Abstract

Objective:

Widespread concern exists about the impacts of COVID-19 and related public health safety measures (e.g., school closures) on adolescent mental health. Emerging research documents correlates and trajectories of adolescent distress, but further work is needed to identify additional vulnerability factors that explain increased psychopathology during the pandemic. The current study examined whether COVID-19-related loneliness and health anxiety (assessed in March 2020) predicted increased depressive symptoms, frequency of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and suicide risk from pre-pandemic (late January/early February 2020) to June 2020.

Method:

Participants were 362 middle and high school adolescents in rural Maine (M age = 15.01 years; 63.4% female; 76.4% White). Data were collected during a time in which state-level COVID-19 restrictions were high and case counts were relatively low. Self-reports assessed psychopathology symptoms, and ecological momentary assessment (EMA) was used to capture COVID-19-related distress during the initial days of school closures.

Results:

Loneliness predicted higher depressive symptoms for all adolescents, higher NSSI frequency for adolescents with low pre-pandemic frequency (but less frequent NSSI for adolescents with high pre-pandemic frequency), and higher suicide risk for adolescents with higher pre-pandemic risk. Health anxiety predicted higher NSSI frequency for adolescents with high pre-pandemic frequency, and secondary analyses suggested that this pattern may depend on adolescents’ gender identity.

Conclusions:

Results underscore the impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health, with benefits for some but largely negative impacts for most. Implications for caretakers, educators, and clinicians invested in adolescent mental health are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, adolescence, depression, NSSI, suicide, health anxiety, loneliness

Families and healthcare professionals are concerned about the impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on youths’ well-being. Perhaps second only to fears of contracting the virus are concerns about the effects of necessary public health measures, such as physical distancing and school closures, on mental health (Ellis et al., 2020). As adolescence is a period of sensitivity to both positive and negative experiences (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002), the potential for COVID-19 to affect well-being during this stage is pronounced. Understanding the extent of impact is critical for bolstering systems to support adolescents’ development. Emerging data underscores pandemic effects on psychological adjustment (Alt et al., 2021; vanLoon et al., 2021). With assessments spanning from pre- to post-COVID-19 school closures, this study was uniquely situated to add to this literature by testing impacts of COVID-19-related health anxiety and loneliness on adolescents’ depressive symptoms, non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and suicide risk. Findings have the potential to inform our understanding of a) the distress caused by sudden disruptions in social routines and widespread concern about health and b) how pandemic distress may have influenced continuity and change in adolescents’ mental health.

Developmental Significance of COVID-19 for Adolescents

COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. The first US case is thought to have occurred in Washington State in January 2020, just before the World Health Organization declared a global health emergency, and cases then spread across the US. On March 15, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control issued guidance for limiting group gatherings, and many US schools closed to in-person learning. Remote learning commenced, and physical distancing recommendations limited exposure to persons outside of the home, including peers.

Although COVID-19 has affected individuals of all ages, its impacts on adolescents may be unique. One aspect of adolescence that distinguishes it from earlier developmental periods is the increased incidence of mental health problems. Risk for depression increases at adolescence (Avenevoli et al., 2015), adolescents engage in the highest documented rates of NSSI (Giletta et al. 2012), and suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescence (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). The literature identifies many protective factors, but also risk factors, including exposure to environmental stress (Agid et al., 2000). Environmental stressors (e.g., catastrophic events) have been closely linked with onset of depression (Mazurka et al., 2016), engagement in NSSI (Gratz, 2013), and suicidal ideation and behavior (Brent, 1995). COVID-19 could be considered one such environmental stressor and has even been labeled a “collective trauma” (Watson et al., 2020) with which nearly all adolescents have been forced to cope. Adolescents with existing mental health difficulties may face even greater pandemic-related challenges (e.g., Breaux et al., 2020; Rousseau & Miconi, 2020). Thus, it is important to examine whether and how adolescents experienced changes in mental health in the wake of COVID-19.

A second aspect of adolescence that may further contribute to the pandemic’s effects is the increased influence of friends on adolescents’ adjustment (see Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020). More so than in childhood, friendships in adolescence involve increased self-disclosure and emotional closeness, enabling youth to obtain support and better regulate emotion (Compas et al., 2017). School closures, bans on group gatherings and extracurricular activities, and social distancing rendered adolescents physically separate from the context in which these key developmental tasks are honed, almost overnight. Initial data underscore that adolescents view changes in friendships as their biggest pandemic challenge (Magson et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2020). They perceive their friendships as less close (Rogers & Ockey, 2020), and although lonely adolescents increased social media use to cope with reduced in-person social contact, their happiness did not significantly improve as a result (Cauberghe et al., 2020). To this end, it is reasonable to expect that changes in peer relationships may negatively affect their mental health.

Data on COVID-19 and Adolescent Health

Studies published since the start of the pandemic accentuate concerns about mental health (Racine et al., 2021). Adolescents are worried about COVID-19 (Nelson et al., 2020), and cross-sectional data links pandemic stress to more loneliness and depression, even if youth spend more time online with friends (Ellis et al., 2020). Further, social distancing is associated with greater social disconnection, isolation, and unhappiness (Munasinghe et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2020).

Rising levels of psychopathology.

Longitudinal data further suggest that depression and self-destructive behavior may be increasing. Several studies documented increased depressive symptoms from pre-pandemic levels (Alt et al., 2021; Barendse et al., 2021; Hollenstein et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021; Penner et al., 2020; see Racine et al., 2021). Adolescent NSSI also appears to be increasing due to COVID-19 stress and particularly for those who self-injured pre-pandemic (Carosella et al., 2021; Steinhoff et al., 2021). Further, rates of emergency department visits for adolescent self-harm were 7% higher in 2020 than in 2019 (Ougrin et al., 2021).

Findings from research on suicidal ideation and behavior are mixed. Some studies suggest that suicide deaths may be decreasing (Isumi et al., 2020; Pirkis et al., 2021). In contrast, other studies of psychiatric hospital records document significantly elevated rates of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts in 2020 as compared to 2019 (Hill et al., 2020), with COVID-19 stress cited frequently as a source of suicidal feelings (Thompson et al., 2021).

