Abstract

Productivity of crop plants are enormously affected by biotic and abiotic stresses. The co-occurrence of several abiotic stresses may lead to death of crop plants. Hence, it is the responsibility of plant scientists to develop crop plants equipped with multistress tolerance pathways. A subgroup of zinc finger transcription factor family, known as B-box (BBX) proteins, play a key role in light and hormonal regulation pathways. In addition, BBX proteins act as key regulatory proteins in many abiotic stress regulatory pathways, including Ultraviolet-B (UV-B), salinity, drought, heat and cold, and heavy metal stresses. Most of the BBX proteins identified in Arabidopsis and rice respond to more than one abiotic stress. Considering the requirement of improving rice for multistress tolerance, this review discusses functionally characterized Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins in the development of abiotic stress responses. Furthermore, it highlights the participation of BBX proteins in multistress regulation and crop improvement through genetic engineering.

Keywords: Abiotic stress, B-box proteins, Multistress tolerance, Arabidopsis, Rice

Introduction

Biotic and abiotic stresses in plants are due to a wide array of environmental stimuli that severely affect crop productivity. When plants exceed their limit of tolerance, they experience stress and initiate the stress-responsive pathways (Chen et al. 2006a; Guo et al. 2016). Abiotic stresses including light, heat, cold, drought, high salinity, oxidative and heavy metal stresses cause significant yield loss in world’s leading food crops: rice, barley, corn, etc. (He et al. 2018a). Functional characterization of abiotic stress-responsive genes in plants have a greater impact on developing abiotic stress tolerance in susceptible crop plants. A subgroup of zinc finger transcription factor family; plant B-box (BBX) proteins are known to respond to biotic (Taki et al. 2005; Libault et al. 2007) and abiotic stresses (Wang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2016; Shalmani et al. 2019). BBX proteins have been well characterized in Arabidopsis and to a certain extent in rice.

The BBX genes are highly conserved across the plant species (Huang et al. 2012; Crocco and Botto 2013; Khanna et al. 2009). In addition, the B-box domains are conserved in BBX proteins (Huang et al. 2012) and it contains five conserved cysteine (C) residues, histidine (H) and aspartic acid (D) amino acids bound to zinc ions (Crocco and Botto 2013). B-box domains participate in DNA-binding or protein–protein interactions (Huang et al. 2012; Datta et al. 2007; Qi et al. 2012). Certain BBX members contain an additional CONSTANS, CO-like, and TOC1 (CCT) domain (Huang et al. 2012; Khanna et al. 2009). In animals, B-box domain is found in Tripartite Motif (TRIM) proteins that contain an N-terminal Really Interesting New Gene (RING) domain followed by one or two B-box domains. TRIM proteins play an essential role in cell ubiquitination, protein transport and transcription regulation (Meroni and Diez-roux 2005; Massiah 2019).

The Arabidopsis BBX family consisting of 32 BBX proteins that are extensively studied (Gangappa and Botto 2014; Yadav et al. 2020a). Subsequently, many BBX proteins have been identified from crop plants, 30 from rice (Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012), 29 from tomato (Chu et al. 2016), 24 from grape (Wei et al. 2020), 30 from potato (Talar et al. 2017), and 24 from sorghum (Shalmani et al. 2019) and some of them have been functionally characterized. BBX proteins function in abiotic stress regulation pathways (Wang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2016; Shalmani et al. 2019). Additionally, plant BBX proteins play a significant function in regulating plant growth and developmental processes such as the photoperiodic regulation of flowering, seed germination, photomorphogenesis, shade avoidance and, hormone response pathways (Gangappa and Botto 2014; Kushwaha et al. 2018). Several abiotic stresses arise together in the field and most BBX proteins are reported to be involved in more than one abiotic stress responses (Liu et al. 2016; Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012; Min et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2012). Rice is consumed by more than half of the world’s population, however, productivity of rice is greatly affected by combination of abiotic stresses. Since plant BBX proteins are conserved, knowledge gain from studies of Arabidopsis BBX proteins can be applied on rice to identify functional orthologs of rice. Therefore, it is timely necessity to highlight the role of Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins in abiotic stress signaling to open up new avenues of genetic engineering for developing multistress-tolerant rice.

The role of BBX proteins in regulating plant growth and development under light-mediated signaling (Gangappa and Botto 2014; Yadav et al. 2020a), and hormonal pathways (Kushwaha et al. 2018) in Arabidopsis, and the role of BBX proteins in crop plants are already being reported (Talar and Kiełbowicz-matuk 2021). Since some BBX proteins are involved in multistress signaling, they can be considered as good candidate genes for developing multistress tolerance crops. Hence, the main focuses of the present review are to outline the BBX proteins involved in abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis and rice, discuss their roles in the regulation of abiotic stress responses and how this knowledge can be applied to develop abiotic stress tolerant rice using genetic engineering.

Nomenclature, structure and evolution of BBX proteins

Nomenclature of BBX proteins

Arabidopsis CONSTANS (CO) was identified as the first B-box protein, which contains B-box-1, B-box-2 domains at the N-terminus and a CCT domain at the C terminus (Putterill et al. 1995; Robson et al. 2001). Thereafter, numerous efforts have been made to identify plant B-box proteins, and 16 BBX proteins having one or two B-box domains, were identified in Arabidopsis. All 16 B-box proteins were named as CO-LIKE (COL1–COL16) proteins (Min et al. 2015; Ledger et al. 2001; Datta et al. 2006; Hassidim et al. 2009; Cheng and Wang 2005; Wang et al. 2013). Later, a few B-box proteins with two tandem B-box domains were identified in Arabidopsis and they were named as DBB1a, STO and STH (Wang et al. 2011; Nagaoka and Takano 2003; Holm et al. 2001). With the increase in research, the naming of the BBX protein became confusing as a single BBX protein was given different names by different research groups. For example, one BBX member was defined as LZF1, STH3, DBB3 (Chang et al. 2008; Datta et al. 2008; Kumagai et al. 2008). Also, CO-LIKE genes were identified in various plant species, including rice (Zobell et al. 2005; Griffiths et al. 2003). Griffiths et al. (Griffiths et al. 2003) investigated the CO-LIKE 16 genes in rice, and designated as OsA to OsP.

Hence, to facilitate the functional characterization of B-box proteins, Khanna et al. (Khanna et al. 2009) provided a uniform nomenclature to Arabidopsis BBX family. They identified a complete set of 32 Arabidopsis BBX proteins and renamed them as AtBBX1 to AtBBX32 (Khanna et al. 2009). CO became AtBBX1, and COL1 to 16 became AtBBX2 to 17. Subsequently, other proteins such as STH, STO, STH3, and DBB were named BBX18 to 32 (Table 1). For naming BBX genes and proteins, conventional rules are followed as “BBX” genes and “BBX” proteins, respectively (Khanna et al. 2009). Similarly, Huang et al. (Huang et al. 2012) assigned a uniform nomenclature for rice BBX proteins. Through a genome-wide survey they identified 30 rice BBX genes and named them as OsBBX1 to OsBBX30 (Table 2) (Huang et al. 2012). Naming and structural classification of BBX proteins in plant species other than Arabidopsis follow similar criteria proposed by Khanna et al. (Khanna et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Role of BBX proteins in abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis

| AGI number | Original name | BBX name | Role of BBX proteins in abiotic stresses |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT5G15840 | CO | AtBBX1 | Activated drought escape response under drought (Seki et al. 2007a), Upregulated by UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020) |

| AT5G15850 | COL1 | AtBBX2 | Regulated by cold stress (Sircar and Parekh 2019), ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT3G02380 | COL2 | AtBBX3 | Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT5G24930 | COL4 | AtBBX5 | Upregulated by ABA, mannitol and salt stress (Min et al. 2015). Improves ABA and salt tolerance (Min et al. 2015a) in Arabidopsis |

| AT5G57660 | COL5 | AtBBX6 | Upregulated by cold/Light (Riboni et al. 2016) |

| AT3G07650 | COL9 | AtBBX7 | Upregulated by cold/Light (Riboni et al. 2016) and UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020) |

| AT2G47890 | COL13 | AtBBX11 | Upregulated by cold/Light (Riboni et al. 2016) and UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020), Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT1G28050 | COL15 | AtBBX13 | Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT1G73870 | COL7 | AtBBX16 | Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT2G21320 | DBB1a | AtBBX18 | Induced by heat stress (Wang et al. 2013; Mbambalala et al. 2020), Negatively regulate thermotolerance (Wang et al. 2013a) and regulate thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis (Mbambalala et al. 2020)a |

| AT4G38960 | DBB1b | AtBBX19 | Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT4G39070 | DBB2 | AtBBX20 | Upregulated by UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020) |

| AT1G78600 |

LZF1/ STH3/ DBB3 |

AtBBX22 | Regulated by ABA and cADPR (Sánchez et al. 2004) |

| AT4G10240 | DBB4 | AtBBX23 | Upregulated by heat stress(Mbambalala et al. 2020), Regulate thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis (Mbambalala et al. 2020)a |

| AT1G06040 | STO | AtBBX24 | Upregulated by cold/Light (Riboni et al. 2016) and UV-B (Jiang et al. 2012), Increase salinity tolerance in yeast (Tiwari et al. 2010), Improves salinity tolerance (Nagaoka and Takano 2003a) and negatively regulate the UV-mediated photomorphogenesis (Jiang et al. 2012a) in Arabidopsis |

| AT2G31380 |

STH/ STH1 |

AtBBX25 | Upregulated by UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020) |

| AT5G54470 | AtBBX29 |

Upregulated by Cold/light (Riboni et al. 2016), Induced by cold (Shavrukov et al. 2017), Over-expression in sugarcane improves drought tolerance (Soitamo et al. 2008)a |

|

| AT3G21890 | AtBBX31 | Upregulated by UV-B (Yadav et al. 2019; Ulm et al. 2004), Enhances tolerance to UV-B radiation (Yadav et al. 2019)a | |

| AT3G21150 | AtBBX32 | Upregulated by UV-B (Lyu et al. 2020) |

BBX B-box, CO CONSTANS, COL CONSTANS LIKE, UV-B Ultraviolet-B, ABA Abscisic acid, cADPR cyclic ADP ribose, DBB DOUBLE B-BOX, LZF1 LIGHT-REGULATED ZINC FINGER1, STH3 SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG3, STO Salt tolerance, STH SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOGUE, STH1 SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOGUE1

aData collected from overexpression/mutant transgenic plant of the target gene

Table 2.

