Abstract

The newborn immune system is characterized by diminished immune responses that leave infants vulnerable to virus-mediated disease and make vaccination more challenging. Optimal vaccination strategies for influenza A virus (IAV) in newborns should result in robust levels of protective antibodies, including those with broad reactivity to combat the variability in IAV strains across seasons. The stem region of the hemagglutinin (HA) molecule is a target of such antibodies. Using a nonhuman primate model, we investigate the capacity of newborns to generate and maintain antibodies to the conserved stem region following vaccination. We find adjuvanting an inactivated vaccine with the TLR7/8 agonist R848 is effective in promoting sustained HA stem-specific IgG. Unexpectedly, HA stem-specific antibodies were generated with a distinct kinetic pattern compared to the overall response. Administration of R848 was associated with increased influenza-specific T follicular helper cells as well as Tregs with a less suppressive phenotype, suggesting adjuvant impacts multiple cell types that have the potential to contribute to the HA-stem response.

Subject terms: Adjuvants, Inactivated vaccines

Introduction

Attempts to develop a vaccine conferring multi-season protection from influenza A virus (IAV) have long been hindered by viral antigenic shift and drift that allows the virus to escape from immune recognition1–3. To overcome this hurdle, there has been a recent focus on the elicitation of antibodies (Ab) targeting conserved viral structures. The most extensively studied of these is the stem region of the hemagglutinin (HA) surface protein, which is responsible for viral attachment and fusion4–8. While the HA stem is highly conserved across strains, it is not highly immunogenic, resulting in preferential generation of Ab responses to variable epitopes on the HA head9–11. Although this phenomenon of Ab immunodominance to IAV epitopes has been reported, the mechanisms driving it are poorly understood12–14.

Newborns are a population that is particularly vulnerable to severe disease following IAV infection15,16. In general, the newborn immune system favors tolerance over strong inflammatory and antiviral responses. While this is important to limit responses to environmental antigens and allow colonization by healthy microbiota17,18, it can lead to inadequate clearance of pathogens. Susceptibility to severe disease is further exacerbated by the lack of an effective IAV vaccine for infants under 6 month of age. The limited immune response to vaccination in young infants manifests as reduced production and maintenance of high-titer, high-affinity antibodies following antigen exposure19.

The generation of a high-quality antibody response relies on the effective coordination and interaction of a multitude of immunologic factors. While newborn B cells have been demonstrated to have intrinsic defects in activation, signaling, and maturation20–26, they are also impaired by diminished T cell help, immunosuppression, and structural changes in the lymphoid microenvironment that inhibit differentiation and survival27–29. In particular, newborns have impaired formation of germinal centers (GC) required for maturation and differentiation of memory B cells (MBC) and long-lived plasma cells (LLPC)30–32. In addition to structural constraints from stromal cells, alterations in the generation of T follicular helper cells (Tfh) and dendritic cell (DC) function have been identified as major barriers to effective GC formation and function32–34. Difficulties in mounting robust antibody responses are further exacerbated by increases in the number and activity of immunosuppressive Tregs during early life35,36.

The complex interaction of the many factors that regulate an antibody response makes this a highly dynamic process, especially since the acute effector and lasting MBC/LLPC responses are regulated by different processes. Similarly, the immunodominance hierarchy of Ab specificities to distinct epitopes evolves over time, suggesting that the selection criteria for dominant epitope specificities may shift and change over the course of the GC reaction37. At present, the mechanisms dictating antibody immunodominance are not well understood. One appealing model is that it immunodominance is, at least in part, the product of clonal competition within the GC and alleviating this competitive pressure can facilitate the expansion of subdominant clones, e.g., those specific for the HA-stem region. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that Ab responses to subdominant epitopes may be improved by increasing the accessibility of resources to clones that may be less competitive (e.g., increasing antigen dose or T cell help) as well as removing negative selection pressures (e.g., by reducing Treg suppression or targeted elimination of dominant clones)38–42. Unsurprisingly, many of the factors implicated in establishing an immunodominance hierarchy are involved in the normal maturation and differentiation of the antibody response43,44. This suggests overcoming subdominance of the HA stem and improving maintenance of the desired Ab response may be tightly entwined. It is not clear how the early life alterations in the function and development of immune cells involved in these processes may affect the dynamic immunodominance hierarchy.

Although a variety of strategies have been employed in attempts to elicit robust, persistent responses to conserved subdominant epitopes, the use of immune adjuvants is particularly appealing considering their ability to act upon a broad range of immune targets. Several reports in adult models have demonstrated that adjuvants can improve the quality and quantity of cross-protective antibody elicited by vaccination31,45–50. Using a nonhuman primate (NHP) model, we have previously shown that inclusion of the TLR agonist (TLRa) adjuvants flagellin and R848, either singly or in combination with a killed IAV vaccine, can improve the titer and consequently increased persistence of total IAV-specific Ab51–54. Further, we have demonstrated that newborn NHP are capable of producing a robust Ab response to the HA stem following infection with IAV55. We have also observed a beneficial effect of R848 on the early production of stem-specific antibody56. Here, we extend our studies into the elicitation of HA stem-specific antibodies in newborns by assessing the ability of flagellin and R848 to serve as adjuvants that can impact the kinetics and maintenance of a stem-specific Ab response as well as modulate immune populations that may regulate these responses. The NHP model used in these studies represent an extremely important translational model due to their immunologic, developmental, and physiologic similarities with humans57.

Results

TLRa adjuvants elicit a stem response upon vaccine boost

The generation of HA stem-specific antibody as a result of vaccination is challenging, given the subdominant nature of this response in the context of the HA molecule10. We have previously shown that inactivated influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 virus (IPR8) admixed with flagellin (IPR8 + flg), directly conjugated to R848 (IPR8-R848), or the combination of both adjuvants (IPR8-R848 + flg) all increase IAV-specific IgG titers in newborn nursery-reared African green monkeys (AGM) as compared to non-adjuvanted IPR851–54. Here, IPR8 with an inactive flagellin mutant (m229), which has a biologically inactive hypervariable region58, served as a non-adjuvanted vaccine. We have also demonstrated that prime and boost of nursery-reared AGM newborns with IPR8-R848 can improve both total and neutralizing titers of stem-specific antibody following live viral challenge at early points after vaccination56.