Explaining increased risk.

Data is emerging about specific vulnerability factors that may explain increased symptoms. Online learning challenges, parent conflict, and pre-pandemic emotion regulation difficulties have been linked with increases in adolescents’ internalizing symptoms and inattention during the pandemic (Breaux et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021). Findings from studies using ecological momentary assessments (EMA), which provide data on adolescents’ behaviors and emotions in real-time, show that social distancing is related to less physical activity, happiness, and overall well-being during the pandemic than pre-pandemic (Munasinghe et al., 2020). Additionally, in an EMA study of adults and adolescents previously hospitalized for suicidal thinking or behaviors, increased feelings of isolation were more strongly associated with suicidal thinking during the pandemic than before (Fortgang et al., 2021).

Research is needed to uncover additional risk factors that explain pandemic impacts on adolescent mental health. One understudied variable is COVID-19-related health anxiety, worries about the self /others experiencing health problems from infection. Adolescents with high health anxiety may feel helpless to control their situation, leading to increased depression or suicidal thinking. Increased NSSI may emerge as a coping mechanism (however maladaptive) to manage worry about infection and its consequences. Initial data suggests that youths’ COVID-19 health anxiety may be linked with elevated depressive symptoms (Marques de Miranda et al., 2020), but associations of COVID-19 health anxiety with NSSI and suicidality are understudied.

In contrast to health anxiety, pandemic loneliness has received more empirical attention. Loneliness caused by the sudden loss of in-person interaction may predict increased depressive symptoms and suicidal thinking due to reduced social connectedness, which is especially salient for adolescents (Glenn et al., 2021; Ladd & Ettekal, 2013). Like health anxiety, loneliness may trigger increased use of maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as NSSI (Giletta et al., 2012). New work suggests COVID-19-related loneliness is associated with increased depressive symptoms (Alt et al., 2021; Esposito et al., 2021) and may be a significant trigger for self-destructive behavior (Carosella et al., 2021; Hawton et al., 2021); however, whether COVID-19-related loneliness predicts increased NSSI and suicide risk has not yet been directly tested.

Adolescents’ personal characteristics may reflect additional vulnerability. In line with pre-pandemic research (e.g., Ge et al., 2001), most pandemic studies evidence greater challenges for females regarding internalizing and self-destructive behavior (Hawton et al., 2021; Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021; Marques de Miranda et al., 2020; Kapetanovic et al., 2021). Although mid-adolescence typically is a time of increased incidence of psychopathology, studies are mixed regarding age differences in pandemic symptoms (Cost et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Equivocal evidence also exists regarding the mental health of youth with minoritized identities (e.g., gender, ethnic, racial, and sexual minority youth). Consistent with theories of minority stress (Meyer, 2015), some studies document greater pandemic distress for youth with minoritized identities (e.g., Scott et al., 2020); others suggest benefits of lockdowns for these youth (e.g., Penner et al., 2020).

The Current Study

The current study is well positioned to clarify the effects of COVID-19 health anxiety and loneliness on adolescents’ depressive symptoms, NSSI, and suicide risk. In a sample of middle and high school adolescents drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study, we assessed pre-COVID-19 depressive symptoms, NSSI frequency, and suicide risk (late January/early February 2020), real-time experience of COVID-19 health anxiety and loneliness during the pandemic’s early stages using EMA (March 2020), and subsequent levels of depressive symptoms, NSSI frequency, and suicide risk at the end of the academic year (June 2020). In addition to tracking symptom change from pre-pandemic levels, the current study extends past work by testing whether pandemic-related health anxiety and loneliness may help to explain symptom changes. Additionally, few studies present data collected in real time during the initial days of school closures, when adolescents were first exposed to significant restrictions. Higher levels of health anxiety and loneliness during initial lockdowns were expected to predict increased symptoms in June 2020, particularly for youth with higher pre-pandemic symptoms. Secondary analyses then tested whether significant effects differed as a function of gender identity, age, and/or sexual orientation. Stronger effects were expected for females, but given equivocal findings for the impacts of age and minority status, no hypotheses for these identity variables were proposed.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the first cohort of an ongoing project on rural adolescents’ socioemotional health. Of 1,248 eligible adolescents, consent forms were returned by 766 (61.4%). Of these, 572 had parent/guardian consent (74.7%), and 194 declined (25.3%). This sample included adolescents who contributed relevant EMA data (n = 362) in both middle (n = 107; M age = 12.61 years, SD = 0.93) and high school (n = 255; M age = 16.04 years, SD = 1.16) students. Adolescents reported gender identity (63.4% female, 33.0% male, 3.7% non-binary), sexual orientation (79.9% heterosexual, 20.1% sexual minority), and racial/ethnic identity (76.4% White, 2.1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 4.9% Asian, < 1% Black, < 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 6.0% more than one race; 3.5% Hispanic/Latinx; 9.8% not reported).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from two middle and two high schools in rural Maine. Parent/guardian consent and youth assent were obtained. Time 1 (pre-pandemic) survey measures were administered at school. Participants engaged with EMA (Time 2) during the first week of statewide school shutdowns in March 2020 and completed the June 2020 survey (Time 3) online, given ongoing closures and distancing recommendations. E-gift cards were provided to participants following each part of the project (Time 1: $10, Time 2: $20, Time 3: $15). See Supplemental Figure 1 for study timeline, overlaid with local / state COVID-19 restrictions.

Survey Measures

Demographic information.

Participants reported their date of birth, age, grade, gender identity, sexual orientation, racial identity, and ethnic identity.

Depressive symptoms.

Adolescents responded to the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), which measures the presence and severity of depressive symptoms experienced over the past week. Items are rated on a 0-3 scale: Rarely or none of the time (less than one day), Some or a little of the time (1-2 days), Occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3-4 days), Most or all of the time (5-7 days). Sum scores were calculated for each participant at Time 1 (α = .94) and Time 3 (α = .93).

