter denitrificans strain 2APBS1T (NC_020541). 19 Portions of V1, V2, and V4 variable regions were replaced by eukaryotic mRNA sequences (Apostichopus japonicus glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA, HQ292612 and Strongylocentrotus intermedius glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA, KC775387). Primer sites were preserved, and the overall length of the synthetic DNA did not differ from the equivalent R. denitrificans fragment. PCR amplicons generated from this synthetic DNA do not differ in size from bacterial amplicons and can only be identified and removed through postsequencing bioinformatics analysis. The sequence can be accessed via GenBank (OK324963).

Basic processing

Forward and reverse reads were merged using PEAR v.0.9.6. 20 Merged reads were trimmed using cutadapt v1.18 to remove ambiguous nucleotides and primer sequences, and trimmed based on the quality threshold of P = 0.01. 21 Reads lacking the primer sequence and/or sequences less than 225 bp following merging and quality trimming were discarded. Chimeric sequences were identified and removed using the USEARCH algorithm with a comparison to Silva v132 reference sequence. 22 , 23 Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were identified using DADA2 v1.18 24 and annotated taxonomically using the Naïve Bayesian classifier included in DADA2 with the Silva v132 training set. Synthetic spike‐in sequences were removed before proceeding with downstream bioinformatics analyses.

Alpha diversity analyses

Shannon indices were calculated with default parameters (i.e., base = e) in R using the vegan library v2.5‐6. 25 The data were rarefied to a depth of 5000 counts/sample after removal of spike‐in sequences. A generalized linear model assuming Gaussian distribution was utilized for index modeling and significance (ANOVA) was tested using the F‐test. Post‐hoc, pairwise analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney test. 26 Plots were generated using GraphPad Prism v9.2 (GraphPad; San Diego, CA, USA).

Beta diversity analyses

The normalized data were square‐root transformed and Bray–Curtis indices were calculated without autotransformation in R using the metaMDSdist function in the vegan library v2.5‐6. 25 The dissimilarity indices were modelled and tested for significance with the sample covariates (PERMANOVA). Additional comparisons of the individual covariates were performed using ANOSIM. Plots were generated in R using the ggplot2 library. 26

Taxonomic differential analysis

Differential analyses of taxa as compared to experimental covariates were performed using edgeR v3.28.1 on raw sequence counts. 27 The data were filtered to remove sequences of chloroplast or mitochondrial origin and taxa accounting for less than 0.1% of the total sequence count. Data were normalized as counts per million and fit using a negative binomial generalized linear model using experimental covariates. Statistical tests were performed using a likelihood ratio test. Adjusted P‐values (q‐values) were calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. 28 Significant taxa were determined based on an FDR threshold of 5%. Plots were generated using GraphPad Prism v9.2.

Data accession

The raw 16S rRNA sequences reported here are accessible on the NCBI Short Read Archive (PRJNA767860).

Results

Clinical characteristics of CTCL patients and healthy controls

Thirty‐eight unique CTCL patients and 13 age‐matched HC were enrolled in this study. All subjects were from the same geographical region (Chicago metropolitan area, United States) to reduce the impact of environmental variation on the microbiota. 29 Four HC‐CTCL pairs sharing a home were selected for even closer matching. To avoid bias in sample collection, manipulation, and analysis, we concurrently enrolled patients and controls rather than rely on publicly available human microbiome data.

Twenty‐seven (71.0%) CTCL patients were male; median patient age was 64.6 (range 17.5–83.4) years. Seven (53.8%) HC were male; the median age was 53.8 (range 24.4–79.1) years. There was no significant difference in gender, age, race/ethnicity, or phototype between the groups (Table 1). Twenty patients had early‐stage disease (stage IA‐IIA; 52.6%), while 18 had mid/late‐stage disease (stage IIB–IVB; 47.4%); stage IB was the most common overall (n = 12, 31.6%). The median disease duration from diagnosis to sample collection was 5.4 (range 0.15–29.6) years and the median mSWAT was 14 (range 2–159). The great majority (73.7%) of patients were not on any systemic CTCL therapies. Six (15.8%) patients had a remote history of non‐CTCL cancer, but all were in remission at the time of sample collection.

The study groups shared similar comorbidity profiles, the most common comorbidities being hypertension (CTCL: n = 13, 34.2% vs. HC: n = 4, 30.8%; Fisher’s exact test P = 1.00), dyslipidemia (CTCL: n = 16, 42.1% vs. HC: n = 5, 38.5%; P = 0.529), and gastroesophageal reflux (CTCL: n = 10, 26.3% vs. HC: n = 5, 38.5%; P = 0.487). There were no differences in surveyed dietary patterns, including processed food intake, dairy intake, organic/hormone‐free meat intake, pre/probiotic use, and alcohol consumption (Table S4).

