Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa secretes copious amounts of an exopolysaccharide called alginate during infection in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. A mutation in the algR2 gene of mucoid P. aeruginosa is known to exhibit a nonmucoid (nonalginate-producing) phenotype and showed reduced activities of succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase (Scs) and nucleoside diphosphate kinase (Ndk), implying coregulation of Ndk and Scs in alginate synthesis. We have cloned and characterized the sucCD operon encoding the α and β subunits of Scs from P. aeruginosa and have studied the role of Scs in generating GTP, an important precursor in alginate synthesis. We demonstrate that, in the presence of GDP, Scs synthesizes GTP using ATP as the phosphodonor and, in the presence of ADP, Scs synthesizes ATP using GTP as a phosphodonor. In the presence of inorganic orthophosphate, succinyl-CoA, and an equimolar amount of ADP and GDP, Scs synthesizes essentially an equimolar amount of ATP and GTP. Such a mechanism of GTP synthesis can be an alternate source for the synthesis of alginate as well as for the synthesis of other macromolecules requiring GTP such as RNA and protein. Scs from P. aeruginosa is also shown to exhibit a broad NDP kinase activity. In the presence of inorganic orthophosphate (Pi), succinyl-CoA, and either GDP, ADP, UDP or CDP, it synthesizes GTP, ATP, UTP, or CTP. Scs was previously shown to copurify with Ndk, presumably as a complex. In mucoid cells of P. aeruginosa, Ndk is also known to exist in two forms, a 16-kDa cytoplasmic form predominant in the log phase and a 12-kDa membrane-associated form predominant in the stationary phase. We have observed that the 16-kDa Ndk-Scs complex present in nonmucoid cells, synthesizes all three of the nucleoside triphosphates from a mixture of GDP, UDP, and CDP, whereas the 12-kDa Ndk-Scs complex specifically present in mucoid cell predominantly synthesizes GTP and UTP but not CTP. Such regulation may promote GTP synthesis in the stationary phase when the bulk of alginate is synthesized by mucoid P. aeruginosa.

Our laboratory is interested in studying the regulation of biosynthesis of alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen. A number of cystic fibrosis (CF) isolates have been studied for their enhanced synthesis and secretion of alginate (16). Alginate is a polymer of d-manuronic and its C-5 epimer l-guluronic acid. GDP-mannuronic acid, derived from GDP-mannose, is the building block of alginate, which requires mannose 1-phosphate and GTP as precursors (17). Thus, alginate synthesis demands a steady supply of GTP for every molecule of mannuronic acid incorporated into a molecule of alginate. Recently, Kamath et al. (9) have shown that the mucoid strains of P. aeruginosa retain an active form of elastase in their periplasm, and this periplasmic elastase acts on 16-kDa Ndk to generate a truncated 12-kDa form that is membrane associated. It has been demonstrated that the membrane-associated 12-kDa nucleoside diphosphate (NDP) kinase (Ndk), in complex with pyruvate kinase or Pra (5, 24), specifically synthesizes GTP. An ndk knockout mutation in P. aeruginosa is not lethal (27) because PK provides the nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) required for cell growth (24). However, the Ndk-deficient mutant still makes small amounts of alginate. Since an alginate-negative algR2 mutant in P. aeruginosa is deficient in both Ndk and Succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase (Scs) levels (23), an important question is whether Scs, like Ndk, plays a role in providing the GTP precursors for alginate synthesis.

Scs has been widely studied in a variety of organisms (11, 20), although nothing is known of the Scs of P. aeruginosa. It is involved in the only step in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle where a molecule of GTP or ATP is generated by substrate level phosphorylation. In Escherichia coli, Scs occurs predominantly in the A-form, where it exists as a heterotetramer consisting of α2 and β2 subunits. During aerobic growth, Scs catalyzes the hydrolysis of succinyl-CoA, using ADP and inorganic orthophosphate (Pi), to form succinate and ATP. However, Scs can freely interconvert ATP and succinate to form succinyl-CoA, ADP, and inorganic Pi for anabolic reactions as well, particularly during anaerobic growth (22). During enzymatic catalysis, Scs undergoes an intermediate Scs-α subunit phosphorylation. In eukaryotes, the Scs occurs predominantly in the G-form, where it is a heterodimer composed of the α and β subunits (8, 25). It interconverts succinyl-CoA to succinate, resulting in the synthesis or hydrolysis of GTP. In this study, we show that in P. aeruginosa Scs allows the synthesis of both ATP and GTP from succinyl-CoA, Pi, and an equimolar mixture of ADP and GDP. P. aeruginosa Scs is capable of generating UTP or CTP as well when exposed to succinyl-CoA, Pi, and UDP or CDP, thus exhibiting Ndk activity, although the enzyme preferentially synthesizes ATP and/or GTP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were maintained in E. coli DH5α which were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (40 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). Oligonucleotides used in this study were synthesized by Gibco-BRL laboratories.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Description or sequence | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | endA1 hsd supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA relA1 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS) | Cmr F−ompT hsd gal dcm | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28a | His-tag expression vector | Novagen |

