Abstract

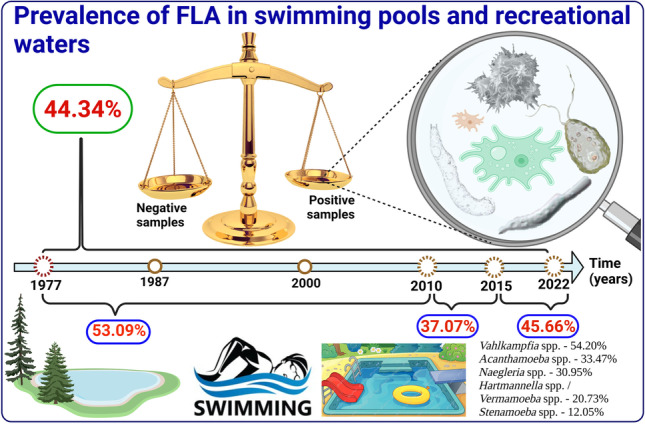

Free-living amoebae (FLA) are cosmopolitan microorganisms known to be pathogenic to humans who often have a history of contact with contaminated water. Swimming pools and recreational waters are among the environments where the greatest human exposure to FLA occurs. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters, through a systematic review and meta-analysis that included studies published between 1977 and 2022. A total of 106 studies were included and an overall prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters of 44.34% (95% CI = 38.57–50.18) was found. Considering the studies published up to 2010 (1977–2010), between 2010 and 2015, and those published after 2010 (> 2010–2022), the prevalence was 53.09% (95% CI = 43.33–62.73) and 37.07% (95% CI = 28.87–45.66) and 45.40% (95% CI = 35.48–55.51), respectively. The highest prevalence was found in the American continent (63.99%), in Mexico (98.35%), and in indoor hot swimming pools (52.27%). The prevalence varied with the variation of FLA detection methods, morphology (57.21%), PCR (25.78%), and simultaneously morphology and PCR (43.16%). The global prevalence by genera was Vahlkampfia spp. (54.20%), Acanthamoeba spp. (33.47%), Naegleria spp. (30.95%), Hartmannella spp./Vermamoeba spp. (20.73%), Stenamoeba spp. (12.05%), and Vannella spp. (10.75%). There is considerable risk of FLA infection in swimming pools and recreational waters. Recreational water safety needs to be routinely monitored and, in case of risk, locations need to be identified with warning signs and users need to be educated. Swimming pools and artificial recreational water should be properly disinfected. Photolysis of NaOCl or NaCl in water by UV-C radiation is a promising alternative to disinfect swimming pools and artificial recreational waters.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00436-022-07631-3.

Keywords: Free-living amoebae, Risk of infection, Swimming pool, Recreational waters

Introduction

Free-living amoebae (FLA) are cosmopolitan and ubiquitous microorganisms widely distributed in the environment and can be opportunistic and/or pathogenic (Visvesvara et al. 2007; Bellini et al. 2022). They have been isolated from many natural and anthropogenic environmental matrices, including plants, soil, air conditioning dust, bottled mineral water, drinking water treatment and distribution system, and cooling towers (Landell et al. 2013; Maschio et al. 2015; Javanmard et al. 2017; Soares et al. 2017; Wopereis et al. 2020; Pazoki et al. 2020). They have also been isolated from contact lenses, swimming pools, and other recreational waters (Fabres et al. 2016; Bunsuwansakul et al. 2019; Santos et al. 2021; Fabros et al. 2021).

Among its representatives with importance for human health, the genera Acanthamoeba, Naegleria, and Balamuthia stand out. Acanthamoeba spp. and its abundance in water bodies seem to be favored by higher temperatures (Kang et al 2020). These protozoa can cause illnesses in healthy people, such as Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) which primarily affects contact lens wearers, usually due to lens wear while swimming or improper lens cleaning (Dos Santos et al. 2018). In immunosuppressed individuals, it can cause granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE), which can be fatal (Visvesvara et al. 2007; Sarink et al. 2022). Acanthamoeba spp. have also been reported to cause skin infections (Murakawa et al. 1995; Paltiel et al. 2004). In addition, it was isolated from 26% (17/63) of critically ill patient urine samples (Santos et al. 2009); similarly, Acanthamoeba (T4) was isolated from 22% (11/50) of urine samples collected from patients with recurrent urinary tract infection (Saberi et al. 2021).

Naegleria fowleri is known as a “brain-eating amoeba” and primarily affects healthy young people using recreational waters, causing primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) (Fowler and Carter, 1965). PAM is a serious and usually fatal disease if adequate treatment is not initiated at the onset of symptoms (Król-Turmińska and Olender 2017). The rapid deterioration in the health status of patients affected by PAM, combined with the ease of being confused with bacterial meningoencephalitis (since the symptoms are similar), as well as erratic or late diagnosis, contributes to a high prevalence of deaths (> 97%) (Capewell et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2016). Balamuthia mandrillaris and Sappinia pedatta also cause encephalitis (Gelman et al. 2001; Visvesvara et al. 2007; Cope et al. 2019); however, there are no reports of the isolation of S. diploidea/pedatta from swimming pools and recreational waters.

The FLA essentially have three forms of life, namely, the trophozoite form (with or without flagellum) and the flagellated form which are the active forms of the protozoan, in which it may feed, reproduce, and express pathogenicity, and the form of cysts (which is the form of environmental resistance). Cysts have a double-layer wall made essentially of cellulose (Garajová et al. 2019) that protects the protozoan against unfavorable conditions (e.g., food shortages, dissection, extreme pH, and temperatures) or antimicrobial agents (e.g., NaCl, chlorine, drugs, UV, heat) (Aksozek et al. 2002; Thomas et al. 2008; Chaúque and Rott 2021a, b; Chaúque et al. 2021). FLA are considered the “Trojan Horse” of the microbial world, as phylogenetically diverse microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and viruses survive and multiply within them; these microorganisms are called amoeba-resistant microorganisms (ARM) (Greub and Raoult 2004; Scheid 2014; Delafont et al. 2016; Hubert et al. 2021; Rayamajhee et al. 2021). A wide range of pathogens of public health importance have been described as being ARM, including Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium leprae, Pseudomonas spp., Candida auris, and various viruses (Maschio et al. 2015; Staggemeier et al. 2016; Balczun and Scheid 2017; Turankar et al. 2019; Nisar et al. 2020; Hubert et al. 2021). The participation of FLA in the environmental persistence of severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has also been proposed (Chaúque et al. 2022; Dey et al 2022). All these aspects that characterize the profile of FLA constitute the main attributes that determine the great importance of these protozoa for human health and the environment.

Although increasingly prevalent, diseases caused by FLA remain rare; however, the presence of these protozoa, especially in the aquatic environment, is well documented (Milanez et al. 2022; Stapleton 2021; Saburi et al. 2017; Caumo et al. 2009). The presence of FLA in swimming pools and other recreational waters is of concern, as they can be pathogenic or opportunistic and/or lead to the persistence of non-amoebic pathogens in the water, including waters treated with chlorine-based disinfectants (Siddiqui and Khan 2014; Kiss et al. 2014; Dey et al. 2021). It was determined that the prevalence of Naegleria spp. in different water sources around the world (considering data from 35 countries) was 26.42%, in recreational water it was 21.27% (10.80–34.11), and in swimming pools was 44.80% (16.19–75.45) (Saberi et al. 2020); however, the global prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters remains to be determined. The present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters worldwide.

Methods

Article search strategy

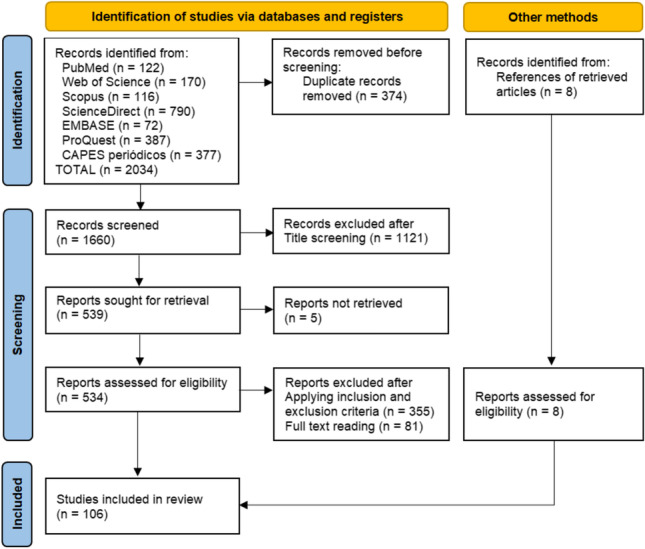

The present study, which aimed to determine the prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters, was planned and carried out based on the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al. 2021) (Fig. 1). The search for scientific articles was performed in different databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, EMBASE, ProQuest, and CAPES periódicos, between July 4 and 9, 2022. In these databases, articles were retrieved using a combination of the following search terms combined with appropriate Boolean operators: “Free-living amoeba,” “swimming pool,” “recreational water,” “prevalence,” “epidemiology,” and “hot springs.” The references of the selected articles were examined in search of some interesting literature. The search for articles in the database was performed by B.J.M.C, and the accuracy of the searches was verified by D.L.S.

Fig. 1.