Role of BBX proteins in abiotic stresses in rice

| RAP Os ID | Original name | BBX name | Role of BBX proteins in abiotic stresses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Os01g0202500 | OsDBB3c | OsBBX1 | Upregulated by drought, cold, salinity, Fe, Ni, Cr, Cd, GA and MeJa (Shalmani et al. 2019), Regulated by NAA, GA3 and KT (Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os02g0176000 | OsBBX2 | Upregulated by drought, cold, salinity, GA, SA and MeJA (Shalmani et al. 2019) | |

| Os02g0606200 | OsSTH | OsBBX4 | Induced by salt (Yan et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2017), drought and ABA (Yan et al. 2012), Improves drought and salt tolerance in Arabidopsis (Yan et al. 2012)a |

| Os02g0646200 | OsBBX6 | Regulated by NAA, GA3 and KT(Huang et al. 2012) | |

| Os02g0724000 | OsN | OsBBX7 | Upregulated by cold, salinity, Fe, Ni, Cr, Cd, GA, SA and MeJA (Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os02g0731700 | OsK | OsBBX8 | Downregulated by drought stress (Liu et al. 2016; Shalmani et al. 2019), Negatively regulate the drought resistance (Liu et al. 2016a) and positively regulate the drought-induced leaf senescence in rice (Liu et al. 2016a), Upregulated by salt, cold, GA, ABA, SA, MeJA, Fe, Ni, Cr,Cd (Shalmani et al. 2019), NAA and KT (Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os03g0351100 | OsP | OsBBX9 | Downregulated by ABA (Jain et al. 2007), Upregulated by Ni, (Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os03g0711100 |

OsJ/ OsCOL10 |

OsBBX10 | Downregulated by drought(Tan et al. 2016) |

| Os04g0493000 | OsSTO | OsBBX11 | Downregulated by NAA, GA3 and KT(Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os04g0497700 | OsC | OsBBX12 | Upregulated by cold stress (Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os05g0204600 | OsDBB3b | OsBBX14 | Upregulated by Fe, Ni, Cr, GA, ABA, SA and MeJa(Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os06g0152200 | OsDBB3a | OsBBX16 | Upregulated by cold, salinity, GA and MeJa(Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os06g0264200 | OsL | OsBBX17 | Downregulated by drought (Tan et al. 2016), Upregulated by cold, drought, Fe, Ni, Cr, Cd, GA, SA and MeJA (Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os06g0275000 | Hd1/OsA | OsBBX18 | Upregulated by NAA, (Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os06g0298200 | OsM | OsBBX19 | Upregulated by drought, cold, salinity, Fe, Ni, Cr, and Cd, GA, SA and MeJA (Shalmani et al. 2019) |

| Os06g0661200 | OsBBX21 | Downregulated by GA3 (Huang et al. 2012) | |

| Os06g0713000 | OsBBX22 | Upregulated by salinity stress(Jain et al. 2007) | |

| Os08g0178800 | OsBBX24 | Upregulated by drought, cold, Fe, Ni, Cd, GA, SA and MeJA (Shalmani et al. 2019), Downregulated by NAA, GA3 and KT (Huang et al. 2012) | |

| Os08g0536300 | OsO | OsBBX26 | Regulated by NAA, GA3 and KT (Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os09g0240200 |

OsCO3/ OsB |

OsBBX27 | Downregulated by NAA, GA3 and KT (Huang et al. 2012) |

| Os09g0509700 | OsBBX28 | Upregulated by NAA, (Huang et al. 2012) | |

| Os12g0209200 | OsBBX30 | Regulated by NAA, GA3 and KT (Huang et al. 2012) |

BBX B-box, RAP Rice Annotation Project, Os Oryza sativa, DBB DOUBLE B-BOX, GA Gibberellic Acid, MeJa Methyl jasmonate, NAA Naphthalene Acetic Acid, KT kinetin, SA Salicylic acid, STH SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG, ABA Abscisic acid, COL CONSTANS LIKE, STO Salt tolerance, Hd1 heading date 1

aData collected from overexpression/mutant transgenic plant of the target gene

To avoid any confusion of nomenclature stated among different studies, the nomenclature adopted by Khanna et al. (Khanna et al. 2009) and Huang et al. (Huang et al. 2012) will be used for Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins, respectively, in this review.

Structural domains of BBX proteins

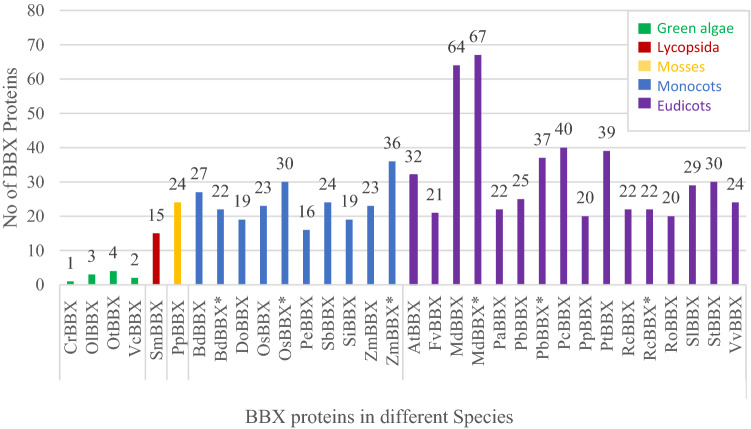

The development of comparative genomics has opened the path to study the BBX proteins across species of the same gene family and across diverse gene families (Shalmani et al. 2018, 2019; Huang et al. 2012; Crocco and Botto 2013). As a result, BBX proteins have been identified from more than 25 plant species from green algae to dicotyledons (Shalmani et al. 2018, 2019; Huang et al. 2012; Crocco and Botto 2013; Khanna et al. 2009; Chu et al. 2016; Wei et al. 2020; Talar et al. 2017; Cao et al. 2017, 2019; Zou et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2018; Peers and Niyogi 2008) and followed the nomenclature established by Khanna et al. (Khanna et al. 2009) (Fig. 1). The same BBX name, RcBBX is given to both Rosa chinensis (Shalmani et al. 2018) and Ricinus communis (Crocco and Botto 2013) and, therefore, nomenclature should be expanded to name such BBX proteins in different species to avoid confusion among different studies. The highest number of BBX proteins have been identified from Malus domestica (Apple) (Shalmani et al. 2018), whereas the lowest number of BBX proteins have been identified from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Crocco and Botto 2013) (Fig. 1). All identified BBX proteins have one or two B-box domains indicating that the conserved nature of BBX protein across all species ranging from green algae to dicotyledons.

Fig. 1.

Number of BBX proteins identified from plant species in different studies including, BBX protein name and species name. The numbers in parentheses indicate references. CrBBX: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Crocco and Botto 2013), OlBBX: Ostreococcus lucimarinus (Crocco and Botto 2013), OtBBX: Ostreococcus tauri (Crocco and Botto 2013), VcBBX: Volvox carteri (Crocco and Botto 2013), SmBBX: Selaginella moellendorffii (Crocco and Botto 2013), PpBBX: Physcomitrella patens (Crocco and Botto 2013), BdBBX: Brachypodium distachyon (Crocco and Botto 2013), BdBBX*: Brachypodium distachyon (Shalmani et al. 2019), DoBBX: Dendrobium officinale (Cao et al. 2019), OsBBX: Oryza sativa (Crocco and Botto 2013), OsBBX*: Oryza sativa (Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012), PeBBX: Phalaenopsis equestris (Cao et al. 2019), SbBBX: Sorghum bicolor (Shalmani et al. 2019), SiBBX: Setaria italic (Shalmani et al. 2019), ZmBBX: Zea mays (Crocco and Botto 2013), ZmBBX*: Zea mays (Shalmani et al. 2019), AtBBX: Arabidopsis thaliana (Crocco and Botto 2013; Khanna et al. 2009), FvBBX: Fragaria vesca (Shalmani et al. 2018), MdBBX: Malus domestica (Liu et al. 2018), MdBBX*: Malus domestica (Shalmani et al. 2018), PaBBX: Prunus avium (Shalmani et al. 2018), PbBBX: Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. (Cao et al. 2017) PbBBX*: Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. (Zou et al. 2018), PcBBX: Pyrus communis (Shalmani et al. 2018), PpBBX: Prunus persica (Shalmani et al. 2018), PtBBX: Populus trichocarpa (Crocco and Botto 2013), RcBBX: Rosa chinensis (Shalmani et al. 2018), RcBBX*: Ricinus communis (Crocco and Botto 2013), RoBBX: Rubus occidentalis (Shalmani et al. 2018), SlBBX: Solanum lycopersicum (Chu et al. 2016), StBBX: Solanum tuberosum (Talar et al. 2017), VvBBX: Vitis vinifera L. (Wei et al. 2020)

