Abstract

Nitrogen fixation is tightly regulated in Rhodospirillum rubrum at two different levels: transcriptional regulation of nif expression and posttranslational regulation of dinitrogenase reductase by reversible ADP-ribosylation catalyzed by the DRAT-DRAG (dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase–dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase) system. We report here the characterization of glnB, glnA, and nifA mutants and studies of their relationship to the regulation of nitrogen fixation. Two mutants which affect glnB (structural gene for PII) were constructed. While PII-Y51F showed a lower nitrogenase activity than that of wild type, a PII deletion mutant showed very little nif expression. This effect of PII on nif expression is apparently the result of a requirement of PII for NifA activation, whose activity is regulated by NH4+ in R. rubrum. The modification of glutamine synthetase (GS) in these glnB mutants appears to be similar to that seen in wild type, suggesting that a paralog of PII might exist in R. rubrum and regulate the modification of GS. PII also appears to be involved in the regulation of DRAT activity, since an altered response to NH4+ was found in a mutant expressing PII-Y51F. The adenylylation of GS plays no significant role in nif expression or the ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase, since a mutant expressing GS-Y398F showed normal nitrogenase activity and normal modification of dinitrogenase reductase in response to NH4+ and darkness treatments.

Biological nitrogen fixation is catalyzed by the nitrogenase complex, which consists of two proteins: dinitrogenase (also referred to as MoFe protein) and dinitrogenase reductase (also referred to as Fe protein) (7). Dinitrogenase is an α2β2 tetramer of the nifDK gene products and contains the active site (FeMo-co) for reduction of N2, C2H2, and other substrates. Dinitrogenase reductase is an α2 dimer of the nifH gene product and is the unique electron donor to dinitrogenase. This biological process is very energy demanding and is thus tightly controlled.

In all studied nitrogen-fixing bacteria, nitrogen fixation is regulated at the transcriptional level. Transcriptional regulation has been best studied in Klebsiella pneumoniae, a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium, and it involves the general nitrogen regulation (ntr) system (47). This ntr regulatory system has also been intensively studied in Escherichia coli (52), and it has been successfully reconstituted in vitro (25–28). This regulatory system involves the products of at least five genes: ntrA, ntrB, ntrC, glnB, and glnD. glnD encodes a bifunctional, uridylyltransferase–uridylyl-removing enzyme (UTase-UR) that is believed to be the sensor of the intracellular concentration of glutamine in the cell. UTase-UR reversibly controls the activity of the PII protein (the gene product of glnB) by uridylylation or deuridylylation (46, 52). PII was recently found to be responsible for the sensing of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) in E. coli (32), and its roles are described below. The products of ntrB and ntrC belong to the family of two-component regulators. NtrB (NRII) is a histidine kinase that phosphorylates NtrC (NRI) under nitrogen-limiting conditions and also can act as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate NtrC under nitrogen-excess conditions. Both kinase and phosphatase activities of NtrB are regulated by PII in response to the level of α-KG in the cell (25). The phosphorylated form of NtrC acts as a transcriptional activator of nifA (encoding an activator for other nif genes), glnA (encoding glutamine synthetase [GS]), and other operons involved in nitrogen assimilation. ntrA (also referred to as rpoN) encodes a specific sigma factor, ς54. Under limiting fixed nitrogen conditions, GlnD functions as UTase and uridylylates PII. The uridylylation of PII can stimulate kinase activity of NtrB to phosphorylate NtrC. The phosphorylated NtrC thus activates nifA expression. NifA then activates other nif operons, including nifHDK. Under nitrogen-excess conditions, the process is reversed and nif expression is repressed.

Besides the transcriptional regulation of nif expression, nitrogen fixation is also regulated at the posttranslational level in many diverse nitrogen-fixing bacteria, but it has been well characterized only in Rhodospirillum rubrum, Azospirillum brasilense, Azospirillum lipoferum, and Rhodobacter capsulatus, in which it involves reversible mono-ADP ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase (41, 67). Two enzymes perform this reversible reaction. Dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase (referred to as DRAT, the gene product of draT) carries out the transfer of the ADP-ribose from NAD to the Arg-101 residue of one subunit of the dinitrogenase reductase homodimer, resulting in inactivation of that enzyme. The ADP-ribose group attached to dinitrogenase reductase can be removed by another enzyme, dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase (referred to as DRAG, the gene product of draG), thus restoring nitrogenase activity.

The draTG genes have been cloned, sequenced, and physiologically characterized from R. rubrum, A. brasilense, A. lipoferum, and R. capsulatus (16, 22, 38, 42, 45, 68). The DRAT-DRAG system negatively regulates nitrogenase activity in response to exogenous NH4+ or to energy limitation in the form of darkness shifts (in the cases of R. rubrum and R. capsulatus) or anaerobiosis shifts (in A. brasilense) (38, 45, 66, 68).

The regulation of the ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase is effected through the posttranslational regulation of both DRAT and DRAG activities (67). Under nitrogen-fixing conditions, DRAT is inactive and DRAG is active. Following a negative stimulus such as exogenous NH4+ or energy depletion, DRAT is activated and DRAG becomes inactive, resulting in the loss of nitrogenase activity and the modification of dinitrogenase reductase. However, DRAT activation is only transient, and it becomes inactive again even in the continued presence of the negative stimulus. After removal of the negative stimulus, DRAG becomes active again, and it then reactivates dinitrogenase reductase by cleavage of the ADP-ribose group. However, detail of the mechanisms for the regulation of DRAT and DRAG activities are still unknown.

Because NH4+ not only represses nif expression but also stimulates the modification of dinitrogenase reductase, it is possible that these two regulatory systems might share some common signal transduction pathways. Unfortunately, the transcriptional regulation of nif expression has not been well studied in R. rubrum. Previous studies showed that NtrBC are not essential for nif expression in R. rubrum (69), indicating that R. rubrum has a different regulatory mechanism for nif expression than that seen in K. pneumoniae. The glnB has been cloned in R. rubrum, and it is cotranscribed with glnA from two different promoters: low-level expression from a putative ς70 promoter under high NH4+ conditions and high-level expression from a ς54 promoter under N2-fixing conditions (29). NtrC enhances the transcription of glnBA from its ς54 promoter (29). Consistent with this, an ntrBC deletion causes low levels of both GS activity and protein (69). PII in R. rubrum can be uridylylated in response to the change of nitrogen status in the cell (30). Efforts to create insertion mutations in glnB and glnA of R. rubrum have not been successful (29; Y. Zhang and G. P. Roberts, unpublished data), suggesting that they might be deleterious under the conditions used.

To further study the regulation of nitrogen fixation in R. rubrum, we have constructed and characterized glnB, glnA, and nifA mutants and describe here their relationship to the regulation of nif expression and to the function of the DRAT-DRAG system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (mg/liter): streptomycin (Sm), 100; kanamycin (Km), 12.5; nalidixic acid (Nx), 6; tetracycline (Tc), 1; gentamicin, (Gm) 10; and chloramphenicol (Cm), 5 (for R. rubrum); and ampicillin (Ap), 100; Km, 25; Gm, 5; Cm, 25; and Tc, 12.5 (for E. coli).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R. rubrum | ||

| UR2 | Wild type, Smr | 34 |

| UR214 | draG4::kan mutant, Smr Kmr | 38 |

| UR381 | ΔntrBC1 mutant, Smr Kmr | 69 |

| UR654 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pYPZ212, which is merodiploid for glnB (encoding wild type and PII-Y51F), Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR659 | glnB1 (PII-Y51F) mutant, resolving from UR654, Smr Kms | This report |