Sequencing and taxonomic characteristics of sample cohort

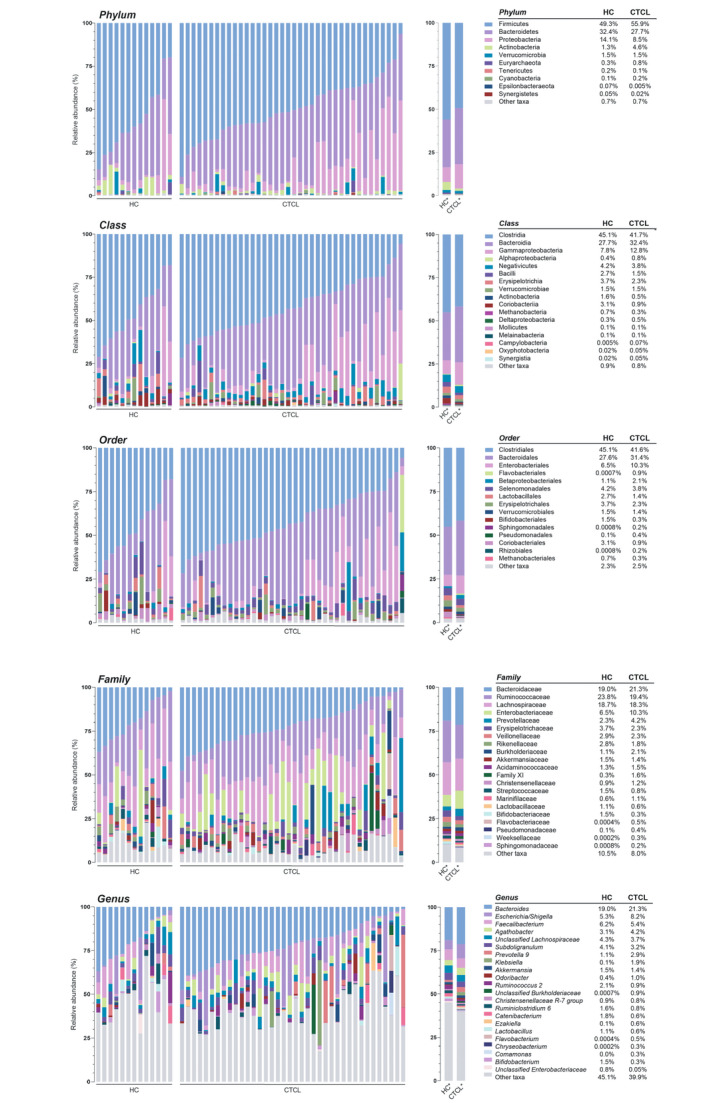

Bacterial DNA extracted from stool samples was used for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. A total of 4 914 148 paired‐end reads were generated with an average of 96 355 reads per sample. Quality filtering of the reads produced a total of 4 194 176 reads with an average of 82 239 reads per sample. Swab, reagent, and PCR controls were negative for any significant contamination. In total, 472 genera, 152 families, 73 orders, 33 classes, and 18 phyla of microorganisms were detected in all samples. The 4 most abundant phyla in both subject groups were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria – all normally found in the human gut (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Relative sequence abundance of bacterial taxa in fecal samples at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels. Relative sequence abundances (%) were calculated for the cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (CTCL) patient and healthy control (HC) cohorts at each taxonomic level. Phylum and class were filtered to highlight all taxa with greater than 1.0% relative abundance, order was filtered to greater than 5.0% relative abundance, and family and genus were filtered to greater than 10.0% relative abundance. Each taxonomic level is visualized by the individual subject (left) and the mean relative abundance of each bacterial taxa (right). The mean relative abundances are also delineated for each level (right).

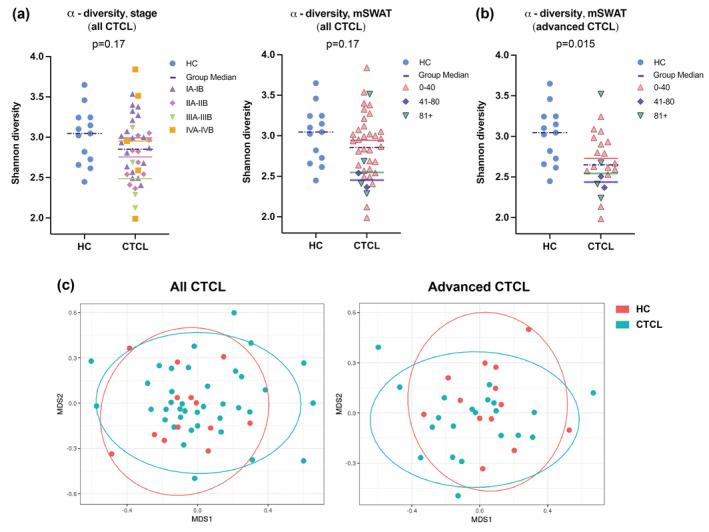

There were no significant differences in α‐diversity at any taxonomic level, but α‐diversity trended lower in CTCL patients vs. controls at the genus level (Figs 2a and S1; Kruskal–Wallis P = 0.17). The β‐diversity analysis demonstrated no global differences in microbial community structure between patients and controls (Fig. 2c; PERMANOVA R 2 = 0.0193, P = 0.488; ANOSIM R = −0.013, P = 0.627).

