Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy has traditionally been defined in various texts as the use of 5 or more chronic drugs, the use of inappropriate drugs, or drugs that are not clinically authorized. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of polypharmacy among the COVID-19 patients, and the side effects, by systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

This study was performed by systematic review method and in accordance with PRISMA 2020 criteria. The protocol in this work is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021281552). Particular databases and repositories have been searched to identify and select relevant studies. The quality of articles was assessed based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale checklist. Heterogeneity of the studies was measured using the I2 test.

Results

The results of meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of polypharmacy in 14 studies with a sample size of 189,870 patients with COVID-19 is 34.6% (95% CI: 29.6–40). Studies have shown that polypharmacy is associated with side effects, increased morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. The results of meta-regression analysis reported that with increasing age of COVID-19 patients, the prevalence of polypharmacy increases (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The most important strength of this study is the updated search to June 2022 and the use of all databases to increase the accuracy and sensitivity of the study. The most important limitation of this study is the lack of proper definition of polypharmacy in some studies and not mentioning the number of drugs used for patients in these studies.

Conclusion

Polypharmacy is seen in many patients with COVID-19. Since there is no definitive cure for COVID-19, the multiplicity of drugs used to treat this disease can affect the severity of the disease and its side effects as a result of drug interactions. This highlights the importance of controlling and managing prescription drugs for patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, Prevalence, COVID-19, Meta-analysis, Increased morbidity and mortality

Background

COVID-19, originating from the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), appeared in December 2019 and quickly became a global pandemic [1, 2]. Despite the rapid spread of the disease, among 81% of patients, symptoms are mild and are usually treated at home [3]. Clinical manifestations of the disease range from asymptomatic to severe respiratory failure and death [4]. The most common symptoms of COVID-19 are fever and cough that occurs along with other symptoms such as dyspnoea, headache, muscle soreness, and fatigue [5, 6]. Although various drugs have been proven to treat COVID-19 disease in various clinical studies, there is no antiviral treatment with proven efficacy for COVID-19 patients [7].

Estimates show that more than 65% of adults over the age of 70 are at risk of severe COVID-19 infection [8]. A wide range of factors have been identified that affect the prognosis of COVID-19, including age, sex, ethnicity, and physical factors such as weight, body mass index, long-term conditions such as blood pressure, diabetes and stress [2]. Another case that is known as a health threat in particular among the older patients is polypharmacy [9].

Polypharmacy has traditionally been defined in various texts as the use of five or more chronic drugs, the use of inappropriate drugs, or drugs that are not clinically authorized [10]. Polypharmacy includes not only prescription drugs, but also over-the-counter and herbal medicines [11]. Polypharmacy often occurs among the elderly [12]. Polypharmacy in the elderly is a global problem that has recently worsened [13]. prevalence of polypharmacy ranges from 4 to 96.5% among community-dwelling older people to in hospitalized older people patients [14].

Polypharmacy due to its association with adverse health outcomes, including falls, functional impairment, drug adverse reactions, increased length of hospital stay, readmission, and mortality, is one of the important healthcare issues [12]. Numerous factors associated with polypharmacy, such as drug–drug interactions, drug–disease interactions, or potentially inappropriate prescriptions, may be involved in these adverse outcomes [12–14]. Polypharmacy is also a major factor in causing drug side effects before, during and after COVID-19 treatments [9]. In other words, polypharmacy can increase the risk of adverse drug events during COVID-19 treatment [7–9]. This may indicate that medications that may be helpful in treatment are not only not helpful in the event of drug side effects, but also delay treatment [7–9].

A systematic review by Iloanusi et al. [8] on the effect of polypharmacy on clinical outcomes in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) has been performed and no meta-analysis has been performed to evaluate the overall prevalence of polypharmacy and therefore this study can improve it. .

Given the above, effective drug management is very important for treating COVID-19 patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19, using a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

PROSPERO

This protocol has been registered in the Prospective Registry of Systematic Review database (CRD42021281552).

Study approach and research question

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA2020) and Cochran review approach. The stages in the systematic review process include: selecting a research question, determining inclusion and exclusion criteria, identifying articles, selecting studies, evaluating study quality, extracting data, and analysing and interpreting findings [15].

Our study aimed to answer the following research question “What is the global prevalence of polypharmacy among COVID-19 patients?” The study population (Population) includes: patients with COVID-19 worldwide, Outcome include: Prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19, Time period duration for the search includes: no lower time limit and until June 22, 2022, and study type (study design) includes: observational (case control, cohort, cross sectional).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Observational studies (case–control, cohort, cross-sectional) that have examined the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 have been published in English, and their full text which was available and also includes the information in Table 1, study type, prevalence, mean age and sample size were eligible for inclusion in the study. Intervention and clinical trial, reviews including systematic review and meta-analysis were excluded.

Table 1.

