Abstract

Background

A growing body of research shows the promise and efficacy of technology‐based or digital interventions in improving the health and well‐being of survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV). In addition, mental health comorbidities such as anxiety, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression occur three to five times more frequently in survivors of IPV than non‐survivors, making these comorbidities prominent targets of technology‐based interventions. Still, research on the long‐term effectiveness of these interventions in reducing IPV victimization and adverse mental health effects is emergent. The significant increase in the number of trials studying technology‐based therapies on IPV‐related outcomes has allowed us to quantify the effectiveness of such interventions for mental health and victimization outcomes in survivors. This meta‐analysis and systematic review provide critical insight from several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the overall short and long‐term impact of technology‐based interventions on the health and well‐being of female IPV survivors.

Objectives

To synthesize current evidence on the effects of technology‐based or digital interventions on mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, and PTSD) and victimization outcomes (physical, psychological, and sexual abuse) among IPV survivors.

Search Methods

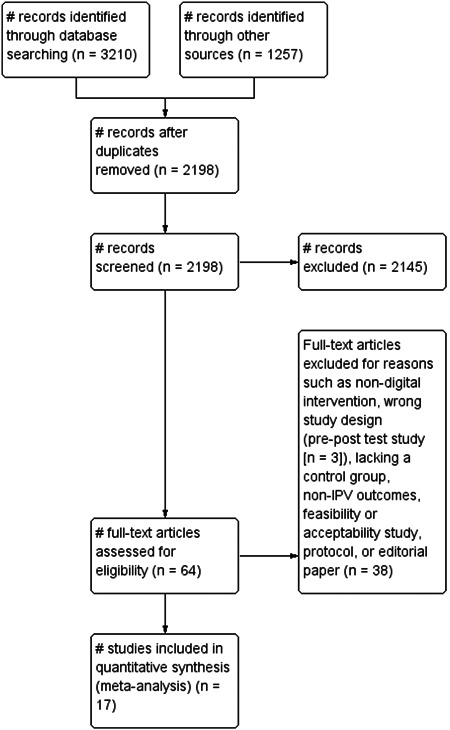

We examined multiple traditional and grey databases for studies published from 2007 to 2021. Traditional databases (such as PubMed Central, Web of Science, CINAHL Plus, and PsychINFO) and grey databases were searched between April 2019 and February 2021. In addition, we searched clinical trial registries, government repositories, and reference lists. Authors were contacted where additional data was needed. We identified 3210 studies in traditional databases and 1257 from grey literature. Over 2198 studies were determined to be duplicates and eliminated, leaving 64 studies after screening titles and abstracts. Finally, 17 RCTs were retained for meta‐analysis. A pre‐registered protocol was developed and published before conducting this meta‐analysis.

Selection Criteria

We included RCTs targeting depression, anxiety, PTSD outcomes, and victimization outcomes (physical, sexual, and psychological violence) among IPV survivors using a technology‐based intervention. Eligible RCTs featured a well‐defined control group. There were no study restrictions based on participant gender, study setting, or follow‐up duration. Included studies additionally supplied outcome data for calculating effect sizes for our desired outcome. Studies were available in full text and published between 2007 and 2021 in English.

Data Collection and Analysis

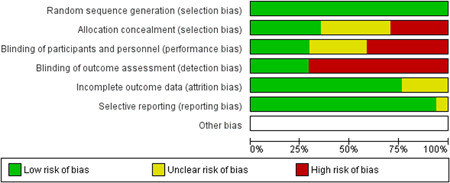

We extracted relevant data and coded eligible studies. Using Cochrane's RevMan software, summary effect sizes (Outcome by Time) were assessed using an independent fixed‐effects model. Standardized mean difference (SMD) effect sizes (or Cohen's d) were evaluated using a Type I error rate and an alpha of 0.05. The overall intervention effects were analyzed using the Z‐statistic with a p‐value of 0.05. Cochran's Q test and Higgins' I 2 statistics were utilized to evaluate and confirm the heterogeneity of each cumulative effect size. The Cochrane risk of bias assessment for randomized trials (RoB 2) was used to assess the quality of the studies. Campbell Systematic Reviews registered and published this study's protocol in January 2021. No exploratory moderator analysis was conducted; however, we report our findings with and without outlier studies in each meta‐analysis.

Main Results

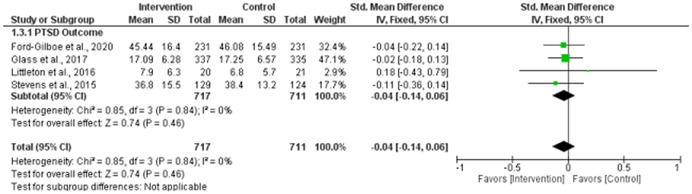

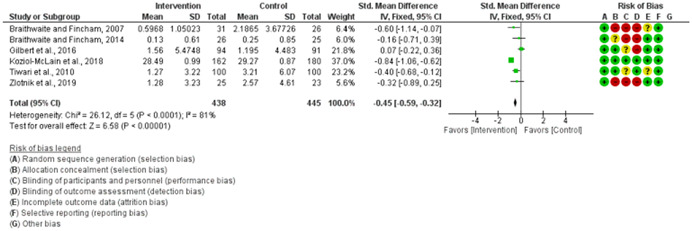

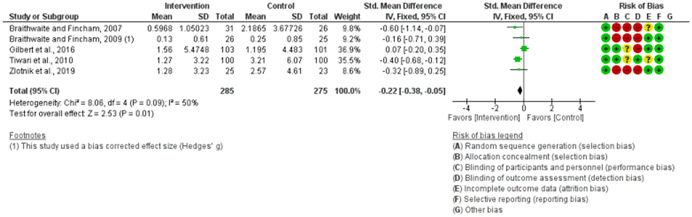

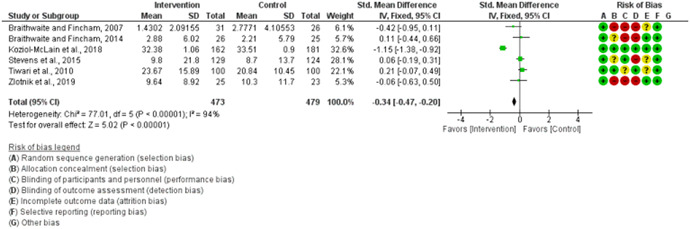

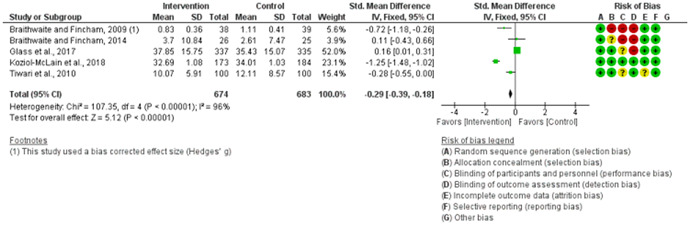

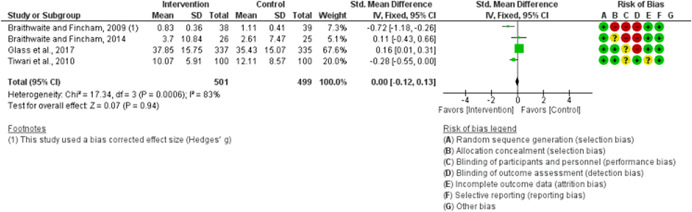

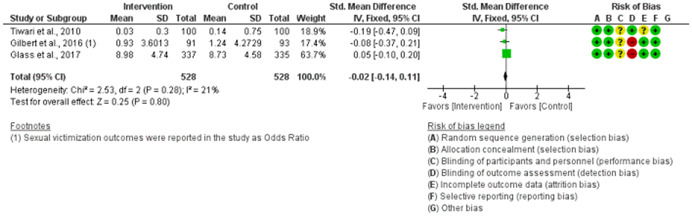

Pooled results from 17 RCTs yielded 18 individual effect size comparisons among 4590 survivors (all females). Survivors included college students, married couples, substance‐using women in community prisons, pregnant women, and non‐English speakers, and sample sizes ranged from 15 to 672. Survivors' ages ranged from 19 to 41.5 years. Twelve RCTs were conducted in the United States and one in Canada, New Zealand, China (People's Republic of), Kenya, and Australia. The results of this meta‐analysis found that technology‐based interventions significantly reduced depression among female IPV survivors at 0–3 months only (SMD = −0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.17 to −0.00), anxiety among IPV survivors at 0–3 months (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI = −0.42 to −0.13, p = 0.00, I 2 = 25%), and physical violence victimization among IPV survivors at 0–6 months (SMD = −0.22, 95% CI = −0.38 to −0.05). We found significant reductions in psychological violence victimization at 0–6 months (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI = −0.47 to −0.20) and at >6 months (SMD = −0.29, 95% CI = −0.39 to −0.18); however, at both time points, there were outlier studies. At no time point did digital interventions significantly reduce PTSD (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI = −0.14 to 0.06, p = .46, I 2 = 0%), or sexual violence victimization (SMD = −0.02, 95% CI = −0.14 to 0.11, I 2 = 21%) among female IPV survivors for all. With outlier studies removed from our analysis, all summary effect sizes were small, and this small number of comparisons prevented moderator analyses.