Figure 2.

α‐ and β‐diversity of the gut microbiota of CTCL patient and HC cohorts. (a) α‐diversity trended lower among all CTCL patients compared to HC but was not statistically significant (P = 0.17), as represented by the Shannon diversity score. Dots are colour‐coded for mycosis fungoides (MF)/Sézary syndrome (SS) clinical stage (left) and modified Severity‐Weighted Assessment Tool (mSWAT) (right) divisions. Group medians are denoted by coloured horizontal bars. (b) Among advanced CTCL patients, α‐diversity was significantly lower compared to HC (P = 0.015), as represented by the Shannon diversity score. Dots are colour‐coded for mSWAT divisions and group medians are denoted by coloured horizontal bars. (c) Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots of gut microbial communities based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity analysis performed at the taxonomic level of genus shows no global differences in gut microbial community structure between CTCL patient and HC samples (PERMANOVA R 2 = 0.019, P = 0.49) or between advanced CTCL patient and HC samples (R 2 = 0.038, P = 0.15).

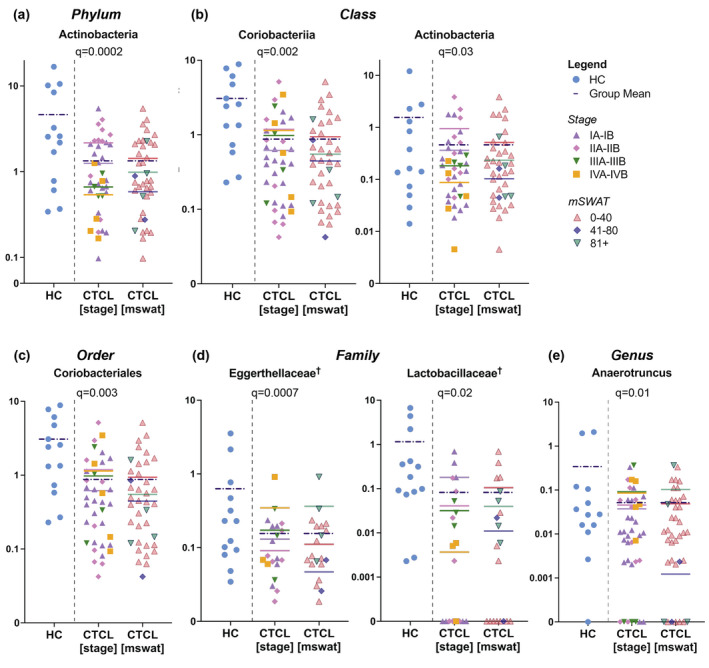

Gut microbiome of CTCL patients shows shifts of specific bacterial taxa

Taxon‐by‐taxon analysis revealed that the abundance of certain bacterial populations in CTCL patients is significantly different than that of HC (Fig. 3; Table S2A). When compared to controls, the CTCL group showed significant decreases in the relative abundance of bacteria from the phylum Actinobacteria (q < 0.001), classes Coriobacteriia (q < 0.01) and Actinobacteria (q = 0.03), and order Coriobacteriales (q < 0.01) (Fig. 3a–c). Reduced mean relative abundance of Actinobacteria at the phylum and class levels correlated with increased stage and mSWAT, but this trend was less compelling within the Coriobacteriia and Coriobacteriales data.

Figure 3.

Specific gut bacterial taxa differ between CTCL patients and controls. Dot plots illustrate the relative sequence abundance (%) of taxa that were significantly different in CTCL patients organized by MF/SS clinical stage (left) and mSWAT (right) vs. HC at the (a) phylum, (b) class, (c) order, (d) family, and (e) genus levels. Data are shown on a log scale. Group means are denoted by coloured horizontal bars. †Advanced CTCL only.

At the genus level, Anaerotruncus (q = 0.01) was significantly less abundant in the gut microbiota of CTCL patients vs. HC (Fig. 3e) and mean relative abundance was directly related to clinical stage and mSWAT. Unclassified Eggerthellaceae (q < 0.01) and unclassified Enterobacteriaceae (q < 0.01) were also less abundant, but they did not fit into defined clades and were not graphed. Other genera that trended towards significance (P < 0.05 but q > 0.05) included Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, unclassified Clostridiales Family XIII, Romboutsia, Angelakisella, and unclassified Erysipelotrichaceae, which were more abundant in controls vs. patients; and Prevotella, Erysipelatoclostridium, Faecalitalea, unclassified Burkholderiaceae, Solobacterium, Lawsonella, and Dielma, which were more abundant in patients vs. controls.

