Abstract

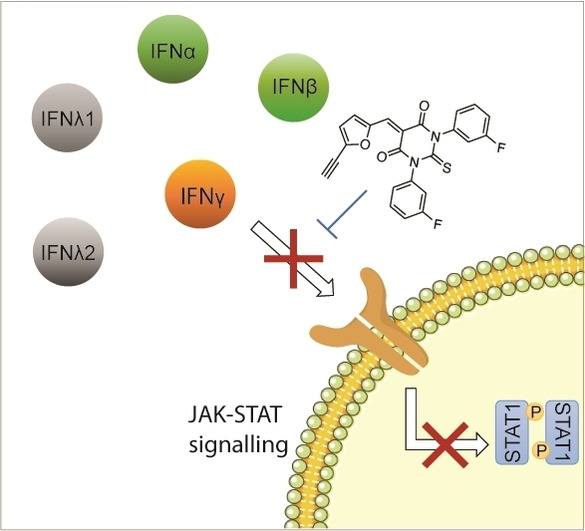

Interferons (IFN) are cytokines which, upon binding to cell surface receptors, trigger a series of downstream biochemical events including Janus Kinase (JAK) activation, phosphorylation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription protein (STAT), translocation of pSTAT to the nucleus and transcriptional activation. Dysregulated IFN signalling has been linked to cancer progression and auto‐immune diseases. Here, we report the serendipitous discovery of a small molecule that blocks IFNγ activation of JAK‐STAT signalling. Further lead optimisation gave rise to a potent and more selective analogue that exerts its activity by a mechanism consistent with direct IFNγ targeting in vitro, which reduces bleeding in model of haemorrhagic colitis in vivo. This first‐in‐class small molecule also inhibits type I and III IFN‐induced STAT phosphorylation in vitro. Our work provides the basis for the development of pan‐IFN inhibitory drugs.

Keywords: Formin, Interferon, JAK-STAT Signalling, SMIFH2, Small Molecule

A small molecule that inhibits IFN‐induced JAK‐STAT signalling is reported. Chemical synthesis led to a series of more effective analogues that can selectively inhibit either IFN‐signalling or formin‐mediated actin assembly.

Interferons (IFNs) are pleiotropic cytokines that play key roles in immunity for host defence against pathogens and tumour control. [1] IFN binding to the type I and type II IFN receptors triggers a downstream activation of the canonical Janus Kinase (JAK)‐Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription protein (STAT) signalling pathway, and its dysregulation has been involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and cancer. [2] Thus, targeting IFN signalling represents an attractive therapeutic strategy. Currently, the most effective approach to block JAK‐STAT signalling is based on JAK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Jakinibs). [3] These small molecules have shown promising results for the treatment of dysregulated immune responses in various pathologies. [4] However, since JAK tyrosine kinase can be activated by distinct cytokines and growth factors, current inhibitors block the signalling downstream of these inducers without specificity, which can adversely affect other important physiological processes. [5] Another strategy is based on direct IFN targeting with monoclonal antibodies. The moderate efficacy of anti‐IFNγ monoclonal antibody‐emapalumab has however prevented marketing authorisation in Europe for the treatment of primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), which is characterised by excess production of cytokines including IFNγ. [6] Developing selective inhibitors of IFN‐activated JAK‐STAT signalling remains a worthy and challenging endeavour. Such pharmacological tools enable to dissect the complex biology of IFN in various settings and can lead to the development of new therapeutics for the treatment of cancers and autoimmune diseases. [7]