| pSU6 | 20-kb cosmid DNA in pLARF1 containing the sucCD operon from P. aeruginosa PAO1 | This study |

| pXL804 | 3.5-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment from pSU6 in pUC118 | This study |

| pKV152 | 1,164-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment encoding sucC in pET28a | This study |

| pKV153 | 864-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment encoding sucD in pET28a | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 1 | CCGGATTCATGAGCGTCCTGATCAACAAAGAC | |

| 2 | GGAAGCTTTCAGGCCTTCAGTTCCCAACCGGTCAG | |

| 3 | GCGGAATTCATGAATCTCCACGAATATCA | |

| 4 | GGAAGCTTTACTTACCCTCCGCGGCC |

Cloning of the sucCD operon from P. aeruginosa PAO1.

A 20-kb EcoRI cosmid clone (pSU6) from P. aeruginosa PAO1 genomic library that hybridized to a 512-bp sucCD-specific probe (14) was isolated. A 3.5-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment was subcloned from pSU6 into pUC118 to generate pXL804. DNA sequencing was performed on both the strands and was analyzed by using the TRANSLATE and BLAST programs.

Overexpression and purification of the SCS α and β subunits.

To construct a plasmid for the overexpression of SucD (α subunit) from P. aeruginosa, PCR was performed using pXL804 as a template and a combination of oligonucleotides 1 and 2 (Table 1). The PCR was carried out in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 1× Pfu buffer, 2.5 mM concentrations of dNTPs, 2 ng of the template, and 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). The reaction was set to 30 cycles at 95°C for 2 min, 53°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min per cycle. A PCR product of about 864 bp was obtained, which was purified by using QiaQuick PCR purification (Qiagen Corp.). The purified DNA was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and was cloned into the compatible sites of pET28a to generate pKV153. Similarly, with pXL804 as a template and a combination of oligonucleotides 3 and 4 (Table 1), PCR was performed as described above to amplify a 1,164-bp DNA which encodes sucC (β subunit). The PCR-amplified DNA was purified, digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and cloned into pET28a to generate pKV152.

Both the constructs pKV153 (encoding the Scs α subunit) and pKV152 (encoding the Scs β subunit) were introduced into E. coli BL21(pLysS) for protein expression. Briefly, E. coli BL21(pLysS) cells containing pKV152 or pKV153 were grown in 100 ml of tryptone-yeast extract (with 0.1% glucose) medium in a 500-ml flask to an optical density of 0.5 to 0.6 and were then induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). The cells were further grown for 2 h and then harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer, treated with lysozyme (1 mg/ml) on ice for 30 min, and then lysed by using a sonicator (Branso Sonifer model 450). The lysed cells were pelleted at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was filtered by using a 0.22-μm (pore-size) filter. The proteins were purified by using a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) purification system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ni-NTA Spin-Kit; Qiagen Corp.). The purified proteins were dialyzed for 2 h with two changes of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 10 mM MgCl2 at 4°C.

Autophosphorylation and NDP kinase activities of the succinyl-CoA synthetase.

The purified Scs α and β subunits were tested for their autophosphorylation activity. Briefly, 3 μg of the purified proteins (Scs α and β subunits), along with various amounts of ADP or GDP (0, 5, 50 μM) and 1 μl (0.15 pmol) of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mM; Dupont NEN), was used for the autophosphorylation reaction. The reaction was carried out in a final 20-μl volume in TMD buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10 mM MgCl2; 25 mM KCl; 0.8 mM dithiothreitol) and was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 4 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer and was boiled for 10 min before electrophoresis. The samples were electrophoresed by SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The gel was exposed to a PhosphorImager cassette and was analyzed by using a STORM 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Succinyl-CoA synthetase activity was determined by the procedure described by Kavanaugh-Black et al. (10).

Using the purified Scs α and β subunits (3 μg) and 0.15 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP or 0.15 pmol of [γ-32P]GTP (3,000 Ci/mM; Dupont NEN) as a phosphodonor, the effect of various concentrations of NDP mixtures such as NDPI (GDP-CDP-UDP) or NDPII (ADP-CDP-UDP) were determined, respectively. The reaction was carried out in 20 μl of TMD buffer with NDP concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 mM. The nature of nucleotide synthesis by the Scs complex was determined by spotting 2 μl of the reaction mixture onto a PEI-TLC plate (Selecto Scientific, Norcross, Ga.) as described by Sundin et al. (24). To the remaining reaction mixture (18 μl), 4 μl of loading buffer was added to terminate the reaction. The samples were boiled for 10 min and were run on an SDS–12% PAGE gel. The gel was exposed to a phosphorimager cassette, and the amount of 32P bound to the Scs α subunit was determined by using the PhosphorImager (STORM 860; Molecular Dynamics). About 3 μg of the purified Scs α and β subunits was mixed with 100 μM succinyl-CoA (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) and inorganic [32P]Pi (10 μCi) in the form of orthophosphoric acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.), along with various concentrations of the NDPs in a 20-μl reaction volume. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. About 1.5 μl of the reaction was spotted onto a TLC-PEI plate and analyzed for the triphosphate synthesis.

