Abstract

In a test of the hypothesis that DevR is a response regulator protein that functions in a phosphorelay signal transduction system involved in heterocyst development in Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, purified affinity-tagged DevR was shown to be phosphorylated in vitro by the noncognate sensor kinase EnvZ. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate N. punctiforme mutants with single amino acid substitutions at the putative phosphorylation site of DevR. These mutants exhibited a Fox− phenotype like the original devR insertion mutant UCD 311, consistent with a phosphotransferase role for DevR.

When limited for combined nitrogen, certain filamentous cyanobacteria, including Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, respond by initiating a developmental program that results in the production of terminally differentiated nitrogen-fixing cells known as heterocysts. These specialized cells occur as 3 to 10% of the total cell population and are typically found singly at regular intervals along the filaments. Mature heterocysts differ from the vegetative cells from which they arise in several ways that reflect their role in providing a micro-oxic environment for the oxygen-sensitive enzyme nitrogenase (30): they lack the oxygen-producing reactions of photosystem II, they have a high rate of respiratory oxygen uptake, and they have a unique envelope consisting of an inner glycolipid layer and an outer polysaccharide layer that is located outside the cell wall. This envelope is thought to impede the diffusion of oxygen into the cell while allowing the entry of sufficient dinitrogen for nitrogen fixation (28, 30).

Several genes that are involved in the differentiation of heterocysts have been identified and cloned. The proteins encoded by these genes include some that are required for the initiation of heterocyst differentiation, such as NtcA, a global nitrogen-regulatory protein (13, 29), and HetR, an autoregulated serine-type protease that accumulates in cells destined to become heterocysts and whose synthesis is enhanced within 3 h after deprivation for combined nitrogen (2, 4, 31). Genes that are essential in the later stages of heterocyst development have also been identified. These genes include those that are required for the formation of a mature, functional heterocyst envelope, such as devBCA (12), hglK (1), and hglE (5), which are involved in the production and assembly of the glycolipid layer, and hepK (11) and hepA (17), which are required for the synthesis of envelope polysaccharide (32).

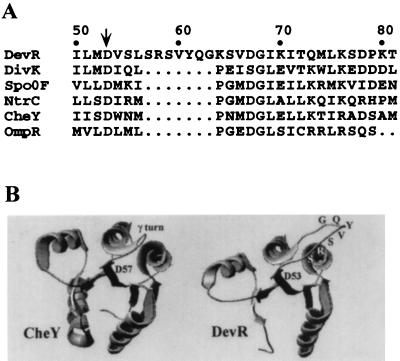

Two-component signal transduction systems play an essential role in the regulation of complex developmental programs in many eubacteria; in filamentous cyanobacteria, three genes with similarity to members of two-component regulatory systems are known to influence heterocyst development. We previously identified a gene in N. punctiforme 29133, designated devR, that is required for heterocyst maturation (6). Strain UCD 311, a devR insertion mutant, synthesizes heterocyst glycolipids but makes a defective heterocyst envelope such that nitrogen fixation occurs only in the absence of oxygen (Fox−). The 135-amino-acid protein encoded by devR is similar to the well-characterized response regulators CheY (25), Spo0F (16), and DivK (21), which lack C-terminal effector domains. DevR differs structurally from other response regulators (27) in having 7 additional amino acids in the highly conserved γ-turn loop region adjacent to the site of phosphorylation (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of DevR to CheY and to other response regulators. (A) Alignment of amino acid residues near the site of phosphorylation (aspartate-53 of DevR; arrow). Numbering of residues of DevR is shown. DevR, N. punctiforme; DivK, Caulobacter crescentus; Spo0F, Bacillus subtilis; NtrC, E. coli; CheY, Salmonella typhimurium; OmpR, E. coli. (B) Ribbon diagrams of CheY (residues 2 to 129) and DevR (residues 1 to 119). The γ turn of CheY and additional amino acids in DevR are indicated, as is the site of phosphorylation in each protein. The PILEUP program of the Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (10) was used to generate sequence alignments. Models of CheY and DevR were prepared with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer (14).