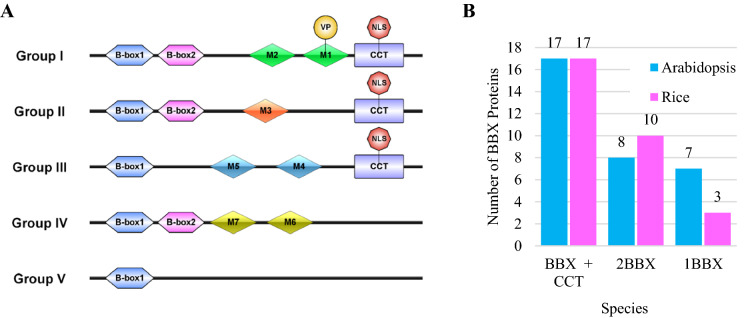

Recent studies on plants, including Arabidopsis (Khanna et al. 2009) and rice (Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012) have classified BBX proteins into five structural groups based on the presence of B-box and CCT domains (Fig. 2A) (Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012; Crocco and Botto 2013; Khanna et al. 2009) indicating the conserved domain topology of BBX proteins. Groups I and II contain two B-box domains and one CCT domain with differences in their B-box2 domain. Members of group III contain a B-box1 and a CCT domain. Structural group IV possesses two B-box domains. Proteins in structural group V have one B-box 1 domain (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

BBX protein domains and structure groups. A Five structure groups of BBX members of green plants including Arabidopsis and rice. BBX proteins contain seven novel motifs (M1 to M7) specific to each structural group, except BBX proteins of structure group V. The M1 motif in structure group I contains a conserved valine-proline motif. A putative nuclear localization signal is present in the NH2-terminal half of the CCT domain. B B-box and CCT domain constitution of Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins family. Abbreviations: BBX B-box, CCT CONSTANS, CO-LIKE and TOC1 domain

The B-box domains are two types, B-box1 and B-box2, based on their conserved cysteine (C) and histidine (H) residues that bind with Zn2+, and the spacing of zinc-binding residues (Massiah et al. 2006, 2007). They are ~ 40 residues in length. The B-box1 domain is positioned N-terminal to the B-box2 domain by 5–20 amino acid residues, (Fig. 2A) (Khanna et al. 2009). B-box domains participate in transcriptional regulation of proteins in plant growth and development (Datta et al. 2007, 2008; Gangappa and Botto 2014; Talar et al. 2017). In response to abiotic stresses, Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins mediate protein–protein interactions through their B-box domains, negatively regulate photomorphogenic UV-B responses by interacting with both CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1) and ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) (Jiang et al. 2012). Aspartic acid (Asp) to alanine (Ala) substitutions in the B-boxes of AtBBX24 reveals that both the B-boxes are essential to interact with HY5 (Gangappa et al. 2013a). Also, aspartic acid residues in the B-box domain are crucial for transcriptional activation and DNA-binding (Crocco and Botto 2013; Datta et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2018). Yeast two-hybrid screening has identified that OsARID3 and OsPURα proteins interact with the B-box domains of OsBBX8 under drought stress (Liu et al. 2016). AtBBX22 is regulated by ABA (Sánchez et al. 2004). Furthermore, yeast two-hybrid assay indicated that the B-box2 of AtBBX22 is essential for HY5 interaction (Datta et al. 2008). Further studies are needed to explain the functions of the B-box domain in mediating protein–protein interactions under abiotic stress conditions.

B-box proteins in structure groups I, II and III contain a CCT domain near the carboxy terminus, which is ~ 45 amino acid residues in length (Fig. 2A) (Huang et al. 2012; Lyu et al. 2020). In BBX proteins, the most conserved domain is CCT domain (Shalmani et al. 2019). CCT domain has a large number of arginine (R), followed by conservative tyrosine (Y), lysine (K), alanine (A) and phenylalanine (F) residues (Lyu et al. 2020). A putative nuclear localization signal (NLSs) present at the NH2-terminal half of the CCT domain (Fig. 2A) localizes BBX protein to the nucleus (Strayer et al. 2000; Yan et al. 2011). Additionally, CCT domain is important in mediating protein–protein interactions. The CCT domain of AtBBX1 and AtBBX16 interact with DNA-binding proteins such as Nuclear Factor-Y (NF-Y) (Zhang et al. 2014; Gnesutta et al. 2017). CCT domain of AtBBX10 is also involved in the interaction and subsequent degradation of AtBBX10 by COP1 (Ordoñez-Herrera et al. 2018).

M1 to M7 novel motifs specific to structural groups I to IV were identified by analyzing the BBX protein sequences of 214 BBX proteins belong to 12 plant species (Fig. 2A) (Crocco and Botto 2013). Structural motifs M1 (82%) and M2 (77%) are present in BBX proteins of group I, M3 is present in 73% of the structural group II, M4 (83%) and M5 (67%) are present in the structural group III and M6 (64%) and M7 (98%) are present in structural group IV (Crocco and Botto 2013). However, functions of M1 to M7 motifs remain to be unravel except for the M6 motif, which indicated a possible role in determining divergent functions of group IV members in light signaling (Job et al. 2018). The M1 motif present in the structural group I contains a valine-proline (VP) motif of six amino acids (Fig. 2A) (Gangappa and Botto 2014; Talar et al. 2017; Kushwaha et al. 2018). It is located at the N-terminal to the CCT domain by 16–20 amino acids (Gangappa and Botto 2014; Talar et al. 2017; Kushwaha et al. 2018). VP motif is present in two structural group IV BBX members AtBBX24 and AtBBX25 (Holm et al. 2001). Studies on VP motif of AtBBX24 and AtBBX25 show that VP motif is important for interaction with the WD40 domain of COP1 (Holm et al. 2001). The evolution of BBX proteins has radiated variation into NLSs, VP and M1–M7 motifs of each structural group suggesting that these evolutionary changes outside the B-box domain lead to functional diversity of BBX proteins in plants (Crocco and Botto 2013; Gangappa and Botto 2014; Kim et al. 2013).

AtBBX and OsBBX proteins vary in size, ranging from 117 to 433 (Lyu et al. 2020) amino acids and 210 to 488 (Huang et al. 2012) amino acids in length, respectively. Rice BBX protein family contain 17 OsBBXs that contain 1 or 2 B-box domains and 1 CCT domain, 10 OsBBXs having 2 B-box domains and 3 OsBBXs with only 1 B-box domain (Fig. 2B). Arabidopsis BBX protein family contain 17 AtBBXs with 1 or 2 B-box domains and 1 CCT domain, 8 AtBBXs having 2 B-box domains and 7 AtBBXs with only 1 B-box domain (Fig. 2B). The B-box and CCT domain constitution of Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins suggest that the rice and Arabidopsis BBX genes have originated from a common ancestor (Huang et al. 2012).

Evolution of plant BBX proteins

B-box domains are present in proteins in both plant and animal kingdoms. In animals, B-box domains are often found with proteins containing RING and coiled-coil domains. In plants, B-box domains are either present alone or associated with the CCT domain (Khanna et al. 2009; Meroni and Diez-roux 2005). In the plant kingdom, BBX genes are present in different species ranging from algae to monocotyledons and dicotyledons (Crocco and Botto 2013). The presence of BBX proteins in green algae suggests that the BBX proteins evolved ∼1 billion years ago (Khanna et al. 2009; Zou et al. 2018). However, BBX proteins of most green algae possess only one B-box domain, whereas Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, CrBBX1 has two B-box domains suggesting that B-box duplication events have started from green algae at an early stage of green plant evolution, at least 450 million years ago (Crocco and Botto 2013). An addition of a CCT domain has resulted in CO-LIKE BBX proteins containing two B-box domains and a CCT domain (Crocco and Botto 2013). Comparative analysis of plant genomes from monocotyledons to dicotyledons suggested that, during green plant evolution, segmental duplication events and internal deletion events of the B-box domains have resulted the origin of different structural groups of BBX proteins (Crocco and Botto 2013).

Major subgroups of Arabidopsis BBX genes are also present in rice BBX genes (Fig. 2A) (Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012; Khanna et al. 2009). Thus, they predate monocotyledons/dicotyledons divergence. Phylogenic analysis shows that most OsBBX and AtBBX are clustered in species-specific clades, demonstrating that the expansion of OsBBX and AtBBX gene family had occurred independently after the monocotyledons and dicotyledons divergence (Huang et al. 2012). AtBBXs orthologous genes were identified in rice (Huang et al. 2012). As an example, in the regulation of flowering time, the AtBBX1ortholog of rice, OsBBX18 is functionally similar to Arabidopsis AtBBX1 (Yano et al. 2000). Hence, unknown functions of OsBBX genes can be identified through AtBBX functional orthologs. These results indicate the conserved domain organization and molecular function of the B-box domain during evolution.