Details of the article retrieval and selection steps based on PRISMA 2020

Selection and exclusion criteria

The screening focused essentially on the title and then on the abstract of the articles. All retrieved articles written in English (reporting primary data), with accessible full text, dealing with the presence of FLA in swimming pools and human recreation waters were selected. Studies based on natural surface waters that do not clearly state that the samples were collected in places where human recreational activities certainly take place were not selected. Studies whose data were insufficient, unclear, or duplicated were excluded. Case studies that do not report the prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and human recreation waters were also excluded.

Data analysis procedure

Data were independently extracted and verified by two authors (B.J.M.C and D.L.S); data verification was performed three times. Data extracted from all articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the calculation of the global prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters. To calculate the prevalence of each FLA genera, only data extracted from articles that included molecular methods for the identification of FLA were used. Data analysis was performed by two authors (D.A and B.J.M.C) using Stata software (version 14; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) and GraphPad prism 8.02. A random-effects model meta-analysis was performed to estimate the combined and weighted prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters, using a 95% confidence interval, and the results are visualized using a forest plot. Cochran’s Q test (chi-square) and the Higgins I2 statistic were used to calculate the heterogeneity index among the selected studies. I2 values < 25%, 25%–50%, and > 50% meant low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The Egger’s test was used to assess the significance of publication bias among the selected studies; P < 0.001 was considered significant.

Results

From the total of 2034 documents returned by the databases accessed, using the search strategy and inclusion criteria described above, 106 articles were selected (Table 1). These studies are distributed in a total of 30 countries, namely Iran (33), Taiwan (12), Egypt (8), Malaysia (6), Brazil (4), Italy (4), Turkey (4), USA (4), Mexico (3), Saudi Arabia (3), China (2), France (2), Philippines (2), Spain (2), and Thailand (2). One study was included from each of the following countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Cape Verde, Chile, Finland, Germany, Hungary, India, Jamaica, Japan, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland. Among the studies, 74.52% (79/106) used or included molecular methods to identify FLA, while 25.47% (27/106) used only morphological methods.

Table 1.

Description of included studies reporting the prevalence of live amoebae in swimming pools and recreational waters

| References | Country | Sample source (total) | Analyzed samples | Positive samples | Methods | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown And Cursons (1977) | Norway | Swimming area | 50 | 34 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp., Naegleria fowleri, and Naegleria gruberi |

| Lyons and Kapur (1977) | USA | Swimming pool | 30 | 27 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and/or Hartmannella spp. |

| Pernin and Riany (1978) | France | Swimming pool (9) | 44 | 39 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp., Hartmannella spp., and Naegleria spp. |

| De Jonckheere (1979) | Belgium | Swimming pool | 16 | 13 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Janitschke et al. (1980) | Germany | Swimming pool | 14 | 10 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Scaglia et al. 1983 | Italy | Thermal pool and mud basin spa | 30 | 7 | Morphology, fluorescent-antibody technique | N. australiensis |

| Gogate and Deodhar (1985) | India | Public swimming pool | 12 | 1 | Morphology | N. fowleri |

| Scaglia et al. 1987 | Italy | Thermal bath and mud basin (34) | 51 | 34 | Morphology, pathogenicity test | Naegleria spp., Acanthamoeba spp., Vahlkampfia spp., and Hartmannella spp. |

| Hamadto et al. 1993 | Egypt | Swimming pool (16) | 16 | 12 | Morphology, pathogenicity test | Naegleria spp. and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Penas-Ares et al. 1994 | Spain | Thermal spa water (12) | 12 | 8 | Morphology | Vahlkampfia longicauda, Vahlkampfia salina, Vahlkampia baltica, Vahlkampfia sp., A. polyphaga, Acanthamoeba lenticulata, Naegleria sp., Lingulamoeba sp., Paramoeba aesturina, and Flabellula sp. |

| Vesaluoma et al. (1995) | Finland | Public swimming pool and whirlpool (21) | 34 | 14 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp., Vexillifera spp., Flabellula spp., Hartmannella spp., and Rugipes spp. |

| Munoz et al. 2003 | Chile | Swimming pool | 8 | 5 | Morphology, PCR | H. vermiformes, Vanella spp., Naegleria spp., and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Sheehan et al. 2003 | USA | Hot spring (22) | 22 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | N. australiensis, N. dobsoni, N. americana, N.pagei, N. polaris, and N. fultoni |

| Izumiyama et al. 2003 | Japan | Whirlpool bath and hot spring spa (251) | 549 | 197 | Morphology, PCR | N. fowleri, N. lovaniensis, and N. australiensis |

| Górnik and Kuźna-Grygiel (2004) | Poland | Public swimming pools (13) | 72 | 42 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Tsvetkova et al. 2004 | Bulgaria | Swimming pool (6) | 31 | 15 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Hartmannella spp. |

| Lekkla et al. (2005) | Thailand | Hot spring (13) | 68 | 26 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Sukthana et al. 2005 | Thailand | Hot spring | 57 | 15 | Morphology | Naegleria spp. and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Rezaeian et al 2008 | Iran | Swimming pool | 2 | 2 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Caumo et al. (2009) | Brazil | Swimming pool | 65 | 13 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Gianinazzi et al. (2009) | Switzerland | Indoor hot swimming pool | 1 | 1 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba lenticulata |

| Hsu et al. (2009a, b) | Taiwan | Recreational hot spring | 55 | 9 | PCR | Acanthamoeba griffini and Acanthamoeba jacobsi |

| Hsu et al. (2009a) | Taiwan | Mud recreation area water | 34 | 20 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp., Hartmannella spp., and Naegleria spp. |

| Gianinazzi et al. (2010) | Sweden | Hot springs (4) | 31 | 9 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba healyi, Stenoamoeba sp., Hartmannella vermiformis, and Echinamoeba exundans |

| Huang and Hsu (2010a, b) | Taiwan | Hot spring and waste water in recreation area | 52 | 11 | PCR | Acanthamoeba T1, Acanthamoeba T2, Acanthamoeba T3, Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T5, Acanthamoeba T6, and Acanthamoeba T15 |

| Huang and Hsu (2010a) | Taiwan | Hot spring and hot spring facilities | 106 | 15 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria lovaniensis, Naegleria australiensis, Naegleria clarki, Naegleria americana, and Naegleria pagei |

| Init et al. (2010) | Malaysia | Public swimming pool (14) | 14 | 14 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Lares-Villa et al. 2010 | Mexico | Natural recreational water (2) | 24 | 24 | PCR | Thermophilic amoebae, thermophilic Naegleria spp., and N. fowleri |

| Badirzadeh et al. (2011) | Iran | Recreational hot spring | 28 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Vahlkampfiid and Acanthamoeba castellanii T4 |

| Huang and Hsu (2011) | Taiwan | Recreational water | 107 | 19 | PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Ithoi et al. (2011) | Malaysia | Recreational pool, lake, and stream | 33 | 33 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Nazar et al. 2011 | Iran | Water in recreation area | 50 | 16 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 and Acanthamoeba spp. T5 |

| Alves et al. (2012) | Brazil | Public swimming pool (7) | 7 | 7 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Kao et al. (2012a, b, c) | Taiwan | Recreation and drinking water source (2) | 211 | 13 | PCR | Naegleria philippinensis, N. clarki, Naegleria gálica, N. americana, N. australiensis, Naegleria dobsoni, N. gruberi, and Naegleria schusteri |

| Kao et al. (2012a) | Taiwan | Recreational hot spring (4) | 60 | 9 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T15, Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T2, and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Kao et al. (2012b) | Taiwan | Hot spring | 60 | 26 | Morphology, PCR | N. australiensis, N. lovaniensis, Naegleria mexicana, and N. gruberi |

| Nazar et al. (2012) | Iran | Recreational water (22) | 50 | 8 | Morphology, PCR | Hartmannella vermiformis and Vannella persistens |

| Niyyati et al. (2012) | Iran | River recreation area (10) | 55 | 15 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. (T4 and T15) and Naegleria spp. (N. pagei, N. clarki, and Naegleria fultoni) |

| Rahdar et al. 2012 | Iran | Swimming pool (4) | 4 | 2 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4 |

| Solgi et al. (2012a, b) | Iran | Hot spring | 30 | 8 | Morphology, PCR | Hartmannella vermiformis and Naegleria (N. carteri and Naegleria spp.) |

| Solgi et al. (2012a) | Iran | Therapeutic hot spring | 60 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4 and T3 |

| Kao et al. 2013a, b | China | Thermal spring water | 48 | 4 | PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Kao et al. 2013a | China | Thermal spring | 48 | 5 | PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Moussa et al. (2013) | France | Recreational geothermal waters (6) | 73 | 35 | Morphology, PCR | N. fowleri and N. lovaniensis |

| Tung et al. (2013) | Taiwan | Hot spring (1) | 25 | 13 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. (N. fowleri) and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Al-Herrawy et al. (2014) | Egypt | Swimming pool (10) | 120 | 59 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Ji et al. (2014) | Taiwan | Hot spring | 61 | 29 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Ji et al. (2014) | Taiwan | Hot spring | 61 | 17 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Ji et al. (2014) | Taiwan | Hot spring | 61 | 11 | Morphology, PCR | Vermamoeba vermiformis |

| Kiss et al. (2014) | Hungary | Swimming pool (20) | 164 | 68 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Onichandran et al. 2014 | Philippines | Recreational river (4) | 23 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Sifuentes et al. (2014) | USA | Recreational water (33) | 103 | 18 | PCR | Thermophilic amoebae and N. fowleri |

