Abstract

The soxRS response, which protects cells against superoxide toxicity, is triggered by the oxidation of SoxR, a transcription factor. Superoxide excess and NADPH depletion induce the regulon. Unexpectedly, we found that the overproduction of desulfoferrodoxin, a superoxide reductase from sulfate-reducing bacteria, also induced this response. We suggest that desulfoferrodoxin interferes with the reducing pathway that keeps SoxR in its inactive form.

Escherichia coli has developed specific defenses to cope with toxicity of the superoxide radical, a by-product of oxygen. These include the superoxide dismutases (SODs) and a global response, governed by soxRS (11). SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] transcription factor, is oxidized in response to a signal of oxidative stress (6, 9, 14) and activates transcription of the soxS gene. SoxS in turn activates transcription of the genes of the soxRS regulon (23, 27). A crucial unanswered question concerns the nature of the signal detected by SoxR. Superoxide was the first candidate suggested for this signal because it could directly oxidize SoxR and because the soxRS regulon is induced by superoxide generators, such as paraquat (12). However, the following evidence has accumulated against such a simple mechanism. (i) The soxRS regulon is induced by nitric oxide, in the absence of oxygen (22). (ii) Depletion of NADPH increases the response of cells to paraquat, which consumes NADPH to produce superoxide. This led Liochev and Fridovich to suggest that the redox state (NADPH/NADP+ ratio) of the cells might act as a signal (19). (iii) In vitro, SoxR readily autooxidizes (13, 26). These results are consistent with the fact that SoxR is maintained in vivo in the reduced, inactive form by an unknown electron pathway (8, 15). Thus, the soxRS regulon may be induced by any event interfering at some level of that redox pathway.

Recently, we isolated an iron protein, desulfoferrodoxin (Dfx) (the product of rbo) from a sulfate-reducing bacterium that fully complemented an E. coli mutant lacking cytoplasmic SODs (24). While investigating the protection against superoxide afforded by Dfx, we unexpectedly found that its overproduction induced the soxRS regulon. In this study, we investigated the induction of the soxRS regulon in response to various signals and attempted to elucidate the level of the signaling pathway at which Dfx interferes.

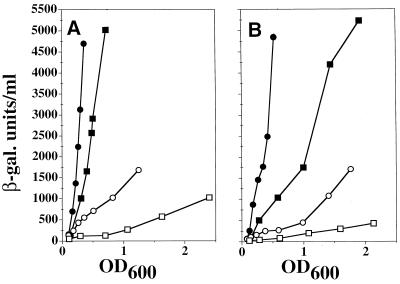

Several reports have supported the idea that O2⨪ induces the genes of the soxRS regulon (18, 23). However, we were disturbed by the contradictory results published by Gort and Imlay, who did not observe induction of soxS in a SOD-deficient strain (10). We investigated the reasons for this difference in results by generating a new set of strains carrying the soxS′-lacZ fusion (Table 1). sodA and sodB mutations derived from QC779 were introduced into TN521 by P1 transduction and the sodA sodB mutant (QC2733) was screened for its inability to grow on minimal medium (2). We compared induction between wild-type (TN521) and sodA sodB (QC2733) derivative strains by performing kinetic experiments (exponential phase) to measure steady-state-specific β-galactosidase activity. The level of soxS induction was four to five times higher in the sodA sodB mutant (Fig. 1A) but returned to wild-type levels in the presence of a plasmid (pDT1-5) producing MnSOD (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with the strains used by Gort and Imlay (10, TN530 and AS358 (Fig. 1B). However, the level of superoxide-mediated induction in TN530 was lower despite strains TN521 and TN530 being almost identical. The lower level of induction in TN530 is probably due to the titration of SoxR, which is thought to be limiting in the cells. Indeed, TN530 has two soxS promoters, one being at the soxRS locus and the other being in the soxS′-lacZ fusion, whereas TN521 has only one, as the soxRS locus is deleted (23). Consistently, TN530 was less sensitive than TN521 to other soxRS inducers (compare levels of induction by paraquat in Fig. 1). This low level of superoxide-mediated induction in TN530 and a single measurement at low cell concentration may account for the lack of induction in Gort and Imlay's experiment. As previously observed for other genes of the soxRS regulon (3, 4), soxS′-lacZ expression under aerobic conditions was slightly stronger in the wild type than in the ΔsoxRS mutant (Fig. 2), indicating that normal aerobic metabolism weakly induced the soxRS regulon.