Compared to the Arabidopsis genome, rice has a larger genome with approximately 1.5 times genes (Vij et al. 2006). However, rice genome has 30 BBX genes, whereas Arabidopsis has 32 BBX genes (Huang et al. 2012; Khanna et al. 2009). Having fewer BBX genes in rice than in Arabidopsis may be due to the variable number of genome duplication events in Arabidopsis and rice (Yu et al. 2005; Paterson et al. 2004). Analysis of the tandem and segmental duplication events of the OsBBX and AtBBX gene families revealed that 18 OsBBXs and 6 AtBBXs participated in the segmental duplication, respectively, whereas gene tandem repeats were not found (Huang et al. 2012; Lyu et al. 2020). Thus, segmental duplications have mainly led to the expansion of the OsBBX and AtBBX gene families.

The role of Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins in plant abiotic stress

BBX proteins in plant abiotic stress responses

Abiotic stress responses have been mainly associated with transcriptional regulation (He et al. 2018a). Among them, BBX proteins play a key role in regulatory networks in plants during abiotic stress tolerance (Yang et al. 2014). Over-expression studies of the target BBX genes in Arabidopsis and rice showed that some proteins of the BBX family participate in abiotic stress responses (Tables 1 and 2). Also, large-scale transcriptomic data and expression profiles evaluated through qRT-PCR from various studies suggested the response of numerous BBX genes toward abiotic stresses (Tables 1 and 2). The various bioinformatics analysis of putative promoter regions of BBX genes show that most of these genes carry well-known abiotic stress-responsive elements. In rice, heat-shock element (HSE), a cis-acting element involved in heat stress responsiveness, and MYB transcription factor binding site (MBS) which is involved in drought-inducibility, are found on putative promoter regions of 12 OsBBX genes (Huang et al. 2012). Arabidopsis BBX members of groups I, II, III and V carry drought-responsive cis elements on their putative promoter region (Lyu et al. 2020). Here, we have taken an attempt to summarize the functions of Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins in abiotic stress signaling.

The role of BBX proteins in UV-B light stress responses

Although light regulate plant growth and development, light can simultaneously act as a stress factor on plants (Yin and Ulm 2017). Light stress is mainly caused by UV-B light (280–320 nm) and it depends on the intensity and duration of exposure (Banerjee and Roychoudhury 2016). UV-B radiation stimulate morphogenic changes as well as activate stress responses in plants (Yadav et al. 2019). Upon the perception of UV-B radiation by photoreceptor ULTRA-VIOLET RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UVR8), UVR8 dimer is converted to its monomer. The active UVR8 monomer interacts with COP1 and this complex translocates to the nucleus (Yadav et al. 2020b). Activated UVR8 mediates the expression of downstream genes in HY5-dependent as well as independent manner (Fig. 3) (Yadav et al. 2019).

Fig. 3.

Model illustrating action of BBX proteins in abiotic stress signaling pathways. UV‐B signal is perceived by UV-B receptor UVR8 in the cytosol, resulting monomerization of UVR8 dimer and binding to COP1. UVR8-COP1 complex translocates to the nucleus and activates HY5 protein, leading to UV-B-regulated gene expression and photomorphogenesis. RUP1 and RUP2 are negative regulators of UV‐B signaling and act by promoting re‐dimerization of active UVR8 monomers. A Regulation of photomorphogenesis under low fluence rate of UV-B light. AtBBX24 negatively regulate the UV-mediated photomorphogenesis by interacting with COP1, RCD1 and suppressing HY5 activity whereas AtBBX31 positively regulates the UV-B-mediated photomorphogenesis, in a HY5 independent manner. HY5 physically binds to promoter of AtBBX31 and enhances its transcription whereas overexpression of AtBBX31 enhances HY5 transcript levels in a UVR8-dependent manner. B Regulation of stress response under high fluence rate of UV-B light. AtBBX31 modulates the stress tolerance in a HY5-dependent manner. C At elevated temperatures AtBBX18 and AtBBX23 promote thermomorphogenesis by inhibiting the ELF3 and promoting the accumulation of PIF4. D Under salinity stress AtBBX24 interacts with HPPBF1 and HPPBF-1 interacts with promoters of salinity stress associated genes to promote stress responses. The solid lines with arrow head indicate positive regulation. Solid lines with flat head indicate negative regulation. Abbreviations: BBX: B-box, UV-B: Ultraviolet-B, UVR8: ULTRA-VIOLET RESISTANCE LOCUS 8, COP1: CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1, HY5: ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5, RCD1: RADICAL-INDUCED CELLDEATH1, ELF3: Early flowering 3, PIF4: Phytochrome B-interacting factor 4, HPPBF-1: H-protein promoter binding factor1

Until now, function and interaction of AtBBX24 (Jiang et al. 2012) and AtBBX31 (Yadav et al. 2019; Ulm et al. 2004) in UV-B-mediated signaling have been studied (Fig. 3A,B) (Table 1). However, it needs further verification. Under low doses of UV-B light, AtBBX24 interacts with both COP1 and HY5 and negatively regulate photomorphogenic responses (Fig. 3A) (Jiang et al. 2012). Thus, Atbbx24 mutant is hypersensitive to UV-B radiation and shows a dwarf phenotype (Jiang et al. 2012). Moreover, AtBBX24 interacts with RADICAL-INDUCED CELLDEATH1 (RCD1), which is a negative regulator of AtBBX24 (Belles-boix et al. 2000; Jiang et al. 2009; Jaspers et al. 2009). These results indicate that RCD1–AtBBX24 complex has a negative function in UV-B signaling (Fig. 3A).

Furthermore, AtBBX7 and AtBBX8 interact with RCD1 (Jaspers et al. 2009). AtBBX7 and AtBBX25 are upregulated by UV-B radiation (Lyu et al. 2020). AtBBX24 and its homolog AtBBX25 additively suppress HY5 function (Gangappa et al. 2013a, b). Bioinformatic analysis of Arabidopsis BBX genes suggests that AtBBX24 and AtBBX25 have similar functions (Lyu et al. 2020). However, further studies are needed to show the involvement of AtBBX7, AtBBX8 and AtBBX25 in UV-B signaling pathway.

Under low intensity UV-B light, AtBBX31 overexpression lines displayed reduction in hypocotyl length in a HY5 independent manner, indicating that AtBBX31 positively regulate UV-B-mediated photomorphogenesis (Fig. 3A) (Yadav et al. 2019). Additionally, AtBBX31 promotes tolerance to high intensity UV-B radiation in a HY5-dependent manner, by enhancing the levels of UV-protective compounds, and regulating downstream gene expression for photoprotection and DNA repair (Fig. 3B) (Yadav et al. 2019, 2020a). However, there is no evidence of direct interaction between AtBBX31 and HY5 (Yadav et al. 2019). Bioinformatic analysis of Arabidopsis BBX genes showed that the promoters of AtBBXs contain light-responsive cis- elements (Lyu et al. 2020). Analysis of transcriptome data and qRT-PCR data of BBX genes showed that all BBX genes reported; AtBBX1, 2 7, 20, 22, 24, 25, 31, 32 are induced by UV-B radiation (Table 1). Their mechanisms in regulating UV-B induced photomorphogenesis and stress responses are yet to be discovered.

It has been reported that most of the Oryza japonica varieties are more resistant to high dose of UV-B radiation than most of the Oryza indica varieties (Ueda and Nakamura 2011). Under high fluence rate of UV-B, AtBBX31 regulates the accumulation of UV-protective pigments such as chlorophyll and anthocyanin in overexpressed Arabidopsis plants (Yadav et al. 2019). Similarly, OsBBX14 overexpressed in Arabidopsis plants, show accumulation of both anthocyanin and chlorophyll (Kim et al. 2018). OsBBX14 directly interact with OsHY5 through its second B-box domain to activate anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, OsC1 or OsB2 (Kim et al. 2018). However, the role of OsBBX14 in UV-B stress responses is still unknown.

The role of BBX proteins in drought stress responses

Drought stress seriously affect the crop productivity. In Arabidopsis, transcriptional regulation of drought-inducible gene expression occurs via abscisic acid (ABA) independent as well as ABA-dependent signaling pathway (Seki et al. 2007). In rice, ABA-dependent signaling pathway is preferred in response to drought stress (Sircar and Parekh 2019). Up to now, four BBX genes in Arabidopsis and rice, namely, AtBBX1, AtBBX29 (Table 1) (Riboni et al. 2016; Mbambalala et al. 2020), OsBBX8 and OsBBX4 (Table 2) (Liu et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2012), have been functionally characterized as drought-responsive genes. AtBBX1 is a well-characterized flowering time regulator (Putterill et al. 1995; Robson et al. 2001; Tiwari et al. 2010). Additionally, it promotes drought-induced early flowering, known as ‘drought escape’ response in Arabidopsis (Riboni et al. 2016). When plants are exposed to drought stress, they undergo drought escape response by activation of floral transition and set seeds before the stress becomes a severe threat (Shavrukov et al. 2017). AtBBX1 mutants exposed to drought stress show no accumulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), indicating that AtBBX1 is required for drought-dependent activation of FT (Riboni et al. 2016). AtBBX1 triggers the transcriptional activation of FT on the ABA-dependent pathway, to activate floral induction under drought stress (Riboni et al. 2016).

