Abstract

The spike protein (S) of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), in particular, the C-terminal domain of the S1 subunit (S1-CTD), which contains the conserved CO26K-equivalent (COE) region (aa 499–638), which is recognized by neutralizing antibodies, exhibits a high degree of genetic and antigenic diversity. We analyzed 61 PEDV S1-CTD sequences (630 nt), including 26 from samples collected from seven provinces in northern Vietnam from 2018 to 2019 and 35 other sequences, representing the G1a and 1b, G2a and 2b, and recombinant (G1c) genotypes and vaccines. The majority (73.1%) of the strains (19/26) belonged to subgroup G2b. In a phylogenetic analysis, seven strains were clustered into an independent, distinct subgenogroup named dsG with strong nodal support (98%), separate from both G1a and G1b as well as G2a, 2b, and G1c. Sequence analysis revealed distinct changes (513T>S, 520G>D, 527V>(L/M), 591L>F, 669A>(S/P), and 691V>I) in the COE and S1D regions that were only identified in these Vietnamese strains. This cluster is a new antigenic variant subgroup, and further studies are required to investigate the antigenicity of these variants. The results of this study demonstrated the continuous evolution in the S1 region of Vietnamese PEDV strains, which emphasizes the need for frequent updates of vaccines for effective protection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00705-022-05580-x.

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) was first discovered in Europe, and the first strain, CV777, was isolated in 1976 from pigs during an outbreak in Belgium [1]. PEDV continued to spread in European countries in the 1970s and 1980s and afterwards, but the number of recorded outbreaks in Europe has gradually decreased [2]. In Asia, during this period, PEDV also appeared in Japan [3], China [4], and Thailand [5], causing severe economic losses. In the spring of 2013, PEDV began to cause disease in the USA, leading to the deaths of more than 8 million newborn piglets in just one year of the outbreak [6]. The strain responsible, referred to as the "US-like strain", soon spread to Canada, Mexico, and Colombia [7]. Subsequently, US-like PEDV strains were reported in South Korea in late 2013 [8], in Germany in May 2014 [9], in Taiwan in late 2013 [10], and in Japan in October 2013 and between 2013 and 2014 [11]. They soon became widespread, causing an epidemic wave in many Asian countries, including Japan, China, Vietnam, and Thailand [7, 11–13]. These emerging PEDVs, together with their genetic variants, have initiated a second PED epidemiologic wave worldwide [7, 14]. Thus, PEDVs have been divided into two historical lineages: the “classical” strains that have circulated since the 1970s and the “virulent” strains that emerged after the 2010s. The strains of these lineages have substantial changes in the S region and elsewhere in the genome [7].

PEDV is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the genus Alphacoronavirus of the family Coronaviridae [1]. The genome of PEDV is about 28 kb in length and contains seven open reading frames (ORFs) encoding four major structural proteins (spike, S; envelope, E; membrane, M; and nucleocapsid, N), two nonstructural proteins, and one accessory protein, ORF3 [15]. Similar to other coronaviruses, the S protein of PEDV is the main envelope glycoprotein and a surface antigen that plays an important role in interacting with the glycoprotein receptor on the host cell during infection. Therefore, it contains the antigenic determinant regions that are targets of neutralizing antibodies in natural hosts [16]. The S protein has 1,383–1,386 amino acids (aa), and based on its homology to S proteins of other coronaviruses, consists of two subunits: S1 from aa 1–789 and S2 from aa 790–1383. S1 can be further subdivided into five structural domains: S10 (aa 1–219), S1A (aa 435–485), S1B (aa 510–640), S1C, and S1D (aa 638–789) [17–19]. The S1 region is responsible for viral-host recognition and receptor binding, whereas the S2 region is responsible for membrane fusion and internalization. Mutations occurring in the S gene can result in amino acid changes that affect pathogenicity, transmissibility, antigenic properties, and reactivity with neutralizing antibodies [20]. The S1 region functions as a receptor-binding domain (RBD) and has the ability to recognize a variety of host receptors, including proteins and sugars, that can trigger humoral and cellular responses. Meanwhile, the S2 subunit mediates the membrane fusion process, leading to the release of viral RNA into the host cell [11, 20]. S1 contains two main domains: the N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and the C-terminal domain (S1-CTD) [17]. The S1 protein contains the highly conserved CO26K-equivalent (COE) region (aa 499–638) [21] within the S1-CTD, which can induce the production of neutralizing antibodies and potentially serve as immunogen in vaccines against PEDV [22]. Thus, the S1 subunit is very important in the host defense against PEDV.

The S gene of PEDV undergoes frequent mutation under the pressure of vaccination and herd immunity, with an estimated substitution rate of 1.683 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year and 2.239 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year at the nucleotide and aa level, respectively [23]. As the S protein contains various immunodominant epitopes, this high level of mutation may affect vaccine efficacy. Vaccines derived from classical strains in the G1 group are highly effective against classical PEDV strains but do not provide adequate protection against highly virulent strains in the G2 group [20]. The S1 subunit has an even higher mutation rate than the full S gene, with 1.5 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year [24]. Molecular studies of the S1 region are beneficial for understanding the immune response to genetic variation.

