Abstract

Viral infections are a major cause of severe, fatal diseases worldwide. Recently, these infections have increased due to demanding contextual circumstances, such as environmental changes, increased migration of people and product distribution, rapid demographic changes, and outbreaks of novel viruses, including the COVID-19 outbreak. Internal variables that influence viral immunity have received attention along with these external causes to avert such novel viral outbreaks. The gastrointestinal microbiome (GIM), particularly the present probiotics, plays a vital role in the host immune system by mediating host protective immunity and acting as an immune regulator. Bacteriocins possess numerous health benefits and exhibit antagonistic activity against enteric pathogens and immunobiotics, thereby inhibiting viral infections. Moreover, disrupting the homeostasis of the GIM/host immune system negatively affects viral immunity. The interactions between bacteriocins and infectious viruses, particularly in COVID-19, through improved host immunity and physiology are complex and have not yet been studied, although several studies have proven that bacteriocins influence the outcomes of viral infections. However, the complex transmission to the affected sites and siRNA defense against nuclease digestion lead to challenging clinical trials. Additionally, bacteriocins are well known for their biofunctional properties and underlying mechanisms in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. However, few studies have shown the role of probiotics-derived bacteriocin against viral infections. Thus, based on the results of the previous studies, this review lays out a road map for future studies on bacteriocins for treating viral infections.

Keywords: antiviral immunity, bacteriocin, immune interaction, immunomodulatory, probiotics, viral infection

Introduction

Viral infections are the primary cause of numerous diseases and deaths (Villena et al., 2020). These infections affect several tissues and organs, such as the colon (e.g., rotavirus), upper respiratory tract and lungs (e.g., rhinovirus and influenza), liver (e.g., hepatitis B virus), leukocytes [e.g., human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)], spinal cord (e.g., poliovirus), and vascular endothelial cells (e.g., Ebola; Dreyer et al., 2019; Weeks and Chikindas, 2019; Foysal et al., 2020; Jenab et al., 2020; Villena et al., 2020). Some viruses are more vulnerable to extreme conditions because of a weakened immune system. Histological examinations of patients with viral infections revealed severe destruction of tissue structure, resulting in their death (Jayawardena et al., 2020).

Previous studies have investigated various sources of antimicrobial agents from natural plants. Numerous antiviral agents have been proposed and verified as therapeutic targets in viral drugs (Muhammad et al., 2018; Umair et al., 2020, 2022; Riaz Rajoka et al., 2021; Senan et al., 2021; Youssef et al., 2021; Rajoka et al., 2022). Several treatments act as effective tools in viral infections, such as gene therapy; administration of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, pegylated interferon-α (IFN-α), and ribavirin; recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) antagonist treatment; and highly active antiretroviral therapy, which includes multiple antiretroviral agents; or a combination of these therapies (Lehtoranta et al., 2020; Lopez-Santamarina et al., 2020). However, viral genome mutations are lethal for viral replication and cause viral resistance to the adopted antiviral therapies. Therefore, it is necessary to provide other preventive or supplementary interventions.

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a complex ecosystem hosting millions of resident microorganisms, known as the gut microbiota (GM; Libertucci and Young, 2019). The microbiome consists of microorganisms and their genetic material and plays an essential role in host physiology and metabolism by supplying genetic elements absent in the host genome (Hall et al., 2017). Additionally, a strong correlation exists between COVID-19 infection and the GM community (Chen et al., 2020). Further, it has been reported that patients with COVID-19 demonstrate a reduced number of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium due to intestinal microbial dysbiosis (Chen et al., 2020).

In particular, when probiotics, the “cultured” (living) microorganisms beneficial to the host, are ingested in adequate amounts (Quilodrán-Vega et al., 2020; El-Saadony et al., 2021) as a compliment or element inherent in food, they principally improve the GM composition (Minj et al., 2021), treat dysbiosis, and prevent viral diseases (Hill et al., 2014). Notably, bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides produced by significant bacterial cell lines (Khalil et al., 2022; Le Morvan De Sequeira et al., 2022; Naseef et al., 2022). Additionally, these bacteriocins modulate the systemic immune and mucosal systems of humans and animals, protecting them from several viral infections (Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020).

However, the interactions between viral diseases and the immunity induced by probiotics remain unknown, including the mechanism of the reported antiviral activity of probiotics. Moreover, proteolytic enzymes degrade bacteriocins, causing their instability in different body parts, such as the GIT, serum, liver, and kidneys, thus limiting their industrial applications (Weeks and Chikindas, 2019). Given these considerations, the present review provides a comprehensive overview of the role of the probiotics-based bacteriocin as an immune-modulating agent in combating viral infections, its stability in the GIT microbiota, and the bacteriocin mechanisms of immune modulation. Furthermore, the evolving zoonotic viruses and their animal reservoirs for viral progenitors will be described in this study, including the viral transmission route from animal to human, focusing on the most recent published studies.

Probiotics as Immunobiotics

In general, eukaryotic hosts have a high bacterial load, predominantly habituating GIT (Bibi et al., 2021; Youssef et al., 2021; Rajoka et al., 2022). However, some of these microorganisms are currently susceptible to pathogenesis (Round and Mazmanian, 2009). Therapeutic antibiotics occasionally disrupt the intestinal microbiota, which subsequently initiate microbial pathogenesis (Foysal et al., 2020).

Probiotics are heat- and pH-stable, colorless, odorless, and tasteless, which indicate their suitability in food applications. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and bifidobacteria are the most commonly used probiotic bacteria. LAB essentially preserves the integrity of the human gut wall and maintains a healthy microbiome, including the inhibition of gut pathogen proliferation. Other genera, such as enterococci, and yeast, such as Saccharomyces, have been proposed and exploited as probiotic agents (Ou et al., 2019; Jaffar and Zailan, 2021; Lai et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022).