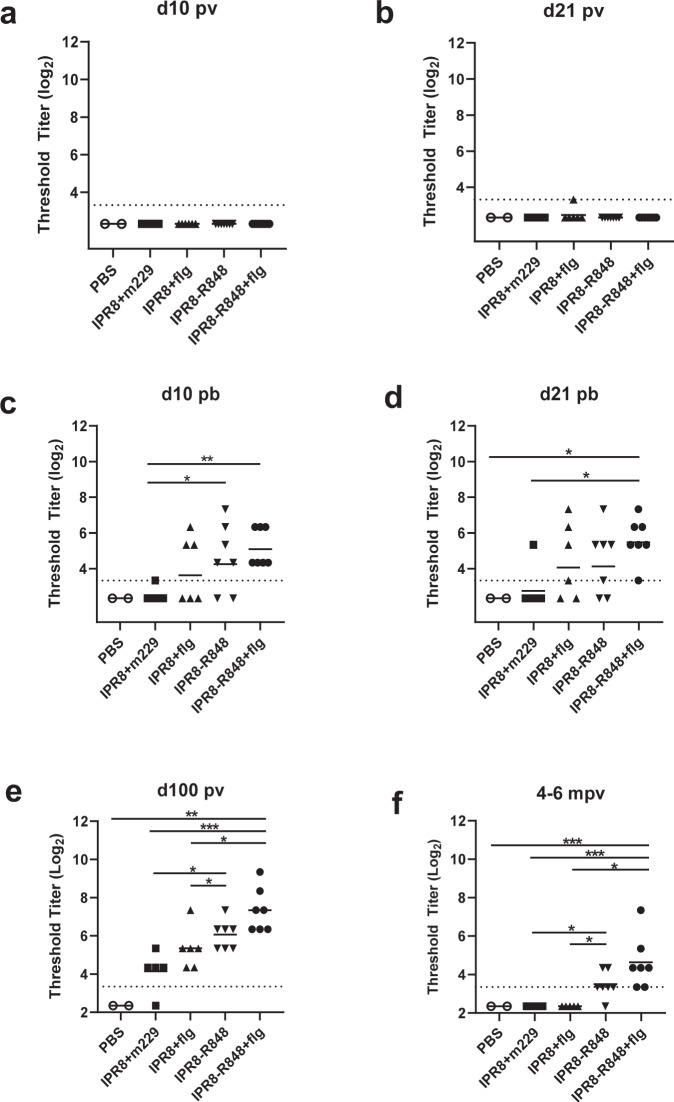

To investigate the ability of flagellin, R848, or the combination to elicit a sustained stem-specific antibody response, we measured plasma titers of stem-specific IgG in a cohort of mother-reared newborn NHP following vaccination using IPR8 with or without adjuvant. IgG specific to the HA A/California/4/2009 (Ca09) stem was not detectable by ELISA at day 10 postvaccination (p.v.), regardless of adjuvant strategy (Fig. 1a). At day 21 p.v., among newborns receiving adjuvanted vaccines, only a single animal (in the IPR8 + flg group) had detectable Ab capable of recognizing HA stem. Thus, a single dose of killed IAV vaccine did not readily elicit a detectable antibody response to the HA stem even in the presence of adjuvants (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Vaccination with a TLRa adjuvanted vaccine elicits IgG to the HA stem.

Newborn AGM received IPR8 with soluble flagellin (IPR8 + flg) (n = 6), conjugated to R848 (IPR8-R848) (n = 7), the combination of flagellin and IPR8-R848 (IPR8-R848 + flg) (n = 7), without functional adjuvant (IPR8 + m229) (n = 5), or PBS as a vehicle control (n = 3). Newborns were boosted with the same at d21 p.v. Plasma IgG titers to stabilized Ca09 HA stem were measured by ELISA at days 10 and 21 p.v. (a, b) or p.b. (c, d), approximately d100 p.v. (e) and 4-6 months (f) following initial vaccination. Data are shown as threshold titer (the lowest dilution at which sample OD was at least three times that of the assay background). The limit of detection (dotted line) is defined as the lowest sample dilution in the assay. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Next, we investigated whether a secondary exposure to a TLRa adjuvanted vaccine at 21 days following initial vaccine administration was capable of inducing a detectable stem-specific antibody response. Groups vaccinated with IPR8 + flg or IPR8-R848 contained both responder and non-responder animals. Three of six (50%) newborns in the IPR8 + flg group and five of seven (71%) newborns in the IPR8-R848 group had detectable stem-specific IgG at day 10 post-boost (p.b.) (Fig. 1c). One additional IPR8 + flg vaccinated newborn became positive at d21 p.b. (Fig. 1d). All newborns receiving IPR8-R848 + flg displayed a detectable IgG response to the HA stem at both d10 and d21 p.b. In contrast, only one animal receiving IPR8 + m229 had stem-specific IgG titers at or above the limit of detection. Interestingly, both groups receiving IPR8-R848 and IPR8-R848 + flg had a significant increase in stem-specific IgG compared to the non-adjuvanted group at day 10 p.b., while only animals receiving IPR8-R848 + flg maintained significantly higher titers at day 21 p.b. These data show that inclusion of adjuvants can drive the production of antibodies to HA stem and that a major effect of adjuvants was the increased proportion of newborns with detectable stem-specific antibody.

Inclusion of R848 adjuvant prolongs the presence of circulating stem-specific Abs

The newborn immune system is particularly challenged in the development of lasting immunity, i.e., Ab titers often wane rapidly compared to adults59. The presence of sustained Ab responses is dependent on development of LLPC. The process of selection, maturation, and differentiation in the GC can continue for weeks to months following antigen encounter. Thus, we measured plasma IgG to stem at later times following initial vaccination (~100 days and 4-6 months). Unexpectedly, given the findings at d21 p.b., all vaccinated animals, exempting one, that had received IPR8 + m229 had detectable IgG to the HA stem at this timepoint (Fig. 1e). Thus, the response measured at d21 p.b. did not fully predict the presence of stem-specific IgG generated following vaccination.

Although all but one infant had detectable stem-specific Ab, the amount present at d100 p.v. was dependent on the adjuvant. Animals receiving the IPR8-R848 + flg showed the highest amount of stem-specific IgG, although animals administered IPR8-R848 alone also displayed a significant increase compared to the IPR8 + m229 group (Fig. 1e). It was notable that the presence of flagellin did not result in significant increases in stem-specific antibody compared to the non-adjuvanted vaccine at this timepoint (Fig. 1e). Together, these data show that expansion of stem-specific IgG continues beyond d21 p.b., even in newborns receiving IPR8 without adjuvant. With that said, administration of R848 alone or co-administration of R848 and flagellin results in a significantly more robust response to the subdominant HA stem.

To determine whether the response had reached its peak by this time point, we followed this cohort of NHP out to 4-6 months from their initial vaccination as newborns and assessed plasma titers of stem-specific IgG (Fig. 1f). None of the animals that had received either IPR8 + m229 or IPR8 + flg had stem-specific IgG titers above the limit of detection, despite all animals having detectable antibody to whole PR8 at this time52,53. All animals that received the dual adjuvant and all but one receiving R848 alone retained detectable levels of stem-specific IgG.

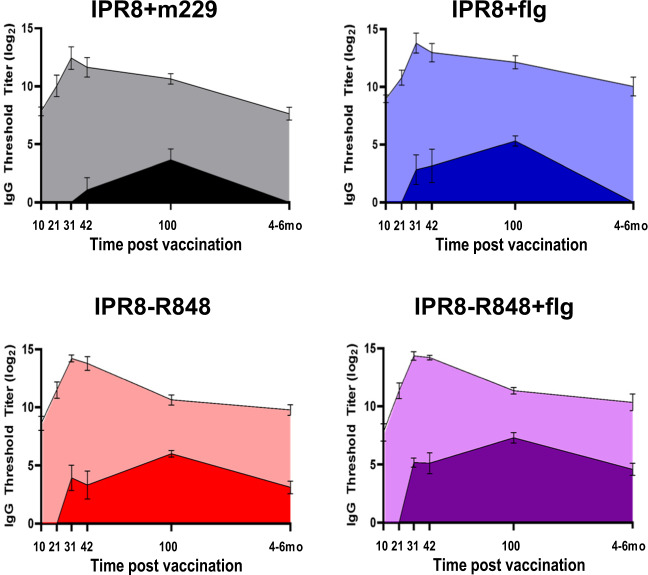

Our previous analyses showing that the TLRa adjuvants increased the magnitude and duration of antibody responses to the PR8 virion compared to vaccination with IPR8 alone52,53 raised the possibility that the increase in stem-specific IgG associated with these adjuvants was simply the result of global improvements in the humoral response rather than a mitigation of immunodominance. To explore this possibility, we compared the IgG response to the HA stem with our previously determined virus-specific IgG titers (Fig. 2)52,53. Although differences in assay methodology prevent quantitation of stem-specific antibody as an absolute proportion of the total response, this facilitates the visualization and comparison of the kinetics of the antibody response to HA stem versus to whole virion. While vaccination with IPR8 + flg, IPR8-R848, or IPR8-R848 + flg all elicited increased IgG titers to whole PR8 at 4-6 months compared to vaccination without adjuvant, the magnitude of the response was similar across adjuvant groups (Fig. 2). This is in contrast to the clear differences in the amount of stem-specific IgG present across the different adjuvant conditions, where the inclusion of R848 or both adjuvants resulted in sustained responses. Interestingly, titers to whole PR8 peaked at day 10 p.b. while levels of stem-specific IgG continued to rise through day 100 p.v. across all groups. This divergence between antibody to PR8 and the stem region suggests that the continued evolution of the antibody response to stem in animals given IPR8-R848 or IPR8-R848 + flg is not merely the result of a global increase in virus-specific Ab, but a specific improvement in the stem-specific response. Further, these data demonstrate differences in the kinetics of the stem-specific versus overall response. Finally, these results suggest that while both TLR5 and TLR7/8 are able to facilitate differentiation of stem-specific B cell clones into antibody secreting cells, TLR7/8 may enhance the ability of these clones to adopt and maintain a LLPC fate.

Fig. 2. Kinetics of the IgG response to whole virus and HA stem.