| Behniafar et al. (2015) | Iran | Recreational water and hot spring | 40 | 7 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Evyapan et al. (2015) | Turkey | Swimming pool and hot spring | 50 | 21 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp., Acanthamoeba griffini T3, Acanthamoeba castellanii T4, and A. jacobsi T15 |

| Niyyati et al. (2015a, b) | Iran | Recreational water (lakes, pools, and streams) | 60 | 9 | Morphology, PCR | N. australiensis and N. pagei |

| Niyyati et al. (2015a) | Iran | Recreational water | 50 | 15 | Morphology, PCR | A. castellanii T4 |

| Todd et al. (2015) | Jamaica | Recreational water | 83 | 42 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T5, Acanthamoeba T10, and Acanthamoeba T11 |

| Al-Herrawy et al. (2016) | Egypt | Swimming pool (1) | 48 | 30 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp., Naegleria spp., and Hartmannella |

| Armand et al. (2016) | Iran | Swimming pool | 17 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Vermamoeba spp. and Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Azlan et al. 2016 | Malaysia | Recreational lake | 7 | 7 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Fabres et al. (2016) | Brazil | Hot tubs and thermal pool | 72 | 20 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T3, Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T5, and Acanthamoeba T15 |

| Latifi et al. (2016) | Iran | Hot spring | 66 | 2 | Morphology, PCR | Balamuthia mandrillaris |

| Niyyati et al. (2016a, b) | Iran | Geothermal water source | 40 | 20 | PCR | Acanthamoeba T4 and T2 |

| Niyyati et al. (2016a) | Iran | Recreational water | 25 | 25 | Morphology | Vahlkampfidae spp., Acanthamoeba spp., Thecamoeba spp., and Miniamoebae spp. |

| Al-Herrawy et al. (2017) | Egypt | Swimming pool (2) | 144 | 37 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Di Filippo et al. (2017) | Italy | Geothermal spring | 36 | 26 | Morphology, PCR | N. australiensis, Naegleria itálica, N. lovaniensis, and Naegleria spp. |

| Javanmard et al. (2017) | Iran | Swimming pool and hot spring | 33 | 6 | Morphology, PCR | N. pagei and N. gruberi |

| Latifi et al. (2017) | Iran | Recreation hot spring | 22 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. (N. australiensis, N. americana, N. dobsoni, N. pagei, N. polaris, and N. fultoni) |

| Mafi et al. (2017) | Iran | Swimming pool and park pond (40) | 75 | 18 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp., Hartmannella spp., and Vahlkampfiids |

| Reyes-Batlle et al. (2017) | Spain | Recreational water (10) | 10 | 1 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Toula and Elahl 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Swimming pool (6) | 16 | 6 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Dodangeh et al. (2018) | Iran | Recreational hot spring | 24 | 11 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba castellanii T4 |

| Ghaderifar et al. 2018 | Iran | Parks pond water (13) | 90 | 31 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4 |

| Hikal et al (2018) | Egypt | Swimming pool (5) | 100 | 24 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria fowleri |

| Hikal et al. (2018) | Egypt | Swimming pool (5) | 100 | 79 | Morphology, PCR | Naegleria spp. |

| Lares-Jiménez et al. (2018) | Mexico | Hot spring (1) | 8 | 8 | Morphology, PCR | N. lovaniensis, A. jacobsi, Stenamoeba sp., and Vermamoeba vermiformis |

| Latiff et al. (2018) | Malaysia | Recreational hot spring (5) | 52 | 38 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Poor et al. (2018) | Iran | Swimming pool and hot tubs (10) | 40 | 8 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T3 and Acanthamoeba T4 |

| Vijayakumar (2018) | Saudi Arabia | Pools and recreation waters | 27 | 7 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Xue et al. 2018 | USA | lake recreation areas (10) | 160 | 56 | PCR | N. fowleri |

| Gabriel et al. 2019 | Malaysia | Recreational place | 57 | 40 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Haddad et al. (2019) | Iran | Hot springs | 54 | 15 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba castellanii T4, Vermamoeba vermiformis, N. australiensis, N. pageii, and N. gruberi |

| Hussain et al. (2019) | Malaysia | Recreational hot spring (5) | 50 | 38 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4, T15, T3, T5, T11, and T17 |

| Maghsoodloorad et al. 2019 | Iran | Recreational park water | 30 | 8 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 and Acanthamoeba spp. T15 |

| Salehi et al. 2019 | Iran | Park pool and swimming pool | 14 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T2, T4, T5, and T11 |

| Attariani et al. (2020) | Iran | Swimming pool | 42 | 3 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Ballares et al. 2020 | Philippines | Recreational water (6) | 16 | 6 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T5, and Acanthamoeba T9 |

| Bonilla-Lemus et al. 2020 | Mexico | Recreational water (9) | 9 | 9 | Morphology, PCR | N. australiensis, N. gruberi, N. fowleri, N. clarki, and N. pagei |

| Değerli et al. (2020) | Turkey | Thermal swimming pool | 434 | 148 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| El-Badry et al. 2020 | Egypt | Swimming pool (7) | 28 | 0 | Morphology, PCR | |

| Esboei et al. (2020) | Iran | Swimming pools | 30 | 12 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T4 |

| Latifi et al. (2020) | Iran | Hot spring and beach | 81 | 54 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba (T3, T4 e T5), V. vermiformis, and Naegleria spp. |

| Paknejad et al. (2020) | Iran | Swimming pool and bathtub | 166 | 31 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba T3, Acanthamoeba T4, Acanthamoeba T11, Acanthamoeba sp., Protacanthamoeba bohemica, and N. lovaniensis |

| Sarmadian et al. (2020) | Iran | Swimming pool (6) | 6 | 1 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Sarmadian et al. (2020) | Iran | Swimming pool (6) | 576 | 1 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Zeybek and Türkmen 2020 | Turkey | Swimming pool | 25 | 7 | Morphology, FISH | |

| Aykur and Dagci (2021) | Turkey | Swimming pool | 26 | 3 | PCR | Acanthamoeba T2, T4, and T5 |

| Bakri et al. 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Swimming pool | 10 | 4 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Berrilli et al. (2021) | Italy | Hot spring (2) | 36 | 33 | Morphology, PCR | V. vermiformisi, N. australiensisi, Acanthamoeba T4, and Acanthamoeba T15 |

| Eftekhari-Kenzerki et al. (2021) | Iran | Indoor public swimming pool (20) | 80 | 32 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba spp. |

| Reyes-Batlle et al. (2021) | Portugal | Swimming pool facilities (20) | 20 | 0 | PCR | |

| Nageeb et al. (2022) | Egypt | Swimming pool (2) | 8 | 0 | Morphology, PCR | |

| Rocha et al. 2022 | Brazil | Swimming pool (9) | 36 | 15 | Morphology | Acanthamoeba spp. and Naegleria spp. |

| Salehi et al. 2022 | Iran | Swimming pool and park pool | 20 | 17 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba (T2, T3, T4, T11, and T15) |

| Sousa-Ramos et al. 2022 | Cape Verde | Recreational fountain and swimming pool | 4 | 2 | Morphology, PCR | Acanthamoeba sp. T4 and Vannella sp. |

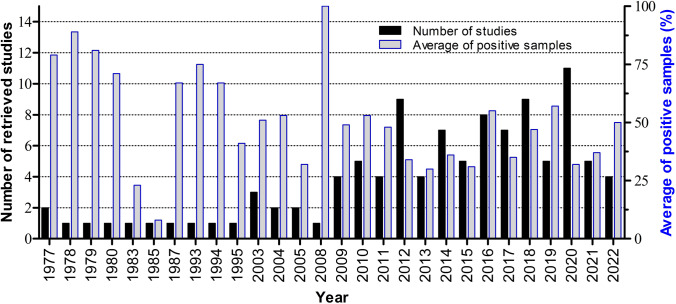

The included studies were published between 1977 and 2022, and the distribution of studies by year and the average percentage value of positive samples per year are shown in Fig. 2. FLA were detected in at least 1 sample of 97.17% (103/106) of selected studies (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of selected studies, and mean percentage of positive samples for FLA per year

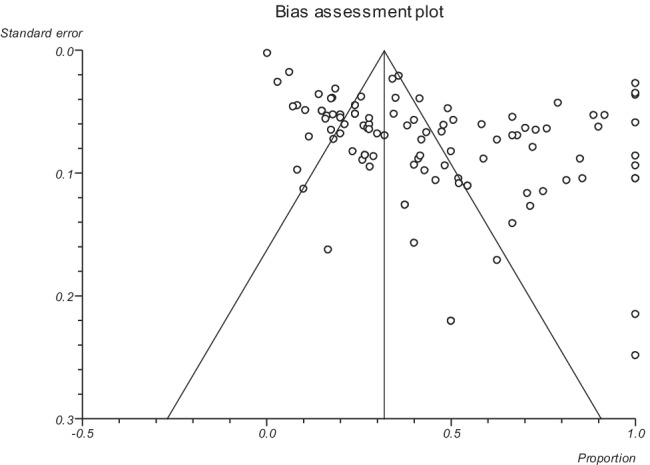

Publication bias was checked by Egger’s regression test, showing that it may have a substantial impact on total prevalence estimate (Egger bias: 6.8, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). This suggests that the reported global prevalence may have been impacted by publication bias.

Fig. 3.