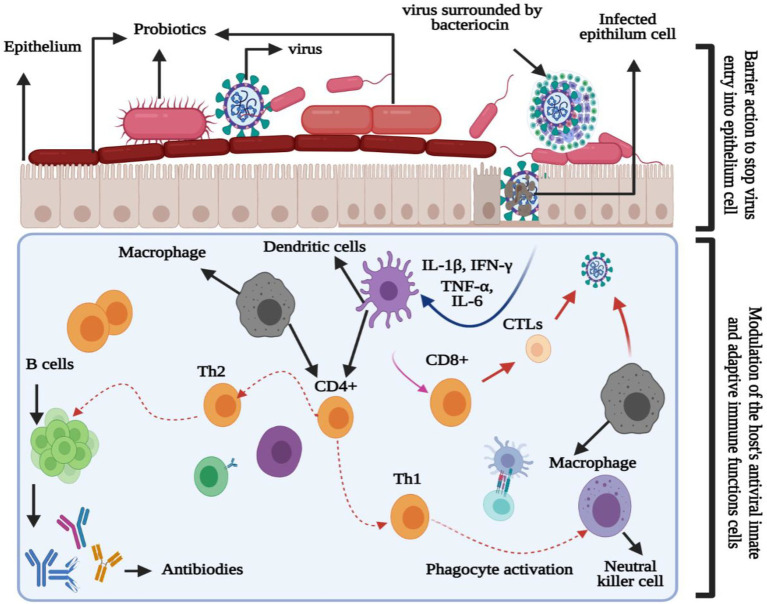

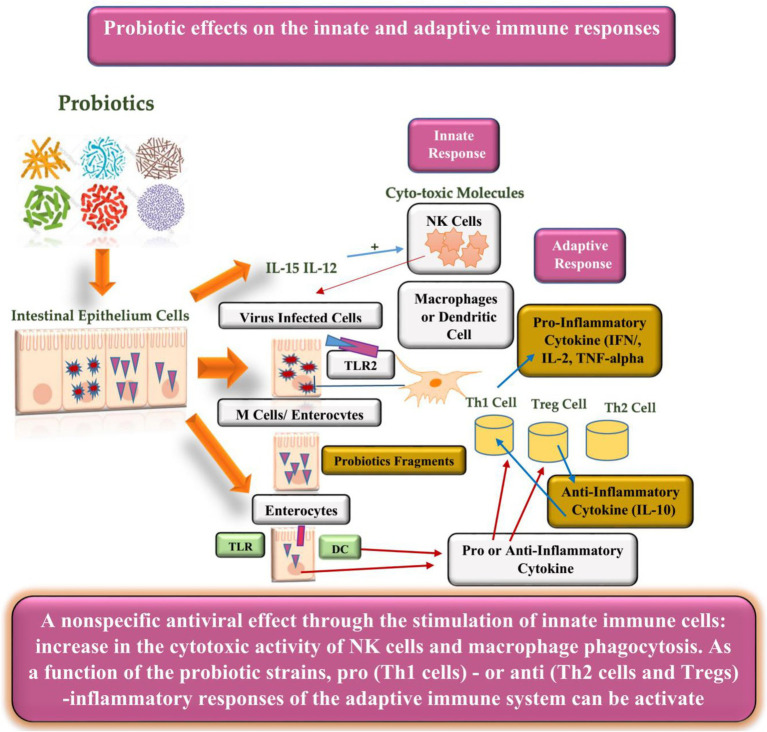

Probiotics have the potential for lowering lactose and cholesterol levels, cancer prevention, and lowering the risk of secondary infections (Li et al., 2021). Another benefit of probiotics is their immunobiotic nature in modulating or enhancing the immune (mucosal) system. As viruses are in direct contact with the mucosal (respiratory, genital, or gastrointestinal) surfaces, they must overcome three lines of defense: (1) the mucus coat, (2) innate, and (3) adaptive immune responses. Therefore, probiotics interfere with the viruses directly or indirectly to improve their phagocytosis (Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020). The direct response can be subcategorized into two stages (Figure 1): barrier activity toward viral particles before entering the epithelial cells and the modulation of the host antiviral immune response. Moreover, the barrier activity toward viruses includes (1) enhanced mucosal barrier activity, (2) direct probiotic-virus association, (3) secretion of antiviral inhibitory metabolites (bacteriocins), and (4) inhibition of viral attachment to host cells (Belguesmia et al., 2020). Additionally, the effects of probiotic modulation on the immune cells can be observed in lymphocytes, hematopoietic stem cells, T cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells (DCs; Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020; Belguesmia et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Figure 2 illustrates the innate and adaptive antiviral reaction mechanisms and immunomodulatory effects of probiotics to improve viral phagocytosis (Belguesmia et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Immunomodulatory properties of probiotics for enhancing phagocytosis against the virus.

Figure 2.

Probiotics and innate and adaptive immune interaction against viral infections.

Probiotics indirectly interfere with the virus by (1) altering the condition of the cells, (2) enhancing or suppressing innate and adaptive immunity through the associated molecular signaling pathways, (3) protecting themselves against viral particles that compete for cell-surface adhesion, (4) reducing inflammatory processes by controlling innate immunity through Toll-like receptors and other signaling pathways, and (5) producing antiadhesive substances against the viruses. Thus, probiotics prevent its adhesion to the host cell receptor by binding to the receptor of the invading virus (Abdolalipour et al., 2020; Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020; Villena et al., 2020).

Cell adhesion is a multistage process classified into specific and nonspecific adhesion. Nonspecific adhesion occurs when a probiotic enters the cell and is mainly governed by physicochemical characteristics, such as contacts or hydrogen bonds (Kumar, 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). Specific adhesion involves the interaction between probiotic adhesins and their epithelial receptors, which is an irreversible connection that is more potent than nonspecific adhesion (Cao et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2022). The adhesion capacities of the selected strains were determined by examining their bacterial cell-surface features in a Caco-2 cell model, which is comparable in morphology to the intestinal epithelium. The composition of the microbiota profoundly impacts human health, and diet is a critical factor in determining its composition (Cao et al., 2020; Kumar, 2021; Wang et al., 2021b; Hwang et al., 2022).

A few strategies for modulating the host immune response, such as increasing essential nutrient intake and developing potential functional foods, are becoming popular to influence the activity of immune cells (Foysal et al., 2020). Dietary supplementation with probiotics enhances the states of the intestine, liver, and the immune system as well as the structure and functions of genetically modified substances. Probiotics considerably enhance the immune-associated metabolic pathways, such as amino sugar pathway, nucleotide sugar pathway, interleukin 17 (IL-17) signaling, and quorum sensing (Alvarez-Sieiro et al., 2016). In contrast, the absence of probiotics prevents glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. Bacterial communication via extracellular diffusible signaling molecules (quorum sensing) enables bacteria to coordinate their group activity and multicellular functioning. Bacteriocins also operate as signaling peptides, communicating with other bacteria through quorum sensing and bacterial cross-talk within microbial communities or with host immune cells (Foysal et al., 2020). The (N-acyl) homoserine lactone is used as a signal molecule in gram-negative bacteria, whereas peptides, including several bacteriocins, are frequently used as signaling molecules in gram-positive bacteria (Drider et al., 2016). In general, peptide-based quorum sensing in gram-positive bacteria mediates a two-component regulatory signal transduction system, comprising a membrane-bound histidine protein kinase (HPK) and an intracellular response regulator (RR) (Drider et al., 2016; Foysal et al., 2020). Thus, it has been postulated that few bacteriocins act as inhibitors at high concentrations and signaling molecules at low concentrations (Alvarez-Sieiro et al., 2016; Drider et al., 2016; Foysal et al., 2020).

HPK phosphorylates RR, which causes a response at the transcriptional level. The autoinducing peptide primarily serves as a signaling molecule; however, some autoinducing peptides also act as antimicrobials (Prazdnova et al., 2022). Bacteriocin nisin is the predominant example of this dual functioning. Nisin acts as a killer and signaling molecule and stimulates its production in a density-dependent manner (Belguesmia et al., 2020). Thus, probiotic consumption is the only nutritional practice capable of lowering the risk of viral infection and enhancing human immune responses (Belguesmia et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Prazdnova et al., 2022). Following these considerations and experimental reports, it is crucial to discover new strategies for preventing or reducing viral infections to minimize virus-related mortality, morbidity, and economic losses.

Bacteriocin Stability and Mode of Action

Bacteriocins are multifunctional proteinaceous compounds synthesized from ribosomal RNA with antimicrobial potential against pathogens at definite concentrations (Belguesmia et al., 2020), demonstrating their biotechnological capability (Chikindas et al., 2018). Bacteriocins are classified into three groups according to their physicochemical and structural features: classes I, II, and III (Chikindas et al., 2018). Moreover, during the early stages of development, bacteriocins are only active against closely related bacteria. However, the mode of action of bacteriocins against viruses is not yet fully understood. According to the available reports, bacteriocins exhibit two mechanisms for combating viral infection (Wachsman et al., 2003).

The first mechanism involves preventing viral particle aggregation and blocking the sites of host cell receptors (Wachsman et al., 2003). Additionally, certain bacteriocins possess an antiviral activity that inhibits viral penetration into human cells. For instance, it was shown that duramycin, a class I bacteriocin, blocks the Zika virus coreceptor TIM1 and subsequently inhibits its entry (Tabata et al., 2016). In the second mechanism, several bacteriocins induce cytopathic effect and reduce viral release without interfering with viral entry (Tabata et al., 2016). The mechanisms of bacteriocins against viral infection are related to their interaction with the late steps of the viral cycle, which strongly influence the main reactions of the viral multiplication step (Tabata et al., 2016). Additionally, within these bacteriocins, those recognized as antiviral molecules can bind to the lipid membranes of enveloped viruses as they are hydrophobic. Thus, probiotics exhibit their inhibitory action by interfering with cellular and viral membrane fusion (Cavicchioli et al., 2018). Given these considerations, the inactivity of several bacteriocins against nonenveloped viruses is attributed to the structural differences compared with active bacteriocins, particularly to the lack of hydrophobicity (Badani et al., 2014; Cavicchioli et al., 2018).

Bacteria produce bacteriocins as a defense or contact signal (Chikindas et al., 2018). A previous report indicated that the leading interface site among the host immune system, microorganisms in the GIT, and GM bacterial colonization influences the development of the adaptive immune system (Round and Mazmanian, 2009). Bacteriocins also elicit an immune response, causing changes in the GIT population. Another study investigated the potential of bacteriocins in penetrating the gut–blood barrier (i.e., Caco-2), which is further dependent on the physicochemical and biochemical characteristics of the membrane (Dreyer et al., 2019).

Numerous bacteriocins have been demonstrated to be effective against viral infections (Dobson et al., 2012). However, the route of the bacteriocin administration impacts the proteolytic enzyme activity. For instance, bacteriocins, such as nisin F, were active against pathogens when injected into the peritoneal cavity of mice. However, nisin F acts as a growth stabilizer for GM (Van Staden et al., 2011). It also plays a role in GIT colonization, promoting bacteriocin-producing strains (Kommineni et al., 2015). Thus, inducing bacteriocin-producing strains in the GIT is a viable alternative for monitoring viral infections, drug resistance, enteric invasion, and pathogen dissemination in the GIT (Hegarty et al., 2016).