CTCL patients with greater active disease burden are associated with distinct microbial communities and reduced microbial richness compared to healthy controls

We separately examined patients with greater active disease burden – defined as CTCL stage IB or higher and substantial skin involvement (mSWAT > 10) at the time of sample collection (designated ‘advanced CTCL’) – because they are more likely to have systemic rather than skin‐only immune dysregulation and dysbiosis. In this analysis, α‐diversity at the genus level was significantly lower in patients compared to controls (Fig. 2b; P = 0.015). β‐diversity analysis revealed significant dissimilarity between groups at the phylum (PERMANOVA R 2 = 0.115, P = 0.016), class (R 2 = 0.091, P = 0.014), order (R 2 = 0.072, P = 0.023), and family (R 2 = 0.054, P = 0.049) levels, but not at the genus level (R 2 = 0.038, P = 0.149) (Fig. 2c). Differential taxonomic analysis of this more advanced cohort (Table S2B) identified a significantly decreased relative abundance of Eggerthellaceae (q = 0.01) and Lactobacillaceae (q = 0.01) at the family level, but not at the genus level (Fig. 3d). Reduced mean relative abundance of Eggerthellaceae was associated with lower clinical stage and mSWAT, but the inverse was observed for Lactobacillaceae. Those genera approaching significance in this analysis mirrored those in the full dataset. Additional genera with relatively lower abundance in advanced CTCL vs. controls included Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae ND3007 group, and Oxalobacter. Sellimonas and unclassified Christensenellaceae were relatively more abundant in the gut of patients with advanced CTCL compared to controls.

Discussion

Using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, we elucidated the gut microbial profiles of 38 CTCL patients and 13 healthy, age‐matched individuals. Our results suggest bacterial dysbiosis is more pronounced in CTCL patients with more advanced disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize the gut microbiome in CTCL and describe the alterations therein. It is also one of the largest microbiome sample sets for this disease to date. The rarity of CTCL underscores the importance of this carefully curated dataset, despite its relatively smaller sample size compared to studies examining substantially more common cancers.

Gut dysbiosis has been explored in myriad diseases, including cutaneous conditions, 11 , 13 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 and hematological 35 , 36 , 37 and visceral malignancies (Table S3). 38 , 39 , 40 These studies have revealed certain dysbiotic signatures are associated with cytokine cascades and skewed immune activity that promote disease progression. AD and psoriasis – inflammatory skin diseases often discussed against CTCL because of their distinct skin and immunological features – are among those conditions affected by this phenomenon (Table 2).

Table 2.

Immunologic, skin barrier, and skin microbiome differences between CTCL, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis

| CTCL | Atopic dermatitis | Psoriasis |

|---|---|---|

| Immunologic features | ||

| Th2‐predominant | Th2‐predominant | Th17/Th1‐predominant |

| Serum IgE levels correlate with pruritis 70 and baseline eosinophilia is a prognostic factor of poor outcomes 71 | Increased IgE levels and circulating eosinophils 44 | Normal IgE levels and circulating eosinophils 44 |

| Skin barrier features | ||

| Frequent Staphylococcus aureus skin colonization | Frequent Staphylococcus aureus skin colonization | Bacterial colonization uncommon |

| Skin infections increasingly common with advanced disease | Skin infections common | Skin infections rare |

| Decreased antimicrobial peptides (S100A7, S100A8, and S100A9) in lesional skin, conferring reduced antimicrobial activity 70 | Decreased S100A7 and S100A8 expression, conferring reduced antimicrobial activity 70 | Enhanced S100A7 and S100A8 expression, conferring enhanced antimicrobial activity 70 |

| Decreased filaggrin and loricrin expression in patch and plaque CTCL lesions, indicating loss of normal skin barrier function; increased expression in tumor and erythrodermic CTCL 70 | Decreased filaggrin and loricrin expression, indicating loss of normal skin barrier function 70 | Decreased filaggrin and loricrin expression, indicating loss of normal skin barrier function 70 |

| Skin microbiome features | ||

| Skin bacterial shifts may correlate with disease progression; no differences are observed in diversity 72 | Decrease in skin microbiome diversity correlates with increased disease severity 73 | Reduced skin microbiome diversity compared to healthy individuals 74 |

CTCL and AD are characterized by Th2‐predominant cytokine profiles, severe pruritis, similar skin barrier defects, and frequent Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection. 41 , 42 In contrast, psoriasis is Th17/Th1‐driven with opposing skin barrier features compared to CTCL and AD, and patients infrequently develop skin infections or bacterial colonization. 43 , 44 Consistent with these differences, we observed the direction of taxa shifts in CTCL contrasts with that in psoriasis 11 , 12 , 13 , 33 , 45 and is more aligned with that found in AD (Table 3). 10 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49

Table 3.