Search strategy for each database

| Database | Search strategy | Date | Number of publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed |

#1: (((((COVID-19[MeSH Terms]) OR ("SARS-CoV-2 Infection")) OR ("2019 Novel Coronavirus Infection")) OR ("2019 nCoV Disease")) OR ("Coronavirus Disease 2019")) OR (Coronavirus) #2: Polypharmacy [MeSH Terms] #3: (((Polypharmacy) OR (poly medication)) OR ("multiple drugs")) OR ("Potentially inappropriate medications") #4: (((((Outcome) OR (Mortality)) OR (death)) OR (morbidity)) OR (complication)) OR ("drug interactions") #5: #1 AND (#2 OR #3) AND #4 |

2022.6.22 | 143 |

| Web of science |

#1: ALL = (Polypharmacy OR polymedication OR "multiple drug" OR "Potentially inappropriate medications") #2: ALL = (Outcome OR Mortality OR death OR morbidity OR complication OR "drug interactions") #3: TS = ("COVID-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2 Infection" OR "2019 Novel Coronavirus Infection" OR "2019 nCoV Disease" OR "Coronavirus Disease 2019" OR Coronavirus) #4: #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

2021.6.22 | 68 |

| Scopus |

#1: TITLE-ABS-KEY ("COVID-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2 Infection" OR "2019 Novel Coronavirus Infection" OR "2019 nCoV Disease" OR "Coronavirus Disease 2019" OR coronavirus) #2: ALL (outcome OR mortality OR death OR morbidity OR complication OR "drug interactions") #3: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((polypharmacy OR polymedication OR "multiple drug" OR "Potentially inappropriate medications") #4: #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

2021.6.22 | 252 |

| Embase |

#1: ‘covid 19’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sars-cov-2 infection’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘2019 novel coronavirus infection’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘2019 ncov disease’:ab,kw OR 'coronavirus disease 2019':ti,ab,kw OR coronavirus:ti,ab,kw #2: polypharmacy:de #3: polypharmacy:ti,ab,kw OR polymedication:ti,ab,kw OR 'multiple drug':ti,ab,kw OR 'potentially inappropriate medications':ti,ab,kw #4: outcomes:ti,ab,kw OR mortality:ti,ab,kw OR death:ti,ab,kw OR morbidity:ti,ab,kw OR complication:ti,ab,kw OR 'drug interactions':ti,ab,kw #5: #2 OR #3 #6: #1 AND #4 AND #5 |

2021.6.20 | 138 |

| ScienceDirect | Title, abstract or author-specified keywords (COVID-19 OR "sars-cov-2") AND (Polypharmacy OR polymedication OR "multiple drug" OR "Potentially inappropriate medications") | 2021.6.22 | 38 |

| ProQuest |

#1: (Polypharmacy OR polymedication OR "multiple drug" OR "Potentially inappropriate medications") #2: (Outcome OR Mortality OR death OR morbidity OR complication OR "drug interactions") #3: TI,AB("COVID-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2 Infection" OR "2019 Novel Coronavirus Infection" OR "2019 nCoV Disease" OR "Coronavirus Disease 2019" OR Coronavirus) #4: #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

2021.6.22 | 389 |

Search strategy, and article identification

Systematic search of documents in international databases was performed with selected keywords. The search process was carried out for ScienceDirect, Web of Science (WoS), ProQuest, Embase, Medline (PubMed), and Scopus reference management databases. The Google Scholar search engine was also searched to ensure the comprehensiveness of the search process. Gray Literature, i.e. studies that their results have not been published were also examined within related databases and also by searching the reference lists of identified studies.

Keywords were extracted from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database. Keywords related to the studied population (P) were: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, 2019-ncov infection and outcome-related keywords (O) were: polypharmacy, drug interaction, potentially inappropriate medications, mortality, morbidity, outcomes based on Mesh browser. The search strategy in each database was determined by using the Advanced Search option and using all possible keyword combinations with the help of AND, and OR operators (Table1). The characteristics of the extracted studies are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the selected studies

| First author | Year of publication | Country | Definition of polypharmacy | Study design | Participants | Mean age (SD) | Patients with poly pharmacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bağ Soytaş [19] | 2021 | Turkey | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 218 | 75.3 | 108 |

| Bayrak [20] | 2022 | Turkey | ≥ 5 | Prospective study | 122 | 73 | 59 |

| Cantudo-Cuenca [21] | 2021 | Spain | ≥ 5 | observational study | 174 | 67 | 92 |

| Carrillo-Garcia [22] | 2021 | Spain | ≥ 5 | Longitudinal study | 165 | 88.5 | 112 |

| Couderc [23] | 2021 | France | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 480 | 88 | 348 |

| Crescioli [17] | 2021 | Italy | > 5 | Case series | 23 | 76.1 (14.40) | 16 |

| De Smet [24] | 2020 | Belgium | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 81 | 85 | 52 |

| Gavin et al. [25] | 2020 | America | ≥ 5 | Retrospective chart review | 140 | 60 | NR |

| Kananen et al. [26] | 2021 | Sweden | ≥ 5 | observational study | 1409 | 83(12) | NR |

| Klanidhi [27] | 2022 | India | ≥ 5 | Prospective study | 60 | 68.76 | 23 |

| Laosa [28] | 2020 | Spain | ≥ 5 | Prospective study | 375 | 66.06 | 77 |

| Lim et al. [29] | 2021 | Singapore | ≥ 4 | Observational study | 275 | 59 (54–66) | 73 |

| Lozano-Montoya [30] | 2021 | Spain | ≥ 5 | Longitudinal study | 300 | 86.3 | 213 |

| Manjhi [31] | 2021 | India | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 200 | > 40 | 142 |