Additionally, several factors influence the bacteriocin sensitivity of the target bacterium, including the presence of membrane-disrupting neutralizing molecules and physicochemical properties of the environment (ionic strength, pH). However, using bacteriocin is not similar to regular antibodies (Weeks and Chikindas, 2019); the microbial immunity against bacteriocin is extremely rare compared with that against antibodies (De Freire Bastos et al., 2015). Furthermore, microbial strains that induce resistance possess different mechanisms of antibody resistance (Chatterjee et al., 2005). For instance, microbial species undergo major structural modifications, such as changing the phospholipid and fatty acid composition of the cell membrane, increasing the galactose and D-alanyl ester content of the cell wall, or forming a thicker cell wall to avert bacteriocin docking with lipid II, thus developing bacteriocin resistance (Crandall and Montville, 1998; Chatterjee et al., 2005). Additionally, other microbial species possess some structural modifications that involve forming a requirement for Mn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Ba2+ in the cell wall or membrane (Crandall and Montville, 1998; Chatterjee et al., 2005).

Besides these structural changes, nonstructural modifications are also involved, which are capable of inducing bacteriocin resistance, trigger and induce mutation in the bacteriocin susceptibility-associated sensor (Collins et al., 2012), trigger the inactivation of the gene encoding bacterial RNA polymerase, produce nonproteolytic bacteriocins capable of inactivating enzyme-induced dehydroalanine-level reduction (Jarvis and Farr, 1971), and produce pH-related resistance alterations (Hasper et al., 2006). However, the molecular size, hydrophobicity, migration intensity, charge used to cross the epithelial cell membrane, and capacity to re-enter the tissue cells are the properties of bacteriocins that need further investigation. In this regard, several recently published studies on the immunomodulatory properties of bacteriocins have been noted (Jenab et al., 2020).

Bacteriocin as a Potential Immunobiotic Agent for Viral Infections

Reactions to immunomodulatory therapies are an emerging strategy against viral infection. Researchers studied that enhancing the body’s immune system by employing probiotic-based bacteriocin helps in fighting against viral diseases (Table 1; Yan et al., 2020, 2022; Wang et al., 2021a; Liu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Jayawardena and coworkers also reported that bacteriocin modulates the immune system and prevents viral infections, such as COVID-19 (Jayawardena et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Antiviral/antimicrobial activity of different bacteriocin as potential immunomodulatory agent and their action mode against viral disease.

| Compound | Role | Mode of action | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriocin | Shows immunomodulatory properties | GIT integrity, immune function is critical for preventing and controlling viruses | Belguesmia et al., 2020 | |

| Cationic antimicrobial peptides | Shows immunomodulatory properties | Hydrophobicity, positive charge, and small size immune system | Interferes and stimulates immune system | Sahl et al., 2005 |

| Bacteriocin | Shows immunomodulatory properties | Changes in DCs, improves activities of T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages, the IFN, and interleukin development | Enhances viral phagocytosis | Soltani et al., 2021 |

| Bacteriocin | Stimulates non-specific immunity releases pro-inflammatory cytokines | TNF-α and IL-6 | Increases the rotavirus-specific IgM and secretes cell and IgA responses to toxins | Soltani et al., 2021 |

| Bacteriocin | Enhances immune responses | Reduces the PRR stimulation | Promotes the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) and the B-cell nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer | O’Callaghan et al., 2012 |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | Enhances immune responses | Mouse-adapted influenza A (H1N1) infection BALB/c model | Improves humoral and cellular immunity and reduces IL-6 activity in the lungs | Mahooti et al., 2019 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | Enhances immune responses | Inhibits influenza A/chicken/Germany replication of the Weybridge (H7N7) and Rostock (H7N1) strains | Shows effectiveness against influenza tested strains in mice model | Serkedjieva et al., 2000 |

| Nisin-bateriocin | Enhances immune responses | Nisin-fed mice in the virus-infected model | Nisin has more significant immunomodulatory properties than the tested human cationic (LL-37) peptides | Kindrachuk et al., 2013 |

| Nisin-bateriocin | Enhances immune responses | Shows antigenic response of nisin in vivo against viruses | Increases IL-6 and IL-10 | Brand et al., 2010 |

| Bacteriocin | Enhances immune responses | Shows anti-influenza efficacy in mouse model | Shows effectiveness against anti-influenza virus | Ermolenko et al., 2019 |

DCs, dendritic cells; IFN, interferons; TNF-α, Tumour necrosis factorα; IL-6, interleukin-6; PRRs; pattern recognition receptors IgM; IgA; IL-10, interleukin-10.

The enterocins CRL35 and ST4V have also shown bacteriocin activities against herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 by influencing intracellular viral proliferation and interacting with the late steps of viral replication (Wachsman et al., 2003; Todorov et al., 2005). Additionally, subtilisin A and the pediocin-like bacteriocin ST5Ha showed anti-HSV activity with a selectivity index (CC50/EC50) of 173 (Quintana et al., 2014; Soltani et al., 2021). Further, Cavicchioli et al. (2018) reported that the bacteriocins from Enterococcus durans, Geo9, Ge12, and He17 inhibited the poliovirus (PV-1; Férir et al., 2013), revealing the dual antiviral action against HIV and HSV. They further revealed the transmission of antibiotic-derived prototype peptide containing the post-translationally transformed–special carbocyclic abionin residue. The same authors also identified labyrinthopeptin A1 (LabyA1) as a bacteriocin, emphasizing its ability to inhibit the viral cell-to-cell transfer between HIV-infected T cells and uninfected CD4 (+) T cells; moreover, it inhibits HIV capture by DC-SIGN+-cells, thereby inhibiting the transmission of the captured virus to uninfected CD4 (+) T cells (Férir et al., 2013; Table 2).

Table 2.

Antiviral/antimicrobial activity of different probiotic based bacteriocin and their producer strains along with mode of actions.

| Bacteriocin | Probiotic strains | Antiviral/antimicrobial activity | Mode of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 | L. gasseri | A/H1N1 and B influenza viruses | Vaccine-specific antibody production | Nishihira et al., 2018 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus IgG and HI NDV | L. acidophilus | A new castle virus disease | IgG and HI NDV | Gharajalar et al., 2020 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum DR7 | L. plantarum | Upper respiratory tract viral infections | Suppresses plasma proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) | Chong et al., 2019 |

| Enterocin CRL35 | Enterococcus faecium | HSV-1 HSV-2 | Inhibits the late-stage replication | Wachsman et al., 1999 |

| Lactobacillus helveticus LZ-R-5 | L. helveticus | Associated with the immune system | Immunostimulatory activity | You et al., 2020 |

| L. plantarum C70 | L. plantarum | Have possible bioactivities in food industries, including anticancer, antidiabetic, and antioxidant activities | Bioactivities | Ayyash et al., 2020 |

| L. plantarum SP8 | L. plantarum | Excellent biosorption ability toward methylene blue (MB) | Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) | Li et al., 2021 |

| L. plantarum SP8 | L. plantarum | Shows specific antioxidant activity | Bioactivities | Zhang et al., 2020 |

| EPS103 | L. plantarum JLAU103 | Shows scavenging abilities against hydroxyl, ABTS, and DPPH radicals | Bioactivities | Min et al., 2019 |

| Bacteriocin | Lactobacillus delbrueckii sub sp. bulgaricus | Shows anti-Virus activity. A/chicken/Germany, Weybridge (H7N7), Rostock (H7N1) | Inhibits replication, glycoproteins neuraminidase | Serkedjieva et al., 2000 |

| Enterocin ST4V | E. faecium ST4V | HSV-1 HSV-2 | Inhibits the late-stage replication | Todorov et al., 2005 |

| Labyrinthopeptin A1 (LabyA1) | Actinomadura namibiensis | Shows Anti-HIV-1 activity | Suppresses intercellular transmission between HIV-infected T cells and uninfected CD4 (+) T cells | Férir et al., 2013 |

| LabyA1 + raltegravir | A. namibiensis + antiretroviral agents | Shows anti-HIV-1 activity anti-HSV-2 activity | Inhibits the transmission of HIV from DC-SIGN+ cells to uninfected CD4 (+) T cells | Al Kassaa et al., 2014 |

| LabyA1 + LabyA2 | A. namibiensis DSM6313 | Associated with carcinoma-derived lung cells | Inhibits human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) | Haid et al., 2017 |