PEDV was detected in Vietnam in 2008 and rapidly spread throughout the country, causing severe economic loss [25]. It is now persistent and circulating in the swine populations [26, 27]. Studies on the S gene sequences of PEDV strains isolated during 2012–2016 showed that these strains had undergone substantial changes [11, 28, 29], which might explain the decrease in vaccine efficiency. Moreover, PEDV continues to predominate in pig populations, even in vaccinated herds, and has become a persistent endemic nationwide [26, 27]. In Vietnam, imported attenuated PEDV and locally produced inactivated vaccines have been used to immunize pigs and sows. These include the imported “Avac PED live” vaccine (AVAC company, Vietnam) and the attenuated “PED Pig VAC” vaccine imported from Daesung Microbiological Labs (South Korea), both of which are produced using the Korean G1a-SM98 strain (GU937797/KOR/SM98/2010) [30]. In addition, inactivated vaccines have also been used, including the combined “Provac TP”, produced using the SM98P strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea and the 175L strain of transmissible gastroenteritis virus, imported from KOMIPHARM International Co., Ltd (South Korea), as well as a local PED vaccine manufactured by the HANVET company in Vietnam (http://hanvet.com.vn/vn/Scripts/default.asp). Despite vaccination, severe outbreaks of PED have been occurring continually in pig herds throughout the whole country. The reasons for vaccine failure might be found by examining genetic variations within the genomes of the currently circulating PEDV strains [28, 29, 31, 32]. There remains a need for molecular analysis of the S1 protein sequences of the clinical strains recently or currently circulating in Vietnam. The neutralizing epitope COE [21] and a portion of the S1D domain (aa 638–733) [33] are among the immunodominant regions of the S protein that are suitable for genogroup-phylogenetic analysis [21, 33, 34]. Therefore, we selected the sequence in the S1-CTD domain that contains the COE to find genetic variation and to discover a new PEDV variant that emerged in northern Vietnam from 2018 to 2019.

In this study, we report variations in the S1-CTD domain that alter the COE of the S1 protein. These data provide information about the evolution of PEDV in Vietnam, which has resulted in a distinct PEDV subgenogroup (“dsG”) or an independent sublineage of new variants with novel mutations. The molecular data obtained are potentially useful not only for selecting appropriate vaccine strains but also for developing alternative vaccines against the PEDV strains circulating in Vietnam.

Fifty samples, including small intestine tissue and feces, were collected in seven provinces from June 2018 to January 2019. We focused on provinces with high densities of commercial pig farms in which PEDV endemics occur annually, as reported in previous publications [26, 27]. These included three clinical samples collected from Ha Noi, two from Hai Duong, eight from Hung Yen, three from Nam Dinh, four from Thanh Hoa, three from Tuyen Quang, and three from Vinh Phuc (Table 1). The collected samples were kept on ice, transported to the laboratory, and stored at –20 °C until used.

Table 1.

List and details of 26 PEDV samples collected from pigs in northern Vietnam from June 2018 to January 2019 used in this study for S1 gene sequence characterization and phylogenetic analysis

| No. | Geographical origin (province) | Sample origin | Collection year | Designated sequence with accession number | Identified genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | MT198679/VN/IBT/2018 | G2b |

| 2 | Vinh Phuc | Intestine | 2018 | MW345259/VN/VP/2018 | G2b |

| 3 | Thanh Hoa | Feces | 2018 | MW345261/VN/TH/2018 | G2b |

| 4 | Nam Dinh | Feces | 2018 | MW345262/VN/ND/2018 | G2b |

| 5 | Hai Duong | Intestine | 2019 | OM681587/VN/HD-1/2018 | G2b |

| 6 | Hung Yen | Intestine | 2018 | OM681592/VN/HY-1/2018 | G2b |

| 7 | Hung Yen | Intestine | 2018 | OM681593/VN/HY-2/2018 | G2b |

| 8 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | OM681594/VN/HY-3/2018 | G2b |

| 9 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | OM681595/VN/HY-4/2018 | G2b |

| 10 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | OM681596/VN/HY-5/2018 | G2b |

| 11 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | OM681597/VN/HY-6/2018 | G2b |

| 12 | Hung Yen | Feces | 2018 | OM681598/VN/HY-7/2018 | G2b |

| 13 | Nam Dinh | Feces | 2018 | OM681599/VN/ND-1/2018 | G2b |

| 14 | Nam Dinh | Intestine | 2018 | OM681600/VN/ND-2/2018 | G2b |

| 15 | Thanh Hoa | Intestine | 2018 | OM681601/VN/TH-1/2018 | G2b |

| 16 | Thanh Hoa | Intestine | 2018 | OM681602/VN/TH-2/2018 | G2b |

| 17 | Thanh Hoa | Feces | 2018 | OM681603/VN/TH-3/2018 | G2b |

| 18 | Vinh Phuc | Intestine | 2018 | OM681606/VN/VP-1/2018 | G2b |

| 19 | Vinh Phuc | Feces | 2018 | OM681607/VN/VP-2/2018 | G2b |

| 20 | Tuyen Quang | Intestine | 2019 | MW345260/VN/TQ/2019 | *Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 21 | Tuyen Quang | Intestine | 2018 | OM681604/VN/TQ-1/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 22 | Tuyen Quang | Feces | 2018 | OM681605/VN/TQ-2/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 23 | Hai Duong | Feces | 2018 | OM681588/VN/HD-2/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 24 | Ha Noi | Intestine | 2018 | OM681589/VN/HN-1/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 25 | Ha Noi | Feces | 2018 | OM681590/VN/HN-2/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