| UR686 | glnB1 (PII-Y51F) draG4::kan double mutant, Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR687 | glnA2 (GS-Y398F) mutant, Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR689 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pYPZ216, and which is merodiploid for glnB (wild type and deletion), Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR691 | nifA1 mutant, Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR694 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pCK3, Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR695 | Transconjugant of UR659 with pCK3, Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR696 | Transconjugant of UR686 with pCK3, Smr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR697 | Transconjugant of UR691 with pCK3, Smr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR698 | Transconjugant of UR214 with pCK3, Smr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR708 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pYPZ228, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR709 | Transconjugant of UR381 with pYP228, Smr Kmr Gmr | This report |

| UR710 | Transconjugant of UR659 with pYP228, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR711 | Transconjugant of UR691 with pYP228, Smr Kmr Gmr | This report |

| UR712 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pHRP309, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR713 | Transconjugant of UR381 with pHRP309, Smr Kmr Gmr | This report |

| UR714 | Transconjugant of UR659 with pHRP309, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR715 | Transconjugant of UR691 with pHRP309, Smr Kmr Gmr | This report |

| UR717 | ΔglnB3 mutant, resolving from UR689, Smr Kms | This report |

| UR720 | Transconjugant of UR717 with pCK3, Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR721 | Transconjugant of UR717 with pHRP309, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR722 | Transconjugant of UR717 with pYPZ228, Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR732 | ΔglnB3 draG4::kan double mutant, Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR733 | Transconjugant of UR732 with pCK3, Smr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR741 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pYPZ239, Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR742 | Transconjugant of UR659 with pYPZ239, Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR743 | Transconjugant of UR691 with pYPZ239, Smr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR744 | Transconjugant of UR717 with pYPZ239, Smr Tcr | This report |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJOM | pGEM-3Zf(−) derivative containing R. rubrum glnBA, Apr | 29 |

| pJHL201 | draG4::kan was cloned into pSUP202, Apr Kmr | 38 |

| pUX19 | Suicide vector for R. rubrum, Kmr | D. P. Lies and G. P. Robertsa |

| pRK404 | Broad-host-range plasmid, Tcr | 12 |

| pHRP309 | Broad-host-range lacZ transcriptional fusion vector, Gmr | 54 |

| pCK3 | pRK290 derivative containing K. pneumoniae nifA, Tcr | 35 |

| pYPZ201-1 | An ∼2.5-kb EcoRV fragment of glnBA from pJOM was subcloned into pUX19 at EcoRV-StuI sites, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ211 | Similar to pYPZ201-1, but it has glnA2 (GS-Y398F), Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ212 | Similar to pYPZ201-1, but it has glnB1 (PII-Y51F), Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ214 | EcoRV-HincII of glnA′ was deleted from pYPZ201-1, and it has the entire glnB and a small portion of glnA gene, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ215 | BamHI fragment of glnBA′ was deleted from pYPZ211, so that it has only a partial glnA2 (GS-Y398F), Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ216 | A 201-bp of internal region of glnB (ΔglnB3) was deleted from pYPZ214, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ217 | A 450-bp of PCR product of R. rubrum nifA′ was cloned into pBSKS(−), Apr | This report |

| pYPZ218 | A 800-bp of PCR product of R. rubrum nifA′ was cloned into pBSKS(−), Apr | This report |

| pYPZ219 | 450-bp nifA′ region from pYPZ217 was subcloned into pUX19, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ220-4 | A 2.5-kp fragment of R. rubrum nifA′ and 5′ region was cloned into pUX19, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ220-9 | A 9-kb fragment of R. rubrum nifA′ and 3′ region was cloned into pUX19, Kmr | This report |

| pYPZ224 | BamHI-SalI fragment of nifA′ and upstream region was cloned into pBSKS(−), Apr | This report |

| pYPZ228 | 500-kb NheI-KpnI fragment containing promoter of nifA from pYPZ224 was cloned into pHRP309 at XbaI-KpnI sites, Gmr | This report |

| pYPZ239 | A 3.8-kb fragment of R. rubrum nifAB′ was cloned into pRK404, Tcr | This report |

Unpublished data.

Growth conditions and whole-cell nitrogenase activity assay.

R. rubrum was grown in rich SMN medium (16) or in minimal (MN) medium containing 1 mg of NH4Cl per ml (37) or in malate-glutamate (MG) medium (37) for the derepression for nitrogenase. MN− was used for N2-fixing growth, and it is the same as MN, except that the NH4Cl is omitted. Whole-cell nitrogenase activity assay and darkness-NH4Cl treatments have been described previously (65).

Site-directed mutagenesis of glnB and glnA.

QuikChange method (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to generate PII-Y51F and GS-Y398F substitutions. pYPZ201-1 was used as the template, and it contains a 2.5-kb EcoRV fragment of R. rubrum glnBA cloned into pUX19, a suicide vector for R. rubrum. The pUX19 plasmid was derived from pUK21 (62) and contains an oriT fragment from pSU202 (57), constructed by D. P. Lies and G. P. Roberts (unpublished data). After mutagenesis, all mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids containing either mutated glnB1 or mutated glnA2 (encoding PII-Y51F or GS-Y398F) were named pYPZ212 and pYPZ211, respectively.

Construction of an R. rubrum strain expressing PII-Y51F.

pYZ212, containing mutagenized glnB1 (encoding PII-Y51F), was transformed into E. coli S17-1 (57) and then conjugated into R. rubrum by the method described previously (38). Smr Nxr Kmr R. rubrum colonies were selected, and a representative isolate was termed UR654. Since UR654 arose from a single crossover event, it is merodiploid for glnB in the chromosome, with both wild-type and mutant alleles. To obtain a strain with only the mutant allele, UR654 was grown in SMN with Nx (20 mg/ml) for more than 80 generations, plated on SMN plates, and Kms colonies were identified after replica printing. A total of 32 Kms colonies were found, at a frequency of 0.2%. About 50% of these contained the mutant glnB allele, as based on sequencing of PCR-amplified glnB, and a representative isolate was designated UR659.

To construct an R. rubrum glnB1 draG double mutant, plasmid pJHL201, containing draG4::kan (38), was conjugated into UR659. Smr Nxr Kmr R. rubrum colonies were selected, and replica printed to identify Cms colonies resulting from a double crossover event. The R. rubrum glnB1 draG4::kan mutant was named UR686.

Construction of an R. rubrum strain expressing GS-Y398F.

pYPZ211, containing glnB+ and glnA2 (encoding GS-Y398F), was digested with BamHI and then religated. This resulted in the removal of an approximately 770-bp fragment containing the entire glnB gene and part of glnA (but not that portion with the glnA2 mutation), yielding pYPZ215. pYPZ215 was transformed into E. coli S17-1 and then conjugated into R. rubrum, selecting Smr Nxr Kmr colonies. These transconjugants had only one functional copy of glnA (either wild-type or glnA2), because only a portion of glnA was present on the suicide vector. An isolate containing the desired glnA2 allele was identified by Western blot analysis with the antibody against R. rubrum GS as a strain that no longer displayed the adenylylated subunit of GS on Western blots of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels. Approximately 40% of isolates showed no modification of GS, and a representative isolate, expressing GS-Y398F, was designated UR687.

Construction of an in-frame deletion in glnB (ΔglnB3).

pYPZ201-1, containing R. rubrum glnBA, was digested with EcoRV and HincII and then religated, resulting in the deletion of most of glnA, yielding pYPZ214. pYPZ214 was then digested with PstI and BglII, which created an ∼200-bp deletion within glnB, and then treated with mung bean nuclease, which can create blunt ends of DNA and also can degrade double-stranded DNA ends at high enzyme concentrations. After ligation and transformation with E. coli DH5α (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), plasmids were isolated and sequenced. Some plasmids were identified in which mung bean nuclease had removed a single base (T) at the double-stranded end, resulting in a 201-bp in-frame deletion of glnB. The plasmid bearing this in-frame deletion was named pYPZ216, transformed into E. coli S17-1, and then conjugated into R. rubrum. Smr Nxr Kmr colonies were selected, so that the entire plasmid was integrated into chromosome of R. rubrum, yielding UR689. As described for the construction of the PII-Y51F-expressing strain above, UR689 was grown in SMN with Nx (20 mg/ml) for more than 130 generations, and 100 Kms colonies were obtained. Some of these isolates were screened by PCR amplification, and approximately 50% contained the internal deletion of glnB. A representative isolate, containing ΔglnB3, was designated UR717.