| Cell-free supernatants (CFS) | Lactobacillus curvatus 1 | Associated with murine norovirus (MNV) | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Lange-Starke et al., 2014 |

| Bacteriocin B1 | L. delbrueckii | Anti-Virus | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Serkedjieva et al., 2000 |

| Bacteriocin | Lactobacillus spp. | Anti-HIV-1 and Anti-HSV-2 | Lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide protein denaturing reactions | Conti et al., 2009 |

| Non-protein cell wall component | Lactobacillus brevis | Anti-HSV-2 | Reduces HSV-2 replication | Mastromarino et al., 2011 |

| Lactobacillus paracasei sub sp. rhamnosus | L. paracasei sub sp. rhamnosus | Vesicular stomatitis viruses | Adheres to the particles | Botić et al., 2007 |

| L. plantarum | L. plantarum | Vesicular stomatitis viruses | Adheres to the particles | Botić et al., 2007 |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | L. reuteri | Vesicular stomatitis viruses | Adheres to the particles | Botić et al., 2007 |

| Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 | Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 | Influenza virus H1N1 | Adheres to the particles | Wang et al., 2013 |

| L. gasseri CMUL57 | L. gasseri CMUL57 | HSV-2 | Adheres to the particles | Al Kassaa et al., 2014 |

| L. plantarum L-137 | L. plantarum L-137 | Influenza virus H1N1 | Elicits a pro-inflammatory response | Maeda et al., 2009 |

| Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 | L. fermentum CECT5716 | Influenza virus H1N1 | Improves the formation of antibodies against H1N1 | Olivares et al., 2007 |

| Lactobacillus casei DN114-001 | L. casei DN114-001 | Influenza virus H1N1 | Improves the formation of antibodies against H1N1 | Boge et al., 2009 |

| L. gasseri PA 16/8, Bifidobacterium longum SP07/3, and Bifidobacterium bifidum MF 20/5 | L. gasseri PA 16/8, B. longum SP07/3, and B. bifidum MF 20/5 | Common cold virus | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | De Vrese et al., 2006 |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | L. rhamnosus GG | Respiratory virus infections | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Rautava et al., 2008 |

| L. acidophilus NCFM | L. acidophilus NCFM | Influenza-like symptoms | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Leyer et al., 2009 |

| Enterocin AAR-71 | Enterococcus faecalis | Qureshi et al., 2006 | ||

| Enterocin AAR-74 | E. faecalis | Proliferation of coliphage HSA | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Qureshi et al., 2006 |

| Enterocin ST5Ha | E. faecium | Todorov et al., 2010 | ||

| Enterocin ST4V | Enterococcus mundtii | Herpes viruses HSV-1 and HSV-2 | Enterocins CRL35 and ST4V were used on the multiplication of virus particles | Todorov et al., 2005 |

| Enterocin CRL35 | E. mundtii | Inactive against herpes viruses | A derivative of enterocin CRL35, lacking two cysteine residues | Wachsman et al., 2003 |

| Bacteriocin | L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 1,043 | Influenza viruses | Inhibits intracellular virus replication | Serkedjieva et al., 2000 |

In contrast, Lange-Starke et al. (2014) reported the ineffective action of the bacteriocins produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, such as nisin, against influenza A (H1N1), HSV-1, murine norovirus, feline herpesvirus KS285, and Newcastle disease virus Montana. Semipurified bacteriocins obtained from two LAB strains isolated from goat milk (i.e., GLc03 and GLc05 from L. lactis, and GEn09, GEn12, GEn14, and GEn17 from E. durans) were screened in terms of cytotoxicity in Vero cells (CC50) and based on their antiviral activities against PV-1 and HVS1 (Villena et al., 2020).

A previous study showed that bacteriocins elicit an innate immune response during viral infection and induce pathogen death via inflammasomes (Weeks and Chikindas, 2019). The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex formed inside the cell by the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NOD-like receptors), also known as nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptors (NLRs) and DNA sensors. These inflammasomes trigger a sequence of dangerous signals elicited by pathogens and cellular stress (McNab et al., 2015). Further, another study revealed that the anti-inflammatory cytokines are inhibited via inflammatory signaling pathways by bacteriocin through their interaction with mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappa B (Yoon and Sun, 2011). Consequently, bacteriocins regulate inflammasome activation in organisms that previously experienced inflammation due to viral infections (Dicks et al., 2018; Abdolalipour et al., 2020; Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020; Antushevich, 2020).

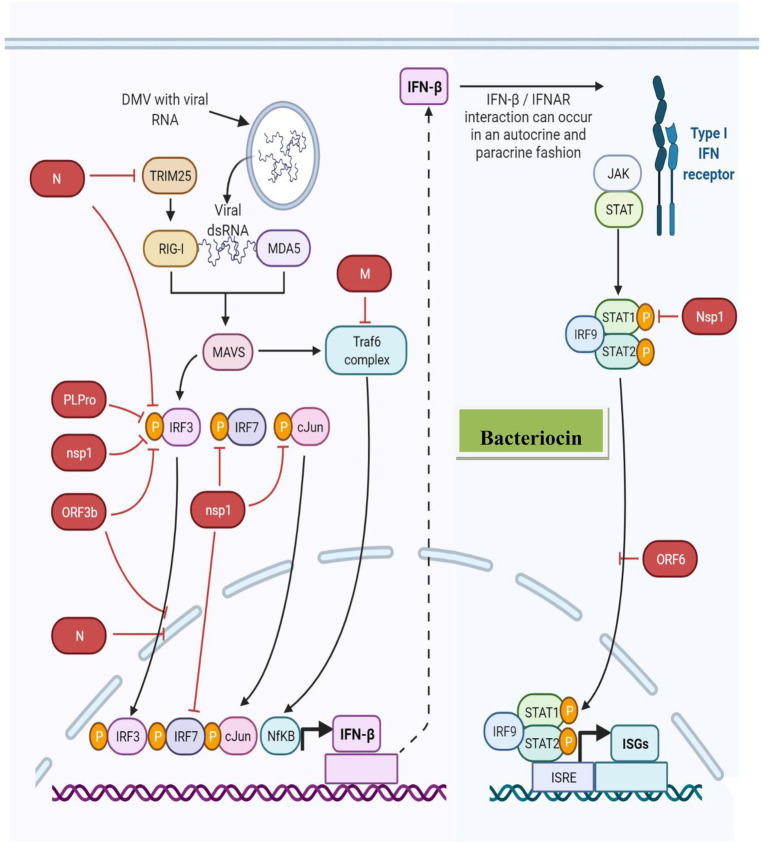

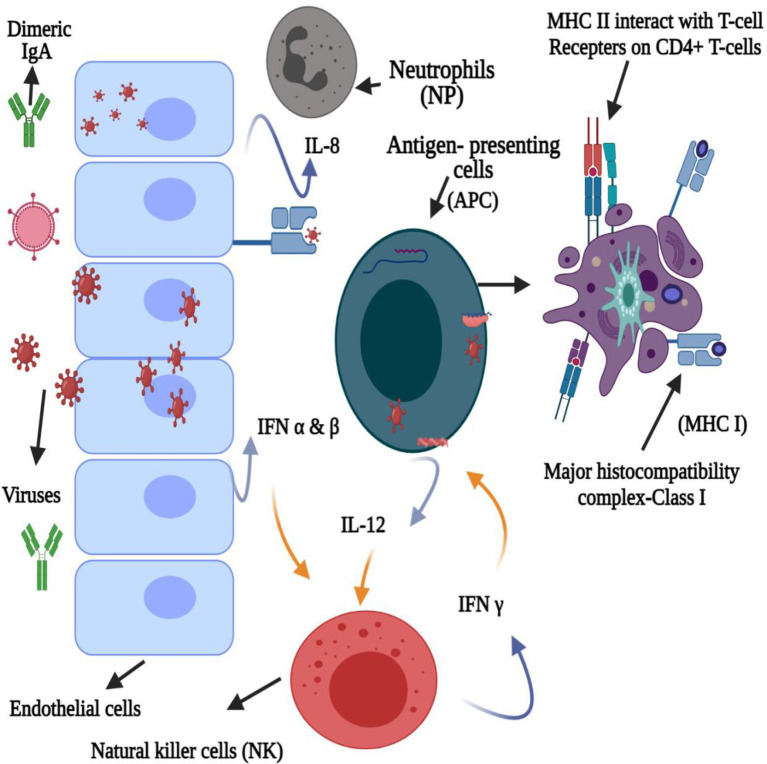

Furthermore, paracrine signaling occurs as a cell interacts with another nearby compartment or cell (unattached with gap junctions), resulting in the diffusion of the produced signaling molecule to a neighboring cell over a short distance. In contrast, autocrine signaling occurs when a cell communicates with the receptors on its own surface (Figure 3). During viral infection, IFN or IFN receptor (IFNR) (IFNAR) association occurs via autocrine or paracrine signaling (Silginer et al., 2017). For example, Lactobacillus spp. produces bacteriocins involved in IL-12-inducing potentially similar type I IFN production (Alvarez-Vieites et al., 2020; Antushevich, 2020), further demonstrating the immunostimulatory activity of bacteriocins and innate immune antagonistic activity against viral infections. Figure 4 presents the innate immune response to viruses induced by bacteriocins.