Authors' Conclusions

The results of this meta‐analysis are promising. Our findings highlight the effectiveness of IPV‐mitigating digital intervention as an add‐on (not a replacement) to traditional modalities using a coordinated response strategy. Our findings contribute to the current understanding of “what works” to promote survivors' mental health, safety, and well‐being. Future research could advance the science by identifying active intervention ingredients, mapping out intervention principles/mechanisms of action, best modes of delivery, adequate dosage levels using the treatment intensity matching process, and guidelines to increase feasibility and acceptability.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Technology‐based interventions reduce depression, anxiety and physical violence victimization among intimate partner violence survivors in the short term

Compared to non‐technology‐based interventions for survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV), technology‐based interventions are effective in reducing adverse mental health and IPV outcomes. We found effect sizes that were small to moderate that should be interpreted with care.

1.2. What is this review about?

The spread of IPV digital interventions provides a compelling reason to collect evidence of their intervention and treatment effects. Technology‐based therapies come in many forms, including phone and web‐based decision aids, conversational agents (chatbots), text message interventions, online support groups, and telehealth services.

Although technology‐based therapies have become acceptable, practical and feasible for supporting the health and well‐being of IPV survivors, little is known about the size of their cumulative effects on IPV survivors' health and well‐being.

Furthermore, it is unknown how much, for whom and how long these effects last. The extent to which the type of digital intervention (smartphone vs. web‐based) contributes to this impact is also unknown.

This review and meta‐analysis aim to fill these gaps in our understanding. Clarity on the pros and cons of digital IPV interventions have implications for intervention design, user engagement and adoption among IPV survivors. Only a few digital IPV therapies have been tested in (sub‐optimal) “real‐world” situations. Even fewer attempts have been made to cumulate the intervention impact of digital interventions on survivors' mental health, despite the commonality of depression, anxiety disorders and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among IPV survivors.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the effect of technology‐based or digital interventions on the mental health outcomes—depression, anxiety and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—and victimization (physical, psychological, and sexual abuse) of intimate partner violence (IPV) survivors.

1.3. What studies are included?

We analyzed 17 experimental studies (randomized controlled trials), each with well‐defined control groups. The studies were published between 2007 and 2021, most published in 2016. Twelve of the 17 studies were conducted in the USA. One study each was included from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Kenya and China. Most studies had a moderate risk of bias.

1.4. What are the main findings of this review?

Results from randomized controlled trials indicate that digital and technology‐based interventions significantly reduce depression (up to 3 months), anxiety (up to 3 months), and physical violence victimization (at 6 months post‐intervention) among female IPV survivors. Results from studies on psychological violence victimization are inconclusive.

These effects, however, appear to fade over time for these outcomes. Also, the same digital interventions have no significant effect on PTSD or sexual violence victimization experiences at any time point.

Overall, digital treatments provide concrete benefits in terms of providing survivors with meaningful support, even if only temporarily, especially during increased emotional, mental and relationship distress.

1.5. What do the findings of the review mean?

This systematic review finds that digital interventions work. Intervention funders and violence prevention policymakers can use these results to set a baseline effect size for IPV digital interventions. These results can also inform health policy, to support providers' reimbursement for offering or recommending digital interventions backed by evidence.

Results from the meta‐analysis can be used to bolster calls for the inclusion of IPV digital therapies as add‐on therapeutic devices during routine IPV screening of girls and women (ages 14–46 years).

These findings also help service providers to decide if digital approaches are beneficial, dependable and safe for assisting survivors' emotional well‐being.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies from 2007 to 2021.

2. BACKGROUND

Intimate partner violence (IPV) remains a persistent public health, social justice, and human rights concern. IPV has numerous well‐known effects on the physical, social, emotional, and economic condition of survivors, their families, and communities (Black et al., 2011; Breiding et al., 2014; Nathanson et al., 2012). However, the mental health consequences of experiencing partner abuse might be the most severe and longest‐lasting. Several studies show moderate to strong positive correlations between experiencing IPV and depression and anxiety (Beydoun et al., 2012; Mechanic et al., 2008; Tol et al., 2019). Furthermore, 30%‐80% of IPV survivors meet criteria for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Nathanson et al., 2012).

In some meta‐analyses, IPV survivors are three to five times more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms than non‐survivors (Golding, 1999; Lagdon et al., 2014). In addition, untreated mental health issues limit survivors' access to medical care and treatment, create barriers to holistic therapy, diminish their overall quality of life, and can foster a culture of chronic poly‐victimization and co‐morbidities among survivors (Johnson et al., 2011; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2009; Nathanson et al., 2012). Therefore, mental health and victimization outcomes remain stable targets for current interventions (Ellsberg et al., 2015; Gevers & Dartnall, 2014; Lagdon et al., 2014; Sharhabani‐Arzy et al., 2005).

Technology‐based interventions have become acceptable, convenient, and feasible for supporting the health and well‐being of IPV survivors. These technology‐based therapies come in many forms, such as smartphone apps, phone and web‐based decision aids, chatbots or conversational agents, text message interventions, web‐based online support groups, social media, and telehealth services (Bloom et al., 2016; Debnam & Kumodzi, 2019; Klevens et al., 2012; Koziol‐McLain et al., 2016; May et al., 2003; Young et al., 2018). In addition, digital interventions are a cost‐saving, provider‐mediating, and scalable bargain, particularly where they augment in‐person modalities (like group counseling, face‐to‐face therapy, and psychosocial‐behavioral therapies) (Campbell, 2002) for assisting IPV survivors. These interventions overcome coverage gaps caused by health system problems and inequities, particularly in areas where health provider shortages exist and IPV victimization overlap with social determinants of violence (e.g., socioeconomic status, rurality, immigration status, strict gender norms, racial and ethnic disparities, and disabilities) (Akinsulure‐Smith et al., 2013; García‐Moreno et al., 2013). Moreover, these digital interventions serve a vital and timely function, as they offer social and emotional support for those who have recently experienced IPV by a partner or ex‐partner, typically at a time of high distress and crisis.

To their merit, digital interventions may be a viable source of support for historically marginalized survivors who report an elevated risk of IPV victimization, including Black and Latinx, immigrant, refugee, and asylum‐seeking women, as well as victims‐survivors with disabilities, rural women, older women, women and girls in low‐ or middle‐income regions, First Nation and Indigenous Women, and LGBTQIA+ individuals (Akinsulure‐Smith et al., 2013; Black et al., 2011; García‐Moreno et al., 2013; Koziol‐McLain et al., 2018; Malley‐Morrison & Hines, 2004; Peterson et al., 2018; Raj & Silverman, 2002).

Therefore, this systematic review and meta‐analyses aim to expand our current understanding of how effectively these digital interventions reduce mental health issues (depression, anxiety, and PTSD) and IPV victimization (physical, psychological, and sexual victimization). In addition, the significant increase in the number of clinical trials studying technology‐based therapies on IPV‐related outcomes has allowed us to quantify the effectiveness of such interventions for mental health and victimization outcomes in survivors.

2.1. Description of the condition

IPV remains a persistent public health, social justice, and human rights concern. Regardless of intimacy, relationship type, gender, or sexual orientation, the most common forms of partner violence include physical violence, sexual assault, psychological aggression, and stalking by a current or former partner or spouse (McFarlane et al., 2002; World Health Organization, 2019). About one in four US women (one in three globally) and almost one in nine US males report having experienced sexual assault, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate relationship at some point in their lives (García‐Moreno et al., 2013; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998).