Average IgG titers over time to the HA stem (dark shading) and PR8 virion (light shading) for animals vaccinated with IPR8 + m229, IPR8 + flg, IPR8-R848, and IPR8-R848 + flg as in Fig. 1. Titers to PR8 have been previously reported for this cohort of animals (1, 2).

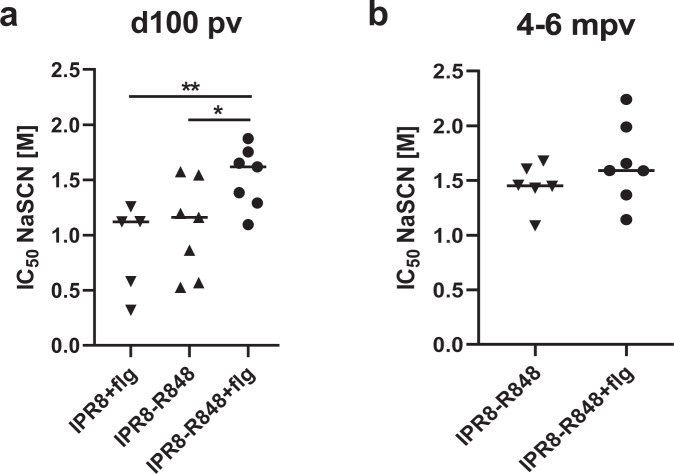

The choice of TLRa adjuvant influences the avidity of stem-specific antibody present at late times following vaccination

Increased antibody avidity, an outcome of somatic hypermutation and selection in the GC60, is associated with improved function in vivo. We postulated that in addition to increasing the total amount of stem-specific Ab at later times following vaccination, the presence of R848 may lead to greater avidity relative to that of flagellin. Ab avidity in non-adjuvanted animals was not assessed due to low titers and sample availability. Sensitivity to dissociation by treatment with chaotropic agents, which correlates with antibody off-rate46,61, was used to assess avidity. Animals assessed were those where stem-specific antibody was present at levels adequate for this analysis. We found no difference at ~d100p.v. in average antibody avidity between groups administered IPR8 with either R848 or flagellin despite significant differences in antibody titer (Fig. 3a). However, animals receiving IPR8-R848 + flg exhibited higher avidity stem-specific IgG than the other groups at this timepoint (Fig. 3a). By the 4–6 month timepoint, antibody avidity was similar in the IPR8-R848 and IPR8-R848 + flg groups, the only animals where antibody remained detectable (Fig. 3b). The similarity in avidity at this timepoint was the result of an increase in the avidity of IgG to stem in the R848 group from d100 to the 4-6 month timepoint (p = 0.03). There was no change in average antibody avidity of the HA stem Ab in animals administered IPR8-R848 + flg over this time (p = 0.22).

Fig. 3. Adjuvant selection regulates avidity maturation of stem-binding IgG.

The average avidity of Ca09 stem-specific IgG at day 100 p.v. (a) and 4-6 months p.v. (b) was calculated by determining the NaSCN concentration that resulted in a 50% reduction in absorbance compared to the untreated sample. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons (a) or unpaired t-test (b). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

The presence of adjuvants is associated with more IL-21 producing cells in the draining LN following challenge of vaccinated newborns

The sustained presence of affinity-matured stem-specific IgG in animals receiving IPR8-R848 with or without flagellin are consistent with a model wherein the adjuvants promote a more effective process of B cell differentiation and/or LLPC production. These processes primarily occur in the GC, where B cell differentiation is regulated by interaction with Tfh cells43,44. Tfh are critical for the differentiation of GC B cells towards a memory or LLPC fate and appear to have a strong influence on Ab responses following IAV vaccination and infection62–64. Additionally, Tfh have been implicated in the mitigation of immunodominance65,66. Given that newborns have reduced Tfh generation and function28,30,34,67, we hypothesized that modulation of Tfh cells by TLRa may account for the observed changes in generation of stem-specific Ab.

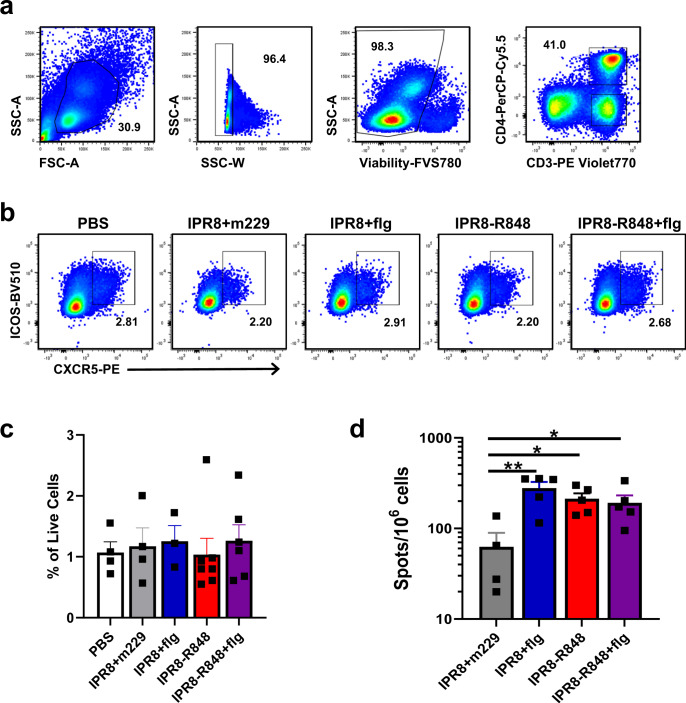

We first evaluated PBMC collected from vaccinated infants at d10 p.b. as the Tfh response would be expected to peak at approximately this time point after antigen encounter68. We chose this timepoint based on analyses in adult humans, but note it is possible that the kinetics of the response differs in young infants. Although the primary role of Tfh cells is in the GC, the number and phenotype of circulating Tfh (cTfh) has been shown to correlate with the GC Tfh response as well as the magnitude of the humoral response62. cTfh cells were identified as cells expressing both CXCR5 and ICOS within the CD3+CD4+ population (Fig. 4a, b). We did not find a difference in cTfh frequency in peripheral blood of infants receiving the various vaccines (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. Inclusion of adjuvant does not result in detectable increases in the total number of Tfh in circulation at d10 p.b., but alters the quantity of influenza virus-specific Tfh in the draining lymph node following challenge.

PBMC collected from newborn NHP at d10 p.b were assessed for the presence of circulating T follicular helper cells by flow cytometry. Three age-matched untreated controls were included in the PBS group to increase sample size. a Gating strategy to identify live CD4+ T cells. Tfh were defined as CXCR5+ ICOS+ cells within this population as shown by representative data in b. c Average frequencies of Tfh as a percentage of live cells in circulation. d A separate group of vaccinated infants was challenged by infection with 1 × 1010 EID50 of PR8 divided equally between the intranasal and intratracheal routes. On d14 p.c., tracheobronchial lymph nodes were isolated. IL-21 production was induced by culture in the presence of pooled peptides from the NA, HA, M1, and NP proteins (0.1 µg/ml for each peptide) for 48 h. IPR8 + m229 n = 4, adjuvanted vaccine groups n = 5. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To gain further insights into these cells, we next sought to measure the number of vaccine-specific cTfh using the highly sensitive ELISPOT approach for quantifying these cells by IL-21 production. We analyzed cells obtained on d21 p.b. due to the lack of sample remaining from the d10p.b. timepoint. Cells were stimulated with pooled peptides from the HA, NA, NP, and M1 proteins of influenza virus as responses to these proteins account for majority of influenza-specific CD4+ T cells in humans69. IL-21 producing cells were below the limit of detection in these assays. Thus, we turned to an alternative approach, quantifying influenza-specific cells following challenge, that we had previously used in assessing IFNγ and IL-4 producing T cells54. In a distinct cohort of vaccinated newborns, newborns similarly vaccinated to those described above were challenged with PR8. Lung draining tracheobronchial lymph nodes were isolated on d14 p.c. and cells cultured in the presence of the pooled peptides for analysis by ELISPOT. The data in Fig. 4d show that the presence of adjuvant results in a significant increase in the number of IL-21 producing cells present in the draining lymph node following challenge. No differences were observed across the adjuvant conditions.