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI).

Frequency of NSSI was assessed using a 7-item measure adapted from Prinstein et al. (2008). At Time 1, one item assessed the frequency with which participants engaged in any type of NSSI over the past 3 months1. The next four items assessed the frequency of engagement in specific forms of NSSI over the past 3 months (cutting, hitting, pulling hair, burning). Two additional (optional) items allowed participants to describe and rate the past 3-month frequency of other NSSI methods they may have used (e.g., “biting myself”, “stabbing”). The Time 3 NSSI frequency assessment was identical, except that participants rated NSSI frequency since the Time 1 assessment. Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale for frequency ranging from 0 (Never) to 5 (Once a day). Scores were the highest reported frequency of any type of NSSI at both Time 1 and Time 3.

Suicide risk.

Adolescents responded to the 4 items of the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001) which assess past suicidal behavior, frequency of suicidal ideation, communication to others about suicidal behavior, and likelihood of future suicide attempt. Sum scores are calculated as reliable and valid indicators of suicide risk, with higher scores reflecting higher risk. Instructions were adapted such that adolescents reported on their experiences over the past 3 months at Time 1 (α = .80) and since the Time 1 assessment at Time 3 (α = .78). A licensed psychologist monitored SBQ-R responses and assessed participants for imminent risk if responses exceeded predetermined risk thresholds. In these cases, parents were notified and clinical referrals and community supports were provided.

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

Interval-contingent EMA was conducted using the LifeData app on adolescents’ smartphones. Data collection occurred during the first week of statewide school shutdowns in March 2020 (Time 2). Three times a day (morning, afternoon, evening) for 7 days, the app prompted adolescents to rate their levels of COVID-19 loneliness and health anxiety on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Rarely/None of the Time) to 5 (Almost Always/All of the Time). EMA surveys were timed to not interfere with remote school hours, and each took 30-60 seconds to complete. Participants’ scores for loneliness and health anxiety were the mean of daily ratings across the 7-day period for the loneliness and health anxiety items, respectively. On average, adolescents contributed 17 of 21 EMA surveys (compliance rate = 81%)2.

Missing Data and Analytic Approach

Some youth were missing survey data at either Time 1 (n = 8) or Time 3 (n = 60). Little’s test indicated that these data were missing completely at random (MCAR), χ2(30) = 40.44, p = .10. Because imputing missing data is preferable to listwise deletion, missing data were imputed using an expectation maximization procedure in SPSS 28.0, and the full sample was retained for analyses. Results from analyses conducted with and without imputed data were identical. Paired samples t-tests examined changes in severity of depressive symptoms, NSSI frequency, and suicide risk scores from Time 1 to Time 3. t-tests also examined mean-level differences based on gender identity (female, male)3, grade group (middle school, high school), and sexual orientation (heterosexual, sexual minority) in each study variable.

Primary hypotheses regarding the impact of COVID-19 loneliness and health anxiety on depressive symptoms, NSSI frequency, and suicide risk were tested with multiple regression in SPSS 28.0, after ensuring that assumptions (multivariate normality, multicollinearity) were met. Time 3 symptoms were dependent variables in separate models. All predictors were centered at the sample mean. Main effects of Time 1 symptoms, health anxiety, and loneliness were entered on Step 1, and 2-way interactions were added on Step 2. Significant interactions were probed using simple slope analyses where Time 1 symptom scores were re-centered at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels. Secondary analyses examined whether gender identity, grade group, or sexual orientation further moderated significant effects from primary models by adding the main effect of the group variable and relevant interactions with symptoms, health anxiety, and loneliness.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. Depressive symptoms, health anxiety, and loneliness were normally distributed, whereas NSSI frequency and suicide risk were skewed as expected, with fewer adolescents endorsing high levels. Depressive symptoms were moderate, with 26.5% of adolescents exceeding clinical cutoffs (e.g., score of 24; Roberts et al., 1991)4. Similar to past community studies (Muehlenkamp et al., 2012), 12.1% and 11.8% reported NSSI at Time 1 and Time 3, respectively. Average SBQ-R risk scores were comparable to past adolescent studies (Osman et al., 2001), and 15.3% and 11.9% of adolescents met or exceeded the suicide risk cut score of 7 at Times 1 and 3. Mean levels of loneliness and health anxiety were moderate (near 3 on a 1-5 scale). Depressive symptoms, NSSI, and suicide risk was significantly and positively correlated within and across time. Each also was positively correlated with loneliness and health anxiety, with the exception of a nonsignificant association between Time 1 NSSI and health anxiety. Depressive symptoms [t(361) = 0.01, p = .99, d < 0.01] and NSSI frequency [t(361) = 0.98, p = .33, d = 0.05] did not differ from Time 1 to Time 3. Suicide risk [t(361) = 2.42, p < .05, d = 0.13] did decrease, on average, from Time 1 to Time 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

|

M(SD), Median (Observed Range) |

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 CESD | 16.58 (12.19), 13 (0-59) | - | |||||||

| 2. T3 CESD | 16.58 (11.66), 14 (0-52) | .79*** | - | ||||||

| 3. T1 NSSI | 0.20 (0.66), 0 (0-5) | .38*** | .38*** | - | |||||

| 4. T3 NSSI | 0.17 (0.61), 0 (0-5) | .32*** | .39*** | .71*** | - | ||||

| 5. T1 SBQ | 4.32 (2.34), 3 (2-17) | .64*** | .54*** | .37*** | .31*** | - | |||

| 6. T3 SBQ | 4.18 (2.09), 3 (2-16) | .61*** | .56*** | .33*** | .29*** | .88*** | - | ||

| 7. T2 Hanxiety | 2.40 (0.95), 4 (1-5) | .24*** | .29*** | .06 | .14* | .19*** | .20*** | - | |

| 8. T2 Lonely | 2.82 (1.16), 4 (1-5) | .48*** | .60*** | .20*** | .19** | .38*** | .38*** | .34*** | - |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. T1 = Time 1 (pre-pandemic survey; late January/early February 2020). T2 = Time 2 (EMA; March 2020). T3 = Time 3 (June 2020 survey). CES-D = depressive symptoms score. NSSI = frequency of NSSI behavior. SBQ = suicide risk score. HAnxiety = health anxiety. Lonely = loneliness.