Figure 3.

Bacteriocin innate immune antagonism against viral infections.

Figure 4.

Bacteriocin-induced innate immune response against the virus.

The immune system recognizes pathogens in several ways, where inflammasomes induce the production of type I IFNs, IL-1, and IL-18 as the first line of defense against viruses (Dreyer et al., 2019; Antushevich, 2020). Type I IFNs stimulate an antiviral state in the infected host, and cytokines, such as IL, result in inflammation and modulate immune responses, exhibiting antiviral effects (Antushevich, 2020). Furthermore, these bacteriocins elicit an anti-inflammatory response in the innate immune system through dendritic cell signaling, resulting in the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-10) (Jenab et al., 2020). Bacteriocins from various studies were shown to increase the CD4 (+) levels and lymphocyte counts and monitor the TNF, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 expression levels (Chikindas et al., 2018; Dicks et al., 2018; Ou et al., 2019; Antushevich, 2020; Foysal et al., 2020; Jayawardena et al., 2020; Jenab et al., 2020).

Similarly, Fukuyama et al. (2020) investigated the immunomodulatory properties of bacteriocins and their ability to induce in vitro TLR-triggered inflammatory responses. The findings revealed that bacteriocins regulated inflammation and reduced the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, IL-8, and chemokine ligand 3 (CXCL3). It further upregulated the expression of three negative TLR regulators, i.e., the Toll-interacting protein (Tollip), ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 (TNF-α-induced protein 3, TNFAIP3), and single immunoglobulin IL-1 receptor-related protein (SIGIRR; Mages et al., 2008; Saleh and Trinchieri, 2011; Laiño et al., 2016; Fukuyama et al., 2020).

The potent antiviral activity was mediated by several encoded factors, including IL-2, IL-12, IFN-gamma, TNF-α, CD40 ligand (CD40L), membrane immunoglobulin (mIg), and (cytokine responsive gene 2) Crg-2 (Ramshaw et al., 1997), revealing the mechanism of bacteriocin in combating infection-induced inflammation induced by pathogens. Furthermore, another study reported the bacteriocin inhibitory effect on pathogen-adhesion and invasion of Caco-2 cells and the antiproliferative effects via apoptosis induction (Dicks et al., 2018). The authors also showed the reduced levels of TNF-α factor, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 combined with increased levels of IL-10 in serum, further demonstrating the bacteriocin immunomodulatory potential (Jenab et al., 2020).

Another study showed an eight-fold increase in the number of immune cells of probiotic-treated mice, exhibiting significant alterations in the onsite expression of proinflammatory mediators compared with the control group (Chondrou et al., 2020). Similarly, Lactobacillus shelveticus produced LZ-R-5 bacteriocin with immunostimulatory activity against viral infection (Ayyash et al., 2020; You et al., 2020). To date, there have been no reported studies on probiotics-derived bacteriocins in preventing and treating COVID-19. However, the phase II experimental research has been used to estimate the effect of an immunomodulatory drug (i.e., the anti-asthma live cell formulation MRx4DP0004) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Although the appropriate formulation was not tested, the patients were administered two doses of live cells (4 × 109–4 × 1010) for 2 weeks, and the preliminary results were positive. Thus, various probiotics can help control COVID-19 infection and assist as adjuvants for prophylaxis (Dobson et al., 2012; Alvarez-Sieiro et al., 2016).

Additionally, several viruses, such as norovirus (Shinde et al., 2020), rotavirus (RV), or calicivirus (CV), picornaviridae, orthomyxoviridae, paramyxoviridae, reoviridae, and coronaviridae, affect humans (Kamaluddin et al., 2020; Lopez-Santamarina et al., 2021). They are characterized by uncoated RNA, making them exceedingly infectious and fecal transmissible even when the associated infections are easily moderated to last for a short period (Karst, 2016). Regarding the widespread RV vaccination development, norovirus (NV) is the principal cause of severe diarrhea among children and foodborne diseases in developing countries. Approximately 200 million cases were observed among children under the age of 5 years, leading to an estimated 50,000 child deaths per year predominantly in developing countries (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Moreover, astroviruses are responsible for 2–9% of all cases of pediatric gastroenteritis globally (Fadhil et al., 2020).

These findings indicated that bacteriocins prevent virus replication more efficiently than viral adsorption; thus, bacteriocins act as novel antiviral agents for viral suppression (Cavicchioli et al., 2018). A large number of studies on the association between specific bacteriocins and antiviral activity showed that probiotics have biological benefits and antiviral properties that regulate and halt the pathogenic virus duplication. Additionally, they are only ascribed to their well-known antibacterial and immune modulation properties. The genesis of microorganisms is also proficient in conducting these activities; it stabilizes the indigenous protective reaction of the ecosystem to a possible territorial invasion, independent of the attack type (viral, bacterial, or fungal) (Cavicchioli et al., 2018).

Based on the available reports, bacteriocins exhibits two mechanisms against viral infection: (i) exhibits antiviral activity before the viral penetration into human cells; (ii) inhibits the viral entry and reduces the cytopathic impact and viral release yield by interacting with the late steps of the viral cycle. The first mechanism of the bacteriocin antiviral activity includes direct contact with viral cells (Al Kassaa et al., 2014), interaction with the epithelial cell surface to influence the electrolyte potential (OlayaGalán et al., 2016), and intracellular inhibition (Serkedjieva et al., 2000). Alternatively, the second mode of action includes the inhibition of the late-stage viral replication (Todorov et al., 2005), blockages on the host cell receptor, repressed intercellular transmission, and modulation of virus immune systems (Drider et al., 2016).

Małaczewska et al. (2019) detected immune modulation by stimulating IL, CD4 (+), and CD8 (+) T cells. Further, Yitbarek et al. (2018) reported that the immune system modulation protects the virus-infected cells. However, the molecular size, hydrophobicity, migration intensity, charge used to cross the epithelial cell membrane, and re-entry ability of tissue cells are the properties of bacteriocins that warrant further exploration (Małaczewska et al., 2019).

Probiotics may be inappropriate for patients unless the pathogenicity and influence of a particular coronavirus on GM has been identified. Besides, the foodborne transmission of COVID-19 is rather uncertain (Li et al., 2021). Therefore, further research should prove that food is a nonprobable agent of viral transmission. It is known that COVID-19 is more susceptible to a weakened immune system. Thus, probiotics as adjuvants or prophylactic and therapeutic agents for COVID-19 treatment should be carefully considered as researchers have reported that probiotics cause numerous septicemias associated with weakened immune systems in those individuals (Koyama et al., 2019).

Conclusions and Prospects

Probiotics are beneficial microorganisms administered to individuals to improve their healing. In particular, bifidobacteria and LAB probiotics exhibit sustainable therapeutic effects in treating vaginal and GIT viral infections. Moreover, probiotics effectively use cellular components, including peptidoglycans and DNA, and improve the efficacy of the bacterium by producing autoinducing peptides. These emerging probiotics with microbiota-modulation and anti-infection applications are classified into two categories: (i) a first treatment type (prophylaxis) where a low-dose drug is administered daily to maintain the presence of probiotics in the human microbiota; and (ii) a second treatment type where a relatively large dose of medication is administered to the infected individuals, coupled with immunologically sensitive host tissues to treat microbiota dysbiosis. However, the exact mechanism related to the ability of the probiotics to inhibit viral replication remains unknown. Therefore, it is crucial for the scientific and medical communities to focus on beneficial bacteria (probiotics) to combat viral infections.

