Abstract

Background

Little is known regarding how oral nicotine products (eg, nicotine pouches, lozenges) are marketed to consumers, including whether potential implicit reduced harm claims are used. In the current study, we explored the marketing claims present in a sample of direct-mail oral nicotine advertisements sent to US consumers (March 2018–August 2020).

Methods

Direct-mail ads (n=50) were acquired from Mintel and dual-coded for the following claims: alternative to other tobacco products, ability to use anywhere, spit-free, smoke-free and product does not contain tobacco leaf. We merged the coded data with Mintel’s volume estimate (number of mail pieces sent to consumers) and calculated the proportion of oral nicotine advertisements containing claims by category.

Results

Of the 38 million pieces of oral nicotine direct-mail sent to US consumers, most featured claims that the product could be used anywhere (84%, 31.8 million pieces); was an alternative to other tobacco products (69%, 26.1 million pieces); and did not contain tobacco leaf (eg, ‘tobacco leaf-free’, ‘simple’ approach of extracting nicotine from tobacco; 55%, 20.7 million pieces). A slightly smaller proportion contained claims that oral nicotine was ‘spit-free’ (52%, 19.8 million pieces) or ‘smoke-free’ (31%, 11.7 million pieces).

Conclusion

Our results provide an early indication of marketing claims used to promote oral nicotine. The strategies documented, particularly the use of language to highlight oral nicotine is tobacco-free, may covey these products as lower-risk to consumers despite the lack of evidence or proper federal authorisation that oral nicotine products are a modified-risk tobacco product. Future research is needed to examine consumer perceptions of such claims.

Keywords: non-cigarette tobacco products, surveillance and monitoring, public policy

Introduction

Oral nicotine products are a growing category of novel smokeless tobacco products sold in the USA. Unlike traditional smokeless tobacco, which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) narrowly defines as "cut, ground, powdered or leaf tobacco" commonly sold in the form of chew or moist snuff packaged loose in a can or pre-portioned pouches (eg, moist snuff pouches, snus),1 newer oral nicotine products do not contain tobacco leaf. Instead, they are made with nicotine extracted from tobacco leaf and sold in a variety of forms, including lozenges, gum, chewable tablets and nicotine pouches.2 3 Several major tobacco companies, including RJ Reynolds, Altria and Swedish Match, currently sell oral nicotine lozenges and pouches,4 which are frequently offered in a range of flavours and nicotine content.3 5

The evidence regarding whether non-combustible oral nicotine products are less harmful to consumers than traditional smokeless tobacco products is limited, and there is debate on whether these products could reduce the risk of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.6 7 Limiting this potential is the concern that flavoured oral nicotine products, particularly nicotine pouches, may appeal to youth and novice tobacco users.3 7 Further, little is known regarding how these products are currently advertised to consumers.8 A cursory review of online marketing suggests nicotine pouches are being promoted for their ability to be used anywhere and often described using terms such as ‘tobacco free’.3 It is possible that such claims could influence consumer harm perceptions, despite the limited evidence on the benefits or risks associated with product use.

As of December 2020, no oral nicotine product sold in the USA has been approved as a cessation medication and none have been granted FDA authorisation to be marketed as modified-risk tobacco products.9 The FDA has the authority to restrict the use of false or misleading claims in oral nicotine advertising that may suggest to consumers that there is reduced harm or risk in using the product.10 This is particularly important given evidence that exposure to implicit or explicit reduced-harm claims in tobacco advertising is associated with forming more positive, pro-tobacco attitudes, and thus, can lead to greater product use.11–15 While numerous studies document the claims used to promote smokeless tobacco products, like snus or moist-snuff pouches (eg, smoke-free, spit-free, use anywhere)16–18 and other non-combustible products like e-cigarettes (eg, ‘goodbye cigarette, hello vapour’),19–21 data on the type of claims used to promote oral nicotine products is limited.

In the current study, we address this gap and explore the claims made in direct-mail oral nicotine advertisements sent to US consumers. Direct-mail is an important marketing platform to reach and influence consumer behaviour,22 23 and the tactics used to target messages are often out of view of the public eye and purview of policymakers.23 In this study, we examine textual claims used to describe oral nicotine in direct-mail ads, including the presence of potential implicit reduced harm claims like ‘tobacco free’.