Mean-Level Gender Identity, Grade Group, and Sexual Orientation Differences

Mean-level group differences are reported in Table 2. Female adolescents reported significantly higher Time 1 and Time 3 depressive symptoms, Time 1 and Time 3 suicide risk scores, and COVID-19 health anxiety and loneliness than did males. There were no gender differences observed for NSSI frequency at Time 1 or Time 3. High school adolescents reported significantly higher levels of Time 3 NSSI frequency, health anxiety, and loneliness than did middle school adolescents. Adolescents endorsing a sexual minority orientation reported significantly higher levels of all study variables than did heterosexual adolescents.

Table 2.

Mean-Level Group Differences by Gender Identity, Grade Group, and Sexual Orientation

| Gender Identity | Grade Group | Sexual Orientation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | ||||||||

| t / d | Female | Male | Non- Binary |

t / d | Middle School |

High School |

t / d | Hetero | Sexual Minority |

|

| 1. T1 CESD |

t(340) = 6.43**** d = 0.73 |

18.65 (12.08) | 10.55 (8.73) | 32.15 (15.46) |

t(360) = −1.67 d = 0.19 |

14.93 (12.25) | 17.27 (12.12) |

t(352) = −6.62*** d = 0.81 |

14.44 (10.82) | 24.59 (14.11) |

| 2. T3 CESD |

t(340) = 5.87**** d = 0.67 |

18.42 (11.87) | 11.24 (8.17) | 28.54 (13.51) |

t(360) = −2.02 d = 0.23 |

14.68 (11.48) | 17.38 (11.66) |

t(352) = −5.58*** d = 0.70 |

14.78 (10.74) | 23.02 (12.57) |

| 3. T1 NSSI |

t(340) = 1.05 d = 0.12 |

0.20 (0.70) | 0.13 (0.41) | 0.85 (1.34) |

t(360) = −1.56 d = 0.20 |

0.12 (0.46) | 0.24 (0.72) |

t(352) = −4.06*** d = 0.45 |

0.13 (0.54) | 0.48 (0.97) |

| 4. T3 NSSI |

t(340) = 1.24 d = 0.14 |

0.20 (0.65) | 0.11 (0.46) | 0.46 (1.13) |

t(360) = −1.99* d = 0.26 |

0.08 (0.25) | 0.22 (0.71) |

t(352) = −3.80*** d = 0.42 |

0.11 (0.50) | 0.42 (0.92) |

| 5. T1 SBQ |

t(340) = 3.03** d = 0.35 |

4.47 (2.43) | 3.71 (1.67) | 7.00 (3.79) |

t(360) = −1.15 d = 0.14 |

4.10 (2.10) | 4.41 (2.43) |

t(352) = −7.63*** d = 0.86 |

3.87 (1.86) | 6.08 (3.12) |

| 6. T3 SBQ |

t(340) = 2.62** d = 0.30 |

4.28 (2.12) | 3.70 (1.56) | 6.54 (3.76) |

t(360) = −0.98 d = 0.12 |

4.01 (1.93) | 4.25 (2.15) |

t(352) = −8.35*** d = 0.93 |

3.75 (1.63) | 5.88 (2.81) |

| 7. T2 HAnxiety |

t(340) = 3.56*** d = 0.38 |

2.52 (0.90) | 2.16 (0.97) | 2.31 (0.93) |

t(360) = −2.87** d = 0.32 |

2.18 (1.10) | 2.50 (0.87) |

t(352) = −2.40* d = 0.32 |

2.34 (0.95) | 2.63 (0.87) |

| 8. T2 Lonely |

t(340) = 5.31**** d = 0.61 |

2.99 (1.08) | 2.33 (1.12) | 3.78 (1.15) |

t(360) = −4.89*** d = 0.55 |

2.37 (1.22) | 3.01 (1.09) |

t(352) = −4.77*** d = 0.67 |

2.66 (1.15) | 3.37 (0.96) |

Notes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001. T1 = Time 1 (pre-pandemic survey, late January/early February 2020). T2 = Time 2 (EMA, March 2020). T3 = Time 3 June 2020 survey). CESD = depressive symptoms score. NSSI = frequency of NSSI behavior. SBQ = suicide risk score. HAnxiety = health anxiety. Lonely = loneliness. Hetero = heterosexual. t tests involving gender identity compare female-identifying and male-identifying participants, as the number of participants endorsing a non-binary/gender minority identity were too few (n = 13) to incorporate statistical comparisons with this group.

Effects of COVID-19-Distress on Depressive Symptoms, NSSI Frequency, and Suicide Risk

First, we evaluated the effect of COVID-19-related health anxiety and loneliness on the severity of depressive symptoms over time (see Table 3). The 2-way interaction between Time 1 depressive symptoms and loneliness significantly predicted Time 3 depressive symptoms. Simple slope analyses indicated that loneliness predicted increased depressive symptoms for all adolescents, but the effect was stronger for adolescents with higher levels of Time 1 depressive symptoms [b = 3.59 (2.67, 4.52), p < .0001] than for adolescents with lower levels of Time 1 depressive symptoms [b = 2.05 (1.11, 2.98), p < .0001] (see Figure 1). This effect was not further moderated by gender identity, grade group, or sexual orientation (see Supplemental Tables 1-3).

Table 3.