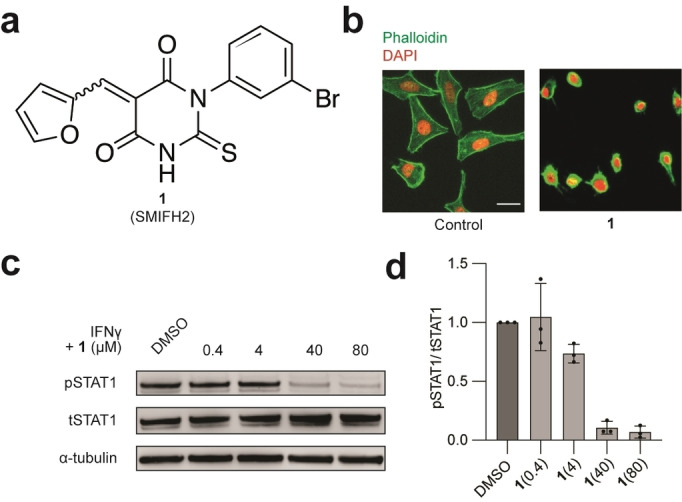

We have previously reported that dynamic plasma membrane partitioning of IFNγ receptor (IFNγR) within lipid nanodomains is required for the catalytic activation of JAK. [8] Here, we set out to further dissect the fine details of JAK‐STAT signalling induced by IFNγ, considering the recently proposed role of actin in lipid nanodomain organization. [9] To this end, we investigated the effect of SMIFH2 (1), an inhibitor of filamentous actin nucleator formins (Figure 1a). [10] Formins are a family of proteins involved in the linear elongation of actin filaments. [11] Consistent with the role of formins in the regulation of actin nucleation, 1 inhibited actin assembly as monitored by fluorescence imaging of phalloidin staining (Figure 1b). Importantly, 1 also antagonised type II IFN signalling, as shown by the strong reduction of IFNγ‐induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 (pSTAT1) (Figure 1c, d). The fact that 1 completely inhibited STAT1 phosphorylation raised a putative mechanism whereby 1 inhibits JAK‐STAT signalling by engaging a biological target other than formins.

Figure 1.

a) Molecular structure of 1. b) Fluorescence microscopy images of HeLa cells treated with 1 (40 μM) for 20 min and stained with phalloidin and DAPI, Scale bar=30 μm. n=3 independent experiments. c) Immunoblot analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells treated with IFNγ (1000 U mL−1, 20 min), that was preincubated with 1 for 20 min. d) Quantification of pSTAT1/tSTAT1 of the immunoblot in c. n=3 independent experiments.

