Abstract

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius can be transmitted between dogs and their owners and can cause opportunistic infections in humans. Whole genome sequencing was applied to identify the relatedness between isolates from human infections and isolates from dogs in the same households. Genome SNP diversity and distribution of plasmids and antimicrobial resistance genes identified related and unrelated isolates in both households. Our study shows that within-host bacterial diversity is present in S. pseudintermedius, demonstrating that multiple isolates from each host should preferably be sequenced to study transmission dynamics.

Keywords: S. pseudintermedius, transmission, One health, whole genome sequencing, zoonotic, bacterial diversity

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is both a commensal and opportunistic pathogen in dogs. Infections in humans are occasionally found; however, in humans, S. pseudintermedius might be underdiagnosed as it can be misidentified as Staphylococcus aureus or Staphylococcus intermedius [1,2]. Human infections with S. pseudintermedius are generally considered to be of zoonotic origin [3], although in exceptional cases no dog contact is reported [4]. Dog-to-human transmission of S. pseudintermedius has been reported, in which isolates from dogs and their owners were indistinguishable based on multi-locus sequence typing and pulsed field gel electrophoresis [4,5]. Nevertheless, carriage rates of S. pseudintermedius in humans remain very low compared to the carriage rates of dogs, even in dog owning households [6]. Longitudinal studies on methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) showed that dogs carried MRSP for prolonged periods of time (several months), whereas carriage in humans was rare and short-term. Human carriage is therefore considered to be contamination instead of colonization, though opportunistic infections in humans can occur [5,7]. In longitudinal studies, MRSP was found in the environment and in other dogs in the household [7,8]. Generally, isolates within one household belong to the same sequence type (ST), although occasionally different STs can be found in the same household [5]. Most studies on dog-to-human transmission of S. pseudintermedius include only a single isolate from each host. This approach might lead to misinterpretations when within-host bacterial diversity exists. We used whole genome sequencing of multiple isolates from dogs to investigate within-household transmission and bacterial diversity of S. pseudintermedius in two unrelated human infections caused by S. pseudintermedius and the dogs in these households.

2. Results

2.1. Household 1

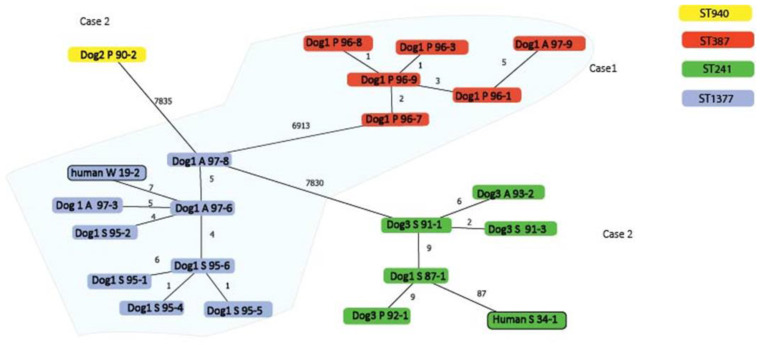

Patient 1 was a 64-year-old woman with a wound infection on her foot in June 2016. One dog, suffering from a chronic skin condition, was present in the household. S. pseudintermedius was isolated from three sampling sites and multiple isolates were selected for genome analysis (n = 5 from each site) based on morphological colony differences. This provided insight into the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in isolates from this dog. Dog isolates belonged to two clades that differentiated by 6913 core-genome SNPs. One clade consisted of six dog isolates (obtained from perineum and axillary) that displayed a very low level of diversity (differing by up to 5 SNPs) and belonged to ST387 (Figure 1). All six dog isolates carried the blaZ resistance gene and no plasmid was detected.

Figure 1.