The other two genes involved in heterocyst differentiation that are similar to members of two-component regulatory systems were identified in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. One of these, patA, is a response regulator analog required for the positioning of heterocysts within the filaments (22). When patA is inactivated, heterocysts are found mainly at the ends of the filaments, rather than being intercalary. The other gene, hepK, mentioned above is similar to those encoding histidine kinases (32). Inactivation of hepK in Anabaena strain PCC 7120 results in a Fox− phenotype (11), as does the inactivation of devR in the N. punctiforme mutant strain UCD 311.

In this study, we have used biochemical and genetic approaches to further characterize DevR from N. punctiforme 29133. We show that DevR is phosphorylated in vitro and provide additional evidence for the role of this protein as a response regulator in a phosphorelay system that controls heterocyst maturation.

Sequence analysis of the chromosomal region containing devR.

The sequence of 3.7 kb of DNA adjacent to devR was analyzed to identify genes encoding proteins that might interact with DevR. Three additional open reading frames (designated gyrA, tprN, and regN) were identified; however, none was found to be homologous to genes encoding histidine kinases, response regulators, or other proteins known to interact with components of signal transduction pathways.

In vitro phosphorylation of DevR and stability of DevR-P.

His-tagged versions of DevR were prepared with the pET system of Novagen. His-DevR was made by PCR with primers 5′-ATGAAAACTGTTTTAATTGTCGAAGAC-3′ (upstream) and 5′-CGCGAAGCTTTTATGATTGGCCGTCTGTGG-3′ (downstream) and pSCR166 as the template (Table 1). The downstream primer contained a HindIII site to facilitate directional cloning of the fragment into the expression vector. After digestion with HindIII, the 420-bp fragment containing devR was ligated into the Ecl136II and HindIII sites of pET-28a(+) to generate pSCR342. Primer-mediated PCR mutagenesis (15) was used to generate a sequence encoding His-DevRΔ7, which has a 7-amino-acid deletion in the γ-turn loop region (residues 57 to 63 of DevR [Fig. 1]). Codon 56 was changed from CTG to TTA to introduce a DraI site which was used for screening purposes. Left and right overlapping products, each containing the desired deletion, were first generated in separate reactions with pSCR166 as the template. The inside primers used were 5′-GATTCCATCAACAGATTTTAAAGAAACATCCAT TAAAATCAGGTC-3′ (left) and 5′-CTGATT TTAATGGATGT TTCT TTAAAATCTGT TGATGGAATC-3′ (right), while the outside primers were those used to generate the 420-bp devR fragment above. The left and right PCR products served together as the template in a final reaction with only the outside primers. This amplification yielded a 399-bp fragment, reflecting the 21-bp deletion. It was digested with HindIII and cloned into pET-28a(+) as described above to generate pSCR343. Each fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and purified by affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | Strain BL21 with λDE3 prophage carrying T7 RNA polymerase; used for expression of His-tagged fusion proteins | Novagen |

| N. punctiforme strains | ||

| ATCC 29133 | Wild-type N. punctiforme; Fix+ | 24 |

| UCD 311 | Tn5-1063-induced devR mutant; Fox− | 6 |

| UCD 425 | Wild-type copy of devR replaced by devRD53Q; Fox− | This study |

| UCD 436 | Wild-type copy of devR replaced by devRD53E; Fox− | This study |

| UCD 459 | ATCC 29133 plus pSCR187; Apr | This study |

| UCD 460 | Wild-type copy of hepK replaced by hepK::Ω-npt | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II KS(+) | pUC-derived cloning vector; Apr | Stratagene |

| pET-28a(+) | Expression vector for generation of His6-tagged fusion proteins; Kmr | Novagen |

| pRL271 | Conjugatable suicide vector containing sacB; Emr Cmr | 2 |

| pRL278 | Conjugatable suicide vector containing sacB; Nmr | 2 |

| pSCR202 | N. punctiforme-E. coli shuttle vector; Apr | 26 |

| pSCR166 | 3.15-kb XbaI fragment containing devR in XbaI site of pBluescript II KS(+); Apr | This study |