| 26 | Ha Noi | Feces | 2018 | OM681591/VN/HN-3/2018 | Distinct sG (dsG) |

*Distinct sG (dsG): a distinct subgenogroup predicted among the Vietnamese PEDV strains in this study (2018–2019)

Fecal or intestinal samples were homogenized in sterile water and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and the RNA was suspended in DEPC-treated water and stored at –80 °C. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using a Maxima Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA). A pair of oligonucleotide primers, PEDV-F (5’-TTCTGAGTCACGAACAGCCA-3’, S gene, nt 1475–1494) and PEDV-R (5’-CATATGCAGCCTGCTCTGAA-3’, S gene, nt 2106–2125), amplifying a fragment of the S1-CTD region (651 nt in length) was used to screen for PEDV-positive samples. PCR was performed on a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, California, USA) with one cycle of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

The PCR products (651 bp) were purified using a GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and sequenced, either directly or after cloning into the pCR2.1-TOPO TA-cloning vector (Invitrogen, USA), by a service company. The resulting sequences were assembled using BioEdit software (https://ittechgyan.com/bioedit-full-version-7-2-download/) and used as queries to search the NCBI database using BLASTn and BLASTx. The partial S1 sequence of 630 nucleotides obtained from each sample in this study and reference sequences from previous studies and from the GenBank database were used for sequence comparisons.

An alignment of 61 partial S1 nucleotide sequences (630 nt of the S1-CTD region, nt 1480–2110), including those of 26 of PEDV isolates from northern Vietnam (Table 1) and 35 reference strains of G1a (four strains), G1b (three strains), recombinant/G1c (12 strains), G2a (six strains), and G2b (eight strains) (Supplementary Table S1), was made using the GENEDOC 2.7 program (https://softdeluxe.com/GeneDoc-180568/download/) for sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis. For phylogenetic reconstruction, MEGA X (https://www.megasoftware.net/) was used, employing the maximum-likelihood method with the general time-reversible GTR + G + I model and 1000 bootstrap replications [35]. The (sub)genotype-representative strains included in the alignment were the prototype strain Belgium/CV777/2001 (AF353511) and the vaccine strain Korea/SM98-5P/1998 (KJ857455) for subgroup G1a, the attenuated CV777 vaccine strain (JN599150) for subgroup G1b, the virulent CH/HNAY/2015 strain (KR809885) for subgroup G2a, and the vaccine strain AJ1102 (JX188454) for subgroup G2b. In addition, some recombinant strains reported recently in the United States (for example, strain USA/Iowa/2013), in China (such as ZL29, CH/SCZY44/2017), and Taiwan (TW/Yunlin550/2018, suggested as G1c) as US-like and/or recombinant strains were also included for reference. Amino acid sequences of 26 Vietnamese and one G1a (CV777, 1a-AF353511/BE/CV777/2001) reference strains were also aligned for genotypic and antigenic comparisons.

