Abstract

The complete genomic sequencing of Methanococcus jannaschii cannot identify the gene for the cysteine-specific member of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. However, we show here that enzyme activity is present in the cell lysate of M. jannaschii. The demonstration of this activity suggests a direct pathway for the synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNACys during protein synthesis.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are responsible for the synthesis of aminoacyl-tRNAs. Each of the 20 AARSs activates an amino acid with ATP and transfers the activated aminoacyl-adenylate to a tRNA. The synthesis of an aminoacyl-tRNA provides the basis for relating an amino acid to the tRNA anticodon of the genetic code. Because of their central role in processing genetic information, the 20 AARSs arose early and have developed highly conserved sequence motifs that can be recognized in databases of the three domains of life, the Eucarya, the Bacteria (eubacteria), and the Archaea. However, analysis of the sequenced genome of the methane-producing archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii has identified only 16 of the 20 AARSs (3). The same problem exists in the genomic analysis of a related archaeon, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (19). Missing in both analyses are the enzymes for glutamine (GlnRS), asparagine (AsnRS), lysine (LysRS), and cysteine (CysRS). The absence of GlnRS and AsnRS may not be critical, as the synthesis of Gln-tRNAGln and Asn-tRNAAsn can be achieved in indirect pathways. Many gram-positive eubacteria and archaea use the glutamate enzyme to synthesize Glu-tRNAGln or the aspartate enzyme to synthesize Asp-tRNAAsn and then rely on a transamidase to convert the precursor aminoacyl-tRNA to the correct form (7). The absence of an identifiable LysRS has been resolved by biochemical studies (8). The aminoacylation activity of the LysRS enzyme was found in the cell lysate of the related Methanococcus maripaludis, and this has led to the purification of the enzyme and identification of its gene in the genomes of M. maripaludis. This gene was found to have a homolog in the genomes of M. jannaschii, M. thermoautotrophicum, and some eubacteria (9).

The only unresolved issues are CysRS and the question of whether the synthesis of Cys-tRNACys may be achieved through another synthetase. One popular hypothesis was that CysRS is dispensable and that the synthesis of Cys-tRNACys is formed through misacylation of tRNACys by the serine enzyme and subsequent thiolation of the tRNA-bound serine to cysteine. Although analysis of the M. jannaschii genome does not indicate a clear pathway for the synthesis of cysteine, the rationale for serine as a precursor was based on pathways in organisms of the Bacteria and Eucarya domains. Many eubacteria use serine to synthesize cysteine via the intermediate O-acetylserine. In animals and humans, serine condenses with homocysteine to form cystathionine, which is then broken down to cysteine. The process of using a tRNA-bound serine as a precursor to synthesize cysteine would be novel, but it would be similar to the formation of selenocysteinyl-tRNASec (2). In the latter case, serine is first attached to tRNASec (tRNA specific for selenocysteine) by a serine enzyme and then the tRNA-bound serine is converted to selenocysteine to generate selenocysteinyl-tRNASec. However, recent studies have argued against a role of the serine enzyme in the synthesis of Cys-tRNACys. Specifically, the serine enzyme (SerRS) purified from the related M. thermoautotrophicum or the serine enzyme cloned from M. maripaludis does not aminoacylate tRNACys with serine (12). The failure of the serine enzyme to aminoacylate tRNACys with serine suggests that seryl-tRNACys is not made in these methanogens and thus cannot be a precursor for cysteinyl-tRNACys.

The elimination of serine as a possible candidate in an indirect pathway prompted the search for the direct pathway for the synthesis of Cys-tRNACys. Here we present data to show the aminoacylation activity that synthesizes Cys-tRNACys in the cell lysate of M. jannaschii. The demonstration of this activity suggests a direct pathway for aminoacylation of tRNACys and the presence of a CysRS that catalyzes this reaction.