Result of Egger’s bias assessment for the prevalence of free-living amoebae in swimming pools and recreational waters

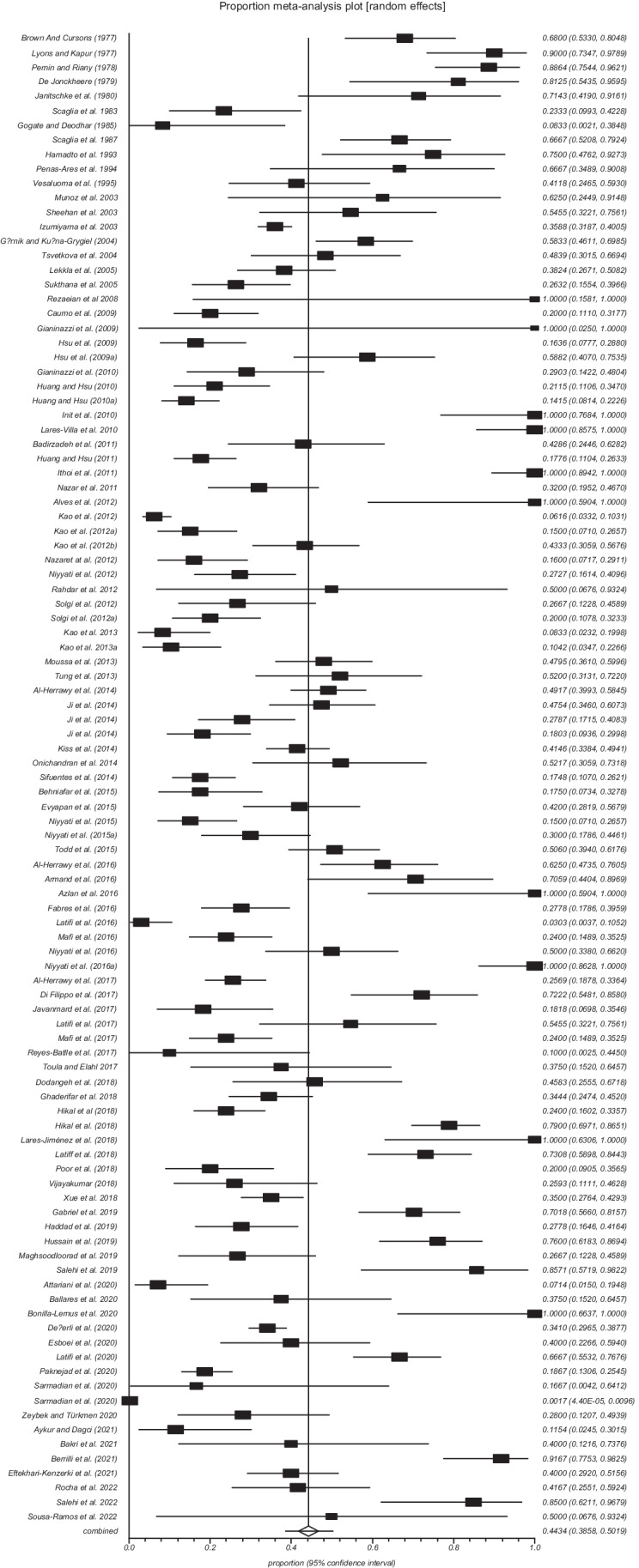

Based on the random-effects model meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of FLA in water sources was 44.34% (95% CI = 38.57–50.18). The included studies demonstrated a strong heterogeneity (Q = 2198.0, df = 102, I2 = 95.4%, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the worldwide prevalence of free-living amoebae in swimming pools and recreational waters

The global prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters considering studies published up to 2010 (1977–2010) was considerably higher 53.09% (95% CI = 43.33–62.73) than in studies published between 2010 and 2015, 37.07% (95% CI = 28.87–45.66), and those published after 2015 (> 2015–2022) 45.40% (95% CI = 35.48–55.51) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of FLA in water sources

| Subgroup variable | Prevalence (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Heterogeneity (Q) | P-value | Interaction test (X2) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||||

| < 2010 | 53.09 (43.33–62.73) | 89.5% | 210.4 | P < 0.001 | 449.4 | P < 0.001 |

| 2010–2015 | 37.07 (28.87–45.66) | 93.6% | 519.5 | P < 0.001 | ||

| > 2015 | 45.40 (35.48–55.51) | 96.7% | 1366.2 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Continent | ||||||

| Africa | 51.27 (35.08–67.33) | 93.5% | 107.8 | P < 0.001 | 156.7 | P < 0.001 |

| America | 63.99 (45.03–80.92) | 94.5% | 201.7 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Asia | 37.38 (30.12–44.93) | 95.7% | 1403.3 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Europe | 51.99 (42.52–61.40) | 89.5% | 190.6 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Country | ||||||

| Brazil | 43.70 (21.99–66.76) | 88.7% | 26.5 | P < 0.001 | 26.0 | P < 0.001 |

| China | 10.15 (4.99–16.87) | - | 0.1 | P = 0.737 | ||

| Egypt | 51.65 (31.74–71.30) | 95.3% | 107.0 | P < 0.001 | ||

| France | 69.62 (27.07–97.94) | - | 22.5 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Iran | 35.11 (24.74–46.26) | 95.9% | 787.8 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Italy | 64.76 (37.01–87.95) | 92.1% | 38.2 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Malaysia | 87.38 (73.20–96.72) | 85% | 33.3 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Mexico | 98.35 (92.56–99.96) | 0% | 0.1 | P = 0.913 | ||

| Philippines | 46.29 (31.43–61.48) | - | 0.7 | P = 0.377 | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 32.85 (21.28–45.60) | 0% | 1.0 | P = 0.602 | ||

| Spain | 37.68 (1.06–88.08) | - | 7.7 | P = 0.005 | ||

| Taiwan | 26.33 (17.36–36.42) | 90.6% | 116.4 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Thailand | 32.68 (21.82–44.57) | - | 1.9 | P = 0.160 | ||

| Turkey | 30.60 (20.92–41.23) | 65.6% | 8.7 | P = 0.033 | ||

| USA | 48.70 (22.32–75.47) | 95.3% | 63.7 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Origin | ||||||

| Hot springs | 39.12 (30.48–48.13) | 93% | 369.0 | P < 0.001 | 51.6 | P = 0.224 |

| Indoor hot swimming pools | 52.27 (14.55–88.50) | - | 1.8 | P = 0.169 | ||

| Public swimming pools | 49.47 (36.87–62.10) | 97% | 1201.5 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Recreational waters | 44.44 (33.19–55.99) | 95% | 538.7 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Thermal swimming pools | 46.05 (2674–65.99) | 88.8% | 26.7 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Diagnostic method | ||||||

| Morphology | 57.21 (37.99–7535) | 97.8% | 1083.3 | P < 0.001 | 373.5 | P < 0.001 |

| PCR | 25.78 (14.18–39.44) | 94.6% | 183.6 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Morphology and PCR | 43.16 (37.73–48.67) | 91.6% | 757.6 | P < 0.001 | ||

Considering the continents covered by the selected studies, the highest prevalence 63.99% (95% CI = 45.03–80.92) was reported in America and the lowest 37.38% (95% CI = 30.12–44.93) in Asia. Among the countries from which more than one study was included, Mexico had the highest prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters 98.35% (95% CI = 92.56–99.96), and the lowest prevalence 10.15% (95% CI = 4.99–16.87) was recorded in China (Table 2).

Considering the different sampling sources, the highest prevalence of FLA 52.27% (95% CI = 14.55–88.50) was obtained in indoor hot swimming pools, and the lowest prevalence 39.12% (95% CI = 30.48–48.13) was obtained in hot springs (Table 2).

The analysis of data from studies that used only morphological methods to identify FLA showed the highest prevalence 57.21% (95% CI = 37.99–7535), the lowest prevalence 25.78% (95% CI = 14.18–39.44) was obtained from studies based only on molecular methods (PCR), and an intermediate prevalence value 43.16% (95% CI = 37.73–48.67) was obtained by analyzing studies that simultaneously used morphological and molecular methods (Table 2).

The subgroup analysis revealed that there were statistically significant differences between the overall prevalence of FLA in water sources and year (X2 = 449.4, P < 0.001), continent (X2 = 156.7, P < 0.001), country (X2 = 26.0, P < 0.001), and diagnostic method (X2 = 373.5, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

The highest values of the global prevalence of different genera of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters were from Vahlkampfia spp. (54.20%), Acanthamoeba spp. (33.47%), and Naegleria spp. (30.95%). For other genera, Hartmannella spp./Vermamoeba spp., Stenamoeba spp., and Vannella spp., the global prevalence values were 20,73%, 12.05%, and 10.75%, respectively (Table 3). The results of Egger’s regression test, as well as the forest plot of the worldwide prevalence of each of these FLA genera in swimming pools and recreational waters, can be seen in Fig. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6 of the supplementary material, respectively.

Table 3.