Minimum spanning tree of core-genomes showing the phylogenetic relationship between isolates from the two households, with the number of SNPs indicated on the branches. Isolates are identified by host species, followed by isolation site A = axillary, P = perineum, S = skin, W = wound, and lastly followed by the last three digits of their isolate number. Isolates from household 1 are shown against a blue background. Isolates from household 2 are shown against a white background. Isolates with no SNP differences are not shown.

In the other clade, the human isolate and nine of the dog isolates, obtained from the skin and axillary, differentiated between 0 and 7 core-genome SNPs and belonged to ST1337 (Figure 1). All isolates carried the resistance gene tet(M), and all but one (16S06095-5) isolate carried the blaZ gene. The human isolate carried the blaZ and tet(M) resistance genes, no plasmid sequences, and differed by 7 SNPs from a dog isolate from the same household that also carried these genes and no plasmid sequences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Isolate characteristics.

| Isolate | Origin | Isolation Date | Specimen | MLST | Resistance Genes | Mobile Elements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household 1 | ||||||||||

| 16S06119-2 | human | June 2016 | wound | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06095-1 | dog 1 | June 2016 | skin | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06095-2 | dog 1 | June 2016 | skin | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06095-4 | dog 1 | June 2016 | skin | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06095-5 | dog 1 | June 2016 | skin | 1377 | tet(M) | |||||

| 16S06095-6 | dog 1 | June 2016 | skin | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06097-3 | dog 1 | June 2016 | axillary | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06097-6 | dog 1 | June 2016 | axillary | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06097-7 | dog 1 | June 2016 | axillary | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06097-8 | dog 1 | June 2016 | axillary | 1377 | blaZ | tet(M) | ||||

| 16S06096-1 | dog 1 | June 2016 | perineum | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| 16S06096-3 | dog 1 | June 2016 | perineum | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| 16S06096-7 | dog 1 | June 2016 | perineum | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| 16S06096-8 | dog 1 | June 2016 | perineum | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| 16S06096-9 | dog 1 | June 2016 | perineum | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| 16S06097-9 | dog 1 | June 2016 | axillary | 387 | blaZ | |||||

| Household 2 | ||||||||||

| 17S01534-1 | human | July 2017 | skin | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222 |

| 17S01587-1 | dog 1 | July 2017 | skin | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01591-1 | dog 3 | July 2017 | skin | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01591-2 | dog 3 | July 2017 | skin | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01591-3 | dog 3 | July 2017 | skin | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01592-1 | dog 3 | July 2017 | perineum | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01593-2 | dog3 | July 2017 | axillary | 241 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222; 2,7 kb plasmid |

| 17S01590-2 | dog 2 | July 2017 | perineum | 940 | blaZ | sat4 | cat(pC221) | erm(B) | ant(6)-Ia,aph(3’)-III | PRE25-like; p222 |

2.2. Household 2

Patient 2 was a 63-year-old woman with an infected skin ulcer in July 2017. Three dogs were present in the household. No clinical conditions were reported for the dogs. All dogs were found to be positive for S. pseudintermedius, but not for all sites. Selection of morphologically different colonies resulted in one isolate from the skin of dog 1, one isolate from the perineum of dog 2, and 5 isolates from the skin (n = 3), the perineum (n = 1), and axillary (n = 1) of dog 3.

The human isolate, and all isolates from dog 1 and dog 3, belonged to ST241. The ST241 isolates from dog 1 and dog 3 differed by between 0 and 9 SNPs, whereas the human isolate showed 87 SNPs differed from its closest related canine isolate (dog 1). In the MS-tree, the SNPs were filtered for recombination and the 87 SNPs between dog and human isolates were not clustered in one location on the genome, indicating that these SNPs were not the result of a single recombination event. Isolate 17S01590-2 of dog 2 displayed 7835 SNPs compared to its closest relative, belonged to ST940, and was considered genetically unrelated to other isolates (Figure 1). All isolates of household 2 carried the p222 plasmid (coverage 97%, identity 99%) [9] and other predicted plasmid sequences. The BLASTn analysis of these contigs identified sequence homology with the PRE-25-like element [10], carrying sat4; ant(6)-Ia; aph(3’)-III; cat(pC221); and erm(B) resistance genes (coverage 67.9%, identity 99.9%) in all these isolates. A 2.7 kb plasmid sequence in all ST241 dog isolates belonged to the rep21 gene plasmid family (Table 1).