The kinase activity of the Scs complex in the presence of Ndk was also evaluated. Equal amounts (3 μg) of the purified Scs α and β subunits were incubated with equal amounts of either 12- or 16-kDa Ndk in 20 μl of TMD buffer. The nucleotide synthesis assays were performed as described above using 50 μM NDPI or 50 μM NDPII and [γ-32P]ATP or [γ-32P]GTP as phosphodonors, respectively.

GenBank submission.

The DNA sequence encoding the succinyl-CoA synthetase is given under GenBank accession number AF128399.

RESULTS

Characterization of the sucCD operon from P. aeruginosa.

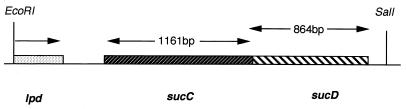

Using a 512-bp specific probe for sucCD, a 20-kb cosmid clone was identified by screening the P. aeruginosa PAO cosmid library. Further, a 3.5-kb DNA fragment containing the sucCD hybridizing fragment was subcloned and sequenced. The organization of the sucCD operon from P. aeruginosa is shown in Fig. 1. Translated DNA sequence analysis of pXL804 (from the EcoRI end) revealed a sequence similarity to the C-terminal region (52 amino acids) of dihyrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd gene product) from P. fluorescens (2). The sucCD operon (2,025 bp) is located 324 bp downstream from the lpd gene. The first gene transcribed in this operon is sucC, which is 1,161 bp and encodes the Scs β subunit (387 amino acids). The Scs β subunit shows 72% amino acid sequence identity to the E. coli Scs β subunit. The ATG of the sucD gene (864 bp) overlaps with the stop codon of the sucC gene. The sucD gene encodes the Scs α subunit (288 amino acids) and showed 89% amino acid sequence identity to the E. coli Scs α subunit. About 313 bp downstream of the sucCD operon is an open reading frame that encodes the branched-chain amino acid carrier protein (product of braB gene) in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (7).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the succinyl-CoA synthetase operon in P. aeruginosa PAO1. sucC encodes the β subunit, while sucD encodes the α subunit of the Scs enzyme. The EcoRI-SalI fragment also contains the 3′ region (129 bp) of the lpd gene.

Succinyl-CoA synthetase activity assays.

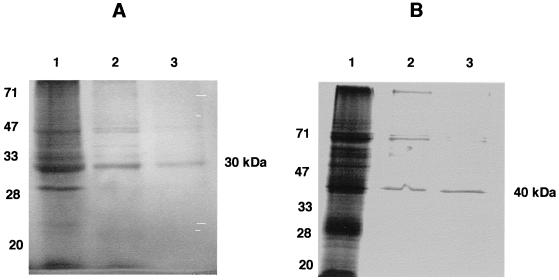

The Scs α subunit was purified by use of the Ni-NTA spin column and was analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. A 30-kDa protein corresponding to the predicted molecular size was obtained (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). Similarly, the Scs β subunit was purified by the Ni-NTA spin column and was analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. A 40-kDa protein corresponding to the predicted size was obtained (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3). The purified proteins were tested for activity by performing the phosphorylation of the Scs α subunit by using [γ-32P]ATP. Autophosphorylation was carried out in the presence of various amounts of ADP or GDP and by using [γ-32P]ATP as the phosphodonor. A 5 μM concentration of GDP in the reaction mixture stimulated the phosphorylation of the 30-kDa Scs α subunit, whereas 50 μM GDP in the reaction mixture showed a significant decrease. Similarly, 5 μM ADP in the reaction mixture weakly enhanced the phosphorylation, while 50 μM ADP did not have any effect (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Induction and purification of the P. aeruginosa His-tagged Scs α and β subunits overexpressed in E. coli. (A) Lane 1, E. coli BL21(pKV153) (induced); lanes 2 and 3, partially purified Scs α subunit obtained from the Ni-NTA column after the first and second elutions. (B) Lane 1, E. coli BL21(pKV152) (induced); lanes 2 and 3, partially purified Scs β subunit.