Global prevalence, publication bias, and heterogeneity of FLA in water sources

| Genus | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | Cochran Q | df | I2 (%) | P-value | Egger bias | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthamoeba spp. | 33.47 (28.06–39.11) | 429.1 | 55 | 87.2% | < 0.001 | 3.4 | 0.0002 |

| Hartmannella spp./Vermamoeba spp. | 20.73 (7.73–38.39) | 30.55 | 5 | 83.8% | 0.0008 | 5.9 | 0.1363 |

| Naegleria spp. | 30.95 (22.85–39.69) | 676.0 | 38 | 94.4% | < 0.001 | 4.6 | 0.0054 |

| Stenamoeba spp. | 12.05 (0.08–39.61) | 3.2 | 1 | - | 0.0732 | - | - |

| Vahlkampfia spp. | 54.20 (27.49–79.67) | 12.6 | 2 | 84.2% | 0.0018 | - | - |

| Vannella spp. | 10.75 (0.01–37.14) | 2.2 | 1 | - | 0.133 | - | - |

CI, confidence interval; df, degree of freedom

Discussion

FLA are cosmopolitan microorganisms ubiquitous in all matrices of natural and anthropogenic environments, including water resources. The presence of FLA in pools and recreational waters is worrying, since some of these microorganisms are human pathogens/opportunists, as well as being widely implicated in persistence and/or pseudo-resistance of pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and fungi in water, including in water treated with disinfectants (Thomas et al. 2004; Staggemeier et al. 2016; Mavridou et al. 2018; Gomes et al. 2020; Hubert et al. 2021).

The studies included in present review are distributed by five continents; however, they have a heterogeneous spatial distribution within the territories of the continents; this can suggest differences in the level of FLA importance for health in the contexts of different countries, as well as differences in the frequency of cases diseases associated with the FLA. The frequency of cases of FLA-related diseases can be influenced by the difference in the predominance of risk factors and the sensitivity of the health surveillance strategy of each country, as well as the heterogeneous distribution of trained professionals carrying out research in this area. In addition, the ease of confusing symptoms of diseases associated with the FLA with those caused by other microorganisms, combined with some cases of rapid deterioration of the patient’s health and death (Jahangéer et al. 2020) can contribute to the rarity of reports or even the lack of association of diseases with FLA, especially in contexts where post-mortem study policies are not robust.

Our findings show that the global prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters is 44.34%; however, a higher (53.09%) and intermediate (45.40%) prevalence value was obtained when considering the data from studies published up to 2010 and studies published after 2015, respectively. A lower prevalence value (37.07%) was obtained when analyzing data from studies published between 2010 and 2015 (Table 2). A similar result was reported in a study that aimed to determine the prevalence of Naegleria spp. in water resources (Saberi et al. 2020). This reduction in the prevalence reported in most recent studies was attributed to the most accurate diagnosis and reduction of false positive results (Jahangeeer et al. 2020; Saberi et al. 2020), as contrary to studies published up to 2010, the vast majority of studies published after 2010 used molecular methods for FLA identification. Curiously, our results show that the overall prevalence of FLA considering studies that used both morphological and molecular methods is close to the mean of the prevalence values obtained from data from studies that used only one of the methods (Table 2). This may suggest that the simultaneous use of these two methods reduces the extreme values obtained separately by each of the methods, and that these methods can be complementary, especially in studies that aim to assess the presence or absence of viable FLA in water samples. The authors agree that the morphological method (generally based on culture) is more laborious and less precise than molecular methods in the identification of FLA (Saberi et al. 2020; Hikal et al. 2018).

The subgroup analysis considering the distribution of the studies by the continents showed that FLA are more prevalent in the swimming pools and recreational water from America (63.99%), followed by Europe (51.99%) and Africa (51.27%). In relation to countries, the highest value of the prevalence of FLA was obtained in Mexico (98.35%), followed by Malaysia (87.38%), France (69.62%), and Italy (64.76%), and the lowest values were obtained in China (10.15%), Taiwan (26.33%), Turkey (30.60), and Thailand (32.68%). As for the sample source, the indoor hot swimming pools presented a higher value (52.27%) of FLA prevalence, followed by public swimming pools (49.47%) and thermal swimming pools (46.05%). The genera Vahlkampfia spp., Acanthamoeba spp., and Naegleria spp. were more prevalent, presenting the following prevalence values, 54.20%, 33.47%, and 30.95%, respectively (Table 3). The lowest prevalence value was for Vannella spp. (10.75%). These results are in accordance with other authors whose studies reported high prevalence of FLA (Acanthamoeba spp. 48.5%, Naegleria spp. 46.0%, Vermamoeba spp. 4.7%, and Balamuthia spp. 0.7%) in hot springs (Fabros et al. 2021). Saberi et al. (2020) reported the following prevalence values for Naegleria spp. 44.80%, 32.88%, and 21.27%, in swimming pools, hot springs, and recreational waters, respectively. The subgroup analysis showed that prevalence values are statistically different (P < 0.001) for all variables studied (Table 2). These findings are in accordance with other studies that reported a variable distribution in abundance and diversity of FLA species around the world (Jahangéer et al. 2020; Saberi et al. 2020; Fabros et al. 2021).

The global prevalence of FLA reported in the present study (44.34%) is worrying, since direct contact between humans and these waters is often established. In addition, several studies have reported the isolation of several potentially pathogenic FLA (Caumo et al. 2009; Alves et al. 2012; Behniafar et al. 2015;) and others with proven pathogenicity in ex vivo and in vivo trials (Brown and Cursons 1977; Janitschke et al. 1980; Rivera et al. 1983, 1993; Gianinazzi et al. 2009). Most of these FLA are identified as N. fowleri, Acanthamoeba spp., and Balamuthia mandrillaris. Most isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. reported as pathogens are distributed among the T5, T11, T15, T3, and T4 genotypes, and among them, the T4 genotype is more prevalent in hot springs (Mahmoudi et al. 2015; Fabros et al. 2021) and is associated with most cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis (Diehl et al. 2021; Bellini et al. 2022). The presence and abundance of FLA in swimming pool water clearly indicate that in addition to these microorganisms being resistant to chlorine in the dosage used in the treatment of drinking water (Thomas et al. 2004; Majid et al. 2017; Gomes et al. 2020), they are also resistant to chlorine and other disinfectants in the dosage used for swimming pools and artificial recreational waters (Rivera et al. 1983; Kiss et al. 2014; Zeybek et al. 2017). Acanthamoeba castellanii trophozoites and cysts have been reported to be resistant to exposure for more than 2 h to NaOCl and NaCl at concentrations up to 8 mg/L and 40 g/L, respectively. On the other hand, exposure to the combined effect of NaOCl or NaCl with ultraviolet C (UV-C) radiation resulted in rapid inactivation of trophozoites even when lower concentrations of NaOCl and NaCl were used (Chaúque and Rott 2021a, b). Cyst inactivation was achieved by twice as long exposure (300 min) to the combined effect of NaOCl or NaCl and UV-C, with redosing of NaOCl. Despite having demonstrated that both methods are effective, and that they have a strong potential to be used in the effective disinfection of swimming pool water, it was found that the use of NaCl is more cost-effective, as it is cheaper and has a residual effect; redosing is not necessary and is simple to apply (Chaúque and Rott 2021a, b). On the other hand, the use of solar UV radiation (UV-A and B) in place of UV-C (which depends on electricity) can further reduce the cost of the disinfection process. The effectiveness of using solar UV to photolyse NaOCl to inactivate chlorine-resistant microorganisms has been previously documented (Zhou et al. 2014). Readers interested in solar water disinfection technology applicable to recreational water treatment are directed to the appropriate literature (Chaúque and Rott 2021a; Chaúque et al. 2022).

The main aspects that constituted limitations for the present study are the following: the lack of studies carried out in most countries of the world; the heterogeneous distribution of the number of studies among the included countries; difference in FLA identification methods among many studies and discrepancy in the number of samples considered positive by the morphological and molecular method in the same study. The loss of isolates from positive samples in some studies, due to fungal contamination of non-nutrient agar plates prior to molecular identification of the amoebae, was also a limitation.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the prevalence of FLA in swimming pools and recreational waters is high and, therefore, of concern, since there is a risk of contracting infection by pathogenic amoebae or other pathogens (such as fungi, bacteria, and viruses) that may be harbored and dispersed by FLA in water (Mavridou et al. 2018). Thus, it is necessary to implement disinfection techniques that are effective in eliminating microorganisms, including FLA, in swimming pools and artificial recreational waters. The use of the combined effect of NaCl and UV-C has great potential to be used to eliminate or minimize the risk of infection by FLA in swimming pools and other artificial recreational waters. The potential risk of infection by FLA in natural recreational waters needs to be routinely quantified by health surveillance. Warning signs need to be placed where there is minimal risk of infection by FLA, and people using these water bodies need to be educated about the potential risk and possible safety measures. These measures include not diving in recreational waters wearing contact lenses, preventing water from entering the airways and eyes, and avoiding jumping into the water. Health care workers (especially those working near recreational water use sites with risk of infection by FLA) need to be trained to be on the lookout for symptoms suggestive of infection by FLA, especially in summer.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) for the scholarship granted to Chaúque, BJM, and CNPq for the researcher grant to Rott, MB.

Author contribution

B.J.M.C. conceived the idea, wrote the project, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. D.S. participated in the conception of the idea, performed the data verification, and wrote and revised the manuscript. D.A. performed data analysis and manuscript review. M.B.R. managed the project and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the publication of this version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Beni Jequicene Mussengue Chaúque, Email: benichauq@gmail.com.

Denise Leal dos Santos, Email: delealsantos@yahoo.com.br.

Davood Anvari, Email: davood_anvari@live.com.

Marilise Brittes Rott, Email: marilise.rott@ufrgs.br.