3. Discussion

Whole genome sequencing of S. pseudintermedius isolates from two unrelated human infections showed very low SNP diversity with canine isolates of colonized dogs in both households. The isolates retrieved from the human infections were considered genetically related to the isolates of the dogs. This is in accordance with longitudinal studies on MRSP showing that generally similar or indistinguishable S. pseudintermedius isolates can be present in humans, dogs, and environmental samples within the same household [5,7].

This study analyzed multiple dog isolates in one household, as it is known that inferring transmission by sequencing single colonies can be hindered by within-host bacterial diversity [11,12]. The SNP diversity in the genomes between several of the studied dog isolates in household 1 was very low, most likely reflecting the diversity that occurs during colonization. However, the genomes with higher SNP diversity (6913 and 7835) indicated that dogs were colonized with genetically unrelated isolates. This highlights the need for sequencing multiple isolates from dogs to investigate household transmission. SNP diversity correlated with assigned MLST sequence types as isolates from the same ST generally carried less than 10 SNP differences, whereas isolates with different STs differentiated by either 6913 or 7835 SNPs. Sequence type and SNP differences between MSSP isolates of different body sites were also observed, with dogs being positive for either one or multiple body sites, with different frequencies for each site [13]. This study also showed that isolates presenting morphological differences can be very closely related.

Mobile genetic elements were identified in all isolates from household 2: the p222 [9] and the PRE25-like elements. The presence of these elements in CC241 isolates, and the presence of this clonal complex in human isolates, has been previously reported [14]. The plasmid present in dog isolates in household 2 was absent in the ST241 human isolate and shows that gain or loss of a plasmid occurred among highly genetically related isolates. This is in line with observed gene loss or acquisition events in S. aureus, which is involved in the host jump of CC398 from livestock to human, and there are other examples of gene acquisitions in S. aureus that have facilitated adaptations to other animal species [15,16]. The mobile elements in S. pseudintermedius carrying multiple resistance genes and potential virulence genes are important epidemiological markers to monitor, as they can act as a reservoir for transmission to humans [14]. Nevertheless, the genome comparison showed that ST241 isolates from dogs in household 2 were more closely related to each other (<10 SNPs) than to the human isolate (87 SNPs). The higher SNP diversity might suggest that evolution occurred over the course of infection, but as the patient was only sampled once this could not be confirmed. Furthermore, as the dogs in this study were sampled within the same month the patients were hospitalized, it is impossible to infer the direction and timing of transmission. It would be interesting to have multiple samples from the human to see if the diversity observed in the dog is also present in human hosts. Larger studies using whole genome sequencing combined with epidemiological data would be of interest to determine if SNP differences between related isolates are common and can indicate the direction of transmission.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

S. pseudintermedius isolates from two human patients were obtained from the Amsterdam UMC location AMC in the Netherlands. Both patients were dog owners and gave their consent for samples from their dog(s) to be taken. Dogs (one in household 1 and three in household 2) were sampled by the owner at three body sites (skin, perineum, and axillary) within a month of confirmed infection of the owner. Samples were inoculated on sheep blood agar (bioTRADING, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands) and, after overnight incubation at 37 °C, presumptive colonies were identified as S. pseudintermedius by Maldi-TOF (Bruker MALDI Biotyper, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). In each sample, all morphologically distinct colonies were selected for identification, resulting in multiple isolates per sample and per dog. The characteristics of the isolates are shown in Table 1.