Author Contributions

All authors were equal contributors in writing this review article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This review was funded by Khalifa Center for Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering-UAEU (Grant #: 31R286) to SAQ; Abu Dhabi Award for Research Excellence-Department of Education and Knowledge (Grant #: 21S105) to KE-T; and National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0910800) and the Special Fund for Development of Strategic Emerging Industries in Shenzhen (JCYJ20190808145613154 and KQJSCX20180328100801771).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank their respective institutions for their support. KE-T would also like to thank the library at Murdoch University, Australia, for the valuable online resources and comprehensive databases.

References

- Abdolalipour E., Mahooti M., Salehzadeh A., Torabi A., Mohebbi S. R., Gorji A., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the antitumor immune responses of probiotic Bifidobacterium bifidum in human papillomavirus-induced tumor model. Microb. Pathog. 145:104207. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104207, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Kassaa I., Hober D., Hamze M., Chihib N. E., Drider D. (2014). Antiviral potential of lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins. Probiotic. Antimicrob. Proteins 6, 177–185. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9162-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Sieiro P., Montalbán-López M., Mu D., Kuipers O. P. (2016). Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: extending the family. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 2939–2951. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7343-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Vieites E., López-Santamarina A., Miranda J. M., Del Carmen Mondragon A., Lamas A., Cardelle-Cobas A., et al. (2020). Influence of the intestinal microbiota on diabetes management. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 21, 1603–1615. doi: 10.2174/1389201021666200514220950, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antushevich H. (2020). Interplays between inflammasomes and viruses, bacteria (pathogenic and probiotic), yeasts and parasites. Immunol. Lett. 228, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.09.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyash M., Abu-Jdayil B., Itsaranuwat P., Galiwango E., Tamiello-Rosa C., Abdullah H., et al. (2020). Characterization, bioactivities, and rheological properties of exopolysaccharide produced by novel probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum C70 isolated from camel milk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 144, 938–946. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.171, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badani H., Garry R. F., Wimley W. C. (2014). Peptide entry inhibitors of enveloped viruses: the importance of interfacial hydrophobicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 2180–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belguesmia Y., Bendjeddou K., Kempf I., Boukherroub R., Drider D. (2020). Heterologous biosynthesis of five new class II bacteriocins from Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-5369 with antagonistic activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Front. Microbiol. 11:1198. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi A., Xiong Y., Rajoka M. S. R., Mehwish H. M., Radicetti E., Umair M., et al. (2021). Recent advances in the production of exopolysaccharide (EPS) from Lactobacillus spp. and its application in the food industry: A review. Sustainability 13:12429. doi: 10.3390/su132212429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boge T., Rémigy M., Vaudaine S., Tanguy J., Bourdet-Sicard R., van der Werf S. (2009). A probiotic fermented dairy drink improves antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly in two randomized controlled trials. Vaccine 27, 5677–5684. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.094, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botić T., Klingberg T. D., Weingartl H., Cencič A. (2007). A novel eukaryotic cell culture model to study antiviral activity of potential probiotic bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115, 227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.044, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. M., De Kwaadsteniet M., Dicks L. M. T. (2010). The ability of nisin F to control Staphylococcus aureus infection in the peritoneal cavity, as studied in mice. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 645–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02948.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Liu H., Qin N., Ren X., Zhu B., Xia X. (2020). Impact of food additives on the composition and function of gut microbiota: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.03.006, PMID: 35102308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli V. Q., Carvalho O. V., Paiva J. C., Todorov S. D., Júnior A. S., Nero L. A. (2018). Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and poliovirus (PV-1) by bacteriocins from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and Enterococcus durans strains isolated from goat milk. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51, 33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.04.020, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Data & statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/datastatistics/ (Accessed March 7, 2022).