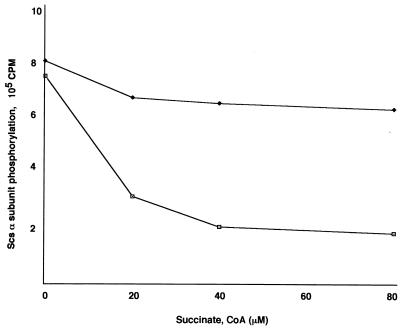

In order to test the activity of Scs β subunit, an Scs enzymatic reaction was performed with succinate, CoA, and a mixture of purified Scs α and β subunits (3 μg each) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. In this reaction the Scs enzyme converted succinate, CoA, and [γ-32P]ATP to succinyl-CoA, ADP, and Pi. The amount of the phosphorylated Scs α subunit (in presence of [γ-32P]ATP) and in the presence of equimolar amounts of succinate and CoA was determined by counting the 32P-labeled Scs α subunit. A loss of phosphorylation of the α subunit is an indication of the binding of the nucleotide to the catalytic site of the β-subunit of Scs. A rapid decrease in the phosphorylation of the Scs α subunit in the presence of 20 μM succinate and CoA was observed, but succinate alone in the reaction showed no decrease in autophosphorylation (Fig. 3). Similarly, CoA alone in the reaction had no effect on the Scs α subunit dephosphorylation (data not shown). Taken together, the data indicated that both succinate and CoA must be present to allow the reaction to proceed to completion.

FIG. 3.

Succinyl-CoA synthetase activity from P. aeruginosa, measured as the rate of dephosphorylation of the Scs α subunit. The purified Scs subunits were incubated with various amounts of succinate and CoA (□) or with succinate only (⧫) using [γ-32P]ATP as a phosphodonor.

NDP kinase activities of the Scs with [γ-32P]ATP or [γ-32P]GTP as phosphodonor.