We investigated the activity of CysRS in the cell lysate by assaying for its ability to aminoacylate tRNACys. Specifically, we used [35S]cysteine as a substrate, assayed for the attachment of [35S]cysteine to tRNACys, and visualized the product [35S]Cys-tRNACys on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel at pH 5.5 (4). In this assay, the product [35S]Cys-tRNACys was detected by phosphorimaging, whereas the free tRNA was not detected and the free [35S]cysteine migrated off the gel. Perhaps, due to the high contents of proteins containing irons and sulfurs in the cell lysate of M. jannaschii, the traditional analysis of aminoacylation measuring acid-precipitable counts on filter pads was not reliable for detecting the synthesis of Cys-tRNACys (18).

We prepared the cell lysate of M. jannaschii as S100 or as a DEAE fraction. The S100 was the cleared supernatant after centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The DEAE fraction was the fraction of S100 that was retained by the DEAE Sepharose column and eluted by a linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. Both lysates were expected to contain AARSs.

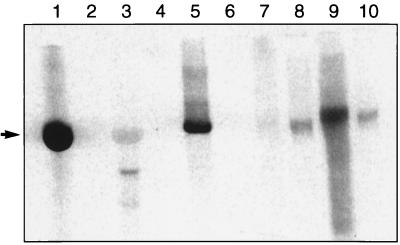

The phosphorimage of a gel analysis at pH 5.5 shown in Fig. 1 demonstrates the aminoacylation activity of M. jannaschii S100 with total tRNA isolated from the organism as the substrate (lane 9). The significance of this activity was supported by positive controls. One control was the ability of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DEAE fraction to aminoacylate the T7 transcript of yeast tRNACys (Fig. 1, lane 1). A second control was the ability of the same fraction to aminoacylate total yeast tRNA (Fig. 1, lane 3). In the second control, the preparation of the total yeast tRNA appeared to be contaminated with nucleases, which cleaved the charged tRNACys to a smaller fragment (Fig. 1, lane 3). Nonetheless, both controls confirmed the activity of yeast CysRS in the DEAE fraction (5). A third control was the ability of the purified Escherichia coli CysRS to aminoacylate the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNACys. The T7 transcript was made by transcribing a synthetic gene of M. jannaschii tRNACys (encoding the CCA sequence) by T7 RNA polymerase under the control of a synthetic T7 promoter (see reference 5 for the method). The T7 transcript was purified by gel electrophoresis and was refolded into the native state in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+. The aminoacylation of the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNACys by E. coli CysRS confirmed that the transcript was a functional substrate for aminoacylation. This aminoacylation was expected because the M. jannaschii tRNA sequence preserved U73 and the GCA anticodon, which are the important recognition elements for the E. coli enzyme (5, 14, 17). All of the detected activities in the controls were dependent on the addition of exogenous tRNA; elimination of tRNA gave no signal of aminoacylation (Fig. 1, lanes 2, 4, and 6).

FIG. 1.

Phosphorimage of an acid gel analysis of the synthesis of [35S]Cys-tRNACys (indicated by the arrow) in standard reaction conditions (5). Lanes: 1, S. cerevisiae DEAE (30 μg) plus the T7 transcript of S. cerevisiae tRNACys (63 μg); 3, S. cerevisiae DEAE (30 μg) plus S. cerevisiae total tRNA (100 μg); 5, E. coli CysRS (6.3 μM) plus the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNACys (60 μg); 7, M. jannaschii S100 (96 μg) plus the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNACys (60 μg); 9, M. jannaschii S100 (96 μg) plus M. jannaschii total tRNA (200 μg). Lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 are the same as lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, respectively, except that they are without the addition of exogenous tRNA. Note that the signals in lanes 8 and 10 are due to aminoacylation of the native tRNACys present in S100 but that the addition of the T7 transcript reduced this signal (lane 7). We estimated that 0.3% of the total M. jannaschii tRNA was tRNACys, based on the plateau level of the total tRNA that was aminoacylated with cysteine.