| pSCR176 | pSCR166 with devR replaced by devRD53Q; Apr | This study |

| pSCR178 | 3.15-kb XbaI fragment from pSCR176 in XbaI site of pRL278; Nmr | This study |

| pSCR179 | 5.2-kb EcoRV fragment containing hepK::Ω-npt in Ecl136II site of pRL271; Nmr Emr Cmr | This study |

| pSCR180 | pSCR166 with devR replaced by devRD53E; Apr | This study |

| pSCR181 | 3.15-kb XbaI fragment from pSCR180 in XbaI site of pRL278; Nmr | This study |

| pSCR187 | 3.15-kb XbaI fragment from pSCR180 in XbaI site of pSCR202; Apr | This study |

| pSCR342 | 420-bp PCR product containing devR in Ecl136II and HindIII sites of pET-28a(+); Kmr | This study |

| pSCR343 | 399-bp PCR product containing devRΔ7 in Ecl136II and HindIII sites of pET-28a(+); Kmr | This study |

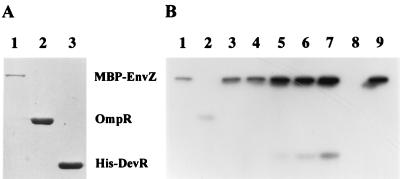

Cross talk between purified histidine kinases and response regulators from different two-component regulatory systems can occur in vitro (18, 23); therefore, we used EnvZ, a histidine kinase involved in osmoregulation in E. coli, to demonstrate that DevR can be phosphorylated (Fig. 2). The purified proteins used in the phosphorylation reactions are shown in Fig. 2A. A standard phosphorylation reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 μM [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci mmol−1; Du Pont NEN). Maltose binding protein (MBP)-EnvZ was added to a final concentration of 1.0 μM, and the mixture was allowed to incubate for 5 min at room temperature. OmpR (20 μM) or His-DevR (35 μM) was then added. Aliquots (7.5 μl) were withdrawn into an equal volume of double-strength sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer at various intervals after addition of the response regulator. All samples were kept on ice and were not heated prior to electrophoresis on 15% acrylamide denaturing protein gels. His-DevR was phosphorylated in the presence of MBP-EnvZ and [γ-32P]ATP (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 7) but not in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP alone (lane 8). As has been noted previously for phosphotransfer between nonpartner proteins (18, 23), phosphotransfer from EnvZ to DevR occurred more slowly and less efficiently than did the transfer of phosphate from EnvZ to its cognate response regulator OmpR (lane 2).

FIG. 2.

Phosphorylation of His-DevR and OmpR by MBP-EnvZ. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel (15% acrylamide) of purified proteins used in phosphorylation assays. Lane 1, MBP-EnvZ; lane 2, OmpR; lane 3, His-DevR. (B) Autoradiogram of SDS-PAGE gel showing phosphorylation of His-DevR. MBP-EnvZ was autophosphorylated when incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for 5 min (lane 1) or 60 min (lane 9). After a 5-min incubation of MBP-EnvZ with [γ-32P]ATP (lanes 2 to 7), OmpR or His-DevR was added. Samples were removed 5 min (OmpR; lane 2) or 1, 5, 15, 30, or 60 min (His-DevR; lanes 3 to 7, respectively) after the addition of the response regulator. In lane 8, His-DevR and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated for 60 min in the absence of MBP-EnvZ.

To assess the stability of phosphorylated DevR, the phosphorylation reaction described above was allowed to proceed for 60 min after the addition of His-DevR. Excess unlabeled ATP (5 mM) was added to render the assay insensitive to subsequent EnvZ kinase activity, and small aliquots were again removed and electrophoresed. Quantitation of radiolabeled bands was performed with a Storm PhosphorImager with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Once phosphorylated, DevR-P appeared to be relatively stable; the amount of DevR-32P decreased exponentially with time with an apparent first-order rate constant of 0.004 to 0.005 min−1, corresponding to a half-life of 2 to 3 h at room temperature.