Gut microbiome differences between CTCL, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis

| CTCL | Atopic dermatitis | Psoriasis |

|---|---|---|

|

Bifidobacteriaceae Bifidobacterium ↓ |

Bifidobacteriaceae (not seen) 10 |

Bifidobacteriaceae ↑ 13 |

|

Coriobacteriaceae Collinsella ↓ |

Coriobacteriaceae ↓ 10 |

Coriobacteriaceae ↑ 13 Collinsella aerofaciens ↑ 11 |

|

Eggerthellaceae Unclassified Eggerthellaceae ↓ |

Eggerthellaceae |

Eggerthellaceae ↑ 13 |

|

Prevotellaceae Prevotella ↑ Prevotella 6 ↓* Unclassified Prevotellaceae ↑ |

Prevotellaceae Paraprevotella (infants) ↑† 76 Prevotella stercorea (not seen) 48 |

Prevotellaceae ↑ 13 Prevotella ↑ 12 Prevotella copri ↓ 11 |

|

Lactobacillaceae Lactobacillus ↓* |

Lactobacillaceae |

Lactobacillaceae ↓ 13 |

|

Erysipelotrichaceae Dielma ↑ Faecalitalea ↑ Erysipelatoclostridium ↑ Solobacterium ↑ Unclassified Erysipelotrichaceae ↓ |

Erysipelotrichaceae (not seen) 10 Bulleidia (not seen) 10 |

Erysipelotrichaceae ↑ 13 |

|

Clostridiales Family XIII ↓ Unclassified Family XIII ↓ |

Clostridiales Clostridium cluster IV ↓ 77 Clostridium cluster XI (infants) ↓† 76 |

Clostridiales Family XIII ↑ 13 Ruminococcaceae ↑ 13 |

|

Ruminococcaceae Anaerotruncus ↓ Angelakisella ↓ |

Ruminococcaceae ↓ |

Ruminococcaceae ↑ 13 Ruminococcus gnavus ↑ 11 |

|

Lachnospiraceae Lachnospiraceae ND3007 group ↓* Sellimonas ↑* |

Lachnospiraceae |

Lachnospiraceae ↑ 13 Coprococcus ↓ 45 Dorea formicigenerans ↑ 11 |

|

Peptostreptococcaceae Romboutsia ↓ |

‐ | Peptostreptococcaceae ↑ 13 |

|

Burkholderiales Burkholderiaceae Unclassified Burkholderiaceae ↑ |

Burkholderiales Sutterellaceae |

Burkholderiales |

|

Oxalobacteraceae Oxalobacter ↓* |

↑ enriched in patients; ↓ decreased in patients.

Advanced disease only.

Patients aged 0–12 months old.

Considering these comparisons and given the bidirectional influence exercised by the gut microbiome and immune system, the question remains whether the changes in the gut microbiota are epiphenomena of disease or if dysbiosis influences disease course. 5 Notably, Coriobacteriaceae, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium, which appear reduced in CTCL, have been shown to be beneficial commensals. 50 Bacteria from the family Coriobacteriaceae are known to strengthen gut barrier function 51 ; species from the genus Lactobacillus are capable of cytokine‐based anti‐inflammatory activity 52 ; and species from the genus Bifidobacterium may promote daily colonic epithelial renewal, which inhibits the overgrowth of pathogenic species. 38 Additionally, the presence of Ruminococcaceae has been shown to inversely correlate with IL‐6 and C‐reactive protein levels. 53 The dysbiotic signatures characterizing CTCL, AD, and psoriasis may be explained by the complex interactions constituted by the gut microbiome and immune system.

Furthermore, gut microbial signatures of several malignancies share broad themes with the dysbiosis identified here. Certain bacterial subpopulations are known to influence oncogenesis through direct immune modulation and the systemic reach of bacterial metabolites. 6 Prevotellaceae and Bacteroidaceae have been shown to promote local and distant Th17 differentiation and subsequent IL‐17 release. 54 Multiple groups have discussed a causative link between chronic IL‐17‐mediated inflammation and malignancy. 55 , 56 Th17 cells may contribute to CTCL pathogenesis, but this relationship remains to be fully explored. 57 The loss of butyrate‐producing species and enrichment of lipopolysaccharide‐secreting species have also been linked to tumor proliferation. 32 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 58 , 59 Butyrate, a short‐chain fatty acid, can induce cancer cell apoptosis via inhibition of histone deacetylase activity, 6 , 60 , 61 a mechanism mirrored by the chemotherapy agents vorinostat and romidepsin, which are a crucial part of the treatment armamentarium for relapsed and refractory CTCL. 62 Meanwhile, lipopolysaccharide, an endotoxin characteristic of the Proteobacteria phylum, stimulates tumorigenic cytokine cascades. 63 Our CTCL samples were associated with the loss of butyrate producers (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Anaerotruncus in the total cohort and Lactobacillus in advanced CTCL) and Proteobacteria dysbiosis. Further research on the influence of these metabolic pathways in CTCL is warranted.