Similarly, to construct an R. rubrum ΔglnB3 draG double mutant, pJHL201, containing draG4::kan (38), was conjugated into UR717. Smr Nxr Kmr R. rubrum colonies were selected and replica printed to identify Cms colonies resulting from a double crossover event. The R. rubrum ΔglnB3 draG4::kan mutant was named UR733.

Cloning of nifA and construction of a nifA mutant.

Three oligonucleotides nifA-P1 (5′-GGAGCTGTTCGGCCACGAGAAGGGCG-3′), nifA-P2 (5′-CAGTTCTCCAGCTCGCGCACGTTGCC-3′), and nifA-P3 (5′-CGGGCGGCCTTGGCCTGCACCCAGCC-3′) were designed from three conserved regions of nifA from other N2-fixing bacteria. The nifA-P1 falls in the central domain, nifA-P2 falls in the interdomain linker region, and nifA-P3 falls near the C terminus (46). These were used as primers to PCR amplify nifA from R. rubrum. Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used for the PCR reaction under the following conditions: 100 to 200 ng of R. rubrum DNA, 0.4 μM concentrations of each primer, 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, and 5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase. The reaction was carried out in 50 μl of 1× Pfu DNA polymerase reaction buffer. The cycling of PCR reactions was as follows: 95°C for 45 s for one cycle; 95°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 3 min for 30 cycles; and a final incubation at 72°C for 10 min. A 450-bp PCR product was seen in reactions with the nifA-P1 and nif-P2 primers, and an 850-bp fragment was seen with the nifA-P1 and nif-P3 primers. These PCR fragments were then cloned into pBSKS(−) (Stratagene), yielding pYPZ217 and pYPZ218, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequence from pYPZ217 and pYPZ218 showed high similarity to NifA from other N2-fixing bacteria.

To construct a nifA mutant of R. rubrum, the 450-bp nifA′ fragment from pYPZ217 was subcloned into pUX19 (D. P. Lies and G. P. Roberts, unpublished data), yielding pYPZ219. pYPZ219 was transformed into E. coli S17-1, then conjugated into R. rubrum, selecting Smr Nxr Kmr colonies. Because only a portion of the internal nifA gene was carried on the suicide vector, the integration of this vector into the nifA gene on chromosome will disrupt nifA. A representative isolate with the nifA mutation was designated UR691.

To clone the entire R. rubrum nifA gene, total DNA was isolated from UR691 and digested with BamHI or HindIII. After ligation and transformation into E. coli DH5α, Kmr colonies were selected, and plasmid was isolated from each transformant. Two new plasmids were named pYPZ220-4 (from the BamHI digestion) and pYPZ220-9 (from the HindIII digestion). Because pYPZ219 contains only a single site of BamHI or HindIII at each end of the insert of the nifA′ fragment, these two plasmids should contain either the 3′ or the 5′ portion of nifA from the chromosome when they were digested with BamHI or HindIII. Indeed, pYPZ220-4 has a 2.5-kb insert containing the nifA′ fragment, as well as the 5′ end of the nifA region, and pYPZ220-9 has a 9-kb insert with the nifA′ fragment and the 3′ end of the nifA region. Both plasmids were used for DNA sequencing of the entire nifA. As expected, pYPZ220-4 and pYPZ220-9 overlap by about 450 bp of the nifA′ fragment.

Construction of a nifA::lacZ fusion.

A 1.7-kb BamHI-SalI fragment from pYPZ220-4, containing the promoter region of nifA and part of nifA itself, was subcloned into pBSKS(−), yielding pYPZ224. The vector provides a KpnI site for the next cloning step. A 500-bp NheI-KpnI fragment from pYPZ224, containing a region 5′ of nifA and a small portion of nifA itself, was inserted into the XbaI-KpnI sites of pHRP309, a broad-host-range transcriptional fusion vector (54), yielding pYPZ228. pHRP309 and pYPZ228 were transferred from E. coli into R. rubrum separately by triparental mating as described previously (38, 68) with pRK2013 as helper plasmid (13). Smr Nxr Gmr colonies were selected, and these plasmids were isolated from these transconjugants to confirm their presence.

Expression of nifA from R. rubrum and K. pneumoniae.

The entire nifA region (ca. 3.8 kb) was amplified by PCR from total DNA of R. rubrum wild type and then cloned into pRK404 (12), yielding pYPZ239. Plasmids of pYPZ239 (containing R. rubrum nifA) and pCK3 (containing K. pneumoniae nifA) (35) were transferred into R. rubrum into by triparental mating.

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequences were determined with the ABI PRISM DyeTerminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing data were analyzed with DNASTAR software programs (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.).

The DNA sequence of glnA and its downstream region is in the GenBank under accession number AF029703, and the sequence of nifA region is under accession number AF145956.

Other DNA techniques.

MasterPure genomic DNA Purification Kit from Epicentre (Madison, Wis.) was used for total DNA isolation from R. rubrum, with a few minor modifications. A total of 0.5 to 1 ml of cells was used for DNA isolation. After isopropanol precipitation, DNA was resuspended in 500 μl of 0.1 M sodium acetate and 0.05 M morpholine propanesulfonate (MOPS; pH 8.0) and then reprecipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol. This step significantly improved the quality of DNA. The modified transformation method was used (23), and other DNA manipulations were performed by standard methods (56).

Protein immunoblotting.

A trichloroacetic acid precipitation method was used to extract protein quickly as described previously (66). Low-cross-linker SDS-PAGE (ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide of 172 to 1) was used for protein separation to obtain better resolution of the modified versus unmodified subunits, and the modified subunit migrates more slowly. Proteins from SDS-PAGE were electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and then immunoblotted with polyclonal antibody against dinitrogenase reductase or GS and visualized by use of enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) or horseradish peroxidase color detection reagents (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.).

Assay for β-galactosidase in liquid culture.

R. rubrum cultures were first grown in SMN medium and then inoculated into SMN, MN, or MG media with a 65-fold dilution. SMN-grown cultures were grown aerobically in the dark for 2 days. MN- or MG-grown cultures were anaerobically grown under light for 2 days. Ten microliters of liquid culture was used for the β-galactosidase assay by the standard protocol as described previously (51). The reactions were carried out at 30°C for 3 min.

RESULTS

Nitrogenase is poorly expressed when only PII-Y51F is present.

The glnBA has been cloned from R. rubrum, and the entire glnB and a small portion of glnA have been sequenced previously (29). We and others (29) have tried to generate glnB and glnA insertion mutants without success, presumably because the absence of GS is lethal. To further study the function of PII, a PII-Y51F variant was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. Because Tyr-51 is conserved in all PII proteins and is the site of uridylylation of E. coli PII, this substitution should alter the regulation of PII activity (always deuridylylated), but it was not expected to be lethal.

A strain expressing only a PII-Y51F (UR659) had a normal growth in SMN medium, grew faster than the wild type in MG medium, and appeared to have darker red pigmentation. However, UR659 failed to grow diazotrophically in MN− medium and had a low nitrogenase activity in MG medium, i.e., ca. 15% of that seen in wild-type UR2 (Table 2). Consistent with this low nitrogenase activity, Western blots showed that about 10 to 20% of wild-type level of dinitrogenase reductase and dinitrogenase were accumulated in UR659 (data not shown). These results indicate that PII-Y51F has significant effects on nif expression in R. rubrum.