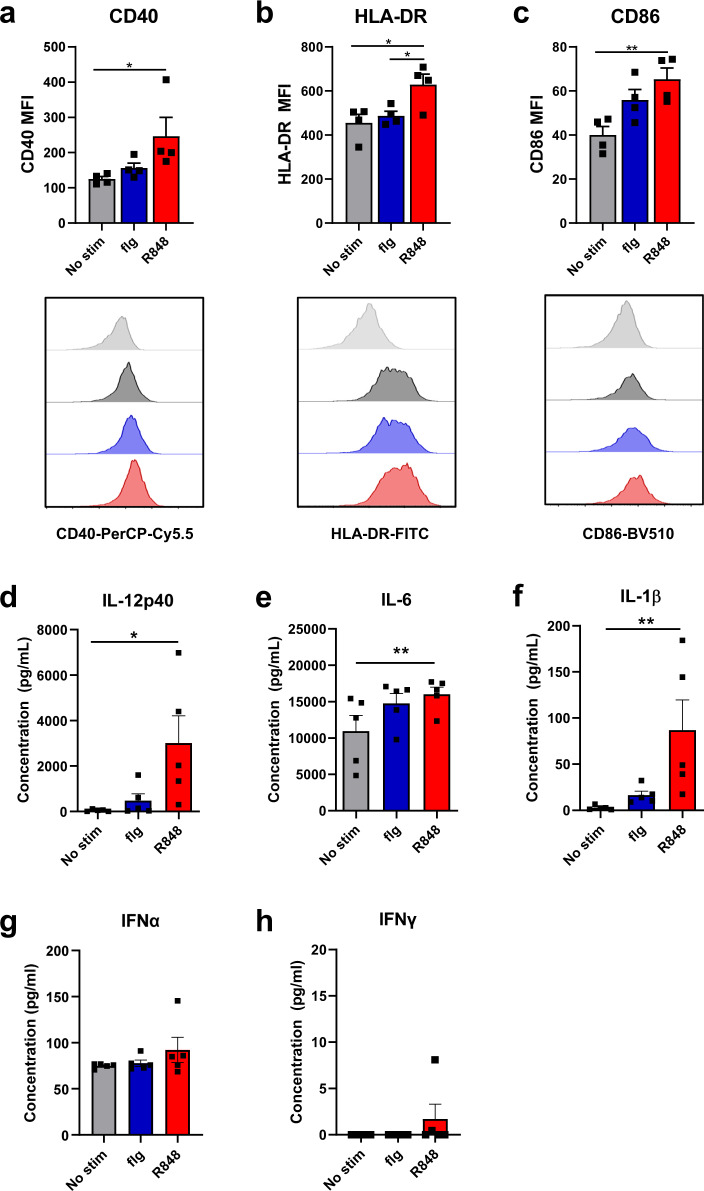

R848 is capable of inducing significant increases in maturation and cytokine production in newborn bone marrow derived DC (BMDC)

Given the important role that DCs play in Tfh development34,70,71, we hypothesized that inclusion of TLRa adjuvants could improve Tfh and B cell function by increasing activation and cytokine production by newborn DC. To test this possibility, dendritic cells differentiated from the bone marrow of newborn AGM were stimulated in vitro with either flagellin or R848. Surface expression of maturation markers and production of cytokines were measured 24 h later. We found that R848 significantly increased the level of CD40, HLA-DR, and CD86 as well as production of multiple cytokines including IL-12p40, IL-1β, and IL-6. However IFNα or IFNγ were not significantly increased (Fig. 5). While flagellin stimulated BMDC showed increases in CD86 and IL-6, these did not reach statistical significance. Although not directly tested here, the capacity of R848 to increase maturation markers and pro-GC cytokine production in BMDC from newborns is consistent with a role for these APC in promoting an immune response that results in the persistence of HA stem-specific antibody in animals receiving an IPR8-R848 conjugated vaccine.

Fig. 5. R848 induces robust activation of newborn BMDC.

DC were differentiated from bone marrow obtained from naïve newborn AGM using hIL-4 and hGM-CSF. On day 6 of culture, cells were stimulated with R848, flagellin, or PBS for 24 h. CD11c+ positive cells were assessed for surface expression of CD40 (a), HLA-DR (b), and CD86 (c). Average median fluorescent intensity is shown with representative histograms below. Supernatants were harvested from flagellin or R848 stimulated BMDC cultures at 24 h. IL-12p40 (d), IFNα (g), and IFNγ (h) levels were assessed by ELISA. IL-6 (e) and IL-1β (f) were quantified by cytokine bead array. Statistical significance was determined using a Friedman test with uncorrected Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

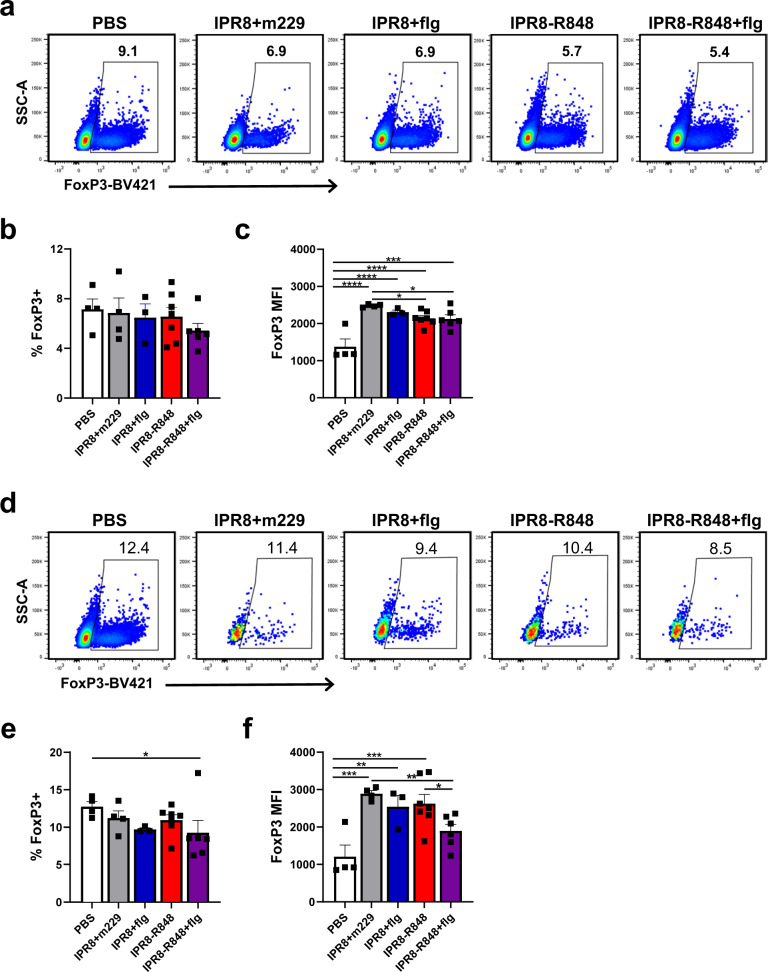

TLRa adjuvants differentially impact Treg and Tfr phenotype

The increased representation of Tregs in newborns compared to their adult counterparts is another factor thought to contribute to diminished immune responses following vaccination early in life36. Tregs appear to play a role in the diversity and immunodominance hierarchy of Ab responses and have been shown to dampen the global Ab response to influenza vaccination38,41,72. To investigate whether the increased stem-specific Ab response seen with TLRa adjuvants is associated with changes in Tregs, we examined this population in PBMC collected from newborn animals at d10 p.b. The vaccine strategy used did not significantly alter the frequency of Tregs (Fig. 6a, b). However, inclusion of R848, regardless of the presence of flagellin, was associated with decreased expression of FoxP3 within the Treg population (Fig. 6c), a phenotype associated with reduced suppressive activity73,74.

Fig. 6. Vaccination in the presence of TLRa adjuvants alters Tregs in peripheral blood 10 days after vaccine boost.