Study limitations included our small sample size and patient heterogeneity. Though most of our patient subjects were diagnosed with MF and SS, there was variation in disease subtype and staging across our cohort. Despite the wide range of disease duration amongst MF/SS patients, regression analyses demonstrated there was no significant association between disease duration and measures of gut dysbiosis. While patients with recent antibiotic use were excluded, those with advanced disease may have had a distant history of frequent antibiotic exposure with lasting microbiome consequences; however, the dysbiosis identified in these patients remains noteworthy as it still may influence immune function and disease progression. Other treatments were not considered significant confounders because the taxa shifts associated with early‐stage disease matched those of late‐stage disease. We nonetheless chose patients who were naive to or had a long and consistent history of systemic CTCL therapy given its potential to influence the gut microbiota. Among the few systemic treatments cited by patients, only methotrexate has been found to influence the microbiome, but there is no correlation between the differentially abundant taxa in our CTCL group and the taxa inhibited by this drug. 64 Furthermore, although retinoids and immune modulators like interferon‐α may indirectly interact with the immune‐mediated microbiome, more research is needed to support this theory. 64 The similar comorbidity profiles of the study groups helped to control for differences in non‐CTCL medication use. Moreover, our simultaneous enrollment of healthy individuals alongside patients helped control for age, geography, temporality, and data processing within this comparative analysis.

CTCL may be a disease of global dysbiosis. The link connecting CTCL and the microbial world is epitomized by the often‐reported association between disease progression and cutaneous S. aureus infections. 65 Interestingly, Hu and colleagues demonstrated in a mouse model that fecal transplants may not only reverse gut dysbiosis but also reestablish barrier function (e.g., blood–milk barrier) and reduce S. aureus mastitis morbidity. 66 These results further support the importance of the gut microbiota on distant host barrier sites. Indeed, this work may translate into future therapeutic clinical trials for CTCL utilizing probiotics or fecal microbial transplants, which comprise an emerging treatment focus within cancer research. 67 , 68 , 69

This is the first study to characterize the gut dysbiosis associated with CTCL, which increases with disease severity and potentially contributes to the severe immune dysfunction concomitant with advanced disease. While multicentre, longitudinal, and treatment‐based studies will add important insights to this discussion, the microbiome and CTCL appear to be intimately connected. Future endeavours within this promising area of research may improve our understanding of CTCL pathophysiology; identify diagnostic and prognostic markers to improve advanced disease management; and possibly elucidate novel therapeutic options for this still poorly understood disease.

Supporting information

Table S1. Detailed demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients (n = 38) and healthy controls (n = 13).

Table S2. Differential taxonomic analysis demonstrates unique microbial signatures at the genus level in stool samples from (A) CTCL patients vs. healthy controls, and (B) advanced CTCL patients vs. healthy controls.

Table S3. Comparison of relative taxonomic abundance in the gut microbiomes of patients vs. healthy controls as observed in CTCL and as previously reported in other cutaneous diseases and malignancies.

Table S4. Dietary characteristics of patients (n = 38) and health controls (n = 13).

Figure S1. No significant differences in α‐diversity, as represented by Shannon diversity scores, were detected in (a) CTCL patients vs. HC, and (b) advanced CTCL patients vs. HC, except for at the genus level. Group medians are represented by horizontal bars.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who contributed to the study. XAZ is supported in part by a career development award from the Dermatology Foundation, a Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation Catalyst Research Grant, and an institutional grant from Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute and National Institute of Health (Grant 5KL2TR001424).

Funding sources

Supported by a Dermatology Foundation Medical Dermatology Career Development Award, Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation Catalyst Research Grant, and an institutional grant from the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (NUCATS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (KL2TR001424).

Co‐first authors.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI Short Read Archive under the accession number PRJNA767860 at https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA767860?reviewer=g3g8mn7sbvgglsdo4f3bgivig8.