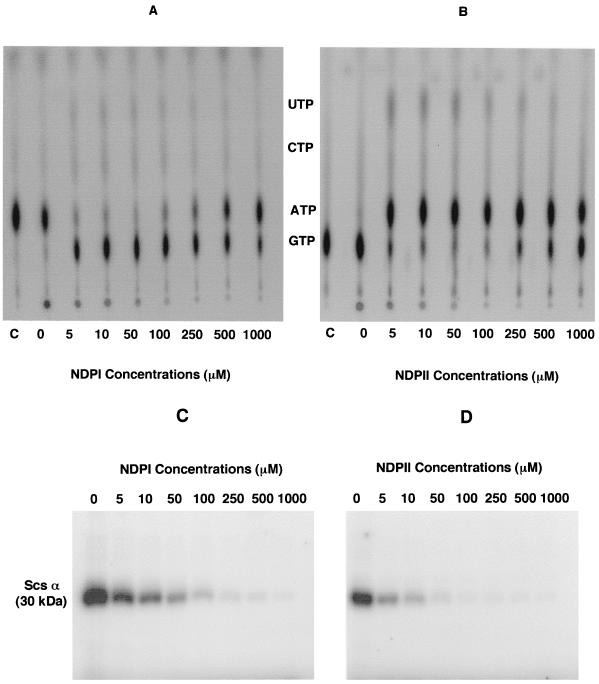

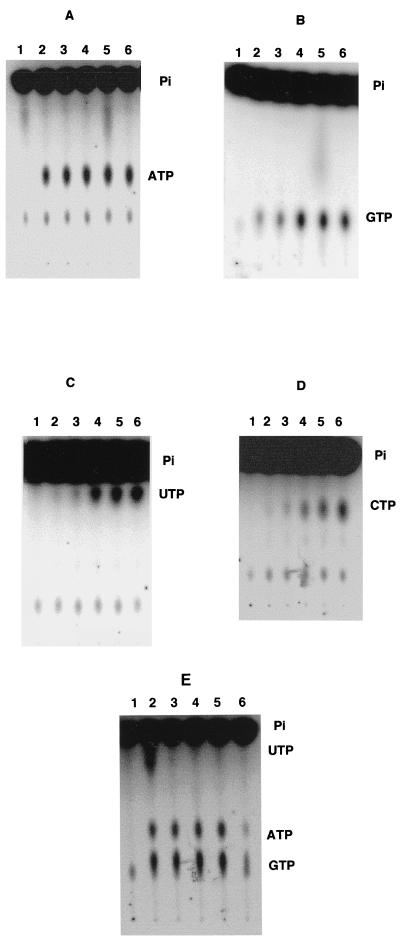

In order to determine if the purified Scs subunits exhibited kinase activity, we performed an NDP kinase reaction by using 3 μg of the purified protein with [γ-32P]ATP and various concentrations (0 to 1 mM) of NDPI (GDP-CDP-UDP) in a 20-μl volume. Two microliters of the reaction mixture was spotted onto a thin-layer chromatography plate, which was analyzed for NTP synthesis. The remaining reaction was terminated with 4 μl of stop buffer and was analyzed on an SDS–12% PAGE for the phosphorylated Scs α subunit. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the Scs complex transferred the terminal phosphate from [γ-32P]ATP to GDP to form GTP; higher concentrations (>100 μM) of the NDPI had an inhibitory effect on GTP synthesis, and a significant amount of [γ-32P]ATP remained unreacted (Fig. 4A). Very little UTP or CTP formation was observed. The corresponding phosphorylated Scs α subunit separated on an SDS–12% PAGE showed a progressive decrease in the level of phosphorylation with increasing NDP concentration, suggesting substrate-induced binding at the catalytic sites, leading to dephosphorylation and/or inhibition of phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). When [γ-32P]GTP was used as a phosphodonor and NDPII (ADP-CDP-UDP), ranging from 0 to 1,000 μM, were used as substrates in the reaction mixture, predominantly ATP synthesis was observed, although small amounts of UTP were also detected (Fig. 4B). The generation of ATP and UTP was optimum at an NDP concentration of 50 μM, beyond which there was progressive inhibition. A corresponding decrease in the amount of phosphorylated Scs α subunit was observed under increasing NDP concentrations (Fig. 4D). It appears that the P. aeruginosa Scs enzyme can generate either GTP or ATP and only traces of UTP, depending upon the relative NDP concentration. At a high NDP concentration (>100 μM), the kinase activity is significantly reduced with either ADP or GDP as a substrate.

FIG. 4.

(A) NDP kinase assays of the Scs α and β subunits from P. aeruginosa in the presence of various concentrations of NDPI (GDP, CDP, and UDP). Lane C, [γ-32P]ATP control. (B) ATP (and small amounts of UTP) synthesis by the Scs α and β subunits when [γ-32P]GTP is used as a phosphodonor in the presence of NDPII (ADP, CDP, and UDP). Lane C, [γ-32P]GTP control. (C and D) Autophosphorylation of the Scs α subunit with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of NDPI (GDP, CDP, and UDP) shown in panel C or with [γ-32P]GTP as a phosphodonor in the presence of NDPII (ADP, CDP, and UDP) shown in panel D.

NDP kinase activity of the Scs with inorganic Pi and succinyl-CoA.

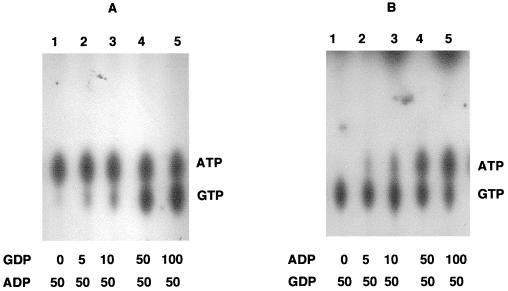

Using the purified Scs enzyme and inorganic [32P]Pi in the form of orthophosphoric acid and succinyl-CoA, we tested the succinyl-CoA synthetase enzyme activity in the presence of GDP, ADP, UDP, or CDP either individually or in combination. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and 1.5 μl of the reaction mixture was analyzed for NTP synthesis on a TLC-PEI plate. As shown in the Fig. 5A to D, either ADP or GDP could act as a substrate at the lowest concentration tested (50 μM), while UDP and CDP were active only at concentrations above 100 μM. When all of the NDPs (ADP, GDP, UDP, and CDP) were used in the reaction, GTP and ATP were the prominent products with traces of UTP as well (Fig. 5E). Based on these results, we conclude that the Scs enzyme exhibits NDP kinase activity with GDP = ADP > UDP > CDP with respect to its relative affinities for the NDPs. To further delineate the relative affinity of ADP and GDP as substrates, a substrate competition experiment was conducted at various concentrations in the presence of inorganic [32P]Pi, succinyl-CoA, and GDP or ADP. In one experiment, 50 μM ADP was added in the reaction mixture, along with various amounts of GDP. As shown in Fig. 6A, GTP synthesis was observed in the presence of ADP even when the concentration of GDP was 5 μM (Fig. 6A, lane 2). At equal concentrations, both GTP and ATP were synthesized in essentially equal amounts. Conversely, when GDP concentration was fixed at 50 μM and various concentrations of ADP were used, ATP synthesis was observed with as little as 5 μM ADP (Fig. 6B, lane 2), while at 50:50 concentrations, both ATP and GTP were synthesized in essentially identical amounts.

FIG. 5.

NDP kinase activity of the purified Scs enzyme with inorganic Pi, succinyl-CoA, and various concentrations of individual NDPs. (A to D) A, ADP; B, GDP; C, UDP; D, CDP. Lane 1, 0; lane 2, 50 μM; lane 3, 100 μM; lane 4, 500 μM; lane 5, 1 mM; lane 6, 2.5 mM. (E) NDP kinase activity of the purified Scs enzyme of P. aeruginosa with inorganic Pi, Succinyl-CoA and various concentrations of NDPs (ADP, GDP, CDP, and UDP). Lane 1, 0; lane 2, 50 μM; lane 3, 100 μM; lane 4, 500 μM; lane 5, 1 mM; lane 6, 2.5 mM.

FIG. 6.

Succinyl-CoA synthetase from P. aeruginosa utilizes GDP or ADP and synthesizes GTP or ATP, respectively, with radiolabeled Pi as a phosphodonor. (A) GTP synthesis by the Scs enzyme in the presence of 50 μM ADP in each lane with various micromolar amounts of GDP in the reaction mixture as indicated. (B) ATP synthesis by the Scs enzyme in the presence of 50 μM GDP in each lane with various micromolar amounts of ADP in the reaction mixture as indicated.