| Mannucci [18] | 2022 | Italy | ≥ 5 | Observational study | 48,148 | NR | 7464 |

| McKeigue et al. [32] | 2021 | Scotland | ≥ 5 | Matched case control | 4251 | 0–75, ≥ 75 | NR |

| McQueenie et al. 1 [2] | 2020 | England | 4–6 | Retrospective study | 1324 | 48–86 | 298 |

| McQueenie et al. 2 [2] | 2020 | England | 6–9 | Retrospective study | 1324 | 48–86 | 130 |

| McQueenie et al. 3 [2] | 2020 | England | > 10 | Retrospective study | 1324 | 48–86 | 72 |

| Poblador-Plou [33] | 2020 | Spain | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 4412 | 67.7 | 1429 |

| Rodriguez-Sanchez [34] | 2021 | Spain | 5_9 | Cohort study | 499 | 86.7 | 200 |

| Rodriguez-Sanchez [34] | 2021 | Spain | > 10 | Cohort study | 499 | 86.7 | 163 |

| Sirois 1 [35] | 2022 | Canada | 5–9 | Population-based study | 32,476 | 79.59 | 9579 |

| Sirois 2 [35] | 2022 | Canada | 10–14 | Population-based study | 32,476 | 79.59 | 8619 |

| Sirois 3 [35] | 2022 | Canada | 15–19 | Population-based study | 32,476 | 79.59 | 5009 |

| Sirois 4 [35] | 2022 | Canada | ≥ 20 | Population-based study | 32,476 | 79.59 | 3746 |

| Sun et al. [36] | 2020 | China | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 217 | 45.7 (16.6) | NR |

| Taher [37] | 2020 | Bahrain | ≥ 5 | Retrospective study | 73 | 54 | 43 |

In order to access the latest published studies, an alert was created on a number of important databases, including PubMed and Scopus, to check if any new article was published during the study. Also, in order to access all related studies, the sources of articles that met the inclusion criteria were manually reviewed. To avoid errors and mistakes, all steps of article search, study selection, quality evaluation and data extraction were performed by two reviewers (researchers) independently. For this purpose, the information of all articles found in each database was transferred into the EndNote X8 references management software. After completing the search in all the databases, duplicate articles were removed. If there was a difference of opinion between the researchers regarding the inclusion of the article in the study, in order to avoid the risk of bias for specific studies, a final agreement was reached first through discussion and in some cases with the participation and opinion of a third reviewer.

Quality evaluation of observational studies

The quality of articles was assessed based on selected and related items of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist. The items on the checklist include: study design, background, place and time of study, outcome, inclusion criteria, sample size and statistical analysis. The NOS sets a maximum of 9 points for the lowest risk of bias in three areas: four points for selection of study groups; (2) two points for comparison of groups and three points for determining the amount of exposure and results for case and group studies. Based on this, we considered articles with a score of 7 and above as high-quality articles [16].

Data extraction

After selecting the studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis process, the data were extracted, and the studies were summarized. An electronic checklist was prepared for this purpose. The items in the checklist include: surname of the first author, year of publication and year of study, place of study, age, sample size, total number of people with COVID-19, number of people with polypharmacy. Other distinct checklists were used to extract data different sections: one checklist was designed to extract statistical data (for meta-analysis), one checklist was designed to extract characteristics of the articles (for complete review and also for component analysis). Also, to increase the accuracy of the work, articles that the target population with an underlying disease, and articles that the study population did not have a specific underlying disease, were separated and extracted with different checklists and then patients with underlying disease were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

To analyse and combine the results of different studies, in each study, data about treatment methods and other small values were considered as binominal probability and its variance was calculated through binominal distribution. Heterogeneity of studies was assessed using the I2 test. Publication bias was assessed the Egger’s test and corresponding funnel plots were drawn. Data were analysed within Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2).