Summary of Primary Multiple Regression Analyses

| IV | DV = T3 Depressive Symptoms | DV = T3 NSSI Frequency | DV = T3 Suicide Risk | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (95% CI) | SE | ηp2 | b (95% CI) | SE | ηp2 | b (95% CI) | SE | ηp2 | |

| Step 1: | ΔR2 = .68, ΔF(3, 358) = 256.31**** | ΔR2 = .51, ΔF(3, 358) = 124.15**** | ΔR2 = .78, ΔF(3, 358) = 427.27**** | ||||||

| T1 Sx | .61(.55, .68) | .03 | .31 | .65(.58, .72) | .04 | .47 | .77(.73, .82) | .02 | .64 |

| HAnxiety | .52(−.25, 1.23) | .39 | .00 | .05(.00, .10) | .03 | .01 | .05(−.07, .16) | .06 | .00 |

| Lonely | 2.79(2.10, 3.49) | .35 | .06 | .01(−.03, .05) | .02 | .00 | .07(−.03, .17) | .05 | .00 |

| Total R2 | .68 | .51 | .78 | ||||||

| Step 2: | ΔR2 = .01, ΔF(3, 355) = 4.47** | ΔR2 = .06, ΔF(3, 355) = 15.05**** | ΔR2 = .01, ΔF(3, 355) = 3.88** | ||||||

| T1 Sx X HAnxiety | .06(−.00, .13) | .04 | .00 | .15(.09, .21) | .03 | .03 | −.02(−.08, .01) | .02 | .00 |

| T1 Sx X Lonely | .06(.01, .12) | .03 | .01 | −.14(−.20, −.07) | .03 | .02 | .08(.03, .13) | .02 | .01 |

| HAnxiety X Lonely | −.45(−1.11, .21) | .34 | .00 | .01(−.03, .04) | .02 | .00 | −.01(−.10, .09) | .05 | .00 |

| Total R2 | .69 | .57 | .79 | ||||||

Notes. For F tests:

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001. An FDR correction was applied for tests conducted in primary analyses; the adjusted p-value for significance is p < .016. Effects meeting this corrected threshold are bolded. T1 = Time 1 (pre-pandemic survey, late January/early February 2020). T3 = Time 3 (June 2020 survey). Sx = symptoms. HAnxiety = health anxiety. Lonely = loneliness.

Figure 1. Effects of loneliness on Time 3 depressive symptoms at low (−1SD) / high (+1SD) levels of Time 1 depressive symptoms.

Note. ****p < .0001.

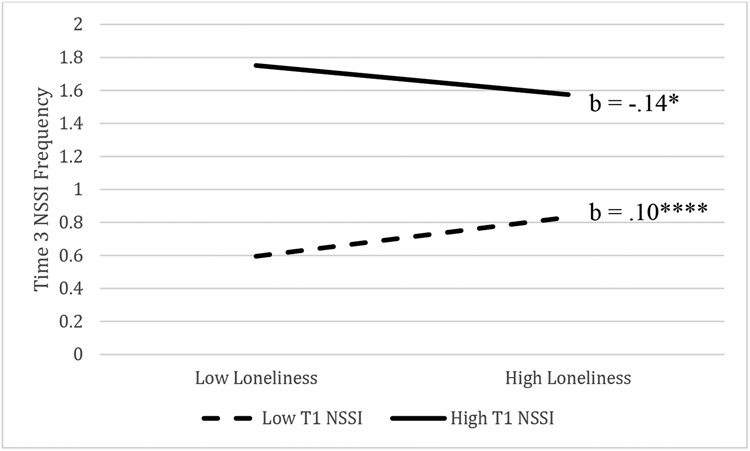

Analyses next tested whether health anxiety and loneliness predicted change in NSSI frequency (see Table 3). The 2-way interaction between Time 1 NSSI frequency and health anxiety and the 2-way interaction between Time 1 NSSI frequency and loneliness were significant. Higher health anxiety predicted higher Time 3 NSSI frequency for adolescents who reported higher Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = 0.14 (.08, .20), p < .0001] but not for adolescents who reported lower Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = −0.06 (−.13, .01), p = .08] (see Figure 2A). In secondary analyses, this effect was further moderated by gender identity (see Supplemental Tables 1-3). Greater health anxiety predicted higher Time 3 NSSI frequency for females with higher Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = 0.15 (.08, .23), p < .0001] and for males with lower Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = .32 (.18, .46), p < .0001]. However, higher health anxiety predicted lower Time 3 NSSI frequency for males with higher Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = −.32 (−.48, −.15), p < .0001] and females [b = −.11 (−.18, −.03), p < .001] with lower Time 1 NSSI frequency.

Figure 2.

Panel A Effects of health anxiety on Time 3 NSSI frequency at low (−1SD) / high (+1SD) levels of Time 1 NSSI frequency

Regarding the interaction of Time 1 NSSI and loneliness, higher loneliness predicted higher Time 3 NSSI frequency for adolescents with lower Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = 0.10 (.05, .16), p < .0001] and lower Time 3 NSSI frequency for adolescents with higher Time 1 NSSI frequency [b = −0.08 (−.14, −.02), p = .016). See Figure 2B. This effect was not further moderated by gender, grade group, or sexual orientation (see Supplemental Tables 1-3).

Figure 2.

Panel B Effects of loneliness on Time 3 NSSI frequency at low (−1SD) / high (+1SD) levels of Time 1 NSSI frequency

Notes. *p = .016. ****p < .0001.

Finally, analyses tested whether health anxiety and loneliness impacted suicide risk from Time 1 to Time 3 (see Table 3). The 2-way interaction between Time 1 suicide risk and loneliness was significant. Higher loneliness predicted higher Time 3 suicide risk for adolescents with higher Time 1 suicide risk [b = 0.28 (.12, .43), p < .0001] but not for adolescents with lower Time 1 suicide risk [b = −0.10 (−.23, .04), p = .17]. See Figure 3. This effect was not further moderated by gender identity, grade group, or sexual orientation (see Supplemental Tables 1-3).

Figure 3. Effects of loneliness on Time 3 suicide risk at low (−1SD) / high (+1SD) levels of Time 1 suicide risk.

Note. ****p < .0001.