AtBBX29 overexpressed, Saccharum spp. hybrid (sugarcane) has enhanced health and better survival rates under drought stress and shows delaying leaf-rolling, wilting, and leaf tip yellowing (Mbambalala et al. 2020). AtBBX29 affects photosynthetic machinery (Mbambalala et al. 2020; Soitamo et al. 2008). AtBBX29-overexpressing sugarcane plants maintain a higher relative water level and better photosynthesis under drought stress (Mbambalala et al. 2020). OsBBX8, a group II rice BBX protein, that regulates grain number, heading date, and plant height, regulates drought stress. OsBBX8-overexpressed plants show an earlier leaf-rolling indicating that OsBBX8 negatively regulates drought resistance. Furthermore, OsBBX8-overexpressing plants show leaf tip-yellowing phenotype and upregulate many senescence-associated genes indicating that OsBBX8 accelerates the drought-induced early leaf senescence (Liu et al. 2016).

Furthermore, OsBBX8 interacts with OsARID3, OsPURα, and three 14-3-3 proteins (GF14b, GF14c and GF14e) (Liu et al. 2016). OsARID3 is a rice AT-rich Interaction Domain (ARID) family protein and it is involved in the development of Shoot Apical Meristem (SAM) (Xu et al. 2015). OsPURα, is a highly conserved, targeted DNA and RNA-binding protein (Gallia et al. 2000). OsPURα regulates rice sucrose synthase 1 (RSus1) expression in response to sucrose (Chang et al. 2011). OsARID3 and OsPURα expressed in rice leaves show similar expression patterns to OsBBX8. Furthermore, in OsARID3-overexpressed and OsBBX8-overexpressed plants, regulation of senescence-associated genes, isocitrate lyase (ICL) and malate synthase (MS), occur antagonistically (Liu et al. 2016). Three OsBBX8 interacting 14-3-3 proteins, GF14b, GF14c and GF14e, respond differently to salinity, drought and ABA stresses (Chen et al. 2006a; Liu et al. 2016). All these evidences suggest that OsBBX8 interacting proteins play a significant role in drought stress. However, to strengthen the knowledge of the regulatory network of OsBBX8, OsARID3, OsPURα, GF14b, GF14c and GF14e in drought stress further investigation is necessary.

Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable element (MITE) is involved in RNAi-like mechanism in plants. A recent study showed that rice dicer-like 3 homolog, OsDCL3a produces 24-nt siRNAs from MITE, that regulate some agronomic traits (Wei et al. 2014). Interestingly, A 217-nt inverted region called MITE is found in the 3’ untranslated region of OsBBX8, which translationally represses the OsBBX8 depending on OsDCL3a (Shen et al. 2017). Findings on the regulation of OsBBX8 at the protein level will be a promising engineering method for developing agronomically useful traits such as plant height, panicle morphology of and abiotic stress tolerance.

Microarray data obtained from rice seedlings has revealed that two other members of group II, namely, OsBBX10 and OsBBX17 are down-regulated under drought stress (Jain et al. 2007). However, OsBBX10 the closest homolog of OsBBX8 also functions as a grain number, plant height and heading date-associated gene (Tan et al. 2016). Interestingly, expression of OsBBX10 is regulated by another gene named Ghd7, a grain number, plant height, and heading date7 gene (Tan et al. 2016). Ghd7- overexpressing lines have abundant transcripts of OsBBX10 and show increased drought sensitivity (Tan et al. 2016; Weng et al. 2014). Therefore, OsBBX10 and Ghd7 might participate in drought stress responses, but their functions in drought stress are still unknown. OsBBX4, which has the highest homology to AtBBX25 is induced by drought stress (Yan et al. 2012). Expression of OsBBX4 in Arabidopsis improves drought tolerance and up-regulates the expression of stress-related genes, KIN1, RD29A and RD22 (Yan et al. 2012).

The expression analysis of 12 OsBBX genes under drought stress have shown that expression of OsBBX1, 2, 17, 19 and 24 were upregulated under drought stress (Table 2) (Shalmani et al. 2019). Promoter analysis of BBX gene family in Arabidopsis has shown that each member of subfamily I, II, III and V contain drought-responsive elements (Lyu et al. 2020). Similarly, promoter analysis of OsBBX gene family has identified 12 OsBBX genes (OsBBX4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 19, 21, 24, 28 and 30) with MBS (Huang et al. 2012). Functions, interacting partners and the mode of drought regulation of BBX members are not yet fully discovered.

The role of BBX proteins in salinity stress responses

Soil salinity negatively affects plant growth rate. It is essential to control the intracellular Na+ /K+ ratio in plant cells for salinity tolerance (Hoang et al. 2016). Salinity-tolerant genotypes can resist low soil water potential by accumulating osmolytes and protective proteins. Salinity stress affects most food crops and, therefore, greatly reduces the agricultural productivity.

AtBBX24 (Nagaoka and Takano 2003; Lippuner et al. 1996), AtBBX5 (Min et al. 2015) (Table 1) and OsBBX4 (Yan et al. 2012) (Table 2) have been studied for salinity stress tolerance. The Arabidopsis salt tolerance protein AtBBX24 was first identified in a screening performed using a salinity-sensitive phenotype of yeast, which was deficient in calcineurin (Lippuner et al. 1996). AtBBX24 complemented yeast calcineurin mutants and increased salinity tolerance of calcineurin mutants and wild-type yeast (Lippuner et al. 1996). Furthermore, AtBBX24 was found to be expressed in leaves, roots and flowers. In Arabidopsis, the highest level of expression was observed in leaves (Lippuner et al. 1996). However, the expression of AtBBX24 in Arabidopsis was not induced by salinity stress treatments (Nagaoka and Takano 2003; Lippuner et al. 1996). AtBBX24 overexpressing Arabidopsis plants were salinity tolerant and showed increased root length (Nagaoka and Takano 2003). In addition, AtBBX24 binds to a H-protein promoter binding factor-1 (HPPBF-1), which contains a single, highly conserved Myb-type DNA-binding domain (Fig. 3D) (Nagaoka and Takano 2003). Interestingly, the transcript level of HPPBF-1 is enhanced by salinity stress (Nagaoka and Takano 2003). Both AtBBX24 and HPPBF-1 are localized in the nucleus. It can be suggested that HPPBF-1 interact with promoters of salinity stress associated genes similar to single MYB-type DNA-binding domain proteins CrBPF-1 (Fits et al. 2000) and PcMYB1 (Feldbri et al. 1997). These observations suggested the involvement of AtBBX24 and HPPBF-1 in salinity stress responses in Arabidopsis (Fig. 3D).

Furthermore, AtBBX24 physically interacts with an Arabidopsis protein RCD1 (Lippuner et al. 1996). RCD1 complements yeast AP-1 like transcription factor (Yap1−) mutant and increases oxidative stress tolerance of Yap1− mutant and wild-type yeast. (Belles-boix et al. 2000). In addition, under salinity or oxidative stress SOS1 protein physically interacts with RCD1 (Katiyar-agarwal et al. 2006). The SOS1 protein is a Na+/H+ antiporter, and extrude toxic Na+ from the cells to maintain the salinity concentration (Zhu 2002). Interestingly, using rcd1, sos1 and sos1 rcd1 double mutants, it has been revealed that SOS1 is involved in oxidative stress tolerance, and RCD1 functions in salinity tolerance (Katiyar-agarwal et al. 2006). Thus, by interacting with RCD1, AtBBX24 may be functioning in ion-homeostasis and oxidative stress responses to create salinity stress tolerance in plants. However, the mode of action of AtBBX24 remains obscure. Arabidopsis AtBBX5 is another salinity stress‐responsive BBX protein. Compared to the wild type, atbbx5 mutant lines were highly sensitive to salinity stress, whereas AtBBX5 overexpressing transgenic lines were less sensitive to salinity stress during germination and cotyledon greening (Min et al. 2015).

Rice seedlings exposed to 200 mmol/L−1 NaCl stress showed increased OsBBX4 expression under salinity stress (Yan et al. 2012). Heterologous expression of rice BBX protein OsBBX4, in Arabidopsis showed up-regulation of stress-related genes, KIN1, RD29A and COR15 under salinity stress and improved salinity tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis (Yan et al. 2012). This is further supported by a study on root-specific transcript profiling of rice that identifies the transcript of OsBBX4 in the presence of salinity stress (Cotsaftis et al. 2011). Salinity-tolerant lines, FL478, Pokkali, and IR63731 show expression of OsBBX4 under salinity stress, but salinity-sensitive IR29 does not show a significant response, suggesting that OsBBX4 is more related to salinity tolerance (Cotsaftis et al. 2011).

The expression profiles of OsBBX genes evaluated through qRT-PCR revealed, up regulation of transcript levels of rice OsBBX1, 2, 7, 8, 16 and 19 in response to salinity stress (Table 2). Furthermore, cDNA array analysis of putative rice transcription factors under salinity stress treatment, has identified upregulated transcript level of OsBBX22 (Wu et al. 2006). Several BBX genes of Arabidopsis and rice carry stress-responsive cis-regulatory elements in their putative promoter sequences (Huang et al. 2012; Lyu et al. 2020). The role of most elements in salinity stress responses is yet to be characterized.