TABLE 2.

Nitrogenase activity and the modification of dinitrogenase reductase in R. rubrum wild type and mutants in the presence or absence of K. pneumoniae nifA (in pCK3) or R. rubrum nifA (in pYPZ239)

| Strains (genotype) | Plasmid | Nitrogenase activity (U)a | Dinitrogenase reductase in MG mediumb |

|---|---|---|---|

| UR2 (wild type) | 1,200 ± 200 | Wild-type level, unmodified | |

| UR214 (draG4::kan) | 1,000 ± 200 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified | |

| UR659 (glnB1, encoding PII-Y51F) | 150 ± 50 | 10 to 20% of wild-type level, unmodified | |

| UR686 (glnB1 draG4::kan) | <2 | Low protein level, completely modified | |

| UR687 (glnA2, encoding GS-Y398F) | 900 ± 10 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified | |

| UR691 (nifA1) | <2 | No protein accumulated | |

| UR717 (ΔglnB3) | <2 | Very low protein level, modified | |

| UR732 (ΔglnB3 draG4::kan) | <2 | NT | |

| UR694 (wild type) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 800 ± 100 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified |

| UR695 (glnB1, encoding PII-Y51F) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 500 ± 50 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified |

| UR696 (glnB1 draG4::kan) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 400 ± 100 | Similar to wild-type level, partial modified |

| UR697 (nifA1) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 700 ± 100 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified |

| UR698 (draG4::kan) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 500 ± 100 | Similar to wild-type level, a little modified |

| UR720 (ΔglnB3) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 500 ± 50 | NT |

| UR733 (ΔglnB3 draG4::kan) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 300 ± 100 | Similar to wild-type level, substantial modified |

| UR741 (wild type) | pYPZ239 (R. rubrum nifA) | 670 ± 60 | Similar to wild-type level, slightly modified |

| UR742 (glnB1, encoding PII-Y51F) | pYPZ239 (R. rubrum nifA) | 770 ± 50 | Similar to wild-type level, unmodified |

| UR743 (nifA1) | pYPZ239 (R. rubrum nifA) | 580 ± 70 | Similar to wild-type level, slightly modified |

| UR744 (ΔglnB3) | pYPZ239 (R. rubrum nifA) | 60 ± 20 | Low protein level, unmodified |

Unit of nitrogenase activity is in nanomoles of ethylene produced per hour per milliliter of cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1. Each activity is from at least five replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The mean ± the standard deviation is given.

The level and modification of dinitrogenase reductase from derepression (MG-grown) cells were monitored by Western blots. NT, not tested.

PII-Y51F alteration affects posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in response to NH4+.

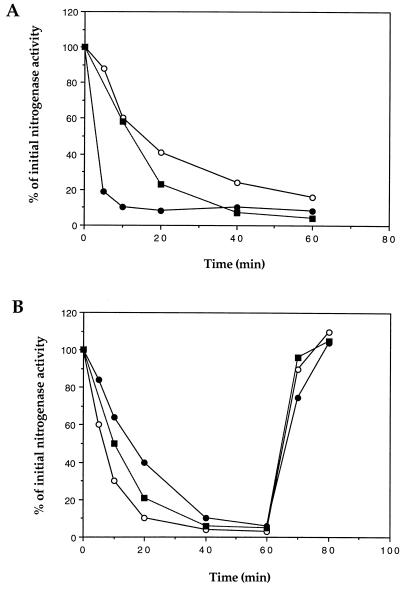

In R. rubrum, nitrogenase activity is regulated by the reversible ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase catalyzed by the DRAT-DRAG regulatory system in response to changes in NH4+ or energy status. To determine if PII plays any role in the DRAT-DRAG regulatory system, the regulation of nitrogenase activity was compared in UR2 (wild type) and UR659 (PII-Y51F) in response to NH4+ addition or the removal of light. As seen before with UR2, the addition of 10 mM NH4+ causes a slow decrease in nitrogenase activity, finally reaching a stable plateau of about 20 to 30% of the initial activity (65). However, after treatment with the same concentration of NH4+, UR659 showed a very rapid loss of nitrogenase activity, with a low percentage of residual activity (Fig. 1A). In contrast to the NH4+ results, UR659 showed a slightly slower response to darkness than did UR2 (Fig. 1B). Similar to that of UR2, nitrogenase activity in UR659 recovered completely when the cells were returned to light (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that PII plays a significant role in the signal transduction to DRAT-DRAG in response to NH4+ but less of a role in response to darkness.

FIG. 1.

Regulation of nitrogenase activity by NH4+ (A) and darkness (B) in R. rubrum UR2 (wild type) (○), UR659 (PII-Y51F) (●), and UR687 (GS-Y398F) (■). (A) NH4Cl was added at t = 0 to derepressed cultures UR2, UR659, and UR687 to a final concentration of 10 mM. (B) Derepressed cultures of UR2, UR659, and UR687 were shifted to darkness at t = 0, and cells were returned to light at 60 min. At the times indicated, 1-ml portions of cells were withdrawn and assayed for nitrogenase activity anaerobically under illumination conditions for 2 min. Initial nitrogenase activities (100%) in UR2, UR659, and UR687 were about 1,200, 200, and 1,000 nmol of ethylene produced per h per ml of cells, respectively, at an optical density of 1.0 at 600 nm. Each point represents an average of at least three replicate assays, with about 10% deviation.

We recognize that the level of dinitrogenase reductase is significantly lower in the strain with PII-Y51F than in the wild type and that this might affect the rate of modification of dinitrogenase reductase, at least when measured as “the percentage of initial nitrogenase activity.” However, this lower ratio of dinitrogenase reductase to DRAT is unlikely to be a major factor in causing the faster rate in response to NH4, since the response of the same strain to darkness is slightly slower than that of the wild type.

PII affects DRAT activity.

The activities of DRAG and DRAT are independently regulated in response to NH4+ or darkness (41, 67). To determine which of these proteins was the target of the PII-Y51F effect seen above, DRAG was eliminated from the cell so that we could monitor DRAT activity by itself. A strain expressing PII-Y51F and also lacking DRAG (UR686) was constructed and analyzed. UR686 showed a complete absence of nitrogenase activity (Table 2), and Western analysis showed dinitrogenase reductase to be completely modified under nitrogen-fixing conditions (data not shown). Under similar conditions, a strain with wild-type PII, but lacking DRAG (UR214), has been shown to have nearly normal nitrogenase activity (Table 2), reflecting the tight posttranslational regulation of DRAT activity as reported previously (38). This result indicates that the negative regulation of DRAT activity is partially abolished in UR659 (PII-Y51F) under nitrogen-fixing conditions.

Characterization of glnB deletion mutant (lacking PII).

Because of the interesting behavior of strains expressing PII-Y51F, a strain with a nonpolar in-frame deletion within glnB (UR717) was constructed, as described in Materials and Methods. The ability to construct such a mutant argues that previous failures to create an insertion mutant in glnB were due to the polar effect of the insertion onto glnA. In contrast to the results in UR659 (PII-Y51F), UR717 grew more slowly in MG medium, with less red pigment than UR2 (wild type) (data not shown). Unlike UR659, UR717 contained no nitrogenase activity under nif-derepressing conditions (Table 2), and Western blots revealed a very low accumulation of dinitrogenase reductase and dinitrogenase proteins in UR717 under nif derepression conditions (data not shown). These results indicate that PII is essential for significant derepression of nitrogenase in R. rubrum.

Characterization of nifA in R. rubrum.