Tregs were quantified by intracellular staining for FoxP3 in peripheral blood collected from newborns at d10 p.b. or age matched naïve controls. a Representative data of FoxP3+ expression in live CD3+CD4+ PBMC. b Average percent of live CD3+CD4+ cells expressing FoxP3 in circulation. c Average median fluorescent intensity of FoxP3 within the CD3+CD4+FoxP3+ population. To assess the representation of Tfr within the T follicular subset, FoxP3+ cells were quantified within the CD3+CD4+CXCR5+ICOS+ population described in Fig. 4b; representative data are shown in d and average frequencies in e. f Average median fluorescent intensity of FoxP3 in the CD3+CD4+CXCR5+ ICOS+FoxP3+ Tfr population. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

We also assessed the presence of T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells (CXCR5+CD4+FoxP3+) in light of recent studies exploring the suppressive activity of these cells in the GC response75,76. While all vaccine conditions trended towards a decreased Tfr frequency within the CXCR5+ICOS+ subpopulation compared to vehicle controls, this effect reached statistical significance only in the IPR8-R848 + flg group (Fig. 6d, e). The level of FoxP3 expression was also diminished in the animals receiving IPR8-R848-flg (Fig. 6f). We also evaluated the level of PD-1 and ICOS on various CD4+ T cell subsets. These markers are reported to increase with Treg activation state77–80. No significant changes were found in the level of these markers across vaccine groups for Treg or Tfr (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). Of note, Tfh and Tfr exhibited higher expression of these markers compared to Tregs (Supplementary Figs. 1, 3).

Discussion

Despite the shortcomings of current influenza vaccines, they remain the most effective way to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza virus infection. Because of this, it is essential that vaccines be able to confer protection to vulnerable populations such as newborns. In addition, protective responses that can work across influenza virus strains would be of particularly high benefit. Achieving these goals requires overcoming both the global reduction in immune responsiveness characteristic of early life as well as the immune system’s seemingly inherent preference for variable over conserved regions of the influenza HA protein. Here, we investigated whether inclusion of the TLR agonists flagellin and R848, either singly or in combination, as adjuvants could mitigate these barriers. We have used a nonhuman primate newborn model to probe these critical questions as this model is inarguably the most translatable to human newborns. As with humans, newborn NHP exhibit increased susceptibility to disease following influenza virus infection81–83. Anatomically the NHP lung is quite similar in structure to the human84 and there is a high degree of similarity between the NHP and humans in the distribution and responsiveness of TLR receptors85. Finally, the prolonged period of infancy and similarities in immune system maturity at birth in NHP provides a model where vaccination, boost, and challenge can be appropriately assessed in an infant.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that both flagellin and R848 can increase the magnitude and as a result persistence of the total antibody response to the influenza virion52–54,86. In the current study we found that the use of R848 or the combination of flagellin and R848 resulted in a significantly increased antibody response to the HA stem early that continued to increase at later times following vaccination. While flagellin provided some early benefit in a subset of newborns, this was not sustained. Changes in stem-specific antibody were associated with modulation of cells that regulate the antibody response and these alterations varied by adjuvant. Although we were unable to quantify antigen-specific cTfh following vaccination, newborns administered vaccines containing R848, flagellin, or their combination had higher numbers of influenza-specific Tfh following challenge compared to infants that were vaccinated in the absence of adjuvant. R848 was more effective at inducing activation and cytokine production in dendritic cells and reduced FoxP3 expression in Tregs. The combination of adjuvants was associated with decreases in both Tfr frequency and FoxP3 expression in Tfh and Tfr.

The ability of adjuvants to drive persistent antibody responses to HA stem in the newborn is a significant finding given the known hurdles associated with generating antibody to these subdominant epitopes and in establishing the LLPC niche in newborns27,59. Inclusion of R848 not only hastened the expansion of IgG to stem, as seen at d10 p.b., but also resulted in significant continued expansion of stem-specific IgG between d21 p.b. and 100 p.v. Although titers of stem-specific IgG declined in general between day 100 p.v. and 4-6 months p.v., the rate of decline was lower in animals receiving IPR8-R848. We speculate that the extended expansion and sustained response may be the result of improved and/or perhaps prolonged selection and differentiation of stem-specific LLPC clones in the GC. Extending the duration of GC activity has been reported to promote increases in neutralizing antibodies to subdominant epitopes in the setting of HIV87,88. Further, prolongation of the GC reaction can promote more extensive affinity maturation89–91.

Interestingly, we observed an increase in average antibody avidity of stem-specific IgG between d100 p.v. and 4-6 months in animals administered IPR8-R848, while antibody avidity in IPR8-R848 + flg group had already reached its maximum by d100 p.v. The continued increase in avidity in the IPR8-R848 vaccinated group resulted in similar avidity in R848 and dual adjuvanted recipients at the 4–6 month timepoint. This finding suggests the combination of flagellin and R848 may accelerate the process of affinity maturation. The continued increase in avidity in IPR8-R848 vaccinated newborns could reflect continued affinity maturation and export of plasma cells. However, the decrease in absolute stem-specific IgG titers between day 100 p.v. and 4-6 months in the IPR8-R848 group is also consistent with a model where the increase in avidity is due to preferential loss of lower-avidity antibody secreting cells over time.

Our data suggest the presence of R848 and/or flagellin results in an improved Tfh response as judged by the number present in the lung draining lymph node following challenge. We appreciate this is an indirect measure as it reflects expansion of memory cells following challenge, but does have benefit as it allows for assessment of IL-21 producing cells in the lymph node as opposed to circulation. Tfh number has been found to correlate with increases in antibody in a number of studies68,92,93. Further, there is evidence that Tfh can promote the generation of broadly reactive antibody in the context of SHIVAD8 infection of rhesus macaques94. Interestingly, the ability to facilitate broadly reactive antibody was dependent on the functional capabilities of elicited Tfh, in this case IL-4 production. The ability of our adjuvanted vaccines to impact Tfh function is an area that merits future study.

DC can exert a variety of regulatory effects on the humoral response including generation of Tfh95,96. While this makes DC an attractive target of vaccine strategies, newborn DC have diminished activation, maturation, and cytokine production in response to stimulation28,97–99. In our studies, we found R848 was superior to flagellin for inducing maturation and cytokine production in newborn BMDCs. R848 was effective in driving production of IL-12, one of the most notable impairments of newborn DC function100–102. This finding is consistent with the reported ability of TLR7/8 agonists to polarize mononuclear cells from human cord blood to a Th1 profile, counteracting the inherent Th2 bias of the neonatal immune system103. R848 can also increase GC formation and high-affinity Ab production in adult mice via DC-mediated B cell activation104. In contrast, TLR5 engagement was only able to promote a Th2-driven antibody response without affinity maturation104. Although the relationship between costimulatory signals on DC and antibody immunodominance has not yet been explored, further investigation is merited as decreased expression of CD80/CD86 on pulmonary DCs has been directly linked to altered immunodominance in CD8 cells in a newborn mouse model of RSV infection105,106.

Tregs provide suppressive feedback on the GC reaction and have been suggested to be a key component in maintaining immunodominance upon subsequent antigen exposures41. Their enhanced suppressive function in newborns as well as their established role in regulating immune responses makes them attractive targets for vaccines. The decrease we see in FoxP3 expression in Tregs supports the capacity of R848 conjugated vaccines to decrease Treg activity given the finding that FoxP3 levels are correlated with suppressive function73,74.

Generally, we did not observe measurable stem-specific antibody until after boost. While this may be the result of low levels of antibody, it is possible that after the priming dose, stem-specific B cell clones preferentially differentiate into memory B cells that rapidly differentiate into extrafollicular ASCs following boost. Indeed, clones with broad reactivity are more frequently found in memory B cell compartments than in plasma cell populations, and the reactivation of these clones provides protection during future encounters with heterologous strains of influenza107–110. The preference for memory differentiation may be attributable to the tendency towards a lower affinity that has been associated with polyreactivity38.

In summary, this study demonstrates that inclusion of TLR7/8 adjuvant R848 in an inactivated IAV vaccine can promote a lasting IgG response to the HA stem, while the TLR5 agonist flagellin produces a response that is diminished in both magnitude and persistence. Regardless of adjuvant, increased IgG to the HA stem appeared to be associated with improved Tfh responses. The presence of R848 was accompanied by Tregs with a dampened suppressive phenotype as well as improved maturation and cytokine production by newborn DC. Finally, our study reveals the unexpected finding that the kinetics of stem-specific Ab response is distinct from the overall Ab response to influenza virus following vaccination. These data provide new insights into the generation of stem-specific Ab and support pursuing development of an IAV vaccine that can effectively provide broad protection in young infants.