Discussion

The current study sought to clarify whether and under what conditions adolescents’ depressive symptoms, NSSI frequency, and suicide risk changed from pre-pandemic to June 2020. One key finding is that loneliness was a predictor of higher depressive symptoms for adolescents with both lower and higher levels of pre-pandemic depressive symptoms, although the effect was strongest for adolescents with existing struggles. This result is consistent with studies demonstrating that loneliness and reduced social support from friends are linked to higher depressive symptoms (Alt et al., 2021; Rogers & Ockey, 2020) and with work documenting greater increases in depressive symptoms for adolescents in areas with lower COVID-19 case rates and higher restrictions (Barendse et al., 2021), such as Maine during this period of the pandemic. Preliminarily, these results suggest that loneliness may be a key intervention target for reducing the prevalence of adolescents’ COVID-19-related depressive symptoms.

COVID-19 loneliness also played a significant role in explaining changes in NSSI frequency and suicide risk, depending on pre-pandemic symptom levels. Loneliness predicted more frequent NSSI for adolescents reporting less frequent pre-pandemic NSSI. This concerning finding suggests that isolation and reduced social support from peers during school closures may have facilitated the emergence of NSSI as a coping strategy for some adolescents navigating this challenging time. Regarding suicidality, loneliness predicted higher suicide risk for youth already at higher pre-pandemic risk. Consistent with interpersonal theories of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010), social disconnection during COVID-19 may be particularly potent for those already struggling with suicidal thinking and behavior. Fortunately, adolescents without elevated pre-pandemic risk did not experience increased risk as a function of COVID-19 distress.

Interestingly, elevated loneliness predicted decreased NSSI for adolescents who self-injured more before the pandemic. Additional research is needed to replicate this unexpected finding. Some studies suggest that family functioning may have improved for some youth during stay-at-home orders (Rogers & Ockey, 2020) and that this may have benefits for mental health (Cao et al., 2021). Adolescents with existing NSSI may have benefited from being at home due to increased family monitoring and/or less in-person, school stress (e.g., peer conflict).

Health anxiety, on the other hand, predicted increased NSSI frequency for those adolescents with more frequent, pre-pandemic NSSI. Secondary analyses suggested this finding may be clarified by considering gender identity. Greater health anxiety predicted higher NSSI for girls who frequently self-injured pre-pandemic. Yet an opposite picture emerged for self-injuring boys, whose health anxiety predicted lower NSSI frequency during lockdown. It is unclear why this was the case; however there are some clues that may inform future research. Girls report more worry about the virus, whereas boys report being more confident the virus will resolve itself and that they are experiencing greater improvements in family stress during lockdown (Kapetanovic et al., 2021). Thus, girls already using NSSI to cope may have continued to do so in response to greater stress about their health, whereas boys’ health anxiety may be less severe and their stress better mitigated by stay-at-home measures. This potentiality should be tested in future studies of self-injuring adolescents with a variety of gender identities.

Concerningly, greater health anxiety predicted higher NSSI for boys with lower pre-pandemic levels of self-injury. This finding is suggestive of NSSI as an emergent coping tool for stress, but, again, more research is needed. One possibility is that some stress-relieving strategies more typical of adolescent males (e.g., organized activities with friends; Rose & Rudolph, 2006) were unavailable due to widespread shutdowns and that some males faced with high health anxiety turned to self-injury to cope. Of course, vulnerability to NSSI extends beyond the mere experience of stress (Nock, 2009), and future studies focused on the particular vulnerabilities of health-anxious males during the pandemic may shed additional light on this finding.

Null findings regarding grade group and sexual orientation differences are potentially noteworthy and may underscore existing equivocal findings regarding impacts of the pandemic for youth of different ages and minoritized identities. Regarding grade group, although rates of depression, self-injury, and suicide typically are higher among older adolescents (Barrocas et al., 2012; Pelkonen & Marttunen, 2003; Thapar et al., 2012), grade group differences were not observed and require replication before assuming that mental health impacts of the pandemic are similar for these groups. The lack of observed differences between heterosexual and non-heterosexual adolescents also require replication, and future research should carefully examine the heterogeneous group of sexual minority adolescents in terms of potential benefits (e.g., fewer in-person, school-based stressors; Mitchell et al., 2021) and challenges (e.g., increased time at home; Salerno et al., 2021) that sexual minority adolescents may encounter.

The current study has several strengths. First, results build on past work identifying specific factors that help explain increased psychopathology in community samples. Although health anxiety and loneliness were identified as correlates of symptoms, no research had tested whether these indices of COVID-19 distress moderated increases in symptoms over time. Second, few studies employed EMA during this stage of the pandemic, which allowed for in-the-moment assessment without reliance on retrospective reports. EMA was well-suited during the pandemic when technology use was high and in-person assessments were not possible, and the timing of our planned EMA in the context of unexpected school closures was fortuitous to capture these early days of isolation. The current study also considered COVID-19’s impact on specific populations and adolescents with existing elevated risk. Relatively few studies have considered the roles of gender, age, or sexual orientation in the association between COVID-19 distress and psychopathology over time. Finally, results indicate a surprisingly significant short-term impact of COVID-19 restrictions, suggesting that how adolescents felt in the first days of isolation is important in understanding their adjustment 6 months later. These findings may be applicable to adolescents’ mental health more broadly or for other universally stressful experiences. It may be that other, widely impactful stressors have a similarly consequential impact, although future studies must address how long lasting and specific these effects can be.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This research also has important limitations that point to the need for future research. Although the sudden onset of COVID-19 in the context of this ongoing project presented a unique opportunity, available data were limited in that the larger study was not initially designed to answer questions about a pandemic, and hypotheses were not preregistered. Conclusions are tied to the data available from the existing design, and our findings raise new questions. For example, what are the longer-term impacts of COVID-19 and related restrictions on adolescent well-being, and are the initial effects we observed sustained over time? The pandemic, our response to it, and recommendations for daily living have changed with the evolution of our knowledge and the virus itself. On the one hand, adolescent adjustment may have improved due to increased in-person learning exposure to peers. Alternately, stress from the pandemic and its reverberations persists. Mental health impacts catalyzed by the onset of COVID-19 and associated public health measures may be maintained for adolescents due to lack of treatment and may be especially intractable for youth who have directly experienced grief and loss, complicated illness, significant financial impacts, or other resource deprivation.