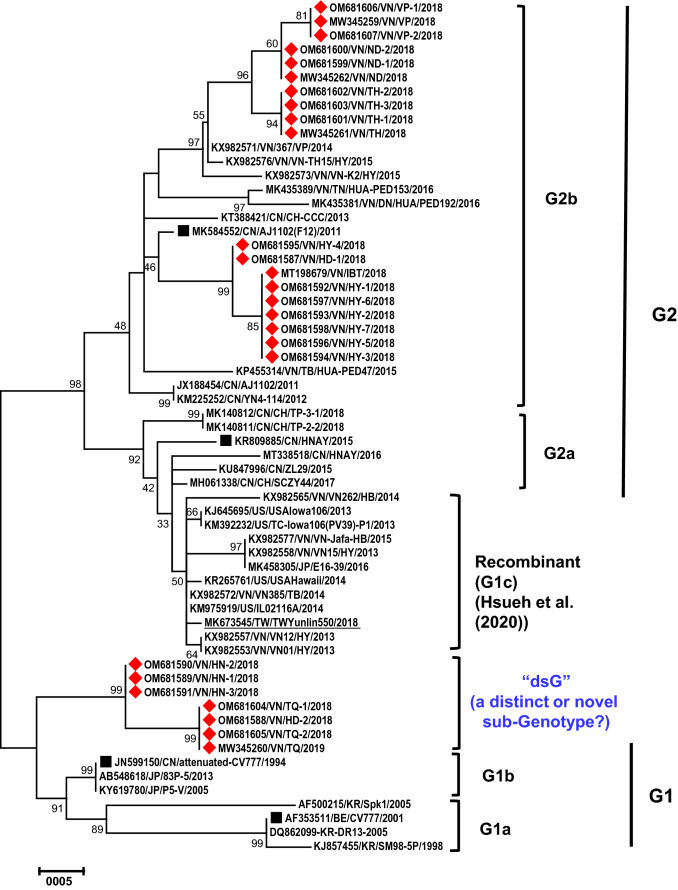

The ML phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 1 indicated that all of the strains were divided into two major groups: G1 (classical strains) and G2 (virulent pandemic strains) [7]. The phylogenetic tree classified the 26 Vietnamese PEDV strains into G2b (19/26 = 73.1%) and a distinct subgroup (7/26 = 26.9%). Nineteen strains belonging to G2b were collected in 2018. Those included the strains isolated in the provinces of Thanh Hoa (n = 4; MW345261, OM681601, OM681602, and OM681603), Vinh Phuc (n = 3; MW345259, OM681606, and OM681607), Nam Dinh (n = 3; MW345262, OM681599, and OM681600), Hung Yen (n = 8; MT198679, OM681592, OM681593, OM681594/VN, OM681595, OM681596, OM681597, and OM681598), and Hai Duong (one strain: OM681587) (Table 1). They were placed in a group with the reference strain MK584552/CN/AJ1102(F12)/2011 and six previously reported Vietnamese and three Chinese G2b strains. Nine of these strains belonged to the same branch of G2b as the classical AJ1102 vaccine strain, while 10 belonged to a different cluster that included previously identified Vietnamese G2b strains isolated between 2014 and 2016 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S1) [13, 29]. None of the 26 strains from the current study were placed in the G2a or G1c (or recombinant) clusters [34].

Fig. 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the alignment of 61 S1-CTD nucleotide sequences (630 nucleotides) of PEDV G1a, 1b, 2a, 2b isolates and recombinant strains (or G1c) [34], including 26 Vietnamese strains from this study and 35 reference strains. The phylogenetic tree reconstruction was performed in MEGA X using the maximum-likelihood method with the general time-reversible GTR + G + I model. Support for each node was tested by 1000 bootstrap resamplings [35], and only bootstrap values greater than 30% are shown. The Vietnamese PEDV strains in this study are indicated by a diamond symbol, and the reference strains representing different genogroups are indicated by a square symbol. A cluster formed by seven Vietnamese strains that are distinct from the other PEDV sequences is designated as the “dsG” subgroup, which is bracketed between the G1 and G2 genogroups. For each sequence, following the accession number is the abbreviation of the country’s name (two-letter: https://www.iban.com/country-codes) and the strain designation. The year of isolation is given at the end of each sequence name. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Notably, in the tree presented in Fig. 1, the phylogenetic topology clearly indicated a paraphyletic group of seven strains from the G1a and G1b subgenogroups. These seven strains were in a basal position, bracketed between G1 and G2, separate from G1a, G1b, and G1c, with a high bootstrap value (98%). This branch included three strains isolated in Ha Noi (n = 3; OM681589, OM681590, and OM681591), three isolated in Tuyen Quang (n = 3; MW345260, OM681604, and OM681605), and one isolated in Hai Duong (OM681588). We designated this novel sub-genogroup as “dsG” (distinct subgenotype) (Fig. 1, Table 1), and we propose that it might represent a novel “G1d” subgroup.