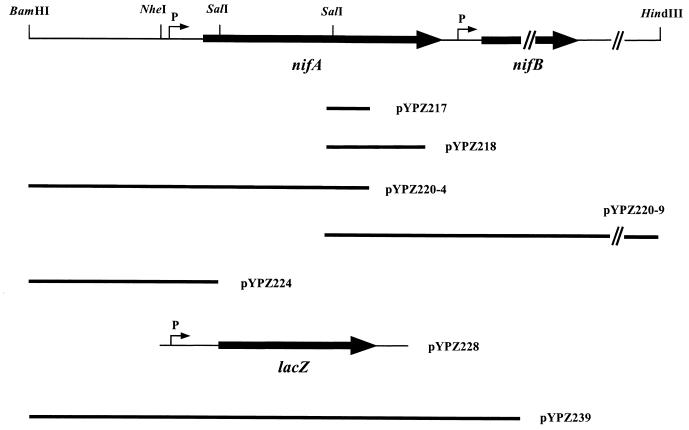

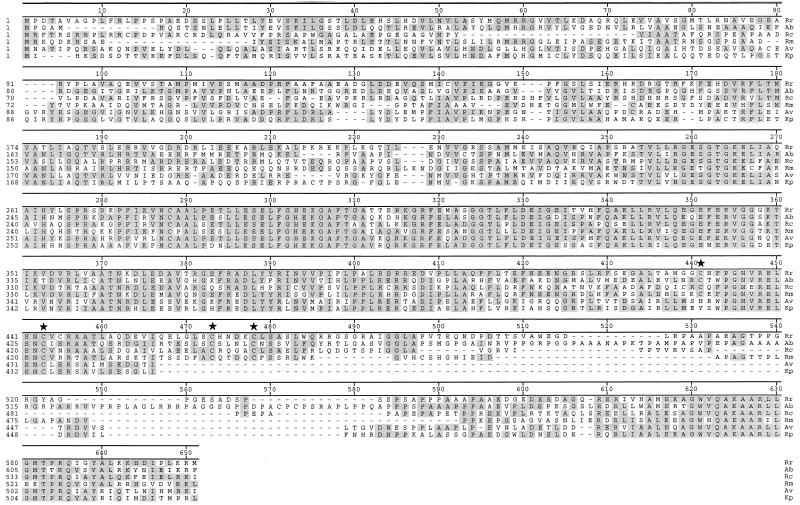

The effect of PII on nif expression has been reported in other N2-fixing organisms, and it is mediated through NifA, the positive regulator for the expression of the other nif genes (10, 46). PII can affect NifA in two ways: expression and activity. In K. pneumoniae under NH4+-excess conditions PII stimulates NtrB to dephosphorylate NtrC, so that nifA expression is repressed. However, in other bacteria, such as A. brasilense, PII controls NifA at the posttranslational level (1, 40). To further characterize effects of PII on nifA in R. rubrum, nifA was therefore cloned and sequenced, as described in Materials and Methods, and the map of the nifA region is showed in Fig. 2. The deduced amino acid sequence of NifA is highly similar to NifA from other N2-fixing bacteria, especially in the central domain and C terminus (Fig. 3). Like other N2-fixing bacteria, such as A. brasilense, R. capsulatus, Rhizobium meliloti, Rhizobium leguminosarum, and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (14, 21, 40, 44, 50, 59), NifA from R. rubrum also has an interdomain linker between the central domain and the C terminus. Four cysteines were located in this linker, which is thought to be involved in O2 sensing (14) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Physical map of nifA region from R. rubrum. Plasmids used for cloning and expression of nifA were indicated.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of NifA from R. rubrum (Rr), A. brasilense (Ab), R. capsulatus (Rc), Rhizobium meliloti (Rm), A. vinelandii (Av), and K. pneumoniae (Kp). Four cysteine residues (★) located in interdomain linker might involve in sensing O2.

An open reading frame (ORF) was identified at the 3′ end of nifA and was partially sequenced, revealing a high similarity to nifB from A. brasilense, R. capsulatus, and other N2-fixing bacteria (39, 44) (Fig. 2). The region between nifA and nifB contains a TGG-N9-TGC sequence, which is reminiscent of a ς54-dependent promoter (46). Two TGT-N10-ACA sequences, resembling a NifA-binding site, were also found upstream of this apparent ς54-dependent promoter (5, 6). Similar features were also found upstream of nifHDK of R. rubrum (36). These data suggest that NifA is required for the transcriptional activation of nifB as it is for nifHDK.

A mutant with an insertion in nifA (UR691) was constructed as described in Methods and Materials. UR691 showed a complete loss of nitrogenase activity when it is derepressed in MG medium (Table 2). No dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase were detected in UR691 on Western blots (data not shown). These results indicated that NifA is essential for nif expression in R. rubrum. In R. rubrum, there is an alternative nitrogenase system (Fe only), and it is usually expressed when lacking normal nitrogenase (37). However, no detectable level of expression of alternate nitrogenase was found in the nifA mutant, indicating that NifA is directly or indirectly involved in the expression of the alternate nitrogenase system in R. rubrum.

Expression of nifA is not regulated in R. rubrum.

We have previously shown that NtrBC is not required for nitrogen fixation in R. rubrum (69), and consistent with this fact, neither a putative NtrC binding site nor a ς54-dependent promoter was found 5′ of nifA. The effects of PII noted above must therefore occur through another mechanism. To determine if PII affects nifA expression, a nifA::lacZ fusion plasmid (pYPZ228) was constructed as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2). Both pYPZ228 and pHRP309 (vector alone) were transferred into different R. rubrum backgrounds, and β-galactosidase activity was monitored under three growth conditions. As shown in Table 3, some background β-galactosidase activity was seen in R. rubrum with pHRP309 (vector), and a similar background activity was seen when pHRP309 was transferred into R. capsulatus (54). However, at least a fivefold increase of β-galactosidase activity was seen when pYPZ228 (nifA::lacZ) was introduced. A similar β-galactosidase activity was found in different background strains, including wild type (UR708), ntrBC mutant (UR709), nifA mutant (UR711), and glnB1 (PII-Y51F) mutant (UR710), when grown under N2-fixing conditions (MG medium). A lower β-galactosidase activity was found in the glnB deletion mutant (UR722) when grown in MG medium. This low β-galactosidase activity might be due to other physiological perturbance of this ΔglnB mutant in MG medium, because β-galactosidase activity in the vector control strain (UR721) was also lower than in other control strains (Table 3). NH4+ and O2 have no significant effects on the nifA expression in R. rubrum, since a similar high β-galactosidase activity was seen in all strains when grown anaerobically in MN medium or aerobically in SMN medium (Table 3). The expression of nifA is therefore apparently constitutive in R. rubrum, and the PII effects on nif expression noted above must be at the level of NifA activity, although the nature of this PII-NifA interaction is unknown at present.

TABLE 3.

β-Galactosidase activity in R. rubrum strains containing nifA-lacZ fusion (pYPZ228) or vector alone (pHRP309) under different growth conditions

| Strain | Plasmid | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) in different growth conditionsa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG, anaerobic | MN, anaerobic | SMN, aerobic | ||

| UR708 (wild type) | pYPZ228 | 7,100 ± 910 | 5,140 ± 170 | 4,260 ± 240 |

| UR709 (ΔntrBC1) | pYPZ228 | 8,020 ± 380 | 5,400 ± 350 | 4,190 ± 180 |

| UR710 (glnB1, PII-Y51F) | pYPZ228 | 7,690 ± 520 | 7,970 ± 580 | 4,900 ± 70 |

| UR711 (nifA1) | pYPZ228 | 6,060 ± 950 | 6,170 ± 190 | 4,670 ± 120 |

| UR722 (ΔglnB3) | pYPZ228 | 3,600 ± 320 | 6,020 ± 230 | 4,520 ± 210 |

| UR712 (wild type) | pHRP309 | 1,060 ± 170 | 1,030 ± 170 | 1,020 ± 40 |

| UR713 (ΔntrBC1) | pHRP309 | 1,130 ± 400 | 910 ± 50 | NT |

| UR714 (glnB1, PII-Y51F) | pHRP309 | 1,130 ± 80 | 1,010 ± 30 | 1,150 ± 10 |

| UR715 (nifA1) | pHRP309 | 1,110 ± 30 | 810 ± 10 | NT |

| UR721 (ΔglnB3) | pHRP309 | 700 ± 120 | 990 ± 90 | 1,150 ± 40 |

R. rubrum was grown in three different conditions: aerobically in rich SMN (rich) medium, anaerobically in MN medium (high concentration of NH4+), or anaerobically in MG (no NH4+). Each activity is from at least six replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The mean ± the standard deviation is given. NT, not tested.