TABLE 1.

E. coli K-12 bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| GC4468 | F− Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 rpsL | R. D'Ari |

| QC779 | Same as GC4468 but (sodA::MudIIPR13)25 Φ(sodB::kan)1-Δ2; Cmr Kmr | 2 |

| HB351 | W3110 Δ(argF-lac)U169 zeb-1::Tn10 Δ(edd-zwf)22 λDR52; Apr Tcr | 1 |

| TN521 | GC4468 λ(soxR+ soxS′-lacZ) ΔsoxRS901 zjc2204::Tn10kan; Kmr | 23 |

| TN530 | GC4468 λ(soxS′-lacZ) | 23 |

| QC2733 | Same as TN521 but (sodA::MudIIPR13)25 Φ(sodB::kan)1-Δ2zdh::Tn10; Tcr Cmr Kmr | This work |

| AS358 | Same as TN530 but (sodA::MudIIPR13)25 Φ(sodB::kan)1-Δ2; Cmr Kmr | 10 |

| TN531 | GC4468 λ(soxS′-lacZ) ΔsoxRS901 zjc2204::Tn10kan; Kmr | 23 |

| QC2785 | Same as TN530 but zeb-1::Tn10 Δ(edd-zwf)22; Tcr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJF119EH | Expression vector carrying ptac promoter; Apr | 24 |

| pMJ25 | pJF119EH derivative carrying the dfx+ (rbo+) gene under the ptac promoter control; Apr | 24 |

| pDT1-5 | pBR322 derivative carrying the sodA+ gene under the ptac promoter control; Apr | 25 |

FIG. 1.

Induction of soxS′-lacZ in SOD-deficient strains. The wild-type (square) and the derivative sodA sodB (circle) strains carrying the soxS′-lacZ fusion were cultured in LB medium and assayed for β-galactosidase (β-gal.) activity as described by Miller (21). The y axis shows β-galactosidase expressed in Miller units per milliliter multiplied by optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Values are the means of at least two experiments that differed by less than 20%. Open symbols, growth in LB medium; closed symbols, addition of 50 μM paraquat to the culture at an OD600 of about 0.1. (A) Squares, TN521; circles, QC2733. (B) Squares, TN530; circles, AS358.

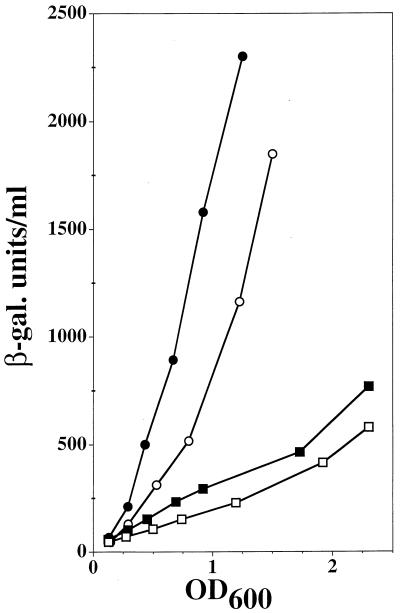

FIG. 2.

Effects of zwf deletion on paraquat-mediated soxS′-lacZ induction. The wild-type strain (TN530) (open symbols) and the derivative Δzwf (QC2785) (closed symbols) were untreated (squares) or treated with 5 μM paraquat (circles). See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details.

Although superoxide can directly induce the soxRS response, our results and those of others (7, 10, 19, 25) clearly show that a change in [O2⨪] was not the primary signal in induction by paraquat. Indeed, the presence of an excess of SOD did not significantly reduce induction (data not shown) (10). Thus, paraquat acts at a point in the signaling pathway different from that for superoxide. It has been suggested that redox cycling of paraquat may deplete the electron source (NADPH) of or divert electrons from the unknown system that keeps SoxR in its reduced, inactive form (19). Evidence for such a mechanism was provided by observations that sodA and fumC, both soxRS regulon genes, were more strongly inducible by paraquat treatment in a zwf mutant (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) than in a control strain. As sodA and fumC are multiregulated (4), we wanted to confirm that the effect of zwf mutation on induction by paraquat was soxRS dependent. A zwf deletion was introduced by transduction from HB351 into TN530. Transductants were screened for loss of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity (16). A slight increase (1.6 times) in soxS expression was seen in the zwf mutant in the absence of any other inducers (Fig. 2). Upon paraquat treatment, the level of induction was slightly higher in the mutant than in the wild type, as previously observed with sodA and fumC by Liochev and Fridovich (19), providing further evidence that NADPH acts as a signal (Fig. 2). The effect of zwf deletion was small, probably because there are other sources of NADPH in the cell. It is also possible that the extent of NADPH depletion produced by the zwf deletion is much smaller than that due to the redox cycling of paraquat. However, these results do not exclude the possibility that paraquat also triggers the soxRS response via another unknown mechanism.