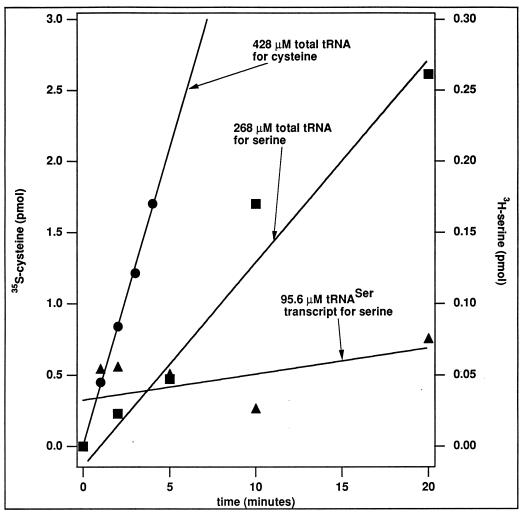

We also prepared the DEAE fraction of M. jannaschii S100. This was achieved by passing S100 through a DEAE Sepharose column and combining the fractions that bound to DEAE and eluted over a gradient of 0 to 500 mM NaCl. The DEAE fraction was devoid of most tRNAs. This was not the case with S100. Figure 1 shows that S100 alone, without the addition of exogenous tRNA, had activity (Fig. 1, lanes 8 and 10), due to inherent total tRNA present in the M. jannaschii S100 lysate. Figure 2 shows that the DEAE fraction was active for aminoacylation with cysteine, with the addition of the total tRNA from M. jannaschii as the substrate, and that this activity was detected by the acid-precipitable counts of [35S]Cys-tRNACys. The background for the assay was provided by a control without the addition of the total tRNA, and this gave acid-precipitable counts superimposable as those from another control without the addition of the enzyme (data not shown). The counts presented in Fig. 2 were subtracted from those of the controls. The DEAE fraction was also active with serine (Fig. 2), which suggests that the fraction was enriched with a number of tRNA synthetases. The activity with cysteine was higher than that with serine, probably because the fractionation was based on the cysteine activity, which had been separated from the serine activity by the DEAE Sepharose column.

FIG. 2.

Aminoacylation activities of the M. jannaschii DEAE fraction with cysteine and with serine, measured by the acid-precipitable counts of aminoacyl-tRNA under standard assay conditions. The assay solution for cysteine contained 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 50 μM [35S]cysteine at 65°C. Aminoacylation with cysteine was detected with a 428 μM concentration of the total M. jannaschii tRNA (∼1.28 μM tRNACys) and with 5 μg of the DEAE fraction. The assay solution for serine contained 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 20 μM [3H]serine at 65°C. Aminoacylation with serine was detected with a 268 μM concentration of the total M. jannaschii tRNA (∼0.268 μM tRNASer) and with 12.5 μg of the DEAE fraction. However, when the total tRNA was replaced with 95.6 μM tRNASer made from T7 transcription, the activity of aminoacylation with serine was hardly above that of the controls. The controls for the assay were aminoacylation reactions performed in the absence of exogenous tRNA or in the absence of the DEAE fraction, which gave points that were superimposable. These controls provided background for each time point that was then subtracted from each determination. Note that the scale for cysteine is different from that for serine. The activity of aminoacylation with cysteine was estimated as 0.67 pmol/min, while that with serine was estimated as 0.012 pmol/min.