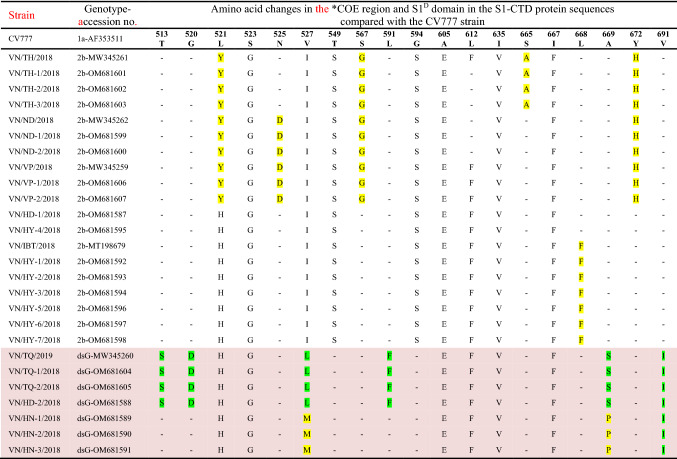

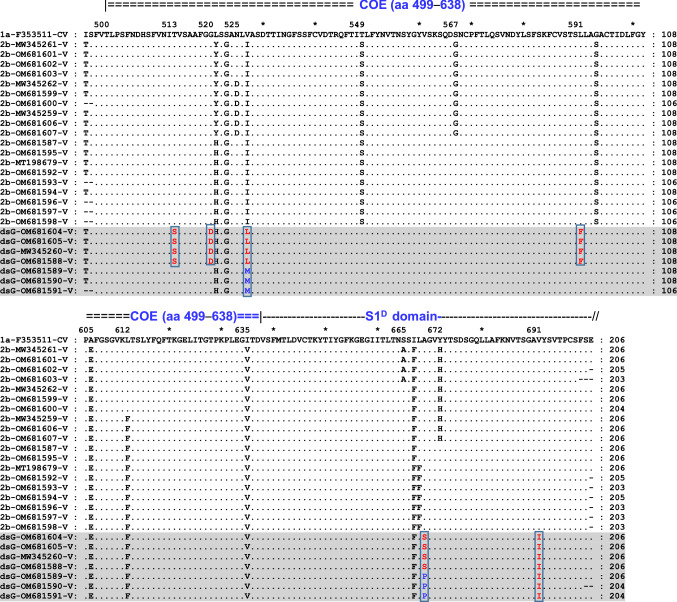

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show amino acid variations in the S1-CTD region (aa 495–700) compared with the prototype CV777 strain for the 26 Vietnamese PEDV isolates from the current study, and Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the variations in these 26 strains and 35 other reference strains (listed in Supplementary Table S1). A total of 19 amino acid substitutions were observed in the 26 Vietnamese strains studied (Table 2). Thirteen variations, including 513T>S, 520G>D, 521L>(Y/H), 523S>G, 525N>D, 527V>(I/L/M), 549T>S, 567S>G, 591L>F, 594G>S, 605A>E, 612L>F and 635I>V, were in the COE domain, and the other six (665S>A, 667I>F, 668L>F, 669A>(S/P), 672Y>H, and 691V>I) were found in the S1D region. Among these, 521L>Y, 525N>D, 567S>G, 665S>A, 668L>F, and 672Y>H were found in some of the Vietnamese G2b strains from this study, while 513T>S, 520G>D, 527V>(L/M), 591L>F, 669A>(S/P), and 691V>I were restricted to the seven strains of the distinct subgroup (Table 2; Fig. 2, and Supplementary S1). The amino acid changes in the distinct subgroup affecting neutralization epitopes in the COE domain have not been reported in any global strains studied so far, and thus, they are unique to the emerging Vietnamese PEDV strains, representing new variant antigenic sites in the S1 spike protein subunit. The identification of a new antigenic variant subgroup revealed the continuous evolution of the S1 region of the currently circulating Vietnamese PEDV strains [13, 29], and this emphasizes the need for frequent updates of vaccines for effective protection.

Table 2.

Amino acid variations in the S1-CTD region of the 26 Vietnamese PEDV isolates compared with the prototype CV777 strain

*COE, CO-26 K equivalent epitope (aa 499–638) containing amino acids recognized by neutralizing antibodies; S1D, S1D subdomain in the protein S1 (aa 638–789) (see Hsueh et al. [34]); S1-CTD, S1 C-terminal domain; dsG, distinct subgenogroup predicted among the Vietnamese PEDV strains in this study (2018–2019). Seven strains of the distinct subgenogroup (dsG) are shaded, and the distinct amino acid changes are highlighted. The distinguishing aa changes in some strains of the Vietnamese G2b subgroup are also highlighted.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of the partial S1-CTD protein sequences (deduced from 630 nt) of 27 PEDV strains, including 26 clinical strains from this study and the classical C777 strain (AF353511/BE/CV777/2001), representing genogroup 1a (G1a). The top line is the amino acid sequence for the C777 strain. Residues in the aligned sequences that are identical to those of the C777 strain are indicated by dots, and differences are indicated by single letters. The highly conserved core neutralizing epitope (COE) (aa 499–638) and S1D domain are indicated at the top. The aligned sequences of seven Vietnamese PEDV strains identified as belonging to a distinct subgenogroup (designated as dsG) are shaded in gray, and the distinct residues are colored and vertically boxed. Accession numbers and subgenotypes are shown at the start of the sequences.

Notably, some of the Vietnamese G2b strains studied had distinguishing aa changes, including 521L>Y, 525N>D, 567S>G, 665S>A, 668L>F, and 672Y>H (Supplementary Fig. S1; Table 2) when compared to recently reported G2b strains [13, 29, 30], and seven strains of the distinct subgroup had the unique aa changes 513T>S, 520G>D, 527V>(L/M), 591L>F, 669A>(S/P), and 691V>I, which had not been described previously (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). Furthermore, 10 G2b strains from this study, together with some other Vietnamese PEDV strains from previous reports, formed a cluster that was separate from the one including AJ1102-based vaccine strains (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that deep diversification has occurred within the PEDV population infecting pigs in Vietnam.

As reported previously, strains of subgroup G1b were predominant in Vietnam before 2014 [13, 29, 30]. In 2015–2016, the G2 group was dominant worldwide, with the presence of subgroups G2a and G2b [29]. As shown in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) and aa sequence comparisons (Table 2, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Fig. S1), the Vietnamese G2b PEDV strains isolated from 2014 onwards appear to have undergone a certain degree of evolution and were located in clusters that were separate from those containing the original AJ1102 G2b strains isolated in 2011–2012. Therefore, the G2 strains, particularly the “new” G2b strains, now appear to be the main threat for PEDV infection in Vietnam, as the classical vaccine strains provide limited protection against the non-S INDEL strains [36, 37].