Methods

Animals

Newborn AGM used in this study were housed at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine African green monkey Research Colony. Newborns were mother-reared and housed in social groups throughout the course of the experiment except for the influenza virus challenged newborns, which were nursery reared.

Vaccination and sampling

Newborn (4–6 days of age) received vaccines containing formalin-inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8) (H1N1) influenza virus with the following adjuvant conditions: R848 (n = 7), R848 and flagellin (flg) (n = 7), flg (n = 6), or inactive flagellin m229 (n = 5), which served as a non-adjuvanted vaccine. Two animals received PBS as vehicle controls. R848 was directly conjugated to IPR8 while flg and m229 were included in soluble form. Each vaccine contained 45 µg IPR8 administered intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle. Animals were boosted at day 21 post-vaccination (p.v.) with the same adjuvant formulation they received for their priming dose. Inactivation of PR8 was achieved by treating with 0.74% formaldehyde overnight at 37 °C. Virus was dialyzed against PBS and tested to assure the absence of infectivity. For the IPR8-R848 conjugate vaccine, an amine derivative of R848 was linked to SM(PEG)4 by incubation in DMSO for 24 h at 37 °C. R848-SM(PEG)4 was then incubated with influenza virus. Unconjugated R848 was removed by extensive dialysis. This construct was then inactivated by treatment with 0.74% formaldehyde overnight at 37°C, followed by dialysis. Successful conjugation was assessed by differential stimulation of RAW264.7 cells. To produce Salmonella enteritidis flagellin, E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing a pet29a::fliC encoding wild type flagellin or the truncated pet29a::229 encoding only the biologically inactive hypervariable region of flagellin were grown and lysates prepared in 8 M urea. Proteins were purified on Ni-NTA agarose. Endotoxin and nucleic acids were removed using an Acrodisc Mustang Q capsule. Purified proteins were extensively dialyzed against PBS. Peripheral blood was drawn by venipuncture at days 10 and 21 following vaccination and boost as well as at 100 days and 4-6 months after initial vaccination.

Quantification of stem-specific IgG

To measure HA stem-specific antibody, plates were coated overnight with 5 ng of a headless A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) HA stabilized stem construct111. Plates were blocked for 1 h, after which they were washed with PBS + 0.01% Tween-20 (PBST). Plates were incubated for 3 h with serially diluted plasma. Starting dilutions were as stated. Plates were washed, incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-NHP IgG or IgM, and developed using TMB Ultra, after which the reaction was stopped with 0.1 N H2SO4. The absorbance for non-coated wells was subtracted for each animal, and threshold titer was defined as the lowest value that exceeded three times the average OD450 of the uncoated wells. For assessment of avidity, a sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN) dissociation step was included following sample incubation. Plasma was added at a single concentration selected for each animal based on the dilution that yielded 50% of the max OD450 in the ELISA to ensure consistent antibody amounts across varied antibody titers. Following binding, two-fold dilutions of NaSCN starting at 5 M were added to the plate for 15 min. Plates were then washed, incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-IgG, and developed as in the ELISA protocol. The IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

BMDC Culture and stimulation

Bone marrow was collected from newborn AGM (4-6 days old), purified by density gradient separation, and cryopreserved. For experiments, thawed cells incubated with 40 ng/ml human GM-CSF and 40 ng/ml human IL-4. On day 6, cells were stimulated with either 10 nM flagellin or 10 µM R848 for 24 h at 37 °C, after which cells and supernatants were harvested. Cells were stained with CD11c-PE (clone S-HCL-3), CD40-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone 5C3), CD86-BV510 (clone 2331/(FUN-1)), and HLA-DR FITC (clone L243). Samples were acquired on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Cytokine quantification

IL-6 and IL-1β were assessed using a human inflammatory cytokine bead array (BD Biosciences) performed on supernatants collected from BMDC cultures per manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSCalibur; data were analyzed using FCAP Array software. IL-12p40, IFNγ and IFNα were quantified using a human ELISAs verified for NHP cross-reactivity.

T cell flow cytometry

PBMC from newborns d10 p.b. were purified from peripheral blood by density gradient separation, aliquotted and stored in liquid nitrogen. For phenotyping by flow cytometry, cryopreserved cells were thawed in culture media as above and rested at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were stained with Fixable Viability Stain 780 (BD Horizon). Surface staining was performed using the following antibodies: CD3-PE Violet 770 (clone 10D12), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone L200), CD20-AlexaFluor 700 (clone 2H7), CXCR5-PE (clone MU5UBEE), PD-1-PE-Dazzle 594 (clone EH12.2H7), ICOS-BV510 (clone C398.4A). Cells were then washed, fixed and permeabilized with FoxP3/Transcription Factor staining kit, followed by FoxP3-BV421 (clone 206D). Samples were acquired on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 and analyzed with FlowJo software.

T cell ELISPOT

A distinct cohort of vaccinated newborn AGM were challenged with PR8 (1 × 1010 EID50 divided equally between the intranasal (i.n.) and intratracheal (i.t.) routes, 0.25 ml i.t. and 0.25 ml i.n. (0.125 ml per nostril)) on d23-26 following boost. Lung draining tracheobronchial lymph nodes were isolated on d14 post challenge (p.c.) and stored in liquid nitrogen for future study. Thawed cells were cultured in the presence of pooled peptides from the NA (PR8), HA (PR8), M1 (A/California/04/2009), and NP (A/California/04/2009) proteins for 48 h in ELISPOT plates coated with anti-IL-21 antibody (human/NHP IL-21 ELISPOT) kit from MABTECH. Peptides were used at a final concentration of 0.1 µg/ml for each peptide. IL-21 was detected with the antibody provided in the human/NHP IL-21 ELISPOT kit from MABTECH. Plates were developed with BCIP/NBT-plus substrate solution. Plates were read using an ImmunoSpot Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd) and spot counts determined by analysis at ImmunoSpot.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons or Freidman test with uncorrected Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons as indicated. A two-tailed unpaired t test was used when two groups were compared. All titers were log2 transformed prior to statistical analysis.

Study approval

The protocol was approved by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine IACUC and adhered to the U.S. Animal Welfare Act and Regulations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wake Forest Animal Resources Program and the veterinary and technical staff of the Vervet Research Colony for care of animals and assistance with animal procedures. These studies were supported by NIH R01 AI098339 (to M.A.A-M.) and R01 AI146059 (to M.A.A.-M.). The Vervet Research Colony is supported in part by NIH P40 OD010965 (to M.J.J.). M.K. and B.S.G. are supported VRC funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Author contributions

E.A.C designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. B.C.H performed NHP infections and sampling. B.M. performed BMDC experiments. M.K. generated critical reagents for the study. M.A.A-M. designed experiments and wrote the paper. M.K. and B.S.G. provided critical insight to experimental design. All authors contributed to editing of the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary files).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41541-022-00523-8.