Expression of nifA from R. rubrum and K. pneumoniae in R. rubrum.

Because PII is apparently required for NifA activity in R. rubrum, we reasoned that a heterologous, constitutively expressed K. pneumoniae nifA should restore nitrogenase activity in R. rubrum glnB mutants, since the activity of K. pneumoniae NifA does not require activation by PII in K. pneumoniae. In order to test this hypothesis, we introduced pCK3, containing K. pneumoniae nifA expressed from a constitutive promoter (35), into various R. rubrum strains. The expression of K. pneumoniae nifA has some effects on nitrogenase activity in a wild-type background, since UR694 has a slightly lower nitrogenase activity than UR2 does (Table 2). However, the expression of K. pneumoniae NifA from pCK3 restored nitrogenase activity in a R. rubrum nifA mutant (UR697) and glnB mutants (UR695 and UR720), although the nitrogenase activity in these strains is slightly lower than that seen in UR694 (wild type with pCK3) (Table 2). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that effects of mutations in glnB on nif expression in R. rubrum occur through their effects on NifA.

K. pneumoniae nifA was also transferred into glnB draG double mutants (UR696 and UR733), as well as a draG single mutant (UR698). A significantly lower nitrogenase activity was seen in UR696 and UR733, compared with control strains with the same plasmid (Table 2). Western blots revealed that both UR696 and UR733 accumulated similar amounts of dinitrogenase reductase as seen in UR694, but this dinitrogenase reductase was substantially modified under derepression conditions (data not shown). In contrast, UR698 showed a little modification of dinitrogenase reductase under the same conditions. This result supports the conclusion that DRAT activity is not properly regulated in these glnB mutants. However, since there is clearly still some regulation of DRAT activity in glnB mutants, PII cannot be the only regulatory protein for DRAT activity.

R. rubrum nifA was also transferred into some of these R. rubrum backgrounds. Nitrogenase activity and the statues of dinitrogenase reductase were monitored, and the results are shown in Table 2. Like the results with K. pneumoniae nifA, the presence of multiple copies of R. rubrum nifA could restore nitrogenase activity in UR742 (PII-Y51F) and UR743 (nifA). However, the expression of R. rubrum nifA failed to restore nitrogenase activity in UR744 (ΔglnB). This indicates that most of the NifA is still inactive in this glnB deletion mutant even though multiple copies of nifA were in the cell. We interpret this to mean that PII is essential for the NifA activation in R. rubrum.

Expression of unregulated GS does not affect nif expression or DRAT-DRAG regulation in R. rubrum.

NH4+ itself is not the direct signal for the DRAT-DRAG system, since methionine sulfoximine, an inhibitor of GS, can significantly block the NH4+ effect on nitrogenase activity in both A. brasilense and R. rubrum (19, 34). Consistent with this, intracellular glutamine concentration increases rapidly after the addition of NH4+ in both R. rubrum and A. brasilense (17, 33). We therefore wondered if GS plays any role in the signal transduction from NH4+ to DRAT-DRAG system.

To begin to dissect this genetically, we wished to create mutants altered in GS. Because only a small portion of glnA (encoding GS) of R. rubrum has been sequenced (29), we first sequenced entire glnA region and part of its downstream region. The GS of R. rubrum is highly similar to the GS from that of other bacteria (e.g., 75% identity to the GS of A. brasilense and 62% identity to the GS of E. coli) and Tyr-398, the site for the adenylylation of GS, is conserved. A 37-bp strong stem-loop structure was found 3′ of glnA, and this was followed by an ORF that was partially sequenced. This ORF is similar to glnH from E. coli and Bacillus stearothermophilus, bztA from R. capsulatus, and ybeJ from E. coli (4, 53, 64, 70). It has been known that glnH and btzA encode glutamine-binding proteins (53, 64, 70), but the function of this ORF in R. rubrum is unknown. It is also unknown if this ORF is cotranscribed with glnBA.

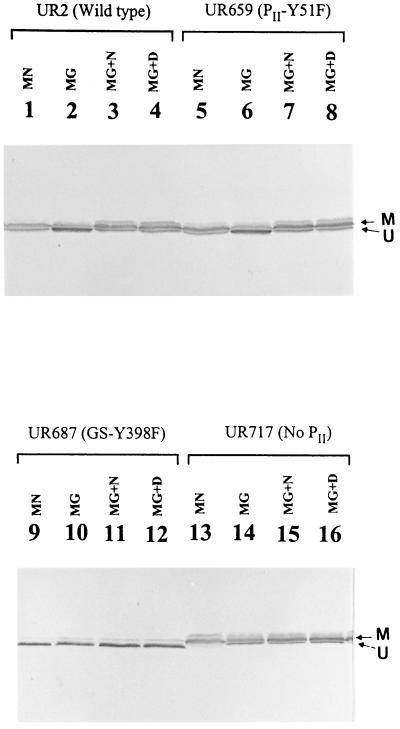

Because of the apparent lethality of insertion mutations in glnA, we constructed a GS-Y398F variant (UR687) as described in Materials and Methods. GS-Y398F should not be adenylylated and therefore should always be active. We first monitored the modification of GS in UR2 (wild type) and UR687 (GS-Y398F) by Western blots under different growth conditions. In the presence of a high concentration of NH4+ (MN medium), GS in UR2 migrated as two bands (Fig. 4): the lower band is the unmodified subunit of GS, and the upper band is the adenylylated subunit. A strong upper band indicated that the GS was substantially modified under NH4+-excess conditions (MN medium) (Fig. 4, lane 1). In contrast, GS was substantially unmodified when UR2 was grown in N2-fixing conditions (MG medium) (Fig. 4, lane 2). These results generally conform to the paradigm of GS regulation. Interestingly, GS becomes modified after the addition of NH4+ (Fig. 4, lane 3) or after a shift to darkness (Fig. 4, lane 4). Another faint band was seen above the upper band, and it is unknown if it is another form of modification of GS. In R. rubrum, GS can also be modified by an apparent ADP-ribosylation reaction (63).

FIG. 4.

Western immunoblot of GS in UR2 (wild type), UR659(PII-Y51F), UR687 (GS-Y398F), and UR717 (no PII). Samples of GS were from cultures grown in the presence of a high concentration of NH4+ (MN) or in the absence of NH4+ (MG). MG-grown cells were also treated with 10 mM NH4Cl (MN+N) or shifted from light to dark (MN+D) for 60 min. Similar amounts of total protein were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GS. Arrow M indicates the position of the modified subunit, and arrow U indicates the position of the unmodified subunit.