Modulation of 12-kDa Ndk activity by the α and β subunits of Scs.

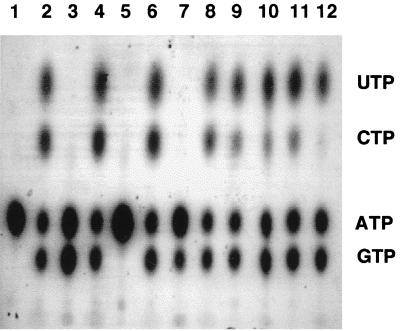

The Scs protein was shown to copurify with Ndk in P. aeruginosa (10). Ndk exists in two forms in mucoid P. aeruginosa, a cytoplasmic 16-kDa form capable of generating all of the NTPs and a 12-kDa membrane-associated form which forms complexes with pyruvate kinase, Pra, or EF-Tu, and these complexes predominantly use GDP as a substrate, generating GTP (5, 12, 18). Since Scs copurifies with Ndk, it was of interest to see if Scs modulates Ndk activity in any way. We therefore evaluated NTP synthesis by the 16- and 12-kDa forms of Ndk in the presence of the α and β subunits of Scs. As shown in Fig. 7, the Scs α subunit alone (lane 3) or a combination α and β subunits (lane 7) generated GTP in presence of GDP, CDP, and UDP. Either the 16-kDa Ndk or the 12-kDa Ndk generated all the three NTPS (GTP, CTP, and UTP) in the presence of the NDPs (lanes 2 and 9). The presence of Scs α, β, or both in association with the 16-kDa Ndk did not lead to any alteration of NTP synthesis (Fig. 7, lanes 4, 6, and 8). When the α and β subunits of Scs were separately present with 12-kDa Ndk, no appreciable change in the nature of NTP was observed (Fig. 7, lanes 9, 10, and 11). However, when both the α and β subunits of Scs were added with 12-kDa Ndk, very little CTP (<10%) was generated, suggesting that a complex of 12-kDa Ndk and Scs may modulate Ndk activity to primarily generate NTPs other than CTP at the NDP concentrations used.

FIG. 7.

Modulation of NDP kinase (Ndk) activity by the α and β subunits of Scs. Two forms of Ndk, a 16-kDa form and a truncated 12-kDa form obtained by treatment with purified elastase (9) were used. Lane 1, [γ-32P]ATP control; lane 2, 16-kDa Ndk; lane 3, Scs α; lane 4, Scs α plus 16-kDa Ndk; lane 5, Scs β; lane 6, Scs β plus 16-kDa Ndk; lane 7, Scs α plus Scs β; lane 8, Scs α plus Scs β plus 16-kDa Ndk; lane 9, 12-kDa Ndk; lane 10, Scs α plus 12-kDa Ndk; lane 11, Scs β plus 12-kDa Ndk; lane 12, Scs α plus Scs β plus 12-kDa Ndk. A 50 μM concentration of NDPI (GDP-CDP-UDP) was used in all of the reactions in addition to [γ-32P]ATP as described previously (24).

DISCUSSION

GTP plays a central role in cellular metabolism (21). Apart from its role in the synthesis of RNA, GTP is involved in a variety of cellular processes, including cellular signal transduction and protein synthesis, that require GTP-binding (G) proteins (4, 6, 18). GTP is also important in polysaccharide synthesis since GDP-mannose, which is derived from mannose 1-phosphate and GTP (17), is often an intermediate in the synthesis of mannose (or its uronic acid mannuronate)-containing polysaccharides. A pertinent example is the synthesis of the polysaccharide alginate by P. aeruginosa cells isolated from the lungs of CF patients (16). Such strains produce copious amounts of alginate. A molecule of alginate contains hundreds of mannuronate residues, the incorporation of each of which requires consumption of a molecule of GTP. Thus, synthesis of each molecule of alginate by mucoid P. aeruginosa requires the consumption of hundreds of molecules of GTP (4, 9). The transition of nonmucoid P. aeruginosa to mucoidy (alginate production) in the CF lung therefore requires that P. aeruginosa be able to specifically generate large amounts of GTP to allow production of large amounts of alginate. We previously reported that Ndk, which is normally responsible for all NTP formation in the cell, is important for alginate synthesis (24), since it forms complexes with a number of cellular proteins in P. aeruginosa and since such complexes generate predominantly GTP (4, 5). It should be noted, however, that GTP-generating complexes of Ndk with proteins such as pyruvate kinase or Pra (4, 5, 24) involves the truncated 12-kDa form of Ndk, which is generated uniquely in the mucoid cells by the periplasmic retention of elastase (9, 12). An ndk knockout mutant (27), while deficient in alginate synthesis, nevertheless, makes small amounts of alginate. Thus, we were interested in knowing what other enzymes may provide an alternative source of GTP. Besides Ndk, other kinases, such as pyruvate kinase (24), adenylate kinase (15), or polyphosphate kinase (13), can substitute for Ndk, generating NTPs, including GTP. Since Scs was previously shown to copurify with Ndk, presumably as a tight complex (10) and since Scs is known to generate either ATP or GTP (8, 19, 20), it was of interest to us to find out the nature of the Scs enzyme in P. aeruginosa and its putative role in GTP synthesis, with or without complexation with Ndk. Since very little is known about the Scs enzyme or its genetic organization in pseudomonads, our studies additionally provide important information about this TCA cycle enzyme.