Relatedly, current data cannot speak to the longer-term impact of COVID-19 health anxiety and loneliness. As restrictions ease, time goes on, and the novelty of the pandemic fades, adolescents may experience changes in the levels and forms of their pandemic distress (e.g., less anxiety about infection, more anxiety about how long this will last) and/or may be better able to adjust to the experience of the pandemic in general. One could imagine that continued exposure to pandemic stressors may facilitate a habituation of sorts. Future research should examine whether and how adolescents are coping with long term COVID-19 stress and/or whether some adolescents are developing symptoms of chronic or complex trauma.

Aspects of measurement in the current study limit the conclusions that can be drawn. First, symptoms were not assessed at Time 2, prohibiting causal inferences and raising new questions about how these processes unfold over time. Future studies assessing symptoms at all possible time points and in conjunction with vulnerability factors of interest would clarify that symptom change is not better attributable to other variables (e.g., worsening cognitive biases in the context of existing depressive symptoms). Future studies also should assess symptoms using identical timeframes (i.e., at Time 1, depressive symptoms were assessed over the past week and NSSI frequency/suicide risk was assessed over past 3 months). Also, assessing lifetime (and not just recent) histories of NSSI and suicide risk would have provided more specific information about pandemic-related changes in these symptoms. Findings only speak to changes in adolescents’ symptoms from just before the pandemic to 6 months later and cannot specifically speak to changes in adolescents with a lifetime history of NSSI who were not self-injuring just prior to the pandemic. Further, use of the SBQ-R in the current study was intended, in part, to evaluate the utility of the measure for capturing risk at shorter intervals (3, 6 months), as use for this purpose has not been widely validated. Additional validation of the SBQ-R measure over similar intervals would enhance confidence in these findings. Finally, there are many ways to assess the constructs of interest (e.g., comprehensive measures of loneliness, number of methods used in NSSI, variability scores or worst-point EMA ratings), and future research expanding measurement in this way will add texture to these results.

Generalization of these findings outside of a rural, largely White, New England population also is limited. During this stage of the pandemic, case counts in Maine were relatively low, and the State’s response to implementing COVID-19 safety restrictions was quick and comprehensive. It is not known whether findings would be similar if data were drawn from later in the pandemic (i.e., higher cases, fewer restrictions) or if data are comparable to other rural areas with different sociopolitical climates. Additionally, it is not known whether and how the climates and resources of the schools involved may have contributed to the findings.

Implications for Caregivers, Educators, and Clinicians

The experience of the pandemic and emerging data on its quick impacts, at least over the short term, clearly emphasize the need to consider and address adolescent mental health, along with the physical health implications of COVID-19. At a time when adolescents were particularly vulnerable, they also may have had less access to consistent, quality care, as school closures and reduced special services may have cut some adolescents off from essential resources (Martin & Sorensen, 2020). What is more, results from the current study suggest that youth already experiencing mental health challenges and risks may have fared especially poorly during the pandemic and that other groups not previously identified as being at risk, may face new mental health challenges.

More than ever, telehealth is essential to increasing access to clinical services (Torous et al., 2020). Results underscore the necessity to meet youths’ mental health care needs now, given that the pandemic continues to complicate the provision of in-person therapy services. Further, in order to develop effective treatment options for youth suffering from the psychological impacts of the pandemic, we need to identify and target the specific processes supporting adolescents’ emotional adjustment. The current study highlights two potential processes, loneliness and health anxiety, that may be beneficial clinical targets. Both increasing time spent in quality activities with peers where possible but also focusing interventions to reduce adolescents’ attention to negative cognitions in and around loneliness and health anxiety could be fruitful avenues. Finally, although future studies must address this potential empirically, findings may inform supportive prevention and intervention efforts that target stressor-specific processes impeding well-being for those who may face widespread environmental stressors (e.g., natural disasters) in the future.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Data collection and writing were supported by NIMH grant R15 MH116341 awarded to Rebecca Schwartz-Mette. The writing of this article was further supported by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32-HD07376) through the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to Natasha Duell and an American Foundation for Suicide Prevention grant (PDF-0-095-19) awarded to Hannah Lawrence.

Footnotes

Ethics: The study was reviewed by the University of Maine’s Institutional Review Board (approval #2017-05-18)

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

In the larger study, adolescents were assessed at 3-month intervals prior to the pandemic. The late January/early February assessment of NSSI frequency was used as Time 1, as it was most proximal to the onset of the pandemic.

COVID-19 restrictions precluded loaning smartphones to youth without personal devices (n = 56) as planned. These youth were prompted to complete surveys online 3x/day using a school-issued laptop. Online survey items were identical to those in the app. Representative analyses indicated no significant differences for any variable as a function of EMA method, and analyses conducted with and without youth who used the online survey revealed identical results. All cases were thus retained for analyses.

The small number of youth identifying as gender minority/non-binary (n = 13) precluded planned statistical comparisons with female- and male-identifying youth. Descriptive data for these youth are presented in Table 2.

The adult cut score of 16 has been used with adolescents (Roberts et al., 1990), yet this can result in identifying half of adolescents as having elevated symptoms (Rushton et al., 2002). Higher adolescent cut scores (e.g., 24) have been recommended (Roberts et al., 1991), and observed means (Table 1) provide support for this recommendation.