Results

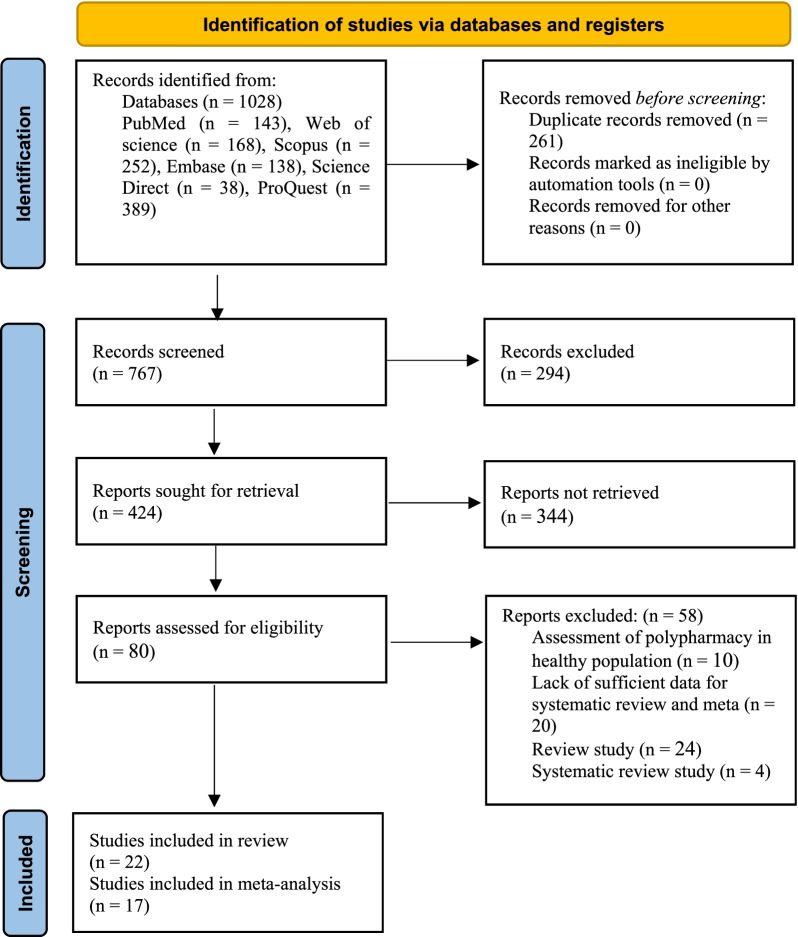

After a systematic search of the specified databases, a total of 1028 articles were identified and entered into EndNote. After deleting 261 duplicate articles, the titles and abstracts of 767 articles were reviewed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 80 articles remained for the secondary evaluation and further review. At this stage, the full text of the articles was reviewed in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and finally 22 articles were approved and entered the systematic review process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection

All studies were conducted in 2020 and 2022. Of the 22 confirmed studies, 14 were conducted in continental Europe. Of these studies, 5 were conducted in Spain. The other 9 were conducted in Belgium, Scotland, Italy, the United Kingdom, Turkey, France, and Sweden. Other studies were conducted in Asia and the Americas. Among these, 3 studies took place in Bahrain, China, India, and Singapore and another study was conducted in the United States, and Canada.

Among the studies performed, 17 pieces of research were retrospective, prospective, and longitudinal, one study, case series and the only remaining study being a case control. In these studies, a total of 95,422 people were studied. Least participant was in the study by Crescioli et al. [17] with 23 people and the most participants were reported in the study of Mannucci et al. [18] with 48,148 people (Table 2).

Prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19

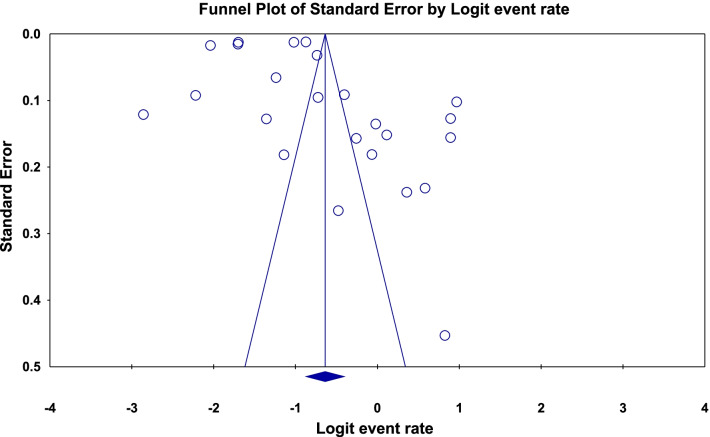

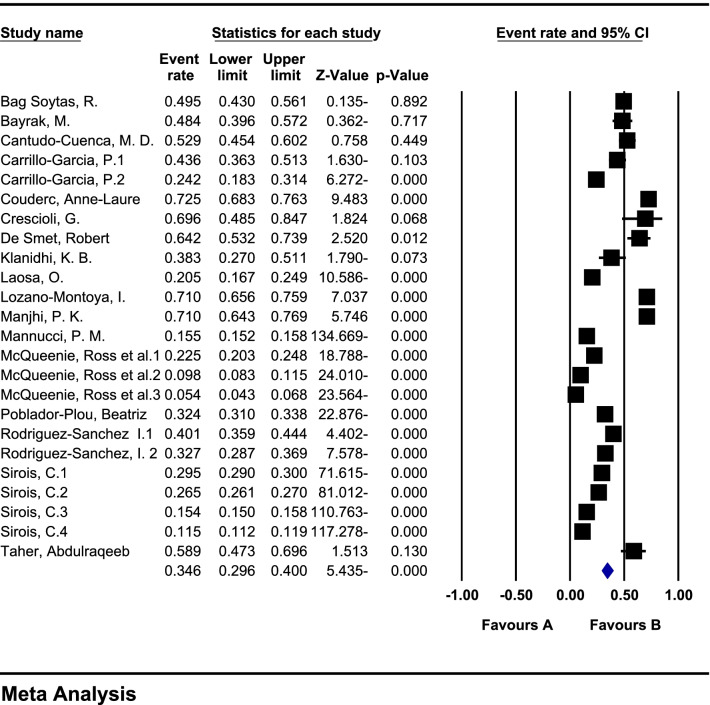

In a review of 17 studies with a sample size of 189,870 patients with COVID-19, the heterogeneity of the studies was evaluated based on the I2 test (I2: 99.6) and based on the high heterogeneity in the studies, the random effects method was used to analyse the studies. Publication bias was not significant in the studies (p = 0.183) (Fig. 2). The overall prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 based on meta-analysis was reported to be 34.6% (95% CI: 29.6–40) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot diagram on the publication bias among the studies

Fig. 3.