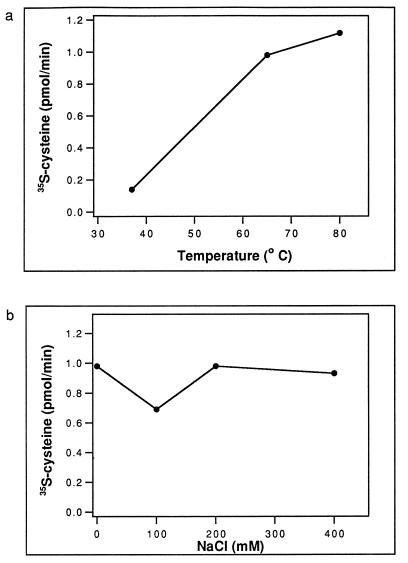

The assay whose results are shown in Fig. 2 was performed at 65°C under our standard assay conditions for the E. coli CysRS enzyme, i.e., in a solution containing 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM ATP, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 50 μM [35S]cysteine. Because M. jannaschii is a hyperthermophile with an internal salt concentration around 400 mM, we further characterized the activity for aminoacylation with cysteine for temperature and salt dependence. We defined the activity as the rate of converting [35S]cysteine to the acid-precipitable [35S]Cys-tRNACys per min. Figure 3a shows that M. jannaschii activity is temperature dependent. It was optimal at 80°C (1.12 pmol/min), which is near the normal growth temperature of the organism, but decreased by about 10-fold at 37°C (0.14 pmol/min). However, the activity at 65°C (0.98 pmol/min) was near optimal, and this provided the basis for routine assays at 65°C, which is more convenient for experimental handling than 80°C. We then determined if the activity is dependent on salt concentration at 65°C. Fig. 3b shows that over a range of 20 to 400 mM NaCl the activity did not vary much. This provides the basis for routine assays at 20 mM KCl.

FIG. 3.

The activity of aminoacylation with cysteine of M. jannaschii CysRS, measured by the acid-precipitable counts of [35S]Cys-tRNACys under standard assay conditions (see the legend for Fig. 2). (a) The temperature dependence profile of the activities measured at 37, 65, and 80°C. (b) The salt dependence profile of the activities measured at 65°C in the presence of 0, 100, 200, and 400 mM NaCl.

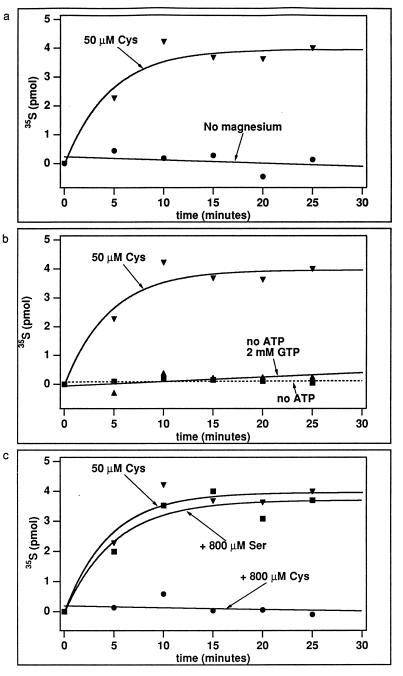

Using standard assay conditions (with 20 mM KCl at 65°C), we then showed that the activity has all the correct features for a Cys-tRNA synthetase. Figure 4a shows that the activity was dependent on Mg2+. Removal of Mg2+ eliminated the activity. Figure 4b shows that the activity was dependent on ATP. Substitution of ATP with GTP (at 2 mM) did not support the activity. Most importantly, we showed that the activity was specific for cysteine but not serine. Figure 4c shows that the addition of a molar excess of unlabeled cysteine (800 μM) to the aminoacylation reaction mixture containing [35S]cysteine (50 μM) eliminated the signal of aminoacylation by isotopic dilution. This effect strengthens the argument that the signal is specific to cysteine and is not an artifact. In contrast, the addition of excess serine had little effect. This argues against a role of serine in aminoacylation.

FIG. 4.

Substrate specificity of aminoacylation with cysteine by M. jannaschii CysRS, measured by the acid-precipitable counts of [35S]Cys-tRNACys under standard assay conditions. (a) Removal of Mg2+ from the standard assay buffer eliminated the activity. (b) Substitution of 2 mM ATP in the standard assay buffer with 2 mM GTP eliminated the activity. (c) Aminoacylation was sensitive to the addition of unlabeled cysteine (800 μM) to the reaction mixture but not to the addition of serine (800 μM).