Unlike UR2 (wild type), GS-Y398F in UR687 is unmodified when cells were grown in either MN or MG media (Fig. 4, lanes 9 and 10). Similarly, GS-Y398F cannot be modified following NH4+ or darkness treatments (Fig. 4, lanes 11 and 12), verifying Tyr-398 as the site of adenylylation. GS-Y398F migrates slightly faster than the unmodified wild-type GS, presumably because of the Y398F substitution. Another unknown faint band was also seen in UR687 and appears in all conditions. UR687 has a high nitrogenase activity, one similar to that of UR2 (Table 2). UR687 also showed normal regulation of nitrogenase activity in response to darkness and ammonium, as seen in UR2 (Fig. 1). These results indicate that the “permanently active” form of GS has no significant effect on either nif expression or the ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase.

Mutations of glnB have no apparent effect on glnA expression or GS modification.

In E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and other bacteria, PII not only regulates the expression of glnA but also controls GS activity. Specifically, the unmodified form of PII, together with glutamine and α-ketoglutarate, stimulates the adenylylation of GS (52). To study the effect of glnB mutations on the synthesis and adenylylation of GS in R. rubrum, the level of GS and its modification were monitored in UR659 (PII-Y51F) and UR717 (no PII) in different growth conditions. To examine the levels of GS protein accumulated in the cell, similar amounts of total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GS. The level of GS in UR659 (PII-Y51F) was very similar to that seen in UR2 (wild type) (Fig. 4), and the levels of GS in UR687 (GS-Y398F) and UR717 (no PII) were slightly lower than that in UR2. These results suggested that PII has no drastic effect on glnA expression. GS from UR659 and UR717 showed a very similar pattern of modification, as seen in UR2 (lanes 5 to 8 and lane 13 to 16, Fig. 4), indicating that PII had no significant effect on the regulation of the modification of GS. These results were somewhat surprising and will be discussed below.

DISCUSSION

PII plays a very important role in nitrogen fixation in R. rubrum because a deletion mutant of glnB (UR717) showed little nitrogenase activity. The effect of PII on the nif expression is through NifA. Unlike the situation in K. pneumoniae, PII does not regulate nifA expression, and NifA is synthesized under NH4+ and aerobic conditions in R. rubrum. Apparently, NifA exists in either active or inactive forms, and PII is required for the activation of NifA activity under N2-fixing conditions. Similar regulation of NifA activity has been seen in A. brasilense and Herbaspirillum seropedicae (1, 40, 58). However, the mechanism for the activation of NifA activity (whether it is direct or indirect) is unknown in all cases. Recent studies seen in A. brasilense and H. seropedicae have shown that the N-terminal domain of NifA has an inhibitory effect on NifA activity, since NifA activity is no longer inhibited by NH4+ when this N-terminal domain is deleted (1, 58). In K. pneumoniae and A. vinelandii, NifA activity can be inhibited by another regulatory nif protein, NifL, probably by means of a direct interaction (46). However, no NifL homologue has been found in R. rubrum or A. brasilense.

A mutant with an altered PII (UR659, PII-Y51F) showed a decrease of nif expression and lower nitrogenase activity (about 10 to 20% that of wild type). This indicated that some NifA is still active in this mutant under N2-fixing conditions. However, expression of R. rubrum nifA from a multicopy plasmid was able to completely restore nitrogenase activity in PII-Y51F mutant (UR742) but not in a deletion mutant lacking PII (UR744). These results argue that while PII (probably its uridylylated form) is essential for NifA activity, NifA can still be activated even in the presence of unmodified PII. A simple model that PII-UMP activates NifA activity and PII inhibits NifA is probably incorrect in R. rubrum, and it is completely unclear if the effect of PII on NifA activity is direct or indirect.

This altered PII (PII-Y51F) also showed some effect on the DRAT regulation. A very rapid loss of nitrogenase activity was seen in UR659 in response to NH4+, while a slow response was seen in UR2 (wild type). Furthermore, substantial DRAT activity was found in UR659 under N2-fixing conditions, indicating that DRAT is not properly regulated in this mutant. It is unknown if the effect of PII on DRAT is direct or indirect, nor is it clear if PII has any effect on the regulation of DRAG activity.

In R. rubrum, GS can be adenylylated in response to NH4+ addition or a shift to darkness. However, mutations in PII have no significant effect on the adenylylation of GS. Similarly, no differences in the extent of modification of GS were seen between wild type and a glnB mutant of E. coli and A. brasilense (2, 9, 11, 60, 61). A PII paralog, named GlnK or PZ, has been identified in E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. brasilense, Azorhizobium caulinodans, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and H. seropedicae (3, 11, 24, 48, 49, 55, 61), and it shows high similarity to glnB (24). Either GlnK or PII can effectively regulate ATase to adenylylate or deadenylylate GS in E. coli and A. caulinodans (49, 60, 61). Recently, GlnK was found to be involved in the regulation of NifA activity by relief of NifL inhibition in K. pneumoniae (20, 24). It is our working hypothesis that glnK also exists in R. rubrum and might be involved in the modification of GS.

Because NH4+ controls nif expression and DRAT-DRAG activities, it is possible that these two separate regulatory systems share some common signal transduction pathways. Indeed, several mutants have been found in A. brasilense and R. sphaeroides that show high nitrogenase activity even in the presence of high concentration of NH4+, indicating a perturbation of both regulatory systems. Some of these mutants in A. brasilense also showed other phenotypes such as low GS activity, a defect in histidine transport, or a low rate of NH4+ uptake (8, 15, 18, 43). Unfortunately, genes linked to these phenotypes have not been identified. Recently, mutants in cbbM with defects in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham pathway have been found in R. sphaeroides and R. rubrum, and these mutants show high nitrogenase activity in the presence of NH4+ (31). Furthermore, the expression of glnB and glnK was also affected in an R. sphaeroides cbbM mutant (55). These results suggest that PII or/and GlnK might be involved in nif expression and the DRAT-DRAG regulatory system in R. rubrum, and it will be very interesting to characterize the function of GlnK in R. rubrum.

In summary, we report here the functional characterization of several regulatory genes involved in nitrogen fixation in R. rubrum. PII plays an important role and is involved in the regulation of NifA activity and is apparently involved in the regulation of DRAT-DRAG system. The further characterization of these regulatory factors will provide important information about the regulation of nitrogen fixation in this and related organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Department of Agriculture grant 96-37305-3696 to G.P.R. and NIGMS grant 54910 to P.W.L.