Methods

Data were drawn from Mintel, a subscription database of direct-mail received by a national opt-in panel of consumers. We examined all oral nicotine advertisements (n=50) sent to US consumers in Mintel’s panel between 1 March 2018 and 31 August 2020. A digital copy of each advertisement was downloaded from the Mintel database and coded for product claims. The product claims categories were informed by prior research on marketing for nicotine pouches and smokeless tobacco products3 16 17: alternative to other tobacco products, ability to use anywhere, spit-free, smoke-free and product does not contain tobacco leaf. Two researchers double-coded all advertisements. Reliability was substantial (α≥0.90), with any discrepancies in coding resolved through consensus. For each unique advertisement, we merged the coded data with Mintel’s volume estimates, which are weighted estimates based on the demographic distribution of Mintel’s panellists versus other known mailing lists. We calculated the proportion of oral nicotine advertisements containing claims by category.

Results

Between 1 March 2018 and 31 August 2020, tobacco companies sent an estimated 38 million pieces of oral nicotine direct-mail advertisements to US consumer households for Velo (RJ Reynolds) and On! (Altria) nicotine pouches and Revel lozenges (RJ Reynolds). Most direct-mail in this sample was sent by Altria (n=29 ads, 19.8 million pieces) versus RJ Reynolds (n=21 ads, 18.2 million pieces). The majority of direct-mail advertisements featured nicotine pouches (n=35 ads; 31.8 million pieces), while a smaller proportion featured lozenges (n=15 ads; 6.2 million pieces).