References

- 1.Zhu W., Wang C. & Wang B. Z. From variation of influenza viral proteins to vaccine development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 10.3390/ijms18071554 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Henry C, Palm AE, Krammer F, Wilson PC. From original antigenic sin to the universal influenza virus vaccine. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krammer F., Garcia-Sastre A. & Palese P. Is it possible to develop a “universal” influenza virus vaccine? Potential target antigens and critical aspects for a universal influenza vaccine. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10, 10.1101/cshperspect.a028845 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J. Virol. 1993;67:2552–2558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2552-2558.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev. Bio. chem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. The structure and function of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus. Annu Rev. Bio. chem. 1987;56:365–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y. et al. Targeting hemagglutinin: approaches for broad protection against the influenza A virus. Viruses11, 10.3390/v11050405 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lee PS, Wilson IA. Structural characterization of viral epitopes recognized by broadly cross-reactive antibodies. Curr. Top. Microbiol. 2015;386:323–341. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkpatrick E, Qiu X, Wilson PC, Bahl J, Krammer F. The influenza virus hemagglutinin head evolves faster than the stalk domain. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:10432. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28706-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan HX, et al. Subdominance and poor intrinsic immunogenicity limit humoral immunity targeting influenza HA stem. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:850–862. doi: 10.1172/JCI123366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jegaskanda S, et al. Hemagglutinin head-specific responses dominate over stem-specific responses following prime boost with mismatched vaccines. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e129035. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman M. O., Bennink J. R., Yewdell J. W. & Herrin B. R. Lamprey VLRB response to influenza virus supports universal rules of immunogenicity and antigenicity. Elife4, 10.7554/eLife.07467 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Altman MO, Angeletti D, Yewdell JW. Antibody immunodominance: the key to understanding influenza virus antigenic drift. Viral Immunol. 2018;31:142–149. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angeletti D, Yewdell JW. Understanding and manipulating viral immunity: antibody immunodominance enters center stage. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munoz FM. Influenza virus infection in infancy and early childhood. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2003;4:99–104. doi: 10.1016/S1526-0542(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poehling KA, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N. Eng. J. Med. 2006;355:31–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elahi S, et al. Immunosuppressive CD71+ erythroid cells compromise neonatal host defence against infection. Nature. 2013;504:158–162. doi: 10.1038/nature12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudd BD. Neonatal T cells: a reinterpretation. Annu Rev. Immunol. 2020;38:229–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-091319-083608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:553–564. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budeus, B. et al. Human cord blood B cells differ from the adult counterpart by conserved Ig repertoires and accelerated response dynamics. J. Immunol. 10.4049/jimmunol.2100113 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sproul TW, Malapati S, Kim J, Pierce SK. Cutting edge: B cell antigen receptor signaling occurs outside lipid rafts in immature B cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:6020–6023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tasker L, Marshall-Clarke S. Functional responses of human neonatal B lymphocytes to antigen receptor cross-linking and CpG DNA. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003;134:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tasker L, Marshall-Clarke S. Immature B cells from neonatal mice show a selective inability to up-regulate MHC class II expression in response to antigen receptor ligation. Int Immunol. 1991;9:475–484. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaesener S, et al. Decreased production of class-switched antibodies in neonatal B cells is associated with increased expression of miR-181b. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schatorje EJ, Driessen GJ, van Hout RW, van der Burg M, de Vries E. Levels of somatic hypermutations in B cell receptors increase during childhood. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014;178:394–398. doi: 10.1111/cei.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanswal S, Katsenelson N, Selvapandiyan A, Bram RJ, Akkoyunlu M. Deficient TACI expression on B lymphocytes of newborn mice leads to defective Ig secretion in response to BAFF or APRIL. J. Immunol. 2008;181:976–990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pihlgren M, et al. Reduced ability of neonatal and early-life bone marrow stromal cells to support plasmablast survival. J. Immunol. 2006;176:165–172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pihlgren M, et al. Unresponsiveness to lymphoid-mediated signals at the neonatal follicular dendritic cell precursor level contributes to delayed germinal center induction and limitations of neonatal antibody responses to T-dependent antigens. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2824–2832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, et al. IL-6 impairs vaccine responses in neonatal mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3049. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mastelic B, et al. Environmental and T cell-intrinsic factors limit the expansion of neonatal follicular T helper cells but may be circumvented by specific adjuvants. J. Immunol. 2012;189:5764–5772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mastelic Gavillet B, et al. MF59 mediates its B cell adjuvanticity by promoting T follicular helper cells and thus germinal center responses in adult and early life. J. Immunol. 2015;194:4836–4845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vono M, et al. Overcoming the neonatal limitations of inducing germinal centers through liposome-based adjuvants including C-type lectin agonists trehalose dibehenate or curdlan. Front Immunol. 2018;9:381. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munguía-Fuentes R, et al. Immunization of newborn mice accelerates the architectural maturation of lymph nodes, but AID-dependent IgG responses are still delayed compared to the adult. Front Immunol. 2017;8:13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mastelic-Gavillet, B. et al. Neonatal T follicular helper cells are lodged in a pre-T follicular helper stage favoring innate over adaptive germinal center responses. Front. Immunol.10, 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01845 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hayakawa S, Ohno N, Okada S, Kobayashi M. Significant augmentation of regulatory T cell numbers occurs during the early neonatal period. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017;190:268–279. doi: 10.1111/cei.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holbrook BC, Alexander-Miller MA. Higher frequency and increased expresssion of molecules associated with suppression on T regulatory cells from newborn compared with adult nonhuman primates. J. Immunol. 2020;205:2128–2136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2000461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angeletti D, et al. Defining B cell immunodominance to viruses. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:456–463. doi: 10.1038/ni.3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angeletti D, et al. Outflanking immunodominance to target subdominant broadly neutralizing epitopes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:13474–13479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816300116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva M, et al. Targeted elimination of immunodominant B cells drives the germinal center reaction toward subdominant epitopes. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3672–3680. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JH, Davis WG, Sambhara S, Jacob J. Strategies to alleviate original antigenic sin responses to influenza viruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13751–13756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912458109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ndifon W. A simple mechanistic explanation for original antigenic sin and its alleviation by adjuvants. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2015;12:20150627. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woodruff MC, Kim EH, Luo W, Pulendran B. B cell competition for restricted T cell help suppresses rare-epitope responses. Cell Rep. 2018;25:321–327.e323. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lightman S. M., Utley A. & Lee K. P. Survival of long-lived plasma cells (LLPC): piecing together the puzzle. Front. Immunol.10, 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00965 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhang Y, et al. Plasma cell output from germinal centers is regulated by signals from Tfh and stromal cells. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1227–1243. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khurana S, et al. Heterologous prime-boost vaccination with MF59-adjuvanted H5 vaccines promotes antibody affinity maturation towards the hemagglutinin HA1 domain and broad H5N1 cross-clade neutralization. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khurana S, et al. Vaccines with MF59 adjuvant expand the antibody repertoire to target protective sites of pandemic avian H5N1 influenza virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:15ra15. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khurana S, et al. AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine promotes antibody diversity and affinity maturation, NAI titers, cross-clade H5N1 neutralization, but not H1N1 cross-subtype neutralization. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:40. doi: 10.1038/s41541-018-0076-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khurana S, et al. MF59 adjuvant enhances diversity and affinity of antibody-mediated immune response to pandemic influenza vaccines. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:85ra48. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmitz N, et al. Universal vaccine against influenza virus: linking TLR signaling to anti-viral protection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012;42:863–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto T, et al. A unique nanoparticulate TLR9 agonist enables a HA split vaccine to confer FcγR-mediated protection against heterologous lethal influenza virus infection. Int Immunol. 2019;31:81–90. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxy069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holbrook BC, et al. An R848 adjuvanted influenza vaccine promotes early activation of B cells in the draining lymph nodes of non-human primate neonates. Immunology. 2018;153:357–367. doi: 10.1111/imm.12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holbrook BC, D’Agostino RB, Jr., Parks GD, Alexander-Miller MA. Adjuvanting an inactivated influenza vaccine with flagellin improves the function and quantity of the long-term antibody response in a nonhuman primate neonate model. Vaccine. 2016;34:4712–4717. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holbrook BC, et al. Adjuvanting an inactivated influenza vaccine with conjugated R848 improves the level of antibody present at 6months in a nonhuman primate neonate model. Vaccine. 2017;35:6137–6142. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holbrook BC, et al. A novel R848-conjugated inactivated influenza virus vaccine is efficacious and safe in a neonate nonhuman primate model. J. Immunol. 2016;197:555–564. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clemens E, et al. Influenza-infected newborn and adult monkeys exhibit a strong primary antibody response to hemagglutinin stem. JCI Insight. 2020;5:135449. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.135449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clemens, E. A. et al. An R848 conjugated influenza virus vaccine elicits robust IgG to hemagglutinin stem in a newborn nonhuman primate model. J. Infect. Dis.10.1093/infdis/jiaa728 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Tarantal AF, Noctor SC, Hartigan-O’Connor DJ. Nonhuman primates in translational research. Annu Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2022;10:441–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-021419-083813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Honko AN, Mizel SB. Mucosal administration of flagellin induces innate immunity in the mouse lung. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:6676–6679. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6676-6679.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belnoue E, et al. APRIL is critical for plasmablast survival in the bone marrow and poorly expressed by early-life bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2008;111:2755–2764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal Centers. Annu Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:429–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klasse PJ. How to assess the binding strength of antibodies elicited by vaccination against HIV and other viruses. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2016;15:295–311. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1128831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koutsakos M, Nguyen THO, Kedzierska K. With a little help from T follicular helper friends: Humoral immunity to influenza vaccination. J. Immunol. 2019;202:360–367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koutsakos M. et al. Circulating TFH cells, serological memory, and tissue compartmentalization shape human influenza-specific B cell immunity. Sci. Transl. Med.10, 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan8405 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Aljurayyan, A. et al. Activation and induction of antigen-specific T follicular helper cells play a critical role in live-attenuated influenza vaccine-induced human mucosal anti-influenza antibody response. J. Virol. 92, 10.1128/JVI.00114-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Kubo M, Miyauchi K. Breadth of antibody responses during influenza virus infection and vaccination. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Havenar-Daughton C, Lee JH, Crotty S. Tfh cells and HIV bnAbs, an immunodominance model of the HIV neutralizing antibody generation problem. Immunol. Rev. 2017;275:49–61. doi: 10.1111/imr.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Debock I, et al. Neonatal follicular Th cell responses are impaired and modulated by IL-4. J. Immunol. 2013;191:1231–1239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bentebibel SE, et al. Induction of ICOS+CXCR3+CXCR5+ TH cells correlates with antibody responses to influenza vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:176ra132. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sant AJ, DiPiazza AT, Nayak JL, Rattan A, Richards KA. CD4 T cells in protection from influenza virus: Viral antigen specificity and functional potential. Immunol. Rev. 2018;284:91–105. doi: 10.1111/imr.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cucak H, Yrlid U, Reizis B, Kalinke U, Johansson-Lindbom B. Type I interferon signaling in dendritic cells stimulates the development of lymph-node-resident T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2009;31:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shin C, et al. CD8α− dendritic cells induce antigen-specific T follicular helper cells generating efficient humoral immune responses. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1929–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang SM, Tsai MH, Lei HY, Wang JR, Liu CC. The regulatory T cells in anti-influenza antibody response post influenza vaccination. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:1243–1249. doi: 10.4161/hv.21117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chauhan SK, Saban DR, Lee HK, Dana R. Levels of Foxp3 in regulatory T cells reflect their functional status in transplantation. J. Immunol. 2009;182:148–153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiruppathi M, et al. Impaired regulatory function in circulating CD4+CD25highCD127low/− T cells in patients with myasthenia gravis. Clin. Immunol. 2012;145:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stebegg M, et al. Regulation of the germinal center response. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2469. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miles B, Connick E. Control of the germinal center by follicular regulatory T cells during infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2704. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen Q, et al. ICOS signal facilitates Foxp3 transcription to favor suppressive function of regulatory T cells. Int J. Med Sci. 2018;15:666–673. doi: 10.7150/ijms.23940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zheng J, et al. ICOS regulates the generation and function of human CD4+ Treg in a CTLA-4 dependent manner. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Busse M, Krech M, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Hennig C, Hansen G. ICOS mediates the generation and function of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells conveying respiratory tolerance. J. Immunol. 2012;189:1975–1982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gianchecchi E, Fierabracci A. Inhibitory receptors and pathways of lymphocytes: The role of PD-1 in Treg development and their involvement in autoimmunity onset and cancer progression. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2374–2374. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collie MH, Sweet C, Smith H. Infection of neonatal and adult mice with non-passaged influenza viruses. Brief. Rep. Arch. Virol. 1980;65:77–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01340544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holbrook BC, et al. Nonhuman primate infants have an impaired respiratory but not systemic IgG antibody response following influenza virus infection. Virology. 2015;476:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lines JL, Hoskins S, Hollifield M, Cauley LS, Garvy BA. The migration of T cells in response to influenza virus is altered in neonatal mice. J. Immunol. 2010;185:2980–2988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Irvin CG, Bates JH. Measuring the lung function in the mouse: the challenge of size. Respir. Res. 2003;4:4. doi: 10.1186/rr199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ketloy C, et al. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors on dendritic cells and other antigen presenting cells from non-human primates. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008;125:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim JR, et al. Inclusion of flagellin during vaccination against influenza enhances recall responses in nonhuman primate neonates. J. Virol. 2015;89:7291–7303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00549-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cirelli KM, et al. Slow delivery immunization enhances HIV neutralizing antibody and germinal center responses via modulation of immunodominance. Cell. 2019;177:1153–1171.e1128. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klein F, et al. Somatic mutations of the immunoglobulin framework are generally required for broad and potent HIV-1 neutralization. Cell. 2013;153:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weisel FJ, Zuccarino-Catania GV, Chikina M, Shlomchik MJ. A temporal switch in the germinal center determines differential output of memory B and plasma cells. Immunity. 2016;44:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kräutler NJ, et al. Differentiation of germinal center B cells into plasma cells is initiated by high-affinity antigen and completed by Tfh cells. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:1259–1267. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Phan TG, et al. High affinity germinal center B cells are actively selected into the plasma cell compartment. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2419–2424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bentebibel SE, et al. ICOS+PD-1+CXCR3+ T follicular helper cells contribute to the generation of high-avidity antibodies following influenza vaccination. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26494. doi: 10.1038/srep26494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hill DL, et al. The adjuvant GLA-SE promotes human Tfh cell expansion and emergence of public TCRβ clonotypes. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:1857–1873. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yamamoto T, et al. Quality and quantity of TFH cells are critical for broad antibody development in SHIVAD8 infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:298ra120. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Krishnaswamy J. K., Alsén S., Yrlid U., Eisenbarth S. C. & Williams, A. Determination of T follicular helper cell fate by dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 9, 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02169 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Schmitt N, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Belnoue E, et al. Functional limitations of plasmacytoid dendritic cells limit type I interferon, T cell responses and virus control in early life. PLoS One. 2013;8:e85302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Papaioannou NE, Pasztoi M, Schraml BU. Understanding the functional properties of neonatal dendritic cells: a doorway to enhance vaccine effectiveness. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:3123. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Velilla PA, Rugeles MT, Chougnet CA. Defective antigen-presenting cell function in human neonates. Clin. Immunol. 2006;121:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee HH, et al. Delayed maturation of an IL-12-producing dendritic cell subset explains the early Th2 bias in neonatal immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2269–2280. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goriely S, et al. Deficient IL-12(p35) gene expression by dendritic cells derived from neonatal monocytes. J. Immunol. 2001;166:2141–2146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Langrish CL, Buddle JC, Thrasher AJ, Goldblatt D. Neonatal dendritic cells are intrinsically biased against Th-1 immune responses. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2002;128:118–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Surendran N, Simmons A, Pichichero ME. TLR agonist combinations that stimulate Th type I polarizing responses from human neonates. Innate Immun. 2018;24:240–251. doi: 10.1177/1753425918771178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chappell CP, Draves KE, Giltiay NV, Clark EA. Extrafollicular B cell activation by marginal zone dendritic cells drives T cell-dependent antibody responses. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1825–1840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ruckwardt TJ, Malloy AM, Morabito KM, Graham BS. Quantitative and qualitative deficits in neonatal lung-migratory dendritic cells impact the generation of the CD8+ T cell response. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003934. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Malloy AM, Ruckwardt TJ, Morabito KM, Lau-Kilby AW, Graham BS. Pulmonary dendritic cell subsets shape the respiratory syncytial virus-specific CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchy in neonates. J. Immunol. 2017;198:394–403. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McCarthy KR, et al. Memory B cells that cross-react with group 1 and group 2 influenza A viruses are abundant in adult human repertoires. Immunity. 2018;48:174–184.e179. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guthmiller J. J. et al. Polyreactive broadly neutralizing B cells are selected to provide defense against pandemic threat influenza viruses. Immunity, 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.005 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Tesini B. L. et al. Broad hemagglutinin-specific memory B cell expansion by seasonal influenza virus infection reflects early-life imprinting and adaptation to the infecting virus. J Virol93, 10.1128/jvi.00169-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Andrews SF, et al. Activation dynamics and immunoglobulin evolution of pre-existing and newly generated human memory B cell responses to influenza hemagglutinin. Immunity. 2019;51:398–410.e395. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yassine HM, et al. Use of hemagglutinin stem probes demonstrate prevalence of broadly reactive Group 1 influenza antibodies in human sera. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8628. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary files).