It is noteworthy, however, that in comparison with the attenuated vaccine strains CV777 (JN599150), AJ1102 (MK584552), and Korea/SM98-5P/1998 (KJ857455), which are used globally for immunization, apart from the aa changes that were found in previous studies [11, 29], the Vietnamese PEDV strains from different geographical regions in this study also possessed six distinct mutations. These (513T>S, 520G>D, 527V>(L/M), 591L>F, 669A>(S/P), and 691V>I) occurred in the COE and S1D regions, restricted to the distinct subgroup of the most recently emerging PEDV strains in Vietnam (Table 2). Changes in a range of epitopic residues of the immunodominant regions may contribute to redistribution of the capsid surface, producing new protruding conformational epitopes, and to alterations in the conformational specificity for immunity and receptor binding, leading to the development of novel antigenic variants that help the virus escape the host immune response [20, 22]. A study by Ji et al. [20] showed that a 4-aa insertion in the COE region of the S protein resulted in the formation of an extra alpha helix, which partly altered the reactivity profiles of neutralizing antibodies. The sequence data from this study indicated that the Vietnamese PEDV strains might have experienced dramatic antigenic drift, which ultimately led to reduced protection by classical-strain-based vaccines and resulted in a relatively high infection rate on pig farms.

According to previous evolutionary analyses based on nucleotide sequences, PEDV is divided into two groups: the classical G1 group and the pandemic G2 group. Each group can be divided further into at least two subgroups, including G1a, G1b, G2a, and G2b, and probably G2c [33]. The G1a subgroup includes the cultured vaccine strains CV777 (JN599150/CN/attenuated-CV777/1994) and DR13 (DQ862099/KR/DR13/2005). The G1b subgroup includes new variant strains discovered first in China, then in the United States, South Korea, and, more recently, in European countries [38, 39]. The G2 strains arose from G1a strains due to point mutations. While most of the G2a subtype strains originated in the United States and a small part of China, Japan, or individual regions with small outbreaks, the G2b subgenogroup is the major cause of the pandemic outbreaks in Asian countries, especially China, Japan, and South Korea [14, 33, 38].

Recently, many recombinant PEDV strains have been reported globally. The G1c subgroup contains strains that are recombinants of G1a and G2a strains, and these include strains identified in the USA (such as USA/Iowa106/2013) and in Europe with high sequence similarity to the Chinese recombinant ZL29/2015 strain (G2c subgenotype) [33]. Meanwhile, the strains in the S-INDEL G1c subgroup resulted from recombination events between a G2b strain and a wild-type G1 strain (such as strain TW/Yunlin/2018) [34] or a variant G1 strain (such as strain CH/SCZY44/2017) [40]. These recombinant strains were also included in our study as references. However, as the C-terminal region of the S1 PEDV G1c strains was highly similar to that of G2b strains [34], the phylogenetic tree based on the S1-CTD region used in this study placed these recombinant strains close to other G2b strains, outside of G1 and between G1 and G2.

The phylogeny based on partial S1 sequences indicated that the newly discovered distinct subgroup was placed outside of G1 and G2 and was between the G1 and G2 genogroups (Fig. 1). To determine whether this reflects the accurate taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships between strains, it will be necessary to sequence the complete S1 region of all of these isolates, as well as the entire genome of more representatives of these “novel” antigenic variant strains. The complete S1 spike sequence phylogeny will give higher resolution, and the complete genomic sequence analysis will better resolve the taxonomic status of these isolates. Further detailed genome characterization and protein structure prediction, as well as testing their antigenicity/immunogenicity will be useful for developing a strategy for making alternative vaccines in the near future [32]. This research highlights the need for frequent vaccine updates to ensure protection efficacy despite the continuous evolution of PEDV [37, 41, 42].

In conclusion, phylogenetic analysis and comparisons of 26 Vietnamese PEDV S1-CTD sequences from samples collected from seven northern provinces from June 2018 to January 2019 revealed the presence of two subgenogroups of virulent strains in Vietnam: diversified G2b and an independent “distinct subgenogroup” (dsG), which is separate from G1a, G1b, G2a, G2b, and G1c (recombinant strains) and possesses distinct variations in neutralizing epitopes in the COE and S1D regions that are unique to the emerging Vietnamese PEDV strains. PEDV is rapidly evolving in Vietnam, and this may result in vaccination failure in pig herds immunized with classical vaccines. This suggests the need for frequent updates of vaccines for effective protection in Vietnam and other countries.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology under grant no. VAST02.03/20-21. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

DBTT performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft. TPTP analyzed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. HNT, THT, and PMH performed the experiments. LTH analyzed and finalized the data, prepared tables and figures, and reviewed drafts of the paper. QDV conceived and designed the experiments and authored or reviewed drafts of the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study are available in the GenBank database and in the online supplementary materials and can also be made available by the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The samples were collected with legal informed consent of the owners.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Thanh Hoa Le, Email: imibtvn@gmail.com.