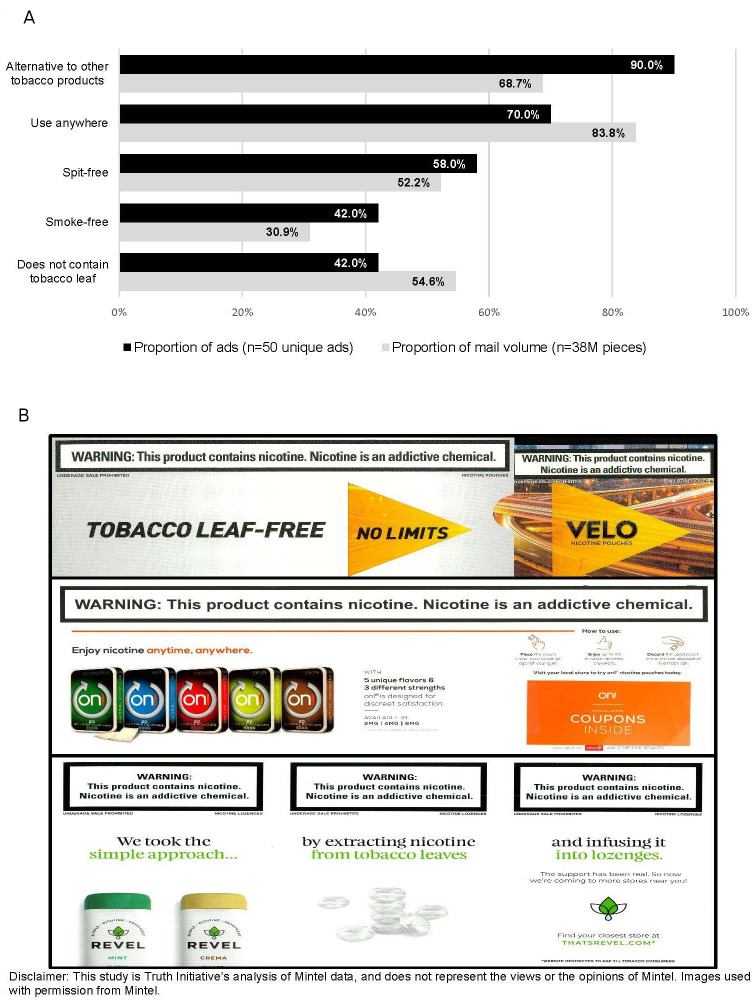

Figure 1A displays the proportion of unique advertisements (black bar) and the proportion of total mail volume sent (grey bar) containing claims by category. Out of the 50 unique advertisements, 90% contained claims that oral nicotine was an alternative to another tobacco product like cigarettes, traditional smokeless products or e-cigarettes (‘it’s the nicotine you’re used to without the chewing, smoking, spitting, odour’; ‘forget about the lighters, chargers and all that other stuff’) and 70% noted that the product could be used anywhere (‘for everywhere you’re headed’; ‘anytime, anywhere’; ‘discrete satisfaction’). Around half of ads contained claims that oral nicotine was spit-free (58%), smoke-free (42%) and did not contain tobacco leaf (42%, eg, ‘tobacco-leaf free’; ‘we took the simple approach of extracting nicotine from tobacco leaves’).

Figure 1.

Proportion of direct-mail oral nicotine advertising containing advertising claims by category (A) and exemplar advertisements (B).

With respect to volume, the largest proportion of the 38 million pieces of mail sent contained claims that the product could be used anywhere (84%, 31.8 million pieces), was an alternative to other tobacco products (69%, 26.1 million pieces), and did not contain tobacco leaf (55%, 20.7 million pieces). Figure 1B provides exemplar images across the three brands.

Discussion

Our study is one of the first to examine marketing claims used to promote the growing category of oral nicotine products to US consumers. We found that most of the oral nicotine direct-mail advertisements in our sample contained claims that the product could be used anywhere or was an alternative to an existing tobacco product. Such comparative claims have been previously used by tobacco companies to market new products,18 19 21 and it appears that oral nicotine companies are using a similar approach.

Claims that described the product as smoke-free or smoke-less appear to position oral nicotine as an alternative to cigarettes; while claims such as ‘mess free’ or ‘spit free’ may more directly make the case that the product is an alternative to traditional smokeless products. Interestingly, we observed that many ads also contrasted oral nicotine pouches and lozenges to e-cigarettes (eg, ‘forget about the chargers’). Use of these claims could signal an attempt to promote oral nicotine as a product to use in combination with existing tobacco products (ie, ‘dual’ use), particularly when other product use is prohibited or more complicated (eg, charging your e-cigarette device). Alternatively, the claims observed could differentiate oral nicotine as a substitute for other tobacco products. Future research is needed to understand how consumers perceive marketing claims in terms of product appeal, user satisfaction, and perceived risk of use, particularly given the evidence that comparative claims can imply a health benefit of a novel product.13–15

We also found that around half of oral nicotine direct-mail advertisements used claims like ‘tobacco leaf-free’ pouches (Velo) or highlighted the ‘simple approach’ of introducing extracted nicotine from tobacco leaf into lozenges (Revel). These descriptions are strikingly similar to terms used to market American Spirit cigarettes as ‘additive free’, ‘natural’ or ‘simple’.24–26 Use of these descriptors effectively constructed a comparative health halo around American Spirit versus other cigarettes26–30 and led to the FDA requirement that ‘additive free’ and ‘natural’ be removed from American Spirit marketing.31 It is possible that the presence of analogous terminology in oral nicotine marketing could suggest products are healthier and lower risk to consumers. Further, the use of language that signals a tobacco product is ‘free of a substance’ may meet one criterion of a unauthorised modified risk claim under FDA rules.9 Our findings underscore the need for future experimental studies to examine the influence of claims that oral nicotine is ‘tobacco-free’, made through a ‘simple’ process, and any other relevant ingredient-related claim (eg, ‘pharmaceutical grade’) on harm perceptions among consumers. Such evidence can further inform the FDA authority over false or misleading claims in tobacco product advertising.