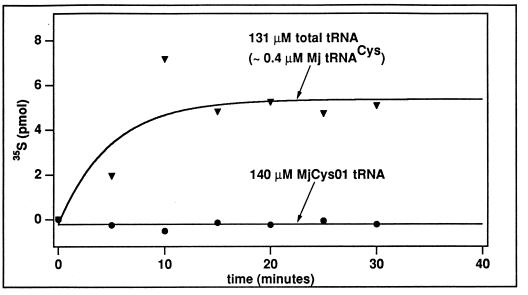

The demonstration of the aminoacylation activity in S100 and in the DEAE fraction of M. jannaschii cell lysate suggests the existence of CysRS. The putative M. jannaschii CysRS differs from representative members of CysRS in the database in one major respect. While the E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and human CysRS enzymes can easily aminoacylate the T7 transcript of their respective tRNA (6, 16), M. jannaschii CysRS cannot. This is evident in Fig. 5, where we compared the ability of the enzyme in the DEAE fraction to aminoacylate the native tRNA with that of the transcript. Clearly, based on the acid-precipitable counts of [35S]Cys-tRNACys, the enzyme efficiently aminoacylated the total tRNA at a concentration of 130 μM, which contained approximately a concentration of 0.4 μM cysteine-specific tRNA. In contrast, the enzyme did not aminoacylate the transcript at a concentration of 140 μM. Despite this, the transcript was an inhibitor of the native tRNA in aminoacylation. Addition of the transcript to the native tRNA present in S100 reduced the signal of aminoacylation (Fig. 1, compare the stronger signal in lanes 8 and 10 with the weaker signal in lane 7). Thus, while the transcript is incapable of aminoacylation, it may bind to the enzyme at the same site as the native tRNA. Additionally, the complete absence of a signal for aminoacylation with the transcript, even at a concentration more than 1,000-fold greater than that of the native tRNA, verified that the activity in the DEAE fraction was dependent on an appropriate tRNA substrate. This confirmed that the DEAE Sepharose column fractionation indeed had removed the inherent total tRNA from S100.

FIG. 5.

Aminoacylation by M. jannaschii CysRS, measured by the acid-precipitable counts of [35S]Cys-tRNACys under standard assay conditions, is dependent on tRNA-modified bases. The activity was detected with a 131 μM concentration of the total tRNA isolated from M. jannaschii, which was estimated to contain 0.4 μM tRNACys. In contrast, the activity was not detected with a 140 μM concentration of the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNACys (MjCys01 tRNA). The T7 transcript was prepared by synthesizing the tRNA gene with the CCA sequence, transcribing the gene with T7 RNA polymerase, and reannealing the T7 transcript in the presence of Mg2+ to its native state (see reference 5 for details). Mj, M. jannaschii.

The lack of aminoacylation with the transcript suggests that modified nucleotides on the native tRNA, which are absent from the transcript, are important for the putative M. jannaschii CysRS. This raises the possibility of a link between tRNA modification and aminoacylation, and it provides a basis for speculating that metabolic components in M. jannaschii contributing to tRNA modification might be coupled to the machinery of tRNA aminoacylation. The archaeal tRNAs in general contain more modifications of a wider diversity than tRNAs of eucarya and eubacteria. While some of these modifications are necessary to stabilize tRNAs under extreme environments (15), some others may be important for aminoacylation. The dependence on modifications probably is not unique to aminoacylation with cysteine but rather a more general feature of the aminoacylation machinery of archaea. This idea is supported by analysis of aminoacylation by SerRS. Figure 2 shows that the SerRS enzyme in the DEAE fraction, while capable of aminoacylation of tRNASer in the total tRNA at a concentration of 268 μM (of which approximately 1% would be tRNASer), did not significantly aminoacylate the T7 transcript of M. jannaschii tRNASer at a concentration of 95.6 μM.