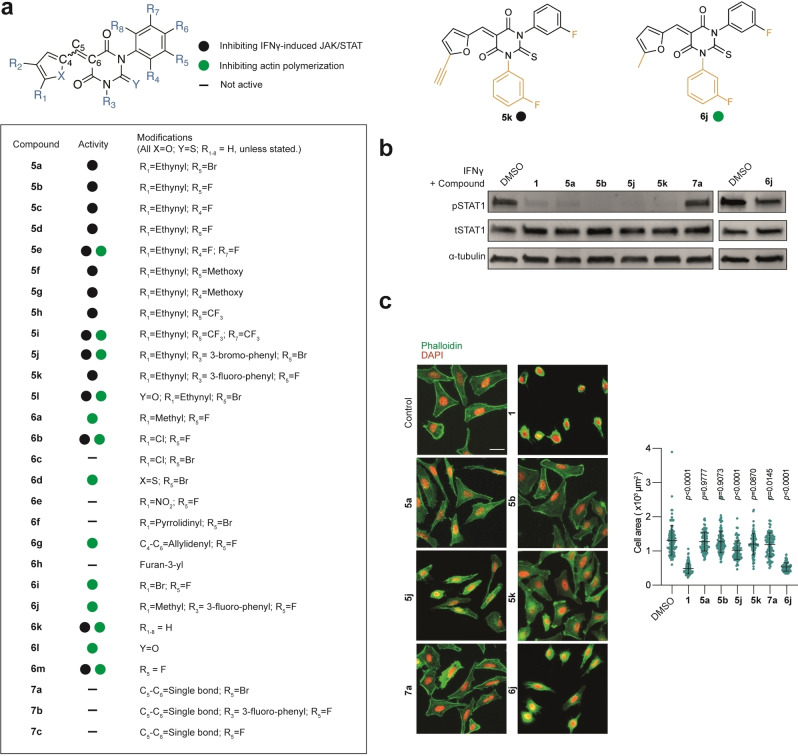

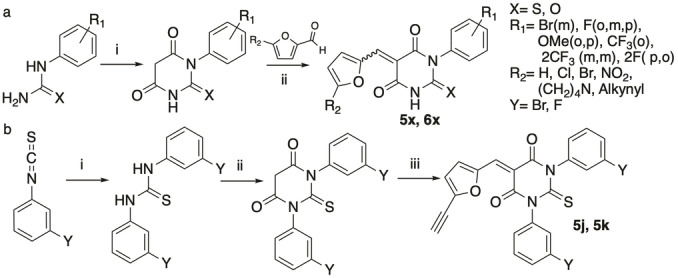

To delineate the mechanisms at work, we aimed to synthesise structural variants of 1 to uncouple the inhibitory effect against IFNγ from that linked to formin targeting. The convergent synthetic scheme leading to 1 is such that it enables the sequential modification of each position of the scaffold, which is required to establish a structure–activity relationship and to provide more potent and selective analogues. Thus, we prepared a library of 28 structural variants where each position was studied individually and combinatorically (Figure 2a). We synthesised analogues where the furane ring was functionalised with apolar alkyne or methyl groups, electron‐withdrawing groups, such as chlorine and nitro, or an electron‐donating substituent, such as pyrrolidine. We also explored the effect of replacing the furane ring by a less polar thiophene. The thiobarbiturate core was replaced by a barbiturate, which can potentially enhance the solubility in aqueous media. The aromatic ring was also altered varying both the nature and position of substituents, including fluorine, trifluoromethyl and methoxy, expected to alter the electron density of the aromatic ring as well as the overall solubility of these analogues. We introduced fluorine, which is extensively found in clinically approved drugs due to the stability of C−F bond that can impact on drug metabolism and thus, increase their half‐life. Furthermore, it enables the study of small molecule–target interactions by 19F NMR and to trace the distribution of drugs by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. [12] It is noteworthy that the Knoevenagel condensation used for the synthesis of these analogues leads to a mixture of E/Z stereoisomers following the final dehydration step. We reasoned that using symmetrical thiobarbiturates would enable the production of a mixture of stereoisomers, which upon dehydration would lead to a single product (Scheme 1). This was an important feature of our synthetic planning as using a mixture of isomers precludes the establishment of a robust mechanism of action (MoA) and represents a significant limitation for the development of drugs for clinical use. Lastly, we synthesised other analogues either lacking the α,β‐unsaturated C−C bond or containing an additional contiguous unsaturation. The synthesis of these additional compounds was prompted by the idea that 1 might exert its activity through the formation of a covalent adduct through a 1,4‐addition involving nucleophilic residues of biological targets.

Figure 2.

a) Molecular structures of analogues of 1 (full structures depicted Figure S3). b) IFNγ activity monitored by immunoblot analysis of pSTAT1 and tSTAT1 levels in HeLa cells treated with IFNγ (1000 U mL−1, 20 min) that was preincubated with small molecules (40 μM) for 20 min as indicated. n=3 independent experiments. c) Actin polymerization activity performed using fluorescence microscopy. Images of HeLa cells treated with small molecules (40 μM) for 20 min and stained for actin with phalloidin. Scale bar=30 μm. Quantification of cell area. Mean value±SD. Statistical analysis with one‐way ANOVA. n=3 independent experiments. Panels b and c are duplicated in Figures S1a and S2a to compare with all the synthesised compounds.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic strategy. a) i) Diethyl malonate, NaOMe, n‐PrOH, reflux (105 °C) overnight, 52–99 %. ii) MeOH, pyridine cat., 60 °C, 2 h; or H2O, reflux, 1 h (K2CO3, MeOH, r.t., 2 h when TMS‐alkynyl is used); or AcOH, 15–60 min, 7–25 %. b) i) 1) 3‐Fluoro‐/Bromoaniline, 20 min mechanical mixing, 61–74 %. ii) Malonic acid, POCl3, CHCl3, reflux, 48 h, 60–70 %. iii) 5‐((Trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)furan‐2‐carbaldehyde, H2O, reflux, 1 h then, K2CO3, MeOH, r.t., 2 h, 13 %.