References

- 1. Dulmage BO, Kong BY, Holzem K, Guitart J. What is new in CTCL—pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Dermatol Rep 2018; 7: 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fanok MH, Sun A, Fogli LK et al. Role of dysregulated cytokine signaling and bacterial triggers in the pathogenesis of cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma. J Investig Dermatol 2018; 138: 1116–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willerslev‐Olsen A, Krejsgaard T, Lindahl LM et al. Bacterial toxins fuel disease progression in cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma. Toxins 2013; 5: 1402–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindahl LM, Willerslev‐Olsen A, Gjerdrum LMR et al. Antibiotics inhibit tumor and disease activity in cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2019; 134: 1072–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system: the gut microbiota. Science 2012; 336: 1268–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vivarelli S, Salemi R, Candido S et al. Gut microbiota and cancer: from pathogenesis to therapy. Cancers 2019; 11: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Neill CA, Monteleone G, McLaughlin JT, Paus R. The gut‐skin axis in health and disease: a paradigm with therapeutic implications. BioEssays 2016; 38: 1167–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salem I, Ramser A, Isham N, Ghannoum MA. The gut microbiome as a major regulator of the gut‐skin axis. Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song HP, Yoo YMDP, Hwang JP, Na Y‐CP, Kim HSP. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii subspecies–level dysbiosis in the human gut microbiome underlying atopic dermatitis. J All Clin Immunol 2015; 137: 852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reddel S, Del Chierico F, Quagliariello A et al. Gut microbiota profile in children affected by atopic dermatitis and evaluation of intestinal persistence of a probiotic mixture. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapiro J, Cohen NA, Shalev V et al. Psoriatic patients have a distinct structural and functional fecal microbiota compared with controls. J Dermatol 2019; 46: 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Codoñer FM, Ramírez‐Bosca A, Climent E et al. Gut microbial composition in patients with psoriasis. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 3812–3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hidalgo‐Cantabrana C, Gómez J, Delgado S et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a cohort of patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1951; 2019(181): 1287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCarthy S, Barrett M, Kirthi S et al. Altered skin and gut microbiome in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2022; 142(2): 459–468.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Human Microbiome Project C . A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012; 486: 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Knight R et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012; 486: 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naqib A, Poggi S, Wang W et al. Making and sequencing heavily multiplexed, high‐throughput 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicon libraries using a flexible. Two‐Stage PCR Protocol. Gene Exp Analysis 2018; 1783: 149–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walters W, Hyde ER, Berg‐Lyons D et al. Improved bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V4 and V4‐5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys. mSystems. 2016; 1: 4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prakash O, Green S, Jasrotia P et al. Description of Rhodanobacter denitrificans sp. nov., isolated from nitrate‐rich zones of a contaminated aquifer. Int J Sys Evol Microbiol 2012; 62(Pt_10): 2457–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang J, Kobert K, Flouri T, Stamatakis A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired‐End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high‐throughput sequencing reads. Embnetjournal 2011; 17: 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glöckner FO, Yilmaz P, Quast C et al. 25 years of serving the community with ribosomal RNA gene reference databases and tools. J Biotechnol 2017; 261: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edgar RC. Quality measures for protein alignment benchmarks. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38: 2145–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ et al. DADA2: High‐resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016; 13: 581–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okansen J, Guillaume Blanchet F, Kindt R et al. Vegan: community ecology. R Package Version. 2018;2; 4‐6.

- 26. Wickham H. ggplot2 : Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 1st ed. Springer New York, New York, NY, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA‐Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40: 4288–4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol.) 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature (London) 2018; 555: 210–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kam S, Collard M, Lam J, Alani RM. Gut microbiome perturbations in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a case series. J Investig Dermatol 2021; 141: 225–228.e222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Dermato‐venereol 2018; 98: 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yan HM, Zhao HJ, Guo DY et al. Gut microbiota alterations in moderate to severe acne vulgaris patients. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 1166–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen Y‐J, Ho HJ, Tseng C‐H et al. Intestinal microbiota profiling and predicted metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients. Exp Dermatol 2018; 27: 1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bzioueche H, Simonyté Sjödin K, West CE et al. Analysis of matched skin and gut microbiome of patients with vitiligo reveals deep skin dysbiosis: link with mitochondrial and immune changes. J Investig Dermatol 2021; 141: 2280–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chua LL, Rajasuriar R, Azanan MS et al. Reduced microbial diversity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and microbial associations with increased immune activation. Microbiome 2017; 5: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rajagopala SV, Yooseph S, Harkins DM et al. Gastrointestinal microbial populations can distinguish pediatric and adolescent Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) at the time of disease diagnosis. BMC Genom 2016; 17: 635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cozen W, Yu G, Gail MH et al. Fecal microbiota diversity in survivors of adolescent/young adult Hodgkin lymphoma: a study of twins. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 1163–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma‐carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang Q, Chiu J, Chen Y et al. Fecal bacteria act as novel biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 2061–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ren Z, Li A, Jiang J et al. Gut microbiome analysis as a tool towards targeted non‐invasive biomarkers for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2019; 68: 1014–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salava A, Deptula P, Lyyski A et al. Skin microbiome in cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma by 16S and whole‐genome shotgun sequencing. J Investig Dermatol 2020; 140: 2304–2308.e2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 9717530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Strober W. Susceptibility of atopic dermatitis versus psoriasis to superinfection is related to production of β‐defensins. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2004; 4: 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guttman‐Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis—Part I: Clinical and pathologic concepts. J All Clin Immunol 2011; 127: 1110–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015; 67: 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abrahamsson TRMDP, Jakobsson HEM, Andersson AFP et al. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J All Clin Immunol 2011; 129: 434–440.e432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang MF, Sy HY, Kwok JSL et al. Eczema susceptibility and composition of faecal microbiota at 4 weeks of age: a pilot study in Chinese infants. Br J Dermatol 1951; 2016(174): 898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ye S, Yan F, Wang H et al. Diversity analysis of gut microbiota between healthy controls and those with atopic dermatitis in a Chinese population. J Dermatol 2021; 48: 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. West CE, Rydén P, Lundin D et al. Gut microbiome and innate immune response patterns in IgE‐associated eczema. Clin Exp Allergy 2015; 45: 1419–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Purchiaroni F, Tortora A, Gabrielli M et al. The role of intestinal microbiota and the immune system. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013; 17: 323–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turnbaugh PJ. Fat, bile and gut microbes. Nature 2012; 487: 47–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yamamoto ML, Maier I, Dang AT et al. Intestinal bacteria modify lymphoma incidence and latency by affecting systemic inflammatory state, oxidative stress, and leucocyte genotoxicity. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 4222–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rajagopala SV, Singh H, Yu Y et al. Persistent gut microbial dysbiosis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) during chemotherapy. Microb Ecol 2020; 79: 1034–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Calcinotto A, Brevi A, Chesi M et al. Microbiota‐driven interleukin‐17‐producing cells and eosinophils synergize to accelerate multiple myeloma progression. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grivennikov SI, Kepeng W, Datz C et al. Adenoma‐linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL‐23/IL‐17‐mediated tumour growth. Nature (London) 2012; 491: 254–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rutkowski Melanie R, Stephen Tom L, Svoronos N et al. Microbially driven TLR5‐dependent signaling governs distal malignant progression through tumor‐promoting inflammation. Cancer Cell 2015; 27: 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goel S, Fogli LK, Sundrud M et al. Role of STAT3 and Th17 cells in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Blood 2012; 120: 66. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bai L, Zhou P, Li D, Ju X. Changes in the gastrointestinal microbiota of children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and its association with antibiotics in the short term. J Med Microbiol 2017; 66: 1297–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gui Q, Li H, Wang A et al. The association between gut butyrate‐producing bacteria and non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Lab Anal 2020; 34: e23318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wei W, Sun W, Yu S, Yang Y, Ai L. Butyrate production from high‐fiber diet protects against lymphoma tumor. Leukemia Lymphoma 2016; 57: 2401–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu X, Wu Y, He L et al. Effects of the intestinal microbial metabolite butyrate on the development of colorectal cancer. J Cancer 2018; 9: 2510–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jain S, Zain J, O’Connor O. Novel therapeutic agents for cutaneous T‐Cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol 2012; 5: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dapito Dianne H, Mencin A, Gwak G‐Y et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell 2012; 21: 504–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M et al. Extensive impact of non‐antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 2018; 555: 623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Blümel E, Willerslev‐Olsen A, Gluud M et al. Staphylococcal alpha‐toxin tilts the balance between malignant and non‐malignant CD4(+) T cells in cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma. Oncoimmunology 2019; 8: e1641387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hu X, Guo J, Zhao C et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the development of Staphylococcus aureus‐induced mastitis in mice. Isme J 2020; 14: 1897–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hibberd AA, Lyra A, Ouwehand AC et al. Intestinal microbiota is altered in patients with colon cancer and modified by probiotic intervention. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2017; 4: e000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chumsri S. Engineering Gut Microbiome to Target Breast Cancer, 2017‐2020. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA. [WWW document]. URL https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03358511 (last accessed: 30 November 2021).