The fact that an MBP-DevR that we originally purified could not be phosphorylated by MBP-EnvZ implies that the contribution of the affinity tag to the conformation of the fusion protein is critical to its activity. We also considered that the extension of the γ-turn loop in DevR (Fig. 1) might hinder its phosphorylation by heterologous histidine kinases and contribute to the specificity of the cognate histidine kinase. However, MBP-EnvZ failed to phosphorylate His-DevRΔ7 (data not shown) while phosphorylating His-DevR, implying that this region is essential to the conformation of the receiver domain. It remains possible that this loop is involved in recognition of the other substrates with which DevR-P interacts.

Identification of hepK in N. punctiforme 29133 and construction of a hepK mutant strain.

Since mutations in hepK of Anabaena strain PCC 7120 (11) yield a Fox− phenotype, similar to that of devR in N. punctiforme (6), it is possible that HepK is the cognate sensor histidine kinase for DevR. Using the hepK gene from Anabaena strain PCC 7120 as a probe, we identified the N. punctiforme hepK gene in a cosmid library of N. punctiforme 29133 genomic DNA (9). The aligned nucleotide sequences of the two genes are 75% similar, while the translated amino acid sequences are 83% similar (77% identical). An insertion mutation was introduced into N. punctiforme 29133 hepK by ligation of an Ω-npt antibiotic resistance cassette conferring Nmr and Kmr (8) into a unique Eco47III site within the gene. A 5.2-kb EcoRV fragment containing the interrupted gene was cloned into the Ecl136II site of the sacB-containing vector pRL271 (2) to generate pSCR179, and gene replacement was performed as described previously (9). The N. punctiforme 29133 hepK mutant, strain UCD 460, also exhibited a Fox− phenotype. Insoluble inclusion bodies formed when LacZ-HepK and His-HepK fusion proteins were overexpressed in various E. coli strains. Although a soluble protein was produced when HepK lacking N-terminal membrane-spanning regions was fused to MBP, neither this protein nor the insoluble proteins described above were competent in autophosphorylation in our experiments (data not shown); thus, the potential for phosphotransfer from HepK to DevR could not be assessed.

Characterization of N. punctiforme strains with mutations in devR.

Single amino acid substitutions at the site of phosphorylation have been successfully employed to generate response regulator proteins with altered functions. For certain response regulators (e.g., CheY), amino acid substitutions at the site of phosphorylation consistently result in loss of function (3). For others, such as NtrC (19) and OmpR (20), conversion of the amino acid residue at the site of phosphorylation from aspartate to asparagine (NtrC) or from aspartate to glutamine (OmpR) resulted in an inactive protein, but conversion of the same residue to glutamate resulted in a protein that was constitutively active in the absence of phosphorylation. It is likely that the conformational change created by the insertion of the larger, negatively charged glutamate residue mimics the change that normally occurs with phosphorylation, while the conversion of the carboxyl group of aspartate to an amino group simply prevents phosphorylation without inducing a conformational change.

We used a similar strategy to examine the role of phosphorylated DevR in N. punctiforme. PCR mutagenesis and gene replacement were used to generate two N. punctiforme 29133 strains with different mutations in the single chromosomal copy of devR. For each strain, the mutations resulted in a single amino acid substitution at aspartate-53, the putative phosphorylation site of DevR. Sequential PCRs were performed to introduce the necessary base changes at the aspartate (D)-53 codon of devR and to generate a unique downstream BglII site that was useful for screening purposes but did not alter the amino acid sequence of DevR. To construct strain UCD 425, codon 53 of devR was changed from GAT to CAA (D to glutamine [Q]), while codon 59 was changed from AGT to TCT (BglII site). By using pSCR166 as the template with the primers 5′-CCTGCACTAACCTGACTAAGGCATCGT-3′ (left outside), 5′-TGGTAAACAGATCTGGACAGAGAAACTTGCATT-3′ (left inside), 5′-TTAATGCAAGTTTCTCTGTCCAGATCTGTTTAC-3′ (right inside), and 5′-TTATGATTGGCCGTCTGTGGGTAGAAG-3′ (right outside), left and right overlapping PCR products were generated. These were used as template in a final reaction with the two outside primers, which yielded a single 1,034-bp product that contained the desired mutations in devR. Identical steps were taken to generate a similar 1,034-bp PCR product that was used in the construction of strain UCD 436, in which codon 53 was changed from GAT to GAA (D to glutamate [E]) and the BglII site was again introduced. The outside primers used to construct strain UCD 436 were those used in the construction of UCD 425, but the left and right inside primers were changed to 5′ - TGG TAAACAGATC TGGACAGAGAAACTTCCAT T - 3′ and 5′-TTAATGGAAGTTTCTCTGTCCAGATCTGTTTAC-3′, respectively.