Next, these analogues were evaluated for their capacity to inhibit IFNγ‐induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 by western blotting and to alter actin assembly, monitoring phalloidin staining as well as measuring cell area, which is reduced in cells with impaired actin networks. Using HeLa cells as a suitable model to study IFNγ‐signalling, [13] we found that most analogues containing a terminal alkyne on the furane ring, including 5 a, inhibited IFNγ‐induced pSTAT1 but were deprived of formin targeting according to the phalloidin pattern and overall cell area that remained unaffected (Figures 2b, c and S1–S3). This indicated that inhibition of IFNγ‐signalling occurs independently of formin targeting. Conversely, compounds containing a furane ring functionalized with chlorine, nitro or pyrrolidine substituents, analogue 6 h containing a furane ring attached to the thiobarbiturate core at a different position, compound 6 d containing a thiophene instead of the furane, or 6 l with a barbiturate core did not inhibit IFNγ‐signalling. Additionally, analogues lacking α,β‐unsaturated C−C bond such as 7 a did not show any activity against IFNγ‐signalling or actin assembly, suggesting that putative biological targets may covalently react with the inhibitors. Furthermore, we found that varying the nature and positions of the substituents on the aromatic ring was tolerated with no loss of activity. Interestingly, using symmetrical thiobarbiturates yielded biologically active compounds such as 5 j and 5 k, enabling us to investigate IFNγ‐signalling using pure products as opposed to mixture of stereoisomers.

Thus, this synthetic strategy afforded a series of biologically active compounds, whose structure are inherently refractory to giving rise to distinct isomers upon rehydration/dehydration in biological settings. Surprisingly, the alkyne‐containing barbiturate 5 l retained its activity against both IFNγ‐signalling and formin, whereas 6 l did not inhibit the former and all the other alkyne analogues were deprived of formin inhibitory properties. Furthermore, compounds 6 a, 6 b, and 6 i containing furane rings functionalised at the same position but with distinct substituents inhibited either IFNγ‐signalling or formins, showing that subtle modifications of the furane ring drastically impact on potential inhibitory effect. Nevertheless, this synthetic route allowed us to produce biologically active pure products such as 5 k and 6 j that can target either IFNγ‐signalling or the formins, respectively, as well as negative controls 7 a and 7 b. Next, we explored the capacity of a subset of analogues to inhibit IFNγ‐signalling selectively. We found that compounds 5 a, 5 b, 5 j and 5 k inhibited phosphorylation of STAT in a dose‐dependent manner in the nanomolar and low micromolar range with 5 k and 5 b being more potent, although 5 b was used as a mixture of stereoisomers (Figure S4a, b). Importantly, these compounds did not show significant cytotoxicity at effective doses (Figure S4c, d). Consistent with IFNγ‐signalling inhibition, 5 k also inhibited the phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 (Figure S4e, f).