References

- Agid O, Kohn Y, & Lerer B (2000). Environmental stress and psychiatric illness. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 54(3), 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt P, Reim J, & Walper J (2021). Fall from grace: Increased loneliness and depressiveness among extraverted youth during the German COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 678–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He J-P, Burstein M, & Merikangas KR (2015). Major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendse M, Flannery JE, Cavanagh C, Aristizabal M, Becker SP, Berger E, … Pfeifer JH (2021, February 3). Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: A collaborative of 12 samples from 3 countries. Advance online preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrocas AL, Hankin BL, Young JF, & Abela JRZ (2012). Rates of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth: Age, sex, and behavioral methods in a community sample. Pediatrics, 130(1), 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA (1995). Risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior: Mental and substance abuse disorders, family environmental factors, and life stress. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 25, 52–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, Buchen N, Langberg JM, & Becker SP (2020). Prospective impact of covid-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(9), 1132–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Huang L, Si T, Wang NF, Qu M, & Yang Zhang X (2021). The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosella KA, Wiglesworth A, Silamongko T, Tavares N, Falke CA, Fiecas MB, …Klimes-Dougan B (2021). Non-suicidal self-injury in the context of COVID-19: The importance of psychosocial factors for female adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cauberghe V, Van Wesenbeeck I, De Jans S, Hudders L, & Ponnet K (2020). How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (2002). A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP,…& Thigpen JC (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S,…& Korczak (2021). Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, & Forbes LM (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52(3), 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito SE, Giannitto N, Squarcia A, Neglia C, Argentiero A, Minichetti P, …& Principi N (2021). Development of psychological problems among adolescents during school closures because of the COVID-19 lockdown phase in Italy: A cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 8. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortgang RG, Wang SB, Millner AJ, Reid-Russell A, Beukenhorst AL, Kleiman EM, …& Nock MK (2021). Increase in suicidal thinking during COVID-19. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(3), 482–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, & Elder GH Jr. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 404–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giletta M, Scholte RHJ, Engels RCME, Ciairano S, & Prinstein MJ (2012). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: A cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Research, 197(1–2), 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Kandlur R, Esposito EC, & Liu RT (2021). Thwarted belongingness mediates interpersonal stress and suicidal thoughts: An intensive longitudinal study with high-risk adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL (2003). Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Lascelles K, Brand F, Casey D, Bale L, Ness J,…& Waters K (2021). Self-harm and the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of factors contributing to self-harm during lockdown restrictions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137, 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, & Williams L (2020). Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics, 147(3). Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Colasante, & Lougheed JP (2021). Adolescent and maternal anxiety symptoms decreased but depressive symptoms increased before to during COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 517–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isumi A, Doi S, Yamaoka Y, Takahashi K, & Fujiwara T (2020). Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(2). Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N, … & Brown M (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR supplements, 69(1), 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Gurdal S, Ander B, & Sorbring E (2021). Reported changes in adolescent psychosocial functioning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Adolescents, 1(1), 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, & Ettekal I (2013). Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: Normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1269–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magis-Weinberg L, Gys CL, Berger EL, Domoff SE, & Dahl RE (2021). Positive and negative online experiences and loneliness in Peruvian adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 717–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, & Fardouly J (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques de Miranda D, da Silva Athanasio B, Sena Oliveira AC, & Simoes-e-Silva AC (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EG, & Sorensen LC (2020). Protecting the health of vulnerable children and adolescents during COVID-19–related K-12 school closures in the US. JAMA Health Forum, 1(6), e200724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurka R, Wynne-Edwards KE, & Harkness KL (2016). Stressful life events prior to depression onset and the cortisol response to stress in youth with first onset versus recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(6), 1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minority persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Banyard V, Goodman KL, & Jones LM (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceptions of health and well-being among sexual and gender minority adolescents and emerging adults. LGBT Health. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, & Plener PL (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, Conroy E, Jani H, Marjanovic S, & Page A (2020). The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KM, Gordon AR, John SA, Stout CD, & Macapagal K (2020). Physical sex is over for now: Impact of COVID-19 on the well-being and sexual health of adolescent sexual minority males in the U.S. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(6), 756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D, Wong BH-C, Vaezinejad M, Plener PL, Mehdi T, Romaniuk L,…& Landau S (2021). Pandemic-related emergency psychiatric presentations for self-harm of children and adolescents in 10 countries (PREP-kids): A retrospective international cohort study. European Child &Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, & Barrios FX (2001). The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 8(4), 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen M, & Marttunen M (2003). Child and adolescent suicide: Epidemiology, risk factors, and approaches to prevention. Pediatric Drugs, 5(4), 243–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner F, Ortiz JH, & Sharp C (2020). Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority Hispanic/Latinx US sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, Delpozo-Banos M, Arya V, Aguilar PA, …& Spittal MJ (2021). Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Interrupted time series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry, 8(7), 579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CSL, & Spirito A (2008). Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, & Madigan S (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS, (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychologial Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM, & Hops H (1990). Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2(2), 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, & Seely JR (1991). Screening for adolescent depression: A comparison of depression scales. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(1), 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA, & Ockey S (2020). Adolescents' perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: Results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, & Miconi D (2020). Protecting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A challenging engagement and learning process. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1203–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton J, Forcier M, & Schectman RM (2002). Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno JP, Doan L, Sayer LC, Drotning KJ, Rinderknecht RG, & Fish JN (2021). Changes in mental health and well-being are associated with living arrangements with parents during COVID-19 among sexual minority young persons in the U.S. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette RA, Shankman J, Dueweke AR, Borowski S, & Rose AJ (2020). Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(8), 664–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SR, Rivera KM, Rushing E, Manczak EM, Rozek CS, & Doom JR (2020). "I hate this": A qualitative analysis of adolescents' self-reported challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(2), 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Ribeaud D, Murray AL, Hepp U, Eisner M, & Shanahan L (2021). Self-injury and domestic violence in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Trajectories, precursors, and correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 560–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, & Thapar AK (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torous J, Jän Myrick K, Rauseo-Ricupero N, & Firth J (2020). Digital mental health and COVID-19: Using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Mental Health, 7(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon AWG, Creemers HE, Vogelaar S, Miers AC, Saab N, Westenberg PM, & Asscher JJ (2021). Prepandemic risk factors of COVID-19-related concerns in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 531–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite S, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson MF, Bacigalupe G, Daneshpour M, Han W, & Parra-Cardona R (2020). COVID- 19 Interconnectedness: Health inequity, the climate crisis, and collective trauma. Family Process, 59(3), 832–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S-J, Zhang L-G, Wang L-L, Guo Z-C, Wang J-Q, Chen J-C, Lu M, Chen X, & Chen J-X (2020). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.