2.2. Description of the intervention

Technology‐based interventions comprise eHealth (or electronic health), mHealth (or mobile health), and telehealth platforms used to deliver health care services and collect and share clinical data (World Health Organization, 2019). Over half a billion people worldwide use a health‐related smartphone app (Dorsey et al., 2017). This proliferation of health‐facing apps now empowers people to generate, monitor, and control their health data (Anderson‐Lewis et al., 2018; Dorsey et al., 2017; Klasnja & Pratt, 2012). Likewise, rapid improvements in patient technology literacy, device ownership, and device features have led to a growing reliance on technology to deliver interventions to support IPV survivors in ecologically valid ways while providing 24/7, safe, and confidential services and resources (Anderson‐Lewis et al., 2018; Glass et al., 2010, 2017; Ranney et al., 2013). More recently, technology‐based interventions have gained acceptance due to widespread disruptions in support systems for partner violence survivors during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Emezue 2020).

Clinically, several meta‐analyses show the promise of digital interventions in addressing multiple issues, ranging from problematic substance use to physical inactivity to diabetes self‐management across diverse cohorts (Anderson‐Lewis et al., 2018; Firth et al., 2017; Free et al., 2010; Khadjesari et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2011; Luk et al., 2019; Montgomery et al., 2017; Ybarra et al., 2016). Moreover, over the past three decades, digital therapies, at various levels of sophistication, have been created and adapted to support the health and well‐being of IPV survivors, making these interventions a critical layer of support for survivors.

Feasibility and acceptability studies show IPV survivors are receptive to trauma‐informed technology‐based interventions, and multiple individual studies—several of them reviewed in this study ‐ demonstrate the efficacy of these interventions (Glass et al., 2017; Koziol‐McLain et al., 2016; Littleton et al., 2016). In certain instances, technology outperforms traditional modalities. For example, a systematic review by Hussain et al. (2015) found that self‐administered computer screening outperformed face‐to‐face screening for IPV by 37% and paper and pencil screeners by 23%, leading to higher rates of IPV disclosure from technology‐optimized strategies. In addition, digital IPV interventions are purposefully designed to mitigate some shortcomings of traditional interventions, such as cost‐of‐care barriers, non‐confidentiality, poorly trained health/service providers, geographical inaccessibility, stigmas associated with seeking care (e.g., rape and sexual assault services), and socio‐geographical diversity (Constantino et al., 2015; Eden et al., 2015; Ford‐Gilboe et al., 2017; Glass et al., 2010, 2017; Koziol‐McLain et al., 2018; Littleton et al., 2016).

Few reviews have examined the effectiveness of digital therapies in reducing IPV‐related mental health disorders in survivors (Fu et al., 2020). However, early results are promising. From 22 studies, Fu et al. (2020) observed that digital psychological therapies were somewhat effective in addressing mental health outcomes compared to non‐digital controls for adults in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Hedges' g = 0.60 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.45–0.75]). El Morr and Layal (2020) also reviewed 25 studies evaluating the efficacy, acceptability, and applicability of these information and communication technologies (ICT) for addressing different IPV outcomes (e.g., awareness, screening, prevention, treatment, and mental health), finding substantial differences in study outcome measures, sample sizes, study design, intervention type, and participant characteristics.

Nonetheless, evidence of the effectiveness of digital interventions in enhancing the mental health and victimization outcomes of IPV survivors is just beginning to emerge. This is partly due to the novelty of digital interventions and our limited understanding of their short‐ and long‐term effects on different types of IPV survivors. Nevertheless, the proliferation of randomized trials pilot‐testing these interventions, the widening epidemic of partner violence, and the diversity of survivor needs provide compelling reasons to compile empirical evidence to provide a clear picture of the effectiveness of these interventions for survivors.

2.3. How the intervention might work

Digital IPV interventionists borrow liberally from social and behavioral sciences to develop and adapt IPV digital interventions. The most common theories that underlie these digital interventions include feminist theories (e.g., gender and power theory), social cognitive theory, family systems theories, theories of technology adoption (Emezue, 2020), trauma‐informed care, and harm reduction, all ingrained within a social‐ecological context (Lawson, 2012). We further discuss some of these theories in the “Summary of main results” section.

Digital IPV interventions may work in the following ways:

-

1.

offering ongoing or one‐time social and emotional support,

-

2.

increasing individualized safety planning and risk assessment of frequency, severity, and types of violence,

-

3.

providing information and psychoeducation to improve informed victim‐centered decision‐making,

-

4.

improving evidence gathering and documentation,

-

5.

reducing exposure to future IPV (triage to local and trusted services),

-

6.

improving mental and emotional health outcomes (depressive and anxiety disorders),

-

7.

addressing co‐occurring morbidities linked to IPV (e.g., substance use, housing, and employment needs), and

-

8.

triaging survivors to trusted care based on unique social and personal contexts.

In some instances, the technology itself is the intervention (i.e., “technology‐based interventions”) or is merely used to deliver evidence‐based interventions (“technology‐enhanced interventions”). Our meta‐analysis looks at all such descriptions of technology, so long as they were designed to support the health and well‐being of IPV survivors.

2.4. Why it is important to do this review

The proliferation of IPV digital intervention presents a strong rationale for gathering evidence on the intervention and treatment effects of these interventions to address critical gaps in our current understanding. Moreover, a clear understanding of the benefits (and drawbacks) of digital IPV interventions bears serious implications for intervention design, user engagement, uptake, and overall treatment effects for IPV survivors.

At the study level, we know that digital interventions are efficacious (Ford‐Gilboe et al., 2017; Glass et al., 2010, 2017). However, the extent to which they contribute to long‐term improvements in survivor outcomes remains unknown (Ford‐Gilboe et al., 2017). Few IPV digital interventions have reached effectiveness and pragmatic trials to test their effectiveness in sub‐optimal real‐world conditions. In addition, there have been few attempts to cumulate the intervention (or treatment) effects of digital interventions on survivors' mental health, even though mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety disorders, and PTSD are primary concerns for survivors (Keynejad et al., 2020; Lagdon et al., 2014; Nathanson et al., 2012).

Furthermore, funders and policymakers can use findings from this and other meta‐analytic studies to establish an omnibus effect size baseline for digital interventions targeting key IPV and mental health outcomes. The findings of this analysis could lead to changes in health policy that allow providers to be reimbursed for offering or recommending evidence‐based digital interventions. In addition, results from this meta‐analysis can be used to bolster calls for the inclusion of IPV digital therapies as additional therapeutic tools in universal screening systems in keeping with the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for routine screening of reproductive‐age women (14–46 years) (Moyer, 2013). Our findings will help evidence‐to‐decision frameworks for service providers who want to know if digital approaches are effective, reliable, and safe for supporting the emotional well‐being of survivors.

Finally, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, stay‐at‐home and social distancing mandates disrupted regular service provision for survivors. This led to digital therapies becoming even more pertinent, as epidemiology data reported surges in domestic violence during this time (Emezue, 2020). Overall, a meta‐analysis remains one of the highest levels of evidence to support practice, research, and policy guidelines.

3. OBJECTIVES

This review and meta‐analysis aim to synthesize current evidence on the effectiveness of digital interventions on mental health and victimization outcomes among survivors of partner violence.

The following research questions guided this study:

-

1.

Are digital and technology‐based interventions effective in reducing mental health issues (depression, anxiety, and PTSD) following the intervention and at later follow‐up?

-

2.

Are digital and technology‐based interventions effective in reducing IPV victimization (physical, psychological, and sexual victimization) following the intervention and at later follow‐up?

3.1. Title registration and review protocol

The Campbell Collaboration approved the title for this systematic review on 23 May 2019. The review protocol was published on January 14, 2021. The title registration and protocol are available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cl2.1132

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

Inclusion criteria

In Table 1, we show a breakdown of our eligibility criteria. Studies were eligible if they (1) used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a well‐defined treatment and control groups; (2) included outcome data to compute effect sizes for PTSD, anxiety, depression, and victimization (physical, psychological, and sexual violence); (3) were full‐text available; (4) published in English (due to the authors' language limitations); and (5) published between 2007 and 2021 (to account for the previous 15 years, during which time the popularity of digital therapies for IPV significantly rose (Anderson et al., 2019; Anderson‐Lewis et al., 2018). Studies in which IPV victimization outcomes were secondary outcomes were also included.

Table 1.