The role of BBX proteins in heat and cold stress responses

Hot or cold temperature stresses can impair function and development of plants. Plants possess inducible mechanisms of acquired thermotolerance and cold acclimation in response to heat and cold stresses, respectively. At molecular level, heat stress leads to an increased risk of protein misfolding. When plants are exposed to heat stress, heat-shock proteins (HSPs) will be induced by heat-shock transcription factors (HSFs) to medicate heat stress response (HSR) (Guo et al. 2016).

The Arabidopsis BBX protein AtBBX18, is a well-characterized negative regulator in photomorphogenesis (Wang et al. 2011). Additionally, AtBBX18 negatively regulates the thermotolerance in Arabidopsis (Wang et al. 2013). AtBBX18 is upregulated by heat stress (Wang et al. 2013; Ding et al. 2018). AtBBX18-overexpressing plants showed the lowest germination frequency and survival rate, whereas AtBBX18 under-expressing plants showed higher germination frequency and survival rate, under heat stress (Wang et al. 2013). Moreover, AtBBX18 down-regulates the expression of genes involved in heat stress, such as digalactosyl diacylglycerol synthase 1 (DGD1), Hsp70, Hsp101, and cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 2 (APX2), and positively regulates the expression of HsfA2 under heat stress (Wang et al. 2013). DGD1 is involved in enhanced thermotolerance in Arabidopsis independently from the HSP pathway (Chen et al. 2006b). These results suggested that under heat stress, AtBBX18 may regulate thermotolerance through HsfA2 and downstream HSPs, as well as DGD1-mediated signaling pathway. In addition to the role in thermotolerance, AtBBX18 control thermomorphogenesis by interacting with AtBBX23 (Fig. 3C) (Ding et al. 2018). Expression of AtBBX18 and AtBBX23 are upregulated under elevated temperatures. At elevated temperatures AtBBX18 and AtBBX23 interact with early flowering 3 (ELF3) and negatively regulate ELF3 protein level, which results in an increased level of phytochrome B-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) (Ding et al. 2018) (Quint et al. 2016). Increased level of PIF4 then induce hypocotyl elongation at elevated temperatures (Fig. 3C) (Ding et al. 2018). All together, these findings indicate that AtBBX18 and AtBBX23 positively regulate temperature induced hypocotyl elongation (Fig. 3C). In rice, the presence of HSE in the promoter region of 12 OsBBXs, including OsBBX1, 2, 8, 9, 13, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26 and 28, strongly suggested that OsBBX genes have a putative role in heat stress responses (Huang et al. 2012). However, there is no evidence for functionally characterized rice BBX genes that is involved in heat stress.

Among several cold signaling pathways, C-repeat-binding factors (CBF) pathway is the best characterized and the key regulatory pathway in plants (Liu et al. 2019). Additionally, an EE–ABREL cold response pathway that is independent of CBF cold signaling pathway, has been identified in Arabidopsis (Mikkelsen et al. 2009). The promoter region of AtBBX29 includes one evening element (EE) motif (AAAATATCT), two EE-like (EEL) motifs (AATATCT), one CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1-binding site (AAAAATCT) and six ABRE-like (ABREL) motifs (ACGTG). Deletion analysis demonstrated that the EE/EEL coupling with ABREL motifs act together for cold induction of AtBBX29 (Mikkelsen et al. 2009). However, understanding of an EE–ABREL cold response pathway in signal perception and response to cold stress, require further investigation. Microarray studies demonstrate that Arabidopsis BBX genes AtBBX2 (Hannah et al. 2005), 6, 7, 11, 24 and 29 (Soitamo et al. 2008) are differentially expressed in response to low temperatures (Table 1).

Analysis of gene expression of 12 rice BBX genes have shown that OsBBX1, 2, 7, 8, 12, 16, 17, and 19 are induced by cold stress. (Table 2). Transcriptome analysis of developing rice seedlings under cold stress has revealed that OsBBX29 is upregulated under cold stress (Reyes et al. 2003). There are no research reports regarding well-characterized rice BBX proteins that participate in the cold stress responses so far.

BBX proteins in other stress responses

In addition to UV-B, drought, salinity, heat and cold stresses, changes in expression of BBX proteins are observed under heavy metal stress and application of exogenous hormones. Soil contamination with heavy metals such as Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni and Zn cause stress on plants generating serious physiological and structural disturbances. As a consequence, reactive oxygen species (ROS), are accumulated in cells resulting in disruption of the redox homeostasis of cells. Plants have different defense mechanisms to cope with heavy metal stress, including reduction of heavy metal uptake and activation of various antioxidants (Tiwari and Lata 2018). There is a significant change in transcript levels of some OsBBX genes in response to heavy metals (Table 2), but how these OsBBXs regulate heavy metal stress is not yet characterized. The transcript profiles of 12 OsBBX genes show that transcript levels of OsBBX1, 7, 8, 17, and 19 are significantly affected by Fe, Ni, Cr, and Cd metals (Table 2). Transcript levels of OsBBX14 and 24 have been enhanced by Fe, Ni, Cr and Fe, Ni, Cd, respectively (Table 2). Expression of OsBBX9 is highly induced by Ni stress (Table 2) (Shalmani et al. 2019).

Phytohormones function in regulating and coordinating plant growth and development. Phytohormones are also found to provide adaptive responses during stress conditions (Kumar et al. 2016). Interestingly, BBX genes also respond to phytohormones (Table 2) and role of BBX proteins integrating phytohormone and stress responses need further verifications. The transcript levels of OsBBX2, 7, 8, 14, 17, 19, and 24 genes get upregulated in response to gibberellin (GA), salicylic acid (SA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) hormones (Table 2) (Shalmani et al. 2019). Additionally, OsBBX8 and OsBBX14 are upregulated in response to ABA too (Table 2) (Shalmani et al. 2019). Expressions of OsBBX1 and OsBBX16 are elevated in response to GA and MeJA hormones, respectively (Table 2) (Shalmani et al. 2019). Microarray data of the transcript level of 11 OsBBX genes showed that they are regulated by hormones when the plants are treated with auxin, GA, and cytokinin (Table 2) (Huang et al. 2012). Most OsBBX members also contain hormone-responsive cis elements in their putative promoters (Huang et al. 2012). The promoters of AtBBXs also contain cis-regulatory elements that respond to hormones, including ethylene, auxin (IAA), ABA, GA and MeJA (Lyu et al. 2020). These observations suggest that most rice BBXs are involved in metal stresses and hormonal applications and further studies are required to elucidate their exact role in mediating these stress responses.

Crosstalk between BBX proteins and ABA in abiotic stress signaling

ABA is an important phytohormone regulating plant growth and development, and controls downstream gene expression in response to abiotic and biotic stresses. BBX proteins also function as key regulators controlling growth and development, and biotic and abiotic stress tolerance. BBX transcription factors play a crucial role in different signaling pathways, including light and hormones (Kushwaha et al. 2018). It has been reported that some BBX proteins participating in stress signaling, also respond to ABA (Shalmani et al. 2019; Min et al. 2015; Riboni et al. 2016).

In Arabidopsis, ABA-dependent transcriptional up-regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T under drought triggers the drought escape response. ABA stimulates photoperiodic response gene GIGANTEA (GI) and AtBBX1 signaling to promote FLOWERING LOCUS T activation, which mediates the drought escape response, floral induction, during drought stress, but the mode of regulation is still unknown. Additionally, ABA-INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3) interacts with CCT domain of AtBBX1 but importance of this interaction remains unknown (Kurup et al. 2000). In addition, AtBBX5 in Arabidopsis respond to salinity stress through the ABA‐dependent signaling pathway (Min et al. 2015). Under ABA or salinity treatment, AtBBX5-overexpressed and wild-type plants showed increased expression of other ABA biosynthesis and stress‐related genes including ABA1, NCED3, ABA3, RD29A, RD29B, and RAB18 (Min et al. 2015). Furthermore, AtBBX21 transcriptionally represses ABA-INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5), by controlling the binding of HY5 and ABI5 to the ABI5 promoter (Xu et al. 2014). However, involvement of AtBBX21 in abiotic stress signaling remains obscure.

In rice, OsBBX8 negatively regulates drought resistance and expression is upregulated by salt, cold, heavy metals and phytohormones, including ABA (Liu et al. 2016; Shalmani et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2012). In addition, OsBBX4 get upregulated by salinity, drought and ABA (Yan et al. 2012). High-throughput transcriptomic and expression data in Arabidopsis and rice suggested that exogenous application of ABA and abiotic stress, change the expression of numerous BBX genes (Tables 1 and 2). Most of the AtBBX and OsBBX members contain ABA-responsive and abiotic stress cis elements on their putative promoter regions (Huang et al. 2012; Lyu et al. 2020) demonstrating that BBX genes integrate abiotic stress and hormone signals. The functional aspects of BBX proteins in integrating abiotic stress and hormone signaling are little known.