Each 1,034-bp PCR product was digested with EcoNI and StyI to obtain a 0.8-kb fragment that was used to replace the corresponding wild-type fragment in pSCR166, forming plasmids pSCR176 (devRD53Q) and pSCR180 (devRD53E). These plasmids were sequenced to confirm that only the correct base changes had been made. The 3.15-kb XbaI fragments from pSCR176 and pSCR180 were cloned into the XbaI site of the sacB-positive selection vector pRL278 (2) to generate plasmids pSCR178 and pSCR181, respectively, which were introduced into N. punctiforme 29133 by conjugation as previously described (9). Cells were plated on medium containing neomycin to select for homologous recombination and integration of the plasmid. Nmr exconjugants were cultured in neomycin-free liquid medium and then plated on neomycin-free medium plus 5% sucrose to select for resolution of the plasmid integrate. Because there was no positive selection for clones that retained the copy of devR bearing the mutations, the following screening method was used to distinguish such clones from those that retained a wild-type copy of the gene. Large single N. punctiforme colonies (containing approximately 6 × 106 cells) were taken from plates, suspended in 0.2 ml of 10 mM Tris-Cl–1 mM EDTA–1% Triton X-100 (pH 8.0), and lysed by heating for 2 min at 95°C. The lysis mixture was then extracted twice with 0.2 ml of chloroform. Aliquots (10 μl) of the aqueous phase, which contained genomic DNA, were used for PCR amplifications with primers designed for sequencing of the devR region. The resulting 1.85-kb PCR product was digested with BglII, and the fragments were separated by electrophoresis. The PCR product from colonies carrying only a mutated copy of devR was cut once by BglII, generating two fragments of 1.1 and 0.75 kb, while the product from colonies with only a wild-type copy of devR lacked the BglII site and was not digested. All three fragments were detected after BglII digestion of the PCR product from Nmr exconjugants containing both a wild-type and a mutated copy of devR.

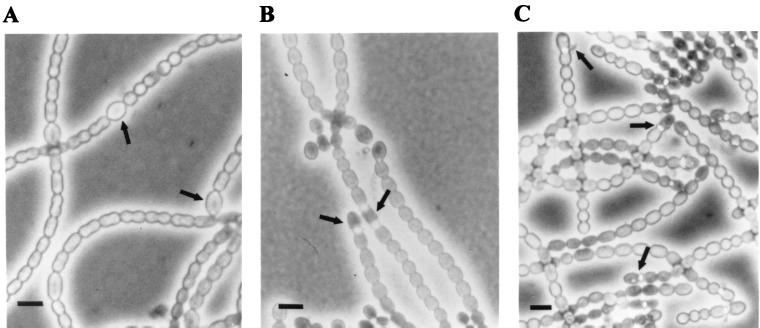

In strain UCD 425, codon 53 of devR was changed to CAA, encoding glutamine; thus phosphorylation at the active site of the mutant protein, DevRD53Q, should no longer be possible. To confirm this, we generated devRD53Q by PCR, with pSCR176 as the template with the same primers used in amplification of wild-type devR. The product was then cloned into pET-28a(+) as described above. Purified His-DevRD53Q was not detectably phosphorylated by MBP-EnvZ (data not shown). Moreover, the phenotype of strain UCD 425 was like that of the devR insertion mutant strain UCD 311; strain UCD 425 grew normally in the presence of combined nitrogen but began to bleach within 24 h after deprivation for combined nitrogen and eventually fragmented into single cells or short (two- to three-cell) filaments. At 48 h, acetylene reduction rates, measured as described previously (7), were essentially zero under oxic conditions but were similar to those for strain UCD 311 under anoxic conditions. As with strain UCD 311, light microscopy showed the accumulation of refractive material at the heterocyst poles and what appeared to be detached outer envelope material at some heterocyst-vegetative cell junctions (Fig. 3). Strain UCD 436, the devRD53E mutant, was morphologically indistinguishable from strain UCD 425 and also expressed a Fox− phenotype with acetylene reduction rates of zero in air.

