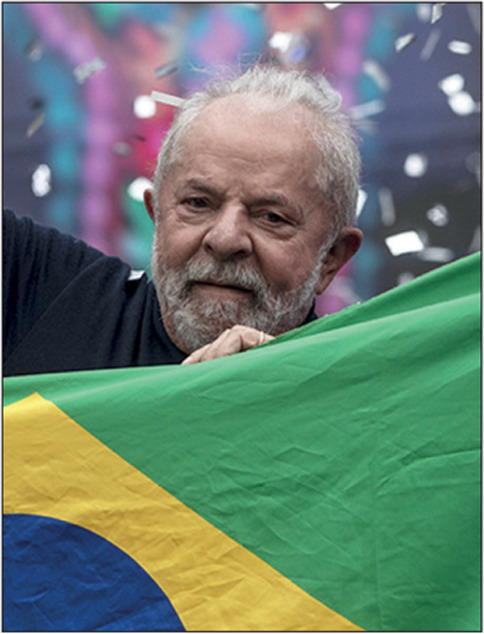

The stakes are high for Brazil's upcoming Presidential election. If current predictions are correct, President Jair Bolsonaro will be defeated by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, either in the first round of voting on Oct 2, or in a run-off on Oct 30. However, the gap between the candidates has been narrowing. There are fears in the country that Bolsonaro, who is known for his volatility and indirect incitement of violence, will not go quietly. He has already criticised Brazil's electronic voting system in the presence of foreign ambassadors.

Bolsonaro's disastrous handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and his disrespect for women, ethnic minorities, Indigenous people, and the environment are widely known. During Bolsonaro's reign, social protection measures have been undermined by curtailed funding, inequalities and poverty have risen sharply, and Brazil has again joined the UN Hungermap. According to data from the 2nd National Survey on Food Insecurity released in June, an estimated 30·7% of Brazilians are experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity due to a combination of the pandemic, increasing unemployment, weakening of social programmes, and dismantling of public welfare policies. More than 3·5 years of the Bolsonaro regime have left Brazil in its worst position for decades. The perennial issues of inequality, poverty, and corruption continue to harm Brazilians and their health. Gender-based and gun violence are still rampant and Bolsonaro's decision to relax gun laws was a step in the wrong direction. Correspondence published in The Lancet has described how scientists and scientific institutions have been undermined. Brazil needs an urgent change.

If the predictions for Brazil's election are correct, it will join other Latin American countries where there is a renewed hope for progressive societal change. The two most recently elected leaders in Latin America are Gustavo Petro (in Colombia), an ex-Guerrilla fighter who took office in August, and Gabriel Boric (in Chile), in office since March 11. Although many Latin American leaders are elected on pledges to renew health and education, fight corruption and poverty, and protect workers’ rights, many have not yet delivered substantive change. How Boric and Petro differ is in the inclusion of climate protection and sustainability, protection of women's rights, and political inclusion of ethnic minorities in their manifestos.

For the first time in Chile's history, most of the cabinet and half of ministers are women. The Vice President of Colombia is Francia Márquez, an Afro-Colombian environmental and human rights activist. Boric has a strong environmental agenda with a clear understanding that fossil fuels belong in the past, something of an exception in a region where many governments still support mining and oil exports. On Sept 4, Chileans will vote in a referendum on a new constitution, which includes the right to elective abortion and states that the national health system is universal. Petro has pledged to fight inequality by providing free university education, pension reforms, and high taxes on unproductive land. The challenges are huge, but his government has already announced an ambitious new progressive tax plan aimed at raising trillions of dollars for anti-poverty and social welfare programmes.

The region also needs a strong leading health organisation to support member states in their efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of their populations. A new director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) will be chosen in a secret ballot at the 30th Pan American Sanitary Conference on Sept 26–30. Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Haiti, and Uruguay have all nominated candidates and the new director will begin a 5-year term on Feb 1, 2023. Financial stability is high on the candidates’ agenda as PAHO was close to insolvent in 2020, during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with member states delaying payments and the USA under President Trump halting their support of WHO. But PAHO also needs a clearly prioritised agenda, most pressingly, to examine the lessons learnt and changes needed for the region after the pandemic. PAHO needs an energetic leader who commands political as well as technical respect among member states and who is not afraid to take risks or hold countries accountable for their actions on health.

There is an unprecedented chance for new beginnings in Latin America; an opportunity to make positive changes to alleviate deep neglect, inequality, and violence. Let us hope that Brazil chooses to seize this opportunity.

For more on food poverty in Brazil see https://olheparaafome.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Relatorio-II-VIGISAN-2022.pdf

For more on how Brazilian scientists and science have been undermined see Correspondence Lancet 2021; 397: 373–74 and Correspondence Lancet 2022; 399: 23–24

For more on Columbia's tax programme see https://www.ft.com/content/35d3eae3-5166-42f6-b0b0-a66c6c709116

For more on the candidates for PAHO Director see World Report Lancet 2022 399: 2337–38

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on September 6, 2022

© 2022 Bloomberg