The substrate level phosphorylation catalyzed by Scs is known to involve adenine nucleotides in plants as well as in prokaryotes such as E. coli generating ATP during the operation of the TCA cycle (19, 20). In contrast, Scs from eukaryotes such as pig heart (8) or Dictyostelium discoidium (1, 25, 26) is known to generate GTP. However, both ATP- and GTP-specific Scs isoforms have been characterized from multicellular eukaryotes (8) and, in general, the nucleotide preference varies widely within organisms (11, 20). It is interesting to note that the purified Scs α and β subunits of P. aeruginosa generate predominantly GTP from [γ-32P]ATP and a mixture of GDP, CDP, and UDP (Fig. 4A). It is, however, capable of transferring the terminal phosphate from GTP to ADP (Fig. 4B). Thus, in the presence of succinyl-CoA, Pi, and an equimolar mixture of ADP and GDP, P. aeruginosa Scs can efficiently synthesize almost an equimolar mixture of ATP and GTP. The Scs α subunit can be efficiently autophosphorylated either in presence of ATP or in presence of GTP, and small quantities of GDP or ADP can enhance such phosphorylation, while larger concentrations inhibit it, suggesting that intracellular concentrations of ADP and GDP modulate the interconversion of ATP and GTP by Scs. The stimulatory effect of low concentrations of GDP and ADP in the autophosphorylation of the α subunit of Scs may be due to binding to a high-affinity allosteric site (3, 26) of Scs. The stimulation of Scs phosphorylation by GDP is well documented in the case of eukaryotes (8, 25), but it also occurs in P. aeruginosa.

In this study we also demonstrate that P. aeruginosa Scs enzyme exhibits NDP kinase activity and can synthesize GTP, ATP, UTP, and CTP by using inorganic Pi and the corresponding diphosphates. Both GDP or ADP were equally preferred at lower concentrations; however, at higher concentrations CDP and UDP could also be used. Since the intracellular level of NDPs may reach millimolar concentrations, it is conceivable that P. aeruginosa Scs may generate all of the NTPs under certain conditions. We also considered the possibility that the broad NDP substrate range of P. aeruginosa Scs is due to trace contamination with Ndk, since Ndk is known to copurify with Scs (10). However, Ndk uses only NTPs such as ATP or GTP as a phophodonor, not Pi. When we tested the ability of purified P. aeruginosa Ndk to generate any NTP from a mixture of Pi, succinyl-CoA, and ADP-GDP-CDP-UDP, no NTP formation was detected (data not shown). Thus, the formation of UTP or CTP by Scs is not due to contamination with Ndk.

The loss of CTP synthesis by Scs, when complexed with the 12-kDa form of Ndk, is interesting. Unlike pyruvate kinase or Pra, which generates predominantly GTP in complexation with the 12-kDa form of Ndk (5, 24), Scs–12-kDa-Ndk complexes generated both UTP and GTP. It is unclear if such a complex plays any role in generating the GTP involved in alginate synthesis or if Scs is involved in residual alginate synthesis by the ndk knockout mutant cells. The availability of the scs genes will now allow us to make double knockout mutations in both ndk and scs genes to examine the extent of alginate synthesis by such a double mutant if it is viable.

Finally, nothing is known about the regulation of Scs in P. aeruginosa. In E. coli, the sucCD operon encoding the α and β subunits of Scs is part of sucABCD operon, where sucAB encodes α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, forming a single transcript. The oxygen and carbon control of sucABCD gene expression has been shown to occur by transcriptional regulation of the upstream sdhC promoter (22). A weak sucABCD promoter upstream also allows a low constitutive level of this operon expression, whereas the negative regulation seen under anaerobic conditions is mediated by arcA and fnr gene products (22). Since the organization of the sucCD operon in P. aeruginosa differs from that of E. coli and the P. aeruginosa Scs has a different specificity for NTP production, it is likely that the regulation of Scs in P. aeruginosa would be markedly different from that of E. coli. Such studies are currently under way in our laboratory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bob Hancock for providing the sucCD probe and the P. aeruginosa PAO1 library. We thank T. K. Misra for technical help on protein purification and Page Goodlove for DNA sequencing at the DNA Sequencing Facility of the University of Illinois at Urbana.