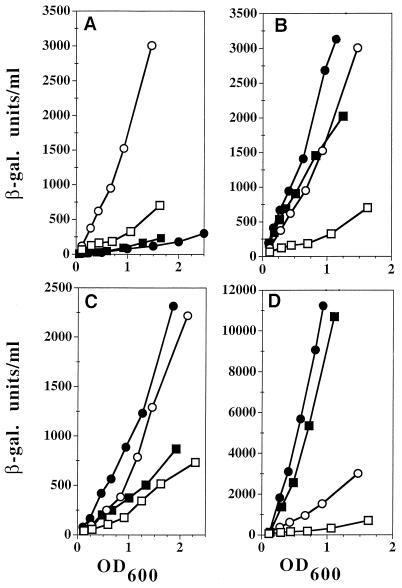

We predicted that, if the protective effect of Dfx were due to scavenging of superoxide, the superoxide-mediated induction of genes of the soxRS regulon would be decreased by Dfx. Surprisingly, we found that Dfx gave higher levels of induction (five to six times higher) in the SOD-proficient control strains (Fig. 3A). The effect was soxRS dependent (Fig. 3A) and oxygen dependent (data not shown), demonstrating that Dfx somehow triggers the soxRS response. However, in a strain overproducing Dfx, induction by superoxide (in a sodA sodB mutant) was weaker (with a level of induction only 1.6 times higher than that in the wild type), consistent with Dfx having superoxide scavenging activity (Fig. 3B). Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that reduced Dfx has superoxide reductase activity (20). Thus, Dfx may interfere with the SoxR reduction pathway at two levels: it may divert electrons directly from SoxR reductase, or/and it may deplete the electron source. Cytosolic and membrane fractions from E. coli crude extracts can reduce Dfx in vitro, using NADPH and NADH, respectively (20), but no Dfx diaphorase has yet been identified. In vivo depletion in NADPH, in a Δzwf mutant, did not affect the Dfx-mediated induction of soxS (Fig. 3C), whereas it did affect paraquat-mediated induction. This suggests that Dfx does not induce soxS by NADPH depletion. Induction by paraquat was stronger in a Dfx-overproducing strain (Fig. 3D). As induction by paraquat is very strong and liable to saturation, this small increase appears significant and probably reflects additive effects of paraquat and Dfx interference at two different points in the SoxR reduction pathway. This, together with current failures to isolate mutants in the reductive pathway, may reflect the existence of multiple ways to reduce SoxR.

FIG. 3.

Induction of soxS′-lacZ by Dfx. The experiment was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 except that the cultures were supplemented with 2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Open symbols, control strains; closed symbols, mutated strains. (A) SoxR dependence of induction. The strains (TN521, TN531) were transformed with pJF119EH (□, ■) and the Dfx-overproducing plasmid pMJ25 (○, ●). (B) Effect of SOD deficiency. The control strain (TN521) and the derivative sodA sodB strain (QC2733) were transformed with pJF119EH (□, ■) and pMJ25 (○, ●). (C) Effect of zwf deletion. The control strain TN530 and the derivative Δzwf strain, QC2785, were transformed with pJF119EH (□, ■) and pMJ25 (○, ●). (D) Effect of paraquat. TN521 was transformed with pJF119EH (□, ■) and with pMJ25 (○, ●). (The experiment was performed as described for panel A except that the cells were untreated (open symbols) or treated with 50 μM paraquat (closed symbols).