Despite providing a snapshot of oral nicotine marketing, this study is limited to direct-mail advertising only. Further, the opt-in nature of the panel also limits our ability to capture the full scope of the oral nicotine marketplace. For example, certain brands are not represented in the analysis, like ZYN, which makes up over 86% of the market share for the nicotine pouch category.32 It is important to continue to track changes in oral nicotine advertising by product type and brand over time across advertising channels as the marketplace continues to rapidly shift (eg, Revel lozenges are now sold as Velo lozenges).33 While this study did not code specifically for flavours or coupons, they were present. Future studies should track the use of such appeals, particularly flavours, which could be used to attract young people in a similar fashion to the use of flavours to market cigarettes and cigars to youth.34 35

Our results provide an early indication of the claims tobacco companies use to market oral nicotine. Further evidence on oral nicotine marketing is needed, particularly given that these products are neither FDA-approved cessation medications nor authorised modified-risk tobacco products. Future research should also consider the visual presentation of oral nicotine advertisements, including how colour and imagery, like the product’s appearance (eg, white nicotine pouches), may work in concert with claims to promote oral nicotine as ‘clean’ and modern, potentially expanding the appeal of oral nicotine to women and others who typically rejected tobacco-leaf products like traditional smokeless tobacco.36 Collectively, these findings can be used to inform the FDA’s authority to prohibit manufacturers from making misleading ‘modified risk’ or reduced harm risk claims without proper approval.

What this paper adds.

Oral nicotine products are a growing novel category of tobacco products in the USA; however, little is known regarding the range of marketing claims used to promote oral nicotine products.

Oral nicotine products are prominently marketed as alternatives to other tobacco products in direct-mail advertising. A substantial number of oral nicotine direct-mail ads also included potential reduced harm claims that promote the product as tobacco-leaf free and could influence consumer harm perceptions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the quality of the publication of this research.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ShyanikaRose

Contributors: This study was conceptualised by LC and MP. LC led and conducted the analyses, created visualisations, drafted the original paper and provided final review/edits. MP collaborated on designing methods, provided oversight of data collection/cleaning and drafted the original paper. BR led data curation and background literature research. SY provided data curation and background literature research support. SWR provided technical subject matter expertise and was involved with all aspects of the research. BS provided research oversight and provided final review/edits. All authors provided final review and edits of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Truth Initiative.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Food and Drug Administration . Smokeless tobacco products, including dip, snuff, Snus, and chewing tobacco, 2020. Available: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/smokeless-tobacco-products-including-dip-snuff-snus-and-chewing-tobacco

- 2. Food and Drug Administration . Dissolvable tobacco products, 2018. Available: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/dissolvable-tobacco-products

- 3. Robichaud MO, Seidenberg AB, Byron MJ. Tobacco companies introduce 'tobacco-free' nicotine pouches. Tob Control 2020;29:e145–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kary T, Gretler C. Big tobacco hopes oral nicotine pouches fill the Vaping void. Bloomberg Businessweek, 2020. Available: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-17/big-tobacco-hopes-oral-nicotine-pouches-fill-the-vaping-void

- 5. Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerström K, et al. Initial information on a novel nicotine product. Am J Addict 2020;29:279–86. 10.1111/ajad.13020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benowitz NL. Emerging nicotine delivery products. Implications for public health. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:231–5. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-433PS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hatsukami DK, Carroll DM. Tobacco harm reduction: past history, current controversies and a proposed approach for the future. Prev Med 2020;140:106099. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Czaplicki L, Rahman B, Simpson R, et al. Going smokeless: promotional features and reach of U.S. smokeless tobacco Direct-mail advertising (July 2017-August 2018). Nicotine Tob Res 2020:ntaa255. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. United States Code . Title 21: food and drugs, chapter 9 federal food, drug, and cosmetic act, subchapter IX tobacco products, section 387k – modified risk tobacco products. Available: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2012-title21/html/USCODE-2012-title21-chap9-subchapIX-sec387k.htm

- 10. Food and Drug Administration . Tobacco-Related health fraud. food and drug administration, 2019. Available: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/health-information/health-fraud