This work was funded by Public Health Service grant AI-16790-18 from The National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anschutz A L, Um H-D, Siegel N R, Veron M, Klein C. P36, a D. discoideum protein whose phosphorylation is stimulated by GDP, is homologous to the α-subunit of succinyl-CoA synthetase. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1993;1162:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90125-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benen J A, Van Berkel W, Van Dongen M, Muller F, de Kok A. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of the lpd gene encoding lipoamide dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1787–1797. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-7-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birney M, Um H-D, Klein C. Novel mechanisms of Escherichia coli succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase regulation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2883–2889. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2883-2889.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarty A M. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase: role in bacterial growth, virulence, cell signaling and polysaccharide synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:875–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopade B A, Shankar S, Sundin G W, Mukhopadhyay S, Chakrabarty A M. Characterization of membrane-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ras-like protein Pra, a GTP binding protein that forms complexes with truncated nucleoside diphosphate kinase and pyruvate kinase to modulate GTP synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2181–2188. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2181-2188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilman A G. G-protein: transducers of receptor induced signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino T, Kose K, Uratani Y. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene braB coding for the sodium-coupled branched-chain amino acid carrier in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220:461–467. doi: 10.1007/BF00391754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J D, Mehus J G, Tews K, Milavetz B I, Lambeth D O. Genetic evidence for the expression of ATP and GTP specific succinyl-CoA synthetase in multicellular eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27580–27586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamath S, Kapatral V, Chakrabarty A M. Cellular function of elastase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: role in the cleavage of nucleoside diphosphate kinase and in alginate synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:933–941. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavanaugh-Black A, Connolly D M, Chugani S A, Chakrabarty A M. Characterization of nucleoside diphosphate kinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: complex formation with succinyl-CoA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5883–5887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly C J, Cha S. Nucleotide specificity of succinate thiokinases from bacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;178:208–217. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H Y, Schlictman D, Shankar S, Xie Z, Chakrabarty A M, Kornberg A. Alginate, inorganic polyphosphate, GTP and ppGpp synthesis co-regulated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for stationary phase survival and synthesis of RNA/DNA precursors. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:717–725. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda A, Kornberg A. Polyphosphate kinase as a nucleoside diphosphate kinase in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:439–442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao X, Charlebois I, Ouellet C, Morency M J, Dewar K, Lightfoot J, Foster J, Siehnel R, Schweizer H, Lam J S, Hancock R E W, Levesque R C. Physical mapping of 32 genetic markers on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 chromosome. Microbiology. 1996;142:79–86. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Q, Inouye M. Adenylate kinase complements nucleoside diphosphate kinase deficiency in nucleotide metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5720–5725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May T B, Chakrabarty A M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: genes and enzymes of alginate biosynthesis. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:151–157. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May T B, Shinabarger D, Boyd A, Chakrabarty A M. Identification of amino acid residues involved in the activity of phosphomannose isomerase-guanosine 5′-diphospho d-mannose pyrophosphorylase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4872–4877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukhopadhyay S, Shankar S, Walden W, Chakrabarty A M. Complex formation of the elongation factor Tu from P. aeruginosa with nucleoside diphosphate kinase modulates ribosomal GTP synthesis and peptide chain elongation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17815–17820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami K, Mitchell T, Nishimura J S. Nucleotide specificity of Escherichia coli succinic thiokinase. Succinyl-coenzyme A stimulated nucleoside diphosphate kinase activity of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:6247–6252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimura J S. Succinyl-CoA synthetase structure-function relationships and other considerations. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1986;58:141–172. doi: 10.1002/9780470123041.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pall M L. GTP, a central regulator of cellular anabolism. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1985;25:1–20. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152825-6.50005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S-J, Chao G, Gunsalus R P. Aerobic regulation of the sucABCD genes of Escherichia coli which encode α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and succinyl-coenzymeA synthetase: roles of ArcA, Fnr, and the upstream sdhCDAB. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4138–4142. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4138-4142.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlictman D, Kavanaugh-Black A, Shankar S, Chakrabarty A M. Energy metabolism and alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: role of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6023–6029. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6023-6029.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundin G W, Shankar S, Chugani S A, Chopade B A, Kavanaugh-Black A, Chakrabarty A M. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: characterization of the gene and its role in cellular growth and exopolysaccharide alginate synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:965–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Um H-D, Klein C. Dual role of GDP in the regulation of the levels of P36 phosphorylation in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Protein Chem. 1991;10:391–401. doi: 10.1007/BF01025253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Um H-D, Klein C. Evidence for allosteric regulation of succinyl CoA synthetase. Biochem J. 1993;295:821–826. doi: 10.1042/bj2950821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaborina O, Misra N, Kostal J, Kamath S, Kapatral V, El-Azami El-Idrissi M, Prabhakar B S, Chakrabarty A M. P2Z-independent and P2Z receptor-mediated macrophage killing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5231–5242. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5231-5242.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]