We thank C. S. Harwood, J. Li and C. Kennedy for kindly providing plasmids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arsene F, Kaminski P A, Elmerich C. Modulation of NifA activity by PII in Azospirillum brasilense: evidence for a regulatory role of the NifA N-terminal domain. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4830–4838. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4830-4838.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. Role of the GlnK signal transduction protein in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:431–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benelli E M, Souza E M, Funayama S, Rigo L U, Pedrosa F O. Evidence for two possible glnB-type genes in Herbaspirillum seropedicae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4623–4626. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4623-4626.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blattner F R, Plunkett G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck M, Cannon W, Woodcock J. Mutational analysis of upstream sequences required for transcriptional activation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae nifH promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:9945–9956. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.23.9945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck M, Miller S, Drummond M, Dixon R. Upstream activator sequences are present in the promoters of nitrogen fixation genes. Nature. 1986;320:370–378. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burris R H. Nitrogenases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9339–9342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen-Weniger C, Van Veen J A. NH4+-excreting Azospirillum brasilense mutants enhance the nitrogen supply of a wheat host. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3006–3012. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.3006-3012.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Zamaroczy M. Structural homologues PII and PZ of Azospirillum brasilense provide intracellular signalling for selective regulation of various nitrogen-dependent functions. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:449–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Zamaroczy M, Paquelin A, Elmerich C. Functional organization of the glnB-glnA cluster of Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2507–2515. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2507-2515.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Zamaroczy M, Paquelin A, Peltre G, Forchhammer K, Elmerich C. Coexistence of two structurally similar but functionally different PII proteins in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4143–4149. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4143-4149.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditta G, Schmidhauser T, Yakobson E, Lu P, Liang X, Finlay D R, Guiney D, Helinski D R. Plasmids related to the broad range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expression. Plasmid. 1985;13:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figurski D, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in tran. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer H M, Bruderer T, Hennecke H. Essential and non-essential domains in the Bradyrhizobium japonicum NifA protein: identification of indispensable cysteine residues potentially involved in redox reactivity and/or metal binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:2207–2224. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer M, Levy E, Geller T. Regulatory mutation that controls nif expression and histidine transport in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:423–426. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.423-426.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzmaurice W P, Saari L L, Lowery R G, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Genes coding for the reversible ADP-ribosylation system of dinitrogenase reductase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;218:340–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00331287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu H A, Hartmann A, Lowery R G, Fitzmaurice W P, Roberts G P, Burris R H. Posttranslational regulatory system for nitrogenase activity in Azospirillum spp. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4679–4685. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4679-4685.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauthier D, Elmerich C. Relationship between glutamine synthetase and nitrogenase in Spirillum lipoferum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;2:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann A, Fu H A, Burris R H. Influence of amino acids on nitrogen fixation ability and growth of Azospirillum spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:87–93. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.1.87-93.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He L, Soupene E, Ninfa A, Kustu S. Physiological role for the GlnK protein of enteric bacteria: relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6661–6667. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6661-6667.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iismaa S E, Watson J M. The nifA gene product from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii lacks the N-terminal domain found in other NifA proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:943–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue A, Shigematsu T, Hidaka M, Masaki H, Uozumi T. Cloning, sequencing and transcriptional regulation of the draT and draG genes of Azospirillum lipoferum FS. Gene. 1996;170:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 1990;96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jack R, De Zamaroczy M, Merrick M. The signal transduction protein GlnK is required for NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1156–1162. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1156-1162.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang P, Ninfa A J. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1906-1911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12782–12794. doi: 10.1021/bi980667m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. Reconstitution of the signal-transduction bicyclic cascade responsible for the regulation of Ntr gene transcription in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12795–12801. doi: 10.1021/bi9802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12802–12810. doi: 10.1021/bi980666u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson M, Nordlund S. Transcription of the glnB and glnA genes in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology. 1996;142:1265–1272. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson M, Nordlund S. Uridylylation of the PII protein in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4190–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4190-4194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi H M, Tabita F R. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14515–14520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamberov E S, Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17797–17807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanemoto R H, Ludden P W. Amino acid concentrations in Rhodospirillum rubrum during expression and switch-off of nitrogenase activity. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3035-3043.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanemoto R H, Ludden P W. Effect of ammonia, darkness, and phenazine methosulfate on whole-cell nitrogenase activity and Fe protein modification in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:713–720. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.713-720.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy C, Drummond M H. The use of cloned nif regulatory elements from Klebsiella pneumoniae to examine nif regulation in Azotobacter vinelandii. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1787–1795. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehman L J, Fitzmaurice W P, Roberts G P. The cloning and functional characterization of the nifH gene of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Gene. 1990;95:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90426-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehman L J, Roberts G P. Identification of an alternative nitrogenase system in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5705–5711. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5705-5711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang J H, Nielsen G M, Lies D P, Burris R H, Roberts G P, Ludden P W. Mutations in the draT and draG genes of Rhodospirillum rubrum result in loss of regulation of nitrogenase by reversible ADP-ribosylation. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6903–6909. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6903-6909.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang Y Y, de Zamaroczy M, Arsène F, Paquelin A, Elmerich C. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7: involvement of nifA, glnA and glnB gene products. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;79:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang Y Y, Kaminski P A, Elmerich C. Identification of a nifA-like regulatory gene of Azospirillum brasilense Sp7 expressed under conditions of nitrogen fixation and in the presence of air and ammonia. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2735–2744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Regulation of nitrogenase activity by reversible ADP ribosylation. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1989;30:23–56. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152830-0.50004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma L, Li J. Sequencing and analysis of function of the promoter region of draTG genes from Azospirillum brasilense Yu62. Chin J Biotechnol. 1997;13:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machado H B, Funayama S, Rigo L U, Pedrosa F O. Excretion of ammonium by Azospirillum brasilense mutants resistant to ethylenediamine. Can J Microbiol. 1991;37:549–553. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masepohl B, Klipp W, Pühler A. Genetic characterization and sequence analysis of the duplicated nifA/nifB gene region of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00322441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masepohl B, Krey R, Klipp W. The draTG gene region of Rhodobacter capsulatus is required for post-translational regulation of both the molybdenum and the alternative nitrogenase. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2667–2675. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merrick M J. Regulation of nitrogen fixation genes in free-living and symbiotic bacteria. In: Stacey G, Burris R H, Evens H J, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall, Inc.; 1992. pp. 835–876. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merrick M J, Edwards R A. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:604–622. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.604-622.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michel-Reydellet N, Desnoues N, de Zamaroczy M, Elmerich C, Kaminski P A. Characterisation of the glnK-amtB operon and the involvement of AmtB in methylammonium uptake in Azorhizobium caulinodans. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s004380050781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel-Reydellet N, Kaminski P A. Azorhizobium caulinodans PII and GlnK proteins control nitrogen fixation and ammonia assimilation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2655–2658. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2655-2658.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michiels J, D'Hooghe I, Verreth C, Pelemans H, Vanderleyden J. Characterization of the Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar phaseoli nifA gene, a positive regulator of nif gene expression. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:404–408. doi: 10.1007/BF00288950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ninfa A J, Atkinson M R, Kamberov E S, Feng J, Ninfa E G. Control of nitrogen assimilation by the NRI-NRII two-component system of enteric bacteria. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nohno T, Saito T, Hong J S. Cloning and complete nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli glutamine permease operon (glnHPQ) Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:260–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00430437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parales R E, Harwood C S. Construction and use of a new broad-host-range lacZ transcriptional fusion vector, pHRP309, for Gram− bacteria. Gene. 1993;133:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90220-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian Y, Tabita F R. Expression of glnB and a glnB-like gene (glnK) in a ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4644–4649. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4644-4649.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Souza E M, Pedrosa F O, Drummond M, Rigo L U, Yates M G. Control of Herbaspirillum seropedicae NifA activity by ammonium ions and oxygen. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:681–684. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.681-684.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thony B, Fischer H M, Anthamatten D, Bruderer T, Hennecke H. The symbiotic nitrogen fixation regulatory operon (fixRnifA) of Bradyrhizobium japonicum is expressed aerobically and is subject to a novel, nifA-independent type of activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8479–8499. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Heeswijk W C, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Stegeman B, Kahn D, Westerhoff H V. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:133–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6281349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Heeswijk W C, Stegeman B, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Kahn D, Westerhoff H V. An additional PII in Escherichia coli: a new regulatory protein in the glutamine synthetase cascade. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:153–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vieira J, Messing J. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene. 1991;100:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woehle D L, Lueddecke B A, Ludden P W. ATP-dependent and NAD-dependent modification of glutamine synthetase from Rhodospirillum rubrum in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13741–13749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu L, Welker N E. Cloning and characterization of a glutamine transport operon of Bacillus stearothermophilus NUB36: effect of temperature on regulation of transcription. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4877–4888. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4877-4888.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Comparison studies of dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyl transferase/dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase regulatory systems in Rhodospirillum rubrum and Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2354–2359. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2354-2359.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity by anaerobiosis and ammonium in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6781–6788. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6781-6788.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Roberts G P. Cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis, and functional characterization of draT and draG genes from Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3364–3369. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3364-3369.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, Cummings A D, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Effect of an ntrBC mutation on the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5322–5326. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5322-5326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zheng S, Haselkorn R. A glutamate/glutamine/aspartate/asparagine transport operon in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1001–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]