References

- Aksozek A, Mcclellan K, Howard K, et al. Resistance of Acanthamoeba castellanii cysts to physical. Chemical, and Radiological Conditions. J Parasitol. 2002;88(3):621–623. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0621:ROACCT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Herrawy A, Bahgat M, Mohammed AE, et al. Acanthamoeba species in swimming pools of Cairo, Egypt. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9(2):194–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Herrawy AZ, Gad MA, Abd El-Aziz A, et al. Morphological and molecular detection of potentially pathogenic free-living amoebae in swimming pool samples. Egypt J Environ Res. 2016;5:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Herrawy AZ, Khalil MI, El-Sherif SS, et al. Surveillance and molecular identification of Acanthamoeba and Naegleria species in two swimming pools in Alexandria University, Egypt. Iran J Parasitol. 2017;12(2):196–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves DSMM, Moraes AS, Nitz N, et al. Occurrence and characterization of Acanthamoeba similar to genotypes T4, T5, and T2/T6 isolated from environmental sources in Brasília, Federal District, Brazil. Exp Parasitol. 2012;131(2):239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armand B, Motazedian MH, Asgari Q. Isolation and identification of pathogenic free-living amoeba from surface and tap water of Shiraz City using morphological and molecular methods. Parasitol Res. 2016;115(1):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attariani H, Turki H, Shoja S, et al. Investigating the frequency of free-living amoeba in water resources with emphasis on Acanthamoeba in Bandar Abbas city, Hormozgan province, Iran in 2019–2020. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):420. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05267-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykur M, Dagci H. Evaluation of molecular characterization and phylogeny for quantification of Acanthamoeba and Naegleria fowleri in various water sources. Turkey Plos One. 2021;16(8):e0256659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azlan AM, Rasid MN, Richard RL, et al. Titiwangsa Lake a source of urban parasitic contamination. Trop Biomed. 2016;33(3):594–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badirzadeh A, Niyyati M, Babaei Z, et al. Isolation of free-living amoebae from sarein hot springs in Ardebil Province, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2011;6(2):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakri R, Mohamed R, Alghanmi M, et al. Isolation, morphotyping, molecular characterization and prevalence of free-living amoebae from different water sources in Makkah city, Saudi Arabia. J Umm Al-Qura Univ Med Sci. 2021;7(2):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Balczun C, Scheid PL. Free-living amoebae as hosts for and vectors of intracellular microorganisms with public health significance. Viruses. 2017;9(4):65. doi: 10.3390/v9040065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballares LD, Masangkay FR, Dionisio J, et al. Molecular detection of Acanthamoeba spp. in Seven Crater Lakes of Laguna, Philippines. J Water Health. 2020;18(5):776–784. doi: 10.2166/wh.2020.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behniafar H, Niyyati M, Lasjerdi Z. Molecular characterization of pathogenic Acanthamoeba isolated from drinking and recreational water in East Azerbaijan, Northwest Iran. Environ Health Insights. 2015;9:7–12. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S27811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini NK, Thiemann OH, Reyes-Batlle M, et al. A history of over 40 years of potentially pathogenic free-living amoeba studies in Brazil - a systematic review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2022;117:e210373. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760210373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrilli F, Di Cave D, Novelletto A, Di Filippo MM. PCR-based identification of thermotolerant free-living amoebae in Italian hot springs. Eur J Protistol. 2021;80:125812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2021.125812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Lemus P, Rojas-Hernández S, Ramírez-Flores E, et al. Isolation and identification of Naegleria Species in irrigation channels for recreational use in Mexicali Valley, Mexico. Pathogens. 2020;9(10):820. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9100820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TJ, Cursons RT. Pathogenic free-living amebae (PFLA) from frozen swimming areas in Oslo, Norway. Scand J Infect Dis. 1977;9(3):237–240. doi: 10.3109/inf.1977.9.issue-3.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunsuwansakul C, Mahboob T, Hounkong K, et al. Acanthamoeba in Southeast Asia - overview and challenges. Korean J Parasitol. 2019;57(4):341–357. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2019.57.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capewell LG, Harris AM, Yoder JS, et al. Diagnosis; clinical course; and treatment of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the United States; 1937–2013. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4:68–75. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caumo K, Frasson AP, Pens CJ. Potentially pathogenic Acanthamoeba in swimming pools: a survey in the southern Brazilian city of Porto Alegre. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103(6):477–485. doi: 10.1179/136485909X451825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaúque BJM, Benetti AD, Corção G, et al. A new continuous-flow solar water disinfection system inactivating cysts of Acanthamoeba castellanii, and bacteria. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2021;20(1):123–137. doi: 10.1007/s43630-020-00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaúque BJM, Brandão FG, Rott MB. Development of solar water disinfection systems for large-scale public supply, state of the art, improvements and paths to the future – a systematic review. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(3):107887. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2022.107887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaúque BJM, Rott MB (2021a) Photolysis of sodium chloride and sodium hypochlorite by ultraviolet light inactivates the trophozoites and cysts of Acanthamoeba castellanii in the water matrix. J Water Health 19(1):190–202. 10.2166/wh.2020.401