Forest plot and general meta-analysis of the results of studies based on random effects method

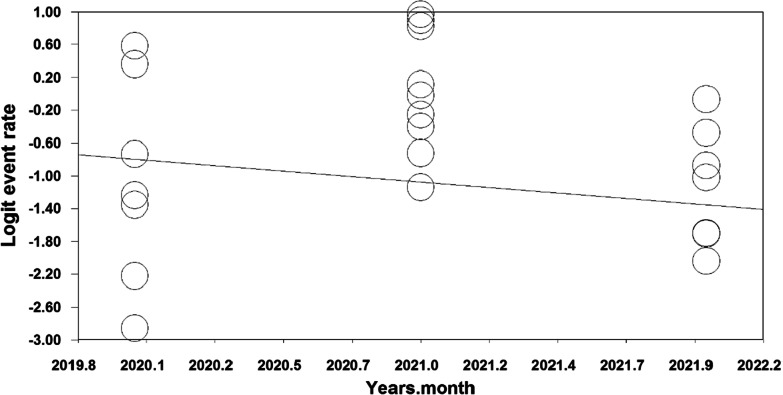

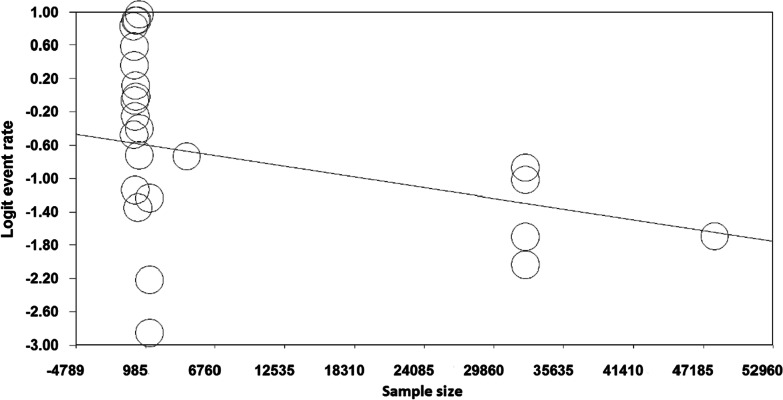

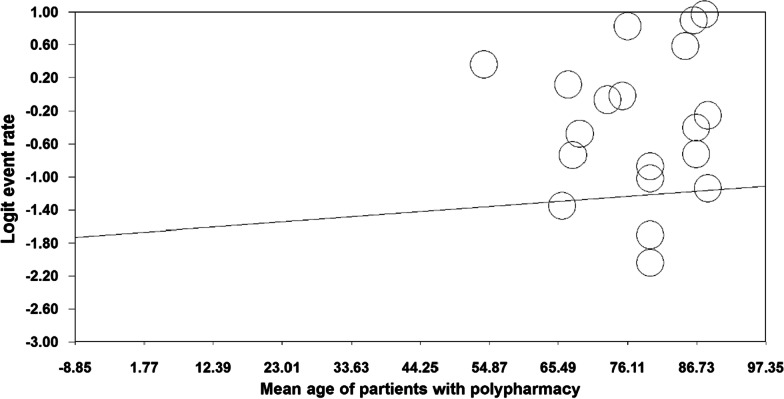

The results of the meta-regression analysis based on sample size, year of study and age of study participants also showed that with increasing year of study (month), the prevalence of polypharmacy in COVID-19 patients decreased (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4), With increasing sample size, the prevalence of polypharmacy in COVID-19 patients decreased (p = 0.07) (Fig. 5). As the age of patients with COVID-19 increased, the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 increased (p = 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Meta-regression diagram of the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 by year of study (month)

Fig. 5.

Meta-regression of the prevalence of polypharmacy in COVID-19 patients by sample size

Fig. 6.

Meta-regression diagram of the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 by age of study participants

In Table 3, subgroup analysis was performed based on the number of drugs as well as the patient’s condition after treatment, and it was reported that the highest prevalence of polypharmacy was in patients with COVID-19 treated with 4–9 drugs with a prevalence of 26.8 (95% CI: 18.5–37.1) and also polypharmacy in patients who did not survive after treatment with a prevalence of 54.8 (95% CI: 45.4–63.9) was higher (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of results by number of drugs and status of patients with COVID-19 after treatment

| Subgroup | N | Sample size | Heterogeneity (I2) | Egger test | Prevalence (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypharmacy by drug number | 4–9 | 5 | 35,788 | 98.5 | 0.631 | 26.8 (95% CI: 18.5–37.1) |

| > 10 | 6 | 99,416 | 99.8 | 0.751 | 17.1 (95% CI: 11.6–24.3) | |

| Patient status after treatment | Survivors | 9 | 5490 | 98.2 | 0.144 | 42.1 (95% CI: 28.9–56.6) |

| Non-survivors | 9 | 1508 | 88.3 | 0.972 | 54.8 (95% CI: 45.4–63.9) | |

Association of polypharmacy with increasing disease severity and mortality

Polypharmacy is a common issue among the elderly. This problem was also observed in patients with COVID-19, as the study of Sun et al. [36] reported that with increasing age, the drugs used in patients with COVID-19 also increased. Studies have shown that polypharmacy is associated with increased side effects. A study by Taher et al. [37] showed that an increase in polypharmacy is associated with an increase in acute kidney injury. McQueenie et al. [2] study also showed that polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 was associated with an increase in disease severity, which was statistically significant. This result was also observed in the study of McKeigue et al. [32].