Study eligibility criteria

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Survivors of IPV or violence in relational contexts |

Children and adolescents under 18 Perpetrators |

| Intervention |

Digital interventions: Defined broadly to include any use of technology to deliver information, treatment, therapy, or psychosocial support to improve the mental health of survivors of partner violence. All types of IPV digital interventions (mHealth, eHealth, and telehealth) designed to reduce IPV and related mental health outcomes |

Non‐digital methods (e.g. paper and pencil surveys, checklists), traditional modalities (e.g. counseling, advocacy group sessions, standard shelter services, home visitation). Studies were also excluded where the extent of technology use in the study was limited to participant randomization, recruitment, screening only, follow‐up only. Studies were also excluded without a clear characterization of IPV outcomes. Pilot studies that focused on feasibility and acceptability only were excluded. |

| Comparator |

Control conditions can involve: Usual care (UC), No treatment, Intervention ‐as‐usual (IAU), Waitlist controls, Active placebo control group. |

No comparator |

| Outcomes |

Eligible digital and technology‐based interventions must address a mental health conditions |

Non‐IPV Domestic violence encompassing child abuse, peer violence, acquaintance rape, elder abuse, bullying, parental violence, and other non‐dating victimization |

| ||

| Forms of IPV victimization and any changes in IPV victimization outcomes: | ||

| ||

| Timing | No limitations were placed on studies by their duration of follow‐up. | None |

| Setting |

Any community‐based, school, online, religious, or clinical setting Global, any country. |

None |

| Study design |

Randomized control trials (RCTs), with randomization to control and intervention conditions. Quasi‐randomized control trials, where a quasi‐random method of allocation was used, (e.g., the order of recruitment), Quasi‐experimental studies (or controlled clinical trial without true randomization). |

Feasibility and acceptability only studies, without IPV outcomes Pre–posttest studies with a single group design Non‐clinical study (e.g., secondary data study, reviews, editorials) Uncontrolled clinical study Qualitative studies Prospective and retrospective observational studies |

| Publication type |

English language studies Published, peer‐reviewed full‐text articles |

Non‐English publications Non‐peer‐reviewed |

Exclusion criteria

We did not exclude studies based on intervention setting, country of study, or regionality, such as rural versus urban localities. Comparator/control groups of eligible studies could have been in the form of usual care, wait list controls, placebo, or alternative control formats. No limitations were placed on studies based on their duration of follow‐up. In addition, studies with repeated measures or before‐after outcomes (without a control group) were not included. Non‐IPV studies were excluded, where they focused on child abuse, peer violence, acquaintance rape, elder abuse, bullying, parental violence, and other non‐dating victimization. Studies were also excluded where the extent of technology use was limited to participant randomization, recruitment, screening, and referral outcome only (e.g., Klevens et al., 2012), follow‐up only. Finally, studies were excluded if they did not report changes in IPV victimization outcomes.

4.1.2. Types of participants

Participants of diverse sexual orientations, racial/ethnic backgrounds, and ages were included who were experiencing or had experienced IPV. Furthermore, because IPV victimization is gender agnostic, studies comprising survivors of both genders who have experienced partner violence were included. However, most IPV interventions targeted women of reproductive age (14‐46 years) and emphasized secondary and tertiary prevention (i.e., intervention after violence had already occurred). Almost all the included studies primarily enrolled adult (>18) female‐identifying survivors. However, because only a few studies included male victims (primarily in couple dyads), these studies were not included if female victim data could not be acquired independently.

4.1.3. Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

We considered all types of IPV digital interventions designed to reduce IPV exposure adverse mental health, and victimization outcomes. Operationally, we defined digital interventions as those deployed via mHealth, eHealth, and telehealth modalities, including personalized digital platforms (videos, smartphone apps, text messaging, chatbots, social media, and email). Digital interventions may be used for safety planning, digital consultation, referral‐to‐care, psychoeducation, and decision support, but must ultimately target mental health and victimization outcomes in each study. Interventions with digital‐only or digital plus traditional hybrid models were also included.

Control or comparator intervention

Control conditions varied across studies and included usual care (UC), intervention‐as‐usual (IAU), waitlist controls, or an active placebo control group format. Examples of control conditions included enhanced control groups, such as the control participants receiving modular IPV psychoeducation but not in a digital format, and participants receiving a smartphone app or website containing non‐IPV information (see Koziol‐McLain et al., 2018; Littleton et al., 2016), or face‐to‐face counseling (i.e., enhanced usual care) by a health care provider (Constantino et al., 2015).

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Two categories of outcomes are of interest in this meta‐analysis: (1) mental health outcomes, and (2) victimization outcomes (see Primary outcomes).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest to be quantitatively synthesized were:

-

1.

IPV‐related common mental health disorders:

-

a.

Depression, or any self‐reported or clinical base change in depressive symptoms.

-

b.

PTSD, or any self‐reported or clinical base change in PTSD symptoms.

-

c.

Anxiety, or any self‐reported or clinical base change in anxiety symptoms.

-

2.

Any changes in IPV victimization outcomes (i.e., physical aggression, sexual violence, psychological abuse).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were not meta‐analyzed here. However, commonly reported secondary outcomes in retrieved RCTs were (1) self‐efficacy (or ability to create and use a safety plan based on intra‐person, demographics, and extra‐person variables), (2) risk awareness (or objective awareness of present or future IPV risk), (3) decisional conflict (ability to navigate an abusive context, stay or leave the abusive relationship), and (4) safety planning (e.g., executing a personalized safety plan).

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

An initial set of articles were retrieved and used to create a library of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms using an online search building tool called Yale MeSH Analyzer (see Grossetta & Wang, 2018). The MeSH term analysis grid was generated to help establish indexing consistency. We combined key search terms with MeSH in two broad classifications: “digital interventions” AND “intimate partner violence” (see search strategy in Table 2). All search terms were restricted or expanded using suitable Boolean and proximity operators. Filters and limiters included “English” and “year of publication.” We used controlled vocabulary to account for variant spellings, truncations, and wildcards. Database‐specific searches were done using aggregated or simplified keywords (free‐text and subject headings; see Supporting Information: Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Search strategies in databases

| In traditional and grey databases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Intimate partner violence | ||

| Search terms | (mHealth OR mobile apps OR eHealth OR mobile applications OR interactive mobile application OR apps OR “mobile app” OR electronic interventions OR safety app OR decision aid OR mobile intervention OR smartphone OR smartphone apps OR smartphone‐based app OR smartphone‐delivered OR mobile‐delivered OR technology‐mediated OR internet‐based OR web‐based OR computer‐based OR computerized OR electronic OR technology‐based OR “use of technology” OR m‐Health OR e‐Health OR social network OR social media OR mobile phone OR mobile device OR Virtual communit* OR virtual reality OR Twitter OR Facebook OR WhatsApp OR WeChat “mobile health” OR “mobile care” OR “m Health” OR “mobile phone” OR “mobile device” OR “mobile technology” OR “mobile communication” OR “mobile telecommunication” OR “mobile app” OR “mobile application” OR “mobile tool” OR “mobile messaging” OR “mobile electronic device” OR “mobile telephone” OR “mobile phones” OR “mobile devices” OR “mobile technologies” OR “mobile communications” OR “mobile telecommunications” OR “mobile apps” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile tools” OR “mobile messages” OR “mobile electronic devices” OR “mobile telephones” OR “mobile intervention” OR “mobile interventions” OR “mobile delivered” OR “mobile delivery OR information, communication technology OR ICT OR email) | AND | (“Intimate Partner Violence”[Mesh] OR “partner violence” OR “partner abuse” OR “dating violence” OR “dating abuse” OR dating violence OR partner abuse OR adolescent dating violence OR OR stalking OR assault OR coercion OR “digital abuse” OR rape OR battered women OR “domestic abuse” OR “wife abuse” OR “Spouse Abuse”[Mesh] OR “Domestic Violence”[Mesh:noexp] OR intimate partner violence[tiab] OR domestic violence[tiab] OR dating violence[tiab] OR partner violence[tiab] OR domestic abuse[tiab] OR partner abuse[tiab] OR (Abuse[tiab] OR abusive[tiab] OR abused[tiab] OR battered[tiab] OR battering[tiab] OR violent[tiab] OR violence[tiab] OR assaultive[tiab]) |

4.2.1. Electronic searches

We searched the following databases with the support of a health science research librarian:

-

1.

Traditional broad‐spectrum databases:

-

a.

PubMed Central (PMC)

-

b.

Web of Science

-

c.

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus,

-

d.

PsychINFO.

-

a.

-

2.

Clinical trial registry (i.e., ClinicalTrials.gov).

-

3.

Grey literature search on Google Scholar for conference abstracts, as well as organizational and government repositories.

-

4.

Reference searching of all included studies for further relevant studies.

All study searches were conducted from March to April 2019 (14 studies found) and February to March 2021 (two studies added). During peer review, a final RCT was recommended by the reviewers for addition, bringing the total number of included RCTs to 17.

4.2.2. Searching other resources

Topic‐related organizational websites (e.g., www.VAWnet.org) were searched to reduce possible publication bias by avoiding unpublished studies, as well as purposive searches of key authors predominantly involved in mHealth‐linked IPV interventions and their concurrent publications on this topic.