4.2. Molecular Analysis

For whole genome sequencing, DNA was isolated using the Qiagen DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). DNA libraries were prepared with the Illumina Nextera kit according to manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced with NextGen paired-end sequencing with 150 bp reads (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Genomes were assembled with SPAdes v3.10.1 [17] and annotated using Prokka v1.13 [18]. Resistance genes were determined using Resfinder [19] and Multi Locus Sequence Type (MLST) was determined with MLSTFinder [20]. Core–gene alignment was performed using Parsnp v1.2 [21]. Gubbins was used to filter recombination regions [22]. SNPs were extracted from the core–gene alignment using SNP-sites v2.4.0 [23] and a minimum-spanning tree (MST) was constructed using the goeBURST algorithm and visualized using Phyloviz v2.0 [24]. Plasmid content was determined using RFPlasmid with a minimum plasmid prediction cut-off of 0.6 and a minimum length of 1kb [25]. The plasmid contigs were characterized using BLASTn.

Isolates containing the combination of resistance genes ant(6)-Ia; aph(3’)-III; cat(pC221); and erm(B) were analyzed for the presence of the pRE25-like element. This element has been previously described in S. pseudintermedius and was identified using Geneious version 2020.1.1 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand).

4.3. Data Availability

Whole genome sequence reads of the canine isolates have been uploaded in ENA under bio project PRJEB53745 and the human isolates were previously uploaded under the following accession numbers: 17S01534-1 (GCA_903992455.1), 16S06119-2 (GCA_903991985.1).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D., E.M.B. and J.A.W.; methodology A.W., M.S. and A.J.T.; software, L.v.d.G.-v.B. and A.L.Z.; validation, B.D., E.M.B. and J.A.W.; formal analysis, A.W, L.v.d.G.-v.B. and B.D.; investigation, A.W., L.v.d.G.-v.B. and B.D.; resources, C.E.V.; data curation, A.W. and B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W.; writing—review and editing, A.W.; L.v.d.G.-v.B., B.D., E.M.B. and J.A.W.; visualization: L.v.d.G.-v.B. and A.W.; supervision, B.D., E.M.B. and J.A.W.; project administration, B.D., E.M.B. and J.A.W.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to an outdated patient information system.