- Chatterjee C., Paul M., Xie L., Van Der Donk W. A. (2005). Biosynthesis and mode of action of lantibiotics. Chem. Rev. 105, 633–684. doi: 10.1021/cr030105v, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., et al. (2020). Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikindas M. L., Weeks R., Drider D., Chistyakov V. A., Dicks L. M. (2018). Functions and emerging applications of bacteriocins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 49, 23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.07.011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondrou P., Karapetsas A., Kiousi D. E., Vasileiadis S., Ypsilantis P., Botaitis S., et al. (2020). Assessment of the immunomodulatory properties of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus paracasei K5 in vitro and in vivo. Microorganisms 8:709. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050709, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong H. X., Yusoff N. A. A., Hor Y. Y., Lew L. C., Jaafar M. H., Choi S. B., et al. (2019). Lactobacillus plantarum DR7 improved upper respiratory tract infections via enhancing immune and inflammatory parameters: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Dairy Sci. 102, 4783–4797. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-16103, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B., Guinane C. M., Cotter P. D., Hill C., Ross R. P. (2012). Assessing the contributions of the LiaS histidine kinase to the innate resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin, cephalosporins, and disinfectants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2923–2929. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07402-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti C., Malacrino C., Mastromarino P. (2009). Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 2 by vaginal lactobacilli. J Physiol. Pharmacol. 60 (Suppl 6), 19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall A. D., Montville T. J. (1998). Nisin resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302 is a complex phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 231–237. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.1.231-237.1998, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Freire Bastos M. D. C., Coelho M. L. V., Da Silva Santos O. C. (2015). Resistance to bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology 161, 683–700. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.082289-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vrese M., Winkler P., Rautenberg P., Harder T., Noah C., Laue C., et al. (2006). Probiotic bacteria reduced duration and severity but not the incidence of common cold episodes in a double blind, randomized, controlled trial. Vaccine 24, 6670–6674. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.048, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicks L. M., Dreyer L., Smith C., Van Staden A. D. (2018). A review: the fate of bacteriocins in the human gastro-intestinal tract: do they cross the gut–blood barrier? Front. Microbiol. 9:2297. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson A., Cotter P. D., Ross R. P., Hill C. (2012). Bacteriocin production: a probiotic trait? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05576-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer L., Smith C., Deane S. M., Dicks L. M. T., Van Staden A. D. (2019). Migration of bacteriocins across gastrointestinal epithelial and vascular endothelial cells, as determined using in vitro simulations. Sci. Rep. 9:11481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47843-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drider D., Bendali F., Naghmouchi K., Chikindas M. L. (2016). Bacteriocins: not only antibacterial agents. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 8, 177–182. doi: 10.1007/s12602-016-9223-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Saadony M. T., Saad A. M., Taha T. F., Najjar A. A., Zabermawi N. M., Nader M. M., et al. (2021). Selenium nanoparticles from Lactobacillus paracasei HM1 capable of antagonizing animal pathogenic fungi as a new source from human breast milk. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 6782–6794. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.07.059, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolenko E. I., Desheva Y. A., Kolobov A. A., Kotyleva M. P., Sychev I. A., Suvorov A. N. (2019). Anti–influenza activity of Enterocin B in vitro and protective effect of bacteriocinogenic enterococcal probiotic strain on influenza infection in mouse model. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 11, 705–712. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9457-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadhil H. Y., Al-Kareim M. J. A., Aufi I. M., Alhamdani F. G. (2020). Molecular detection of astrovirus using reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction technique. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 51, 191–200. doi: 10.36103/ijas.v51iSpecial.897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Férir G., Petrova M. I., Andrei G., Huskens D., Hoorelbeke B., Snoeck R., et al. (2013). The lantibiotic peptide labyrinthopeptin A1 demonstrates broad anti-HIV and anti-HSV activity with potential for microbicidal applications. PLoS One 8:e64010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064010, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foysal M. J., Fotedar R., Siddik M. A. B., Tay A. (2020). Lactobacillus acidophilus and L. plantarum improve health status, modulate gut microbiota and innate immune response of marron (Cheraxcainii). Sci. Rep. 10:5916. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62655-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama K., Islam M. A., Takagi M., Ikeda-Ohtsubo W., Kurata S., Aso H., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the immunomodulatory ability of lactic acid bacteria isolated from feedlot cattle against mastitis using a bovine mammary epithelial cells in vitro assay. Pathogens 9:410. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9050410, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharajalar S. N., Mirzai P., Nofouzi K., Madadi M. S. (2020). Immune enhancing effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus on Newcastle disease vaccination in chickens. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72:101520. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101520, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haid S., Blockus S., Wiechert S. M., Wetzke M., Prochnow H., Dijkman R., et al. (2017). Labyrinthopeptin A1 and A2 efficiently inhibit cell entry of hRSV isolates. Eur. Respir. J. 50:PA4124. doi: 10.1183/1393003.congress-2017.PA4124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. B., Tolonen A. C., Xavier R. J. (2017). Human genetic variation and the gut microbiome in disease. J Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 690–699. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.63, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasper H. E., Kramer N. E., Smith J. L., Hillman J. D., Zachariah C., Kuipers O. P., et al. (2006). An alternative bactericidal mechanism of action for lantibiotic peptides that target lipid II. Science 313, 1636–1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1129818, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty J. W., Guinane C. M., Ross R. P., Hill C., Cotter P. D. (2016). Bacteriocin production: a relatively unharnessed probiotic trait? F1000Research. 5:2587. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9615.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Guarner F., Reid G., Gibson G. R., Merenstein D. J., Pot B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document: The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang E., Kim H., Truong A. D., Kim S. J., Song K. D. (2022). Suppression of the toll-like receptors 3 mediated pro-inflammatory gene expressions by progenitor cell differentiation and proliferation factor in chicken DF-1 cells. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 64, 123–134. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e130, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffar M., Zailan A. N. (2021). Antimicrobial resistance (Amr)-forecast For 30 countries In Europe. Sci. Heritage. J. (GWS). 5, 44–48. doi: 10.26480/gws.02.2021.44.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis B., Farr J. (1971). Partial purification, specificity and mechanism of action of the nisin-inactivating enzyme from Bacillus cereus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Enzymol. 227, 232–240. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90056-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena R., Sooriyaarachchi P., Chourdakis M., Jeewandara C., Ranasinghe P. (2020). Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID-19: A review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 14, 367–382. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenab A., Roghanian R., Emtiazi G. (2020). Bacterial natural compounds with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 14, 3787–3801. doi: 10.2147/FDDDT.S261283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaluddin W. N. F. W. M., Rismayuddin N. A. R., Ismail A. F., Aidid E. M., Othman N., Mohamad N. A. H., et al. (2020). Probiotic inhibits oral carcinogenesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Oral Biol. 118:104855. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst S. M. (2016). The influence of commensal bacteria on infection with enteric viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 197–204. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.25, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil M., Caponio G. R., Diab F., Shanmugam H., Di Ciaula A., Khalifeh H., et al. (2022). Unraveling the beneficial effects of herbal Lebanese mixture “Za’atar”. History, studies, and properties of a potential healthy food ingredient. J. Funct. Foods 90:104993. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.104993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kindrachuk J., Jenssen H., Elliott M., Nijnik A., Magrangeas-Janot L., Pasupuleti M., et al. (2013). Manipulation of innate immunity by a bacterial secreted peptide: lantibiotic nisin Z is selectively immunomodulatory. Innate Immun. 19, 315–327. doi: 10.1177/1753425912461456, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kommineni S., Bretl D. J., Lam V., Chakraborty R., Hayward M., Simpson P., et al. (2015). Bacteriocin production augments niche competition by enterococci in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. Nature 526, 719–722. doi: 10.1038/nature15524, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S., Fujita H., Shimosato T., Kamijo A., Ishiyama Y., Yamamoto E., et al. (2019). Septicemia from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, from a probiotic enriched yogurt, in a patient with autologous stem cell transplantation. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 11, 295–298. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9399-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V. (2021). Going, toll-like receptors in skin inflammation and inflammatory diseases. EXCLI J. 20, 52–79. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-3114, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W.-F., Huang E., Lui K.-H. (2021). Alginate-based complex fibers with the Janus morphology for controlled release of co-delivered drugs. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 16, 77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2020.05.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laiño J., Villena J., Kanmani P., Kitazawa H. (2016). Immunoregulatory effects triggered by lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides: new insights into molecular interactions with host cells. Microorganisms 4:27. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms4030027, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Starke A., Petereit A., Truyen U., Braun P. G., Fehlhaber K., Albert T. (2014). Antiviral potential of selected starter cultures, bacteriocins and D L-lactic acid. Food Environ. Virol. 6, 42–47. doi: 10.1007/s12560-013-9135-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Morvan De Sequeira C., Hengstberger C., Enck P., Mack I. (2022). Effect of probiotics on psychiatric symptoms and central nervous system functions in human health and disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 14:621. doi: 10.3390/nu14030621, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtoranta L., Latvala S., Lehtinen M. J. (2020). Role of probiotics in stimulating the immune system in viral respiratory tract infections: A narrative review. Nutrients 12:3163. doi: 10.3390/nu12103163, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyer G. J., Li S., Mubasher M. E., Reifer C., Ouwehand A. C. (2009). Probiotic effects on cold and influenza-like symptom incidence and duration in children. Pediatrics 124, e172–e179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2666, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Zhao M. Y., Tan T. H. M. (2021). What makes a foodborne virus: comparing coronaviruses with human noroviruses. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 42, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2020.04.011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libertucci J., Young V. B. (2019). The role of the microbiota in infectious diseases. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 35–45. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0278-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Nie R., Liu Y., Mehmood A. (2022). Combined antimicrobial effect of bacteriocins with other hurdles of physicochemic and microbiome to prolong shelf life of food: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 15:154058. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santamarina A., Lamas A., Del Carmen Mondragón A., Cardelle-Cobas A., Regal P., Rodriguez-Avila J. A., et al. (2021). Probiotic effects against virus infections: new weapons for an old war. Foods 10:130. doi: 10.3390/foods10010130, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santamarina A., Miranda J. M., Mondragon A. D. C., Lamas A., Cardelle-Cobas A., Franco C. M., et al. (2020). Potential use of marine seaweeds as prebiotics: A review. Molecules 25:1004. doi: 10.3390/molecules25041004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda N., Nakamura R., Hirose Y., Murosaki S., Yamamoto Y., Kase T., et al. (2009). Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 enhances protection against influenza virus infection by stimulation of type I interferon production in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 9, 1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mages J., Dietrich H., Lang R. (2008). A genome-wide analysis of LPS tolerance in macrophages. Immunobiology 212, 723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahooti M., Abdolalipour E., Salehzadeh A., Mohebbi S. R., Gorji A., Ghaemi A. (2019). Immunomodulatory and prophylactic effects of Bifidobacterium bifidum probiotic strain on influenza infection in mice. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:91. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2667-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Małaczewska J., Kaczorek-Łukowska E., Wójcik R., Rękawek W., Siwicki A. K. (2019). In vitro immunomodulatory effect of nisin on porcine leucocytes. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 103, 882–893. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13085, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastromarino P., Cacciotti F., Masci A., Mosca L. (2011). Antiviral activity of Lactobacillus brevis towards herpes simplex virus type 2: role of cell wall associated components. Anaerobe 17, 334–336. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.04.022, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab F., Mayer-Barber K., Sher A., Wack A., O’garra A. (2015). Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 87–103. doi: 10.1038/nri3787, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min W. H., Fang X. B., Wu T., Fang L., Liu C. L., Wang J. (2019). Characterization and antioxidant activity of an acidic exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum JLAU103. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 127, 758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.12.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minj J., Chandra P., Paul C., Sharma R. K. (2021). Bio-functional properties of probiotic Lactobacillus: current applications and research perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 2207–2224. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1774496, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad U., Zhu X., Lu Z., Han J., Sun J., Tayyaba S., et al. (2018). Effects of extraction variables on pharmacological activities of vine tea extract (Ampelopsis grossedentata). Int. J. Pharmacol. 14, 495–505. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2018.495.505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naseef H. A., Mohammad U., Al-Shami N., Sahoury Y., Abukhalil A. D., Dreidi M., et al. (2022). Bacterial and fungal co-infections among ICU COVID-19 hospitalized patients in a Palestinian hospital: a retrospective cross-sectional study. F1000Research. 11:30. doi: 10.1101/2021.09.12.21263463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihira J., Nishimura M., Moriya T., Sakai F., Kabuki T., Kawasaki Y. (2018). “Lactobacillus gasseri potentiates immune response against influenza virus infection” in Immunity and Inflammation in Health and Disease. eds. Chatterjee S., Bagchi D. (Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; ), 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan J., Buttó L. F., Macsharry J., Nally K., O’Toole P. W. (2012). Influence of adhesion and bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus salivarius on the intestinal epithelial cell transcriptional response. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5196–5203. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00507-12, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OlayaGalán N. N., Ulloa Rubiano J. C., Velez Reyes F. A., Fernandez Duarte K. P., Salas Cardenas S. P., Gutierrez Fernandez M. F. (2016). In vitro antiviral activity of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium adolescentis against rotavirus infection monitored by NSP 4 protein production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 1041–1051. doi: 10.1111/jam.13069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares M., Díaz-Ropero M. P., Sierra S., Lara-Villoslada F., Fonollá J., Navas M., et al. (2007). Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition 23, 254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Y. C., Fu H. C., Tseng C. W., Wu C. H., Tsai C. C., Lin H. (2019). The influence of probiotics on genital high-risk human papilloma virus clearance and quality of cervical smear: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 19:103. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0798-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prazdnova E. V., Gorovtsov A. V., Vasilchenko N. G., Kulikov M. P., Statsenko V. N., Bogdanova A. A., et al. (2022). Quorum-sensing inhibition by Gram-positive bacteria. Microorganisms 10:350. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilodrán-Vega S., Albarracin L., Mansilla F., Arce L., Zhou B., Islam M. A., et al. (2020). Functional and genomic characterization of Ligilactobacillus salivarius TUCO-L2 isolated from Lama glama milk: a promising immunobiotic strain to combat infections. Front. Microbiol. 11:608752. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.608752, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana V. M., Torres N. I., Wachsman M. B., Sinko P. J., Castilla V., Chikindas M. (2014). Antiherpes simplex virus type 2 activity of the antimicrobial peptide subtilosin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117, 1253–1259. doi: 10.1111/jam.12618, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi H., Saeed S., Ahmed S., Rasool S. A. (2006). Coliphage hsa as a model for antiviral studies/spectrum by some indigenous bacteriocin like inhibitory substances (BLIS). Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 19, 182–185., PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajoka M. S. R., Mehwish H. M., Kitazawa H., Barba F. J., Berthelot L., Umair M., et al. (2022). Techno-functional properties and immunomodulatory potential of exopolysaccharide from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum MM89 isolated from human breast milk. Food Chem. 377:131954. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131954, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramshaw I. A., Ramsay A. J., Karupiah G., Rolph M. S., Mahalingam S., Ruby J. C. (1997). Cytokines and immunity to viral infections. Immunol. Rev. 159, 119–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1997.tb01011.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautava S., Salminen S., Isolauri E. (2008). Specific probiotics in reducing the risk of acute infections in infancy–a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br. J. Nutr. 101, 1722–1726. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508116282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riaz Rajoka M. S., Thirumdas R., Mehwish H. M., Umair M., Khurshid M., Hayat H. F., et al. (2021). Role of food antioxidants in modulating gut microbial communities: novel understandings in intestinal oxidative stress damage and their impact on host health. Antioxidants 10:1563. doi: 10.3390/antiox10101563, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J. L., Mazmanian S. K. (2009). The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahl H. G., Pag U., Bonness S., Wagner S., Antcheva N., Tossi A. (2005). Mammalian defensins: structures and mechanism of antibiotic activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77, 466–475. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804452, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M., Trinchieri G. (2011). Innate immune mechanisms of colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri2891, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senan A. M., Yin B., Zhang Y., Nasiru M. M., Lyu Y. M., Umair M., et al. (2021). Efficient and selective catalytic hydroxylation of unsaturated plant oils: a novel method for producing anti-pathogens. BMC Chem. 15:20. doi: 10.1186/s13065-021-00748-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkedjieva J., Danova S., Ivanova I. (2000). Antiinfluenza virus activity of a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 88, 285–298. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:88:1-3:285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde T., Hansbro P. M., Sohal S. S., Dingle P., Eri R., Stanley R. (2020). Microbiota modulating nutritional approaches to countering the effects of viral respiratory infections including SARS-CoV-2 through promoting metabolic and immune fitness with probiotics and plant bioactives. Microorganisms 8:921. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060921, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silginer M., Nagy S., Happold C., Schneider H., Weller M., Roth P. (2017). Autocrine activation of the IFN signaling pathway may promote immune escape in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 19, 1338–1349. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox051, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani S., Hammami R., Cotter P. D., Rebuffat S., Said L. B., Gaudreau H., et al. (2021). Bacteriocins as a new generation of antimicrobials: toxicity aspects and regulations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 45:fuaa039. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuaa039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T., Petitt M., Puerta-Guardo H., Michlmayr D., Wang C., Fang-Hoover J., et al. (2016). Zika virus targets different primary human placental cells, suggesting two routes for vertical transmission. Cell Host Microbe 20, 155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov S. D., Wachsman M. B., Knoetze H., Meincken M., Dicks L. M. (2005). An antibacterial and antiviral peptide produced by Enterococcus mundtii ST4V isolated from soya beans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 25, 508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.02.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov S. D., Wachsman M., Tomé E., Dousset X., Destro M. T., Dicks L. M. T., et al. (2010). Characterization of an antiviral pediocin-like bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecium. Food Microbiol. 27, 869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.05.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umair M., Jabbar S., Sultana T., Ayub Z., Abdelgader S. A., Xiaoyu Z., et al. (2020). Chirality of the biomolecules enhanced its stereospecific action of dihydromyricetin enantiomers. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 4843–4856. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1766, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umair M., Sultana T., Xiaoyu Z., Senan A. M., Jabbar S., Khan L., et al. (2022). LC-ESI-QTOF/MS characterization of antimicrobial compounds with their action mode extracted from vine tea (Ampelopsis grossedentata) leaves. Food Sci. Nutr. 10, 422–435. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2679, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Staden D. A., Brand A. M., Endo A., Dicks L. M. (2011). Nisin F, intraperitoneally injected, may have a stabilizing effect on the bacterial population in the gastro-intestinal tract, as determined in a preliminary study with mice as model. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 53, 198–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03091.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villena J., Shimosato T., Vizoso-Pinto M. G., Kitazawa H. (2020). Nutrition, immunity and viral infections. Front. Nutr. 7:125. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachsman M. B., Castilla V., de Ruiz Holgado A. P., de Torres R. A., Sesma F., Coto C. E. (2003). Enterocin CRL35 inhibits late stages of HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 58, 17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00099-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachsman M. B., Farias M. E., Takeda E., Sesma F., De Ruiz Holgado A. P., De Torres R. A., et al. (1999). Antiviral activity of enterocin CRL35 against herpesviruses. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 12, 293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00078-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Chai W., Burwinkel M., Twardziok S., Wrede P., Palissa C., et al. (2013). Inhibitory influence of Enterococcus faecium on the propagation of swine influenza A virus in vitro. PLoS One 8:53043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Jia D., Wang J. H., Li H. H., Liu J. L., Liu A. H., et al. (2021b). Assessment of probiotic adhesion and inhibitory effect on Escherichia coli and Salmonella adhesion. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 6267–6274. doi: 10.1007/s00203-021-02593-z, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Ning S., Yu B., Wang Y. (2021a). USP14: structure, function, and target inhibition. Front. Pharmacol. 12:801328. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.795205, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks R., Chikindas M. L. (2019). “Biological control of food-challenging microorganisms” in Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers. 5th Edn. eds. Doyle M. P., Diez-Gonzalez F., Hill C. (Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; ), 733–754. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Yao Y., Yan S., Gao R., Lu W., He W. (2020). Chiral protein supraparticles for tumor suppression and synergistic immunotherapy: an enabling strategy for bioactive supramolecular chirality construction. Nano Lett. 20, 5844–5852. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01757, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Zheng X., You W., He W., Xu G. K. (2022). A bionic-homodimerization strategy for optimizing modulators of protein–protein interactions: From statistical mechanics theory to potential clinical Translation. Adv. Sci. 9:2105179. doi: 10.1002/advs.202105179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yitbarek A., Taha-Abdelaziz K., Hodgins D. C., Read L., Nagy É., Weese J. S., et al. (2018). Gut microbiota-mediated protection against influenza virus subtype H9N2 in chickens is associated with modulation of the innate responses. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31613-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. S., Sun J. (2011). Probiotics, nuclear receptor signaling, and anti-inflammatory pathways. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2011:971938. doi: 10.1155/2011/971938, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You X., Yang L., Zhao X., Ma K., Chen X., Zhang C., et al. (2020). Isolation, purification, characterization and immunostimulatory activity of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus pentosus LZ-R-17 isolated from Tibetan kefir. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 158, 408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.027, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef M., Ahmed H. Y., Zongo A., Korin A., Zhan F., Hady E., et al. (2021). Probiotic supplements: their strategies in the therapeutic and prophylactic of human life-threatening diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:11290. doi: 10.3390/ijms222011290, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Ma P., Ahmed R., Wang J., Akin D., Soto F., et al. (2022). Advanced point-of-care testing Technologies for Human Acute Respiratory Virus Detection. Adv. Mater. 34:2103646. doi: 10.1002/adma.202103646, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z. (2020). Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 30, 1346–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]