FIG. 3.

Photomicrographs of N. punctiforme strains taken 48 to 72 h after deprivation for combined nitrogen. (A) N. punctiforme 29133. (B) Strain UCD 311. (C) Strain UCD 436. In contrast to wild-type N. punctiforme 29133, the mutants differentiate heterocysts (indicated with arrows) with large amounts of refractive material at the cell poles. Some heterocysts also appear to have a detached wall layer. Strains UCD 425 (devRD53Q; not shown) and UCD 436 (devRD53E) are morphologically indistinguishable from one another and appear to be phenotypically identical to strain UCD 311, the devR insertion mutant. Bar = 5 μm.

Strain UCD 459 was constructed by introducing devRD53E into wild-type N. punctiforme 29133 on a multicopy plasmid, pSCR187. Overproduction of DevRD53E was confirmed by Western blotting (data not shown). Strain UCD 459 grew in air in the absence of combined nitrogen and differentiated normal-appearing heterocysts. In contrast with our previous results with wild-type DevR (6), overproduction of DevRD53E did not result in the atypical production of heterocysts, akinetes, or hormogonia in ammonium-supplemented medium.

Two different roles are possible for response regulators such as DevR, which lack C-terminal effector domains. Upon phosphorylation, conformational changes that allow the response regulator to interact directly with a downstream target and elicit a response could occur. Alternatively, the response regulator might act only as a phosphotransferase intermediate in a multicomponent phosphorelay. If DevR-P interacts in a direct manner with its downstream target and the substitution of glutamate for aspartate-53 mimics the conformational changes that occur with phosphorylation, the devRD53E mutation could result in a DevR-P constitutive phenotype, which is expected to be similar to that of the wild type. Moreover, overexpression of DevRD53E might result in an aberrant phenotype, such as the atypical akinete production which occurred when wild-type DevR was overexpressed in N. punctiforme 29133 (6). Neither of these phenotypes was observed. If, however, the role of DevR is to act as an intermediate in a phosphorelay system, any amino acid substitution at aspartate-53 (including the substitution of glutamate for aspartate) that prevents phosphorylation and further phosphotransfer would be expected to give rise to the Fox− phenotype exhibited by the transposon-induced mutant UCD 311. In this case, overexpression of the nonfunctional DevRD53E in wild-type N. punctiforme 29133 would be expected to have little or no effect. The results we obtained with strains UCD 425, UCD 436, and UCD 459 clearly demonstrate that aspartate-53 is required for the normal function of DevR and are consistent with the latter hypothesis that the ability of DevR to act as a phosphotransferase is essential to its role in heterocyst maturation.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of N. punctiforme hepK and of the complete open reading frames in the devR region are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession no. L44605 (devR), AF117151 (tprN), AF116873 (regN), and AF114442 (hepK).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Igo (University of California, Davis) for the generous gift of purified MBP-EnvZ and OmpR proteins, and C. P. Wolk (Michigan State University) for kindly providing the Anabaena strain PCC 7120 hepK gene. We also thank E. L. Campbell and F. Wong for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant IBN 95-14787).