- 69. Fan L. Probiotics combined with chemotherapy for patients with advanced NSCLC, 2019‐2024. Shanghai 10th People's Hospital, Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, Shanghai, China, Shanghai Chest Hospital. [WWW document]. URL https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03642548 (last accessed: 30 November 2021).

- 70. Suga H, Sugaya M, Miyagaki T et al. Skin barrier dysfunction and low antimicrobial peptide expression in cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 4339–4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tancrède‐Bohin E, Ionescu MA, de La Salmonière P et al. Prognostic value of blood eosinophilia in primary cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Harkins CP, MacGibeny MA, Thompson K et al. Cutaneous T‐Cell lymphoma skin microbiome is characterized by shifts in certain commensal bacteria but not viruses when compared with healthy controls. J Investig Dermatol 2021; 141: 1604–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Paller AS, Kong HH, Seed P et al. The microbiome in patients with atopic dermatitis. J All Clin Immunol 2019; 143: 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang W‐M, Jin H‐Z. Skin microbiome: an actor in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Chin Med J 2018; 131: 95–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Watanabe S, Narisawa Y, Arase S et al. Differences in fecal microflora between patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy control subjects. J All Clin Immunol 2003; 111: 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zheng H, Liang H, Wang Y et al. Altered gut microbiota composition associated with eczema in infants. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0166026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Candela M, Rampelli S, Turroni S et al. Unbalance of intestinal microbiota in atopic children. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tan L, Zhao S, Zhu W et al. The Akkermansia muciniphila is a gut microbiota signature in psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 2018; 27: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Detailed demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients (n = 38) and healthy controls (n = 13).

Table S2. Differential taxonomic analysis demonstrates unique microbial signatures at the genus level in stool samples from (A) CTCL patients vs. healthy controls, and (B) advanced CTCL patients vs. healthy controls.

Table S3. Comparison of relative taxonomic abundance in the gut microbiomes of patients vs. healthy controls as observed in CTCL and as previously reported in other cutaneous diseases and malignancies.

Table S4. Dietary characteristics of patients (n = 38) and health controls (n = 13).

Figure S1. No significant differences in α‐diversity, as represented by Shannon diversity scores, were detected in (a) CTCL patients vs. HC, and (b) advanced CTCL patients vs. HC, except for at the genus level. Group medians are represented by horizontal bars.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI Short Read Archive under the accession number PRJNA767860 at https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA767860?reviewer=g3g8mn7sbvgglsdo4f3bgivig8.