The study by Lim et al. [29] also emphasized that the prevalence of polypharmacy increases with the age of patients with COVID-19. In the study by Mannucci et al. [18] showed that polypharmacy was lower in patients at home than in hospitalized patients. Patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) showed the highest exposure to polypharmacy. On the other hand, it was observed that the number of patients exposed to polypharmacy in the ICU during the corona pandemic was significantly higher than this amount before the outbreak. The study by Sirois et al. [35] also showed that polypharmacy increases the risk of hospitalization and even mortality from the disease.

The relationship between polypharmacy and increased mortality has also been investigated in some studies. According to the results of 6 studies [19, 20, 28, 33–35], with increasing polypharmacy in the selected samples, mortality due to COVID-19 also increases, which is statistically significant. However, in 2 other studies [26, 30], it was stated that the increase in medications used did not have a significant effect on the increase in mortality caused by COVID-19.

Only in one study [22] was it observed that polymedication for the control and treatment of diseases that existed before the onset of COVID-19 had a protective effect on mortality and reduced mortality due to COVID-19.

In addition, the study by Gavin et al. [25] reported that polypharmacy had no significant relationship with the need for ventilator respiratory support. In this study, there was no statistical difference between people who improved after connecting to a ventilator and people who died after connecting to a ventilator.

Discussion

The present study was conducted for the first time with the aim of investigating the prevalence of polypharmacy among patients with COVID-19 globally, by a systematic review. The results of this study showed that 34.6% of patients with COVID-19 had polypharmacy. The results of meta-regression also showed that with the increase of the study year, polypharmacy studies decreased. Also, based on the sample size of the study, meta-regression indicated that the prevalence of polypharmacy decreased with the increase in the number of participants in the study and additionally, as the age of patients with COVID-19 increased, the prevalence of polypharmacy in patients with COVID-19 increased. This may be due to the nature of COVID-19 disease and its greater impact on the elderly, which requires the use of more drugs to treat COVID-19 in the elderly.

In the case of prescribing inappropriate medicine for the person, the incidence of side effects associated with the use of inappropriate drugs increases [38]. In other words, it seems necessary to maintain the quality of life of some elderly impacted by polypharmacy, however inappropriate drugs may be associated with side effects that increase the burden of disease among the elderly [39].

The most vulnerable patients to COVID-19 are the elderly and patients with underlying problems such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer. These patients are typically exposed to a large number of medications during the day. A study by Al Rihani et al. looked at the elderly with underlying diseases, and found that participants in the study took an average of about 11 different medications during the day. This increases the incidence of drug interactions and adverse drug events. In addition to being more prone to COVID-19, these patients are more likely to experience associated side effects. However, the risk of using any of the COVID-19 recommended drugs in such elderly people with polypharmacy is still high, yet no previous study on the concept has been conducted [40].

Along with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the increase in the incidence of this disease, polypharmacy increased in patients with COVID-19, especially in older population. This is justified by the fact that there is no definitive cure for the disease. Also, the widespread side effects of COVID-19 increase the need for symptomatic treatments in individuals, which is also effective in increasing the use of various drugs. Other studies have confirmed the rise in polypharmacy in adults with COVID-19. A study by Nwanaji-Enwerem et al. Reported that in Africa, polypharmacy is a growing health threat as the population ages and the prevalence of several diseases increases, the effects of polypharmacy in Africa can be mitigated by strengthening training in evidence-based prescribing and joint decision-making [41]. Research works in previous epidemics have also shown that patients with polypharmacy are more likely to develop the disease and increase side effects [42, 43].

Studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis have shown that polypharmacy is associated with an increase in adverse side effects such as acute kidney injury, adverse drug reaction, increased severity of COVID-19 and increased mortality due to this disease [8]. With increasing polypharmacy, the incidence of drug interactions in patients also increases. One study found that COVID-19 patients admitted to medical facilities were at high risk for drug interactions. Treatments to control infection in these patients, including concomitant treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine, significantly increase drug interactions [44]. As the complexity of medication regimens increases, so does the pressure on healthcare systems. Medication errors with inappropriate drugs significantly increase the risk of adverse consequences. The incidence of aging syndromes, including falls and delirium, previously exacerbated by polypharmacy, is accelerated by COVID-19 treatments. And their management will be more difficult because infection control is a priority in patients with COVID-19 [45]. Therefore, physicians should manage the risk of drug interactions when prescribing new drugs to treat and control the symptoms of COVID-19 [46].

Strength and limitations

The most important strength of this study is the updated search to June 2022 and the use of all databases to increase the accuracy and sensitivity of the study, and the most important limitation of this study is the lack of proper definition of polypharmacy in some studies and not mentioning the number of drugs used for patients in these studies.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that polypharmacy is highly prevalent among patients with COVID-19, especially among the elderly. It has also been observed that adverse outcomes such as renal problems, drug interactions, increased risk and severity of COVID-19, and increased mortality in people with polypharmacy are more common than others.