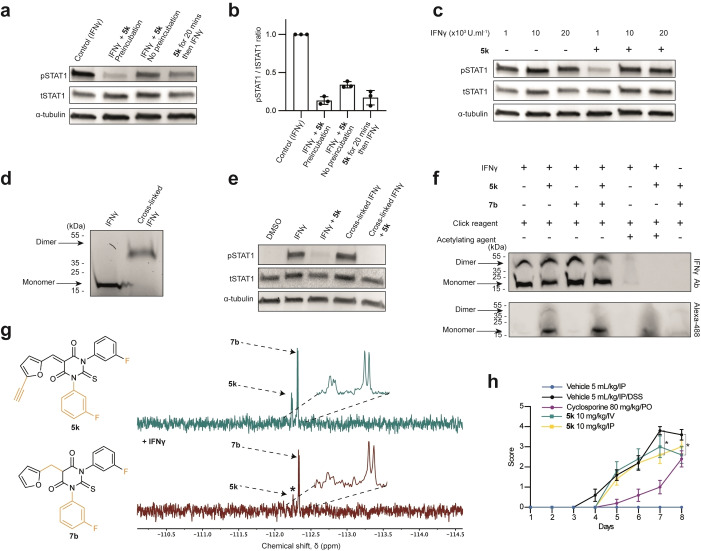

We next studied the MoA underlying IFNγ‐signalling inhibition using 5 k. Interestingly, we found that preincubating 5 k with IFNγ 20 min prior to addition of this mixture to cells led to superior inhibitory activity compared to treating cells with the compound and cytokine sequentially, suggesting that inhibition may be the result of a direct targeting of IFNγ (Figure 3a, b). This contention was further supported by the fact that using higher concentrations of IFNγ while keeping the dose of 5 k constant, overcame the inhibitory activity of the compound (Figure 3c). Given that IFNγ triggers a signalling response as a homodimer bound to its receptor, we interrogated the capacity of 5 k to inhibit IFNγ dimerization. To this end, we cross‐linked IFNγ using bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) following a previously established procedure, [14] where the resulting cross‐linked IFNγ homodimer remains biologically active (Figure 3d). Compound 5 k prevented IFNγ‐signalling induced by the cross‐linked dimer indicating that this analogue does not exert its activity by preventing IFNγ dimerization (Figure 3e). This data suggested instead that it might block binding to IFNγR by targeting a specific residue of IFNγ.

Figure 3.

a) Immunoblot analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells treated either with IFNγ (1000 U mL−1, 20 min) that was preincubated with 5 k for 20 min prior cell treatment, or IFNγ and 5 k incubated simultaneously, or IFNγ added to cells 20 min after treatment with 5 k as indicated. n=3 independent experiments. b) pSTAT1/tSTAT1 quantification of the immunoblot in (a). c) Immunoblot analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells treated with various concentrations of IFNγ (20 min) that was preincubated with 5 k for 20 min as indicated. n=3 independent experiments. d) Immunoblot of IFNγ on denaturing gel before and after cross‐linking using BS3. e) Immunoblot analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells treated either with IFNγ (1000 U mL−1, 20 min) or cross‐linked IFNγ (1000 U mL−1) that was preincubated with 5 k as indicated. n=3 independent experiments. f) Immunoblot of IFNγ (3.55 μM) preincubated with analogues 5 k (20 equiv) or 7 b (20 equiv), and acetic anhydride as indicated prior to reaction with Alexa‐488‐azide analysed on native gel. n=3 independent experiments. g) Expanded region of 19F NMR spectra (471 MHz, 37 °C). R2 filter spectra recorded with proton decoupling for mixture of analogue 5 k and non‐active analogue 7 b before (green) and after (red) IFNγ addition. * signal that is reduced in intensity in the presence of the protein. h) Acute model of DSS‐induced colitis in C57BL/6 mice. Colorectal bleeding score (mean+/−SEM). Statistical analysis by two‐way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test. * p<0.05.

Next, we studied the capacity of 5 k to form covalent adducts with nucleophiles including lysine and serine. This was based on the rationale that IFNγ contains many such nucleophilic residues susceptible to cross react via a 1,4‐addition on the Michael acceptor (Figures S5a, b). Interestingly, UPLC‐MS analysis revealed that 5 k can form an adduct with a free lysine residue, whereas no adduct could be detected using a free serine, which was consistent with the superior nucleophilicity of primary amines compared to primary alcohols, although these experiments were conducted using single amino acids devoid of the complex structure of the full protein that may impact on the reactivity of these residues (Figures S5c, d). Identifying adducts formed upon reaction of IFNγ with 5 k by mass spectrometry was proven challenging and may reflect the reversible nature of 1,4‐additions, involving Michael acceptors as well as the stability of such an adduct subjected to stringent experimental conditions employed in mass spectrometry analyses. To further substantiate a direct binding of 5 k to IFNγ, we took advantage of the alkyne moiety of 5 k to detect this small molecule bound to IFNγ on native gels by means bio‐orthogonal labelling using previously reported procedures. [15]