BBX proteins in the improving abiotic stress responses

When crops are faced with simultaneous exposure to multiple abiotic stresses, it causes loss of productivity as well as affect their survival. B-box proteins are ideal targets to genetically engineer abiotic stress tolerance in plants, because they play a key role in coordinating physiological and biochemical pathways in response to abiotic stress. BBX proteins function in abiotic stress responses, including drought, salinity, heat and cold, UV-B and heavy metals. In Arabidopsis AtBBX1, 2, 5, 7, 11, 18, 24, 29 (Table 1) and in rice OsBBX1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19, 24 (Table 2) have been found to respond to more than one abiotic stress. BBX genes: AtBBX5, AtBBX18, AtBBX23 AtBBX24, AtBBX29, AtBBX31, OsBBX4 and OsBBX8 have been characterized by overexpression or mutant studies for abiotic stress responses (Fig. 4). Among functionally characterized BBX genes, AtBBX24 and OsBBX4 are involved in multistress responses. As most BBX proteins in rice and Arabidopsis show alteration in gene expression in response to multiple stress signaling, genetically engineering a crop with one such BBX gene can develop multistress-tolerant plants.

Fig. 4.

Action of functionally characterized Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins and their interacting partners in regulation of abiotic stress responses. The solid lines with arrow head indicate positive regulation. Solid lines with flat head indicate negative regulation. The numbers in parentheses indicate references. Abbreviations: ELF3 Early flowering 3, OsARID3 AT-rich Interaction Domain-containing protein, OsPURα The purine‐rich DNA‐binding protein, GF14b 14-3-3-like protein B, GF14c 14-3-3-like protein C, GF14e 14-3-3-like protein E, HPPBF1 H-protein promoter binding factor1, RCD1 RADICAL-INDUCED CELLDEATH1, COP1 CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1, HY5 ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5

In addition to Arabidopsis and rice BBX genes, studies on other crops BBX genes have revealed the possibility of manipulating BBX genes to confer tolerance to several abiotic stresses. Over-expression of BBX genes enhanced abiotic stress tolerance in chrysanthemums, apples and grapes (Table 3). Among them, chrysanthemums and apples respond to multistress conditions. Moreover, the conservation of BBX gene architecture and function during evolution, enable to manipulate genes in other crop species to develop tolerance against abiotic stress. For example, overexpression of Chrysanthemum, grape and apple BBXs in Arabidopsis, enhanced tolerance to abiotic stresses (Table 3). Furthermore, overexpression of the Arabidopsis AtBBX29 gene in sugarcane enhanced drought tolerance and delayed senescence (Mbambalala et al. 2020). As BBX proteins regulate the same physiological process in an opposite way in light (Gangappa and Botto 2014), BBX proteins also have opposite roles in regulating drought and UV-B stresses. For example, OsBBX8 negatively regulate drought stress whereas AtBBX29 and OsBBX4 positively regulate drought stress (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

BBX genes overexpressed in plants for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance

| Plant species | BBX name | Accession number | Overexpressed plant | Abiotic stress response | Mode of regulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrysanthemum morifolium | Cm-BBX24 | KF385866 | Chrysanthemummorifolium | freezing and drought tolerance | Positive | Yang et al. (2014) |

| CmBBX19 | KP963930 | Chrysanthemummorifolium | drought tolerance | Negative | Wang et al. (2018) | |

| CmBBX22 | No data | Arabidopsis thaliana | drought tolerance | Positive | Zeng et al. (2020) | |

| Vitis vinifera (Grape) | VvZFPF | HQ179976 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Cold tolerance | Positive | Zhang et al. (2019) |

| Malus domestica (Apple) | MdBBX10 | MDP0000733075 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Salt and drought tolerance | Positive | Jackson and Linsley (2004) |

| MdBBX37 | MDP0000157816 | Malus domestica | Cold tolerance | Positive | Jackson et al. (2003) |

However, many BBX proteins in rice, Arabidopsis and other crops are yet to be explored on multiple abiotic stresses. By identifying those genes in multistress tolerance will open up opportunities in future to apply them in genetic engineering to enhance crop improvement.

Nowadays, finding the most appropriate genetic engineering tool is challenging, because it affects the success of crop improvement and social acceptance of developed crops. RNA interference (RNAi)-based gene silencing mechanism and overexpression of genes have been widely used to engineer resistance in crops against abiotic stress. Such genetically engineered crops are considered as Genetically modified (GM) crops. However, the newly emerging genome editing tool, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system is a very effective tool in regulation of gene expression. CRISPR–Cas9 specifically makes double-stranded breaks (DSBs) on target genes. CRISPR–Cas9 is easy to use, more specific and it allows multiplex genome editing (Wang et al. 2018). Recently, researchers have used CRISPR/Cas9 to improve rice for cold tolerance, salinity tolerance by silencing OsMYB30 (Zeng et al. 2020), OsRR22 (Zhang et al. 2019) genes, respectively.

Although development of genetically modified (GM) crops is a promising solution in agriculture for the development of abiotic stress tolerant crops, the full acceptance of GM crops in many countries is still a matter of debate. Furthermore, in overexpressed plants, integration of the transgene is random and in the case of RNAi-based gene silencing, unwanted silencing of other genes can also occur (Jackson and Linsley 2004; Jackson et al. 2003). Therefore, having a great specificity to accurate modification a gene of interest, CRISPR genome editing tool will become a popular tool in crop improvement over conventional genetic engineering methods. Furthermore, technologies have been developed to eliminate transgenes efficiently after achieving the gene-editing process in plants (He et al. 2018b; Yubing et al. 2019). By generating transgene free improved crops, CRISPR genome editing tool will have the potential for crop improvement and social acceptance of developed crops over GM-based overexpression and gene silencing approaches. Hence, using one of the most appropriate techniques, multistress-tolerant transgenic crops will be developed using a single BBX gene or BBX genes in economically important plants to enhance crop productivity as a solution for the co-occurrence of different abiotic stresses in the field in future.

Concluding remarks

The BBX proteins are a subgroup of zinc finger transcription factors that contain conserved B-box domains. Genes that encode BBX proteins are highly conserved across all multicellular species from algae to dicotyledons. Arabidopsis contains 32 BBX proteins. Most of them have been extensively studied and showed that they play a key role in light-mediated plant growth and development and hormone regulation. Subsequently, BBX proteins have been identified from different crop plants; 30 from rice, 29 from tomato, 24 from grape, 30 from potato and 24 from sorghum and their functions are yet to be unraveled. Several studies have shown Arabidopsis and rice BBX proteins act as regulatory proteins in controlling abiotic stresses, including Ultraviolet-B (UV-B), salinity, drought, heat and heavy metal stresses. Large-scale transcriptomic data, bioinformatic studies and qRT-PCR data analysis studies demonstrated that many of those BBX proteins identified in Arabidopsis and rice have responded to more than one abiotic stress. Arabidopsis AtBBX1, 2, 5, 7, 11, 18, 24, 29 and in rice OsBBX1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19, 24 have been identified as BBX genes which can respond to more than one abiotic stress. Abiotic stress responses of BBX genes: AtBBX5, AtBBX18, AtBBX23 AtBBX24, AtBBX29, AtBBX31, OsBBX4 and OsBBX8 have been characterized by overexpression or mutant studies. Among them functionally characterized BBX genes, AtBBX24 and OsBBX4 are involved in multistress responses could be potential candidates to engineer multistress tolerance crops for improving the productivity of rice in the future.

Future prospects

There is a considerable progress in functional characterization of B-box proteins in abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis and rice. However, many BBX proteins in rice, Arabidopsis and other crops are yet to be studied on multiple abiotic stresses responses. Studies leading to further understanding of the functions, molecular mechanisms and interacting partners of each BBX protein, will no doubt provide clear insight of structural and functional relationship of BBX family. Complete understanding of abiotic stress signal transduction pathways of BBX genes, will produce opportunities to use them in genetic engineering to develop multistress-tolerant crop varieties to enhance crop yield in coming years. With the growing demand for food, new approaches to produce bio-engineered crops are needed to improve crop yield under abiotic stresses, and CRISPR–Cas9 technology will be the most promising in future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka [AP/3/2/2018/CG/29] which is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

CH, conceived the manuscript. CH and WWB wrote the manuscript. CH and WSSW helped in the revision of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Contributor Information

Wathsala W. Bandara, Email: wathsub@chem.cmb.ac.lk

W. S. S. Wijesundera, Email: sulochana@bmb.cmb.ac.lk

Chamari Hettiarachchi, Email: chamarih@chem.cmb.ac.lk, https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=T6skTrQAAAAJ&hl=en.