Acknowledgements

By the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- MESH

Medical Subject Headings

- WoS

Web of Science

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Author contributions

MM and NS contributed to the design, MM statistical analysis, participated in most of the study steps. MM and HGH and ND prepared the manuscript. AHF and MM and HGH and ND and HA assisted in designing the study, and helped in the, interpretation of the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hooman Ghasemi, Email: humanghasemi2010@gmail.com.

Niloofar Darvishi, Email: darvishi.niloufar@gmail.com.

Nader Salari, Email: n_s_514@yahoo.com.

Amin Hosseinian-Far, Email: amin.hosseinian-far@northampton.ac.uk.

Hakimeh Akbari, Email: anaakbari91@gmail.com.

Masoud Mohammadi, Email: Masoud.mohammadi1989@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M, Gabbiadini R, Spadaccini M, Anderloni A, Carrara S, Fugazza A, Di Leo M, Galtieri PA, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(1):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQueenie R, Foster HME, Jani BD, Katikireddi SV, Sattar N, Pell JP, Ho FK, Niedzwiedz CL, Hastie CE, Anderson J, et al. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and COVID-19 infection within the UK Biobank cohort. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.of the International CSG The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J, Ji P, Pang J, Zhong Z, Li H, He C, Zhang J, Zhao C. Clinical characteristics of 3062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1902–1914. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, Diao K, Lin B, Zhu X, Li K, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295(3):200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meo SA, Klonoff DC, Akram J. Efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(8):4539–4547. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, Fu S, Gao L, Cheng Z, Lu Q, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iloanusi S, Mgbere O, Essien EJ. Polypharmacy among COVID-19 patients: a systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2021;61(5):e14–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potempski F, Bilimoria K: Polypharmacy in the age of COVID-19: medication management during a pandemic. University of Toronto Medical Journal 2021, 98(1).