Dong Van Quyen, Email: dvquyen@gmail.com, Email: dvquyen@ibt.ac.vn.

References

- 1.Pensaert MB, de Bouck P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch Virol. 1978;58(3):243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinrigl A, Revilla Fernández S, Stoiber F, Pikalo J, Sattler T, Schmoll F. First detection, clinical presentation and phylogenetic characterization of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Austria. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Okada K, Ohshima K. An outbreak of swine diarrhea of a new-type associated with coronavirus-like particles in Japan. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi Jpn J Vet Sci. 1983;45(6):829–832. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.45.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JF, Sun DB, Wang CB, Shi HY, Cui XC, Liu SW, Qiu HJ, Feng L. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of membrane protein genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus isolates in China. Virus Genes. 2008;36(2):355–364. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puranaveja S, Poolperm P, Lertwatcharasarakul P, Kesdaengsakonwut S, Boonsoongnern A, Urairong K, Kitikoon P, Choojai P, Kedkovid R, Teankum K, Thanawongnuwech R. Chinese-like strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(7):1112–1115. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.081256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson GW, Hoang H, Schwartz KJ, Burrough ER, Sun D, Madson D, Cooper VL, Pillatzki A, Gauger P, Schmitt BJ, Koster LG, Killian ML, Yoon KJ (2013) Emergence of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in the United States: clinical signs, lesions, and viral genomic sequences. J Vet Diagn Investig Off Publ Am Assoc Vet Lab Diagn Inc 25(5):649–654. 10.1177/1040638713501675 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lin CM, Saif LJ, Marthaler D, Wang Q. Evolution, antigenicity and pathogenicity of global porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains. Virus Res. 2016;226:20–39. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Lee C. Outbreak-related porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains similar to US strains, South Korea, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7):1223–1226. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanke D, Jenckel M, Petrov A, Ritzmann M, Stadler J, Akimkin V, Blome S, Pohlmann A, Schirrmeier H, Beer M, Höper D. Comparison of porcine epidemic diarrhea Viruses from Germany and the United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(3):493–496. doi: 10.3201/eid2103.141165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin CN, Chung WB, Chang SW, Wen CC, Liu H, Chien CH, Chiou MT. US-like strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus outbreaks in Taiwan, 2013–2014. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76(9):1297–1299. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diep NV, Norimine J, Sueyoshi M, Lan NT, Hirai T, Yamaguchi R. US-like isolates of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus from Japanese outbreaks between 2013 and 2014. Springerplus. 2015;4:756. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1552-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheun-Arom T, Temeeyasen G, Tripipat T, Kaewprommal P, Piriyapongsa J, Sukrong S, Chongcharoen W, Tantituvanont A, Nilubol D. Full-length genome analysis of two genetically distinct variants of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Thailand. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;44:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diep NV, Sueyoshi M, Izzati U, Fuke N, Teh APP, Lan NT, Yamaguchi R. Appearance of US-like porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PEDV) strains before US outbreaks and genetic heterogeneity of PEDVs collected in Northern Vietnam during 2012–2015. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(1):e83–93. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He WT, Bollen N, Xu Y, Zhao J, Dellicour S, Yan Z, Gong W, Zhang C, Zhang L, Lu M, Lai A, Suchard MA, Ji X, Tu C, Lemey P, Baele G, Su S (2022) Phylogeography reveals association between swine trade and the spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China and across the World. Mol Biol Evol 39(2):msab364. 10.1093/molbev/msab364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Duarte M, Tobler K, Bridgen A, Rasschaert D, Ackermann M, Laude H. Sequence analysis of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus genome between the nucleocapsid and spike protein genes reveals a polymorphic ORF. Virology. 1994;198(2):466–476. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackwood MW, Hilt DA, Callison SA, Lee CW, Plaza H, Wade E. Spike glycoprotein cleavage recognition site analysis of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis. 2001;45(2):366–372. doi: 10.2307/1592976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Tang J, Ma Y, Liang X, Yang Y, Peng G, Qi Q, Jiang S, Li J, Du L, Li F. Receptor usage and cell entry of porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus. J Virol. 2015;89(11):6121–6125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00430-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Li W, Lucio de Esesarte E, Guo H, van den Elzen P, Aarts E, van den Born E, Rottier PJM, Bosch BJ. Cell attachment domains of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein are key targets of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2017;91(12):e00273–e317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00273-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CY, Cheng IC, Chang YC, Tsai PS, Lai SY, Huang YL, Jeng CR, Pang VF, Chang HW. Identification of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies targeting novel conformational epitopes of the porcine epidemic Diarrhoea virus spike protein. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2529. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39844-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji Z, Shi D, Shi H, Wang X, Chen J, Liu J, Ye D, Jing Z, Liu Q, Fan Q, Li M, Cong G, Zhang J, Han Y, Zhang X, Feng L. A porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain with distinct characteristics of four amino acid insertion in the COE region of spike protein. Vet Microbiol. 2021;253:108955. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang SH, Bae JL, Kang TJ, Kim J, Chung GH, Lim CW, Laude H, Yang MS. Jang YS. Identification of the epitope region capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies against the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Mol Cells. 2002;14:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Li Q, Shao C, Ma Y, He H, Jiang S, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Ba S, Shi L, Fang W, Wang X, Song H. Isolation and characterization of Chinese porcine epidemic diarrhea virus with novel mutations and deletions in the S gene. Vet Microbiol. 2018;221:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang G, Park J, Lee C. Successful eradication of porcine epidemic diarrhea in an enzootically infected farm: a two-year follow-up study. Pathogens. 2021;10(7):830. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10070830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis MC, Lam HC, Zhang Y, Wang L, Hesse RA, Hause BM, Vlasova A, Wang Q, Zhang J, Nelson MI, Murtaugh MP, Marthaler D. Genomic and evolutionary inferences between American and global strains of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Prev Vet Med. 2016;123:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Do DT, Toan NT, Puranaveja S, Thanawongnuwech R (2011) Genetic characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) isolates from southern Vietnam during 2009–2010 outbreaks. Thai J Vet Med 41(1):55–64. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tjvm/article/view/9474