This work shows how interference with the SoxR reduction pathway plays an important role in triggering the soxRS protective response. Although some inducers, such as superoxide and nitric oxide, could directly oxidize SoxR, the more potent inducers (and possibly also superoxide and nitric oxide) act by interfering with the reduction pathway. It is still unclear whether there is only one pathway, and the SoxR reductase, a major component of this pathway, has not yet been identified. Recently, Kobayashi and Tagawa have isolated an enzyme that reduces SoxR by using NADPH (17), but it has not yet been characterized. We are currently trying to identify Dfx reductases, which should help to elucidate further the SoxR reduction pathway. The redox switch that activates SoxR is a well-adapted and versatile system for very rapidly triggering the soxRS protective response (5). The sensitivity of the reduction pathway or pathways to multiple signals enables the system to respond not only to direct oxidative stress but also to a wide range of environmental and intracellular changes indicative of possible oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. A. Imlay, B. Demple, and R. E. Wolf for providing strains.

This work was supported by a grant (no. 9175) from l'Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer. Philippe Gaudu was supported by a grant from la Fondation de la Recherche Médicale.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker H V, Wolf R E. Growth rate-dependent regulation of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase level in Escherichia coli K-12:β-galactosidase expression in gnd-lac operon fusion strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:771–781. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.771-781.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlioz A, Touati D. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli:is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 1986;5:623–630. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan E, Weiss B. Endonuclease IV of Escherichia coli is induced by paraquat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3189–3193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compan I, Touati D. Interaction of six global transcription regulators in expression of manganese superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1687-1696.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demple B. Redox signaling and gene control in the Escherichia coli soxRS oxidative stress regulon. Gene. 1996;179:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding H, Hidalgo E, Demple B. The redox state of the [2Fe-2S] clusters in SoxR protein regulates its activity as a transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33173–33175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fee J A. Regulation of sod genes in Escherichia coli:relevance to superoxide dismutase function. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2599–2610. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaudu P, Moon N, Weiss B. Regulation of the soxRS oxidative stress regulon. Reversible oxidation of the Fe-S centers of SoxR in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5082–5086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaudu P, Weiss B. SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] transcription factor, is active only in its oxidized form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10094–10098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gort A S, Imlay J A. Balance between endogenous superoxide stress and antioxidant defenses. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1402–1410. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1402-1410.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg J T, Monach P, Chou J H, Josephy P D, Demple B. Positive control of a global antioxidant defense regulon activated by superoxide-generating agents in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan H M, Fridovich I. Regulation of the synthesis of superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. Induction by methyl viologen. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7667–7672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo E, Demple B. An iron-sulfur center essential for transcriptional activation by the redox-sensing SoxR protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:138–146. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidalgo E, Ding H, Demple B. Redox signal transduction via iron-sulfur clusters in the SoxR transcription factor. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidalgo E, Ding H, Demple B. Redox signal transduction:mutations shifting [2Fe-2S] centers of the SoxR sensor-regulator to the oxidized form. Cell. 1997;88:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao S M, Hassan H M. Biochemical characterization of a paraquat-tolerant mutant of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10478–10481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi K, Tagawa S. Isolation of reductase for SoxR that governs an oxidative response regulon from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liochev S I, Benov L, Touati D, Fridovich I. Induction of the soxRS regulon of Escherichia coli by superoxide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9479–9481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liochev S I, Fridovich I. Fumarase C, the stable fumarase of Escherichia coli, is controlled by the soxRS regulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5892–5896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombard M, Fontecave M, Touati D, Nivière V. Reaction of the desulfoferrodoxin from Desulfoarculus baarsii with superoxide anion. Evidence for a superoxide reductase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;295:115–121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunoshiba T, DeRojas-Walker T, Wishnok J S, Tannenbaum S R, Demple B. Activation by nitric oxide of an oxidative-stress response that defends Escherichia coli against activated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9993–9997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunoshiba T, Hidalgo E, Amabile-Cuevas C F, Demple B. Two-stage control of an oxidative stress regulon:the Escherichia coli SoxR protein triggers redox-inducible expression of the soxS regulatory gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6054–6060. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6054-6060.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pianzzola M J, Soubes M, Touati D. Overproduction of the rbo gene product from Desulfovibrio species suppresses all deleterious effects of lack of superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6736–6742. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6736-6742.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Touati D. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase biosynthesis in Escherichia coli, studied with operon and protein fusions. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2511–2520. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2511-2520.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Dunham W R, Weiss B. Overproduction and physical characterization of SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] protein that governs an oxidative response regulon in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10323–10327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Weiss B. Two-stage induction of the soxRS (superoxide response) regulon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3915–3920. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3915-3920.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]