- 10.Antimisiaris D, Cutler T. Managing Polypharmacy in the 15-Minute Office Visit. Prim Care. 2017;44(3):413–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnjidic D, Hilmer S, Blyth F, Naganathan V, Cumming R, Handelsman D, McLachlan A, Abernethy D, Banks E, Le Couteur D. High-risk prescribing and incidence of frailty among older community-dwelling men. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):521–528. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez-Valencia M, Izquierdo M, Cesari M, Casas-Herrero A, Inzitari M, Martinez-Velilla N. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(7):1432–1444. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Parish AL. Polypharmacy and medication management in older adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52(3):457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pazan F, Wehling M. Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(3):443–452. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2021, 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lo CK-L, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crescioli G, Brilli V, Lanzi C, Burgalassi A, Ieri A, Bonaiuti R, Romano E, Innocenti R, Mannaioni G, Vannacci A, et al. Adverse drug reactions in SARS-CoV-2 hospitalised patients: a case-series with a focus on drug-drug interactions. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(3):697–710. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02586-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannucci PM, Nobili A, Tettamanti M, D'Avanzo B, Galbussera AA, Remuzzi G, Fortino I, Leoni O, Harari S. Impact of the post-COVID-19 condition on health care after the first disease wave in Lombardy. J Intern Med 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bag Soytas R, Unal D, Arman P, Suzan V, Emiroglu Gedik T, Can G, Korkmazer B, Karaali R, Borekci S, Kuskucu MA, et al. Factors affecting mortality in geriatric patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51(2):454–463. doi: 10.3906/sag-2008-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayrak M, Cadirci K. The associations of life quality, depression, and cognitive impairment with mortality in older adults with COVID-19: a prospective, observational study. Acta Clin Belg. 2022;77(3):588–595. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2021.1916687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantudo-Cuenca MD, Gutierrez-Pizarraya A, Pinilla-Fernandez A, Contreras-Macias E, Fernandez-Fuertes M, Lao-Dominguez FA, Rincon P, Pineda JA, Macias J, Morillo-Verdugo R. Drug-drug interactions between treatment specific pharmacotherapy and concomitant medication in patients with COVID-19 in the first wave in Spain. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12414. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91953-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrillo-Garcia P, Garmendia-Prieto B, Cristofori G, Montoya IL, Hidalgo JJ, Feijoo MQ, Cortes JJB, Gomez-Pavon J. Health status in survivors older than 70 years after hospitalization with COVID-19: observational follow-up study at 3 months. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(5):1091–1094. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00516-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couderc AL, Correard F, Hamidou Z, Nouguerede E, Arcani R, Weiland J, Courcier A, Caunes P, Clot-Faybesse P, Gil P, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths in French nursing homes. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2021;22(8):1581–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Smet R, Mellaerts B, Vandewinckele H, Lybeert P, Frans E, Ombelet S, Lemahieu W, Symons R, Ho E, Frans J, et al. Frailty and mortality in hospitalized older adults with COVID-19: retrospective observational study. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2020;21(7):928–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gavin W, Campbell E, Zaidi SA, Gavin N, Dbeibo L, Beeler C, Kuebler K, Abdel-Rahman A, Luetkemeyer M, Kara A. Clinical characteristics, outcomes and prognosticators in adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kananen L, Eriksdotter M, Bostrom AM, Kivipelto M, Annetorp M, Metzner C, Back Jerlardtz V, Engstrom M, Johnson P, Lundberg LG et al. Body mass index and Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form as predictors of in-geriatric hospital mortality in older adults with COVID-19. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Klanidhi KB, Chakrawarty A, Bhadouria SS, George SM, Sharma G, Chatterjee P, Kumar V, Vig S, Gupta N, Singh V, et al. Six-minute walk test and its predictability in outcome of COVID-19 patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):58. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_544_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laosa O, Pedraza L, Alvarez-Bustos A, Carnicero JA, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Rodriguez-Manas L. Rapid assessment at hospital admission of mortality risk from COVID-19: the role of functional status. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2020;21(12):1798–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim JP, Low KYH, Lin NJJ, Lim CZQ, Ong SWX, Tan WYT, Tay WC, Tan HN, Young BE, Lye DCB, et al. Predictors for development of critical illness amongst older adults with COVID-19: beyond age to age-associated factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;94:104331. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozano-Montoya I, Quezada-Feijoo M, Jaramillo-Hidalgo J, Garmendia-Prieto B, Lisette-Carrillo P, Gomez-Pavon FJ. Mortality risk factors in a Spanish cohort of oldest-old patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in an acute geriatric unit: the OCTA-COVID study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(6):1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00541-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manjhi PK, Kumar R, Priya A, Rab I. Drug-drug interactions in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study at a tertiary care Hospital in Eastern India. Maedica. 2021;16(2):163–169. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2021.16.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKeigue PM, Kennedy S, Weir A, Bishop J, McGurnaghan SJ, McAllister D, Robertson C, Wood R, Lone N, Murray J, et al. Relation of severe COVID-19 to polypharmacy and prescribing of psychotropic drugs: the REACT-SCOT case-control study. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01907-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poblador-Plou B, Carmona-Pirez J, Ioakeim-Skoufa I, Poncel-Falco A, Bliek-Bueno K, Cano-Del Pozo M, Gimeno-Feliu LA, Gonzalez-Rubio F, Aza-Pascual-Salcedo M, Bandres-Liso AC, et al. Baseline chronic comorbidity and mortality in laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases: results from the PRECOVID study in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5171. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Sanchez I, Redondo-Martin M, Furones-Fernandez L, Mendez-Hinojosa M, Chen-Chim A, Saavedra-Palacios R, Gil-Gregorio P. Functional, clinical, and sociodemographic variables associated with risk of in-hospital mortality by COVID-19 in people over 80 years old. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(8):964–970. doi: 10.1007/s12603-021-1664-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirois C, Boiteau V, Chiu Y, Gilca R, Simard M. Exploring the associations between polypharmacy and COVID-19-related hospitalisations and deaths: a population-based cohort study among older adults in Quebec, Canada. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e060295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun J, Deng X, Chen X, Huang J, Huang S, Li Y, Feng J, Liu J, He G. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in COVID-19 patients in china: an active monitoring study by hospital pharmacovigilance system. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(4):791–797. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taher A, Alalwan AA, Naser N, Alsegai O, Alaradi A. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19 pneumonia: a single-center experience in Bahrain. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9693. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman S, Singh K, Dhingra S, Charan J, Sharma P, Islam S, Jahan D, Iskandar K, Samad N, Haque M. The Double Burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and polypharmacy on geriatric population—public health implications. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:1007–1022. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S272908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh J, Abukabda AB, Razzaque MS. COVID-19 pandemic: Non-pharmaceutical interventions and addressing polypharmacy for better clinical outcome. Adv Human Biol. 2021;11(2):143. doi: 10.4103/aihb.aihb_36_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al Rihani SB, Smith MK, Bikmetov R, Deodhar M, Dow P, Turgeon J, Michaud V. Risk of adverse drug events following the virtual addition of COVID-19 repurposed drugs to drug regimens of frail older adults with polypharmacy. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2591. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nwanaji-Enwerem JC, Boyer EW, Olufadeji A. Polypharmacy exposure, aging populations, and COVID-19: considerations for healthcare providers and public health practitioners in Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greene M, Steinman MA, McNicholl IR, Valcour V. Polypharmacy, drug–drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):447–453. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hak E, Verheij TJ, van Essen GA, Lafeber AB, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Prognostic factors for influenza-associated hospitalization and death during an epidemic. Epidemiol Infect. 2001;126(2):261–268. doi: 10.1017/S0950268801005180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cattaneo D, Pasina L, Maggioni AP, Giacomelli A, Oreni L, Covizzi A, Bradanini L, Schiuma M, Antinori S, Ridolfo A. Drug–drug interactions and prescription appropriateness in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective analysis from a reference hospital in Northern Italy. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(12):925–933. doi: 10.1007/s40266-020-00812-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ailabouni NJ, Hilmer SN, Kalisch L, Braund R, Reeve E. COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for safe medication use in older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. In., vol. 76: Oxford University Press US; 2021: 1068–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Surmelioglu N, Yalcin N, Kuscu F, Candevir A, Inal AS, Komur S, Kurtaran B, Demirkan K, Tasova Y. Physicians’ knowledge of potential COVID-19 drug-drug interactions: an online survey in turkey. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(2):237–241. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1807809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.