-

1.

In addition, searches were conducted by target‐searching recent reviews of IPV interventions for digital interventions.

-

2.

Lastly, author known to research and publish on tech‐based IPV interventions were searched by name for possible inclusion.

4.3. Data collection and analysis

4.3.1. Description of methods used in primary research

All included RCTs had to have a well‐defined control group. All studies included IPV as a principal outcome or secondary outcome. However, some studies addressed IPV in relation to other conditions, such as anger management, relationship distress (Braithwaite & Fincham, 2009, 2011, 2014), HIV drug adherence, substance use (Gilbert et al., 2016), trauma distress, as well as somatic co‐morbidities. Typically, studies testing a technology‐based intervention for IPV added a qualitative component to explore survivor's lived experiences and to understand the feasibility and acceptability of IPV digital interventions (e.g., Alhusen et al., 2015; Debnam & Kumodzi, 2019; Ford‐Gilboe et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2013; Tarzia et al., 2017). For example, Bacchus et al., (2016) used nested interpretive methods to study perinatal home visitors' and women's experiences with IPV screening and receiving intervention in the form of mHealth technology (i.e., a computer or tablet) or a home visitor‐led method. Qualitative findings indicate that IPV survivors consider digital interventions an acceptable response and support tool (Hegarty et al., 2019).

4.3.2. Selection of studies

Two reviewers (including an experienced dating violence researcher) and a health science research librarian independently screened for titles and abstracts from a random selection of yielded articles. An inter‐rater agreement of 80% (range of 0–1) (i.e., κ statistics, Landis & Koch, 1977) was established for ongoing study selection and risk of bias assessments.

4.3.3. Data extraction and management

Two team members extracted data from each article into a standardized worksheet that included information on study details, as well as primary and secondary outcomes data (e.g., means, SD, CIs, odds ratio [OR]). We also extracted study descriptors (e.g., assignment and blinding protocol, digital intervention used, study duration), control or comparison group descriptors, and fidelity outcomes (attrition and follow‐up data). This information has been itemized in the Summary of findings Table 3. Authors CE and JC reached consensus on what studies should be included based on preset criteria. Although we first ran our analyses using Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis (CMA; Borenstein et al., 2011), we used Cochrane's RevMan to run a final analysis, finding convergence between both software.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in meta‐analysis

| Study author (year) | Country | RCT Design | Underlying theory and mechanism of action | Participants and study setting | Description of intervention and control conditions | Intervention delivery mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford‐Gilboe et al. (2020) | Canada; 3 provinces (British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick) | Two‐arm double‐blind randomized controlled trial RCT. 1:1 allocation | Principles of trauma‐ and violence‐informed care (TVIC) | 462 Canadian adult women |

Intervention: Tailored, interactive online safety and health intervention (iCAN Plan 4 Safety). Control: A static, non‐tailored version of this tool. |

Website/Online intervention, reminder messages |

| Decker et al. (2020) | Nairobi, Kenya (informal settlements) | Randomized, controlled, participant‐blinded superiority trial (1:1 ratio) | Social cognitive theory, empowerment and trauma‐informed care, emphasizing safety and empowerment through agency in decision‐making and healing. | Women at risk of and experiencing IPV in Nairobi, Kenya. 352 were consented and enrolled at baseline (86.48%; n = 175 control, n = 177 intervention |

Intervention: The myPlan Kenya app sections included the following: the Healthy Relationships, my Relationship, Red Flags, and My Safety section using the validated Danger Assessment scale. Other sections were the My Priorities section, My Plan section provided the tailored safety plan based on data supplied by the user in the previous sections. Control: Standard “usual care” set of referrals to IPV‐related legal, health, safety, counseling and financial resources—delivered in an app‐like webpage with research staff assistance. |

App |

| Glass et al. (2017) | United States: Arizona, Maryland, Missouri, and Oregon |

Multistate, community‐based longitudinal RCT with one‐to‐one allocation ratio and blocked randomization. Computerized blocked randomization provided intrastate stratification and for participants with children (aged ˂18 years) at home, ensuring each state's groups remained relatively balanced. The randomization sequence (concealed from research assistants [RAs]) |

Dutton's empowerment model and resiliency models. | Currently abused Spanish‐ or English‐speaking women (N = 720). |

Intervention: Tailored, Internet‐based safety decision aid (included priority‐setting activities, risk assessment, and tailored feedback and safety plans). Control: A control website offered typical safety information available online |

Website |

| Hegarty et al. (2019) | Australia |

Two‐group pragmatic randomized controlled trial, randomly assigned (1:1) by computer to receive either the intervention or control website. As the initial portion of the website containing the baseline questions was identical for both groups, there was no way for women to tell which group they had been allocated to. Women were masked to treatment allocation, although it is possible that some may have guessed which website they were receiving. All the research team was masked to participant allocation until after analysis of the 12‐month data. |

Psychosocial Readiness Model, and Contemplation Ladder | Women aged 16–50 years currently residing in Australia. 422 eligible participants were randomly allocated to the intervention group (227 patients) or control group (195 patients) |

Intervention: An online healthy relationship tool/website and safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence (I‐DECIDE): RCT. On the intervention website, participants were presented with three modules addressing healthy relationships, safety, and priorities. Control: Static intimate partner violence information website |

Website |

| Glass et al. (2021) | United States: Oregon and Maryland | An automated algorithm randomly assigned enrolled participants to the intervention or control group. The randomization was stratified on the state of residence, having children (child/no child in the home), and type of college/university. | Dutton's empowerment model | Three hundred forty‐six women (175 intervention, 171 control) from 41 colleges/universities in Oregon and Maryland. English‐speaking women (including cisgender and transgender women), |

Intervention: The myPlan is an interactive decision aid and safety planning intervention that is free and accessible via a mobile app and website (myPlanApp.org), appropriate technology for college students (Glass et al., 2015, 2017). myPlan was created drawing upon foundational work in empowerment (Dutton, 1992), a previous trial of an internet safety decision aid for women of all ages (Glass et al., 2017), and the literature on safety planning (Campbell & Glass, 2009; Campbell et al., 2001; Davies & Lyon, 1998; Hardesty & Campbell, 2004; McFarlane et al., 2002, 2004). Control: A usual safety planning website guided by basic emergency safety planning information provided to students on‐campus and found through IPV websites targeting young women in unsafe relationships. |

App/Website |

| Koziol‐McLain et al. (2018) | New Zealand |

Web‐based two‐arm parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT): password‐protected intervention website (safety prioritized, danger assessment, and action plan modules) or control website (standard, non‐individualized). Computer‐generated randomization was based on a minimization scheme with stratification by the severity of violence and children |

Dutton's empowerment model | New Zealand women (n = 412; 27% Māori) who had experienced IPV in the past 6 months |

Intervention: Interactive Web‐based safety decision aid (iSafe)—password‐protected intervention website (safety priority setting, danger assessment, and tailored action plan components) Control: website (standard, non‐individualized information). Women randomly assigned to the control group were able to access a standardized list of resources and emergency safety plans throughout the 1‐year postbaseline follow‐up via a password‐protected trial website. |

Web‐based safety decision aid |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2009) | Large US public university |

RCT, ePREP (n = 38) versus computer‐based placebo intervention (n = 39). A computer‐generated randomization list was used to assign participants to either the ePREP (n = 38) or the placebo/control intervention (n = 39). |

Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP, Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001) centering on communication skills and relational theory. | 77 college students in romantic relationships of 4 months or longer. Only one partner of a dyadic partnership in intervention. 71% female. White, 76%; African American, 10%; Hispanic, 7% and “Other,” 7%. Over 9% reported living together and 91% living apart. Ages range (from 18 to 25), average age = 19.4 at the beginning of the study. |

Intervention: One hour‐long ePREP. Based on the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement program (PREP, Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001), The focus of the intervention is skills training in effective communication techniques and problem‐solving skills. It also teaches individuals how to enhance positive aspects of romantic relationships. Sections of the ePREP Intervention ; Improving Your Relationship; Filters; Communication; Issues and Events; Problem solving; Fun, Friendship and The Foundation of a Good Relationship; Ground Rules. Control: Placebo presentation and material that provided inert descriptive information about anxiety, depression, and relationship distress such as definitions, prevalence rates, and available forms of treatment. |

Computer/Email |

| Stevens et al. (2015) | United States | RCT randomly assigned to an experimental condition, Assignment to condition was based on a computer‐generated random number table. RA blinded to study condition. One hundred twenty‐nine participants were randomly assigned to the intervention condition (TSS), and 124 participants were randomly assigned to the control condition (EUC). | Motivational Interviewing (MI) |