- Chaúque BJM, Rott MB (2021b) Solar disinfection (SODIS) technologies as alternative for large-scale public drinking water supply: advances and challenges. Chemosphere 281:130754. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130754 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chaúque BJM, Rott MB. The role of free-living amoebae in the persistence of viruses in the era of severe acute respiratory syndrome 2, should we be concerned? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2022;55:e0045. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0045-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope JR, Landa J, Nethercut H, Collier SA, Glaser C, Moser M, Puttagunta R, Yoder JS, Ali SL (2019) (2018) The Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Balamuthia mandrillaris Disease in the United States 1974–2016. Clinical Infectious Diseases 68(11):1815–1822. 10.1093/cid/ciy813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Jonckheere JF. Pathogenic free-living amoebae in swimming pools: survey in Belgium. Ann Microbiol (paris) 1979;130B(2):205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Değerli S, Değerli N, Çamur D, et al. Genotyping by sequencing of Acanthamoeba and Naegleria isolates from the thermal pool distributed throughout Turkey. Acta Parasit. 2020;65:174–186. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delafont V, Bouchon D, Héchard Y, Moulin L. Environmental factors shaping cultured free-living amoebae and their associated bacterial community within drinking water network. Water Res. 2016;100:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey R, Dlusskaya E, Ashbolt NJ. SARS-CoV-2 surrogate (Phi6) environmental persistence within free-living amoebae. J Water Health. 2022;20(1):83–91. doi: 10.2166/wh.2021.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey R, Folkins MA, Ashbolt NJ. Extracellular amoebal-vesicles: potential transmission vehicles for respiratory viruses. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):25. doi: 10.1038/s41522-021-00201-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Filippo MM, Novelletto A, Di Cave D, Berrilli F. Identification and phylogenetic position of Naegleria spp. from geothermal springs in Italy. Exp Parasitol. 2017;183:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MLN, Paes J, Rott MB. Genotype distribution of Acanthamoeba in keratitis: a systematic review. Parasitol Res. 2021;120:3051–3063. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodangeh S, Kialashaki E, Daryani A, et al. Isolation and molecular identification of Acanthamoeba spp. from hot springs in Mazandaran province, northern Iran. J Water Health. 2018;16(5):807–813. doi: 10.2166/wh.2018.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos DL, Kwitko S, Marinho DR. Acanthamoeba keratitis in Porto Alegre (southern Brazil): 28 cases and risk factors. Parasitol Res. 2018;117(3):747–750. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5745-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhari-Kenzerki R, Solhjoo K, Babaei Z. High occurrence of Acanthamoeba spp. in the water samples of public swimming pools from Kerman Province, Iran. J Water Health. 2021;19(5):864–871. doi: 10.2166/wh.2021.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Badry AA, Aufy SM, El-Wakil ES, et al. First identification of Naegleria species and Vahlkampfia ciguana in Nile water, Cairo, Egypt: seasonal morphology and phylogenetic analysis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esboei BR, Fakhar M, Saberi R. Genotyping and phylogenic study of Acanthamoeba isolates from human keratitis and swimming pool water samples in Iran. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2020;11:e00164. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evyapan G, Koltas IS, Eroglu F. Genotyping of Acanthamoeba T15: the environmental strain in Turkey. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109(3):221–224. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabres LF, Dos Santos SPR, Benitez LB, Rott MB (2016) Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba spp. from thermal swimming pools and spas in Southern Brazil. Acta Parasitol. 61(2):221–7. 10.1515/ap-2016-0031 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fabros MRL, Diesta XRS, Oronan JA, et al. Current report on the prevalence of free-living amoebae (FLA) in natural hot springs: a systematic review. J Water Health. 2021;19(4):563–574. doi: 10.2166/wh.2021.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler M, Carter RF (1965) Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acanthamoeba sp.: a preliminary report. British medical journal 2(5464):740–742. 10.1136/bmj.2.5464.734-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gabriel S, Khan NA, Siddiqui R. Occurrence of free-living amoebae (Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, Naegleria) in water samples in Peninsular Malaysia. J Water Health. 2019;17(1):160–171. doi: 10.2166/wh.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garajová M, Mrva M, Vaškovicová N, et al. Cellulose fibrils formation and organisation of cytoskeleton during encystment are essential for Acanthamoeba cyst wall architecture. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4466. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41084-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman BB (2001) Amoebic Encephalitis Due to Sappinia diploidea. JAMA 285(19):2450. 10.1001/jama.285.19.2450 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ghaderifar S, Najafpoor AA, Zarrinfar H, et al. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba from pond water of parks in a tropical and subtropical region in the Middle East, and its relation with physicochemical parameters. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianinazzi C, Schild M, Wüthrich F, et al. Potentially human pathogenic Acanthamoeba isolated from a heated indoor swimming pool in Switzerland. Exp Parasitol. 2009;121(2):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianinazzi C, Schild M, Zumkehr B, et al. Screening of Swiss hot spring resorts for potentially pathogenic free-living amoebae. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogate A, Deodhar L. Isolation and identification of pathogenic Naegleria fowleri (aerobia) from a swimming pool in Bombay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79(1):134. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes TS, Vaccaro L, Magnet M. Presence and interaction of free-living amoebae and amoeba-resisting bacteria in water from drinking water treatment plants. Sci Total Environ. 2020;719:137080. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górnik K, Kuźna-Grygiel W. Presence of virulent strains of amphizoic amoebae in swimming pools of the city of Szczecin. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2004;11(2):233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greub G, Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:413–433. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad MHF, Khoshnood S, Mahmoudi MR, et al. Molecular identification of free-living amoebae (Naegleria spp., Acanthamoeba spp. and Vermamoeba spp.) isolated from un-improved hot springs, Guilan Province, Northern Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2019;14(4):584–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadto HH, Aufy SM, el-Hayawan IA, et al. Study of free living amoebae in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1993;23(3):631–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikal WM, Hikal W, Dkhil MA, Dkhil M. Nested PCR assay for the rapid detection of Naegleria fowleri from swimming pools in Egypt. Acta Ecol Sin. 2018;38:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2017.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu B-H, Ma P-H, Liou T-S. Identification of 18S ribosomal DNA genotype of Acanthamoeba from hot spring recreation areas in the central range, Taiwan. J Hydrol. 2009;367(3–4):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu BM, Lin CL, Shih FC. Survey of pathogenic free-living amoebae and Legionella spp. in mud spring recreation area. Water Res. 2009;43(11):2817–28. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SW, Hsu BM. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba from Taiwan spring recreation areas using culture enrichment combined with PCR. Acta Trop. 2010;115(3):282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SW, Hsu BM. Survey of Naegleria and its resisting bacteria-Legionella in hot spring water of Taiwan using molecular method. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:1395–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1815-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SW, Hsu BM. Survey of Naegleria from Taiwan recreational waters using culture enrichment combined with PCR. Acta Trop. 2011;119(2–3):114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert F, Rodier MH, Minoza A. Free-living amoebae promote Candida auris survival and proliferation in water. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2021;72(1):82–89. doi: 10.1111/lam.13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain RHM, Ishak AR, Ghani MKA, et al. Occurrence and molecular characterisation of Acanthamoeba isolated from recreational hot springs in Malaysia: evidence of pathogenic potential. J Water Health. 2019;17(5):813–825. doi: 10.2166/wh.2019.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Init I, Lau YL, Fadzlun AA, Foead AI. Detection of free living amoebae, Acanthamoeba and Naegleria, in swimming pools, Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2010;27(3):566–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ithoi I, Ahmad AF, Nissapatorn V, et al. Detection of Naegleria species in environmental samples from Peninsular Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e24327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiyama S, Yagita K, Furushima-Shimogawara R, et al. Occurrence and distribution of Naegleria species in thermal waters in Japan. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2003;50(Suppl):514–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahangeer M, Mahmood Z, Munir NR, et al. Naegleria fowleri: sources of infection, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management; a review. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(2):199–212. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janitschke K, Werner H, Müller G. Das Vorkommen von freilebenden Amöben mit möglichen pathogenen Eigenschaften in Schwimmbädern [Examinations on the occurrence of free-living amoebae with possible pathogenic traits in swimming pools (author’s transl)] Zentralbl Bakteriol b. 1980;170(1–2):108–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanmard E, Niyyati M, Lorenzo-Morales J, et al. Molecular identification of waterborne free living amoebae (Acanthamoeba, Naegleria and Vermamoeba) isolated from municipal drinking water and environmental sources, Semnan province, north half of Iran. Exp Parasitol. 2017;183:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji WT, Hsu BM, Chang TY, et al. Surveillance and evaluation of the infection risk of free-living amoebae and Legionella in different aquatic environments. Sci Total Environ. 2014;499:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RO, Cope JR, Moskowitz M et al MJ (2016) Notes from the Field: primary amebic meningoencephalitis associated with exposure to swimming pool water supplied by an overland pipe - Inyo County, California, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 65(16):424. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6516a4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kang H, Sohn HJ, Seo GE, et al. Molecular detection of free-living amoebae from Namhangang (southern Han River) in Korea. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):335. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57347-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao PM, Hsu BM, Chen NH, et al. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba species from thermal spring environments in southern Taiwan. Exp Parasitol. 2012;130(4):354–358. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao P-M, Hsu B-M, Chiu Y-C, et al. Identification of the Naegleria species in natural watersheds used for drinking and recreational purposes in Taiwan. J Environ Eng. 2012;138(8):893–898. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0000549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kao PM, Tung MC, Hsu BM, et al. Occurrence and distribution of Naegleria species from thermal spring environments in Taiwan. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2012;56(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/lam.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao PM, Tung MC, Hsu BM et al (2013a) Quantitative detection and identification of Naegleria spp. in various environmental water samples using real-time quantitative PCR assay. Parasitol Res 112(4):1467–74. 10.1007/s00436-013-3290-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kao PM, Tung MC, Hsu BM, et al. Real-time PCR method for the detection and quantification of Acanthamoeba species in various types of water samples. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(3):1131–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss C, Barna Z, Vargha M, Török JK. Incidence and molecular diversity of Acanthamoeba species isolated from public baths in Hungary. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2551–2557. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3905-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król-Turmińska K, Olender A. Human infections caused by free-living amoebae. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(2):254–260. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1233568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landell MF, Salton J, Caumo K. Isolation and genotyping of free-living environmental isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. from bromeliads in Southern Brazil. Exp Parasitol. 2013;134(3):290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lares-Jiménez LF, Borquez-Román MA, Lares-García C, et al. Potentially pathogenic genera of free-living amoebae coexisting in a thermal spring. Exp Parasitol. 2018;195:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lares-Villa F, Hernández-Peña C. Concentration of Naegleria fowleri in natural waters used for recreational purposes in Sonora, Mexico (November 2007-October 2008) Exp Parasitol. 2010;126(1):33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latiff NSA, Jali A, Azmi NA, et al. A ocorrência de Acanthamoeba e Naegleria em águas recreativas de fontes termais selecionadas em Selangor, Malásia. Int J Trop Med. 2018;13(3):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Latifi A, Salami M, Kazemirad E, Soleimani M. Isolation and identification of free-living amoeba from the hot springs and beaches of the Caspian Sea. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2020;10:e00151. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latifi AR, Niyyati M, Lorenzo-Morales J, et al. Presence of Balamuthia mandrillaris in hot springs from Mazandaran province, northern Iran. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(11):2456–2461. doi: 10.1017/S095026881600073X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latifi AR, Niyyati M, Lorenzo-Morales J, et al. Occurrence of Naegleria species in therapeutic geothermal water sources. North Iran Acta Parasitol. 2017;62(1):104–109. doi: 10.1515/ap-2017-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekkla A, Sutthikornchai C, Bovornkitti S, Sukthana Y. Free-living ameba contamination in natural hot springs in Thailand. SE Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(4):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons TB, Kapur R. Limax amoebae in public swimming pools of Albany, Schenectady, and Rensselaer Counties, New York: their concentration, correlations, and significance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33(3):551–555. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.3.551-555.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mafi M, Niyyati M, Haghighi A, Lasjerdi Z (2017) Contamination of swimming pools and park ponds with free living amoebae in Tehran. Med J Tabriz Uni Med Sciences Health Services 38(6):2783–2031. https://mj.tbzmed.ac.ir/Article/15215

- Maghsoodloorad S, Maghsoodloorad E, Tavakoli Kareshk A, et al. Thermotolerant Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from recreational water in Gorgan City, north of Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2019;43(2):240–245. doi: 10.1007/s12639-018-01081-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi MR, Rahmati B, Seyedpour SH, Karanis P. Occurrence and molecular characterization of free-living amoeba species (Acanthamoeba, Hartmannella, and Saccamoeba limax) in various surface water resources of Iran. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(12):4669–4674. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majid MAA, Mahboob T, Mong BG, et al. Pathogenic waterborne free-living amoebae: an update from selected Southeast Asian countries. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0169448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschio JV, Corção G, Rott MB. Identification of Pseudomonas spp. as amoeba-resistant microorganisms in isolates of Acanthamoeba. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57(1):81–83. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652015000100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavridou A, Pappa O, Papatzitze O, et al. Exotic tourist destinations and transmission of infections by swimming pools and hot springs-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2730. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanez GD, Masangkay FR, Martin IGL. Epidemiology of free-living amoebae in the Philippines: a review and update. Pathog Glob Health. 2022;3:1–10. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2022.2035626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa M, De Jonckheere JF, Guerlotté J, et al. Survey of Naegleria fowleri in geothermal recreational waters of Guadeloupe (French West Indies) PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz V, Reyes H, Toche P et al (2003) Isolation of free living amoebae from public swimming pool in Santiago, Chile. Parasitologia Latinoamericana 58(3/4):106–111. https://eurekamag.com/research/004/215/004215933.php