- 26.Mai TN, Yamazaki W, Bui TP, Nguyen VG, Le Huynh TM, Mitoma S, Daous HE, Kabali E, Norimine J, Sekiguchi S. A descriptive survey of porcine epidemic diarrhea in pig populations in northern Vietnam. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2020;52(6):3781–3788. doi: 10.1007/s11250-020-02416-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myint O, Hoa NT, Fuke N, Pornthummawat A, Lan NT, Hirai T, Yoshida A, Yamaguchi R. A persistent epidemic of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus infection by serological survey of commercial pig farms in northern Vietnam. BMC Vet Res. 2021;17(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02941-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YK, Lim SI, Lim JA, Cho IS, Park EH, Le VP, Hien NB, Thach PN, Quynh DH, Vui TQ, Tien NT, An DJ. A novel strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Vietnamese pigs. Arch Virol. 2015;160(6):1573–1577. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Than VT, Choe SE, Vu TTH, Do TD, Nguyen TL, Bui TTN, Mai TN, Cha RM, Song D, An DJ, Le VP. Genetic characterization of the spike gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses (PEDVs) circulating in Vietnam from 2015 to 2016. Vet Med Sci. 2020;6(3):535–542. doi: 10.1002/vms3.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SH, Lee JM, Jung J, Kim IJ, Hyun BH, Kim HI, Park CK, Oem JK, Kim YH, Lee MH, Lee KK. Genetic characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Korea from 1998 to 2013. Arch Virol. 2015;160(4):1055–1064. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2353-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vui DT, Thanh TL, Tung N, Srijangwad A, Tripipat T, Chuanasa T, Nilubol D. Complete genome characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Vietnam. Arch Virol. 2015;160(8):1931–1938. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran TX, Lien NTK, Thu HT, Duy ND, Duong BTT, Quyen DV. Changes in the spike and nucleocapsid protein of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain in Vietnam-a molecular potential for the vaccine development? PeerJ. 2021;9:e12329. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo J, Fang L, Ye X, Chen J, Xu S, Zhu X, Miao Y, Wang D, Xiao S. Evolutionary and genotypic analyses of global porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;66(1):111–118. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsueh FC, Lin CN, Chiou HY, Chia MY, Chiou MT, Haga T, Kao CF, Chang YC, Chang CY, Jeng CR, Chang HW. Updated phylogenetic analysis of the spike gene and identification of a novel recombinant porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus strain in Taiwan. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67(1):417–430. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goede D, Murtaugh MP, Nerem J, Yeske P, Rossow K, Morrison R. Previous infection of sows with a “mild” strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus confers protection against infection with a “severe” strain. Vet Microbiol. 2015;176(1–2):161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung K, Saif LJ, Wang Q. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV): an update on etiology, transmission, pathogenesis, and prevention and control. Virus Res. 2020;286:198045. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: An emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol J. 2015;12:193. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu L, Liu Y, Wang S, Zhang L, Liang P, Wang L, Dong J, Song C. Molecular characteristics and pathogenicity of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus isolated in some areas of China in 2015–2018. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:607662. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.607662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang PH, Li YQ, Pan YQ, Guo YY, Guo F, Shi RZ, Xing L. The spike glycoprotein genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses isolated in China. Vet Res. 2021;52(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s13567-021-00954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song D, Moon H, Kang B. Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a review of current epidemiology and available vaccines. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2015;4(2):166–176. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2015.4.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z, Ma Z, Li Y, Gao S, Xiao S. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: molecular mechanisms of attenuation and vaccines. Microb Pathog. 2020;149:104553. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study are available in the GenBank database and in the online supplementary materials and can also be made available by the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.