Three hundred women (ages 18 years and above), reporting past‐year IPV visiting a pediatric emergency department. The sample was roughly half African American and half Caucasian American. Considering that 80% of the children had Medicaid as their insurer |

Intervention: Telephone support services (TSS)—assessment phase, implementation phase, monitoring phase, secondary implementation phase, and termination phase. Control: Enhanced usual care (EUC)— Includingn phone calls about the child's recent visit to the ED and following up on any non‐IPV injury concerns endorsed by the woman. However, no discussions about IPV or community resources. |

Telephone |

| Tiwari et al. (2010) | Hong Kong, China |

Assessor‐blinded randomized controlled trial (RCT). Participants were randomized (1:1) to the intervention or control group according to a list of random permutations prepared by computer‐generated blocked randomization performed by a research staff member who had not been involved in participant recruitment. The block size was kept secure by the randomizer, and the order of allocation was centrally controlled to avoid any bias in selection. The allocation sequence was concealed in opaque envelopes. At the time of randomization, the research assistant who had successfully recruited a participant called the site investigator, who then opened the envelope containing the group assignment. To ensure random assignment, no detail was provided to the site investigator about the identity of the participant. Assessors were not involved in the design of the study, did not know the study hypotheses, and were blinded to group assignment. |

Dutton's empowerment model and Cohen's Social Support Theory; and telephone social support | Telephone intervention to improve the mental health of community‐dwelling women abused by their intimate partners: a randomized controlled trial 18 years or older with a history of IPV. were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 100) or control (n = 100) group |

Intervention: 12‐week advocacy intervention, Telephone intervention. The intervention used for this study is classified as a less intensive advocacy intervention (an intervention of not more than 12 total hours). The empowerment component + social support component. Empowerment support: 30 min to deliver, was provided once in a oneone‐to‐one‐to‐one interview conducted in a private room (in the center or one of the outreach sites) by a designated research assistant at the beginning of the 12‐week intervention. At the end of the interview, each of the women was given an empowerment pamphlet to reinforce the information provided. Social support: 12 scheduled weekly telephone calls (initiated by the designated research assistant) and 24‐h access to a hotline for the study participants for additional social support. Control: Community services referral. |

Phone Calls |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2011) | Large US public university | RCT, ePREP (n = 40) versus computer‐based placebo intervention (n = 37). Using computer‐generated randomization list | Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP, Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001) centering on communication skills and relational theory. |

77 couples (152 individuals). The average age was 19.92 years. Average relationship length (between 1 and 2 years). 20% reported current cohabitation. Overall, 77% White (non‐Hispanic), 10% Latino, 8% Black, 3% “Mixed Race” and 2% Asian. Only one of a dyadic partnership in intervention. Only those who had been in a committed romantic relationship for 6 months or longer were invited to participate. average relationship length was between 1 and 2 years and 20% of participants reported that they were currently cohabiting. |

Intervention: Computer‐based preventive intervention (ePREP) versus active placebo control group. ePREP condition taught empirically based methods for improving romantic relationships. Control: inert information about anxiety, depression, and relationships such as definitions, prevalence rates, and available forms of treatment—detailed in Braithwaite and Fincham (2009) |

Computer/Email APIM was used to test the impact of ePREP relative to the placebo intervention (see Figure 1). The omnibus test of distinguishability (I‐SAT) was used to test for empirical distinguishability (Olsen & Kenny, 2006) and revealed that all of the variables examined were distinguishable by gender with the exception of alternatives monitoring, constructive communication, and self‐reported physical assault. |

| Littleton et al. (2016) | US, students at one of four universities and community colleges | RCT, interactive program (n = 46) or a psycho‐educational self‐help website (n = 41) | Cognitive‐behavioral therapy | Eighty‐seven college women with rape‐related PTSD were randomized to complete the interactive program (n = 46) or a psycho‐educational self‐help website (n = 41). |

Intervention: From Survivor to Thriver program, an interactive, online therapist‐facilitated cognitive‐behavioral program for rape‐related PTSD. The From Survivor to Thriver Program consisted of nine program modules. The program was designed to be completed sequentially, with participants completing one module at a time. Control: Psycho‐educational self‐help website (n = 41). with content of the first three modules of the interactive program including the symptoms of PTSD, information about relaxation and grounding, and information about healthy coping strategies. No multimedia content (videos from the program developers, audio recorded relaxation exercises) or any interactive exercises. |

Website |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2007) | Large public university in the US Northeast | Three‐arm RCT. Participants were randomly assigned to take part in one of the three interventions. | Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP, Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001) centering on communication skills and relational theory. |

Ninety–one young adult in dating relationships. Women made up 59% of the sample. Ethnic background was distributed as follows, Caucasian, 60.9%; Asian, 18.7%; African American, 5.5%; and “Other”, 14.3%. |

Intervention: Computer‐based relationship‐focused preventive intervention (ePREP) relative to depression and anxiety‐focused computer–based preventive intervention. individually administered computer‐based presentations (comprising written text and pictures, no audio or video material was used), the pace of which was controlled by the participant. For the interventions, examples of how to employ certain skills were provided in vignettes that described couples utilizing the skill in question. In each case, the intervention included a quiz following the presentation of each section of material and this quiz assessed participants' mastery of the information presented. The interventions were intentionally balanced to contain approximately the same amount of content and therefore took approximately the same amount of time to administer. CBASP Participants in the depression and anxiety‐focused intervention condition received training in an empirically validated method for reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. This intervention, based on the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) developed by McCullough (2000), teaches techniques for analyzing and changing patterns of maladaptive thinking and behavior. Control: Presentation and worked through material with information about anxiety, depression, and relationship information such as definitions, prevalence rates, and available forms of treatment. |

Computer/Email |

| Doss et al. (2016) | United States, national sample | Using a random number generator, 151 couples were randomized into the web‐based intervention condition and 149 couples were randomized into the waitlist control condition. | Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT; Christensen et al., 2010) |

300 heterosexual couples (N = 600 participants) participated; couples were generally representative of the US in terms of race, ethnicity, and education. Individuals were primarily White, non‐Hispanicnon‐Hispanic (67.2%), African American (17.2%), or White, Hispanic (10.2%), with smaller numbers of Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3%), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.7%), and Biracial/Other (1.4%) participants. |

Intervention: In the program, couples' complete online activities and have four, 15‐min calls with project staff. Control: TwoTwo‐month‐month wait‐list control group. |

Website |

| Constantino et al. (2015) | United States, Pittsburg, several sites |

RCT, three‐arm: Online (ONL), Face‐to‐Face (FTF), and Waitlist Control (WC). A sequential, transformative mixed‐methods design was used. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three study groups by permuted block randomization. The designation of numbers for intervention conditions (i.e., 1 = ONL, 2 = FTF, and 3 = WLC) were concealed from data collectors and the statistician |

Advocacy lens, | 32 adult female participants who were 45.2% Asian, 32.3% White, and 22.5% Black |

Intervention: HELPP (Health, Education on Safety, and Legal Support and Resources in IPV Participant Preferred) intervention among IPV survivors. Online (ONL) HELPP. The ONL intervention consisted of six modules delivered by e‐mail once a week for 6 weeks. Face‐to‐Face (FTF) HELPP. The FTF intervention consisted of six modules and was given to each participant once a week for 6 weeks. Six HELPP modules, 1 week at a time (Constantino et al., 2014) to each participant (i.e., by e‐mail for ONL and in‐person for FTF). |

Computer/Email |

| Zlotnick et al. (2019) | United States | Two‐group, randomized controlled trial. | Motivational Interviewing (MI), Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) |

53 currently pregnant or within 6‐months postpartum women seeking mental health treatment. Of the 53 women enrolled in the randomized trial, 17 women (32%) identified themselves as Hispanic/Latina. Six (11%) identified themselves as Black or African American, 27 (51%) as White, 5 (9%) as Bi‐racial or Multi‐ethnic, and 15 (28%) as Other. |

Intervention: A brief, motivational computer‐based intervention, SURE (Strength for U in Relationship Empowerment), for perinatal women with IPV seeking mental health treatment. SURE is a computerized intervention (30–40 min) delivered on a small tablet computer and was adapted and delivered using an intervention software platform, Computerized Intervention Authoring Software (CIAS, Interva, Inc.; Ondersma et al., 2005). Control: Participants interacted with the computer software and were guided by the same narrator. Control condition included watching brief segments of popular television shows and following up with questions for ratings of their preference. No follow‐up booster session for the control condition. Participants in both conditions received information on IPV and community resources for IPV. |