- Murakawa GJ, McCalmont T, Altman J et al (1995) Disseminated acanthamebiasis in patients with AIDS. A report of five cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 131(11):1291–1296. 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690230069011 [PubMed]

- Nageeb MM, Eldeek HEM, Attia RAH, et al. Isolation and morphological and molecular characterization of waterborne free-living amoebae: evidence of potentially pathogenic Acanthamoeba and Vahlkampfiidae in Assiut, Upper Egypt. Plos One. 2022;17(7):e0267591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazar M, Haghighi A, Niyyati M, et al. Genotyping of Acanthamoeba isolated from water in recreational areas of Tehran, Iran. J Water Health. 2011;9(3):603–608. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazar M, Haghighi A, Taghipour N, et al. Molecular identification of Hartmannella vermiformis and Vannella persistens from man-made recreational water environments, Tehran, Iran. Parasitol Res. 2012;111:835–839. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2906-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisar MA, Ross KE, Brown MH, et al. Legionella pneumophila and protozoan hosts: implications for the control of hospital and potable water systems. Pathogens. 2020;9(4):286. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyyati M, Lasjerdi Z, Nazar M, et al. Screening of recreational areas of rivers for potentially pathogenic free-living amoebae in the suburbs of Tehran. Iran J Water Health. 2012;10(1):140–146. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyyati M, Lasjerdi Z, Zarein-Dolab S et al (2015a) Morphological and molecular survey of Naegleria spp. in water bodies used for recreational purposes in Rasht city, Northern Iran. Iran J Parasitol 10(4):523–529 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Niyyati M, Nazar M, Lasjerdi Z (2015b) Reporting of T4 genotype of Acanthamoeba isolates in recreational water sources of Gilan Province, Northern Iran. Novel Biomed 3(1):20–4. 10.22037/nbm.v3i1.7177

- Niyyati M, Saberi R, Latifi A, Lasjerdi Z. Distribution of Acanthamoeba genotypes isolated from recreational and therapeutic geothermal water sources in Southwestern Iran. Environ Health Insights. 2016;10:69–74. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S38349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyyati M, Saberi R, Lorenzo-Morales J, Salehi R. High occurrence of potentially-pathogenic free-living amoebae in tap water and recreational water sources in South-West Iran. Trop Biomed. 2016;33(1):95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onichandran S, Kumar T, Salibay CC. Waterborne parasites: a current status from the Philippines. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:244. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2021;372:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paknejad N, Hajialilo E, Saraei M, Javadi A (2020) Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba genotypes and Naegleria spp. from the water samples of public swimming pools in Qazvin, Iran. J Water Health 18(2):244–251. 10.2166/wh.2019.074 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Paltiel M, Powell E, Lynch J, et al. Disseminated cutaneous acanthamebiasis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2004;73(4):241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazoki H, Niyyati M, Javanmard E, et al. Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of free-living amoebae (Acanthamoeba, Naegleria, and Vermamoeba) in the farmland soils and recreational places in Iran. Acta Parasitol. 2020;65(1):36–43. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas-Ares M, Paniagua-Crespo E, Madriñan-Choren R, et al. Isolation of free-living pathogenic amoebae from thermal spas in N.W Spain. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1994;78:83–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00475670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pernin P, Riany A (1978) Etude sur la présence d’amibes libres’ dans les eaux des piscines lyonnaises [Study on the presence of “free-living” amoebae in the swimming-pools of Lyon (author’s transl)]. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 53(4):333–44. French [PubMed]

- Poor BM, Dalimi A, Ghafarifar F, et al. Contamination of swimming pools and hot tubs biofilms with Acanthamoeba. Acta Parasit. 2018;63:147–153. doi: 10.1515/ap-2018-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahdar M, Niyyati M, Salehi M, et al. Isolation and genotyping of Acanthamoeba strains from environmental sources in Ahvaz City, Khuzestan Province, Southern Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2012;7(4):22–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayamajhee B, Subedi D, Peguda HK. A systematic review of intracellular microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to understand potential impact for infection. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;10(2):225. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Batlle M, Gabriel MF, Rodríguez-Expósito R, et al. Evaluation of the occurrence of pathogenic free-living amoeba and bacteria in 20 public indoor swimming pool facilities. MicrobiologyOpen. 2021;10(1):e1159. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Batlle M, Wagner C, López-Arencibia A, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of a Naegleria strain from a recreational water fountain in Tenerife, Canary Islands. Spain Acta Parasitol. 2017;62(2):265–268. doi: 10.1515/ap-2017-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaeian M, Niyyati M, Farnia Sh, Haghi AM (2008) Isolation of Acanthamoeba spp. from different environmental sources. Iranian J Parasitol 3(1):44–47

- Rivera F, Ramírez E, Bonilla P, et al. Pathogenic and free-living amoebae isolated from swimming pools and physiotherapy tubs in Mexico. Environ Res. 1993;62(1):43–52. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1993.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera F, Ramírez P, Vilaclara G, et al. A survey of pathogenic and free-living amoebae inhabiting swimming pool water in Mexico City. Environ Res. 1983;32(1):205–211. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(83)90207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha MJ, Sousa KK, Carneiro JLS, Weber DM, (2022 Isolation of potentially pathogenic free-living amoebae in swimming pools for collective use located in the municipality of Redenção, Pará, Brazil. Rev Ciênc Med 31:e225222. 10.24220/2318- 0897v31e2022a5222

- Saberi R, Seifi Z, Dodangeh S et al et al (2020) A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on the global prevalence of Naegleria spp. in water sources. Transbound Emerg Dis. 67(6):2389–2402. 10.1111/tbed.13635 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saberi R, Fakhar M, Makhlough A, Sedighi O, Tabaripour R, Asfaram S, Latifi A, Espahbodi F, Sharifpour A (2021) First evidence for colonizing of acanthamoeba T4 genotype in urinary tracts of patients with recurrent urinary tract infections. Acta Parasitologica 66(3):932–937. 10.1007/s11686-021-00358-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saburi E, Rajaii T, Behdari A, et al. Free-living amoebae in the water resources of Iran: a systematic review. J Parasit Dis. 2017;41(4):919–928. doi: 10.1007/s12639-017-0950-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi M, Niazkar HR, Nasirzadeh A (2019) Isolation and genotyping of Acanthamoeba strains from water sources of Kermanshah, Iran. Ann Parasitol 65(4):397–402. 10.17420/ap6504.226 [PubMed]

- Salehi M, Spotin A, Hajizadeh F et al (2022) Molecular characterization of Acanthamoeba spp. from different sources in Gonabad, Razavi Khorasan, Iran. Gene Reports 27:101573. 10.1016/j.genrep.2022.101573

- Santos DL, Virginio VG, Kwitko S et al (2021) Profile of contact lens wearers and associated risk factors for Acanthamoeba spp., In: Nascimento RM (ed) Microbiologia: clínica, ambiental e alimentos. Editora Atena, cap. 14:151–161. 10.22533/at.ed.543210120

- Santos LC, Oliveira MS, Lobo RD et al (2009) Acanthamoeba spp. in urine of critically ill patients. Emerg Infect Dis 15(7):1144–1146. 10.3201/eid1507.081415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sarink MJ, van der Meijs NL, Denzer K, et al. Three encephalitis-causing amoebae and their distinct interactions with the host. Trends Parasitol. 2022;38(3):230–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadian H, Hazbavi Y, Didehdar M, et al. Fungal and parasitic contamination of indoor public swimming pools in Arak, Iran. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s42506-020-0036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglia M, Gatti S, Brustia R et al (1987) Pathogenic and non-pathogenic Naegleria and Acanthamoeba spp.: a new autochthonous isolate from an Italyn thermal area. Microbiologica 10(2):171–82 [PubMed]

- Scaglia M, Strosselli M, Grazioli V, et al. Isolation and identification of pathogenic Naegleria australiensis (Amoebida, Vahlkampfiidae) from a spa in northern Italy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(6):1282–1285. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1282-1285.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid P. Relevance of free-living amoebae as hosts for phylogenetically diverse microorganisms. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(7):2407–2414. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3932-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan KB, Fagg JA, Ferris MJ, et al. PCR detection and analysis of the free-living amoeba Naegleria in hot springs in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(10):5914–5918. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5914-5918.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri: an old enemy presenting new challenges. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifuentes LY, Choate BL, Gerba CP, et al. The occurrence of Naegleria fowleri in recreational waters in Arizona. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2014;49(11):1322–1330. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2014.910342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares SS, Souza TK, Berté FK, et al. Occurrence of infected free-living amoebae in cooling towers of Southern Brazil. Curr Microbiol. 2017;74(12):1461–1468. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solgi R, Niyyati M, Haghighi A et al (2012a) Thermotolerant Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from therapeutic hot springs in Northwestern Iran. J Water Health 10(4):650–6. 10.2166/wh.2012.032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Solgi R, Niyyati M, Haghighi A, Mojarad EN (2012b) Occurrence of thermotolerant Hartmannella vermiformis and Naegleria spp. in hot springs of Ardebil Province, Northwest Iran. Iran J Parasitol 7(2):47–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Ramos D, Reyes-Batlle M, Bellini NK, et al. Pathogenic free-living amoebae from water sources in Cape Verde. Parasitol Res. 2022;121(8):2399–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00436-022-07563-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]