Labelling 5 k on gel by means of click chemistry revealed bands, which correspond to IFNγ, whereas no staining was detected in control conditions (Figure 3f). Adding biologically inactive 7 b to a mixture of IFNγ‐5 k did not alter the signal of labelled 5 k. Additionally, pre‐treating IFNγ with acetic anhydride to acetylate nucleophilic residues of IFNγ reduced the signal of labelled 5 k in a dose dependent manner (Figure 3f and Figure S5e‐h). This supported the notion that 5 k can chemically react with the protein target. Then, we explored the capacity of 5 k to interact with IFNγ by 19F NMR spectroscopy using a Carr–Purcell–Meiboom‐Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence. [12b] We analysed 19F signals of biologically active compounds 5 k mixed with that of the biologically inactive analogue 7 b lacking the α,β‐unsaturation, which is not prone to form a covalent adduct with IFNγ. Importantly, the 19F signals of each analogue could be resolved and unequivocally assigned by NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3g). Consistent with a preferential interaction of IFNγ with 5 k, the two 19F signals of 5 k were reduced upon addition of IFNγ whereas that of 7 b remained unchanged. Finally, we investigated the specificity of our compound towards other IFN types namely type I–IFNα2a, IFNα2b and IFNβ, and type III–IFNλ1 and IFNλ2, and Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), a growth factor that does not belong to the IFN family. At low micromolar concentrations of 5 k and 1, IFN‐induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 were inhibited whereas no significant effect was observed on STAT1 activation by EGF (Figure S6a‐j). This suggests a broad‐spectrum applicability of 5 k as a pan‐IFN inhibitor.

Next, we evaluated the effect of 5 k on a murine model of haemorrhagic colitis termed DSS‐IBD (Dextran Sulphate Sodium‐Inflammatory Bowel Disease), since IFNγ has been proposed to promote bleeding in IBD. [16] We first evaluated the maximum tolerated dose of 5 k in vivo as well as its pharmacodynamics properties. No adverse clinical sign was observed at 15 mg kg−1 when administered intravenously (IV) and the compound moderately reduced the activity of mice when administered intraperitoneally (IP). Furthermore, the compound exhibited a half‐life of 3.6 h when administered by IV and a bioavailability of 80 % measured 2 h following IP administration (Figure S7a). Mice were treated with DSS and clinical monitoring was performed over the following 8 days. While 5 k did not significantly improve the clinical index (Figure S7b), it significantly reduced the bleeding to a similar extent compared to the positive control treatment cyclosporin (Figure 3h), which suggested that 5 k can bind to and inactivate IFNγ in vivo.

In conclusion, we identified a small molecule that inhibits IFN‐induced JAK‐STAT activation, a signalling pathway upregulated in many diseases including inflammatory and auto‐immune diseases as well as a subset of cancers. We produced new structures that inhibit either IFN‐mediated JAK‐STAT signalling or formin‐mediated actin assembly. Furthermore, our synthetic strategy readily afforded single reaction products suitable for biological intervention. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the fine details of the inhibitory properties of these compounds. Identifying the amino acid residues of IFN types susceptible to form a bond with these compounds and understanding how this interferes with the interaction of IFN to its receptor will be crucial to further improve the design of these small molecules. Nevertheless, the selective inhibitory profile of the compounds described in this study illustrates their potential as molecular probes to investigate IFN‐signalling as well as biological processes reliant on formins and actin assembly. The encouraging results observed in vivo pave the way towards the development of new therapeutics with unprecedented MoA.

Conflict of interest

Institut Curie and the CNRS filed a patent application on the compounds described herein and their therapeutic use.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank funding organisations—the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant agreement No 647973 (R.R.), the Foundation Charles Defforey‐Institut de France (R.R.), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (C.M.B., C.L.‐ANR‐NanoGammaR‐15‐CE11‐0025‐01; F.E.S., G.S.B.‐ANR‐10‐IAHU‐01; F.E.S.‐ANR‐18‐CE15‐0017), Fondation ARC (C.M.B.; F.E.J.; S.M.), Ligue Contre le Cancer Equipe Labellisée (R.R.) and Region IdF for NMR infrastructure (R.R.). This work is also supported by the labex CelTisPhyBio 11‐LBX‐0038, Institut Curie and CNRS Innovation. The authors are grateful to the Cell and Tissue Imaging Platform (PICT‐IBiSA), Institut Curie, member of the French National Research Infrastructure France‐BioImaging (ANR10‐INBS‐04). The authors also acknowledge Ludovic Colombeau, Sebastian Müller, Tatiana Cañeque and Fabien Sindikubwabo for helpful discussions.