The presence of M. jannaschii CysRS activity raises the question of why its gene was not identified from analysis of the genome. This absence is unlikely to have risen from technical errors in the analysis of the genome, as it is also documented in the genomic analysis of M. thermoautotrophicum. We note that the genomes of two other archaea, Archaeoglobus fulgidus and Pyrococcus horikoshii, have identified the conventional CysRS in each case (10, 11, 13). This suggests that the tools for sequence analysis of CysRS in the database are valid. One possibility is that M. jannaschii CysRS may have unusual sequence motifs that are distinct from those in the conventional CysRS enzymes and, as such, prevent the identification of its gene in the genome. This idea is supported in part by the strong emphasis of the enzyme on tRNA modifications, which sets it apart from all other characterized CysRS enzymes. Further analysis of the genome by using secondary structural elements should be pursued (1), in order to determine if the enzyme has novel sequences but a conserved structural fold. The LysRS enzyme of M. jannaschii and M. thermoautotrophicum is such an example; while distinct in sequence from LysRS of eucarya and of most eubacteria, it has preserved a structural fold capable of aminoacylation (8, 9). Studies of M. jannaschii CysRS should likewise shed light on its origin, its relationship with known CysRS enzymes in the database, and its evolution in the development of the genetic code.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant GM56662 from the National Institutes of Health and by an institutional fund of Thomas Jefferson University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aurora R, Rose G D. Seeking an ancient enzyme in Methanococcus jannaschii using ORF, a program based on predicted secondary structure comparisons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2818–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böck A, Forchhammer K, Heider J, Baron C. Selenoprotein synthesis: an expansion of the genetic code. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:463–467. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho Y S, Kan Y W. In vivo aminoacylation of human and Xenopus suppressor tRNAs constructed by site-specific mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2185–2188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou Y M, Sterner T, Bhalla R. Evidence for a conserved relationship between an acceptor stem and a tRNA for aminoacylation. RNA. 1995;1:707–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou Y M, Westhof E, Giegé R. An unusual RNA tertiary interaction has a role for the specific aminoacylation of a transfer RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6776–6780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibba M, Curnow A W, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis: divergent routes to a common goal. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibba M, Morgan S, Curnow A W, Pridmore D R, Vothknecht U C, Gardner W, Lin W, Woese C R, Söll D. A euryarchaeal lysyl-tRNA synthetase: resemblance to class I synthetases. Science. 1997;278:1119–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibba M, Bono J L, Rosa P A, Söll D. Archaeal-type lysyl-tRNA synthetase in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14383–14388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Nagai Y, Sakai M, Ogura K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Ohfuku Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Kikuchi H. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 (supplement) DNA Res. 1998;5:147–155. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Nagai Y, Sakai M, Ogura K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Ohfuku Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Kikuchi H. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 1998;5:55–76. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H S, Vothknecht U C, Hedderich R, Celic I, Söll D. Sequence divergence of seryl-tRNA synthetases in archaea. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6446–6449. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6446-6449.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Venter J C, et al. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. . (Erratum, 394:101, 1998.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komatsoulis G A, Abelson J. Recognition of tRNA(Cys) by Escherichia coli cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7435–7444. doi: 10.1021/bi00080a014. . (Erratum, 32:13374.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kowalak J A, Dalluge J J, McCloskey J A, Stetter K O. The role of posttranscriptional modification in stabilization of transfer RNA from hyperthermophiles. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7869–7876. doi: 10.1021/bi00191a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipman R S A, Hou Y M. Aminoacylation of tRNA in the evolution of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13495–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pallanck L, Li S, Schulman L H. The anticodon and discriminator base are major determinants of cysteine tRNA identity in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7221–7223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreier A A, Schimmel P R. Transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase catalyzed deacylation of aminoacyl transfer ribonucleic acid in the absence of adenosine monophosphate and pyrophosphate. Biochemistry. 1972;11:1582–1589. doi: 10.1021/bi00759a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve J N, et al. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]