Small tablet computer |

| Gilbert et al. (2016) | United States, New York City |

RCT, A study investigator randomly assigned groups of 4 to 9 women to 1 of 3 study conditions; a computer‐generated randomization algorithm was designed to balance the number of women per study arm via an adaptive, biased‐coin procedure. Investigators were masked to treatment assignment until the final 12‐month follow‐up assessment was completed in April 2013. |

The intervention was informed by social cognitive learning theory, which focuses on observation, modeling, and skill rehearsal through role‐play and feedback from group members. Empowerment theory also guided a strengths‐based approach of WORTH to build collective efficacy of women to negotiate safe relationships and counter the stigma that they face as women in community corrections |

191 substance‐using women in probation and community court. A total of 103 participants were assigned to Computerized WORTH, 101 to Traditional WORTH, and 102 to Wellness Promotion. Over (68%) identified as Black or African American, and 47 (15.4%) identified as Latina. TwoTwo‐thirds‐thirds (66.0%) were single and never married. 25 women (8.2%) were employed, and 278 (90.8%) had ever been in prison or jail. Of the women, 194 (63.4%) reported using illicit drugs in the past 90 days. About one quarter (n = 81; 26.5%) tested positive for an STI, and 43 (14.1%) tested positive for HIV. |

Intervention: Computerized, group‐based HIV and IPV intervention among substance‐using women mandated to community corrections in the Women on the Road to Health (WORTH) intervention. Three study arms: (1) 4 group sessions intervention with computerized self‐paced IPV prevention modules (Computerized Women on the Road to Health [WORTH]), (2) traditional HIV and IPV prevention group covering the same content as Computerized WORTH without computers (Traditional WORTH), and (3) a Wellness Promotion control group. Control: The Wellness Promotion control arm comprised of 4 weekly 90‐min group sessions on maintaining a healthy diet, increasing fitness in daily routines, addressing tobacco use, learning stress‐reduction methods including guided meditation, and creating and achieving personal health goals. Wellness Promotion did not address IPV prevention. |

Computer |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2014) | United States, Tallahassee, Florida | RCT, ePREP (n = 26 couples) versus computer‐based placebo intervention (n = 25 couples). | Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP, Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001) centering on communication skills and relational theory. | A community sample of 52 married couples (21% Black, 3% Asian, 65% White, 7% Latino, 4% Mixed/biracial) who had been married, on average, 4.3 years |

Intervention: Computer‐based (text and video) preventive intervention (ePREP) versus active placebo control group. ePREP adapted and computerized version of the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP, Markman et al., 2010). Intervention and control presentation lasted approximately 1 h, followed by weekly homework assignments for the next 6 weeks (1 h per session, completed as a couple). Posttreatment assessment at 96% retention rate. The computer‐presentation portions of both interventions were self‐paced and included both text and video. Control: Participants viewed a presentation that taught inert information that was designed to seem like part of an intervention |

Computer |

| Study author (year) | Analysis and timing of posttreatment assessment | Outcome measures | Study duration and follow‐up | Overall retention and attrition | Total mean age (SD) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford‐Gilboe et al. (2020) | Intent to treat protocols; Generalized Estimating Equations were used to test for differences in outcomes by study arm. Differential effects of the tailored intervention for 4 strata of women were examined using effect sizes. Exit survey process evaluation data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, t‐tests, and conventional content analysis. | Primary (depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms) and secondary (helpfulness of safety actions, confidence in safety planning, mastery, social support, experiences of coercive control, and decisional conflict) | Baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months later via online surveys |

Retention was 89.6, 87.0, and 87.0% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively for the tailored group. In the non‐tailored group, retention was 91.8, 91.3, and 90.5% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. Attrition across all time points was small and largely due to losing contact with women. |

Mean age = 34.61 (10.7) | Women in both tailored and non‐tailored groups improved over time on primary outcomes of depression (p < 0.001) and PTSD (p < 0.001) and on all secondary outcomes. Changes over time did not differ by study arm. Women in both groups reported high levels of benefit, safety, and accessibility of the online interventions, with low risk of harm, although those completing the tailored intervention were more positive about fit and helpfulness. Importantly, the tailored intervention had greater positive effects for 4 groups of women, those: with children under 18 living at home; reporting more severe violence; living in medium‐sized and large urban centers, and not living with a partner. |

| Decker et al. (2020) | Intent‐to‐treat, differences‐in‐differences approach used random effects logistic and linear regression models | Primary outcomes were safety preparedness, safety behavior and IPV; secondary outcomes include resilience, mental health, service utilization, and self‐blame. | Baseline, 3‐month follow‐up | 88% retention | Mean age of 26.52 years old (4.70) | At 3 months, intervention participants reported increased helpfulness of safety strategies used relative to control participants (p = 0.004); IPV was reduced in both groups. Among women reporting the highest level of IPV severity, intervention participants had a significant increase in resilience (p < 0.01) compared with controls, and significantly decreased risk for lethal violence (p < 0.01). |

| Glass et al. (2017) |

Intent‐to‐treat approach including generalized estimating equations to test for differences in change over time between groups. Analyses used a Gaussian distribution with an identity link function, with an exchangeable working correlation matrix. Time had three levels (baseline, 6 months, 12 months) for IPV severity, and mental health outcomes had four levels (baseline pre‐test, baseline post‐test, 6 months, and 12 months) for decisional conflict and two levels (baseline, and 6þ12 months) for safety behaviors. In addition, χ 2 analyses tested group differences in the number of women who left the abuser by 12 months. For all women, independent sample t‐tests tested differences in safety behaviors and IPV between women who left (n = 390) and stayed (n = 283). |

Decisional conflict, safety behaviors, and repeat IPV; secondary: depression and PTSD. | Baseline, 6 months, and 12 months | Missing data for intervention and control groups (accounting for attrition and incomplete responses) was 9.0% and 5.3% (6 months) and 8.5% and 9.2% (12 months), respectively. | Mean age = 33.41 (10.64) | At 12 months, no significant group differences in IPV, depression, or PTSD. Intervention women reported significantly less decisional conflict after one use (β = −2.68, p = 0.042) and greater increase in safety behaviors they rated as helpful from baseline to 12 months (12% vs. 9%, p = 0.033) and were more likely to have left the abuser (63% vs. 53%, p = 0.008). Women who left had higher baseline risk (14.9 vs. 13.1, p = 0.003) found more of the safety behaviors they tried helpful (61.1% vs. 47.5%, p < 0.001), and had greater reductions in psychological IPV (11.69 vs. 7.5, p = 0.001) and sexual IPV (2.41 vs. 1.25, p = 0.001) than women who stayed. |

| Hegarty et al. (2019) | Both the main and imputed data analyses were done according to intention‐to‐treat principles. | Self‐efficacy, depression, fear of partner, and number of helpful behaviors for safety and wellbeing, and cost‐effectiveness | Baseline, posttest, 6 months, 12 months. | 179 (79%) participants in the intervention group and 156 (80%) participants in the control group completed a 12‐month follow‐up. | Mean age = 33.7 years (8.48) | Mean self‐efficacy at 6 months and 12 months was lower for participants in the intervention group than for participants in the control group, although this did not meet the prespecified mean difference (6 months: 27.5 [SD: 5.1] vs. 28.1 [4.4], imputed mean difference 1.3 [95% CI: 0.3 to 2.3]; 12 months: 27·8 [SD: 5.4] vs. 29·0 [5.0], imputed mean difference 1.6 [95% CI: 0.5 to 2.7]). We found no difference between groups in depressive symptoms at 6 months or 12 months (6 months: 22.5 [SD: 17.1] vs. 24.2 [17.2], imputed mean difference –0.3 [95% CI: –3.5 to 3.0]; 12 months: 21.9 [SD: 19.3] vs. 21·5 [19.3], imputed mean difference –1.9 [95% CI: –5.6 to 1.7]). Qualitative findings indicated that participants found the intervention supportive and a motivation for action. |