L. K. Thoidingjam, C. M. Blouin, C. Gaillet, A. Brion, S. Solier, S. Niyomchon, A. El Marjou, S. Mouasni, F. E. Sepulveda, G. de Saint Basile, C. Lamaze, R. Rodriguez, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205231; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202205231.

Contributor Information

Dr. Cédric M. Blouin, Email: cedric.blouin@curie.fr.

Dr. Christophe Lamaze, Email: christophe.lamaze@curie.fr.

Dr. Raphaël Rodriguez, Email: raphael.rodriguez@curie.fr.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1. Blouin C. M., Lamaze C., Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benci J. L., Xu B., Qiu Y., Wu T. J., Dada H., Twyman-Saint Victor C., Cucolo L., Lee D. S. M., Pauken K. E., Huang A. C., Gangadhar T. C., Amaravadi R. K., Schuchter L. M., Feldman M. D., Ishwaran H., Vonderheide R. H., Maity A., Wherry E. J., Minn A. J., Cell 2016, 167, 1540–1554 e1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villarino A. V., Kanno Y., O'Shea J. J., Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kontzias A., Kotlyar A., Laurence A., Changelian P., O′Shea J. J., Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 464–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banerjee S., Biehl A., Gadina M., Hasni S., Schwartz D. M., Drugs 2017, 77, 521–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Hatterer E., Richard F., Malinge P., Sergé A., Startchick S., Kosco-Vilbois M., Deehan M., Ferlin W., Guilhot F., Cytokine 2012, 59, 570; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/gamifant.

- 7.

- 7a. Gurzov E. N., Stanley W. J., Pappas E. G., Thomas H. E., Gough D. J., FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3002–3015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Hu X., Ivashkiv L. B., Immunity 2009, 31, 539–550; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Ivashkiv L. B., Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 545–558; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Schreiber R. D., Old L. J., Smyth M. J., Science 2011, 331, 1565–1570; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7e. Thomas S. J., Snowden J. A., Zeidler M. P., Danson S. J., Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 365–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blouin C. M., Hamon Y., Gonnord P., Boularan C., Kagan J., Viaris de Lesegno C., Ruez R., Mailfert S., Bertaux N., Loew D., Wunder C., Johannes L., Vogt G., Contreras F. X., Marguet D., Casanova J. L., Gales C., He H. T., Lamaze C., Cell 2016, 166, 920–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalappurakkal J. M., Anilkumar A. A., Patra C., van Zanten T. S., Sheetz M. P., Mayor S., Cell 2019, 177, 1738–1756 e1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rizvi S. A., Neidt E. M., Cui J., Feiger Z., Skau C. T., Gardel M. L., Kozmin S. A., Kovar D. R., Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 1158–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breitsprecher D., Goode B. L., J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Matthews P. M., Rabiner E. A., Passchier J., Gunn R. N., Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 175–186; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Vulpetti A., Hommel U., Landrum G., Lewis R., Dalvit C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12949–12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marchetti M., Monier M. N., Fradagrada A., Mitchell K., Baychelier F., Eid P., Johannes L., Lamaze C., Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 2896–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fountoulakis M., Juranville J. F., Maris A., Ozmen L., Garotta G., J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 19758–19767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Speers A. E., Cravatt B. F., Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Langer V., Vivi E., Regensburger D., Winkler T. H., Waldner M. J., Rath T., Schmid B., Skottke L., Lee S., Jeon N. L., Wohlfahrt T., Kramer V., Tripal P., Schumann M., Kersting S., Handtrack C., Geppert C. I., Suchowski K., Adams R. H., Becker C., Ramming A., Naschberger E., Britzen-Laurent N., Sturzl M., J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 4691–4707; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Salas A., Hernandez-Rocha C., Duijvestein M., Faubion W., McGovern D., Vermeire S., Vetrano S., Vande Casteele N., Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.