- 11. Baig SA, Byron MJ, Lazard AJ, et al. "Organic," "natural," and "additive-free" cigarettes: comparing the effects of advertising claims and disclaimers on perceptions of harm. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:933–9. 10.1093/ntr/nty036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elton-Marshall T, Fong GT, Zanna MP, et al. Beliefs about the relative harm of "light" and "low tar" cigarettes: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tob Control 2010;19 Suppl 2:i54–62. 10.1136/tc.2008.029025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Herzog TA, et al. E-cigarette advertising exposure and implicit attitudes among young adult non-smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;163:134–40. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanders-Jackson A, Tan ASL, Yie K. Effects of health-oriented descriptors on combustible cigarette and electronic cigarette packaging: an experiment among adult smokers in the United States. Tob Control 2018;27:534–41. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaufman AR, Grenen E, Grady M, et al. Perceptions of harm and addiction of snus: an exploratory study. Psychol Addict Behav 2016;30:895–903. 10.1037/adb0000230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health 2010;100:78–87. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hendlin YH, Veffer JR, Lewis MJ, et al. Beyond the brotherhood: Skoal Bandits' role in the evolution of marketing moist smokeless tobacco pouches. Tob Induc Dis 2017;15:46. 10.1186/s12971-017-0150-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Timberlake DS, Pechmann C, Tran SY, et al. A content analysis of camel Snus advertisements in print media. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:431–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntr020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klein EG, Berman M, Hemmerich N, et al. Online e-cigarette marketing claims: a systematic content and legal analysis. Tob Regul Sci 2016;2:252–62. 10.18001/TRS.2.3.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wagoner KG, Berman M, Rose SW, et al. Health claims made in vape shops: an observational study and content analysis. Tob Control 2019;28:e119–25. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grana RA, Ling PM. "Smoking revolution": a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:395–403. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis MJ, Ling PM. "Gone are the days of mass-media marketing plans and short term customer relationships": tobacco industry direct mail and database marketing strategies. Tob Control 2016;25:430–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis MJ, Yulis SG, Delnevo C, et al. Tobacco industry direct marketing after the master settlement agreement. Health Promot Pract 2004;5:75S–83. 10.1177/1524839904264596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pearson JL, Richardson A, Feirman SP, et al. American spirit pack descriptors and perceptions of harm: a Crowdsourced comparison of modified packs. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1749–56. 10.1093/ntr/ntw097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iles IA, Pearson JL, Lindblom E, et al. "Tobacco and water": testing the health halo effect of natural American spirit cigarette ads and its relationship with perceived absolute harm and use intentions. Health Commun 2020;2020:1–12. 10.1080/10410236.2020.1712526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moran MB, Pearson JL. Real. simple. deadly. A pilot test of consumer harm perceptions in response to natural American spirit advertising. tob regul sci 2019;5:360–8. 10.18001/TRS.5.4.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pearson JL, Johnson A, Villanti A, et al. Misperceptions of harm among natural American spirit smokers: results from wave 1 of the population assessment of tobacco and health (path) study (2013-2014). Tob Control 2017;26:e61–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gratale SK, Maloney EK, Sangalang A, et al. Influence of natural American spirit advertising on current and former smokers' perceptions and intentions. Tob Control 2018;27:498–504. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Epperson AE, Averett PE, Blanchflower T, et al. "The packaging is very inviting and makes smokers feel like they're more safe": the meanings of natural american spirit cigarette pack design to adult smokers. Health Educ Behav 2019;46:260–6. 10.1177/1090198118820099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pearson JL, Moran M, Delnevo CD, et al. Widespread belief that organic and Additive-Free tobacco products are less harmful than regular tobacco products: results from the 2017 US health information national trends survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:970–3. 10.1093/ntr/ntz015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gratale SK, Maloney EK, Cappella JN. Regulating language, not inference: an examination of the potential effectiveness of natural American spirit advertising restrictions. Tob Control 2019;28:e43–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller Lo EJ, et al. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011-2019. Nicotine Tob Res 2020. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa239. [Epub ahead of print: 26 Nov 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. News A. Reynolds Submits first VELO dissolvable nicotine lozenge Premarket tobacco product applications. associated press, 2020. Available: https://apnews.com/press-release/pr-newswire/b2b866794ca7f295b9ca00e6185512d9

- 34. Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, et al. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff 2005;24:1601–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kostygina G, Ling PM. Tobacco industry use of flavourings to promote smokeless tobacco products. Tob Control 2016;25:ii40–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Curry LE, Pederson LL, Stryker JE. The changing marketing of smokeless tobacco in magazine advertisements. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:540–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntr038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]