| Glass et al. (2021) | Intention to treat analysis. | Four measure of intimate partner violence (IPV; Composite Abuse Scale [CAS], TBI‐related IPV, digital abuse, reproductive coercion [RC]) and depression. Safety behavior, decisional conflict, past‐week depression and suicide risk, substance misuse, and preparation for decision‐making | Baseline, 6 and 12 months | Six‐month retention was 98.3% for both the intervention (N = 174) and control (N = 173) groups. Twelve‐month retention was 98.9% for the intervention group (N = 175) and 96.6% (N = 171) for the control group. | Mean age in CTRL = 20.61 (2.12) Mean age in INT = 21.23 (2.56) | Reduction in RC and improvement in suicide risk were significantly greater in the myPlan group relative to controls (p = 0.019 and p = 0.46, respectively). Increases in the percent of safety behaviors tried that were helpful significantly reduced CAS scores, indicating a reduction in IPV over time in the myPlan group compared to controls (p = 0.006). Findings support the feasibility and importance of technology‐based IPV safety planning for college women. myPlan achieved a number of its objectives related to safety planning and decision‐making, the use of helpful safety behaviors, mental health, and reductions in some forms of IPV. |

| Koziol‐McLain et al. (2018) | Analyses were by intention to treat. | Primary endpoints were self‐reported mental health (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale‐Revised, CESD‐R) and IPV exposure (Severity of Violence Against Women Scale, SVAWS) at 12‐month follow‐up. | baseline, then 3, 6, and 12 months | Retention at 12 months was 87% | Median age 29.0 (16–59) | The adjusted estimated intervention effect for SVAWS was −12.44 (95% CI: −23.35 to −1.54) for Māori and 0.76 (95% CI: −5.57 to 7.09) for non‐Māori. The adjusted intervention effect for CESD‐R was −7.75 (95% CI: −15.57 to 0.07) for Māori and 1.36 (−3.16 to 5.88) for non‐Māori. No study‐related adverse events were reported. Conclusions: The interactive, individualized Web‐based iSafe decision aid was effective in reducing IPV exposure limited to indigenous Māori women. The discovery of a treatment effect in a population group that experiences significant health disparities is a welcome, important finding. |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2009) | Per protocol, completers‐only | Symptoms of depression and anxiety, IPV, communication patterns, and relationship satisfaction. | Baseline, 8 weeks, 10 months (44 weeks). | Mean age of 19.4 years. | At 10‐month follow‐up, participants in the ePREP condition experienced improved mental health and relationship‐relevant outcomes for almost all outcome measures. Participants seemed to get worse before they get better. Follow‐up: baseline, 8 weeks post‐baseline, and 10 months (44 weeks) post‐baseline. Positive effect of ePREP on IPV was not significantly weakened if partner terminated relationship and began new one | |

| Stevens et al. (2015) | Per protocol, completers‐only | IPV victimization, feelings of chronic vulnerability to the perpetrator, depressive symptoms, and PTSD | Baseline, 3, 6 months. | There was a 76% retention rate for the intervention group from baseline to 3 months (n = 98), and a 77% retention rate for the control group from baseline to 3 months (n = 95). There was a 70% retention rate for the intervention group at 6 months (n = 90), and a 72% retention rate for the control group at 6 months (n = 93). | Mean age in INT; 28.8 (8.3), Mean age in CTRL: 29.5 (8.5). | TSS and EUC groups did not differ on any outcome variable, |

| Tiwari et al. (2010) | There were no missing values or dropouts, and the analysis was consistent with the intention‐to‐treat principle. | Change in depressive symptoms (between baseline and 9 months). Secondary outcomes: changes in IPV, health‐related quality of life, and perceived social support (between baseline and 9 months). The usefulness of the intervention was evaluated at 9 months. | baseline and the 3‐ and 9‐month (i.e., 6 months postintervention) follow‐up | No subjects were lost to follow up. | Mean age in INT 38.18 ± 7.61. Mean age in CTRL 37.99 ± 6.79 | An advocacy intervention showed Intervention effects at 3 and 9 months were not significantly different (p = 0.86). The intervention significantly reduced depressive symptoms by 2.66 (95% CI, 0.26 to 5.06; p = 0.03) versus the control, less than the 5‐unit minimal clinically important difference and psychological aggression as well as improving perceived social support and safety promoting behavior for at least 6 months following the intervention. Although only usual community services were provided to the women in the control group, there was an improvement in their depression. It is probable that just abuse screening by itself may have a beneficial effect for abused women.2 There is inconsistent evidence as to whether advocacy intervention improves social support in the short term for abused women who have actively sought help. |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2011) | intent to treat analysis all participants were included in the analyses regardless of whether they completed the 6 weeks of the intervention and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to impute missing value. | Commitment attitudes, patterns of communication, prior 6 weeks psychological aggression and physical assault, relationship satisfaction and latent variables, depression latent variables, anxiety latent variable. | Baseline and 6‐weeks FU | INT: ~88% retained, CTRL: ~92% retained | Mean age = 19.92 years (1.58) | Compared to placebo intervention, ePREP participants demonstrated improved mental health and relationship functioning at a 6‐week follow‐up. Using the actor‐partner interdependence model, we found that, compared to those who received a placebo intervention, ePREP participants demonstrated better mental health and relationship functioning at a 6‐week follow‐up. Those who engaged more fully in the intervention and mastered the communication techniques generally experienced superior outcomes. Implications of and recommendations for computer‐based dissemination are discussed. |

| Littleton et al. (2016) | Intent‐to‐Treat (ITT) model. | Rape‐related PTSD symptoms, working alliance with their therapist | Baseline, 3 months follow‐up | Among the 38 participants who initiated the interactive program, 11 (28.9%) completed at least part of phase one (modules 1–3) of the program, 13 (34.2%) completed at least part of phase 2 (modules 4–5), 11 (28.9%) completed at least part of phase 3 (modules 6–9), and two (5.3%) did not complete any program modules. Six participants (15.8%) completed the entire program. | Mean age = 22 years old (range 18–42 years) | Both programs led to large reductions in interview‐assessed PTSD at post‐treatment (interactive d = 2.22, psycho‐educational d = 1.10), which were maintained at 3‐month follow‐up. Both also led to medium‐ to large‐sized reductions in self‐reported depressive and general anxiety symptoms. Follow‐up analyses supported that the therapist‐facilitated interactive program led to superior outcomes among those with higher pre‐treatment PTSD whereas the psycho‐educational self‐help website led to superior outcomes for individuals with lower pre‐treatment PTSD. Future research should examine the efficacy and effectiveness of online interventions for rape‐related PTSD including whether treatment intensity matching could be utilized to maximize outcomes and therapist resource efficiency |

| Braithwaite and Fincham (2007) | NA | Depression, anxiety, IPV (CTS–Negotiation, CTS–Psychological, CTS–Physical), quality of their relationship, Constructive Communication, Trust, Global Relationship Quality | Baseline, and at an 8‐week follow up | NA | Participants in the ePREP and CBASP interventions experienced significantly reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety and significant improvements in relationship relevant variables relative to controls. The outcomes from the two treatment conditions did not significantly differ from one another. These findings suggest that computer–based preventive interventions may be a viable and efficacious means for preventing depression, anxiety, and relationship distress. | |

| Doss et al. (2016) | Intention to Treat |

Nine primary outcome measures (assessing four relationships and five individual functioning constructs). Relationship outcomes : relationship satisfaction, Positive Relationship, and Negative Relationship Quality, Relationship Confidence. Individual outcomes : Depression, Anxiety, Perceived Health, Work Functioning, Quality of Life |

Baseline, 2, 5, 7, 8 weeks. | Of the 151 couples randomly assigned to complete the intervention, 129 couples (86%) completed the entire program. An additional eight couples (5%) completed the program through the “Understand” phase, the point where we hypothesized couples would receive a therapeutic dose of the intervention even if they did not complete the entire program. | Mean age = 36.11 (9.58) | Compared to the waitlist group, intervention couples reported significant improvements in relationship satisfaction (Cohen's d = 0.69), relationship confidence (d = 0.47), and negative relationship quality (d = 0.57). Additionally, couples reported significant improvements in multiple domains of individual functioning, especially when individuals began the program with difficulties in that domain: depressive (d = 0.71) and anxious symptoms (d = 0.94), perceived health (d = 0.51), work functioning (d = 0.57), and quality of life (d = 0.44). |

| Constantino et al. (2015) |

No ITT, completers‐only. Patient demographics and outcome measures were reported using (1) means and standard deviations for continuous variables and (2) frequency distribution for categorical variables. OneOne‐way‐way ANOVA and χ 2‐tests were used to compare the differences of demographics among the three groups. The differences between baseline and post‐intervention within each group were compared using a paired Student's t‐test. The change from baseline to post‐intervention was also computed and compared between the three groups using oneone‐way‐way ANOVA with post hoc multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute), and significance was set at p < 0.05. |

Outcome measures were anxiety, depression, anger, personal, and social support | Baseline and 6 weeks post‐intervention | Almost 100% retention after randomization | Mean age: 40.0 years |