References

- Banerjee A, Roychoudhury A. Plant hormones under challenging environmental factor. Springer Nature; 2016. Plant responses to light stress: oxidative damages, photoprotection, and role of phytohormones; pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Belles-boix E, Babiychuk E, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Kushnir S. CEO1, a new protein from Arabidopsis thaliana, protects yeast against oxidative damage. FEBS Lett. 2000;482:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Han Y, Meng D, Li D, Jiao C, Jin Q, Lin Y, Cai Y. B-BOX genes : genome-wide identification, evolution and their contribution to pollen growth in pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1105-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Meng D, Han Y, Chen T, Jiao C, Chen Y, Jin Q. Comparative analysis of B-BOX genes and their expression pattern analysis under various treatments in dendrobium officinale. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1851-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CJ, Li Y, Chen L, Chen W, Hsieh W, Shin J, Chou S, Choi G, Hu J, Somerville S, Wu S. LZF1, a HY5-regulated transcriptional factor, functions in Arabidopsis de-etiolation. Plant J. 2008;54:205–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Liao YC, Yang CC, Wang AY. The purine-rich DNA-binding protein OsPurα participates in the regulation of the rice sucrose synthase 1 gene expression. Physiol Plant. 2011;143:219–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Li Q, Sun L, He Z. The rice 14-3-3 gene family and its involvement in responses to biotic and abiotic stress. DNA Res. 2006;13:53–63. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Burke JJ, Xin Z, Xu C, Velten J. Characterization of the Arabidopsis thermosensitive mutant atts02 reveals an important role for galactolipids in thermotolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:1437–1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XF, Wang ZY. Overexpression of COL9, a CONSTANS-LIKE gene, delays flowering by reducing expression of CO and FT in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;43:758–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Wang X, Li Y, Yu H, Li J, Lu Y, Li H. Genomic organization, phylogenetic and expression analysis of the B-BOX gene family in tomato. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsaftis O, Plett D, Johnson AAT, Walia H, Wilson C. Root-specific transcript profiling of contrasting rice genotypes in response to salinity stress. Mol Plant. 2011;4:25–41. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocco CD, Botto JF. BBX proteins in green plants : insights into their evolution, structure, feature and functional diversification. Gene. 2013;531:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi GHCM, Deng XW, Holm M. Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell. 2006;18:70–84. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Johansson H, Holm M. SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG2, a B-box protein in Arabidopsis that activates transcription and positively regulates light-mediated development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3242–3255. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Johansson H, Hettiarachchi C, Irigoyen ML, Desai M, Rubio V, Holm M. LZF1/SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG3, an Arabidopsis B-box protein involved in light-dependent development and gene expression, undergoes COP1-mediated ubiquitination. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2324–2338. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Reyes BG, Morsy M, Gibbons J, Varma TSN, Antoine W, McGrath JM, Halgren R, Redus M. A snapshot of the low temperature stress transcriptome of developing rice seedlings (Oryza sativa L.) via ESTs from subtracted cDNA library. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;107:1071–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Wang S, Song Z, Lu S, Li L, Liu J, Ding L, Wang S, Song Z, Jiang Y, Han J, Lu S, Li L, Liu J. Two B-box domain proteins, BBX18 and BBX23, interact with ELF3 and regulate thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1718–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldbri M, Sprenger M, Hahlbrock K. PcMYB1, a novel plant protein containing a DNA-binding domain with one MYB repeat, interacts in vivo with a light-regulatory promoter unit. Plant J. 1997;11:1079–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11051079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallia GL, Johnson EM, Khalili K. Purα: a multifunctional single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3197–3205. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Botto JF. The BBX family of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Holm M, Botto JF. Molecular interactions of BBX24 and BBX25 with HYH, HY5 HOMOLOG, to modulate Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8:24–28. doi: 10.4161/psb.25208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Crocco CD, Johansson H, Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Holm M, Botto JF. The Arabidopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1243–1257. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.109751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnesutta N, Kumimoto RW, Swain S, Chiara M, Siriwardana C, Horner DS, Holt BF, Mantovani R. CONSTANS imparts DNA sequence specificity to the histone fold NF-YB/NF-YC Dimer. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1516–1532. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S, Dunford RP, Coupland G, Laurie DA. The evolution of CONSTANS -like gene families in barley, rice, and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1855–1867. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016188.localization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Liu JH, Ma X, Luo DX, Gong ZH, Lu MH. The plant heat stress transcription factors (HSFS): structure, regulation, and function in response to abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah MA, Heyer AG, Hincha DK. A global survey of gene regulation during cold acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassidim M, Harir Y, Yakir E, Kron I, Green RM. Over-expression of CONSTANS-LIKE 5 can induce flowering in short-day grown Arabidopsis. Planta. 2009;230:481–491. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, He CQ, Ding NZ. Abiotic stresses: general defenses of land plants and chances for engineering multistress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zhu M, Wang L, Wu J, Wang Q, Wang R, Zhao Y. Programmed self-elimination of the CRISPR/Cas9 construct greatly accelerates the isolation of edited and transgene-free rice plants. Mol Plant. 2018;11:1210–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T, Tran T, Nguyen T, Williams B, Wurm P, Bellairs S, Mundree S. Improvement of salinity stress tolerance in rice: challenges and opportunities. Agronomy. 2016;6:54. doi: 10.3390/agronomy6040054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M, Hardtke CS, Gaudet R, Deng X. Identification of a structural motif that confers specific interaction with the WD40 repeat domain of Arabidopsis COP1. EMBO J. 2001;20:118–127. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zhao X, Weng X, Wang L, Xie W. The rice B-box zinc finger gene family: genomic identification, characterization, expression profiling and diurnal analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Noise amidst the silence: off-target effects of siRNAs? Trends Genet. 2004;20:521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Bartz SR, Schelter J, Kobayashi SV, Burchard J, Mao M, Li B, Cavet G, Linsley PS. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Nijhawan A, Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Sharma P, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. F-Box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1467–1483. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers P, Blomster T, Brosché M, Salojärvi J, Ahlfors R, Vainonen JP, Reddy RA, Immink R, Angenent G, Turck F, Overmyer K, Kangasjärvi J. Unequally redundant RCD1 and SRO1 mediate stress and developmental responses and interact with transcription factors. Plant J. 2009;60:268–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Wang Y, Björn LO, Li S. Arabidopsis RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH1 is involved in UV-B signaling. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2009;8:838–846. doi: 10.1039/b901187k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Wang Y, Li QF, Björn LO, He JX, Li SS. Arabidopsis STO/BBX24 negatively regulates UV-B signaling by interacting with COP1 and repressing HY5 transcriptional activity. Cell Res. 2012;22:1046–1057. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job N, Yadukrishnan P, Bursch K, Datta S, Johansson H. Two B-box proteins regulate photomorphogenesis by oppositely modulating HY5 through their diverse C-terminal domains. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:2963–2976. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar-agarwal S, Zhu J, Kim K, Agarwal M, Fu X, Huang A, Zhu J. The plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 interacts with RCD1 and functions in oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18816–18821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604711103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Kronmiller B, Maszle DR, Coupland G, Holm M, Mizuno T, Wu S-H. The Arabidopsis B-box zinc finger family. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3416–3420. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Park H, Jang YH, Lee JH, Kim J. The sequence variation responsible for the functional difference between the CONSTANS protein, and the CONSTANS-like (COL) 1 and COL2 proteins, resides mostly in the region encoded by their first exons. Plant Sci. 2013;199–200:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Park S, Lee JY, Ha SH, Lee JG, Lim SH. A rice B-Box protein, osBBX14, finely regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai T, Ito S, Nakamichi N, Niwa Y, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. The common function of a novel subfamily of B-box zinc finger proteins with reference to circadian-associated events in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:1539–1549. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sah SK, Khare T, Shriram V, Wani SH. Plant hormones under challenging environmental factors. Springer; 2016. Engineering phytohormones for abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants; pp. 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kurup S, Jones HD, Holdsworth MJ. Interactions of the developmental regulator ABI3 with proteins identified from developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant J. 2000;21:143–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2000.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha AK, Ramachandran H, Job N. The B-box bridge between light and hormones in plants. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2018;191:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledger S, Strayer C, Ashton F, Kay SA, Putterill J. Analysis of the function of two circadian-regulated CONSTANS-LIKE genes. Plant J. 2001;26:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M, Wan J, Czechowski T, Udvardi M, Stacey G. Identification of 118 Arabidopsis transcription factor and 30 ubiquitin-ligase genes responding to chitin, a plant-defense elicitor. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:900–911. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippuner V, Cyert MS, Gasser CS. Two classes of plant cDNA clones differentially complement yeast calcineurin mutants and increase salt tolerance of wild-type yeast. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12859–12866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Shen J, Xu Y, Li X, Xiao J, Xiong L. Ghd2, a CONSTANS -like gene, confers drought sensitivity through regulation of senescence in rice. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:5785–5798. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li R, Dai Y, Chen X, Wang X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the B-box gene family in the apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) genome. Mol Genet Genomics. 2018;293:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s00438-017-1386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dang P, Liu L, He C. Cold acclimation by the CBF—COR pathway in a changing climate: lessons from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:511–519. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu G, Li D, Li S. Bioinformatics analysis of BBX family genes and its response to UV-B in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15592324.2020.1782647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massiah MA. Ubiquitin proteasome system. IntechOpen; 2019. Zinc-binding B-box domains with RING folds serve critical roles in the protein ubiquitination pathways in plants and animals; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Massiah MA, Simmons BN, Short KM, Cox TC. Solution structure of the RBCC/TRIM B-box1 domain of human MID1: B-box with a RING. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:532–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massiah MA, Matts JA, Short KM, Simmons BN, Singireddy S, Yi Z, Cox TC. Solution structure of the MID1 B-box2 CHC (D/C) C 2 H 2 zinc-binding domain: insights into an evolutionarily conserved RING fold. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbambalala N, Panda SK, Van Der Vyver C. Overexpression of AtBBX29 improves drought tolerance by maintaining photosynthesis and enhancing the antioxidant and osmolyte capacity of sugarcane plants. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2020;39:419–433. doi: 10.1007/s11105-020-01261-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meroni G, Diez-roux G. TRIM/RBCC, a novel class of ‘ single protein RING finger ’ E3 ubiquitin ligases. BioEssays. 2005;27:1147–1157. doi: 10.1002/bies.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]