Data Availability Statement

Whole genome sequence reads of the canine isolates have been uploaded in ENA under the bio project PRJEB53745 and of the human isolates had previously been uploaded under the following accession numbers: 17S01534-1 (GCA_903992455.1), 16S06119-2 (GCA_903991985.1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Börjesson S., Gómez-Sanz E., Ekström K., Torres C., Grönlund U. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Can be Misdiagnosed as Staphylococcus aureus in Humans with Dog Bite Wounds. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol Infect. Dis. 2015;34:839–844. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2300-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viau R., Hujer A.M., Hujer K.M., Bonomo R.A., Jump R.L.P. Are Staphylococcus intermedius Infections in Humans Cases of Mistaken Identity? A Case Series and Literature Review: Table 1. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015;2:ofv110. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somayaji R., Rubin J.E., Priyantha M.A., Church D. Exploring Staphylococcus pseudintermedius: An Emerging Zoonotic Pathogen? Future Microbiol. 2016;11:1371–1374. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano C., Rezusta A., Ferrer I., Pérez-Laguna V., Zarazaga M., Ruiz-Ripa L., Revillo M.J., Torres C. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Human Infection Cases in Spain: Dog-to-Human Transmission. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:268–270. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laarhoven L.M., de Heus P., van Luijn J., Duim B., Wagenaar J.A., van Duijkeren E. Longitudinal Study on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Households. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuny C., Layer-Nicolaou F., Weber R., Köck R., Witte W. Colonization of Dogs and Their Owners with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Households, Veterinary Practices, and Healthcare Facilities. Microorganisms. 2022;10:677. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Røken M., Iakhno S., Haaland A.H., Wasteson Y., Bjelland A.M. Transmission of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Spp. from Infected Dogs to the Home Environment and Owners. Antibiotics. 2022;11:637. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11050637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Duijkeren E., Kamphuis M., van der Mije I.C., Laarhoven L.M., Duim B., Wagenaar J.A., Houwers D.J. Transmission of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius between Infected Dogs and Cats and Contact Pets, Humans and the Environment in Households and Veterinary Clinics. Vet. Microbiol. 2011;150:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wladyka B., Piejko M., Bzowska M., Pieta P., Krzysik M., Mazurek Ł., Guevara-Lora I., Bukowski M., Sabat A.J., Friedrich A.W., et al. A Peptide Factor Secreted by Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Exhibits Properties of Both Bacteriocins and Virulence Factors. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14569. doi: 10.1038/srep14569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang J.H., Hwang C.Y. First Detection of Multiresistance PRE25-like Elements from Enterococcus Spp. in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Isolated from Canine Pyoderma. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020;20:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worby C.J., Lipsitch M., Hanage W.P. Within-Host Bacterial Diversity Hinders Accurate Reconstruction of Transmission Networks from Genomic Distance Data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:1003549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Didelot X., Gardy J., Colijn C. Bayesian Inference of Infectious Disease Transmission from Whole-Genome Sequence Data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014;31:1869–1879. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanselman B.A., Kruth S.A., Rousseau J., Weese J.S. Coagulase Positive Staphylococcal Colonization of Humans and Their Household Pets. Can. Vet. J. 2009;50:954–958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegener A., Broens E.M., van der Graaf-van Bloois L., Zomer A.L., Visser C.E., van Zeijl J., van der Meer C., Kusters J.G., Friedrich A.W., Kampinga G.A., et al. Absence of Host-Specific Genes in Canine and Human Staphylococcus pseudintermedius as Inferred from Comparative Genomics. Antibiotics. 2021;10:854. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matuszewska M., Murray G.G., Ba X., Wood R., Holmes M.A., Weinert L.A. Stable Antibiotic Resistance and Rapid Human Adaptation in Livestock-Associated MRSA. eLife. 2022;11:e74819. doi: 10.7554/eLife.74819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haag A.F., Fitzgerald J.R., Penadés J.R. Staphylococcus aureus in Animals. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019:7. doi: 10.1128/MICROBIOLSPEC.GPP3-0060-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., Aarestrup F.M., Larsen M.V. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen M.V., Cosentino S., Rasmussen S., Friis C., Hasman H., Marvig R.L., Jelsbak L., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Ussery D.W., Aarestrup F.M., et al. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Total-Genome-Sequenced Bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treangen T.J., Ondov B.D., Koren S., Phillippy A.M. The Harvest Suite for Rapid Core-Genome Alignment and Visualization of Thousands of Intraspecific Microbial Genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croucher N.J., Page A.J., Connor T.R., Delaney A.J., Keane J.A., Bentley S.D., Parkhill J., Harris S.R. Rapid Phylogenetic Analysis of Large Samples of Recombinant Bacterial Whole Genome Sequences Using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page A.J., Taylor B., Delaney A.J., Soares J., Seemann T., Keane J.A., Harris S.R. SNP-Sites: Rapid Efficient Extraction of SNPs from Multi-FASTA Alignments. Microb. Genom. 2016;2:e000056. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nascimento M., Sousa A., Ramirez M., Francisco A.P., Carriço J.A., Vaz C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: Providing Scalable Data Integration and Visualization for Multiple Phylogenetic Inference Methods. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:128–129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Graaf-Van Bloois L., Wagenaar J.A., Zomer A.L. RFPlasmid: Predicting Plasmid Sequences from Short Read Assembly Data Using Machine Learning. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Whole genome sequence reads of the canine isolates have been uploaded in ENA under the bio project PRJEB53745 and of the human isolates had previously been uploaded under the following accession numbers: 17S01534-1 (GCA_903992455.1), 16S06119-2 (GCA_903991985.1).