REFERENCES

- 1.Black K, Buikema W, Haselkorn R. The hglK gene is required for localization of heterocyst-specific glycolipids in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6440–6448. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6440-6448.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black T A, Cai Y, Wolk C P. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourret R B, Hess J F, Simon M I. Conserved aspartate residues and phosphorylation in signal transduction by the chemotaxis protein CheY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:41–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buikema W J, Haselkorn R. Characterization of a gene controlling heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Genes Dev. 1991;5:321–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell E L, Cohen M F, Meeks J C. A polyketide-synthase-like gene is involved in the synthesis of heterocyst glycolipids in Nostoc punctiforme strain ATCC 29133. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s002030050440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell E L, Hagen K D, Cohen M F, Summers M L, Meeks J C. The devR gene product is characteristic of receivers of two-component regulatory systems and is essential for heterocyst development in the filamentous cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. strain ATCC 29133. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2037–2043. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2037-2043.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell E L, Meeks J C. Evidence for plant-mediated regulation of nitrogenase expression in the Anthoceros-Nostoc symbiotic association. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:473–480. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen M F, Meeks J C. A hormogonium regulating locus, hrmUA, of the cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme strain ATCC 29133 and its response to an extract of a symbiotic plant partner Anthoceros punctatus. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:280–289. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen M F, Wallis J G, Campbell E L, Meeks J C. Transposon mutagenesis of Nostoc sp. strain ATCC 29133, a filamentous cyanobacterium with multiple cellular differentiation alternatives. Microbiology. 1994;140:3233–3240. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux J P, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst A, Black T A, Cai Y, Panoff J-M, Tiwari D N, Wolk C P. Synthesis of nitrogenase in mutants of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 affected in heterocyst development or metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6025-6032.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiedler G, Arnold M, Hannus S, Maldener I. The DevBCA exporter is essential for envelope formation in heterocysts of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1193–1202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frías J E, Flores E, Herrero A. Requirement of the regulatory protein NtcA for the expression of nitrogen assimilation and heterocyst development genes in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:823–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guex N, Peitsch M C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modelling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi R. Recombinant PCR. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch J A. Regulation of the phosphorelay and the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:441–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland D, Wolk C P. Identification and characterization of hetA, a gene that acts early in the process of morphological differentiation of heterocysts. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3131–3137. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3131-3137.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igo M M, Ninfa A J, Stock J B, Silhavy T J. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a bacterial transcriptional activator by a transmembrane receptor. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1725–1734. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klose K E, Weiss D S, Kustu S. Glutamate at the site of phosphorylation of nitrogen-regulatory protein NtrC mimics aspartyl-phosphate and activates the protein. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:67–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan C-Y, Igo M M. Differential expression of the OmpF and OmpC porin proteins in Escherichia coli K-12 depends upon the level of active OmpR. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:171–174. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.171-174.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane T, Benson A, Hecht G B, Burton G J, Newton A. Switches and signal transduction networks in the Caulobacter crescentus cell cycle. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 403–417. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang J, Scappino L, Haselkorn R. The patA gene product, which contains a region similar to CheY of Escherichia coli, controls heterocyst pattern formation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5655–5659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ninfa A J, Ninfa E G, Lupas A N, Stock A, Magasanik B, Stock J. Crosstalk between bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction proteins and regulators of transcription of the Ntr regulon: evidence that nitrogen assimilation and chemotaxis are controlled by a common phosphotransfer mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5492–5496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock J B, Ninfa A J, Stock A M. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summers M L, Wallis J G, Campbell E L, Meeks J C. Genetic evidence of a major role for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in nitrogen fixation and dark growth of the cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. strain ATCC 29133. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6184–6194. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6184-6194.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volz K. Structural conservation in the CheY superfamily. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11741–11753. doi: 10.1021/bi00095a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsby A E. The permeability of heterocysts to the gases nitrogen and oxygen. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B. 1985;226:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei T-F, Ramasubramanian T S, Golden J W. Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 ntcA gene required for growth on nitrate and heterocyst development. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4473–4482. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4473-4482.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolk C P, Ernst A, Elhai J. Heterocyst metabolism and development. In: Bryant D A, editor. The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 769–823. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou R, Wei X, Jiang N, Li H, Dong Y, Hsi K L, Zhao J. Evidence that HetR protein is an unusual serine-type protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4959–4963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu J, Kong R, Wolk C P. Regulation of hepA of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 by elements 5′ from the gene and by hepK. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4233–4242. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4233-4242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]